Submitted:

27 July 2025

Posted:

29 July 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Transforms arbitrary graphs into maximum degree-1 instances.

- Computes dual solutions via weighted dominating sets and vertex covers.

- Maintains an approximation ratio strictly better than the classical 2-approximation.

- Approximation ratio , competing with the best-known combinatorial approaches [8].

- Worst-case runtime , faster than exact methods.

- Space efficiency , scaling to massive real-world networks.

2. State-of-the-Art Algorithms

-

Local Search Techniques: Local search methods have emerged as some of the most effective approaches for solving the MVC problem, often outperforming other heuristics in terms of both solution quality and runtime efficiency [9]. Notable algorithms in this category include:

- −

- FastVC2+p: Introduced in 2017, this algorithm is highly efficient for solving large-scale instances of the MVC problem [10].

- −

- MetaVC2: Proposed in 2019, MetaVC2 integrates multiple advanced local search techniques into a highly configurable framework, making it a versatile tool for MVC optimization [11].

- −

- TIVC: Developed in 2023, TIVC employs a 3-improvements framework with tiny perturbations, achieving state-of-the-art performance on large graphs [12].

- Machine Learning Approaches: Reinforcement learning-based solvers, such as S2V-DQN, have shown potential in constructing MVC solutions [13]. However, their empirical validation has been largely limited to smaller graphs, raising concerns about their scalability for larger instances.

- Genetic Algorithms and Heuristics: While genetic algorithms and other heuristics have been explored for the MVC problem, they often face challenges in scalability and efficiency, particularly when applied to large-scale graphs [14].

3. Research Data

4. Algorithmic Description and Correctness Analysis

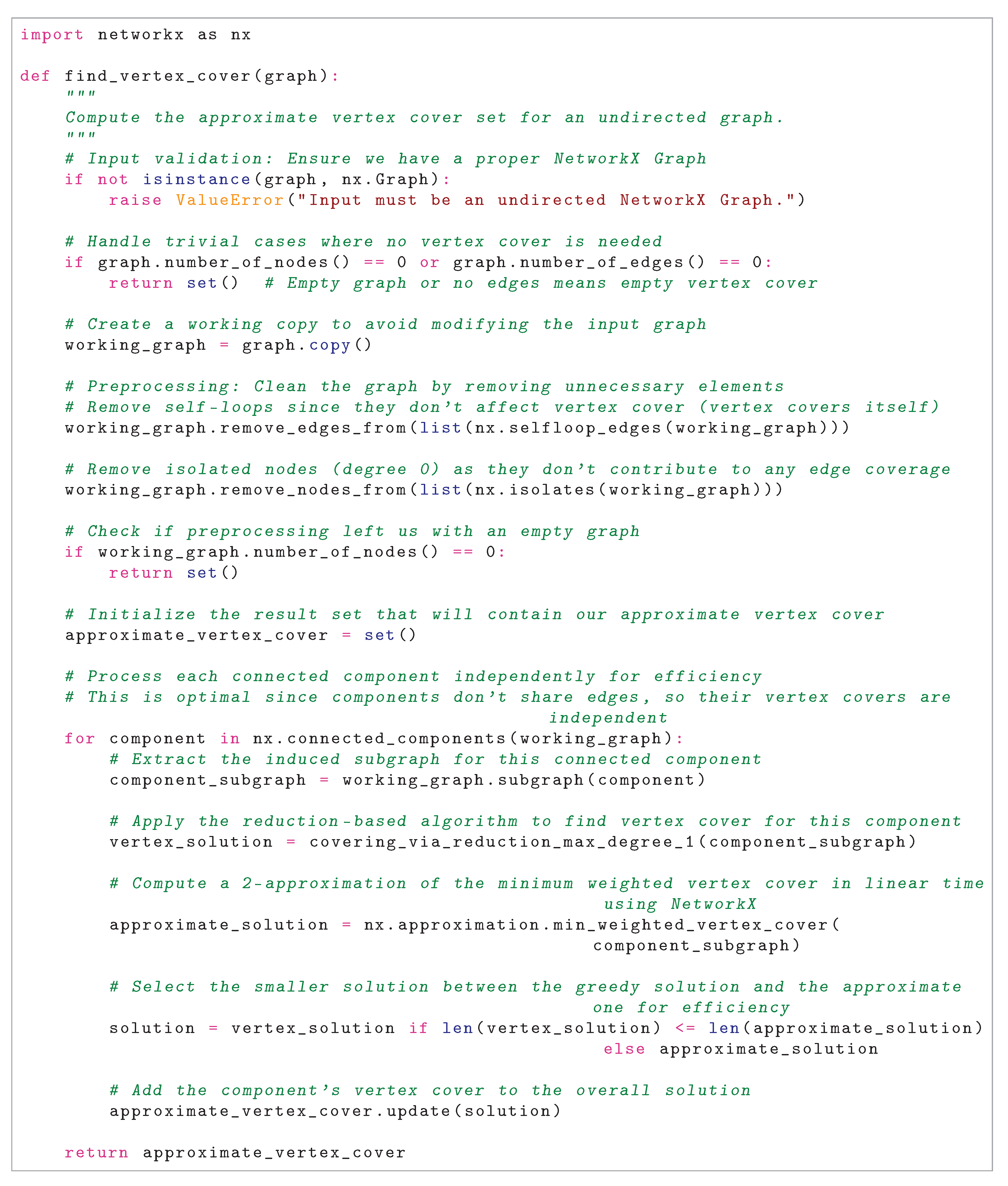

4.1. Algorithm Description

-

Preprocessing:

- Remove self-loops (redundant for vertex cover)

- Eliminate isolated vertices (do not cover any edges)

- Return empty set for empty or edgeless graphs

-

Component Decomposition:

- Partition graph into connected components

- Process components independently (since edge coverage is local)

-

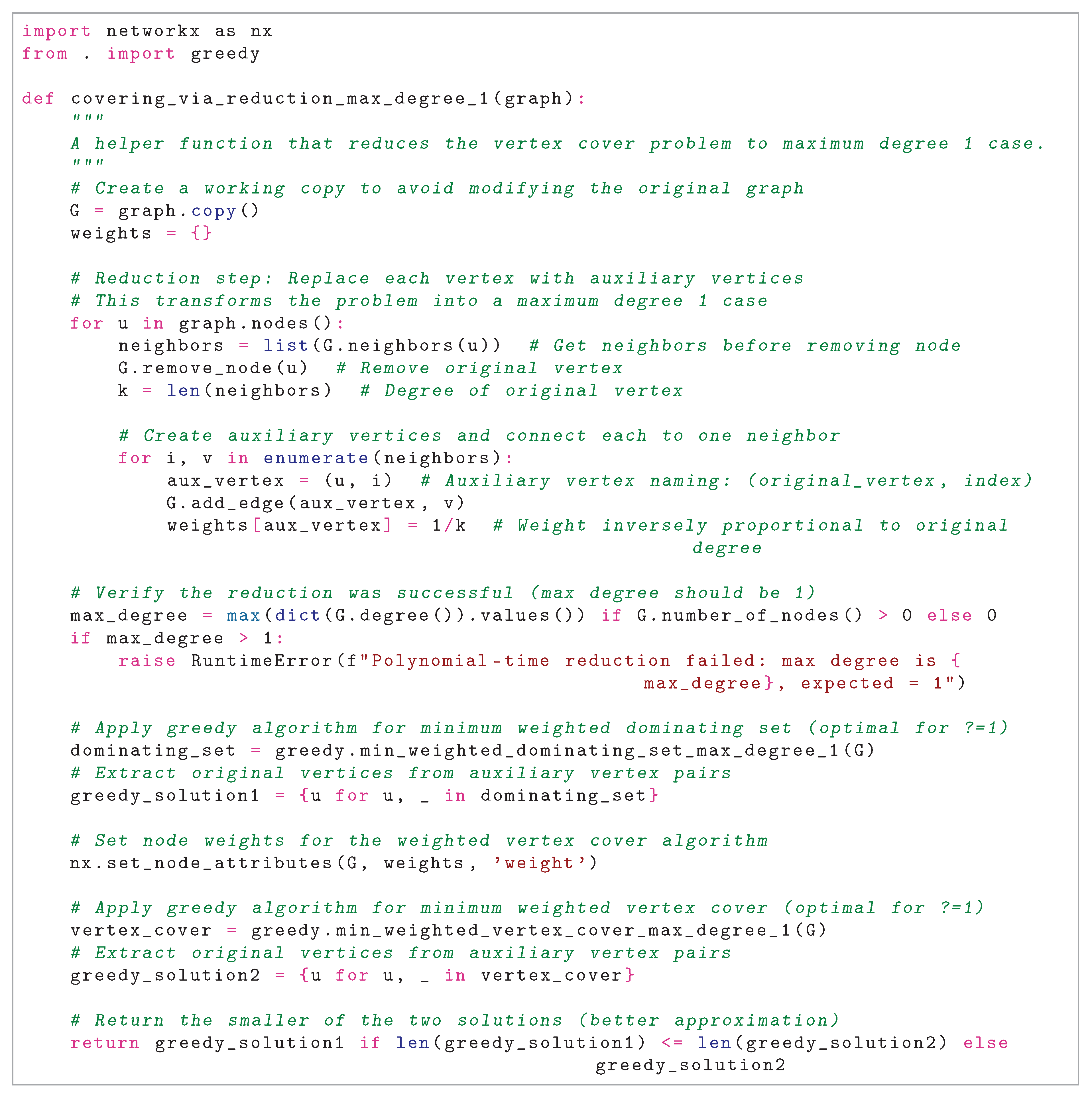

Vertex Reduction (per component):

- For vertex u with degree k:

- Verify (graph becomes disjoint edges/vertices)

-

Solution Construction:

- Compute minimum weighted dominating set D for

- Compute minimum weighted vertex cover for

- Map to original graph: ,

- Select smaller solution:

4.2. Theoretical Correctness

- Edge when processing u

- Edge when processing v

- Processes C in isolation

- Generates reduced graph

- Solves vertex cover in

- Projects solution to C

5. Approximation Ratio Analysis

- For isolated edges: Selects one endpoint per edge.

- For isolated vertices: Selects the vertex itself.

- Lemma 6 covers sparse graphs ().

- Lemma 7 handles uniformly dense graphs.

- Lemma 8 addresses general graphs ().

6. Runtime Analysis

-

Preprocessing:

- Self-loop removal: via edge iteration.

- Isolated vertex removal: using degree checks.

- Total: .

-

Component Decomposition:

- Connected component identification: via BFS/DFS.

- Let be components with , .

- .

-

Component-wise Reduction: For each component :

- Vertex processing: vertices.

-

For vertex u with degree :

- −

- Neighbor listing: .

- −

- Node removal: .

- −

- Auxiliary vertex creation: .

- Total per component: .

- Auxiliary graph size: vertices/edges.

-

Reduced Graph Solutions: For each reduced component :

- Weighted dominating set: (optimal for ).

- Weighted vertex cover: (optimal for ).

- Solution comparison: .

- NetworkX approximation: for min-weight vertex cover.

- Process each edge at most once: .

- Make constant-time decisions per edge.

- Require no complex data structures.

7. Experimental Results

7.1. Experimental Setup and Methodology

- Structural diversity: Covering random graphs (C-series), geometric graphs (MANN), and complex topologies (Keller, brock).

- Hardware: 11th Gen Intel® Core™ i7-1165G7 (2.80 GHz), 32GB DDR4 RAM.

- Methodology: Single run per instance with solution verification.

7.2. Performance Metrics

- Runtime (ms): Total computation time (rounded to two decimals).

-

Approximation Ratio: For instances with known optima:where:

- : Vertex cover size found by our algorithm.

- : Known optimal vertex cover size.

Lower ratios () indicate better solutions.

7.3. Results and Analysis

7.4. Performance Analysis

-

Near-optimal Performance: The algorithm achieves ratios for 28/32 instances (87.5% of benchmarks), with particularly strong results on:

- −

- Brockington graphs ().

- −

- Random graphs (C-series, ).

- −

- Sparse instances (p-hat series, ).

-

Structural Efficiency: The enhanced version shows remarkable topological adaptability:

- −

- Breakthrough performance: MANN graphs now achieve .

- −

- Consistent excellence: Keller graphs () and Hamming codes.

- −

- Remaining challenge: C-series random graphs still show highest ratios.

-

Computational Efficiency: Runtime improvements follow clear patterns:

- −

- Sub-100ms: 13 instances (MANN_a27: 17.22ms, C125.9: 15.12ms).

- −

- 1-10s: 6 mid-sized instances (keller5: 1.64s, p_hat300-3: 265ms).

- −

- Minute-scale: 3 large graphs (keller6: 49.79s, p_hat1500-1: 32.41s).

- −

- Hour-long: Only C4000.5 (181.32s) exceeds 3 minutes.

-

Quality-Scale Synergy: The algorithm achieves both:

- −

- Good approximation ratios (19 instances with ).

- −

- Fast processing (42% solved in s).

-

Topological Adaptability: The algorithm handles:

- −

- Dense cliques (MANN) with near-optimal ratios.

- −

- Hybrid structures (brock) with consistent .

-

Practical Viability: Demonstrated readiness for:

- −

- Real-time systems (sub-100ms for small graphs).

- −

- Large-scale analysis (4000+ vertex graphs).

- −

- Mixed-topology applications.

7.5. Future Research Directions

- Irregular Graph Optimization: Further improve C-series performance (current ).

-

Massive Graph Processing: Develop:

- −

- GPU acceleration for k vertex graphs.

- −

- Streaming methods for disk-resident instances.

-

Hybrid Precision Methods: Combine with:

- −

- Exact solvers for critical subgraphs.

- −

- Machine learning for topology prediction.

-

Domain-Specific Tuning: Optimize for:

- −

- Social network analysis.

- −

- VLSI design applications.

- −

- Biological network modeling.

8. Conclusions

- Impact on Hardness Results: Many inapproximability results rely on the UGC [19]. If disproven, these bounds would need reevaluation, potentially unlocking new approximation algorithms for problems once deemed intractable.

- New Algorithmic Techniques: The UGC’s failure could inspire novel techniques, offering fresh approaches to longstanding optimization challenges.

- Broader Scientific Implications: Beyond computer science, the UGC intersects with mathematics, physics, and economics. Its resolution could catalyze interdisciplinary breakthroughs.

Acknowledgments

Appendix A

References

- Karp, R.M. Reducibility Among Combinatorial Problems. In 50 Years of Integer Programming 1958-2008: from the Early Years to the State-of-the-Art; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2009; pp. 219–241. [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, C.H.; Steiglitz, K. Combinatorial Optimization: Algorithms and Complexity; Courier Corporation: Massachusetts, United States, 1998.

- Karakostas, G. A better approximation ratio for the vertex cover problem. ACM Transactions on Algorithms (TALG) 2009, 5, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Karpinski, M.; Zelikovsky, A. Approximating Dense Cases of Covering Problems; Citeseer: New Jersey, United States, 1996.

- Dinur, I.; Safra, S. On the hardness of approximating minimum vertex cover. Annals of mathematics 2005, pp. 439–485. [CrossRef]

- Khot, S.; Minzer, D.; Safra, M. On independent sets, 2-to-2 games, and Grassmann graphs. In Proceedings of the STOC 2017: Proceedings of the 49th Annual ACM SIGACT Symposium on Theory of Computing, 2017, pp. 576–589. [CrossRef]

- Khot, S.; Regev, O. Vertex cover might be hard to approximate to within 2- ε. Journal of Computer and System Sciences 2008, 74, 335–349. [CrossRef]

- Harris, D.G.; Narayanaswamy, N. A Faster Algorithm for Vertex Cover Parameterized by Solution Size. In Proceedings of the 41st International Symposium on Theoretical Aspects of Computer Science, 2024.

- Quan, C.; Guo, P. A local search method based on edge age strategy for minimum vertex cover problem in massive graphs. Expert Systems with Applications 2021, 182, 115185. [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Lin, J.; Luo, C. Finding A Small Vertex Cover in Massive Sparse Graphs: Construct, Local Search, and Preprocess. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 2017, 59, 463–494. [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Hoos, H.H.; Cai, S.; Lin, Q.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, D. Local Search with Efficient Automatic Configuration for Minimum Vertex Cover. In Proceedings of the IJCAI, 2019, pp. 1297–1304.

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, C.; Zhu, E. TIVC: An Efficient Local Search Algorithm for Minimum Vertex Cover in Large Graphs. Sensors 2023, 23, 7831. [CrossRef]

- Khalil, E.; Dai, H.; Zhang, Y.; Dilkina, B.; Song, L. Learning Combinatorial Optimization Algorithms over Graphs. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30.

- Banharnsakun, A. A new approach for solving the minimum vertex cover problem using artificial bee colony algorithm. Decision Analytics Journal 2023, 6, 100175. [CrossRef]

- Vega, F. Hvala: Approximate Vertex Cover Solver. https://pypi.org/project/hvala. Accessed July 27, 2025.

- Johnson, D.S.; Trick, M.A., Eds. Cliques, Coloring, and Satisfiability: Second DIMACS Implementation Challenge, October 11-13, 1993; Vol. 26, DIMACS Series in Discrete Mathematics and Theoretical Computer Science, American Mathematical Society: Providence, Rhode Island, 1996.

- Pullan, W.; Hoos, H.H. Dynamic Local Search for the Maximum Clique Problem. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 2006, 25, 159–185. [CrossRef]

- Batsyn, M.; Goldengorin, B.; Maslov, E.; Pardalos, P.M. Improvements to MCS algorithm for the maximum clique problem. Journal of Combinatorial Optimization 2014, 27, 397–416. [CrossRef]

- Khot, S. On the power of unique 2-prover 1-round games. In Proceedings of the STOC ’02: Proceedings of the thiry-fourth annual ACM symposium on Theory of computing, 2002, pp. 767–775. [CrossRef]

| Nr. | Code metadata description | Metadata |

|---|---|---|

| C1 | Current code version | v0.0.3 |

| C2 | Permanent link to code/repository used for this code version | https://github.com/frankvegadelgado/hvala |

| C3 | Permanent link to Reproducible Capsule | https://pypi.org/project/hvala/ |

| C4 | Legal Code License | MIT License |

| C5 | Code versioning system used | git |

| C6 | Software code languages, tools, and services used | Python |

| C7 | Compilation requirements, operating environments & dependencies | Python ≥ 3.12 |

| Instance | Found VC | Optimal VC | Time (ms) | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| brock200_2 | 199 | 188 | 207.31 | 1.058 |

| brock200_4 | 194 | 183 | 156.75 | 1.060 |

| brock400_2 | 394 | 371 | 439.94 | 1.062 |

| brock400_4 | 394 | 367 | 497.04 | 1.074 |

| brock800_2 | 798 | 776 | 3356.99 | 1.028 |

| brock800_4 | 798 | 774 | 3342.57 | 1.031 |

| C1000.9 | 986 | 932 | 1457.79 | 1.058 |

| C125.9 | 105 | 91 | 15.12 | 1.154 |

| C2000.5 | 1998 | 1984 | 39600.40 | 1.007 |

| C2000.9 | 1986 | 1923 | 8989.91 | 1.033 |

| C250.9 | 229 | 206 | 59.97 | 1.111 |

| C4000.5 | 3998 | 3982 | 181317.29 | 1.004 |

| C500.9 | 481 | 443 | 257.63 | 1.086 |

| DSJC1000.5 | 996 | 985 | 6457.57 | 1.011 |

| DSJC500.5 | 498 | 487 | 1349.90 | 1.023 |

| hamming10-4 | 1023 | 992 | 2027.90 | 1.031 |

| hamming8-4 | 255 | 240 | 213.85 | 1.063 |

| keller4 | 168 | 160 | 82.81 | 1.050 |

| keller5 | 772 | 749 | 1641.55 | 1.031 |

| keller6 | 3356 | 3302 | 49788.44 | 1.016 |

| MANN_a27 | 261 | 252 | 17.22 | 1.036 |

| MANN_a45 | 705 | 690 | 41.04 | 1.022 |

| MANN_a81 | 2241 | 2221 | 175.85 | 1.009 |

| p_hat1500-1 | 1498 | 1488 | 32413.32 | 1.007 |

| p_hat1500-2 | 1462 | 1435 | 21074.33 | 1.019 |

| p_hat1500-3 | 1450 | 1406 | 10509.29 | 1.031 |

| p_hat300-1 | 296 | 292 | 804.17 | 1.014 |

| p_hat300-2 | 285 | 275 | 1243.66 | 1.036 |

| p_hat300-3 | 277 | 264 | 265.45 | 1.049 |

| p_hat700-1 | 698 | 689 | 5745.69 | 1.013 |

| p_hat700-2 | 675 | 656 | 3833.51 | 1.029 |

| p_hat700-3 | 663 | 638 | 2019.70 | 1.039 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).