1. Introduction

The introduction should briefly place the study in a broad context and highlight why it is Tooth enamel is the outermost layer of the tooth and is continuously exposed to various external factors that can compromise its surface integrity. These factors include biofilm, acids produced by bacteria, food and pigmenting substances [

1,

2]. Effective plaque removal is essential for maintaining optimal oral health and, for this purpose, toothbrushes and toothpastes are used. However, excessive or inappropriate use of these products can induce alterations in the enamel surface, such as roughness and abrasion [

3,

4].

Dental abrasion is a multifactorial phenomenon caused by friction on tooth surfaces and contact with abrasive substances, resulting in the loss of mineral material. This wear can lead to the exposure of the dentinal tubules, increasing tooth sensitivity and even causing tooth loss [

5,

6,

7]. On the other hand, surface roughness also plays an important role in the health of dental enamel, favoring the adhesion of microorganisms and promoting the accumulation of plaque, which can lead to problems such as gingival inflammation and the formation of caries [

8,

9]. Factors such as poor brushing technique, the amount and type of toothpaste, the frequency of brushing, the hardness of the toothbrush filaments and the pressure exerted during tooth cleaning, generate abrasion and roughness of the enamel, causing significant changes in its surface [

10].

In recent years, the use of activated charcoal in personal care products, especially in toothpastes, has gained popularity, which has led to a growing interest in its possible effects on tooth enamel abrasion and roughness [

11]. Recent studies have shown significant enamel loss in groups using toothpaste with activated charcoal, as well as alterations such as surface roughness [

12,

13,

14,

15]. This trend is partly due to the high percentage of toothpastes containing whitening agents, including activated charcoal. However, despite the widespread promotion of its whitening benefits, the scientific evidence supporting its effectiveness is limited, and many claims about its therapeutic effects are not substantiated [

16,

17].

The purpose of the research was to evaluate the abrasion and roughness of tooth enamel using toothpastes with and without activated charcoal in vitro and SEM analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Size

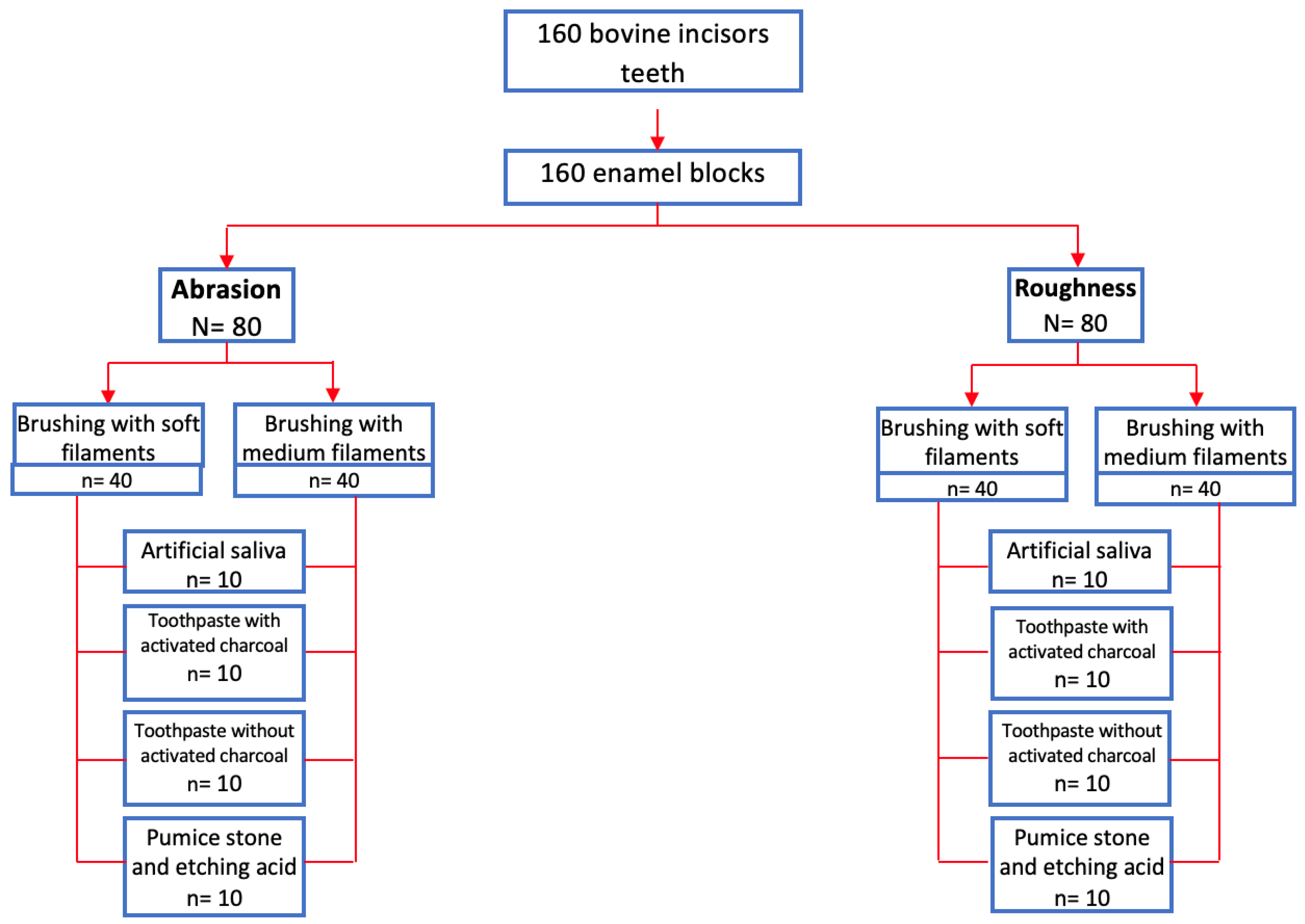

A total of 160 enamel blocks were assigned, of which 80 were destined to the abrasion analysis and 80 to the roughness study. Both were evaluated independently and simultaneously, as follows: (

Figure 1)

Negative control group: 20 enamel blocks immersed in artificial saliva; 10 for the group with soft filament brushes and 10 with medium filament brushes.

Group brushing with toothpaste with activated charcoal: 20 enamel blocks subjected to brushing cycles, distributed in 10 with soft filament brushes and 10 with medium filament brushes.

Group brushing with toothpaste without activated charcoal: 20 enamel blocks subjected to brushing cycles, distributed in 10 with soft filament brushes and 10 with medium filament brushes.

Positive control group (pumice stone and etching acid): 20 enamel blocks subjected to brushing cycles, distributed in 10 with soft filament brushes and 10 with medium filament brushes.

2.2. Data Compilation

The present research was of experimental design and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Professional School of Stomatology of the Universidad César Vallejo, Piura, Peru (Resolution N° 0089- 2023- /UCV/ P), dated December 16, 2023.

160 bovine incisors were donated by the animal slaughter area of Frigorífico Camal La Colonial, Lima, Peru [

18,

19]. Teeth with intact buccal surfaces were selected, excluding those with crown defects, carious lesions or fractures. The teeth were extracted using a straight punch and a Rottmann Stainless Steel Milano forceps. Subsequently, they were washed with running water and thoroughly cleaned with a scalpel No. 15 to eliminate organic tissue remains, were subsequently disinfected with isopropyl alcohol [

15]. The blocks were obtained from the vestibular surface of the teeth and cut with a medium-grit diamond disk (NTI Kerr D335-190). Each block had dimensions of 5 × 5 mm and a thickness of 2 mm, verified using a digital Vernier caliper (Mitutoyo, 200 mm, Japan; lot B23082834). The surfaces were polished for 30 seconds with N° 1200 sandpaper under constant irrigation with water to obtain a uniform surface. A total of 160 enamel blocks were obtained, of which 80 were selected for the roughness study and 80 for the abrasion analysis [

15,

20,

21]. (

Figure 1)

Materials

The materials used in the study were as follows:

- Toothpastes: With activated carbon: Oral B Natural Essence (Made in Mexico, lot 30904354P4). Without activated carbon: Colgate Total 12 Antisarro (Made in Mexico, lot 3348MX1131).

- Toothbrushes: Soft filaments: Colgate Procuidado (Made in Vietnam, lot 3333Z). Medium filaments: Colgate Colors (Made in Vietnam, lot 0374QZ).

- Artificial saliva: Manufactured by LUSA, Laboratorios Unidos S.A. (Peru, lot 2081683).

- Pumice stone. Fine grain size (<50um), Peru

-Phosphoric Acid 37% (Manufactured by Densell, Argentina; lot 2204789).

Procedure

For the abrasion experiment

, the enamel blocks were dried for 24 hours at 37 °C before and after the brushing cycles, using an induction furnace equipped with an infrared radiation thermometer (Mestek, IR02B, China, with a range of -50 °C to 800 °C). The blocks were weighed before (M1) and after (M2) (Mfinal = M1 - M2) to determine the difference in weight using an electronic scale (Exactrol PTX- FA210S, 0.0001g approximation, 2107214210 series, Switzerland). The brushing was performed with a cycling equipment (HTL CERTIFICATE model YX 3000- 280007G, 1 cycle approximation, Peru). This process simulated brushing for 20 days, 3 times a day for two minutes (120 minutes in total) [

8,

22]. The brushes were adapted to the cycling machine simulating the process of 6 sessions of 15 seconds each.

The brush handle was cut 5 cm to fit the machine tube and the enamel block was secured on a base that had a bolt applying low pressure. The cycling parameters were 5Hz frequency and 200g or 1.9N load, with rinsing and addition of bean-sized toothpaste to the middle of the brush every 15 minutes. After the cycling process was completed, it was dried in the induction oven at 37 °C for 24 hours and the second weight (M2) was recorded. This procedure was carried out simultaneously using a new brush for each brushing cycle on the enamel blocks and individually [

8,

22,

23,

24].

In the roughness experiment, the enamel blocks were mounted on acrylic discs with exposure exposing only the vestibular surface. A roughness meter (Huatec SRT- 6200, Switzerland, series N921838, 0.001 approximation μm) was used for measurement in microns (μm) before (μ1) and after (μ2) to determine the difference (μFINAL= μ1- μ2). The brushing was carried out with a cycling equipment (HTL CERTIFICATE model YX 3000- 280007G, approximation of 1 cycle, Peru) simulating a brushing corresponding to 20 days, with a frequency of 3 times a day, during two minutes (120 minutes in total) [

15,

20].

The initial roughness measurement (μ1) of the enamel blocks was recorded, then the brushing cycle was performed. The cycling parameters were 5Hz frequency and 200g or 1.9N load. Bean-sized toothpaste was added to the middle part of the brush every 15 minutes and washed with water for 30 seconds. At the end of the cycling process, the second roughness measurement was recorded [

15,

20]. The whole process was performed independently and in parallel using a new brush for each brushing cycle on the enamel blocks.

Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM)

The following samples were randomly selected and analyzed under SEM: one block of untreated enamel, one block of the negative control group, one block of the positive control group and four blocks subjected to brushing. Of the latter, two were exposed to paste with activated carbon (one with soft filament brush and one with medium filaments), and two to paste without activated carbon (one with soft filaments and one with medium filaments). The preparation of the blocks was carried out as follows: First, they were dried in the induction oven for 24 h at 37 °C, and then all the enamel blocks were fixed in carbon fiber on metal platforms known as Stubs, metallizing them with gold through a SPI- MODULE brand metallizer. The observation was performed in the scanning electron microscope (FEI INSPECT S50, USA, 200 nA current beam, -15 to 75° tilt, 360° rotation), under high vacuum conditions, with magnification of 1000 x and 5000 x and aperture parameters of 4.5 to 5, at a working distance of 10 mm and electric power of 5 to 6 kilovolts [

20,

25].

Statistical Analysis

The descriptive analysis and the explanation of the database obtained were performed using a Microsoft Excel 2019 spreadsheet and the SPSS version 26 statistical program. Measures of central tendency and dispersion were calculated, including mean, standard deviation, standard error, median, interquartile range, and minimum and maximum values. For inferential analysis, the normality of the data was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test and the homogeneity of variances with Bartlett's test. Student's t-test was applied to compare tooth enamel roughness and abrasion between the soft and medium filament brushing groups within each experimental treatment. A significance level of p < 0.05 was established.

3. Results

3.1. Abrasion and Roughness of Tooth Enamel

Table 1 shows the averages of the mean surface roughness among the groups that used soft and medium filament brushes; a significant difference was found when toothpaste with activated charcoal was used (p=0.0016). Likewise, the abrasion among the groups that used soft and medium filament brushes, significant differences were determined in the group that used toothpaste with activated charcoal (p=0.0001).

3.2. Enamel Roughness According to Toothbrush and Toothpaste Type

Table 2 shows the mean, standard deviation and median of the surface roughness evaluation. It is observed that the roughness when brushes with soft filaments were used showed its highest value of the mean in the group with pumice (0.403 ± 0.222), followed by the group with activated carbon (0.300 ± 0.138). In the groups that used brushes with medium filaments, the highest value of the roughness mean was observed in the group with activated carbon (0.525 ± 0.134) and the median of all the groups presented the highest value with brushes with medium filaments, corresponding to the group with activated carbon the highest value (0.502).

3.3. Enamel Abrasion According to Toothbrush and Toothpaste Type

Table 3 shows the mean, standard deviation and median of the abrasion evaluation. It is observed that when soft filament brushes were used, the highest value of the mean was observed in the group with artificial saliva (-0.00011 ± 0.00013), followed by the group with activated charcoal (-0.00082 ± 0.00025). In the group with medium filament brushes the highest value of the mean was observed in the group with artificial saliva (-3E-05 ± 0.00016) followed by the group with activated charcoal (-0.00155± 0.00034), the median value did not present variation for any experimental group, being the artificial saliva group with the highest value (-0.00010) followed by the group with activated charcoal (-0.00090).

3.4. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) Analysis of the Enamel Blocks

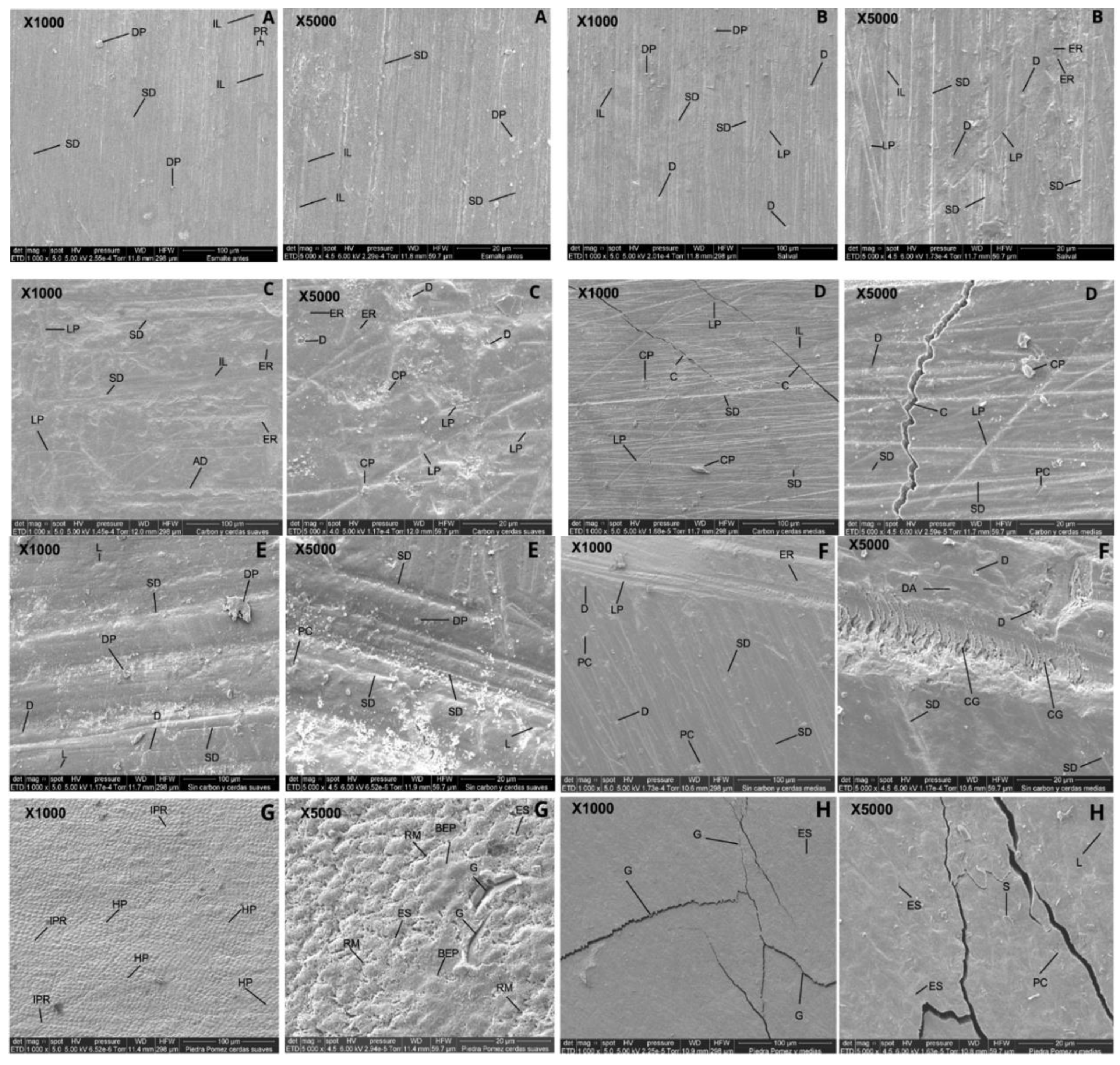

In

Figure 2A (1000x), the uniform prismatic enamel is observed without any intervention, with imbrication lines (IL), perichematite ridges (PR), vertical striations of different depths (SD) and surface deposit particles (DP). At 5000x, the prismatic enamel showed remarkable variation, with imbrication lines (IL), striations of different depths (SD) and superficial deposits (DP).

Figure 2B (1000x) shows enamel that was immersed in artificial saliva with evidence of prismatic enamel and imbrication lines (IL), vertical striations of different depths (SD), lines that do not follow a pattern (LP), pitted depressions (D) and surface deposits (DP). At 5000x, enamel rod ends (ER), defined imbrication lines (IL), prominent vertical striated surfaces (SD), pit-like depressions (D) and lines that do not follow an increasing pattern (LP) are observed.

In

Figure 2C (1000 x), tooth enamel is observed after the brushing cycle with activated charcoal toothpaste using a soft filament brush. Prismatic enamel is observed with poorly defined imbrication lines (IL), enamel rod ends (ER), striae of different depths (SD), lines that do not follow a pattern (LP), depressed areas (DA). At 5000x, lines without any pattern (LP), pit-like depressions (D), charcoal particles (CP), abundant enamel rod ends (ER).

Figure 2D (1000x) shows the dental enamel after the brushing cycle with toothpaste with activated charcoal and brushing using a medium filament brush. The prismatic enamel is observed with striations of different depths (SD), scarce imbrication lines (IL), deposits and fragments of charcoal of greater size (CP), lines that do not follow a pattern (LP) and cracks (C). At 5000x, pronounced striations of different depths (SD), pits and craters of different sizes (PC), pit-like depressions (D), activated charcoal particles (CP), lines of irregular depth (LP) and cracks (C).

In

Figure 2E (1000x), it is observed in the dental enamel after the brushing cycle with toothpaste without activated charcoal using a soft filament brush. Scattered one-way striations with different depths (SD), pit-like depressions (D), defined and regular linear depressions (L), superficial deposits (DP) are observed. At 5000x, there is widening of one-way and continuous striations (SD), pits and craters of different sizes (PC), defined linear depressions (L) and abundant superficial deposits (DP).

Figure 2F (1000x) shows the tooth enamel with a brushing cycle using toothpaste without activated carbon and a medium-bristled brush; the ends of enamel rods (ER), irregular striations of different depths (SD), depressions that form pits (D), pits and craters (PC), lines that do not follow the same pattern (LP) can be seen; at 5000x, slightly marked striations (SD), crescent-shaped perpendicular grooves (CG), pit-shaped depressions (D) and depressive areas (DA) can be seen.

In

Figure 2G (1000x), the dental enamel is observed after the brushing cycle with pumice and etching acid using a soft filament brush. The surface shows micro-retentions; the heads of the enamel prisms (HP) are evident and defined interprismatic region (IPR). At 5000x, marked micro-retentions (RM), the affected enamel prism sheath (ES), the body of the enamel prism (BEP) where the prism head has been removed, cracks and deep grooves (G) are evident.

In

Figure 2H (1000x), the enamel is observed after the brushing cycle with pumice and etching acid using medium filament brushes. The enamel prisms are almost completely removed, the prism sheath is poorly defined (ES), and shows some cracks and fractures (G). At 5000x, the prismatic surface of the enamel was observed with fish scale appearance (S), widening of the prism sheaths (ES), crater-like depressions (PC) and pits forming linear depressions (L).

4. Discussion

The characteristics of the tooth enamel surface play a fundamental role in its protective function, as they constitute the first line of defense against acids produced by bacteria, thus preserving the integrity of the dentin-pulp complex. It has been established that a surface roughness threshold of 0.2 μm favors the retention of microorganisms, which highlights the importance of maintaining a smooth surface to prevent bacterial adhesion and proliferation. Abrasion of the enamel can lead to a progressive and disproportionate loss of this tissue, which not only increases tooth sensitivity, but also increases the risk of caries and can compromise the structure of the pulp organ [

9,

10].

The results of the present study determined that there is a significant difference in enamel roughness (p = 0.0016) and abrasion (p = 0.0001) when using brushing cycles with activated charcoal toothpaste (

Table 1). These findings are confirmed by the research conducted by Zamudio et al. and Maciel et al. who also indicated a significant difference in enamel abrasion when using toothpaste with activated charcoal (p < 0.05) [

15,

26]. The mechanical process caused by the constant friction of an object on the tooth surface is intensified with the use of larger particles, and this wear is further aggravated by vigorous brushing and the hardness of the brush filaments [

27].

The roughness of the tooth enamel blocks that were brushed with medium filaments and toothpaste with activated charcoal presented a significantly higher mean value (0.525 ± 0.134). The variation of roughness in different groups also showed a significant difference (p = 0.0001); these results coincide with the studies of Forouzanfar et al. and Andrade

et al, who determined that the difference in tooth enamel roughness was greater when using toothpaste with activated charcoal [

21,

28]. These results could be due to the fact that in their methodology a polishing process was used on the enamel blocks to obtain a smoother surface. The brushing cycles were performed with a cycling machine using linear and unidirectional movements.

It should be noted that activated carbon has a rough and porous appearance, which during brushing could influence the superficial changes of the dental enamel due to the fact that these are larger insoluble abrasive particles, which act by mechanical and physical processes to remove extrinsic stains. In addition, the actual contact area is proportional to the load and pressure exerted, determined by roughness points, contributing to the increase of this roughness [

3,

17,

29].

The present study evaluated dental abrasion through weight before and after the brushing cycles, demonstrating that the highest value of the mean weight difference was observed in the groups brushed with soft and medium filaments using toothpaste with activated charcoal. Similarly, a significant difference was observed when comparing brushing with medium filaments and toothpaste with activated charcoal (p = 0.01). Similar results were found by Greunling et al.

, who studied different types of toothpastes with activated charcoal and showed that one of these toothpastes presented a significantly higher difference in tooth enamel abrasion [

12]; although the study performed the procedure using electric toothbrushes, these were connected to a cycling machine that simulated the brushing process with a frequency of 0.5 Hz. Similarly, Moreno et al. evaluated the abrasion of tooth enamel by the use of two toothpastes with activated charcoal and showed that both toothpastes caused weight loss with values of 4.11% and 2.68% [

22]. These coincidences in the results could be attributed to the type of brush, with medium filaments. Viana I, et al. revealed that toothpastes with activated charcoal and the control group did not present a significant difference in surface loss and provided greater protection against abrasion [

30]. In contrast to this research, in their study they used optical profilometry and immersed the enamel blocks in citric acid solution for 5 minutes, followed by immersion in artificial saliva for one hour, repeating the process 4 times a day for 5 days. In the present study, a positive control group composed of an acid agent (etching acid) and an abrasive agent (pumice) was used, since both substances combined produce micro-abrasion. This is a technique used in the dental clinic to eliminate superficial alterations of the dental enamel, guaranteeing that there is a loss of up to 250 µm [

23].

Tooth enamel abrasion is significantly higher when brushing is performed with toothpaste containing activated charcoal, which adheres to extrinsic deposits such as pigmenting substances retained in the dental biofilm, through the pores of the charcoal, which are then eliminated by brushing, leaving the tooth surface free of these substances [

3,

17,

31]. However, it is important not to extrapolate the results of the study to all whitening toothpastes, since the effects depend on the amount and type of particles present in the formulations [

12].

The present investigation carried out the analysis of the samples through SEM; it should be noted that healthy dental enamel is formed by hydroxyapatite crystals and its structural unit is the enamel prism, the external part of these prisms creates an interprismatic region [

32]. Thus, the findings of the study (

Figure 2) are in agreement with the results of Emídio et al. who refer that through the analysis of the micrographs changes in the morphology of the dental enamel were observed in the groups treated with toothpaste with activated charcoal (

Figure 2C,D) [

14]. This is possibly due to the type of brush used and the brushing time, suggesting increased abrasion due to the stiffness of the brush filaments and the abrasive properties of the activated charcoal. Although dental enamel is one of the most mineralized tissues in the human body, it also presents a fragility associated with its low strength, leading to cracks and fractures of the enamel [

1,

19,

31]. These results differ from those observed in the study by Koc et al. who indicated that only a few scratches were observed on the enamel surface in all the groups studied [

33]. This is possibly due to the fact that all groups in the study used toothpastes with activated charcoal and other abrasive particles.

The morphology of the enamel in the microphotographs obtained in this study was observed with greater alteration when the brushing process was performed with medium filaments and paste with activated charcoal (

Figure 2D), with disorganized striations being visible, indicating increased surface roughness.

Despite the relevant findings obtained in this investigation, it is crucial to recognize the limitations inherent in the experimental design. Firstly, being an in vitro study, the results observed in terms of tooth enamel abrasion and roughness cannot be directly extrapolated to a clinical setting. The absence of biological factors such as saliva, the presence of biofilm and masticatory forces, which considerably influence the dynamics of tooth wear in the oral cavity, limits the applicability of the results to daily clinical practice. The selection of a single brushing frequency and specific load may not reflect variations in brushing technique and forces applied by different individuals in a real-world setting, suggesting the need for additional studies that explore a wider range of parameters. The choice of a methodology based on linear and unidirectional brushing cycles, although controlled and reproducible, does not fully capture the complexity of brushing movements in clinical practice, which include multidirectional patterns and variations in applied pressure. In addition, it is important to mention the limitation related to the lack of simulation of enamel remineralization, a dynamic process that constantly occurs in the oral cavity and that could mitigate the effects of brushing-induced abrasion. The inclusion of a remineralization protocol in future studies could provide a more complete understanding of how activated charcoal toothpastes interact with enamel under conditions that more closely emulate the oral environment

5. Conclusions

The in vitro study showed that the use of toothpaste with activated charcoal increases tooth enamel roughness and abrasion, particularly when combined with a medium filament toothbrush

Author Contributions

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, F.T.A.C. and R.J.P.R.; methodology, F.T.A.C., R.J.P.R., A.R.E.S. and P.M.H.-P.; software, F.T.A.C., R.J.P.R.; validation, F.T.A.C., R.J.P.R. and P.M.H.-P.; formal analysis, F.T.A.C., R.J.P.R. and P.M.H.-P.; investigation, F.T.A.C., R.J.P.R., A.R.E.S. and P.M.H.-P.; resources, F.T.A.C. and R.J.P.R.; data curation, F.T.A.C., R.J.P.R. and A.R.E.S.; writing—original draft preparation, F.T.A.C., R.J.P.R., A.R.E.S. and P.M.H.-P.; writing—review and editing, , F.T.A.C., R.J.P.R. and P.M.H.-P.; visualization, F.T.A.C. and R.J.P.R.; supervision, P.M.H.-P.; project administration, F.T.A.C. and R.J.P.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of the Research Ethics Committee of the Professional School of Stomatology of the Universidad César Vallejo, Piura, Peru (Resolution N° 0089- 2023- /UCV/ P), dated December 16, 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sarna K, Skic K, Boguta P, Adamczuk A, Vodanovic M, Chałas R. Elemental mapping of human teeth enamel, dentine and cementum in view of their microstructure. Micron. 2023, 172, 103485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aspinall S, Parker J, Khutoryanskiy V. Oral care product formulations, properties and challenges. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces. 2021, 200, 111567. [CrossRef]

- Palomino RC, Delgado L. Lo que debemos saber sobre dentífricos blanqueadores. Rev Estomatol Herediana. 2022, 32, 405–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rode S, Sato T, Matos F, Correia A, Camargo S. Toxicity and effect of whitening toothpastes on enamel surface. Braz oral res. 2021, 35, e025. [CrossRef]

- Sawai, M. An easy classification for dental cervical abrasions. Eur J Dent. 2014, 5, 142–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, A. Cervical abrasion injuries in current dentistry. J Dent Health Oral Disord Ther 2018, 9, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuza A, Racic M, Ivkovic N, Krunic J, Stojanovic N, Bozovic D. et al. Prevalence of non-carious cervical lesions among the general population of the Republic of Srpska, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Int Dent J. 2019, 69, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayyer M, Zahid S, Hassan SH, Mian SA, Mehmood S, Khan HA, et al. Comparative abrasive wear resistance and surface analysis of dental resin-based materials. Eur J Dent. 2018, 12, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollenl C, Lambrechts P, Quirynen M. Comparison of surface roughness of oral hard materials to the threshold surface roughness for bacterial plaque retention: A review of the literature. Dental Materials. 1997, 13, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez C, Dubón S, Madrid M, Sánchez I. Lesiones dentales no cariosas: etiología y diagnóstico clínico. Revisión de literatura. Rev Cient Esc Univ Cienc Salud. 2020, 7, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez N, Fayne R, Burroway B. Charcoal: An ancient material with a new face. Clinics in Dermatology. 2020, 38, 262–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greuling A, Emke J, Eisenburger M. Abrasion Behaviour of Different Charcoal Toothpastes When Using Electric Toothbrushes. Dent J (Basel). 2021, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertuan M, da Silva J, de Oliveira A, da Silva T, Justo A, Zordan F, et al. The in vitro Effect of Dentifrices With Activated Charcoal on Eroded Teeth. Int Dent J. 2022, 73, 518–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emídio A, Silva V, Ribeiro E, Zanin G, Lopes M, Guiraldo R, et al. In vitro assessment of activated charcoal-based dental products. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2023, 35, 423–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamudio J, Ladera M, Santander F, López C, Cornejo A, Echavarría A, et al. Effect of 16% Carbamide Peroxide and Activated-Charcoal-Based Whitening Toothpaste on Enamel Surface Roughness in Bovine Teeth: An In vitro Study. Biomedicines. 2022, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostamzadeh P, Omrani L, Abbasi M, Yekaninejad M, Ahmadi E. Effect of whitening toothpastes containing activated charcoal, abrasive particles, or hydrogen peroxide on the color of aged microhybrid composite. Dent Res J (Isfahan). 2021, 18, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwall L, Greenwall J, Wilson N. Charcoal-containing dentifrices. Br Dent J. 2019, 226, 697–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland J, Roberts R, Palmer G, Bauman D, Bazer F. A commentary on domestic animals as dual-purpose models that benefit agricultural and biomedical research1. Journal of Animal Science. 2008, 86, 2797–805. [CrossRef]

- Acevedo E, Peláez A, Christiani J. El esmalte dental bovino como modelo experimental para la investigación en odontología. Una revisión de la literatura. AOA. 2021, 109, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazar A, Hazar E. Effects of Whitening Dentifrices on the Enamel Color, Surface Roughness, and Morphology. Odovtos - International Journal of Dental Sciences. 2023, 25, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forouzanfar A, Hasanpour P, Yazdandoust Y, Bagheri H, Mohammadipour H. Evaluating the Effect of Active Charcoal-Containing Toothpaste on Color Change, Microhardness, and Surface Roughness of Tooth Enamel and Resin Composite Restorative Materials. Int J Dent. 2023, 2023, e6736623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno F, Mantilla M, Tolen S, Ledesma M, Mata X. Efecto abrasivo de pastas con carbón activado. Rev Invest Cien Sal. 2021, 16, 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez J, Arango L. Desgaste del esmalte por diferentes tratamientos químicos y mecánicos. Odontología. 2019, 21, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera C, Rojas R, Girano J, Vergara B, Castro Y. Efecto aclarante del ácido clorhídrico (18%) y el ácido fosfórico (37%) sobre el esmalte dental. Estudio experimental in vitro. Rev Odont Mex. 2020, 24, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriyasangpetch S, Sivavong P, Niyatiwatchanchai B, Osathanon T, Gorwong P, Pianmee C, et al. Effect of Whitening Toothpaste on Surface Roughness and Colour Alteration of Artificially Extrinsic Stained Human Enamel: In vitro Study. Dentistry Journal. 2022, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel J, Geng R, Pires F. Remineralization, color stability and surface roughness of tooth enamel brushed with activated charcoal-based products. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2023, 35, 1144–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez L, Martorell S. Características clinicoetiológicas y terapéuticas en dientes con lesiones cervicales no cariosas e indicadores epidemiológicos. Rev Mediciego. 2020, 26, e1215. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade I, Silva B, Turssi C, do Amaral F, Basting R, de Souza E, et al. Effect of whitening dentifrices on color, surface roughness and microhardness of dental enamel in vitro. Am J Dent. 2021, 34, 300–306. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood, J. Contact of Rough Surfaces: The Greenwood and Williamson/Tripp, Fuller and Tabor Theories. In Encyclopedia of Tribology; Wang, Q.J., Chung, YW., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2013; pp. 517–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana Í, Weiss G, Sakae L, Niemeyer SH, Borges A, Scaramucci T. Activated charcoal toothpastes do not increase erosive tooth wear. Journal of Dentistry. 2021, 109, 103677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero D, Pecci M, Guerrero J. Effectiveness and abrasiveness of activated charcoal as a whitening agent: A systematic review of in vitro studies. Annals of Anatomy - Anatomischer Anzeiger. 2023, 245, 151998. [CrossRef]

- Olek A, Klimek L, Bołtacz E. Comparative scanning electron microscope analysis of the enamel of permanent human, bovine and porcine teeth. J Vet Sci. 2020, 21, e83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koc V, Bagdatli Z, Yilmaz A, Yalçın F, Altundaşar E, Gurgan S. Effects of charcoal-based whitening toothpastes on human enamel in terms of color, surface roughness, and microhardness: an in vitro study. Clin Oral Invest. 2021, 25, 5977–5985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).