1. Introduction

Aging has become a major issue in the world's livelihood. According to the World Health Organization, by 2050, the global population aged 60 and above is expected to account for more than 22% of the total population [

1]. By the end of 2024, 310.31 million people aged 60 years and older will have accounted for 22.0% of the country's population, making older adults an important part of the country's population. Guzma found, based on data from two large national surveys, that 47% of American grandparents are involved in childcare [

2]. The 2017 International Longevity Center report noted that two-thirds of grandparents in the United Kingdom contribute to the upbringing of their grandchildren providing a financial contribution [

3]. In China, statistics show that 51.7% of seniors provide grandparental care [

4], much higher than the world average. With the implementation of China's comprehensive “three-child” policy, the miniaturization of family structure, and the mainstreaming of traditional family pensions, caring for grandchildren by the elderly has become a realistic choice for many families. The State Council's Guiding Opinions on Further Optimizing and Improving Positive Childbirth Support Policies and the National Health Plan for the Fourteenth Five-Year Plan both explicitly state that “localities are encouraged to take active measures to support grandparental care, family mutual assistance and other modes of care”.

Mental health is an important part of aging. Data from the World Health Organization 2024 shows that globally, about 15% of older people aged 60 and above suffer from depressive moods. The Blue Book “China Aging Development Report 2024 - Mental Health Status of Chinese Elderly People” shows that 26.4% of older people in China suffer from varying degrees of depressive symptoms, of which 6.2% have moderately severe depressive symptoms [

5]. The 2019 State Council's “Guiding Opinions on Promoting the Action for a Healthy China”, explicitly points out that it is necessary to actively carry out work related to mental health and geriatric health promotion with a view to healthy aging [

6]. At a time of increasing aging, paying attention to the mental health of the elderly and realizing a sense of well-being and joy in old age have become important tasks for comprehensively promoting healthy aging.

How older persons can “make a difference” through grandparental care brings a sense of novelty and enhances intergenerational relations, while at the same time raising the risk of environmental integration and uncertainty about their lifestyles. Theoretically, grandparental caregiving reduces the pressure on children, improves the well-being of the whole family, and improves one's psychological well-being. However, different ages, economic situations, family structures, children's work status, and other factors will lead to the grandparental caregiving behavior of the elderly showing obvious heterogeneity. Therefore, it is important to explore the impact of grandparental caregiving and the resulting changes in intergenerational relationships on the psychological health of the elderly, to examine the heterogeneity of the group caused by different factors [

6], to discuss whether grandparental caregiving can achieve a win-win situation that not only promotes the birth of a family, but also protects the rights and interests of the elderly, and to put forward targeted recommendations based on the strategy of positive aging.

On the eve of the Spring Festival in 2023, General Secretary Xi Jinping mentioned in his speech during his condolences to the cadres and masses at the grassroots level that “our society is aging more and more, and we must let the elderly have a happy old age.” This paper analyzes and compares the mental health status of two groups of older adults with and without grandparental caregiving behaviors by using the Psychological Condition Rating Scale (PCRS), examines the extent to which grandparental caregiving affects older adults' mental health and analyzes the mechanisms of the impact, and provides a comprehensive assessment taking into account endogeneity and self-selective bias, to provide a more nuanced explanation of grandparental caregiving in older adults' theoretical perspectives.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

2.1. The Internalization of Responsibility Theory and the Cultural Heterogeneity of Grandparental Caregiving

In Western societies, the process of individualization and patterns of economic practice have often weakened the social value and identity of grandparents [

3] (p. 2). In grandparental care models, grandparents are more often given the role of “being there” and “not interfering”, i.e., being available while not disrupting the parent-child relationship [

7]. As a result, grandparents tend to be in a relatively passive cultural norm. In contrast, in non-Western societies, especially in China, filial piety and the duty to care for parents have redefined the status of grandparents in the family [

8]. Among other things, the family-oriented culture emphasizes the bond of blood kinship and the patriarchal principle as the dominant one, forming the status regulations and behavioral norms of superiority, inferiority, superiority and superiority, and the order of seniority and juniority [

9]. This has given rise to the internalized theory of responsibility, which states that children and parents have an unconditional duty of care to each other and that the provision of grandparental care is also an internalized family responsibility [

10]. This cultural difference in the responsibilities of grandparental caregiving actors can backfire on the actors themselves. CHAN et al. [

11] note that grandparental caregiving intensity has a concave-curve relationship with health and well-being, with optimal intensity varying by culture: complementary caregiving is beneficial to dual-earner families in places such as Europe and the United States; economic resources in East Asia buffer against the adverse effects of primary caregiving on well-being; and in the United States there are differences in outcomes by ethnicity, with the relationship compounded by family roles and cultural differences. The relationship is further complicated by family roles and cultural differences in the United States.

2.2. The Impact of Grandparental Care on the Mental Health of Older Persons

Research on the impact of grandparental caregiving on the mental health of older adults is divided, and several competing theories currently exist in the academic community.

2.2.1. Role Optimization Theory

“Role optimization theory suggests that the role of grandparental caregiving, as an important component of the multiple social roles of older adults, contributes to positive emotional experiences, mitigates pressures and risks from other social roles, and enhances their overall psychological well-being [

12]. Based on the “use it or lose it” principle, taking on active caregiving roles and remaining socially engaged can slow the rate of cognitive decline and reduce the risk of cognitive impairment or depression in older persons [

13,

14]. This provides a theoretical basis for the positive relationship between grandparental caregiving and older adults' mental health: Jianguo Zhao6 demonstrated that grandparental caregiving significantly promotes older adults' mental health based on Maslow's hierarchy of needs theory; Shen et al. [

15] showed that older adults who provide grandparental care have better psychological well-being; Shuzhuo Li et al. [

16] showed that older adults' financial support for their children is beneficial to their subjective health; Fengzhen et al. showed that older adults' financial support for children is beneficial to their subjective health. Tsai [

17] noted that elders who continued or started caring for their grandchildren were happier and enjoyed life more than those who did not.

2.2.2. Role Burden Theory

“Role Burden Theory suggests that when older adults have difficulty balancing role conflicts under the demands of multiple roles, or when their role load exceeds their carrying capacity, they are prone to negative emotional experiences and that this long-standing “chronic stressor” can cause progressive damage to their health [

18]. This long-term “chronic stressor” can cause gradual damage to their health. The elderly who provide grandparental care have a new role as “grandparents” and are faced with the task of caring for their grandchildren, there will be a certain amount of conflict, transformation, and enhancement between the multiple roles, and the interactive process will also have an impact on their mental health that cannot be ignored [

19]. This theory supports the negative correlation between the two: Lindsey et al. [

20] point out that grandparents who are involved in multiple family roles have more significant symptoms of depression, which may be related to the conflict and stress between their different roles; Hughes et al. [

21] and Musil et al. [

22] point out that grandparental caregiving is likely to lead to the depletion of the energy of middle-aged and elderly people and increase the burden of family labor, which may lead to a significant decline in their mental health, which may in turn increase the risk of depression. Li et al. [

23] and Whitley et al. [

24] point out that grandparental caregiving reduces the frequency of daily social interaction among older adults, leading to economic depletion and family tension, which may cause physical or psychological stress to older adults.

2.2.3. The Theory of Proportionate Labor

The theory of proportionate labor points out that when the individual labor input is in the reasonable range, the pressure brought by labor is in the tolerable range, and can be transformed into positive motivation to optimize the behavioral performance; and when the labor input is insufficient or excessive, it will trigger physical and mental stress and accumulate over time, and once exceeding the threshold of the individual to withstand it, it will damage the health, i.e., the correlation between the labor input and the pressure is an inverted “U That is, the relationship between labor input and stress is an inverted “U” curve [

25]. The economics of diminishing marginal utility can also explain the theory: the mental health effects of grandparental care show dynamic changes with the intensity and duration of care and individual resources, and over-investment can be transformed into a burden due to resource depletion. This provides theoretical support for the complex relationship between the two: Baoqing Han [

26] and Yuyang Li et al. [

27] point out that as the duration of grandparental care grows, the positive effects of grandparental care on the mental health of the elderly decline, showing an inverted U-shaped trend of change. Qinghong He [

28] believes that grandparental care significantly enhances the well-being of grandchildren under the age of 60, and promotes attenuation or even inhibition at the age of 60 and above. Lianjie Wang [

29] showed that excessive caregiving is detrimental to health and is an exhausting and joyful complex experience. Runnan Zhi [

30] argues that older people's mental health is significantly enhanced only when they are within their means and subjectively willing to provide financial support to their children.

2.2.4. The Grandmother Hypothesis - an Analysis of Gender Heterogeneity

In the last decade, based on an interdisciplinary perspective that combines social science and evolutionary theory, Hawkes et al. [

31] have proposed the “grandmother hypothesis”, which suggests that the evolutionary roots of female menopause may lie in the motivation of older women to increase their survival rates by helping to raise their grandchildren. Lahdenperä et al. [

32] further suggest that the role of the grandmother has become a defining characteristic of the human family, regardless of the evolutionary reasons for menopause. Although the theory is still controversial, it provides interdisciplinary insights into understanding the more important role played by female older adults in grandparental caregiving: Lianjie Wang [

29] (p. 4) notes that grandparental caregiving has a more significant impact on female older adults. Yue Hong et al. [

33], after considering subgroup differences, noted that the mental health benefits of continuing care were particularly pronounced among urban grandmothers.

2.3. Intergenerational Exchange Theory - An Exploration of the Mechanisms of Influence

Unlike the Western “relay model”, the intergenerational exchange relationship in China is based on the principle of “raising children for old age” which is balanced and reciprocal and generally shows the characteristics of “two-way” and “feeding back” [

34,

35,

36]. Guangzong Mu et al. [

37] clearly define that the support of the younger generation includes both economic support and spiritual support. Based on this, the theory of intergenerational exchange suggests that in an environment where formal social support is insufficient, family members tend to form a mutual support network to maximize the satisfaction of individual and family needs through the exchange of resources [

38]. Nowadays, family old-age care is still the main mode in China, and the elderly have declining labor ability and lower income levels, thus, by undertaking grandparental care and other activities, they can reduce the time and energy spent on caring for their children by their offspring, and lower the opportunity cost of their offspring, thus realizing the optimal allocation of resources within the family. In exchange, the elderly can obtain material support and spiritual comfort from their children [

39]. This type of family cooperation system is based on the reciprocity mechanism, forming an intergenerational resource exchange model with implicit contractual attributes [

40]. In other words, older people often make intergenerational payments to their children by taking on the care of their grandchildren in return for the support provided by their children in their old age [

10] (p. 3). Relevant studies have confirmed that older adults who care for their grandchildren are more likely to receive intergenerational feedback from their children, including financial support and spiritual comfort [

38,

41] (p. 5).

2.4. Research Problem

Based on a multidimensional theoretical perspective, existing studies have systematically explored grandparental caregiving from three perspectives: cultural differences, specific influences, and influence mechanisms. From a comparative cultural perspective, the internalization of responsibility theory reveals the essential differences between Chinese and Western grandparental caregiving, with the West emphasizing the complementary and passive roles of grandparents, while China, influenced by its family-oriented culture, internalizes grandparental caregiving as a family responsibility. This difference confirms that exploring grandparental caregiving in the Chinese context has some specificity and theoretical significance in the world. In terms of specific impacts, the competing explanatory frameworks of optimization, burden and moderate labor theories, and the gender heterogeneity explained by the grandmother hypothesis highlight the complexity of the grandparental caregiving effect. This complexity is not yet recognized in the academic community, and more comprehensive sub-sample estimates are lacking. In terms of the impact mechanism, the intergenerational exchange theory provides a possible explanatory framework, but its appropriateness has not been fully verified. This paper thus attempts to explore the following questions based on previous work:

First, what kind of relationship does grandparental caregiving present with older adults' mental health?

Second, does this effect differ for older adults of different ages, genders, and household types?

Third, does intergenerational exchange theory play a role in the impact of grandparental caregiving on the mental health of older adults, and what kind of role does it play?

Fourth, how and why does grandparental caregiving based on a family-oriented culture contribute to the Chinese experience of the world's problems?

2.5. Theoretical Framework

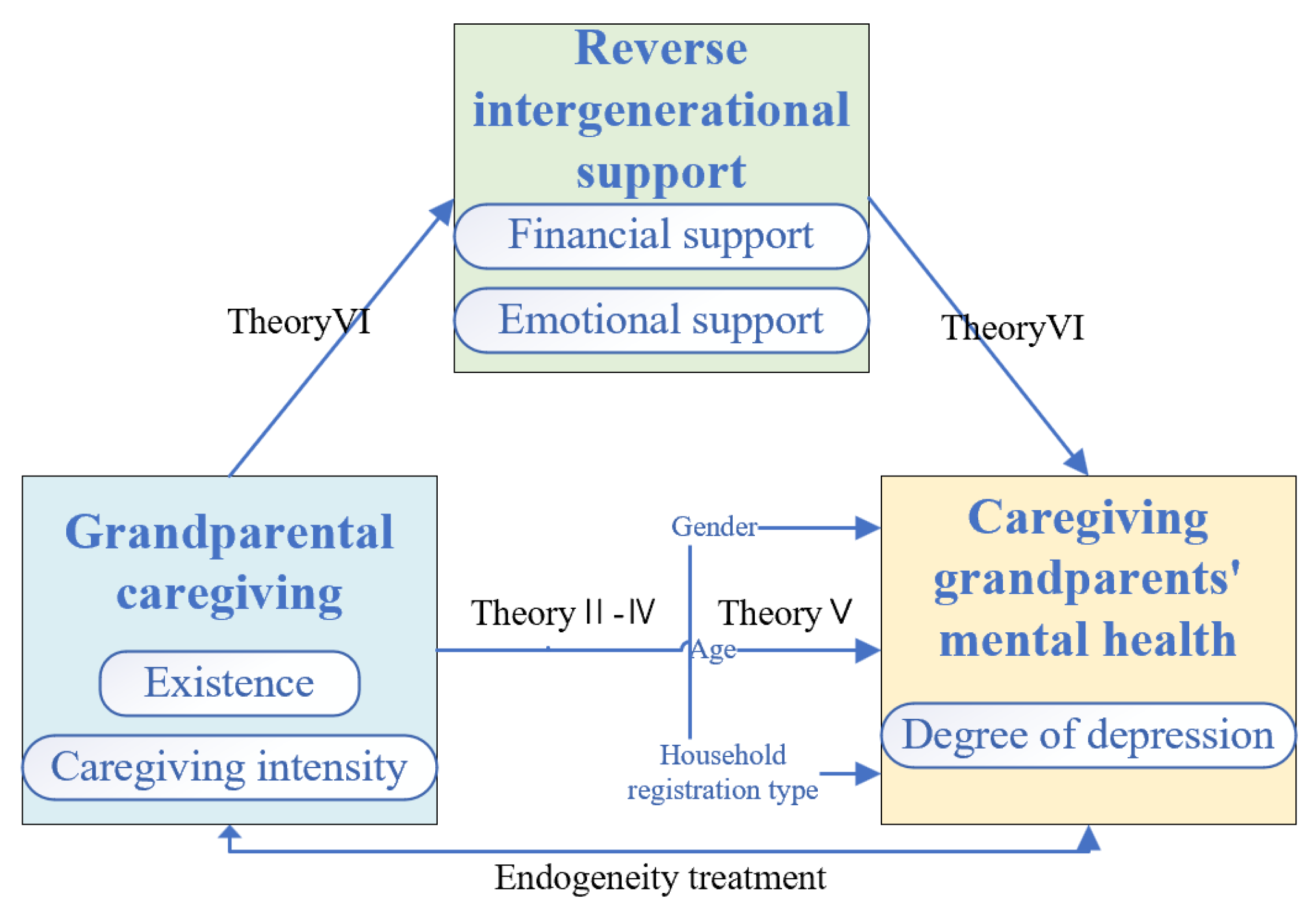

In order to answer the four questions raised in the previous section, firstly, this paper starts from discussing the existence of grandparental caregiving behaviors among the elderly, and compares whether there is a difference in the mental health of the two types of elderly groups that provide and do not provide grandparental caregiving behaviors; secondly, it examines the extent to which the intensity of grandparental caregiving affects the mental health of the elderly through the linear regression model, and reflects the mental health of the elderly in terms of depression scores; thirdly, to examine the extent to which different ages, genders, and domiciles affect mental health in terms of whether there is heterogeneity in the group of older people for whom grandparental care has been provided; and finally, to analyze the relationship between intergenerational economic support and spiritual comfort and the mental health of the elderly, and to elaborate the mediating role of intergenerational feedback between grandparental care and the mental health of the elderly.

This paper is based on the analytical framework proposed by scholars such as Carlos Cinelli and Chen Lu [

42] as shown in

Figure 1:

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Descriptions

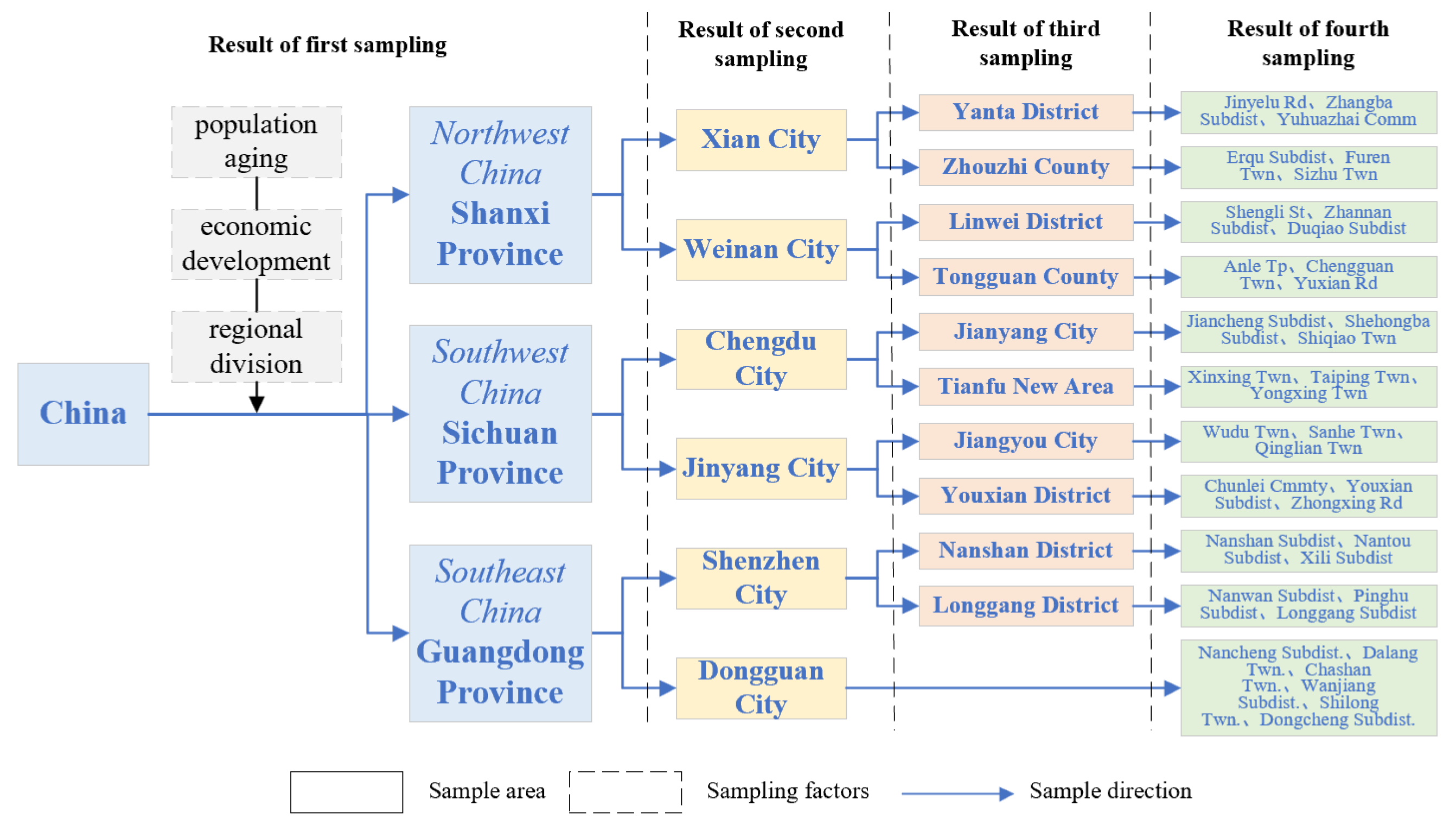

The data in this paper come from the July-September 2023 Xi'an Jiaotong University Urban and Rural Elderly Family Support and Psychological Condition Research Survey. The survey used a stratified multi-stage random sampling method, and the elderly aged 60 years and above in Shaanxi Province, Sichuan Province, and Guangdong Province were selected as the sampling population by considering age, economic, social, and other factors. The survey adopted the Scheaffer sampling formula, and 1600 subjects were selected for the questionnaire survey. According to the principle of stratified sampling, 253 people were selected from Shaanxi Province, 567 people from Sichuan Province, and 780 people from Guangdong Province, which were taken as the first stratum; 2 cities were selected as the second stratum by simple random sampling respectively; and 2 counties (districts) were selected as the third stratum by simple random sampling in the selected cities; Adopting whole cluster sampling, 3 streets (townships) were selected among counties (districts) as the fourth stratum, and finally 1224 valid questionnaires were obtained. At the same time, four representative cases were selected for in-depth interviews to assist in interpreting the research findings. Among them, the questionnaire set up a series of questions specifically for the family support and psychological condition of the elderly, which provided good data support for the research of this paper.

Figure 2.

Stratified sampling flowchart.

Figure 2.

Stratified sampling flowchart.

3.2. Variable Interpretation

Explained variable. The explanatory variable in this paper is the mental health of older adults, with depression scale scores as a proxy variable. The more authoritative definition of mental health was proposed at the Third International Health Conference in 1946 and refers to the ability to optimize the state of mind of an individual when he or she is not emotionally, physically, and intellectually at odds with others [

43]. The mental health performance of the elderly differs from other age groups, and physical symptoms such as decreased physical strength and insomnia appear. This paper refers to the research of Yadi Wang and other scholars, utilizing the questionnaire set up to assess the psychological status of “your emotional state last week” related to ten questions, including: “I am annoyed by some small things” and so on, and all the questions summarize the score ultimately fall in the 10-40 points assignment, making the respondents' psychological health interval. All the questions were scored in the range of 10 to 40, making the respondents' mental health scores negatively correlated with their level of depression.

Explanatory variables. The explanatory variable of this paper is grandparental care. The grandparental care model is a new intergenerational relationship model that distinguishes itself from the traditional model in China and the West, and in her study, Maojuan Che pointed out that parents raise the next generation of their children on their behalf, i.e. grandparental care [

44]. In order to enhance the explanatory strength, this paper refers to Reinkowski's research results to quantitatively assess grandparental care from two dimensions. The existence of grandparental caregiving is assessed by asking respondents, “In the past month, how many hours per week on average did you (and your spouse) spend caring for your grandchildren?” The respondents were asked “How many hours per week did you (and your spouse) spend caring for your grandchildren in the past month? If the answer is “0 hours/week”, it is assigned a value of 0, indicating no grandparental caregiving, while other answers are assigned a value of 1, indicating the existence of grandparental caregiving behavior. Caregiving Intensity: Measures the amount of time and energy that older adults devote to grandparental caregiving. Quantification of this dimension will be based on the specific frequency of caregiving activities by the respondent. 0 indicates no caregiving, 1 indicates low intensity (0 to 20 hours per week), 2 indicates medium intensity (20 to 40 hours per week), and 3 indicates high intensity (more than 40 hours per week).

Control variables. To reduce the omitted variable error in the study, this study draws on the methodology of researchers such as Baoqing Han and Shengjin Wang, and selects demographic characteristics and lifestyle variables such as age, gender, household registration, marital status, education level, and individual housing type as the main control variables.

Influence mechanism variables. This study focuses on two key impact mechanism variables: intergenerational financial support and intergenerational emotional comfort. To ensure the quantitative accuracy of intergenerational financial support, the question “How many dollars did your children support you throughout the year?” question and log transformed the total amount of financial support from all children. Intergenerational emotional comfort was measured using the question, “On average, how much time per week did your children spend caring for you (and your spouse) in the past month?” responses, with higher values indicating more frequent emotional comfort. The specific variables are described in

Table 1.

Table 1.

Variable settings and descriptions.

Table 1.

Variable settings and descriptions.

| Variable category |

Variable name |

Description of variables |

| Explained variable |

Psychological status score |

Continuous variables, based on the 10 questions of the scale, were assigned a score of 4, 3, 2, and 1 for the options “rarely or not at all (<1 day)”, “not too much (1-2 days)”, “sometimes or half the time (3-4 days)”, “most of the time (5-7 days)”, “sometimes or half the time (5-7 days)”, and “most of the time (5-7 days)”, respectively. ”, “Sometimes or half the time (3-4 days)”, and “Most of the time (5-7 days)” were assigned a value of 4, 3, 2, and 1, respectively. |

| Explanatory variables |

Care availability |

Dummy variable, presence of grandchild caregiving behaviors, 0=0 hours/week, 1=other response. |

| Care intensity |

Categorical variable, “How many hours per week, on average, did you (and your spouse) spend caring for your grandchildren in the past 1 month?”, 0=no care provided, 1=0 to 20 hours, 2=20 to 40 hours, 3=more than 40 hours. |

| Control variables |

Age |

Categorical variables, 1 = 60-69 years old, 2 = 70-79 years old, 3 = 80 years old and above. |

| Gender |

Dummy variable, 0=female, 1=male. |

| Household registration |

Dummy variable, 0=rural, 1=urban. |

| Marital status |

Dummy variables, 0 = unmarried, divorced, widowed, etc., 1 = in marriage. |

| Educational attainment |

Categorical variables, 1=elementary school and below, 2=junior high school, 3=high school/middle school, 4=junior college, 5=bachelor's degree and above. |

| Individual housing type |

Categorical variables, 1=reinforced concrete housing, 2=brick housing, 3=adobe housing, 4=bamboo and grass housing, 5=unit-built or pooled-funded housing, 6=self-built housing, 7=commercialized housing, 8=no rental housing. |

| Influence mechanism variables |

Intergenerational economic support |

Continuous variable based on the question “How many dollars did your children support you throughout the year?” This question was log-transformed to total financial support from all children. |

| Intergenerational emotional comfort |

Continuous variable based on the question “On average, how much time per week did your children spend caring for you (and your spouse) in the past month?” The question is taken to be the actual amount. |

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of relevant variables.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of relevant variables.

| Variable |

Full sample |

Providing grandparental care |

Not providing grandparental care |

| Mean |

Sd |

Mean |

Sd |

Mean |

Sd |

| Mental health |

18.14 |

5.48 |

18.01 |

5.43 |

18.28 |

5.54 |

| Grandparental care provision (Yes/No) |

0.51 |

0.50 |

1.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| Care intensity |

0.90 |

1.07 |

1.76 |

0.84 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| Age |

70.10 |

6.92 |

69.29 |

6.44 |

70.94 |

7.30 |

| Gender |

0.50 |

0.50 |

0.47 |

0.50 |

0.54 |

0.50 |

| Household registration |

0.47 |

0.53 |

0.50 |

0.55 |

0.44 |

0.50 |

| Marital status |

0.75 |

0.43 |

0.79 |

0.40 |

0.71 |

0.45 |

| Education level |

2.10 |

1.18 |

2.16 |

1.12 |

2.02 |

1.21 |

| Financial support from children |

5910.29 |

11004.41 |

6689.95 |

11900.07 |

5091.46 |

9921.78 |

| How many hours do your children spend on average per week providing care for you? |

14.89 |

30.65 |

17.43 |

27.83 |

12.24 |

33.16 |

| How many hours do you spend on average per week providing care for your grandchildren? |

18.43 |

42.37 |

35.99 |

53.61 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

| Self-evaluated mental status |

3.90 |

0 .88 |

3.96 |

0.89 |

3.83 |

0.87 |

| Self-evaluated physical status |

3.60 |

0 .97 |

3.68 |

1.00 |

3.51 |

0 .94 |

3.3. Modeling Approach

3.3.1. Baseline Model

This paper constructs a linear regression (OLS) benchmark model, referring to Grossman's health human capital model [

29] (p. 4), taking mental health as the core variable of the study, and adopting grandparental care as the independent variable, to quantitatively analyze the specific impact of grandparental care on the mental health of the elderly. The baseline model is shown in Equation (1):

where

is the mental health of the ith older adult;

is the intercept term;

is the grandparental caregiving variable for older adults;

is the control variable;

and

are the coefficients to be estimated; and

is the random perturbation term.

3.3.2. Propensity Score Matching (PSM)

The grandparental caregiving behaviors of the elderly are usually based on self-selection, and whether or not to implement grandparental caregiving mainly depends on their intergenerational perceptions, economic income status, and occupations, among other factors. Therefore, considering the potential endogeneity of sample selection bias, which makes the regression results lack reference value, this paper adopts the propensity score matching method of “counterfactual estimation” to solve the endogeneity problem caused by self-selection bias. Specifically, we divide the sample into treatment and control groups, and ensure that the two groups have the same range of values for the covariates. For an individual who belongs to the treatment group, similar individuals are found in the control group by matching the covariates and comparing the mental health status of the two groups with or without the provision of grandparental care. In this paper, a Logit model is used to more accurately estimate the probability of an individual being in the treatment group under different conditions, and the Logit model is shown in equation (2):

where

is the probability that an older person provides grandparental care;

is a covariate;

is the provision of grandparental care;

is a vector of parameters; and

is a cumulative distribution function. The net effect of the impact of grandparental care on mental health is analyzed by ATT and is shown in equation (3):

where

is the average treatment effect;

is the mental health status of older adults provided with grandparental care; and

is the mental health status of older adults not provided with grandparental care.

4. Results

4.1. Statistical Description

Of the older persons interviewed, 50.49% were men and 49.51% were women. Of these, 606 were 60-69 years old, 484 were 70-79 years old, and 134 were 80 years old or older; the rural population accounted for 655 or 53.5 percent, and the urban population 569 or 46.5 percent.

In terms of type of residence, 51.70% live with their spouse, 28.97% with their children, 18.36% with their grandchildren, and 0.96% with their nanny.

Table 3.

Residential type of the elderly.

Table 3.

Residential type of the elderly.

| Option |

Frequency (Person) |

Percentage (%) |

| Live with Spouse |

862 |

51.70 |

| Live with Children |

483 |

28.97 |

| Live with Grandchildren |

306 |

18.36 |

| Live with Nanny |

16 |

0.96 |

The survey shows that the intensity of care in rural areas is not significantly different from that in urban areas, but the proportion of those not providing care is larger in rural areas at 27.12% compared to 21.65% in urban areas.

Table 4.

Comparison of care intensity between urban and rural areas.

Table 4.

Comparison of care intensity between urban and rural areas.

| Care Intensity (h/week) |

Urban |

Rural |

Total |

| No Care Provided |

21.65% |

27.12% |

48.77% |

| (0,20] |

12.42% |

13.24% |

25.65% |

| (20,40] |

5.56% |

6.05% |

11.60% |

| More than 40 |

7.03% |

6.53% |

13.56% |

| Total |

46.65% |

53.35% |

100.00% |

4.2. Characterization of Changes in the Level of Impact

4.2.1. Base Regression Analysis

In this paper, a stepwise regression method is used to add control variables such as whether to provide grandparental care, intensity of care, and age and gender sequentially to the model to examine the changes in the degree of impact of grandparental care on the mental health of the elderly, as shown in

Table 5.

All three models showed significant differences, and the results of models (1) to (3) showed that when only the single variable of whether or not to provide grandparental care was available, the depression index showed a negative correlation with whether or not to provide grandparental care, which answered the question one, i.e., grandparental care has a positive effect on the mental health of the elderly, and confirms that grandparental care can help to improve the intergenerational communication between the elderly and their grandchildren, optimize the elderly's life in their twilight years and reduce their risk of falling into depression. However, the probability of depression increases when the intensity of care is taken into account.

About unrelated variables, in the case of age, the mental health of older persons declines with age, and in the case of gender, the depression index is generally lower among male older persons than among female older persons. In terms of regional differences, the mental health status of urban older adults was better than that of rural areas. In terms of marital status, the psychological status of married older persons is better than that of divorced or widowed older persons who do not have a spouse; in addition, there is a positive correlation between literacy and the psychological health of older persons.

4.2.2. Endogenous Treatment

Research suggests that grandparental caregiving enhances the mental health of older people and that mentally healthy people are more likely to participate in grandparental caregiving. Therefore, the baseline regression model may only reveal that there is a correlation between the two, but it does not clarify the causal relationship between them. In this study, in order to eliminate the endogeneity problem caused by bidirectional causality, we adopted the instrumental variable method. According to the literature analysis, the selection of instrumental variables needs to satisfy the following two hypothetical prerequisites: firstly, to ensure that there is a significant correlation between the variable and the core explanatory variables; and secondly, there is no direct influence relationship between the variable and the explanatory variables. On this basis, we rigorously processed and analyzed the relevant data. Based on the appropriate criteria for selecting instrumental variables and referring to the research results of Ku and other related scholars, this paper selects “whether to live with grandchildren” as an instrumental variable. This variable has a high correlation with the phenomenon of reverse parenting among the elderly but has no significant correlation with the mental health of the elderly. Therefore, this study utilizes the two-stage least squares (2SLS) method for parameter estimation, and shows the regression results of the first stage, as shown in

Table 6.

The study began by analyzing the impact of living with grandchildren on the intensity of caregiving among older adults. The first stage found a significant positive correlation between living with grandchildren and caregiving intensity, indicating that living with grandchildren significantly increases the likelihood of grandparental caregiving among older adults, confirming that the instrumental variables are highly correlated with the endogenous explanatory variables. The second stage of the analysis showed that even after addressing endogeneity, grandparental caregiving still had a significant impact on older adults' mental health. The robust DWH test for model heteroskedasticity, with a p-value of 0.7503, could not negate the exogenous relationship between reverse alimony and older adults' mental health, and identified the presence of endogenous explanatory variables.

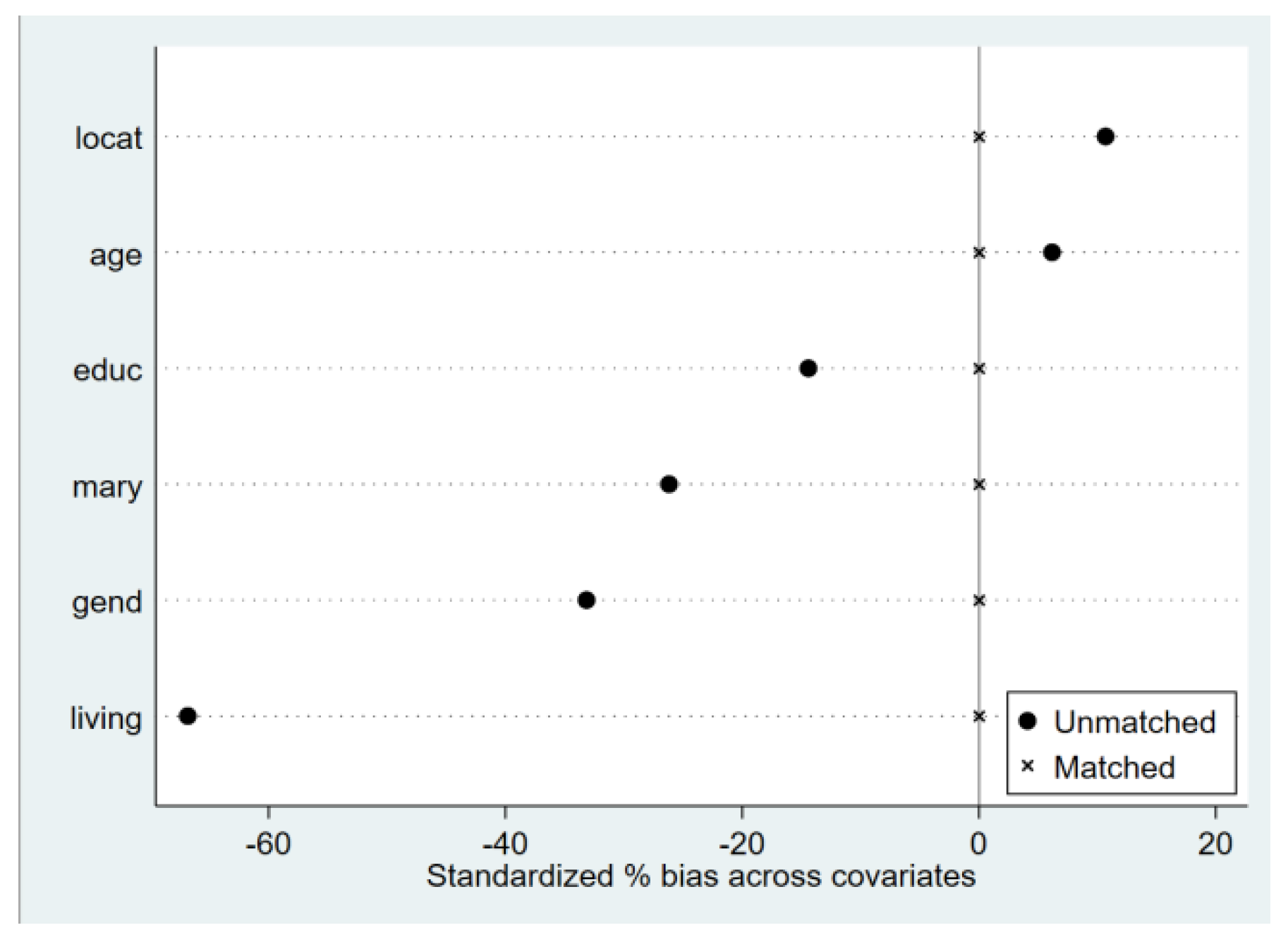

4.2.3. Selection Bias Treatment - A Study of Propensity Score Matching Estimation

The previous regression results show that grandparental caregiving behaviors enhance the mental health of older adults, but increase the probability of depression as the intensity increases. However, the process of sample selection for grandparental caregiving is also influenced by a variety of factors. Propensity score matching (PSM) is suitable for observational studies where randomized controlled trials are not possible and is particularly well suited to dealing with naturally occurring, multifactorial behavioral studies such as grandparental caregiving. It condenses information on multiple covariates into propensity scores, allowing the treatment and control groups to be similar in scores and effectively controlling for confounding factors. Compared with traditional regression analysis, PSM can significantly reduce selection bias, reduce sample heterogeneity through matching, and improve estimation stability and accuracy. In this study, three methods of neighbor matching, kernel matching, and radius matching were used, and Figure 4-2 presents the absolute values of bias before and after matching the samples of the impact of grandparental caregiving on mental health. Upon examination, the standardized deviation of most variables shrinks to less than 10%, and the sample loss is less than 1%, which strongly guarantees the validity of the estimation results of the impact of grandparental care on the mental health of the elderly. This indicates that the deviations of observable variables in the treatment and control groups are basically eliminated and the estimation results are valid.

Figure 3.

Standardized deviation of variables.

Figure 3.

Standardized deviation of variables.

Tables 7 demonstrate the results of the ATT treatment using propensity score matching. Notably, all three matching estimates are significant at the 1% statistical level, indicating that the conclusion that grandparental care has a positive effect on the mental health of older adults holds. In fact, after controlling for selective bias and endogeneity issues, the enhancement effect of grandparental caregiving on the mental health impact of older adults is weaker.

4.3. Mechanisms of the Impact of Grandparental Caregiving on the Mental Health of Older Persons

From the results analyzed above, we hereby hypothesize 2 hypotheses about the influencing mechanisms. Based on the intergenerational exchange theory, intergenerational financial support and intergenerational spiritual support may be affected by grandparental caregiving, which in turn affects the mental health of older adults. Accordingly, the following empirical evidence will be used to test the two hypothesized mechanisms.

The data in

Table 8 show that controlling for demographic and lifestyle variables, caregiving intensity is positively associated with intergenerational financial support and psychological comfort, which is statistically significant at the 1% level. Lu, J. et al. showed that elderly caregiving for grandchildren enhances reverse reflexivity, increases the chance of socialization, and improves psychological conditions.

Table 9 reveals the effects of intergenerational financial support and spiritual solace on the psychological health of the elderly. The findings show that children's financial support and intergenerational spiritual comfort are negatively correlated with depression scores, suggesting that both significantly reduce depression and promote mental health among older adults. The regression results in

Table 8 and

Table 9 show that grandparental caregiving is in line with the theory of intergenerational exchange as it realizes the enhancement of the mental health of the elderly through the improvement of financial support and spiritual comfort.

Table 8.

Effects of grandparental care on intergenerational economic support and intergenerational emotional comfort.

Table 8.

Effects of grandparental care on intergenerational economic support and intergenerational emotional comfort.

| Variable |

Children's Financial Support (Logarithm Function with +1) |

Average Weekly Care Time by Children for You |

| Care Intensity |

0.15***

(0.046) |

4.81***

(0.81) |

| Other Variables |

Controlled |

Controlled |

| _cons |

1.90***

(0.07) |

10.55***

(1.13) |

| N |

1,224 |

1,224 |

| R-squared |

0.0017 |

0.0282 |

Table 9.

Effects of intergenerational support on elderly mental health.

Table 9.

Effects of intergenerational support on elderly mental health.

| Variable |

Depression Score |

| Children's Financial Support (Log) |

-0.02***(0.006) |

|

| Weekly Care Time by Children |

|

-0 .39***(0.119) |

| Other Variables |

Controlled |

Controlled |

| _ cons |

1.56***(0.19) |

7.77***(3.03) |

| N |

1,224 |

1,224 |

| R - squared |

0.0056 |

0.0049 |

4.4. Cohort Differences

4.4.1. Subsample Estimation

According to the previous section, in the Chinese cultural context, the provision of grandparental care is more of a voluntary behavior of the elderly. Whether there is significant heterogeneity in the impact of grandparental caregiving is a research topic that deserves to be explored in depth. In this study, the sample is subdivided and estimated in terms of gender, age, and type of household registration, as shown in

Table 10. In terms of gender characteristics, grandparental caregiving has a more significant impact on the mental health of female older adults compared to males. Women tend to take on more family responsibilities, such as housework and caring for grandchildren, and such responsibilities fall largely on the shoulders of grandmothers. In terms of age, this paper categorizes the elderly into three groups: 60-69 years old, 70-79 years old, and 80 years old and above, and the results show that grandparental caregiving significantly promotes the mental health of the elderly aged 70-79 years old, has a more significant impact on the elderly aged 60-69 years old, and has an insignificant effect on the elderly aged 80 years old and above. Most of the elderly aged 80 and above are no longer sufficiently well off to take on the burden of caring for their grandchildren, and thus the provision of grandparental care may become a burden for the elderly. According to household data, grandparental care has a significant impact on the mental health of rural older persons, but not in urban areas. In rural areas, where the family concept of “raising children for the sake of old age” and “bringing up grandchildren” is deeply entrenched, the elderly bear the main responsibility for grandparental care, and with the departure of the rural youth labor force, there are more elderly residents in rural areas in general.

4.4.2. Robustness Testing

In this paper, we conduct robustness tests in two ways: (1) Because grandparental caregiving and age are correlated, to correct for the nonlinear effect of age, we add the squared and cubic terms of age to the model.

Table 11 After the inclusion of age squared and cubed, caregiving intensity still has a significant effect on the mental health of older adults (1% significance level), confirming the stability of the baseline regression. (2) The replacement variable method was used to reanalyze the model by including self-assessed psychological status as a proxy indicator. In this process, we used the following question, “How do you rate your psychological status?” In this process, we used the following question: “How do you rate your psychological condition?” to answer the question, given that self-assessed psychological condition as an ordered categorical variable, “very poor, relatively poor, average, relatively good, very good” corresponds to a score of 1 to 5, respectively, and the higher the value assigned indicates that the older person's self-assessed psychological condition is better. In this study, the ordinary least squares (OLS) model and ordered probit model were used for regression analysis of different variables.

Table 12 shows that self-assessed psychological status has a significant effect on the mental health of older adults under both model settings, further confirming the robustness of the study findings.

Table 11.

Robustness test with nonlinear age variables.

Table 11.

Robustness test with nonlinear age variables.

| Variable |

Depression Score (1) |

Depression Score (2) |

Depression Score (3) |

| Care Intensity |

-0.20***

(0.06) |

-0.23***

(0.06) |

-0.25***

(0.06) |

| Age |

0.0636***

(0.019) |

1.09***

(0.30) |

9.47*

(4.00) |

| Age Squared / 100* |

|

-0.12***

(0.03) |

-0.12***

(0.03) |

| Age Cubed / 1000 |

|

|

0.00

(0.001) |

| Controlled Variables |

Controlled |

Controlled |

Controlled |

| cons |

13.86***

(1.63) |

-22.76***

(13.46) |

-224.94

(104.63) |

| N |

1,224 |

1,224 |

1,224 |

| R - squared |

0.0089 |

0.0150 |

0.0180 |

Table 12.

robustness test with alternative dependent variable.

Table 12.

robustness test with alternative dependent variable.

| Variable |

Care Intensity |

Controlled Variables |

_ cons |

N |

R - squared |

| Self-rated Mental Health |

0.05***

(0.002) |

Controlled |

3.85***

(0. 03) |

1,224

|

0. 040 |

5. Discussion

Grandparental care has become a common phenomenon in the context of global aging and family structure transformation. Studying its impact on the psychological health of the elderly can not only fill the theoretical gaps in the study of cross-cultural family relations and geriatric psychology but also provide empirical evidence for countries to formulate family support policies and optimize the elderly service system, which is of far-reaching significance in promoting intergenerational harmony and sustainable development of the society. In this paper, we use regression analysis to reveal the complexity of the impact of grandparental caregiving on the mental health of the elderly, adopt the instrumental variable method and propensity to match scores to address the endogeneity problem, and at the same time carry out the sub-sample estimation and robustness test, we can draw the following conclusions: (1) Grandparental caregiving helps to alleviate the depressive condition of the elderly, and positively affects their mental health. After controlling for endogeneity and conducting robustness tests, the findings remain unchanged. This suggests that intergenerational caregiving is not only a responsibility but also an emotional support and enjoyment. (2) It was found that the positive effects of intergenerational caregiving on the mental health of older adults diminish as the intensity of caregiving increases, which may eventually lead to negative effects. (3) According to the results of the sub-sample assessment, grandparental caregiving has a more significant impact on the mental health of female older adults and significantly promotes the mental health of older adults aged 70-79, which can significantly improve the mental health of rural older adults. (4) In addition to the direct impact, grandparental financial support from children and intergenerational spiritual comfort indirectly enhanced the mental health of older people, emphasizing the multiple impact mechanisms in intergenerational relationships, which is in line with the concept of social support, that is, intergenerational support within the family is an important way to improve the well-being of older people. This urges children and grandchildren to strengthen emotional communication with their elders so that their children's role of emotional support can be maximized and the intensity of grandparental caregiving for older persons can be appropriately reduced.

6. Conclusions

Comparing different studies, the results of this study have both similarities and differences with the findings of many studies. In terms of positive impacts, they are consistent with numerous studies that concluded that grandparental caregiving promotes the mental health of older adults. However, there are differences in the degree of impact and specific mechanisms, with some studies emphasizing that grandparental care improves older adults' mental health through increased socialization, whereas the present study highlights the role of financial support and emotional comfort more prominently. As a whole, the mental health of older persons is closely related to family and social factors, and this paper makes the following policy recommendations.

(1) At the governmental level, encourage and support the “active aging” of older persons through grandparental care. Government incentives can repair ruptures in family relationships, which makes grandparental support for parents by offspring not only a form of compensation for their parents' mutual care but also an act based on maintaining the bonds of family kinship. In terms of finances, we should learn from the Japanese system of “childcare support grants” and set up a special “subsidy for grandparental caregiving families,” reduce or waive personal income tax for grandparental caregiving families and implement stepped subsidies for families with multiple children or rural families, to encourage more older people to join the ranks of intergenerational caregivers. In the area of social security, further expand pension insurance. In the area of social security, further expand the coverage of old-age insurance, refer to the German nursing insurance model, include grandparental care in the scope of long-term care insurance payments, increase the number of pilot cities for long-term care insurance policies, and gradually expand them nationwide, in particular to meet the diversified needs of older women for medical care and old-age care, and legislate on old-age security in rural areas [

45], organically combining formal social and intergenerational support [

46] to ensure that older persons receive adequate material and spiritual support during the grandparental caregiving process. At the policy level, a flexible work system that is “birth-friendly and age-friendly” has been developed to increase parental involvement in child-rearing, thereby reducing the burden of grandparental care on older persons [

47].

(2) At the social level, encourage social organizations, enterprises, and volunteers to provide multi-body “healthy aging” elderly care. First, to build a diversified elderly care service supply system with home care as the main focus, community support, and institutions as the supplement [

48], with the community as the carrier, community workers and volunteers provide special help for the elderly in grandparental care, such as physical examination, emotional communication, and assistance in handling, etc., to alleviate the mental pressure of the elderly, and to form a positive interaction between the “care of the elderly” and the “raising of grandchildren”. This will alleviate the mental stress of the elderly and truly create a positive interaction between “caring for the elderly” and “raising grandchildren” [

49]. Secondly, we should strengthen public childcare services and learn from Denmark's experience in building facilities for “integrating care for the elderly and children”, such as establishing specialized places in the community to integrate care for the elderly and children, and encouraging the elderly to provide grandparental care services for other families through “time banks”. At the same time, social support activities such as parenting skills instruction and knowledge seminars are provided to help the elderly to better carry out their daily social activities and to maintain a positive attitude and a high level of personal autonomy [

50].

(3) At the family level, establishing the value of “taking care of the elderly” and “raising grandchildren”. On the one hand, it encourages the elderly to actively take care of their grandchildren. On the other hand, adult children are guided to actively provide financial support, life care, and emotional comfort to their parents [

51]. Family old-age care can play out the advantages that other old-age care modes cannot be compared, family members should pay attention to the emotional aspects of the elderly's demands, to increase daily communication and exchange of spiritual support, for the elderly in rural areas to adopt a special method of intergenerational support for emotional communication. Children and grandparents can, within their means, provide two-way support to enhance family interactions, so that older persons can enjoy the joys of family life rather than the burdens of family life.

7. Limitations

Considering the limitations of the actual survey in this paper, this study still has some limitations. In terms of the research sample, limited by research resources and time, the sample coverage is not broad enough to fully represent the situation of all the elderly in China, especially those in some special areas. In terms of research methodology, questionnaires and interviews were mainly used, which made it difficult to comprehensively capture the dynamically changing psychological state in the process of grandparental caregiving. In the future, this study will continue to expand the sample to cover older adults from different regions, cultural backgrounds, and family structures; at the same time, it will adopt professional mental health monitoring techniques, such as the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD), to more scientifically and objectively measure the psychological status of older adults; and, it will strengthen the dynamic tracking research on the process of grandparental caregiving of individual individuals, to analyze the mechanisms that affect the psychological health of older adults.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Han Hu, Wei Zeng and Ran Liu; Data curation, Han Hu; Formal analysis, Wei Zeng and Ran Liu; Funding acquisition, Han Hu; Investigation, Han Hu, Wei Zeng and Ran Liu; Methodology, Han Hu, Wei Zeng and Ran Liu; Project administration, Wei Zeng; Resources, Han Hu; Software, Wei Zeng and Ran Liu; Supervision, Han Hu; Validation, Han Hu and Wei Zeng; Visualization, Wei Zeng and Ran Liu; Writing – original draft, Wei Zeng and Ran Liu; Writing – review & editing, Han Hu. All authors will be updated at each stage of manuscript processing, including submission, revision, and revision reminder, via emails from our system or the assigned Assistant Editor.

Funding

This research was funded by National Social Science Foundation of China (NSSFC), grant number 22CRK014.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Xi’an Jiaotong University (2016-416: 30 June 2016).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to (specify the reason for the restriction).

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used Stata for the purposes of data analysis. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PSM |

Propensity Score Matching |

| OLS |

Ordinary Least Square |

| ATT |

Average Treatment Effects on Treated |

| 2SLS |

Two Stage Least Square |

References

- Chang, A.Y.; Skirbekk, V.F.; Tyrovolas, S.; Kassebaum, N.J.; Dieleman, J.L. Measuring population ageing: an analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Public Health 2019, 4(3), e159-e167. [CrossRef]

- Guzman, R. Ethnic differences in grandparental child care arrangements. Journal of Family Issues 2004, 25(6), 770-792.

- Buchanan, A.; Rotkirch, A. Twenty-first century grandparents: global perspectives on changing roles and consequences. Contemporary Social Science 2018, 13(2), 131–144. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.D. Research on the impact of intergenerational care for grandchildren on the mental health of middle-aged and elderly people. Scientific Decision-making 2018, (09), 47-68.

- Gao, C.Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, Q.X.; Xin, T. China Aging Development Report (2024), 1st ed; Social Sciences Academic Press: Beijing, China, 2024.

- Zhao, J.G.; Guan, W.; Wang, J.J. Impact of "reverse feedback" on the mental health of the elderly. Journal of Jinan University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition) 2022, 44(02), 39-55.

- Harper, S.; Ruicheva, I. Grandmothers as Replacement Parents and Partners: The Role of Grandmotherhood in Single Parent Families. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships 2010, 8(3), 219–233. [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, A. Grandparenthood: Its Role in Older People's Lives and Its Significance for Policy and Practice. In Grandparents in Cultural Context, 1st ed.; Shwalb, D., Hossain, Z., Eds.; Routledge: New York, United States, 2017; pp. 235.

- Liang, S.M. The Characteristics of Chinese Culture, 1st ed; The Commercial Press: Beijing, China, 2018.

- Tao, T.; Liu, W.L.; Sun, M.T. Intergenerational Exchange, Duty Internalization, or Altruism—Influence of Grandparental Care on the Elderly's Endowment Willingness. Population Research 2018, 42(5), 56-67.

- Chan, A.C.Y.; Lee, S.K.; Zhang, J.; Banegas, J.; Marsalis, S.; Gewirtz, A.H. Intensity of Grandparent Caregiving, Health, and Well-Being in Cultural Context: A Systematic Review. Gerontologist 2023, 63(5), 851-873. [CrossRef]

- Szinovacz, M.E.; Davey, A. Effects of retirement and grandchild care on depressive symptoms. Int J Aging Hum Dev 2006, 62(1), 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Salthouse, T.A. Theoretical perspectives on cognitive aging, 1st ed; Psychology Press: New York, America, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.T.; Kubzansky, L.D.; LeWinn, K.Z.; Lipsitt, L.P.; Satz, P.; Buka, S.L. Childhood cognitive performance and risk of generalized anxiety disorder. International Journal of Epidemiology 2007, 36(4), 769-775. [CrossRef]

- Shen, K.; Yang, X.Y. Caring for Grandchildren and Life Satisfaction of Grandparents in China. Aging and Health Research 2022, 3, 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Song, L.; Feldman, M.W. Intergenerational Support and Subjective Health of Older People in Rural China: a Gender-based Longitudinal Study. Australian Journal of Ageing 2009, 28(2), 81-86. [CrossRef]

- Tasi, F. J. The Maintaining and Improving Effect of Grandchild Care Provision on Elders' Mental Health: Evidence from Longitudinal Study in Taiwan. Archives of Gerontology & Geriatrics 2016, 64, 59-65.

- Pearlin, L.I.; Mullan, J.T.; Semple, S.J.; Skaff, M.M. Caregiving and the Stress Process: An Overview of Concepts and Their Measures. The Gerontologist 1990, 5, 583-594. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Han, Y.D.; Mao, W.Y.; Lee, Y.; Chi, I. The Impact of Grandchild Care Experience on the Physical Health of Rural Older Adults. China Rural Economy 2016, (7), 81-96.

- Baker, L.A.; Silverstein, M. Depressive Symptoms Among Grandparents Raising Grandchildren: The Impact of Participation in Multiple Roles. J Intergener Relatsh 2008, 6(3), 285-304. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M.E.; Waite, L.J.; Lapierre, T.A.; Luo, Y. All in the Family: The Impact of Caring for Grandchildren on Grandparents’ Health. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 2007, 62(2), 108-119. [CrossRef]

- Musil, C.M.; Ahmad, M. Health of Grandmothers: A Comparison by Caregiver Status. Journal of Aging and Health 2002, 14(1), 96-121.

- Li, S.; Xu, H.; Li, Y. Influence of Grandparenting Stress, Sleep Quality, and Grandparenting Type on Depressive Symptoms among Chinese Elderly Who Care for Their Grandchildren: A Moderated-mediation Study. Current Psychology 2021, 5, 1-11.

- Whitley, D.M.; Kelley, S.J.; Sipe, T.A. Grandmothers Raising Grandchildren: Are They at Increased Risk of Health Problems? Health & Social Work 2001, 26(2), 105-114.

- Shi, J.Z. The Related Theories and Realization Paths of Moderate Labor under the New Normal. China Labor 2015, (20), 50-55.

- Han, B.Q.; Wang, S.J. The Impact of Grandchild Care on the Health of Middle-aged and Elderly Adults. Population Research 2019, 43(4), 85-96.

- Li, Y.Y.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, C.C. Welfare or Burden: The Impact of Grandparental Care Intensity on Older Adults' Multidimensional Health. Chinese Health Service Management 2025, 42(3), 334-338.

- He, Q.H.; Tan, Y.F.; Peng, Z.C. The Impact of Grandparental Care on Grandparents' Health—An Empirical Analysis Based on CHARLS Data. Population and Development 2021, 27(2), 1-11.

- Wang, L.J. Promotion or Inhibition: The Impact of Grandparental Care on the Physical and Mental Health of Middle-aged and Elderly Adults. Journal of Yunnan Minzu University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition) 2022, 39(4), 51-63.

- Zhi, R.N. The Impact of Intergenerational Support on the Mental Health of Older Adults. East China Normal University: Shanghai, China, 2020.

- Hawkes, K.; O'Connell, J.F.; Jones, N.G.; Alvarez, H.; Charnov, E.L. Grandmothering, menopause, and the evolution of human life histories. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1998, 95(3), 1336-9. [CrossRef]

- Lahdenperä, M.; Gillespie, D. O. S.; Lummaa, V.; Russell, A. F. Severe intergenerational reproductive conflict and the evolution of menopause. Ecology Letters 2012, 15(11), 1283-1290. [CrossRef]

- Yue, H.; Xu, W. Continuity and Change in Grandchild Rearing and the Risk of Depression Among Chinese Grandparents: New Evidence From CHARLS. Frontiers in Public Health 2023, 11.

- Sun, J.J.; Zhang, H.K. Analysis of the Status and Influencing Factors of Chinese Older Adults Caring for Grandchildren. Population and Economics 2013, (4), 70-77.

- Wu, L.L.; Sun, Y.P. The Impact of Changes in Family Intergenerational Exchange Patterns on Mental Health of the Elderly. Chinese Journal of Gerontology 2003, (12), 803-804.

- Fei, X.T. The Issue of Elderly Support in the Change of Family Structure—Re-discussion on the Change of Chinese Family Structure. Journal of Peking University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition) 1983, (3), 7-16.

- Mu, G.Z. Challenges Faced by Family Endowment and Social Countermeasures. Academic Journal of Zhongzhou 1999, (1), 88-91.

- Song, L.; Li, S.Z.; Li, L. Study on the Impact of Providing Grandchild Care on the Mental Health of Rural Older Adults. Population and Development 2008, 14(3), 10-18.

- Croll, E.J. The intergenerational contract in the changing Asian family. Oxford Development Studies 2006, 34(4), 473-491. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.H.; Wu, Y.X. "Community Rationality" and the Current Situation of Family Endowment in Rural China. Exploration and Free Views 2003, 1(2), 23-25.

- Cong, Z.; Silverstein, M. Intergenerational Support and Depression among Elders in Rural China: Do Daughters-In-Law Matter? Journal of Marriage and Family 2008, 70(3), 599-612.

- Chen, L.; Yang, B.Y.; Jing, R.T.; Liu, P. The Relationship among Internal Social Capital of Top Management Teams, Team Conflict, and Decision-making Effectiveness—A Literature Review and Theoretical Analytical Framework. Nankai Business Review 2009, 12(6), 42-50.

- Zhang, X. Study on the Impact of Mental Health Status of Older Adults on Their Health Consumption.Shandong University: Jinan, China, 2020.

- Xiong, B., Shi, R.B. Reanalysis of the Types of Family Intergenerational Support for Rural Older Adults—Based on a Survey of Two Regions in Hubei Province. Population and Development 2014, 20(3), 59-64.

- Luo, J.; Cui, M. For Children or Grandchildren?—The Motivation of Intergenerational Care for the Elderly in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023, 20(2),1441. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Li, C.; Wang, J. The impact of intergenerational support on older adults’ life satisfaction in China: Rural-urban differences. Healthcare and Rehabilitation 2025 1(1), 100011. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.Y. A Study on the Mechanism of the Effect of Intergenerational Parenting Intensity on the Life Satisfaction of Older Adults—An Empirical Analysis Based on CLASS (2018). Aging Research 2023, 10(3), 903-912.

- Jiang, Z.; Liu, H.; Deng, J.; Ye, Y.; Li, D. Influence of intergenerational support on the mental health of older people in China. PLoS One 2024, 19(4), e0299986. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, W. Does grandchild care intention, intergenerational support have an impact on the health of older adults in China? A quantitative study of CFPS data. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1186798. [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Zhan, X.; Wu, M. From Financial Assistance to Emotional Care: The Impact of Intergenerational Support on the Subjective Well-Being of China’s Elderly. J Happiness Stud 2025, 26, 17. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Peng, S. Cognitive differences and influencing factors of Chinese People’s old-age care responsibility against the aging background. Healthcare (Basel) 2021, 9, 72. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).