Submitted:

10 June 2025

Posted:

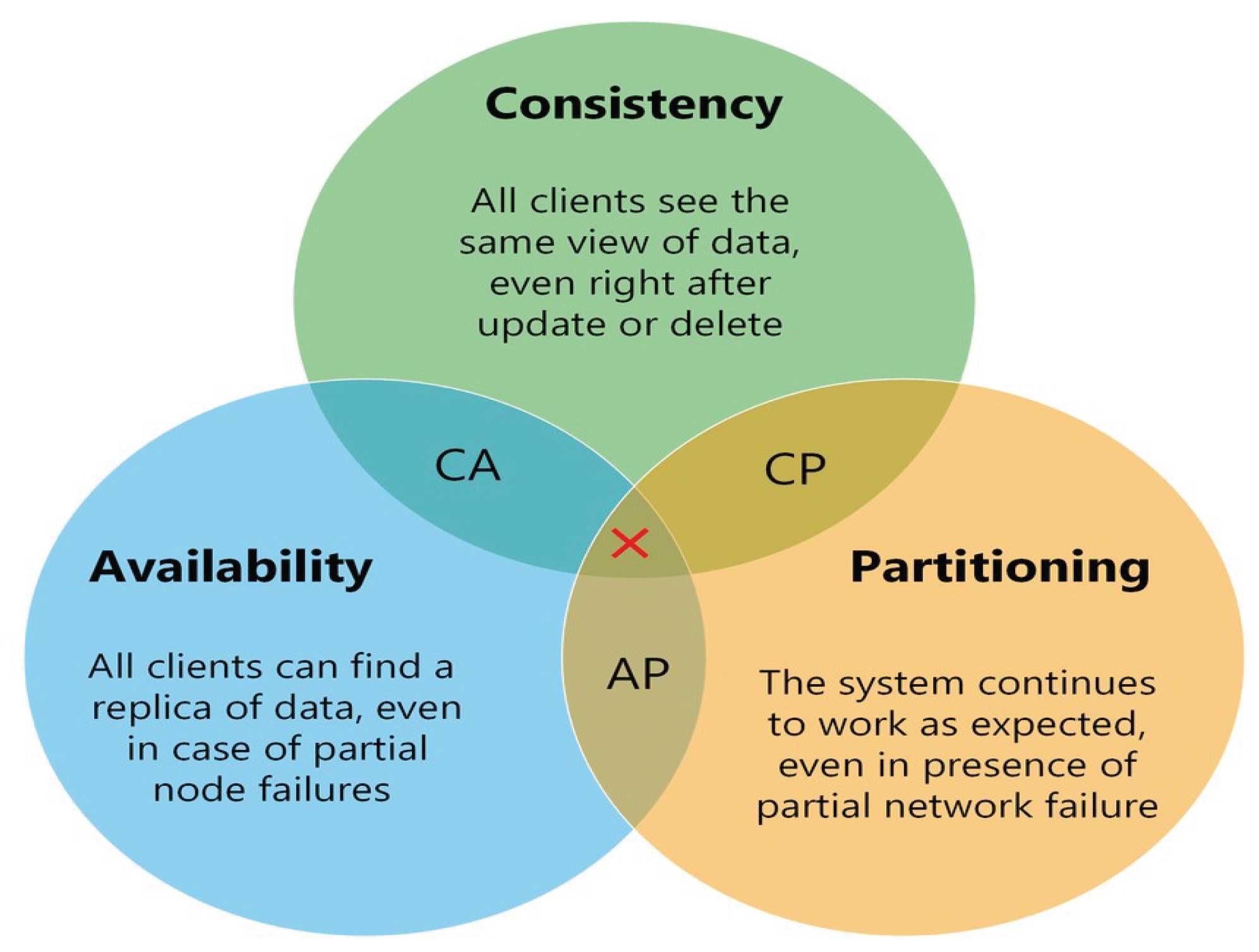

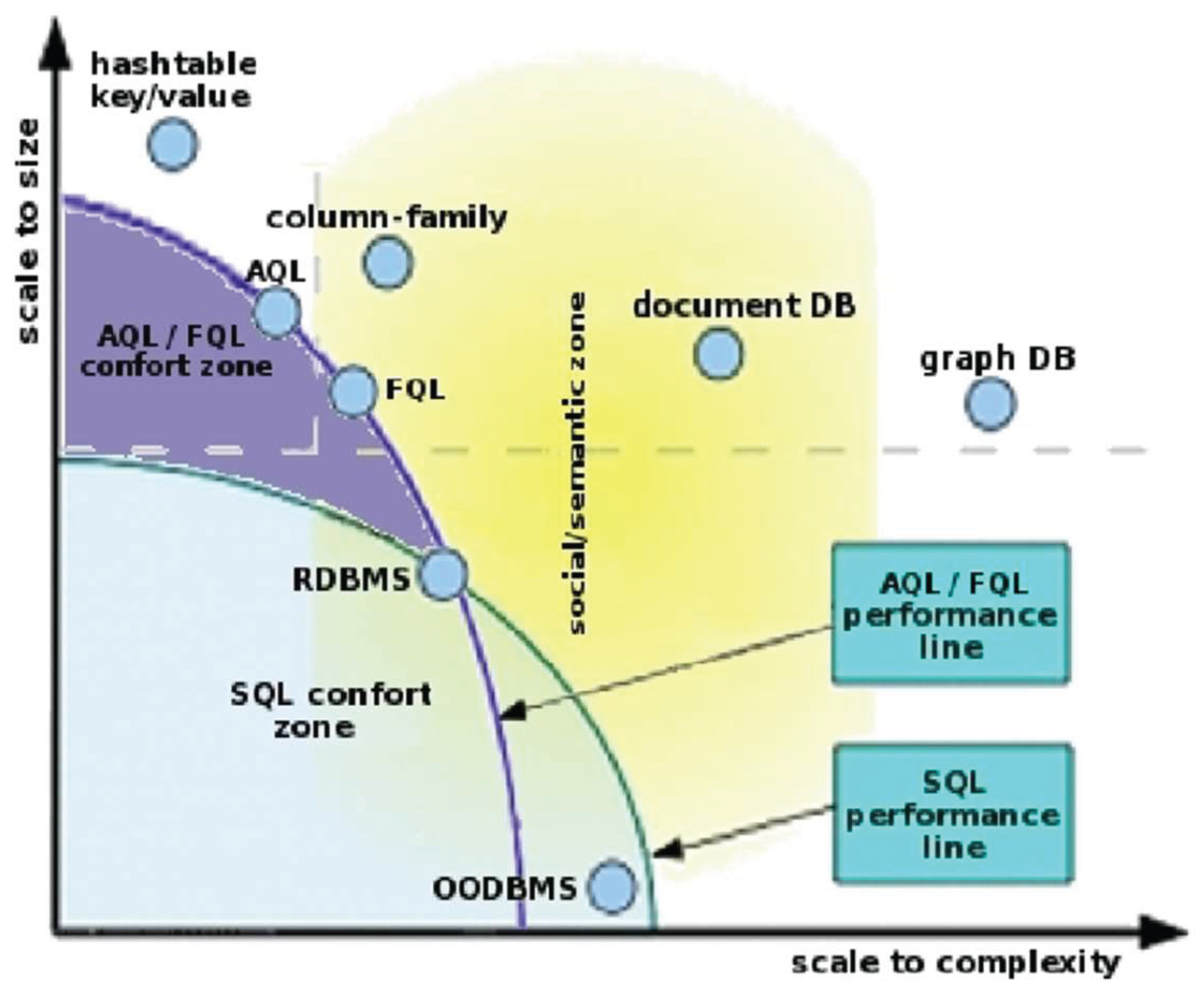

11 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

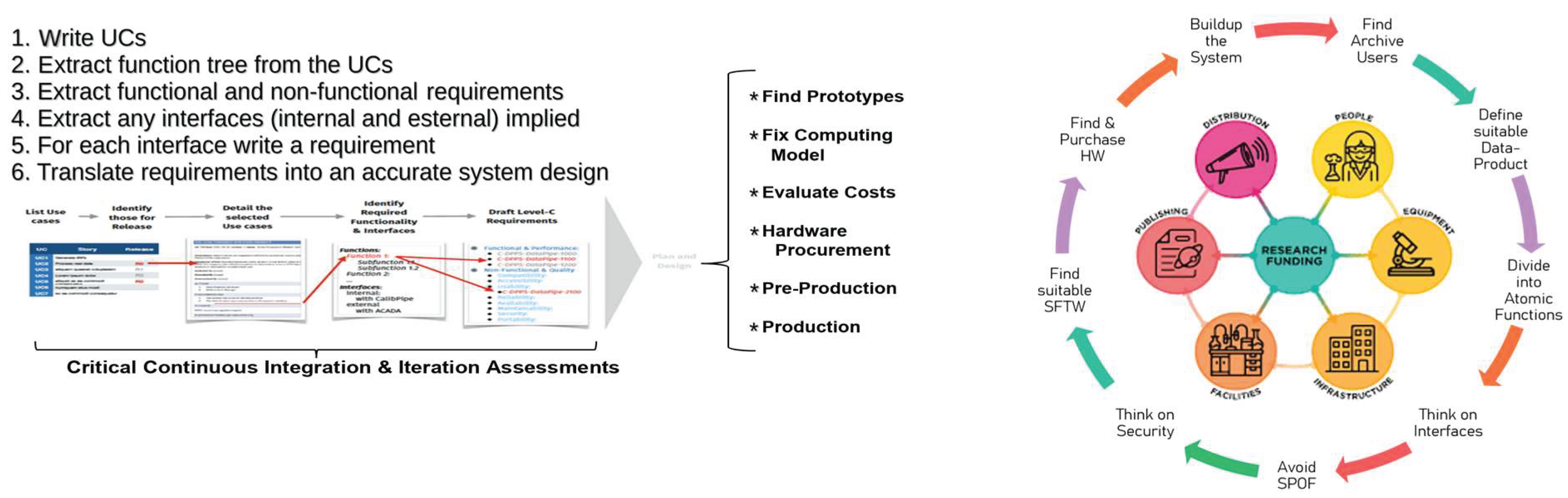

1. Good and Bad Practices in Data Management Projects

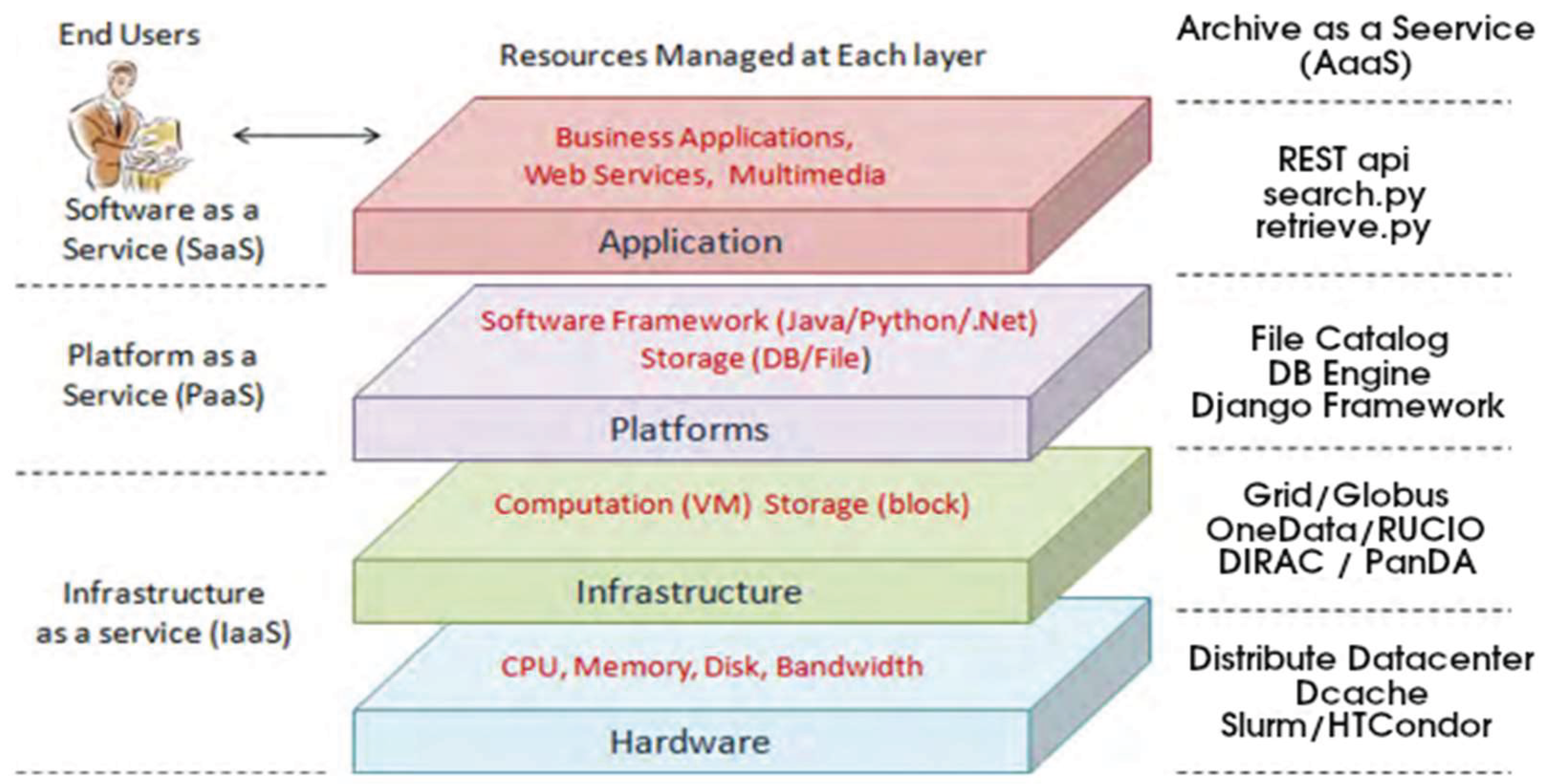

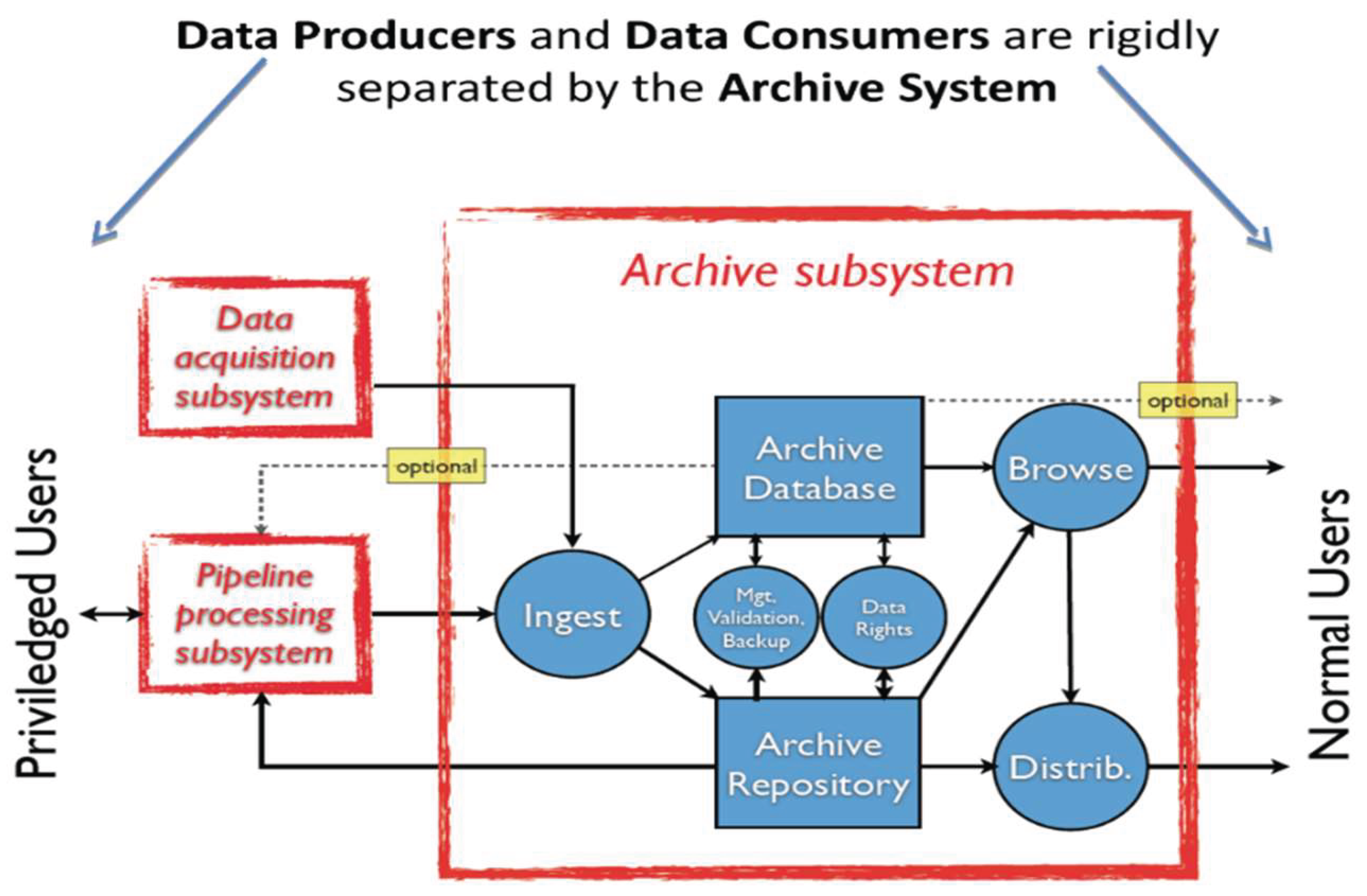

2. Storage Architecture in Archival Systems: Centralized vs Distributed Approaches

3. Selecting the Appropriate Database Architecture for Archival Systems

- Prioritizing Consistency may halt reads or writes to prevent divergence, sacrificing availability.

- Prioritizing Availability ensures responsiveness, but may serve outdated or inconsistent data.

- Prioritizing Partition Tolerance allows continued operation despite communication failures, though it may compromise either consistency or availability.

- Simplify the data model or queries.

- Scale up the hardware infrastructure.

- Migrate to a different database family—such as a document-oriented (NoSQL) system.

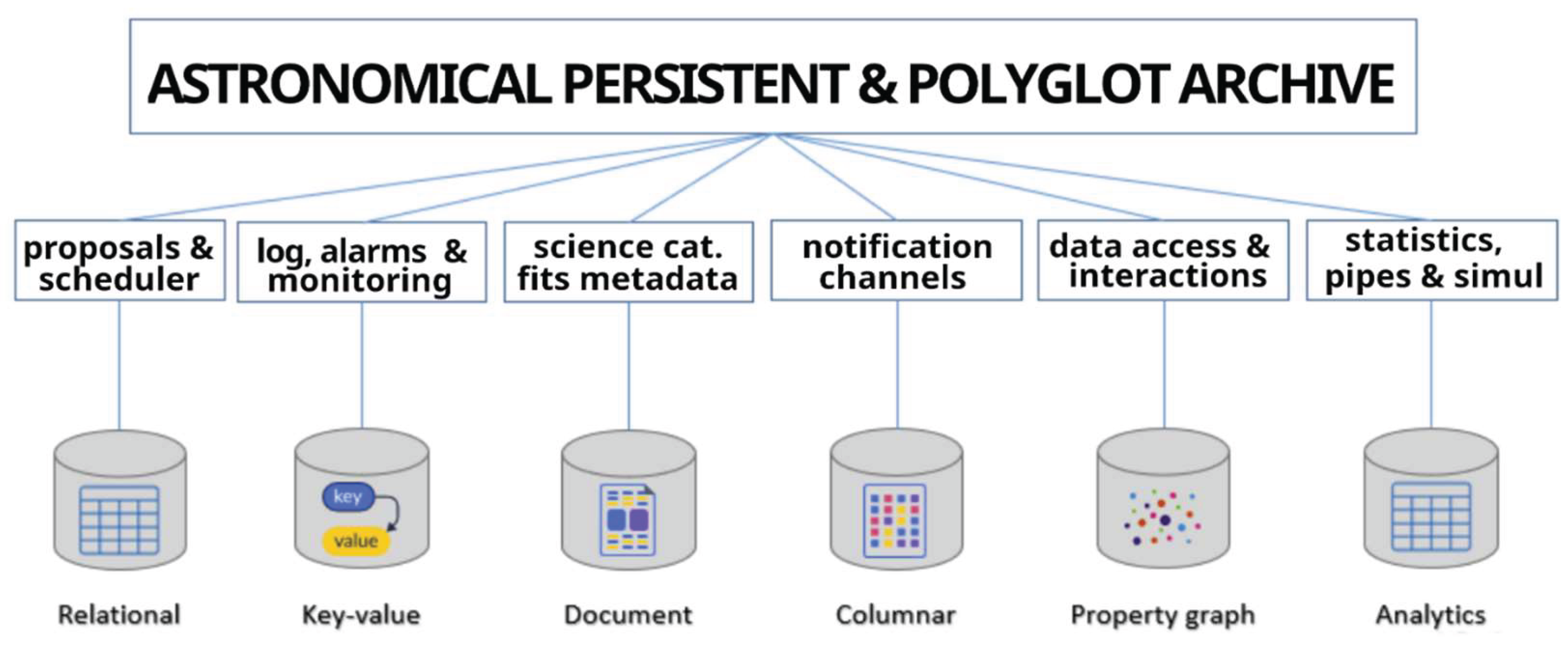

4. Polyglot Persistence in Modern Archive Systems

- Relational databases (e.g., PostgreSQL, MariaDB) for structured data like observation proposals.

- Document-oriented databases (e.g., MongoDB) for semi-structured metadata.

- Column stores (e.g., Cassandra) for streaming telemetry.

- Key-value stores (e.g., Voldemort) for fast-access logs.

- Graph databases (e.g., Neo4j, Cosmos DB) for user interaction mapping.

- Array or Functional query languages for analytical pipelines.

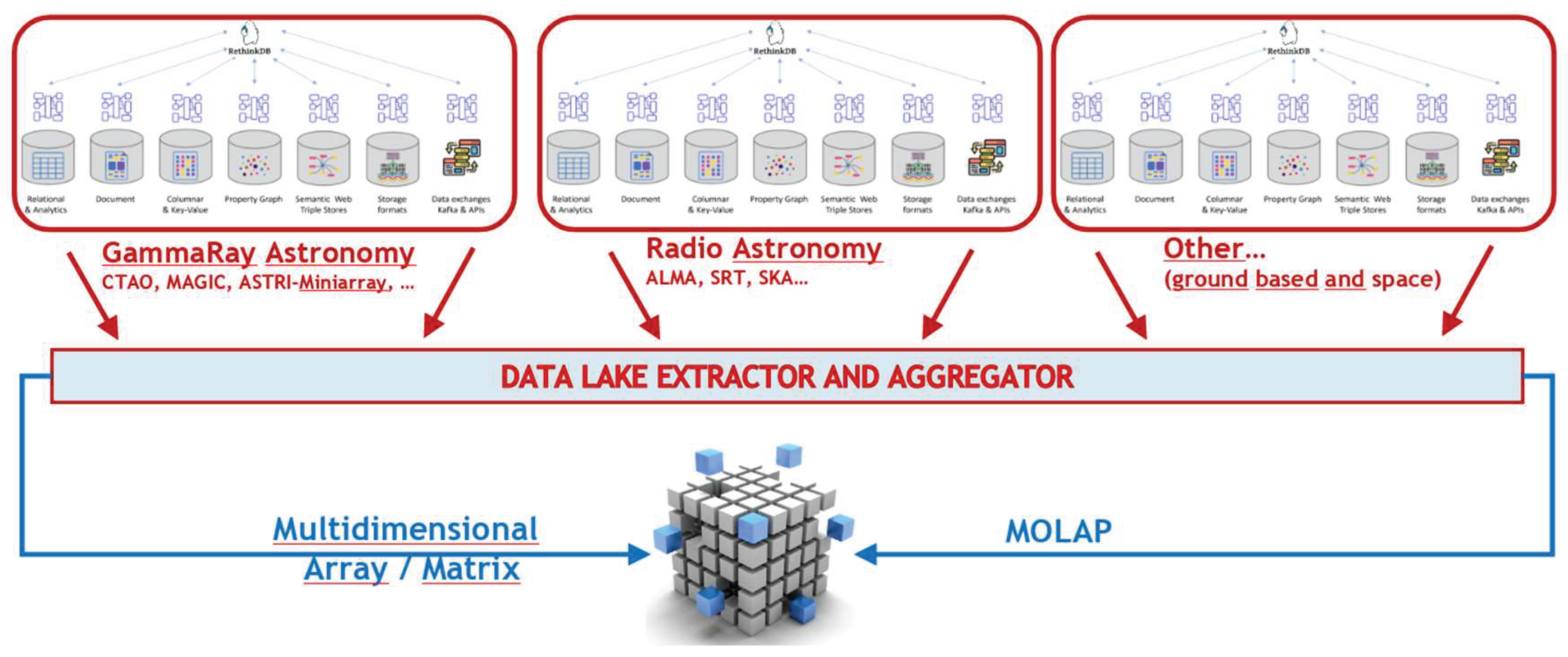

5. Polyglot Persistence in a Data Lake Scenario

- Relational databases for structured data.

- Object storage for unstructured or large datasets (e.g., images, videos, documents).

- NOSQL databases for semi-structured data that doesn't fit into a rigid schema.

- Graph databases for analyzing complex relationships and social semantic analytics.

- Structured Proposal Data can be easily managed by a Relational DBMS (e.g., MariaDB, PostgreSQL)

- Logs and Alarms require high-throughput so a key-value stores (e.g., Voldemort) can well fit.

- JSON-based Scientific Metadata can rely on a Document-oriented DBs (e.g., MongoDB)

- Streaming Telemetry and Event Data may need a Column-family databases (e.g., Cassandra) approach

- Tracking Accesses and Users Interactions could be managed by a Graph databases (e.g., Neo4j, Azure Cosmos DB)

- Data Analytics/Pipelines can be easily stored by an Array or functional query systems approach

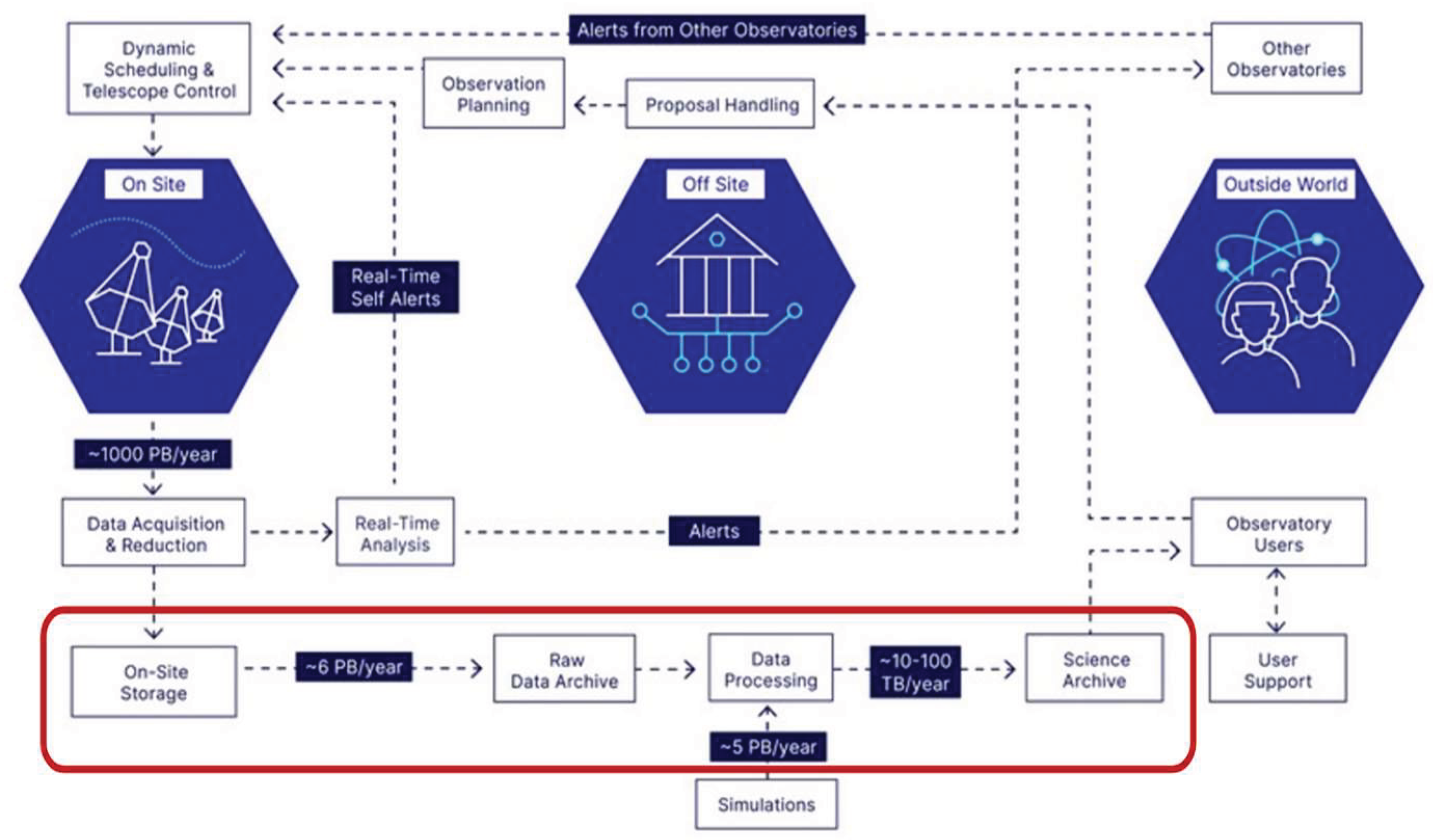

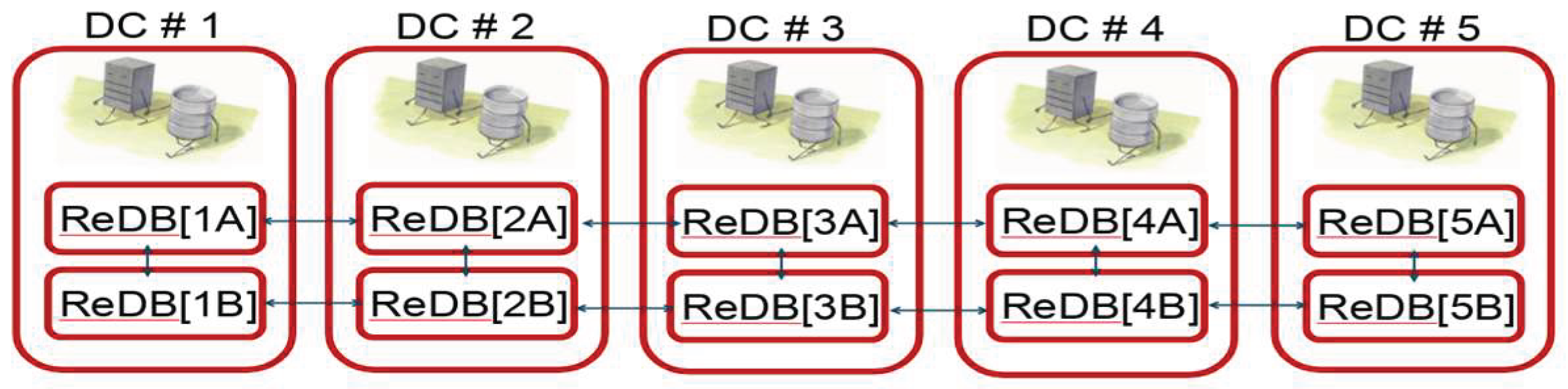

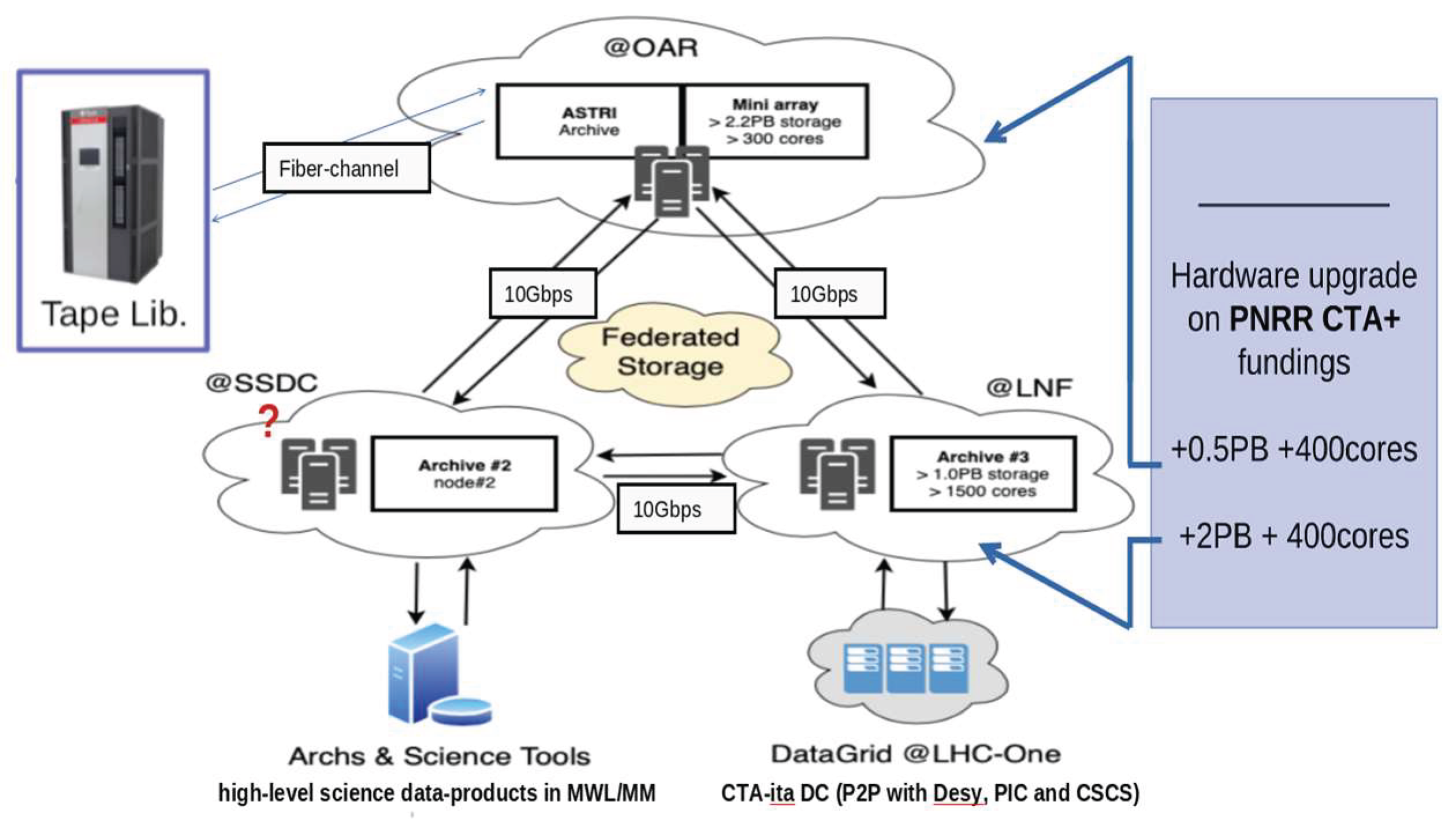

6. Distributed Strategy for a Petascale Astronomical Observatory

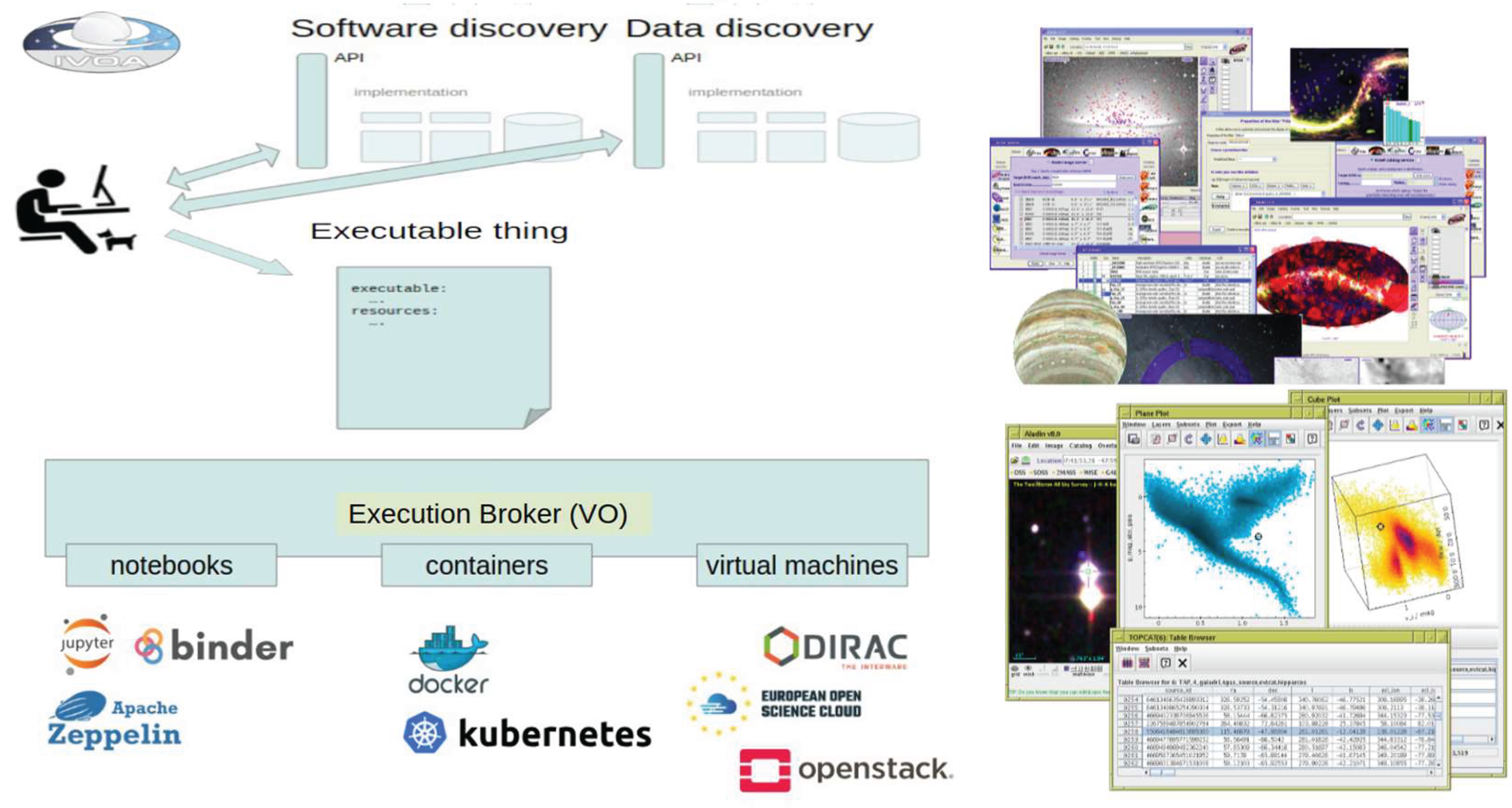

7. FAIR Principles and VO Integration in Polyglot Persistence

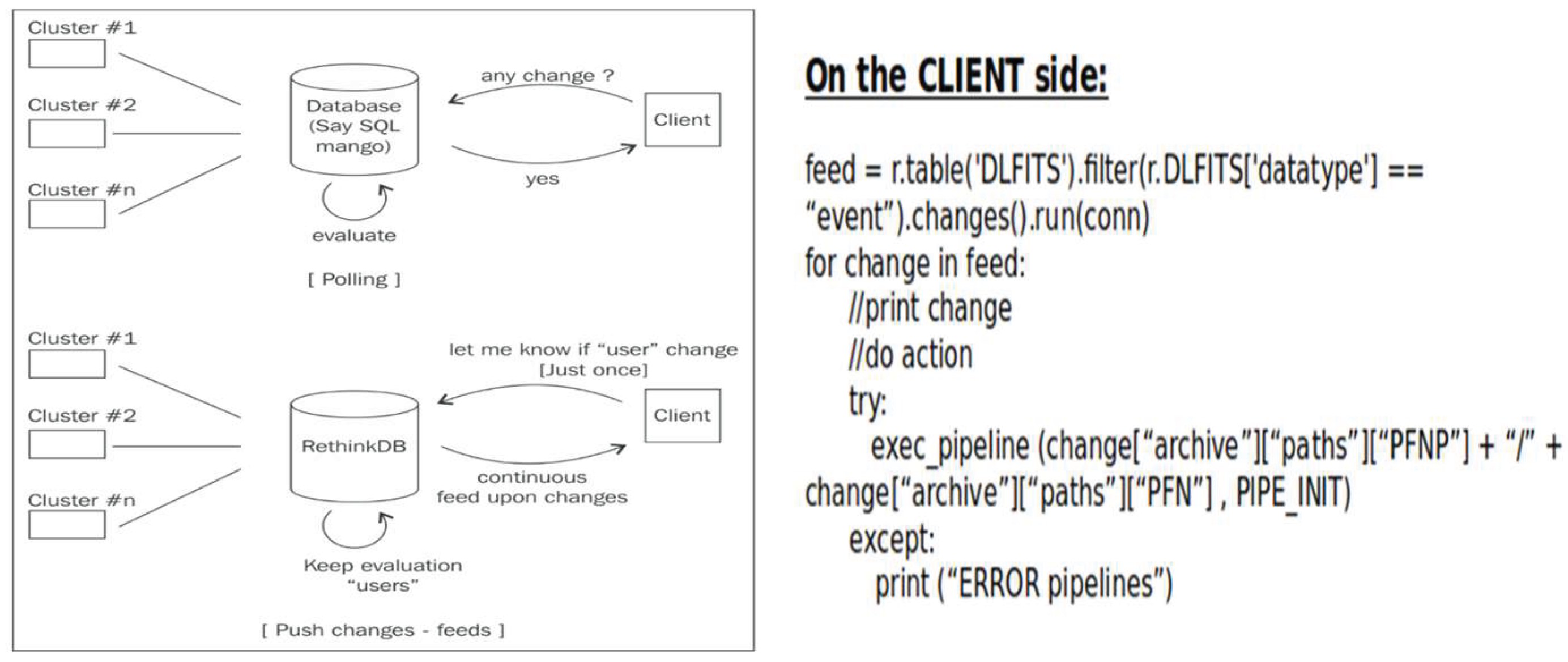

8. CTAARCHS Implementation

8.1. Modular Design and Data Transfer Workflow

- Command-Line Interface (CLI): Executable Python scripts with standardized input/output.

- Python Library: Core actions encapsulated in run_action() functions, enabling seamless integration into external applications.

- REST API: Web-based access via HTTP methods (POST, GET, PUT/PATCH, DELETE), allowing CRUD operations through scripts or clients (e.g., CURL, Requests).

- Containerized Deployment: Distributed as a Docker container (AMASLIB_IO) to ensure platform compatibility and ease of deployment in Kubernetes (K8s) environments.

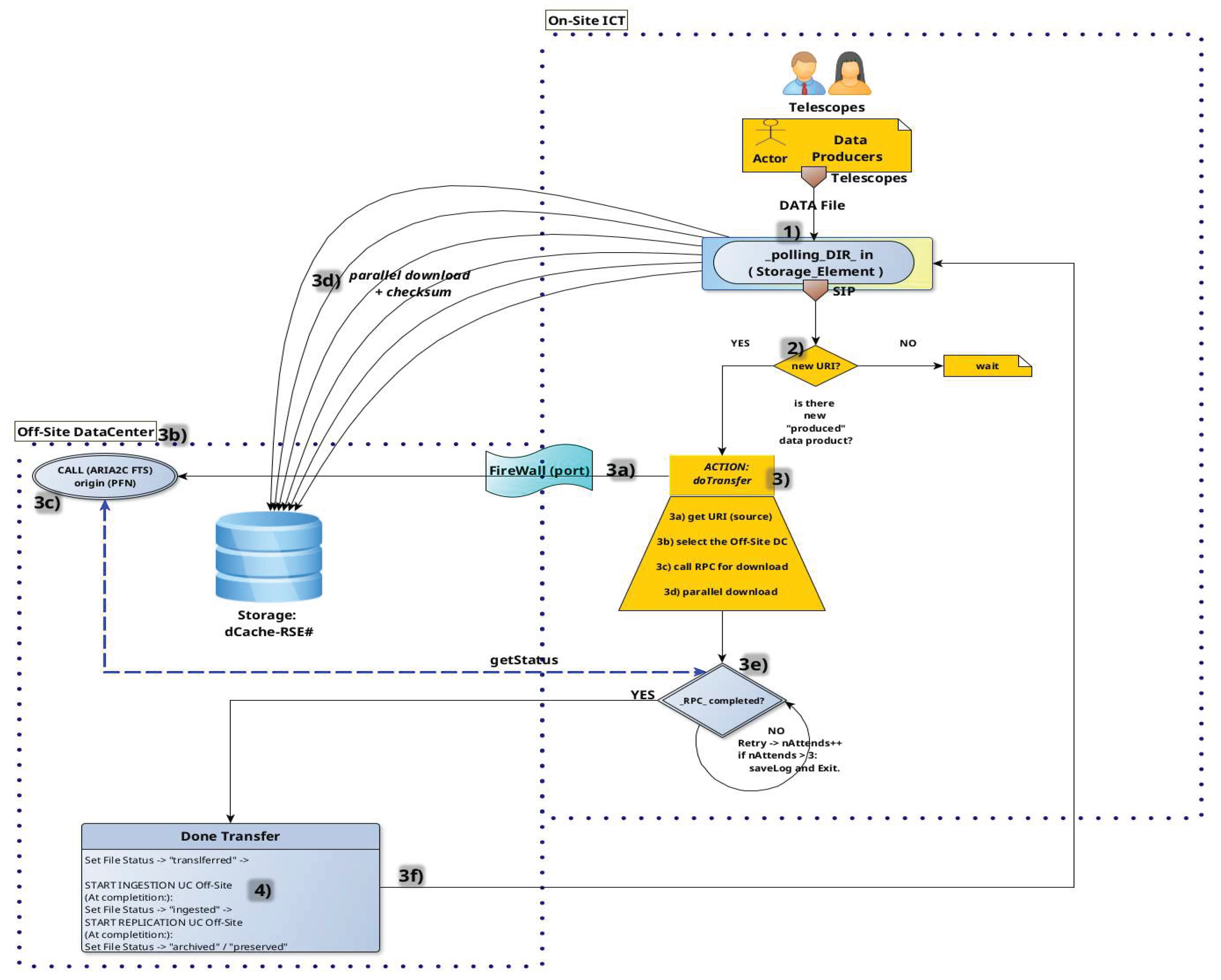

8.2. On-Site-Off-Site Data Transfer System

8.2.1. Prerequisites

- A.

- Remote Access to On-Site Storage: On-site storage must be remotely accessible via secure, standardized protocols (e.g., HTTPS or XRootD), with appropriate ports opened between datacenters. This can be achieved through object storage systems or secure web-accessible file directories.

- B.

- File Monitoring and Triggering: On-site storage must monitor a designated _new_data/ directory to detect new files and trigger transfer actions. A lightweight Python watchdog script can monitor for symbolic links—created upon file completion—and initiate transfer, then remove or relocate the link upon success.

- C.

- Off-Site Download Mechanism: Off-site datacenters must run an RPC service hosting the Aria2c downloader. Aria2c supports high-throughput parallel downloads, chunking, resume capability, and integrity verification via checksums. A web UI provides real-time monitoring and automatic retries.

8.2.2. Typical Workflow

- 1)

- Data Generation: Telescope systems write data to local storage; upon completion, a symbolic link is placed in _totransfer/.

- 2)

- Trigger Detection: A local Python client monitors the directory and detects new links.

- 3)

- Transfer Initialization:

- a)

- The symbolic link is resolved to a URI.

- b)

- The target off-site datacenter is selected based on policy rules (e.g., time-based, data level, or project ID).

- c)

- The client invokes an RPC command to the off-site Aria2c service, initiating parallel downloads.

- d)

- Transfer progress is tracked, and completion is confirmed via RPC status queries.

- e)

- Upon success, the symbolic link is removed.

- 4)

- Post-Transfer Actions: Additional use cases, such as replication or data ingestion, can be triggered automatically on the off-site side.

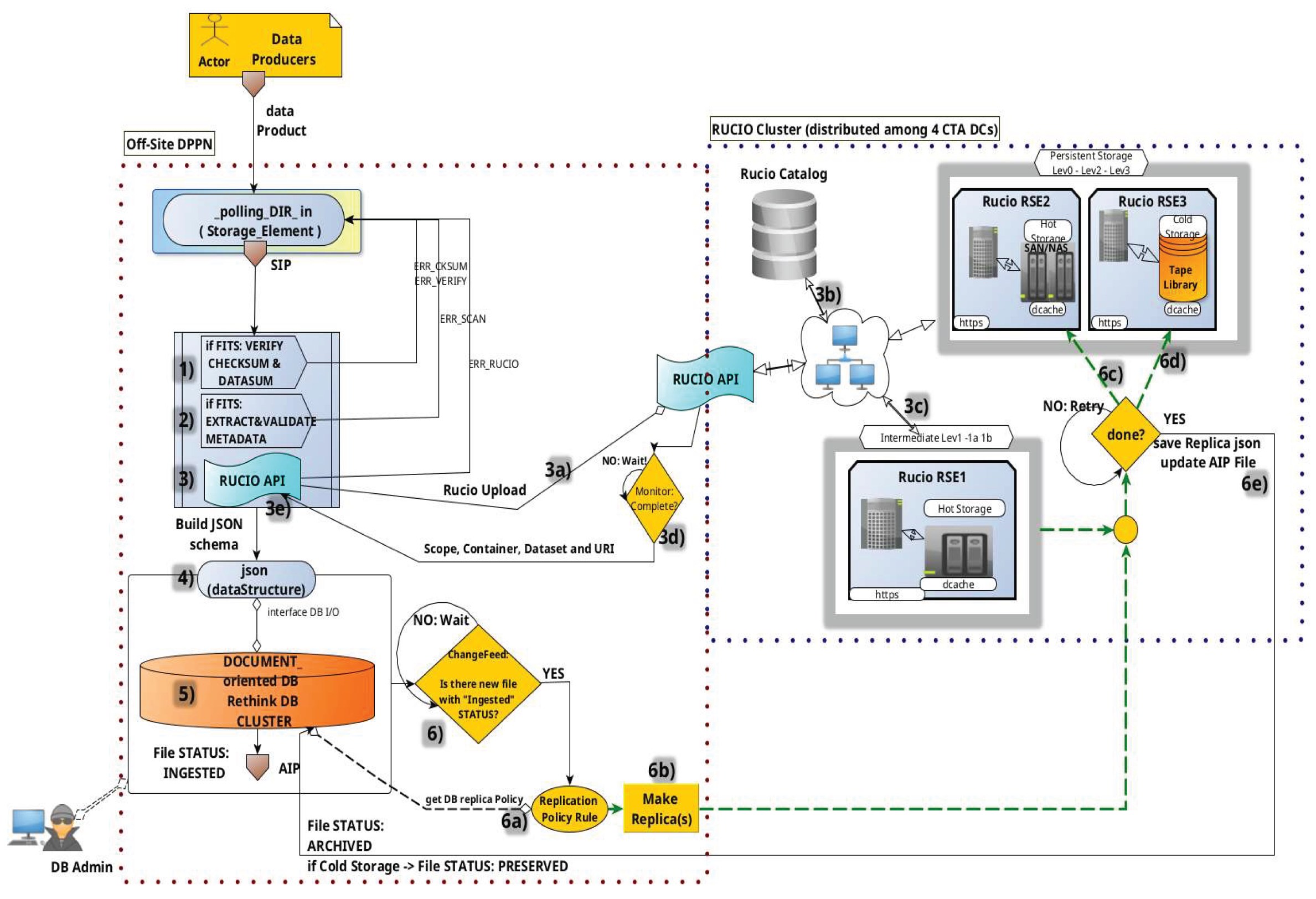

8.3. Dataset Ingestion

8.3.1. Prerequisites

- A.

- The _toingest/ storage-pool directory must be POSIX-accessible, even if hosted on object storage.

- B.

- Python environment must include fitsio (or astropy), json, rucio, and rethinkdb libraries.

- C.

- The external storage endpoints called Remote Storage Elements (RSEs) must be accessible via standard A&A protocols (e.g., IAM tokens or legacy credentials).

- D.

- A write-enabled RethinkDB node must be reachable on the local network.

8.3.2. Typical Workflow

- 1)

- Data Staging: Data products from Data Producers (pipelines, simulations, or DTS) are placed in _toingest/.

- 2)

- SIP Creation: A Software Information Package (SIP) is generated, including checksums to verify file integrity.

- 3)

- Metadata Validation: FITS headers are parsed and validated to ensure required metadata fields are present, correctly typed, and semantically consistent.

- 4)

- 1 Storage Upload:

- a)

- Files are uploaded to an Object Storage path (e.g., dCache FS) using RUCIO or equivalent tools.

- b)

- If already present on the storage, only a move to a final archive path is needed.

- c)

- Upload status is monitored; once confirmed, metadata (e.g., scope, dataset, RSE) is added to a corresponding JSON record.

- 5)

- Database Registration: Finalized JSON is ingested into the RethinkDB archive, changing file status to "ingested" and completing the Archive Information Package (AIP) creation.

- 6)

- Trigger Replication: Upon new entry detection (via RethinkDB’s changefeed), the MAKE_REPLICA process is automatically launched.

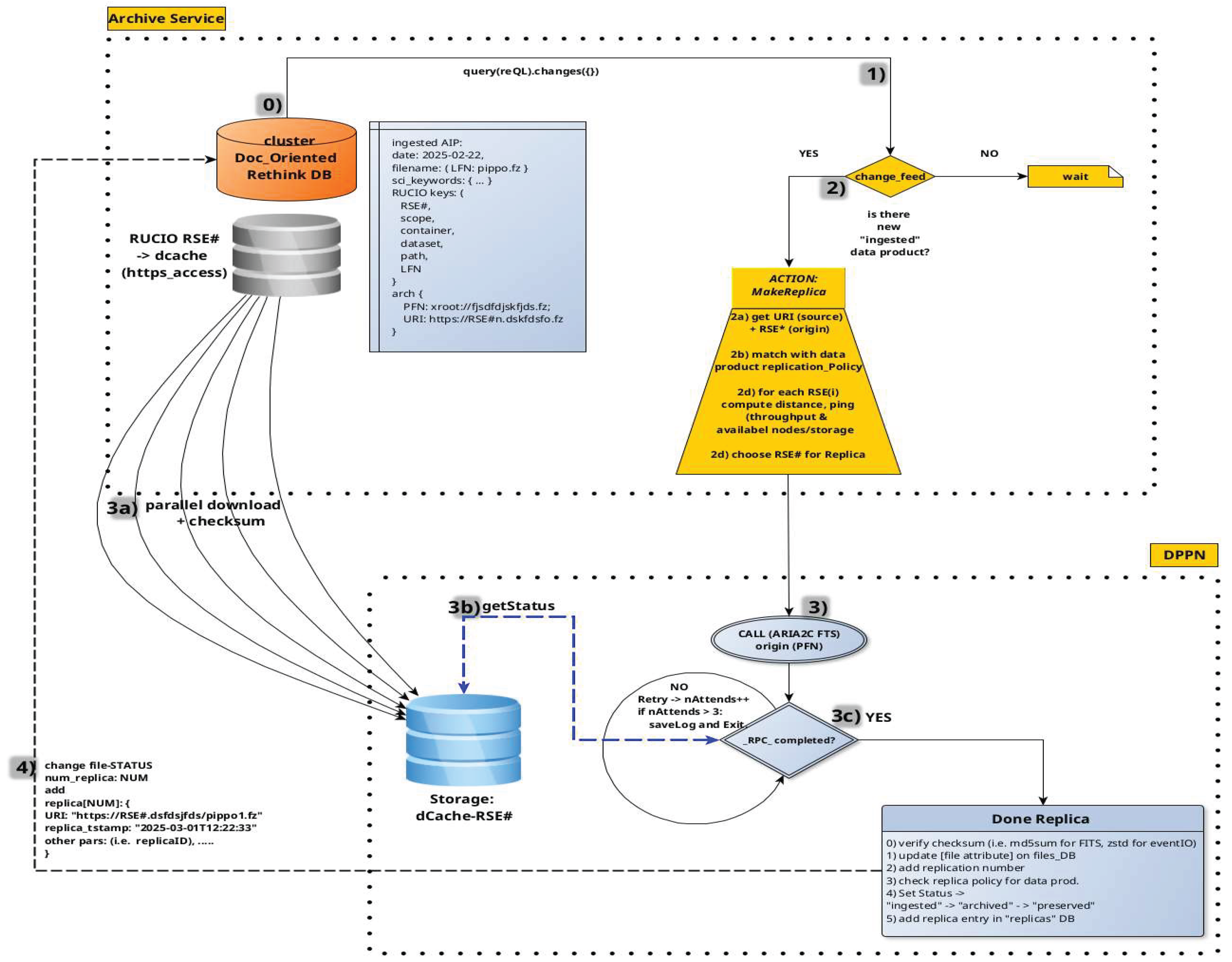

8.4. Replica Management in CTAARCHS: Automation and Policy Enforcement

8.4.1. Replication Status Levels

- Ingested: One off-site catalog record exists.

- Archived: At least one replica stored across another RSE.

- Preserved: Includes a backup on cold storage.

8.4.2. Prerequisites

- A.

- All target RSEs must be reachable over secure protocols (e.g., HTTPS, xrootd), and relevant ports must be open across data centers.

- B.

- The ReThinkDB cluster must support read/write access from local clients.

- C.

- Each off-site RSE must run an ARIA2c RPC daemon for parallel downloads and transfer monitoring.

8.4.3. Typical Workflow

- 1)

- Ingestion completion updates the file catalog, triggering the replication process via the changefeed.

- 2)

- The client fetches the file’s URI (2a), matches it against the replication policy (2b), and evaluates eligible RSEs based on latency, throughput, and availability (2c).

- 3)

- It initiates parallel data transfers using ARIA2c RPC (3a) and monitors each transfer (3c).

- 4)

- On success, the checksum is verified, a new replica record is added to the file’s JSON metadata, and the replica count is updated.

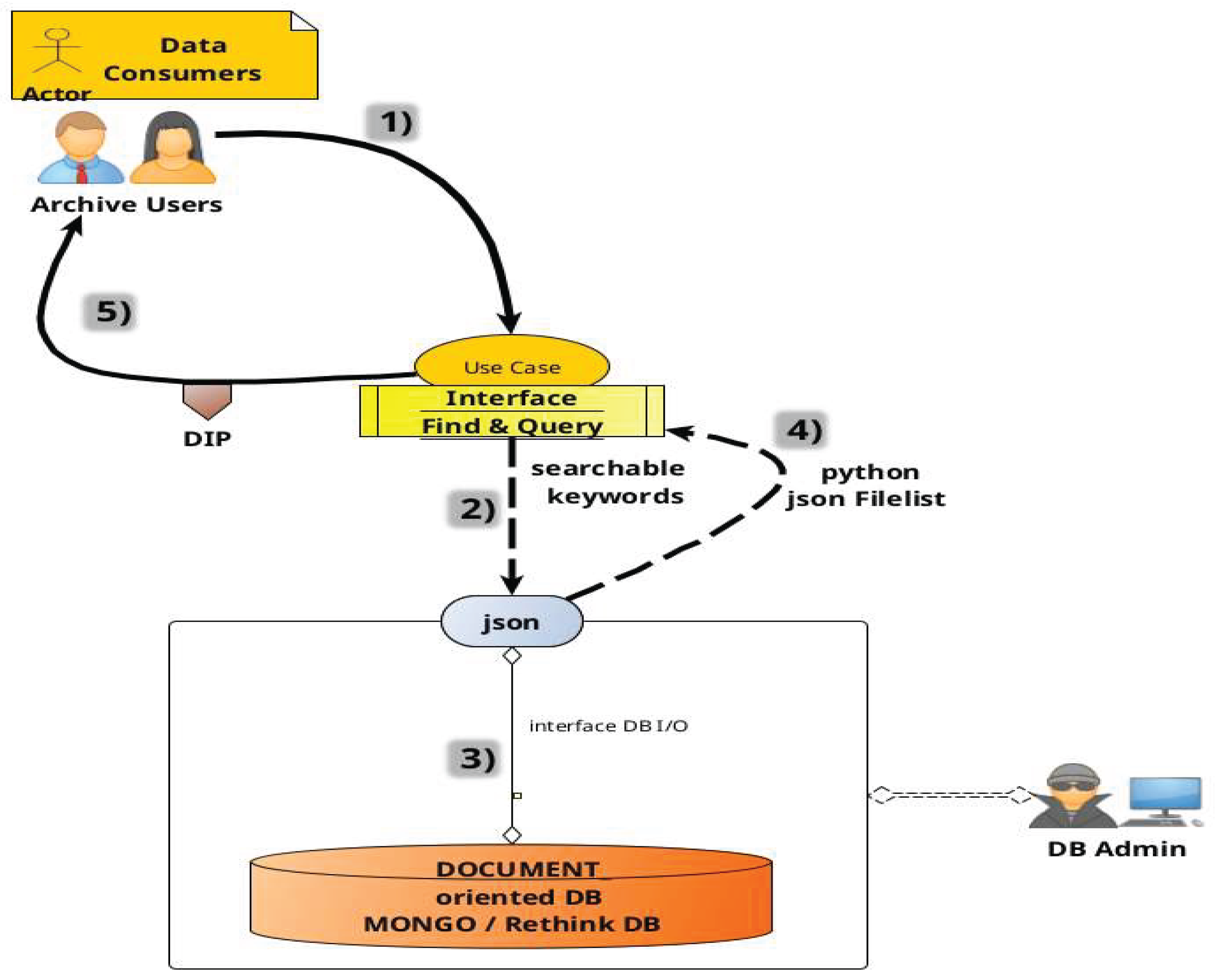

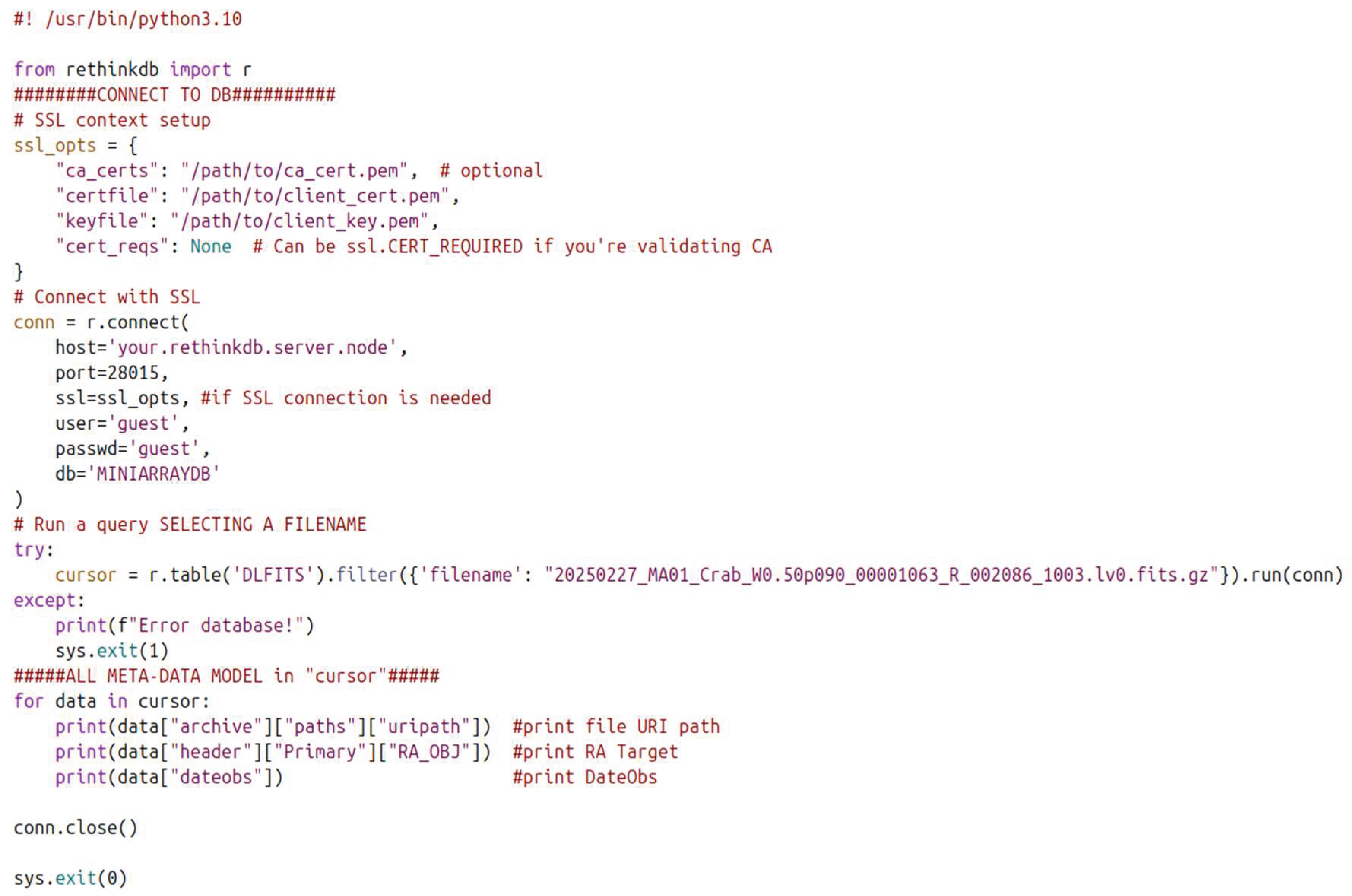

8.5. Dataset Search

8.5.1. Prerequisite

- A.

- Read-only access to the ReThinkDB cluster must be available from at least one node in the local network.

8.5.2. Typical Workflow

- 1)

- A user submits a query via the archive interface, specifying metadata fields of interest.

- 2)

- The interface maps the request to searchable metadata intervals.

- 3)

- It then queries the ReThinkDB cluster through a local node.

- 4)

- The database returns a list of matching data products in JSON format, including URIs and identifiers.

- 5)

- This list is delivered to the user for potential retrieval.

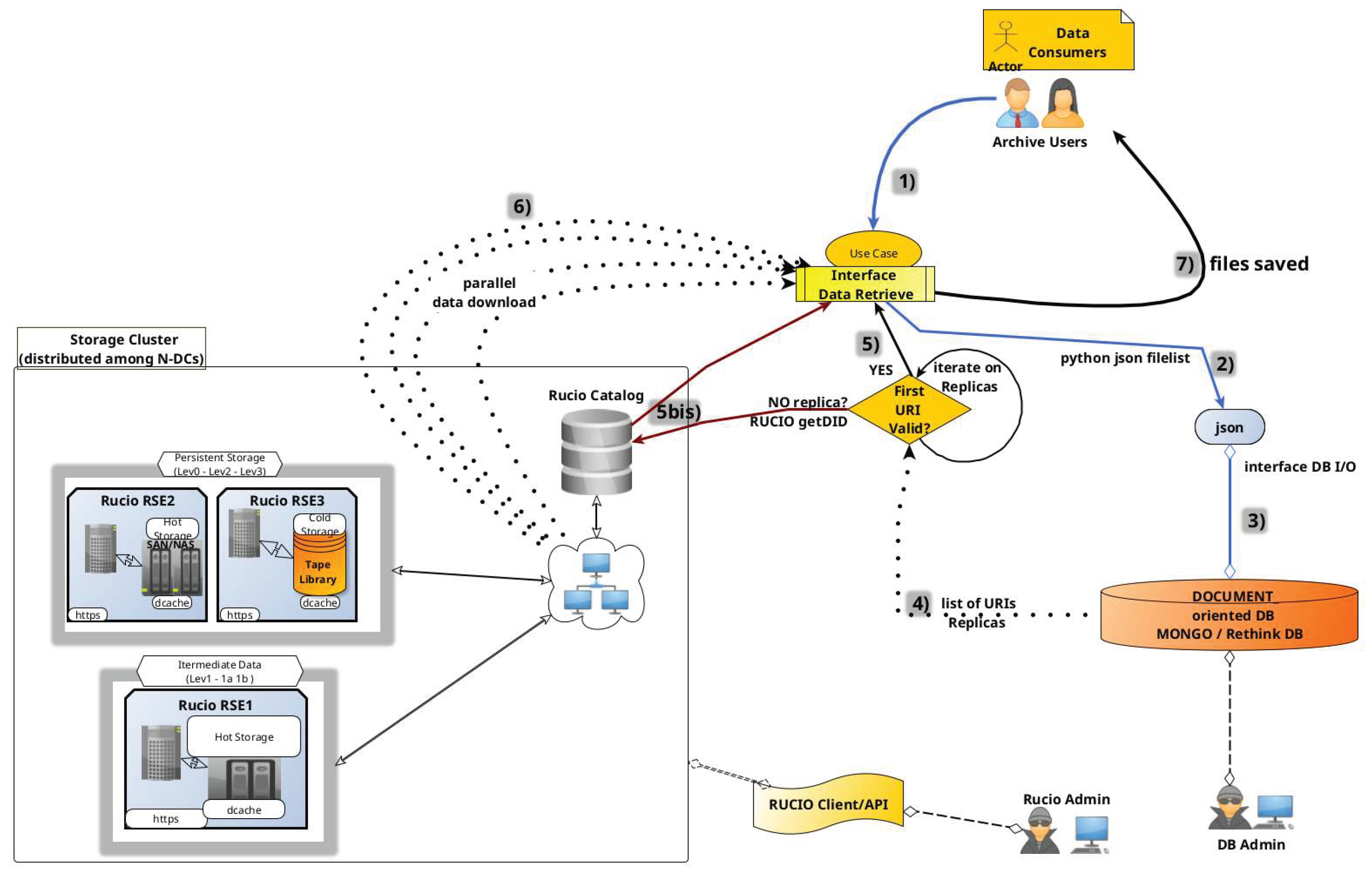

8.6. Dataset Retrieval

8.6.1. Prerequisites

- A.

- Remote Storage elements (RSEs) must be accessible across data centers via secure protocols (e.g., HTTPS, XRootD), with required ports open. Resources may be object storage pools or directories exposed via HTTPS with encryption and authentication.

- B.

- The RethinkDB cluster must be accessible in read-write mode from at least one node within the local network.

8.6.2. Typical Workflow

- 1)

- A Data Consumer provides a JSON list of requested data products to the retrieval interface.

- 2)

- The system queries the local RethinkDB node

- 3)

- The database returns a list of replica URIs for each product

- 4)

- The interface verifies the existence of each replica

- 5)

- Valid URIs are downloaded in parallel

- 6)

- The parallel download starts for any available URI

- 7)

- Retrieved files are stored in a user-specified local or remote directory.

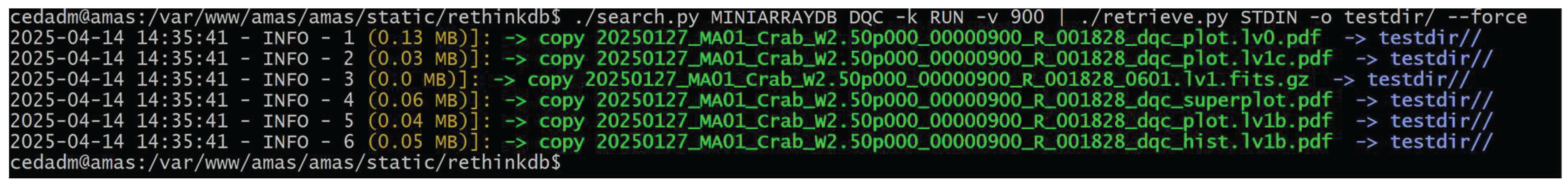

8.7. Search and Retrieve Integration/Concatenation

LIST=$(curl "https://amas-rest/search?key=DATE&val=2025-01-15:2025-02-26&key=RUN&val=846:895&key=FILE&val=20250120_MA01_OffFixed")

echo $LIST

{

"files": [

"https://amas.oa-roma.inaf.it/static/data/Miniarray/.../20250120_MA01_OffFixed-60-015_Fixed_00000849_I_001761_1001.lv0.fits.gz",

"... more URIs ..."],

"nfiles": 9

}

- Cost(i): Estimated retrieval cost from site i

- Latency(i): Time to initiate transfer

- FileSize: Total size of the file

- Throughput(i): Nominal data rate

- Workload(i): Current system load (0 = idle, 1 = saturated)

- Distance(i): Network or geographic distance

if latency > threshold or throughput < expected * 0.5:

Workload_i = 0.8 # heavy

elif throughput < expected * 0.8:

Workload_i = 0.5 # moderate

else:

Workload_i = 0.1 # low

docker load -i amas-api_1.0.2.tar;

docker run -it amas-environment bash;

./venv/bin/python ./search.py

8.8. Monitor Integrity, Reports and Alarms

9. Deployment of CTAARCHS at CIDC and AMAS

9.1. Hardware Resources

- INAF – OAR, Astronomical Observatory of Rome

- INAF – SSDC, ASI Science Data Center

- INFN – LNF, National Laboratoies of Frascati

9.2. The Setup

9.3. Users Interfaces

- Pipeline/Simul (for low level data products)

- Science User (for higher level data products)

- BDMS-user and admin (for high level operation on archives)

9.4. Pipeline / Simulation Users Access and Interface

9.5. Unconventionl Challenges

9.6. Database and DataModel Interfaces

r.table("DLFITS").index_create("dateobs").run(conn) #CREATE INDEX

r.table("DLFITS").index_wait("dateobs").run(conn) #WAIT COMPLETITION

# Query using the index

r.table("DLFITS").get_all("2024-12-06", index="dateobs").run(conn)

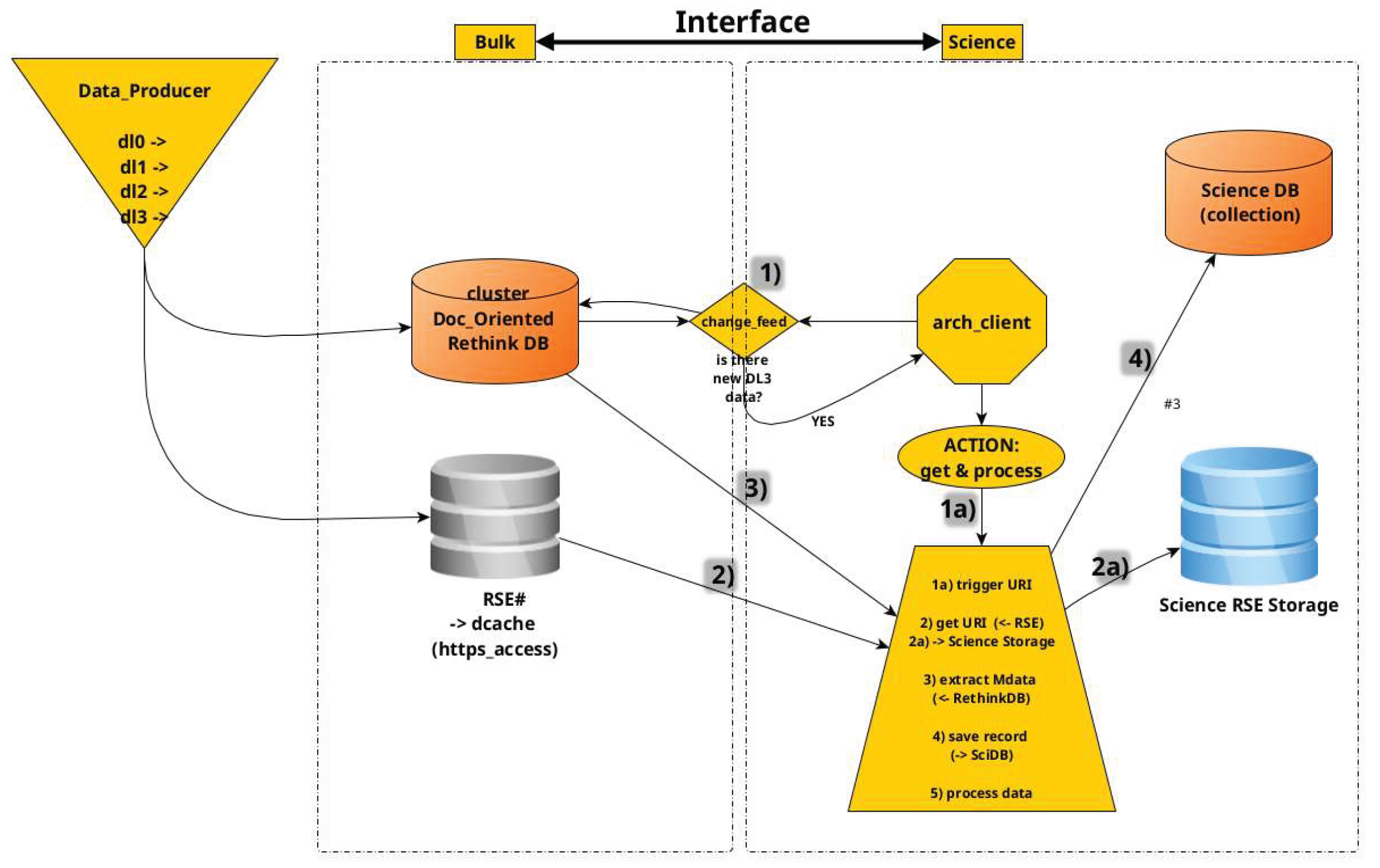

9.7. Web Archive Portal for the End-user and Other Interfaces

9.7.1. Prerequisites

- A.

- Python environment must include fitsio (via Astropy), json, rethinkdb, and rucio libraries.

- B.

- Bulk and Science RSEs must be accessible via supported authentication methods: IAM tokens (preferred), legacy grid certificates (deprecated), or credentials.

- C.

- The ReThinkDB cluster must be accessible in read-only mode via at least one local node.

- D.

- The Science Database may reside within ReThinkDB or any compatible RDBMS.

9.7.2. Typical Workflow

- 1)

- Detection of new DL3 entries triggers the get&process action.

- 2)

- The associated URI is fetched from the source RSE and transferred to the Science RSE.

- 3)

- DL3 metadata are extracted from ReThinkDB and written to the Science DB.

- 4)

- Optional automated workflows convert DL3 to DL4 and DL5 products.

10. Conclusions and Recommendations

10.1. Software Resources & Repositories

10.2. CTAARCH & AMAS

- − Homepage: https://amas.oa-roma.inaf.it

- − Docker API: https://www.ict.inaf.it/gitlab/AMAS/dockerAPI/

- − REST-API: https://amas-rest.oa-roma.inaf.it

10.3. RethinkDB

- − Homepage: https://rethinkdb.com

10.4. Minio

- − Homepage: https://min.io/

10.5. Airflow

- − Homepage: https://airflow.apache.org/

- − Homepage: https://htcondor.org/

- − Repo: https://github.com/htcondor

- − Homepage: https://onedata.org/#/home

10.6. Rucio

- − Homepage: https://rucio.cern.ch/

- − Repo: https://github.com/rucio/rucio

10.7. Django

- − Homepage: https://www.djangoproject.com/

- − Repo: https://github.com/django/django

- − REST-API: https://www.django-rest-framework.org/

- − Homepage: https://panda-wms.readthedocs.io/en/latest/

- − Repo: https://github.com/PanDAWMS

10.8. Dirac

- − Repo: https://github.com/DIRACGrid

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Acronyms and Abbreviations

| ACID | Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation and Durability |

| AMAS | ASTRI and Miniarray Archive System |

| ASTRI | Astrofisica con Specchi a Tecnologia Replicante Italiana |

| CAP | Theorem: Consistency (data Consistency), Availability (data Accessibility) and Partitioning (partition Tollerance) |

| CLI | Command Line Interface |

| CTAARCHS | Cloud-Based Technology for Archiving Astronomical Reseach Contents & Handling System |

| CTAO | Cherenkov Telescope Array Observatory |

| DBMS | DataBase Management System |

| DPAR | Data Product Acceptable Requirements |

| DPPN | Datacenters, like DC |

| FAIR | Findable, Accessible, Shared and Reusable |

| IKC | In-Kind Contribution |

| MWL | Multi WaveLenght |

| NOSQL | Not Only SQL |

| RDBMS | Relational DBMS |

| REST API | REpresentional State Transfer Application Programming Interface |

| RSE | Remote Storage Element |

| SQL | Structured Query Language |

| WMS | Workload Management System |

Appendix

Data Model Example (DL0 Fits-Data)

{

"aaid": "17447020150367122",

"aipvers": "AMAS_1.0.0",

"archive": {

"PFN": "20250227_MA01_Crab_W0.50p090_00001063_R_002086_1003.lv0.fits.gz",

"PFNP": "/archive/MINIARRAY/PHYSICAL/pass_0.0.1/20250227/00001063/dl0/varlg/v2",

"archdate": "2025-04-15 07:26:55.036728",

"archtime": 1744702015,

"checksum": "3ac92bdc",

"container": "20250415",

"dataset": "fits-data",

"filesize": 14747749,

"paths": {

"RSE": "astriFS",

"replicaflag": 0,

"type": "web-https",

"uid": "17447020150367122",

"uripath": "https://amas.oa-roma.inaf.it/static/data/Miniarray/pass_0.0.1/20250227/00001063/dl0/varlg/v2/20250227_MA01_Crab_W0.50p090_00001063_R_002086_1003.lv0.fits.gz"

},

"replicas": {

"replica": [

{

"number": "0",

"rdata": "2025-04-15 07:26:55.036728",

"rid": "17447020150367122",

"rtype": "web-https",

"spool": "AMAS",

"uri": "https://amas.oa-roma.inaf.it/static/data/Miniarray/pass_0.0.1/20250227/00001063/dl0/varlg/v2/20250227_MA01_Crab_W0.50p090_00001063_R_002086_1003.lv0.fits.gz"

}

]

},

"scope": "MA01"

},

"author": "Stefano Gallozzi",

"camera": "{'name': 'ASTRIMA', 'origin': 'ASTRIDPS', 'creator': 'adas preprocessing v1.1', 'npdm': 37, 'modeid': 'R', 'datatype': 'fits-data'}",

"daqmode": "R",

"datadesc": "lv0_var_lg",

"datatype": "1003",

"dateobs": "2025-02-27",

"event": {

"obsdate": "2025-02-27"

},

"file_version": 1,

"filename": "20250227_MA01_Crab_W0.50p090_00001063_R_002086_1003.lv0.fits.gz",

"fsize": 14747749,

"header": {

"Primary": {

"ALT_PNT": -999,

"AZ_PNT": -999,

"BITPIX": 16,

"CHECKSUM": "g5XEj3XBg3XBg3XB",

"COMMENT": [

"= 'FITS (Flexible Image Transport System) format is defined in ''Astron'"

],

"CREATOR": "adas preprocessing v1.1.1",

"DAQ_ID": "002086",

"DAQ_MODE": "R",

"DATAFORMAT": "v1.0",

"DATALEVEL": "lv0",

"DATAMODE": "10",

"DATASUM": "0",

"DATE": "2025-02-28T07:34:30",

"DATE-END": "2025-02-27T21:10:49",

"DATE-OBS": "2025-02-27T20:29:41",

"DEC_OBJ": 22.0174,

"DEC_PNT": 21.517,

"EQUINOX": "2000.0",

"EXTEND": true,

"FILENAME": "20250227_MA01_Crab_W0.50p090_00001063_R_002086_1003.lv0.fits",

"FILEVERS": 1,

"INSTRUME": "CAMERA",

"MJDREFF": 0.00080074,

"MJDREFI": 58849,

"NAXIS": 0,

"NTEL": 1,

"OBJECT": "Crab",

"OBS_DATE": "20250227",

"OBS_MODE": "W0.50p090",

"ORIGIN": "ASTRIDPS",

"ORIG_ID": "00",

"PROG_ID": "001",

"RADECSYS": "FK5",

"RA_OBJ": 83.6324,

"RA_PNT": 83.632,

"RUN_ID": "00001063",

"SBL_ID": "002",

"SIMPLE": true,

"SUBMODE": "02",

"TELAPSE": "2468",

"TELESCOP": "ASTRI-MA",

"TEL_ID": "01",

"TIMEOFFS": 0,

"TIMESYS": "TT",

"TIMEUNIT": "s",

"TSTART": "162851381",

"TSTOP": "162853849"

}

},

"id": "f9c92d8e-e2a8-4c8b-bba9-7d6209317676",

"infomail": "stefano.gallozzi@inaf.it",

"latest_version": 1,

"object": "Crab",

"obsid": 2086,

"obsmode": "W0.50p090",

"packtype": "fits-data",

"programid": 111,

"proposal": {

"carryover": "Y",

"category": "EXT/RP",

"cycle": {

"name": "cycle2024/1",

"period": "[ 2023-05-01,2023-05-05 ]",

"type": "semester"

},

"obsprog": {

"arrayconf": {

"acq_mode": "wobble",

"acq_submode": "2.5",

"telmatrix": {

"confname": "fulla_ma",

"on_off": "[ 1,0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0 ]",

"type": "array"

},

"trigger": "S2"

},

"constraints": {

"maxMIF": "0.7",

"maxZA": "60.0 [deg]",

"minAT": "0.7",

"minET": "100 [hrs]",

"minMD": "100 [deg]",

"minZA": "0.0 [deg]"

},

"progid": "1",

"target": {

"coord": "[ 83.6329, 22.014 ]",

"dec": 22.014,

"diameter": "7.0 [arsec]",

"epoch": "J2000",

"magnitude": "8.4 [ABmag]",

"name": "Crab_Nebula",

"rad": 83.6329,

"tooflag": "0",

"type": "wcs"

}

},

"piname": "Giovanni Pareschi",

"propdate": "2023-11-21",

"propid": "2",

"proplink": "https://amas.oa-roma.inaf.it/proposals/2/",

"proptype": "SCI",

"reqtime": "300 [hrs]"

},

"runid": 1063,

"schema": "https://amas.oa-roma.inaf.it/static/aipMADLFITSschema",

"schemavers": "FITS_v0.0.1",

"telescope": {

"altitude": "2390 [m]",

"diamS1": "4.6 [m]",

"diamS2": "1.5 [m]",

"geo": {

"coord": [

28.30015,

-16.50965

],

"type": "gps"

},

"optconf": "DM",

"telid": "01",

"telname": "MA01",

"type": "AIC"

},

"timestamp": "2025-02-28 09:31:54+00:00"

}

{

"$schema": "https://json-schema.org/draft/2020-12/schema",

"title": "Archive Object Schema",

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"archive": {

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"PFN": { "type": "string" },

"PFNP": { "type": "string" },

"archdate": { "type": "string", "format": "date-time" },

"archtime": { "type": "integer" },

"checksum": { "type": "string" },

"container": { "type": "string" },

"dataset": { "type": "string" },

"filesize": { "type": "integer" },

"paths": {

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"RSE": { "type": "string" },

"replicaflag": { "type": "integer" },

"type": { "type": "string" },

"uid": { "type": "string" },

"uripath": { "type": "string", "format": "uri" }

},

"required": ["RSE", "replicaflag", "type", "uid", "uripath"]

},

"replicas": {

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"replica": {

"type": "array",

"items": {

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"number": { "type": "string" },

"rdata": { "type": "string", "format": "date-time" },

"rid": { "type": "string" },

"rtype": { "type": "string" },

"spool": { "type": "string" },

"uri": { "type": "string", "format": "uri" }

},

"required": ["number", "rdata", "rid", "rtype", "spool", "uri"]

}

}

},

"required": ["replica"]

},

"scope": { "type": "string" }

},

"required": [

"PFN", "PFNP", "archdate", "archtime", "checksum", "container",

"dataset", "filesize", "paths", "replicas", "scope"

]

}

},

"required": ["archive"]

}

"archive": {

"PFN": "20250227_MA01_Crab_W0.50p090_00001063_R_002086_1003.lv0.fits.gz",

"PFNP": "/archive/MINIARRAY/PHYSICAL/pass_0.0.1/20250227/00001063/dl0/varlg/v2",

"archdate": "2025-04-15 07:26:55.036728",

"archtime": 1744702015,

"checksum": "3ac92bdc",

"container": "20250415",

"dataset": "fits-data",

"filesize": 14747749,

"paths": {

"RSE": "astriFS",

"replicaflag": 0,

"type": "web-https",

"uid": "17447020150367122",

"uripath": "https://amas.oa-roma.inaf.it/static/data/Miniarray/pass_0.0.1/20250227/00001063/dl0/varlg/v2/20250227_MA01_Crab_W0.50p090_00001063_R_002086_1003.lv0.fits.gz"

},

"replicas": {

"replica": [

{

"number": "0",

"rdata": "2025-04-15 07:26:55.036728",

"rid": "17447020150367122",

"rtype": "web-https",

"spool": "AMAS",

"uri": "https://amas.oa-roma.inaf.it/static/data/Miniarray/pass_0.0.1/20250227/00001063/dl0/varlg/v2/20250227_MA01_Crab_W0.50p090_00001063_R_002086_1003.lv0.fits.gz"

}

]

},

"scope": "MA01"

},References

- Giaretta, D. (2011). Introduction to OAIS Concepts and Terminology. Advanced Digital Preservation. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- O.J. Akindote, O.J., Adegbite, A.O, Dawodu, S.O., Omotosho, A., Anyanwu, A. (2023.). Innovation in Data Storage Technologies: from Cloud Computing to Edge Computing, Computer Science & IT Research Journal P-ISSN: 2709-0043, E-ISSN: 2709-0051 Volume 4, Issue 3, P.273-299, December 2023. [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, K., Sharma, B., & Singh, R. (2022). Implementation analysis of IoT-based offloading frameworks on cloud/edge computing for sensor generated big data. Complex & Intelligent Systems, 8(5), 3641-3658. [CrossRef]

- Bhargavi, P., & Jyothi, S. (2020). Object detection in Fog computing using machine learning algorithms. In Architecture and Security Issues in Fog Computing Applications (pp. 90-107). IGI Global. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S., & Rodero, I. (2017). Understanding behavior trends of big data frameworks in ongoing software-defined cyber-infrastructure. In Proceedings of the Fourth IEEE/ACM International Conference on Big Data Computing, Applications and Technologies (pp. 199-208). [CrossRef]

- Gąbka, J. (2019). Edge computing technologies as a crucial factor of successful industry 4.0 growth. The case of live video data streaming. In Advances in Manufacturing II: Volume 1-Solutions for Industry 4.0 (pp. 25-37). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D., Singh, R.K., Mishra, R., & Vlachos, I. (2023). Big data analytics in supply chain decarbonisation: a systematic literature review and future research directions. International Journal of Production Research, 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Lathar, P., Srinivasa, K.G., Kumar, A., & Siddiqui, N. (2018). Comparison study of different NoSQL and cloud paradigm for better data storage technology. Handbook of Research on Cloud and Fog Computing Infrastructures for Data Science, 312-343. [CrossRef]

- Manoranjini, J., & Anbuchelian, S. (2021). Data security and privacy-preserving in edge computing: cryptography and trust management systems. In Cases on Edge Computing and Analytics (pp. 188-202). IGI Global. [CrossRef]

- Padhy, R.P., & Patra, M.R. (2012). Evolution of cloud computing and enabling technologies. International Journal of Cloud Computing and Services Science, 1(4), 182. [CrossRef]

- Patel, S., & Patel, R. (2023). A comprehensive analysis of computing paradigms leading to fog computing: simulation tools, applications, and use cases. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 63(6), 1495-1516. [CrossRef]

- Shiau, W.L. (2015). An evolution, present, and future changes of cloud computing services. Journal of Electronic Science and Technology, 13(1), 54-59.

- Strohbach, M., Daubert, J., Ravkin, H., & Lischka, M. (2016). Big data storage. New Horizons for a Data-Driven Economy: A Roadmap for Usage and Exploitation of Big Data in Europe, 119-141. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Chen, B., Zhao, Y., Cheng, X., & Hu, F. (2018). Data security and privacy-preserving in edge computing paradigm: Survey and open issues. IEEE Access, 6, 18209-18237. [CrossRef]

- Svoboda T., Raček T., Handl J., Sabo J., Rošinec A., Opioła L., Jesionek W., Ešner M., Pernisová M., Valasevich N.M., Křenek A., Svobodová R., (2923) Onedata4Sci: Life science data management solution based on Onedata. [CrossRef]

- Gadban F.. (2021) Analyzing the Performance of the S3 Object Storage API for HPC Workloads. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 8540. [CrossRef]

- Malhotra S., Yashu F., Saqib N., Mehta D., Jangid J., Dixit S.. (2025) Evaluating Fault Tolerance and Scalability in Distributed File Systems: A Case Study of GFS, HDFS, and MinIO. [CrossRef]

|

|

Pros |

Cons |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Distributed Archive |

Centralized Archive | Distributed Archive | Centralized Archive | |

| Scalability | Easily scalable by adding nodes or storage across locations. | Simpler infrastructure for small-scale systems. | More complex to manage coordination between multiple nodes. | Harder and costlier to scale once capacity is reached. |

| Resilience & Redundancy | High availability; failure of one node doesn’t compromise access. | – | Requires sophisticated monitoring and synchronization tools. | Vulnerable to outages if no redundancy or failover is in place. |

| Performance & Speed | Improved access times via geographic proximity; enables load balancing. | Fast access for users close to the central server. | Latency may increase if not optimized for global access. | Performance can degrade under heavy load or traffic congestion. |

| Flexibility & Cost | Potentially cheaper to grow incrementally (e.g., via cloud or P2P). | More cost-effective for small/medium deployments. | Higher operational overhead for maintaining distributed nodes. | Expensive upgrades required as demands increase. |

| Fault Tolerance | Built-in disaster recovery ensures data integrity. | – | Ensuring data consistency across all nodes is challenging. | Greater risk of data loss if no proper backup or disaster plan exists. |

| Security | – | Easier to manage access and enforce security centrally. | Harder to enforce consistent security policies across locations. | Centralized point may be a larger attack surface if not properly secured. |

| Data Consistency | – | Strong consistency due to single control point. | Data may be temporarily inconsistent due to network delays or partitions. | – |

| Ease of Management | – | Easier setup, backup, and management from a single location. | More complexity in setup and maintenance. | – |

| Geographic Access | Efficient access from multiple locations. | – | Latency if nodes are not well-distributed or if networks are slow. | Slower access for users located far from the central server. |

| Definition |

Key Characteristics |

|

|---|---|---|

| Consistency | All nodes return the most recent write for any read request. | - Guarantees up-to-date data across the system - All parts of the system see updates immediately |

| Availability | Every request gets a response, even if some nodes are down. | - System remains responsive at all times - May not always return the latest data |

| Partition Tolerance | System continues to work despite network failures or communication breakdowns between nodes. | - Handles network partitions gracefully - Ensures continued operation despite node isolation or failure |

| Subtype / Model | Key Characteristics |

Use Cases |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Relational Databases (RDBMS) |

Traditional RDBMS |

• Structured schema (tables with rows and columns) • Uses SQL • Strong consistency with ACID (Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, Durability) properties |

Banking systems, ERP, CRM, enterprise apps |

|

NewSQL |

• Combines ACID consistency of RDBMS with horizontal scalability • Maintains SQL interface • Built for modern, high-scale applications |

High-performance apps requiring strong consistency (e.g., fintech, gaming) | |

|

OLAP/MOLAP |

• Optimized for analytical and BI queries • Pre-aggregated data cubes • High performance for historical data • Supports complex analytical calculations |

Business Intelligence (BI), data warehousing, reporting tools | |

| NoSQL Databases |

Key-Value Stores |

• Simple key-value pairs • Excellent read/write performance • Easy to scale horizontally • Flexible schema |

Caching, session data, real-time systems |

|

Column-Family Stores |

• Stores data by columns, not rows • Ideal for distributed large datasets • High availability and fault tolerance • Schema-less rows with flexible structure |

Analytics, time-series data, telemetry, log storage | |

|

Document-Oriented DBs |

• Stores semi-structured data in documents (JSON, BSON, XML) • Schema-less and flexible • Supports nested data structures • Good for modern app development |

Content management, product catalogs, APIs, evolving schema applications | |

|

Graph Databases |

• Data represented as nodes and relationships • Efficient for traversing complex relationships • Schema flexibility • Optimized for relationship-based queries |

Social networks, recommendation systems, fraud detection |

|

Problem |

Limits & What to do |

Solutions |

|---|---|---|

|

Scale Data Size |

Approaching the maximum server capacity ▻ Distribute tables and databases across multiple machines (nodes) |

Clustering |

|

Scale Read Requests |

Approaching the maximum number of DB server requests ▻ Reduce the number of requests made ▻ Distribute request traffic among different replicas |

Chaching Layer and Replication |

|

Scale Write Requests |

Approaching the maximum number of write requests handled by a DB server ▻ Split writes among multiple instances ▻ Split table records across multiple shards/containers |

Data Partitioning and Sharding |

|

Provide High Availability |

Avoind SPOF ▻ Make services independent by crashes |

Data Replication |

|

Feature |

RUCIO |

OneData |

|---|---|---|

|

Main Use Case |

Scientific data management of CERN experiments (e.g., ATLAS) | Distributed data access and sharing. |

|

SPOF? |

Yes (Centralized Relational Catalog) | No (Distributed DB Catalog) |

|

Data Sharing |

Requires data duplication for cross-institution sharing | Supports federated access without data duplication |

|

Integration Flexibility |

Limited: Specialized for scientific workflows and fixed Data models | Advanced: Designed for integration with different workflows and Data models |

|

Metadata Management |

Basic Support | Advanced metadata handling with multiple formats |

|

Open-Data Support |

Limited | Strong support with integration to open data standards, IVOA, etc |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).