Submitted:

10 June 2025

Posted:

11 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. InSAR Methods

3. Status and Application

3.1. Repeat-Pass Interference

3.1.1. D-InSAR

3.1.2. PS-InSAR

3.1.3. SBAS-InSAR

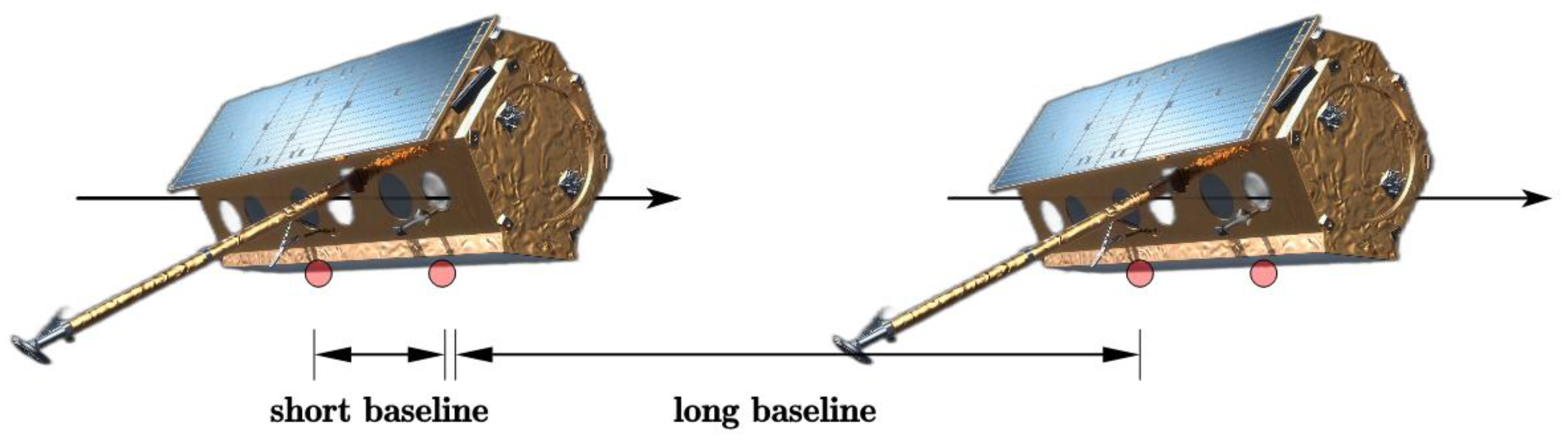

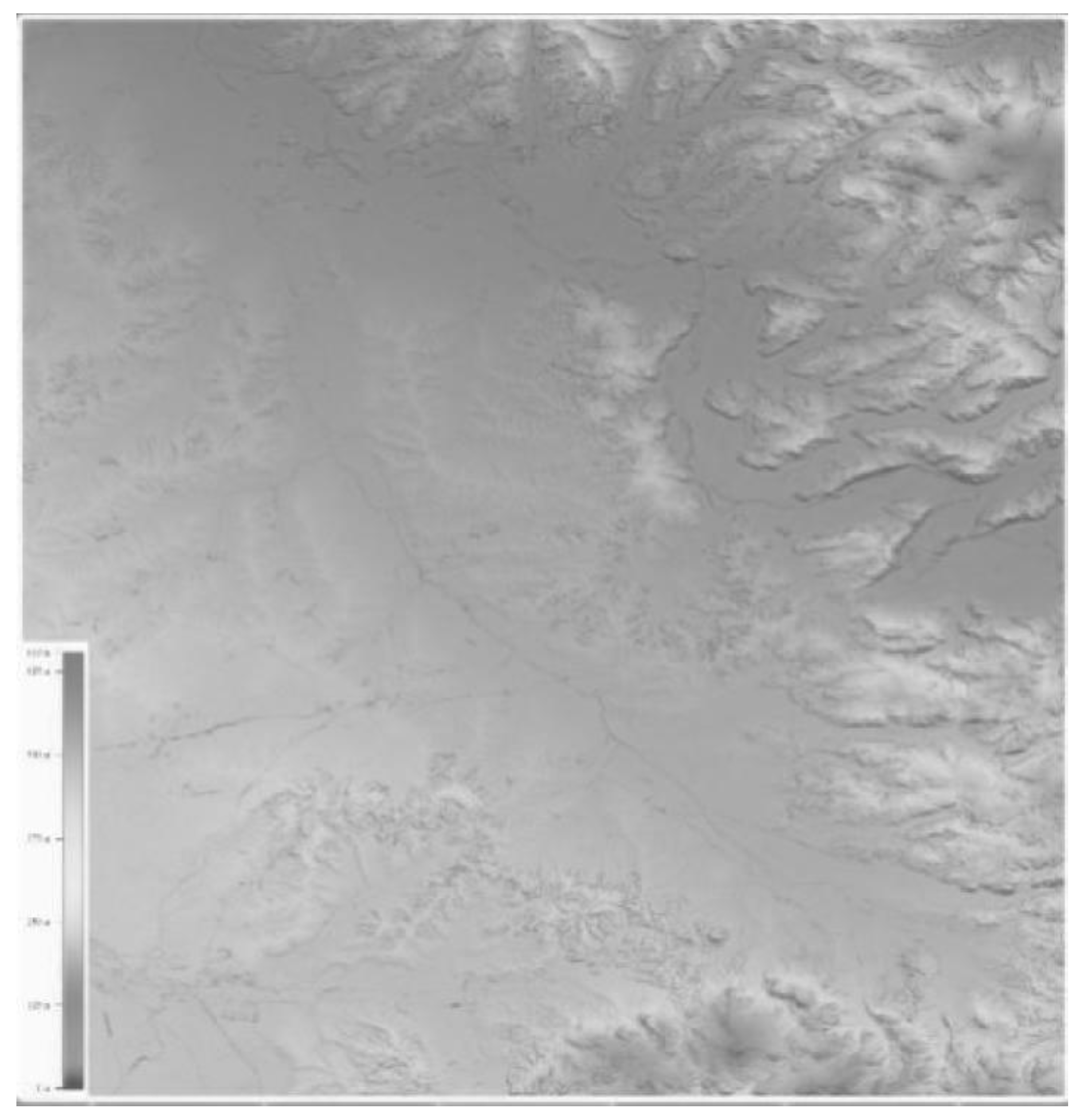

3.2. Single-Pass Interference

3.2.1. CT-InSAR

3.2.2. AT-InSAR

4. Trends and Prospects

4.1. Multidimensional

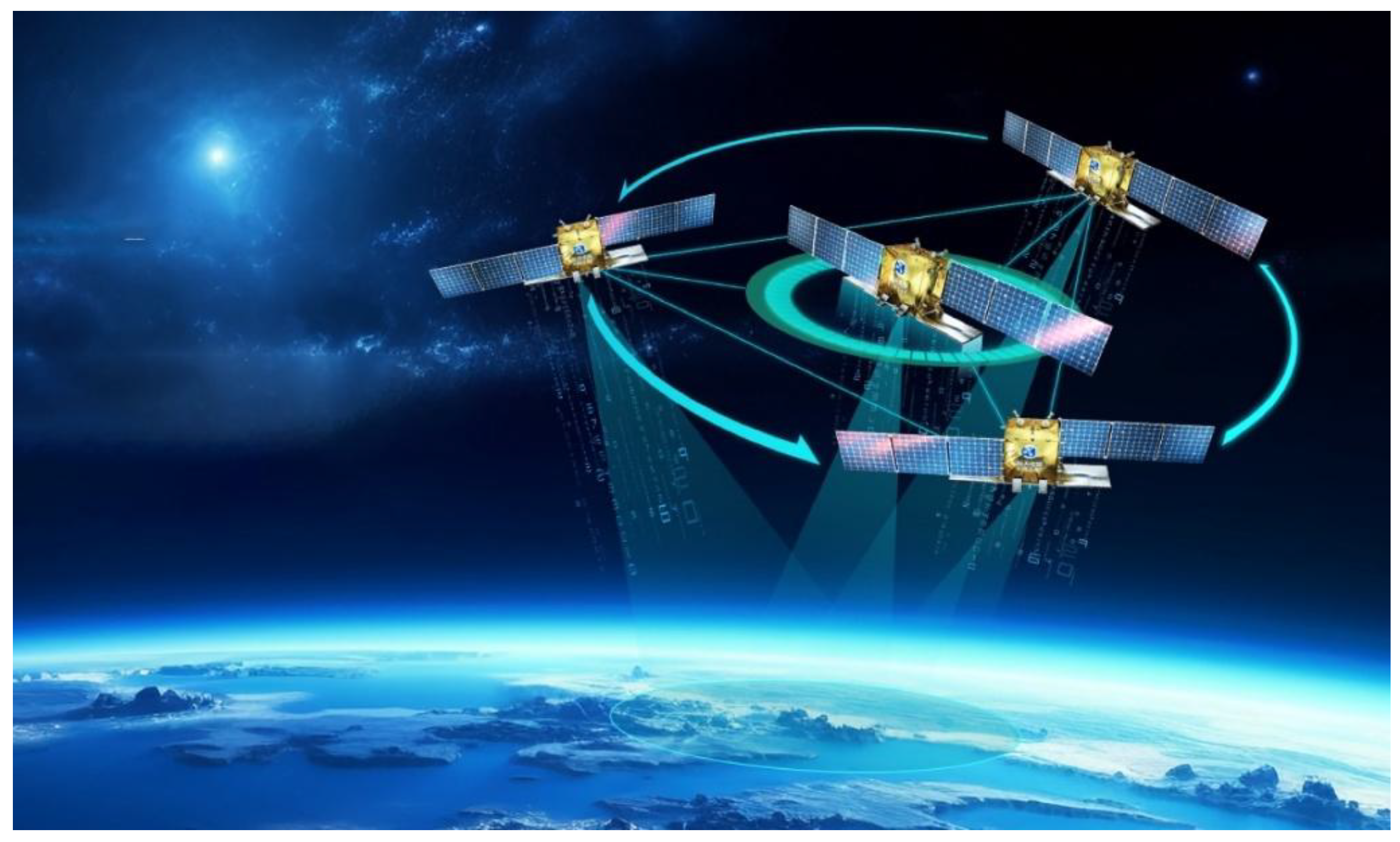

4.1.1. Multi-Star Networking

4.1.2. Multibeam

4.1.3. Multiband

3.1.4. Multi-Baseline

4.2. High-Frame-Rate

4.3. PolInSAR

4.4. HRWS

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- DENG Yunkai; YU Weidong; ZHANG Heng; WANG Wei; LIU Dacheng; WANG Robert. Forthcoming Spaceborne SAR Development. Journal of Radars 2020, 9, 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- CHEN Junli; LIU Yanyang; CHEN Zhonghua; ZHAO Di. Spaceborne Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar: Status and Prospect. Aerospace Shanghai(Chinese&English) 2021, 38, 96–108. [Google Scholar]

- LI Zhenhong; ZHU Wu; YU Chen; ZHANG Qin; ZHNAG Chenglong; LIU Zhenjiang; ZHANG Xuesong; CHEN Bo; DU Jiantao; SONG Chuang; HAN Bingquan; ZHOU Jiawei. Interferometric synthetic aperture radar for deformation mapping: opportunities, challenges and the outlook. Acta Geodaetica et Cartographica Sinica 2022, 51, 1485–1519. [Google Scholar]

- Ouchi, K. Recent Trend and Advance of Synthetic Aperture Radar with Selected Topics. Remote Sensing 2013, 5, 716–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi SHAO; Zhiwei ZHOU; Peifeng MA; Teng WANG. A review of intelligent InSAR data processing: recent advancements, challenges and prospects. Acta Geodaetica et Cartographica Sinica 2024, 53, 1037–1056. [Google Scholar]

- HE Shan; WU Han; LI Jilong. A Review of the Application of InSAR Technology in Digital Terrain Analysis. Science & Technology Vision 2024, 14, 60–64. [Google Scholar]

- WANG Xiaying. Key techniques and their application of InSAR in ground deformation monitoring. Acta Geodaetica et Cartographica Sinica 2022, 51(10), 2244–2244. [Google Scholar]

- ZHAO Xia; MA Xinyan; YU Qian; WANG Zhaobing. Application of high-resolution InSAR technique in monitoring deformations in the Beijing Daxing International Airport. Remote Sensing for Natural Resources 2024, 36, 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- YI Jianfeng; ZHANG Qingjun; LIU Jie; ZHANG Running; ZHAO Lingbo; ZHANG Chi; LIU Yongli. A Review on Development of Formation Flying Interferometric SAR Satellite System. Spacecraft Engineering 2018, 27, 116–122. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, A.E.E.; Ingalls, R.P. Venus: Mapping the Surface Reflectivity by Radar Interferometry. Science 1969, 165, 797–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, L.C. Synthetic Interferometer Radar for Topographic Mapping. Proceedings of the IEEE 1974, 62, 763–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zebker, H.A.; Goldstein, R.M. Topographic Mapping from Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar Observations. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 1986, 91, 4993–4999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, G.; Moreira, A.; Fiedler, H.; Hajnsek, I.; Werner, M.; Younis, M.; Zink, M. TanDEM-X: A Satellite Formation for High-Resolution SAR Interferometry. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing 2007, 45, 3317–3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, M. Operating the X-Band SAR Interferometer of the SRTM. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2000. IEEE 2000 International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium. Taking the Pulse of the Planet: The Role of Remote Sensing in Managing the Environment. Proceedings (Cat. No.00CH37120); 2000; Vol. 6, pp. 2587–2589. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, A.; Prats-Iraola, P.; Younis, M.; Krieger, G.; Hajnsek, I.; Papathanassiou, K.P. A Tutorial on Synthetic Aperture Radar. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Magazine 2013, 1, 6–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, A.K.; Goldstein, R.M.; Zebker, H.A. Mapping Small Elevation Changes over Large Areas: Differential Radar Interferometry. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 1989, 94, 9183–9191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massonnet, D.; Rossi, M.; Carmona, C.; Adragna, F.; Peltzer, G.; Feigl, K.; Rabaute, T. The Displacement Field of the Landers Earthquake Mapped by Radar Interferometry. Nature 1993, 364, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanssen, R. Radar Interferometry: Data Interpretation and Error Analysis. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Radar-Interferometry%3A-Data-Interpretation-and-Error-Hanssen/341cfe9b84770bed948a6113fd98b71ed380bc07 (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- LIU Guoxiang. Principles and applications of InSAR; Science Press: BeiJing, 2019; ISBN 978-7-03-061185-7. [Google Scholar]

- Monserrat, O.; Crosetto, M.; Luzi, G. A Review of Ground-Based SAR Interferometry for Deformation Measurement. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 2014, 93, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, M.; Guifang, Z.; Xuedong, M.; Xinjian, S.; Fangfang, L.; Xiaoke, Z. A Model of In-Depth Displacement under Ms8.1 at Kunlun Earthquake with D-InSAR Co-Seismic Deformation Field. In Proceedings of the 2009 Sixth International Conference on Fuzzy Systems and Knowledge Discovery, August 2009; Vol. 5, pp. 141–144. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, B.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y. Evaluating the Impact of the 2008 China Wenchuan Earthquake on Airports by Insar Technology and Palsar Data. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2024 - 2024 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, July 2024; pp. 3461–3464. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, T.; Fielding, E.; Parsons, B. Triggered Slip: Observations of the 17 August 1999 Izmit (Turkey) Earthquake Using Radar Interferometry. Geophysical Research Letters 2001, 28, 1079–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rott, H. Advances in Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (InSAR) in Earth System Science. Progress in Physical Geography 2009, 33, 769–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LIU Guoxiang; DING Xiaoli; LI Zhiwei; CHEN Yongqi; LI Yonglin; YU Shuipei. ERS Satellite Radar Interferometry: Pre-earthquake and Coseismic Surface Displacements of the 1999 Taiwan Jiji Earthquake. CHINESE JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICS 2002, 45, 165–174. [Google Scholar]

- Peltzer, G.; Rosen, P. Surface Displacement of the 17 May 1993 Eureka Valley, California, Earthquake Observed by SAR Interferometry. Science 1995, 268, 1333–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Li, Z.W.; Ding, X.L.; Zhu, J.J.; Zhang, L.; Sun, Q. Resolving Three-Dimensional Surface Displacements from InSAR Measurements: A Review. Earth-Science Reviews 2014, 133, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, M.E.; Simons, M. A Satellite Geodetic Survey of Large-Scale Deformation of Volcanic Centres in the Central Andes. Nature 2002, 418, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talebian, M.; Fielding, E.J.; Funning, G.J.; Ghorashi, M.; Jackson, J.; Nazari, H.; Parsons, B.; Priestley, K.; Rosen, P.A.; Walker, R.; et al. The 2003 Bam (Iran) Earthquake: Rupture of a Blind Strike-Slip Fault. Geophysical Research Letters 2004, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, T. The Earthquake Deformation Cycle. Astronomy & Geophysics 2016, 57, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, G.; Yu, B.; Dai, K.; Zhang, R.; Chen, Q.; Li, Z. 3D Coseismic Deformations and Source Parameters of the 2010 Yushu Earthquake (China) Inferred from DInSAR and Multiple-Aperture InSAR Measurements. Remote Sensing of Environment 2014, 152, 174–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Xu, B.; Wen, Y.; Liu, Y. Heterogeneous Fault Mechanisms of the 6 October 2008 MW 6.3 Dangxiong (Tibet) Earthquake Using Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar Observations. Remote Sensing 2016, 8, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A map of surface deformation with a resolution of 40 meters nationwide and an accuracy of 5 mm/year [EB/OL]. Available online: http://www.hbeos.org.cn/xwzx/1/2022-08-22/867.html (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- China's first supercomputing InSAR system achieves nationwide surface deformation monitoring ---- Chinese Academy of Sciences [EB/OL]. Available online: https://www.cas.cn/syky/202012/t20201216_4770987.shtml (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Duan, W.; Zhang, H.; Wang, C.; Tang, Y. Multi-Temporal InSAR Parallel Processing for Sentinel-1 Large-Scale Surface Deformation Mapping. Remote Sensing 2020, 12, 3749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Yu, C.; Li, Z.; Utili, S.; Frattini, P.; Crosta, G.; Peng, J. Triggering and Recovery of Earthquake Accelerated Landslides in Central Italy Revealed by Satellite Radar Observations. Nat Commun 2022, 13, 7278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, A.; Prati, C.; Rocca, F. Permanent Scatterers in SAR Interferometry. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2001, 39, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, A.; Savio, G.; Barzaghi, R.; Borghi, A.; Musazzi, S.; Novali, F.; Prati, C.; Rocca, F. Submillimeter Accuracy of InSAR Time Series: Experimental Validation. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2007, 45, 1142–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, A.; Prati, C.; Rocca, F. Nonlinear Subsidence Rate Estimation Using Permanent Scatterers in Differential SAR Interferometry. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2000, 38, 2202–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, N.; Kampes, B.; Eineder, M. DEVELOPMENT OF A SCIENTIFIC PERMANENT SCATTERER SYSTEM: MODIFICATIONS FOR MIXED ERS/ENVISAT TIME SERIES. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper, A.; Zebker, H.; Segall, P.; Kampes, B. A New Method for Measuring Deformation on Volcanoes and Other Natural Terrains Using InSAR Persistent Scatterers. Geophysical Research Letters 2004, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, A.; Fumagalli, A.; Novali, F.; Prati, C.; Rocca, F.; Rucci, A. A New Algorithm for Processing Interferometric Data-Stacks: SqueeSAR. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2011, 49, 3460–3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.A.; Sauber, J.M. Leveraging Multi-Primary PS-InSAR Configurations for the Robust Estimation of Coastal Subsidence. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2024, 21, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyoman Sudi Parwata, I.; Osawa, T. Surface Deformation Monitoring Induced by Volcanic Activity of Mount Agung, Indonesia, by PS-InSAR Using Sentinel-1 SAR from 2014-2021. In Proceedings of the 2021 7th Asia-Pacific Conference on Synthetic Aperture Radar (APSAR), November 2021; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Gu, S.; Li, J.; Tian, X.; Li, L.; Xu, S. Monitoring and Risk Assessment of Urban Surface Deformation Based on PS-InSAR Technology: A Case Study of Nanjing City. IEEE Journal on Miniaturization for Air and Space Systems 2024, 5, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardino, P.; Fornaro, G.; Lanari, R.; Sansosti, E. A New Algorithm for Surface Deformation Monitoring Based on Small Baseline Differential SAR Interferograms. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2002, 40, 2375–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauknes, T.R.; Zebker, H.A.; Larsen, Y. InSAR Deformation Time Series Using an L₁ -Norm Small-Baseline Approach. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2011, 49, 536–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casu, F.; Manconi, A.; Pepe, A.; Lanari, R. Deformation Time-Series Generation in Areas Characterized by Large Displacement Dynamics: The SAR Amplitude Pixel-Offset SBAS Technique. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2011, 49, 2752–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Fielding, E.J.; Cross, P. Integration of InSAR Time-Series Analysis and Water-Vapor Correction for Mapping Postseismic Motion After the 2003 Bam (Iran) Earthquake. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2009, 47, 3220–3230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowter, A.; Bateson, L.; Strange, P.; Ambrose, K.; Syafiudin, M.F. DInSAR Estimation of Land Motion Using Intermittent Coherence with Application to the South Derbyshire and Leicestershire Coalfields. Remote Sensing Letters 2013, 4, 979–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casu, F.; Elefante, S.; Imperatore, P.; Zinno, I.; Manunta, M.; De Luca, C.; Lanari, R. SBAS-DInSAR Parallel Processing for Deformation Time-Series Computation. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2014, 7, 3285–3296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsonov, S.; d’Oreye, N. Multidimensional Time-Series Analysis of Ground Deformation from Multiple InSAR Data Sets Applied to Virunga Volcanic Province. Geophysical Journal International 2012, 191, 1095–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Ji, Y.; Tian, X.; Zhang, W.; Kang, W.; Li, Y.; Zhang, T. Deformation Velocity Monitoring in Kunming City Using Ascending and Descending Sentinel-1A Data with SBAS-InSAR Technique. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2020 - 2020 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium; September 2020; pp. 1993–1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X.; Yang, T.; Wang, Z.; Tang, W. Surface Deformation Analysis in Jiuzhaigou, China Using SBAS-InSAR Technique. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium IGARSS, July 2021; pp. 5350–5353. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, M.; Zhao, C.; Liu, X.; Wang, B. Sequential SBAS-InSAR Backward Estimation of Deformation Time Series. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 2024, 21, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pac, R.D. X-SAR/SRTM - Shuttle Radar Topography Mission: Mapping the Earth from Space. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, M. Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM): Experience with the X-Band SAR Interferometer. In Proceedings of the 2001 CIE International Conference on Radar Proceedings (Cat No.01TH8559); October 2001; pp. 634–638. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, A.; Krieger, G.; Hajnsek, I.; Hounam, D.; Werner, M.; Riegger, S.; Settelmeyer, E. TanDEM-X: A terraSAR-X Add-on Satellite for Single-Pass SAR Interferometry. In Proceedings of the IEEE International IEEE International IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, 2004. IGARSS ’04. Proceedings. 2004; IEEE: Anchorage, AK, USA, 2004; Vol. 2, pp. 1000–1003. [Google Scholar]

- Zink, M.; Bachmann, M.; Brautigam, B.; Fritz, T.; Hajnsek, I.; Krieger, G.; Moreira, A.; Wessel, B. TanDEM-X: A Single-Pass SAR Interferometer for Global DEM Generation and Demonstration of New SAR Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS); IEEE: Milan, July, 2015; pp. 2888–2891. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Cassola, M.; Prats, P.; Schulze, D.; Tous-Ramon, N.; Steinbrecher, U.; Marotti, L.; Nannini, M.; Younis, M.; Lopez-Dekker, P.; Zink, M.; et al. First Bistatic Spaceborne SAR Experiments With TanDEM-X. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sensing Lett. 2012, 9, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

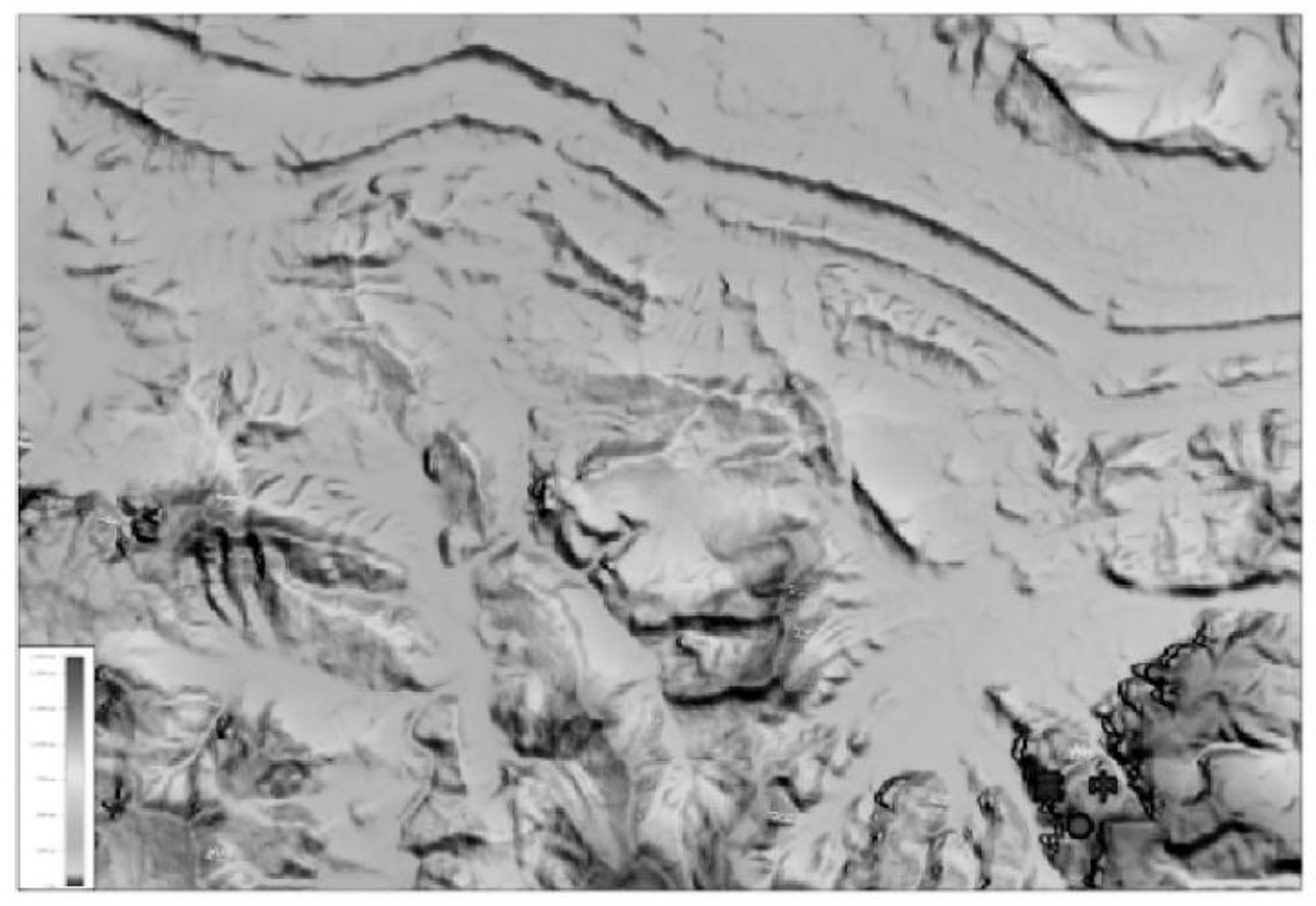

- LOU Liangsheng; LIU Zhiming; ZHANG Hao; QIAN Fangming; HUANG Yan. TIANHUI-2 satellite engineering design and implementation[J]. Acta Geodaetica et Cartographica Sinica 2020, 49, 1252–1264. [Google Scholar]

- XIANG Jianbing; Lü Xiaolei; FU Xikai; XUE Feiyang; YUN Ye; YE Yu; HE Ke. Bistatic InSAR interferometry imaging and DSM generation for TIANHUI-2[J]. Acta Geodaetica et Cartographica Sinica 2022, 51, 2493–2500. [Google Scholar]

- The first "1+3" wheel formation InSAR commercial satellite data product was released [EB/OL]. Available online: https://www.sastind.gov.cn/n10086200/n10086331/c10391350/content.html (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Romeiser, R.; Thompson, D.R. Numerical Study on the Along-Track Interferometric Radar Imaging Mechanism of Oceanic Surface Currents. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2000, 38, 446–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeiser, R.; Suchandt, S.; Runge, H.; Graber, H. Currents in Rivers, Coastal Areas, and the Open Ocean from TerraSAR-X along-Track InSAR. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium; IEEE: Honolulu, HI, USA, July, 2010; pp. 3059–3062. [Google Scholar]

- Romeiser, R.; Alpers, W.; Wismann, V. An Improved Composite Surface Model for the Radar Backscattering Cross Section of the Ocean Surface: 1. Theory of the Model and Optimization/Validation by Scatterometer Data. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 1997, 102, 25237–25250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeiser, R.; Alpers, W. An Improved Composite Surface Model for the Radar Backscattering Cross Section of the Ocean Surface: 2. Model Response to Surface Roughness Variations and the Radar Imaging of Underwater Bottom Topography. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 1997, 102, 25251–25267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeiser, R.; Breit, H.; Eineder, M.; Runge, H.; Flament, P.; de Jong, K.; Vogelzang, J. Validation of SRTM-Derived Surface Currents off the Dutch Coast by Numerical Circulation Model Results. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2003. 2003 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium. Proceedings (IEEE Cat. No.03CH37477), July 2003; Vol. 5, pp. 3085–3087. [Google Scholar]

- Runge, H.; Suchandt, S.; Breit, H.; Eineder, M.; Schulz-Stellenfleth, J.; Bard, J.; Romeiser, R. Mapping of Tidal Currents with SAR along Track Interferometry. In Proceedings of the IEEE International IEEE International IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, 2004. IGARSS ’04. Proceedings. 2004, 2004; IEEE: Anchorage, AK, USA, 2004; Vol. 2, pp. 1156–1159. [Google Scholar]

- Romeiser, R.; Runge, H. Theoretical Evaluation of Several Possible Along-Track InSAR Modes of TerraSAR-X for Ocean Current Measurements. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing 2007, 45, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, U.I.; Rabus, B.; Geudtner, D.; Rashid, M.; Gierull, C. Along Track Interferometry (ATI) versus Doppler Centroid Anomaly (DCA) Estimation of Ocean Surface Radial Velocity Using RADARSAT-2 Modex-1 ScanSAR Data. In Proceedings of the EUSAR 2022; 14th European Conference on Synthetic Aperture Radar, July 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Qi, Y.; Yuan, X.; Liu, J.; Li, H. China’s Gaofen-3 Satellite System and Its Application and Prospect. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2021, 14, 11019–11028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q. System Design and Key Technologies of the GF-3 Satellite. Acta Geodaetica et Cartographica Sinica 2017, 46(3), 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ZHANG Qingjun; HAN Xiaolei; LIU Jie. Technology Progress and Development Trend of Spaceborne Synthetic Aperture Radar Remote Sensing. Spacecraft Engineering 2017, 26, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Qingjun, Z.; Yadong, L. Overview of Chinese First C Band Multi-Polarization SAR Satellite GF-3. AEROSPACE CHINA 2017, 18, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- REN Bo; ZHAO Lingbo; ZHU Fuguo. Design of C-band Multi-polarized Active Phased Array Antenna System for GF-3 Satellite. Spacecraft Engineering 2017, 26, 68–74.

- Yuan, X.; Lin, M.; Han, B.; Zhao, L.; Wang, W.; Sun, J.; Wang, W. Observing Sea Surface Current by Gaofen-3 Satellite Along-Track Interferometric SAR Experimental Mode. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2021, 14, 7762–7770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, E.; Imel, D.; Houshmand, B. Two-Dimensional Surface Currents Using Vector along-Track Interferometry. proc piers' 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Frasier, S.J.; Camps, A.J. Dual-Beam Interferometry for Ocean Surface Current Vector Mapping. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2001, 39, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, C.; Aguirre, M.; Donion, C.; Petrolati, D.; D’Addio, S. Steps towards the Preparation of a Wavemill Mission. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium; IEEE: Vancouver, BC, Canada, July, 2011; pp. 3959–3962. [Google Scholar]

- Yague-Martinez, N.; Márquez, J.; Cohen, M.; Lancashire, D.; Buck, C. Wavemill Proof-of-Concept Campaign. Processing Algorithms and Results. In Proceedings of the EUSAR 2012; 9th European Conference on Synthetic Aperture Radar, April 2012; pp. 312–315. [Google Scholar]

- Zink, M. TanDEM-X Mission Status. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium; IEEE: Munich, July, 2012; pp. 1896–1899. [Google Scholar]

- Zink, M.; Moreira, A. TanDEM-X Mission: Overview, Challenges and Status. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium - IGARSS; IEEE: Melbourne, Australia, July, 2013; pp. 1885–1888. [Google Scholar]

- Romeiser, R.; Runge, H.; Suchandt, S.; Kahle, R.; Rossi, C.; Bell, P.S. Quality Assessment of Surface Current Fields From TerraSAR-X and TanDEM-X Along-Track Interferometry and Doppler Centroid Analysis. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing 2014, 52, 2759–2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchandt, S.; Runge, H.; Suchandt, S. High-Resolution Surface Current Mapping Using TanDEM-X ATI. In Proceedings of the EUSAR 2014; 10th European Conference on Synthetic Aperture Radar, Berlin, Germany, 2014; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Romeiser, R. Surface Current Measurements by Spaceborne Along-Track inSAR - terraSAR-X, tanDEM-X, and Future Systems. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE/OES Eleveth Current, Waves and Turbulence Measurement (CWTM); IEEE: St. Petersburg, FL, 2015; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- S1 Mission. Available online: https://sentiwiki.copernicus.eu/web/s1-mission (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Sentinel-1C Captures First Radar Images. Available online: https://www.esa.int/Applications/Observing_the_Earth/Copernicus/Sentinel-1/Sentinel-1C_captures_first_radar_images (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Gommenginger, C.; Chapron, B.; Martin, A.; Marquez, J.; Brownsword, C.; Buck, C. SEASTAR: A New Mission for High-Resolution Imaging of Ocean Surface Current and Wind Vectors from Space. In Proceedings of the EUSAR 2018; 12th European Conference on Synthetic Aperture Radar, Aachen, Germany, 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Gommenginger, C.; Chapron, B.; Hogg, A.; Buckingham, C.; Fox-Kemper, B.; Eriksson, L.; Soulat, F.; Ubelmann, C.; Ocampo-Torres, F.; Nardelli, B.B.; et al. SEASTAR: A Mission to Study Ocean Submesoscale Dynamics and Small-Scale Atmosphere-Ocean Processes in Coastal, Shelf and Polar Seas. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, D.L.; Martin, A.C.H.; Macedo, K.; Carrasco Alvarez, R.; Horstmann, J.; Marié, L.; Márquez-Martínez, J.; Portabella, M.; Meta, A.; Gommenginger, C.; et al. A New Airborne System for Simultaneous High-Resolution Ocean Vector Current and Wind Mapping: First Demonstration of the SeaSTAR Mission Concept in the Macrotidal Iroise Sea. EGUsphere 2024, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.; McCann, D.; Macedo, K.; Meta, A.; Gommenginger, C.; Portabella, M.; Marié, L.; Filipot, J.F.; Marquez, J.; Martín-Iglesias, P.; et al. Ocean Surface Current Airborne Radar (OSCAR): A New Instrument to Measure Ocean Surface Dynamics at the Sub-Mesoscale.

- Martin, A.; Macedo, K.; Portabella, M.; Marié, L.; Marquez, J.; McCann, D.; Carrasco, R.; Duarte, R.; Meta, A.; Gommenginger, C.; et al. OSCAR: A New Airborne Instrument to Image Ocean-Atmosphere Dynamics at the Sub-Mesoscale: Instrument Capabilities and the SEASTARex Airborne Campaign. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, D.; Martin, A.; Macedo, K.; Gommenginger, C.; Marié, L.; Alvarez, R.C.; Meta, A.; Iglesias, P.M.; Casal, T. OSCAR: Validation of 2D Total Surface Current Vector Fields during the SEASTARex Airborne Campaign in Iroise Sea, May 2022.; Copernicus Meetings. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gommenginger, C.; Martin, A.C.H.; McCann, D.L.; Egido, A.; Hall, K.; Martin-Iglesias, P.; Casal, T. Imaging Small-Scale Ocean Dynamics at Interfaces of the Earth System with the SeaSTAR Earth Explorer 11 Mission Candidate; Copernicus Meetings. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Work Continues on NISAR Satellite as Mission Looks Toward Launc. Available online: https://nisar.jpl.nasa.gov/news/58/work-continues-on-nisar-satellite-as-mission-looks-toward-launch (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- McDonald, K.; Podest, E.; Steiner, N.; Tesser, D.; Zimmermann, R.; Niessner, A.; Rios, M.; Urquiza, J.D.; Huneini, R.; Downs, B.; et al. NISAR: Seeing Beyond the Trees to Understand Wetlands, Forests and Biodiversity. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2024 - 2024 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, July 2024; pp. 6775–6778. [Google Scholar]

- NISAR (NASA-ISRO Synthetic Aperture Radar) - eoPortal. Available online: https://www.eoportal.org/satellite-missions/nisar (accessed on 4 February 2025).

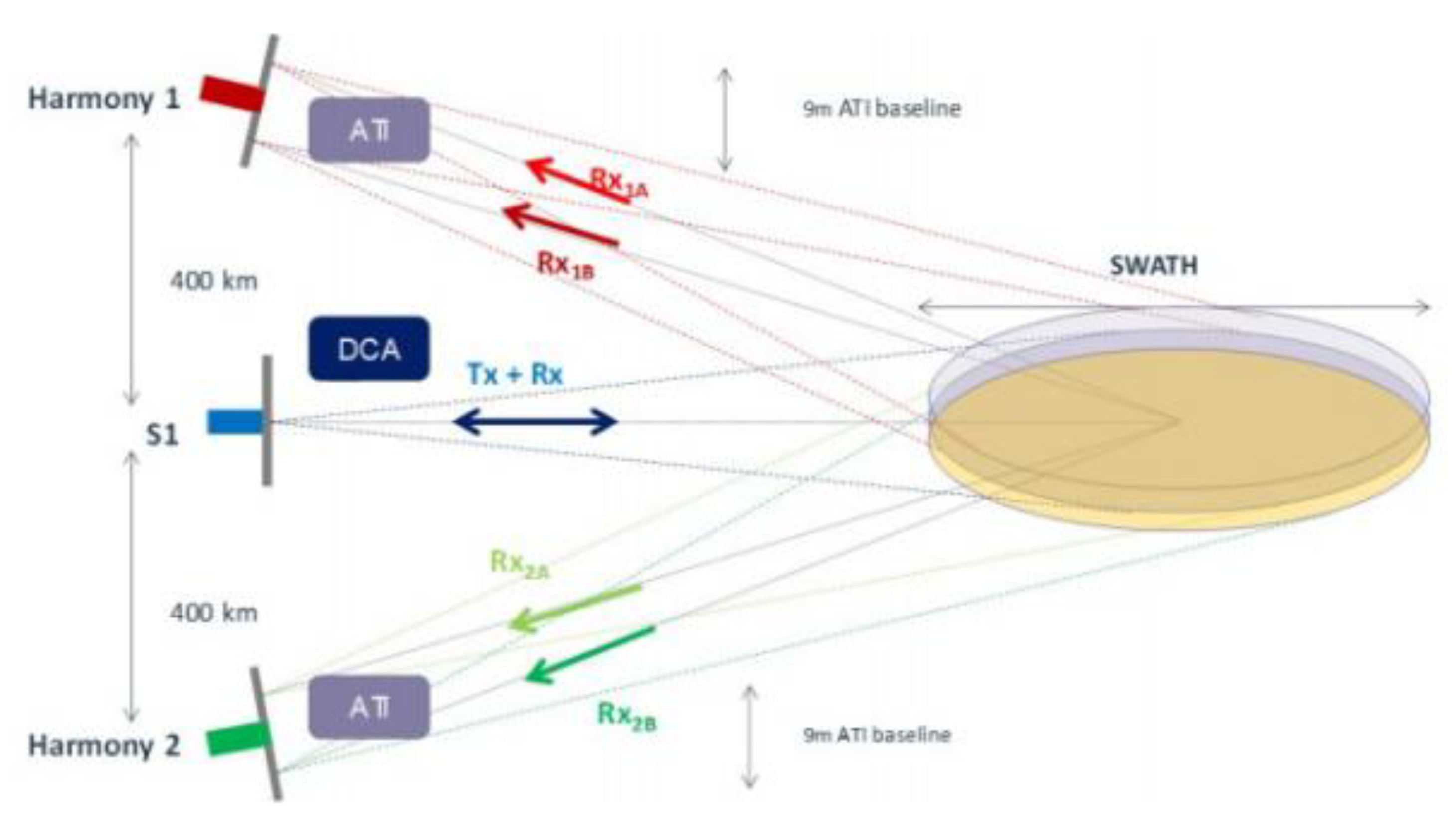

- Lopez-Dekker, P.; Rott, H.; Prats-Iraola, P.; Chapron, B.; Scipal, K.; Witte, E.D. Harmony: An Earth Explorer 10 Mission Candidate to Observe Land, Ice, and Ocean Surface Dynamics. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2019 - 2019 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium; IEEE: Yokohama, Japan, 2019; pp. 8381–8384. [Google Scholar]

- Theodosiou, A.; Kleinherenbrink, M.; Lopez-Dekker, P. Wide-Swath Ocean Topography Using Formation Flying Under Squinted Geometries: The Harmony Mission Case. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium IGARSS; IEEE: Brussels, Belgium, July 11, 2021; pp. 2134–2137. [Google Scholar]

- LOU Liangsheng; LIU Zhiming; ZHANG Hao; QIAN Fangming; ZHANG Xiaowei. Key technologies of TIANHUI-2 satellite system. Acta Geodaetica et Cartographica Sinica 2022, 51, 2403–2416. [Google Scholar]

- BAO Zhongwen; MA Li; MA Honghai. Analysis of Operation Maintenance and Application of TianHui-2 Satellite. Geomatics & Spatial Information Technology 2023, 46, 135–138.

- LI Da; CAO Yujia; HAO Lianxiu; Guan Haitao. Comparative analysis of DSM extraction accuracy from Tianhui-2 and ZY-3 satellites. Geomatics & Spatial Information Technology 2024, 47, 115–118. [Google Scholar]

- "Aerospace HongTu, No. 1" satellite remote sensing image product set [EB/OL]. Available online: https://book.yunzhan365.com/gdtl/tojf/mobile/index.html (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Hobbs, S.; Mitchell, C.; Forte, B.; Holley, R.; Snapir, B.; Whittaker, P. System Design for Geosynchronous Synthetic Aperture Radar Missions. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2014, 52, 7750–7763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomiyasu, K. Synthetic Aperture Radar in Geosynchronous Orbit. In Proceedings of the 1978 Antennas and Propagation Society International Symposium; March 1978; Vol. 16, pp. 42–45. [Google Scholar]

- Bruno, D.; Hobbs, S.E. Radar Imaging From Geosynchronous Orbit: Temporal Decorrelation Aspects. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2010, 48, 2924–2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monti Guarnieri, A.; Leanza, A.; Recchia, A.; Tebaldini, S.; Venuti, G. Atmospheric Phase Screen in GEO-SAR: Estimation and Compensation. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2018, 56, 1668–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai-Pin, L.I.; Ming-Yi, H.E.; Ya-Lin, Z.H.U.; Guang-Ting, L.I.; Bo, L.I.U. Imaging Experiment with Long Integrated Time and Curved Trajectory for Geosynchronous Obit SAR. Chinese Space Science and Technology 2015, 35, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Chen, Z.; Dong, X.; Cui, C. Multistatic Geosynchronous SAR Resolution Analysis and Grating Lobe Suppression Based on Array Spatial Ambiguity Function. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2020, 58, 6020–6038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ZHANG Qingjun; NI Chong; DAI Chao; LIU Liping; TANG Zhihua; SHU Weiping. System design and key technologies of No.4 land exploration satellite 01. Chinese Space Science and Technology 2025, 45, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- FENG Tao; ZAHNG Qingjun; LIN Kunyang; WANG Lipeng; ZHANG Qiao; YANG Jungang; XIAO Yong. System design of spaceborne large aperture perimeter truss antenna. Chinese Space Science and Technology 2025, 45, 24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Papathanassiou, K.P.; Cloude, S.R. Polarimetric Effects in Repeat-Pass SAR Interferometry. In Proceedings of the IGARSS’97. 1997 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium Proceedings. Remote Sensing - A Scientific Vision for Sustainable Development; August 1997; Vol. 4, pp. 1926–1928. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, F.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Suo, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Xing, C.; Guo, H. Polarimetric Synthetic Aperture Radar Speckle Filter Based on Joint Similarity Measurement Criterion. Remote Sensing 2023, 15, 5224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kugler, F.; Schulze, D.; Hajnsek, I.; Pretzsch, H.; Papathanassiou, K.P. TanDEM-X Pol-InSAR Performance for Forest Height Estimation. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2014, 52, 6404–6422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, J.; Bian, M.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y. Dual-Frequency Pol-SAR Interferometry Employing Formation Flying Based on Master Satellite and Distributed Small Satellite. In Proceedings of the 2019 6th Asia-Pacific Conference on Synthetic Aperture Radar (APSAR); IEEE: Xiamen, China, November, 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

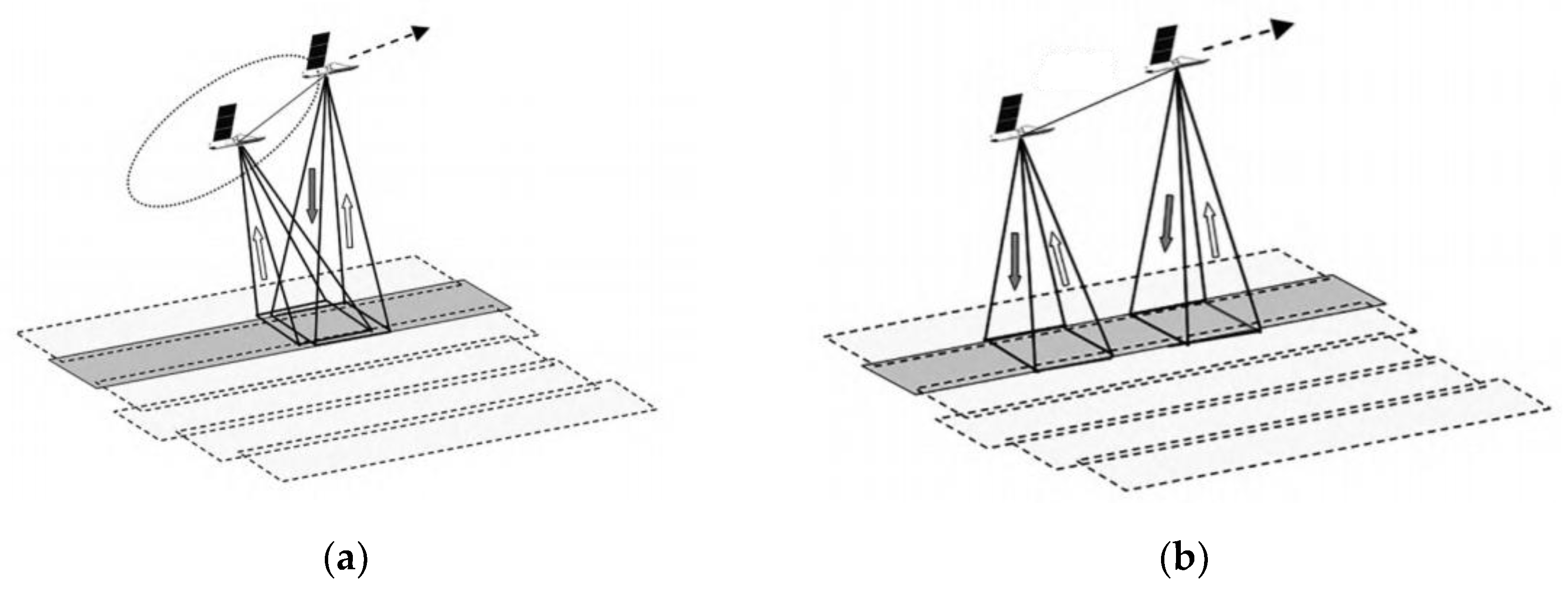

- Gierull, C.H.; Sikaneta, I. Potential Marine Moving Target Indication (MMTI) Performance of the RADARSAT Constellation Mission (RCM). In Proceedings of the EUSAR 2012; 9th European Conference on Synthetic Aperture Radar, April 2012; pp. 404–407. [Google Scholar]

- Wenxue, F.; Huadong, G.; Xinwu, L.; Bangsen, T.; Zhongchang, S. Extended Three-Stage Polarimetric SAR Interferometry Algorithm by Dual-Polarization Data. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2016, 54, 2792–2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JAXA | First Observation Image of L-Band Synthetic Aperture Radar (PALSAR-3) on Advanced Radar Satellite "DAICHI-4" (ALOS-4) [EB/OL]. Available online: https://www.jaxa.jp/press/2024/07/20240731-1_j.html (accessed on 4 February 2025).

| Geophysical phenomenon | Process classification | Spatial scale/km | Deformation scale/mm | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instantaneous | Slow | Reversible | Irreversible | |||

| Active volcano rises or sinks | — | ✓ | ✓ | — | < 20 | < 5 |

| Volcanic eruption | ✓ | — | — | ✓ | < 20 | > 50 |

| Earthquake coseismic deformation | ✓ | — | — | ✓ | 50~100 | > 50 |

| Deformation before and after earthquake | — | ✓ | — | ✓ | 50~100 | < 5 |

| Crustal fault movement | — | ✓ | — | ✓ | > 20 | < 5 |

| Surface settlement | — | ✓ | — | ✓ | 0.5~20 | 1~20/a |

| Mining subsidence | ✓ | — | — | ✓ | 0.1~10 | 1~100/d |

| Landslide (foreboding) | — | ✓ | — | ✓ | 1~20 | 1 |

| Landslide (Eruption) | ✓ | — | — | ✓ | 1~20 | > 1000 |

| Measurement | Precision level | GNSS | D-InSAR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial coverage | Discrete point | Discrete point | Surface covering |

| Accuracy | mm | mm | mm |

| Periodic velocity | Long and slow | Short and fast | Short and fast |

| Operating condition | According to the weather | All-weather | All-weather |

| Cost | High | higher | low |

| DEM acquisition technique | Coverage | DEM accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Ground | Local, large scale mapping range | 0.01~0.1m |

| Airborne photogrammetry | Region | 0.1~1m |

| Airborne lidar | Region | 0.5~2m |

| InSAR | Regional to global | 1~20m |

| Shadow mapping | Regional to global | Slope<=2°,22m |

| Stereo mapping | Region | 10~100m |

| Requirement | Specification | DTED-2 | HRTI-3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relative vertical accuracy | 90% linear point-to-point | 12 m (slope<20%) | 2 m (slope<20%) |

| error over a 1° × 1° cell | 15 m (slope>20%) | 4 m (slope>20%) | |

| Absolute vertical accuracy | 90% linear error | 18 m | 10 m |

| Relative horizontal | 90% circular error | 15 m | 3 m |

| Horizontal accuracy | 90% circular error | 23 m | 10 m |

| Spatial resolution | independent pixels | 30 m (1 arc sec at equator) | 12 m (0.4 arc sec at equator) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).