1. Introduction

The global COVID-19 vaccination campaign, launched in late 2020, has been the largest inoculation effort in human history, widely credited with curbing infection rates and reducing morbidity and mortality across populations (Fitzpatrick et al., 2022; Kirwan et al., 2022; Prof Peter Hotez MD PhD [@PeterHotez], 2025). However, such claims often rely on general assumptions, with limited direct evidence regarding specific subpopulations, including those with autoimmune disorders (Frasca et al., 2023). As a result, alongside its widespread uptake, the scale of this campaign has intensified scrutiny of vaccine safety, including concerns about possible associations with autoimmune disorders, even among researchers otherwise strongly supportive of vaccination (Guo et al., 2023; Hromić-Jahjefendić et al., 2023).

These concerns have emerged upon reports of exacerbated or new-onset autoimmune disorders following vaccination, which have raised questions about the safety, efficacy, and immunogenicity of COVID-19 vaccines, including whether COVID-19 vaccines might trigger autoimmune processes in certain individuals (Jara et al., 2022; Watad et al., 2017). Observational studies, pharmacovigilance reports, and case series have documented such associations across a range of disorders, including Graves’ disease, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and type 1 diabetes mellitus (Guo et al., 2023; Mahroum et al., 2022). A particularly concerning condition, acute transverse myelitis, has also been reported in temporal association with COVID-19 vaccination, with a recent, population-based study in Korea identifying a significantly elevated incidence rate ratio for acute transverse myelitis within 42 days post-vaccination across several vaccine platforms, including both viral vector and mRNA-based vaccines (Lim et al., 2025).

Such findings are not without precedent, nor limited to COVID-19 vaccines. Vaccine safety researchers have long acknowledged that while vaccines are designed to prevent infectious diseases, they may also act as environmental triggers of autoimmune phenomena via immune cross-reactivity and adjuvant effects, and a decades-long body of research has examined the relationship between vaccines and autoimmune phenomena. Pioneering contributions include those of Yehuda Shoenfeld and colleagues, who identified patterns of vaccine-induced autoimmunity across various vaccines, including hepatitis B, influenza, and measles-mumps-rubella (Cohen & Shoenfeld, 1996; Guimarães et al., 2015; Shoenfeld & Aron-Maor, 2000). These investigations have highlighted mechanisms such as molecular mimicry, bystander activation, and the role of adjuvants in breaking immune tolerance – the latter a constellation of factors that may lead to what in 2011 Shoenfeld termed the autoimmune inflammatory syndrome induced by adjuvants (ASIA) (Shoenfeld & Agmon-Levin, 2011).

The COVID-19 vaccine experience, however, provides an unprecedented opportunity to explore these questions at scale, given the massive exposure of diverse populations to relatively new vaccine technologies, especially the novel mRNA platform. Therefore, we undertook this scoping review to investigate the evidence for associations between COVID-19 vaccines and six major autoimmune disorders: Graves’ disease, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and type 1 diabetes mellitus. These conditions were selected based on their clinical relevance and the significant number of individuals affected, as identified by prior research categorizing the most consequential autoimmune diseases in terms of prevalence and severity (Cooper et al., 2009; Cooper & Stroehla, 2003; Jacobson et al., 1997).

Building on our previously published protocol (Chaufan et al., 2023), the goal of this scoping review was to synthesize data from peer-reviewed and preprint sources reporting on autoimmune phenomena following COVID-19 vaccination, in individuals with pre-existing autoimmune disorders - whether in the form of flares or of new autoimmune disorders – or as de novo autoimmune conditions in individuals with no prior autoimmunity.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Search Strategy

We conducted a scoping review as per Arksey and O’Malley’s framework (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005). These authors propose that, in contrast to systematic reviews that “typically focus on a well-defined question where appropriate study designs can be identified in advance [and] provide answers to questions from a relatively narrow range of quality assessed studies”, scoping reviews help to “address broader topics where many different study designs might be applicable [and are] “less likely to seek to address very specific research questions nor, consequently, to assess the quality of included studies” (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005, p. 20), thus our choice of this approach. Our analysis was enhanced by Levac et al.’s team-based approach, which proposes that throughout the review, from articulating a research question, identifying, and selecting relevant studies, charting the data and collating, summarizing, and reporting results, the process should be iterative and cooperative, i.e., “team-based” (Levac et al., 2010). This approach helps research teams address unforeseen practical challenges, such as the need to refine inclusion/exclusion criteria during the screening and selection process. Scoping reviews, like systematic reviews, often evaluate interventions, but they can also be performed to appraise broader phenomena, i.e., “phenomena of interest” (Munn et al., 2018) – in our case, the evidence for associations and underlying mechanisms between COVID-19 vaccinaiton and autoimmune disorders.

We followed the PRISMA-ScR guidelines (Tricco et al., 2018) and searched two electronic databases - PubMed and the WHO COVID-19 Global Database – on June 15th, 2023, to identify studies published between December 2020 and June 2023 that reported clinical manifestations of autoimmune diseases occurring after COVID-19 vaccination. For PubMed, we searched MeSH Major Topic terms [“Graves disease” OR Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis” OR “multiple sclerosis” OR “rheumatoid arthritis” OR “systemic lupus erythematosus” OR “type 1 diabetes” OR “autoimmunity” OR “autoimmune diseases” OR “autoimmune disorders”] combined with [“COVID-19 vaccines”]. For the WHO search, the same terms were searched as [Title, abstract, subject]. Initial eligibility criteria included: (i) publication between 2000 and 2023, (ii) English language, and (iii) pre-print or published status. Reports by leading national and international health agencies - for example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization - were consulted to contextualize the study findings but were not included in the data set unless they met all eligibility criteria.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

We included articles in English that referred to the association between any type of COVID-19 vaccine and an autoimmune disorder and that reported empirically verifiable clinical manifestations of autoimmunity. There were no temporal or geographic restrictions, and all populations were eligible regardless of age, sex/gender, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, or national origin. Articles had to be accessible through the libraries of the authors’ academic or professional affiliations. To capture the broadest range of perspectives on the association between COVID-19 vaccines and autoimmune disorders, we included all article types provided that they met these inclusion criteria.

2.3. Search Methods for Identifying Data

Before selecting articles for assessment, we conducted a preliminary screening of the search results to discard irrelevant material. One reviewer initially scanned titles and retained only those that met the inclusion criteria: (1) articles reporting on the association between any type of COVID-19 vaccine and an autoimmune disorder; (2) focus on empirically verifiable clinical manifestations of autoimmune disorders; (3) availability through any of the library websites of the authors’ affiliated universities; and (4) in English. Next, two reviewers independently screened the remaining abstracts according to the review objectives and excluded studies based on the following criteria: (1) not focused on COVID-19, (2) not focused on vaccines, (3) not focused on autoimmunity, (4) no identifiable clinical outcome, (5) no original or primary data, or (6) not in English. In cases of uncertainty about the relevance of an abstract, a third reviewer broke the tie, and full-text retrieval was undertaken if needed.

2.4. Data Selection Process

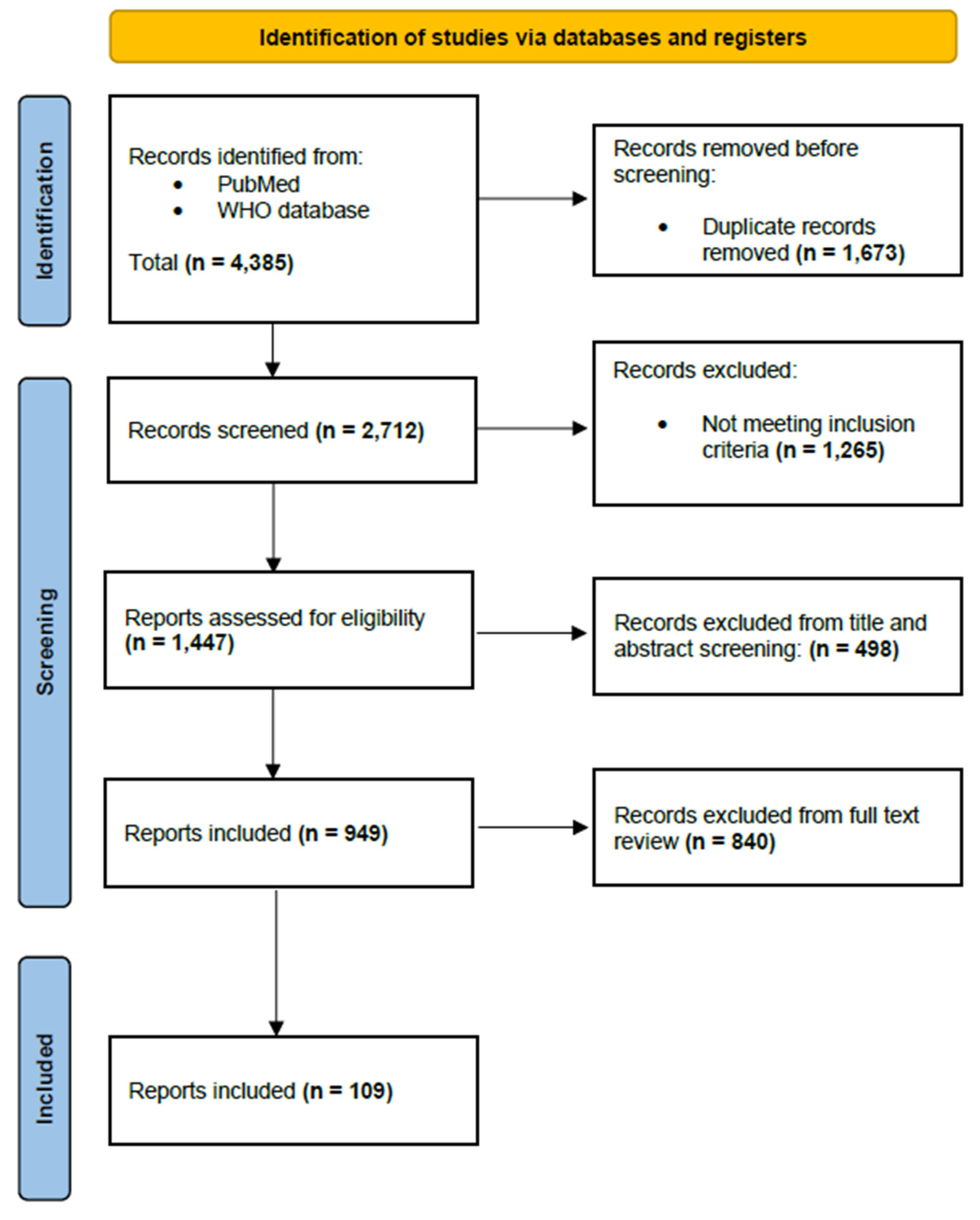

We identified a total of n = 4,385 articles; n = 1,673 duplicates were removed, resulting in n = 2,712 articles for screening. An additional n = 1,265 articles were excluded after title and abstract review, leaving n = 1,447 articles for further screening. We further limited the dataset to articles published in the 12 months following the peak COVID-19 vaccination period in 2021, for substantive and logistical reasons: first, this was the period when both primary series vaccines and boosters became broadly available to general populations for whom access had been formerly limited, and when booster acceptance was high - around 79% (Galanis et al., 2022), and second, our team’s resources were limited. This decision further restricted inclusion to articles published in 2022, reducing the dataset to n = 498. Two reviewers independently determined whether the abstracts met the inclusion criteria, with disagreements resolved through full team discussion. After full-text review, n = 109 articles were included for data charting (

Figure 1).

We monitored inter-rater reliability throughout the screening process, assessing agreement after approximately one-fourth of the retrieved articles were screened, and took corrective measures if reliability fell below 80% (Shea et al., 2017). Articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria but contained relevant contextual material were narratively summarized in the background section. Throughout the screening process, we used Rayyan literature review management software (

https://www.rayyan.ai/), which facilitated double-blind screening, recorded inclusion and exclusion decisions, and flagged disagreements between reviewers.

2.5. Data Charting and Synthesis

Data charting was assisted by a codebook and performed using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, was conducted by two researchers, and was tailored to capture the phenomenon of interest (Table 1). Before initiating full data charting, two reviewers independently charted a sample of studies, and the team met to calibrate the approach and discuss results. Charting categories included the following: details about article type (e.g., study methodology and population demographics); data informing our phenomenon of interest (e.g., autoimmune manifestation, vaccine type, adverse events, causal relationships, mechanism of action, authors’ support of vaccination for patients with autoimmune disorders); and contextual factors (e.g., country where study was reported, author affiliations, reported funding sources and conflicts of interest).

3. Results

3.1. Article Characteristics

The articles included in this scoping review reported on methodologically diverse study designs. They comprised case reports (52/109; 47.7%), case series (15/109; 13.7%), cohort studies (28/109; 25.7%), cross-sectional studies (12/109; 11.1%), and randomized trials (2/109; 1.8%). First authors were affiliated with institutions located primarily in the United States (21/109; 19.2%), Italy (15/109; 13.8%), and Japan (13/109; 11.9%), with additional contributions from researchers based in China, India, Iran, Germany, Brazil, France, Israel, Poland, Austria, Kuwait, Thailand, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, South Korea, Norway, the United Kingdom, Tunisia, Malaysia, Egypt, Belgium, Puerto Rico, Chile, Colombia, Spain, Peru, Greece, Singapore, and Austria.

Most study authors did not declare any conflicts of interest (64/109; 58.7%) – a minority did not mention them (18/109; 16.5%), while slightly over one quarter (27/109; 24.8%) provided explicit conflict-of-interest statements. The latter predominantly involved ties to pharmaceutical companies, including AstraZeneca, Bayer, Biogen, Eli Lilly, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, Takeda, Teva, and others. Funding sources were declared by about one third of authors (33/109; 30.3%), with funding coming from a range of institutional or governmental granting agencies, non-profit organizations, and/or pharmaceutical companies (Table 2).

All included articles focused on at least one of the six autoimmune disorders of interest - about one third on multiple sclerosis (36/109; 33.1%), followed by systemic lupus erythematosus (31/109; 28.4%), type 1 diabetes (16/109; 14.7%), Graves’ disease (13/109; 11.9%), and rheumatoid arthritis (13/109; 11.9%) – with a few (11/109; 10.1%) mentioning more than one disorder. Virtually all studies focused on adult patients (106/109; 97.2%), only two (2/109; 1.9%) researched pediatric patients, while one study (1/109; 0.9%) did not include patients but surveyed physicians. For most studies, the research objective was to report individual cases or case series documenting the relationship between autoimmune disorders and COVID-19 vaccination, including adverse events and COVID-19 infection (88/109; 80.8%), while the remainder focused on immunological responses and vaccine safety analyses (21/109; 19.2%). Nearly half of the studies (52/109; 47.7%) explicitly mentioned outcomes of interest, including humoral responses (21/52; 40.4%), adverse events and flares (13/52; 25%), clinical assessments such as hospitalization or COVID-19 infection (8/52; 15.4%), vaccine safety (6/52; 11.6%), and disease relapses (4/52; 7.6%).

3.2. Relationship Between COVID-19 Vaccines and Autoimmune Disorders

Associations between COVID-19 vaccination and one of the selected six major autoimmune diseases - Graves’ disease, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and type 1 diabetes mellitus - were reported across all included articles. Over half of the studies (61/109; 56%) suggested a causal direction for these associations, while the rest reported either an unclear causal direction (22/109; 20.2%) or no causal direction (26/109; 23.9%). Articles suggesting a causal relationship included those reporting: 1) relapses, flares, or complications of pre-existing autoimmune disorders attributed to COVID-19 vaccination (e.g., (Yakou et al., 2022)), 2) new autoimmune disorders diagnosed post-vaccination in patients with existing autoimmune disorders (Etemadifar et al., 2022; Manta et al., 2022)) and 3) new autoimmune disorders diagnosed post-vaccination in previously healthy individuals or individuals without a prior history of autoimmune disorder (e.g., (Chaudhary et al., 2022; di Filippo et al., 2023)).

Some authors described cases in which patients were identified as having undiagnosed autoimmune disorders becoming clinically apparent following vaccination, yet generally the assertion that vaccines “triggered” a previously unknown disorder was largely speculative. For instance, Mele et al. reported the case of a patient who “before receiving the vaccine […] did not know he had multiple sclerosis” – i.e., was asymptomatic - asserting that the disorder predated vaccination based on “older regions of demyelination in the left frontal horn” revealed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and interpreted as “chronic” lesions (Mele et al., 2022, p. 3). However, because no pre-vaccination imaging was cited providing evidence of such “older regions”, it could not have been possible for the authors to determine if these regions indeed predated vaccination or developed in close succession to the acute episode.

Other studies highlighted the difficulty of distinguishing between relapses or flares in autoimmune disease and adverse events from vaccination, underscoring the risk of misclassifying vaccine-induced adverse events as disease flares or relapses, particularly in the absence of laboratory-based confirmation (e.g., (Barbhaiya et al., 2022)). Other authors described new or worsening disease after vaccination, while also reporting the lack of sufficient evidence to establish causality (e.g., (Al-Midfai et al., 2022)). Finally, almost half of the articles described potential mechanisms of action connecting COVID-19 vaccination and autoimmune phenomena. These discussions addressed either autoimmune symptomatology in general or the six autoimmune conditions of focus. The relationship between vaccination and autoimmune processes - including causal direction and mechanisms of action - is discussed in

Section 4.

3.3. Relapses or Flares in Individuals Already Experiencing Specific Autoimmune Disorders

Over half of the articles (65/109; 59.6%) reported relapses or flares in patients with autoimmune disorders (except for Hashimoto’s thyroiditis) following COVID-19 vaccination. Within this group, multiple sclerosis was the most frequently reported autoimmune condition associated with such events. We present information about the six selected disorders in alphabetical order.

3.3.1. Relapses or Flares in Graves’ Disease

Patrizio et al. (2022) reported two cases of acute relapse in patients with Graves’ disease occurring within days of receiving the Pfizer BNT162B2 mRNA vaccine (hereafter “Pfizer vaccine”) (Patrizio et al. (2022). Ruggeri et al. (2022) reported a case of a Graves’ disease relapse in a 61-year-old man after a third dose of the Pfizer vaccine (Ruggeri et al. (2022).

3.3.2. Relapses or Flares in Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis

As mentioned earlier, no articles reported relapses or flares in patients with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis following COVID-19 vaccination.

3.3.3. Relapses or Flares in Multiple Sclerosis

Al-Midfai et al. (2022) reported a case of worsening multiple sclerosis symptoms within two weeks of a second dose of the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine, noting that this was the first reported case of a multiple sclerosis flare associated with this particular vaccine, whereas previous reports involved Pfizer, Moderna mRNA-1273 (hereafter “Moderna”) and AstraZeneca ChAdOx1 (hereafter “AstraZeneca”) vaccines (Al-Midfai et al., 2022). Lohmann et al. (2022) described a case of “severe” and “progressive” worsening multiple sclerosis symptoms within 23 days of a first dose of the Pfizer vaccine, including sensorimotor paraparesis, longitudinal extensive transverse myelitis, incontinence, and optic neuritis (Lohmann et al., 2022, p. 2). The patient had also experienced worsening paraparesis less than one month earlier following tetanus and pneumococcal vaccinations, after a lengthy history of stabilization without disease-modifying therapies. Kataria et al. (2022) reported multiple sclerosis relapse within three weeks of the second dose of the Pfizer vaccine (Kataria et al., 2022), citing other researchers who suggested that vaccines may overstimulate the immune system, precipitating the transition from subclinical to clinical disease within 30 days (Coyle et al., 2021; McDonald et al., 2021). Giossi et al. (2022) reported two - out of 39 - cases of multiple sclerosis relapse in patients on disease modifying therapies after a second dose of the Pfizer vaccine (Giossi et al., 2022).

Dreyer-Alster et al. (2022) reported mild to severe flares or acute relapses in 3.8% (8/211) of multiple sclerosis patients after a booster dose of the Pfizer vaccine, compared to 4.8% of patients reporting such incidents after their second dose (Dreyer-Alster et al., 2022). They also reported that symptoms resolved spontaneously or were treated with intravenous high-dose methylprednisolone. Gad et al. (2022) reported multiple sclerosis relapses in 33.3% of 65 vaccinated patients within a sample of 160 patients, compared to 12.8% (5/39) of relapses after confirmed COVID-19 infection – 39 within the 160 patient sample (Gad et al., 2022). Importantly, the authors noted that most unvaccinated patients – 42 in addition to the confirmed 39 cases - also reported symptoms compatible with COVID infection that they had not communicated to their doctors - which could indicate an infection rate as high as “50% of total MS patients” (Gad et al., 2022, p. 2). While the authors did not elaborate, if this were the case, then it would mean that the rate of relapses among unvaccinated cases was even lower than the reported 12.8%. It is also worth noting that the study included only patients under 50 years old and without significant comorbidities - diabetes, hypertension, or other chronic illnesses - factors that could influence both COVID-19 severity and relapse rates. Nevertheless, authors concluded that the “risk of relapse [was] low either with infection or vaccination” (Gad et al., 2022, p. 1).

3.3.4. Relapses or Flares in Rheumatoid Arthritis

Nakamura et al. (2022) documented a severe flare of rheumatoid arthritis occurring within 10 days of receiving the Moderna vaccine in a patient who had been in remission for 20 years (Nakamura et al. 2022). The flare was accompanied by fever, arthralgia, and Epstein-Barr virus reactivation. The authors “speculated” that mRNA vaccine components may activate innate immune receptors, thereby triggering downstream immune responses and possibly contributing to both Epstein-Barr virus reactivation and rheumatoid arthritis relapse; they noted that while the exact mechanism remains unclear, the case illustrates how post-vaccination immune activation may exacerbate autoimmune phenomena in some individuals (Nakamura et al., 2022, p. 2075). Other authors like Zhao et al. (2022) reported that 4.8% (2/42) of the rheumatoid arthritis patients developed significant joint pain, knee effusion, and hand and foot swelling after receiving two doses of the Sinovac inactivated vaccine, while noting that “it is undetermined whether the adverse events are related to the vaccination” (Zhao et al. (2022, p. 6)).

3.3.5. Relapses or Flares in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

In patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, several studies reported flares following vaccination. Sugimoto et al. (2022) documented exacerbations of cutaneous lupus symptoms after the first dose of the Moderna vaccine (Sugimoto et al. (2022). Other studies indicated increases in autoantibody levels and mild disease flares post-vaccination (Kreuter et al., 2022).

3.3.6. Relapses or Flares in Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus

A limited number of articles addressed type 1 diabetes mellitus, noting worsening glycemic control following COVID-19 vaccination – for instance, transient hyperglycemia and episodes of diabetic ketoacidosis (Ganakumar et al. (2022). However, such articles also asserted that adverse events were rare and that they did not outweigh the benefits of vaccination in this population.

3.4. Vaccination Associated with New Autoimmune Disease in Autoimmune Patients

In addition to relapses or flares of existing autoimmune disorders, several studies (12/109; 11%) also reported the emergence of new autoimmune conditions in patients who were already diagnosed with an autoimmune disease at the time of vaccination. These new-onset diseases were distinct from the patients’ original autoimmune conditions and most study authors remained cautious about their conclusions. For example, Bleve et al. (2022) reported the case of a 61-year-old woman with a history of hypothyroidism who, several days after receiving her second dose of the Pfizer vaccine, developed what authors referred to as “autoimmune diabetes” (Bleve et al., 2022, p. 1). However, the authors emphasized that although the diabetes appeared after vaccination, causality could not be confirmed.

Similarly, several studies explicitly stated that while their case reports contributed to the growing body of literature on potential autoimmune sequelae of COVID-19 vaccination, the small sample sizes and the lack of mechanistic studies limited their ability to draw firm conclusions regarding causality (e.g., (Faruk et al., 2022; Manta et al., 2022)). No reports were identified describing the development of new autoimmune diseases post-vaccination in patients originally diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, Graves’ disease, or Hashimoto’s thyroiditis - only in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, or type 1 diabetes mellitus.

3.5. Vaccination Associated with New Autoimmune Disorders in Persons Without Prior History of Autoimmunity

About one fourth of the articles (27/109; 24.8%) reported cases of new autoimmune disease following COVID-19 vaccination in previously healthy individuals or at least without a prior history of autoimmune disorders. These reports included a variety of autoimmune disorders, such as Graves’ disease, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and type 1 diabetes mellitus, as well as other conditions not within our study focus - Guillain-Barré syndrome, vasculitis, and autoimmune hepatitis. While these reports described a temporal relationship between vaccination and new-onset autoimmune symptoms, the authors generally noted that causality could not be confirmed given their study design.

3.5.1. Graves’ Disease

A total of seven case reports documented new-onset Graves’ disease following COVID-19 vaccination. The vaccines implicated included Pfizer, Moderna, and AstraZeneca. For example, Shih & Wang (2022) reported a case of Graves’ disease diagnosed four weeks after administration of the AstraZeneca vaccine (Shih & Wang, 2022). The patient, a previously healthy individual, developed symptoms including palpitations, heat intolerance, and weight loss, which led to testing that confirmed the diagnosis of Graves’ disease. di Filippo et al. (2023) reported that 20 (of 64, or 31%) of new onset Graves’ disease patients seen at their clinic had their first episode within four weeks of a COVID-19 vaccination (di Filippo et al., 2023). Mechanisms suggested were Asia triggered by adjuvant or excipients such as polyethylene glycols or polysorbate 80 oil-in-water emulsions, and cross-reactive antigen molecular mimicry between proteins with high amino acid sequence similarity, such as the vaccine-induced viral spike proteins and thyroid peroxidase antigens (di Filippo et al., 2023).

Chee et al. (2022) published a correspondence reporting six cases of post-vaccination Graves’ disease, although detailed clinical information was limited (Chee et al., 2022). Taieb et al. (2022) documented a case of Graves’ disease after the second dose of the Pfizer vaccine in a 43-year-old woman with no prior autoimmune history (Taieb et al., 2022). Symptoms included palpitations, heat intolerance and weight loss, with laboratory findings confirming the diagnosis. Vera-Lastra et al. (2021) reported Graves’ disease in a previously healthy 34-year-old woman two weeks after receiving the AstraZeneca vaccine; the diagnosis was confirmed based on clinical and laboratory findings consistent with Graves’ disease (Vera-Lastra et al., 2021). Although these cases reported a temporal association between vaccination and the onset of Graves’ disease, most authors cautioned that causality could not be definitively established.

3.5.2. Hashimoto’s Thyroiditis

Lioulios et al. (2022) reported cases of new onset Grave’s disease and new onset Hashimoto’s thyroiditis within four and two months, respectively, post-vaccination with the Pfizer vaccine in patients without autoimmune disease albeit on dialysis (Lioulios et al., 2022). Subsequent to vaccination, the Graves’ disease patient also relapsed after SARS-CoV-2 infection. The authors concluded that “both natural infection and vaccination elicit a weak yet extended immune response, with a tendency to cross-reactivity to non-pathogenic antigens, thus leading to autoimmunity” (Lioulios et al., 2022, p. 5).

3.5.3. Multiple Sclerosis

Havla et al. (2022) reported a case of new onset multiple sclerosis within six days of a first dose of the Pfizer vaccine but stated that it was not possible to determine causality based on this one case (Havla et al., 2022). Toljan et al. (2022) reported five new cases of multiple sclerosis in previously healthy patients within one to five weeks of receiving mRNA COVID-19 vaccines – Pfizer in three and Moderna in two cases (Toljan et al., 2022). Cases included individuals who developed optic neuritis, sensory disturbances, motor weakness, and other demyelinating symptoms, consistent with magnetic resonance imaging confirmed multiple sclerosis.

3.5.4. Rheumatoid Arthritis

Yonezawa et al. (2022) reported a case of new-onset rheumatoid arthritis within days of the second dose of the Pfizer vaccine in a patient without other autoimmune disorders, although the patient had been diagnosed with combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema related to a 30-year history of smoking (Yonezawa et al., 2022). Watanabe et al. (2022) described a case of new-onset rheumatoid arthritis in a previously healthy individual after the second dose of the Pfizer vaccine (Watanabe et al., 2022). Singh et al. (2022) reported a case of new-onset rheumatoid arthritis within two weeks of an inactivated COVID-19 vaccine (COVAXIN) (Singh et al., 2022).

3.5.5. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Nelson et al. (2022) reported a case of severe systemic lupus erythematosus in a pediatric patient within two days of a third dose of the Pfizer vaccine (Nelson et al., 2022). The patient presented with facial and body rash, bilateral arthralgias in the shoulders, hands, and knees, progressive hair loss, pleuritic chest pain, and photophobia. Molina-Rios et al. (2023) described new-onset systemic lupus in a previously healthy patient within two weeks of the first dose of the Pfizer vaccine (Molina-Rios et al., 2023). The patient was also diagnosed with inflammatory arthralgias, dyspnea, hypoxemia, pulmonary thromboembolism, and suspected secondary antiphospholipid syndrome and required hospitalization in an Intensive Care Unit for life-threatening conditions.

Sogbe et al. (2023) reported a case of new-onset systemic lupus erythematosus with myopericarditis in a patient within one week of receiving a third dose of the Pfizer vaccine (Sogbe et al., 2023). Lemoine et al. (2022) described a case of new-onset systemic lupus erythematosus and polymyalgia rheumatica within two days of the first dose of the Pfizer vaccine, with symptoms including headache, upper and lower limb muscle weakness, stiffness, and pain (Lemoine et al., 2022). The patient required hospitalization by day seven and subsequently chose not to receive a second dose. N et al. (2022) reported new-onset systemic lupus erythematosus with acute pancreatitis and vasculitic skin rash within seven days of the first dose of the Pfizer vaccine (Nelson et al., 2022). The authors suggested that a possible mechanism for the induction of autoimmune pathophysiology could involve vaccine adjuvants triggering the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain.

Gamonal et al. (2022) reported a case of new-onset systemic lupus erythematosus in a previously healthy patient within three weeks of a second dose of the AstraZeneca vaccine (Gamonal et al., 2022). Wang et al. (2022) also reported a case of new-onset systemic lupus erythematosus with acrocyanosis within two weeks of a first dose of the AstraZeneca vaccine, suggesting a potential mechanism involving type 1 interferon and proinflammatory cytokine pathways (Wang et al., 2022a). Raviv et al. (2022) described a case of new-onset systemic lupus erythematosus in a healthy patient with no family history of autoimmune disorders, occurring within two days of a first dose of the Pfizer vaccine (Raviv et al., 2022). Symptoms were initially diagnosed as an allergic rash but worsened and evolved into psoriasiform-papulosquamous plaques on the face, neck, and arms, nonscarring hair loss across the scalp, persistent and numerous joint pains, and ultimately a diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus.

Sagy et al. (2022) reported a case series of three patients developing new-onset systemic lupus erythematosus within three days to one month after receiving the Pfizer vaccine (Sagy et al., 2022). Kim et al. (2022) described a case of lupus with multi-organ involvement after a second dose of the AstraZeneca vaccine, suggesting that vaccination triggered an autoimmune response through the stimulation of CD8+ T cells, increased cytokine production, and cross-reactivity between spike protein antibodies and various tissue antigens (Kim et al., 2022). Kreuter et al. (2022) reported a case of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus within ten days of a first dose of the Pfizer vaccine (Kreuter et al., 2022). After ruling out other triggering factors, such as recent infection, sun exposure, or new drug exposures, a diagnosis of vaccine-induced subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus was determined and treated with hydroxychloroquine and glucocorticoids, with full remission achieved within four weeks.

3.5.6. Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus

Sakurai et al. (2022) reported a case of new-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus within three days of a first dose of the Pfizer vaccine in a patient with no prior history of autoimmune disease (Sakurai et al., 2022). Tang et al. (2022) described a case of sudden and severe new-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus within five days of vaccination with the inactivated CoronaVac vaccine (Tang et al., 2022). The patient was hospitalized and treated for diabetic ketoacidosis and continued to show nearly complete loss of islet function at four-week follow-up, although no islet-associated autoantibodies were observed. Sasaki et al. (2022) reported a case of new-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus within eight days of a first dose of the Pfizer vaccine (Sasaki et al., 2022). Yano et al. (2022) described a case of new-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus and latent thyroid autoimmunity in a previously healthy patient within six weeks of the first dose of the Moderna vaccine (Yano et al., 2022). Bleve et al. (2022) reported two cases of new-onset autoimmune diabetes: one following the first dose of the AstraZeneca vaccine, and the other after the second dose of the Pfizer vaccine (Bleve et al., 2022). Sasaki et al. (2022) documented a case of new-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus within four to eight weeks of a second dose of the Moderna vaccine (Sasaki et al., 2022). Sato et al. (2022) reported a case of new-onset type 1 diabetes mellitus in a cancer patient undergoing treatment with nivolumab, an immune checkpoint inhibitor, within weeks of receiving a second dose of an mRNA-based SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (no brand was reported) (Sato et al., 2022).

3.6. Adverse Events After COVID-19 Vaccination

Most articles (101/109; 93%) documented adverse events following the administration of COVID-19 vaccines. Although the timing of these events varied among studies, adverse events were generally classified as vaccine-related if they occurred within 28 days of vaccination (So et al., 2022). The eight articles (8/109; 7%) that did not report adverse events either focused on serologic responses as their primary research question or stated that adverse events were outside the scope of their study. Half of the studies that mentioned adverse events (53/101; 52%) reported different categories of events. Articles typically classified these events as mild, moderate, or severe, and described them as either directly or indirectly related to COVID-19 vaccination. The terms “mild” and “minor” were often used interchangeably to describe events that did not require hospitalization or further medical care. These included local injection site pain, fatigue, chills, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, rashes, fever, myalgia, chest pain, and headaches. Such reactions were frequently described as self-limiting and resolving within a few days. Mild side effects were the most reported.

When severe adverse events were reported, they included anaphylaxis, marked dyspnea, throat closure, severe rashes, and hospitalization. Some authors further categorized adverse events as short-term or long-term (Briggs et al., 2022) and/or as local or systemic. However, most articles did not provide clear definitions for these categories. In the case of adverse events associated with specific autoimmune diseases, the studies often applied their own disease-specific grading systems. Overall, while most articles reported that patients experienced mild and “manageable” side effects, some documented instances of severe reactions post-vaccination that required medical intervention, including hospitalization (e.g., (Bellinvia e t al., 2022; Briggs et al., 2022; Kreuter et al., 2022; Molina-Rios et al., 2023; Sugimoto et al., 2022; Q. Tang et al., 2022). Despite these occurrences, most authors concluded that the majority of adverse events were mild and transient and that the vaccines demonstrated a generally favorable safety profile.

3.7. Efficacy of COVID-19 Vaccination

Just over half of the articles included in this review (57/109; 52.3%) did not explicitly address the efficacy of COVID-19 vaccination. Among the 52 articles (47.7%) that did address vaccine efficacy, most cited as supporting evidence external sources - clinical trials, regulatory approvals, or global health agency statements. Among the articles that mentioned efficacy (38/52; 73%), most echoed the general assertion that COVID-19 vaccines are effective at reducing disease severity, hospitalization, and mortality, even as some of them acknowledged that immunocompromised and autoimmune patients were often excluded from initial vaccine trials, leaving gaps in efficacy data for these populations. Still, assertions about efficacy were mostly presented as background statements without direct supporting data. For example, Lemoine et al. (2022) referenced the United States Food and Drug Administration’s approval of the Pfizer vaccine (Lemoine et al., 2022), citing a Phase 3 trial that reported 95% efficacy in preventing infection (Polack et al., 2020) – a trial that excluded the population of focus of the authors’ study. Similarly, Aydoğan et al. (2022) reported that the two-dose regimen was expected to provide 95% protection against the virus (Aydoğan et al., 2022), again referencing clinical trial data (Polack et al., 2020) rather than evidence from their own study population.

Several authors made broad claims about the role of vaccination in mitigating COVID-19 transmission, disease severity, and mortality, while their own findings challenged these claims. For example, Chaudhary et al. (2022) stated that mass vaccination campaigns were highly effective and safe in controlling the pandemic, upon reporting four cases of Graves disease following viral vector COVID-19 vaccination and without providing specific supporting data (Chaudhary et al., 2022). Similarly, Ghadiri et al. (2022) observed an “absence of vaccine efficacy in controlling severe COVID-19” in a relatively healthy patient population (younger individuals, lower Body Mass Index, nonsmokers, no comorbidities), while still concluding that they “expected more infection over time in the absence of vaccination” and that “vaccines could curb the incidence” (Ghadiri et al., 2022, p. 4). This apparent inconsistency – observing lack of efficacy while simultaneously asserting efficacy unsupported by their own findings - underscores a pattern identified in several studies.

In studies that involved specific populations such as pediatric patients, autoimmune patients, or immuno-compromised individuals, several authors explicitly noted the absence of robust efficacy data. Scaramuzza et al. (2022), for example, conducted a survey of fully vaccinated Italian pediatric diabetologists regarding their vaccine recommendations (Scaramuzza et al., 2022). While advocating for prioritizing high-risk children for vaccination, they acknowledged that “data on COVID-19 vaccine efficacy and antibody responses in children will no doubt emerge over the coming months” (Scaramuzza et al., 2022, pp. 1110–1111), reflecting the absence of conclusive efficacy data at the time of their study. Similarly, some studies suggested that inactivated COVID-19 vaccines might offer comparable protective effects with potentially fewer adverse events, particularly among patients with autoimmune disorders (Assawasaksakul et al., 2022; So et al., 2022). However, these conclusions were typically drawn from small observational cohorts or immunogenicity data rather than from clinical outcomes measuring efficacy against infection or disease severity.

Likewise, Manta et al. (2022) reflected a commonly held position among many authors by suggesting that despite limited direct data in vulnerable groups, the potential benefits of vaccination were expected to outweigh risks due to the assumed higher susceptibility to severe infection of these populations (Manta et al., 2022). A particularly illustrative example of the tension between observed adverse outcomes and assumed efficacy was a study by Toljan et al. (2022), suggesting that sudden neurological impairments occurring shortly after mRNA vaccination could potentially indicate the onset of multiple sclerosis, while reaffirming vaccine efficacy (Toljan et al., 2022). Indeed, the lack of consistent, population-specific benefit-risk assessment was a notable feature across most of the studies that engaged with efficacy claims. Lastly, some articles asserted that, for example, the COVID-vaccinations “facilitated the societal return to normalcy during the COVID-19 pandemic” (Flannery et al., 2021, p. 4), without offering specific evidence or arguments to support their claims.

3.8. Authors’ Perspectives on COVID-19 Vaccination for Patients with Autoimmune Disorders

Concerning authors’ perspectives on the appropriateness of COVID-19 vaccination for patients with autoimmune disorders, most authors expressed a positive stance towards vaccination vis-à-vis it risks (65/109; 59.6%), about a third maintained a cautious viewpoint (38/109; 34.9%), only a few (6/109; 5.5%) presented a negative assessment of the balance of risks versus benefits, and no author explicitly advised against it. As such, most authors (60/109; 55%) concluded that COVID-19 vaccines should still be administered to patients with autoimmune disorders, even as they acknowledged the need to remain vigilant about what they described as “rare” side effects.

For example, Brès et al. (2022) asserted that vaccination of this population should proceed “while being aware of potential rare side effects, with minimal final consequences” (Brès et al., 2022, p. 264) Barbhaiya et al. (2022) stated that vaccines are “important” for patients with lupus, while acknowledging that information on vaccine tolerance in this population remained “unclear” (Barbhaiya et al., 2022, p. 1619). Finally, Ganakumar et al. (2022) noted the existence of “rare” but potentially severe adverse events, such as glycemia worsening among diabetic patients, but concluded that this “does not take away from the fact that vaccines are the single most important preventive measure in curbing the spread of COVID-19 and the resultant healthcare costs, and all efforts must be made to continue vaccination” (Ganakumar et al., 2022, p. 4) - although the authors did not offer any evidence to support this assertion.

4. Discussion

This scoping review synthesized evidence from 109 published studies regarding associations between COVID-19 vaccination and autoimmune disorders. Our analysis revealed substantial patterns of reported association suggesting: (1) worsening of existing autoimmune conditions upon COVID vaccination in over half of the studies; (2) triggering of new autoimmune disorders in already affected individuals; and (3) new-onset autoimmune disorders in previously healthy individuals in about one-quarter of the studies. While most studies were case reports, case series, or small cohort studies not designed to establish causality, the consistency of observed patterns across different study designs and autoimmune conditions supports the case for considering these associations in clinical decision-making and public health policy. Although such designs limit causal inference, they remain essential for early signal detection, particularly in populations excluded from large-scale trials, among whom adverse events may otherwise go unrecognized.

Adverse events following vaccination – injection site pain, fatigue, and headaches - were reported in over 90% of studies and were most commonly described as mild and self-limiting. However, a notable subset of studies reported serious adverse events such as anaphylaxis, marked dyspnea, hospitalization, and autoimmune-mediated reactions. It should be noted that across these studies, authors consistently acknowledged the difficulty of confirming causality, and emphasized the need for larger, population-based investigations to evaluate whether vaccination may elevate relapse risk or whether these episodes reflected coincidental timing within a population subgroup already at risk for disease activity. Studies also described the development of new autoimmune disorders post-vaccination in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and type 1 diabetes, although not among patients with Graves’ disease, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, and multiple sclerosis. While the absence of such reports may indicate that patients in those studies do not experience adverse effects postvaccination, they may also reflect underreporting, or the methodological limitations of study designs themselves.

Our findings about associations between autoimmune disorders and COVID vaccination are not unexpected or rare: the biological mechanisms explaining them have been long recognized in immunology, and the existence of plausible pathways is well established in the scientific literature - molecular mimicry, including in the context of spike protein vaccines (Trougakos et al., 2022), bystander activation (Shoenfeld, 2009); epitope spreading (Shoenfeld, 2009); adjuvant-related immune stimulation via vaccine components such as lipid nanoparticles (used in mRNA vaccines) or viral vectors (Chen et al., 2022); and interferon pathway dysregulation, implicated in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus and other autoimmune disorders (Wang et al., 2022b). While the understanding of these mechanisms in the context of COVID-19 vaccination is evolving, the consistency of the reported autoimmune-related adverse events across multiple studies provides clinical support for these pathways. Further, recent studies have explicitly noted the role of mRNA vaccines as possible triggers of autoimmune disorders (Frasca et al., 2023; Mahroum & Shoenfeld, 2022; Vojdani & Kharrazian, 2020).

Importantly, while study authors made assertions about the efficacy and benefits of COVID vaccination for the population of interest, they generally offered little supporting evidence. For example, close to half of the studies discussed vaccine effectiveness, but most referred to prior trials, regulatory approvals, or general public health statements rather than their own empirical data, or data relevant to patients with autoimmune disorders, therefore limiting researchers’ capacity to properly assess the balance of risks and benefits of COVID-19 vaccination among these patients. Perspectives on the appropriateness of vaccination for this patient population were divided between positive endorsement, cautious support, and in very rare instances, negative assessment regarding the balance of risks and benefits, although no study recommended explicitly against vaccination given the risk of exacerbation of autoimmune processes.

Another notable pattern was the inconsistency among the applications of standards of evidence to causal claims regarding benefits versus those regarding risks of COVID vaccination. For example, Widhani et al.’s (2023) systematic review and meta-analysis reported that patients with autoimmune diseases experience “significantly more COVID-19 infections […], lower total antibody titers, IgG seroconversion, and neutralizing antibodies after inactivated COVID-19 vaccination, [and more] systemic adverse events after a first dose of inactivated vaccination compared with healthy controls” – clearly acknowledging the negative effects of vaccination in this population, followed however by the assertion that a “second dose of vaccine was […] found to be important”, in light of its association with “improved antibody titers and seroconversion” (Widhani et al., 2023). While the authors recommended that given the observed negative effects patients should consult their providers “before taking a vaccine” – taking for granted that they will – they still concluded that “the administration of third doses of COVID-19 vaccines should be considered due to improved seroprotection in these patients” (emphasis added) (Widhani et al., 2023). Similarly, efficacy and safety claims were frequently reiterated without new population-specific analyses (Hromić-Jahjefendić et al., 2023). In sum, in the absence of clear benefit data - particularly for groups excluded from key trials - the continued reliance on generalized claims substitutes assumption for evidence, and the burden of proof remains unmet. This epistemic asymmetry in vaccine research deserves further investigation.

This review has limitations. First, it included primarily case reports, case series, and small observational studies, which are limited in their ability to establish causality or provide population-level risk estimates. However, these designs remain essential for early signal detection, particularly in populations excluded from large-scale trials where adverse events may otherwise go unrecognized or adverse events that may not be captured in larger trials or surveillance systems. Excluding such studies on methodological grounds would risk overlooking the very signals that these studies are capable of capturing, and this review sought to document. Second, following standard scoping review methodology, we did not conduct a formal quality assessment or risk-of-bias analysis of the included studies. While quality appraisal is typically a feature of systematic reviews and meta-analyses, scoping reviews prioritize breadth of coverage and identification of evidence gaps rather than weighting or pooling of data. In this context, excluding studies based on methodological quality would have eliminated much of the currently available evidence on potential autoimmune sequelae of COVID-19 vaccination, given that these reports often emerge through case-level documentation.

Third, our search strategy was limited to English-language publications accessible through the authors’ academic affiliations and focused on studies published in 2022. These restrictions may have excluded relevant earlier or non-English reports, and this should be considered when interpreting our findings. We note, however, that over 80% of study authors were affiliated with institutions not in English speaking countries, so most likely their first language was not English, nor were their study populations located in the English-speaking world. Lastly, we limited our review to peer-reviewed articles or articles available through preprint servers, excluding potentially informative sources, such as pharmacovigilance databases. However, as described earlier these limitations reflect deliberate methodological choices aligned with our research objectives and resource limitations.

5. Conclusions

While we recognize that our study design does not provide definitive answers regarding causality or incidence, it documents substantial patterns of reported associations of autoimmune disorders following COVID-19 vaccination, in patients with and without prior autoimmunity. It also highlights patterns of evidentiary and epistemic asymmetry between vaccine effectiveness and safety claims that remain largely unaddressed. We also believe that the absence of perfect evidence does not warrant the dismissal of credible signals of potential harm. By providing a comprehensive synthesis of the current state of knowledge, this review has aimed to inform clinical practice, highlight areas of uncertainty, and identify priorities for future research, practice and policy concerning the complex relationship between COVID-19 vaccines and autoimmune disorders.

Author Contributions

Claudia Chaufan (CC): Conceptualization; Methodology; Project Administration; Supervision; Writing – Original Draft; Writing – Review & Editing; Investigation; Data Curation; Formal Analysis. Laurie Manwell (LM): Methodology; Investigation; Data Curation; Formal Analysis; Writing – Review & Editing; Resources. Camila Heredia (CH): Methodology; Data Curation; Formal Analysis; Investigation Jennifer McDonald (JM): Methodology; Data Curation; Formal Analysis; Investigation. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by a New Frontiers in Research Fund (NFRF) 2022 Special Call, NFRFR-2022-00305.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Conflicts of Interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. Funders and professional / academic affiliations have played no role in the conception, conduct, or decision to conduct this research or submit it for publication.

References

- Al-Midfai, Y. , Kujundzic, W., Uppal, S., Oakes, D., & Giezy, S. (2022). Acute Multiple Sclerosis Exacerbation After Vaccination With the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 Vaccine: Novel Presentation and First Documented Case Report. Cureus. [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. [CrossRef]

- Assawasaksakul, T., Lertussavavivat, T., Sathitratanacheewin, S., Oudomying, N., Vichaiwattana, P., Wanlapakorn, N., Poovorawan, Y., Avihingsanon, Y., Assawasaksakul, N., & Kittanamongkolchai, W. (2022). Comparison of immunogenicity and safety of inactivated, adenovirus-vectored and heterologous adenovirus-vectored/mRNA vaccines in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis: A prospective cohort study (p. 2022.04.22.22274158). medRxiv. [CrossRef]

- Aydoğan, B. İ., Ünlütürk, U., & Cesur, M. (2022). Type 1 diabetes mellitus following SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination. Endocrine, 78(1), 42–46. [CrossRef]

- Barbhaiya, M., Levine, J. M., Siegel, C. H., Bykerk, V. P., Jannat-Khah, D., & Mandl, L. A. (2022). Adverse events and disease flares after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clinical Rheumatology, 41(5), 1619–1622. [CrossRef]

- Bellinvia, A., Aprea, M. G., Portaccio, E., Pastò, L., Razzolini, L., Fonderico, M., Addazio, I., Betti, M., & Amato, M. P. (2022). Hypogammaglobulinemia is associated with reduced antibody response after anti-SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in MS patients treated with antiCD20 therapies. Neurological Sciences, 43(10), 5783–5794. [CrossRef]

- Bleve, E., Venditti, V., Lenzi, A., Morano, S., & Filardi, T. (2022). COVID-19 vaccine and autoimmune diabetes in adults: Report of two cases. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation, 45(6), 1269–1270. [CrossRef]

- Brès, F., Joyeux, M.-A., Delemer, B., Vitellius, G., & Barraud, S. (2022). Three cases of thyroiditis after COVID-19 RNA-vaccine. Annales d’Endocrinologie, 83(4), 262–264. [CrossRef]

- Briggs, F. B. S., Mateen, F. J., Schmidt, H., Currie, K. M., Siefers, H. M., Crouthamel, S., Bebo, B. F., Fiol, J., Racke, M. K., O’Connor, K. C., Kolaczkowski, L. G., Klein, P., Loud, S., & McBurney, R. N. (2022). COVID-19 Vaccination Reactogenicity in Persons With Multiple Sclerosis. Neurology Neuroimmunology & Neuroinflammation, 9(1), e1104. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S., Dogra, V., & Walia, R. (2022). Four cases of Graves’ disease following viral vector severe acute respiratory syndrome corona virus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) vaccine. Endocrine Journal, 69(12), 1431–1435. [CrossRef]

- Chaufan, C., Manwell, L., Heredia, C., McDonald, J., Chaufan, C., Manwell, L., Heredia, C., & McDonald, J. (2023). COVID-19 vaccines and autoimmune disorders: A scoping review protocol. AIMS Medical Science, 10(4), Article medsci-10-04-025. [CrossRef]

- Chee, Y. J., Liew, H., Hoi, W. H., Lee, Y., Lim, B., Chin, H. X., Lai, R. T. R., Koh, Y., Tham, M., Seow, C. J., Quek, Z. H., Chen, A. W., Quek, T. P. L., Tan, A. W. K., & Dalan, R. (2022). SARS-CoV-2 mRNA Vaccination and Graves’ Disease: A Report of 12 Cases and Review of the Literature. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 107(6), e2324–e2330. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Xu, Z., Wang, P., Li, X., Shuai, Z., Ye, D., & Pan, H. (2022). New-onset autoimmune phenomena post-COVID-19 vaccination. Immunology, 165(4), 386–401. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A. D., & Shoenfeld, Y. (1996). Vaccine-induced autoimmunity. Journal of Autoimmunity, 9(6), 699–703. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, G. S., Bynum, M. L. K., & Somers, E. C. (2009). Recent insights in the epidemiology of autoimmune diseases: Improved prevalence estimates and understanding of clustering of diseases. Journal of Autoimmunity, 33(3–4), 197–207. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, G. S., & Stroehla, B. C. (2003). The epidemiology of autoimmune diseases. Autoimmunity Reviews, 2(3), 119–125. [CrossRef]

- Coyle, P. K., Gocke, A., Vignos, M., & Newsome, S. D. (2021). Vaccine Considerations for Multiple Sclerosis in the COVID-19 Era. Advances in Therapy, 38(7), 3550–3588. [CrossRef]

- di Filippo, L., Castellino, L., Allora, A., Frara, S., Lanzi, R., Perticone, F., Valsecchi, F., Vassallo, A., Giubbini, R., Rosen, C. J., & Giustina, A. (2023). Distinct Clinical Features of Post-COVID-19 Vaccination Early-onset Graves’ Disease. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 108(1), 107–113. [CrossRef]

- Dreyer-Alster, S., Menascu, S., Mandel, M., Shirbint, E., Magalashvili, D., Dolev, M., Flechter, S., Givon, U., Guber, D., Stern, Y., Miron, S., Polliack, M., Falb, R., Sonis, P., Gurevich, M., & Achiron, A. (2022). COVID-19 vaccination in patients with multiple sclerosis: Safety and humoral efficacy of the third booster dose. Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 434, 120155. [CrossRef]

- Etemadifar, M., Nouri, H., Salari, M., & Sedaghat, N. (2022). Detection of anti-NMDA receptor antibodies following BBIBP-CorV COVID-19 vaccination in a rituximab-treated person with multiple sclerosis presenting with manifestations of an acute relapse. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 18(1), 2033540. [CrossRef]

- Faruk, T. Ö., Koseoglu, M., & Rabia, K. E. (2022). Varicella zoster virus infection due to Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA COVID-19 vaccine and sinovac vaccine in two relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients during fingolimod therapy. Neuroimmunology Reports, 2, 100078. [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, M. C., Moghadas, S. M., Pandey, A., & Galvani, A. P. (2022, December 13). Two Years of U.S. COVID-19 Vaccines Have Prevented Millions of Hospitalizations and Deaths. The Commonwealth Fund. [CrossRef]

- Flannery, P., Yang, I., Keyvani, M., & Sakoulas, G. (2021). Acute Psychosis Due to Anti-N-Methyl D-Aspartate Receptor Encephalitis Following COVID-19 Vaccination: A Case Report. Frontiers in Neurology, 12, 764197. [CrossRef]

- Frasca, L., Ocone, G., & Palazzo, R. (2023). Safety of COVID-19 Vaccines in Patients with Autoimmune Diseases, in Patients with Cardiac Issues, and in the Healthy Population. Pathogens, 12(2), 233. [CrossRef]

- Gad, A. H. E., Ahmed, S. M., Garadah, M. Y. A., & Dahshan, A. (2022). Multiple sclerosis patients’ response to COVID-19 pandemic and vaccination in Egypt. The Egyptian Journal of Neurology, Psychiatry and Neurosurgery, 58(1), 131. [CrossRef]

- Galanis, P., Vraka, I., Katsiroumpa, A., Siskou, O., Konstantakopoulou, O., Katsoulas, T., Mariolis-Sapsakos, T., & Kaitelidou, D. (2022). First COVID-19 Booster Dose in the General Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Willingness and Its Predictors. Vaccines, 10(7), 1097. [CrossRef]

- Gamonal, S. B. L., Marques, N. C. V., Pereira, H. M. B., & Gamonal, A. C. C. (2022). New-onset systemic lupus erythematosus after ChAdOX1 nCoV-19 and alopecia areata after BNT162b2 vaccination against SARS-CoV-2. Dermatologic Therapy, 35(9), e15677. [CrossRef]

- Ganakumar, V., Jethwani, P., Roy, A., Shukla, R., Mittal, M., & Garg, M. K. (2022). Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) in type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) temporally related to COVID-19 vaccination. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews, 16(1), 102371. [CrossRef]

- Ghadiri, F., Sahraian, M. A., Azimi, A., & Moghadasi, A. N. (2022). The study of COVID-19 infection following vaccination in patients with multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders, 57. [CrossRef]

- Giossi, R., Consonni, A., Clerici, V. T., Zito, A., Rigoni, E., Antozzi, C., Brambilla, L., Crisafulli, S. G., Bellino, A., Frangiamore, R., Bonanno, S., Vanoli, F., Ciusani, E., Corsini, E., Andreetta, F., Baggi, F., Tramacere, I., Mantegazza, R., Conte, A., … Confalonieri, P. (2022). Anti-Spike IgG in multiple sclerosis patients after BNT162b2 vaccine: An exploratory case-control study in Italy. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders, 58. [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, L. E., Baker, B., Perricone, C., & Shoenfeld, Y. (2015). Vaccines, adjuvants and autoimmunity. Pharmacological Research, 100, 190–209. [CrossRef]

- Guo, M., Liu, X., Chen, X., & Li, Q. (2023). Insights into new-onset autoimmune diseases after COVID-19 vaccination. Autoimmunity Reviews, 22(7), 103340. [CrossRef]

- Havla, J., Schultz, Y., Zimmermann, H., Hohlfeld, R., Danek, A., & Kümpfel, T. (2022). First manifestation of multiple sclerosis after immunization with the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. Journal of Neurology, 269(1), 55–58. [CrossRef]

- Hromić-Jahjefendić, A., Barh, D., Uversky, V., Aljabali, A. A., Tambuwala, M. M., Alzahrani, K. J., Alzahrani, F. M., Alshammeri, S., & Lundstrom, K. (2023). Can COVID-19 Vaccines Induce Premature Non-Communicable Diseases: Where Are We Heading to? Vaccines, 11(2), 208. [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, D. L., Gange, S. J., Rose, N. R., & Graham, N. M. (1997). Epidemiology and estimated population burden of selected autoimmune diseases in the United States. Clinical Immunology and Immunopathology, 84(3), 223–243. [CrossRef]

- Jara, L. J., Vera-Lastra, O., Mahroum, N., Pineda, C., & Shoenfeld, Y. (2022). Autoimmune post-COVID vaccine syndromes: Does the spectrum of autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome expand? Clinical Rheumatology, 41(5), 1603–1609. [CrossRef]

- Kataria, S., Rogers, S., Bilal, U., Baktashi, H., & Singh, R. (2022). Multiple Sclerosis Relapse Following COVID-19 Vaccination: A Case Report and Literature Review. Cureus. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. J., Jung, M., Lim, B. J., & Han, S. H. (2022). New-onset class III lupus nephritis with multi-organ involvement after COVID-19 vaccination. Kidney International, 101(4), 826–828. [CrossRef]

- Kirwan, P. D., Charlett, A., Birrell, P., Elgohari, S., Hope, R., Mandal, S., De Angelis, D., & Presanis, A. M. (2022). Trends in COVID-19 hospital outcomes in England before and after vaccine introduction, a cohort study. Nature Communications, 13(1), 4834. [CrossRef]

- Kreuter, A., Licciardi-Fernandez, M. J., Burmann, S. -N., Burkert, B., Oellig, F., & Michalowitz, A. -L. (2022). Induction and exacerbation of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus following mRNA-based or adenoviral vector-based SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Clinical and Experimental Dermatology, 47(1), 161–163. [CrossRef]

- Lemoine, C., Padilla, C., Krampe, N., Doerfler, S., Morgenlander, A., Thiel, B., & Aggarwal, R. (2022). Systemic lupus erythematous after Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine: A case report. Clinical Rheumatology, 41(5), 1597–1601. [CrossRef]

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science: IS, 5, 69. [CrossRef]

- Lim, E., Kim, Y. H., Jeong, N.-Y., Kim, S.-H., Won, H., Bae, J.-S., Choi, N.-K., & COVID-19 Vaccine Safety Committee (CoVaSC). (2025). The association between acute transverse myelitis and COVID-19 vaccination in Korea: Self-controlled case series study. European Journal of Neurology, 32(1), e70020. [CrossRef]

- Lioulios, G., Tsouchnikas, I., Dimitriadis, C., Giamalis, P., Pella, E., Christodoulou, M., Stangou, M., & Papagianni, A. (2022). Two Cases of Autoimmune Thyroid Disorders after COVID Vaccination in Dialysis Patients. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(19), Article 19. [CrossRef]

- Lohmann, L., Glaser, F., Möddel, G., Lünemann, J. D., Wiendl, H., & Klotz, L. (2022). Severe disease exacerbation after mRNA COVID-19 vaccination unmasks suspected multiple sclerosis as neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder: A case report. BMC Neurology, 22(1), 185. [CrossRef]

- Mahroum, N., Lavine, N., Ohayon, A., Seida, R., Alwani, A., Alrais, M., Zoubi, M., & Bragazzi, N. L. (2022). COVID-19 Vaccination and the Rate of Immune and Autoimmune Adverse Events Following Immunization: Insights From a Narrative Literature Review. Frontiers in Immunology, 13, 872683. [CrossRef]

- Mahroum, N., & Shoenfeld, Y. (2022). COVID-19 vaccination can occasionally trigger autoimmune phenomena, probably via inducing age-associated B cells. International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases, 25(1), 5–6. [CrossRef]

- Manta, R., Martin, C., Muls, V., & Poppe, K. G. (2022). New-onset Graves’ disease following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: A case report. [CrossRef]

- McDonald, I., Murray, S. M., Reynolds, C. J., Altmann, D. M., & Boyton, R. J. (2021). Comparative systematic review and meta-analysis of reactogenicity, immunogenicity and efficacy of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2. Npj Vaccines, 6(1), 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Mele, A. A., Ogbuagu, H., Parag, S., Pierce, B., Mele, A. A., Ogbuagu, H., Parag, S., & Pierce, B. H. (2022). A Case of Multiple Sclerosis Uncovered Following Moderna SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination. Cureus, 14. [CrossRef]

- Molina-Rios, S., Rojas-Martinez, R., Estévez-Ramirez, G. M., & Medina, Y. F. (2023). Systemic lupus erythematosus and antiphospholipid syndrome after COVID-19 vaccination. A case report. Modern Rheumatology Case Reports, 7(1), 43–46. [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z., Stern, C., Aromataris, E., Lockwood, C., & Jordan, Z. (2018). What kind of systematic review should I conduct? A proposed typology and guidance for systematic reviewers in the medical and health sciences. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 5. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, H., Nagasawa, Y., Kobayashi, H., Tsukamoto, M., Takayama, T., & Kitamura, N. (2022). Successful Treatment of SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination-related Activation of Rheumatoid Arthritis with Positive Findings for Epstein-Barr Virus. Internal Medicine, 61(13), 2073–2076. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, M. C., Rytting, H., Greenbaum, L. A., & Goldberg, B. (2022). Presentation of SLE after COVID vaccination in a pediatric patient. BMC Rheumatology, 6(1), 81. [CrossRef]

- Patrizio, A., Ferrari, S. M., Antonelli, A., & Fallahi, P. (2022). Worsening of Graves’ ophthalmopathy after SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination. Autoimmunity Reviews, 21(7), 103096. [CrossRef]

- Polack, F. P., Thomas, S. J., Kitchin, N., Absalon, J., Gurtman, A., Lockhart, S., Perez, J. L., Marc, G. P., Moreira, E. D., Zerbini, C., Bailey, R., Swanson, K. A., Roychoudhury, S., Koury, K., Li, P., Kalina, W. V., Cooper, D., Frenck, R. W., Hammitt, L. L., … Gruber, W. C. (2020). Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. New England Journal of Medicine, 383(27), 2603–2615. [CrossRef]

- Prof Peter Hotez MD PhD [@PeterHotez]. (2025, February 4). Here’s where the 3.2 million lives saved comes from https://t.co/A7Z1Vc2VL2 [Tweet]. Twitter. https://x.com/PeterHotez/status/1886573301977284968.

- Raviv, Y., Betesh-Abay, B., Valdman-Grinshpoun, Y., Boehm-Cohen, L., Kassirer, M., & Sagy, I. (2022). First Presentation of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in a 24-Year-Old Male following mRNA COVID-19 Vaccine. Case Reports in Rheumatology, 2022(1), 9698138. [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri, R. M., Giovanellla, L., & Campennì, A. (2022). SARS-CoV-2 vaccine may trigger thyroid autoimmunity: Real-life experience and review of the literature. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation, 45(12), 2283–2289. [CrossRef]

- Sagy, I., Zeller, L., Raviv, Y., Porges, T., Bieber, A., & Abu-Shakra, M. (2022). New-onset systemic lupus erythematosus following BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine: A case series and literature review. Rheumatology International, 42(12), 2261–2266. [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, K., Narita, D., Saito, N., Ueno, T., Sato, R., Niitsuma, S., Takahashi, K., & Arihara, Z. (2022). Type 1 diabetes mellitus following COVID-19 RNA-based vaccine. Journal of Diabetes Investigation, 13(7), 1290–1292. [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, H., Itoh, A., Watanabe, Y., Nakajima, Y., Saisho, Y., Irie, J., Meguro, S., & Itoh, H. (2022). Newly developed type 1 diabetes after coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination: A case report. Journal of Diabetes Investigation, 13(6), 1105–1108. [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, K., Morioka, T., Okada, N., Natsuki, Y., Kakutani, Y., Ochi, A., Yamazaki, Y., Shoji, T., Ohmura, T., & Emoto, M. (2022). New-onset fulminant type 1 diabetes after severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 vaccination: A case report. Journal of Diabetes Investigation, 13(7), 1286–1289. [CrossRef]

- Sato, T., Kodama, S., Kaneko, K., Imai, J., & Katagiri, H. (2022). Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus Associated with Nivolumab after Second SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination, Japan. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 28(7), 1518–1520. [CrossRef]

- Scaramuzza, A. E., Cherubini, V., Schiaffini, R., Rabbone, I., The Diabetes Study Group of the Italian Society for Pediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes, Gallo, F., Fichera, G., Arnaldi, C., Bonfanti, R., Lombardo, F., De Marco, R., Pascarella, F., Tornese, G., Bobbio, A., Suprani, T., Minuto, N., Franceschi, R., Piccinno, E., Mozzillo, E., … Cavalli, C. (2022). A nationwide survey of Italian pediatric diabetologists about COVID-19 vaccination in children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Acta Diabetologica, 59(8), 1109–1111. [CrossRef]

- Shea, B. J., Reeves, B. C., Wells, G., Thuku, M., Hamel, C., Moran, J., Moher, D., Tugwell, P., Welch, V., Kristjansson, E., & Henry, D. A. (2017). AMSTAR 2: A critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ, 358, j400. [CrossRef]

- Shih, S.-R., & Wang, C.-Y. (2022). SARS-CoV-2 vaccination related hyperthyroidism of Graves’ disease. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association, 121(9), 1881–1882. [CrossRef]

- Shoenfeld, Y. (2009). Infections, vaccines and autoimmunity. Lupus, 18(13), 1127–1128. [CrossRef]

- Shoenfeld, Y., & Agmon-Levin, N. (2011). ’ASIA’—Autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome induced by adjuvants. Journal of Autoimmunity, 36(1), 4–8. [CrossRef]

- Shoenfeld, Y., & Aron-Maor, A. (2000). Vaccination and Autoimmunity—‘vaccinosis’: A Dangerous Liaison? Journal of Autoimmunity, 14(1), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Singh, R., Kaur, U., Singh, A., & Chakrabarti, S. S. (2022). New onset rheumatoid arthritis with refractory hyper-eosinophilia associated with inactivated COVID-19 vaccin. [CrossRef]

- So, H., Li, T., Chan, V., Tam, L.-S., & Chan, P. K. (2022). Immunogenicity and safety of inactivated and mRNA COVID-19 vaccines in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Therapeutic Advances in Musculoskeletal Disease, 14, 1759720X221089586. [CrossRef]

- Sogbe, M., Blanco-Di Matteo, A., Di Frisco, I. M., Bastidas, J. F., Salterain, N., & Gavira, J. J. (2023). Systemic lupus erythematosus myocarditis after COVID-19 vaccination. Reumatología Clínica, 19(2), 114–116. [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, T., Yorishima, A., Oka, N., Masuda, S., Yoshida, Y., & Hirata, S. (2022). Exacerbation of systemic lupus erythematosus after receiving mRNA-1273-based coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine. The Journal of Dermatology, 49(6), e199–e200. [CrossRef]

- Taieb, A., Sawsen, N., Asma, B. A., Ghada, S., Hamza, E., Yosra, H., Amel, M., Molka, C., Maha, K., & Koussay, A. (2022). A rare case of grave’s disease after SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: Is it an adjuvant effect? European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences, 26(7), 2627–2630. [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q., Li, F., Tian, J., Kang, J., & He, J. (2022). Attitudes towards and safety of the SARS-CoV-2 inactivated vaccines in 188 patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: A post-vaccination cross-sectional survey. Clinical and Experimental Medicine, 23(2), 457–463. [CrossRef]

- Tang, X., He, B., Liu, Z., Zhou, Z., & Li, X. (2022). Fulminant type 1 diabetes after COVID-19 vaccination. Diabetes & Metabolism, 48(2), 101324. [CrossRef]

- Toljan, K., Amin, M., Kunchok, A., & Ontaneda, D. (2022). New diagnosis of multiple sclerosis in the setting of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine exposure. Journal of Neuroimmunology, 362, 577785. [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. [CrossRef]

- Trougakos, I. P., Terpos, E., Alexopoulos, H., Politou, M., Paraskevis, D., Scorilas, A., Kastritis, E., Andreakos, E., & Dimopoulos, M. A. (2022). Adverse effects of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines: The spike hypothesis. Trends in Molecular Medicine, 28(7), 542–554. [CrossRef]

- Vera-Lastra, O., Ordinola Navarro, A., Cruz Domiguez, M. P., Medina, G., Sánchez Valadez, T. I., & Jara, L. J. (2021). Two cases of Graves’ disease following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: An autoimmune/inflammatory syndrome induced by adjuvants. Thyroid®, 31(9), 1436–1439. [CrossRef]

- Vojdani, A., & Kharrazian, D. (2020). Potential antigenic cross-reactivity between SARS-CoV-2 and human tissue with a possible link to an increase in autoimmune diseases. Clinical Immunology (Orlando, Fla.), 217, 108480. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Sun, Y., & Lan, C. E. (2022a). Systemic lupus erythematosus with acrocyanosis after AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccination. The Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences, 38(12), 1230–1231. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Sun, Y., & Lan, C. E. (2022b). Systemic lupus erythematosus with acrocyanosis after AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccination. The Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences, 38(12), 1230–1231. [CrossRef]

- Watad, A., Sharif, K., & Shoenfeld, Y. (2017). The ASIA syndrome: Basic concepts. Mediterranean Journal of Rheumatology, 28(2), 64–69. [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, T., Minaga, K., Hara, A., Yoshikawa, T., Kamata, K., & Kudo, M. (2022). Case Report: New-Onset Rheumatoid Arthritis Following COVID-19 Vaccination. Frontiers in Immunology, 13. [CrossRef]

- Widhani, A., Hasibuan, A. S., Rismawati, R., Maria, S., Koesnoe, S., Hermanadi, M. I., Ophinni, Y., Yamada, C., Harimurti, K., Sari, A. N. L., Yunihastuti, E., & Djauzi, S. (2023). Efficacy, Immunogenicity, and Safety of COVID-19 Vaccines in Patients with Autoimmune Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vaccines, 11(9), 1456. [CrossRef]

- Yakou, F., Saburi, M., Hirose, A., Akaoka, H., Hirota, Y., Kobayashi, T., Awane, N., Asahi, N., Amagawa, T., Ozawa, S., Ohno, A., & Matsushita, T. (2022). A Case Series of Ketoacidosis After Coronavirus Disease 2019 Vaccination in Patients With Type 1 Diabetes. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 13, 840580. [CrossRef]

- Yano, M., Morioka, T., Natsuki, Y., Sasaki, K., Kakutani, Y., Ochi, A., Yamazaki, Y., Shoji, T., & Emoto, M. (2022). New-onset Type 1 Diabetes after COVID-19 mRNA Vaccination. Internal Medicine, 61(8), 1197–1200. [CrossRef]

- Yonezawa, H., Ohmura, S., Ohkubo, Y., & Miyamoto, T. (2022). New-onset Seropositive Rheumatoid Arthritis Following COVID-19 Vaccination in a Patient with Seronegative Status. Internal Medicine, 61(22), 3449–3452. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T., Shen, J., Zhu, Y., Tian, X., Wen, G., Wei, Y., Xu, B., Fu, C., Xie, Z., Xi, Y., Li, Z., Peng, J., Wu, Y., Tang, X., Wan, C., Pan, L., Li, Z., & Qin, D. (2022). Immunogenicity of Inactivated SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Case Series. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 875558. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).