Submitted:

09 June 2025

Posted:

10 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

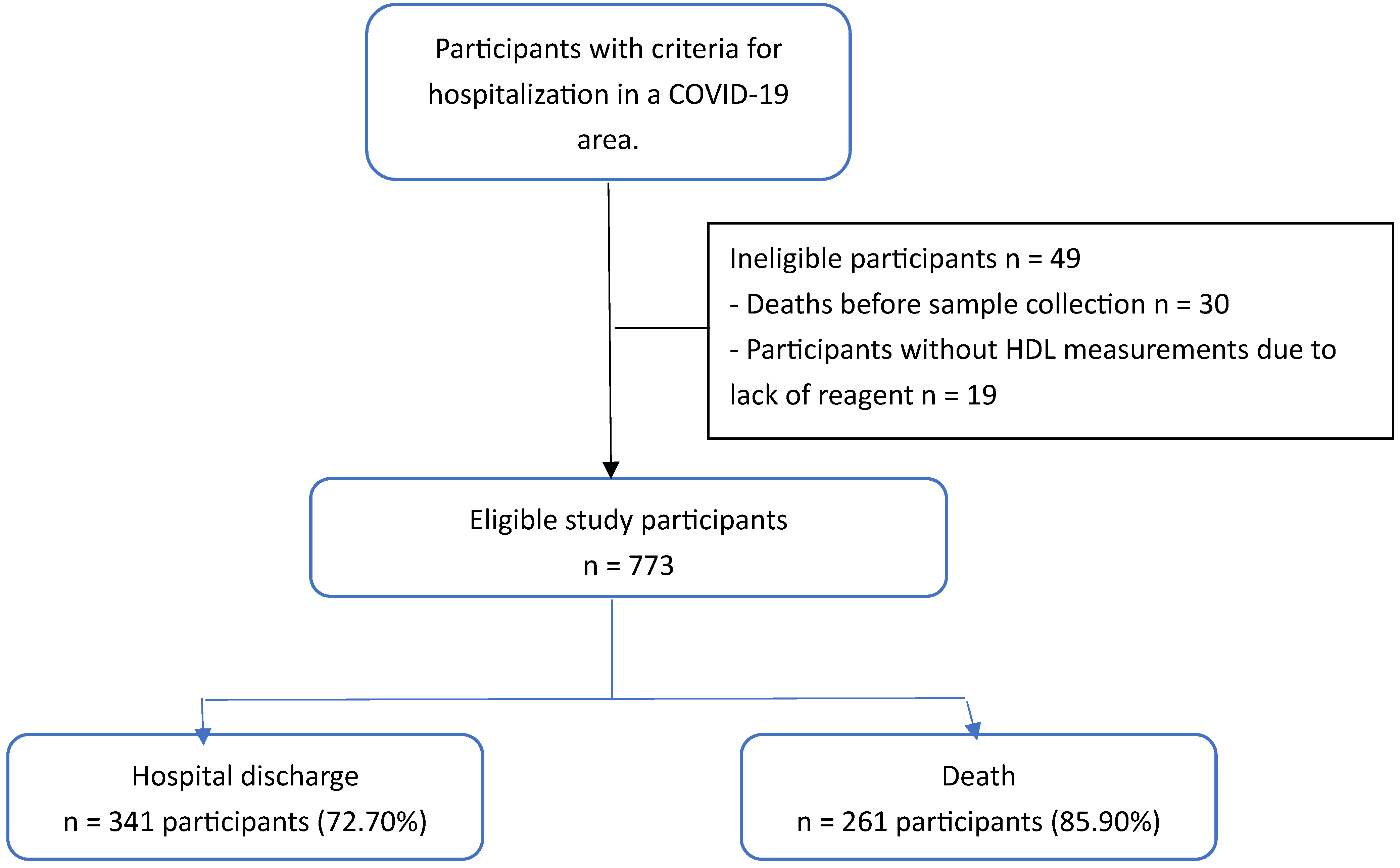

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.2. Non-Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Exclusion Criteria:

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.4.1. Univariate Analysis

2.4.2. Bivariate Analysis

2.4.3. Multivariate Analysis

2.4.4. Bias Control

3. Results

3.1. Discharge Home

3.2. Deaths

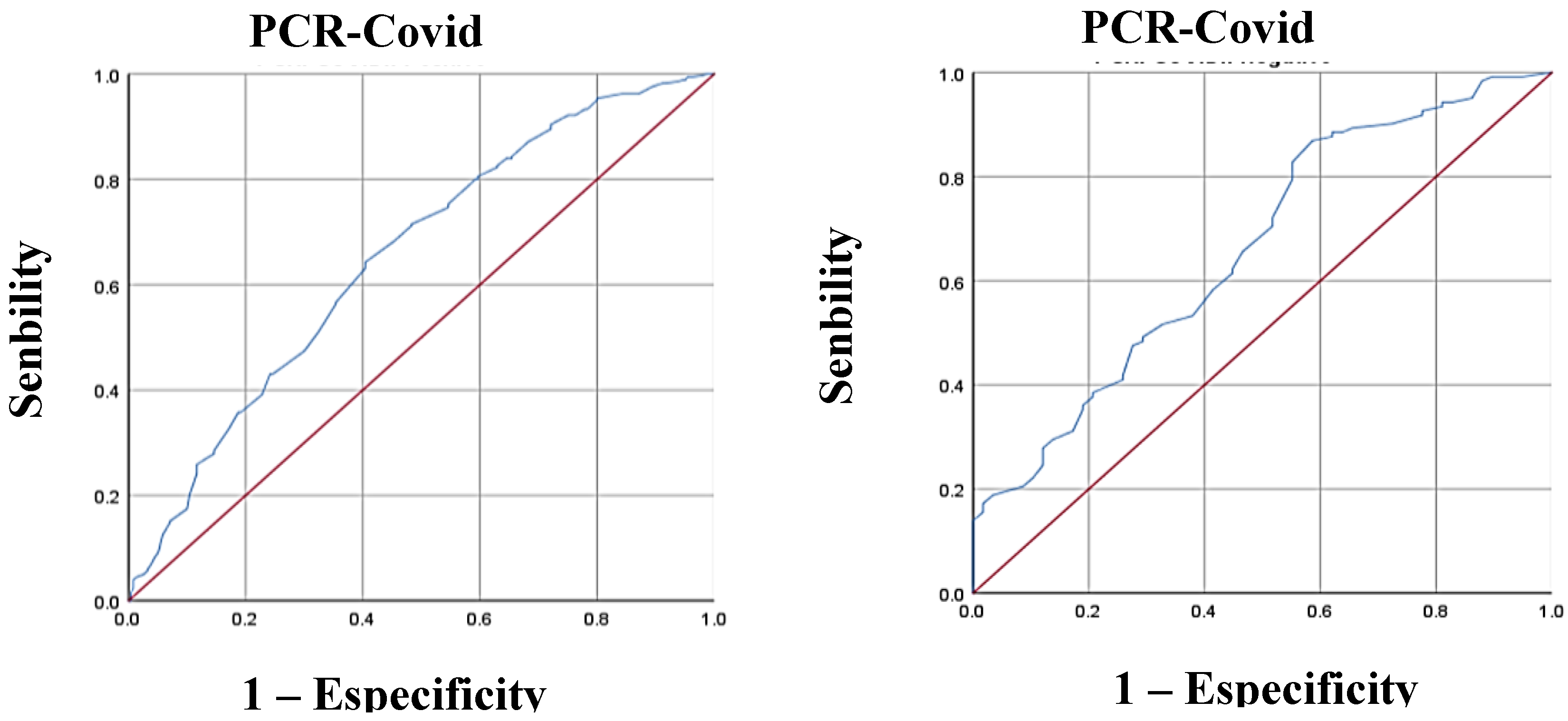

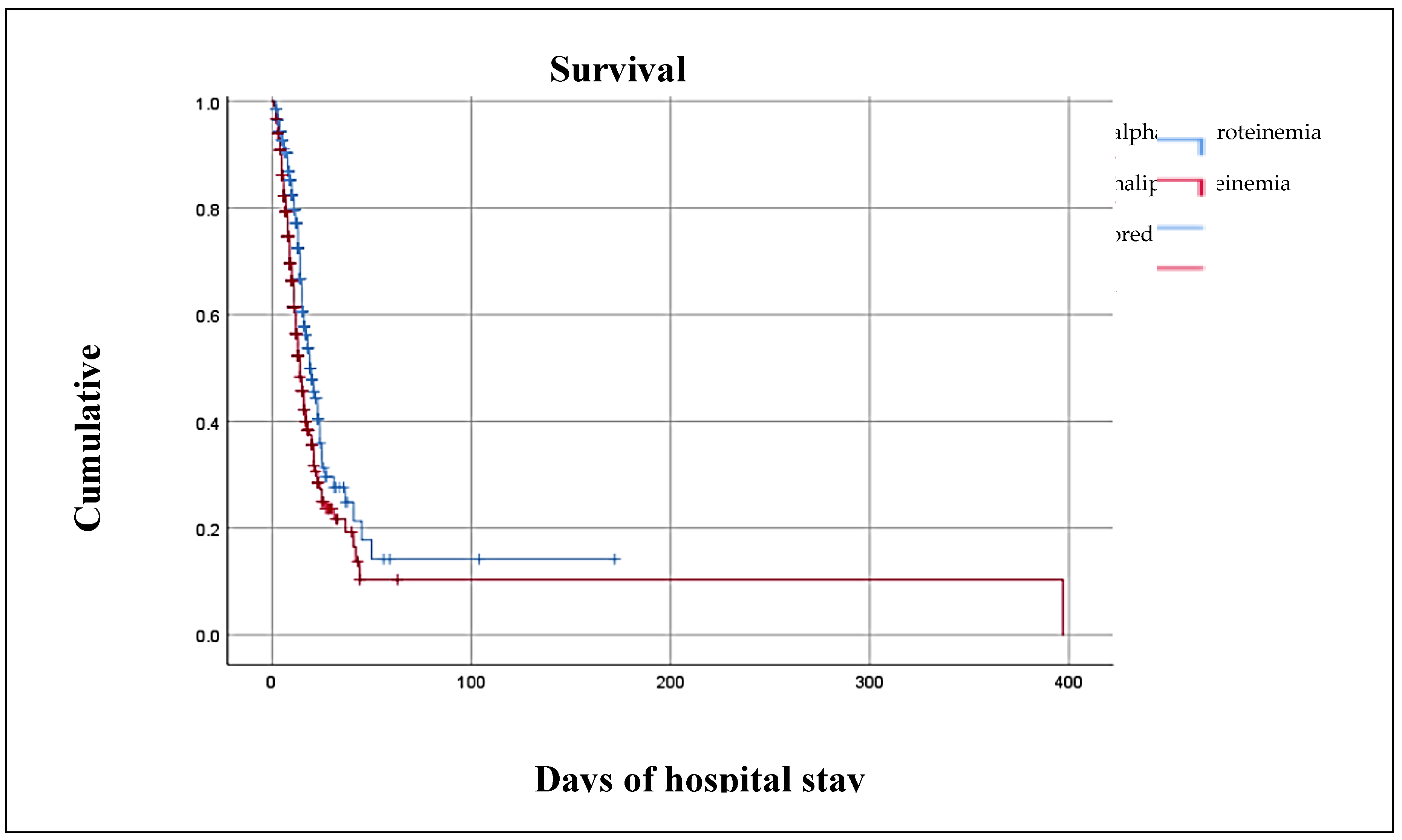

3.3. HDL Cholesterol and Outcome

3.4. Multivariate Regression Analysis of HDL-C and Outcome

3.5. Other Findings

4. Figures, Tables and Schemes

4. Discussion

4.1. Hypoalphalipoproteinemia

4.2. SARS-CoV 2 Infection and Lipid Alterations

- SARS-CoV-2 could damage liver function by reducing LDL-C biosynthesis.

- Serum transaminase levels show a moderate increase, which could indicate mild liver inflammation secondary to the presence of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, interleukin-6 (IL-6), and interleukin 1β (IL-1β), which modulate lipid metabolism.

- Lipids are vulnerable to degradation by free radicals, whose levels are elevated in viral infections.

- There is an alteration in vascular permeability, causing the leakage of cholesterol molecules into tissues such as the alveolar spaces to form exudates.

- Swab analysis shows elevated protein (>2.9 g/dL) and cholesterol (>45 mg/dL) levels due to increased vascular permeability.

5. Conclusions

Institutional Ethics Committee Statement

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

| CDC | Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) |

| ACE | Angiotensin 2 receptor |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| IL-6 | Interleukin 6 |

| NFKB | Necrosis factor kappa-betta |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor α |

| IL-1β | interleukin 1β (IL-1β) |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| HDL-c | High-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| LDL-c | Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

References

- Groups at Higher Risk for Severe Illness. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). [Online]; 2020. Accessed June 5, 2020. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/groups-at-higher-risk.html.

- Peng Y MKGH. Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes of 112 Cardiovascular Disease Patients Infected by COVID-19. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2020; 48(6): p. 450-455.

- Suárez V, Suárez M, Oros S. Epidemiology of COVID-19 in Mexico: from February 27th to April 30th, 2020. Revista Clínica Española. 2020; X(X).

- Epidemiologia DGd. Covid-19 Mexico. [On-line]; 2020. Accessed June 6, 2020. Available at: http://coronavirus.gob.mx/datos/.

- Orioli L, Hermans M, Thissen J. COVID-19 in diabetic patients: Related risks and specifics of management. Ann Endocrinol. 2020; 81(2-3): p. 101109. [CrossRef]

- Wei X, Zeng W, Su J. Hypolipidemia is associated with the severity of COVID-19. J Clin Lipidol. 2020; X(X): p. 1-8.

- Petrakis D, Margină D, Tsarouhas K. Obesity a risk factor for increased COVID 19 prevalence, severity and lethality (Review). Mol Med Rep. 2020; 22(X): p. 9-19.

- Guzik T, Mohiddin S, Dimarco A. COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system: implications for risk assessment, diagnosis, and treatment options. Cardiovasc Res. 2020; X(X): p. 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Wei, X., Zeng, W., Su, J., Wan, H., Yu, X., Cao, X., Tan, W., & Wang, H. (2020). Hypolipidemia is associated with the severity of COVID-19. Journal of Clinical Lipidology, 14(3), 297–304. [CrossRef]

- Cleeman, J. I. (2001). Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (adult treatment panel III). Journal of the American Medical Association, 285(19), 2486–2497. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, T. O. (2007). Cardiac syndrome X versus metabolic syndrome X. International Journal of Cardiology, 119(2), 137–138. [CrossRef]

- Escobedo de la Peña J, Pérez R, Schargrodsky H, Champagne B. Prevalence of dyslipidemias in Mexico City and its association with other cardiovascular risk factors. Results of the CARMELA study. Medical Gazette of Mexico. 2014; 150: p. 128-36.

- Zhao Q, Peng F, Wei H. Serum high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels as a prognostic indicator in patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 2012; 110(3): p. 433-439. [CrossRef]

- Nofer J, Van der Giet M, Tölle M. J Clin Invest. 2004; 113(4).

- Petrilli C JSYJRH. Factors associated with hospitalization and critical illness among 4103 patients with Covid-19 disease in New York City. BMJ. 2020; 369: p. 1-15.

- Wei, X., Zeng, W., Su, J., Wan, H., Yu, X., Cao, X., Tan, W., & Wang, H. (2020). Hypolipidemia is associated with the severity of COVID-19. Journal of Clinical Lipidology, 14(3), 297. [CrossRef]

- Funderburg, N. T., & Mehta, N. N. (2016). Lipid Abnormalities and Inflammation in HIV Inflection. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 13(4), 218–225. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, D. M., Chamberlain, D. W., Poutanen, S. M., Low, D. E., Asa, S. L., & Butany, J. (2005). Pulmonary pathology of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Toronto. Modern Pathology, 18(1), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Genest, J., Bard, J. M., Fruchart, J. C., Ordovas, J. M., & Schaefer, E. J. (1993). Familial hypoalphalipoproteinemia in premature coronary artery disease. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, 13(12), 1728–1737. [CrossRef]

- Lopez D MMSHRABLEG. Diagnostic criteria for hypoalphalipoproteinemia and cut-off point associated with cardiovascular protection in a Mexican mestizo population. Med Clin. 2012; 138(13): p. 551-556.

- Khirfan G, Tejwani V, Wang X. Plasma levels of high density lipoprotein cholesterol and outcomes in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. PLoS One. 2018; 13(5): p. 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Jonas K KG. HDL Cholesterol as a Marker of Disease Severity and Prognosis in Patients with Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Int J Mol Sci. 2019; 20(14): p. 1-14.

- Zhou Y FBZX. Pathogenic T cell and Inflammatory monoctes incite storm in severe COVID-19 patients. Natl Sci Rev. 2020.

- Merad M, Martin J. Pathological inflammation in patients with COVID-19: a key role for monocytes and macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020; 20(6): p. 355-362. [CrossRef]

- Tian, S., Hu, W., Niu, L., Liu, H., Xu, H., & Xiao, S. Y. (2020). Pulmonary Pathology of Early-Phase 2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pneumonia in Two Patients With Lung Cancer. Journal of Thoracic Oncology, 15(5), 700–704. [CrossRef]

| Variables |

Hospital discharge n = 469 |

Death n = 304 |

p |

|

Age, years 1§ Sex Male 1≠ Female 1≠ Weight, kg § Body Mass Index (kg/m2) 1§ Underweight 1ɷ Normal weight 1 ɷ Overweight 1 ɷ Grade 1 obesity 1ɷ Grade 2 obesity 1ɷ • Grade 3 obesity 1ɷ |

56.00 (18.00 – 90.00) 275.00 (58.60) 194.00 (41.60) 75.00 (39.00 – 160.00) 27.73 (17.15 – 54.69) 2.00(4.00) 99.00 (21.10) 221.00 (47.10) 100.00 (21.30) 27.00 (5.80) 20.00 (4.30) |

62.55 (20.00-97.00) 195.00 (64.10) 109.00 (35.90) 74.00 (40.00 – 120.00) 27.68 (14.88 – 46.05) 2.00 (0.70) 72.00 (23.70) 130.00 (42.80) 74.00 (24.30) 21.00 (6.90) 5.00 (1.60) |

0.000* 0.125 0.572 0.448 0.000* |

| Comorbilities | |||

|

Diabetes Type 1 1≠ Type 21≠ High blood pressure 1≠ Heart disease1 ≠ Autoimmune diseases1 ≠ Neoplasms1 ≠ Hematological diseases1 ≠ Liver disease 1 ≠ Kidney disease1 ≠ Hypothyroidism 1 ≠ Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) 1≠ |

2.00 (0.40) 127.00 (27.10) 213.00 (45.40) 31.00 (6.60) 11.00 (2.30) 8.00 (1.70) 17.00 (3.60) 9.00 (1.90) 47.00 (1.00.) 17.00 (3.60) 14.00 (3.00) |

1.00 (0.30) 64.00 (21.10) 106.00 (34.90) 6.00 (2.00) 2.00 (0.70) 4.00 (1.30) 4.00 (1.30) 9.00 (3.00) 18.00 (5.90) 11.0 (3.60) 12.00 (3.90) |

0.162 0.595 0.004* 0.003* 0.075 0.668 0.617 0.524 0.045* 0.996 0.469 |

| Laboratory | |||

|

Glucose (mmol/L) 1§ Creatinine (μmol/L) 1§ Total cholesterol (mmol/L) 1§ High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C)(mmol/L)1§ Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) (mmol/L) 1§ Triglycerides (mg/dl) 1§ TC/HDL 1§ TG/HDL 1§ LDL/HDL 1§ Non-LDL cholesterol/HDL 1§ Total bilirubin (μmol/L)1§ Direct bilirubin )( μmol/L)1§ Indirect bilirubin )(mmol/L)1§ Alanine transaminase (ALT) (U/L) 1§ Aspartate transaminase (AST) (U/L) 1§ Lactic acid dehydrogenase (DHL) (U/L) 1§ Total protein (g/L) 1§ Albumin (g/L) 1§ |

6.44 (1.72 – 48.95) 76.91 (30.94 – 2679.46) 39.00 (4.16 – 77.48) 0.75 (0.13 – 1.61) 2.20 (0.28 – 9.54) 1.76 (0.47 – 10.6) 5.00 (0.05-36.20) 5.087 (0.00 – 111.00) 93.50 (0.55 – 248.54) 4.00 (0.77 – 35.20) 10.26 (1.71 – 1282.5) 5.13 (5.13 – 307.8) 5.13 (5.13 – 171.00) 34.00 (0.40 – 770.00) 36.00 (0.30 – 612.00) 374.00 (4.9 – 17057.00) 36.00 (15.00 – 105.00) 61.00 (20.0 – 120.00) |

7.88 (0.28 – 47.12) 87.52 (38.9 – 2485.52) 36.01 (12.48 – 127.14) 0.62 (0.16 – 1.71) 69.70 (1.81 – 11.97) 2.24 (0.54 – 22.98) 5.72 (0.34-51.02) 8.30 (0.34 – 118.58) 99.93 (0.34 – 118.58) 4.70 (0.79 – 50.02) 10.26 (1.71 – 369.36) 6.84 (1.71 – 251.37) 5.13 (5.13 – 121.41) 39.00 (6.00 – 721.00) 45.00 (6.00 – 4544.00) 491.00 (13.00 – 31468.00) 33.00 (10.00 – 92.00) 60.00 (20.00 – 80.00) |

0.000* 0.000* 0.001* 0.000* 0.000* 0.000* 0.000* 0.000* 0.027* 0.000* 0.327 0.025* 0.749 0.267 0.000* 0.000* 0.000* 0.006* |

| PCR Test | |||

| Positive1≠ | 347.00 (74.00) | 246.00 (80.90) | 0.033* |

| National Early Warning Score 2 (NEWS 2) | |||

|

Low 1ɷ Intermediate 1ɷ High 1ɷ |

206.00 (43.90) 164.00 (35.00) 99.00 (35.00) |

109.00 (35.90) 117.00 (38.50) 78.00 (25.70) |

0.025* |

| Assisted mechanical ventilation | |||

| Yes 1≠ | 37.00 (7.90) | 231.00 (76.00) | 0.000* |

| Days of hospital stay1§ | 10.00 (16.00 – 172.00) | 10.00 (12.00 – 397) | 0.252 |

| Sedation | |||

|

Propofol monotherapy Yes 1≠ No 1≠ Combined propofol Yes 1≠ No 1≠ |

4.00 (10.80) 33.00 (89.20) 27.00 (73.00) 10.00 (27.00) |

54.00 (23.40) 177.00 (76.60) 215.00 (93.10) 16.00 (6.90) |

0.085 0.000* |

| Hypoalphalipoproteinemia | |||

| Yes 1≠ Men 1≠ • Women1≠ |

397.00 (89.76) 268.00 (67.50) 129.00 (32.50)) |

304.00 (96.05) 195.00 (64.15) 109.00 (35.85)) |

0.000* 0.001* 0.000* |

| c-HDL <0.91 (mmol/L) | |||

| Yes1≠ | 330.00 (70.40) | 256.00 (84.20) | 0.000* |

| c-HDL (mmol/L) Percentiles | |||

| < 0.54 (mmol/L) 1ɷ 0.54 – 0.70 (mmol/L) 1ɷ 0.70 – 0.88 (mmol/L) 1ɷ ≥ 0.88 (mmol/L) 1ɷ |

81.00 (17.30) 98.00 (20.90) 132.00 (28.10) 158.00 (33.70) |

116.00 (38.2) 63.00 (20.70) 70.00 (23.00) 55.00 (18.10) |

0.000* |

| c-HDL(mmol/L) ROC curve | |||

| < 0.64 (mmol/L) 1 ≥ 0.64 (mmol/L) 1 |

124.00 (26.40) 345.00 (73.60) |

140.00 (46.10) 164.00 (53.90) |

0.000* |

| Variable | p | OR neto | IC 95% | R2 | P | OR ajustado | IC 95% |

|

Age, years 1§ Body Mass Index (kg/m2) 1§ Underweight 1ɷ Normal weight 1 ɷ Overweight 1 ɷ Grade 1 obesity 1ɷ Grade 2 obesity 1ɷ Grade 3 obesity 1ɷ |

0.000* 0.154 0.425 0.425 0.000* 0.000* 0.000* |

1.022 0.40 1.16 0.86 4.89 0.37 0.38 |

1.01 – 0.03 0.36 – 0.43 0.82 – 1.64 0.61 – 1.22 3.07 – 7.78 0.34 – 0.41 0.35 – 0.41 |

-0.72 -2.611 Reference -0.226 -0.385 -0.959 -0.684 |

0.000* 0.048* 0.767 0.606 0.214 0.437 |

0.93 0.07 0.80 0.69 0.38 0.51 |

0.91 – 0.95 0.01 – 0.98 0.18 – 3.57 0.16 – 2.93 0.08 – 1.74 0.09 – 2.83 |

| Comorbilities | |||||||

|

High blood pressure 1≠ Type 2 diabetes1≠ Heart disease1≠ |

0.003* 0.042* 0.003* |

1.18 1.40 0.69 |

1.05 – 1.32 1.21 – 1.64 0.46 – 1.02 |

1.262 20.710 0.777 |

0.000* 0.015* 0.262 |

3.53 2.39 2.18 |

2-04 – 6.11 1.19 – 4.81 0.56 – 8.46 |

| Laboratory | |||||||

|

Glucose (mmol/L) 1§ Creatinine (μmol/L) 1§ Total cholesterol (mmol/L) 1§ High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C)(mmol/L)1§ Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) (mmol/L) 1§ Triglycerides (mg/dl) 1§ TC/HDL 1§ TG/HDL 1§ LDL/HDL 1§ Non-LDL cholesterol/HDL 1§ Aspartate transaminase (AST) (U/L) 1§ Lactic acid dehydrogenase (DHL) (U/L) 1§ |

0.000* 0.029* 0.005* 0.000* 0.000* 0.000* 0.000* 0.000* 0.031* 0.000* 0.048* 0.046* |

1.00 1.01 0.98 0.99 0.99 1.00 1.41 0.97 1.00 0.77 1.00 1.30 |

0.99 – 1.00 1.04 – 1.11 0.97 – 0.99 0.96 – 1.02 0.99 – 1.02 1.00 – 1.00 0.97 – 2.06 0.95 – 1.00 1.00 – 1.00 0.54 – 1.00 1.00 – 1.00 1.00 – 1.00 |

-0.003 -0.157 0.042 0.005 0.002 -0.002 -1.065 0.032 -0.008 0.928 0.000 0.000 |

0.042 0.000* 0.053 0.875 0.784 0.092 0.197 0.156 0.001* 0.259 0.936 0.490 |

0.99 0.85 1.04 1.00 1.00 0.99 0.35 1.03 0.99 2.53 1.00 1.00 |

0.99 – 1.00 0.78 – 0.94 1.00 – 1.002 0.94 – 1.07 0.99 – 1.02 0.99 – 1.00 0.07-1.74 0.99 – 1.08 0.98 – 0.99 0.50 – 12.70 0.99 – 1.00 1.00 – 1.00 |

| PCR Test | |||||||

| Positive1≠ | 0.033* | 1.46 | 1.03 – 2.09 | 0.096 | 0.737 | 1.10 | 0.63 – 1.93 |

| National Early Warning Score 2 (NEWS 2) | |||||||

|

Low 1ɷ Intermediate 1ɷ High 1ɷ |

0.111 0.052* 0.550 |

Ref. 1.33 1.42 |

– 1.76 1.02 – 1.98 |

Reference 0.580 0.382 |

0.227 0.085 0.258 |

1.79 1.47 |

0.92 – 3-46 0.76 – 2.84 |

| Assisted mechanical ventilation | |||||||

| Yes 1≠ | 0.000* | 5.96 | 4.80 – 7.41 | -3.839 | 0.000* | 0.02 | 0.01 – 0.04 |

| Hypoalphalipoproteinemia | |||||||

| Hombres Mujeres |

0.001* 0.000* |

1.29 2.05 |

1.14 – 1.47 1.60 – 2.61 |

-0.513 0.875 |

0.401 0.043* |

0.60 2.40 |

0.18 – 1.98 1.03 – 5.61 |

| c-HDL(mmol/L) ROC curve – Model 2 | |||||||

| < 0.64 (mmol/L)1 ɣ ≥ 0.64 (mmol/L)1 ɣ |

0.000* 0.000* |

2.38 0.61 |

1.75 – 3.22 0.51 – 0.72 |

-0.515 -0.515 |

0.184 0.000* |

0.60 1.68 |

0.28 – 1.28 0.78 – 3.58 |

| c-HDL (mmol/L) Percentiles - Model 3 | |||||||

| < 0.54 (mmol/L) 1ɷ 0.54 – 0.70 (mmol/L) 1ɷ 0.70 – 0.88 (mmol/L) 1ɷ ≥ 0.88 (mmol/L) 1ɷ |

0.000* 1.000 0.131 0.000* |

2.95 0.99 0.76 0.44 |

2.12 – 4.12 0.69 – 1.41 0.55 – 1.07 0.31 – 0.62 |

1.402 0.989 1.246 Reference |

0.262 0.306 0.111 0.009 |

4.06 2.69 3.47 |

0.35 – 47.00 0.40 – 17.90 0.75 – 16.07 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).