1. Introduction

The classical no-slip boundary condition—assuming that a fluid in contact with a solid surface adopts the same velocity as that surface—has long served as a cornerstone of macroscopic hydrodynamics. However, mounting evidence from nanotribology and nanofluidics challenges the generality of this assumption, revealing conditions under which fluids can exhibit slip at solid boundaries. Notably, these deviations arise not only due to confinement effects and surface structure, but also as a result of molecular-level interactions that alter the effective boundary conditions [1,2].

One striking manifestation of such phenomena is the emergence of slip behavior reminiscent of dry friction effects, where interfacial shear stresses can surpass a critical threshold and initiate sliding between the fluid and the solid [1,3]. This suggests that fluids under certain conditions can behave analogously to amorphous solids, allowing the definition of a “static friction threshold” at the liquid-solid interface. Particularly on atomically smooth surfaces such as mica or graphene, the principles underlying structural superlubricity in solids may likewise govern fluid slip behavior [4,5].

Another intriguing aspect is the concept of liquid superlubricity, wherein van der Waals repulsion—previously demonstrated between solid bodies—may reduce or even eliminate friction at the liquid-solid interface [6]. Theoretical frameworks, dating back to Lifshitz and collaborators, provide conditions under which repulsive van der Waals forces emerge [7]. When such repulsion occurs, it effectively maintains a nanoscopic separation between surfaces, weakening molecular adhesion and facilitating near-frictionless sliding [8,9].

Further complexity arises in non-ideal interfaces, where partial adhesion and tangential slip can generate negative interfacial pressures, potentially inducing cavitation or interfacial fracture [10,11]. These instabilities may propagate in ways analogous to crack dynamics in solids, thereby stabilizing slip once it is initiated. Such behavior suggests deeper analogies between tribological phenomena in liquids and those traditionally associated with solid mechanics [12].

Despite increasing recognition of these effects, systematic studies of the conditions that govern slip onset, frictional resistance, and the interplay with surface properties remain scarce. This paper aims to fill this gap through a comprehensive investigation combining molecular dynamics simulations, non-equilibrium thermodynamics, and mesoscale modeling. In doing so, we seek to uncover the key parameters controlling interfacial slip in fluid-solid contacts and to establish theoretical foundations for tailoring hydrodynamic boundary conditions in both nano- and macroscale systems. As part of this aim, in the present paper we describe a simple numerical model capable of simulating various phase states and solid-fluid interactions. Its application to investigation of boundary conditions between solids and fluids will be carried out in a follow-up paper.

2. Choice of Numerical Method

Modeling complex fluid motion—particularly turbulent flow—is typically computationally intensive when using traditional continuum mechanics, which assumes a smooth velocity field. In this study, we adopt a computational approach based on a discrete representation of the continuum. Our objective is to construct a robust yet simple model capable of capturing the key phenomena relevant to our investigation. Specifically, we focus on how mesoscopic and macroscopic properties—and the associated geometrical patterns—emerge from underlying dynamic processes.

A suitable framework for this analysis is provided by discretizing the continuum and simulating the dynamics of discrete automata (meso-particles) that represent it. For instance, the model proposed in [13], which is based on discrete particle dynamics with repulsive interactions, can reproduce a wide spectrum of mass and energy transport regimes—from solid-like to gas-like behavior. This approach allows control over the correlation radius between particles, a parameter that effectively tunes the material’s response in terms of flow and stress.

Traditional molecular dynamics, which models atomic or molecular motion directly, remains limited in accessible spatial and temporal scales, which limits its feasibility for studies such as this. Instead, we use “particles” representing a system of mesoscopic entities whose collective motion captures the essential system behavior. Notably, this modeling strategy has recently enabled significant advances in understanding structural lubricity in both soft and hard matter systems [13].

Various discretization methods—such as the method of movable cellular automata [14], smoothed particle hydrodynamics, and the discrete automata method [15] - have shown both qualitative and, in many cases, quantitative agreement with experimental results. Our work also follows this approach, with an emphasis on computational efficiency and on extracting qualitative insights from numerical simulations, along with facilitation of intuitive visualization across a broad range of scenarios and time frames. To this end, we adopted the isotropic movable automata technique, which features a combination of short-range repulsive and weak long-range attractive forces between particles.

The form of the interparticle potential ensures the presence of a well-defined minimum and an associated equilibrium configuration. As a result, the system spontaneously forms compact structures without the need for explicit boundary constraints. Even when the average particle density is below the threshold for continuous space-filling, there is a natural tendency for particles to aggregate. It has been shown [13] that when the kinetic energy density Ekin >> , where is a stiffness parameter associated with the magnitude of the attractive interaction between particles i and j, the system behaves like a gas of nearly free-flying particles. In the opposite limit case, Ekin<<, a crystal lattice is formed spontaneously.

In the gaseous state, the system exhibits isotropy on average. In the solid state, the lattice assumes hexagonal symmetry, assuming an isotropic interaction potential. In both limits, the system demonstrates regular dynamic behavior. However, the transition between these states—due to differing symmetries—passes through a disordered intermediate state. In the presence of dissipation, this state behaves as a viscous fluid.

Thus, this minimalist model is capable of efficiently capturing the full range of aggregate states—solid, liquid, and gas. It offers a versatile and practical framework for studying systems undergoing transitions between different physical states under varying conditions, including internal and external friction.

3. General Basic Model

The model structure in the present paper generally follows analogous models already used in large number of previous works [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26]. The model is therefore only introduced briefly, with a focus on the main changes which are applied in this paper. In the movable automata approach, one deals with a system of

movable objects (effective particles). As usual, they are represented by the vector radius

, the momentum

, and the interaction potential

corresponding to the following Hamiltonian (see for example course of theoretical physics Landau and Lifshitz, 1976 [25]):

The main idea used in our previous papers was to simulate a liquid (gas) using a simple interaction potential defined by a pair of Gauss potentials:

where

and

define the magnitude, while

and

are the radii of attraction and repulsion, and relation between the parameters is:

,

. The equations of motion have the following form:

is the velocity of the

i-th particle, are the forces

will be explained further. All the unknown or stochastic influences should be incorporated according to fluctuation-dissipation theorem with effective temperature

. As usual, it is simulated by random

-correlated Langevin [26], having the correlators:

where

and the diffusion coefficient is proportional to temperature

. By varying intensity of noise at fixed interactions or vice versa, the system can represent different states from gaseous to liquid and solid ones [13,14,15,16,17]. Below, we will always suppose that this relation is chosen to simulate

liquid.

There are different options to numerically simulate liquid motion between two solid interfaces. For example, in the simplest case, the liquid can be confined between two planar rigid repulsing planes: (lower plane) and (upper plane). Numerically, this can be done by means of reflecting boundary conditions with sharp repulsing potentials exponentially growing inside the boundary walls: and .

Since the system is composed of discrete, movable particles, the following computational procedure was adopted for our previous numerical experiments: Initially, a fixed number of particles were randomly distributed within a rectangular domain with sides and . To allow the system to relax, it was first brought to near-zero temperature, enabling the particles to interact and self-organize into a near-equilibrium configuration characterized by multiple domains with varying orientations. Following this initialization phase, shear flow was induced by moving the top and bottom boundaries in opposite horizontal directions. In a perfectly laminar regime, the resulting velocity profile along the vertical (ordinate) axis would be smooth and monotonic, reflecting a uniform shear across the system.

However, this behavior changes significantly when the material is partitioned into distinct domains. Initially, the structure responds elastically, with lattice nodes smoothly following the displacement of the shearing boundaries. This results in a continuous velocity gradient across the system. When the applied shear strain surpasses a critical threshold, bonds between certain neighboring particles begin to break, allowing the formation of new local configurations.

While all particles are theoretically coupled through long-range interactions, their actual dynamics are dominated by their immediate neighbors. As a result, localized regions of the lattice tend to move collectively, maintaining their internal order while shifting crystallographic planes primarily at domain boundaries.

Here, as in our previous studies, we apply Delaunay triangulation to identify the nearest neighbors and evaluate the local connection symmetry. This is particularly important for identifying defect chains (haracterized by 5-fold and 7-fold symmetry) and domain boundaries.

4. Model Modification and Evaluation

The original model described in our previous works [13,17,25,26] and others, used a maximally simple interaction potential defined by a pair of Gaussians: where parameters, and permitted to regulate the magnitude and the radii of attraction and repulsion. Generally, the magnitude relation between these parameters: , simulates the interaction of particles well enough if their repulsive core is not very important. Mathematically such potentials allowed the particles partially penetrate one into another. In the majority of cases such partial interpenetration did not affect the physical picture when the collective behavior (at mesoscopic scales) is considered. The same is true in relation to the interaction between the particles and substrates.

In many friction and shear problems the contact surface is either treated as “atomically flat”, or mesoscopically fractal, where fine structure of the interaction between the particles is not so important. However, below we will be interested in the effects of commensurability or incommensurability. With this goal in mind, we modify the model to make the interaction qualitatively closer to the Lennard-Jones potential defining a very hard central core with almost vertical potential walls and a narrow attraction belt around the core but still conserving mesoscopic size of the “particles” to use them as classical, relatively large “movable automata”.

It is important for further consideration to maintain the flexibility to study the interaction between particles, since we will consider not only interaction inside the fluid, but also interaction with the automata/particles of the upper and bottom surfaces as well. These automata are supposed to simulate objects that are qualitatively different from the internal ones. Assuming that in the equations of motion only the forces between objects are used, it is convenient to construct here, instead of the potential Eq.2, the following interaction force:

with

and

Every combination of 1/(1+exp(…)) works here as a smooth step-like (Fermi-Dirac) function with the radius equal to the sum, and the amplitude and width of the step being regulated by combination of the parameters , and . At large distances such functions work similarly to the forces caused by the Gaussians in Eq.2. However, if these amplitudes are large enough and the widths of the smoothed step-functions are narrow, these interactions ensure sharp exponential walls around the repulsing core of each particle, with well-defined, but still easily varied distance between the centersin each interacting pair.

Figure 1 illustrates the force-distance relationship between two particles of different radii. The total interaction force, shown in subplot (a), consists of two components: a strong short-range repulsion and a weaker but longer-range attraction. This attractive component forms an "adhesive belt" surrounding the nearly rigid core of each particle. Subplot (b) schematically depicts two such particles in contact, with their adhesive belts overlapping, indicated by dashed circles.

Figure 2 demonstrates the practical applicability of the interaction forces defined in Eqs. (5–7). It shows a typical instantaneous particle distribution between the upper and lower surfaces. These surfaces are covered with stationary particles (depicted in black and magenta), which move in opposite horizontal directions. The same interaction rules apply to these surface-bound particles as to the internal ones.

The internal particles in

Figure 2 are interconnected using Delaunay triangulation (thin lines), which allows for rapid identification of each particle's nearest neighbors. This triangulation is essential for characterizing the system’s structural order and its temporal evolution. For better visualization, a magnified view of the central region (highlighted by a green rectangle in subplot (a)) is shown in subplot (b). The main system includes a diverse mix of particles with varying radii

, and their dynamic behavior is further illustrated in

Supplementary Movie Test.mp4. This video shows spontaneous ordering and motion of particles between two plates, including effects of mutual repulsion and aggregation, and how these behaviors relate to the boundaries.

Realistic boundary motion can be achieved based on the chosen simulation scenario and associated boundary conditions. For simplicity, particles may be confined within a rectangular domain with reflective vertical and horizontal boundaries. However, for more realistic modeling, vertical boundary positions are allowed to move according to a balance of external and internal forces. To simulate quasi-infinite motion in the horizontal direction (which enhances statistical reliability), periodic boundary conditions (i.e., cylindrical geometry) are used. This approach is employed in all supplementary movies, including Supplementary Movie Test.mp4.

Figure 3 presents time-dependent correlations among several key system parameters: (a) the vertical position of the upper plate, (b) the horizontal force (interpreted as friction), and (c) the fractions of particles with five, six, and seven neighbors (colored green, deep red, and orange, respectively). The vertical blue lines indicate the end of the initial transient phase, during which the system self-organizes from a random initial configuration into an equilibrium state. During this period, the system spontaneously forms a hexagonal lattice, significantly increasing the proportion of particles with six neighbors—despite variations in particle size.

Remarkably, this ordered structure is maintained even during horizontal plate motion, up until the point when external heating is applied. This moment is marked by the vertical red line. As expected, the applied heating rapidly disrupts particle positions, increasing defects in the previously ordered hexagonal structure. In other words, the balance shifts from particles with six neighbors towards those with five or seven. This trend is clearly visible in subplot (c), where the orange curve (six neighbors) declines, while the other two rise.

Note that the colors of the curves—orange, green, and deep red—match those used in the scatter plot of

Figure 5 (see its description below). Also, due to the lack of a strict conservation law, the total count of particles with 5, 6, or 7 neighbors does not sum exactly to the total number of particles. This is because some particles have fewer or more neighbors. Near equilibrium, such anomalies are rare and have minimal impact on the system's collective behavior, so their time dependencies are omitted to avoid clutter.

The dynamic behavior from

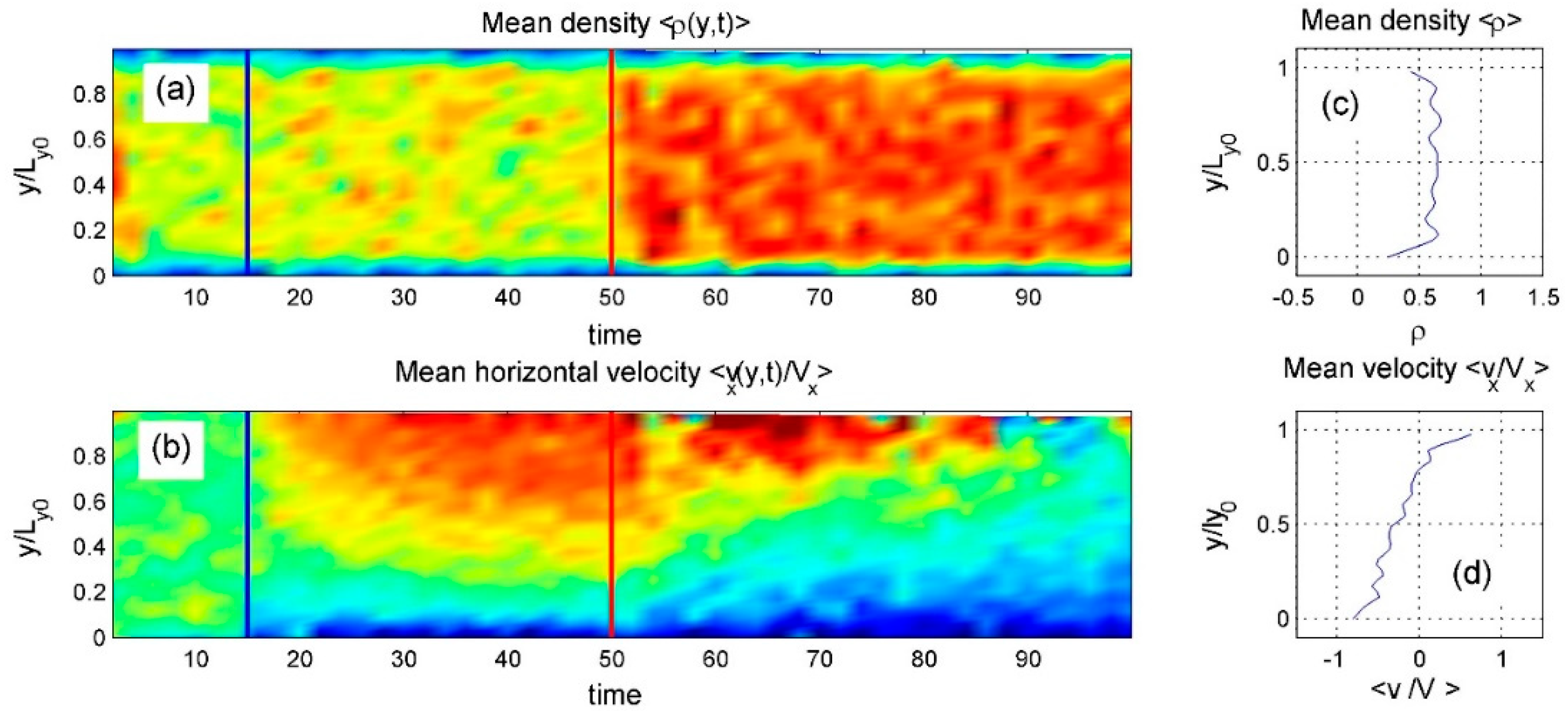

Supplementary Movie Test.mp4 is captured in static form through time-space maps shown in

Figure 4, subplots (a) and (b). Here, the discrete particle distributions are smoothed into continuous density fields using Gaussian convolution and averaged along the horizontal axis. Instantaneous density and velocity distributions appear in subplots (c) and (d). These continuous values are also accumulated over time and displayed as color maps, with individual color bars in (a) and (b) reflecting different physical quantities.

After testing a general model with particles of varying sizes, we focus next on a simplified version with identical particles.

Figure 5 shows such a system, where all particles have equal radii, identical adhesion belts, and interaction parameters, simulated using the general model described in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 at a fixed average density.

Figure 5.

A regular model with identical particles (equal radii and interaction parameters) is simulated using the general setup from

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 at a given average density. After the initial transient phase, a well-ordered hexagonal structure emerges, indicated by orange-colored particles with six neighbors in subplot (b). Subplot (a) shows domains with different lattice orientations, colorized by the sine of the orientation angle. Domain boundaries, marked by chains of 5- and 7-fold defects, appear in green and deep red.

Figure 5.

A regular model with identical particles (equal radii and interaction parameters) is simulated using the general setup from

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 at a given average density. After the initial transient phase, a well-ordered hexagonal structure emerges, indicated by orange-colored particles with six neighbors in subplot (b). Subplot (a) shows domains with different lattice orientations, colorized by the sine of the orientation angle. Domain boundaries, marked by chains of 5- and 7-fold defects, appear in green and deep red.

A spontaneously formed regular hexagonal structure is clearly visible in both subplots (a) and (b). This order is confirmed in subplot (b) by the dominance of orange-colored particles, indicating six neighbors. The system also exhibits distinct domains of hexagonal order, each with a different crystal lattice orientation.

In subplot (a), domain orientation is color-coded by the sine of the angle between each particle and its nearest neighbor. Domain boundaries are visible in subplot (b) as chains of defects—particles with five or seven neighbors—marked in green and deep red, respectively.

To complete the study, we also examine the system behavior at lower average densities. The results are presented in the following figures,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7.

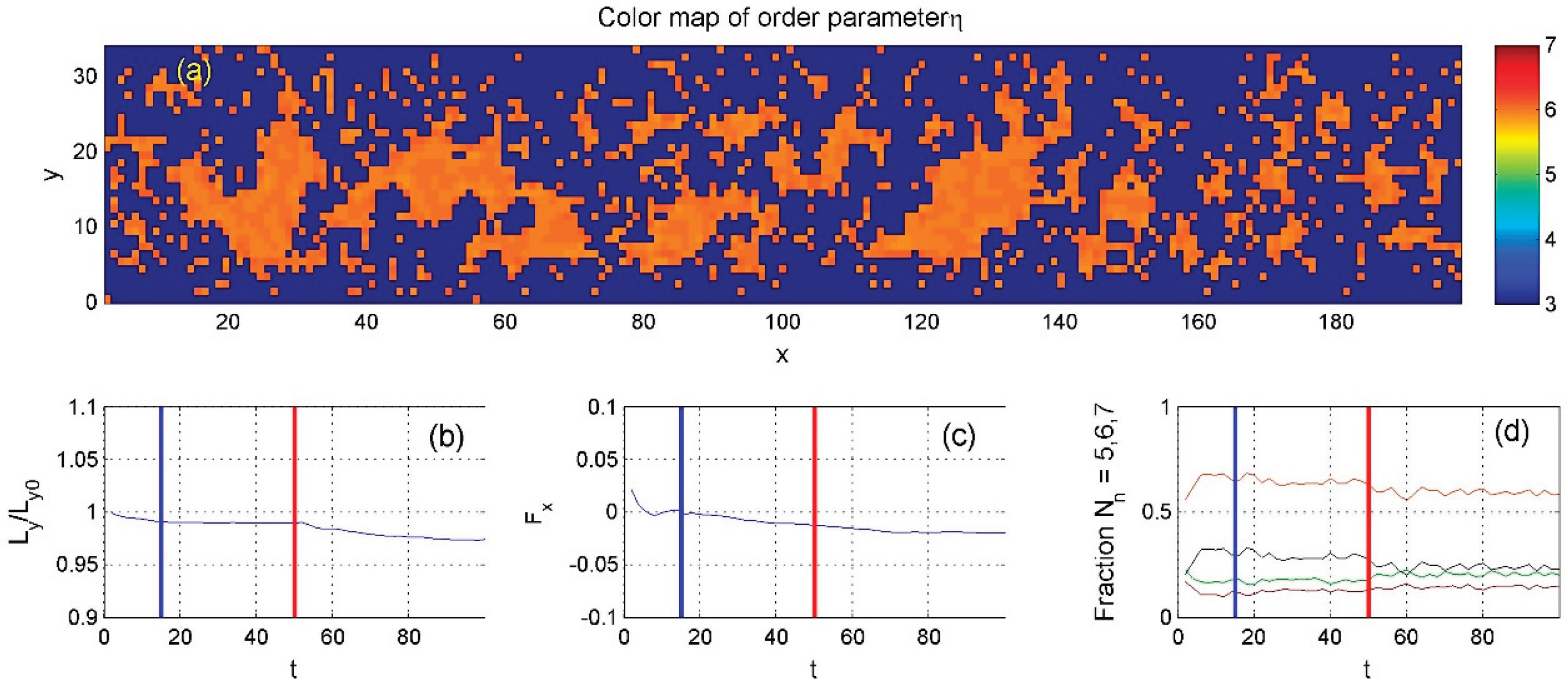

The systems shown in

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 are based on the same model as

Figure 5 but at lower average densities. In

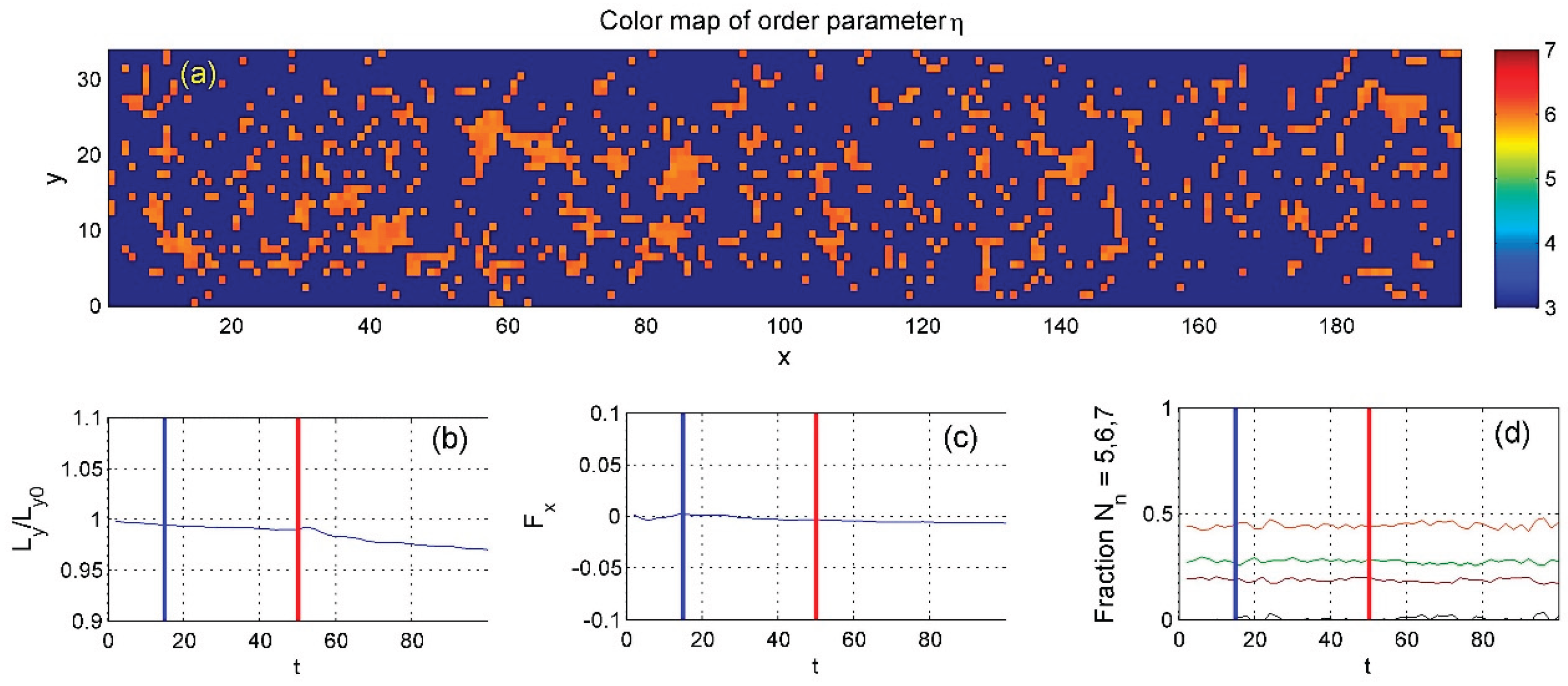

Figure 6, ordered domains remain visible—particularly in subplot (b), where particles in these regions appear orange, indicating six neighbors. However, many particles are now light blue, reflecting a reduced number of neighbors in the Delaunay triangulation. Some domains with preferred lattice orientations are still distinguishable, though less clearly. In contrast,

Figure 7 shows no large orange domains; most particles are light blue, indicating a high level of structural defects and reduced symmetry.

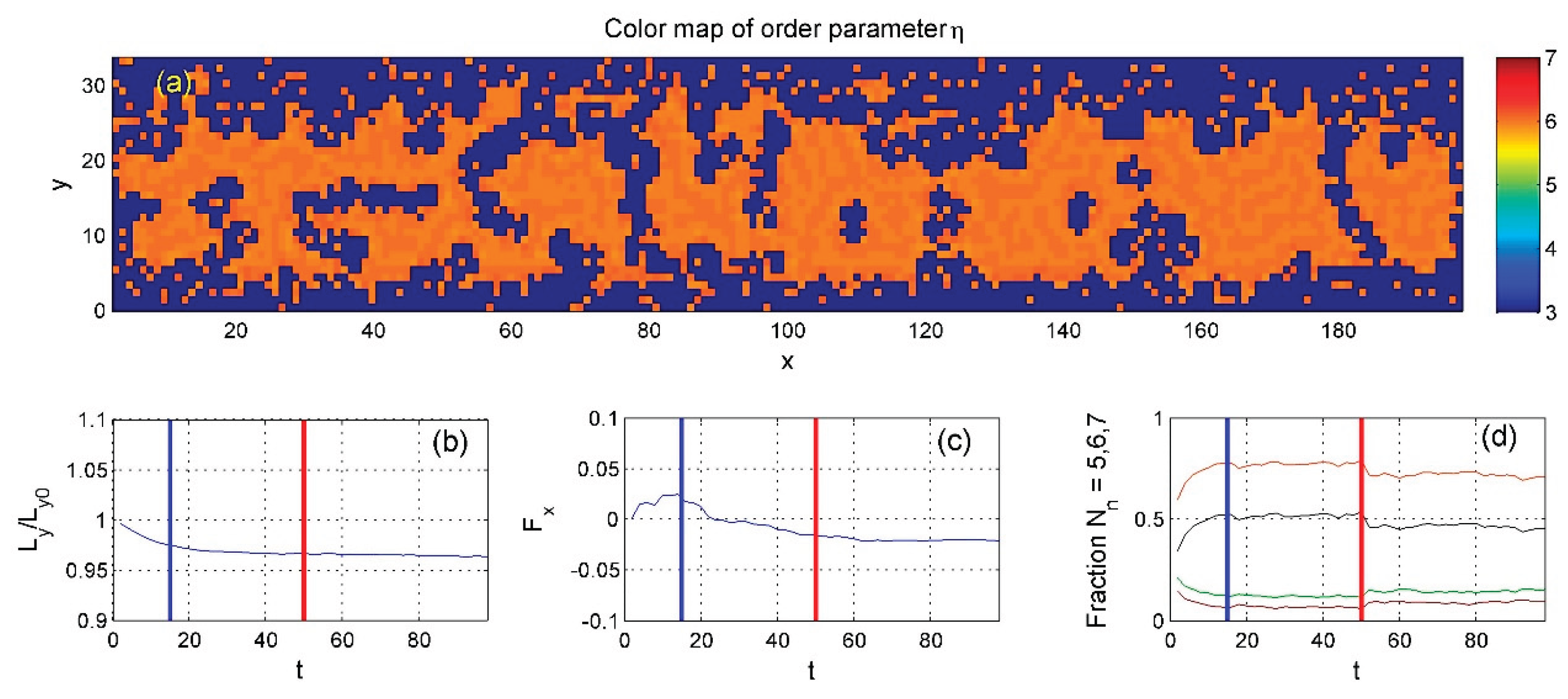

Scatter plots provide a general visual overview of the system’s structure and dynamics, but a continuous approach is more effective for quantitative analysis. To this end, we computed a continuous “order parameter” using Gaussian convolution to estimate local neighbor density, as shown in

Figure 8. In subplot (a), orange regions indicate areas with ideal hexagonal order.

Subplot (b) shows the time-dependent position of the upper boundary, determined by the balance between external vertical force and internal particle pressure (Eq. 8). Subplot (c) displays the total friction force resulting from the relative motion of the upper and lower boundaries.

Subplot (d) shows the time-dependent fractions of particles with different coordination numbers, represented by green, orange, and red curves—matching the color scheme used in the scatter plots. The black curve shows the “order parameter,” defined as the difference between the fraction of six-neighbor particles and the sum of the other two. After heating begins (marked by the red line), this balance shifts, and the system becomes more disordered.

The same calculations were repeated for different average densities, with results shown in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10. The most notable difference in

Figure 10 is that the order parameter fluctuates around zero, indicating that the fraction of six-neighbor particles is roughly equal to the combined fraction of the others.

. The order parameter here is much smaller than in

Figure 8.

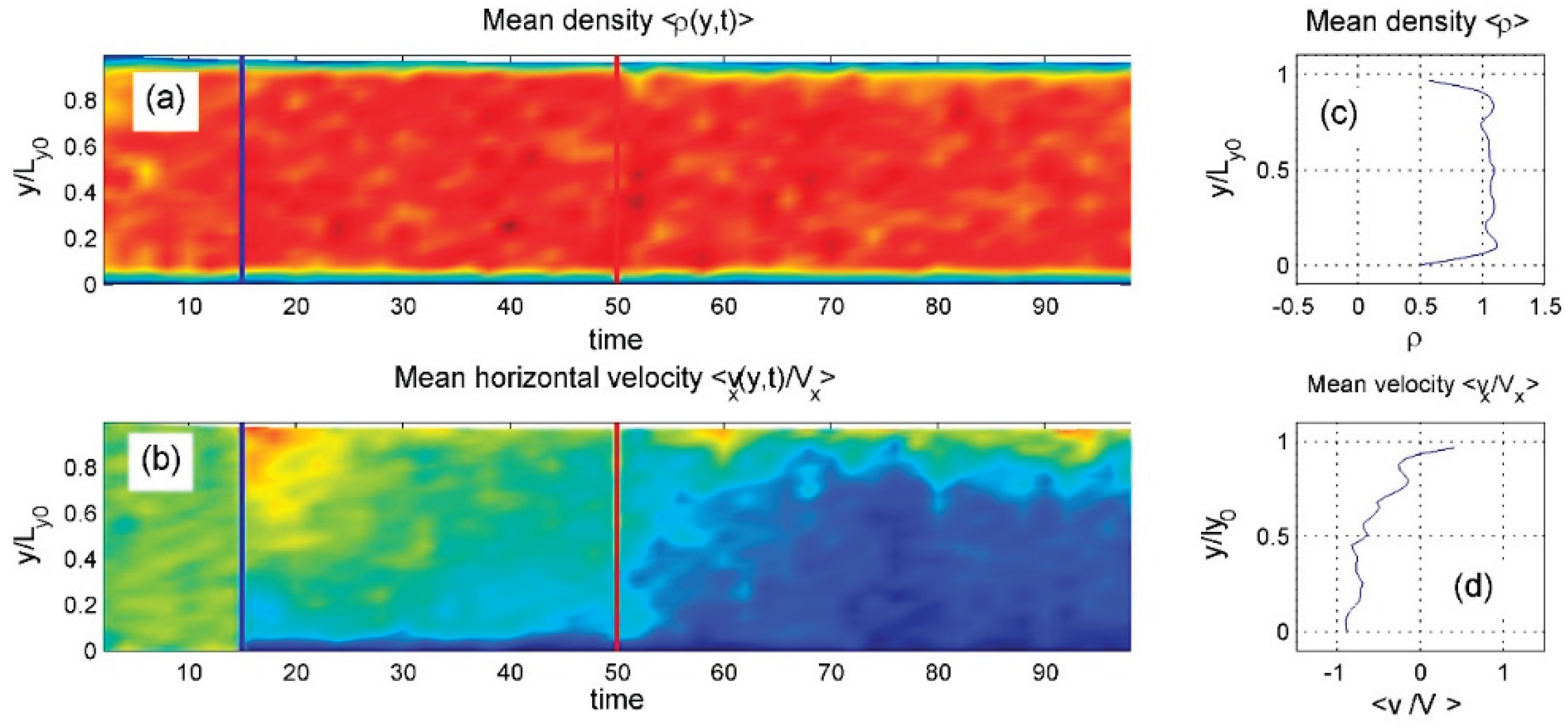

Now we are ready to establish simultaneous time evolution of the spatially distributed density

, kinetic energy

, horizontal velocity

and their values integrated along the x-coordinate:

Although horizontal velocity is central to this study, both velocity components contribute to the formation of streamlines. Therefore, we calculated streamline maps at each time step, with and without heating. Their dynamic evolution—highlighting flow complexity and turbulence, especially under heating—is illustrated in Supplementary Movie Stream.mp4.

Figure 11.

Streamlines from Gaussian-convolved data are shown over horizontal velocity (a) and kinetic energy (b) to highlight laminar flow in the bulk and turbulence near the heated upper surface. This contrast is especially clear in Supplementary Movie Stream.mp4. .

Figure 11.

Streamlines from Gaussian-convolved data are shown over horizontal velocity (a) and kinetic energy (b) to highlight laminar flow in the bulk and turbulence near the heated upper surface. This contrast is especially clear in Supplementary Movie Stream.mp4. .

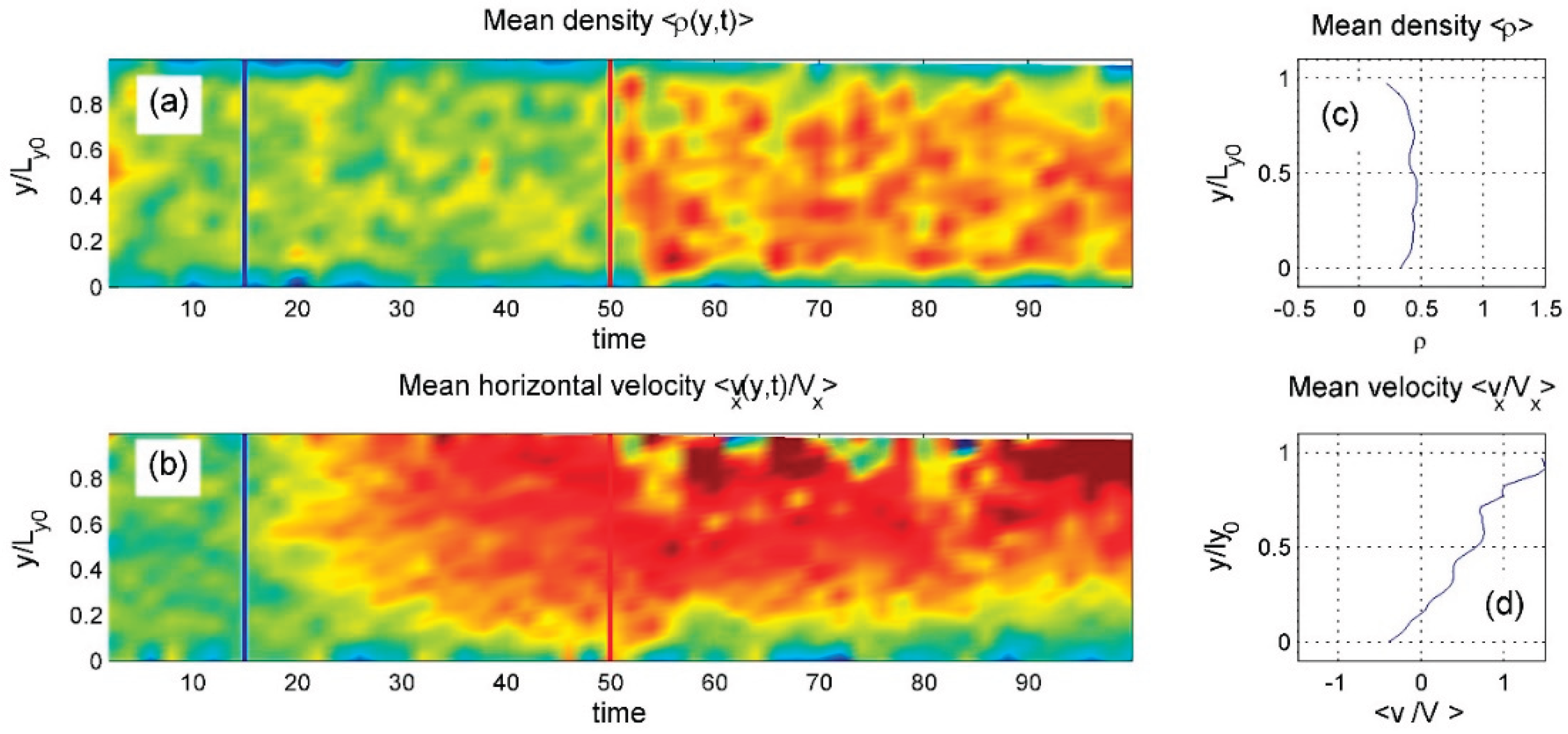

The detailed flow complexity is not captured in the integrated time-dependent maps below. However, these integrations effectively reveal how key global values evolve over time as shear and heating are applied sequentially. As with the order parameter, we present the results as time–space diagrams. Summaries for three average densities are shown in

Figure 12,

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 and the corresponding movies

Regular_1.mp4, Regular_2.mp4, and Regular_3.mp4.

These maps highlight the study’s main findings. Initially, in the absence of heating, the dense system transitions into a near-laminar flow. The lower region, where surface particle spacing matches internal particle spacing, moves faster in the negative direction than the upper region, creating a vertical velocity gradient that becomes nearly linear (see Regular_1.mp4).

When heating is applied, this velocity contrast increases. In the steady state, most of the system moves with the lower surface, while only the uppermost layers retain positive velocity. This shift appears as a step-like velocity profile in subplot (d) of

Figure 12. Although heating slightly affects the density distribution, this influence is minimal in the high-density case.

The intermediate-density system shows the richest behavior. As seen in

Regular_2.mp4 and

Figure 13, the particle density redistributes during the process. Initially, without heating, internal particles move in the positive direction. Once heating is applied, the vertical density profile changes, altering the contact with the upper surface. After a transient phase, the internal particles reverse direction and begin moving negatively.

gradually redistributes in space to reduce interlocking with the commensurate lower substrate causing linear distrubution of the velocity along vertical coordinate.

Finally, the time-dependent behavior of the low-density system is shown in

Regular_3.mp4 and

Figure 14. Here, particle density concentrates near the center, reducing interlocking with both surfaces. Strong thermal fluctuations near the heated upper surface occasionally enhance or weaken coupling with the surface particles, shifting the velocity balance in favor of rightward motion. This behavior contrasts sharply with the leftward flow seen in

Figure 12.