1. Introduction

Infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) can cause cognitive, motor, and sensory deficits that are collectively called HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND), whose main manifestations are loss of attention, concentration, and memory, irritability, and slowness of movement [

1]. Clinically, HAND is characterized by an insidious onset of slow progression, whose first manifestations are difficulty concentrating and decreased executive functions. When the disease progresses, it is possible to observe the onset of symptoms such as psychomotor slowness with depression and other affective symptoms [

2].

Since the introduction of antiretroviral treatment in 1996, the incidence of HIV-associated diseases has decreased while life expectancy has increased in these patients, however, the incidence of HAND has decreased less when compared to other diseases [

2,

3]. Thus, HAND is still a persistent problem, especially in Latin America, where it has the highest prevalence as well as the highest cost to health systems [

4]

In addition, it is important to emphasize that the introduction of this treatment increased the phenotypes related to these neurocognitive disorders associated with HIV [

1,

5], before the introduction of retrovirals, there was only dementia associated with AIDS, while currently, three main phenotypes can be identified: (1) asymptomatic - when neurocognitive symptoms begin to occur that do not interfere with the patient's daily life, (2) moderate disorder - when moderate interference begins to occur in daily activities, and (8) HIV-associated dementia in which there is considerable loss of functional capacity in activities daily allowances [1, 2, 6].

In the face of these neurocognitive symptoms, patients with HAND are predisposed to substance abuse, loss of follow-up of their condition, poorer quality of life, and poor adherence to retroviral treatment [

4,

7], hence the emergence of an effective treatment. Several treatment methodologies have already been proposed, including: intensifying treatment with antiretrovirals, reducing neuroinflammation with TNFα inhibitors; use of neuropsychiatric drugs such as lithium and calcium valproate, among others [

1,

2,

8,

9]

The acquired immunodeficiency virus is characterized by persistent and long-term immune activation, increasing the values of B and T cells, causing an increase in the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, and increasing T cell turnover [

10,

11]. Thus, the use of cholinesterase inhibitors in this context would come as a way to influence immune functions such as the production of cytokines and the activation of T cells, thus having a positive effect on the immune parameters associated with the progression of HIV infection that would be related to chronic T cells [

19].

Patients with HAND may manifest typical dementia as one of the main symptoms, as they are the result of a white matter lesion. In this context, patients with subcortical dementias have cholinergic afferent fibers passing through the injured areas, creating a state of relative cholinergic deficiency. Thus, cholinesterase inhibitors can compensate for cholinergic dementia by inhibiting the degradation of acetylcholine [

13,

14,

15]

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Characterization of the Study

The study is a review where the theoretical and empirical literature on the subject was compiled, involving both quantitative and qualitative aspects. The acronym PICOTT for the creation of the guiding question: P (population): people living with the HIV and with HAND (symptoms of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders); I (intervention): use of cholinesterase inhibitors; O (Outcomes/Outcomes) any alteration in patients using this drug has, T (Type of study) randomized and non-randomized studies and T (Time of study) all studies published and found in the cited databases without determination of temporality. The study used the literature available in the area to trace the current state of knowledge about the use of cholinesterase inhibitors in people living with HIV and HAND (symptoms of neurocognitive disorders).

2.2. Data Collection

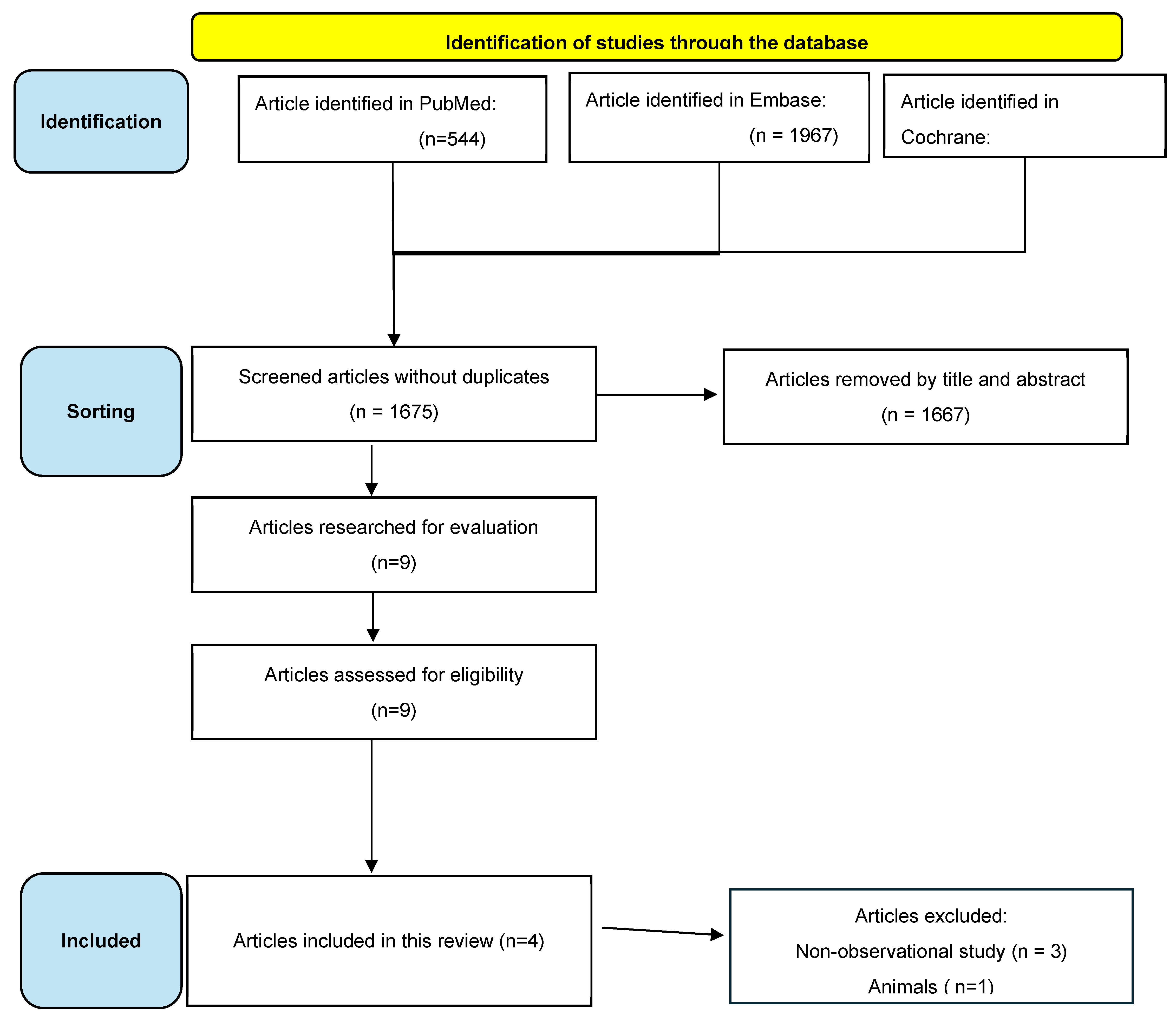

The article databases used to search for information on the subject were: PubMed (provides access to Medline), Cochrane Library and Embase (provides access to the main abstracts on the subject). First, the initial search and screening of the articles pertinent to the theme were carried out, extracting the main information from the articles. Next, eligibility was determined, where the inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied, resulting in the final number of articles used to develop the study.

2.3. Collection Procedures

A search was carried out in four stages: Identification (initial search contemplating all the articles found through the search words), Screening (removal of articles incompatible with the search question by title or abstract), Eligibility (stage in which the inclusion or exclusion criteria are applied) and Inclusion (stage in which the corpus of the work is established).

The articles were screened during November 2024, using the following search strategy "("HIV- associated neurocognitive disorder" OR "HIV - related neurocognitive impairment" OR "HIV neurocognitive disorder" OR "HAND") AND ("cholinesterase inhibitors" OR "ChEIs" OR "donepezil" OR "rivastigmine" OR "galantamine" OR "acetylcholinesterase inhibitors" OR "butyrylcholinesterase inhibitors" OR "cholinergic therapy" OR "cholinergic drugs")". After inserting the strategy in the databases, it was possible to identify the articles. Duplicate articles were removed, followed by screening by title and abstract, removing articles that did not address the use of cholinesterase inhibitors in patients living with HIV and HAND. After screening, the eligibility of the articles was evaluated through inclusion and exclusion criteria. Next, the observational studies were placed on the Newcastle-Ottawa scale to assess their methodological quality, with 2 reviewers to carry out these four stages, and a third reviewer will enter in case of disagreement with the studies selected for the corpus of the article.

2.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria:

The inclusion criteria were: (1) patients living with HIV and symptoms compatible with HAND, (2) use of cholinesterase, (3) studies in English, Portuguese, and Spanish. The exclusion criteria were: (1) articles that do not have a compatible title, (2) do not have an abstract available in the database, (3) are not patients living with the HIV, (4) do not use cholinesterase, (5) do not have symptoms compatible with neurocognitive disorders. Using these criteria, the works were selected, and the corpus of the work in the Inclusion stage was established. After establishing the corpus of the work, the articles were read and analyzed.

3. Results

Figure 1 shows the process of selecting articles, including deleting articles for specific reasons. Initially, 544 articles were identified from the PubMed database; 1967 articles in Embase and 64 articles in Cochrane, making a total of 2575 articles. After the removal of duplicates, 1675 articles were analyzed. After a preliminary reading, 1667 articles were eliminated because their titles and abstracts did not mention patients who had HAND and who were using cholinesterase inhibitors. Eight articles were available and included based on the final analysis.

Table 1 summarizes four studies on rivastigmine, including randomized trials and a review, with sample sizes ranging from 17 to 29. They investigated rivastigmine's impact on brain microstructure and various neurocognitive functions. Results varied, showing some improvements in brain measures and cognition, but not consistent across all functional or mortality outcomes.

4. Discussion

Studies indicate that the use of cholinesterase inhibitors, including rivastigmine, shows limited efficacy in the management of patients with HAND (HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorders). Although some studies have suggested potential benefits [

13,

14,

15], the most recent evidence available and included in these studies does not conclusively support the implementation of this class of drugs as a standard therapeutic strategy for this population.

Among the studies analyzed identified significant changes in brain microstructural properties, such as T2 relaxation time and magnetization transfer rate (MTR), were identified after the use of rivastigmine12. These changes indicate a possible neuroprotective action on specific areas of the brain. However, the outcomes reported were limited to brain structural parameters, with no demonstration of direct and significant impact on clinical parameters or functionality of individuals undergoing use [

19]

Additionally, highlighted potential benefits in the use of rivastigmine when associated with combination antiretroviral therapy (cART). The study points out that although cholinesterase inhibitors are not widely used in the management of HAND, their action can complement neuroprotective strategies, promoting improvements in neurocognitive functions and optimizing the effects of cART. These findings reinforce the importance of further investigating the role of these agents in the context of HAND management [

16]

However, the other studies showed less consistent results. In a randomized controlled trial, no significant differences in primary outcomes related to cognition or functionality in patients treated with transdermal rivastigmine. Similarly, the adverse effects associated with the use of the drug, including gastrointestinal symptoms and dizziness, led to dose reduction or treatment interruption in some cases, which limited the feasibility of continued use of the therapy [

18,

17]

Because of this, as both studies were the most robust, it is interesting to highlight the methodological differences between them: in a randomized clinical trial with 48 weeks of follow-up, which used the NPZ-7 score as the primary outcome, which is composed of seven neurocognitive measures. The study found no statistically significant differences between the groups (rivastigmine, lithium, and control) for global improvement in cognition, despite observing a positive trend in specific domains, such as information processing speed (week 12) and executive function (week 48). One of the studies adopted the ADAS-Cog and a reduced set of neuropsychological measures in a 20-week crossover clinical trial and reported that rivastigmine improved processing speed, but not other cognitive domains [

18]

These methodological differences raise the question of the appropriateness of the scales used to assess the efficacy of rivastigmine in HAND. The NPZ-7 includes a more comprehensive assessment of cognition [

18], while the ADAS-Cog was originally developed for Alzheimer's and may not capture subtle deficits in HAND12. Therefore, future studies should consider the standardization of scales, prioritizing instruments that assess specific cognitive domains, such as the RBANS (Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status), and the inclusion of measures of daily functioning, such as the ADCS-ADL, for a more comprehensive assessment of the impact of the intervention.

The overall findings of this review suggest that, despite initial hypotheses about the potential of cholinesterase inhibitors to mitigate the neurocognitive deficits associated with HAND [

13,

14,

15], the available evidence is not robust enough to justify their widespread clinical use [

18,

17]. The absence of substantial improvements in cognitive outcomes, coupled with the occurrence of adverse effects, reinforces the need for caution when considering this therapeutic approach.

The variability of the observed results can be explained, in part, by methodological limitations in the studies reviewed. Most investigations included small samples, which compromises the generalization of the findings. In addition, the criteria for the characterization of HAND and the parameters evaluated varied among the studies, making it difficult to directly compare and synthesize the results. Importantly, much of the research has focused on patients in the moderate to advanced stages of the condition, while the effects on patients in the early stages of HAND remain underexplored.

In addition, most studies did not assess functional outcomes, such as quality of life and adherence to antiretroviral treatment, which are key factors in determining the clinical relevance of any therapeutic intervention. This gap limits the understanding of the real impact of cholinesterase inhibitors on the lives of patients with HAND.

The authors acknowledge the ongoing efforts of the scientific community in addressing the challenges posed by HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND), which continue to significantly impact the quality of life and treatment adherence among individuals living with HIV. The contributions of previous studies investigating the role of cholinesterase inhibitors, despite yielding limited and heterogeneous results, have provided valuable insights into the complexity of HAND and the limitations of current therapeutic approaches.

The authors also recognize the need for more comprehensive and methodologically robust research aimed at identifying effective interventions. Future studies should explore combined strategies that integrate neuroprotective agents, optimization of antiretroviral therapy, and the modulation of neuroinflammatory processes. Advancements in this area will depend on continued interdisciplinary collaboration and innovation in the field of neuro-HIV research.

5. Conclusions

HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) represent a significant challenge in the management of patients living with the virus, due to the profound impact on quality of life and adherence to antiretroviral treatment. Despite the theoretical potential of cholinesterase inhibitors, the findings of this integrative review did not provide consistent evidence to support the use of these drugs as an effective therapeutic strategy for HAND.

The studies analyzed demonstrated heterogeneous results, with modest benefits in specific neurocognitive parameters, such as attention and memory, but were not able to prove clinically relevant or functional improvements. In addition, the occurrence of adverse events and methodological variability limited the robustness of the conclusions, indicating that this therapeutic approach still lacks more consistent evidence.

Thus, it is necessary to invest in more comprehensive and methodologically rigorous research to explore alternative and more effective therapeutic approaches. Strategies that combine neuroprotective interventions, optimization of antiretroviral treatment, and reduction of neuroinflammation may be more promising for the management of HAND.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, DABH, VBF, FSMMF, LRF, and PVSF; methodology, DABH; validation, DABH, VBF, and FSMMF; formal analysis, PF.; data curation, DABH.; writing—original draft preparation, VBF, FSMMF, and LRF.; writing—review and editing, FSMMF and LRF.; supervision, PVSF.; project administration, DABH and PVSF. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| HAND |

HIV-Associated Neurocognitive Disorder |

| HIV |

Human immunodeficiency virus |

| MTR |

Magnetization transfer rate |

| cART |

Associated with combination antiretroviral therapy |

| RBANS |

Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status |

| NPZ-7 |

Neuropsychological composite score |

| ADAS-Cog |

Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale-Cognitive Subscale |

References

- Irollo E, Luchetti S, Chikhladze M, et al. Mechanisms of neuronal dysfunction in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2021;78(9):4283–4303. [CrossRef]

- Eggers C, Arendt G, Hahn K, et al. HIV-1-associated neurocognitive disorder: epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. J Neurol. 2017;264(8):1715–1727. [CrossRef]

- Saloner R, Cysique LA. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders: a global perspective. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2017;23(9–10):860–869. [CrossRef]

- Nweke M, Umeh C, Daramola O, et al. Impact of HIV-associated cognitive impairment on functional independence, frailty and quality of life in the modern era: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):1–10. [CrossRef]

- Sacktor, N. Changing clinical phenotypes of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. J Neurovirol. 2017;24(2):141–145. [CrossRef]

- Sanmarti M, Ibáñez L, Huertas S, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. J Mol Psychiatry. 2014;2(1):1–10. [CrossRef]

- Zenebe Y, Adane F, Mersha A, et al. Worldwide occurrence of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders and its associated factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:1–19. [CrossRef]

- Avedissian SN, Piliero PJ, Haddad M, et al. Pharmacologic approaches to HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2020;54(1):102–108. [CrossRef]

- Kolson, DL. Developments in neuroprotection for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND). Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2022;19(5):344–357. [CrossRef]

- Hazenberg MD, Stuart JW, Otto SA, et al. T-cell division in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-1 infection is mainly due to immune activation: a longitudinal analysis in patients before and during highly active antiretroviral. [CrossRef]

- Brenchley JM, Price DA, Schacker TW, et al. Microbial translocation is a cause of systemic immune activation in chronic HIV infection. Nat Med. 2006;12(12):1365–1371. [CrossRef]

- Valdés-Ferrer SI, Crispín JC, Belaunzarán PF, et al. Acetylcholine-esterase inhibitor pyridostigmine decreases T cell overactivation in patients infected by HIV. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2009;25(8):749–755. [CrossRef]

- Alisky, JM. Could cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine alleviate HIV dementia? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;38(1):113–114. [CrossRef]

- Erkinjuntti T, Román G, Gauthier S, et al. Emerging therapies for vascular dementia and vascular cognitive impairment. Stroke. 2004;35(4):1010–1017. [CrossRef]

- Langford TD, Letendre SL, Marcotte TD, et al. Severe, demyelinating leukoencephalopathy in AIDS patients on antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2002;16(7):1019–1029. [CrossRef]

- Sharma MK, Dwivedi P, Sahu AK, et al. Formulation, development and biological evaluation of rivastigmine loaded liposomes for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Indo Am J Pharm Sci. 2022;9(5):207–222. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Moreno JA, Fumaz CR, Ferrer MJ, et al. Transdermal rivastigmine for HIV-associated cognitive impairment: a randomized pilot study. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):1–14. [CrossRef]

- Simioni S, Cavassini M, Annoni JM, et al. Rivastigmine for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology. 2013;80(6):553–560. [CrossRef]

- Perrotta G, Bonnier G, Meskaldji DE, et al. Rivastigmine decreases brain damage in HIV patients with mild cognitive deficits. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2017;4(12):915–920. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).