Submitted:

09 June 2025

Posted:

10 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

2.1.1. Ecological Hardening Agents

2.1.2. Tannin Extraction

2.2. Tannin Characterization

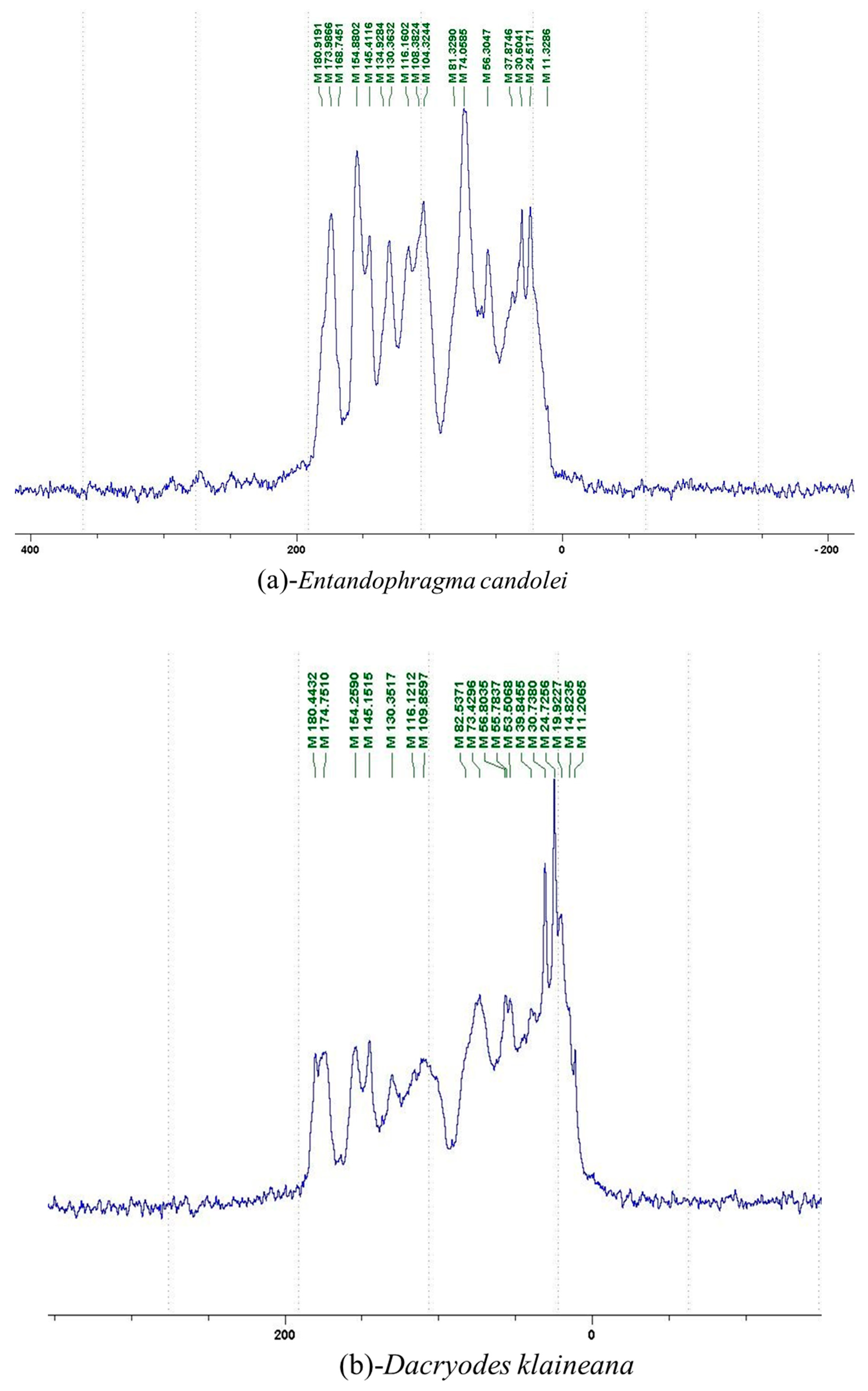

2.2.1. 13C NMR Analysis

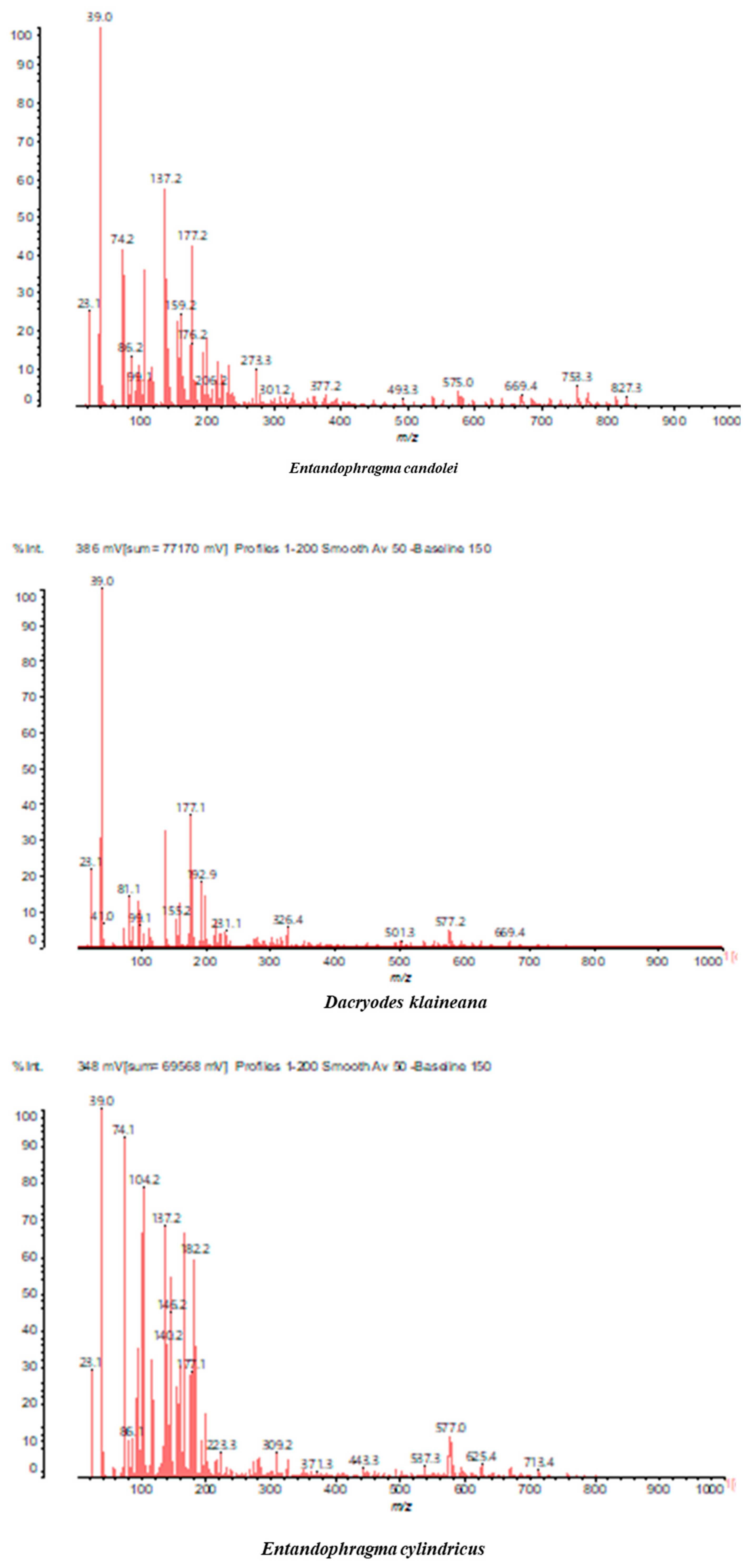

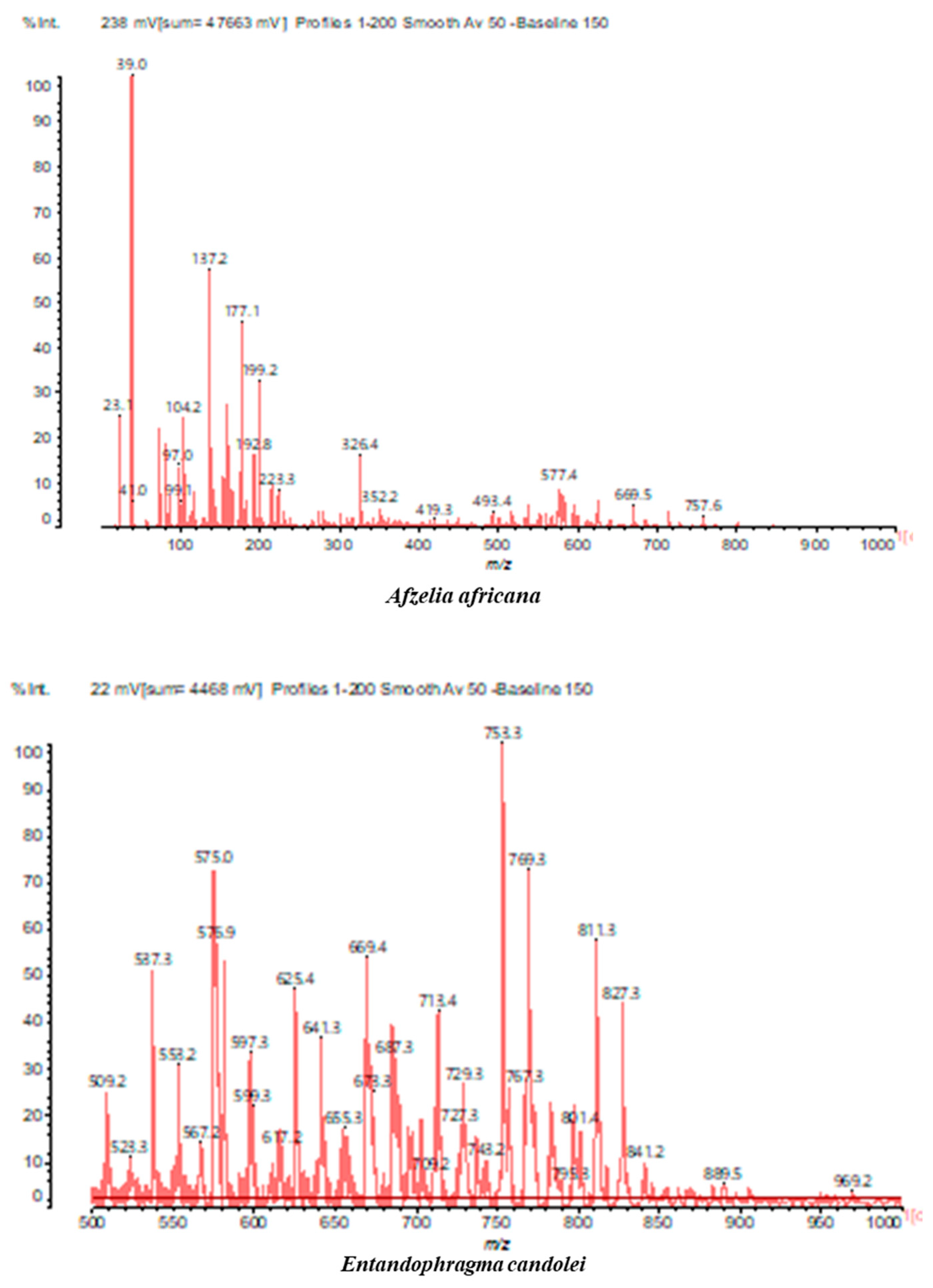

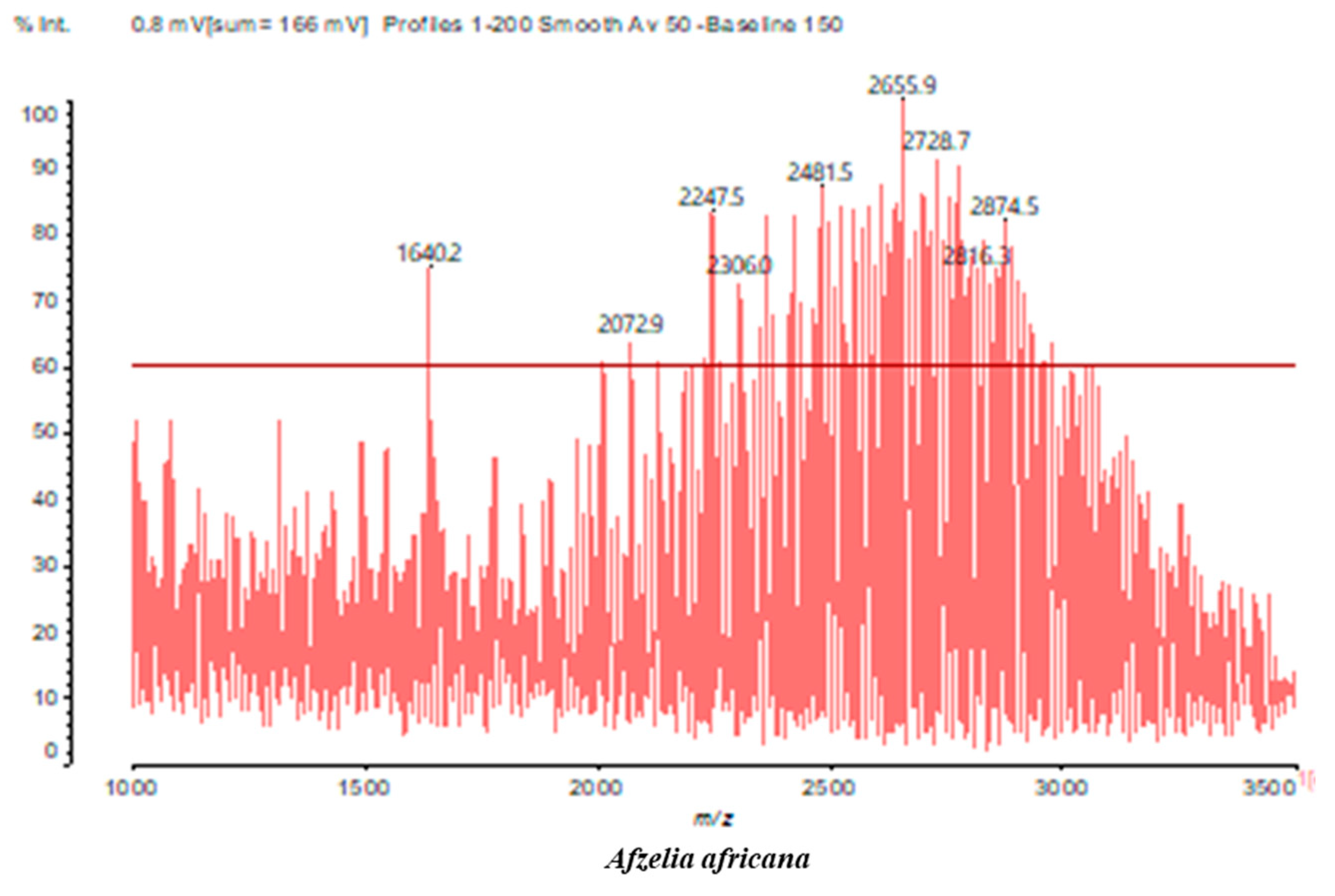

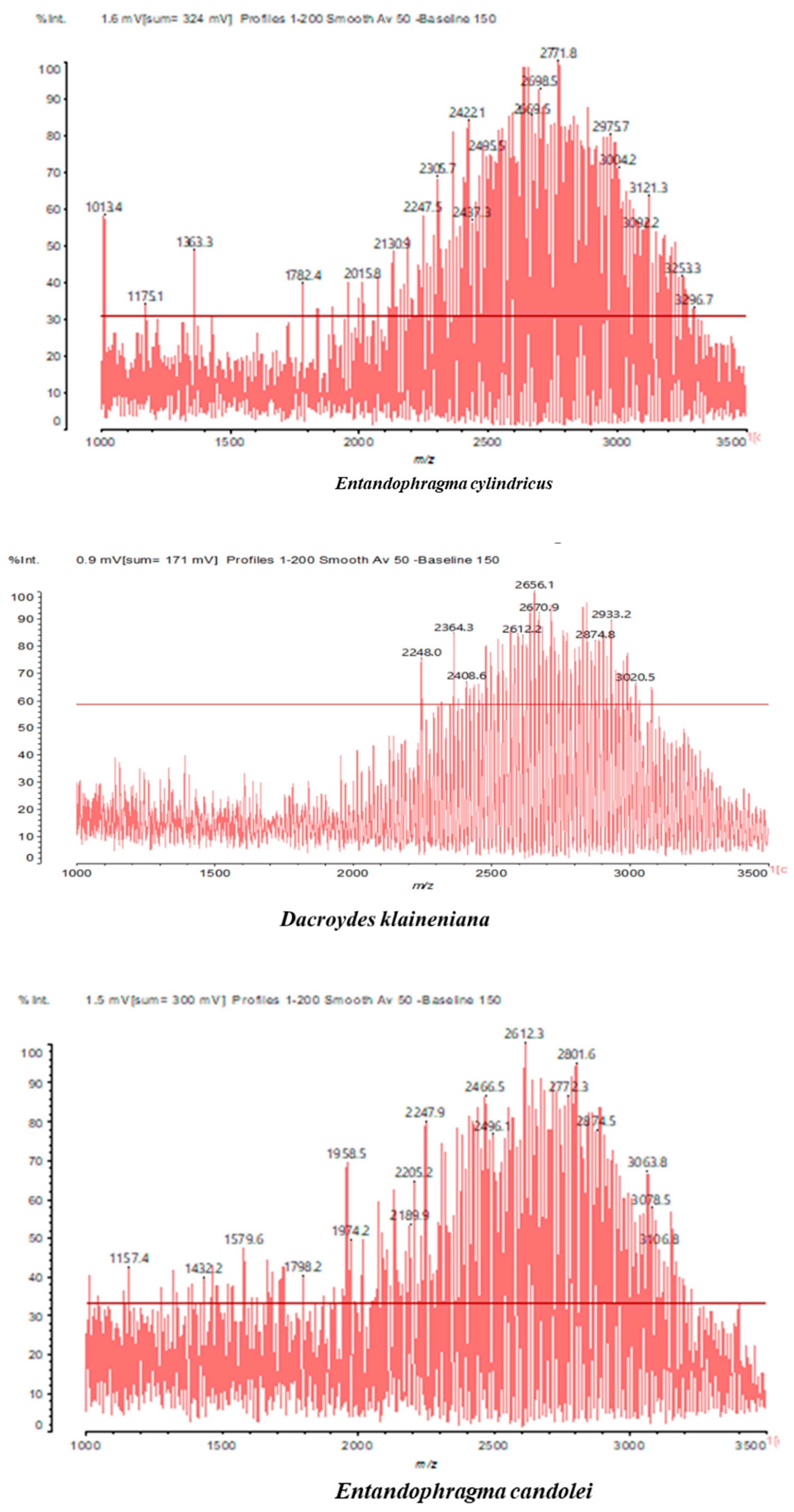

2.2.2. MALDI-TOF Analysis

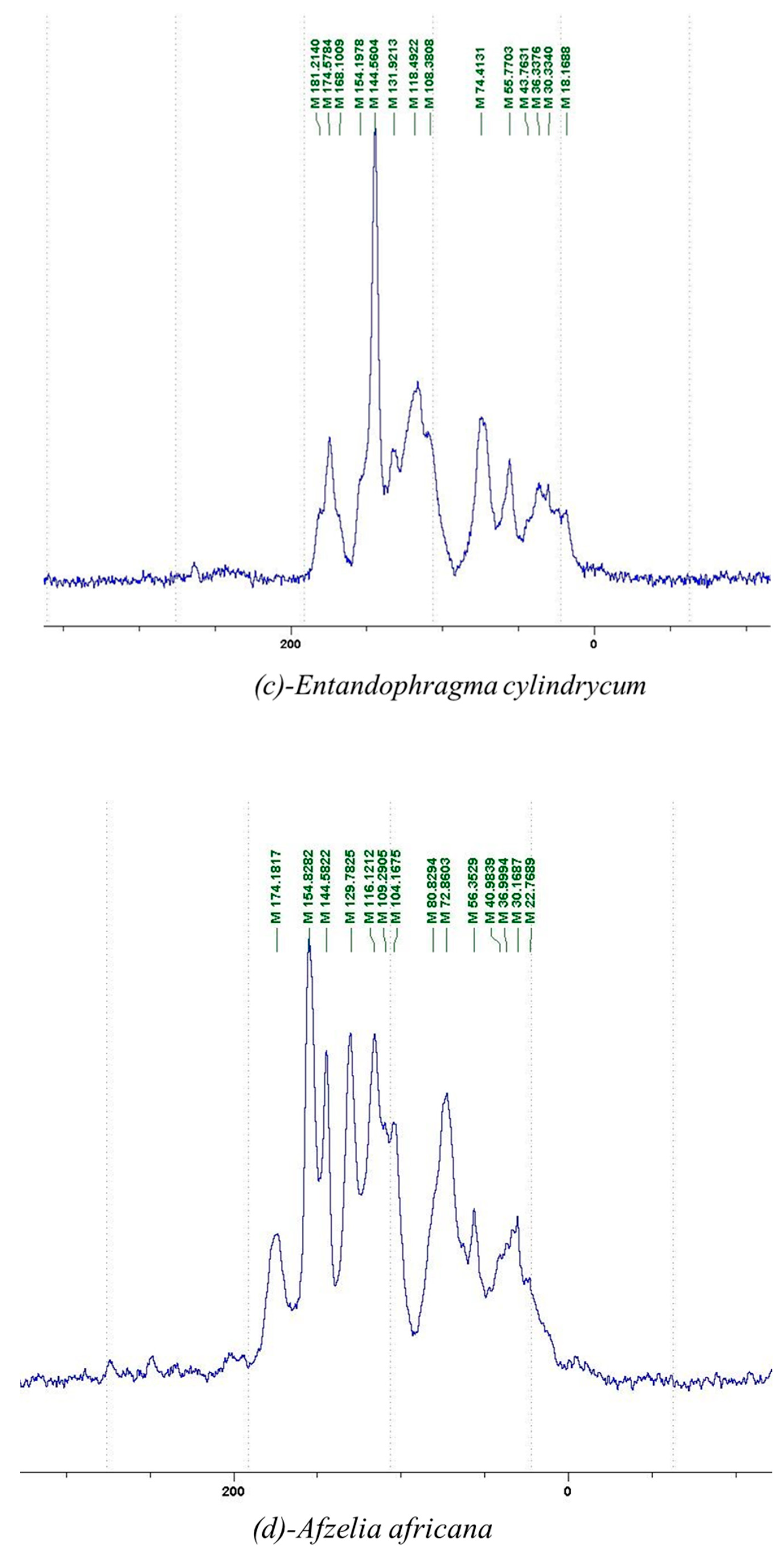

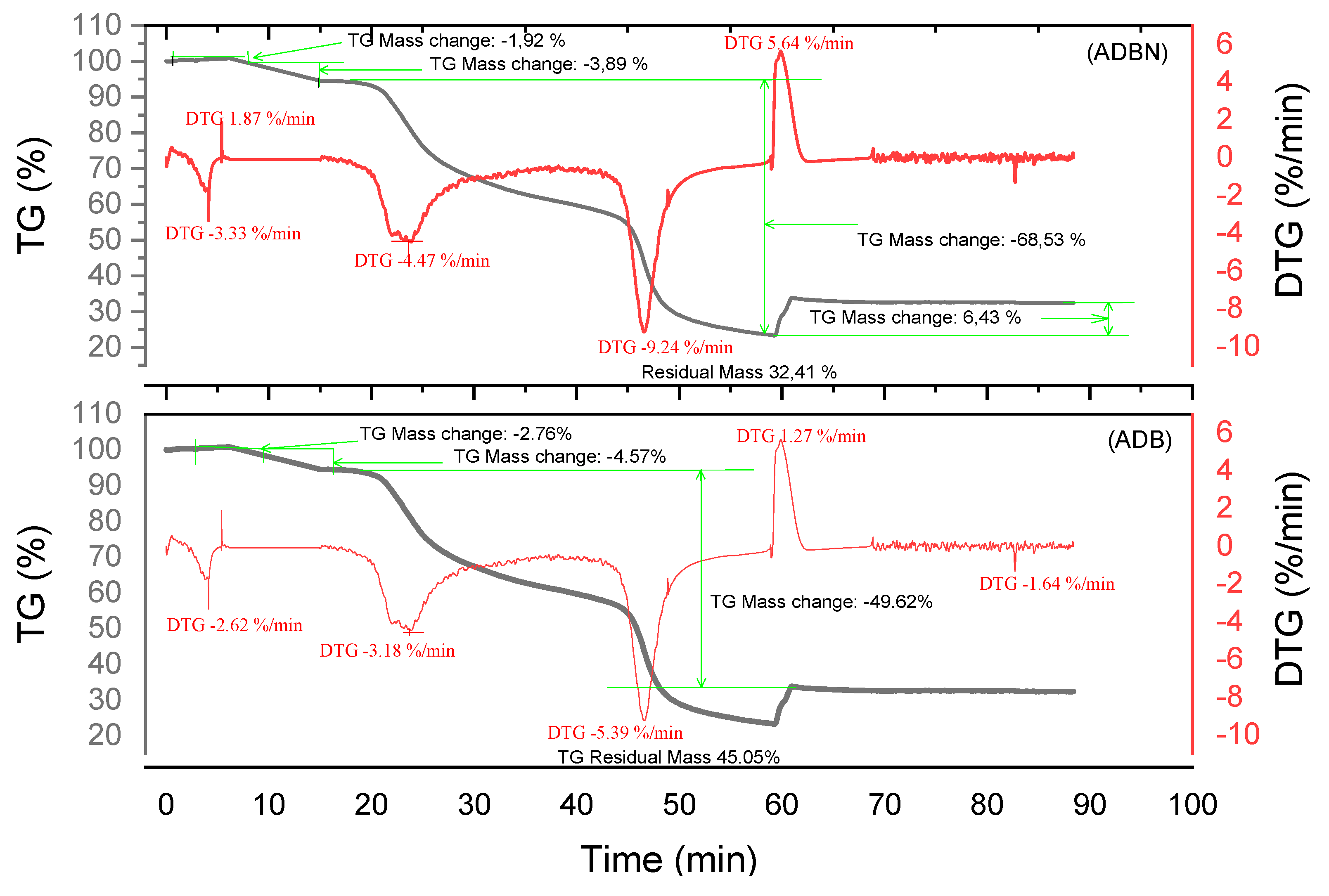

2.2.3. Thermogravimetric Analysis of Tannin

2.3. Resin Characterization

2.3.1. Resin Formulation

2.3.2. Physical Characterization of Resins: Gel Time

2.3.3. Thermogravimetric Analysis of Resins

2.3.4. Thermomechanical Analysis of the Resin

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Tannin Extraction Yield from Different Woods

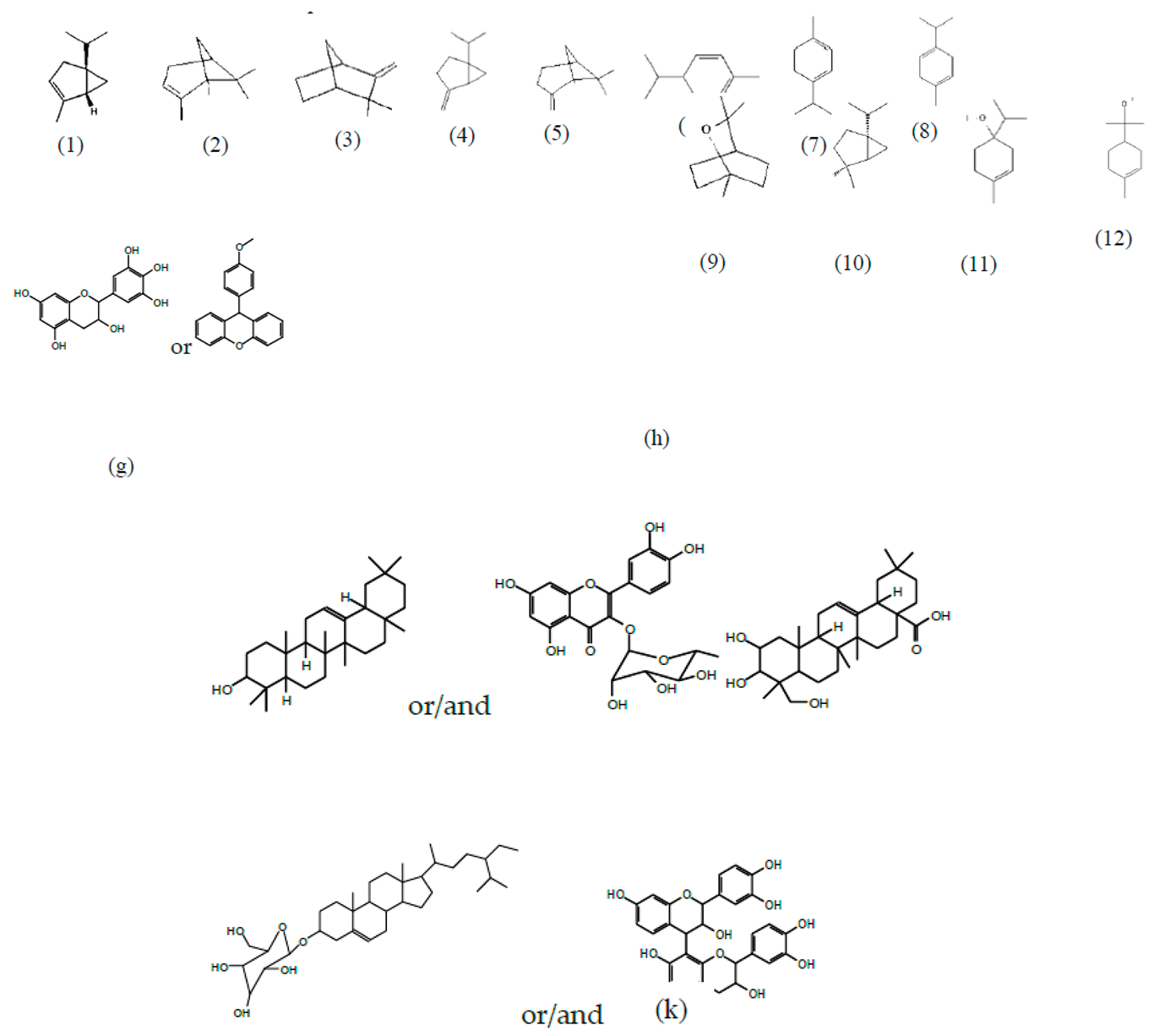

3.2. Chemical Structures of Molecules Identified in the Samples

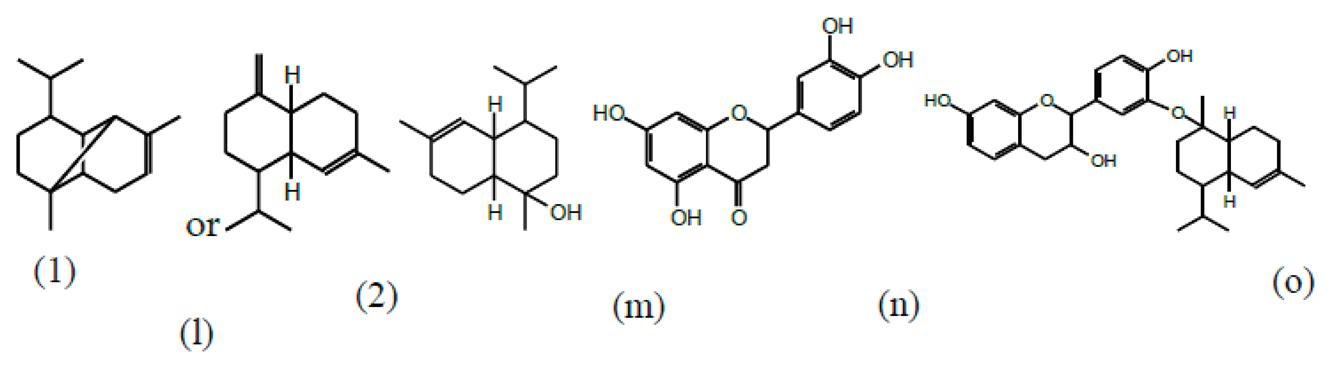

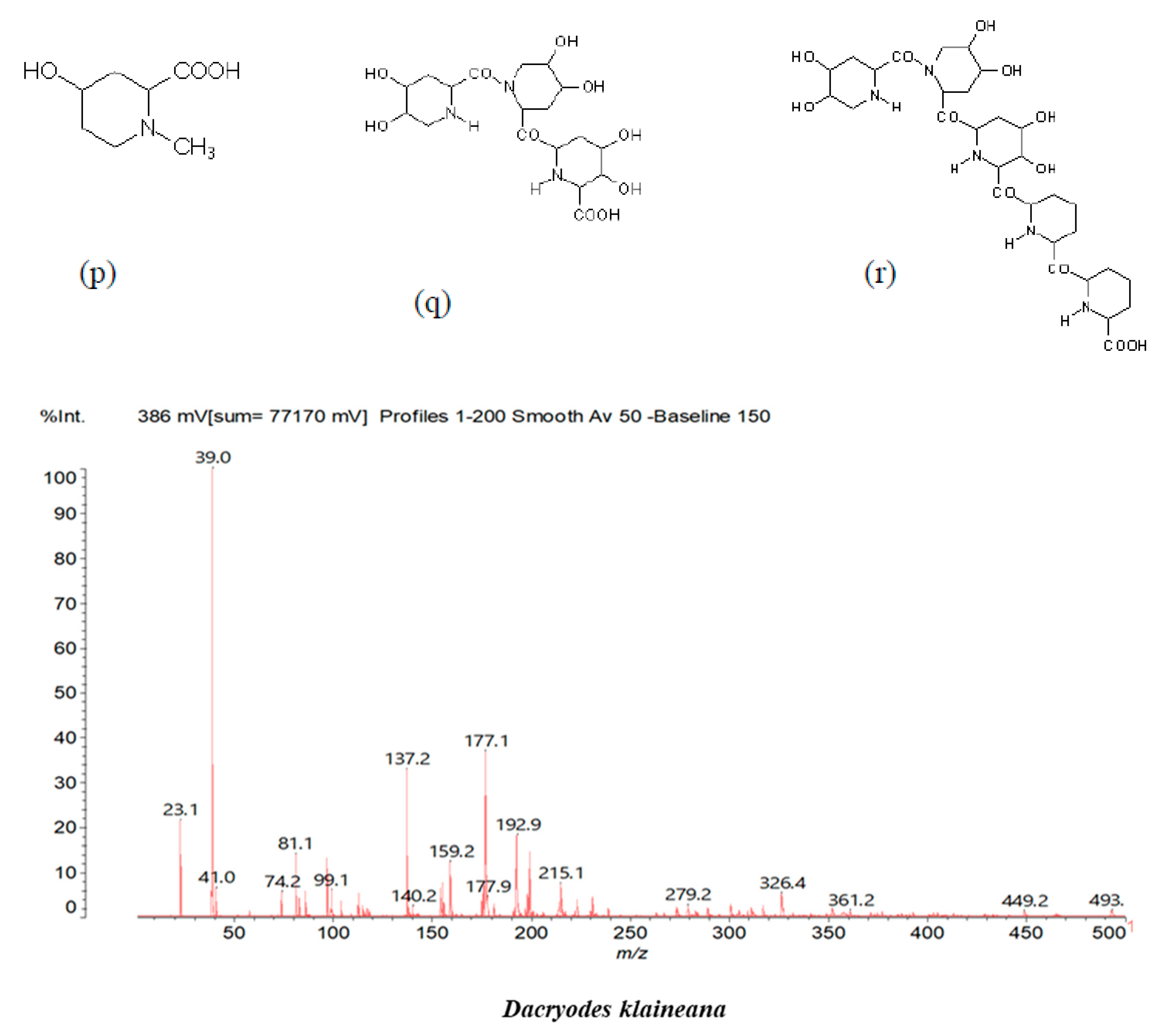

3.3. Structural Determination of Molecules from Different Tannin Samples

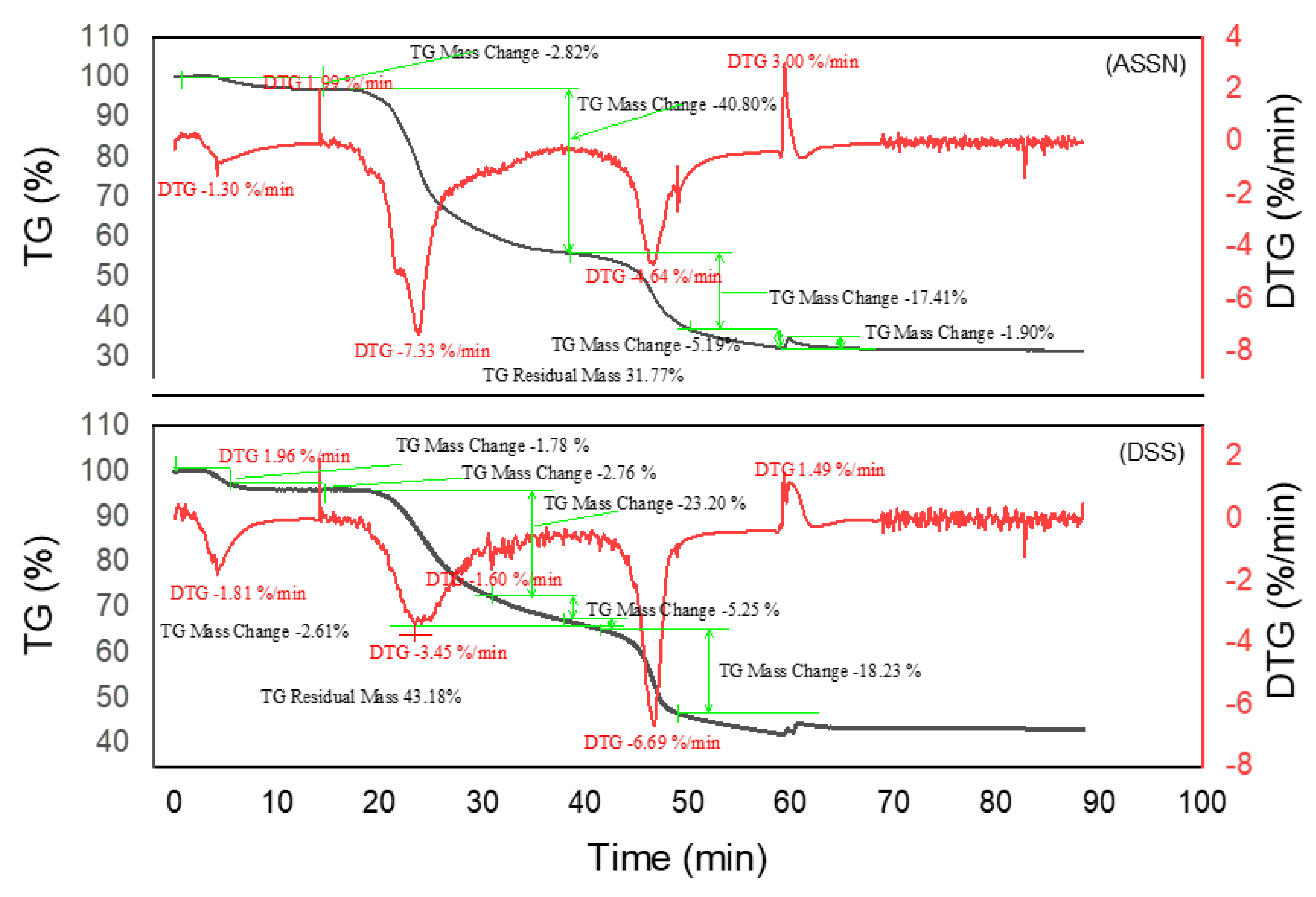

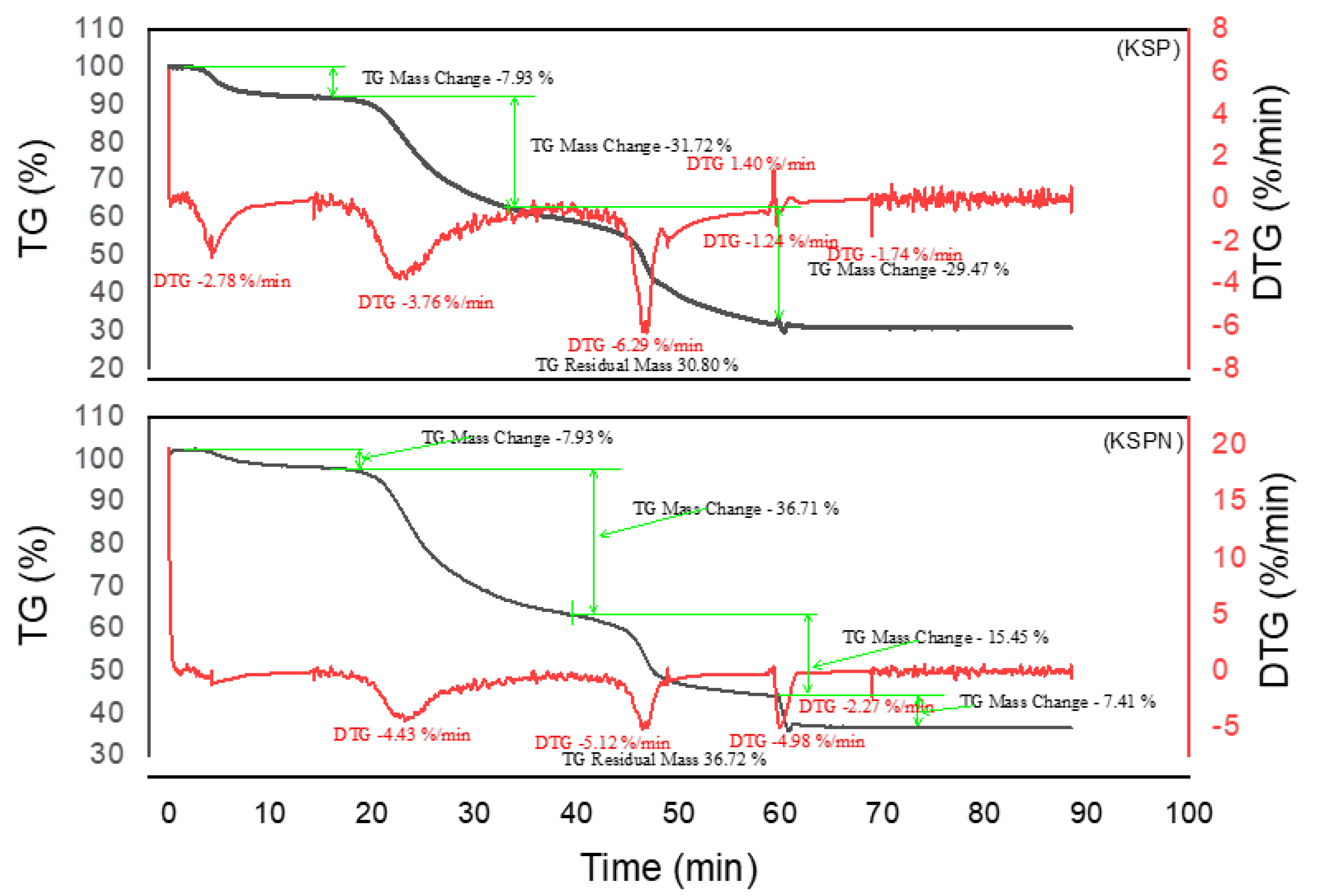

3.4. Thermogravimetric Analysis of Tannins and Resins

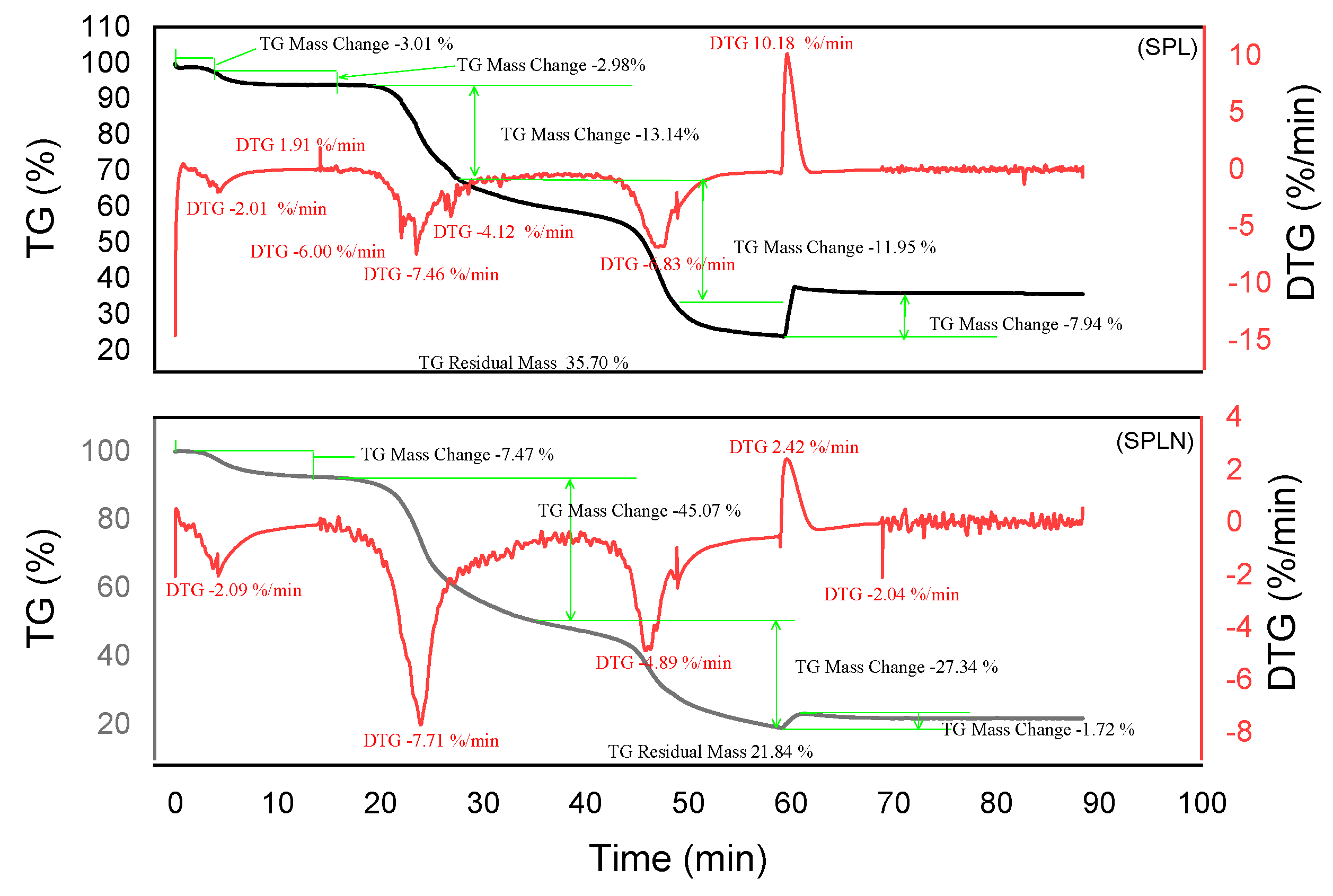

3.5. Resin Gel Time

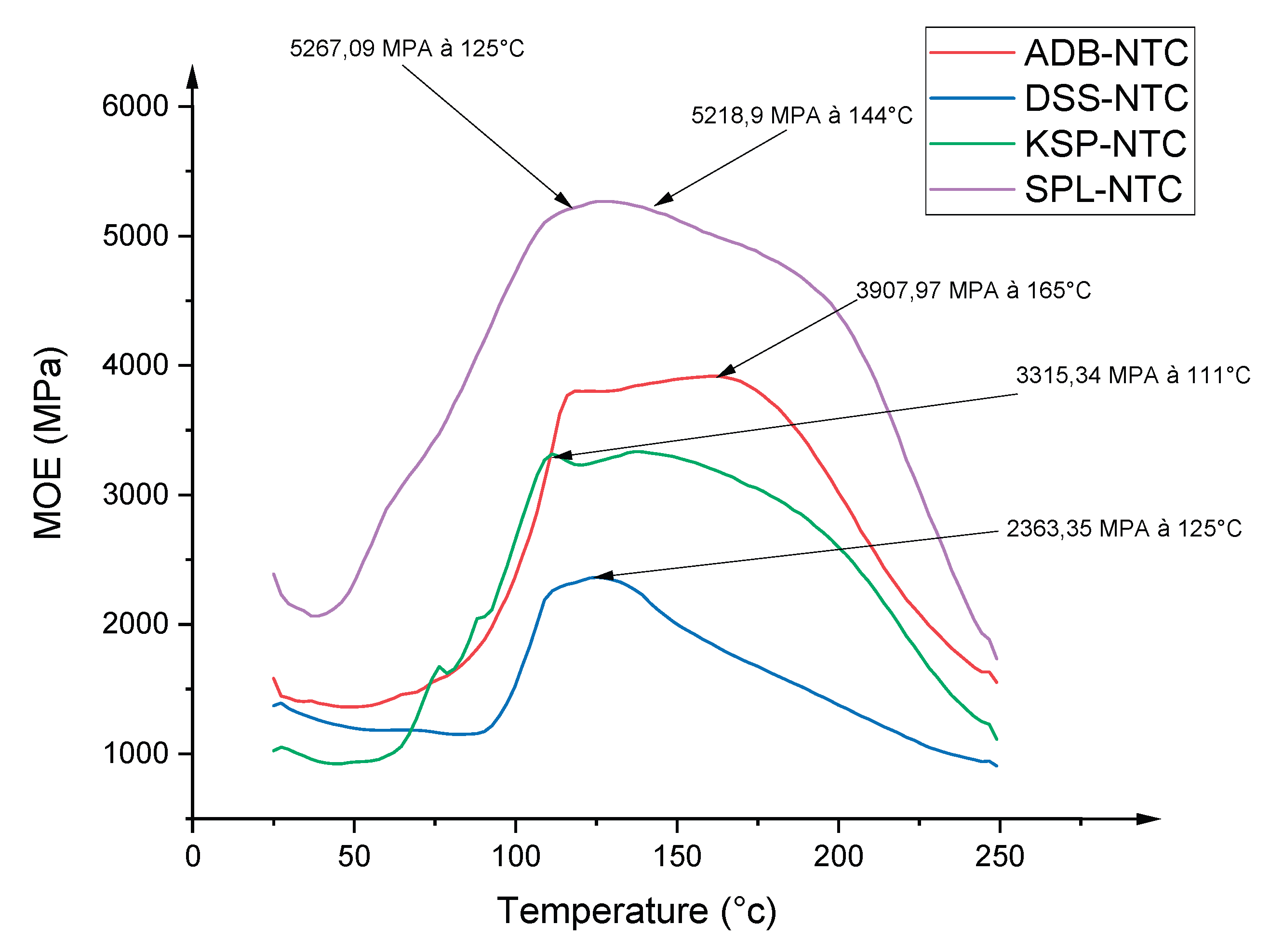

3.6. Thermomechanical Analysis of the Resin

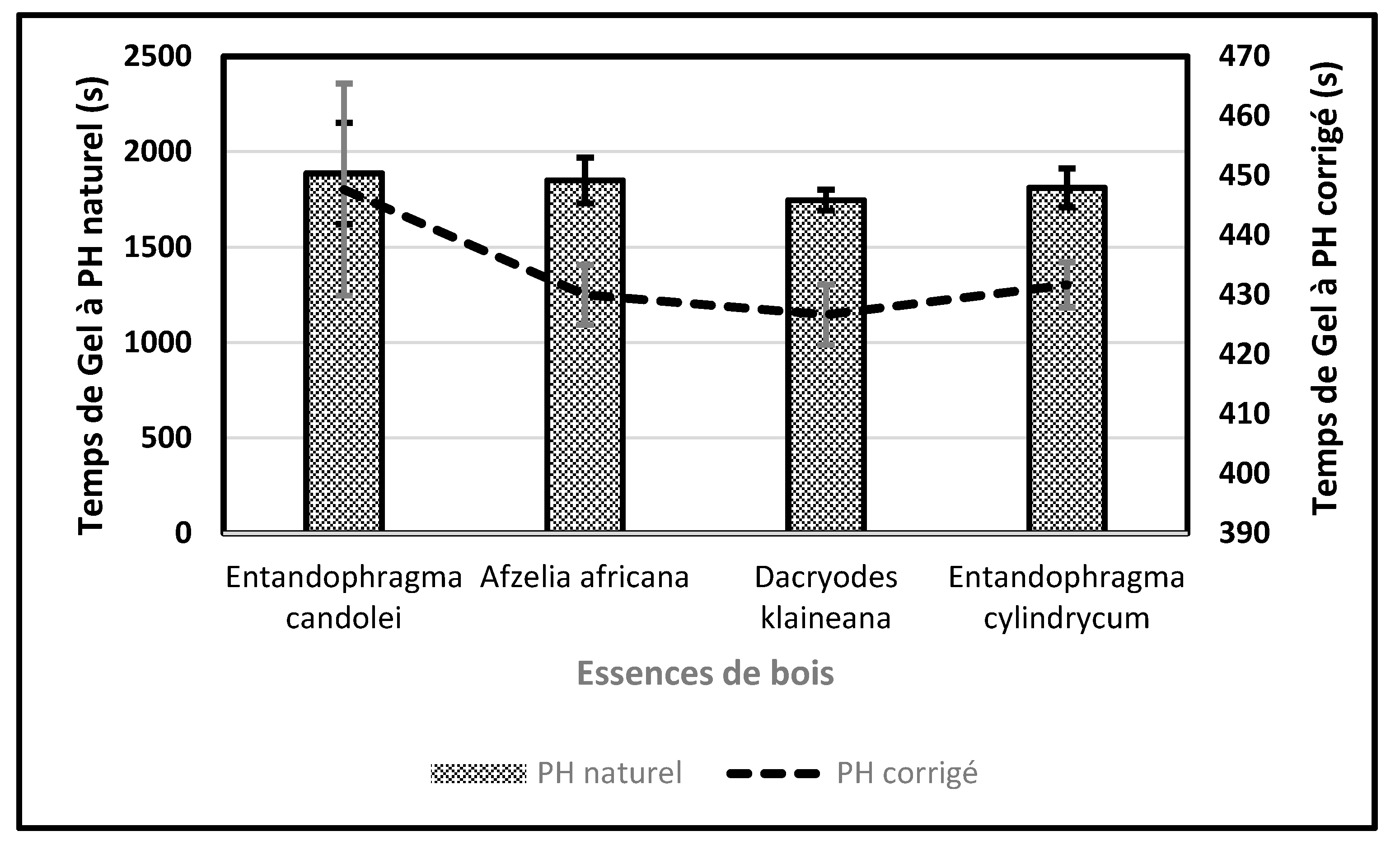

3.7. Comparative Study of Characterized Tannins with Those from Literature

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Romero, R.; Gonzalez, T.; Urbano, B.F.; Segura, C.; Pellis, A.; Vera, M. Exploring tannin structures to enhance enzymatic polymerization. Front. Chem. 2025, 13, 1555202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mneimneh, F.; Haddad, N.; Ramakrishna, S. Recycle and Reuse to Reduce Plastic Waste - A Perspective Study Comparing Petro- and Bioplastics. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2024, 4, 1983–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.K.; Islam, N.; Faruk, O.; Ashaduzzaman; Dungani, R. Review on tannins: Extraction processes, applications and possibilities. South Afr. J. Bot. 2020, 135, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzi, A. Little Secrets for the Successful Industrial Use of Tannin Adhesives: A Review. J. Renew. Mater. 2023, 11, 3403–3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, A.; Contreras, C.; Chiralt, A.; González-Martínez, C. Using tannins as active compounds to develop antioxidant and antimicrobial chitosan and cellulose based films. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2021, 2, 100156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, M.; Fodor, C.; Garcia, Y.; Pereira, E.; Loos, K.; Rivas, B.L. Multienzymatic immobilization of laccases on polymeric microspheres: A strategy to expand the maximum catalytic efficiency. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2020, 137, 49562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzi, A. Tannins: Prospectives and Actual Industrial Applications. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedaïna, A.G.; Pizzi, A.; Nzie, W.; Danwe, R.; Segovia, C.; Kueny, R. Performance of Unidirectional Biocomposite Developed with Piptadeniastrum Africanum Tannin Resin and Urena Lobata Fibers as Reinforcement. J. Renew. Mater. 2021, 9, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, J. , Leyser, E. von, Pizzi, A., Westermeyer, C., & Gorrini, B. (2012). Industrial production of pine tannin-bonded particleboard and Medium-Density Fiberboard (MDF).

- Konai, N.; Pizzi, A.; Raidandi, D.; Lagel, M.; L’hOstis, C.; Saidou, C.; Hamido, A.; Abdalla, S.; Bahabri, F.; Ganash, A. Aningre ( Aningeria spp.) tannin extract characterization and performance as an adhesive resin. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2015, 77, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konai, N.; Raidandi, D.; Pizzi, A.; Meva’a, L. Characterization of Ficus sycomorus tannin using ATR-FT MIR, MALDI-TOF MS and 13C NMR methods. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2017, 75, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntenga, R.; Pagore, F.D.; Pizzi, A.; Mfoumou, E.; Ohandja, L.-M.A. Characterization of tannin-based resins from the barks of Ficus platyphylla and of Vitellaria paradoxa: Composites’ performances and applications. Materials Sciences and Applications 2017, 8, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndiwe, B.; Tibi, B.; Danwe, R.; Konai, N.; Pizzi, A.; Amirou, S. Reactivity, characterization and mechanical performance of particleboards bonded with tannin resins and bio hardeners from African trees. Int. Wood Prod. J. 2020, 11, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konai, N.; Pizzi, A.; Raidandi, D.; Lagel, M.; L’hOstis, C.; Saidou, C.; Hamido, A.; Abdalla, S.; Bahabri, F.; Ganash, A. Aningre ( Aningeria spp.) tannin extract characterization and performance as an adhesive resin. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2015, 77, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konai, N.; Pizzi, A.; Danwe, R.; Lucien, M.; Lionel, K.T. Thermomechanical analysis of African tannins resins and biocomposite characterization. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2020, 35, 1492–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mewoli, A.E.; Segovia, C.; Njom, A.E.; Ebanda, F.B.; Biwôlé, J.J.E.; Xinyi, C.; Ateba, A.; Girods, P.; Pizzi, A.; Brosse, N. Characterization of tannin extracted from Aningeria altissima bark and formulation of bioresins for the manufacture of Triumfetta cordifolia needle-punched nonwovens fiberboards: Novel green composite panels for sustainability. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2023, 206, 117734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njom, A.E.; Voufo, J.; Segovia, C.; Konai, N.; Mewoli, A.; Tapsia, L.K.; Meva'A, J.R.L.; Pizzi, A. Characterization of a composite based on Cissus dinklagei tannin resin. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nga, L.; Ndiwe, B.; Biwolé, A.B.; Pizzi, A.; Biwole, J.J.E.; Mfomo, J.Z. Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization Time of Flight (MALDI-TOF)-Mass Spectrometry and 13C-NMR-Identified New Compounds in Paraberlinia bifoliolata (Ekop-Beli) Bark Tannins. J. Renew. Mater. 2024, 12, 553–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, N.; Karak, N. Tannic acid based bio-based epoxy thermosets: Evaluation of thermal, mechanical, and biodegradable behaviors. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2021, 139, 51792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Hoyos Martinez, P.L.; Merle, J.; Labidi, J.; Charrier-El Bouhtoury, F. Tannins extraction: A key point for their valorization and cleaner production. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 206, 1138–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, H.; Khoukh, A.; Ayed, N.; Charrier, B.; Bouhtoury, F.C.-E. Characterization of Tunisian Aleppo pine tannins for a potential use in wood adhesive formulation. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2014, 61, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, H.; Palmina, K.; Gurshi, A.; Covington, D. Potential of vegetable tanning materials and basic aluminum sulphate in Sudanese leather industry. Journal of Engineering Science and Technology 2009, 4, 20–31. [Google Scholar]

- Tomak, E.D.; Gonultas, O. The Wood Preservative Potentials of Valonia, Chestnut, Tara and Sulphited Oak Tannins. J. Wood Chem. Technol. 2018, 38, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahri, S.; Pizzi, A. Improving soy-based adhesives for wood particleboard by tannins addition. Wood Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Dong, M.; Cui, J.; Gan, L.; Han, S. Exploring the formaldehyde reactivity of tannins with different molecular weight distributions: bayberry tannins and larch tannins. Holzforschung 2019, 74, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafiz, N.L.M.; Tahir, P.M.; Hua, L.S.; Abidin, Z.Z.; Sabaruddin, F.A.; Yunus, N.M.; Abdullah, U.H.; Khalil, H.A. Curing and thermal properties of co-polymerized tannin phenol–formaldehyde resin for bonding wood veneers. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 6994–7001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardeli, J.V.; Fugivara, C.S.; Taryba, M.; Pinto, E.R.; Montemor, M.; Benedetti, A.V. Tannin: A natural corrosion inhibitor for aluminum alloys. Prog. Org. Coatings 2019, 135, 368–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, C.; Selmi, G.; D’aLessandro, O.; Deyá, C. Study of the anticorrosive properties of “quebracho colorado” extract and its use in a primer for aluminum1050. Prog. Org. Coatings 2020, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, A.; Virtanen, V.; Salminen, J.-P.; Leiviskä, T. Aminomethylation of spruce tannins and their application as coagulants for water clarification. Separation and Purification Technology 2020, 242, 116765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Chen, Y.; Xu, G.; Pei, Y. Effective removing of methylene blue from aqueous solution by tannins immobilized on cellulose microfibers. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 129, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndiwe, B.; Pizzi, A.; Tibi, B.; Danwe, R.; Konai, N.; Amirou, S. Extraits d'exsudats d'écorce d'arbres africains en tant que bio-durcisseurs d'adhésifs tanniques thermodurcissables entièrement biosourcés pour panneaux de bois. Industrial crops and products 2019, 132, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete, P.; Pizzi, A.; Pasch, H.; Rode, K.; Delmotte, L. MALDI-TOF and 13C NMR characterization of maritime pine industrial tannin extract. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2010, 32, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, H.; Khoukh, A.; Ayed, N.; Charrier, B.; Charrier-El Bouhtoury, F. Caractérisation des tanins de pin d'Alep tunisien pour une utilisation potentielle dans la formulation d'adhésifs pour bois. Industrial Crops and Products 2014, 61, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoso, A.; Hadi, Y.S.; Pizzi, A.; Lagel, M.-C. Characterization of Merbau Wood Extract Used as an Adhesive in Glued Laminated Lumber. For. Prod. J. 2016, 66, 313–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meunier Quentin, Carl, M., & Jean-Louis, D. (2015). Les Arbres Utiles du Gabon.

- Scalbert, A.; Mila, I.; Expert, D.; Marmolle, F.; Albrecht, A.-M.; Hurrell, R.; Huneau, J.-F.; Tomé, D. Polyphenols, metal ion complexation and biological consequences. Plant Polyphenols 2: Chemistry, Biology, Pharmacology, Ecology, 1999, 545-554.

- Zhou, X.; Segovia, C.; Abdullah, U.H.; Pizzi, A.; Du, G. A novel fiber–veneer-laminated composite based on tannin resin. J. Adhes. 2015, 93, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikoro Bi Athomo, A.; Engozogho Anris, S.P.; Safou Tchiama, R.; Leroyer, L.; Pizzi, A.; Charrier, B. Chemical analysis and thermal stability of African mahogany (Khaya ivorensis A. Chev) condensed tannins. Holzforschung 2020, 74, 683–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athomo, A.B.B.; Anris, S.E.; Safou-Tchiama, R.; Santiago-Medina, F.; Cabaret, T.; Pizzi, A.; Charrier, B. Chemical composition of African mahogany (K. ivorensis A. Chev) extractive and tannin structures of the bark by MALDI-TOF. Industrial crops and products 2018, 113, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amari, M.; Khimeche, K.; Hima, A.; Chebout, R.; Mezroua, A. Synthesis of Green Adhesive with Tannin Extracted from Eucalyptus Bark for Potential Use in Wood Composites. J. Renew. Mater. 2021, 9, 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anris, S.P.E.; Athomo, A.B.B.; Safou-Tchiama, R.; Leroyer, L.; Vidal, M.; Charrier, B. Development of green adhesives for fiberboard manufacturing, using okoume bark tannins and hexamine – characterization by 1H NMR, TMA, TGA and DSC analysis. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2020, 35, 436–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantoja-Castro, M.A.; González-Rodríguez, H. Study by infrared spectroscopy and TGA of tannins and tannic acid. Revista latinoamericana de química 2011, 39, 107–112. [Google Scholar]

- Amirou, S.; Zhang, J.; Essawy, H.; Pizzi, A.; Zerizer, A.; Li, J.; Delmotte, L. Utilization of hydrophilic/hydrophobic hyperbranched poly(amidoamine)s as additives for melamine urea formaldehyde adhesives. Polym. Compos. 2014, 36, 2255–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | Decomposition phases | Final residue (%) | Thermal stability | Remarks | Best performing material |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADB | 3 | 45,05 | High | Good stability up to 600 °C, high carbon retention | ***** |

| DSS | 4 | 43,18 | High | Progressive decomposition, better heat resistance | |

| SPL | 5 | 35,70 | Good | Good thermal resistance, partial combustion | |

| KSP | 3 | 30,80 | Average | Marked thermal decomposition, notable loss | |

| ADBN | 3 | 32,41 | Average | Successful crosslinking but average thermal stability | |

| DSSN | 4 | 31,77 | Thermolabile bonds, significant thermal loss despite crosslinking | ||

| SPLN | 3 | 21,84 | Low | More homogeneous network but low residue | |

| KSPN | 4 | 36,72 | Good | More elaborate polymer network, better crosslinking | **** |

| Trials | 1 | 2 | 3 | pH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Time in second(s) | ||||

| Entandophragma candolei | 1787 | 2188 | 1686 | 6,5 | |

| Afzelia africana | 1810 | 1985 | 1755 | 6,7 | |

| Dacryodes klaineana | 1692 | 1746 | 1802 | 6,4 | |

| Entandophragma cylindrycum | 1929 | 1756 | 1750 | 6,6 | |

| Trials | 1 | 2 | 3 | pH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wood species | Time in second(s) | ||||

| Entandophragma candolei | 440 | 435 | 468 | 11,2 | |

| Afzelia africana | 430 | 425 | 435 | 11,6 | |

| Dacryodes klaineana | 432 | 426 | 422 | 11,3 | |

| Entandophragma cylindrycum | 429 | 436 | 430 | 11,8 | |

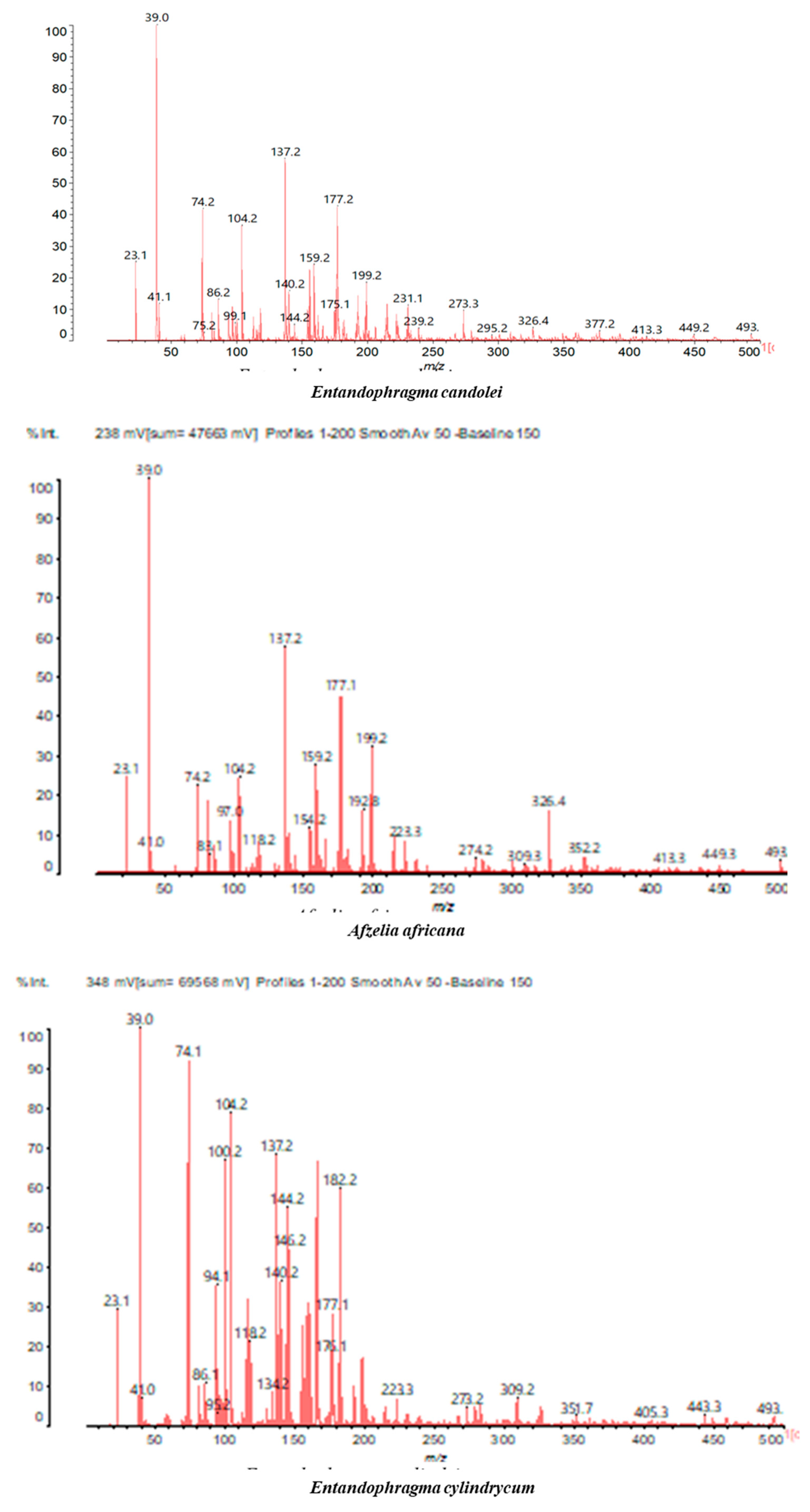

| Species | Part of the tree used | Nature of tannin | Extraction yield (%) | Extraction method | Maximum temperature (Tmax, °C) | Thermomechanical analysis of the resin (MPa) | Gel time | Applications | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tannins from tropical woods | |||||||||

| Paraberlinia bifoliolata | Bark | Condensed | 35% | Hot Extraction in Aqueous Solution | - | 4840 | - | Adhesives for panels and corrosion inhibitors | (Nga et al., 2024) |

| Daniellia oliveri | Bark | Condensed (flavonoids, catechins) | 29% | Hot Extraction in Aqueous Solution | - | 2370#break# | 790 s | Adhesives for Fiberboard | (Konai et al., 2021) |

| Aningre (Aningeria spp) | Bark | Condensed | 19% | Hot Extraction in Aqueous Solution | - | 1191 | - | Resins for particleboard | (Konai et al., 2015) |

| Piptadeniastrum africanum | Bark | Condensed | - | Hot Extraction in Aqueous Solution | - | 3909 | 660 s | Adhesives for Fiberboard | (Wedaïna et al., 2021) |

| Ficus sycomorus | Barks | Condensed | 46%, | Hot Extraction in Aqueous Solution | - | 7050 | 600 s | Adhesives for Fiberboard | (Konai et al., 2021) |

| Butyrospermum parkii | Barks | Condensed | 40%#break# | Hot Extraction in Aqueous Solution | - | 46210 | 701 s | Adhesives for Fiberboard | (Konai et al., 2021) |

| Azadirachta indica | Barks | Condensed | 35%. | Hot Extraction in Aqueous Solution | - | 2650 | 762 s | Adhesives for Fiberboard | (Konai et al., 2021) |

| Ficus platyphylla | Barks | Condensed | - | Hot Extraction in Aqueous Solution | 2091 | - | Adhesives for particleboard | (Ntenga et al., 2017) | |

| Vitellaria paradoxa | Barks | Condensed | - | Hot Extraction in Aqueous Solution | 1989 | - | Adhesives for particleboard | (Ntenga et al., 2017) | |

| Cissus dinklagei | Barks | Condensed | Hot Extraction in Aqueous Solution | 300 °C | 3825 | - | Adhesives for particleboard | (Njom et al., 2024) | |

| Aningeria altissima | Barks | Condensed | 25.52% | Hot Extraction in Aqueous Solution | 325 °C | 5491.77 | 840 -1201 s | Adhesives for Fiberboard | (Mewoli et al., 2023) |

| Gilbertiodendron dewevrei | Barks | Condensed | - | Hot Extraction in Aqueous Solution | - | 1684.95, 6209.24, 2221.33, 7762.31, 3671.42,#break#1930.3 | 523 s, 584 s, 669 s, 744 s, 752 s, 783 s | Adhesives for Fiberboard | (Ndiwe et al., 2020) |

| Commercial tannins | |||||||||

| Pinus maritimus | Bark | Polylavonoide tannin | - | Hot Extraction in Aqueous Solution | - | 2770#break#3050#break#3250#break#3500 | 39s -585s | Adhesives for particleboard | (Navarrete et al., 2013), (Navarrete et al., 2010) |

| Schinopsis balansae | Commercialized | Polylavonoide tannin | Industrial | - | - | 238s | Adhesives for particleboard | (Jorda et al., 2022) | |

| Studied tannins | |||||||||

| Entandophragma candolei | Bark | Condensed | 40 % | Hot Extraction in Aqueous Solution | 340 °C | 3315 | 448s | ||

| Entandophragma cylindricum | Bark | Condensed | 35 % | Hot Extraction in Aqueous Solution | 280 and 310 °C | 5267 | 431s | ||

| Afzelia africana | Bark | Condensed | 33 % | Hot Extraction in Aqueous Solution | 0 and 250°C. | 2363 | 430s | ||

| Dacryodes klaineana | Bark | Condensed | 25 % | Hot Extraction in Aqueous Solution | 525 °C | 3907 | 427s | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).