1. Introduction

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP) are relatively common conditions, complicating up to 10% of pregnancies world-wide [

1]. Accordingly to main guidelines [

2,

3], HPD include: 1) Chronic hypertension, defined as arterial hypertension (AH) occurring before pregnancy or prior to the 20 weeks gestation or the use of antihypertensive therapy before pregnancy; 2) Gestational hypertension (GH), defined as AH arising after the 20th week of gestation, without significant proteinuria; 3) Pre-eclampsia (PE), defined as AH onset after 20 weeks of pregnancy accompanied by proteinuria and/or evidence of maternal acute kidney injury, liver dysfunction, neurological features, hemolysis or thrombocytopenia, and/or fetal growth restriction; 4) Pre-existing AH plus GH superimposed with proteinuria.

In the years following delivery, pregnant women with HDP develop alterations of cardiac structure and function that may lead to a higher incidence of long-term cardiovascular (CV) adverse events, such as myocardial infarction, heart failure, stroke, and death from CV causes [

4,

5,

6].

Literature data suggest that the most vulnerable period for the development of CV events is the first decade following delivery [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11], suggesting that women with previous history of HDP (pHDP) may develop adverse cardiac events before the middle age. For this reason, it is important to recognize eventual abnormalities of cardiac structure and function in pHDP women at an early stage, prior the occurrence of adverse outcomes.

During the last decade, advances in cardiac imaging have led to the introduction of speckle tracking echocardiography (STE), which can allow early detection of subclinical myocardial dysfunction [

12]. Left ventricular (LV) global longitudinal strain (GLS), which is the most commonly used STE-derived deformation index of cardiac contractility, can detect systolic dysfunction much earlier than left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) assessed by conventional transthoracic echocardiography (TTE), thus identifying individuals with subclinical myocardial damage [

13].

Currently, only a few echocardiographic studies [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18] have evaluated LV-GLS by STE in pHDP women, reporting not univocal results. As far as we know, no previous study provided a comprehensive evaluation of all biventricular and biatrial deformation indices in pHDP women.

Considering the increased CV risk of pHDP women during the first decade following delivery [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11], the present study was primarily designed to examine the structure and deformation properties of all cardiac chambers in a cohort of pHDP women compared to a control group of healthy women with previous uncomplicated pregnancy, at 6 yrs postpartum.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Selection

This observational case-control study analyzed a consecutive series of pHDP women compared to a control group of normotensive healthy women, matched by age and body mass index (BMI), between February 2024 and April 2024. The two groups of women underwent delivery at the Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics of San Giuseppe Multimedica IRCCS Hospital (Milano), between February 2017 and May 2018. Approximately one-third of the pHDP women included in the present study participated in our previous investigation focused on left atrial reservoir strain (LASr) assessment in pregnant women with GH [

19].

Inclusion criteria were the following: women with previous history of GH, defined as a new-onset hypertension developing after the 20th week of gestation and/or less than 48 h after delivery [

20]; and/or PE, defined as GH and new-onset proteinuria (≥0.3 g in a complete 24-h urine collection) [

21].

Exclusion criteria were the following: preexisting hypertension or diabetes mellitus, gestational diabetes mellitus, significant comorbidities (cardiovascular disorders, respiratory diseases and/or renal diseases), hemodynamic instability, poor or inadequate echocardiographic acoustic windows (not appropriate for adequate endocardial border definition of both ventricles and atria).

Hypertension criteria included persistent SBP at least 140 mmHg or DBP at least 90 mmHg [

22].

During each clinical visit, each woman underwent three blood pressure (BP) measurements, at intervals of 2 min, using the same arm while sitting at rest for at least 5 min; among the three BP measurements, only the third one was recorded. Moreover, each woman underwent electrocardiogram (ECG), a conventional TTE implemented with complete STE analysis of both ventricles and atria and finally a carotid ultrasonography. All instrumental examinations were carried out by the same cardiologist (A.S.) on the same day, in a blinded manner.

All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of our Institutional Research Committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study protocol was approved by the local Ethics Committee (Committee’s reference number 506/24). A written informed consent was obtained from each patient included in the study.

2.2. Clinical and Instrumental Parameters

Table 1 lists all the clinical and instrumental parameters collected in the two cohorts of women included in the present study and the methods employed for their assessment.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The primary objective of the study was to accurately define biventricular and biatrial myocardial function assessed by STE analysis in pHDP women and to compare these data to those obtained from controls with previous uncomplicated pregnancy, at 6 yrs postpartum.

The secondary objective was to compare the CCA-IMT of pHDP women vs controls with previous uncomplicated pregnancy, over follow-up period.

A sample size calculation was performed for purpose of the study. A sample size of 30 women with previous history of HDP and 30 healthy controls reached 80% of statistical power to detect a two-point difference in the GLS magnitude (i.e., 20% vs 18%) measured at 6 yrs postpartum in the two groups of women with a standard deviation of 2.5 for each parameter, using a two-sided equal-variance t-test with a level of significance (alpha) of 5%.

Normality of the distribution of continuous variables was tested using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Normally distributed variables were summarized as mean ± standard deviation, while not normally distributed data were expressed as median with data range (minimum to maximum). The difference between means was estimated by an independent two-tailed t-test for normally distributed variables, whereas the Mann-Whitney test was used to compare the means from paired samples for non-normally distributed variables. Categorical variables were compared using chi-squared test.

Cox regression analyses were performed to identify the independent predictors of subclinical myocardial dysfunction (defined as a LV-GLS value <20%) [

38] and subclinical carotid atherosclerosis (defined as CCA-IMT ≥0.7 mm) [

45] in pHDP women, over follow-up period. According to the one in ten rule (one predictive variable for every ten events), only the following variables were included in the Cox regression analyses: third trimester age, third trimester BMI and previous PE for both outcomes, chronic antihypertensive treatment (for the primary outcome only) and current HDL-cholesterol (for the secondary outcome only).

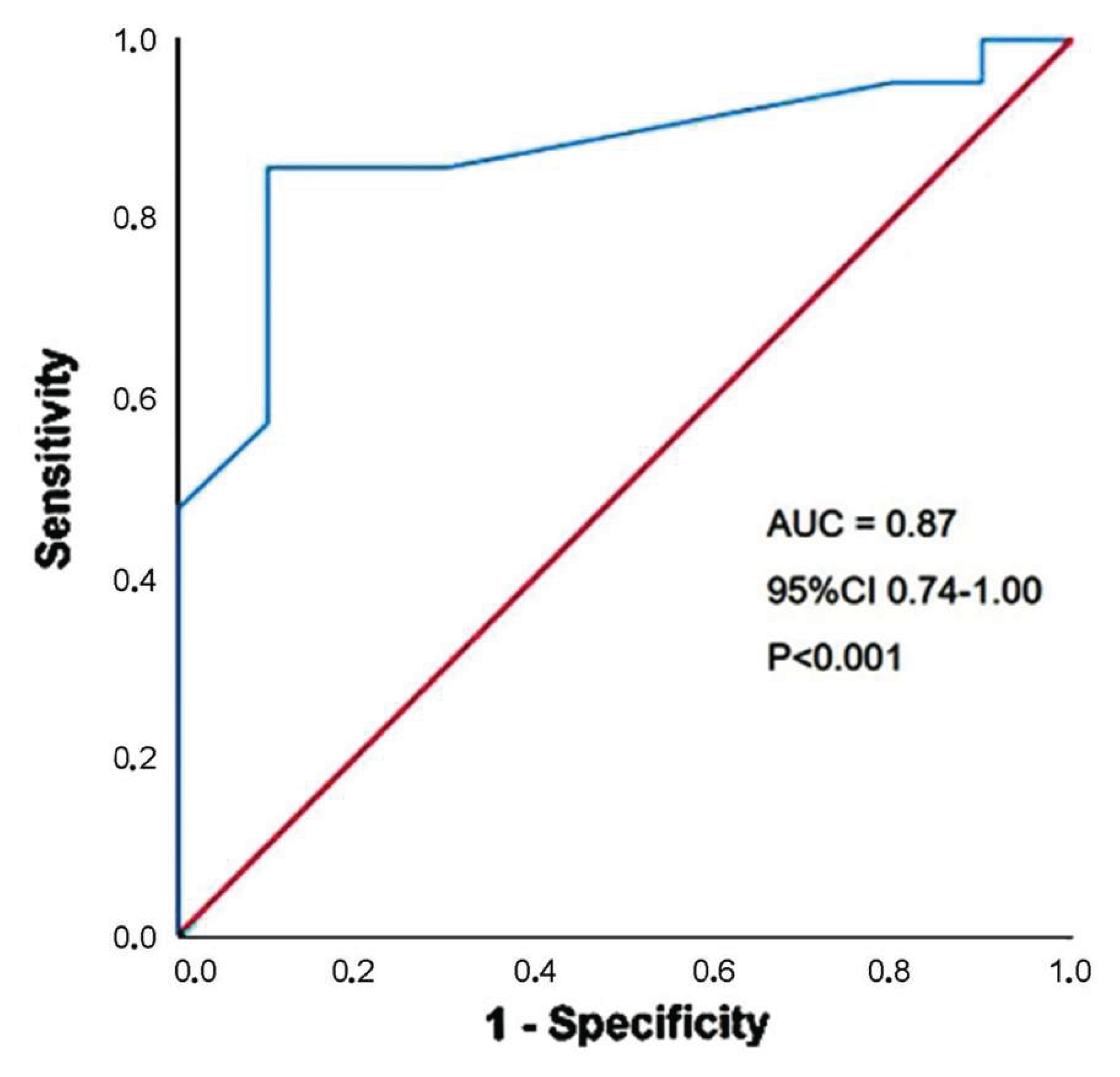

The receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve analysis was performed to establish the sensitivity and the specificity of the main statistically significant continuous variable for predicting the secondary outcome over follow-up period. Area under curve (AUC) was estimated.

A detailed intra-observer and inter-observer variability analysis of LV-GLS assessment by 2D-STE was conducted in a subgroup of 15 randomly selected pHDP women. LV-GLS was remeasured by the same cardiologist who performed all echocardiographic examinations (A.S.) and by a second one (M.L.). The analyses were performed in a blinded manner. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) with its 95% CI was used as a statistical method for assessing intra-observer and inter-observer measurement variability. An ICC of 0.70 or more was considered to indicate acceptable reliability.

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS version 28 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). The null hypothesis was rejected for 2-tailed values of p<0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Findings

A total of 31 pHDP women and 30 age- and BMI-matched healthy controls without pHDP were analyzed at 6 yrs postpartum.

Main clinical, obstetrical, hemodynamic and laboratory parameters collected in the two study groups at the third trimester of pregnancy are summarized in

Table 2.

Both groups of women were mostly caucasian, aged ≥35 yrs. More than half of pHDP women (58.1%) had a family history of hypertension, one-third (32.3%) suffered from dyslipidemia and two-third (61.3%) had a pregnancy complicated by PE. All cases of PE were diagnosed at or after 34 weeks of gestation. Compared to controls, pHDP women underwent delivery much earlier than controls. The great majority of pHDM women (87.1%) were treated with antihypertensive drugs during pregnancy, particularly calcium channel blockers and alpha2-agonists, whereas alpha-beta blockers were less commonly prescribed.

At 6 yrs postpartum, a low prevalence of smoking and type 2 diabetes was observed in the two groups of women. Dyslipidemia and obesity were more frequently detected in pHDP women than controls. Among pHDP women, 10 (32.3%) made regular use of antihypertensive drugs and 11 (35.5%) were found with PA ≥140/90 mmHg at clinical visit. Among pHDP women on anti-hypertensive therapy, 3 (30%) had uncontrolled hypertension at clinical visit. Finally, among pHDP women with PA ≥140/90 mmHg at clinical visit, 8 (72.7%) were not on anti-hypertensive treatment (

Table 3).

3.2. Instrumental Findings

Table 4 lists all morphological, functional and hemodynamic parameters assessed by conventional TTE and carotid ultrasonography in the two groups of women at 6 yrs postpartum.

On TTE examination, biventricular and biatrial cavity sizes were similar in the two groups of women. Even in absence of manifest pathological LV remodeling, pHDP women were diagnosed with significantly greater RWT and LVMi than controls. LV systolic function, assessed by LVEF, was normal in both groups of women. Analysis of LV diastolic function revealed a significantly lower E/A ratio and a significantly higher E/average e’ ratio in pHDP women in comparison to controls. No significant valvulopathy was detected in both study groups. The assessment of pulmonary hemodynamics showed that both TAPSE and TAPSE/sPAP ratio were significantly reduced in women with previous HDP than controls. Finally, aortic root was significantly larger in pHDP women.

The analysis of hemodynamic indices showed that SV was significantly lower in pHDP women than controls, whereas heart rate and CO were similar in the two groups of women. In addition, TPRi were significantly increased in pHDP women.

Concerning VAC parameters, pHDP women were found with significantly higher EaI than controls, while EesI was similar in the two groups of women; the resultant VAC (EaI/EesI ratio) did not statistically differ between the two study groups.

On carotid ultrasonography, the average values of CCA-IMT, CCA-RWT and CCA-CSA were all significantly larger in pHDP women than controls.

Strain echocardiographic imaging revealed that the great majority of biventricular and biatrial myocardial strain and strain rate parameters were significantly impaired in pHDP women. Notably, LV-GLS, RV-GLS, LASr and RASr absolute values were significantly lower in pHDP women than controls, whereas LV-GCS magnitude was similar in the two groups of women. The impairment in both LASr and RASr was primarily related to a reduction in LA and right atrial (RA) conduit longitudinal strain; on the other hand, LA and RA contractile longitudinal strain was preserved in both groups of women. Overall, more than half of pHDP women were diagnosed with lower biventricular and biatrial myocardial strain parameters in comparison to the accepted reference values [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]. Interestingly, approximately one-fifth of heathy controls were found with a mild attenuation of myocardial deformation indices (

Table 5).

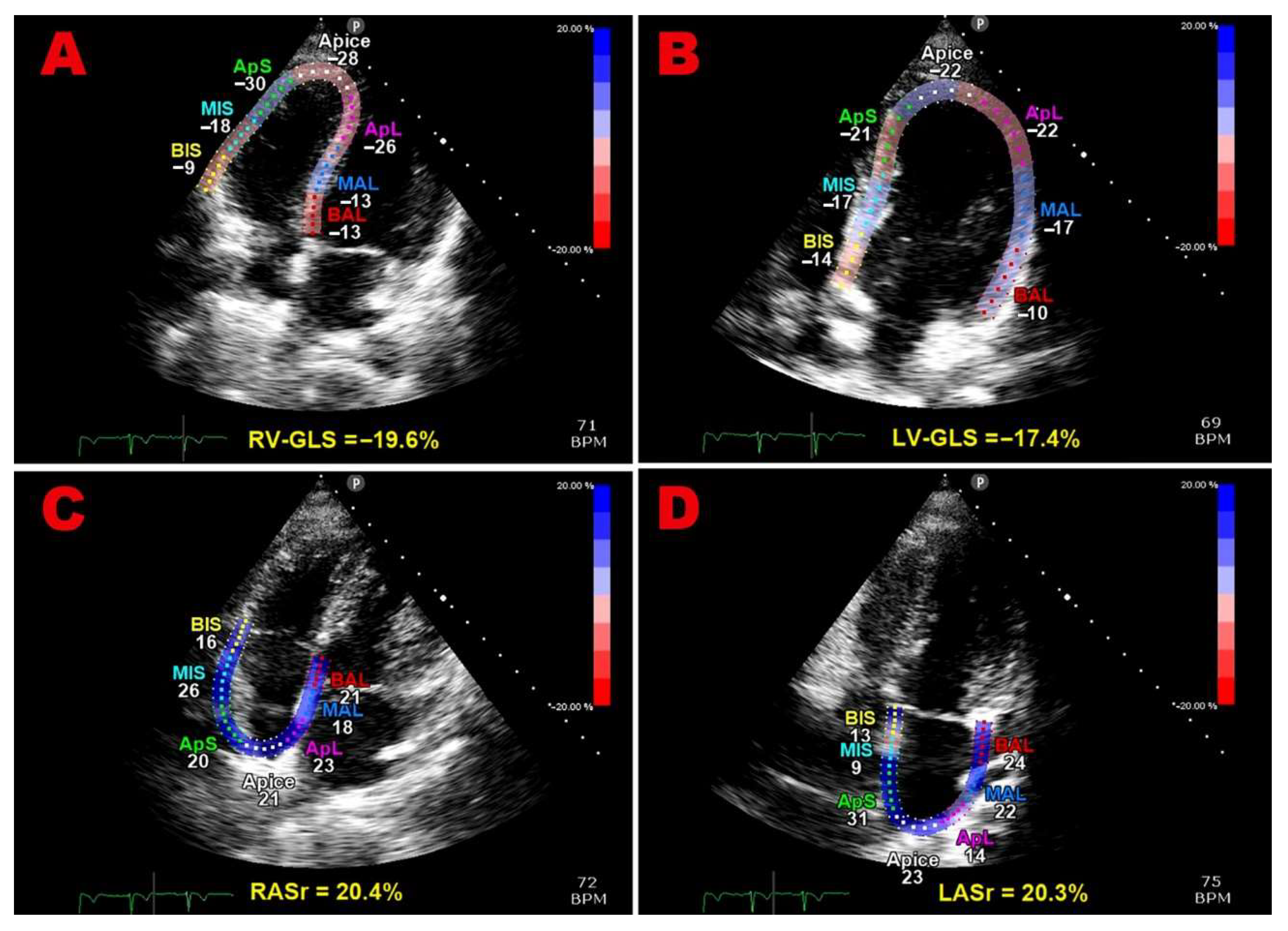

Multipanel

Figure 1 illustrates examples of biventricular and biatrial longitudinal strain parameters measured from the apical four-chamber view in a pHDP woman included in the present study.

3.3. Follow-Up Data

Mean follow-up period after delivery was 6.1 ± 1.3 yrs. During this period, no pHDP woman developed any symptoms and signs of cardiomyopathy. No major adverse CV event was recorded.

However, more than half of pHDP women (58.1% of total) had a subclinical myocardial dysfunction revealed by STE analysis and were found with persistent AH at 6 yrs postpartum. Nine pHDP women (29%) had both persistent LV-GLS attenuation and chronic AH over follow-up period. Moreover, 21 pHDP women (67.7%) had subclinical carotid atherosclerosis.

On Cox regression analysis performed for identifying the independent predictors of subclinical myocardial dysfunction, defined by a LV-GLS magnitude <20% [

38], at 6 yrs postpartum, only previous PE (HR 4.01, 95% CI 1.05-15.3,

p = 0.03) resulted to be independently associated with the primary outcome (

Table 6).

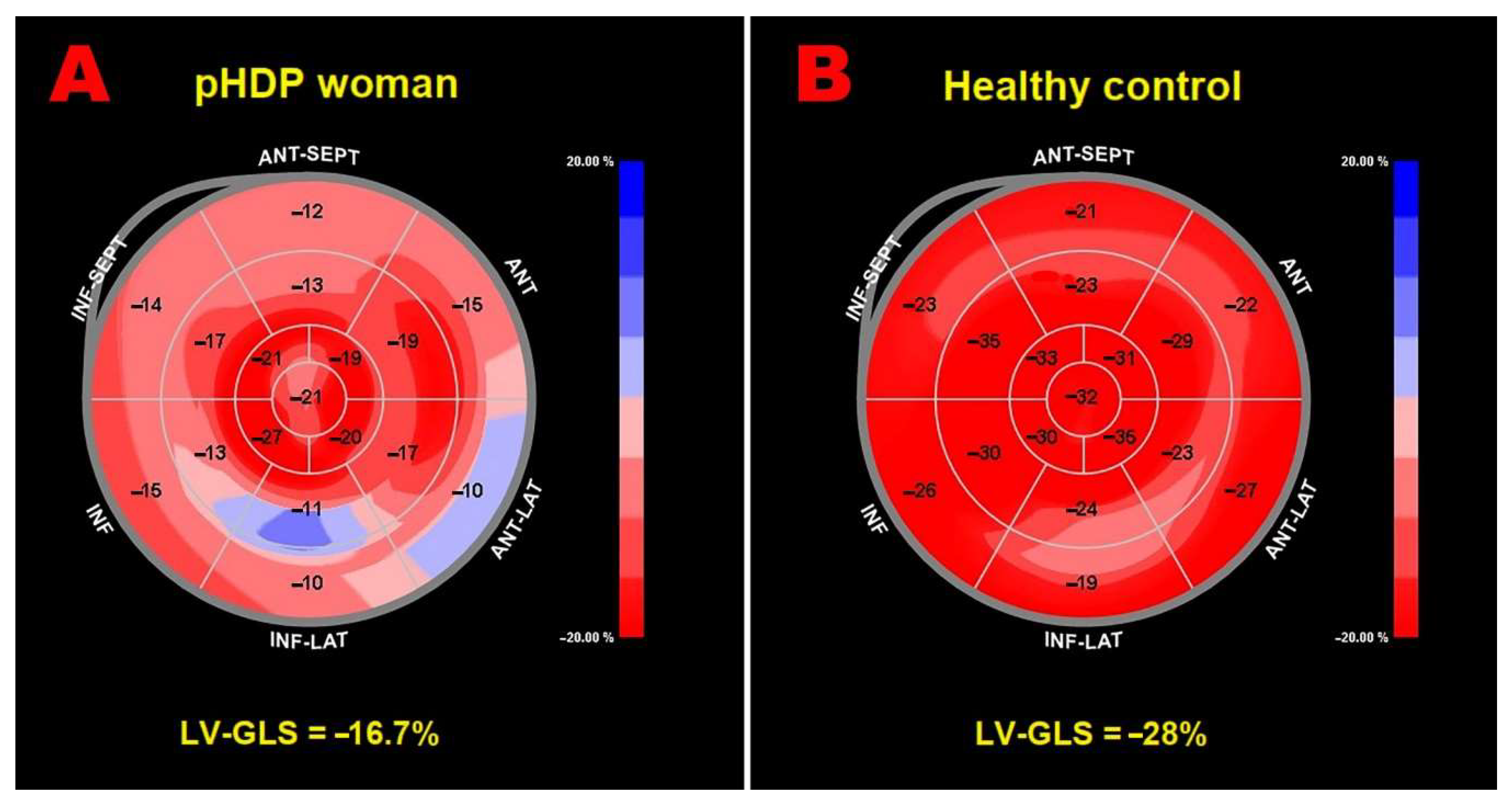

Figure 2 illustrates examples of LV-GLS bull’’s-eye plots obtained in a pHDP women with third trimester BMI >27 Kg/m

2 and pregnancy complicated by PE (Panel A) and in a woman with previous uncomplicated pregnancy (Panel B), respectively.

On Cox regression analysis performed for identifying the independent predictors of subclinical carotid atherosclerosis at the 6-year follow-up, third trimester BMI (HR 1.21, 95% CI 1.07-1.38,

p = 0.003) and PE (HR 6.38, 95% CI 1.50-27.2,

p = 0.01) were independently associated with the secondary outcome (

Table 7).

A third trimester BMI >27 Kg/m

2 had 86% sensitivity and 90% specificity (AUC = 0.87; 95% CI 0.74-1.00,

p = 0.004) for predicting the secondary outcome (

Figure 3).

3.4. Measurement Variability

A detailed intra- and inter-observer variability analysis of LV-GLS assessment was conducted in a group of 15 randomly selected pHDP women. Intra- and inter-observer agreement between the raters, expressed as ICCs, was 0.97 (95% CI 0.91-0.99) and 0.92 (95% CI 0.78-0.97), respectively.

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings of the Present Study

This observational case-control study demonstrated that, compared to healthy women with previous uncomplicated pregnancy, pHDP women showed: 1) a subtle LV remodeling characterized by greater RWT and LVMi, with no evidence of LV concentric remodeling or LV concentric hypertrophy; 2) a slight reduction in the E/A ratio and a concomitant increase in the E/average e’ ratio, with no evidence of significant increase in LVFP; 3) lower TAPSE and TAPSE/sPAP ratio, without pathological RV-PA uncoupling (defined as TAPSE/sPAP ratio <0.80) [

27]; 4) higher arterial elastance, even if still falling within the normal range [

46]; 5) early carotid artery remodeling with greater CCA-IMT, CCA-RWT and CCA-CSA. Despite normal LVEF on conventional TTE, 2D-STE analysis highlighted a significant impairment in most biventricular and biatrial myocardial strain parameters in pHDP women vs. controls. No relevant CV event was recorded over the 6 yrs postpartum. However, more than half of pHDP women showed subclinical myocardial dysfunction on strain echocardiographic imaging and were found with early subclinical atherosclerosis at 6 yrs postpartum. In our findings, PE was independently associated with 4- and 6-fold increased risk of developing subclinical myocardial dysfunction and early carotid atherosclerosis, respectively, at 6-yrs postpartum. In addition, a previous pregnancy complicated by overweight or obesity, as expressed by a third trimester BMI >27 Kg/m

2, independently predicted the secondary outcome.

4.2. Comparison with Previous Studies and Interpretation of Results

Our findings were consistent with previous studies conducted on pHDP women, revealing an early impairment in LV-GLS assessed by STE analysis. In particular, Clemmensen TS et al. [

14] observed that women with a previous history of early onset PE were more likely to have subclinical impairment of LV function 12 years after PE than those with a history of late onset PE and healthy controls; LV-GLS showed the strongest association with early onset PE. Boardman H et al. [

15], examining 103 women with pHDP and 70 women with normotensive pregnancy, at 5 to 10 years after pregnancy, found that those with pHDP had a distinct cardiac geometry with higher LVMi, LAVi and LVEF but lower E/A ratio and LV-GLS. Levine LD et al. [

16] found that pHDP women who developed hypertension had greater LV remodeling, including greater RWT, worse diastolic function, lower LV-GLS and higher effective arterial elastance, than patients without hypertension; subclinical myocardial dysfunction was primarily ascribed by the authors to hypertension development, regardless of HDP history. Gronningsaeter L et al. [

17] detected sustained hypertension, higher LV mass and reduced LV systolic and diastolic function 7 yrs after severe PE. Conversely, Al-Nashi M et al. [

18], assessing cardiac function and ventricular-arterial interaction in 15 women 11 years after pregnancy with PE compared to 16 matched controls with normal pregnancy, did not detect persistent alterations in cardiac function, or in ventricular-arterial interaction in women con previous history of PE.

Differently from the above-mentioned studies, the present study did not evaluate only LV-GLS but performed a comprehensive assessment of myocardial deformation properties of all cardiac chambers in pHDP women. Subclinical myocardial dysfunction involved both ventricles and atria, with sparing of LV strain in circumferential direction. This finding might be primarily interpreted as a compensatory increase in circumferential fiber function in the setting of decreased longitudinal fiber function, in order to preserve global LV systolic function. Moreover, impairment of LV-GLS, that is attributed to the endocardial layer of the myocardium, commonly precedes the alterations of circumferential strain, which is attributed to the mid-wall layer [

47].

Our results confirmed the superiority of strain echocardiographic imaging over conventional TTE in detecting a subclinical impairment in myocardial deformation indices, in absence of any signs and symptoms of cardiomyopathy and in the presence of a preserved LVEF (≥55%) [

12].

From a pathophysiological point of view, the attenuation of myocardial deformation indices detected in pHDP women may be related to the detrimental impact of a chronically increased afterload on cardiac function, as demonstrated in large cohorts of hypertensive individuals [

48].

The increased LV afterload, noninvasively quantified by measuring the effective arterial elastance (ESP/SVi ratio), can cause a subtle LV and LA remodeling with mild decline in diastolic function and early reduction in myocardial strain of left-sided cardiac chambers [

49]. A concomitant increase in RV afterload, expressed by TAPSE/sPAP ratio impairment, may be responsible for the attenuation of deformation properties of right-sided cardiac chambers [

50].

The concomitance of common metabolic risk factors, such as overweight/obesity, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia, may increase the level of myocardial fibrosis and stiffening, thus reducing biventricular and biatrial myocardial strain magnitude [

51,

52].

The attenuation of myocardial deformation indices detected in more than half of pHDP women and in approximately one-fifth of healthy controls may also be explained by the potential influence exerted by anthropometrics, such as a concave-shaped chest wall conformation, abdominal and/or thoracic adiposity on biventricular and biatrial mechanics [

53,

54]. Indeed, it is not possible to exclude that a “cardiac restriction” due to a narrow antero-posterior thoracic diameter and/or compressive phenomena may have contributed to reduce myocardial deformation indices, particularly at basal level, in some pHDP women and/or healthy controls. However, this methodological issue was not investigated in the present study.

Consistent with previous studies [

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60], we also detected an increased atherosclerotic load, expressed by greater CCA-IMT, CCA-RWT and CCA-CSA in pHDP women, at 6-yrs postpartum. Several pathophysiologic mechanisms may explain the association between PE and subsequent occurrence of early carotid atherosclerosis, particularly in the first decade following delivery. Firstly, it is likely that HDP and subsequent CV disease have a common burden of risk factors and are both clinical manifestations of the same pathophysiologic process at different times in a woman’’s life. This hypothesis is supported by the strong association between HDP and a number of typical CV risk factors, including chronic hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and increased BMI, as demonstrated by previous Authors [

61]. Moreover, the positive association between HDP and later life BP, BMI, and lipid levels may be largely favoured by prepregnancy CV risk factors [

62]. In addition, placental lesions commonly detected in women with PE, that are similar to features of early-stage atherosclerotic plaques [

63], may be an early expression of susceptibility to vascular impairments later in life [

64]. Subclinical carotid atherosclerosis might also be the result of endothelial dysfunction generated by HDP that persists after delivery, as demonstrated by elevated markers of endothelial dysfunction [

65] and systemic inflammation [

66] up to 8 years after pregnancies complicated by PE.

The prognostic relevance of PE revealed by our results was consistent with previous findings from large cohort studies. Notably, Kestenbaum B et al. [

8], in a study examining hospitalizations due to CV events, showed that women with GH, mild PE, and severe PE had 2.8-fold, 2.2-fold, and 3.3-fold increased risk of CV events, respectively, over a mean follow-up of 7.8 years. Cain MA et al. [

9], in a retrospective cohort study of >300 000 women, found that PE was associated with a 42% greater risk of CV disease within the first 5 years postpartum, even after adjusting for demographic, socioeconomic, and other CV risk factor. Egeland GM et al. [

10] found that PE and GH were associated with 6- and 7-fold increased risk of pharmacologically treated hypertension, respectively, within 10 years of delivery. Jarvie JL et al. [

11], analyzing nearly 1.5 million records from delivering mothers of singleton infants, found that, compared with women without previous HDP, pHDP women had a roughly 2.4-fold greater adjusted odds of hospitalization due to CV causes within 3 years of delivery, especially the african american ones. Finally, Levine LD et al. [

16] found a 2.4-fold increased risk of hypertension 10 years after HDP.

4.3. Implications for Clinical Practice

Considering that HDPs, particularly PE, are associated with increased risk of subclinical myocardial dysfunction and early carotid atherosclerosis within the first decade from delivery, the most recent guidelines and scientific consensus documents recommend accurate screening of women at risk and application of CV prevention strategies [

67].

Primary prevention of CV disease should begin early in the postpartum period and continue throughout the pHDP woman’’s life. A correct approach should involve an immediate postpartum visit, assessment of risk factors, and multidisciplinary lifestyle intervention at 6–12 weeks and 1 year postpartum, followed by an annual follow-up visit and a final assessment at 50 years of age [

68].

In light of our findings, strain echocardiographic imaging should be considered for implementation in clinical practice, particularly during pregnancies complicated by PE and during the first decade postpartum. This innovative methodology provides incremental diagnostic and prognostic information on biventricular and biatrial mechanics, over conventional TTE examination. Both subtle changes in myocardial deformation indices and subclinical carotid atherosclerosis detected in pHDP women might suggest the clinicians to early initiate and/or uptitrate pharmacological therapies, together with nonpharmacological treatments, such as hypocaloric diet and weight loss, in order to prevent the future occurrence of adverse CV events.

4.4. Limitations of the Study

Main limitations of the present study were its monocentric nature and the limited number of pHDP women analyzed. However, the number of pHDP women included was justified by an accurate sample size calculation. Moreover, our study group did not undergo conventional and functional echocardiographic measurements before pregnancy to establish whether the impairment in biventricular and biatrial deformation indices preceded the onset of GH and/or PE. In addition, biventricular and biatrial myocardial deformation indices were obtained by using the same software employed for LV-GLS assessment, the only one available at our Institution. It is noteworthy that strain echocardiographic imaging suffers from a number of limitations, such as its dependence on good image quality, on frame rates (generally, no less than 40 fps), on operator’s experience, on loading conditions, on ultrasound system employed for the analysis and on chest wall conformation [

69,

70,

71,

72]. Finally, pHDP women included in the present study did not perform blood tests, comprehensive of C-reactive protein, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR), not foreseen in the research protocol. These inflammatory, hemodynamic and metabolic markers would have contributed to better understand the pathophysiological mechanisms of both cardiac and carotid artery remodeling detected in pHDP women at 6-yrs postpartum.

5. Conclusions

Women with previous history of PE have a significantly increased risk of subclinical myocardial dysfunction and early carotid atherosclerosis at 6-yrs postpartum.

Strain echocardiographic imaging should be considered for implementation in clinical practice for early identifying, among pHDP women, those with subclinical myocardial dysfunction, who might benefit from a more aggressive antihypertensive treatment and/or a closer clinical follow-up, aimed at reducing the risk of CV complications later in life.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S., F.N. and C.L.; methodology, A.S., F.N., C.L. and R.D.A.; software, A.S.; validation, S.B., M.L. and S.H.; formal analysis, A.S.; investigation, A.S., F.N., G.L.N and C.L.; resources, A.S., S.B., S.H. and C.L.; data curation, A.S., F.N., R.D.A., G.L.N. and C.L.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.; writing—review and editing, F.N., C.L. and G.L.N.; visualization, G.L.N., M.L. and S.H.; supervision, S.B., M.L. and S.H.; project administration, S.H. and C.L.; funding acquisition, A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Italian Ministry of Health, Ricerca Corrente IRCCS MultiMedica.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Comitato Etico Territoriale Lombardia 5 (Committee’s reference number 506/24), date of approval 22 October 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data extracted from included studies will be publicly available on Zenodo (

https://zenodo.org) (accessed on 7 June 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Monica Fumagalli for her graphical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

2D, two-dimensional; AH, arterial hypertension; AUC, area under curve; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; BSA, body surface area; CCA, common carotid artery; CO, cardiac output; CSA, cross-sectional area; CV, cardiovascular; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; EaI, arterial elastance indexed; ECG, electrocardiogram; EDD, end-diastolic diameter; EesI, end-systolic elastance indexed; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESP, end-systolic pressure; FWLS, free wall longitudinal strain; GCS, global circumferential strain; GLS, global longitudinal strain; GH, gestational hypertension; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; HDP, Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy; HOMA-IR, Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; IMT, intima-media thickness; IVC, inferior vena cava; LA, left atrial; LAScd, left atrial conduit strain; LASct, left atrial contractile strain; LASr, left atrial reservoir strain; LAVi, left atrial volume indexed; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; LV, left ventricular; LVEDVi, left ventricular end-diastolic volume indexed; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESVi, left ventricular end-systolic volume indexed; LVMi, left ventricular mass indexed; MAP, mean arterial pressure; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide; PA, pulmonary artery; PE, pre-eclampsia; pHDP, previous hypertensive disorder of pregnancy; PP, pulse pressure; RA, right atrial; RASr, right atrial reservoir strain; ROC, receiver operating characteristics; RV, right ventricular; RVIT, right ventricular inflow tract; RWT, relative wall thickness; sPAP, systolic pulmonary artery pressure; SVi, stroke volume indexed; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion; TPRi, total peripheral resistance index; TRV, tricuspid regurgitation velocity; SBP, systolic blood pressure; STE, speckle tracking echocardiography; TTE, transthoracic echocardiography; VAC, ventricular-arterial coupling.

References

- Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2019 Jun 25.

- Regitz-Zagrosek, V.; Roos-Hesselink, J.W.; Bauersachs, J.; Blomström-Lundqvist, C.; Cífková, R.; De Bonis, M.; Iung, B.; Johnson, M.R.; Kintscher, U.; Kranke, P.; et al. 2018 ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 3165-3241. [CrossRef]

- Gestational Hypertension and Preeclampsia: ACOG Practice Bulletin; Number 222. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 135, e237-e260. [CrossRef]

- Maas, A.H.E.M.; Rosano, G.; Cifkova, R.; Chieffo, A.; van Dijken, D.; Hamoda, H.; Kunadian, V.; Laan, E.; Lambrinoudaki, I.; Maclaran, K.; et al. Cardiovascular health after menopause transition; pregnancy disorders; and other gynaecologic conditions: a consensus document from European cardiologists; gynaecologists; and endocrinologists. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 967-984. [CrossRef]

- Grandi, S.M.; Filion, K.B.; Yoon, S.; Ayele, H.T.; Doyle, C.M.; Hutcheon, J.A.; Smith, G.N.; Gore, G.C.; Ray, J.G.; Nerenberg, K.; et al. Cardiovascular Disease-Related Morbidity and Mortality in Women With a History of Pregnancy Complications. Circulation 2019, 139, 1069-1079. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.X.; Arvizu, M.; Rich-Edwards, J.W.; Wang, L.; Rosner, B.; Stuart, J.J.; Rexrode, K.M.; Chavarro, J.E. Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy and Subsequent Risk of Premature Mortality. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, 1302-1312. [CrossRef]

- Ying, W.; Catov, J.M.; Ouyang, P. Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy and Future Maternal Cardiovascular Risk. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e009382. [CrossRef]

- Kestenbaum, B.; Seliger, S.L.; Easterling, T.R.; Gillen, D.L.; Critchlow, C.W.; Stehman-Breen, C.O.; Schwartz, S.M. Cardiovascular and thromboembolic events following hypertensive pregnancy. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2003, 42, 982-9. [CrossRef]

- Cain, M.A.; Salemi, J.L.; Tanner, J.P.; Kirby, R.S.; Salihu, H.M.; Louis, J.M. Pregnancy as a window to future health: maternal placental syndromes and short-term cardiovascular outcomes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 215, 484.e1-484.e14. [CrossRef]

- Egeland, G.M.; Skurtveit, S.; Staff, A.C.; Eide, G.E.; Daltveit, A.K.; Klungsøyr, K.; Trogstad, L.; Magnus, P.M.; Brantsæter, A.L.; Haugen, M. Pregnancy-Related Risk Factors Are Associated With a Significant Burden of Treated Hypertension Within 10 Years of Delivery: Findings From a Population-Based Norwegian Cohort. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018, 7, e008318. [CrossRef]

- Jarvie, J.L.; Metz, T.D.; Davis, M.B.; Ehrig, J.C.; Kao, D.P. Short-term risk of cardiovascular readmission following a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy. Heart 2018, 104, 1187-1194. [CrossRef]

- Luis, S.A.; Chan, J.; Pellikka, P.A. Echocardiographic Assessment of Left Ventricular Systolic Function: An Overview of Contemporary Techniques; Including Speckle-Tracking Echocardiography. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2019, 94, 125-138. [CrossRef]

- Voigt, J.U.; Cvijic, M. 2- and 3-Dimensional Myocardial Strain in Cardiac Health and Disease. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2019, 12, 1849-1863. [CrossRef]

- Clemmensen, T.S.; Christensen, M.; Kronborg, C.J.S.; Knudsen, U.B.; Løgstrup, B.B. Long-term follow-up of women with early onset pre-eclampsia shows subclinical impairment of the left ventricular function by two-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2018, 14, 9-14. [CrossRef]

- Boardman, H.; Lamata, P.; Lazdam, M.; Verburg, A.; Siepmann, T.; Upton, R.; Bilderbeck, A.; Dore, R.; Smedley, C.; Kenworthy, Y.; et al. Variations in Cardiovascular Structure; Function; and Geometry in Midlife Associated With a History of Hypertensive Pregnancy. Hypertension 2020, 75, 1542-1550. [CrossRef]

- Levine, L.D.; Ky, B.; Chirinos, J.A.; Koshinksi, J.; Arany, Z.; Riis, V.; Elovitz, M.A.; Koelper, N.; Lewey, J. Prospective Evaluation of Cardiovascular Risk 10 Years After a Hypertensive Disorder of Pregnancy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2022, 79, 2401-2411. [CrossRef]

- Gronningsaeter, L.; Skulstad, H.; Quattrone, A.; Langesaeter, E.; Estensen, M.E. Reduced left ventricular function and sustained hypertension in women seven years after severe preeclampsia. Scand. Cardiovasc. J. 2022, 56, 292-301. [CrossRef]

- Al-Nashi, M.; Eriksson, M.J.; Östlund, E.; Bremme, K.; Kahan, T. Cardiac structure and function; and ventricular-arterial interaction 11 years following a pregnancy with preeclampsia. J. Am. Soc. Hypertens. 2016, 10, 297-306. [CrossRef]

- Sonaglioni, A.; Lonati, C.; Lombardo, M.; Rigamonti, E.; Binda, G.; Vincenti, A.; Nicolosi, G.L.; Bianchi, S.; Harari, S.; Anzà, C. Incremental prognostic value of global left atrial peak strain in women with new-onset gestational hypertension. J. Hypertens. 2019, 37, 1668-1675. [CrossRef]

- Sjaus, A.; McKeen, D.M.; George, R.B. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Can. J. Anaesth. 2016, 63, 1075-97. English. [CrossRef]

- Magee, L.A.; Pels, A.; Helewa, M.; Rey, E.; von Dadelszen, P.; Canadian Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy (HDP) Working Group. Diagnosis; evaluation; and management of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2014, 4, 105-45. [CrossRef]

- Casiglia, E. AND; OR; AND/OR in hypertension guidelines. J. Hypertens. 2024, 42, 934-935. [CrossRef]

- Levey, A.S.; Bosch, J.P.; Lewis, J.B.; Greene, T.; Rogers, N.; Roth, D. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann. Intern. Med. 1999, 130, 461-70. [CrossRef]

- Lang, R.M.; Badano, L.P.; Mor-Avi, V.; Afilalo, J.; Armstrong, A.; Ernande, L.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Foster, E.; Goldstein, S.A.; Kuznetsova, T.; et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2015, 28, 1-39.e14. [CrossRef]

- Nagueh, S.F.; Smiseth, O.A.; Appleton, C.P.; Byrd, B.F. 3rd; Dokainish, H.; Edvardsen, T.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Gillebert, T.C.; Klein, A.L.; Lancellotti, P.; et al. Recommendations for the Evaluation of Left Ventricular Diastolic Function by Echocardiography: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2016, 29, 277-314. [CrossRef]

- Humbert, M.; Kovacs, G.; Hoeper, M.M.; Badagliacca, R.; Berger, R.M.F.; Brida, M.; Carlsen, J.; Coats, A.J.S.; Escribano-Subias, P.; Ferrari, P.; et al. 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2023, 61, 2200879. [CrossRef]

- Tello, K.; Wan, J.; Dalmer, A.; Vanderpool, R.; Ghofrani, H.A.; Naeije, R.; Roller, F.; Mohajerani, E.; Seeger, W.; Herberg, U.; et al. Validation of the Tricuspid Annular Plane Systolic Excursion/Systolic Pulmonary Artery Pressure Ratio for the Assessment of Right Ventricular-Arterial Coupling in Severe Pulmonary Hypertension. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2019, 12, e009047. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Sun, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, X.; Liu, S.; Li, J.; Xu, C.; Hu, D.; Sun, Y. Pulse pressure and mean arterial pressure in relation to ischemic stroke among patients with uncontrolled hypertension in rural areas of China. Stroke 2008, 39, 1932-7. [CrossRef]

- Franklin, S.S.; Wong, N.D. Pulse Pressure: How Valuable as a Diagnostic and Therapeutic Tool? J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 67, 404-406. [CrossRef]

- Sattin, M.; Burhani, Z.; Jaidka, A.; Millington, S.J.; Arntfield, R.T. Stroke Volume Determination by Echocardiography. Chest 2022, 161, 1598-1605. [CrossRef]

- Hill, L.K.; Sollers Iii, J.J.; Thayer, J.F. Resistance reconstructed estimation of total peripheral resistance from computationally derived cardiac output - biomed 2013. Biomed. Sci. Instrum. 2013, 49, 216-23.

- Redfield, M.M.; Jacobsen, S.J.; Borlaug, B.A.; Rodeheffer, R.J.; Kass, D.A. Age- and gender-related ventricular-vascular stiffening: a community-based study. Circulation 2005, 112, 2254-62. [CrossRef]

- Chantler, P.D.; Lakatta, E.G.; Najjar, S.S. Arterial-ventricular coupling: mechanistic insights into cardiovascular performance at rest and during exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985). 2008, 105, 1342-51. [CrossRef]

- Voigt, J.U.; Pedrizzetti, G.; Lysyansky, P.; Marwick, T.H.; Houle, H.; Baumann, R.; Pedri, S.; Ito, Y.; Abe, Y.; Metz, S.; et al. Definitions for a common standard for 2D speckle tracking echocardiography: consensus document of the EACVI/ASE/Industry Task Force to standardize deformation imaging. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2015, 16, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Espersen, C.; Skaarup, K.G.; Lassen, M.C.H.; Johansen, N.D.; Hauser, R.; Jensen, G.B.; Schnohr, P.; Møgelvang, R.; Biering-Sørensen, T. Right ventricular free wall and four-chamber longitudinal strain in relation to incident heart failure in the general population. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2024, 25, 396-403. [CrossRef]

- Voigt, J.U.; Mălăescu, G.G.; Haugaa, K.; Badano, L. How to do LA strain. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2020, 21, 715-717. [CrossRef]

- Sonaglioni, A.; Vincenti, A.; Baravelli, M.; Rigamonti, E.; Tagliabue, E.; Bassi, P.; Nicolosi, G.L.; Anzà, C.; Lombardo, M. Prognostic value of global left atrial peak strain in patients with acute ischemic stroke and no evidence of atrial fibrillation. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2019, 35, 603-613. [CrossRef]

- Galderisi, M.; Cosyns, B.; Edvardsen, T.; Cardim, N.; Delgado, V.; Di Salvo, G.; Donal, E.; Sade, L.E.; Ernande, L.; Garbi, M.; et al. Standardization of adult transthoracic echocardiography reporting in agreement with recent chamber quantification; diastolic function; and heart valve disease recommendations: an expert consensus document of the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2017, 18, 1301-1310. [CrossRef]

- Yingchoncharoen, T.; Agarwal, S.; Popović, Z.B.; Marwick, T.H. Normal ranges of left ventricular strain: a meta-analysis. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2013, 26, 185-91. [CrossRef]

- Muraru, D.; Onciul, S.; Peluso, D.; Soriani, N.; Cucchini, U.; Aruta, P.; Romeo, G.; Cavalli, G.; Iliceto, S.; Badano, L.P. Sex- and Method-Specific Reference Values for Right Ventricular Strain by 2-Dimensional Speckle-Tracking Echocardiography. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2016, 9, e003866. [CrossRef]

- Pathan, F.; D’’Elia, N.; Nolan, M.T.; Marwick, T.H.; Negishi, K. Normal Ranges of Left Atrial Strain by Speckle-Tracking Echocardiography: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2017, 30, 59-70.e8. [CrossRef]

- Krittanawong, C.; Maitra, N.S.; Hassan Virk, H.U.; Farrell, A.; Hamzeh, I.; Arya, B.; Pressman, G.S.; Wang, Z.; Marwick, T.H. Normal Ranges of Right Atrial Strain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2023, 16, 282-294. [CrossRef]

- Stein, J.H.; Korcarz, C.E.; Hurst, R.T.; Lonn, E.; Kendall, C.B.; Mohler, E.R.; Najjar, S.S.; Rembold, C.M.; Post, W.S.; American Society of Echocardiography Carotid Intima-Media Thickness Task Force. Use of carotid ultrasound to identify subclinical vascular disease and evaluate cardiovascular disease risk: a consensus statement from the American Society of Echocardiography Carotid Intima-Media Thickness Task Force. Endorsed by the Society for Vascular Medicine. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2008, 21, 93-111; quiz 189-90. [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, M.W.; von Kegler, S.; Steinmetz, H.; Markus, H.S.; Sitzer, M. Carotid intima-media thickening indicates a higher vascular risk across a wide age range: prospective data from the Carotid Atherosclerosis Progression Study (CAPS). Stroke 2006, 37, 87-92. [CrossRef]

- Randrianarisoa, E.; Rietig, R.; Jacob, S.; Blumenstock, G.; Haering, H.U.; Rittig, K.; Balletshofer, B. Normal values for intima-media thickness of the common carotid artery--an update following a novel risk factor profiling. Vasa 2015, 44, 444-50. [CrossRef]

- Holm, H.; Magnusson, M.; Jujić, A.; Pugliese, N.R.; Bozec, E.; Lamiral, Z.; Huttin, O.; Zannad, F.; Rossignol, P.; Girerd, N. Ventricular-arterial coupling (VAC) in a population-based cohort of middle-aged individuals: The STANISLAS cohort. Atherosclerosis 2023, 374, 11-20. [CrossRef]

- Galderisi, M.; Lomoriello, V.S.; Santoro, A.; Esposito, R.; Olibet, M.; Raia, R.; Di Minno, M.N.; Guerra, G.; Mele, D.; Lombardi, G. Differences of myocardial systolic deformation and correlates of diastolic function in competitive rowers and young hypertensives: a speckle-tracking echocardiography study. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2010, 23, 1190-8. [CrossRef]

- Kornev, M.; Caglayan, H.A.; Kudryavtsev, A.V.; Malyutina, S.; Ryabikov, A.; Schirmer, H.; Rösner, A. Influence of hypertension on systolic and diastolic left ventricular function including segmental strain and strain rate. Echocardiography 2023, 40, 623-633. [CrossRef]

- Ikonomidis, I.; Aboyans, V.; Blacher, J.; Brodmann, M.; Brutsaert, D.L.; Chirinos, J.A.; De Carlo, M.; Delgado, V.; Lancellotti, P.; Lekakis J.; et al. The role of ventricular-arterial coupling in cardiac disease and heart failure: assessment; clinical implications and therapeutic interventions. A consensus document of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Aorta & Peripheral Vascular Diseases; European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging; and Heart Failure Association. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2019, 21, 402-424. [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Lin, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Gao, L.; Ji, M.; Zhang, L.; Xie, M.; Li, Y. Clinical Usefulness of Right Ventricle-Pulmonary Artery Coupling in Cardiovascular Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2526. [CrossRef]

- Cañon-Montañez, W.; Santos, A.B.S.; Nunes, L.A.; Pires, J.C.G.; Freire, C.M.V.; Ribeiro, A.L.P.; Mill, J.G.; Bessel, M.; Duncan, B.B.; Schmidt, M.I.; et al. Central Obesity is the Key Component in the Association of Metabolic Syndrome With Left Ventricular Global Longitudinal Strain Impairment. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. (Engl Ed). 2018, 71, 524-530. English; Spanish. [CrossRef]

- Sawada, N.; Nakanishi, K.; Daimon, M.; Yoshida, Y.; Ishiwata, J.; Hirokawa, M.; Nakao, T.; Morita, H.; Di Tullio, M.R.; Homma, S.; et al. Influence of visceral adiposity accumulation on adverse left and right ventricular mechanics in the community. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2020, 27, 2006-2015. [CrossRef]

- Sonaglioni, A.; Esposito, V.; Caruso, C.; Nicolosi, G.L.; Bianchi, S.; Lombardo, M.; Gensini, G.F.; Ambrosio, G. Chest conformation spuriously influences strain parameters of myocardial contractile function in healthy pregnant women. J. Cardiovasc. Med. (Hagerstown). 2021, 22, 767-779. [CrossRef]

- Sonaglioni, A.; Ferrulli, A.; Nicolosi, G.L.; Lombardo, M.; Luzi, L. The Influence of Anthropometrics on Cardiac Mechanics in Healthy Women With Opposite Obesity Phenotypes (Android vs Gynoid). Cureus 2024, 16, e51698. [CrossRef]

- Andersgaard, A.B.; Acharya, G.; Mathiesen, E.B.; Johnsen, S.H.; Straume, B.; Øian, P. Recurrence and long-term maternal health risks of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: a population-based study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 206, 143.e1-8. [CrossRef]

- Goynumer, G.; Yucel, N.; Adali, E.; Tan, T.; Baskent, E.; Karadag, C. Vascular risk in women with a history of severe preeclampsia. J. Clin. Ultrasound. 2013, 41, 145-50. [CrossRef]

- Aykas, F.; Solak, Y.; Erden, A.; Bulut, K.; Dogan, S.; Sarli, B.; Acmaz, G.; Afsar, B.; Siriopol, D.; Covic, A.; et al. Persistence of cardiovascular risk factors in women with previous preeclampsia: a long-term follow-up study. J. Investig. Med. 2015, 63, 641-5. [CrossRef]

- Christensen, M.; Kronborg, C.S.; Carlsen, R.K.; Eldrup, N.; Knudsen, U.B. Early gestational age at preeclampsia onset is associated with subclinical atherosclerosis 12 years after delivery. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2017, 96, 1084-1092. [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Gimenez, C.; Mendoza, M.; Cruz-Lemini, M.; Galian-Gay, L.; Sanchez-Garcia, O.; Granato, C.; Rodriguez-Sureda, V.; Rodriguez-Palomares, J.; Carreras-Moratonas, E.; Cabero-Roura, L.; et al. Angiogenic Factors and Long-Term Cardiovascular Risk in Women That Developed Preeclampsia During Pregnancy. Hypertension 2020, 76, 1808-1816. [CrossRef]

- Amor, A.J.; Vinagre, I.; Valverde, M.; Alonso, N.; Urquizu, X.; Meler, E.; López, E.; Giménez, M.; Codina, L.; Conget, I.; et al. Novel glycoproteins identify preclinical atherosclerosis among women with previous preeclampsia regardless of type 1 diabetes status. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2021, 31, 3407-3414. [CrossRef]

- Fraser, A.; Nelson, S.M.; Macdonald-Wallis, C.; Cherry, L.; Butler, E.; Sattar, N.; Lawlor, D.A. Associations of pregnancy complications with calculated cardiovascular disease risk and cardiovascular risk factors in middle age: the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Circulation 2012, 125, 1367-80. [CrossRef]

- Romundstad, P.R.; Magnussen, E.B.; Smith, G.D.; Vatten, L.J. Hypertension in pregnancy and later cardiovascular risk: common antecedents? Circulation 2010, 122, 579-84. [CrossRef]

- Staff, A.C.; Johnsen, G.M.; Dechend, R.; Redman, C.W.G. Preeclampsia and uteroplacental acute atherosis: immune and inflammatory factors. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2014, 101-102, 120-126. [CrossRef]

- Veerbeek, J.H.; Brouwers, L.; Koster, M.P.; Koenen, S.V.; van Vliet, E.O.; Nikkels, P.G.; Franx, A.; van Rijn, B.B. Spiral artery remodeling and maternal cardiovascular risk: the spiral artery remodeling (SPAR) study. J. Hypertens. 2016, 34, 1570-7. [CrossRef]

- Agatisa, P.K.; Ness, R.B.; Roberts, J.M.; Costantino, J.P.; Kuller, L.H.; McLaughlin, M.K. Impairment of endothelial function in women with a history of preeclampsia: an indicator of cardiovascular risk. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2004, 286, H1389-93. [CrossRef]

- Kvehaugen, A.S.; Dechend, R.; Ramstad, H.B.; Troisi, R.; Fugelseth, D.; Staff, A.C. Endothelial function and circulating biomarkers are disturbed in women and children after preeclampsia. Hypertension 2011, 58, 63-9. [CrossRef]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 203: Chronic Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 133, e26-e50. [CrossRef]

- Mureddu, G.F. How much does hypertension in pregnancy affect the risk of future cardiovascular events? Eur. Heart J. Suppl. 2023, 25, B111-B113. [CrossRef]

- Negishi, T.; Negishi, K.; Thavendiranathan, P.; Cho, G.Y.; Popescu, B.A.; Vinereanu, D.; Kurosawa, K.; Penicka, M.; Marwick, T.H.; SUCCOUR Investigators. Effect of Experience and Training on the Concordance and Precision of Strain Measurements. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2017, 10, 518-522. [CrossRef]

- Rösner, A.; Barbosa, D.; Aarsæther, E.; Kjønås, D.; Schirmer, H.; D’hooge, J. The influence of frame rate on two-dimensional speckle-tracking strain measurements: a study on silico-simulated models and images recorded in patients. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2015, 16, 1137-47. [CrossRef]

- Mirea, O.; Pagourelias, E.D.; Duchenne, J.; Bogaert, J.; Thomas, J.D.; Badano, L.P.; Voigt, J.U.; EACVI-ASE-Industry Standardization Task Force. Intervendor Differences in the Accuracy of Detecting Regional Functional Abnormalities: A Report From the EACVI-ASE Strain Standardization Task Force. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2018, 11, 25-34. [CrossRef]

- Sonaglioni, A.; Fagiani, V.; Nicolosi, G.L.; Lombardo, M. The influence of pectus excavatum on biventricular mechanics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Minerva Cardiol. Angiol. 2024 Sep 24. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Examples of biventricular and biatrial longitudinal strain parameters measured from the apical four-chamber view in a pHDP woman included in the present study. All myocardial strain parameters are reduced in comparison to the accepted reference ranges. GLS, global longitudinal strain; LASr, left atrial reservoir strain; LV, left ventricular; pHDP, previous hypertensive disorder of pregnancy; RASr, right atrial reservoir strain; RV, right ventricular.

Figure 1.

Examples of biventricular and biatrial longitudinal strain parameters measured from the apical four-chamber view in a pHDP woman included in the present study. All myocardial strain parameters are reduced in comparison to the accepted reference ranges. GLS, global longitudinal strain; LASr, left atrial reservoir strain; LV, left ventricular; pHDP, previous hypertensive disorder of pregnancy; RASr, right atrial reservoir strain; RV, right ventricular.

Figure 2.

Examples of LV-GLS bull’’s-eye plots obtained in a pHDP woman with previous pregnancy complicated by obesity and PE (Panel A) and in a woman with previous uncomplicated pregnancy (Panel B), respectively. GLS, global longitudinal strain; LV, left ventricular; PE, pre-eclampsia; pHDP, previous hypertensive disorder of pregnancy.

Figure 2.

Examples of LV-GLS bull’’s-eye plots obtained in a pHDP woman with previous pregnancy complicated by obesity and PE (Panel A) and in a woman with previous uncomplicated pregnancy (Panel B), respectively. GLS, global longitudinal strain; LV, left ventricular; PE, pre-eclampsia; pHDP, previous hypertensive disorder of pregnancy.

Figure 3.

ROC curve analysis performed to establish the sensitivity and the specificity of third trimester BMI for predicting the secondary endpoint, over follow-up period. AUC, area under curve; BMI, body mass index; ROC, receiver operating characteristics.

Figure 3.

ROC curve analysis performed to establish the sensitivity and the specificity of third trimester BMI for predicting the secondary endpoint, over follow-up period. AUC, area under curve; BMI, body mass index; ROC, receiver operating characteristics.

Table 1.

Demographic, anthropometric, obstetrical, clinical, hemodynamic, conventional echocardiographic, myocardial strain and carotid ultrasound parameters measured in pHDP women and controls.

Table 1.

Demographic, anthropometric, obstetrical, clinical, hemodynamic, conventional echocardiographic, myocardial strain and carotid ultrasound parameters measured in pHDP women and controls.

| Demographic, anthropometric, obstetrical and clinical parameters |

Age, ethnicity, BSA, BMI, previous pregnancies, gestational week of hypertension onset, gestational age at delivery, prevalence of smoking, dyslipidemia and family history of hypertension, any comorbidity such as hypothyroidism, anaemia and thrombophilia, cardiac rhythm and HR, serum levels of haemoglobin, creatinine and eGFR [23], fasting glucose, total cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, triglycerides and uric acid, previous evidence of proteinuria (at urine protein test) and both the previous and the current antihypertensive therapy. |

| Conventional echoDoppler parameters by using Philips Sparq ultrasound machine (Philips, Andover, Massachusetts, USA) with a 2.5 MHz transducer |

Aortic root and ascending aorta (by the “leading edge-to-leading edge” convention); RWT = 2 PWT/LVEDD; LVMi (by the Devereux’s formula); LVEF (by the biplane modified Simpson’s method, as index of LV systolic function) [24]; LAVi (as index of LA size); RVIT (as index of RV size); TAPSE (as index of RV systolic function); E/A ratio (as index of LV diastolic function); E/average e’ ratio (as index of LVFP) [25]; sPAP = 4TRV2+RAP [26]; TAPSE/sPAP ratio (as index of RV/PA coupling) [27]. |

| Hemodynamic indices |

Brachial SBP and DBP; MAP = DBP + [(SBP-DBP/3)] [28]; PP = SBP-DBP [29];

SV = LVOT area X LVOT VTI [30]; CO = SV X HR [30]; TPR = MAP/CO x 80 [31]; ESP = 0.9 X SBP [32]; EaI = ESP/SVindex ratio [33]; EesI = ESP/LVESVi [33]; VAC = EaI/EesI ratio [33]. |

Myocardial strain parameters

by using Philips QLAB software and Q-Analysis module [34].

|

LV-GLS (as the mean of strain curves obtained from the apical 4-chamber, 2-chamber and 3-chamber views), LV-GCS (as the mean of strain curves obtained from the parasternal short-axis views at basal, mid and apical level) [34];

RV-GLS (as the mean of lateral and septal strain curves from the apical 4-chamber view), RV-FWLS (as the mean of RV lateral basal, mid and apical segments, with exclusion of septal segments from the apical 4-chamber) [35];

LASr [by tracing the edges of the mitral annulus and the endocardial side of the LA roof from the apical 4-chamber and 2-chamber views (biplane method)] = LAScd (peak positive LA strain) + LASct (peak negative LA strain); LA-GSR+, LA-GSRE and LA-GSRL [36]; LA stiffness = LASr/E/average e’ ratio [37];

RASr (by tracing the edges of the tricuspid annulus and the endocardial side of the RA roof from the apical 4-chamber); RA-GSR+, RA-GSRE and RA-GSRL.

Absolute values inferior to 20% for LV-GLS [38], 23.3% for LV-GCS [39], 20% for RV-GLS [40], 39% for LASr [41] and 35% for RASr [42] were considered to be abnormal. |

Carotid ultrasound parameters

by using Philips Sparq ultrasound machine with a 12 MHz transducer.

|

Av. left and right CCA-IMT, av. left and right CCA-EDD (at 1 cm from the carotid bifurcation), av. left and right carotid RWT = 2 × average IMT/average CCA-EDD, av. left and right CCA-CSA = [π × (2 × average IMT + average CCA-EDD)/2)2 − π × (average CCA-EDD/2)2] [43].

Based on the accepted reference ranges for age and sex [44,45], CCA-IMT values ≥0.7 mm were considered to be abnormal. |

Table 2.

Clinical, obstetrical, hemodynamic and laboratory parameters collected in HDP women and controls at the third trimester of pregnancy.

Table 2.

Clinical, obstetrical, hemodynamic and laboratory parameters collected in HDP women and controls at the third trimester of pregnancy.

| |

HDP women

(n = 31) |

Controls

(n = 30) |

p-Value |

| Demographics, anthropometrics, cardiovascular risk factors and obstetrics |

| Age (yrs) |

36.6 ± 5.9 |

36.7 ± 2.9 |

0.93 |

| Age ≥35 yrs (%) |

22 (70.9) |

20 (66.6) |

0.72 |

| Caucasian ethnicity (%) |

27 (87.1) |

26 (86.7) |

0.96 |

| BSA (m2) |

1.87 ± 0.16 |

1.85 ± 0.11 |

0.57 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) |

28.0 ± 4.7 |

27.5 ± 2.8 |

0.61 |

| Smoking |

2 (6.4) |

4 (13.3) |

0.37 |

| Dyslipidemia |

10 (32.3) |

1 (3.3) |

0.003 |

| Obesity (BMI ≥30 Kg/m2) (%) |

8 (25.8) |

5 (16.7) |

0.38 |

| Family history of hypertension (%) |

18 (58.1) |

6 (20.0) |

0.002 |

| Previous pregnancies (n) |

1.7 ± 1.1 |

1.6 ± 1.0 |

0.71 |

| Gestational age at enrollment (weeks) |

32.0 ± 8.1 |

34.5 ± 3.8 |

0.13 |

| Gestational week at delivery (weeks) |

37.7 ± 1.5 |

39.2 ± 1.4 |

<0.001 |

| Hemodynamics |

| HR (bpm) |

81.8 ± 12.6 |

78.3 ± 12.1 |

0.27 |

| SBP (mmHg) |

132.4 ± 14.7 |

110.0 ± 7.2 |

<0.001 |

| DBP (mmHg) |

85.4 ± 7.2 |

66.7 ± 5.8 |

<0.001 |

| PP (mmHg) |

47.1 ± 11.4 |

43.3 ± 7.3 |

0.13 |

| MAP (mmHg) |

101.1 ± 8.8 |

81.1 ± 5.2 |

<0.001 |

| Laboratory tests |

| Serum hemoglobin (g/dl) |

11.6 ± 1.7 |

11.2 ± 1.5 |

0.33 |

| eGFR (ml/min/m2) |

138.4 ± 48.3 |

136.6 ± 30.1 |

0.86 |

| Serum glucose (mg/dl) |

83.6 ± 13.1 |

86.4 ± 13.8 |

0.42 |

| Serum total cholesterol (mg/dl) |

197.6 ± 25.5 |

171.2 ± 10.5 |

<0.001 |

| Serum uric acid (mg/dl) |

4.2 ± 0.4 |

4.1 ± 0.5 |

0.39 |

| Proteinuria (%) |

19 (61.3) |

/ |

/ |

| Medical treatment during pregnancy |

| Calcium channel blockers (%) |

11 (35.5) |

/ |

/ |

| Alpha2-agonists (%) |

8 (25.8) |

/ |

/ |

| Alpha-beta blockers (%) |

2 (6.5) |

/ |

/ |

| Dual therapy (%) |

9 (29.0) |

/ |

/ |

| No therapy (%) |

4 (12.9) |

30 (100) |

<0.001 |

Table 3.

Clinical characteristics of the two study groups at 6 yrs postpartum.

Table 3.

Clinical characteristics of the two study groups at 6 yrs postpartum.

| |

pHDP women

(n = 31) |

Controls

(n = 30) |

p-Value |

| Demographics and anthropometrics |

| Age (yrs) |

42.3 ± 5.9 |

40.8 ± 5.0 |

0.29 |

| Age ≥40 rs (%) |

23 (74.2) |

19 (63.3) |

0.36 |

| BSA (m2) |

1.68 ± 0.17 |

1.66 ± 0.14 |

0.62 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) |

23.2 ± 5.2 |

22.2 ± 2.8 |

0.36 |

| Normal weight (BMI 18.5-24.9 Kg/m2) (%) |

24 (77.4) |

24 (80.0) |

0.80 |

| Ethnicity |

| Caucasian (%) |

27 (87.1) |

26 (86.7) |

0.96 |

| Asiatic (%) |

2 (6.5) |

2 (6.7) |

0.97 |

| African (%) |

1 (3.2) |

1 (3.3) |

0.98 |

| Latin American (%) |

1 (3.2) |

1 (3.3) |

0.98 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors |

| Smoking (%) |

2 (6.5) |

6 (20.0) |

0.12 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus (%) |

2 (6.5) |

1 (3.3) |

0.57 |

| Dyslipidemia (%) |

7 (22.6) |

1 (3.3) |

0.02 |

| Obesity (%) |

7 (22.6) |

1 (3.3) |

0.02 |

| Blood pressure parameters |

| SBP (mmHg) |

127.5 ± 16.8 |

113.2 ± 11.1 |

<0.001 |

| DBP (mmHg) |

78.4 ± 13.7 |

70.4 ± 9.4 |

0.01 |

| PP (mmHg) |

49.2 ± 9.9 |

42.8 ± 9.4 |

0.01 |

| MBP (mmHg) |

94.4 ± 13.7 |

84.6 ± 8.9 |

<0.001 |

| BP ≥140/90 mmHg at clinical visit (%) |

11 (35.5) |

2 (6.7) |

0.006 |

| Blood tests |

| Serum Hb (g/dl) |

12.9 ± 0.8 |

12.7 ± 1.2 |

0.44 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) |

0.77 ± 0.13 |

0.72 ± 0.16 |

0.18 |

| eGFR (ml/min/m2) |

95.2 ± 16.3 |

101.1 ± 18.1 |

0.18 |

| Serum glucose (mg/dl) |

87.1 ± 6.2 |

86.3 ± 7.1 |

0.64 |

| Serum total cholesterol (mg/dl) |

195.8 ± 13.7 |

192.0 ± 8.1 |

0.19 |

| Serum HDL-cholesterol (mg/dl) |

68.7 ± 8.2 |

75.2 ± 6.5 |

0.001 |

| Serum LDL-cholesterol (mg/dl) |

113.8 ± 11.4 |

108.2 ± 7.1 |

0.02 |

| Serum triglycerides (mg/dl) |

66.1 ± 15.4 |

68.7 ± 11.5 |

0.46 |

| Serum uric acid (mg/dl) |

4.3 ± 1.1 |

4.7 ± 1.4 |

0.22 |

| Comorbidities |

| Hypothyroidism (%) |

4 (12.9) |

8 (26.7) |

0.18 |

| Current medical treatment |

| pHDP women in medical therapy (%) |

10 (32.3) |

/ |

/ |

| ACE-i/ARBs (%) |

6 (19.3) |

/ |

/ |

| Calcium channel blockers (%) |

5 (16.1) |

/ |

/ |

| Beta blockers (%) |

2 (6.5) |

/ |

/ |

| Diuretics (%) |

1 (3.2) |

/ |

/ |

| Statins (%) |

1 (3.2) |

/ |

/ |

| Thyroid hormone therapy (%) |

4 (12.9) |

8 (26.7) |

0.18 |

Table 4.

Morphological, functional and hemodynamic parameters assessed by conventional transthoracxic echocardiography and carotid ultrasonography in the two groups of women at 6 yrs postpartum.

Table 4.

Morphological, functional and hemodynamic parameters assessed by conventional transthoracxic echocardiography and carotid ultrasonography in the two groups of women at 6 yrs postpartum.

| |

pHDP women

(n = 31) |

Controls

(n = 30) |

p-Value |

| Yrs postpartum at echocardiographic assessment |

6.1 ± 1.3 |

6.0 ± 0.3 |

0.68 |

| Conventional echoDoppler parameters |

| IVS (mm) |

9.4 ± 1.7 |

7.6 ± 1.2 |

<0.001 |

| LV-PW (mm) |

7.4 ± 1.1 |

6.6 ± 1.0 |

0.004 |

| LV-EDD (mm) |

42.6 ± 3.8 |

44.4 ± 2.7 |

0.04 |

| RWT |

0.35 ± 0.05 |

0.30 ± 0.05 |

<0.001 |

| LVMi (g/m2) |

66.6 ± 13.9 |

57.7 ± 9.7 |

0.005 |

| Normal LV geometric pattern (%) |

27 (87.1) |

28 (93.4) |

0.41 |

| LV concentric remodeling (%) |

3 (9.7) |

1 (3.3) |

0.32 |

| LV eccentric remodeling (%) |

1 (3.2) |

1 (3.3) |

0.98 |

| LVEDVi (ml/m2) |

35.7 ± 6.6 |

35.3 ± 5.6 |

0.79 |

| LVESVi (ml/m2) |

11.6 ± 2.4 |

11.9 ± 2.5 |

0.63 |

| LVEF (%) |

66.9 ± 3.1 |

65.9 ± 4.8 |

0.33 |

| E/A ratio |

1.14 (0.67-1.76) |

1.34 (0.71-2.1) |

0.02 |

| E/e’ ratio |

8.02 ± 2.32 |

5.14 ± 1.34 |

<0.001 |

| LA A-P diameter (mm) |

34.3 ± 5.4 |

33.6 ± 4.1 |

0.57 |

| LA longitudinal diameter (mm) |

44.8 ± 6.1 |

46.4 ± 4.9 |

0.26 |

| LAVi (ml/m2) |

29.0 ± 7.5 |

27.4 ± 7.3 |

0.40 |

| Mild MR (n, %) |

12 (38.7) |

9 (30.0) |

0.95 |

| Mild TR (n, %) |

19 (61.3) |

17 (56.6) |

0.71 |

| RVIT (mm) |

28.9 (24-36) |

29.7 (23.5-34) |

0.31 |

| TAPSE (mm) |

24.6 (20-30) |

26.4 (19-32) |

0.04 |

| IVC (mm) |

15.2 ± 4.1 |

17.0 ± 3.9 |

0.08 |

| sPAP (mmHg) |

23.9 ± 3.1 |

22.8 ± 2.2 |

0.12 |

| TAPSE/sPAP ratio |

1.05 ± 0.18 |

1.17 ± 0.18 |

0.01 |

| Aortic root (mm) |

30.8 ± 2.6 |

29.1 ± 2.6 |

0.01 |

| Ascending aorta (mm) |

29.5 ± 4.1 |

28.8 ± 3.1 |

0.46 |

| Hemodynamic indices |

| Heart rate (bpm) |

79.6 (58-103) |

75.5 (62-100) |

0.19 |

| ESP (mmHg) |

114.1 ± 14.8 |

101.9 ± 10.0 |

<0.001 |

| SVi (ml/m2) |

35.2 ± 6.9 |

39.5 ± 9.1 |

0.04 |

| COi (l/min/m2) |

2.81 ± 0.74 |

2.93 ± 0.67 |

0.51 |

| TPRi (dyne.sec/cm5)/m2

|

2863.3 ± 837.6 |

2427.5 ± 620.6 |

0.02 |

| EaI (mmHg/ml/m2) |

3.4 ± 0.9 |

2.7 ± 0.7 |

0.001 |

| EesI (mmHg/ml/m2) |

10.1 ± 2.1 |

9.0 ± 2.4 |

0.06 |

| EaI/EesI ratio |

0.34 ± 0.10 |

0.32 ± 0.09 |

0.41 |

| Carotid parameters |

| Av. CCA-EDD (mm) |

6.64 ± 0.53 |

6.64 ± 0.44 |

>0.99 |

| Av. CCA-IMT (mm) |

0.90 ± 0.21 |

0.62 ± 0.19 |

<0.001 |

| Av. CCA-IMT ≥0.7 mm (%) |

27 (87.1) |

7 (23.3) |

<0.001 |

| Av. CCA-RWT |

0.28 ± 0.08 |

0.19 ± 0.06 |

<0.001 |

| Av. CCA-CSA (mm2) |

22.90 ± 7.91 |

14.20 ± 4.94 |

<0.001 |

Table 5.

Biventricular and biatrial strain parameters measured by speckle tracking echocardiography in the two study groups at 6 yrs postpartum.

Table 5.

Biventricular and biatrial strain parameters measured by speckle tracking echocardiography in the two study groups at 6 yrs postpartum.

| STE VARIABLES |

pHDP women

(n = 31) |

Controls

(n = 30) |

p-Value |

| LV-GLS (%) |

19.5 ± 2.6 |

22.3 ± 2.3 |

<0.001 |

| LV-GLSR (s-1) |

1.1 ± 0.1 |

1.2 ± 0.1 |

<0.001 |

| LV-GCS (%) |

24.5 ± 5.5 |

26.7 ± 4.4 |

0.09 |

| LV-GCSR (s-1) |

1.6 ± 0.3 |

1.7 ± 0.2 |

0.13 |

| LAScd (%) |

30.1 ± 7.3 |

36.3 ± 7.7 |

0.002 |

| LASct (%) |

7.7 ± 4.8 |

9.4 ± 4.1 |

0.14 |

| LASr (%) |

37.8 ± 8.0 |

45.7 ± 8.0 |

<0.001 |

| LASr/E/e’ |

5.1 ± 1.8 |

9.5 ± 3.2 |

<0.001 |

| LA-GSR+ (s-1) |

2.0 ± 0.5 |

2.3 ± 0.5 |

0.02 |

| LA-GSRE (s-1) |

2.4 ± 0.8 |

3.1 ± 0.8 |

0.001 |

| LA-GSRL (s-1) |

2.7 ± 0.7 |

2.8 ± 0.5 |

0.52 |

| RV-FWLS (%) |

19.8 ± 3.6 |

22.0 ± 3.5 |

0.02 |

| RV-GLS (%) |

18.6 ± 3.3 |

20.9 ± 3.4 |

0.01 |

| RV-GLSR (s-1) |

1.2 ± 0.2 |

1.3 ± 0.2 |

0.06 |

| RAScd (%) |

28.0 ± 8.2 |

34.6 ± 10.1 |

0.007 |

| RASct (%) |

7.2 ± 4.7 |

7.5 ± 5.4 |

0.82 |

| RASr (%) |

35.2 ± 7.7 |

42.1 ± 9.9 |

0.004 |

| RA-GSR+ (s-1) |

2.2 ± 0.5 |

2.4 ± 0.6 |

0.16 |

| RA-GSRE (s-1) |

1.9 (1.1-3.0) |

2.3 (1.3-3.5) |

0.02 |

| RA-GSRL (s-1) |

2.3 (1.1-4.0) |

2.5 (1.3-5.0) |

0.30 |

| PERCENTAGE OF WOMEN WITH IMPAIRED STE PARAMETERS COMPARED TO REFERENCE VALUES |

| LV-GLS <20% (%) |

18 (58.1) |

4 (13.3) |

<0.001 |

| LV-GCS <23.3% (%) |

12 (38.7) |

7 (23.3) |

0.19 |

| LASr <39% (%) |

17 (54.8) |

5 (16.7) |

0.002 |

| RV-GLS <20% (%) |

22 (71.0) |

11 (36.7) |

0.007 |

| RASr <35% (%) |

18 (58.1) |

8 (26.7) |

0.01 |

Table 6.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses performed for identifying the independent predictors of subclinical myocardial dysfunction, at 6 yrs postpartum. Significant p-values are in bold. BMI, body mass index; PE, pre-eclampsia.

Table 6.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses performed for identifying the independent predictors of subclinical myocardial dysfunction, at 6 yrs postpartum. Significant p-values are in bold. BMI, body mass index; PE, pre-eclampsia.

| |

UNIVARIATE COX REGRESSION ANALYSIS |

MULTIVARIATE COX REGRESSION ANALYSIS |

| VARIABLES |

HR |

95% CI |

p-Value |

HR |

95% CI |

p-Value |

| Third trimester age (yrs) |

1.00 |

0.89-1.06 |

0.47 |

|

|

|

| Third trimester BMI (Kg/m2) |

1.12 |

1.02-1.22 |

0.02 |

1.05 |

0.95-1.16 |

0.36 |

| Previous PE |

5.09 |

1.47-17.6 |

0.01 |

4.01 |

1.05-15.3 |

0.03 |

| Chronic antihypertensive treatment |

0.97 |

0.34-2.77 |

0.96 |

|

|

|

Table 7.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses performed for identifying the independent predictors of subclinical carotid atherosclerosis at 6 yrs postpartum. Significant p-values are in bold. BMI, body mass index; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; PE, pre-eclampsia.

Table 7.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses performed for identifying the independent predictors of subclinical carotid atherosclerosis at 6 yrs postpartum. Significant p-values are in bold. BMI, body mass index; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; PE, pre-eclampsia.

| |

UNIVARIATE COX REGRESSION ANALYSIS |

MULTIVARIATE COX REGRESSION ANALYSIS |

| VARIABLES |

HR |

95% CI |

p-Value |

HR |

95% CI |

p-Value |

| Third trimester age (yrs) |

1.01 |

0.93-1.09 |

0.86 |

|

|

|

| Third trimester BMI (Kg/m2) |

1.14 |

1.04-1.24 |

0.004 |

1.21 |

1.07-1.38 |

0.003 |

| Previous PE |

4.49 |

1.31-15.4 |

0.02 |

6.38 |

1.50-27.2 |

0.01 |

| Current HDL-cholesterol (mg/dl) |

0.99 |

0.94-1.05 |

0.86 |

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).