3. Materials

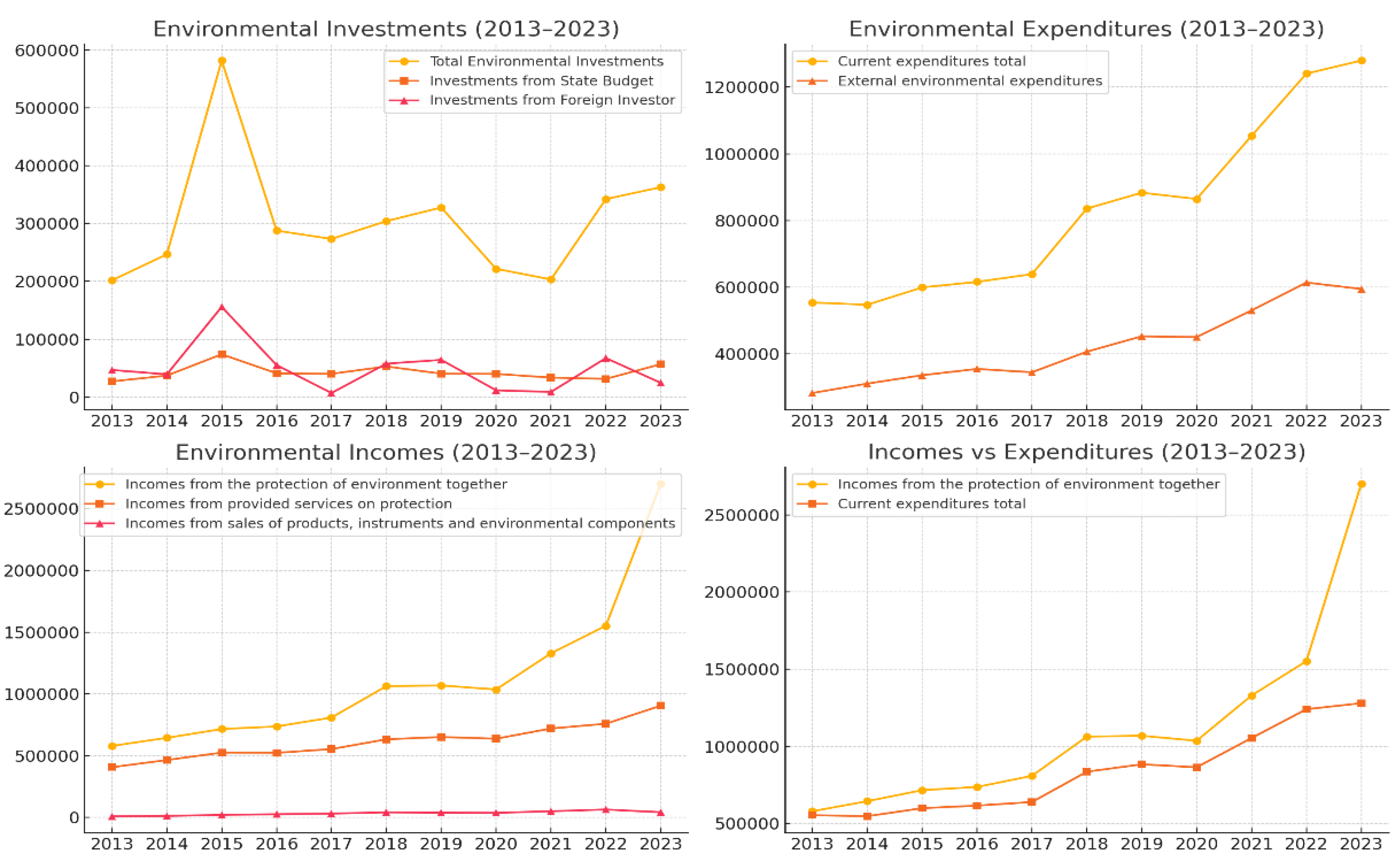

The transition toward a CE model in municipal governance is inherently tied to the reallocation of public funds, changes in budgetary priorities, and the emergence of new revenue streams. The Slovak case, represented by data from 2013 to 2023, offers valuable insights into these dynamics, (

Figure 1), (

Appendix A).

Between 2013 and 2023, total environmental investments in Slovakia fluctuated significantly, with notable peaks in 2015 (€581.7 million) and 2023 (€362.7 million), and a low point in 2013 (€201.8 million). While investment volumes varied year to year, there was a consistent reliance on the state budget, contributing approximately €27–74 million annually, and a more variable contribution from foreign investors, ranging from €4.6 million (2013) to €155.9 million (2015).

This variation reflects both the availability of external funding mechanisms (e.g., EU structural funds) and changing domestic priorities. The increase in investment during recent years, especially post-2020, suggests a response to European Green Deal objectives and recovery funding post-COVID-19, reinforcing the alignment of capital investments with circular economy policy frameworks [

16].

Over the same period, current expenditures on environmental protection more than doubled — from €554.1 million in 2013 to nearly €1.28 billion in 2023. This includes internal costs (salaries, operations), which grew steadily, and external environmental expenditures, rising from €282.8 million to €594.8 million. The rise reflects both inflation and the expansion of municipal services linked to CE initiatives such as waste separation, composting, and service contracting.

A critical observation is the steady growth in revenue generation from environmental services. Total incomes from environmental protection grew from €579.5 million in 2013 to €2.7 billion in 2023 — more than a fourfold increase. This trend is driven by:

- —

increased sales of services (e.g., collection and processing fees),

- —

expansion of product sales (e.g., recycled materials),

- —

monetisation of environmental technologies and instruments.

These figures confirm the CE's potential not only as a cost centre but as a revenue-generating domain for municipalities. The financial transformation is evident: where early CE investments were mainly expenditure-driven, recent years illustrate a shift towards fiscal self-sufficiency and value creation through circular systems.

The investment and expenditure structure shown in the Slovak context highlights several core insights:

- —

A well-financed CE transition can yield measurable operational revenues over time.

- —

Municipalities benefit from external co-financing mechanisms, especially in early phases.

- —

Long-term planning enables a shift from subsidy-dependence to income-generation.

In conclusion, the financial evolution in Slovakia offers an empirical demonstration of the circular economy’s viability in municipal settings — not only as a sustainability imperative but also as a driver of budgetary resilience and strategic reinvestment.

Over the period 2013 to 2023, Slovakia's environmental investments per capita displayed notable fluctuations, reflecting both national policy shifts and external economic influences. The total environmental investments ranged from €201.8 million in 2013 to a peak of €581.7 million in 2015, followed by a period of relative stabilisation. On a per capita basis, the investment increased from €37.29 in 2013 to €66.81 in 2023.

The most significant increase occurred in 2015, where per capita investment rose sharply to €107.31, more than doubling the value recorded the previous year. This peak is likely attributable to targeted capital programmes or the absorption of EU structural funds at the close of a programming period. However, this surge was not sustained, and the per capita investment declined in subsequent years, stabilising between €37 and €66 per person from 2016 onward.

From 2020 onwards, despite the economic uncertainty caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, per capita investment showed a gradual recovery, increasing from €40.61 in 2020 to €66.81 in 2023. This trend may reflect enhanced prioritisation of environmental resilience and green recovery efforts.

These investment patterns underscore the strategic shifts in environmental governance and public spending, suggesting that while short-term fluctuations are common, the long-term trajectory points to a growing emphasis on per capita environmental investment [

19].

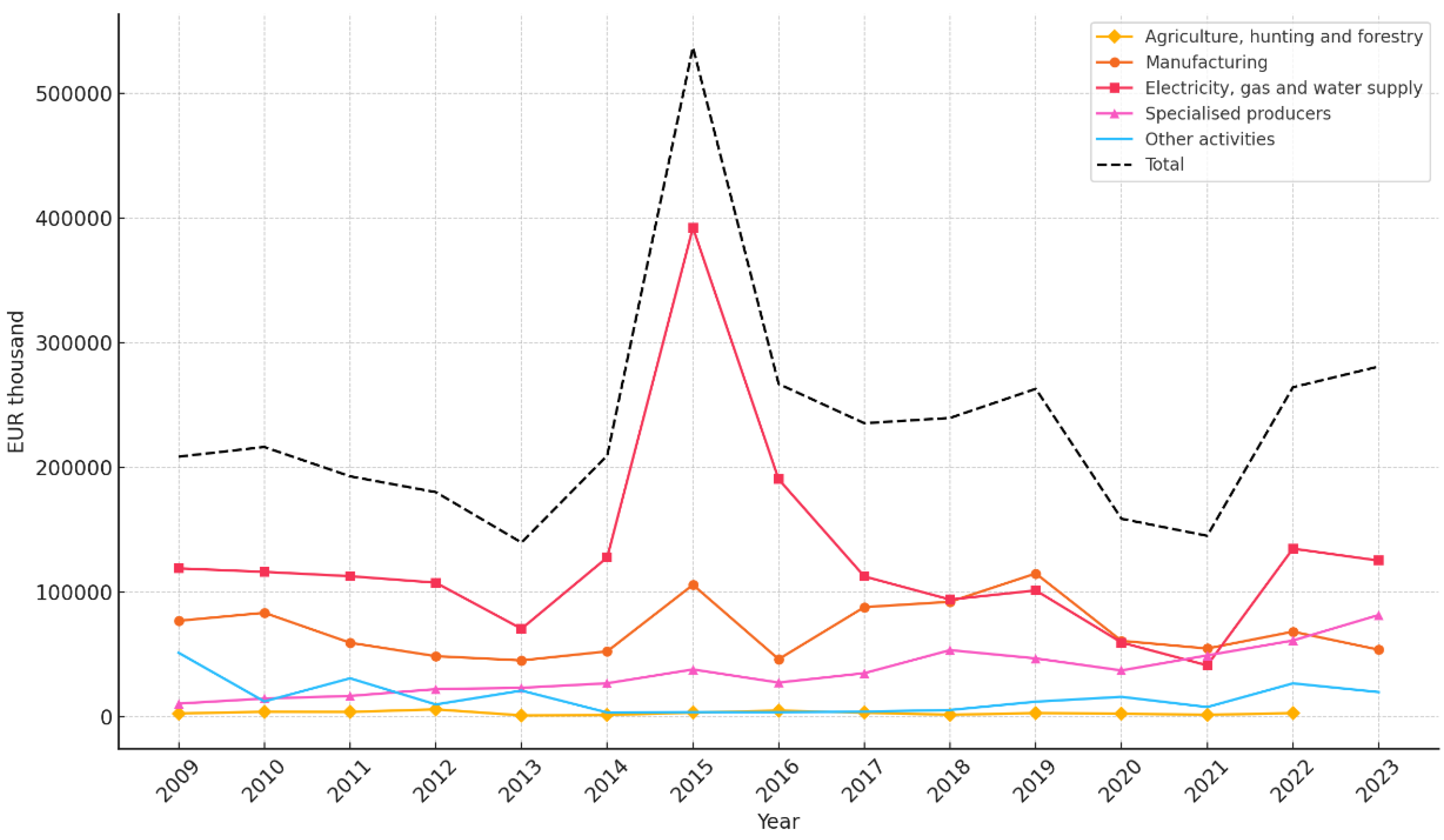

Strategic Investment Flows and the Circular Economy Transition

To complement the analysis of aggregate environmental expenditures at the municipal level, it is essential to examine how capital investments have evolved across economic sectors, as these sectors often operate in partnership with or under the regulation of municipal authorities. The data covering Slovakia from 2009 to 2023 offers valuable insights into sectoral engagement with CE objectives, (

Figure 2), (

Appendix A).

The most pronounced trend over the 15-year period is the sustained dominance of the electricity, gas, and water supply sector in environmental investment. With peaks reaching €392.3 million in 2015 and €125.3 million in 2023, this sector serves as the backbone of CE infrastructure, especially in areas such as energy recovery from waste, water reuse systems, and smart grid integration. The magnitude and consistency of investment highlight the crucial role this sector plays in enabling municipal-level CE strategies through technical and service-oriented capacities.

The role of specialised producers (often municipal utilities or private-public joint ventures) has steadily increased, with capital inflows growing from €10.5 million in 2009 to €81.6 million in 2023. These actors are central to implementing CE-related services—particularly in waste treatment, recycling, and composting—and their growing financial weight suggests a municipal shift from linear waste disposal to circular resource recovery.

Manufacturing also emerges as a consistent, though secondary, recipient of environmental investment. The sector demonstrates a strong presence in pre-2020 figures, peaking at over €114.9 million in 2019, but shows more volatility in recent years. Its role in material efficiency and industrial symbiosis remains relevant for circularity at the local level, particularly where municipalities collaborate with local industries on by-product valorisation and cleaner production.

Meanwhile, sectors such as agriculture and mining received minimal funding or had data suppressed due to confidentiality in 2023. This suggests limited engagement or reporting challenges in CE-aligned initiatives within these traditionally resource-intensive domains [45, 46, 48].

The inclusion of “other activities”, receiving €19.8 million in 2023, provides evidence of CE spillover effects into construction, logistics, and services—areas frequently linked to local government operations. Such diversification indicates a maturing CE investment landscape that goes beyond heavy infrastructure and integrates broader urban systems.

Finally, the total environmental investment rose from €208.6 million in 2009 to €280.9 million in 2023, despite sharp fluctuations across the years. Notably, investment levels surged in 2015–2016, possibly reflecting the absorption of EU cohesion funding under the 2007–2013 programming period. While municipal expenditure remains a major pillar, this sectoral data affirms the increasing importance of cross-sectoral partnerships and private-sector mobilisation in financing CE transitions at the local level.

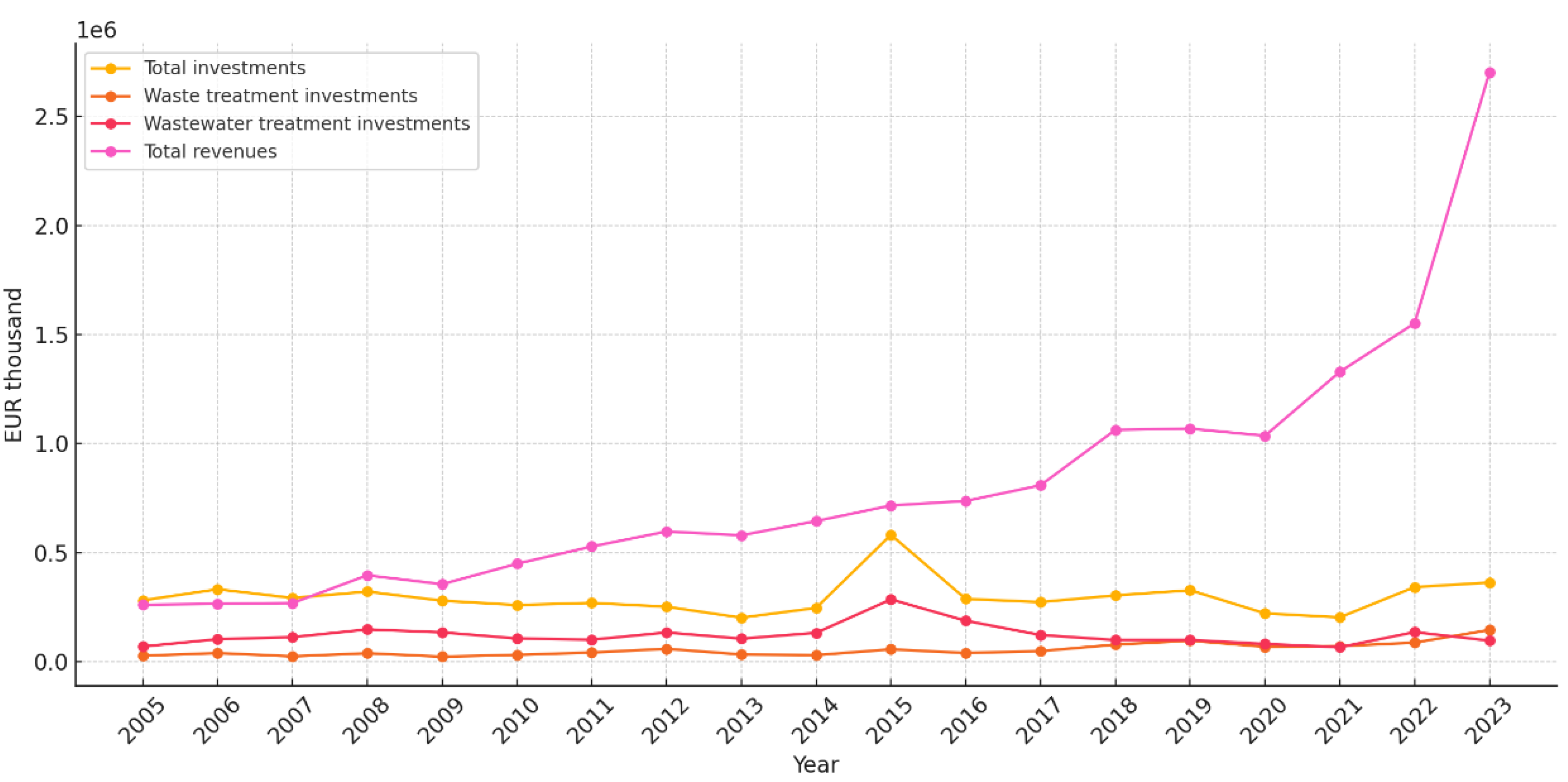

Analytical Commentary on Environmental Expenditure and Revenue Trends.

The longitudinal data on environmental expenditures and revenues in Slovakia from 2005 to 2023 offers valuable insights into the financial dynamics of the circular economy transition at the municipal level, (

Figure 3). The analysis focuses on three primary indicators: total environmental investments, capital expenditure on waste and wastewater treatment, and total revenues generated from environ-mental protection activities.

Over the examined period, total investments in environmental protection displayed significant volatility, ranging from a low of €201.79 million in 2013 to a peak of €581.74 million in 2015. This variability likely reflects the influence of external funding cycles, particularly from EU structural and cohesion funds. Notably, post-2020 investment figures suggest renewed momentum, with val-ues exceeding €340 million annually since 2021. This resurgence may be attributed to green recovery packages and increased policy emphasis on sustainable infrastructure following the COVID-19 pandemic [

15].

Waste treatment—one of the core pillars of the circular economy—shows a clear upward trajectory, particularly in the last decade. From a relatively modest €27.06 million in 2005, investments rose to €145.53 million by 2023. This fivefold increase indicates a pro-gressive shift towards modernisation and expansion of municipal waste management systems. However, the fluctuations between years, such as the drop in 2017 (€39.93 million) and spike in 2023, suggest that investment is still somewhat reactive to project availability and budgetary cycles rather than being part of a sustained long-term strategy.

Similarly, capital investments in wastewater treatment demonstrate robust growth, peaking at €285.64 million in 2015. While sub-sequent years saw some contraction, the overall trend remains positive, with a renewed increase to €96.36 million in 2023. These figures underline ongoing efforts to meet EU wastewater directive requirements and to upgrade municipal water infrastructure in line with circular economy principles, which emphasise water reuse and pollution reduction.

The evolution of revenues from environmental protection activities serves as a proxy for the economic maturity of green municipal initiatives. From €261 million in 2005, revenues grew steadily, surpassing €1 billion from 2018 onwards and reaching €2.7 billion in 2023. This substantial increase suggests that municipalities are progressively moving beyond the cost-intensive phase of infrastruc-ture development towards a model that yields measurable financial returns—potentially from waste valorisation, recycling mar-kets, and environmental services.

The upward trends in both investment and revenue generation, particularly in waste and wastewater sectors, provide empirical support for the strategic role of municipalities in fostering circular economy transitions. Nonetheless, the volatility observed in cer-tain years points to a need for greater financial stability and long-term planning frameworks. Additionally, aligning capital ex-penditure with clear indicators of environmental and economic impact remains crucial for ensuring that investments contribute meaningfully to systemic sustainability goals.

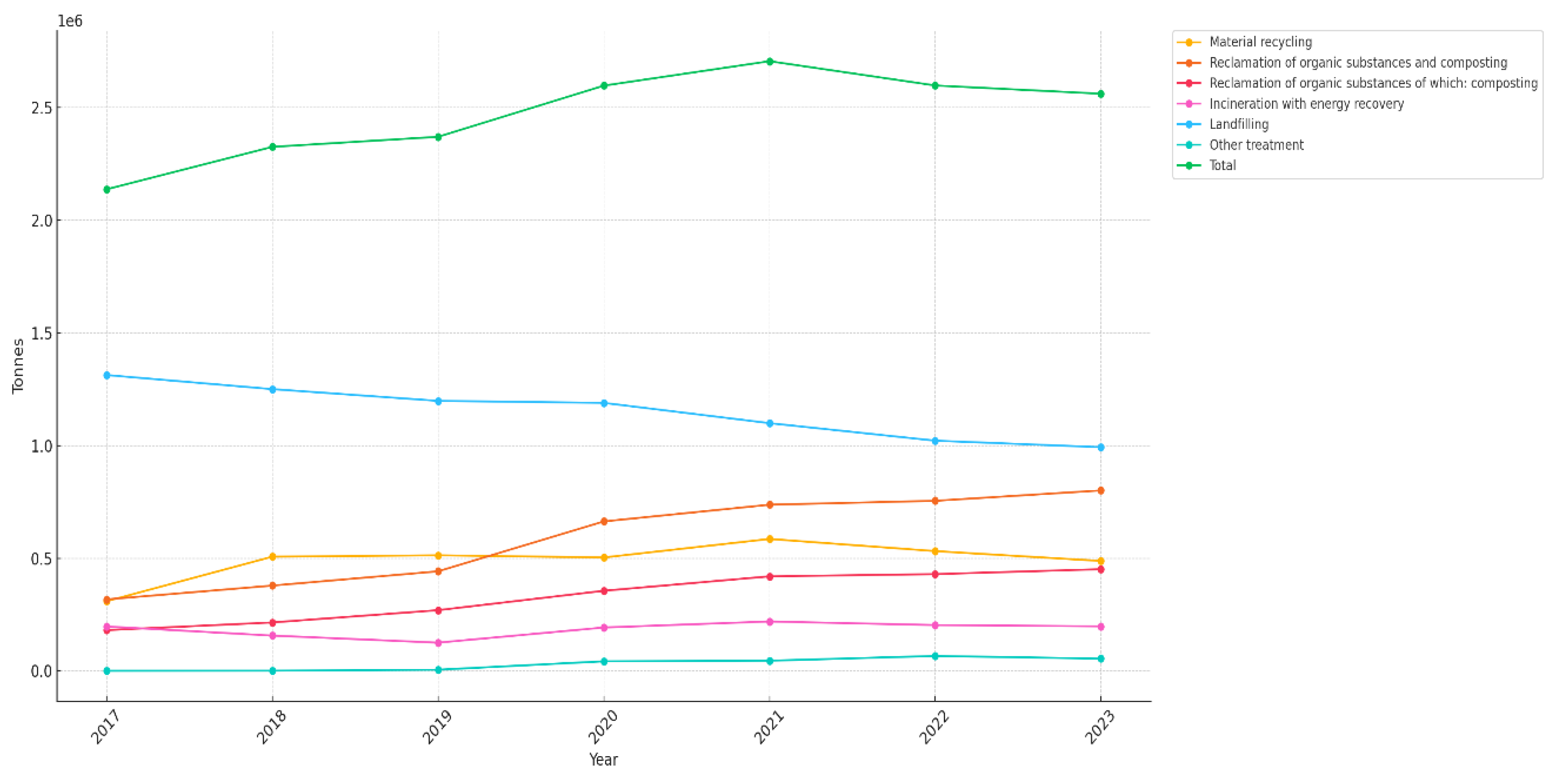

Municipal Waste Treatment Trends and Circular Economy Implications.

An examination of municipal waste treatment data from Slovakia between 2017 and 2023 reveals meaningful shifts in waste management practices aligned with CE principles, (

Figure 4), (

Appendix A). The annual total of municipal and small construction waste treated increased from approximately 2.14 million tonnes in 2017 to over 2.70 million tonnes in 2021, followed by a slight decline to 2.56 million tonnes in 2023. This trajectory suggests a general intensification of waste management activity over the observed period, likely influenced by EU directives and national policy measures encouraging circular approaches.

Among treatment methods, material recycling consistently accounted for a significant share, rising from 309,246 tonnes in 2017 to a peak of 585,578 tonnes in 2021, before slightly decreasing to 487,940 tonnes in 2023. This trend underlines ongoing investment and infrastructure development in municipal recycling systems, and reflects their centrality in CE strategies.

Equally notable is the role of reclamation of organic substances, particularly composting, which nearly doubled from 180,967 tonnes in 2017 to 451,322 tonnes in 2023. These figures demonstrate growing attention to bio-waste recovery as a pillar of CE-compatible waste diversion, reducing landfill dependence and contributing to nutrient cycles in local ecosystems.

Despite these positive developments, landfilling remained the dominant treatment method throughout the period, although its share has decreased from over 1.31 million tonnes in 2017 to 992,609 tonnes in 2023. This reduction indicates gradual progress in landfill avoidance, but also highlights the continued reliance on linear disposal practices that are at odds with CE goals.

Other treatment categories, such as incineration with and without energy recovery, other recovery, and other disposal, represent a small but non-negligible portion of the waste stream. Notably, incineration with energy recovery fluctuated moderately, with 197,895 tonnes processed in 2023, while incineration without energy recovery showed significant decline, reflecting environmental performance improvements.

Overall, the data reflect a slow but measurable transition toward circular waste treatment models. The increasing prominence of recycling and composting suggests positive policy impacts and behavioural shifts at the municipal level. However, persistent reliance on landfill underscores the need for stronger regulatory frameworks, financial incentives, and public-private collaboration to accelerate Slovakia’s transition to a fully circular waste management system [32, 33].

Hazardous Waste

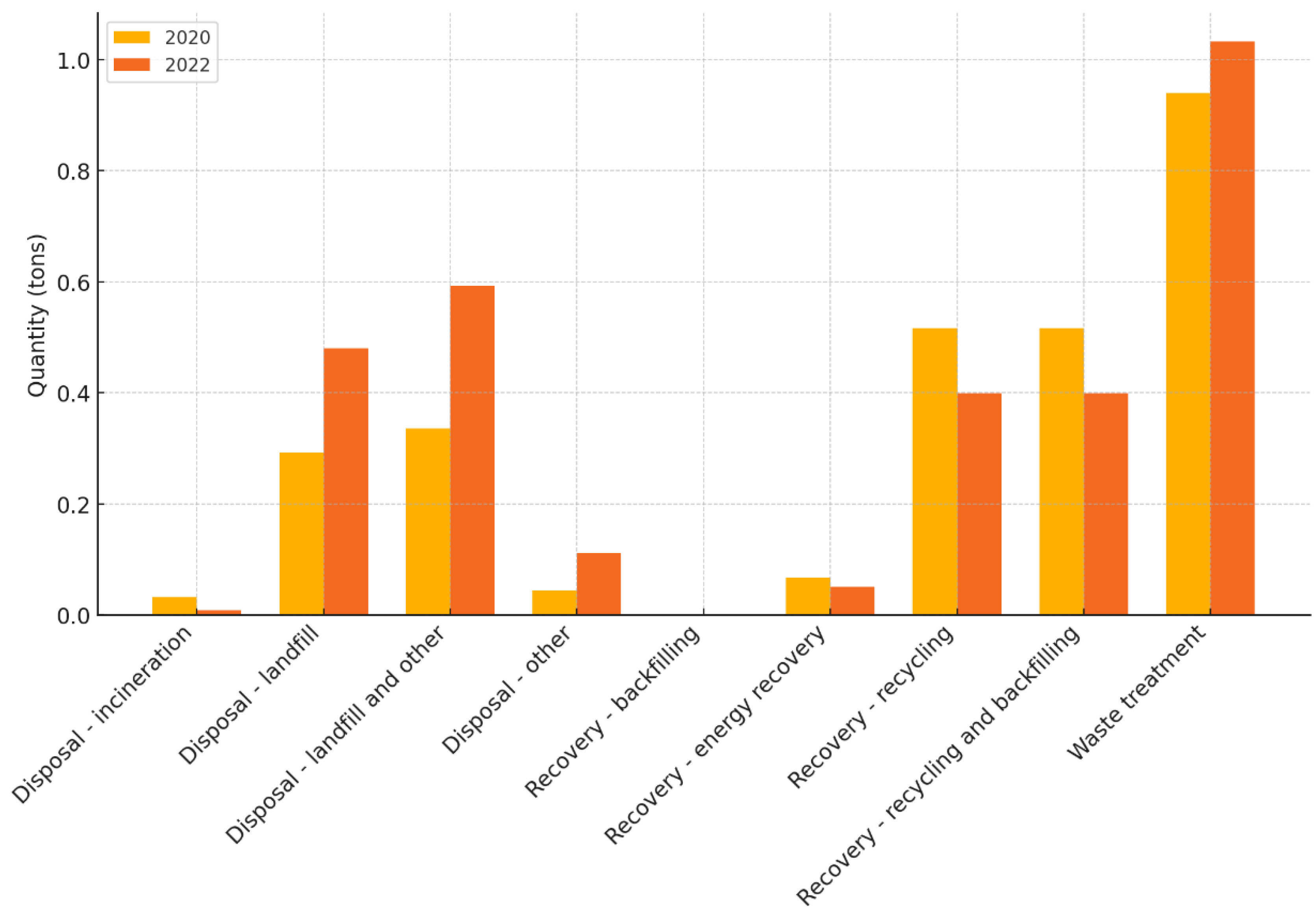

The management of hazardous waste across selected streams in Bratislava underwent significant variations between 2020 and 2022, (

Figure 5), (

Appendix A). A striking shift was observed in the disposal via landfill (D1, D5, D12) for acid, alkaline or saline wastes, which surged from 8,557 tonnes to over 3.2 million tonnes. This represents a staggering increase of over 37,000%, suggesting either a major reclassification of waste types or substantial changes in reporting practices. Similarly, the aggregated “landfill and other” category expanded over 17,000%, pointing to a broader reliance on disposal methods for this waste stream.

Conversely, incineration (D10) for the same category dropped precipitously from 281,255 tonnes to just 105 tonnes, indicating a potential shift away from thermal treatment—perhaps due to cost constraints or regulatory changes. Recovery efforts remained stable, with no recorded backfilling and consistent recycling volumes (over 7,800 tonnes). However, other disposal methods (D2–D4, D6–D7) were phased out entirely, dropping from 10,350 tonnes to zero. Overall, the trends highlight a mixed performance: while recovery volumes were maintained, the dramatic growth in landfill use for hazardous waste raises concerns regarding circular economy (CE) compliance and cost-efficiency.

Non-Hazardous Waste

The treatment of non-hazardous waste showed a divergent profile. For acid, alkaline or saline wastes, recycling sharply increased, from zero in 2020 to over 10,113 tonnes in 2022. This may reflect improved separation practices or expanded infrastructure for material recovery. However, landfill use also rose steeply—from 549 tonnes to 4,676 tonnes—suggesting that not all material was successfully diverted from final disposal.

In the case of chemical wastes, incineration remained minimal, while recycling jumped significantly from approximately 918 tonnes to over 5,289 tonnes—a 476% increase. Meanwhile, landfill disposal for this category continued to dominate in absolute terms, exceeding 27,500 tonnes by 2022. The growth in recycling, alongside sustained landfill reliance, indicates that although CE principles are gaining traction, systemic waste stream redesigns are still required to avoid persistent disposal dependency.

Total Waste (Hazardous and Non-Hazardous)

The aggregate category, combining both hazardous and non-hazardous fractions, provides a composite picture of the waste management trajectory. Notably, used oils maintained stable recycling rates (approx. 3,448 to 3,889 tonnes), while energy recovery plummeted from over 2,029 tonnes in 2020 to just 530 tonnes in 2022. This decline may point to disruptions in recovery technology or policy shifts disincentivising thermal conversion.

For chemical wastes, total recycling increased substantially from 7,820 to over 9,879 tonnes, reinforcing the growing capacity for material recovery. Yet this was paralleled by an increase in both landfill and other disposal, together accounting for more than 11,100 tonnes in 2022. Thus, while recycling infrastructure expands, disposal practices remain persistent, suggesting a lag in systemic circularity.

In total, the mixed performance across categories reflects a transitional phase in municipal waste governance. Recycling volumes are improving, particularly in the non-hazardous segment, but the enduring and in some cases increasing reliance on landfilling and incineration—especially for hazardous fractions—poses both financial and environmental risks. For municipalities like Bratislava, these dynamics underscore the urgent need to reinforce CE-aligned investments and regulatory coherence to shift waste management systems beyond legacy disposal paradigms [41, 42, 44].

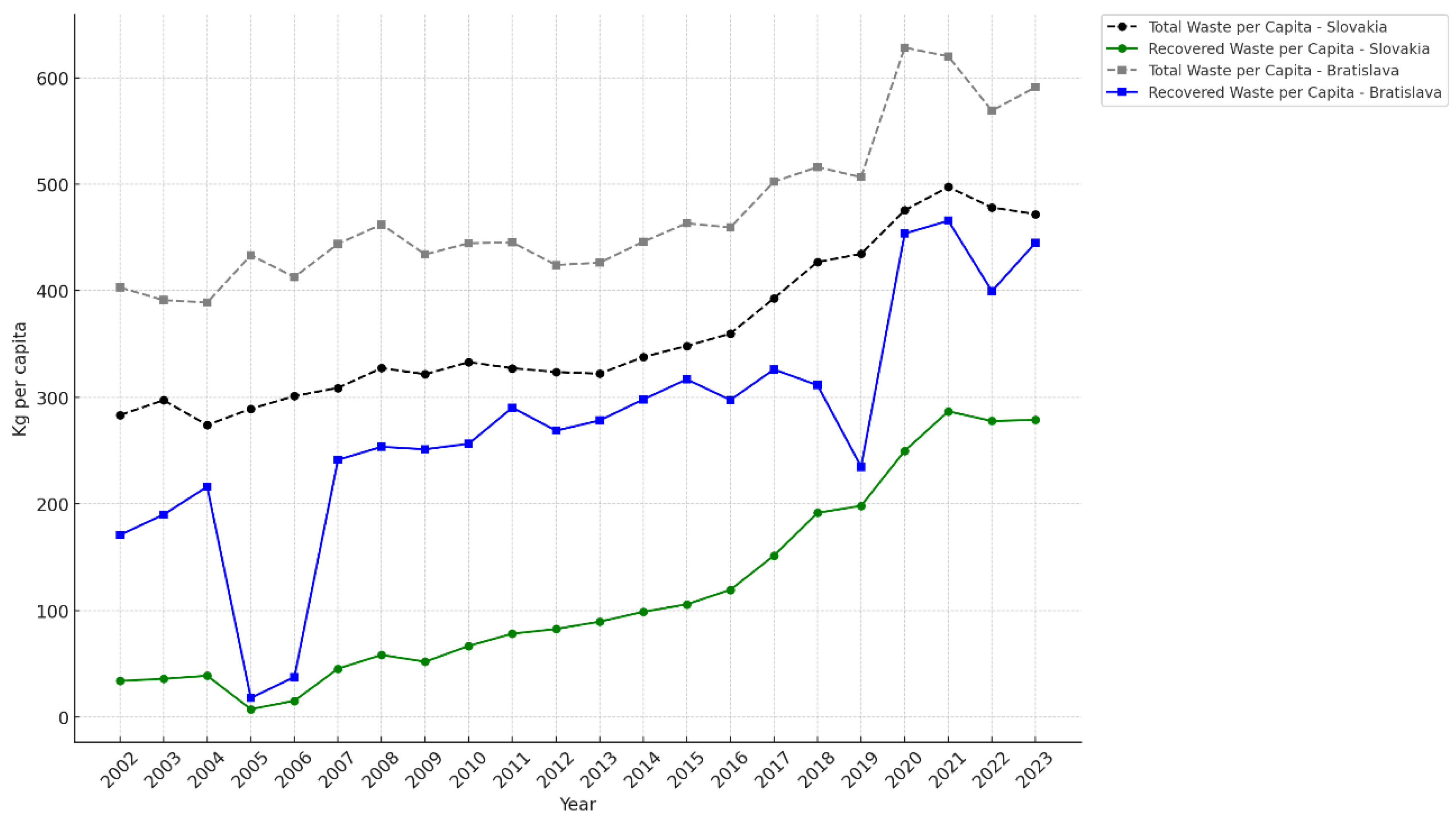

Analysis of Recovered and Total Municipal Waste per Capita in Slovakia and Bratislava.

An examination of municipal waste treatment trends in Slovakia and its capital region, Bratislava, over the period 2002–2023 reveals a significant transformation consistent with the objectives of CE policies, (

Figure 6), (

Appendix A). Two primary indicators are assessed: the amount of recovered municipal waste per capita, and the total amount of municipal waste generated per capita.

Over the past two decades, Slovakia has demonstrated a marked improvement in the recovery of municipal waste. The per capita recovery rate increased from 33.88 kg in 2002 to 278.91 kg in 2023, representing an eight-fold increase. During the same period, the total municipal waste per capita rose from 283.42 kg to 471.91 kg, a less dramatic but still substantial 66% increase.

This divergence implies a notable shift in waste management strategy—from linear disposal towards circular practices such as material recycling and organic recovery. The proportion of recovered waste relative to total waste has grown from approximately 12% in 2002 to 59% in 2023, demonstrating an expanding role of CE in national environmental governance.

These results suggest that financial investments into CE, as documented in environmental expenditure and sectoral investment records, have yielded tangible environmental performance gains. Furthermore, such trends imply greater opportunities for municipalities to derive income from recycling operations, reduce landfill costs, and comply with EU waste directives [37, 40, 43].

The Region of Bratislava, as the administrative and economic centre of the country, shows even more pronounced outcomes. In 2023, 445.08 kg of waste per capita was recovered, compared to a total generation of 591.06 kg per capita—translating to a recovery rate exceeding 75%. Back in 2002, recovered waste per capita in Bratislava stood at 170.9 kg, with total generation at 403.1 kg, indicating that the recovery ratio has grown significantly over the study period.

This impressive regional performance underscores the role of urban centres as frontrunners in CE implementation. It also highlights the financial and operational benefits of targeted CE investments at the municipal level, such as those in separate collection systems, recycling infrastructure, composting facilities, and public awareness campaigns [27, 30].

Implications for Municipal Governance

The quantitative trends observed offer robust support for CE-oriented governance strategies. Increased recovery rates directly correlate with:

- reduced fiscal pressure on landfill operations;

- new revenue streams from recyclables and secondary raw materials;

- improved environmental performance, potentially translating into EU financial incentives or lower compliance costs.

Municipalities adopting CE principles more rigorously, such as Bratislava, appear to benefit from greater waste recovery efficiencies and enhanced financial sustainability. These insights should guide future budget allocation decisions and policy frameworks supporting CE transitions.

Annual expenditures on municipal waste management in Bratislava exhibited fluctuations over the observed period, peaking at €29,091,952 in 2021, before significantly decreasing to €15,031,375 in 2023. This decline may reflect efficiency gains, budgetary adjustments, or reallocation of funds to other CE priorities. In contrast, revenue from secondary raw materials demonstrated a consistent upward trajectory, increasing from €644,613 in 2019 to €2,193,102 in 2023—an indication of improved resource recovery and market integration of recycled materials.

Investments in circular infrastructure displayed an irregular pattern, with a notable surge in 2021 (€3.5 million), coinciding with key initiatives such as KOLO reuse centres, ZEVO upgrades, and sorting plant developments.

The proportion of waste sent for recycling has markedly improved, rising from 36.04% in 2019 to 66.8% in 2023. This 30.76 percentage point increase reflects Bratislava’s progressive efforts in expanding sorting and recycling operations. The rate of source-separated waste collection more than tripled over the period, escalating from approximately 1.58 million operations in 2019 to over 5.57 million in 2023—highlighting an enhanced infrastructure and public participation in waste segregation.

Conversely, the total generation of mixed waste per capita decreased steadily, from 113,035.57 tonnes in 2019 to 93,460.55 tonnes in 2023. This suggests both behavioural change among citizens and institutional advancements in waste minimisation.