1. Introduction

Nanotechnology and nanoscience’s central part and essence have constantly been researching and developing nanostructures with unique and special features. BNNTs were first established in 1995, but since then, the production rates of BNNTs have been much lower due to their meagre yield and poor quality compared to CNT, which limits their practical uses (Kalay et al., 2015a). BNNTs have higher thermomechanical stability at high temperatures, although having a lower yield and high strength than CNTs (Byrne & Gun’ko, 2010; Ciofani et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2013; Meng et al., 2014; Pan et al., 2022; Steinke, 2022; Zhou et al., 1999). Due to very selective and limited research being carried out on BNNTs, it is recommended to establish a systematic research approach on BNNTs due to their superior mechanical, chemical, and thermal properties than those of CNTs. Moreover, the synthesis and the scaleup production methods of BNNTs are still left to be explored for further development and commercial applications (J. Zhang & Wang, 2016).

Figure 2.

a) 3-D structure of Boron Nitride Nanotubes, b) Sample of BNNTs and c) Several Molecular Properties of BN samples (S. H. Lee et al., 2020).

Figure 2.

a) 3-D structure of Boron Nitride Nanotubes, b) Sample of BNNTs and c) Several Molecular Properties of BN samples (S. H. Lee et al., 2020).

Despite the very selective methods for producing boron nitride nanotubes (BNNTs), including the arc discharge method, high-pressure laser heating, and oven-laser ablations, boron nitride nanotubes can be produced through a straightforward substitution reaction between nitrogen gas and boron oxide in the presence of carbon nanotubes (Kalay et al., 2015a). Such reactions are carried out by the induction-heating method using graphite-based susceptors (N. A. Ali et al., 2022; Loiseau et al., 1996; Lynch & Dawson, 2008; Rubio et al., 1994; Silveira et al., 2021a; Tiano et al., 2014; Y. Wang et al., 2017). Here, the emphasis has been given to the molecular structure, hybrid design, and BN concentration on BN-CNTs’ tensile properties throughout this study. It has been observed in the hybrid structures and composites of BN-CNTs that the Young Modulus of BN-CNTs usually decreases with the increase in the BN concentration. While the young modulus of BN-CNTs is primarily independent of the hybrid composition, which further affects the fracture strength and fracture strain sensitivity primarily with the variation in BN concentrations, thus leading to the tunable properties of BNNTs. The structural stabilities of Boron Nitride-Carbon Nanotubes composites are similar to that of CNTs. Their hybrid-style forming pattern and BN concentration are discovered to impact their formation energy and electrical characteristics significantly. To find the amount of research and development and the progress made in a particular research area, the best way is to analyse the number of papers published in that particular research area in previous years. Upon respective Scopus searches, we have observed that CNTs are extensively studied, accounting for being covered in more than 39526 publications since 2001. In comparison, graphene was discussed in 89235 publications being a relatively advanced material with selective applications. Interestingly, as per our observations, the Boron Nitride Nanotubes and Boron Nitride Nanosheets had no more than 827 publications from 2001 to 12th march 2024, thus opening a wide gap and a scope in Boron Nitride research and also revealing the ignorance in the whole research field when it comes to composites that can be formed from carbon nanotubes and can advance carbon nanotubes’ properties through its composites like BNNTs and BN-CNTs.

Figure 3.

Publications that covered Graphene, Boron Nitride Nanotubes, and Carbon Nanotubes [Source: Scopus Database (searched on 12th March 2024, 10 pm IST)].

Figure 3.

Publications that covered Graphene, Boron Nitride Nanotubes, and Carbon Nanotubes [Source: Scopus Database (searched on 12th March 2024, 10 pm IST)].

Taking account of the above-discussed properties and synthesis methods of CNTs and BNNTs, it becomes essential to consider BNNTs as a better alternative for CNTs, graphene and similar nanomaterials. In current research on BNNTs, studies have continuously shown one major challenge of BNNTs: the expensive production methods, due to which CNTs are still preferred over BNNTs. The expensive production costs can be significantly reduced if the BNNTs synthesis is subjected to the substitution reaction method, as shown in

Section 3.2. Decreasing the cost of production of BNNTs opens a broad scope of BNNTs and BN-CNTs to replace CNTs in applications like ballistic armours, hydrogen storage, biomedical applications, ceramics, etc.

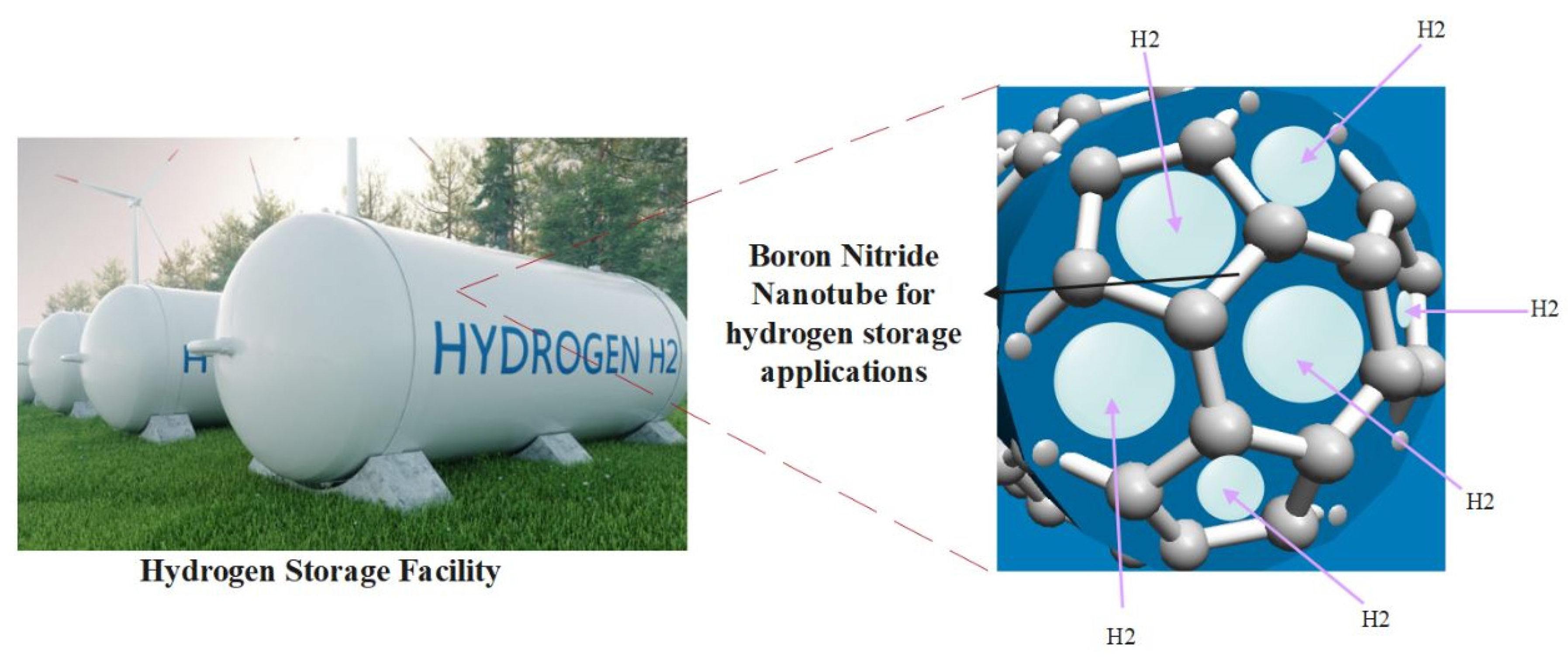

When it comes to the cost analysis and efficiency of BNNT-based ballistic vests, it was showcased that such vests can be formed at an affordable price of 120 USD as well as due to the extraordinary stiffness of BNNT, it can also be used in Level III+ protection and ceramic applications. Similarly, the appropriate small diameter and quality production of BNNT with adequate cytocompatibility also led to excellent biomedical applications (Doğan et al., 2023; Genchi & Ciofani, 2015; Merlo et al., 2018; Shadi & Hamedani, 2023). BNNT and other nanomaterials also replaced CNT-based sensors in forming novel sensor devices for humidity, CO2 detection, and clinical diagnosis. A unique application of BNNT, which completely changes the dynamics of CNT-based applications, was hydrogen storage, and it was found that the hydrogen bond penetrates more quickly in the B-N bond rather than the C-C bond resulting in better hydrogen storage capabilities than CNTs. All these application-based advantages of BNNT open a new platform to conduct more consistent BN-based research and commercialise such nanomaterials.

2. Boron Nitride Nanotubes and Boron Nitride Carbon Nanotubes: Properties

2.1. Boron Nitride Nanotubes

Boron Nitride material usually consists of an equal number of Boron and Nitrogen atoms that were only recently discovered and were usually considered synthetic earlier (Weng et al., 2016). Studying the materials forming thin hollow filaments ignited the research towards predicting and synthesizing boron nitride nanotubes. Based on their strength, high electronic band gap, and chemical inertness, BNNTs recently became the focus of recent experimentation and theoretical research (Dumitrică et al., 2004). Boron Nitride Nanotubes are electrical insulators with higher thermal and chemical properties than CNTs. BNNTs have low density, high thermal conductivity, excellent mechanical properties (with 900 GPa elastic modulus and 33 GPa tensile strength)(C. Gao et al., 2017), and high yield resistance. BNNTs usually have better chemical stability, oxidation resistance, room temperature resistivity, and fracture strain than CNTs. Under the experimental conditions of higher temperatures or even strong alkaline or acidic environments, the BNNTs remained stable. Their optical characteristics are incredibly excellent, making them be used in the deep-UV range instead of CNTs, often in the near-IR range. Due to the theoretical similarities between CNTs and BNNTs in terms of photon dispersion and Young’s modulus, it is suggested that the thermal conductivity of BNNTs can be compared to that of CNTs (C. W. Chang et al., 2006).

The Boron nitride nanotubes showed identical tubular nanostructures as carbon nanotubes (CNTs) (J. H. Kim et al., 2018). Typically, a hexagonal network is used to organize nitrogen and boron atoms. Excellent mechanical strength with electrically insulating behavior, great oxidation resistance, neutron shielding capability, and piezoelectric properties are some of the intrinsic properties of Boron nitride nanotubes (BNNTs) (Tiano et al., 2014). As per

equation (1), Young’s modulus E is directly proportional to L

4. Hence, it highly depends on the length, making it more sensitive for short nanotubes (Suryavanshi et al., 2004).

Where E is the effective elastic modulus, d1 is the outer diameter, d2 is the inner diameter, L is the length of the nanotube, is the boundary condition constant and fi is a resonance frequency for the harmonic resonance mode i and the observed density is 2180 kg/m3 for boron nitride nanotubes.

Figure 4 discusses the various graphene sheets, nano-cones, cone-sheets and nanotubes possible with C-C and B-N bonds. When the boron nitride nanotube structure was built, the tube length and bond length was taken out to be 25 units and 1.47 units, whereas in CNT, tube length and bond length were taken out to be 25 units and 1.421 units. This also proves that the B-N bond lengths are slightly more than the C-C bond length, whose applications will be discussed later. For the CNTs, the nanotube consisted of 240 atoms and 340 bonds with a chirality of (10,0) and a tube diameter of 7.834 A. Whereas for BNNTs, the nanotube consisted of 230 atoms and 330 bonds with a chirality of (10,0) and a tube diameter of 8.105 A (Deshwal & Narwal, 2023; Lu et al., 2023).

Figure 4.

Various Simulated patterns and respective geometries based on C-C and B-N. The structures such as nanotubes, graphene sheets, nanocones and cone sheets were considered for simulations (Deshwal & Narwal, 2023; Lu et al., 2023).

Figure 4.

Various Simulated patterns and respective geometries based on C-C and B-N. The structures such as nanotubes, graphene sheets, nanocones and cone sheets were considered for simulations (Deshwal & Narwal, 2023; Lu et al., 2023).

When it comes to pure BNNTs, they are semiconductors irrespective of diameter, chirality or the number of walls of the tubes (single-walled or multi-walled). It is also stated that the F-doped BNNTs (multi-walled), when synthesized experimentally, are p-type semiconductors (Xiang et al., 2005). There are also changes in the binding energies of BNNTs, once they are attached to CCl2. CCl2 decrease the binding energies of BNNTs, whereas it does not change the electronic properties of BNNTs (Li et al., 2008).

Figure 5.

Summary of the comparative analysis of BNNTs and CNTs (Pumera, 2009; M. Wang et al., 2020) related to the optical properties, mechanical strength, color, etc.

Figure 5.

Summary of the comparative analysis of BNNTs and CNTs (Pumera, 2009; M. Wang et al., 2020) related to the optical properties, mechanical strength, color, etc.

2.2. Boron Nitride Carbon Nanotubes (BN-CNTs) Composites

These BN-CNT composites’ density and specific surface area can be modified by varying the proportion of CNTs in the composites (J. Zhang & Wang, 2016). Due to their excellent insulating qualities, unique luminescence materials, photodetector, and reusable substrates for surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy, hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN) based materials exhibit high resistance to oxidation. These materials can be used in harsh and protective materials like ballistic materials. There are numerous reports of tailoring the properties of biopolymers and complex polymers and their nanocomposites for high-end applications, imparting extra strength or enhanced stabilization of polymer matrix for prolonged applications (Aiyer et al., 2016, 2019; Kushwaha et al., 2015a, 2015b; Singh & Kushwaha, 2013a).

The main cons of hexagonal-BN materials are that they are expensive, production non-scalability and functional simplification, so specific strategies like in-situ functionalization are used to overcome them (J. Wang et al., 2010; M. Wang et al., 2020). The appropriate mixtures of h-BN nanoparticles and C-based materials improve carbon-based materials’ total microwave absorption capabilities. Pore density in h-BN/carbon composites lowers density and enhances the micro-absorption capabilities of the materials.

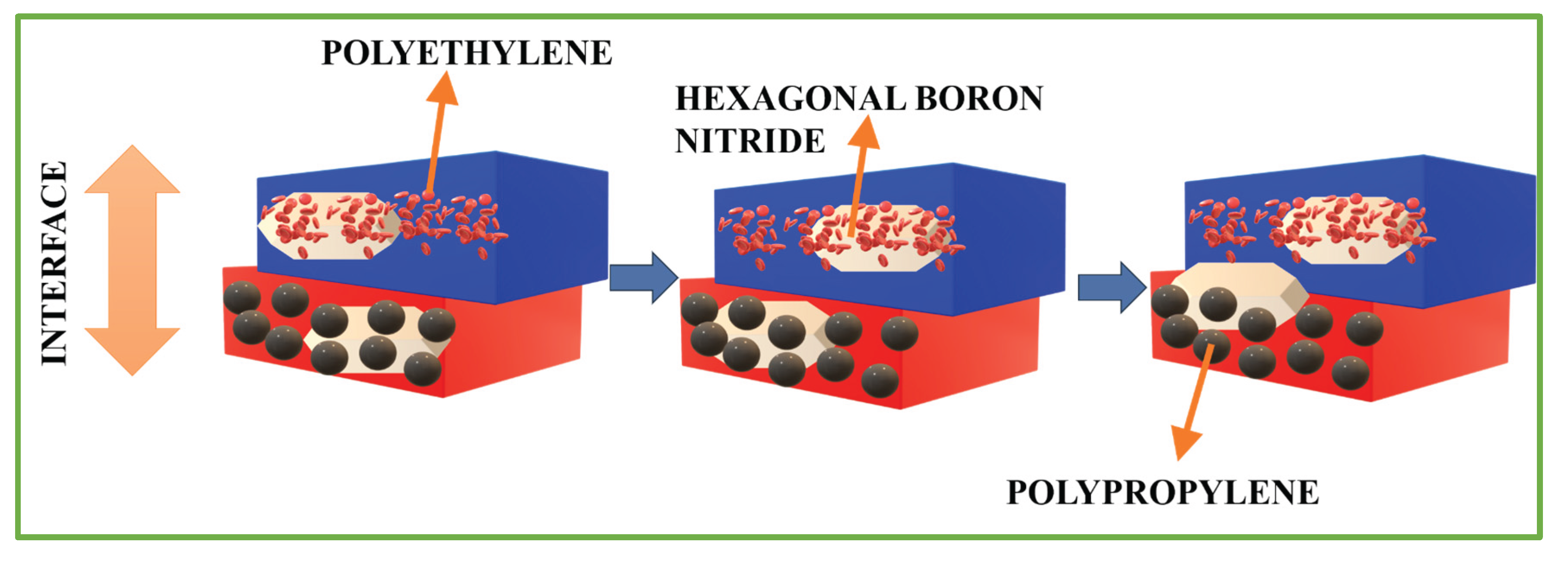

In Figure 6, the in-situ exfoliation occurs due to the melt compounding with PE and PP. The surface tension values of polyethene, polypropylene and boron nitride are mentioned in Table 1 (Qu et al., 2023).

Figure 6.

In-situ exfoliation mechanism of hexagonal boron nitride due to polyethene (PE) and polypropylene (PP) melt compounding (Qu et al., 2023).

Figure 6.

In-situ exfoliation mechanism of hexagonal boron nitride due to polyethene (PE) and polypropylene (PP) melt compounding (Qu et al., 2023).

Table 1.

Characterization of surface tension values of PE, PP and Hexagonal boron nitride (J. Wang et al., 2010).

Table 1.

Characterization of surface tension values of PE, PP and Hexagonal boron nitride (J. Wang et al., 2010).

| Material |

Surface Tension Characterization |

| Polypropylene (PP) |

39 mN/m |

| Polyethylene (PE) |

37 mN/m |

| Hexagonal Boron Nitride |

46 mN/m |

If pure CNTs are used rather than h-BN/CNTs materials, it will cause a mismatch in impedance due to their high dielectric properties (Adeel et al., 2019). Such BN-CNT composites are usually thin and lightweight, with excellent absorption and broad bands. Regarding the structural stabilities of BN-CNTs, they are very similar to CNTs. However, as discussed earlier, the main difference comes from the hybrid style forming a pattern and the BN- concentration, which improves the formation energy and the electrical characteristics of BN-CNTs.

3. Synthesis of BNNTs and BNCNTs

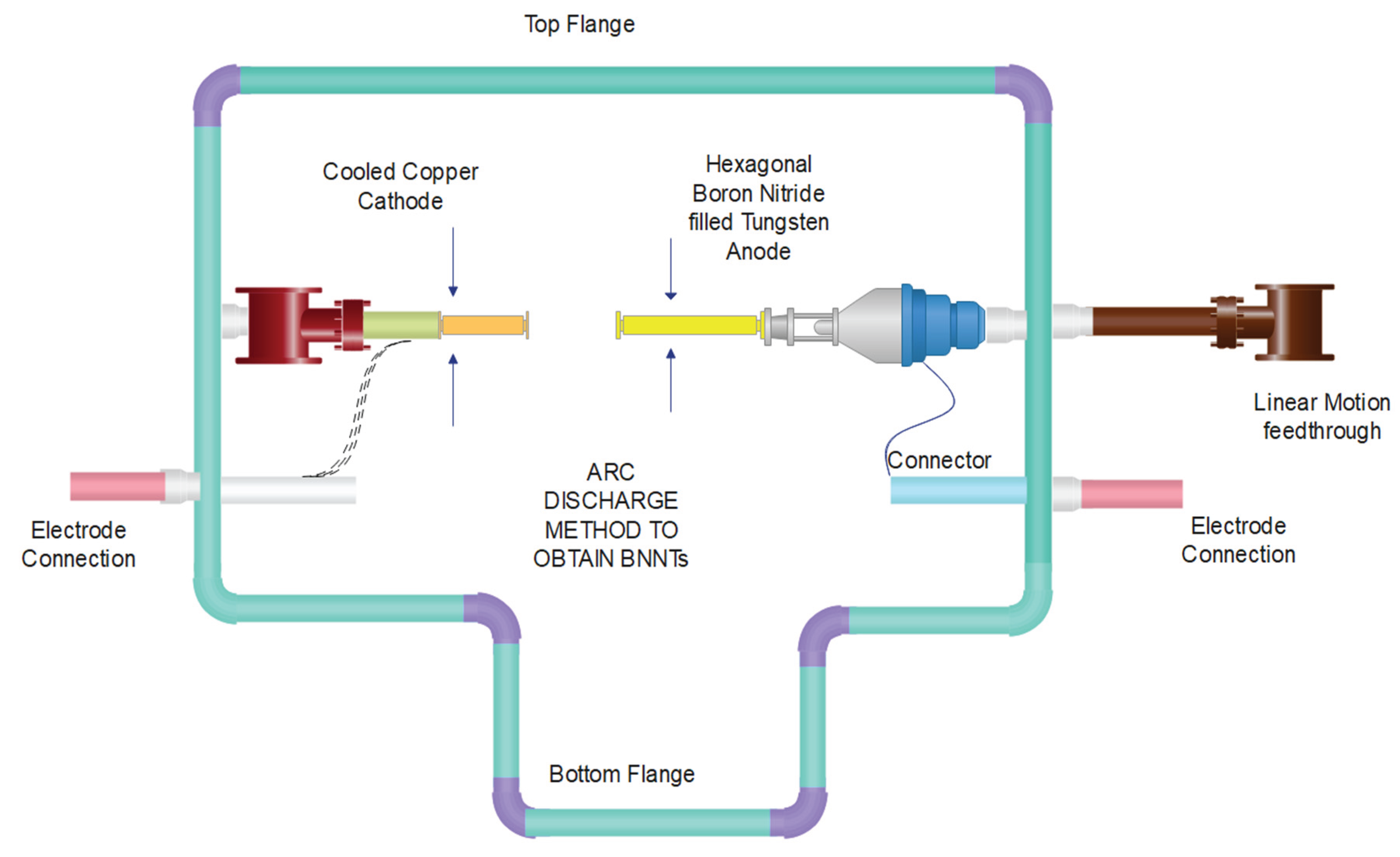

3.1. Arc Discharge Method

The Arc Discharge Method was one of the first techniques used to create BNNTs. In the past, the anode in an arc discharge method was a hexagonal tungsten rod filled with BN, while the cathode was a copper cathode that had been cooled. After some time, BNNTs with a dark grey colour were removed from the cathode’s surface. BNNTs are created using conductive boron materials and hafnium bromide electrodes (Kalay et al., 2015a). The engineering aspect of the room-sized standard arc-discharge method is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Schematics of a standard room-size scaled version of the Arc Discharge unit to obtain Boron Nitride Nanotubes (BNNTs) (Yeh et al., 2017).

Figure 7.

Schematics of a standard room-size scaled version of the Arc Discharge unit to obtain Boron Nitride Nanotubes (BNNTs) (Yeh et al., 2017).

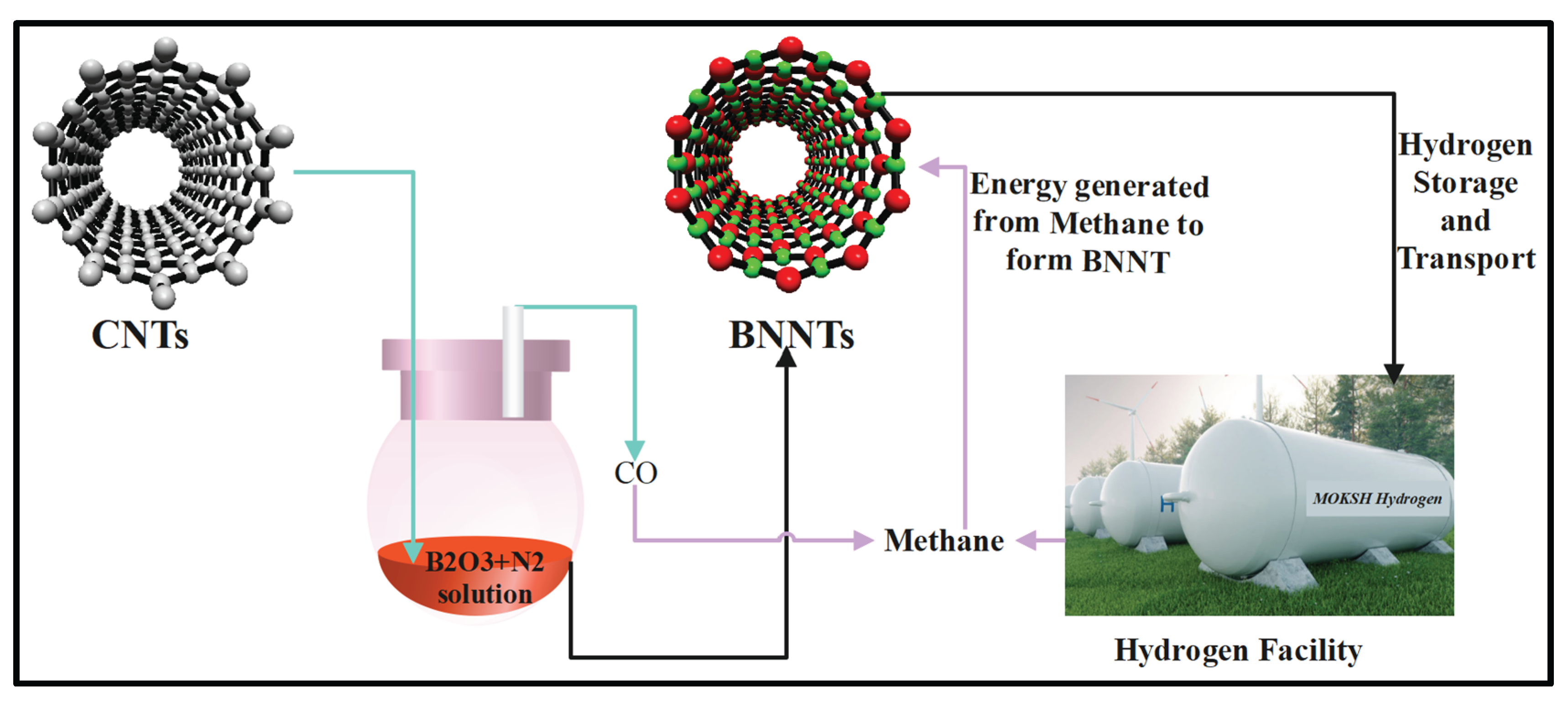

3.2. Substitution Reaction

One of the significant issues in forming BNNTs is the lower yield it usually has during the synthesis. Substitution Reaction is one of the simple ways to obtain high yields of BNNTs (R. D. Goldberg et al., 1999). The reaction of CNTs and B2O3 in the N2 Atmosphere at 1773K gives high yields of BNNTs.

The Substitution Reaction used is

In

Figure 8, a laboratory-level setup has been showcased, in which some amount of CNTs is dissolved in boron oxide and nitrogen solution at the desirable temperature and pressure condition, through which BNNTs, composites of boron nitride carbon nanotubes (based on the completion of reaction) and carbon monoxide are formed. The carbon monoxide released is mixed with hydrogen under optimum thermodynamics to form syngas, which is distilled further to separate methane from the syn gas, which is later used as an energy source in various applications.

Figure 8.

Laboratory-level production of BNNTs from Substitution reaction.

Figure 8.

Laboratory-level production of BNNTs from Substitution reaction.

The different kinds of methods through which filling, confined reaction, and coatings can also be classified as conventional methods for producing boron nitride nanotubes from carbon nanotubes. Although, as shown in

Figure 9, the most appropriate and best method for converting carbon nanotubes into boron nitride nanotubes is the proposed

“Substitution Reaction Method”.

Figure 9.

Diagrammatic representation of a comparison of Previous and Present work of CNTs to form 1D Nanoscale Materials (Kalay et al., 2015a).

Figure 9.

Diagrammatic representation of a comparison of Previous and Present work of CNTs to form 1D Nanoscale Materials (Kalay et al., 2015a).

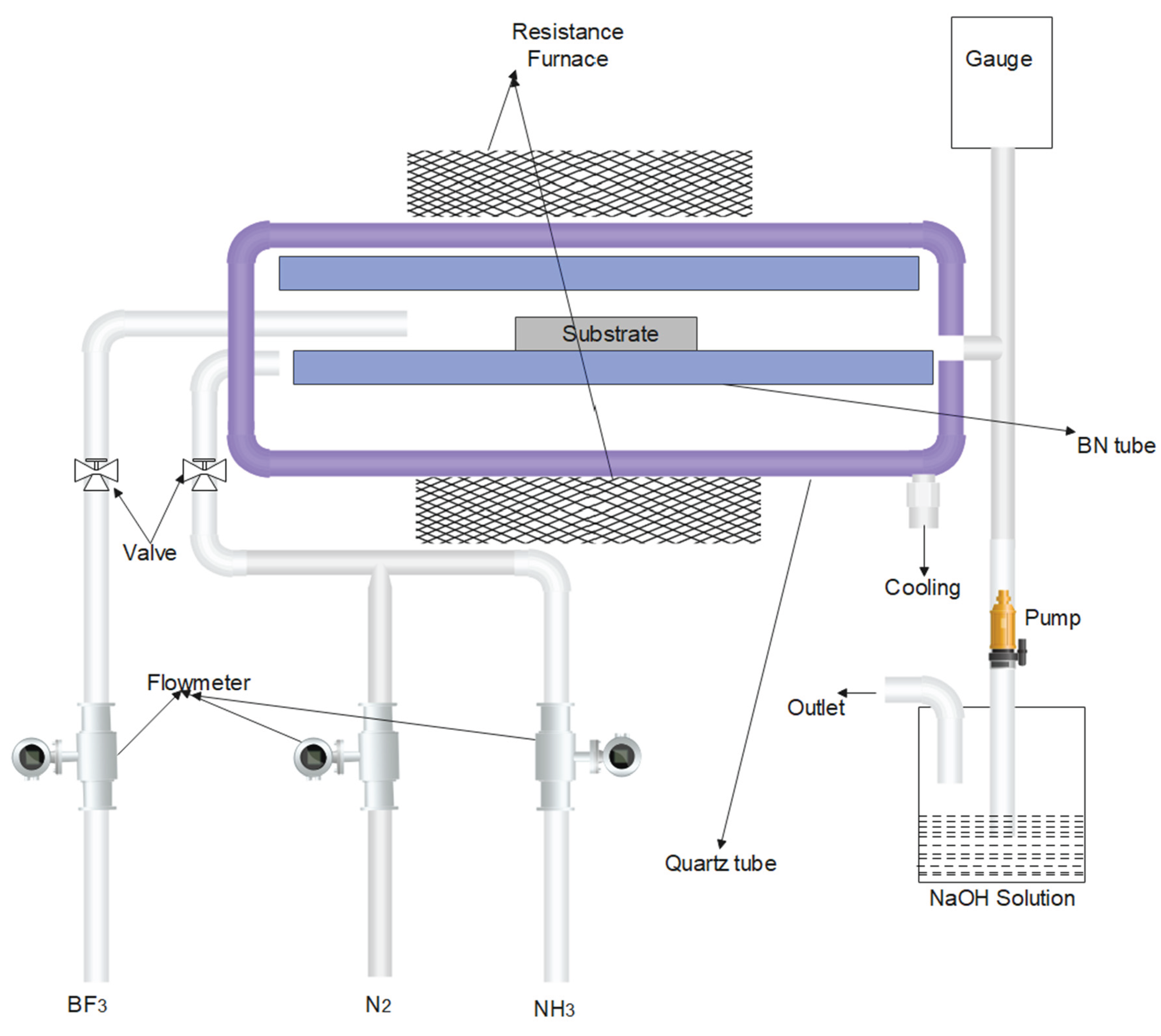

3.3. Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD)

One of the economical and high-yield methods to obtain BNNTs is Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD). To synthesize BNNTs, Borazine(B3N3H6) needs to be obtained from Ammonium sulphate [NH4(SO4)2] and Sodium Borohydride (NaBH4). B3N3H6 and decaborane can then be precursors to form BNNTs (Ahmad et al., 2015). Such synthesis methods are used for tailored growth of 2D hexagonal boron nitride. CVD is also one of the most controllable methods for synthesising BNNTs (H. J. Kim et al., 2022; C. H. Lee et al., 2008; J. Lee et al., 2007; Lonkar et al., 2012; Matsuda et al., 1986, 1988; Q. Shi et al., 2018; Y. Shi et al., 2010; Sun et al., 2018). The overall working and schematic process engineering representation of Chemical Vapor Deposition is shown in Figure 10 (Arenal et al., 2007).

Figure 10.

Schematic Representation of Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) to Synthesize BNNTs (Ahmad et al., 2015; Ma et al., 2001).

Figure 10.

Schematic Representation of Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) to Synthesize BNNTs (Ahmad et al., 2015; Ma et al., 2001).

3.4. Laser Ablation Method

Only the laser vaporization process can produce single-walled BNNTs, also known as SWBNNTs. Under high N2 pressure, it is possible to synthesize BN into multi-walled BNNTs with 3 to 8 walls (Maselugbo et al., 2022). Using a BN substrate and a continuous wave CO2 laser with 500 W of power, MWBNNTs can be obtained, whereas SWBNNTs can also be synthesized from a continuous wave CO2 laser (Cau et al., 2008; D. Goldberg et al., 1997; Z.-C. Huang et al., 2022; Jia et al., 2012; Millinger et al., 2017; Suryavanshi et al., 2004; Zhou et al., 1999). The production setup of the laser ablation method is shown in Figure 11, which portrays the engineering methods of production of BNNTs with maximum output (Yu et al., 1998).

Figure 11.

Representation diagram of Laser ablation method to synthesize BNNTs (Maselugbo et al., 2022).

Figure 11.

Representation diagram of Laser ablation method to synthesize BNNTs (Maselugbo et al., 2022).

3.5. Ball Milling Method

Milling vessels and Fe-based stainless-steel balls are used in the ball milling method, where the impure Fe is used as a catalyst for BNNT generation (Andreasen et al., 2005; J. Kim et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2009; Meethom et al., 2020). It is based on a simple three-step experimental procedure: C-boron powder with an average mesh size of 60 undergoes high energy ball milling of 300-1000 rpm and finally annealing at 1100-1200 °C, as shown in Figure 12 (C.-P. Chang et al., 2021; Chen et al., 1999; J. Kim et al., 2011; J.-Y. Kim et al., 2010; Li et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2009; Schmitz et al., 2023).

Figure 12.

Flow Diagram of Ball Milling Method to Synthesize BNNTs (J. Kim et al., 2011).

Figure 12.

Flow Diagram of Ball Milling Method to Synthesize BNNTs (J. Kim et al., 2011).

Figure 13.

Various Types of synthesis methods of BNNTs (J. H. Kim et al., 2018).

Figure 13.

Various Types of synthesis methods of BNNTs (J. H. Kim et al., 2018).

4. Scale Up Process Model for Boron Nitride Nanotubes and Boron Nitride Carbon Nanotubes

When we consider the scale-up models for boron nitride nanotubes, one of the most feasible and multi-application-based synthesis methods is the Substitution reaction method based on the reactions of boron oxide, nitrogen and Carbon Nanotubes.

Suppose we look at a scale-up of creating 2,00,000 kgs of Boron Nitride Nanotubes at an industry level. We would require a lot of estimations and approximations. When we look at producing 2,00,000 kgs of BNNTs in a year, we can divide it into 300 working days and production of approximately 700 kgs of BNNTs per day. For the production of 2,00,000 Kgs, the ideal CNTs requirement is 3,00,000 Kgs which is 1TPD (tonnes per day), whereas realistically, we would require an approximate 4,00,000 Kgs of CNTs as a reactant, which is approximately 1333.33 Kgs of CNTs per day (An et al., 2023; Kong et al., 2024; Zhao et al., 2023).

Table 2 shows that the total cost of the development of the Boron Nitride Plant to generate electricity and boron nitride will cost 3200 Crores INR. Whereas Table 3 demonstrates the value generated in the first year. By slowly replacing Carbon Nanotubes after the first year by generating its electricity, the plant can run over by both scale-up substitution reaction and Chemical Vapor Deposition, reducing the cost of CNTs by half and creating a 1500 Crores profit after the first year. This concludes that we require 1333.33 kgs of CNTs daily, which can be synthesised using ample amounts of green, sustainable and zero-emission methods or bought as ready products from the market. 1333.33 kgs of CNT will require roughly 2.5 tonnes of Boron Trioxide and 1 ton of Nitrogen gas. To form different forms of Boron nitride carbon nanotube composites, the weight of CNTs can be altered. Different compositions can be attained for this composite based on the industrial and application requirement.

Table 2.

Cost analysis of Industrial plant production of BNNTs and BNCNTs in INR per year (An et al., 2023; Kalay et al., 2015b; Ko et al., 2023; Kong et al., 2024; Naclerio & Kidambi, 2023; Pakdel et al., 2014; Qu et al., 2023; Tay et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2023).

Table 2.

Cost analysis of Industrial plant production of BNNTs and BNCNTs in INR per year (An et al., 2023; Kalay et al., 2015b; Ko et al., 2023; Kong et al., 2024; Naclerio & Kidambi, 2023; Pakdel et al., 2014; Qu et al., 2023; Tay et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2023).

| Materials Required |

Weight (in tons) |

Cost (INR) (in Crores) |

| Carbon Nanotubes |

400 |

3120 |

| B2O3

|

750 |

18.75 |

| Nitrogen generator (to extract nitrogen from the air) |

300 |

0.5 |

| Reactor |

5 |

1 |

| CO storage tank |

5 |

0.5 |

| Hydrogen Storage |

5 |

0.5 |

| Distillation column |

5 |

1 |

| Methane Storage |

2 |

0.25 |

| Chemical Vapor Deposition Model |

10 TPD |

0.5 |

| Man Power |

1000 people |

50 |

| Additional Costs |

Automation, Computers |

5 |

| |

Total |

3200 (Approx.) |

Table 3.

Amount of worth generated from the plant for the first year (An et al., 2023; Kalay et al., 2015b; Ko et al., 2023; Kong et al., 2024; Naclerio & Kidambi, 2023; Pakdel et al., 2014; Qu et al., 2023; Tay et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2023).

Table 3.

Amount of worth generated from the plant for the first year (An et al., 2023; Kalay et al., 2015b; Ko et al., 2023; Kong et al., 2024; Naclerio & Kidambi, 2023; Pakdel et al., 2014; Qu et al., 2023; Tay et al., 2023; Zhao et al., 2023).

| Material |

Weight (in tons) |

Worth (INR) (Crores) |

| Boron Nitride Nanotubes |

200 |

1000 |

| Carbon Monoxide (generating Electricity via Methane as energy fuel) |

1000 |

1 |

| Energy used to produce BNNTs solely |

400 |

2000 |

The process done in the reactor will produce roughly 0.7 tonnes of BNNT per day, estimating up to 200 tonnes of BNNT and 1000 tonnes of carbon monoxide. This amount of carbon monoxide can be stored and have multiple applications. One of the applications proposed is the reaction of carbon monoxide with hydrogen to form syngas. The syngas produced from this will be sent into distillation, from which methane will be separated (Hayat et al., 2022; Vatanpour et al., 2021). The methane formed from this can also be referred to as partially biomethane or green methane if the synthesis methods of CNT are green. This methane can be used to fuel energy which can be used in many electricity applications from which BNNT can be solely produced without the help of CNTs as the primary reactor (Maestre et al., 2021).

Figure 14 showcases a scale-up project plant to produce boron nitride nanotubes and electricity. The first reaction unit until the reactor consists of a scale-up substitution reaction which is divided into BNNTs and CO; the BNNTs are stored, whereas the CO is utilised by the formation of syngas with the help of a hydrogen storage facility, the syngas then undergoes distillation through which methane is separated, this methane is then used as an energy source to produce electricity which is used in the CVD to produce BNNTs and can also be used in other electricity applications such as running the whole plant as well.

Figure 14.

BNNT Scale Plant process and schematic diagram showing syn gas and methane generation (An et al., 2023; Ko et al., 2023; Kong et al., 2024; Tay et al., 2023; Vatanpour et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2023).

Figure 14.

BNNT Scale Plant process and schematic diagram showing syn gas and methane generation (An et al., 2023; Ko et al., 2023; Kong et al., 2024; Tay et al., 2023; Vatanpour et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2023).

Such scale-up of boron nitride nanotubes has not been attained and proposed yet. However, suppose research and development are done on such industrial expansion of the production of boron nitride nanotubes. In that case, the synthesis cost can be automatically decreased, making BNNTs and BNCNTs cheaper.

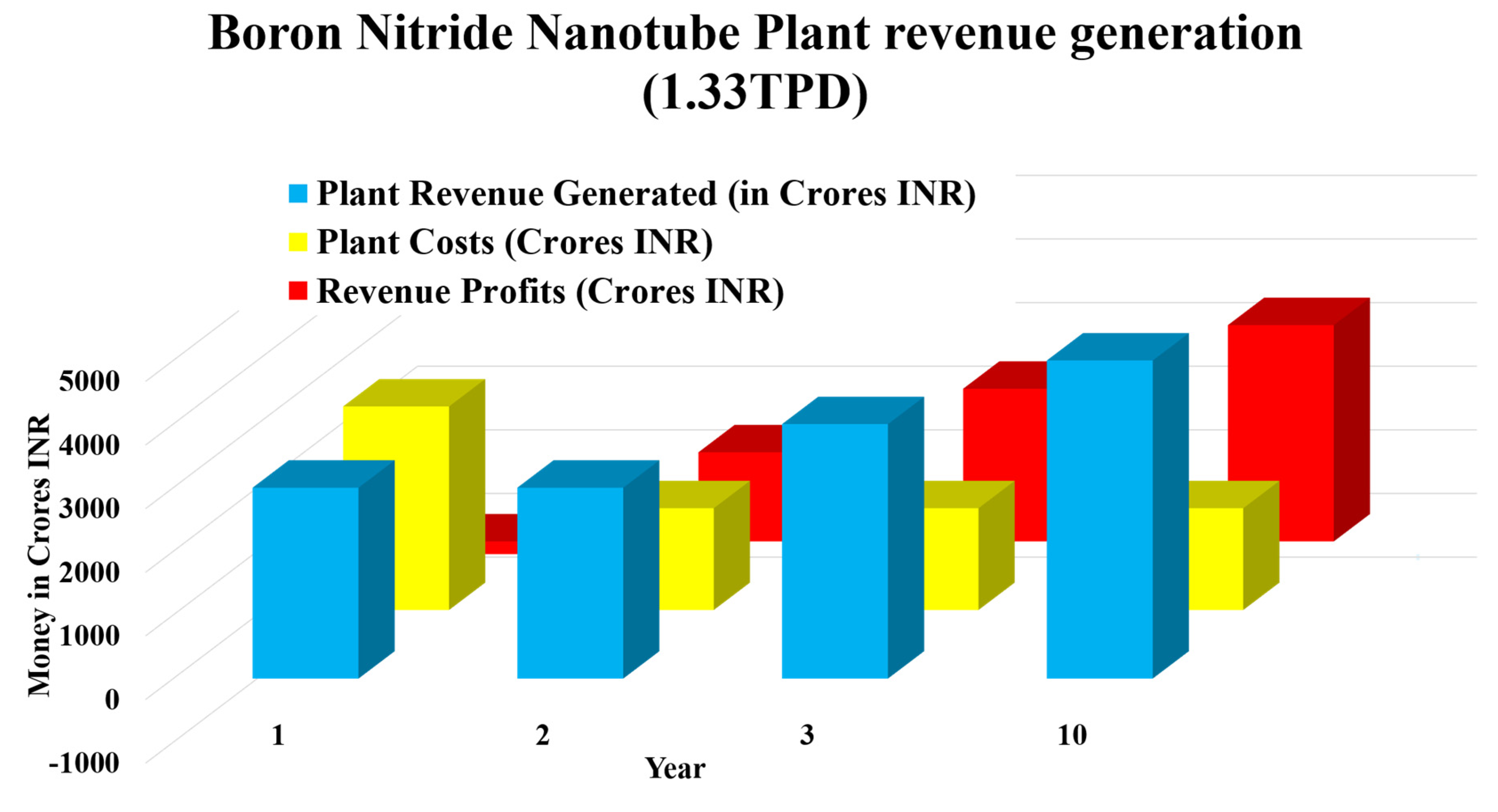

The graphical representation done in Figure 15 is done by taking the necessary calculations for the plant costs and revenue generation, the total net profits by the revenue generated were calculated, and the net profits showcased an immense increase in the profits from a loss of 200 crores in the first year to an increase to 1400 crores in the next year due to partial independence from CNTs and deploying self BNNT production methods like CVD (Naclerio & Kidambi, 2023; Tay et al., 2023). At the end of 10 years of a full working model, it is expected to have a 3400 crores INR profit from it, which proves that BNNT has the clear potential to become the next global economy at the highest level if we scale up the process of the synthesis methods of BNNTs.

Figure 15.

Boron Nitride Nanotube revenue generation projection for the first ten years (Naclerio & Kidambi, 2023; Tay et al., 2023).

Figure 15.

Boron Nitride Nanotube revenue generation projection for the first ten years (Naclerio & Kidambi, 2023; Tay et al., 2023).

5. Applications of BNNTS and BNCNTS

5.1. Application of Boron Nitride Nanotubes

5.1.1. Polymer Dielectric Composites of BNNTs

Polymer dielectrics are unreliable in hot temperatures because of their poor mechanical integrity and thermal durability. Therefore, due to their great mechanical integrity and respective thermal stability, 1D polyaramid nanofibers and 2D BNNTs are advantageous (Adeel et al., 2019). These reinforced nanocomposite sheets typically have a high degree of flexibility, mechanical strength, electrical insulation, and thermal conductivity over a broad temperature range. Typically, 2D BNNS has a high thermal conductivity. Previously cruel materials, 2D BNNS and 1D PANF (which have great mechanical integrity and electrical insulation) can now be utilised for very high-temperature applications and for people to enter somewhat hotter environments.

5.1.2. Polymer Composite Reinforcement, Ceramics, and Lightweight Armors

BNNTs exhibit some of the most extraordinary stiffness, demonstrating their potential for use in ceramics and polymeric composites. These materials typically have Young’s modulus of 1.2 TPa (Agrawal et al., 2013). Covalently functionalized nanotubes have proven to be practical additions for polymer reinforcing. However, higher percolation values result from adding nanotube functionalisation to polymers. For bulletproof vests to be cost-effective, new, ultra-strong polymer nanotube materials require enormous amounts of CNTs and BNNTs (C.-P. Chang et al., 2021; Z. Huang et al., 2014; Meng et al., 2014; M. Wang et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2023).

When the cost analysis was done for the boron nitride nanotubes-based bulletproof vest in Table 4, it was highlighted that an inexpensive and lightweight armour of 5 Kgs could be formed in just 10121.5 INR (approximately 120 USD), which can also give a level III+ protection, thus protecting from a pistol, Sten MC, SLR, INSAS and AK make assault rifles. Such affordable and lightweight armour is yet to be produced and researched, and the cost analysis can be the start of one of the most protective bulletproof vests (Cavallaro P.V, 2011; Davis, 2012; Dresch et al., 2021; Y. S. Lee et al., 2003; Luz et al., 2015, 2017; Nurazzi et al., 2021; Risby et al., 2008; Salman & Leman, 2018; Silveira et al., 2021a, 2021b; Soorya Prabha et al., 2021; Vignesh et al., 2021; Walley, 2014; Wambua et al., 2007; Zochowski et al., 2021).

Table 4.

Cost analysis of a Bulletproof vest made from Boron Nitride Nanotubes (Bilisik & Syduzzaman, 2022; Luz et al., 2017; Medvedovski, 2010; Mylvaganam & Zhang, 2007; Nguyen et al., 2020; Odesanya et al., 2021; Soorya Prabha et al., 2021; Steinke, 2022; Talebi, 2006; Vidya et al., 2020; Vignesh et al., 2021; Zochowski et al., 2021).

Table 4.

Cost analysis of a Bulletproof vest made from Boron Nitride Nanotubes (Bilisik & Syduzzaman, 2022; Luz et al., 2017; Medvedovski, 2010; Mylvaganam & Zhang, 2007; Nguyen et al., 2020; Odesanya et al., 2021; Soorya Prabha et al., 2021; Steinke, 2022; Talebi, 2006; Vidya et al., 2020; Vignesh et al., 2021; Zochowski et al., 2021).

| Material for Optimum Bulletproof Vest |

Cost (INR) |

| Steel (10mm) (2kg) |

146.5 |

| Body Armor Plate (2.5kg) |

5000 |

| Rolling Tolerance (7-6mm) |

100 |

| Rubberised Trap |

300 |

| Trauma Pad (45 grams) |

75 |

| Boron Nitride Nanotube |

4500 |

| Total (5kg bulletproof vest) |

10121.5 |

The oxidation resistance shown by BNNTs is much higher than that of CNTs, making it more accurate to be used in many nanomaterials, protective shields like bulletproof vests, and nanodevices for its application in high temperatures, extreme conditions or under hazardous and corrosive environments (Aharonian et al., 2021; Asyraf et al., 2022; Bhat et al., 2021; C.-P. Chang et al., 2021; Ellis. L R, 1996; Fayed et al., 2021; Nascimento et al., 2017; Nyanor et al., 2018; Sliwinski et al., 2018).

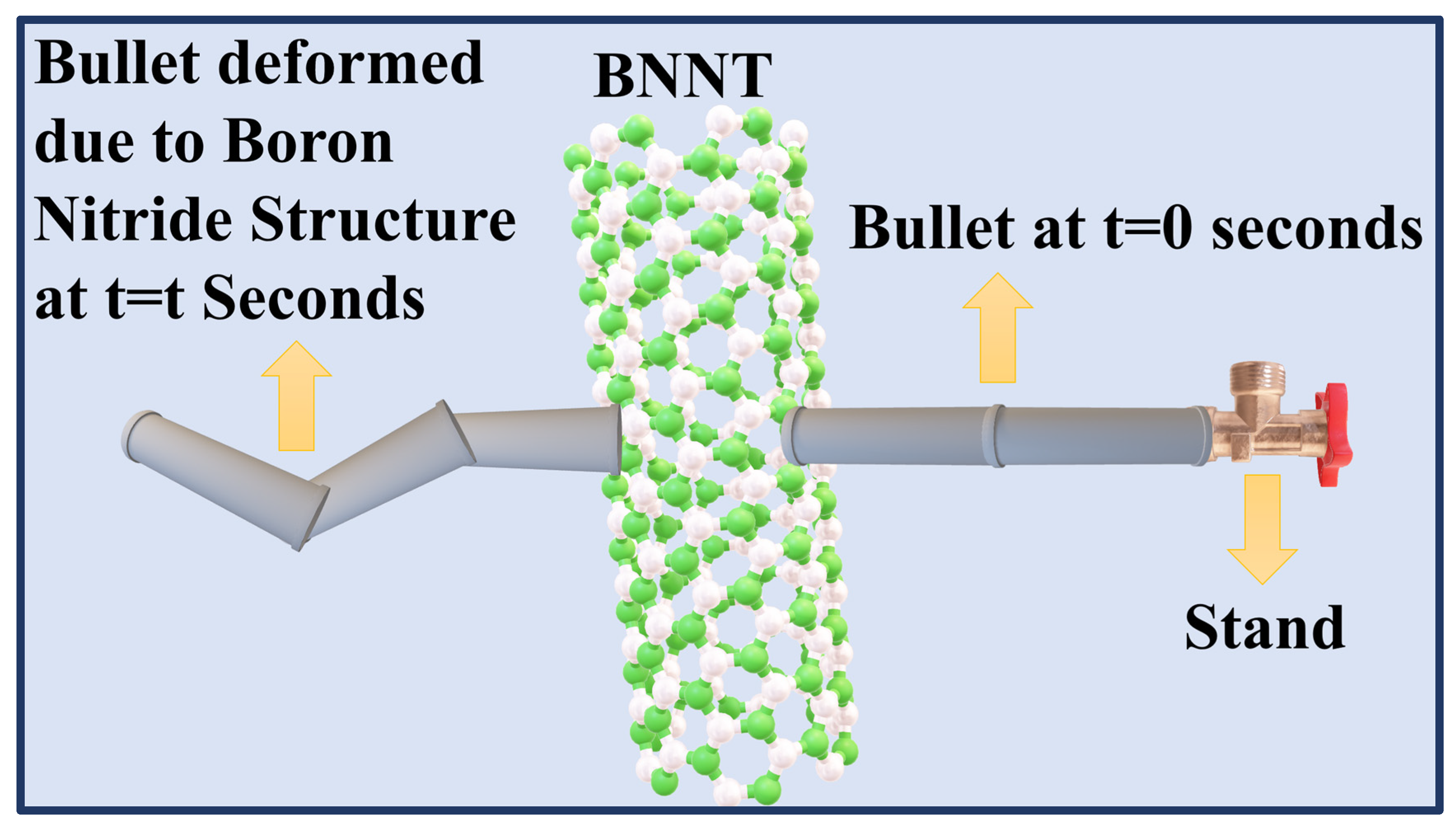

With the help of Computer Based-Simulations, the bullet was tested to see whether it showed any puncture or deformation properties when it passed through two boron nitride sheets. It was observed, as demonstrated in Figure 16 (Zochowski et al., 2023), that the boron nitride sheets excellently deformed the bullet (punctured), thus demonstrating excellent protection properties by giving a level III+ protection.

Figure 16.

Puncture Properties of Bullet due to the high mechanical strength of Boron Nitride Structures in Ballistic Applications (Zochowski et al., 2023).

Figure 16.

Puncture Properties of Bullet due to the high mechanical strength of Boron Nitride Structures in Ballistic Applications (Zochowski et al., 2023).

5.1.3. Biomedical Applications

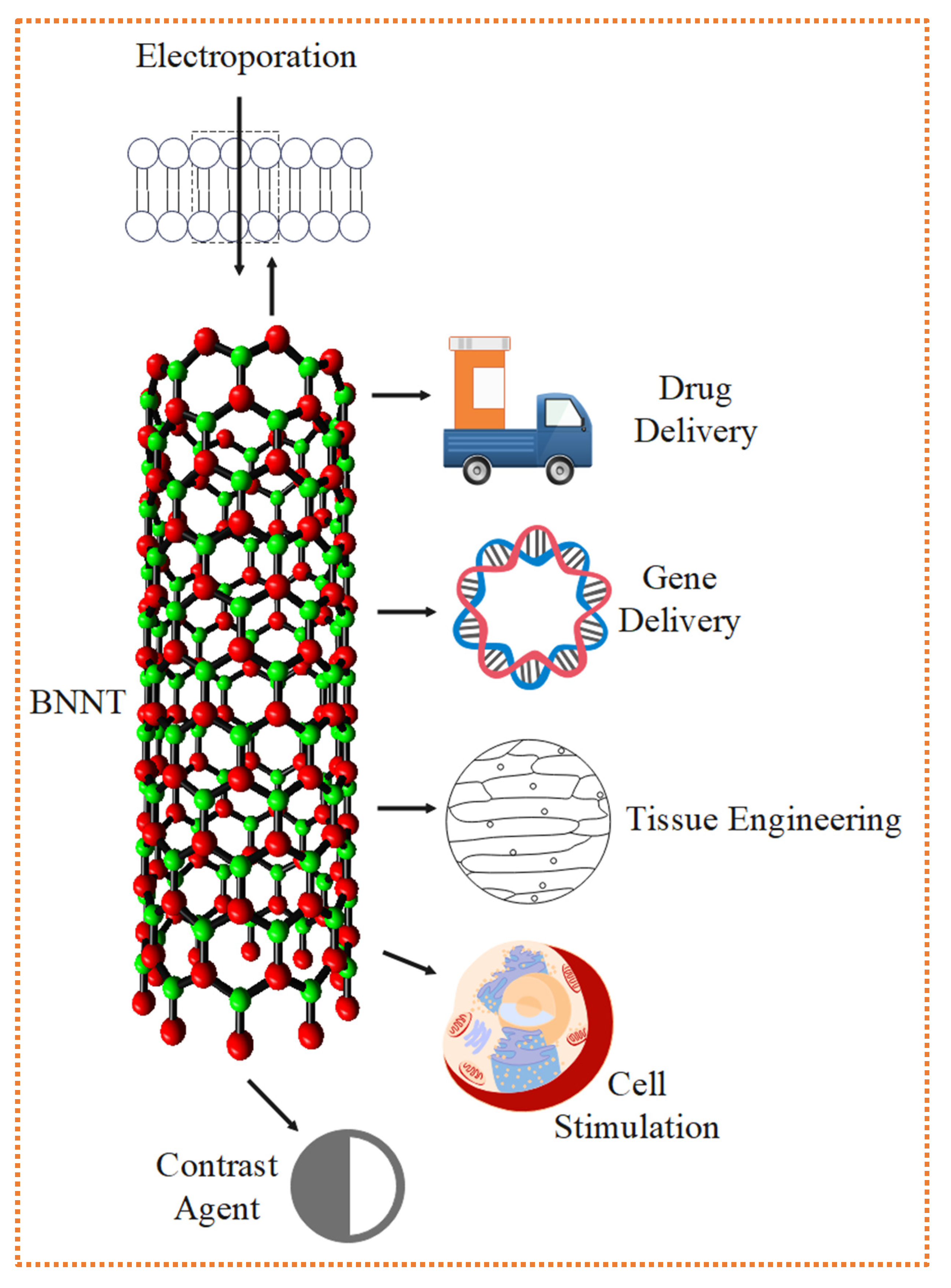

For a nanomaterial to showcase biomedical applications, which include drug delivery, gene delivery, contrast agent, electroporation, cell stimulation, and tissue engineering etc., as shown in Figure 17, a nanomaterial should have a small size, high surface-to-volume ratio combination with physical, chemical and biological properties of the nanomaterials and also the tunable functionality of the surface (Gómez-Gualdrón et al., 2011). When BNNTs are used with polymeric composites, the end product’s overall degradation rate, physical strength, and durability increase. Therefore, they can be utilised in polymeric biomaterials like BNNTs and other nanomaterials added to a polylactide-polycaprolactone (PLC) copolymer to enhance the implant’s characteristics. Once BNNTs were added, the mechanical strength increased by 1370 % (Mukhopadhyay et al., 2010). In hydroxyapatite (used in orthopaedic implant applications), a 4 % weight addition of BNNTs increased hardness by 129 %, fracture toughness of the bones by 86 %, and wear resistance of the orthopaedic bones by 75 % (Ciofani et al., 2013; Pereira et al., 2015).

Figure 17.

Various Biomedical Applications which BNNTs can showcase (Doğan et al., 2023; Gómez-Gualdrón et al., 2011).

Figure 17.

Various Biomedical Applications which BNNTs can showcase (Doğan et al., 2023; Gómez-Gualdrón et al., 2011).

For showcasing such biomedical applications, cytocompatibility of novel nanomaterials is usually the first step that must be fulfilled. The biocompatibility studies of BNNTs usually relate to the dispersion and functionalisation of BNNTs in aqueous solution. The cytotoxicity of BNNTs depends on their purity, concentration, functionalisation, size, structure and cell types. One of the main reasons BNNTs is still unable to showcase their potential for biomedical applications is due to the inconsistent sample quality taken in biomedical research and the purity of the samples. Though with a small diameter and high-quality BNNT, which could be produced from the substitution reaction method and laser ablation method will be most suitable for such applications.

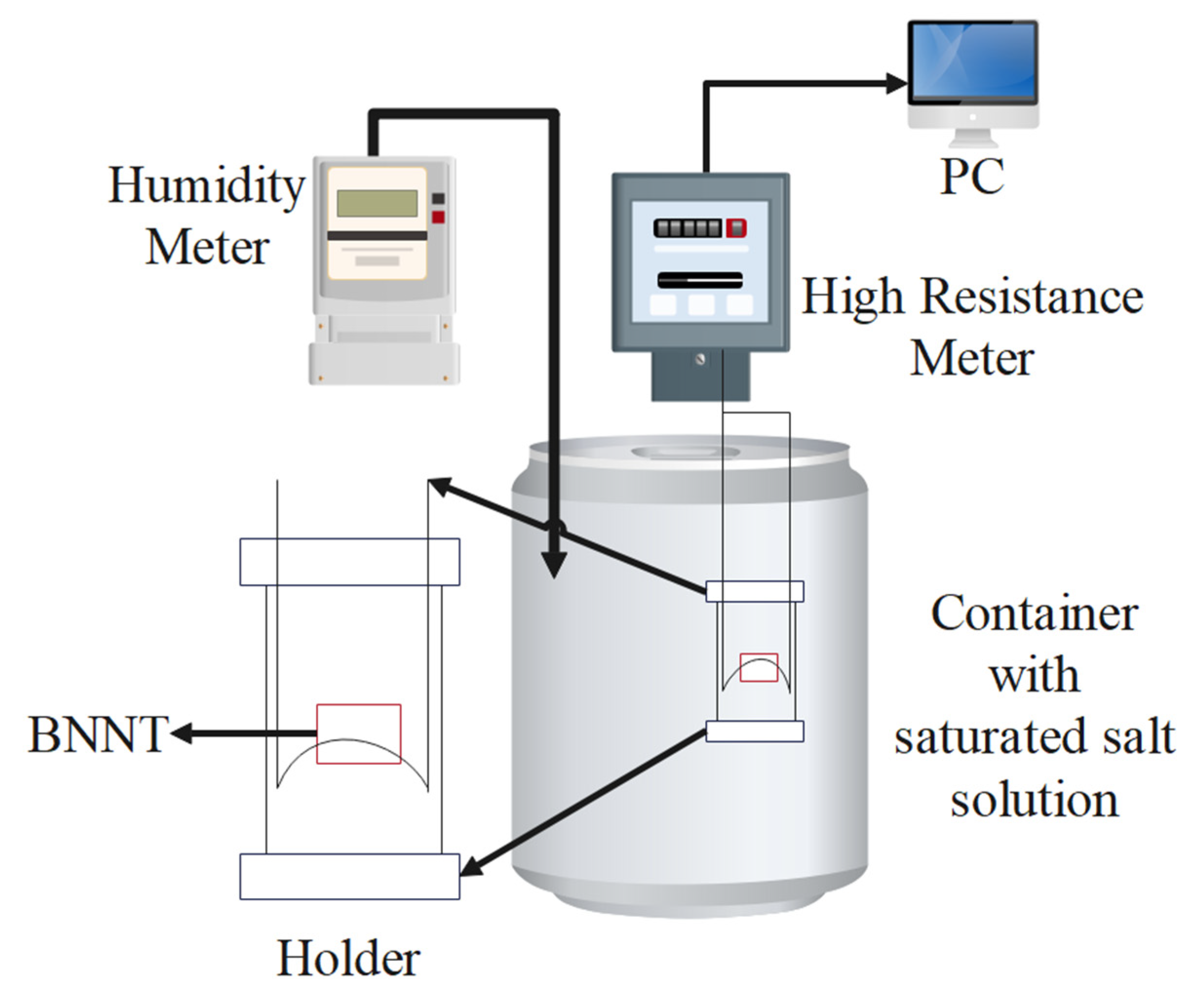

5.1.4. Sensing Applications

Regarding potential BNNTs applications based on sensors, there has not been much research and reports on this. BNNTs can also be coupled with other nanomaterials to create new sensor devices. It can build diagnostic and carbon dioxide detection devices and humidity sensors. Due to their time-resolved photoluminescence spectroscopy (TRPL) capabilities, Ni-encapsulated BNNTs can be employed for clinical diagnostics and bioimaging (Huimin Ding et al., 2020; Song et al., 2015; B. Wang et al., 2015). An integrated humidity sensing system with the help of BNNT has been showcased in Figure 18 (Hitch & Dipple, 2012; Huimin Ding et al., 2020; Strawser et al., 2014; XU et al., 2005; Yan et al., 2015).

Figure 18.

Humidity sensing application with the help of BNNT (Huimin Ding et al., 2020).

Figure 18.

Humidity sensing application with the help of BNNT (Huimin Ding et al., 2020).

5.1.5. Hydrogen Storage

Several computational and theoretical studies discovered that the B-N bond length is longer than the C-C bond length of CNTs. As a result, hydrogen molecules penetrate BNNTs more quickly than CNTs (Jhi & Kwon, 2004). The triple-walled (TW) BNNTs provided crucial restricted regions for hydrogen atoms between the tube walls. The double-walled (DW) BNNTs were expected to hold more. The DWBNNTs had a higher internal volume than the TWBNNTs because their inner tube diameter was sufficiently larger (Dethan & Swamy, 2022). The main hydrogen storage capacity is influenced by the electrical configuration of the boron and nitrogen atoms and by the thickness and size of the BNNT walls (Mpourmpakis & Froudakis, 2007).

The B-N nanotube structure formation has much space between the bonds due to a more significant bond length than CNT, which helps in better hydrogen storage, as shown in Figure 19. Such a hydrogen facility is yet to be done in a pilot project, but it is a promising proposal for an excellent hydrogen facility and circularity (Faye et al., 2022; D. Gao et al., 2014; Mittal et al., 2024; Mittal & Kushwaha, 2024b; Mpourmpakis & Froudakis, 2007; Tarkowski & Tarkowski, 2019; Yanxing et al., 2019; Y. Zhang et al., 2008a, 2008b).

Figure 19.

Hydrogen Storage Facility with Boron Nitride Nanotube Coating (Faye et al., 2022; D. Gao et al., 2014; Mittal et al., 2024; Mittal & Kushwaha, 2024b; Mpourmpakis & Froudakis, 2007; Tarkowski & Tarkowski, 2019; Yanxing et al., 2019; Y. Zhang et al., 2008a, 2008b).

Figure 19.

Hydrogen Storage Facility with Boron Nitride Nanotube Coating (Faye et al., 2022; D. Gao et al., 2014; Mittal et al., 2024; Mittal & Kushwaha, 2024b; Mpourmpakis & Froudakis, 2007; Tarkowski & Tarkowski, 2019; Yanxing et al., 2019; Y. Zhang et al., 2008a, 2008b).

5.2. Boron Nitride Carbon Nanotubes (BN-CNTs)

These BN-CNT composites’ density and specific surface area can be modified by varying the proportion of CNTs in the composites (Lonkar et al., 2012; Singh & Kushwaha, 2013a, 2013b; Singh R.P & Kushwaha O.S, 2013; Zhan et al., 2020). Due to their excellent insulating qualities, unique luminescence materials, photodetector, and reusable substrates for surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy, hexagonal boron nitride (h-BN) based materials exhibit high resistance to oxidation. These protective materials can be used in harsh environments like ballistic ones. The main drawbacks of h-BN materials are their high cost, inability to scale up production, and functional simplicity. To address these issues, techniques like in-situ functionalisation are employed (Weng et al., 2016). The appropriate mixtures of h-BN nanoparticles and C-based materials improve carbon-based composite materials’ total microwave absorption capabilities. H-BN/carbon composites with many pores have lower densities and better micro-absorption capabilities. If pure CNTs are used rather than h-BN/CNTs materials, it will cause a mismatch in impedance due to their high dielectric properties. BN-CNT composites are usually thin and lightweight, with solid and broad absorption bands. The various applications of Boron Nitride Carbon Nanotubes include Drug Delivery systems, hydrogen storage, Neutron Capture therapy, Ballistic applications, etc (Mittal & Kushwaha, 2024a; Vatanpour et al., 2021). Still, mostly a wide array of research is left in this field, and BN-CNTs hold a lot of future perspectives due to their vast applicability in different fields, which somehow considerably supports the circular economy model from the beginning of the industrial scale production.

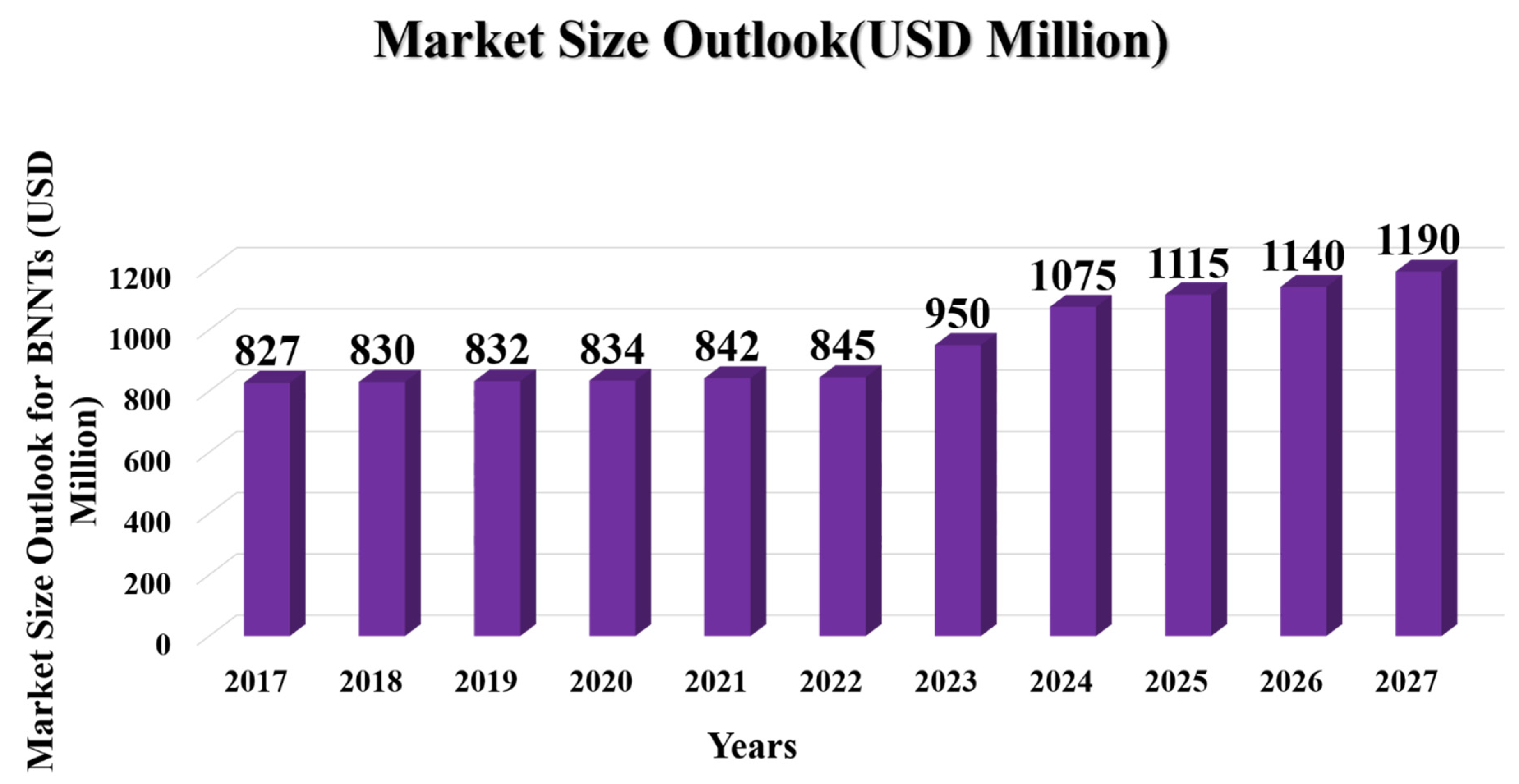

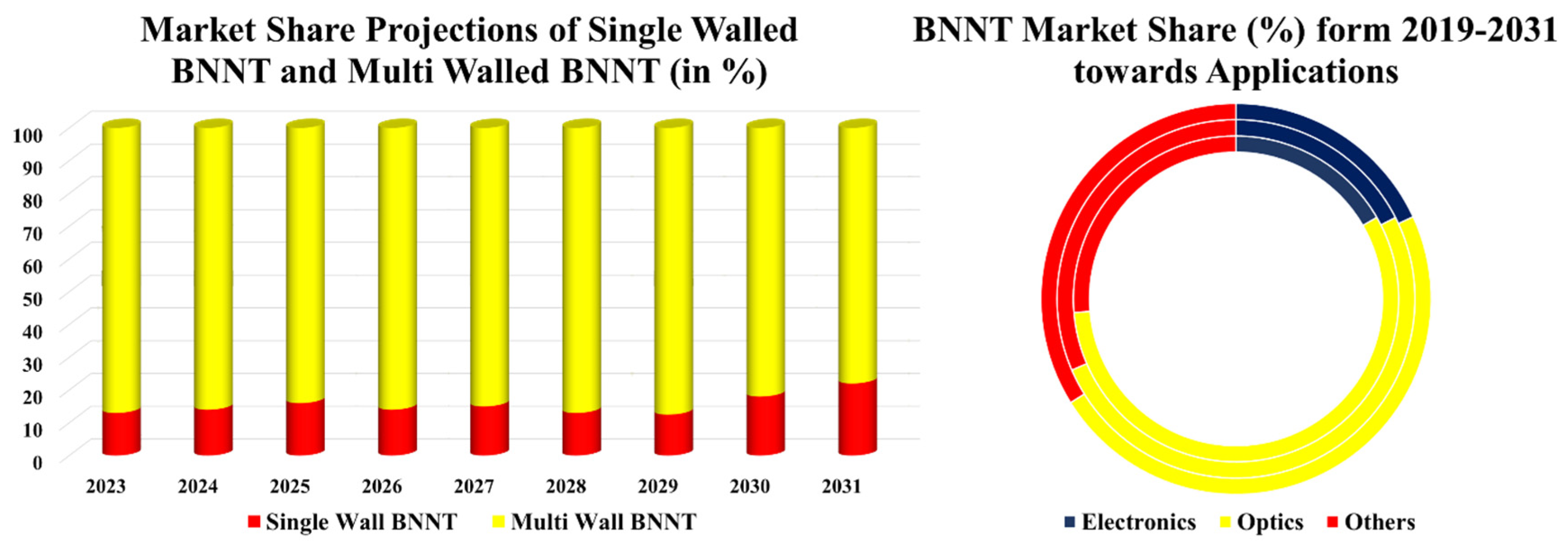

6. Cost Analysis of BNNTs and CNTs

The cost comparison of BNNTs and CNTs revealed that BNNTs are 11000 % more expensive than CNTs. To date, one of the primary causes for the paucity of BNNT research is the high cost of BNNT synthesis. Although BNNTs replace CNTs with more accessible synthetic techniques. Figure 20 discusses the overall market size output of BNNTs; it was found that the annual CAGR from 2023 to 2027 will be 6.35% which will roughly make an addition of 345 million USD from the 2022 market size. The lower market value and high price band of BNNTs generate a perfect example of recycling and a circular economy model for high-end purposes and cost-cutting required for BNNTs, as showcased in Figure 21 (Ajanovic et al., 2022; Blanco, 2009; Jakubinek et al., 2022; M. Kim et al., 2020; Naims, 2016).

Figure 20.

Graphical Analysis of market size output for BNNTs (Jakubinek et al., 2022; M. Kim et al., 2020).

Figure 20.

Graphical Analysis of market size output for BNNTs (Jakubinek et al., 2022; M. Kim et al., 2020).

Figure 21.

Graphical Analysis of Market Value (in %) of BNNT on the basis of applications and multi- & single- walled BNNT (A. Ali et al., 2023; Li et al., 2009; Patel & Miotello, 2015; Raihan, 2023; Rubio et al., 1994; Tavoni et al., 2015; J. Wang et al., 2010; Zhuang et al., 2023).

Figure 21.

Graphical Analysis of Market Value (in %) of BNNT on the basis of applications and multi- & single- walled BNNT (A. Ali et al., 2023; Li et al., 2009; Patel & Miotello, 2015; Raihan, 2023; Rubio et al., 1994; Tavoni et al., 2015; J. Wang et al., 2010; Zhuang et al., 2023).

7. Conclusions

BNNTs have a lot of unique properties, like great mechanical strength with electrically insulating behaviour, excellent oxidation resistance, neutron shielding capability, and piezoelectric properties. Still, the major con they have is their lower yields than CNTs. Much research found that Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) and Substitution Reaction can increase the overall yield of BNNTs. There is no doubt that BNNTs hold unique and better properties than CNTs. However, there is a wide gap in research regarding BNNTs and BN-CNTs, in many applications like orthopaedical implant applications, Ni-encapsulated BNNTs, polymeric composites, ceramics, etc. BNNTs have already replaced CNTs and other composites, whereas, in Ballistic applications, their practical applications are still left. BN-CNTs, on the other hand, have more exploration and research left than BNNTs. With the proper scale-up of BNNTs as showcased above, there is a considerable possibility of 200 TPY (tonnes per year) production of BNNTs at a very affordable cost with an excellent revenue for the plant as well as colossal employment and electricity requirement produced from the BNNT plant. Such scale-up opens many opportunities in producing the applications stated in ease and increasing the quality and quantifying these composites, significantly promoting the circular economy model. Boron Nitride Nanotubes exhibit robust absorption, are slender, light, and have wide absorption bands. They have been proposed for use in armour and the simple manufacture of Hildewintera-colademononis-like hexagonal boron nitride/carbon nanotube composites, but their practical uses are relatively limited. BNNTs have exceptional thermal and mechanical properties, and high-end applications can be easily upgraded, recycled and reused as per the requirement, except for biomedical applications.

8. Future Perspectives

Some of the Future perspectives are

1)Theoretical research of the hydrogen storage properties of the BNNTs showed that the hydrogen storage properties of the BNNTs depend on the electronic structure of the boron and nitrogen atoms, the diameter and the dimensions of the BNNT walls. Investigations suggest that BNNTs may be helpful to materials for hydrogen storage, even without data. It is important to stress the necessity for additional experimental research focusing on elements like temperature, gas pressure, and BNNT purity.

2) BN-CNTs experimental research on many of their properties, like mechanical strength, electrical properties, thermal conductivity, etc., should be done, as they have a lot of potential applications like protective shields, nanomaterials, and various composites. These unique properties of this material make it a prominent candidate for reuse and upcycling for sustainable development.

3) It is still impossible to create a large amount of BNNTs with the accuracy and uniformity shown by CNTS, but further experimentation on the synthesis of BNNTs can improve the same.

4) Industrial Scale-up of BNNTs and BNCNTs: With the proposed industrial plan in the study, the future holds a lot of research and funding in commercialising these composites. With such proposals, many complexions come along with them that researchers and industrialists have to overcome and work towards.

5) Due to the lack of industrial scale up in BNNT, there has been exigent and very limited reports on the economic aspects of BNNT which are very significant to alternate the applications of CNT materials towards BNNT.

References

- Adeel, M., Rahman, Md. M., & Lee, J.-J. (2019). Label-free aptasensor for the detection of cardiac biomarker myoglobin based on gold nanoparticles decorated boron nitride nanosheets. Biosensors and Bioelectronics, 126, 143–150. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R., Nieto, A., Chen, H., Mora, M., & Agarwal, A. (2013). Nanoscale Damping Characteristics of Boron Nitride Nanotubes and Carbon Nanotubes Reinforced Polymer Composites. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 5(22), 12052–12057. [CrossRef]

- Aharonian, C., Tessier-Doyen, N., Geffroy, P.-M., & Pagnoux, C. (2021). Elaboration and mechanical properties of monolithic and multilayer mullite-alumina based composites devoted to ballistic applications. Ceramics International, 47(3), 3826–3832. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, P., Khandaker, M. U., Khan, Z. R., & Amin, Y. M. (2015). Synthesis of boron nitride nanotubes via chemical vapour deposition: a comprehensive review. RSC Advances, 5(44), 35116–35137. [CrossRef]

- Aiyer, S., Prasad, R., Kumar, M., Nirvikar, K., Jain, B., & Kushwaha, O. S. (2016). Fluorescent carbon nanodots for targeted in vitro cancer cell imaging. Applied Materials Today, 4, 71–77. [CrossRef]

- Aiyer, S., Prasad, R., Kumar, M., Nirvikar, K., Jain, B., & Kushwaha, O. S. (2019). Corrigendum to “Fluorescent carbon nanodots for targeted in vitro cancer cell imaging” [Appl. Mater. Today 4 (2016) 71–77]. Applied Materials Today, 17, 236–240. [CrossRef]

- Ajanovic, A., Sayer, M., & Haas, R. (2022). The economics and the environmental benignity of different colors of hydrogen. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. [CrossRef]

- Ali, A., Radulescu, M., & Balsalobre-Lorente, D. (2023). A dynamic relationship between renewable energy consumption, nonrenewable energy consumption, economic growth, and carbon dioxide emissions: Evidence from Asian emerging economies. Energy & Environment, 0958305X2311516. [CrossRef]

- Ali, N. A., Ahmad, M. A. N., Yahya, M. S., Sazelee, N., & Ismail, M. (2022). Improved Dehydrogenation Properties of LiAlH4 by Addition of Nanosized CoTiO3. Nanomaterials, 12(21), 3921. [CrossRef]

- An, L., Yu, Y., Cai, Q., Mateti, S., Li, L. H., & Chen, Y. I. (2023). Hexagonal boron nitride nanosheets: Preparation, heat transport property and application as thermally conductive fillers. Progress in Materials Science, 138, 101154. [CrossRef]

- Andreasen, A., Vegge, T., & Pedersen, A. S. (2005). Dehydrogenation kinetics of as-received and ball-milled. Journal of Solid State Chemistry, 178(12), 3672–3678. [CrossRef]

- Arenal, R., Stephan, O., Cochon, J.-L., & Loiseau, A. (2007). Root-Growth Mechanism for Single-Walled Boron Nitride Nanotubes in Laser Vaporization Technique. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 129(51), 16183–16189. [CrossRef]

- Asyraf, M. Z., Suriani, M. J., Ruzaidi, C. M., Khalina, A., Ilyas, R. A., Asyraf, M. R. M., Syamsir, A., Azmi, A., & Mohamed, A. (2022). Development of Natural Fibre-Reinforced Polymer Composites Ballistic Helmet Using Concurrent Engineering Approach: A Brief Review. Sustainability, 14(12), 7092. [CrossRef]

- Bhat, A., Naveen, J., Jawaid, M., Norrrahim, M. N. F., Rashedi, A., & Khan, A. (2021). Advancement in fiber reinforced polymer, metal alloys and multi-layered armour systems for ballistic applications – A review. Journal of Materials Research and Technology, 15, 1300–1317. [CrossRef]

- Bilisik, K., & Syduzzaman, M. (2022). Protective textiles in defence and ballistic protective clothing. In Protective Textiles from Natural Resources (pp. 689–749). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Blanco, M. I. (2009). The economics of wind energy. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 13(6–7), 1372–1382. [CrossRef]

- Byrne, M. T., & Gun’ko, Y. K. (2010). Recent Advances in Research on Carbon Nanotube-Polymer Composites. Advanced Materials, 22(15), 1672–1688. [CrossRef]

- Cau, M., Dorval, N., Attal-Trétout, B., Cochon, J. L., Cao, B., Bresson, L., Jaffrennou, P., Silly, M., Loiseau, A., & Obraztsova, E. D. (2008). Laser-Based Diagnostics Applied to the Study of BN Nanotubes Synthesis. Journal of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology, 8(11), 6129–6140. [CrossRef]

- Cavallaro P.V. (2011). Soft Body Armor: An Overview of Materials, Manufacturing, Testing, and Ballistic Impact Dynamics. Defense Technical Information Center.

- Chang, C. W., Fennimore, A. M., Afanasiev, A., Okawa, D., Ikuno, T., Garcia, H., Li, D., Majumdar, A., & Zettl, A. (2006). Isotope Effect on the Thermal Conductivity of Boron Nitride Nanotubes. Physical Review Letters, 97(8), 085901. [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-P., Shih, C.-H., You, J.-L., Youh, M.-J., Liu, Y.-M., & Ger, M.-D. (2021). Preparation and Ballistic Performance of a Multi-Layer Armor System Composed of Kevlar/Polyurea Composites and Shear Thickening Fluid (STF)-Filled Paper Honeycomb Panels. Polymers, 13(18), 3080. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Fitz Gerald, J., Williams, J. S., & Bulcock, S. (1999). Synthesis of boron nitride nanotubes at low temperatures using reactive ball milling. Chemical Physics Letters, 299(3–4), 260–264. [CrossRef]

- Ciofani, G., Danti, S., Genchi, G. G., Mazzolai, B., & Mattoli, V. (2013). Boron Nitride Nanotubes: Biocompatibility and Potential Spill-Over in Nanomedicine. Small, 9(9–10), 1672–1685. [CrossRef]

- Davis, D. M. (2012). Finite Element Modeling of Ballistic Impact on a Glass Fiber Composite Armor [California Polytechnic State University]. [CrossRef]

- Deshwal, D., & Narwal, A. K. (2023). Analysis of surface deviation impact on bio-mass sensing application of Boron Nitride Nanotubes. Results in Engineering, 19, 101282. [CrossRef]

- Dethan, J. F. N., & Swamy, V. (2022). Mechanical and thermal properties of carbon nanotubes and boron nitride nanotubes for fuel cells and hydrogen storage applications: A comparative review of molecular dynamics studies. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 47(59), 24916–24944. [CrossRef]

- Doğan, D., Karaduman, F. R., Horzum, N., & Metin, A. Ü. (2023). Boron nitride decorated poly(vinyl alcohol)/poly(acrylic acid) composite nanofibers: A promising material for biomedical applications. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials, 141, 105773. [CrossRef]

- Dresch, A. B., Venturini, J., Arcaro, S., Montedo, O. R. K., & Bergmann, C. P. (2021). Ballistic ceramics and analysis of their mechanical properties for armour applications: A review. Ceramics International, 47(7), 8743–8761. [CrossRef]

- Dumitrică, T., Hua, M., & Yakobson, B. I. (2004). Endohedral silicon nanotubes as thinnest silicide wires. Physical Review B, 70(24), 241303. [CrossRef]

- Ellis. L R. (1996). Ballistic impact resistance of graphite epoxy composites with shape memory alloy and extended chain polyethylene spectratm hybrid components. Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

- Faye, O., Szpunar, J., & Eduok, U. (2022). A critical review on the current technologies for the generation, storage, and transportation of hydrogen. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. [CrossRef]

- Fayed, A. I. H., Abo El Amaim, Y. A., & Elgohary, D. H. (2021). Enhancing the performance of cordura and ballistic nylon using polyurethane treatment for outer shell of bulletproof vest. Journal of King Saud University - Engineering Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Gao, C., Feng, P., Peng, S., & Shuai, C. (2017). Carbon nanotube, graphene and boron nitride nanotube reinforced bioactive ceramics for bone repair. Acta Biomaterialia, 61, 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Gao, D., Jiang, D., Liu, P., Li, Z., Hu, S., & Xu, H. (2014). An integrated energy storage system based on hydrogen storage: Process configuration and case studies with wind power. Energy. [CrossRef]

- Genchi, G. G., & Ciofani, G. (2015). Bioapplications of boron nitride nanotubes. Nanomedicine, 10(22), 3315–3319. [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, D., Bando, Y., Eremets, M., Takemura, K., Kurashima, K., Tamiya, K., & Yusa, H. (1997). Boron nitride nanotube growth defects and their annealing-out under electron irradiation. Chemical Physics Letters, 279(3–4), 191–196. [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, R. D., Knights, A. P., Simpson, P. J., & Coleman, P. G. (1999). Assessment of the normalization procedure used for interlaboratory comparisons of positron beam measurements. Journal of Applied Physics, 86(1), 342–345. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Gualdrón, D. A., Gómez-Gualdrón, D. A., Burgos, J. C., Burgos, J. C., Yu, J., Yu, J., Balbuena, P. B., & Balbuena, P. B. (2011). Carbon Nanotubes: Engineering Biomedical Applications. Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science. [CrossRef]

- Hayat, A., Sohail, M., Hamdy, M. S., Taha, T. A., AlSalem, H. S., Alenad, A. M., Amin, M. A., Shah, R., Palamanit, A., Khan, J., Nawawi, W. I., & Mane, S. K. B. (2022). Fabrication, characteristics, and applications of boron nitride and their composite nanomaterials. Surfaces and Interfaces, 29, 101725. [CrossRef]

- Hitch, M., & Dipple, G. M. (2012). Economic feasibility and sensitivity analysis of integrating industrial-scale mineral carbonation into mining operations. Minerals Engineering. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z., Chen, Z., Chen, Z., Lv, C., Meng, H., & Zhang, C. (2014). Ni12P5 nanoparticles as an efficient catalyst for hydrogen generation via electrolysis and photoelectrolysis. ACS Nano, 8(8), 8121–8129. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.-C., Zhang, Y.-K., Lin, Y.-C., & Jiang, Y.-Q. (2022). Physical property and failure mechanism of self-piercing riveting joints between foam metal sandwich composite aluminum plate and aluminum alloy. Journal of Materials Research and Technology, 17, 139–149. [CrossRef]

- Huimin Ding, Jingwen Guan, Ping Lu, Stephen J. Mihailov, Christopher T. Kingston, & Benoit Simard. (2020). Boron Nitride Nanotubes for Optical Fiber Sensor Applications. Optical Fiber Sensors Conference 2020 Special Edition.

- Jakubinek, M. B., Kim, K. S., Kim, M. J., Martí, A. A., & Pasquali, M. (2022). Recent advances and perspective on boron nitride nanotubes: From synthesis to applications. Journal of Materials Research, 37(24), 4403–4418. [CrossRef]

- Jhi, S.-H., & Kwon, Y.-K. (2004). Hydrogen adsorption on boron nitride nanotubes: A path to room-temperature hydrogen storage. Physical Review B, 69(24), 245407. [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y. H., Ryu, J. H., Kim, C. H., Lee, W. K., Tran, T. V. T., Lee, H. L., Zhang, R. H., & Ahn, D. H. (2012). Enhancing hydrogen production efficiency in microbial electrolysis cell with membrane electrode assembly cathode. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry, 18(2), 715–719. [CrossRef]

- Kalay, S., Yilmaz, Z., Sen, O., Emanet, M., Kazanc, E., & Çulha, M. (2015a). Synthesis of boron nitride nanotubes and their applications. Beilstein Journal of Nanotechnology, 6, 84–102. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. J., Kim, H. Y., Joo, J., Joo, S. H., Lim, J. S., Lee, J., Huang, H., Shao, M., Hu, J., Kim, J. Y., Min, B. J., Lee, S. W., Kang, M., Lee, K., Choi, S., Park, Y., Wang, Y., Li, J., Zhang, Z., … Choi, S.-I. (2022). Recent advances in non-precious group metal-based catalysts for water electrolysis and beyond. Journal of Materials Chemistry A, 10(1), 50–88. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. H., Pham, T. V., Hwang, J. H., Kim, C. S., & Kim, M. J. (2018). Boron nitride nanotubes: synthesis and applications. Nano Convergence, 5(1), 17. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., Lee, S., Uhm, Y. R., Jun, J., Rhee, C. K., & Kim, G. M. (2011). Synthesis and growth of boron nitride nanotubes by a ball milling–annealing process. Acta Materialia, 59(7), 2807–2813. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-Y., Jang, D., & Greer, J. R. (2010). Tensile and compressive behavior of tungsten, molybdenum, tantalum and niobium at the nanoscale. Acta Materialia, 58(7), 2355–2363. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M., Lee, Y. H., Oh, J.-H., Hong, S.-H., Min, B.-I., Kim, T.-H., & Choi, S. (2020). Synthesis of boron nitride nanotubes using triple DC thermal plasma reactor with hydrogen injection. Chemical Engineering Journal, 395, 125148. [CrossRef]

- Ko, J., Kim, D., Sim, G., Moon, S. Y., Lee, S. S., Jang, S. G., Ahn, S., Im, S. G., & Joo, Y. (2023). Scalable, Highly Pure, and Diameter-Sorted Boron Nitride Nanotube by Aqueous Polymer Two-Phase Extraction. Small Methods, 7(4). [CrossRef]

- Kong, X., Chen, Y., Yang, R., Wang, Y., Zhang, Z., Li, M., Chen, H., Li, L., Gong, P., Zhang, J., Xu, K., Cao, Y., Cai, T., Yan, Q., Dai, W., Wu, X., Lin, C.-T., Nishimura, K., Pan, Z., … Yu, J. (2024). Large-scale production of boron nitride nanosheets for flexible thermal interface materials with highly thermally conductive and low dielectric constant. Composites Part B: Engineering, 271, 111164. [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, O. S., Avadhani, C. V., & Singh, R. P. (2015a). Preparation and characterization of self-photostabilizing UV-durable bionanocomposite membranes for outdoor applications. Carbohydrate Polymers, 123, 164–173. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. H., Wang, J., Kayatsha, V. K., Huang, J. Y., & Yap, Y. K. (2008). Effective growth of boron nitride nanotubes by thermal chemical vapor deposition. Nanotechnology, 19(45), 455605. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., Kong, K. Y., Jung, C. R., Cho, E., Yoon, S. P., Han, J., Lee, T.-G., & Nam, S. W. (2007). A structured Co–B catalyst for hydrogen extraction from NaBH4 solution. Catalysis Today, 120(3–4), 305–310. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. H., Kim, M. J., Ahn, S., & Koh, B. (2020). Purification of boron nitride nanotubes enhances biological application properties. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(4). [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. S., Wetzel, E. D., & Wagner, N. J. (2003). The ballistic impact characteristics of Kevlar® woven fabrics impregnated with a colloidal shear thickening fluid. Journal of Materials Science, 38(13), 2825–2833. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Zhou, J., Zhao, K., Tung, S., & Schneider, E. (2009). Synthesis of boron nitride nanotubes from boron oxide by ball milling and annealing process. Materials Letters, 63(20), 1733–1736. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Zhou, Z., & Zhao, J. (2008). Functionalization of BN nanotubes with dichlorocarbenes. Nanotechnology, 19(1), 015202. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.-S., Li, Z.-B., Jiao, C.-L., Si, X.-L., Yang, L.-N., Zhang, J., Zhou, H.-Y., Huang, F.-L., Gabelica, Z., Schick, C., Sun, L.-X., & Xu, F. (2013). Improved reversible hydrogen storage of LiAlH4 by nano-sized TiH2. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 38(6), 2770–2777. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.-S., Sun, L.-X., Zhang, Y., Xu, F., Zhang, J., Chu, H.-L., Fan, M.-Q., Zhang, T., Song, X.-Y., & Grolier, J. P. (2009). Effect of ball milling time on the hydrogen storage properties of TiF3-doped LiAlH4. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 34(19), 8079–8085. [CrossRef]

- Loiseau, A., Willaime, F., Demoncy, N., Hug, G., & Pascard, H. (1996). Boron Nitride Nanotubes with Reduced Numbers of Layers Synthesized by Arc Discharge. Physical Review Letters, 76(25), 4737–4740. [CrossRef]

- Lonkar, S. P., Kushwaha, O. S., Leuteritz, A., Heinrich, G., & Singh, R. P. (2012). Self photostabilizing UV-durable MWCNT/polymer nanocomposites. RSC Advances, 2(32), 12255. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y., Zhao, R., Wang, L., & E, S. (2023). Boron nitride nanotubes and nanosheets: Their basic properties, synthesis, and some of applications. Diamond and Related Materials, 136, 109978. [CrossRef]

- Luz, F. S. da, Lima Junior, E. P., Louro, L. H. L., & Monteiro, S. N. (2015). Ballistic Test of Multilayered Armor with Intermediate Epoxy Composite Reinforced with Jute Fabric. Materials Research, 18(suppl 2), 170–177. [CrossRef]

- Luz, F. S. da, Monteiro, S. N., Lima, E. S., & Lima Júnior, É. P. (2017). Ballistic Application of Coir Fiber Reinforced Epoxy Composite in Multilayered Armor. Materials Research, 20(suppl 2), 23–28. [CrossRef]

- Lynch, I., & Dawson, K. A. (2008). Protein-nanoparticle interactions. Nano Today, 3(1–2), 40–47. [CrossRef]

- Ma, R., Bando, Y., & Sato, T. (2001). CVD synthesis of boron nitride nanotubes without metal catalysts. Chemical Physics Letters, 337(1–3), 61–64. [CrossRef]

- Maestre, C., Toury, B., Steyer, P., Garnier, V., & Journet, C. (2021). Hexagonal boron nitride: a review on selfstanding crystals synthesis towards 2D nanosheets. Journal of Physics: Materials, 4(4), 044018. [CrossRef]

- Maselugbo, A. O., Harrison, H. B., & Alston, J. R. (2022). Boron nitride nanotubes: A review of recent progress on purification methods and techniques. Journal of Materials Research, 37(24), 4438–4458. [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, T., Nakae, H., & Irai, T. (1988). Density and deposition rate of chemical-vapour-deposited boron nitride. Journal of Materials Science, 23(2), 509–514. [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, T., Uno, N., Nakae, H., & Hirai, T. (1986). Synthesis and structure of chemically vapour-deposited boron nitride. Journal of Materials Science, 21(2), 649–658. [CrossRef]

- Medvedovski, E. (2010). Ballistic performance of armour ceramics: Influence of design and structure. Part 1. Ceramics International, 36(7), 2103–2115. [CrossRef]

- Meethom, S., Kaewsuwan, D., Chanlek, N., Utke, O., & Utke, R. (2020). Enhanced hydrogen sorption of LiBH4–LiAlH4 by quenching dehydrogenation, ball milling, and doping with MWCNTs. Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids, 136, 109202. [CrossRef]

- Meng, W., Huang, Y., Fu, Y., Wang, Z., & Zhi, C. (2014). Polymer composites of boron nitride nanotubes and nanosheets. J. Mater. Chem. C, 2(47), 10049–10061. [CrossRef]

- Merlo, A., Mokkapati, V. R. S. S., Pandit, S., & Mijakovic, I. (2018). Boron nitride nanomaterials: biocompatibility and bio-applications. Biomaterials Science, 6(9), 2298–2311. [CrossRef]

- Millinger, M., Ponitka, J., Arendt, O., & Thrän, D. (2017). Competitiveness of advanced and conventional biofuels: Results from least-cost modelling of biofuel competition in Germany. Energy Policy, 107, 394–402. [CrossRef]

- Mittal, H., & Kushwaha, O. S. (2024a). Machine Learning in Commercialized Coatings. In Functional Coatings (pp. 450–474). Wiley. [CrossRef]

- Mittal, H., & Kushwaha, O. S. (2024b). Policy Implementation Roadmap, Diverse Perspectives, Challenges, Solutions Towards Low-Carbon Hydrogen Economy. Green and Low-Carbon Economy. [CrossRef]

- Mittal, H., Verma, S., Bansal, A., & Singh Kushwaha, O. (2024). Low-Carbon Hydrogen Economy Perspective and Net Zero-Energy Transition through Proton Exchange Membrane Electrolysis Cells (PEMECs), Anion Exchange Membranes (AEMs) and Wind for Green Hydrogen Generation. Qeios. [CrossRef]

- Mpourmpakis, G., & Froudakis, G. E. (2007). Why boron nitride nanotubes are preferable to carbon nanotubes for hydrogen storage?An ab initio theoretical study. Catalysis Today, 120(3–4), 341–345. [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, S., Gowtham, S., Scheicher, R. H., Pandey, R., & Karna, S. P. (2010). Theoretical study of physisorption of nucleobases on boron nitride nanotubes: a new class of hybrid nano-biomaterials. Nanotechnology, 21(16), 165703. [CrossRef]

- Mylvaganam, K., & Zhang, L. C. (2007). Ballistic resistance capacity of carbon nanotubes. Nanotechnology, 18(47), 475701. [CrossRef]

- Naclerio, A. E., & Kidambi, P. R. (2023). A Review of Scalable Hexagonal Boron Nitride ( h -BN) Synthesis for Present and Future Applications. Advanced Materials, 35(6). [CrossRef]

- Naims, H. (2016). Economics of carbon dioxide capture and utilization-a supply and demand perspective. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, L. F. C., Holanda, L. I. F., Louro, L. H. L., Monteiro, S. N., Gomes, A. V., & Lima, É. P. (2017). Natural Mallow Fiber-Reinforced Epoxy Composite for Ballistic Armor Against Class III-A Ammunition. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A, 48(10), 4425–4431. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.-T. N., Meek, G., Breeze, J., & Masouros, S. D. (2020). Gelatine Backing Affects the Performance of Single-Layer Ballistic-Resistant Materials Against Blast Fragments. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 8. [CrossRef]

- Nurazzi, N. M., Asyraf, M. R. M., Khalina, A., Abdullah, N., Aisyah, H. A., Rafiqah, S. A., Sabaruddin, F. A., Kamarudin, S. H., Norrrahim, M. N. F., Ilyas, R. A., & Sapuan, S. M. (2021). A Review on Natural Fiber Reinforced Polymer Composite for Bullet Proof and Ballistic Applications. Polymers, 13(4), 646. [CrossRef]

- Nyanor, P., Hamada, A. S., & Hassan, M. A.-N. (2018). Ballistic Impact Simulation of Proposed Bullet Proof Vest Made of TWIP Steel, Water and Polymer Sandwich Composite Using FE-SPH Coupled Technique. Key Engineering Materials, 786, 302–313. [CrossRef]

- Odesanya, K. O., Ahmad, R., Jawaid, M., Bingol, S., Adebayo, G. O., & Wong, Y. H. (2021). Natural Fibre-Reinforced Composite for Ballistic Applications: A Review. Journal of Polymers and the Environment, 29(12), 3795–3812. [CrossRef]

- Pakdel, A., Bando, Y., & Golberg, D. (2014). Plasma-Assisted Interface Engineering of Boron Nitride Nanostructure Films. ACS Nano. [CrossRef]

- Pan, S., Feng, J., Safaei, B., Qin, Z., Chu, F., & Hui, D. (2022). A comparative experimental study on damping properties of epoxy nanocomposite beams reinforced with carbon nanotubes and graphene nanoplatelets. Nanotechnology Reviews, 11(1), 1658–1669. [CrossRef]

- Patel, N., & Miotello, A. (2015). Progress in Co–B related catalyst for hydrogen production by hydrolysis of boron-hydrides: A review and the perspectives to substitute noble metals. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P. H. F., Rosa, M. de F., Cioffi, M. O. H., Benini, K. C. C. de C., Milanese, A. C., Voorwald, H. J. C., & Mulinari, D. R. (2015). Vegetal fibers in polymeric composites: a review. Polímeros, 25(1), 9–22. [CrossRef]

- Pumera, M. (2009). The Electrochemistry of Carbon Nanotubes: Fundamentals and Applications. Chemistry - A European Journal, 15(20), 4970–4978. [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y., Cai, Y., Huang, L., Gao, T., Jiang, H., Zhang, H., Huang, Z., & Qu, J. (2023). In Situ Exfoliated Polymer/Boron Nitride Thermal Conductors via Hybrid Geometry Induced Local Ball Milling. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, 62(3), 1438–1449. [CrossRef]

- Raihan, A. (2023). An econometric evaluation of the effects of economic growth, energy use, and agricultural value added on carbon dioxide emissions in Vietnam. Asia-Pacific Journal of Regional Science, 7(3), 665–696. [CrossRef]

- Risby, M. S., Wong, S. V., Hamouda, A. M. S., Khairul, A. R., & Elsadig, M. (2008). Ballistic Performance of Coconut Shell Powder/Twaron Fabric against Non-armour Piercing Projectiles. Defence Science Journal, 58(2), 248–263. [CrossRef]

- Rubio, A., Corkill, J. L., & Cohen, M. L. (1994). Theory of graphitic boron nitride nanotubes. Physical Review B, 49(7), 5081–5084. [CrossRef]

- Salman, S. D., & Leman, Z. B. (2018). Physical, Mechanical and Ballistic Properties of Kenaf Fiber Reinforced Poly Vinyl Butyral and Its Hybrid Composites. In Natural Fibre Reinforced Vinyl Ester and Vinyl Polymer Composites (pp. 249–263). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, M., Kim, J.-Y., & Jacobs, L. J. (2023). Machine and deep learning for coating thickness prediction using Lamb waves. Wave Motion, 120, 103137. [CrossRef]

- Shadi, M., & Hamedani, S. (2023). A DFT approach to the adsorption of the Levodopa anti-neurodegenerative drug on pristine and Al-doped boron nitride nanotubes as a drug delivery vehicle. Structural Chemistry, 34(3), 905–914. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q., Zhang, K., Lu, R., & Jiang, J. (2018). Water desalination and biofuel dehydration through a thin membrane of polymer of intrinsic microporosity: Atomistic simulation study. Journal of Membrane Science, 545, 49–56. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y., Hamsen, C., Jia, X., Kim, K. K., Reina, A., Hofmann, M., Hsu, A. L., Zhang, K., Li, H., Juang, Z.-Y., Dresselhaus, Mildred. S., Li, L.-J., & Kong, J. (2010). Synthesis of Few-Layer Hexagonal Boron Nitride Thin Film by Chemical Vapor Deposition. Nano Letters, 10(10), 4134–4139. [CrossRef]

- Silveira, P. H. P. M. da, Silva, T. T. da, Ribeiro, M. P., Rodrigues de Jesus, P. R., Credmann, P. C. R. dos S., & Gomes, A. V. (2021a). A Brief Review of Alumina, Silicon Carbide and Boron Carbide Ceramic Materials for Ballistic Applications. Academia Letters. [CrossRef]

- Singh, R. P., & Kushwaha, O. S. (2013a). International Council of Materials Education. Journal of Materials Education, 79–119.

- Singh, R. P., & Kushwaha, O. S. (2013b). Polymer Solar Cells: An Overview. Macromolecular Symposia, 327(1), 128–149. [CrossRef]

- Sliwinski, M., Kucharczyk, W., & Guminski, R. (2018). Overview of polymer laminates applicable to elements of light-weight ballistic shields of special purpose transport means. Scientific Journal of the Military University of Land Forces, 189(3), 228–243. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y., Li, B., Yang, S., Ding, G., Zhang, C., & Xie, X. (2015). Ultralight boron nitride aerogels via template-assisted chemical vapor deposition. Scientific Reports, 5(1), 10337. [CrossRef]

- Soorya Prabha, P., Ragavi, I. G., Rajesh, R., & Pradeep Kumar, M. (2021). FEA analysis of ballistic impact on carbon nanotube bulletproof vest. Materials Today: Proceedings, 46, 3937–3940. [CrossRef]

- Steinke, K. (2022). Nanomaterial-Based Surface Modifications for Improved Ballistic and Structural Performance of Ballistic Materials . Doctoral Dissertation.

- Strawser, D., Thangavelautham, J., & Dubowsky, S. (2014). A passive lithium hydride based hydrogen generator for low power fuel cells for long-duration sensor networks. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 39(19), 10216–10229. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J., Lu, C., Song, Y., Ji, Q., Song, X., Li, Q., Zhang, Y., Zhang, L., Kong, J., & Liu, Z. (2018). Recent progress in the tailored growth of two-dimensional hexagonal boron nitride via chemical vapour deposition. Chemical Society Reviews, 47(12), 4242–4257. [CrossRef]

- Suryavanshi, A. P., Yu, M.-F., Wen, J., Tang, C., & Bando, Y. (2004). Elastic modulus and resonance behavior of boron nitride nanotubes. Applied Physics Letters, 84(14), 2527–2529. [CrossRef]

- Talebi, H. (2006). Finite element modeling of ballistic penetration into fabric armor . Doctoral Dissertation, Universiti Putra Malaysia.

- Tarkowski, R., & Tarkowski, R. (2019). Underground hydrogen storage: Characteristics and prospects. Renewable & Sustainable Energy Reviews. [CrossRef]

- Tavoni, M., Kriegler, E., Riahi, K., van Vuuren, D. P., Aboumahboub, T., Bowen, A., Calvin, K., Campiglio, E., Kober, T., Jewell, J., Luderer, G., Marangoni, G., Marangoni, G., McCollum, D. L., van Sluisveld, M. A. E., Zimmer, A., & van der Zwaan, B. (2015). Post-2020 climate agreements in the major economies assessed in the light of global models. Nature Climate Change. [CrossRef]

- Tay, R. Y., Li, H., Wang, H., Lin, J., Ng, Z. K., Shivakumar, R., Bolker, A., Shakerzadeh, M., Tsang, S. H., & Teo, E. H. T. (2023). Advanced nano boron nitride architectures: Synthesis, properties and emerging applications. Nano Today, 53, 102011. [CrossRef]

- Tiano, A. L., Park, C., Lee, J. W., Luong, H. H., Gibbons, L. J., Chu, S.-H., Applin, S., Gnoffo, P., Lowther, S., Kim, H. J., Danehy, P. M., Inman, J. A., Jones, S. B., Kang, J. H., Sauti, G., Thibeault, S. A., Yamakov, V., Wise, K. E., Su, J., & Fay, C. C. (2014). Boron nitride nanotube: synthesis and applications (V. K. Varadan, Ed.; p. 906006). [CrossRef]

- Vatanpour, V., Naziri Mehrabani, S. A., Keskin, B., Arabi, N., Zeytuncu, B., & Koyuncu, I. (2021). A Comprehensive Review on the Applications of Boron Nitride Nanomaterials in Membrane Fabrication and Modification. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research, 60(37), 13391–13424. [CrossRef]

- Vidya, Mandal, L., Verma, B., & Patel, P. K. (2020). Review on polymer nanocomposite for ballistic & aerospace applications. Materials Today: Proceedings, 26, 3161–3166. [CrossRef]

- Vignesh, S., Surendran, R., Sekar, T., & Rajeswari, B. (2021). Ballistic impact analysis of graphene nanosheets reinforced kevlar-29. Materials Today: Proceedings, 45, 788–793. [CrossRef]

- Walley, S. M. (2014). An Introduction to the Properties of Silica Glass in Ballistic Applications. Strain, 50(6), 470–500. [CrossRef]

- Wambua, P., Vangrimde, B., Lomov, S., & Verpoest, I. (2007). The response of natural fibre composites to ballistic impact by fragment simulating projectiles. Composite Structures, 77(2), 232–240. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B., Seabrook, S. A., Nedumpully-Govindan, P., Chen, P., Yin, H., Waddington, L., Epa, V. C., Winkler, D. A., Kirby, J. K., Ding, F., & Ke, P. C. (2015). Thermostability and reversibility of silver nanoparticle–protein binding. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics, 17(3), 1728–1739. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Lee, C. H., & Yap, Y. K. (2010). Recent advancements in boron nitride nanotubes. Nanoscale, 2(10), 2028. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., Wang, H., An, L., Zhang, B., Huang, X., Wen, G., Zhong, B., & Yu, Y. (2020). Facile fabrication of Hildewintera-colademonis-like hexagonal boron nitride/carbon nanotube composite having light weight and enhanced microwave absorption. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science, 564, 454–466. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Li, G., Wu, S., Wei, Y., Meng, W., Xie, Y., Cui, Y., Lian, X., Chen, Y., & Zhang, X. (2017). Hydrogen generation from alkaline NaBH4 solution using nanostructured Co–Ni–P catalysts. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 42(26), 16529–16537. [CrossRef]

- Weng, Q., Wang, X., Wang, X., Bando, Y., & Golberg, D. (2016). Functionalized hexagonal boron nitride nanomaterials: emerging properties and applications. Chemical Society Reviews, 45(14), 3989–4012. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, H. J., Yang, J., Hou, J. G., & Zhu, Q. (2005). Are fluorinated boron nitride nanotubes n-type semiconductors? Applied Physics Letters, 87(24). [CrossRef]

- Xu, M., Watanachaturaporn, P., Varshney, P., & Arora, M. (2005). Decision tree regression for soft classification of remote sensing data. Remote Sensing of Environment, 97(3), 322–336. [CrossRef]

- Yan, K., Wu, X., Wu, X., Hoadley, A., Xu, X., Zhang, J., & Zhang, L. (2015). Sensitivity analysis of oxy-fuel power plant system. Energy Conversion and Management. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H., Zou, C., Huang, M., Zang, M., & Chen, S. (2023). High-fidelity computational modeling of scratch damage in automotive coatings with machine learning-driven identification of fracture parameters. Composite Structures, 316, 117027. [CrossRef]

- Yanxing, Z., Maoqiong, G., Yuan, Z., Xueqiang, D., & Jun, S. (2019). Thermodynamics analysis of hydrogen storage based on compressed gaseous hydrogen, liquid hydrogen and cryo-compressed hydrogen. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. [CrossRef]

- Yeh, Y.-W., Raitses, Y., Koel, B. E., & Yao, N. (2017). Stable synthesis of few-layered boron nitride nanotubes by anodic arc discharge. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 3075. [CrossRef]

- Yu, D. P., Sun, X. S., Lee, C. S., Bello, I., Lee, S. T., Gu, H. D., Leung, K. M., Zhou, G. W., Dong, Z. F., & Zhang, Z. (1998). Synthesis of boron nitride nanotubes by means of excimer laser ablation at high temperature. Applied Physics Letters, 72(16), 1966–1968. [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y., Lago, E., Santillo, C., Del Río Castillo, A. E., Hao, S., Buonocore, G. G., Chen, Z., Xia, H., Lavorgna, M., & Bonaccorso, F. (2020). An anisotropic layer-by-layer carbon nanotube/boron nitride/rubber composite and its application in electromagnetic shielding. Nanoscale, 12(14), 7782–7791. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., & Wang, C. (2016). Mechanical properties of hybrid boron nitride–carbon nanotubes. Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics, 49(15), 155305. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Tian, Q.-F., Liu, S.-S., & Sun, L.-X. (2008a). The destabilization mechanism and de/re-hydrogenation kinetics of MgH2–LiAlH4 hydrogen storage system. Journal of Power Sources, 185(2), 1514–1518. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H., Ding, J., Zhao, C., Wang, J., Fang, Y., & Zhu, J. (2023). Sustainable Mass Production of Ultrahigh-Aspect-Ratio Hexagonal Boron Nitride Nanosheets for High-Performance Composites. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering, 11(12), 4633–4642. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G. W., Zhang, Z., Bai, Z. G., & Yu, D. P. (1999). Catalyst effects on formation of boron nitride nano-tubules synthesized by laser ablation. Solid State Communications, 109(8), 555–559. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, W., Pan, G., Gu, W., Zhou, S., Hu, Q., Gu, Z., Wu, Z., Lu, S., & Qiu, H. (2023). Hydrogen economy driven by offshore wind in regional comprehensive economic partnership members. Energy & Environmental Science, 16(5), 2014–2029. [CrossRef]

- Zochowski, P., Bajkowski, M., Grygoruk, R., Magier, M., Burian, W., Pyka, D., Bocian, M., & Jamroziak, K. (2021). Ballistic Impact Resistance of Bulletproof Vest Inserts Containing Printed Titanium Structures. Metals, 11(2), 225. [CrossRef]

- Zochowski, P., Cegła, M., Szczurowski, K., Mączak, J., Bajkowski, M., Bednarczyk, E., Grygoruk, R., Magier, M., Pyka, D., Bocian, M., Jamroziak, K., Gieleta, R., & Prasuła, P. (2023). Experimental and numerical study on failure mechanisms of the 7.62 × 25 mm FMJ projectile and hyperelastic target material during ballistic impact. Continuum Mechanics and Thermodynamics. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).