Submitted:

08 June 2025

Posted:

09 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

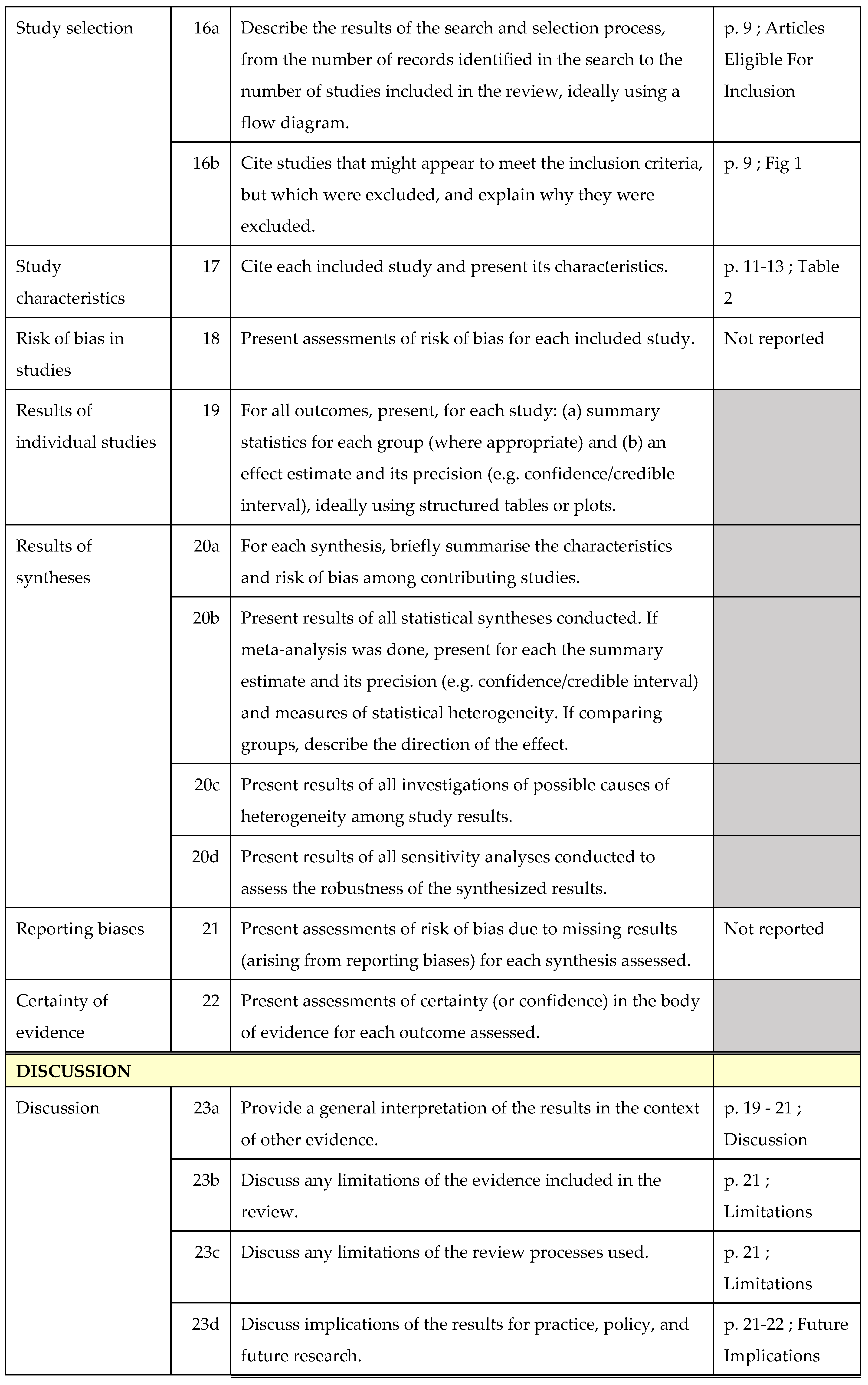

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

- primary research sources

- published between January 2015 and January 2025

- qualitative, quantitative and/or mixed methods articles examining pharmacy students’ perceptions of MyDispenseTM

- published in English.

- reviews, conference abstracts, meta-analyses, commentary studies, grey literature

- not published in English

- not investigating the use of MyDispenseTM

- did not include a pharmacy student population.

2.3. Study Selection

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis:

3. Results

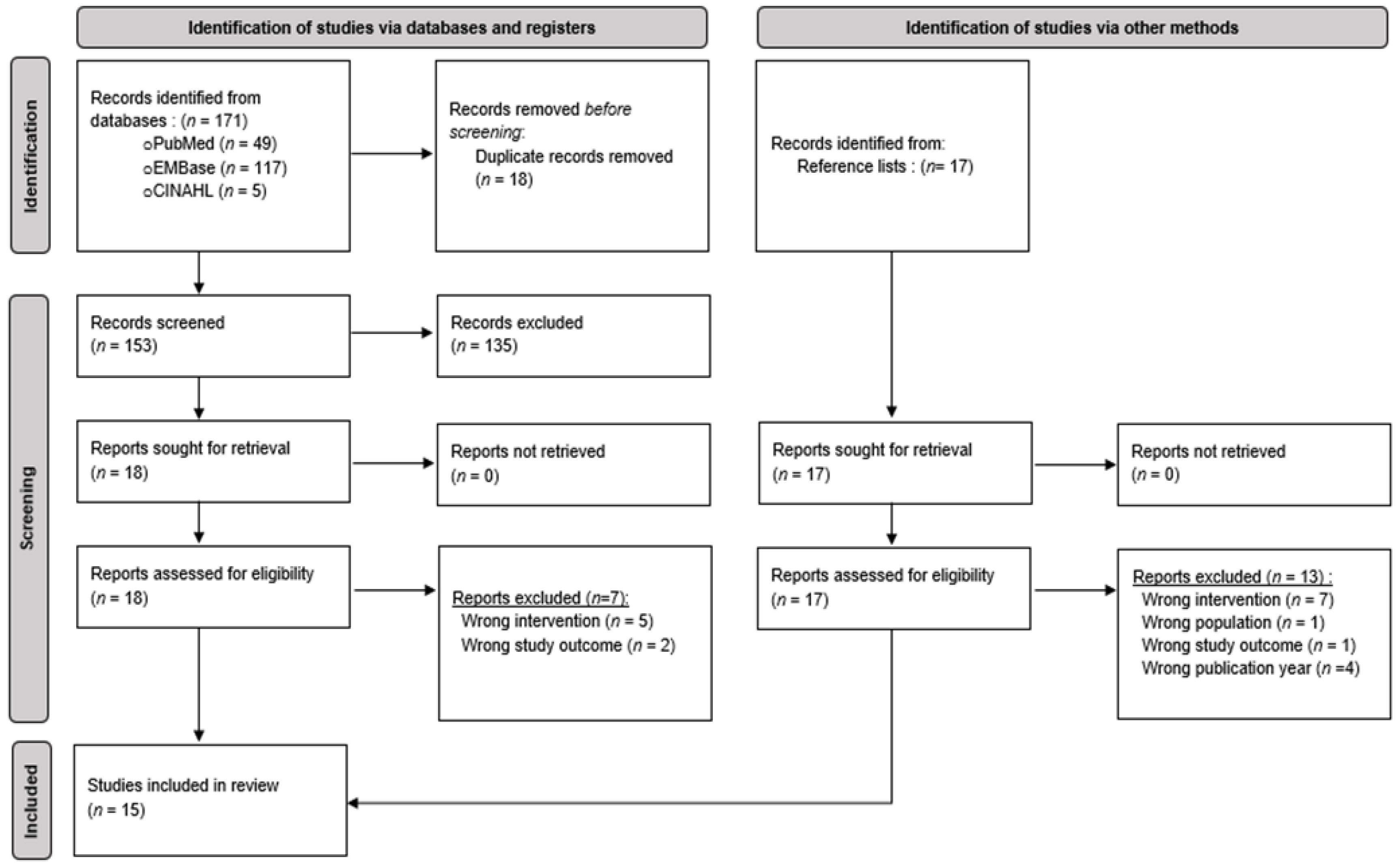

3.1. Articles Eligible for Inclusion

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

3.3. Summary of Identified Facilitators

3.3.1. Facilitator Theme I: Develops Competency

3.3.2. Facilitator Theme II: Accessibility

3.3.3. Facilitator Theme III: Engaging Learning Experience

3.3.4. Facilitator Theme IV: Safe Learning Environment

3.4. Summary of Identified Barriers

3.4.1. Barrier Theme I: Learning Curve

3.4.2. Barrier Theme II: IT Issues

3.4.3. Barrier Theme III: Limited Realism & Applications

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Future Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

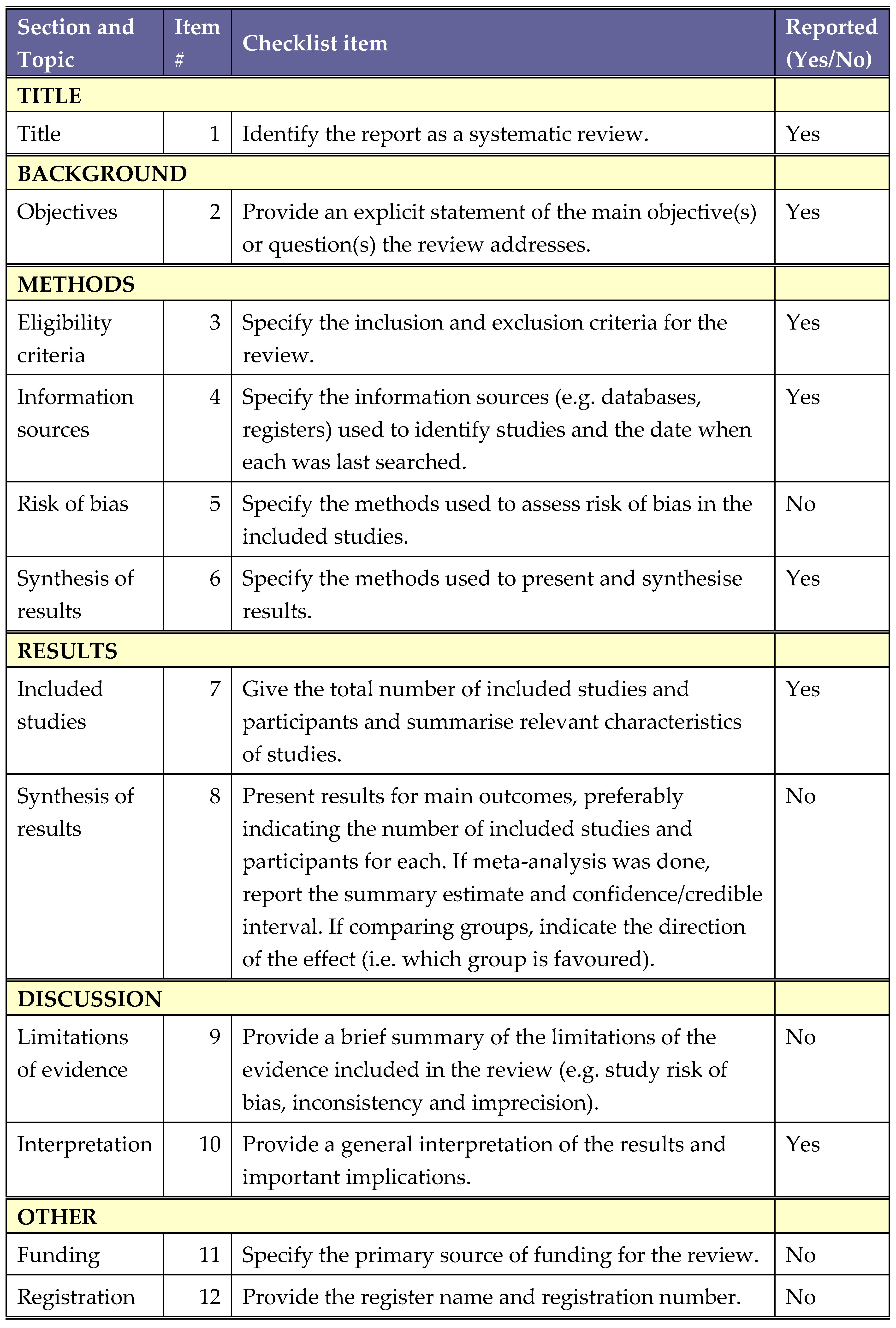

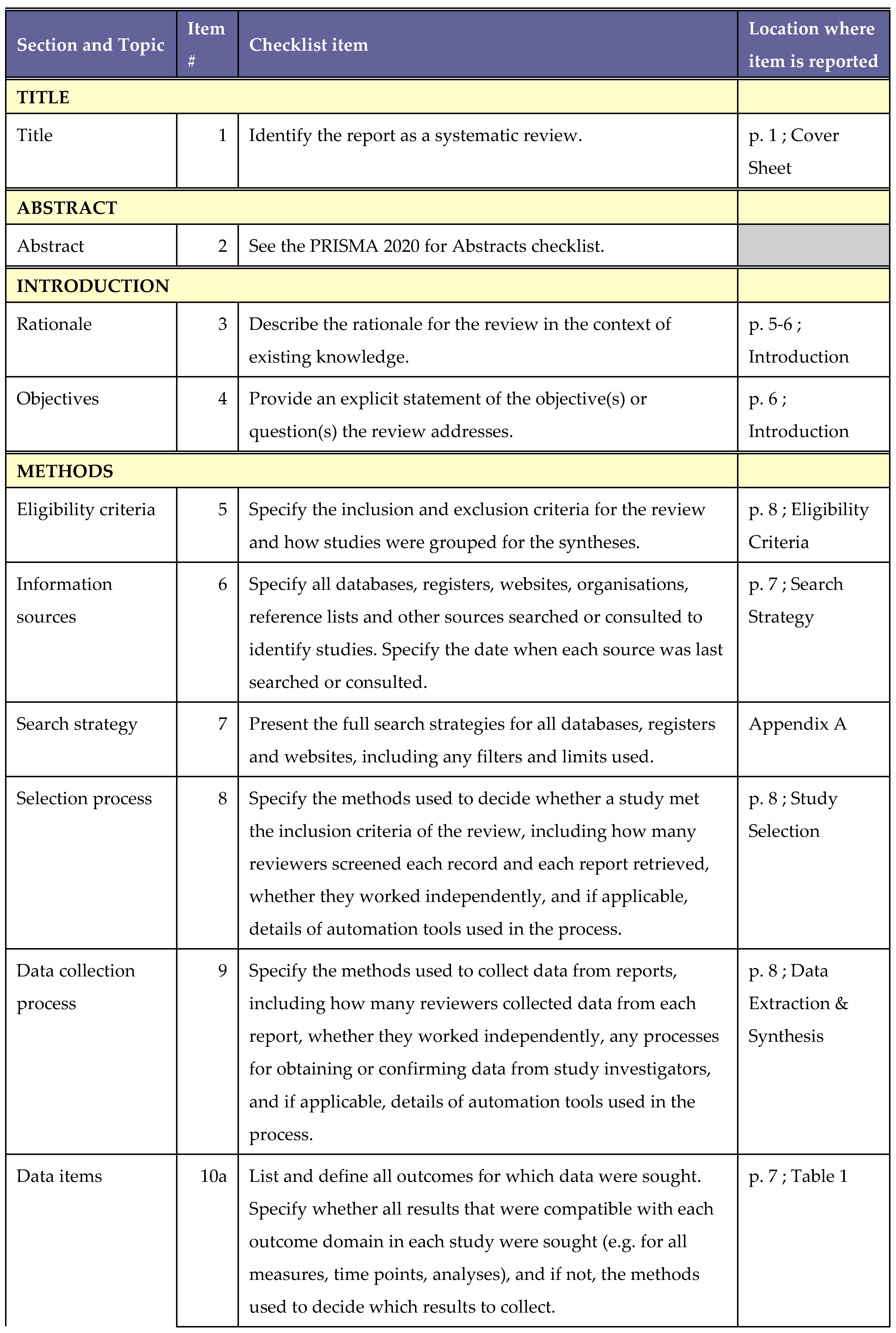

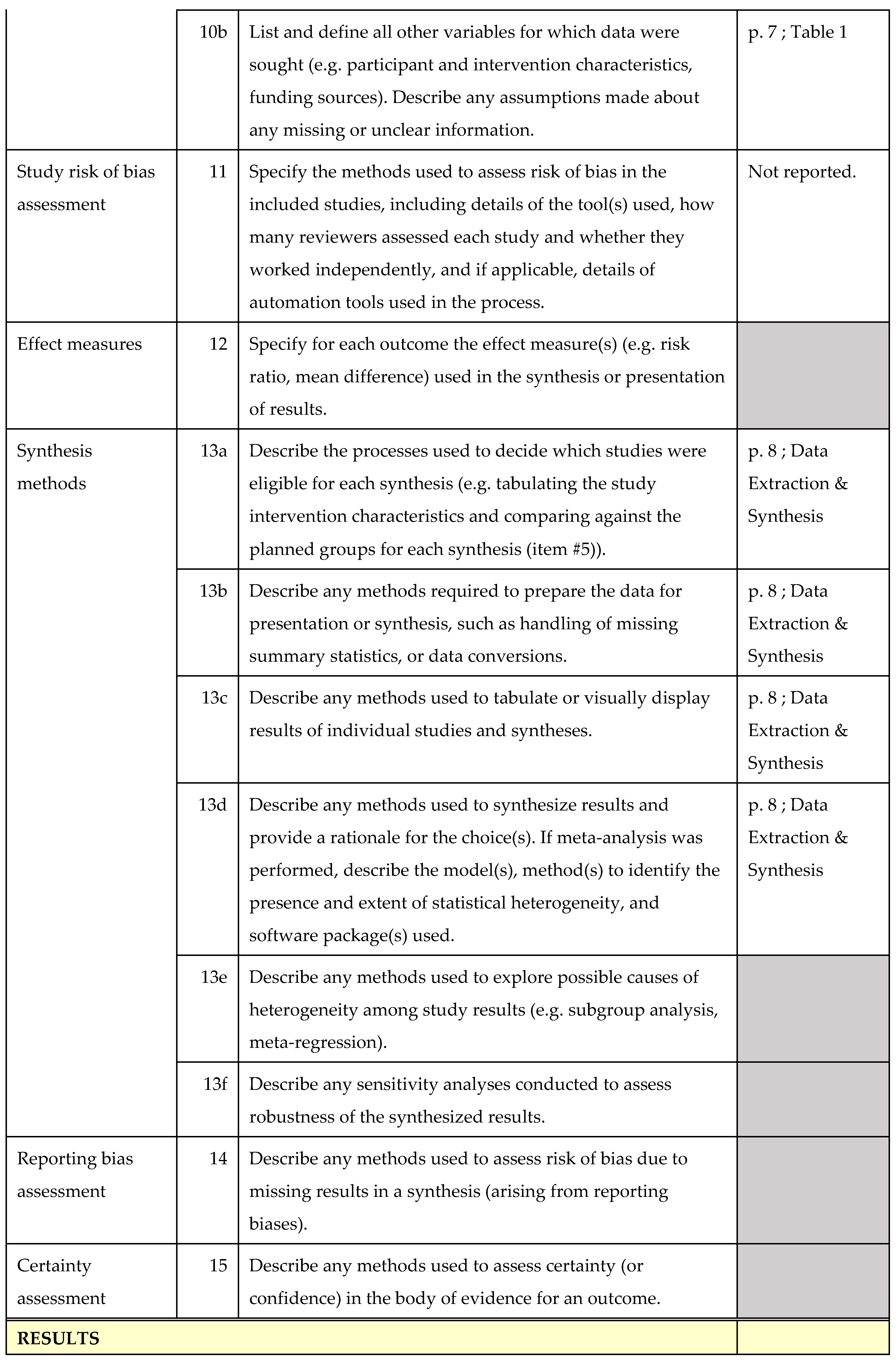

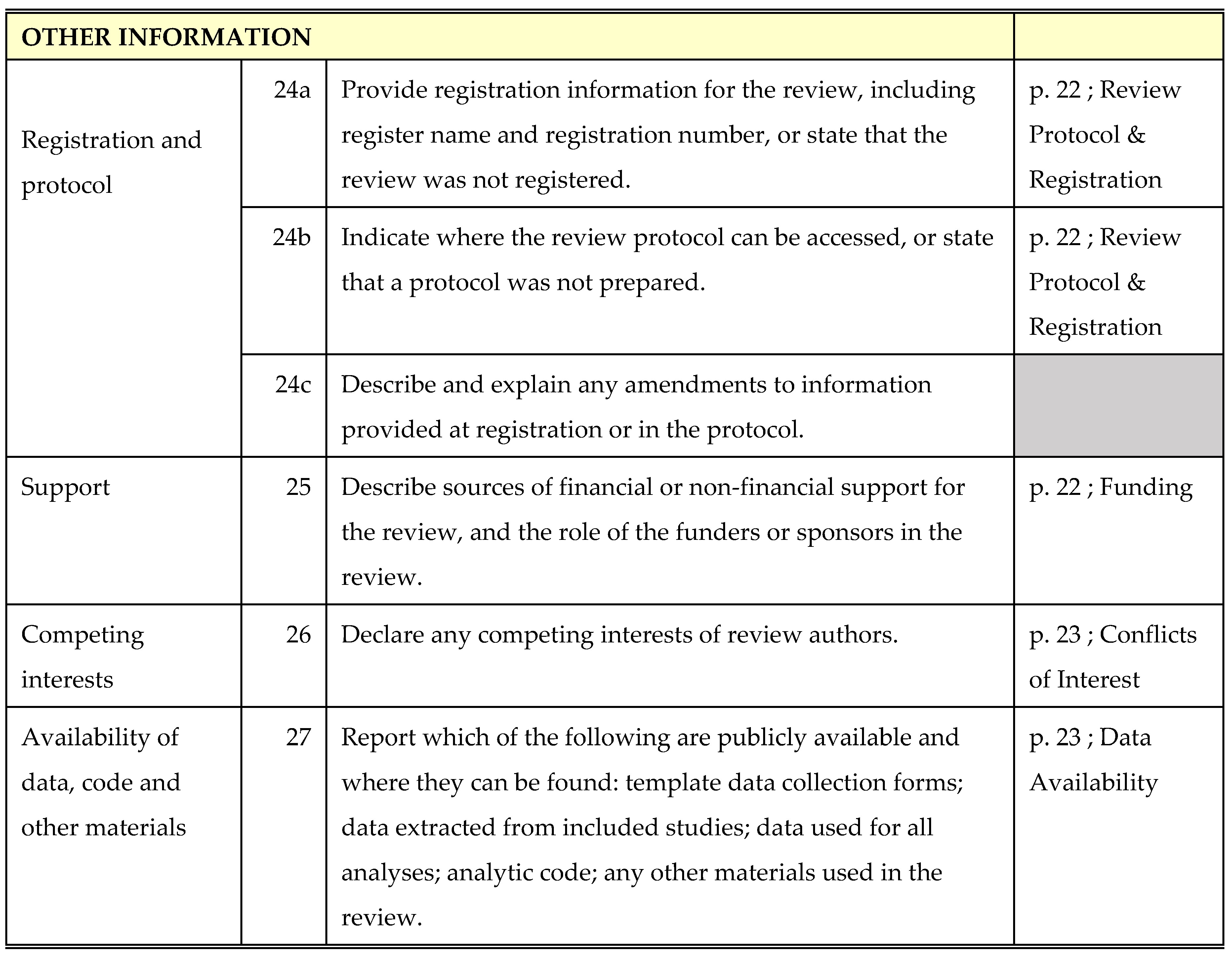

Appendix A. PRISMA Checklist

Appendix B. Search Strategy

| Database | Date of Search | Search Strings | Terms Used | Results |

| PubMed | 28th January 2025 | S1 | (perception[MeSH Terms]) OR (attitude[MeSH Terms])) OR (facilitator)) OR (enabler)) OR (barrier)) OR (obstacle)) OR (challenge) | 4,224,261 |

| S2 | ("MyDispense") OR (computer simulation[MeSH Terms])) OR (patient simulations[MeSH Terms])) OR (educational technologies[MeSH Terms])) OR ("virtual patient simulator"[tiab:~3])) OR ("dispensing simulation") | 440,869 |

||

| S3 | ((students[MeSH Terms]) OR (pharmacy students[MeSH Terms])) | 185,856 |

||

| S4 | ((pharmacy[MeSH Terms]) OR (pharmacy education[MeSH Terms])) | 26,507 |

||

| S5 | S1 AND S2 AND S3 AND S4 | 49 |

| Database | Date of Search | Search Strings | Terms Used | Results |

| CINAHL | 28th January 2025 | S1 | (MM "Attitude") OR "beliefs" OR "views" OR "opinions" OR "barriers" OR "challenges" OR "obstacles" OR "facilitators" OR "enablers" | 567,858 |

| S2 | “Mydispense” OR “patient simulation” OR “virtual simulation” OR “computer simulation” OR “simulation” N2 (“patient” OR “virtual” OR “dispensing”) | 27,672 | ||

| S3 | (MH "Students") OR (MH "Students, Pharmacy") | 22,056 | ||

| S4 | (MH "Education, Pharmacy") OR "pharmacy" | 13,743 | ||

| S5 | S1 AND S2 AND S3 AND S4 | 5 |

| Database | Date of Search | Search Strings | Terms Used | Results |

| Embase | 28th January 2025 | S1 | 'attitude'/de OR 'attitude' OR 'beliefs'/de OR 'beliefs' OR 'perception'/de OR 'perception' OR 'challenge'/de OR 'challenge' OR 'obstacles'/de OR 'obstacles' OR 'barriers'/de OR 'barriers' OR 'facilitator'/de OR 'facilitator' OR enablers | 2,003,993 |

| S2 | 'mydispense' OR 'computer simulation'/exp OR 'computer simulation' OR 'patient simulation'/exp OR 'patient simulation' OR ((virtual OR patient OR dispensing) NEAR/2 simulation) | 197,410 | ||

| S3 | 'student'/exp OR 'student' OR 'pharmacy student'/exp OR 'pharmacy student' | 617,087 | ||

| S4 | 'pharmacy'/exp OR pharmacy OR 'pharmacy education'/exp OR 'pharmacy education' | 1,299,905 |

||

| S5 | S1 AND S2 AND S3 AND S4 | 117 |

References

- Pharmaceutical Society of Ireland (PSI), Accreditation Standards for the Five Year Master’s Degree Programmes in Pharmacy [Internet]. Ireland :Pharmaceutical Society of Ireland (PSI) , 2023 [cited 2025 March 20th] Available from: https://www.psi.ie/educationand-training/training-become-pharmacistireland/accreditation-and-standards-0.

- Atkinson J, Rombaut B, Pozo A, Rekkas D, Veski P, Hirvonen J, et al. The Production of a Framework of Competences for Pharmacy Practice in the European Union. Pharmacy. 2014;2:161–74. https://doi.org/ 10.3390/pharmacy2020161.

- Hall K, Musing E, Miller DA, Tisdale JE. Experiential Training for Pharmacy Students: Time for a New Approach. Can J Hosp Pharm [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2025 Mar 23];65. Available from: http://www.cjhp-online.ca/index.php/cjhp/article/view/1159.

- Mak V, Fitzgerald J, Holle L, Vordenberg SE, Kebodeaux C. Meeting pharmacy educational outcomes through effective use of the virtual simulation MyDispense. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2021;13:739–42. [CrossRef]

- Marriott JL. Use and evaluation of “virtual” patients for assessment of clinical pharmacy undergraduates. Pharm Educ. 2007;7:341–9. Available from: https://pharmacyeducation.fip.org/pharmacyeducation/article/view/163.

- Thompson J, White S, Chapman S. Virtual patients as a tool for training pre-registration pharmacists and increasing their preparedness to practice: A qualitative study. Suppiah V, editor. PLOS ONE. 2020;15:e0238226. [CrossRef]

- Seybert AL, Smithburger PL, Benedict NJ, Kobulinsky LR, Kane-Gill SL, Coons JC. Evidence for simulation in pharmacy education. JACCP J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2019;2:686–92. [CrossRef]

- Han, Heeyoung & Resch, David & Kovach, Regina. Educational Technology in Medical Education. Teaching and learning in medicine. 25. S39-S43; 2013. [CrossRef]

- Maarek J-M. Benefits of Active Learning Embedded in Online Content Material Supporting a Flipped Classroom. 2018 ASEE Annu Conf Expo Proc [Internet]. Salt Lake City, Utah: ASEE Conferences; 2018 [cited 2025 Mar 21]. p. 29845. Available from: http://peer.asee.org/29845.

- Dimock M. Where Millennials end and Generation Z begins | Pew Research Center. [Internet]. Washington DC, USA;2019 [cited 2025 Mar 21] Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2019/01/17/where-millennials-end-and-generation-z-begins/.

- Shatto B, Erwin K. Teaching Millennials and Generation Z: Bridging the Generational Divide. Creat Nurs. 2017;23:24–8. [CrossRef]

- Monash University. MyDispense [Internet]. Melbourne, Australia. Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Monash University; 2025. [cited 2025 Mar 21] Available from : https://info.mydispense.monash.edu/.

- Smith MA, Mohammad RA, Benedict N. Use of Virtual Patients in an Advanced Therapeutics Pharmacy Course to Promote Active, Patient-Centered Learning. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78:125. [CrossRef]

- Phanudulkitti C, Kebodeaux C, Vordenberg SE. Use of the Virtual Simulation Tool ‘MyDispense’ By Pharmacy Programs in the United States. Am J Pharm Educ. 2022;86:ajpe8827. [CrossRef]

- Gharib AM, Peterson GM, Bindoff IK, Salahudeen MS. Potential Barriers to the Implementation of Computer-Based Simulation in Pharmacy Education: A Systematic Review. Pharmacy. 2023;11:86. [CrossRef]

- McDowell J, Styles K, Sewell K, Trinder P, Marriott J, Maher S, et al. A Simulated Learning Environment for Teaching Medicine Dispensing Skills. Am J Pharm Educ. 2016;80:11. [CrossRef]

- Gharib AM, Peterson GM, Bindoff IK, Salahudeen MS. Exploring barriers to the effective use of computer-based simulation in pharmacy education: a mixed-methods case study. Front Med. 2024;11:1448893. [CrossRef]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;n71. [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5:210. [CrossRef]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. http://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Waghel RC, Wilson JA. Exploring community pharmacy work experience impact on errors and omissions performance and MyDispense perceptions. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2025;17:102235. [CrossRef]

- Rude TA, Eukel HN, Ahmed-Sarwar N, Burke ES, Anderson AN, Riskin J, et al. An Introductory Over-the-Counter Simulation for First-Year Pharmacy Students Using a Virtual Pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2023;87:ajpe8940. [CrossRef]

- Tabulov C, Vascimini A, Ruble M. Using a virtual simulation platform for dispensing pediatric prescriptions in a community-based pharmaceutical skills course. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2023;15:1052–9. [CrossRef]

- Deneff M, Holle LM, Fitzgerald JM, Wheeler K. A Novel Approach to Pharmacy Practice Law Instruction. Pharmacy. 2021;9:75. [CrossRef]

- Ambroziak K, Ibrahim N, Marshall VD, Kelling SE. Virtual simulation to personalize student learning in a required pharmacy course. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2018;10:750–6. [CrossRef]

- Ferrone M, Kebodeaux C, Fitzgerald J, Holle L. Implementation of a virtual dispensing simulator to support US pharmacy education. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2017;9:511–20. [CrossRef]

- Shin J, Tabatabai D, Boscardin C, Ferrone M, Brock T. Integration of a Community Pharmacy Simulation Program into a Therapeutics Course. Am J Pharm Educ. 2018;82:6189. [CrossRef]

- Phanudulkitti C, Leelakanok N, Nakpun T, Kittisopee T, Farris KB, Vordenberg SE. Impacts of the dispensing program(MyDispense®) on pharmacy students’ learning outcomes with relevant perceptions: A quasi-intervention study. Thai J Pharm Sci [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 Mar 15];48. Available from: https://digital.car.chula.ac.th/tjps/vol48/iss2/4.

- Al-Diery T, Hejazi T, Al-Qahtani N, ElHajj M, Rachid O, Jaam M. Evaluating the use of virtual simulation training to support pharmacy students’ competency development in conducting dispensing tasks. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2024;16:102199. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen KT, Dao ML, Nguyen KN, Nguyen HN, Nguyen HT, Nguyen HQ. Perception of learners on the effectiveness and suitability of MyDispense: a virtual pharmacy simulation and its integration in the clinical pharmacy module in Vietnam. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23:790. [CrossRef]

- Amatong AJ, Asentista H, Diasnes CM, Erispe KD, Malintad K, Paderog HG, et al. Learners’ Perceptions on My Dispense Virtual Simulation in the Philippines. 2022;7. Available from : https://ijisrt.com/assets/upload/files/IJISRT22JUN1465_(1).pdf.

- Amirthalingam P, Hamdan AM, Veeramani VP, A Sayed Ali M. A comparison between student performances on objective structured clinical examination and virtual simulation. Pharm Educ. 2022;22:466–73. [CrossRef]

- Dameh M. A Report of Second Year Pharmacy Students’ Experience after Using a Virtual Dispensing Program. J Pharma Care Health Sys 2015, S2:003. [CrossRef]

- Slater N, Mason T, Micallef R, Ramkhelawon M, May L. Enabling Access to Pharmacy Law Teaching during COVID-19: Student Perceptions of MyDispense and Assessment Outcomes. Pharmacy. 2023;11:44. [CrossRef]

- Khera HK, Mannix E, Moussa R, Mak V. MyDispense simulation in pharmacy education: a scoping review. J Pharm Policy Pract. 2023;16:110. [CrossRef]

- Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Academic medicine. 1990 Sep 1;65(9):S63-7. [CrossRef]

- Benedict N, Smithburger P, Donihi AC, Empey P, Kobulinsky L, Seybert A, et al. Blended Simulation Progress Testing for Assessment of Practice Readiness. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81:14. [CrossRef]

- Kavanagh DJ, Boakes RA. Abilio C. de Almeida Neto and Shalom I. Benrimoj.

- Seybert AL, Kobulinsky LR, McKaveney TP. Human Patient Simulation in a Pharmacotherapy Course. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72:37. [CrossRef]

- Gharib AM, Bindoff IK, Peterson GM, Salahudeen MS. Exploring global perspectives on the use of computer-based simulation in pharmacy education: a survey of students and educators. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15:1494569. [CrossRef]

- DeLucenay A, Conn K, Corigliano A. An evaluation of the impact of immediate compared to delayed feedback on the development of counselling skills in pharmacy students. Pharm Educ. 2017 Oct. 24;17. Available from https://pharmacyeducation.fip.org/pharmacyeducation/article/view/480.

- Steuber TD, Janzen KM, Walton AM, Nisly SA. Assessment of Learner Metacognition in a Professional Pharmacy Elective Course. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81:6034. [CrossRef]

- Beshir SA, Mohamed AP, Soorya A, Sir Loon Goh S, Moussa El-Labadd E, Hussain N, et al. Virtual patient simulation in pharmacy education: A systematic review. Pharm Educ. 2022;22:954–70. [CrossRef]

- Durand E, Kerr A, Kavanagh O, Crowley E, Buchanan B, Bermingham M. Pharmacy students’ experience of technology-enhanced learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Explor Res Clin Soc Pharm. 2023;9:100206. [CrossRef]

- Henning K, Ey S, Shaw D. Perfectionism, the impostor phenomenon and psychological adjustment in medical, dental, nursing and pharmacy students. Med Educ. 1998;32:456–64. [CrossRef]

- Barry Issenberg S, Mcgaghie WC, Petrusa ER, Lee Gordon D, Scalese RJ. Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: a BEME systematic review. Med Teach. 2005;27:10–28. [CrossRef]

- Bindoff I, Ling T, Bereznicki L, Westbury J, Chalmers L, Peterson G, et al. A Computer Simulation of Community Pharmacy Practice for Educational Use. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78:168. [CrossRef]

- The relationship between digital literacy and academic performance of college students in blended learning: the mediating effect of learning adaptability. Adv Educ Technol Psychol [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Apr 3];7. Available from: https://www.clausiuspress.com/article/8204.html.

- Al-Dahir S, Bryant K, Kennedy KB, Robinson DS. Online Virtual-Patient Cases Versus Traditional Problem-Based Learning in Advanced Pharmacy Practice Experiences. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78:76. [CrossRef]

- Bindoff I, Ling T, Bereznicki L, Westbury J, Chalmers L, Peterson G, et al. A Computer Simulation of Community Pharmacy Practice for Educational Use. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78:168. [CrossRef]

- Bernaitis N, Baumann-Birkbeck L, Alcorn S, Powell M, Arora D, Anoopkumar-Dukie S. Simulated patient cases using DecisionSimTM improves student performance and satisfaction in pharmacotherapeutics education. Curr Pharm Teach Learn. 2018;10:730–5. [CrossRef]

- Duffull S, Peterson A, Chai B, Cho F, Opoku J, Sissing T, et al. Exploring a scalable real-time simulation for interprofessional education in pharmacy and medicine. MedEdPublish [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2025 Mar 22];9. Available from: https://mededpublish.org/articles/9-240.

- Williams V, Boylan A-M, Nunan D. Critical appraisal of qualitative research: necessity, partialities and the issue of bias. BMJ Evid-Based Med. 2020;25:9–11. [CrossRef]

| PICO | Definitions |

| Population (P) | Pharmacy Students |

| Intervention (I) | Any study that collects pharmacy students’ opinion, perception, satisfaction or attitudes on using MyDispenseTM in a recognized pharmacy course |

| Comparison (C) | Both types of study i.e. with/without a comparison group |

| Outcomes (O) | Pharmacy students’ perceptions on the barriers and facilitators to using MyDispenseTM |

| Author (Year) ; Country | Description of study design | Study Participants | Study Outcomes | Method(s) of data collection | Identified Barrier(s) | Identified Facilitator(s) |

| Waghel et al. (2025) USA |

Mixed-methods, Cross-sectional |

Y1 PharmD students enrolled in a pharmacy skills lab course (n = 71) |

To evaluate the correlation between pharmacy experience and performance on MyDispense™ E&O activities To evaluate students perceptions of MyDispense™ E&O activities |

Questionnaire investigating prior pharmacy experience and MyDispense™ perceptions | Initial learning curve to use software IT incompatibilities |

Provides high fidelity learning interactive environment Provides immediate feedback Easy to navigate |

| Phanudulkitti et al. (2024) Thailand |

Mixed-methods, Longitudinal |

Y4 Pharmacy students enrolled in a Pharmacotherapeutic I course (n = 136) |

To evaluate MyDispense™ impact on pharmacy students’ learning outcomes To evaluate students’ perceptions and instructors’ views of MyDispense™ |

Five-part questionnaire Part three comprised of five closed-ended questions regarding MyDispense™ and one item for additional student feedback |

Learning how to use software initially | Can practice dispensing skills at any time or place Provides feedback instantly at end of exercises |

| Al-Diery et al. (2024) Qatar |

Quantitative, Longitudinal |

Y1 pharmacy students enrolled in a Professional Skills II course (n = 55) | To evaluate impact of MyDispense™ on students’ self-reported reaction, learning and accuracy in dispensing tasks | Pre-post intervention seven-point Likert scale questionnaire based on Kirkpatrick’s Model |

Does not simulate true patient-practitioner interactions | Offers immediate feedback Allows for practice in a safe virtual dispensing environment |

| Nguyen et al. (2023) Vietnam |

Mixed methods, Longitudinal |

Y4 and Y5 pharmacy students enrolled at UMP Vietnam (n = 69) Pharmacists with at least one year clinical practice experience (n = 23) |

To investigate learners’ perspective on effectiveness of MyDispense™ in learning dispensing skills To investigate the suitability of MyDispense™ integration into Vietnamese pharmacy curricula |

Online five-point Likert scale questionnaire Semi-structured interviews |

Complicated learning process Inconsistent quality of product images |

High degree of user interactivity Ability to self-learn by immediate feedback Diverse medication database |

| Rude et al. (2023) USA |

Quantitative, Longitudinal |

Y1 PharmD students enrolled at NDSU and VCU (n = 142) | To assess the impact of MyDispense™ on students’ knowledge and confidence of OTC medications To assess overall student perceptions of MyDispense™ activities |

Pre-post questionnaire with closed-ended demographic, confidence and knowledge-based questions A five-point modified perception scale was added to post-questionnaire. |

May not be as effective as traditional learning methods | Effective way to learn new information Encourages active thinking |

| Tabulov et al. (2023) USA |

Quantitative, Longitudinal |

Y1 PharmD students enrolled in a pharmaceutical skills 1 course (n = 64) | To describe a paediatric simulation on MyDispense™ completed by first year students To review student perceptions on confidence and knowledge after using MyDispense™ |

Pre-post online questionnaire with yes/no items and five-point Likert scale | Initial learning curve |

Low-stakes environment that allows students to make mistakes without harm More realistic than paper-based case learning |

| Slater et al. (2023) United Kingdom |

Mixed methods, Cross-sectional |

Y2 MPharm students enrolled in a pharmacy law and ethics module (n = 147) | To evaluate MyDispense™ impact on assessment performance To evaluate student perceptions of MyDispense™ |

24 item questionnaire consisting of closed and open-ended questions and five point Likert-scale |

User interface could be improved Difficulties navigating software initially |

Highly accessible and can practice dispensing skills from home Provides opportunity to repeat exercises |

| Faller et al. (2022) Philippines |

Mixed methods, Cross-sectional |

Y2 and Y3 pharmacy students across four universities (n = 322) | To determine learners perceptions of MyDispense™ | Three-part questionnaire including demographics, a five-point Likert scale and open-ended questions on student perceptions | Technical and internet connectivity issues | High-fidelity learning environment without patient harm |

| Amirthalingam et al. (2022) Saudi Arabia |

Mixed-methods, Cross-sectional |

Y4 pharmacy students enrolled in an Introductory Pharmacy Practice Experience 2 course (n = 69) | To compare pharmacy students’ performance on MyDispense™ vs. in-person OSCEs To explore students’ perceptions of MyDispense™ |

Post-simulation questionnaire with five-point Likert scale and open-ended questions | Can be complicated to use Interactions are robotic in nature |

Helps improve patient communication skills Enhances student confidence in patient care |

| Deneff et al. (2021) USA |

Qualitative, Cross-sectional |

Y3 PharmD students enrolled in a pharmacy law and ethics course in 2017 (n = 38) and 2018 (n = 28) |

To evaluate the utility of MyDispense™ for pharmacy law instruction To evaluate students’ perceptions of MyDispense™ for pharmacy law instruction |

Questionnaire with close-ended questions graded on a four and five-point Likert Scale in 2017 and 2018, respectively, and open-ended questions | Initial learning curve Some pharmacy law exercises may not be suitable for MyDispense™ |

More engaging than traditional classroom teaching |

| Ambroziak et al. (2018) USA |

Quantitative, Longitudinal |

Y1 PharmD students enrolled in a Pharmacy Practice Skills 1 course (n = 85) | To implement MyDispense™ cases into a first year PharmD course To assess student perceptions of their learning using MyDispense™ |

Pre-simulation questionnaire investigating prior pharmacy experience Post-simulation questionnaire investigating perceptions of MyDispense™ using open and closed-ended questions |

Learning how to navigate program | Effective tool to learn dispensing skills e.g.) analysing prescriptions |

| Ferrone et al. (2017) USA |

Mixed-methods, Cross-sectional |

Y1 and Y3 PharmD students enrolled in UCSF, UConn, STLCOP (n =241) | To implement MyDispense™ simulation into US pharmacy curricula To assess students’ satisfaction of MyDispense™ |

Questionnaire with five-point Likert scale, demographics on pharmacy experience and open-ended questions on MyDispense™ perceptions | Can be difficult to learn at first May need to be adapted for different regions to be more culturally appropriate |

Straightforward to learn Affords opportunity to make mistakes More realistic than paper based cases |

| Shin et al. (2016) USA |

Quantitative, Longitudinal |

Y2 PharmD students enrolled in a Therapeutics II course (n = 117) | To demonstrate feasibility of integrating MyDispense™ into a therapeutics course To measure students’ perceptions on MyDispense™ and its impact on learning |

Three post-intervention questionnaires consisting of 10 to 17 items | Limited capacity to simulate interactions with prescribers and patients |

Provides immediate feedback Can practice cases at any time / place Safe, low stakes practice environment |

| McDowell et al. (2016) Australia |

Mixed methods, Cross-sectional |

Y1 BPharm students enrolled in PAC1311 and PAC1322 modules at Monash University (n = 199) | To develop MyDispense™ for students to learn dispensing skills in a low-stakes environment To explore students’ perceptions of MyDispense™ |

38 item questionnaire with five point Likert-scale questions and open ended questions | User interface is not responsive Technical and server connectivity issues |

Allows for “safe” dispensing without patient harm Stimulating learning environment |

| Dameh (2015) UAE |

Mixed-methods, Cross-sectional |

Y2 female pharmacy students enrolled at FCHS (n = 33) | To report pharmacy students’ experience after using MyDispense™ | Questionnaire consisting of five point Likert-scale and open ended questions on student perceptions Focus group discussion to allow students to elaborate perceptions |

Technical issues cause student frustration |

Highly accessible for students Gives dispensing practice prior to working in real-life scenarios |

| Facilitator theme(s) | Description of facilitator theme(s) | Supporting Quotations |

| Develops Competency | Enhanced patient communication skills Increased confidence in dispensing process Diverse medication database allows students to familiarise themselves with brand names |

“I think this is a neat and useful tool for pharmacy students to learn before their community pharmacy rotation, especially for those who have never had experience in a community pharmacy before”[26] “Gave those w/o experience a simulation of experience”[21] “It helps me get used to some brand names, because its less common when I’m studying”[30] |

| Accessibility | Ability for students use software at any suitable time and/or place Can be used on several devices e.g.) tablets, phones, laptops |

“I liked that MyDispenseTM can be used in my phone so I can do it anywhere when I have time”[30] “I think this program is great. I can practice dispensing skills during my free time”[28] |

| Engaging Learning Experience | Realistic learning environment Lively, virtual patients Prompt feedback supports active learning More engaging than paper-based cases |

“One function that I find very cool is the feedback, which helps me have the ability to self-study and self-check whether the prescription I give to the patient is incorrect or not”[30] “I could observe patient appearance including their ages, gender and other special features such as pregnant women, so it helps me visualise better”[30] |

| Safe Learning Environment | Low-stakes learning environment without patient risk Ability to repeat exercises reinforces student learning |

“MyDispense is good because it gives us the experience and practice of realistic dispensing without having to place any risk on real patients in our community.”[16] “We can practice as many [times] as we want, as many times as we wish”[31] |

| Barrier theme(s) | Description of barrier theme(s) | Supporting Quotation |

| Learning curve | Complicated to learn initially User Interface (UI) can be complicated and difficult to navigate |

“I need more time to learn and explore with the program system and functions” [28] “A tutorial version of these cases where you learn as you go instead of after you finish the entire case may be helpful”[24] “Improvement of the design of the user interface of MyDispense for easier navigation and better appearance of the application for the user”[31] |

| IT issues | Software “bugs” and compatibility issues using certain web browsers Internet connection issues |

“Reloading of the website whenever the internet connection is slow … reforms the activity or exercise I am doing”[31] “Program system may not be quite stable”[28] “We had to use a certain web browser and it would become very confusing when trying to back out or submit medication”[21] |

| Limited realism and applications | Perceived limitations in physical fidelity Lack of oral communication features with patients and prescribers Simulation is restricted to community practice settings |

“It’s a bit robotic”[32] “There were some limitations in discussing with patients”[28] “A possible improvement is the option to be exposed to different kinds of pharmaceutical workplace settings, like the option to pick between settings like Hospital Pharmacy or Community Pharmacy”[31] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).