1. Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is increasingly being integrated into educational systems globally and has recently become a major discourse for educators, researchers and policy makers alike. This is driven by the rise and influx of AI tools, particularly as technologies such as intelligent tutoring systems, predictive analytics, and generative tools reshape learning environments, thus raising concerns about how to effectively integrate AI into the teaching and learning process. From previous years we have learned that the introduction of new technologies does not always guarantee improved learning outcomes if strategic adoption is not employed. Similarly integrating AI into education will not automatically yield benefits if not strategically and purposively done. And despite the advancements of AI in Education, challenges like the digital divide, ethical considerations, and teacher professional development remain. (Kamalov, et al.,2023; Semwaiko et al., 2024)

Therefore, the rapid rise of AI technologies and their use in education necessitates the reevaluation of traditional practices especially with regards to pedagogical innovations and digital transformation (Zang et al., 2023). For the benefits of AI to be realized there is a need for effective integration into education through strategic frameworks that align with education goals and ethical considerations (Zhav et al., 2021; Harry, 2023). With growing attention on the transformative potential of artificial intelligence (AI) in education, researchers (Allen & Kendeou, 2023; Xu & Ouyang, 2021; Tolentino et al., 2024; Celik, 2022; Phan, 2024; Riapina, 2023; Alotaibi, 2024; Zafari et al., 2022; Chee et al., 2024; Moya & Camacho, 2024; Song et al., 2024; UNESCO 2024; Lim 2024) have proposed various frameworks to guide ethical and pedagogically sound integration. Underscoring the importance of theoretical frameworks like constructivist learning theory and the TPACK framework for effective AI integration (Кazimova et al., 2025). These frameworks address teacher readiness, curriculum development, and infrastructure, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where adoption conditions vary widely (Cai et al., 2024). Zhai et al. (2021) suggested that challenges in education may arise due to the inappropriate use of AI techniques, changing roles of teachers and students, as well as social and ethical considerations. Thus, outlining a plan for integrating AI education is significant for setting educational direction (Lim, 2024).

This systemic review therefore examines literature from 2021 to 2025 on AI integration frameworks in education with the aim of synthesizing the state of knowledge on AI integration frameworks, particularly regarding ethical, pedagogical, and socio-technical considerations. The synthesis of how these frameworks support education outcomes was done and common themes were identified. This review summarizes the main findings and models of AI integration frameworks in education, assessing their suitability for LMIC settings. Finally, the EDAIL (Educators Artificial Intelligence Literacy) framework which builds on prior works to meet the needs in the low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) was discussed.

2. Methods

A comprehensive systematic review was conducted following PRISMA 2020 guidelines. Search was performed in Scopus, Web of Science, and ERIC databases for publications from 2021 to early 2025. Search terms combined variations of “AI”, “education”, “integration”, “framework”, “model”, and “literacy”. References lists of key papers and relevant policy reports were also manually screened. Studies were eligible if they:

Focused on AI integration in formal education (any level, K-12 to higher education).

Proposed or examined a framework/model for integrating AI into teaching, learning or education systems (including competency frameworks, implementation guidelines, or adoption models).

Were published 2021–2025 in peer-reviewed sources (including journals, conference proceedings, or officially published reports).

Included either conceptual analysis (theoretical frameworks, policy guidance)

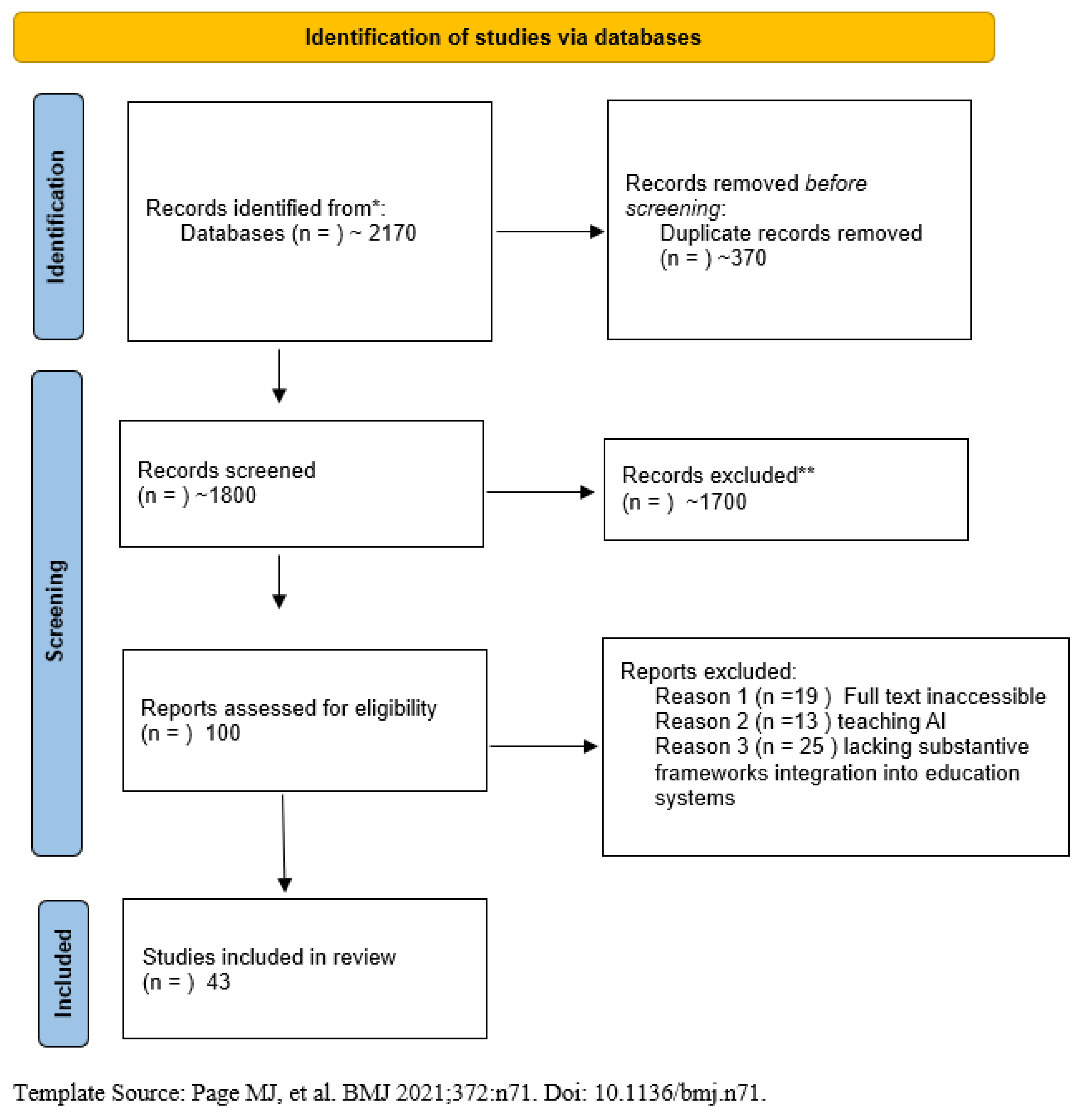

Figure 1 illustrates the study selection process in a PRISMA flow diagram. Excluded studies included those that were purely technical (e.g. developing an AI algorithm without discussion of educational integration), opinion pieces lacking substantive frameworks, or not available in English. Given our focus on integration frameworks, we also excluded research solely about teaching

AI as a subject (AI education for computer science students) unless it is explicitly connected to broader integration into education systems. After the removal of duplicates, titles/abstracts were screened for relevance, then the texts was read to determine inclusion.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Overview of Included Studies

A total of 43 publications that met our inclusion criteria were selected from reputable sources such as IEEE, Springer, Taylor & Francis, Elsevier, MDPI, and others. Inclusion criteria were peer-reviewed studies published between 2021 and 2025 addressing AI integration in formal educational settings. . Of these, ~30 publications presented conceptual or theoretical frameworks for AI integration (including policy guidelines and models), and ~13 sources included international agencies which published competency frameworks and strategy recommendations, as well as academic research articles and a few conference proceedings, a few were empirical studies evaluating AI interventions or teacher adoption in educational settings. The exclusion criteria were non-peer-reviewed documents, purely technical papers without pedagogical relevance, and articles unrelated to education. Due to lack of effect size data, a qualitative thematic synthesis was adopted.

A summary of the major AI integration frameworks that emerged was done, then additional themes and frameworks specific to LMIC contexts were highlighted. Due to lack of effect size data, a qualitative thematic synthesis was adopted.

3.2. Framework Types and Key Features

Multiple frameworks have been developed to guide the integration of artificial intelligence in education. A recurrent theme is that AI in education should be implemented in a human-centered, ethical, and pedagogically sound way. Most of these frameworks address K-12, higher education, and professional education, with tailored approaches for each context (Tolentino et al., 2024; Celik, 2022; Alotaibi, 2024; Zafari et al., 2022). The frameworks range from conceptual (complex adaptive systems, ED-AI Lit) to practical (Intelligent-TPACK, AI-LMS, curriculum models in medical education) (Xu & Ouyang, 2021; Allen & Kendeou, 2023; Tolentino et al., 2024; Celik, 2022; Alotaibi, 2024). Most frameworks emphasize the need for ethical considerations, teacher professional development, curriculum integration, and student engagement (Allen & Kendeou, 2023; Celik, 2022; Кazimova et al., 2025; Alotaibi, 2024). Common challenges include data privacy, algorithmic bias, equitable access, and the need for ongoing faculty training (Celik, 2022; Кazimova et al., 2025; Alotaibi, 2024).

Xu and Ouyang (2021) along with Allen and Kendeou (2023) have proposed foundational models for categorizing the functions of artificial intelligence in the field of education. Chee et al., (2024) created a comprehensive competency framework for AI literacy, focusing on essential competencies and sub-competencies for different learner groups. This ED-AI Lit framework includes six components: Knowledge, Evaluation, Collaboration, Contextualization, Autonomy, and Ethics. (Allen & Kendeou, 2023). Drawing on established theories from business communication and educational technology, Riapina, (2023) framework provides comprehensive guidance for designing engaging learning experiences. The framework is exemplified through various tasks, including role-playing with AI chatbots, analyzing nonverbal cues, communication simulations, interactive presentation assessments, and collaborative AI-supported projects. (Riapina, 2023). Alotaibi, (2024) review not only examines the technological integration but also evaluates how AI–LMS systems contribute to sustainable development in higher education through reduced resource consumption, improved accessibility, and enhanced educational equity. In the context of mobile learning (mLearning), it is crucial that research examines the pedagogically sound integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into mLearning environments. (Moya & Camacho, 2024). According to Song et al. (2024), artificial intelligence (AI) has become more prominent in children's lives, many researchers and practitioners emphasize the importance of integrating AI as learning content in K-12 education. They note that despite recent efforts in developing AI curricula and guiding frameworks, educational opportunities often do not provide equally engaging and inclusive learning experiences for all learners. Song et al. (2024) proposed a new framework to promote equality and equity in AI education. Similarly, Yim (2024) states that recent developments in age-appropriate AI learning tools have extended AI literacy to primary schools, but AI literacy frameworks for this age group remain underdeveloped. Thus, his study proposes a new inclusive AI literacy framework aimed at guiding policymakers and curriculum designers to implement holistic AI literacy education for young students. The key frameworks identified from these reviews are summarized in

Table 1, detailing their principal components.

Global AI Integration Frameworks (2021–2025)

Global frameworks, such as UNESCO’s competency guidelines and the OECD's AI Literacy Framework, emphasize ethical, human-centered AI usage in classrooms (UNESCO, 2024; OECD, 2025). These trends are mirrored and extended in LMIC-focused models, which incorporate accessibility, cultural relevance, and infrastructure considerations (Kathala & Palakurthi, 2025; Mah & Groß, 2024). The UNESCO AI Competency Framework for Teachers (UNESCO, 2024) outlines five key competency areas for teachers: (1) a human-centered mindset, (2) ethics of AI, (3) AI foundations and applications, (4) AI pedagogy, and (5) AI for professionals. An important point is that AI should complement, not replace, teachers; the framework emphasises teachers' irreplaceable role and the necessity to incorporate AI in ways that empower (rather than de-skill) educators. UNESCO recommends that countries include AI competences into their national strategies, invest in infrastructure and governance initiatives. For example, they emphasise the need of providing ubiquitous internet access and data privacy protections as preconditions. Overall, UNESCO's frameworks lay the groundwork for ethical AI literacy and capacity building in education, with an emphasis on equity and human oversight.

Another category of frameworks explores how educators may use AI tools into their teaching practices. Conceptual models like TPACK (Koehler & Mishra, 2006) and SAMR (Puentedura, 2013) have been repurposed to inform AI integration. Many researchers have leveraged these established educational technology frameworks to conceptualise AI integration ( Celik, 2022). TPACK (Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge) gives a lens into the interplay between a teacher's understanding of content, pedagogy, and technology, implying that effective integration occurs at the intersection of these domains. The SAMR paradigm (Substitution-Augmentation-Modification-Redefinition) covers many stages of technology adoption, ranging from direct substitution to revolutionary new activities. These models, which were initially designed for broad ed-tech integration, are being updated and enhanced for the AI age. Kohnke and Zou (2025) illustrate this in a TESOL setting by utilising TPACK to assure pedagogical alignment of AI tools and SAMR to assess the transformational influence of AI on language teaching tasks. They believe that instructors must address AI's sociopolitical, ethical, and cultural elements - for example, being mindful of biases in AI-generated feedback or uneven access - while using these technologies for automation and personalisation.

Aside from pedagogy-focused approaches, several frameworks emphasise AI readiness at the organisational and policy levels. For example, Yang, Zhang, Sun, et al. (2025) underscored the predominantly technology-driven nature of AI in education research, emphasizing the necessity for frameworks that consider institutional adoption factors and teacher acceptance. Riapina (2023) discusses practical considerations for implementation, including technological infrastructure, faculty training, ethics, curriculum integration, and assessment strategies.

4. Thematic Synthesis

A qualitative thematic synthesis of conceptual frameworks and case studies was conducted. Several recurring themes and best-practice recommendations emerged:

4.1. Pedagogical Alignment

A recurring theme across literature is the alignment of AI tools with sound pedagogical practices (Raiz & Mushtaq, 2024). Theoretical models such as TPACK and constructivist learning theory are frequently used to guide effective AI integration (Celik, 2022; Кazimova et al., 2025). Frameworks such as Intelligent-TPACK (Celik, 2022) and AI Literacy (ED-AI Lit) (Allen & Kendeou, 2023) stress that AI must support—not replace—evidence-based instructional strategies. Xu and Ouyang (2021) emphasized that AI's utility in education hinges on its integration with active learning, inquiry-based instruction, and personalized feedback loops. Thus, maintaining a balance between AI and human interaction in learning environments is recommended (Msambwa et al., 2025; AlAli, et al.,2024; Phan, 2024) These frameworks often adapt existing educational technology models like TPACK and SAMR to the context of AI-driven tools. AI enables tailored learning paths, adaptive assessments, and personalized feedback, improving student engagement, motivation, and academic performance (Cai et al., 2024; Alotaibi, 2024; Karan & Angadi, 2023; Msambwa et al., 2025).

4.2. Ethical and Responsible Use

The potential of AI in education has been examined, revealing significant possibilities. However, challenges persist, including ethical concerns related to data privacy, inherent biases within AI systems. (Alotaibi, 2024; Eden, et al.,2024), and the risk of over-reliance on automation, which impedes its widespread adoption. (Asy’ari & Sharov, 2024). Nearly all reviewed frameworks underscore the importance of ethical considerations, encompassing fairness, transparency, data privacy, and bias mitigation. Sytnyk and Podlinyayeva (2024) state that while AI in education offers data-driven insights, addressing ethical considerations, equity issues, and technical limitations is crucial for effective integration. The ED-AI Lit framework integrates these ethical dimensions as foundational to teacher and student AI literacy (Allen & Kendeou, 2023). Responsibility in design and deployment is seen as crucial for trust-building, especially in contexts where data protection laws may be limited (Eden, et al.,2024). Many frameworks call for establishing guidelines or “AI ethics committees” in education departments to vet AI tools and the need for enhanced accountability and transparency in AI applications (Wangdi, 2024). Data privacy, algorithmic bias, and ethical deployment of AI remain significant challenges, necessitating ongoing attention and the development of robust ethical frameworks (Alotaibi, 2024; Karan & Angadi, 2023b; Msambwa et al., 2025). The theme of human oversight is also strong: AI should augment human decision-making, not replace it blindly. This is especially important when AI is used for high-stakes tasks (like grading or student monitoring). By addressing these key aspects, educators can harness the full potential of AI while mitigating risks and ensuring equitable access to AI-driven educational resources.” (Sytnyk & Podlinyayeva, 2024)

4.3. Teacher Professional Development

Teacher readiness is consistently identified as a critical enabler of effective AI integration (Tolentino et al., 2024) and the need for faculty training were also identified. (Alotaibi, 2024). Frameworks emphasize not only technological competence but also pedagogical fluency in evaluating when and how AI tools can be used appropriately(Cai et al., 2024; Alotaibi, 2024; Karan & Angadi, 2023). The Intelligent-TPACK model proposes a merged knowledge base that combines AI understanding with subject-specific and instructional expertise (Celik, 2022). . If teachers lack understanding or confidence in AI, even the best tools will go unused or misused. Hence, frameworks (global and LMIC) insist on robust PD programs to improve teachers’ AI literacy (both technical and pedagogical) (UNESCO 2024). Teachers should learn not just how to operate AI tools, but when to appropriately integrate them into lesson plans, how to interpret AI outputs, and how to address students’ questions about AI. In LMICs, training often needs to start with basic digital skills and gradually introduce AI concepts. The reviewed literature suggests co-designing training with teachers (as done in with EDAIL model) to ensure relevance. The ED-AI Lit framework stresses the importance of developing a deep understanding of how AI systems function, critically evaluating their implications, and fostering collaborative relationships between individuals and AI. (Allen & Kendeou, 2023)

4.4. Infrastructure and Accessibility

Infrastructure was repeatedly cited as both a constraint and a determinant of success in AI integration, particularly in LMIC discussions, the basic issue of access is a theme (Yılmaz, 2024). Tolentino et al. (2024) highlights the importance of cloud-based platforms, affordable hardware, and mobile-friendly applications. Frameworks that fail to consider these realities risk exacerbating digital divides (Yılmaz, 2024). Frameworks often include an assessment of a school’s or region’s digital infrastructure readiness (hardware, connectivity, power, etc.) as a prerequisite for AI integration. (Tolentino et al., 2024) Many LMIC-targeted models propose scalable solutions noting that without equitable access, AI integration can exacerbate educational inequalities, a point raised in multiple studies and policy briefs (Karan & Angadi, 2023b; UNESCO, 2024). Thus, a “framework” in these contexts sometimes includes a staged plan for infrastructure upgrades or leveraging existing ubiquitous tech (e.g. using AI on smartphones since they are more common than computers in some countries). Ensuring equitable access to AI-powered tools and addressing the digital divide are critical for maximizing the benefits of AI in education(Alotaibi, 2024; Fu et al., 2024; Karan & Angadi, 2023b).

4.5. Curriculum and Content Integration

There is an emphasis on embedding AI-related activities into the curriculum in an interdisciplinary way (Almasri,2024). Frameworks such as ED-AI Lit advocate culturally responsive pedagogy and inclusive language design (Allen & Kendeou, 2023). Cai et al. (2024) further propose the customization of AI-driven content to align with local curriculum standards and cultural narratives. While Riaz, & Mushtaq (2024) focuses on technology acceptability, and material customization.

Thematic analysis also shows a split between two approaches: “Teaching with AI” (using AI to enhance how existing subjects are taught) versus “Teaching about AI” (imparting knowledge of AI itself). The consensus is that both are needed. Students should use AI as a learning aid but also be taught about the AI – how it works and its implications – to become informed citizens (Ejjami, 2024). AI chatbots and conversational agents are effective for content and language integrated learning, providing interactive and culturally relevant educational experiences(Mageira et al., 2022).

4.6. Contextual Relevance in LMICs

Only a subset of the literature explicitly addresses LMIC contexts. Cai et al. (2024) identify unique challenges such as infrastructural instability, limited digital literacy, and language diversity. The need for low-bandwidth, locally relevant AI tools is clear. Xu and Ouyang (2021) also note that AI policies developed in high-income countries often fail to translate into scalable solutions for low-resource settings. Another common theme is the need to bolster AI literacy and teacher training in developing regions. Kathala & Palakurthi (2025) proposed a comprehensive AI Literacy Framework for Developing Nations, unveiled at an international conference. They identify that many developing nations struggle with “limited infrastructure, insufficient educational resources, and gaps in policy frameworks”, which hinder adoption of AI in schools. Their framework calls for integrating AI literacy into curricula, training educators, and forging public-private partnerships to bridge the AI divide between developed and developing countries. In essence, it’s not enough to introduce AI tools; LMICs must simultaneously invest in upskilling teachers (so they can use AI effectively) and ensure local relevance (AI that works in low-resource classrooms, multilingual settings, etc.)(Karen et al., 2023). This resonates with UNESCO’s emphasis that digital inequities must be addressed – otherwise AI may widen gaps. For example, UNESCO’s 2024 frameworks stress inclusion and cultural context. Culturally responsive AI in education was highlighted as an emerging necessity: AI should respect and include local knowledge and not inadvertently propagate a one-size-fits-all approach to learning. Encouraging collaboration between governments, universities, and startups in LMICs to develop AI tools tailored to local needs.

The consensus in the literature is that contextualization is key (Karen et al., 2023). Frameworks developed in high-income contexts must be adapted to local curricula, languages, and cultural values in LMICs. Furthermore, ethical AI use is a universal concern but takes on specific nuances in LMICs – for instance, ensuring AI does not sideline indigenous knowledge, and that data used by AI is handled securely in countries without strong privacy laws. Recognizing this, some LMIC-oriented frameworks explicitly include community stakeholders in designing AI interventions (a participatory approach) and emphasize low-cost, offline AI solutions (given unreliable internet).

By synthesizing these themes, we see that AI integration frameworks, whether global or LMIC-specific, are multi-faceted. They are not just technical blueprints but cover people, practices, and policies. This holistic approach – combining infrastructure, skills, pedagogical strategies, and governance – is considered essential for sustainable integration.

5. The EDAIL Framework

The Educators’ Artificial Intelligence Literacy (EDAIL) framework responds to the gaps identified in earlier models by centering teachers in LMICs. The framework builds on the insights of these existing models by focusing on teacher agency, ethical awareness, and pedagogical purpose in AI use. It emphasizes four core domains: What (foundational AI knowledge), Why (pedagogical purpose), How (instructional integration), and When (appropriate use). EDAIL guides teachers in LMICs through meaningful AI integration, it exemplifies a bottom-up model for context-aware AI integration. EDAIL unique emphasis on timing and ethical implementation expands upon prior frameworks by translating abstract principles into actionable steps.

EDAIL’s design centers on the

“What, Why, When, How” of AI integration in pedagogy.

Table 2 outlines the core dimensions of the framework, along with the specific criteria that provide clarity and guidance for educators. By addressing “What,” “Why,” “When,” and “How,” the EDAIL framework equips teachers with actionable insights to effectively and ethically incorporate AI into their teaching practices.

WHAT: Helping teachers understand what AI is (core concepts and tools) and what it can and cannot do in an educational context. This demystifies AI, grounding it in concrete classroom applications rather than abstract hype. It builds on global AI literacy frameworks but translates them into terms and examples accessible to teachers (e.g. explaining an AI tool like a language model in simple language and subject-specific examples).

WHY: EDAIL’s most distinctive emphasis is on the purpose – ensuring teachers ask, “Why am I using this AI tool?” before adoption. This echoes the human-centered mindset from UNESCO (2024) and the calls for pedagogy-first integration. EDAIL stresses that AI should serve clear educational goals (such as enhancing learning experiences, enabling differentiated instruction, providing timely feedback, or easing administrative load). By articulating the “why”, teachers avoid using AI just because it’s trendy; instead, usage is tied to improving outcomes or efficiency in specific ways. This focus on purpose-before-tech extends prior frameworks by making explicit the reflective practice that teachers in LMIC (and everywhere) should engage in. It resonates with the principle of “pedagogy leads, technology follows” found in earlier ed-tech models.

HOW: EDAIL provides guidance on how to integrate AI tools effectively into teaching practice. This includes pedagogical strategies (e.g. how to use an AI tutor in a lesson plan, how to interpret AI analytics dashboards for student data) and management issues (classroom management when students use AI, addressing academic integrity concerns, etc.). In doing so, it builds on frameworks like TPACK/SAMR by offering concrete integration examples at different levels. For instance, an EDAIL guide might show how a biology teacher can use an AI simulation (technology) to enhance inquiry-based learning (pedagogy) about photosynthesis (content), aligning with TPACK intersections and aiming for a modification/redefinition level in SAMR. It also incorporates ethical how-tos (e.g. how to check AI outputs for bias, how to explain AI’s limitations to students), extending responsible AI use principles into actionable classroom routines. Essentially, EDAIL bridges high-level framework ideals with practical steps and lesson designs that teachers can implement.

WHEN: Another novel aspect is discussing when the optimal time and scope is, to introduce AI – both in a teacher’s workflow and in student learning progressions. This acknowledges that timing can impact effectiveness: for example, when in a learning unit AI tools should be used (perhaps after students have some foundational knowledge, AI can help with practice and extension)? Or when should teachers rely on AI vs. human intervention (maybe using AI for initial feedback but a teacher for deeper guidance)? By addressing “when,” EDAIL extends prior models that often focused on static competencies, adding a dynamic dimension of sequencing and appropriateness. This is particularly relevant in LMIC contexts where teacher bandwidth is limited – knowing when not to use AI (to avoid overload or misuse) is as important as knowing when to use it.

Moreover, EDAIL situates itself in the LMIC reality by emphasizing resource-sharing and community. It encourages teacher communities to share AI integration experiences, localize content, and support one another (creating a peer network similar to existing ICT teacher communities, but focused on AI). It also explicitly calls for low-cost solutions and open-source AI tools to mitigate the cost barriers for schools – a practical extension beyond frameworks that assume availability of latest technologies. In doing so, EDAIL extends global frameworks like UNESCO’s by adding concrete tactics for implementation in low-resource schools, from offline AI packages to creative reuse of available tech (like using simple SMS-based AI tutors where smartphones aren’t available).

Finally, EDAIL’s development process – a co-creation lab with teachers – is itself a methodological extension of prior top-down frameworks. It embodies a bottom-up approach, ensuring the framework is informed by teachers’ real challenges and insights. This addresses a critique that some global frameworks, while excellent on paper, may not fully resonate with on-the-ground needs of teachers in, say, a rural African classroom. EDAIL, being co-designed with those educators, serves as a translation of high-level principles into the local pedagogical language of teachers. That ethos, championed by EDAIL, encapsulates how it builds on previous frameworks’ call for purposeful, ethical integration and pushes it into practical, teacher-led action in LMIC contexts.

6. Conclusion

This review illustrates that while many AI integration frameworks exist, few are tailored to the specific constraints and opportunities of LMICs. The EDAIL framework advances the field by translating high-level principles into actionable strategies for teachers working in resource-constrained environments. The EDAIL framework exemplifies the next generation of integration models: it synthesizes the best global practices and local insights, giving educators a structured yet flexible roadmap to navigate the AI revolution with purpose and confidence. By building on prior frameworks and tailoring them to context, EDAIL and similar initiatives aim to ensure that AI in education truly becomes a tool for inclusive innovation – enhancing teaching and learning for all, rather than a few, and doing so in a way that is pedagogically sound and ethically grounded. AI integration in education requires frameworks that are not only ethically sound and pedagogically grounded but also adaptable to diverse global contexts, with EDAIL emerging as a practical and scalable model for LMICs by offering an actionable model suited to diverse global and resource-constrained contexts. Future research should focus on validating such frameworks across varied education systems and exploring long-term learning impacts

A full draft of the AI Literacy framework with its accompany toolkit will be released. This will be made available to educators, policymakers and the broader community to use and give their feedback. This consultation process will ensure the framework delivers the most relevant and helpful competencies while meeting the needs of diverse educational systems. The final version will be released in 2026 and will include high-quality examples. This will give educators immediate, actionable steps to integrate AI literacy into their teaching practices.

References

- AlAli, R., Wardat, Y., Al-Saud, K., & Alhayek, K. A. (2024). Generative AI in Education: Best practices for Successful implementation. International Journal of Religion, 5(9), 1016–1025. [CrossRef]

- Allen, L. K., & Kendeou, P. (2023). ED-AI LIt: An Interdisciplinary Framework for AI Literacy in Education. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 11(1), 3–10. [CrossRef]

- Almasri, F. (2024). Exploring the Impact of Artificial intelligence in teaching and learning of Science: A Systematic Review of Empirical research. Research in Science Education, 54(5), 977–997. [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, N. S. (2024). The impact of AI and LMS integration on the future of higher Education: Opportunities, challenges, and strategies for transformation. Sustainability, 16(23), 10357. [CrossRef]

- Asy’ari, M., & Sharov, S. (2024). Transforming Education with ChatGPT: Advancing Personalized Learning, Accessibility, and Ethical AI Integration. International Journal of Essential Competencies in Education, 3(2), 119–157. [CrossRef]

- Cai, L., Msafiri, M. M., & Kangwa, D. (2024). Exploring the impact of integrating AI tools in higher education using the Zone of Proximal Development. Education and Information Technologies. [CrossRef]

- Celik, I. (2022). Towards Intelligent-TPACK: An empirical study on teachers’ professional knowledge to ethically integrate artificial intelligence (AI)-based tools into education. Computers in Human Behavior, 138, 107468. [CrossRef]

- Chee, H., Ahn, S., & Lee, J. (2024). A competency framework for AI literacy: variations by different learner groups and an implied learning pathway. British Journal of Educational Technology. [CrossRef]

- Chiu, T. K., Xia, Q., Zhou, X., Chai, C. S., & Cheng, M. (2022). Systematic literature reviews on opportunities, challenges, and future research recommendations of artificial intelligence in education. Computers and Education Artificial Intelligence, 4, 100118. [CrossRef]

- Eden, N. C. A., Chisom, N. O. N., & Adeniyi, N. I. S. (2024). Integrating AI in education: Opportunities, challenges, and ethical considerations. Magna Scientia Advanced Research and Reviews, 10(2), 006–013. [CrossRef]

- Ejjami, R. (2024). The Future of Learning: AI-Based Curriculum development. International Journal for Multidisciplinary Research, 6(4). [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y., Weng, Z., & Wang, J. (2024). Examining AI use in Educational contexts: A Scoping Meta-Review and Bibliometric analysis. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education. [CrossRef]

- Harry, A. (2023). Role of AI in Education. Interdisciplinary Journal and Humanity, 2(3), 260-268. [CrossRef]

- Kamalov, F., Santandreu Calonge, D., & Gurrib, I. (2023). New Era of Artificial Intelligence in Education: Towards a Sustainable Multifaceted Revolution. Sustainability, 15(16), 12451. [CrossRef]

- Karan, B., & Angadi, G. R. (2023a). Artificial Intelligence Integration into School Education: A Review of Indian and Foreign Perspectives. Millennial Asia. 16(1), 173-199. [CrossRef]

- Karan, B., & Angadi, G. R. (2023b). Potential Risks of Artificial Intelligence Integration into School Education: A Systematic Review. Bulletin of Science Technology & Society, 43(3–4), 67–85. [CrossRef]

- Kathala, K. R and Palakurthi S. 2025. AI Literacy Framework and Strategies for Implementation in Developing Nations. In Proceedings of the 2024 16th International Conference on Education Technology and Computers (ICETC '24). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 418–422. [CrossRef]

- Кazimova, D., Tazhigulova, G., Shraimanova, G., Zatyneyko, A., & Sharzadin, A. (2025). Transforming University Education with AI: A Systematic Review of Technologies, Applications, and Implications. International Journal of Engineering Pedagogy (iJEP), 15(1), 4–24. [CrossRef]

- Kohnke, L., & Zou, D. (2025). Artificial Intelligence Integration in TESOL Teacher Education: Promoting a Critical Lens guided by TPACK and SAMR. TESOL Quarterly. [CrossRef]

- Lim, M. (2024). Developing a framework for the integration of artificial intelligence in technology education. Tehnički Glasnik, 18(2), 229–233. [CrossRef]

- Mageira, K., Pittou, D., Papasalouros, A., Kotis, K., Zangogianni, P., & Daradoumis, A. (2022). Educational AI Chatbots for Content and Language Integrated Learning. Applied Sciences, 12(7), 3239. [CrossRef]

- Mah, DK., & Groß, N. (2024) Artificial intelligence in higher education: exploring faculty use, self-efficacy, distinct profiles, and professional development needs. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education. 21(58). [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017–1054. [CrossRef]

- Moya, S., & Camacho, M. (2024). Leveraging AI-powered mobile learning: A pedagogically informed framework. Computers and Education Artificial Intelligence, 7, 100276. [CrossRef]

- Msambwa, M. M., Wen, Z., & Daniel, K. (2025). The impact of AI on the personal and collaborative learning environments in higher education. European Journal of Education, 60(1). [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2025). AI literacy for youth: Policy paper. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

- Phan, T. A. (2024). AI Integration for Communication Skills: A Conceptual Framework in Education and Business. Business and Professional Communication Quarterly, 0(0). [CrossRef]

- Puentedura, R. R. (2013). SAMR: Getting to transformation. Retrieved from http://www.hippasus.com/rrpweblog/archives/2013/04/16/SAMRGettingToTransformation.pdf.

- Riapina, N. (2023). Teaching AI-Enabled Business Communication in Higher Education: A Practical framework. Business and Professional Communication Quarterly, 87(3), 511–521. [CrossRef]

- Riaz, S., & Mushtaq, A. (2024). Optimizing Generative AI integration in Higher Education: A framework for enhanced student engagement and learning outcomes. 2022 Advances in Science and Engineering Technology International Conferences (ASET), 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Semwaiko, G. S., Chao, W., & Yang, C. (2024). Transforming K-12 education: A systematic review of AI integration. International Journal of Educational Technology and Learning, 17(2), 43–63. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y., Weisberg, L. R., Zhang, S., Tian, X., Boyer, K. E., & Israel, M. (2024). A framework for inclusive AI learning design for diverse learners. Computers and Education Artificial Intelligence, 6, 100212. [CrossRef]

- Sytnyk, L., & Podlinyayeva, O. (2024). AI in education: main possibilities and challenges. InterConf, 45(201), 569–579. [CrossRef]

- Tolentino R, Baradaran A, Gore G, Pluye P, Abbasgholizadeh-Rahimi S. (2024). Curriculum Frameworks and Educational Programs in AI for Medical Students, Residents, and Practicing Physicians: Scoping Review. JMIR Medical Education 10:e54793 . [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2024). AI competency framework for teachers. (2024). In United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (UNESCO) eBooks. [CrossRef]

- Wangdi, P. (2024). Integrating Artificial Intelligence in education: International Journal on Research in STEM Education, 6(2), 50–60. [CrossRef]

- Xu, W., & Ouyang, F. (2021). A systematic review of AI role in the educational system based on a proposed conceptual framework. Education and Information Technologies, 27(3), 4195–4223. [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, Ö. (2024). Personalised learning and artificial intelligence in science education: current state and future perspectives. Educational Technology Quarterly, 2024(3), 255–274. [CrossRef]

- Yim, I. H. Y. (2024). A Critical Review of Teaching and Learning Artificial intelligence (AI) Literacy: Developing an intelligence-based AI literacy Framework for Primary school education. Computers and Education Artificial Intelligence, 100319. [CrossRef]

- Zafari, M., Bazargani, J. S., Sadeghi-Niaraki, A., & Choi, S. (2022). Artificial Intelligence Applications in K-12 Education: A Systematic Literature review. IEEE Access, 10, 61905–61921. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).