1. Introduction

Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) and fatigue can be a pervasive multifactorial problem in the intensive care unit (ICU) [

1]. It is well acknowledged that critical illness and stays in the ICU have significant impact on sleep [

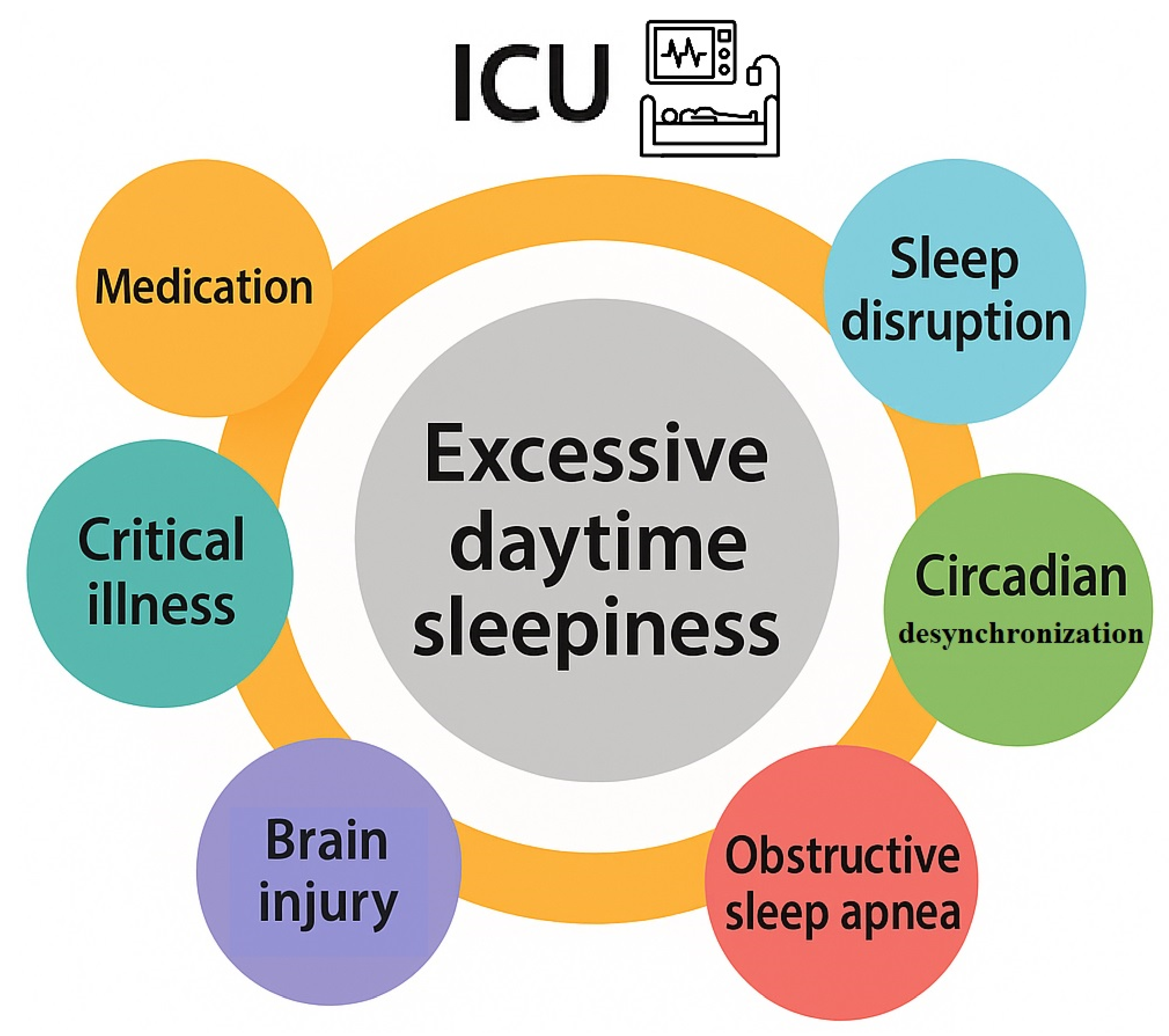

2]. In this clinical setting the common causes of EDS could include: (i) inadequate quantity or fragmentation of sleep due to the underlying pathology, critical illness, pain or the effect of light and noise in the ICU environment (ii) sleep-disordered breathing e.g., obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), induced or exacerbated during critical illness or recovery (iii)desynchronization of the circadian pacemaker in the ICU environment(v)anaesthetic and opioid treatment that increase the risk of OSA and sleepiness(vi) traumatic and non-traumatic brain injury (TBI) or mental disorders as major depressive disorder developing during or after intensive care [

1,

2].

Modafinil is a unique oral agent that is used to treat excessive daytime sleepiness [

3]. This wakefulness-promoting medication been approved by the US FDA to treat EDS associated with narcolepsy, residual EDS in OSA despite optimal treatment with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), and excessive sleepiness associated with shift work sleep disorder [

4]. The exact mechanism of action of modafinil remains unclear. However, previous research shows that modafinil possesses not only wake-promoting properties, but also associated neuroprotective and antioxidative effects [

3]. Thus, modafinil could represent an attractive pharmacological candidate to address EDS in the ICU. The present narrative review summarizes the available data concerning the administration of modafinil for the treatment of EDS and fatigue in critical care patients.

2. EDS in Critically Ill Patients

EDS can be defined as the inability to maintain wakefulness and alertness during the day, leading to unintended lapses into sleep. EDS is frequently observed in critically ill patients and represents a significant barrier to recovery in the ICU. In critically ill populations, EDS is multifactorial in origin, resulting from a complex interplay of disrupted sleep patterns, sedative medication effects, systemic inflammation, neurological dysfunction, and environmental factors [

5,

6]. Importantly, EDS in ICU patients is not only a symptom but may also serve as a marker of sleep deprivation, delirium, or underlying neurological dysfunction. Its presence can delay mobilization, affect participation in physical therapy, and prolong ICU and hospital stay [

5].

Figure 1 summarizes the contributory factors of excessive daytime sleepiness in the ICU.

Given these challenges, there is growing interest in interventions to improve sleep and reduce EDS. Identifying and managing EDS may play a vital role in improving both short- and long-term outcomes. Comprehensive management of EDS requires a multifaceted approach, including pharmacological and non-pharmacologic strategies. Non pharmacological measures, such as optimizing sedation protocols, promoting sleep hygiene with noise reduction and light therapy should be considered [

7]. Pharmacologic approaches, including agents like modafinil, have been explored but require further investigation to establish their safety and efficacy in the critically ill [

1,

2].

2.1. Sleep Disruption and Circadian Desynchronization in the ICU

Sleep disruption arising from environmental disturbances is a primary contributor to EDS in the ICU. Continuous lighting, frequent nursing interventions, alarms, and mechanical ventilation interfere with both sleep initiation and maintenance. The levels of noise in the ICU environment commonly exceed recommended thresholds [

8]. Poor sleep efficiency, and prolonged sleep onset (sleep latency) are commonly present. These brief sleep periods of ICU patients are interrupted by frequent arousals and are evenly distributed over the day and night [

1,

2]. Sleep architecture is significantly altered. Sleep in critically ill patients is characterized by reductions in restorative slow-wave and REM sleep, while being dominated by lighter stages (N1 and N2) [

9]. These alterations contribute to prolonged fatigue and impaired neurocognitive recovery and they often persist beyond ICU discharge [

1,

2]. Moreover, the acute stress response and systemic inflammation associated with critical illness may further disrupt sleep-wake regulation, possibly through dysregulation of cytokines like interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, which are known to affect sleep architecture [

10]. Finally, the constant exposure to artificial light and lack of temporal cues may lead to the loss of circadian rhythm and exacerbate sleep fragmentation. In critical care settings, desynchronization of melatonin secretion and disruption of the circadian cycle are common, impacting patients' health and recovery [

11,

12].

2.2. OSA in the ICU

Excessive daytime sleepiness is the most common symptom of OSA. OSA in critically ill patients is often underdiagnosed and may be pre-existing or newly recognized during ICU admission. In any case, OSA has the potential to complicate recovery and weaning from ventilation [

1,

2]. OSA in the ICU can be precipitated by a series combination of anatomical, physiological, and treatment-related factors. The anatomical characteristics that predispose to OSA amplify their effect to upper airway narrowing and collapsibility during sedation and sleep [

13]. Obesity, in particular, is highly prevalent in ICU populations [

14]. Pre-existing conditions such as obesity hypoventilation syndrome prior to ICU admission may further predispose patients to more severe EDS during their critical illness. Mechanical ventilation and post-extubation effects also play a role. First of all, sedative medications commonly used in the ICU, including benzodiazepines, propofol, and opioids, further exacerbate airway obstruction. These agents decrease the muscle tone in the upper airway rendering even mild anatomical abnormalities more likely to result in obstruction [

15]. Besides impairing the normal reflexes that keep the airway open during inspiration, sedatives also lead to blunting arousal responses to hypoxia or hypercapnia. Moreover, supine positioning, often necessary in critically ill patients, favors gravitational collapse of the upper airway, especially in obese individuals or those with neuromuscular weakness [

1,

2]. Additionally, prolonged mechanical ventilation may lead to alterations that increase risk of OSA-like events after extubation [

16]. In particular, upper airway muscle deconditioning or trauma, may result in laryngeal edema or vocal cord dysfunction that increases airway resistance [

17]. Finally, a rostral fluid displacement is possible in critically ill patients contributing to peripharyngeal edema and increased upper airway resistance [

18].

2.3. Critical Illness and Underlying Disease

EDS represents a common and often persistent complication following acute brain injury in critically ill patients, including those with traumatic brain injury (TBI), stroke, subarachnoid hemorrhage, or hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. In these patients the pathophysiology of EDS multifactorial, but injury to key brain regions involved in sleep-wake regulation plays a central role [

19,

20]. However, even in critically ill patients without acute brain injury, systemic inflammation and critical illness-related brain dysfunction also contribute to EDS [

1,

2]. In conditions such as sepsis, delirium, and encephalopathy brain regions responsible for wakefulness can be affected, further promoting hypersomnolence. For example, elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1 (IL-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) may disrupt neurotransmission and affect the hypothalamic centers that control arousal and sleep [

10]. Likewise, impaired circadian melatonin secretion in septic patients is mainly related to the presence of severe sepsis and/or concomitant medication [

21]. Importantly, inflammation and critical illness-related neuromuscular dysfunction may compromise central regulation of breathing and further impair the tone of the pharyngeal dilator muscles, particularly during sleep [

22]. ICU-acquired weakness and prolonged immobility also play significant indirect roles leading to physical deconditioning and fatigue [

22].

2.4. Medication and EDS in the ICU

Pharmacological agents used in ICU management also play a significant role to EDS, by disrupting normal sleep architecture or exerting residual sedative effects that impair daytime alertness [

1,

2]. Most drugs with clinical sedative or hypnotic actions affect one or more of the central neurotransmitters implicated in the neuromodulation of sleep and wakefulness. Yet, numerous non sedative drugs can impair normal sleep architecture [

23]. Polypharmacy, drug accumulation due to organ dysfunction, and prolonged drug half-lives in critically ill patients further heighten these risks [

23]. Sedative-hypnotics, such as benzodiazepines and propofol, are significant contributors to EDS. These drugs, can reduce slow-wave and REM sleep—the most restorative stages—resulting in non-restorative sleep and persistent somnolence [

8]. While sedation induces a non-physiologic sleep-like state, this is often restorative rest, leading to residual sleepiness during waking hours [

9]. Additionally, prolonged sedation may impair the reestablishment of normal wakefulness and circadian rhythm once sedation is weaned. Similarly, opioids administered for pain control also interfere with sleep continuity and decrease REM sleep [

23]. Moreover, these drugs also depresse respiratory drive and may exacerbate sleep-disordered breathing leading to fragmented sleep patterns [

24]. Finally, antipsychotics, often used to manage ICU delirium, can induce sedation and worsen EDS, particularly those with strong antihistaminergic effects like quetiapine [

23].

3. Pharmacological Properties of Modafinil

3.1. Mechanism of Action

Modafinil and its R entaniomer, armodafinil, are nonamphetamine wakefulness-promoting medications that are considered to be the first-line medication for treatment of EDS associated with narcolepsy [

3]. Residual EDS in OSA and excessive sleepiness associated shift work sleep disorder have also been shown to respond to modafinil [

4]. The drug MD enhances function in a number of cognitive domains and has also been used, off label, as cognitive enhancer in healthy populations or patients with impaired cognitive function. The mechanism of action of this agent is still unclear [

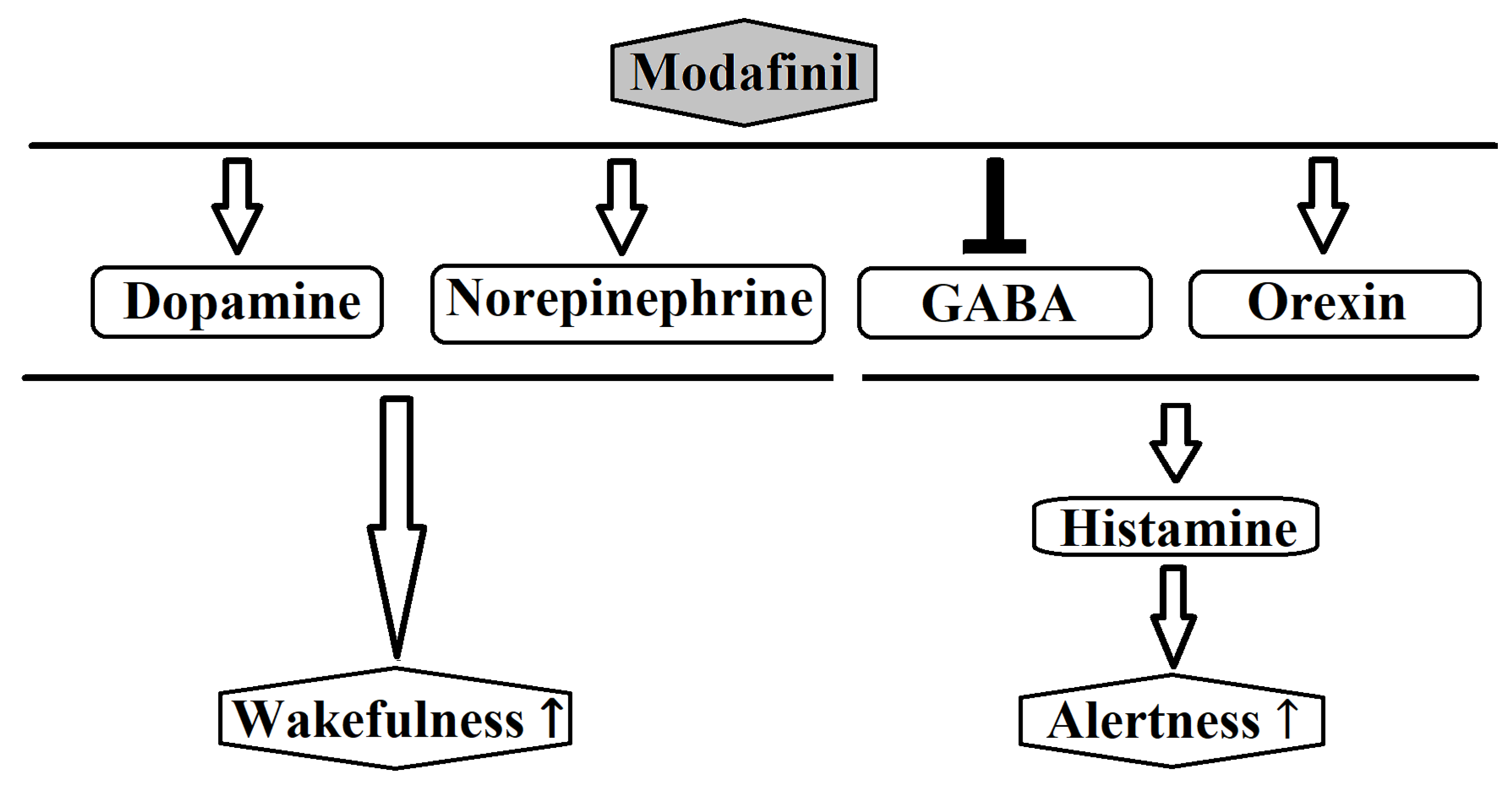

4]. Most likely, modafinil acts by enhancing nor-epinephrine (NE) and dopaminergic transmission of many brain sites associated with wakefulness [

3,

4]. Previous research showed that modafinil promotes the activity of various wake-promoting centers including the tuberomammillary nucleus (TMN) and hypocretin cells of the perifornical area [

25]. These centers receive dopaminergic innervations and modafinil may increase dopaminergic signaling by altering the dopamine reuptake [

26,

27]. Modafinil binds weakly to the dopamine transporter (DAT) and it has been reported the drug does not improve wakefulness in mice lacking the DAT [

26]. Furthermore, modafinil may inhibit the activity of ventrolateral preoptic nucleus (VLPO) by blocking the reuptake of NE bynoradrenergic neural terminals in the VLPO [

27]. The mechanism of action of modafinil is distinct from classical psychostimulants in terms of the involvement of the histaminergic and the orexinergic systems. Modafinil activates indirectly the histaminergic system, presumably via attenuation of the inhibitory GABAergic input to the histaminergic neurons [

3,

28]. Moreover, evidence shows that modafinil increases histaminergic tone via orexinergic neurons [

3]. Finally, it has been reported that modafinil possesses anti-oxidative properties and could protect the striatum against protein oxidative damageand hinder the sleep-promoting effects of free radicals [

3].

Figure 2 schematically depicts the major neurochemical pathways affected by modafinil.

3.2. Pharmacokinetics and Dosing

Modafinil is a racemic mixture containing both L and R enantiomers with half-lives of 3–4 hr and 10–14 hr respectively [

4,

29]. The absorption of the drug is quite fastand peak plasma concentrationsoccur at 2–4 hafter administration.Usually modafinil is administered orally once daily in the morning (200–400 mg). The maximum recommended daily dose of modafinil is 400 mg [

30]. However, higher doses may be required for the adequate control of sleepiness [

31]. Since, the elimination half-life of modafinil is 9 to 14 hours once-daily administration is sufficient for most patients. Yet, in a sub-group of patients poor control of daytime sleepiness may be noticed in the afternoon or early evening. In this case asplit dosing (200 mg in AM, 200 mg at 1–2 PM) may be effective [

30,

31].

3.3. Side Effects and Drug Interactions

Headaches and nausea are the most common side-effects of modafinil. Headache can be managed with simple analgesics or minimized by a slow increase in dose [

4,

32]. Other mild side-effects that have been described include dizziness, diarrhea, dry mouth, nose and throat congestion, back pain, insomnia, and mental sideeffects like anxiety and nervousness [

32]. In rare cases, modafinil can cause serious side effects such as a severe skin rash (Stevens-Johnson syndrome) or psychiatric symptoms like hallucinations and mania. The evidence shows that modafinil exhibits no or limited tolerance and when discontinued a rebound of REM and slow wave sleep is unlikely [

33]. The metabolism of the drug depends mainly on the hepatic cytochrome P-450 (CYP450) system [

4]. Moreover, modafinil is also potent to suppress various and number of cytochrome isoenzymes. Thus, a number of drug interactions may occur. For example, co-administration of modafinil may increase the circulating levels of diazepam, phenytoin and propranolol [

4,

32]. Drug interactions with oral contraceptives should also be considered [

32]. In some cases, an adjustment of the drugs’ dosages may be required.

4. Administration of Modafinil in Critically Ill Patients

As mentioned above, the course of a patient in the ICU may be complicated by fatigue and EDS due to environmental factors, critical illness, mental complications and drugs adverse effects that result in cognitive and muscle dysfunction, sleep deprivation and fragmentation and sleep-disordered breathing [

1,

2]. Modafinil has a very attractive drug profile as a wake-promoting agent in this patient population. Reasons for this include the convenience of the medication regime, the documented efficacy and safety in other subsets of patients with EDS and the low potential for abuse, dependence or severe drug interactions [

3,

4]. In comparison to other stimulants, such as amphetamines,modafinil does not seem to interfere with normal nighttime sleep and is not associated with extreme behavioral excitation or rebound hypersomnolence [

34,

35].

Modafinil has been shown to reduce EDS and fatigue in various patient populations including patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [

36], multiple sclerosis [

37], nonmalignant or malignant pain requiring opioids [

38,

39] and depression [

40,

41]. Modafinil has also been shown to improve patient-reported fatigue in perioperative situations [

42,

43]. OSA is common in patients admitted to the ICU and perioperative procedures and critical illness seem to predispose to OSA [

2]. In patients with OSA treated with CPAP, modafinil has been shown to be efficacious in improving residual EDS, performance and quality of life [

44]. Yet, limited data exist investigating the role of modafinil in the treatment of EDS in the ICU. Indeed, to date few randomized controlled trials (RCT) have examined the effects of modafinil in critically ill populations.

For the present narrative review, an online search was conducted for modafinil studies as a stimulant for critically ill patients. Patients received modafinil primarily to promote ICU wakefulness. The search was performed on Embase, MEDLINE, Web of Science, and Google Scholar until May 20, 2025. The reference lists of articles were scanned. Studies that included the administration of modafinil for other indications or in other clinical settings were excluded. For the narrative review, 10 relevant studies were identified. These included 3 RCTs, 2 case series and 5 retrospective studies. Four of these studies included TBI or post-stroke patients, while the rest comprised mixed ICU populations. The characteristics of the included studies are summarized in

Table 1.

4.1. Mixed ICU Populations

In 2015, Gajewski et al reported a case series of three critically patients which received modafinil during their stay in a Thoracic Surgery ICU [

45]. The patients’ selection was based on the hypothesis that their clinical course was complicated by the presence of fatigue, EDS, and/or depression and that modafinil administration could promote the patients’ wakefulness and participation. Hence, 200 mg of modafinil were administered orally each morning and according to the authors the patients responded with a marked improvement of alertness, activeness and participation to physical therapy during the following days. An improved sleep regulation was also noticed. In a second more recent case series with 8 critically ill patients (including COVID-19 patients) requiring mechanical ventilation, modafinil was administered to promote ICU wakefulness. Modafinil in a daily dose of 100–200 mg for a median duration of 4 days led to a GCS improvement in 5 (62.5%) patients. Furthermore, modafinil prevented tracheostomy in 1 COVID-19 patient. No significant adverse effects were documented [

46].

A retrospective cohort study by Mo et al studied the effect of modafinil on the alertness cognitive function of critically ill patients [

47]. The study included 60 ICU patients requiring ventilatory support , either invasive or noninvasive, at the time of modafinil initiation. The patients received an average daily modafinil dose of 170 mg for a median duration of 9 days and the average scores of the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) and Riker Sedation-Agitation Scale (SAS), were recorded during 48 hours before and after the start of modafinil therapy. According to the results, after controlling for possible confounding factors, modafinil treatment was associated with small, but non-significant increase in average scores of GCS by 0.34 points. Most importantly no modafinil-related side effects were detected. Modafinil administration was not associated with a significant change of the average SAS scores. The administration of modafinil in ICU patients appears to be safe and most of the studies report a low frequency of adverse events. Nevertheless, a retrospective chart study [

48] reported that critically ill patients who received modafinil were characterized by increased duration of delirium, length of hospital stay and mechanical ventilation compared with their matched controls. On the other hand, another retrospective chart study [

49] in ICU patients intubated at least 5 days or more showed a non-significant reduction in mean number of days to wean from ventilation with modafinil. Likewise, an RCT by Mansouri et al examined the effect of of modafinil administration on cognitive dysfunction, weaning and hospital stay after on pump coronary artery bypass grafting surgery [

50]. The patients received 200 mg of modafinil on the day of the surgery, and 200 mg on the morning after surgery. The results showed that modafinil was associated with significantly decreased time to reach consciousness, ventilator time in the ICU, length of stay in ICU, duration of hospitalization, and arterial blood carbon dioxide pressure. No major adverse effects were noted. These results are in accordance with a previous prospective, randomized, double-blind study reporting that modafinil in a single postoperative dose of 200 mg significantly improved self-reported recovery variables after general anesthesia, including alertness and fatigue [

43].

4.2. ICU Patients with Taumatic and Non-Traumatic Brain Injury

The evidence concerning the potential benefits of modafinil in the critically ill population seem to be more compelling in patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI). In an earlier RCT including patients with chronic TBI modafinil ameliorated EDS, but not fatigue at week 4, but not at week 10 compared with placebo [

51]. Modafinil was safe and well tolerated, although insomnia was reported significantly more often with modafinil. In a RCT conducted by Kaiser et al the administration of 100 to 200 mg of modafinil in 20 ICU patients with TBI who had fatigue, EDS or both, was well tolerated and ameliorated EDS [

52]. Although their fatigue was not improved, the performance during the maintenance of wakefulness test improved in the modafinil group. Likewise, a retrospective study in ICU patients treated with amantadine and/or modafinil following TBI showed that the median GCS increased by a median of 1 and that the treatment well tolerated [

53]. More recently, Zand et al published the results of double-blind RCT about the efficacy of oral modafinil on the enhancement of consciousness recovery in adult ICU patients with moderate to severe acute TBI [

54]. The analysis showed a significant a greater proportion of patients with an increase in total GCS by 1 or 2 units in the modafinil group (56% vs. 34% and 54% vs. 32% respectively). On the other hand, mixed results concerning the effectiveness of modafinil on wakefulness in the ICU were provided by Leclerc et al [

55]. This retrospective study evaluating 87 ICU patients treated with amantadine and/or modafinil following acute non-traumatic intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), ischemic stroke (IS), or subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) [

55]. Indications for the administration of amantadine and/or modafinil included somnolence (77%), not following commands (32%), lack of eye opening (28%), or low GCS (17%). The most common initial dose was 100 mg twice daily for both drugs. According to the results 55% of the patients receiving amantadine monotherapy and 33% of them receiving both amantadine and modafinil were considered responders. The rate of discharge was significant higher in the responders group. However, no responders were noticed among the 15 patients that received modafinil monotherapy. Yet, it should be noted that modafinil was the initial neurostimulant administered in only in 15% of the patients. Modafinil was discontinued in only one patient due to insomnia and agitation. A series of other studies in mixed populations of patients with stroke reported a beneficial effect of modafinil on various outcomes [

36,

37,

38,

39] including EDS and fatigue [

56,

57,

58,

59].

5. Conclusion

Daytime sleepiness and fatigue during and after critical illness is a complex and multifactorial phenomenon. Because of a number of factors such as medications, the type of critical illness, muscle dysfunction, sedation, drug abuse and pain, critically ill patients are prone to develop cognitive problems, EDS and fatigue. The present article reviewed literature to describe modafinil use for wakefulness promotion in ICU. Although to date there are only 3 RCTs of the effects of modafinil there is some evidence of the benefits of this drug in critically ill patients with cognitive dysfunction or EDS. Generally, the administration of modafinil appears to be safe in hypoactive patients with EDS during their stay in the ICU. Moreover, there are some data showing that modafinil may have potential advantages when used in some critically ill patients to improve wakefulness and encourage their participation in physical therapy. In that way, modafinil could enhance patient recovery and reduce ICU stay as critically ill patients who are capable to obtain wakefulness are more anticipated to wean from mechanical ventilation and involve in physical therapy. However, it should be noted that the available data are scarce and confounding bias is likely. Larger RCTs are essential to clarify the role modafinil in the treatment of EDS and hypoactiveness in the ICU. These studies should also determine the characteristics of the ICU patients that could be benefit from modafinil administration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K; methodology, S.K; writing—original draft preparationSK; writing—review and editing, S.K; visualization, S.K; supervision, S.K; project administration, S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Matthews, E.E. Sleep Disturbances and Fatigue in Critically Ill Patients. AACN Adv. Crit. Care 2011, 22, 204–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eschbach, E.; Wang, J. Sleep and critical illness: A review. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1199685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerrard, P.; Malcolm, R. Mechanisms of modafinil: A review of current research. 2007, 3, 349–364. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R. Approved and Investigational Uses of Modafinil. Drugs 2008, 68, 1803–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.W.; Skrobik, Y.; Gélinas, C.; Needham, D.M.; Slooter, A.J.C.; Pandharipande, P.P.; Watson, P.L.; Weinhouse, G.L.; Nunnally, M.E.; Rochwerg, B.; et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Management of Pain, Agitation/Sedation, Delirium, Immobility, and Sleep Disruption in Adult Patients in the ICU. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 46, e825–e873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamdar, B.B.; Needham, D.M.; Collop, N.A. Sleep Deprivation in Critical Illness. J. Intensiv. Care Med. 2011, 27, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamdar, B.B.M.; King, L.M.R.; Collop, N.A.; Sakamuri, S.B.; Colantuoni, E.; Neufeld, K.J.; Bienvenu, O.J.; Rowden, A.M.; Touradji, P.; Brower, R.G.; et al. The Effect of a Quality Improvement Intervention on Perceived Sleep Quality and Cognition in a Medical ICU. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 41, 800–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friese, R.S. Sleep and recovery from critical illness and injury: A review of theory, current practice, and future directions*. Crit. Care Med. 2008, 36, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A.B.; Thornley, K.S.; Young, G.B.; Slutsky, A.S.; Stewart, T.E.; Hanly, P.J. Sleep in Critically Ill Patients Requiring Mechanical Ventilation. Chest 2000, 117, 809–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, J.M.; Majde, J.A.; Rector, D.M. Cytokines in immune function and sleep regulation. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2011, 98, 229–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felten, M.; Dame, C.; Lachmann, G.; Spies, C.; Rubarth, K.; Balzer, F.; Kramer, A.; Witzenrath, M. Circadian rhythm disruption in critically ill patients. Acta Physiol. 2023, 238, e13962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyko, Y.; Jennum, P.; Nikolic, M.; Holst, R.; Oerding, H.; Toft, P. Sleep in intensive care unit: The role of environment. J. Crit. Care 2017, 37, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhlesi, B. , Tulaimat, A. , Faibussowitsch, I., Wang, Y., & Evans, A. T. Obesity hypoventilation syndrome: prevalence and predictors in patients hospitalized with respiratory failure. Chest 2007, 131, 164–171. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, M.R.; Shashaty, M.G. Impact of Obesity in Critical Illness. Chest 2021, 160, 2135–2145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horner, R.L. Emerging principles and neural substrates underlying tonic sleep-state-dependent influences on respiratory motor activity. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 2553–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Abad, M.; Verceles, A.C.; E Brown, J.; Scharf, S.M. Sleep-Disordered Breathing May Be Under-Recognized in Patients Who Wean From Prolonged Mechanical Ventilation. Respir. Care 2012, 57, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, S.; McGrath, B. Laryngeal complications after tracheal intubation and tracheostomy. BJA Educ. 2021, 21, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.L.; Yadollahi, A.; He, K.; Xu, Y.; Piper, B.; Case, E.; Chervin, R.D.; Lisabeth, L.D. Overnight Rostral Fluid Shifts Exacerbate Obstructive Sleep Apnea After Stroke. Stroke 2021, 52, 3176–3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponsford, J.L.; Ziino, C.; Parcell, D.L.; et al. Fatigue and sleep disturbance following traumatic brain injury—their nature, causes, and potential treatments. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2012, 27, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, T.F.; Diógenes, F.P.; França, F.R.; Dantas, R.C.; Araujo, J.F.; AL Menezes, A. The sleep – wake cycle in the late stage of cerebral vascular accident recovery. Biol. Rhythm. Res. 2005, 36, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundigler, G.; Delle-Karth, G.; Koreny, M.; Zehetgruber, M.; Steindl-Munda, P.; Marktl, W.; Fertl, L.; Siostrzonek, P. Impaired circadian rhythm of melatonin secretion in sedated critically ill patients with severe sepsis*. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 30, 536–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermans, G.; De Jonghe, B.; Bruyninckx, F.; Berghe, G.V. Clinical review: Critical illness polyneuropathy and myopathy. Crit. Care 2008, 12, 238–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourne, R.S.; Mills, G.H. Sleep disruption in critically ill patients – pharmacological considerations. Anaesthesia 2004, 59, 374–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagappa, M.; Weingarten, T.N.; Montandon, G.; Sprung, J.; Chung, F. Opioids, respiratory depression, and sleep-disordered breathing. Best Pr. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 2017, 31, 469–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scammell, T.E.; Estabrooke, I.V.; McCarthy, M.T.; Chemelli, R.M.; Yanagisawa, M.; Miller, M.S.; Saper, C.B. Hypothalamic Arousal Regions Are Activated during Modafinil-Induced Wakefulness. J. Neurosci. 2000, 20, 8620–8628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignot, E.; Nishino, S.; Guilleminault, C.; Dement, W.C. Modafinil Binds to the Dopamine Uptake Carrier Site with Low Affinity. Sleep 1994, 17, 436–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallopin, T.; Luppi, P.-H.; Rambert, F.A.; Frydman, A.; Fort, P. Effect of the Wake-Promoting Agent Modafinil on Sleep-Promoting Neurons from the Ventrolateral Preoptic Nucleus: an In Vitro Pharmacologic Study. Sleep 2004, 27, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraro, L.; Tanganelli, S.; O'Connor, W.T.; Antonelli, T.; Rambert, F.; Fuxe, K. The vigilance promoting drug modafinil decreases GABA release in the medial preoptic area and in the posterior hypothalamus of the awake rat: possible involvement of the serotonergic 5-HT3 receptor. Neurosci. Lett. 1996, 220, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darwish, M.; Kirby, M.; D’andrea, D.M.; Yang, R.; Hellriegel, E.T.; Robertson, P. Pharmacokinetics of armodafinil and modafinil after single and multiple doses in patients with excessive sleepiness associated with treated obstructive sleep apnea: A randomized, open-label, crossover study. Clin. Ther. 2010, 32, 2074–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, J.R.L.; Feldman, N.T.; Bogan, R.K. Dose effects of modafinil in sustaining wakefulness in narcolepsy patients with residual evening sleepiness. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2005, 7, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, J.R.L.; Feldman, N.T.; Bogan, R.K.; Nelson, M.T.; Hughes, R.J. Dosing Regimen Effects of Modafinil for Improving Daytime Wakefulness in Patients With Narcolepsy. Clin. Neuropharmacol. 2003, 26, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Provigil. Package insert. Teva Pharmaceuticals; 2018.

- Nasr, S.; Wendt, B.; Steiner, K. Absence of mood switch with and tolerance to modafinil: A replication study from a large private practice. J. Affect. Disord. 2006, 95, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wisor, J. Modafinil as a Catecholaminergic Agent: Empirical Evidence and Unanswered Questions. Front. Neurol. 2013, 4, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- E Scammell, T.; Matheson, J. Modafinil: a novel stimulant for the treatment of narcolepsy. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 1998, 7, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, G.T.; Weiss, M.D.; Lou, J.-S.; Jensen, M.P.; Abresch, R.T.; Martin, T.K.; Hecht, T.W.; Han, J.J.; Weydt, P.; Kraft, G.H. Modafinil to treat fatigue in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: An open label pilot study. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2005, 22, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.N.; A Howard, C.; Kemp, D.W. Modafinil for the Treatment of Multiple Sclerosis-Related Fatigue. Ann. Pharmacother. 2010, 44, 1098–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, L.; Andrews, M.; Stoddard, G. Modafinil Treatment of Opioid-Induced Sedation. Pain Med. 2003, 4, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirz, S.; Nadstawek, J.; Kühn, K.; Vater, S.; Junker, U.; Wartenberg, H. Modafinil zur Behandlung der Tumorfatigue. Der Schmerz 2010, 24, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeBattista, C.; Lembke, A.; Solvason, H.B.; Ghebremichael, R.; Poirier, J. A Prospective Trial of Modafinil as an Adjunctive Treatment of Major Depression. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2004, 24, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fava, M.; Thase, M.E.; DeBattista, C. A Multicenter, Placebo-Controlled Study of Modafinil Augmentation in Partial Responders to Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors With Persistent Fatigue and Sleepiness. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2005, 66, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvin, E.; Boesjes, H.; Hol, J.; Ubben, J.F.; Klein, J.; Verbrugge, S.J.C. Modafinil reduces patient-reported tiredness after sedation/analgesia but does not improve patient psychomotor skills. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2010, 54, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larijani, G.E.; Goldberg, M.E.; Hojat, M.; Khaleghi, B.; Dunn, J.B.; Marr, A.T. Modafinil Improves Recovery After General Anesthesia. Anesthesia Analg. 2004, 98, 976–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, C.; Weaver, T.E.; Bae, C.J.; Strohl, K.P. Excessive Daytime Sleepiness in Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Mechanisms and Clinical Management. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2021, 18, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gajewski, M.; Weinhouse, G. The use of modafinil in the Intensive Care Unit. J Intensive Care Med 2016, 31, 142–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, M.; Jamil, M.G.; Kseibi, E. Modafinil for Wakefulness and Disorders of Consciousness in the Critical Care Units. Saudi Crit. Care J. 2022, 6, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, Y.; Thomas, M.C.; Miano, T.A.; Stemp, L.I.; Bonacum, J.T.; Hutchins, K.; Karras, G.E. Effect of Modafinil on Cognitive Function in Intensive Care Unit Patients: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2017, 58, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branstetter, L.; Gallagher, J.; Nichols, K.; Goyal, S.; Mukhtar, A. 970: Evaluation of the use of modafinil in critically ill patients: a retrospective chart review. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 50, 482–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeney, C.P.; Adeniyi, A. Effect of modafinil on time to wean from mechanical ventilation. Chest 2022, 162, A2622–2622A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, M.; Massoumi, G.; Rezaei-Hoseinabadi, M.K. Evaluation of the Effect of Modafinil on Respiratory and Cerebral Outcomes after Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery. ARYA Atherosclerosis Journal 2021, 17, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.; Weintraub, A.; Allshouse, A.; Morey, C.; Cusick, C.; Kittelson, J.; Harrison-Felix, C.; Whiteneck, G.; Gerber, D. A Randomized Trial of Modafinil for the Treatment of Fatigue and Excessive Daytime Sleepiness in Individuals with Chronic Traumatic Brain Injury. J. Head Trauma Rehabilitation 2008, 23, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, P.R.; Valko, P.O.; Werth, E.; Thomann, J.; Meier, J.; Stocker, R.; et al. Modafinil ameliorates excessive daytime sleepiness after traumatic brain injury. Neurology 2010, 75, 1780–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barra, M.E.; Izzy, S.; Sarro-Schwartz, A.; Hirschberg, R.E.; Mazwi, N.; Edlow, B.L. Stimulant Therapy in Acute Traumatic Brain Injury: Prescribing Patterns and Adverse Event Rates at 2 Level 1 Trauma Centers. J. Intensiv. Care Med. 2019, 35, 1196–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zand, Z.; Zand, F.; Asmarian, N.; Sabetian, G.; Masjedi, M.; Beizavinejad, Z.; Banifatemi, M.; Yousefi, O.; Taheri, R.; Niakan, A.; et al. Efficacy of oral modafinil on accelerating consciousness recovery in adult patients with moderate to severe acute traumatic brain injury admitted to intensive care unit: a randomized double-blind clinical trial. Neurosurg. Rev. 2024, 48, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclerc, A.M.; Riker, R.R.; Brown, C.S.; May, T.; Nocella, K.; Cote, J.; Eldridge, A.; Seder, D.B.; Gagnon, D.J. Amantadine and Modafinil as Neurostimulants Following Acute Stroke: A Retrospective Study of Intensive Care Unit Patients. Neurocritical Care 2020, 34, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, D.J.; Leclerc, A.M.; Riker, R.R.; Brown, C.S.; May, T.; Nocella, K.; Cote, J.; Eldridge, A.; Seder, D.B. Amantadine and Modafinil as Neurostimulants During Post-stroke Care: A Systematic Review. Neurocritical Care 2020, 33, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cross, D.B.; Tiu, J.; Medicherla, C.; Ishida, K.; Lord, A.; Czeisler, B.; Wu, C.; Golub, D.; Karoub, A.; Hernandez, C.; et al. Modafinil in Recovery after Stroke (MIRAS): A Retrospective Study. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2020, 29, 104645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bivard, A.; Lillicrap, T.; Krishnamurthy, V.; Holliday, E.; Attia, J.; Pagram, H.; et al. MIDAS (modafinil in debilitating fatigue after stroke): A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over trial. Stroke 2017, 48, 1293–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, M.M.; Goodin, P.; Parsons, M.W.; Lillicrap, T.; Spratt, N.J.; Levi, C.R.; Bivard, A. Modafinil treatment modulates functional connectivity in stroke survivors with severe fatigue. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).