1. Introduction

Neurofibromatosis 1 (NF1) is a genetic tumor predisposition syndrome that affects individuals worldwide, with an estimated prevalence ranging from 1 in 3,000 to 6,000 people. [

1,

2] It is caused by mutations in the

NF1 gene affecting nervous system growth and regulation. The condition results from insufficient neurofibromin production due to haploinsufficiency disrupts the regulation of the RAS/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, leading to increased cellular proliferation, overactive autocrine and paracrine signaling, and enhanced inflammatory responses in Schwann cell precursors.[

3,

4] It manifests as multisystem tumors, including cutaneous and subcutaneous neurofibromas, optic gliomas, and spinal or plexiform neurofibromas (PN). PN is one of the most common tumor types in patients with NF1.Other features include café-au-lait spots, Lisch nodules in the iris, skeletal abnormalities like scoliosis, and vascular complications. Neurological and cognitive impairments are also common, significantly impacting quality of life (QoL).

Central nervous system pathology is a major contributor to morbidity in NF1, while malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNST) are the leading cause of mortality in adult patients with the condition. Imaging is essential in the diagnosis and management of NF1, playing a critical role in assessing disease progression and guiding treatment strategies. A whole-body MRI (WBMRI) is recommended for detecting deep internal brain, optic and nerve abnormalities. MRI is key for diagnosis and distinguishing benign from malignant nerve sheath tumors, with features like tumor enlargement and irregular margins suggesting malignancy [

7,

8]. In recent years, there has been a growing interest in targeting the MAPK pathway for the treatment of NF1-related tumors. Selumetinib (AZD6244, ARRY-142886), an oral MEK1/2 inhibitor that effectively inhibits cell growth and induces apoptosis in tumor cells. Selumetinib has been evaluated in clinical trials involving both adults and children with various malignancies. In April 2020, the FDA approved selumetinib (25 mg/m² twice daily) for children aged ≤2 years with NF1 and inoperable PN.[

5] This approval represents a significant advancement, marking the first treatment specifically designed for this condition arising from mutations in the NF1 gene. Clinical studies have demonstrated that selumetinib possesses a favorable safety profile and efficacy, particularly in achieving sustained tumor shrinkage across diverse neurofibromatosis types.[

6] These findings underscore the potential of selumetinib as a critical therapeutic option in the management of NF1-related tumors. This review will further discuss MRI use and management strategies for NF1 and presents a detailed case of a patient diagnosed with NF1 who was treated with Selumetinib.

2. Presentation and Pathophysiology of NF1

NF1 results from a heterozygous mutation in the NF1 gene located on chromosome 17q11.2, occurring during gametogenesis. The NF1 gene encodes neurofibromin, a tumor suppressor protein that inhibits the activity of the GDPase-activating domain (GAP) of the intracellular signaling protein Ras (rat sarcoma), which is involved in promoting cellular proliferation. The loss of the wild-type NF1 allele in Schwann lineage cells leads to the development of peripheral nerve sheath tumors, which is the primary mutation identified in NF1. Neurofibromin's activity is crucial across various tissue lineages, and a 50% reduction in functional neurofibromin affects all organ systems, resulting in a penetrance of 100%. This means that all patients with a pathogenic mutation will exhibit signs of the disease. Tumors typically arise after the loss of the remaining NF1 allele, particularly in Schwann cell progenitors, leading to nerve sheath tumors.

Clinically, NF1 is characterized by the presence of cutaneous neurofibromas (CN), which originate from small nerves in the skin, and plexiform neurofibromas (PN), which arise from Schwann cells supporting larger peripheral nerves and can involve multiple nerve bundles (nerve plexi). The diagnostic criteria for NF1 were updated in 2021 (

Table 1), and patients with NF1 are at risk for both benign and malignant nerve sheath tumors, as well as neurocognitive and developmental deficits, mood disorders, osseous lesions like dystrophic scoliosis and pseudoarthrosis, and neuroendocrine tumors, including breast cancer. Early diagnosis, ideally before tumor development, is essential to offer appropriate guidance for managing potential benign and malignant neoplasms. The condition is often identified through clinical criteria (

Table 1), such as six or more CALMs, neurofibromas, or Lisch nodules observed via slit-lamp examination.

Clinical manifestations of NF1 are diverse, with several types of tumors observed in the nervous system.

Table 2 provides an in-depth description of these clinical manifestations and their associated tumor types. Patients with NF1 are predisposed to various non-nervous tumors and systemic complications. Hematologic malignancies such as chronic myeloid leukemia and juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia occur more frequently, with treatment similar to the general population. Breast cancer risk is significantly elevated, particularly in women under 50, with poorer prognosis due to therapy resistance; early mammographic and MRI screening is recommended. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) are common, often benign but symptomatic, and managed primarily through surgical resection as they are unresponsive to imatinib. Rare pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas can cause severe symptoms like hypertension, managed through surgical resection or targeted therapies. Duodenal carcinoids are rare but distinctive, requiring surgery or somatostatin analogs. Skeletal deformities such as scoliosis, pseudoarthrosis, and osteoporosis can lead to pain and dysfunction, often requiring surgical intervention or lifestyle modifications. Pigmentation abnormalities like café-au-lait macules and Lisch nodules are common but benign, while neurocognitive deficits, including ADHD and learning disabilities, require multidisciplinary management. Patients with NF1 are prone to cardiovascular issues like hypertension and congenital heart defects, and neurovascular conditions such as moyamoya syndrome and cerebral aneurysms. Management includes targeted treatments and regular monitoring to prevent complications like strokes. (doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S362791)

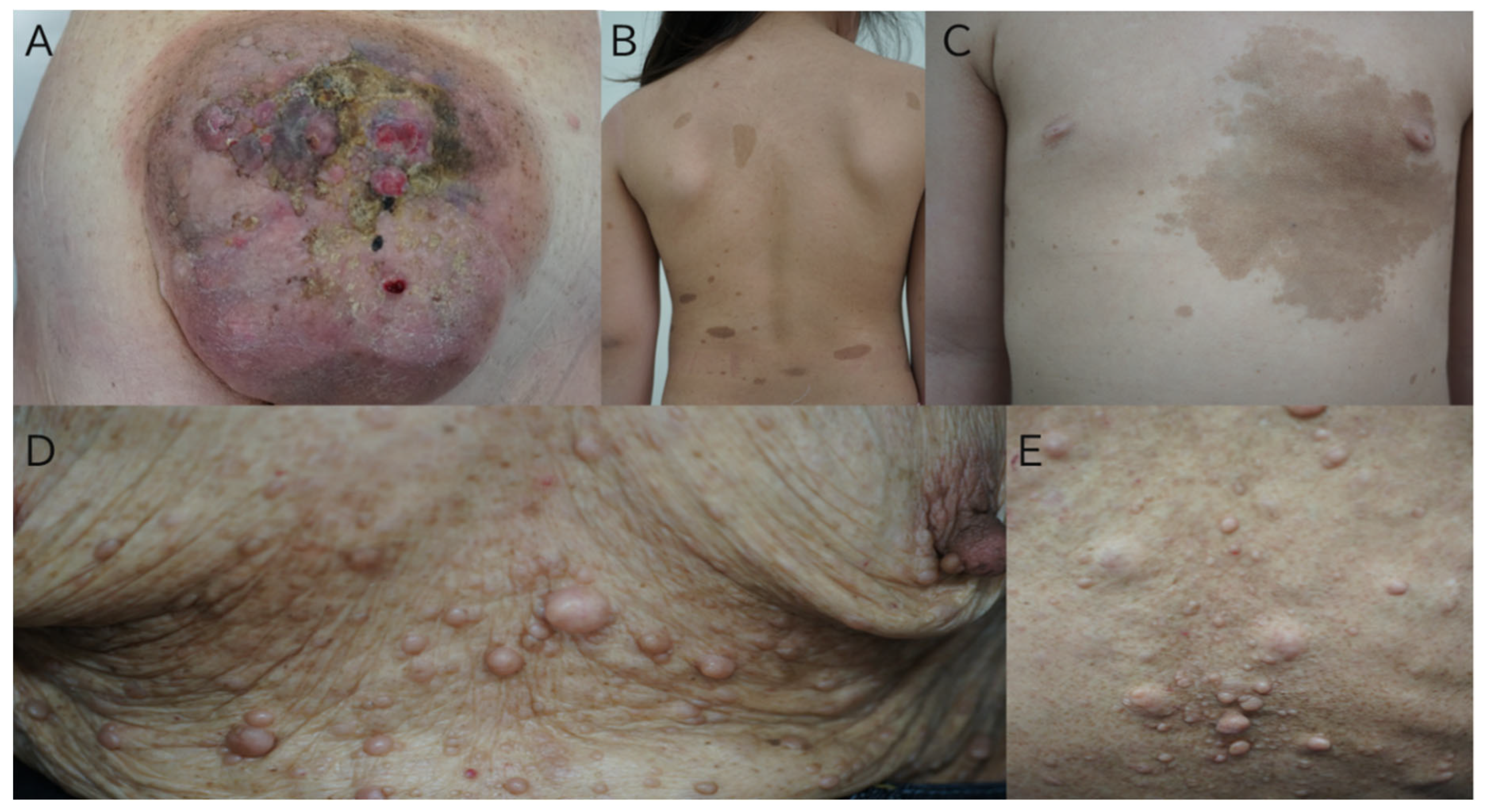

The following is a picture of typical skin findings of NF1 (

Figure 1).

3. MRI in NF1

In evaluating NF1, imaging plays a crucial role in diagnosing and managing patients,[

10] necessitating a thorough assessment of the various affected organs to achieve accurate disease staging. This approach aids in establishing diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic pathways. This work aims to offer a pictorial review of neuroradiological features associated with NF1, with a focus on MRI images, outlining both technical considerations and MRI findings.

Table 3 describes the MRI Characteristics and Prevalence of Common CNS Manifestations in NF1 [

8]Additionally, we analyze the prevalence of these features in a retrospective study involving a cohort of NF1 patients and compare our findings with existing literature. MRI remains the preferred imaging method for examining brain and spinal cord lesions. It also helps differentiate between benign and malignant nerve sheath tumors, with malignancy indicators such as tumor growth, size exceeding 5 cm, poorly defined margins, absence of a central hypointense target on T2-weighted images, and heterogeneity with central necrosis.[

8]

Multiparametric MRI, commonly applied in prostate imaging, broadly refers to a technique that incorporates multiple sequences, such as anatomical, diffusion, and Dixon-based pre- and post-contrast imaging. Whole-body MRI (WBMRI) has been extensively investigated for its role in managing neurocutaneous syndromes, including neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) and other malignancy-related conditions, due to its comprehensive imaging potential. to assess tumor burden and differentiate between various tumor types in affected patients.[

11]

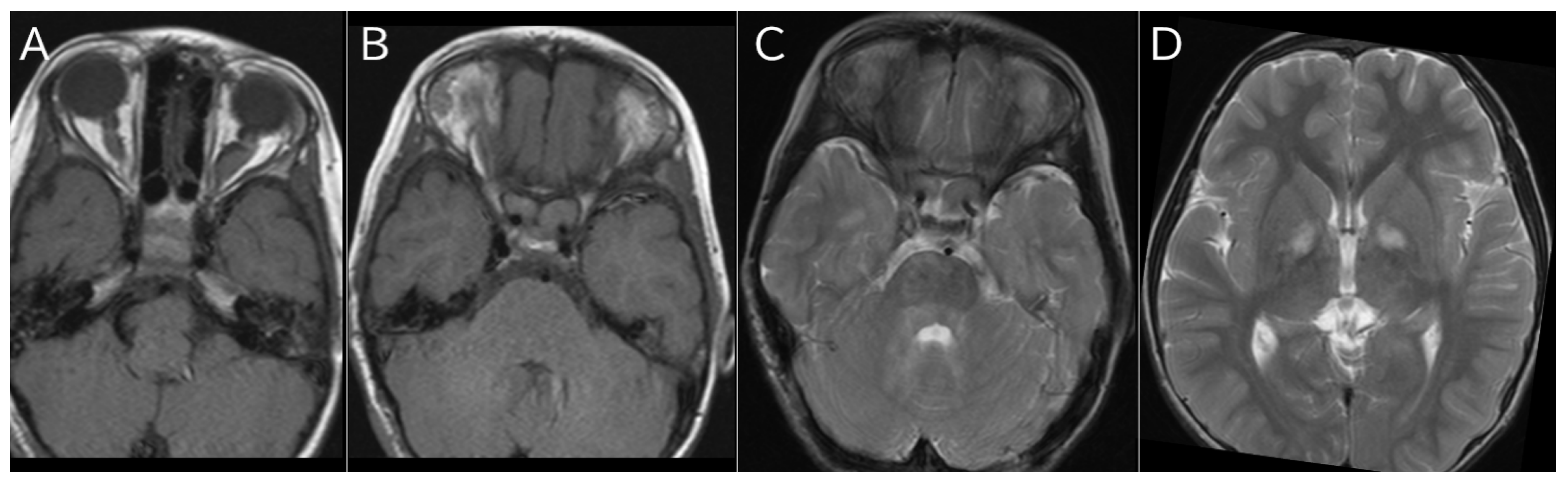

A typical MRI image of NF1 is shown (

Figure 2).

4. Management

Physical Destruction: For individuals with numerous cutaneous neurofibromas, excision may not be practical. Carbon dioxide laser treatment under general anesthesia has been suggested for small to medium neurofibromas. However, a limitation of this method is the potential for resulting depigmented, atrophic scars.[

12]

Treatment of Plexiform Neurofibromas (PNs) presents additional challenges due to nerve involvement. Surgical resection remains the gold standard treatment but is often not feasible. Alternative modalities are used for tumors that cannot be surgically removed.

5. Targeted Genetic Treatment

The immunosuppressant sirolimus has proven effective in slowing PN progression and reducing associated pain by inhibiting the mTOR pathway, commonly involved in NF1 tumor growth.[

13] Tipifarnib, by blocking RAS signaling through inhibition of RAS farnesylation, downregulates this pro-oncogenic pathway. Imatinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, has also been used for PNs, with reports of both halting tumor progression and achieving a median 26.5% reduction in tumor volume.

Direct tyrosinase inhibitors, such as kojic acid, have been proposed for targeting hyperpigmentation and café-au-lait macules (CALMs) in NF1.[

14] Other inhibitors, including MEK inhibitor PD032059 and PKA-cAMP pathway inhibitor HA1004, also target genetic pathways involved in NF1. Furthermore, given that vitamin D levels are typically lower in NF1 patients, ultraviolet B irradiation has been suggested to boost vitamin D levels and possibly reduce hyperpigmentation.[

15]

6. Role of MEK Inhibitors in NF1 and Pediatric Populations

Current MEK inhibitors (MEKi) are derived from similar chemical structures, leading to shared pharmacological characteristics. Five MEK inhibitors, all available in oral form, share generally similar metabolic and excretory profiles but differ in their half-life. They present a comparable side effect profile, commonly including rash, paronychia, reduced cardiac function, and lab abnormalities (such as elevated creatine kinase [CK] and liver dysfunction). Preclinical studies on their ability to penetrate the brain have yielded varied results, and these findings have not consistently predicted efficacy against central nervous system (CNS) tumors.

MEKi has been widely studied in adults, particularly for BRAF-mutated melanoma and other cancers. Emerging evidence also indicates that MEKi may alter the tumor immune environment, enhancing their effectiveness beyond direct tumor targeting. Although the MEKi share chemical properties, they may exhibit clinically significant differences. While MEKi show promise for NF1-related conditions, no direct comparison studies of their clinical efficacy, toxicity profiles, or impact on the tumor immune microenvironment have been conducted. Currently, distinctions among MEKi in terms of formulation (particularly child-friendly options), regulatory approval, insurance availability, and NF1-specific clinical experience may be the most critical factors influencing their use. [

16,

17,

18]

7. MEK Inhibitors Approved for Clinical Use

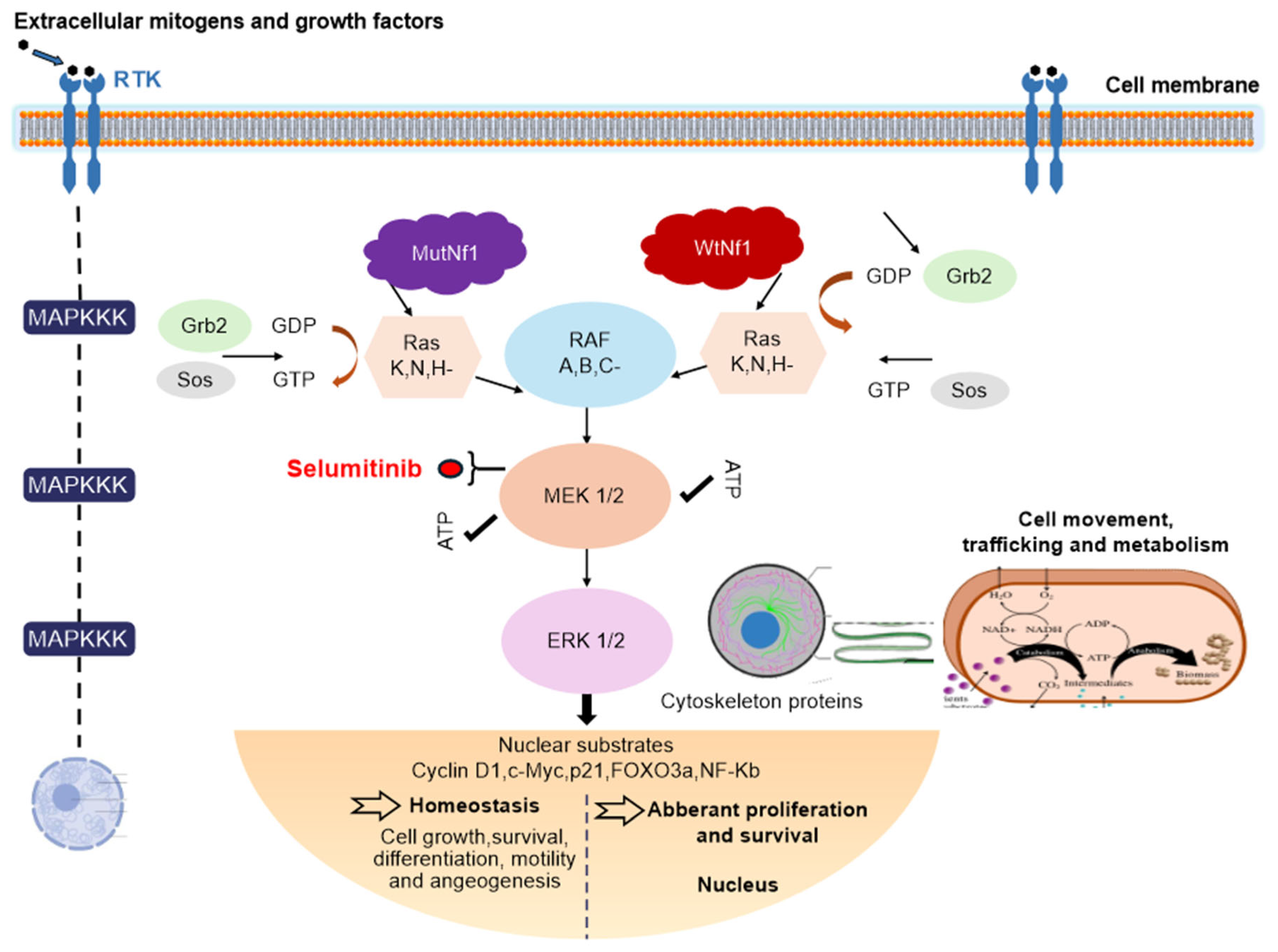

Selumetinib is an oral MEK inhibitor that targets MEK1 and MEK2, key components of the RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK signaling pathway, which is frequently activated in various cancers. This inhibition prevents the phosphorylation of ERK, leading to reduced signaling that drives cell proliferation and survival. In the context of neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), the absence of functional neurofibromin—an essential Ras GTPase-activating protein—results in continuous Ras activation, contributing to tumor growth. These painful and debilitating tumors are characterized by increased Ras (Rat Sarcoma) and MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) signaling. Treatments targeting the Ras pathway have shown limited effectiveness, as NF1 primarily arises from heterozygous loss-of-function mutations in the tumor suppressor gene NF1. According to Knudson's two-hit hypothesis, somatic inactivation of the wild-type allele in Schwann cells of neurofibromas leads to hyperactivation of the RAS MAPK pathway.

The NF1 gene encodes neurofibromin, which is involved in regulating RAS-MAPK signaling and is one of several genes associated with RASopathies. Numerous downstream pathways, including RALGDS, PI3K, RASSF, TIAM1, BRAP2, RIN, and GRB7, play roles in Ras signaling, with RAS-MAPK being the most extensively researched. In NF1, selumetinib has demonstrated promise in pediatric patients, following positive outcomes in adults with advanced cancers.

The MAPK pathways can be divided into three main subfamilies: JNK/SAPK (c-Jun N-terminal kinase/Stress-activated protein kinase), p38 MAPK, and MEK/ERK (extracellular signal-regulated kinase). MEK contains two consensus kinase motifs responsible for phosphorylating serine/threonine and tyrosine residues. The homologues MEK1 and MEK2 share a single substrate, ERK1/2, which influences various cellular functions, including transcription, cell cycle progression, and motility. When activated, ERK, along with RAF (rapidly accelerated fibrosarcoma) and MEK, moves to the nucleus, activating cyclin D1 and downregulating p27, thus promoting cell proliferation and potentially inhibiting apoptosis through anti-apoptotic proteins (

Figure 3).

As upstream regulators of the ERK pathway, MEK1/2 play critical roles in many cancers. Selumetinib's oral administration has been shown to inhibit ERK phosphorylation, resulting in decreased numbers, volume, and proliferation of neurofibromas in animal models. The NF1 gene is situated on chromosome 17q11.2 and encodes neurofibromin, a 2818-amino acid cytoplasmic protein that inhibits Ras GTPase activity by converting active GTP-bound Ras to inactive GDP-bound Ras. Dysregulation of Ras leads to heightened activation of RAF/MEK and AKT/mTOR pathways, fostering cell growth in NF1-deficient cell types.

Multiple therapeutic approaches have been investigated for NF1. Since neurofibromin acts as a Ras inhibitor, initial research focused on RAS inhibitors such as tipifarnib. Additionally, as neurofibromin regulates mTOR signaling, agents like rapamycin and its analogs are being explored for tumor treatment. Other therapies under consideration include antihistamines (like ketotifen), angiogenesis inhibitors (such as thalidomide), antifibrotic agents (like pirfenidone), and lovastatin. The absence of functional neurofibromin in NF1 patients leads to uncontrolled Ras signaling and tumor development, prompting phase 2 clinical trials of various agents, including tipifarnib, pirfenidone, sirolimus, pegylated interferon alfa-2b, and imatinib, with the aim of improving progression-free survival and reducing plexiform neurofibroma volume.

8. Pharmacological Overview of Selumetinib

MEK1/2 inhibitors were initially developed for cancer treatment in the early 2000s. Early compounds like CI-1040 did not show efficacy in lung, colon, or breast cancers. However, selumetinib, a second-generation MEK inhibitor, has proven more effective in preclinical models. The first phase I trial involved patients with advanced cancers, including melanoma, breast, and colorectal types, confirming the drug’s tolerability and safety. Subsequent phase II trials assessed its effectiveness in gastrointestinal, thyroid, non-small cell lung, ovarian cancers, melanoma, and acute myeloid leukemia. Eventually, the focus shifted from cancer therapy to treatments for rare diseases.

The recommended dosage of selumetinib is 25 mg/m², administered orally twice daily on an empty stomach, available in 10 mg and 25 mg capsules. In patients with moderate hepatic impairment, the dose should be reduced to 20 mg/m² twice daily. Common adverse effects, occurring in approximately 40% of patients, include vomiting, rash, abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, dry skin, fatigue, musculoskeletal pain, fever, acneiform rash, stomatitis, headache, paronychia, and pruritus. Serious potential side effects may include cardiomyopathy, ocular toxicity (such as retinal vein occlusion and impaired vision), and elevated creatinine phosphokinase levels. As selumetinib is metabolized by the CYP3A4 enzyme, co-administration with CYP3A4 inhibitors or inducers is not advisable. Its use during pregnancy and lactation is discouraged due to insufficient data, and safety and efficacy in pediatric patients younger than 2 years have not been established. The mean oral bioavailability is around 62%, with peak concentrations reached within 1 to 1.5 hours and a mean elimination half-life of 6.5 hours.

Selumetinib has shown promising efficacy as a non-surgical option for children with NF1-PN, with a demonstrated ability to shrink PN and improve patient-reported outcomes alongside an acceptable tolerability profile [

19,

20,

21]. The availability of medical therapy as another treatment option to surgery introduces additional dimensions in clinical decision making and management considerations.

It is approved in Japan for the treatment of paediatric patients three years of age and older with plexiform neurofibromas (PNs) in neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) with clinical symptoms, such as pain and disfigurement, and PNs which cannot be completely removed by surgery without risk of substantial morbidity.[

22]

The approval by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) is based on positive results from the SPRINT Stratum 1 Phase II trial sponsored by the National Institutes of Health's National Cancer Institute (NCI) Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program (CTEP). The trial showed Selumetinib, an oral treatment option, reduced the size of inoperable tumours in children.[

22,

23]

` Additionally, a Phase I trial in Japanese paediatric NF1 patients with symptomatic and inoperable PNs was also evaluated as a basis for the approval, with the trial showing tumour reduction.

9. Patents

The introduction of MEK inhibitors, particularly selumetinib, marks a significant advancement in the management of NF1, offering a targeted treatment for a condition that was previously difficult to address. By leveraging insights into the RAS-MAPK pathway, these therapies aim to reduce tumor burden and enhance the quality of life for individuals with NF1. Nevertheless, Further research is needed to optimize treatment approaches, overcome existing challenges.

As precision medicine continues to evolve, the outlook for NF1 management grows increasingly optimistic, bringing renewed hope to patients and families navigating this complex disorder.

Author Contributions

The following authors were involved in the preparation of this paper, conceptualization, methodology, writing, original draft preparation, review and editing G,I.; supervision, S.K., S.H., K.O., E.H., K.N. and H.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This review did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable for studies not involving humans.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abdel-Aziz NN, El-Kamah GY, Khairat RA, Mohamed HR, Gad YZ, El-Ghor AM, et al. Mutational spectrum of NF1 gene in 24 unrelated Egyptian families with neurofibromatosis type 1. Mol Genet Genomic Med. (2021) 9:e1631. [CrossRef]

- Bergqvist C, Servy A, Valeyrie-Allanore L, Ferkal S, Combemale P, Wolkenstein P, et al. Neurofibromatosis 1 French national guidelines based on an extensive literature review since 1966. Orphanet J Rare Dis. (2020) 15:37. [CrossRef]

- Buchholzer, S., Verdeja, R., & Lombardi, T. (2021). Type I neurofibromatosis: Case report and review of the literature focused on oral and cutaneous lesions. Dermatopathology, 8(1), 17-24. [CrossRef]

- Kunc, V., Venkatramani, H., & Sabapathy, S. R. (2019). Neurofibromatosis 1 was diagnosed in mother only after a follow-up of her daughter. Indian Journal of Plastic Surgery, 52(2), 260. [CrossRef]

- Kallionpää RA, Uusitalo E, Leppävirta J, Pöyhönen M, Peltonen S, Peltonen J. Prevalence of neurofibromatosis type 1 in the Finnish population. Genet Med. (2018) 20:1082–6. [CrossRef]

- Campagne, O., Yeo, K. K., Fangusaro, J., & Stewart, C. F. (2021). Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of selumetinib. Clinical Pharmacokinetics, 60(3), 283–303. [CrossRef]

- Ly, K. Ina, Jaishri O. Blakeley. The diagnosis and management of neurofibromatosis type 1. Medical Clinics 103.6 (2019): 1035-1054. [CrossRef]

- Di Pietro S, Reali L, Tona E, Belfiore G, Praticò AD, Ruggieri M, David E, Foti PV, Santonocito OG, Basile A, Palmucci S. "Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Central Nervous System Manifestations of Type 1 Neurofibromatosis: Pictorial Review and Retrospective Study of Their Frequency in a Cohort of Patients." Journal of Clinical Medicine 13.11 (2024): 3311. [CrossRef]

- Wilson BN, John AM, Handler MZ, Schwartz RA. Neurofibromatosis type 1: New developments in genetics and treatment. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 84.6 (2021): 1667-1676. [CrossRef]

- Ahlawat, S.; Blakeley, J.O.; Langmead, S.; Belzberg, A.J.; Fayad, L.M. Current status and recommendations for imaging in neurofibromatosis type 1, neurofibromatosis type 2, and schwannomatosis. Skelet. Radiol. 2020, 49, 199–219. [CrossRef]

- Thakur U, Ramachandran S, Mazal AT, Cheng J, Le L, Chhabra A. Multiparametric whole-body MRI of patients with neurofibromatosis type I: spectrum of imaging findings. Skeletal radiology (2024): 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Chiang YZ, Al-Niaimi F, Ferguson J, August PJ, Madan V. Carbon dioxide laser treatment of cutaneous neurofibromas. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2012: 2(1):7. [CrossRef]

- Weiss B, Widemann BC, Wolters P, Dombi E, Vinks A, Cantor A et al. Sirolimus for progressive neurofibromatosis type 1-associated plexiform neurofibromas: a neurofibromatosis Clinical Trials Consortium phase II study. Neuro Oncol 2015; 17:596-603. [CrossRef]

- Allouche J, Bellon N, Saidani M, Stanchina-Chatrousse L, Masson Y, Patwardhan A et al. In vitro modeling of hyperpigmentation associated to neurofibromatosis type 1 using melanocytes derived from human embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015; 112:9034-9. [CrossRef]

- Nakayama J, Imafuku S, Mori T, Sato C. Narrowband ultraviolet B irradiation increases the serum level of vitamin D(3) in patients with neurofibromatosis 1. J Dermatol 2013;40:829-31. [CrossRef]

- Baumann D, Hagele T, Mochayedi J, et al. Proimmunogenic impact of MEK inhibition synergizes with agonist anti-CD40 immunostimulatory antibodies in tumor therapy. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):2176. [CrossRef]

- Erkes DA, Cai W, Sanchez IM, et al. Mutant BRAF and MEK inhibitors regulate the tumor immune microenvironment via pyroptosis. Cancer Discov. 2020;10(2):254–269. [CrossRef]

- Poon E, Mullins S, Watkins A, et al. The MEK inhibitor selumetinib complements CTLA-4 blockade by reprogramming the tumor immune microenvironment. J Immunother Cancer. 2017;5(1):63. [CrossRef]

- Dombi E, Baldwin A, Marcus LJ, Fisher MJ, Weiss B, Kim A, Whitcomb P, Martin S, Aschbacher-Smith LE, Rizvi TA, et al. Activity of selumetinib in neurofibromatosis type 1-related plexiform neurofibromas. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(26):2550–60. [CrossRef]

- Gross AM, Wolters PL, Dombi E, Baldwin A, Whitcomb P, Fisher MJ, Weiss B, Kim A, Bornhorst M, Shah AC, Martin S, Roderick MC, Pichard DC, Carbonell A, Paul SM, Therrien J, Kapustina O, Heisey K, Clapp DW, Zhang C, Peer CJ, Figg WD, Smith M, Glod J, Blakeley JO, Steinberg SM, Venzon DJ, Doyle LA, Widemann BC. Selumetinib in children with inoperable plexiform neurofibromas. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(15):1430–42. [CrossRef]

- Gross AM, Glassberg B, Wolters PL, Dombi E, Baldwin A, Fisher MJ, Kim A, Bornhorst M, Weiss BD, Blakeley JO, Whitcomb P, Paul SM, Steinberg SM, Venzon DJ, Martin S, Carbonell A, Heisey K, Therrien J, Kapustina O, Dufek A, Derdak J, Smith MA, Widemann BC. Selumetinib in children with neurofibromatosis type 1 and asymptomatic inoperable plexiform neurofibroma at risk for developing tumor-related morbidity. Neuro Oncol. 2022;24(11):1978–88. [CrossRef]

- Koselugo (selumetinib) Japanese prescribing information; 2022.

- Gross AM, Wolters PL, Dombi E, Baldwin A, Whitcomb P, Fisher MJ, Weiss B, Kim A, Bornhorst M, Shah AC, Martin S, Roderick MC, Pichard DC, Carbonell A, Paul SM, Therrien J, Kapustina O, Heisey K, Clapp DW, Zhang C, Peer CJ, Figg WD, Smith M, Glod J, Blakeley JO, Steinberg SM, Venzon DJ, Doyle LA, Widemann BC. Selumetinib in children with inoperable plexiform neurofibromas. N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr 9;382(15):1430-1442. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).