Submitted:

06 June 2025

Posted:

09 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Computer Vision: Enabling Visual Perception in Machines

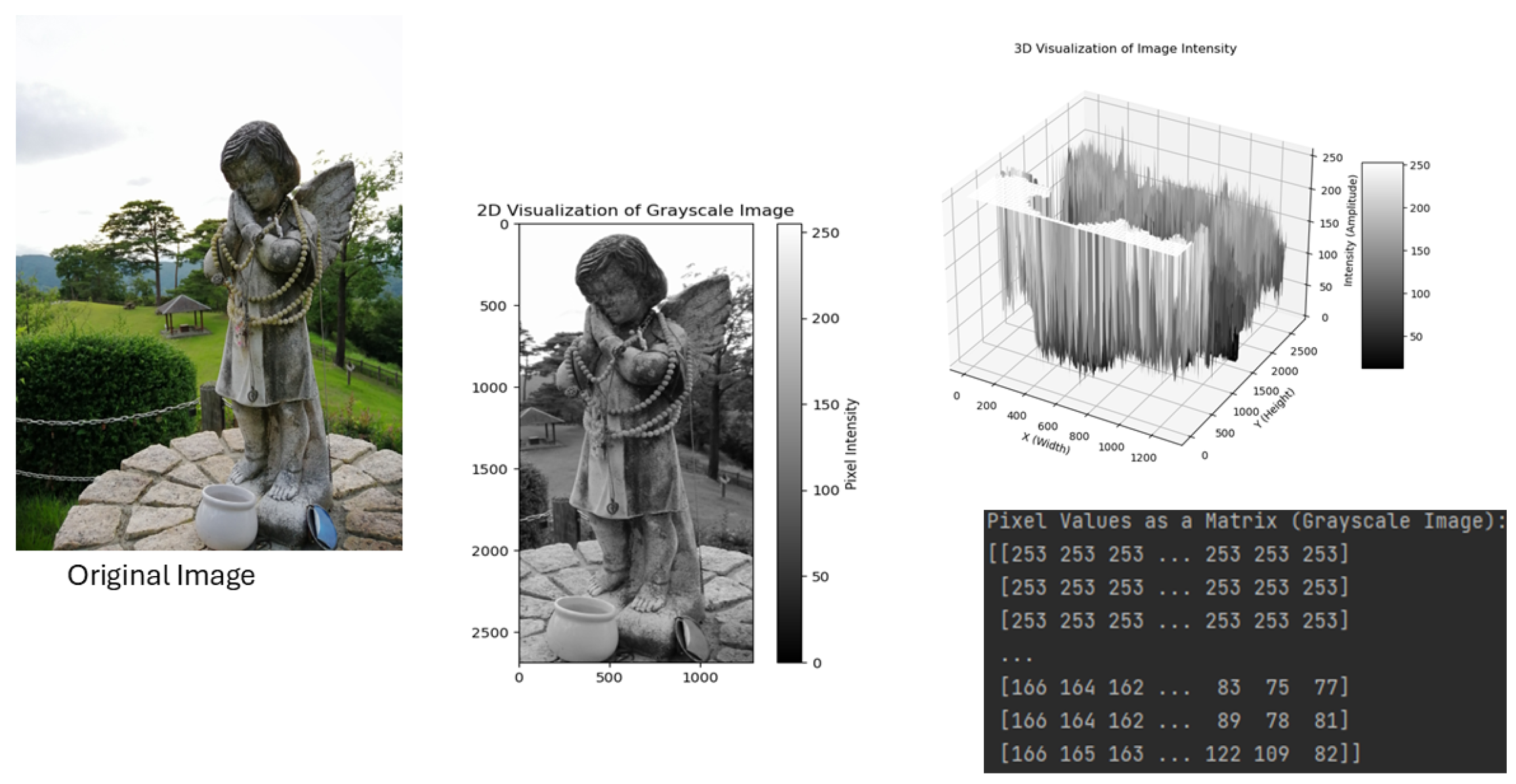

2.1. Foundational Techniques

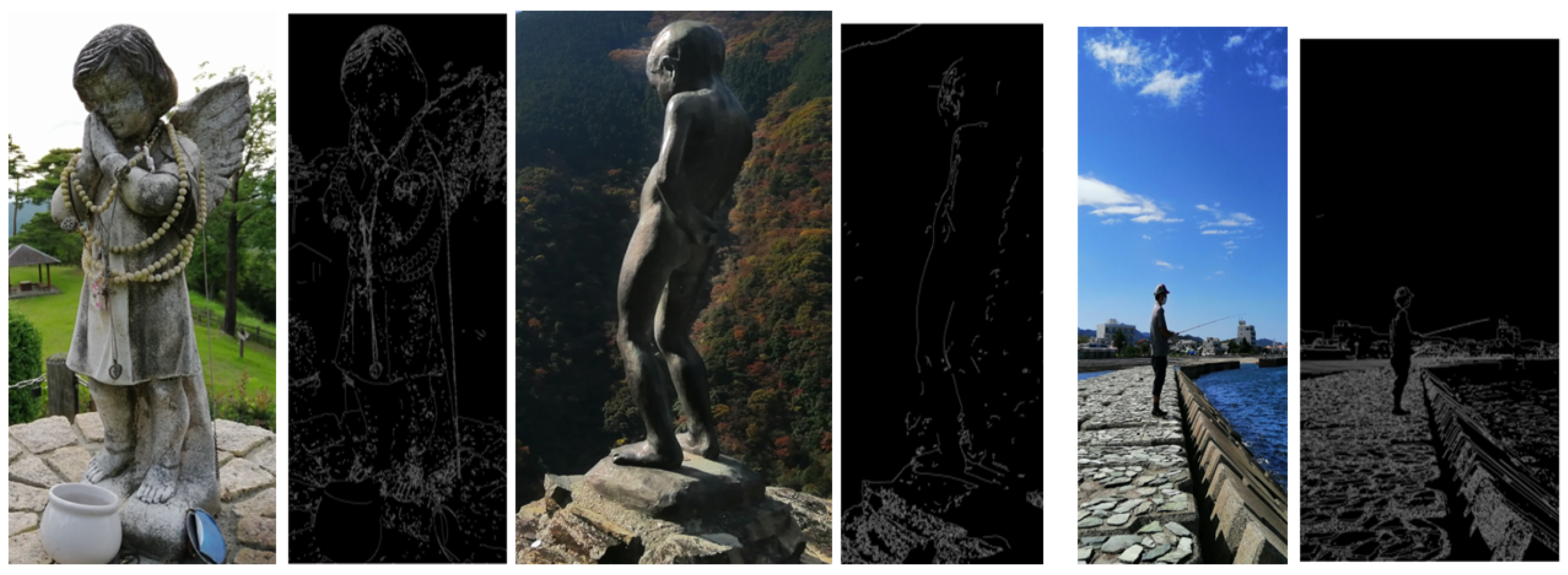

2.1.1. Edge Detection

- and are partial derivatives of the image function with respect to x and y. These derivatives measure how much the pixel intensity changes along the horizontal direction (x) and the vertical direction (y);

-

Specifically:

- –

- tells us how the image intensity changes as we move left or right.

- –

- tells us how the image intensity changes as we move up or down.

-

Gradient magnitude is computed by combining the horizontal and vertical gradients with this equation:This gives a measure of the overall change in intensity at each point. The higher the value of , the more likely that point is an edge.

- and measure image changes in x and y directions, combining them to calculate intensity at each pixel, aiding in detecting significant brightness or color changes.

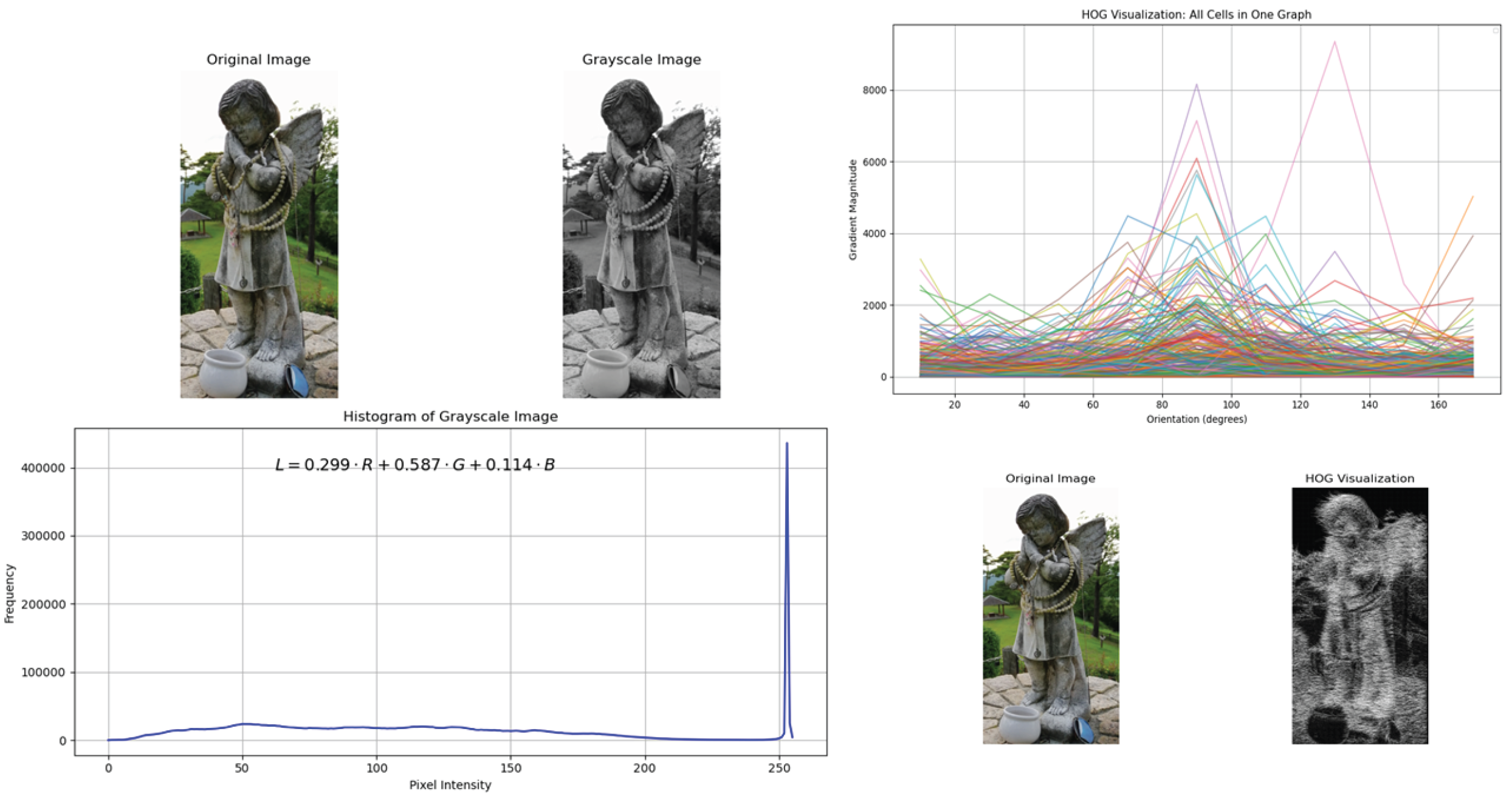

2.1.2. HOG (Histogram of Oriented Gradients)

2.1.3. Feature Extraction

- M is a 2x2 matrix of image gradients at a particular point in the image.

- refers to the determinant of the matrix M, which provides information about the area’s cornerness.

- is the sum of the diagonal elements of the matrix M, which indicates how much the pixel values change in different directions. A high trace value means there’s a significant intensity change

- k is a sensitivity factor, typically a small constant (e.g., ) that helps adjust the calculation. A smaller k results in more points being detected as corners, while a larger k makes the detection stricter, only identifying strong corners.

- The final value R is used to determine whether a pixel is a corner. A high value of R indicates that the point is a corner, while a lower value suggests the point is not.

2.2. Challenges in Computer Vision

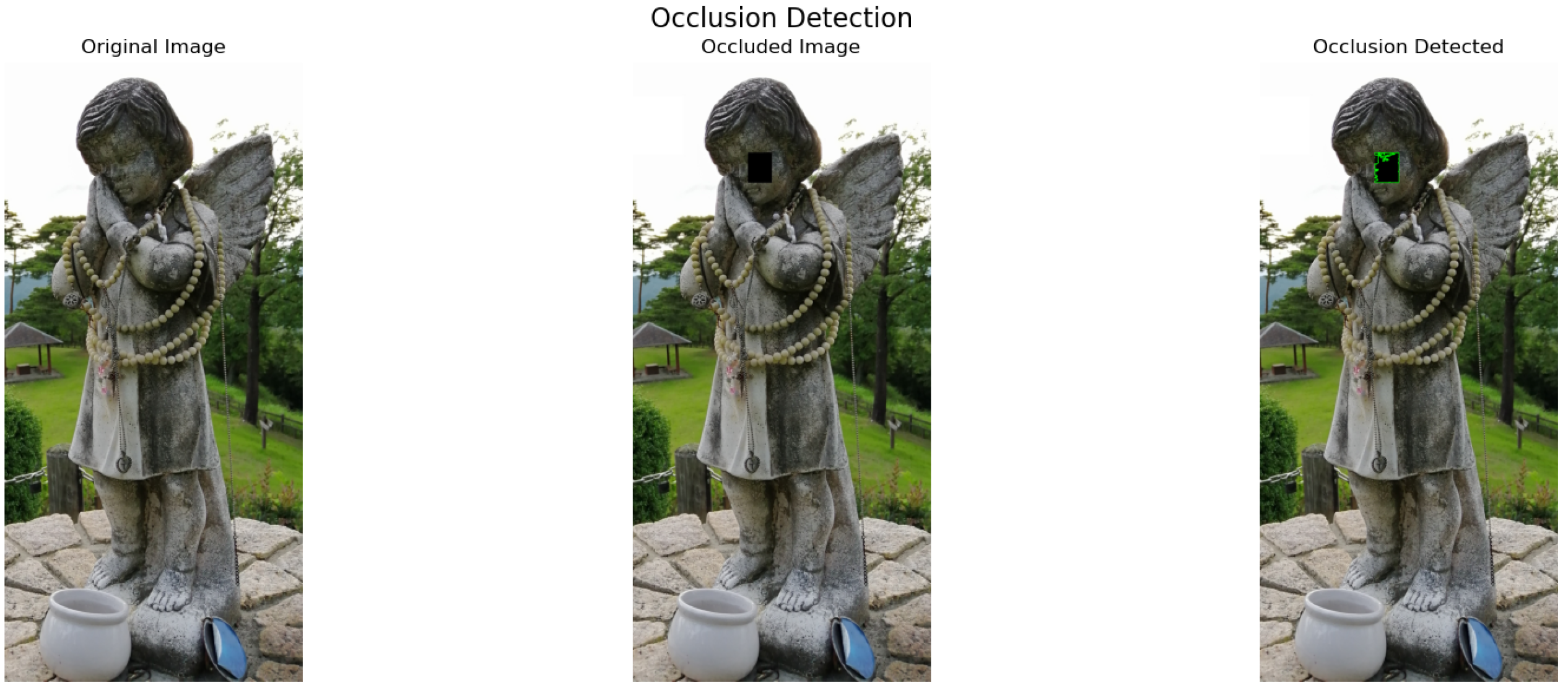

2.2.1. Occlusion

- In edge detection, gradients in occluded regions may be incomplete or distorted.

- In feature extraction, feature descriptors such as SIFT or HOG rely on the visible region and cannot account for missing parts.

2.2.2. Scalability

- Edge Detection: Computing gradients involves operations for each pixel, leading to complexity.

- HOG: Constructing histograms across overlapping blocks increases complexity to approximately , where B is the number of blocks.

-

Feature extraction and matching also need to be scale-invariant. For example, the similarity between two objects O and can be computed using a transformation-invariant distance d:where T is a transformation (e.g., scaling, rotation).Without proper scaling mechanisms, the distance d increases as the object size changes, leading to poor recognition results.

2.3. Additional Challenges in Foundational Techniques

- Noise sensitivity: Edge detection algorithms like Sobel or Canny are noise-sensitive. In real-world images, noise can lead to false edges being detected or important edges being missed.

- Weak boundaries: Some objects might have weak or fuzzy edges (e.g., transparent objects, low-contrast images), which makes it difficult for traditional edge detection methods to identify them.

- Limited to visible features: HOG works by detecting gradients (changes in intensity). However, objects with less clear edges or softer gradients (like a blurred object or one in shadow) are harder to detect.

- Sensitivity to pose variations: HOG features might be sensitive to the object’s orientation. If the object is rotated or skewed, the feature extraction process might miss important patterns, reducing accuracy.

- Feature mismatches: For complex objects, feature extraction methods may miss or incorrectly identify key features. For example, in an image with a cluttered background, it may be difficult to extract clean features due to the noise from the background.

- Feature diversity: Different objects require different features for recognition. For example, recognizing a dog may require detecting texture features (fur), while recognizing a car may require detecting edges and corners. Designing universal feature extraction methods that can work for all object types is a complex challenge.

3. Key algorithms and Advances

3.1. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)

-

Convolutional Layer: The convolutional layer is the core building block of a CNN. It applies convolution operations between the input data (e.g., an image) and learnable filters (kernels) to extract local features such as edges, textures, or patterns. Each filter slides across the input, computing dot products at every position, producing a feature map output. Multiple filters allow the model to learn diverse features. A convolution operation between an input X (e.g., an image) and a kernel (or filter) W produces a feature map F:Here:

- –

- X: Input matrix (image of size )

- –

- W: Filter (of size )

- –

- b: Bias term

- –

- : Coordinates of the output feature map

The convolution slides the filter over the input to compute dot products, capturing local patterns such as edges or textures. For instance, a 3×3 filter W is applied to a 5×5 image X. The result is a 3×3 feature map after valid padding. -

Pooling Layer: The pooling layer reduces the input feature maps’ spatial dimensions (height and width), retaining the most important information. It aggregates values within a small region, such as taking the maximum or average. Used to reduce spatial dimensions while retaining essential information. Two common types: Max Pooling, which takes the maximum value in a window, and Average Pooling, which takes the average value in a window. Given a window size , for max pooling:The proposed solution aims to decrease computational complexity, enhance network resilience to translations or distortions, and prevent overfitting by reducing the number of parameters.

-

Activation Layer: The activation layer applies a non-linear function to the feature maps. Without non-linearity, the model would behave like a linear system, incapable of learning complex patterns. Without activation layers, a neural network would essentially be a linear system. This is because the operations in convolutional and fully connected layers (matrix multiplications and summations) are inherently linear. Linear systems cannot represent complex patterns or relationships, regardless of how many layers are stacked. Common Activation Functions:

- –

- ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit): , the graph is a piecewise linear function with zero for negative inputs and linear for positive inputs, offering efficient computation, reducing vanishing gradient, and sparse activation,.

- –

- Sigmoid: , the S-shaped graph offers a probabilities interpretation and smooth gradients, but has avanishing gradient problem, slowing training, and is not zero-centered.

- –

- Tanh: , the S-shaped curve offers advantages such as zero-centered optimization and a steeper gradient than a sigmoid, but also suffers from the vanishing gradient problem for large .

The activation layer is crucial for introducing the non-linear capabilities of CNNs, enabling them to learn and model complex data relationships. -

Fully Connected Layer: After convolution and pooling, the learned feature maps are flattened and passed through one or more fully connected layers:Here, x is the flattened input, W is a weight matrix, and b is a bias vector. The fully connected layer connects neurons in one layer to the next, enabling predictions based on learned features. It aggregates features from previous layers and maps them to output classes or regression values at the network’s end.

-

Loss Function and Backpropagation: The loss function and backpropagation are crucial in training neural networks. This enables the network to optimize its parameters (weights and biases) to reduce prediction errors. The loss function[37] calculates the discrepancy between the predicted outputs () and true labels (y), guiding the optimization process. Common loss functions include Mean Squared Error (MSE) for regression tasks, defined as:and Binary Cross-Entropy (BCE) for binary classification tasks:The loss function also incorporates regularization terms, like L1 and L2 regularization, which prevent overfitting by penalizing large weights. The optimization goal is to minimize the loss by adjusting network parameters using methods like Gradient Descent. Backpropagation is the process that computes the gradients of the loss function with respect to the network’s parameters. This is achieved by applying the chain rule of calculus, where gradients are propagated backward through the network, layer by layer. For each layer, the loss gradient with respect to its weights and biases is calculated and used to update the parameters. For example, for a weight W at the output layer, the update rule is:where is the learning rate. Key challenges in backpropagation include vanishing gradients, where gradients become too small for deep networks, and exploding gradients, where gradients grow too large, destabilizing the training process. Solutions like ReLU activation functions and gradient clipping help address these issues. Loss functions and backpropagation allow neural networks to learn complex patterns and improve performance in tasks like image recognition, classification, and more.

-

Output Layer: In a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), the output layer generates the final predictions based on the features learned by previous layers. Classification tasks typically use the softmax function to convert raw scores (logits) into probabilities. Mathematically, for C output classes, the probability for class j is given by the softmax equation:where is the raw score for class j, h is the output from the last hidden layer, is the weight for class j, and is the bias. The predicted class is the one with the highest probability, which is computed as . For example, in a 3-class classification problem, the output layer produces a vector of probabilities, and the class with the highest probability is selected as the predicted label. In the example of a CNN for image classification into 3 classes (cat, dog, and bird), the output layer has 3 neurons, one for each class. After processing an image, the network produces a vector of features, , which is passed through the output layer. The raw scores (logits) for each class are computed as:These logits are then converted into probabilities using the softmax function:The predicted class has the highest probability, class "cat" with a probability of . Thus, the CNN classifies the input image as "cat".

3.2. Object Detection

3.3. Semantic Segmentation

- N is the number of pixels,

- C is the number of classes,

- is the ground truth label for class c at pixel i (1 if the pixel belongs to class c, 0 otherwise),

- is the predicted probability of class c at pixel i.

3.4. Generative Models

3.4.1. Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)

3.4.2. Variational Autoencoders (VAEs)

3.4.3. Gaussian Mixture Models (GMMs)

- is the weight of the i-th Gaussian component,

- is the Gaussian distribution with mean and covariance ,

- K is the number of Gaussian components.

3.5. Vision Transformers (ViTs)

3.6. Tradition Methods vs Deep learning based Methods

4. Computer Vision Applications

4.1. Medical Imaging

4.2. Autonomous Driving and Robotics

4.3. Sports and Other Areas

5. Emerging Trends and Future Prospects

5.1. Trends

- AI-powered and Deep Learning Advancements: Deep learning, particularly with Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), remains a dominant approach in computer vision, but innovations like Vision Transformers (ViTs) are gaining traction. These models, which leverage the self-attention mechanism, show promising results in image classification and object detection tasks, challenging the traditional CNN-based architectures. As AI models become more efficient and capable of handling vast datasets [45], the accuracy and robustness of computer vision systems will continue to improve.

- Edge Computing and Real-Time Processing: With the rise of edge computing[46], computer vision is increasingly being deployed in real-time applications where data is processed on local devices rather on cloud-based systems. This trend is particularly important for applications requiring low-latency decision-making, such as autonomous driving, robotics, and augmented reality (AR). Edge devices like mobile phones, drones, and wearables increasingly integrate computer vision algorithms to process data locally, enabling faster response times and enhanced privacy.

- Explainability and Fairness in AI: As AI models, particularly in computer vision, are being used in high-stakes areas such as healthcare, security, and law enforcement, the demand for explainable AI (XAI)[47] is increasing. Researchers are working on methods to make the decision-making process of computer vision models more transparent, allowing humans to understand and trust these systems. Ensuring fairness and avoiding biases in AI models is also a growing concern, with efforts focusing on developing more inclusive datasets and techniques that reduce discrimination in visual data processing.

- 3D Vision and Spatial Understanding: The future of computer vision is moving towards enhanced 3D vision[47], which involves recognizing objects and understanding their spatial relationships in three-dimensional space. This includes advancements in depth sensing, stereo vision, and LiDAR technologies, which are increasingly used in autonomous driving, augmented reality, and robotics. 3D vision will allow systems to understand environments more comprehensively, enabling more complex interactions and precise predictions in dynamic environments.

5.2. Future Prospects

- Multimodal Learning and Cross-Modal Systems: Another emerging trend is the development of multimodal learning systems[48], which combine data from multiple sources, such as visual, auditory, and textual information, to enhance computer vision models. For example, integrating vision with natural language processing (NLP)[49] allows for systems that can understand and generate descriptions of images (e.g., image captioning) or assist in tasks like visual question answering (VQA). This trend could lead to more holistic AI systems that can understand and interact with the world in a way that is closer to human perception.

- Synthetic Data and Augmentation: As obtaining large, annotated datasets for training computer vision models can be time-consuming and costly, synthetic data generation [50] is becoming a popular alternative. Synthetic data is generated through simulations, rendering, or generative models like GANs (Generative Adversarial Networks). These methods can create diverse, labeled data for tasks like object detection and scene understanding, enhancing model training without needing real-world data. This could be especially beneficial in domains like autonomous driving, where real-world data collection is expensive and time-consuming.

- AI in Healthcare and Diagnostics: Computer vision’s role in healthcare continues to expand with advancements in medical image analysis. AI models are increasingly capable of detecting early signs of diseases[51], from detecting tumors in radiology images to identifying retinal diseases from eye scans. As the quality of these AI-driven diagnostic tools improves, they will be used more extensively in clinical settings to assist doctors, reduce human error, and provide faster diagnoses, leading to better patient outcomes.

- Augmented Reality (AR) and Virtual Reality (VR): Computer vision is integral to developing AR and VR technologies. As AR and VR [52] devices become more widely adopted in industries such as entertainment, education, and retail, computer vision will enable more interactive and immersive experiences. For example, real-time object recognition and tracking in AR will allow users to interact with the virtual world overlaid on their physical surroundings. At the same time, VR systems will use computer vision to create more realistic simulations and improve user experiences.

- Privacy-Preserving Computer Vision: With increasing concerns about privacy, there is a growing interest in privacy-preserving[53] computer vision techniques. Federated learning, for instance, allows models to be trained across decentralized devices without raw data ever leaving the device, preserving privacy. This will be crucial in applications such as surveillance, healthcare, and personal assistants, where sensitive information is handled.

6. Discussions

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Q&A: What is Intelligence? Available online: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/news/articles/2020/10/qa–what-is-intelligence#:~:text=Intelligence%20can%20be%20defined%20as,for%20their%20survival%20and%20reproduction. (accessed on 27 June 2024).

- Russell, S., & Norvig, P. (2020). Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach (4th ed.). Pearson. (accessed on 10 January 2020).

- Turing, A. M. (1950). Computing machinery and intelligence. Mind, 59(236), 433–460. [CrossRef]

- Enoch, J., McDonald, L., Jones, L., Jones, P. R., & Crabb, D. P. (2019). Evaluating whether sight is the most valued sense. JAMA Ophthalmology, 137(11), 1317–1320. [CrossRef]

- Szeliski, R. (2010). Computer Vision: Algorithms and Applications. Springer London. https://books.google.co.jp/books?id=bXzAlkODwa8C.

- Schwiegerling, J. (2004). Field Guide to Visual and Ophthalmic Optics. SPIE. [CrossRef]

- Perera Molligoda Arachchige, A. S., & Svet, A. (2021). Integrating artificial intelligence into radiology practice: undergraduate students’ perspective. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, 48(13), 4133–4135. [CrossRef]

- Chen, R., & Karungaru, S. G. (2022). Multi-modal feature fusion network for breast lesions segmentation. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Intelligent Unmanned Systems (pp. 1–6).

- Nsinga, R., Karungaru, S., & Terada, K. (2022). Auto-differentiated fixed point notation on low-powered hardware acceleration. Journal of Signal Processing, 26(5), 131–140. [CrossRef]

- Constant, J. N. (1991). Fundamentals of Strategic Weapons: Offense and Defense Systems. Springer. ISBN: 9401501572, ISBN13: 9789401501576.

- Karungaru, S., Tsuji, R., & Terada, K. (2022). Driving assistance: Pedestrians and bicycles accident risk estimation using onboard front camera. International Journal of Intelligent Transportation Systems Research, 20, 768–777. [CrossRef]

- Wiseman, Y. (2022). Autonomous vehicles. In Research anthology on cross-disciplinary designs and applications of automation (pp. 878–889). IGI Global.

- Gonzalez, R. C. (2009). Digital Image Processing. Pearson Education India.

- Menconero, Sofia. (2023). Image Processing for Knowledge and Comparison of Piranesi’s Carceri Editions. In D. Villa & F. Zuccoli (Eds.), Proceedings of the 3rd International and Interdisciplinary Conference on Image and Imagination (pp. 1–10). Springer International Publishing. Cham. ISBN: 978-3-031-25906-7.

- Marr, D., & Hildreth, E. (1980). Theory of edge detection. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B. Biological Sciences, 207(1167), 187–217.

- Bao, P., Zhang, L., & Wu, X. (2005). Canny edge detection enhancement by scale multiplication. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 27(9), 1485–1490.

- Wang, X., Han, T. X., & Yan, S. (2009, September). An HOG-LBP human detector with partial occlusion handling. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE 12th International Conference on Computer Vision (pp. 32–39). IEEE.

- Kanopoulos, N., Vasanthavada, N., & Baker, R. L. (1988). Design of an image edge detection filter using the Sobel operator. IEEE Journal of Solid-State Circuits, 23(2), 358–367. [CrossRef]

- Noble, W. S. (2006). What is a support vector machine? Nature Biotechnology, 24(12), 1565–1567.

- Guyon, I., Gunn, S., Nikravesh, M., & Zadeh, L. A. (Eds.). (2008). Feature extraction: Foundations and applications (Vol. 207). Springer.

- Sánchez, J., Monzón, N., & Salgado De La Nuez, A. (2018). An analysis and implementation of the Harris corner detector. Image Processing On Line. [CrossRef]

- Andrews, L. F. (1972). The six keys to normal occlusion. American Journal of Orthodontics, 62(3), 296–309. [CrossRef]

- Bondi, A. B. (2000, September). Characteristics of scalability and their impact on performance. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Workshop on Software and Performance (pp. 195–203).

- Wu, Y. C., & Feng, J. W. (2018). Development and application of artificial neural network. Wireless Personal Communications, 102, 1645–1656.

- McCulloch, W. S., & Pitts, W. (1943). A logical calculus of the ideas immanent in nervous activity. The Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics, 5, 115–133. [CrossRef]

- Taud, H., & Mas, J. F. (2018). Multilayer perceptron (MLP). In Geomatic Approaches for Modeling Land Change Scenarios (pp. 451–455).

- Wu, J. (2017). Introduction to convolutional neural networks. National Key Lab for Novel Software Technology, Nanjing University, China, 5(23), 495.

- Alom, M. Z., Taha, T. M., Yakopcic, C., Westberg, S., Sidike, P., Nasrin, M. S., …, & Asari, V. K. (2018). The history began from AlexNet: A comprehensive survey on deep learning approaches. arXiv preprint arXiv:1803.01164.

- Deng, J., Dong, W., Socher, R., Li, L. J., Li, K., & Fei-Fei, L. (2009, June). ImageNet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (pp. 248–255). IEEE.

- Wang, L., Guo, S., Huang, W., & Qiao, Y. (2015). Places205-VGGNet models for scene recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:1508.01667.

- Targ, S., Almeida, D., & Lyman, K. (2016). ResNet in ResNet: Generalizing residual architectures. arXiv preprint arXiv:1603.08029.

- Szegedy, C., Ioffe, S., Vanhoucke, V., & Alemi, A. (2017, February). Inception-v4, Inception-ResNet and the impact of residual connections on learning. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (Vol. 31, No. 1).

- Tan, M., & Le, Q. (2019, May). EfficientNet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning (pp. 6105–6114). PMLR.

- Zhou, D., Kang, B., Jin, X., Yang, L., Lian, X., Jiang, Z., …, & Feng, J. (2021). DeepViT: Towards deeper vision transformer. arXiv preprint arXiv:2103.11886.

- Brynjolfsson, E., Li, D., & Raymond, L. R. (2023). Generative AI at work (No. w31161). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y., & Hinton, G. (2015). Deep learning. Nature, 521(7553), 436–444.

- Christoffersen, P., & Jacobs, K. (2004). The importance of the loss function in option valuation. Journal of Financial Economics, 72(2), 291–318. [CrossRef]

- He, K., Gkioxari, G., Dollár, P., & Girshick, R. (2017). Mask R-CNN. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (pp. 2961–2969).

- Redmon, J., Divvala, S. K., Girshick, R. B., & Farhadi, A. (2015). You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. CoRR, abs/1506.02640. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/1506.02640.

- Girshick, R. B. (2015). Fast R-CNN. CoRR, abs/1504.08083. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/1504.08083.

- Ren, S., He, K., Girshick, R. B., & Sun, J. (2015). Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. CoRR, abs/1506.01497. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/1506.01497.

- Guo, Y., Liu, Y., Georgiou, T., & Lew, M. S. (2018). A review of semantic segmentation using deep neural networks. International Journal of Multimedia Information Retrieval, 7, 87–93. [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O., Fischer, P., & Brox, T. (2015). U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention–MICCAI 2015: 18th International Conference, Munich, Germany,.

- Thomas, G., Gade, R., Moeslund, T. B., Carr, P., & Hilton, A. (2017). Computer vision for sports: Current applications and research topics. Computer Vision and Image Understanding, 159, 3–18. [CrossRef]

- Kirillov, A., Mintun, E., Ravi, N., Mao, H., Rolland, C., Gustafson, L., Xiao, T., Whitehead, S., Berg, A. C., Lo, W.-Y., Dollár, P., & Girshick, R. (2023). Segment Anything. arXiv:2304.02643. [CrossRef]

- Cao, K., Liu, Y., Meng, G., & Sun, Q. (2020). An overview on edge computing research. IEEE Access, 8, 85714–85728. [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, R., Dave, D., Naik, H., Singhal, S., Omer, R., Patel, P., ... & Ranjan, R. (2023). Explainable AI (XAI): Core ideas, techniques, and solutions. ACM Computing Surveys, 55(9), 1–33. [CrossRef]

- Bouchey, B., Castek, J., & Thygeson, J. (2021). Multimodal learning. In Innovative Learning Environments in STEM Higher Education: Opportunities, Challenges, and Looking Forward(pp. 35-54).

- Chowdhary, K., & Chowdhary, K. R. (2020). Natural language processing. Fundamentals of artificial intelligence, 603-649.

- Figueira, A., & Vaz, B. (2022). Survey on synthetic data generation, evaluation methods and GANs. Mathematics, 10(15), 2733.

- Thevenot, J., López, M. B., & Hadid, A. (2017). A survey on computer vision for assistive medical diagnosis from faces. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics, 22(5), 1497-1511. [CrossRef]

- Jung, T., & tom Dieck, M. C. (2018). Augmented reality and virtual reality. Ujedinjeno Kraljevstvo: Springer International Publishing AG.

- Ren, Z., Lee, Y. J., & Ryoo, M. S. (2018). Learning to anonymize faces for privacy preserving action detection. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV) (pp. 620-636).

| Aspect | Traditional Methods | Deep Learning-Based Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Feature Extraction | Handcrafted features such as SIFT (Scale-Invariant Feature Transform) and HOG (Histogram of Oriented Gradients), requiring manual selection and tuning of features based on domain knowledge. | Features are automatically learned from data through neural network architectures, such as CNNs (Convolutional Neural Networks), which extract relevant features directly from images without human intervention. |

| Performance | Traditional methods perform well in simpler tasks with smaller datasets, where problems can be clearly defined with rules or heuristics. They struggle with more complex tasks and require significant manual feature engineering. | Deep learning-based methods excel in handling more complex tasks, especially in large-scale environments or where data has high variation. These methods can tackle intricate patterns and dense environments with superior accuracy. |

| Robustness | Traditional methods are highly sensitive to noise, lighting variations, scale, and perspective. They rely on fixed features, which may not generalize well to different conditions. | Deep learning-based methods, such as CNNs, are more robust to noise, changes in scale, and perspective, as they learn to adapt from large datasets and generalize well to unseen data. Advanced architectures and data augmentation techniques improve robustness. |

| Data Requirements | Traditional methods typically require less data as they depend on handcrafted features, which can work with smaller datasets. These methods perform well in tasks with limited data. | Deep learning-based methods require large amounts of labeled data to effectively train models. A significant amount of data is needed to learn complex representations and relationships, especially for tasks like image classification and object detection. |

| Examples | Examples include edge detection (Canny, Sobel), feature matching (SIFT, ORB), and histogram-based methods (e.g., color histograms for object recognition). These are applied to simpler tasks like basic image processing and feature-based matching. | Examples include image classification (CNNs), object detection (YOLO, Faster R-CNN), and semantic segmentation (U-Net). These are used for more complex tasks like autonomous driving, facial recognition, and medical imaging. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).