Submitted:

25 March 2025

Posted:

25 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

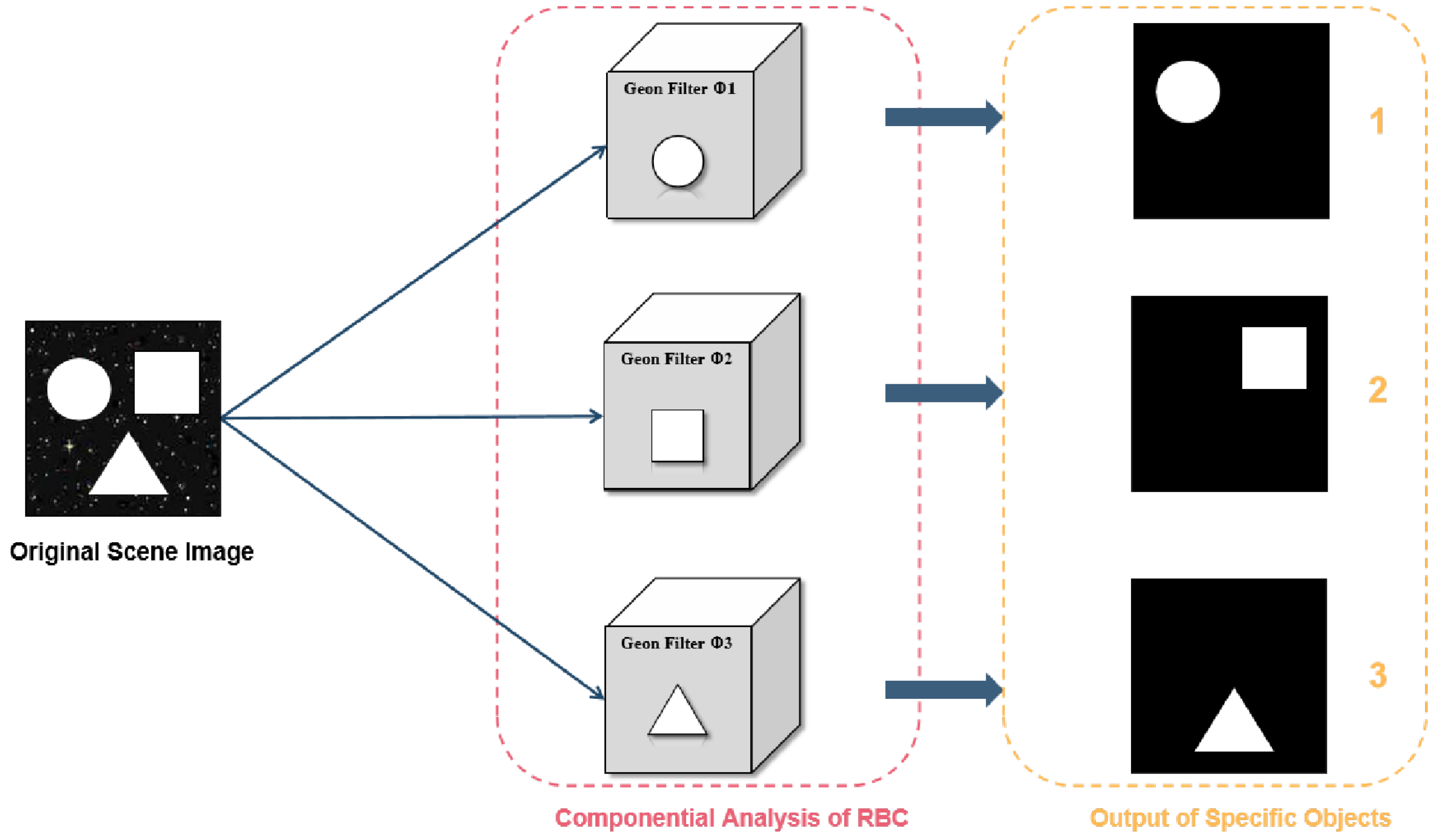

1.1. RBC (Recognition-by-Components) Framework Based on Marr

- Computational level: Primitives as the minimal units of visual representation;

- Algorithmic level: Deep learning simulates hierarchical feature extraction;

- Implementation level: Weight optimization in neural networks ( , ) corresponds to synaptic plasticity.

- Constructing complex objects: By combining and arranging different basic geons, various complex visual objects can be created, offering high flexibility.

- Providing recognition cues: Basic geons not only form the shape and structure of objects but also provide key cues for object recognition. When an observer sees an object, they first identify the basic geons of the object, and then recognize the object based on the combination and arrangement of these elements.

- Supporting rapid recognition: Due to the limited number and types of basic geons, and the relatively fixed ways they can be combined, the visual system can quickly recognize objects, making this process highly automated.

1.2. Deep Learning-Based CV Scholars

1.3. Psychology, Neuroscience, and Other Fields

| Theoretical Framework | Definition of Geons | Dynamic Adaptability | Noise Robustness | Improvements in This Paper |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBC (Biederman) | Fixed 36 geometric shapes | Low | Not involved | Adaptive learning of geons |

| I-Theory | Gradual abstraction of features | Medium | Partial | Incorporation of sparse coding |

| DeepPrimitive | Data-driven action segmentation | High | Data-dependent | Cross-modal bio-inspired |

2. Materials and Methods

- Computational level: Consistent with RBC theory, primitives serve as minimal units of visual representation.

- Algorithmic level: Deep learning simulates hierarchical feature extraction, where U-Net’s encoder→decoder architecture corresponds to human V1→IT cortical pathways.

- Implementational level: Neural network weight optimization ( , ) mirrors synaptic plasticity, partially validating Zhang et al.’s visual cortical activity modulation [69].

3. Experiments and Results

3.1. Datasheet

3.2. Evaluation Indicators

-

SSIM [76]Based on the multi-channel characteristics of the human visual system, its perceptual consistency metric is defined as:By comparing brightness, contrast, and structural similarity, visual perceptual consistency is quantified within the range of [0, 1].

-

PSNR [77]As a frequency domain fidelity benchmark, its calculation model is:Here, represents the maximum pixel value of the image (e.g., 255 for an 8-bit image). This metric objectively reflects image fidelity by measuring the ratio of the maximum signal power to the distortion power.

-

MSE [78]Defined as a convergence verification metric for the optimization process:PSNR provides a global distortion benchmark, SSIM characterizes perceptual consistency, and MSE ensures the verification of algorithm convergence, together forming a complementary evaluation system.The experimental section will combine quantitative analysis with visual comparisons to ensure the completeness of the evaluation conclusions.

3.3. Experimental Setup Implementation Details

3.4. Results

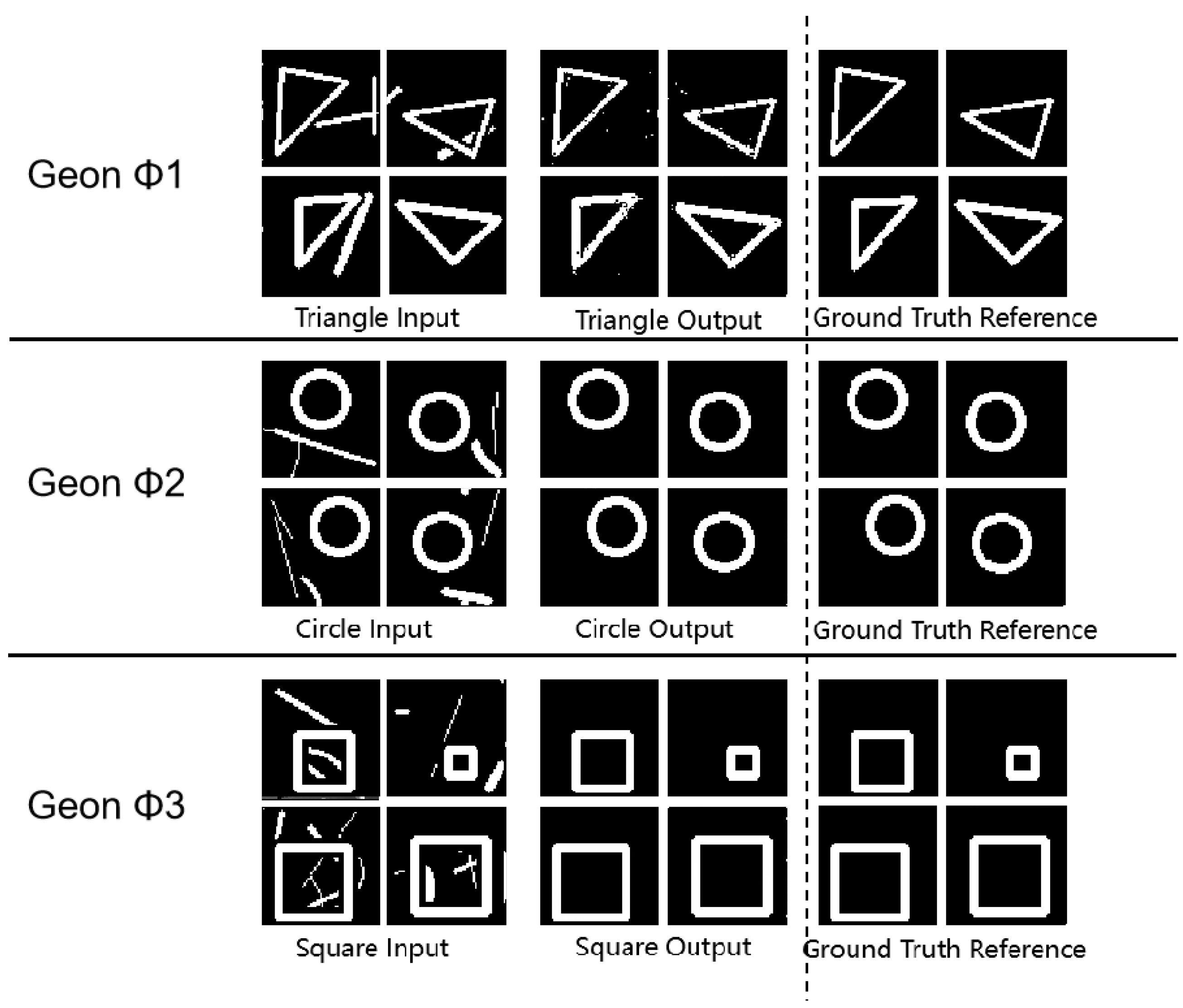

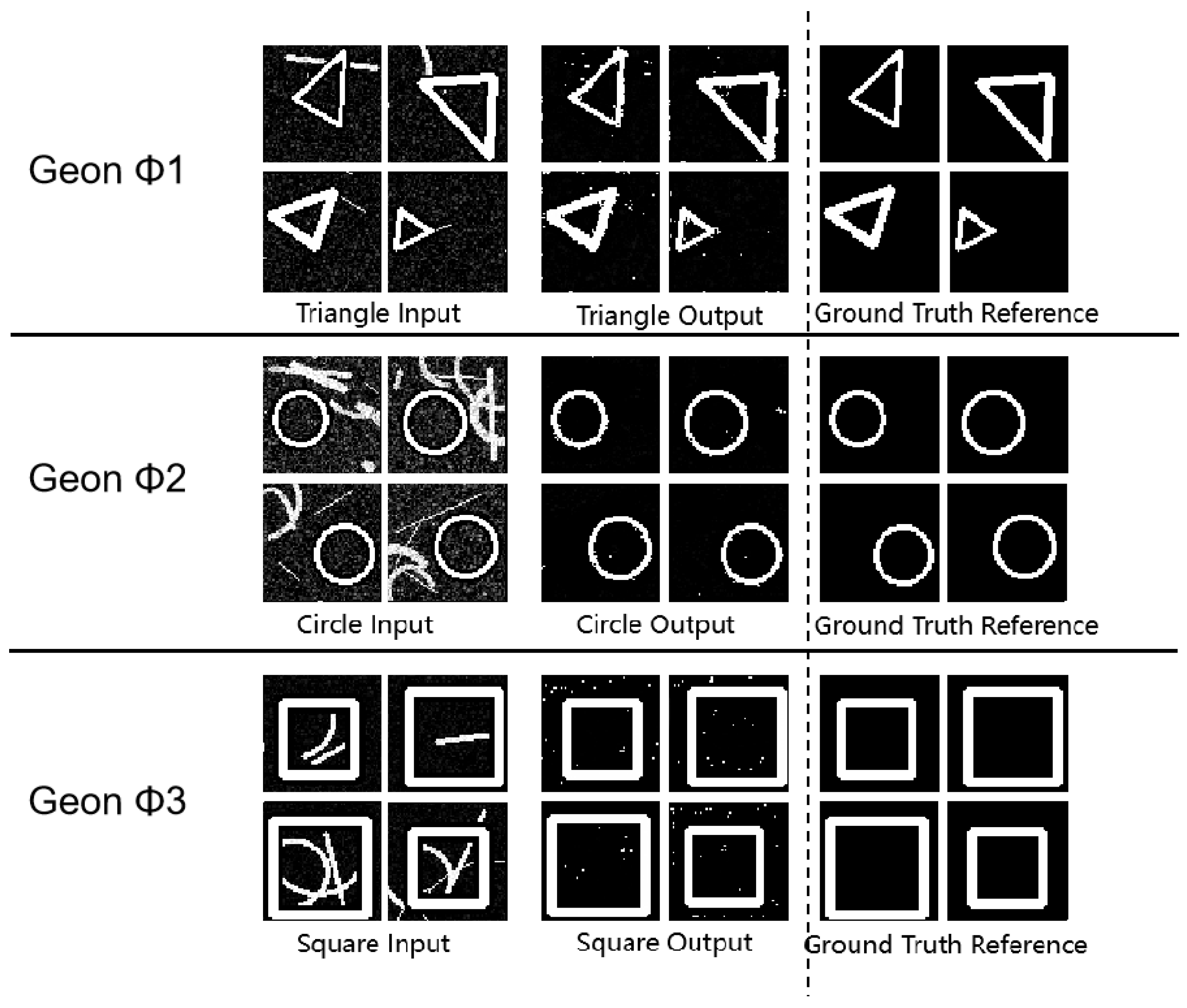

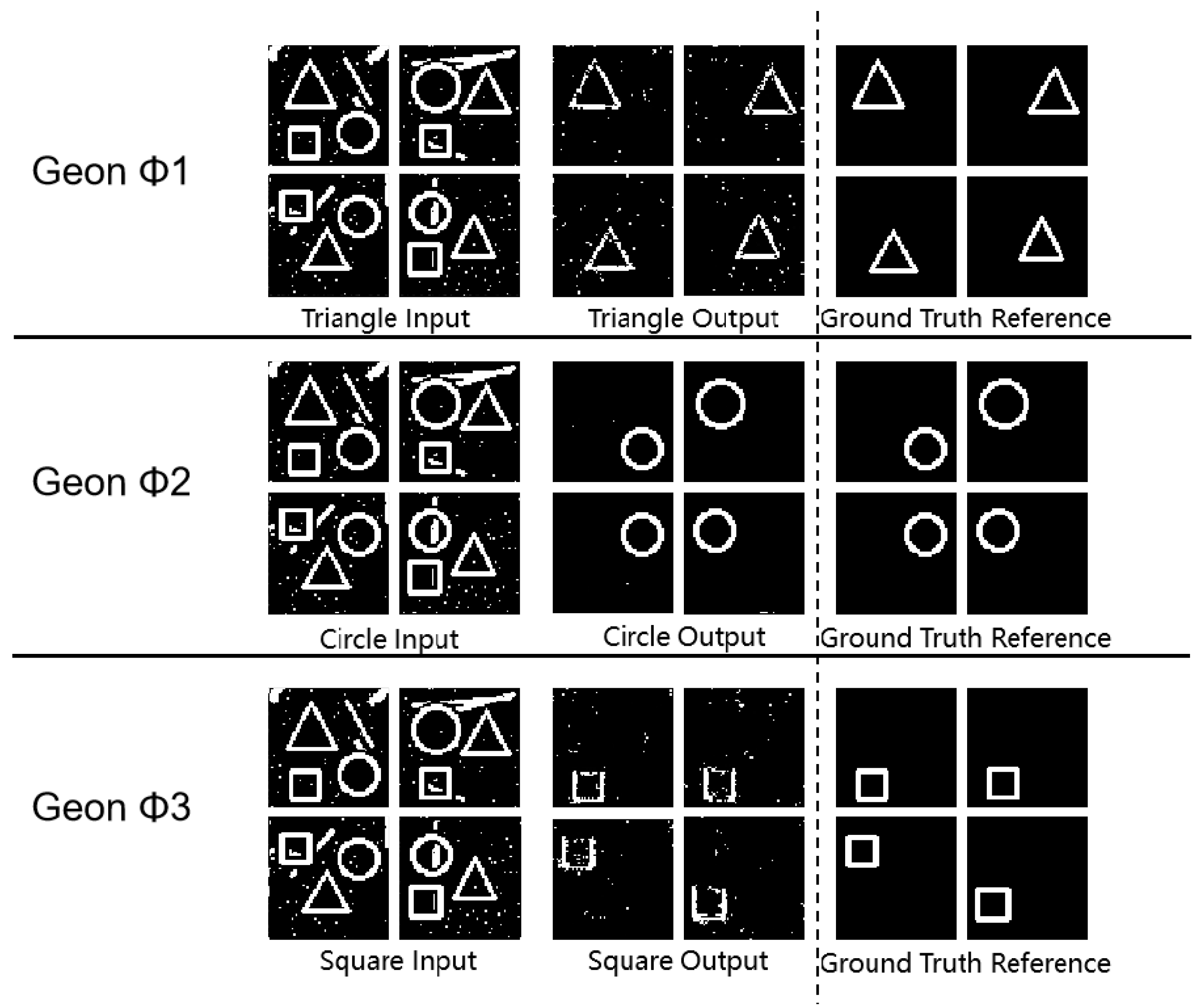

3.4.1. Fundamental Detection.

| Geon | SSIM | PSNR | MSE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triangle | 0.93 | 59.14 | 0.10 |

| Circle | 0.99 | 54.64 | 0.23 |

| Square | 0.98 | 58.40 | 0.11 |

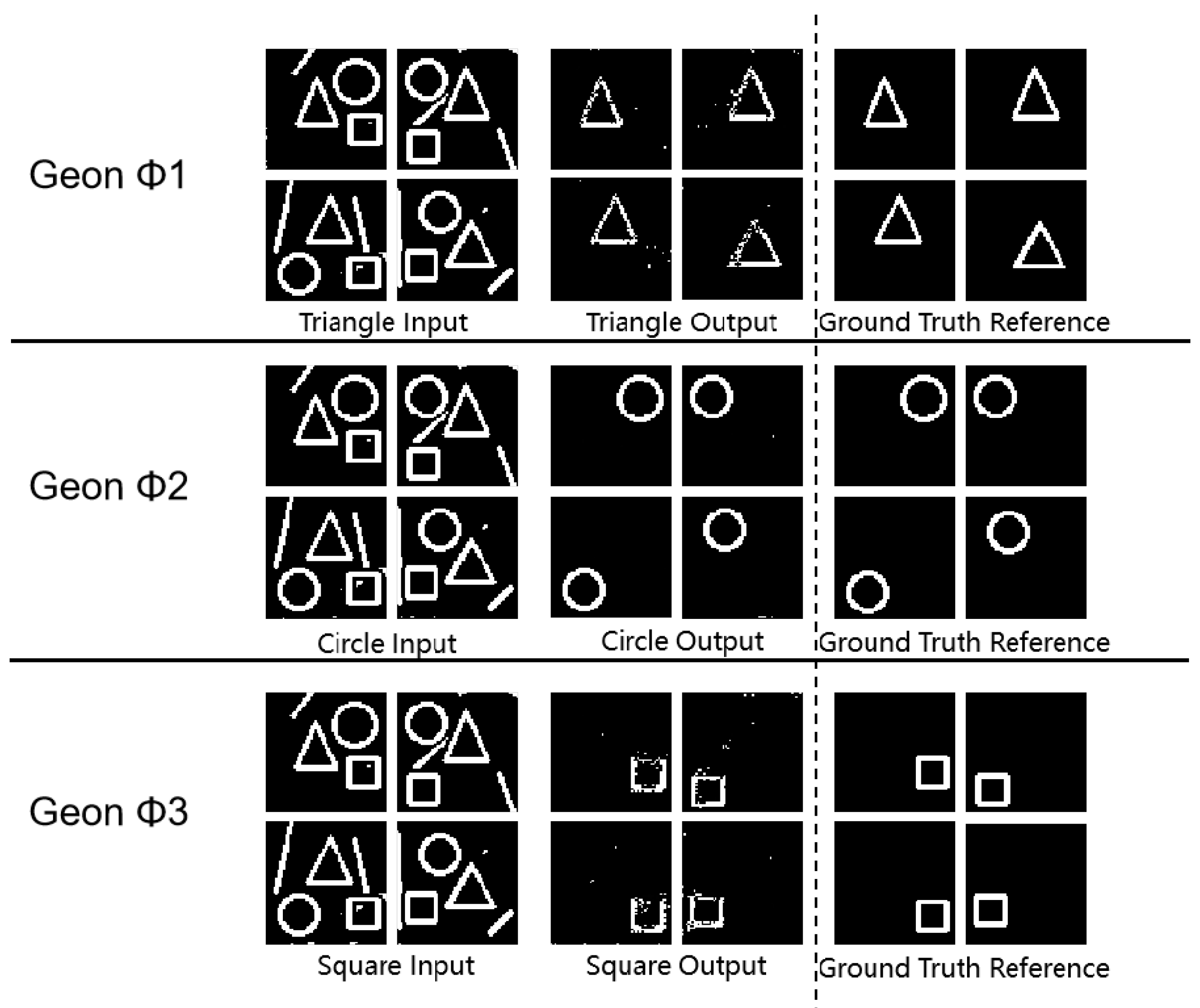

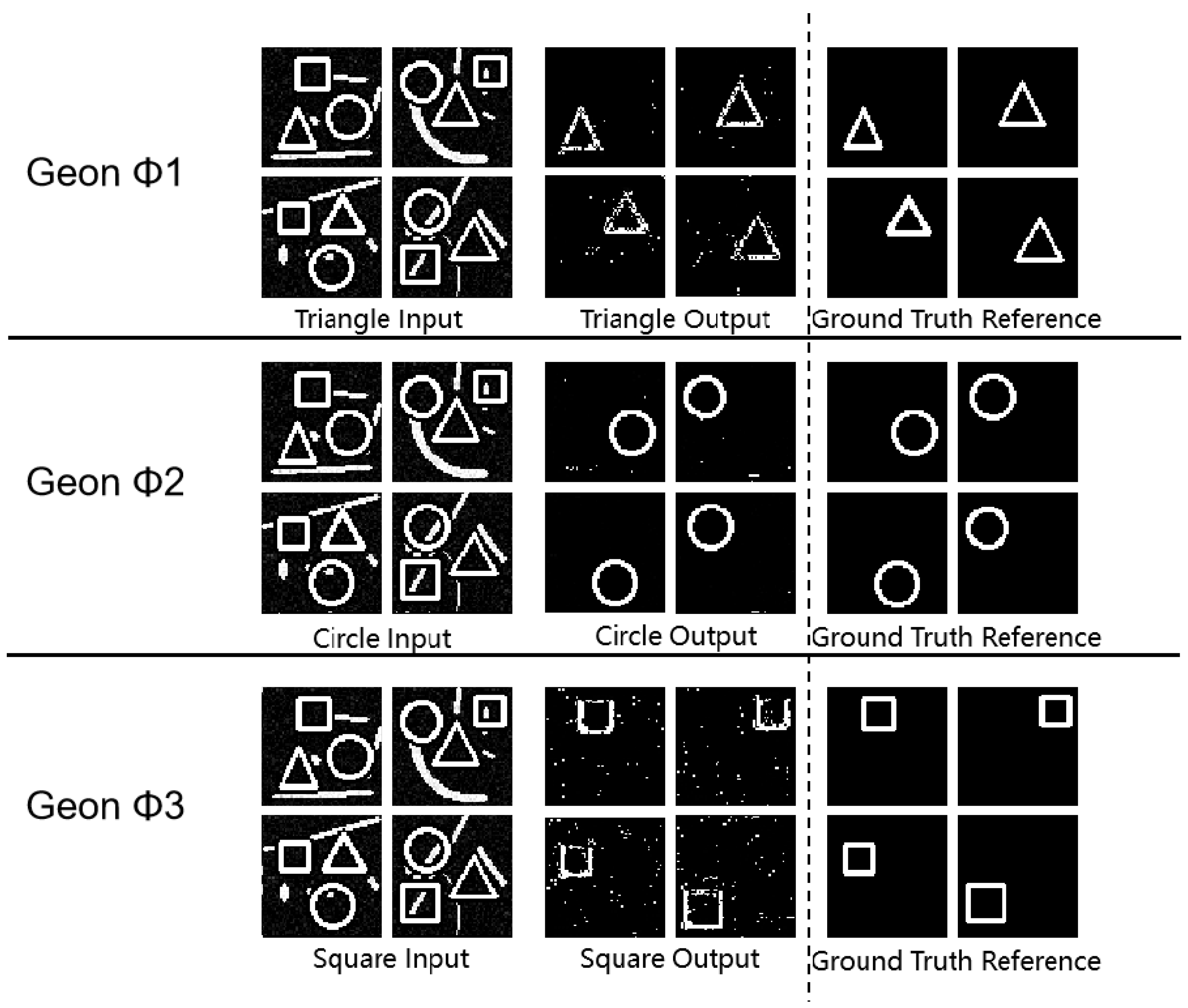

3.4.2. Geon Separation Detection

| Geon | SSIM | PSNR | MSE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triangle | 0.88 | 62.34 | 0.05 |

| Circle | 0.99 | 60.05 | 0.06 |

| Square | 0.80 | 58.88 | 0.10 |

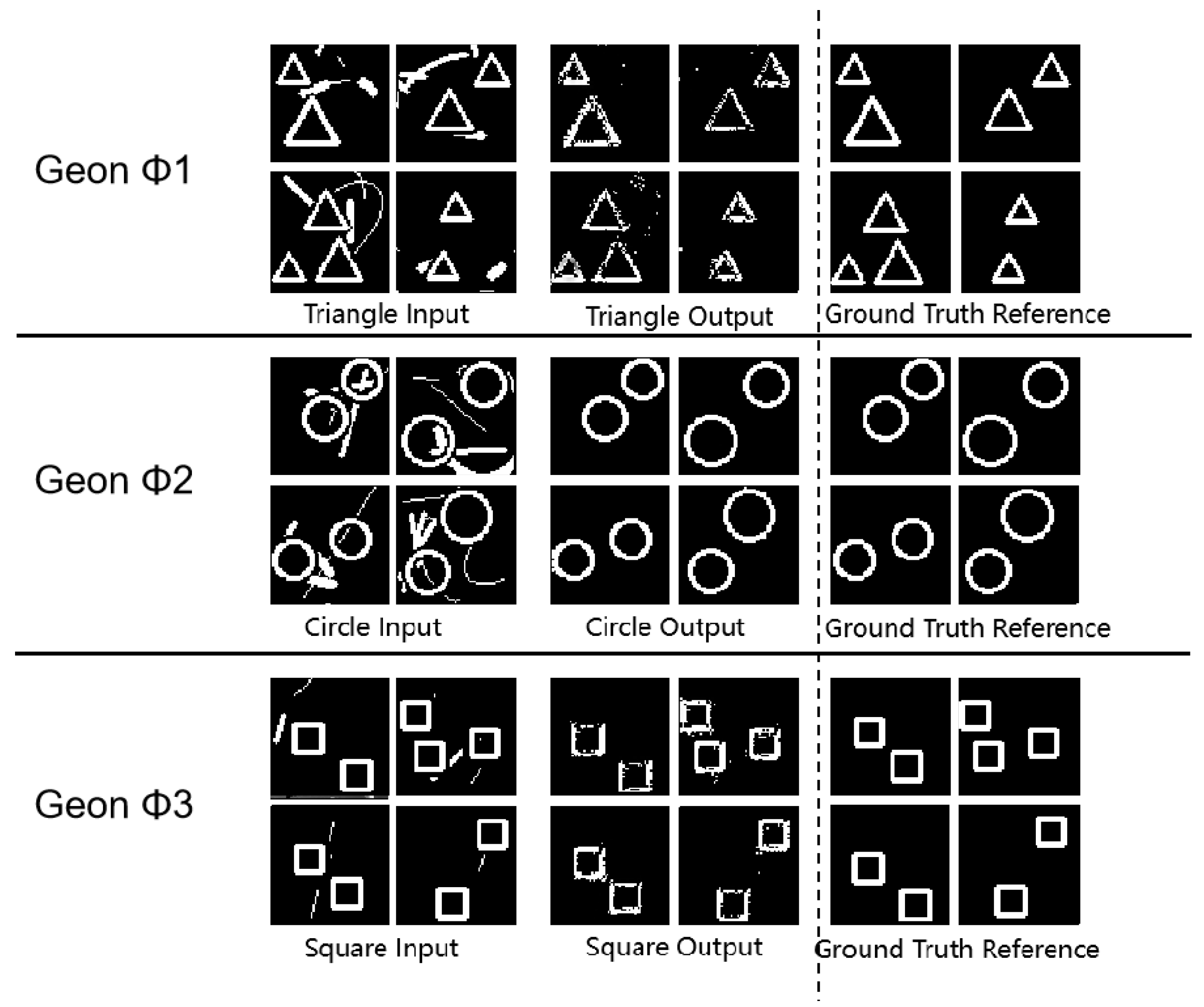

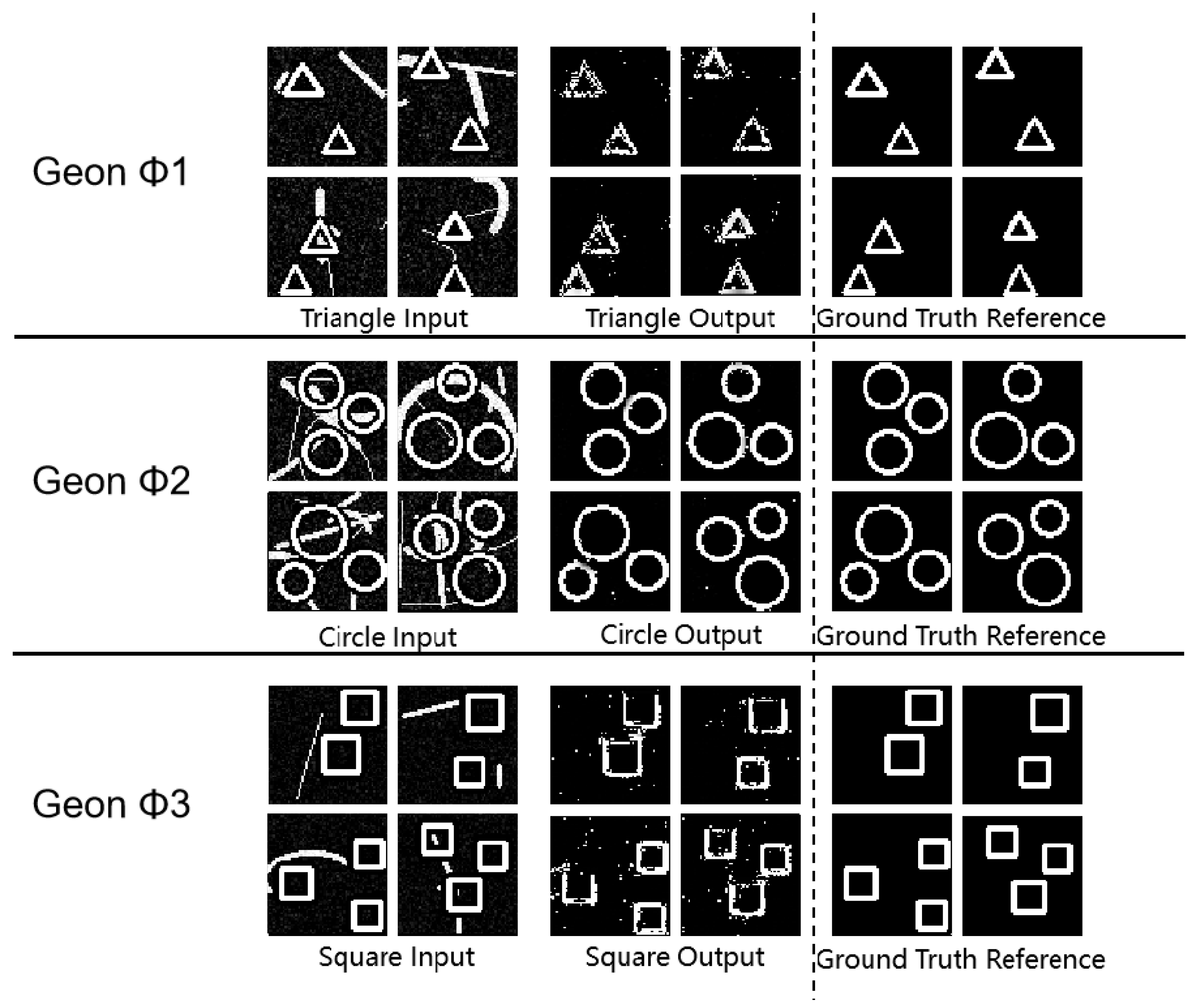

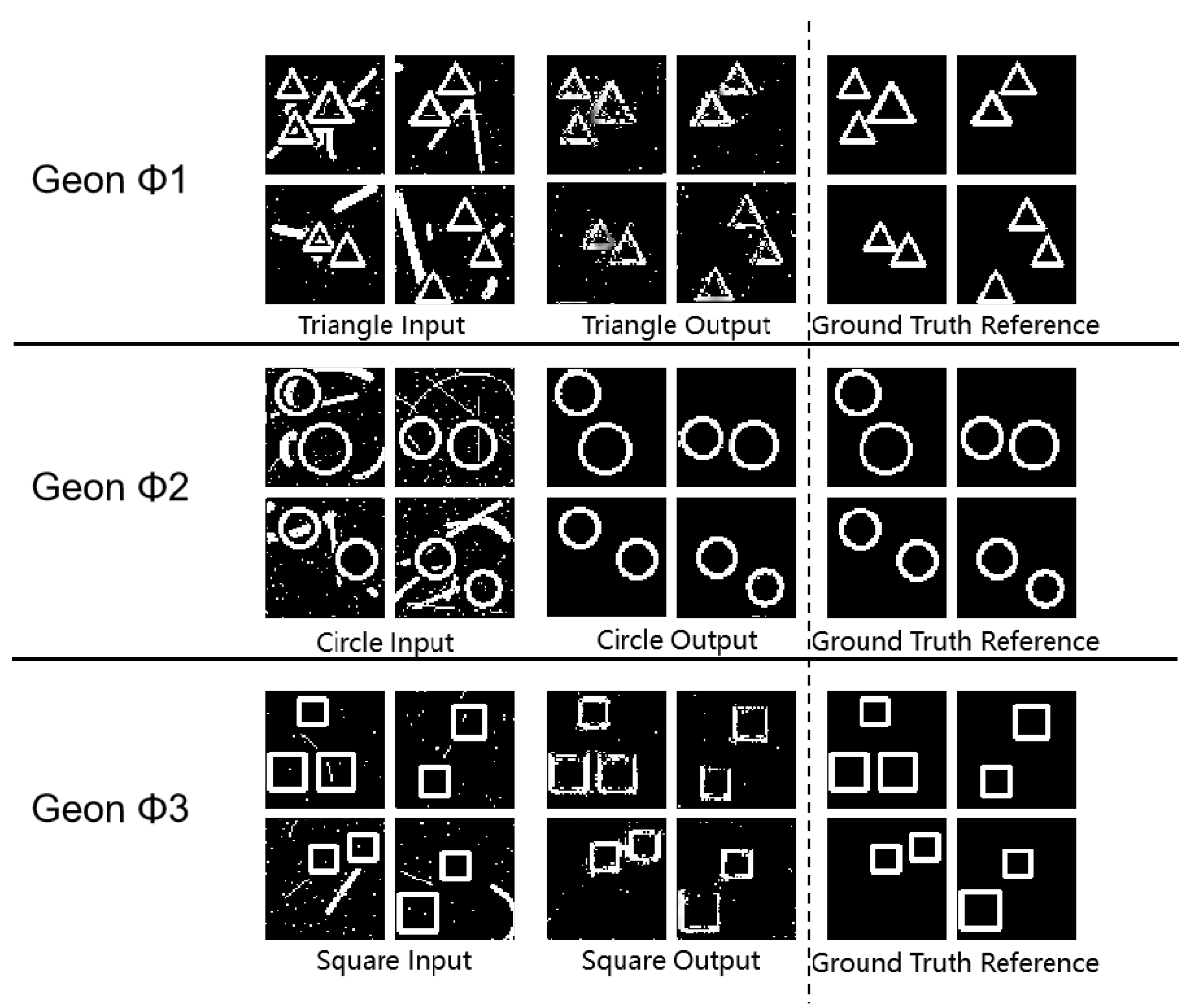

3.4.3. Multi-geon Detection

| Geon | SSIM | PSNR | MSE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Triangle | 0.79 | 46.17 | 2.64 |

| Circle | 0.98 | 48.58 | 1.35 |

| Square | 0.77 | 51.55 | 0.61 |

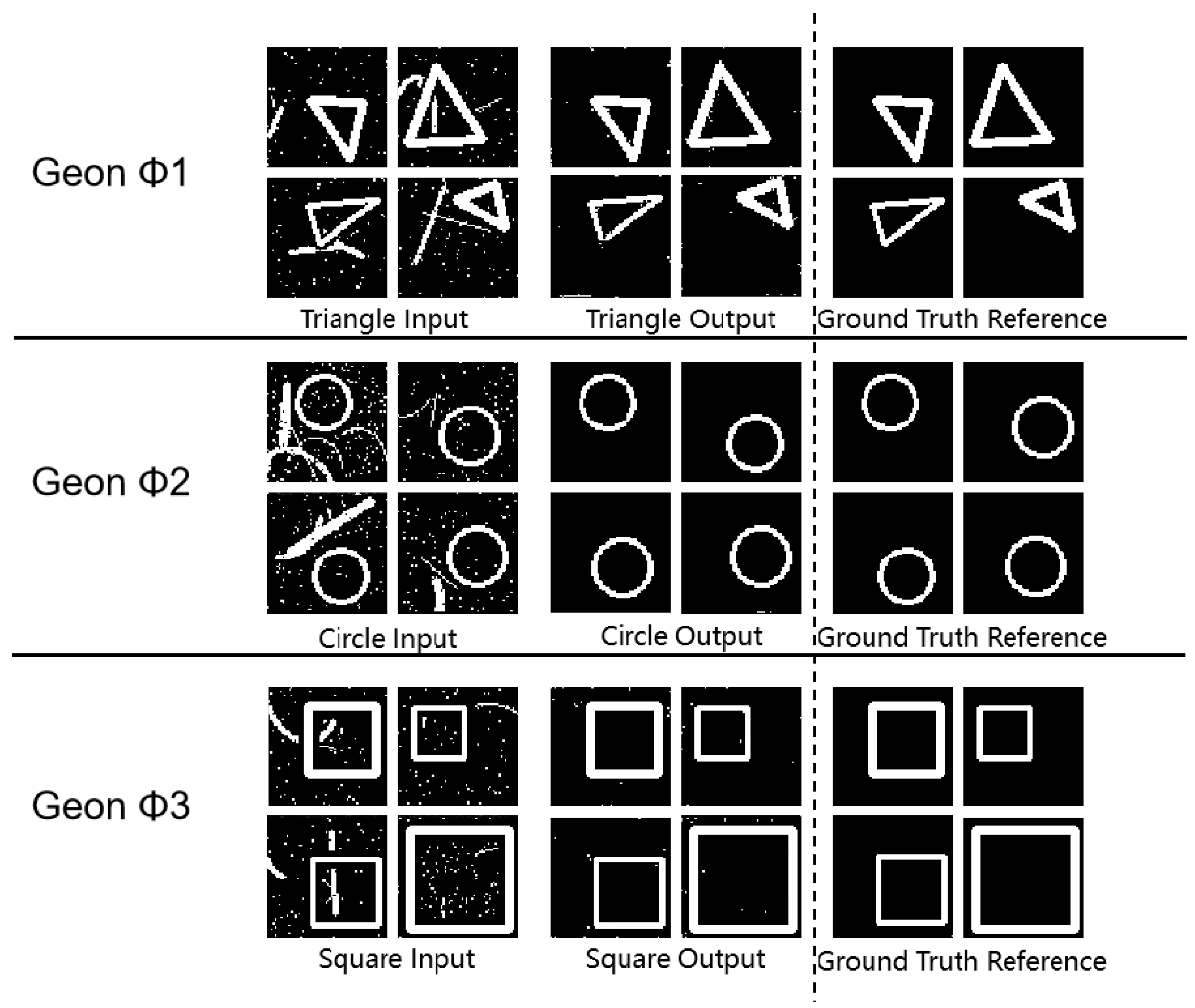

3.4.4. Robustness Evaluation Under Gaussian Noise Conditions

3.4.5. Robustness Evaluation under Salt-and-Pepper Noise Conditions (SPN)

4. Conclusions

References

- Biederman, I. Human image understanding: Recent research and a theory. Computer Vision, Graphics, and Image Processing 1985, 32, 29–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biederman, I. Recognition-by-components: a theory of human image understanding. Psychological Review 1987, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marr, D. , Hildreth, E. Theory of edge detection. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B. Biological Sciences 1980, 207, 187–217. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marr, D. , Poggio, T. From understanding computation to understanding neural circuitry. 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Marr, D. Visual information processing: The structure and creation of visual representations. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. B, Biological Sciences 1980, 290, 199–218. [Google Scholar]

- Marr, D. Early processing of visual information. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. B, Biological Sciences 1976, 275, 483–519. [Google Scholar]

- Marr, D. A theory for cerebral neocortex. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B. Biological sciences 1970, 176, 161–234. [Google Scholar]

- Marr, D. Representing visual information. 1977.

- Marr, D. , Thach, W. T. A theory of cerebellar cortex. In From the Retina to the Neocortex: Selected Papers of David Marr (1991), 11–50.

- Marr, D. Analysis of occluding contour. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B. Biological Sciences 1977, 197, 441–475. [Google Scholar]

- Marr, D. , Nishihara, H. K. Representation and recognition of the spatial organization of three-dimensional shapes. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B. Biological Sciences 1978, 200, 269–294. [Google Scholar]

- Marr, D. , Poggio, T. A computational theory of human stereo vision. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B. Biological Sciences 1979, 204, 301–328. [Google Scholar]

- Marr, D. , Ullman, S. Directional selectivity and its use in early visual processing. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B. Biological Sciences 1981, 211, 151–180. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Marr, D. Artificial intelligence—a personal view. Artificial Intelligence 1977, 9, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marr, D. , Vaina, L. Representation and recognition of the movements of shapes. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B. Biological Sciences 1982, 214, 501–524. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Torre, V. , Poggio, T. A. On edge detection. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 1986, 2, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertero, M. , Poggio, T. A., Torre, V. Ill-posed problems in early vision. Proceedings of the IEEE 1988, 76, 869–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuille, A. L. , Poggio, T. A. Scaling theorems for zero crossings. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 1986, 1, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunelli, R. , Poggio, T. Face recognition: Features versus templates. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 1993, 15, 1042–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, K. K. , Poggio, T. Example-based learning for view-based human face detection. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 1998, 20, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marr, D. , Poggio, T. A computational theory of human stereo vision. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B. Biological Sciences 1979, 204, 301–328. [Google Scholar]

- Papageorgiou, C. , Poggio, T. A trainable system for object detection. International Journal of Computer Vision 2000, 38, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riesenhuber, M. , Poggio, T. Hierarchical models of object recognition in cortex. Nature Neuroscience 1999, 2, 1019–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhagyashri, P. T. , Rupesh, T., Priyanka, K. K., et al. Marvin Minsky: The Visionary Behind the Confocal Microscope and the Father of Artificial Intelligence. Cureus 2024, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Minsky, M. L. Why people think computers can’t. AI Magazine 1982, 3, 3–3. [Google Scholar]

- Minsky, M. A framework for representing knowledge. 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Minsky, M. , Papert, S. (1969) Marvin Minsky and Seymour Papert, Perceptrons. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, Introduction, pp. 1–20, and p. 73 (Figure 5.1). 1988.

- Minsky, M. Commonsense-based interfaces. Communications of the ACM 2000, 43, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minsky, M. , Papert, S. An introduction to computational geometry. Cambridge Tiass., 1969, 479. [Google Scholar]

- Minsky, M. Decentralized minds. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 1980, 3, 439–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S. , Yang, Z. , Ma, C., Huang, H., Vouga, E., Huang, 2753–2762., Q. HPNet: Deep Primitive Segmentation Using Hybrid Representations. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (2021). [Google Scholar]

- Zou, C. , Yumer, E. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision ( 2017), 900–909.

- Lin, Y. , Tang, C., Chu, F. J., et al. Using synthetic data and deep networks to recognize primitive shapes for object grasping. In 2020 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA) (2020), IEEE, 10494–10501.

- Aliev, K. A. , Sevastopolsky, A., Kolos, M., et al. Neural point-based graphics. In Computer Vision – ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, –28, 2020, Proceedings, Part XXII (2020), Springer International Publishing, 696–712. 23 August.

- Zhang, Z. , Sun, B., Yang, H., et al. H3dnet: 3d object detection using hybrid geometric primitives. In Computer Vision – ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, –28, 2020, Proceedings, Part XII (2020), Springer International Publishing, 311–329. 23 August.

- Xia, S. , Chen, D., Wang, R., et al. Geometric primitives in LiDAR point clouds: A review. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2020, 13, 685–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L. , Fu, H., Tai, C. L. Fast sketch segmentation and labeling with deep learning. IEEE Computer Graphics and Applications 2018, 39, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. , Wang, L. Beyond joints: Learning representations from primitive geometries for skeleton-based action recognition and detection. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2018, 27, 4382–4394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilbig, A. , Vogt, L., Holtzhausen, S., et al. Enhancing three-dimensional convolutional neural network-based geometric feature recognition for adaptive additive manufacturing: A signed distance field data approach. Journal of Computational Design and Engineering 2023, 10, 992–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanengo, C. , Raffo, A., Biasotti, S., et al. SHREC 2022: Fitting and recognition of simple geometric primitives on point clouds. Computers & Graphics 2022, 107, 32–49. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D. , Feng, C. Primitive fitting using deep geometric segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Automation and Robotics in Construction ( 36, 780–787.

- Huang, J. , Gao, J., Ganapathi-Subramanian, V., et al. DeepPrimitive: Image decomposition by layered primitive detection. Computational Visual Media 2018, 4, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geometry, C. S. Neural Shape Parsers for Constructive Solid Geometry. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2022, 44. [Google Scholar]

- Treisman, A. Preattentive processing in vision. Computer Vision, Graphics, and Image Processing 1985, 31, 156–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treisman, A. , Gormican, S. Feature analysis in early vision: evidence from search asymmetries. Psychological Review 1988, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treisman, A. Features and objects in visual processing. Scientific American 1986, 255, 114B–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treisman, A. Perceptual grouping and attention in visual search for features and for objects. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance 1982, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treisman, A. How the deployment of attention determines what we see. In Progress in Psychological Science around the World. Volume 1: Neural, Cognitive and Developmental Issues (2013), Psychology Press, 245–277.

- Treisman, A. Binocular rivalry and stereoscopic depth perception. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology 1962, 14, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treisman, A. Feature binding, attention and object perception. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 1998, 353, 1295–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treisman, A. Features and objects: The fourteenth Bartlett memorial lecture. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology Section A 1988, 40, 201–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treisman, A. , DeSchepper, B. Object tokens, attention, and visual memory. (1996).

- Treisman, A. , Paterson, R. Emergent features, attention, and object perception. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance 1984, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Treisman, A. M. , Gelade, G. A feature-integration theory of attention. Cognitive Psychology 1980, 12, 97–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treisman, A. Visual attention and the perception of features and objects. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne 1994, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itti, L. , Koch, C. Computational modelling of visual attention. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2001, 2, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borji, A. , Itti, L. State-of-the-art in visual attention modeling. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2012, 35, 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itti, L. , Koch, C., Braun, J. T: Revisiting spatial vision.

- Itti, L. Automatic foveation for video compression using a neurobiological model of visual attention. IEEE Transactions on Image Processing 2004, 13, 1304–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itti, L. Quantitative modelling of perceptual salience at human eye position. Visual Cognition 2006, 14, (4–8). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmi, R. , Itti, L. The role of memory in guiding attention during natural vision. Journal of Vision 2006, 6, 4–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itti, L. , Gold, C., Koch, C. Visual attention and target detection in cluttered natural scenes. Optical Engineering 2001, 40, 1784–1793. [Google Scholar]

- Itti, L. , Koch, C. Comparison of feature combination strategies for saliency-based visual attention systems. In Human Vision and Electronic Imaging IV (1999), SPIE, 3644, 473–482.

- Zhang, Y. , Wu, X., Zheng, C., et al. Effects of vergence eye movement planning on size perception and early visual processing. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 2024, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Yuxuan, C. , Zhang, D., Liang, B., et al. Visual creativity imagery modulates local spontaneous activity amplitude of resting-stating brain.

- Zhang, W. , He, X., Liu, S., et al. Neural correlates of appreciating natural landscape and landscape garden: Evidence from an fMRI study. Brain and Behavior 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, X. , Zhang, D., Liang, B., et al. Reconfiguration of the brain functional network associated with visual task demands. PLoS One 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L. F. , Wang, K., He, L., et al. Twofold advantages of face processing with or without visual awareness. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance 2021, 47. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. , Wu, X., Zheng, C., et al. Effects of vergence eye movement planning on size perception and early visual processing. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 2024, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H. , Cai, T., Xu, J., et al. Neural correlates of stereoscopic depth perception: a fNIRS study. In 2016 Progress in Electromagnetic Research Symposium (PIERS) (2016), IEEE, 4442–4446.

- Li, J. , Chen, S., Wang, S., Lei, M., Dai, X., Liang, C., Xu, K., Lin, S., Li, Y., Fan, Y., et al. "An optical biomimetic eyes with interested object imaging. arXiv, arXiv:2108.04236.

- Li, J. , Lei, M., Dai, X., Wang, S., Zhong, T., Liang, C., Wang, C., Xie, P., Wang, R. "Compressed Sensing Based Object Imaging System and Imaging Method Therefor.". U.S. Patent 2021/0144278 A1, 13 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ronneberger, O. , Fischer, P., Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2015: 18th International Conference, Munich, Germany, -9, 2015, Proceedings, Part III (2015), Springer International Publishing, 234–241. 5 October.

- Rosenblatt, Frank. "The perceptron: a probabilistic model for information storage and organization in the brain." Psychological Review 65, no. 6 (1958): 386-408.

- Liu, Ziming, et al. “KAN: Kolmogorov-Arnold Networks.” ArXiv abs/2404.19756 (2024): n. pag.

- Zhang, K. , Zuo, W. In M., and Zhang, L. "Deep plug-and-play super-resolution for arbitrary blur kernels." In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Washington, 2019, D.C.: IEEE Computer Society; pp. 1671–1681.

- Horé, A. , and D. Ziou. "Image Quality Metrics: PSNR vs. SSIM." In 2010 20th International Conference on Pattern Recognition, Istanbul, Turkey, 2010, pp. 2366-2369. [CrossRef]

- Bauer, Eric, and Ron Kohavi. "An Empirical Comparison of Voting Classification Algorithms: Bagging, Boosting, and Variants." Machine Learning 36 (1999): 105-139.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).