Introduction

Dental implants have become the gold standard for replacing missing or failing teeth since their introduction by Brånemark in the 1970s [

1]. While implant-supported restorations offer predictable and effective outcomes, they are not without biological and mechanical complications. Reported failure rates range from 1% to 19% [

2,

3], and every implant treatment plan must consider these potential risks. Importantly, the decision to replace a compromised tooth with a dental implant requires careful evaluation. Pjetursson and Heimisdottir [

4] proposed a classification system for natural teeth as secure, doubtful, or irrational to treat. Secure teeth are expected to function without complex intervention, while doubtful teeth may require advanced therapies and close maintenance. Teeth deemed irrational to treat are beyond salvage and are best managed through extraction. However, this classification can be subjective, and no universally accepted, evidence-based criteria currently define the so-called “failing dentition.” Moreover, alternative treatments may offer comparable outcomes to implant therapy. For example, endodontic retreatment of teeth with persistent pathology and questionable prognosis has shown similar success rates to implant rehabilitation [

5]. Likewise, regenerative periodontal therapy can alter the prognosis of hopeless teeth, often providing a more cost-effective solution than extraction and implant placement [

6]. Ultimately, no implant can exceed the longevity of a healthy, well-maintained natural tooth. Implant failures are generally categorized as early or late, depending on whether they occur before or after functional loading [

7]. Early failures, often related to the inability to achieve osseointegration, are primarily biological in origin [

8,

9]. In contrast, late failures can arise from either biological or mechanical complications. Peri-implantitis, a common biological issue, leads to the progressive loss of peri-implant hard and soft tissues [

10,

11]. Mechanical complications, such as overload or prosthetic misfit, may result in fractures of the implant body, abutment screw, or prosthetic components [

12,

13]. Managing late implant failure is especially challenging. These cases typically involve significant bone loss and occur after prosthetic treatment has been completed, often leading to patient dissatisfaction due to added costs and extended treatment time [

14]. Retreatment in such scenarios carries a higher risk of failure, partly because underlying risk factors may persist, and bone deficiencies often necessitate advanced regenerative procedures. One promising solution is computer-guided bone regeneration (CGBR), which combines computer-aided design (CAD) and manufacturing (CAM) with a prosthetically driven workflow to preoperatively plan and execute precise bone augmentation based on the intended prosthetic outcome [

15,

16].

This case report presents a comprehensive, fully digital approach to the aesthetic and functional rehabilitation of a failed dental implant due to peri-implantitis. It highlights the complexity of managing late implant failures and demonstrates how modern digital tools, particularly within the framework of CGBR, can improve treatment planning and outcomes. Furthermore, it underscores the importance of a prosthetically driven approach in reducing complications and enhancing the success of retreatment in previously failed implant cases.

2. Case Summary

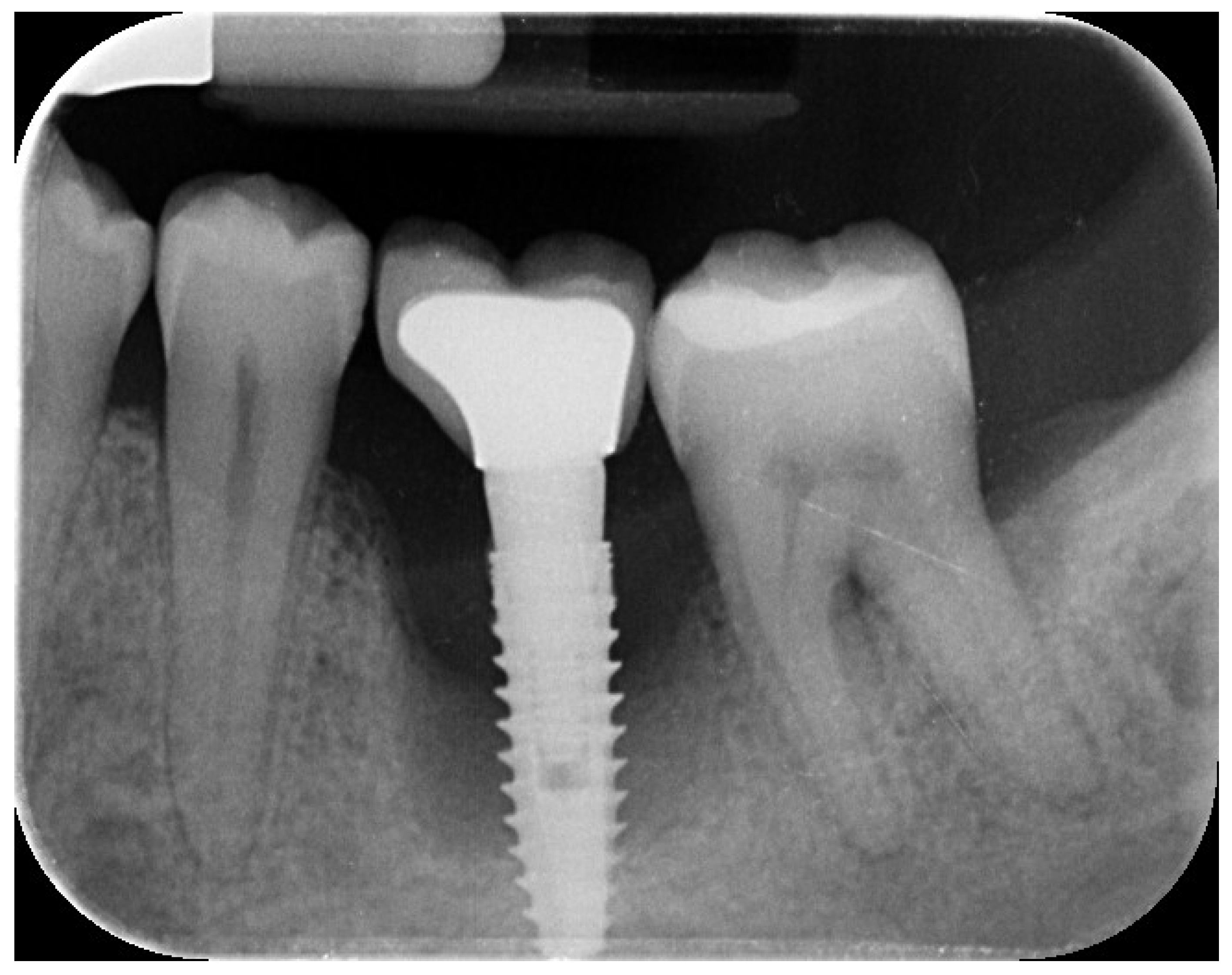

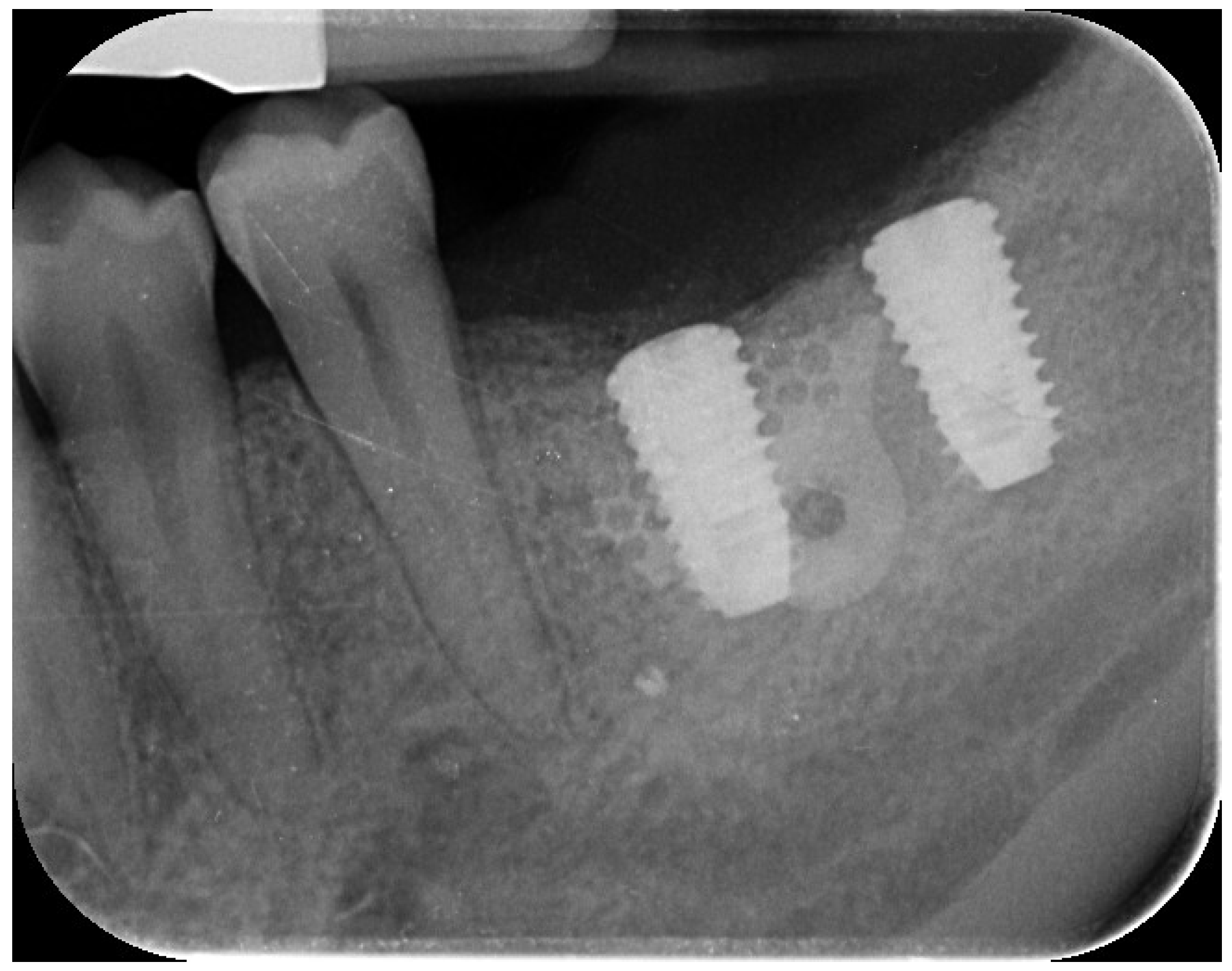

A 44-year-old female patient presented with pain and swelling in the left mandibular region, primarily motivated by functional concerns and a desire to improve periodontal health. The patient reported the placement of a dental implant six years earlier in the region of the left mandibular first molar, intended to replace a hopeless tooth (

Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Initial radiographic assessment.

Figure 1.

Initial radiographic assessment.

She was systemically healthy, a non-smoker, and diagnosed with localized advanced chronic periodontitis (AAP, 1999), including Grade III furcation involvement of the adjacent second mandibular molar [

17].

Clinical and radiographic evaluations revealed a cement-retained, implant-supported prosthesis at the site (

Figure 2) .

Figure 2.

implant-supported prosthesis at the site.

Figure 2.

implant-supported prosthesis at the site.

The implant site exhibited bleeding and suppuration upon gentle probing, probing depths ≥6 mm, and bone loss ≥3 mm apical to the coronal portion of the implant’s intraosseous segment. A diagnosis of peri-implantitis was made (

Figure 3), consistent with the 2017 World Workshop criteria [

18]

Treatment options—including retention or removal of the failing implant and molar—were discussed. Due to the patient's age and extent of disease progression, extraction of both the natural tooth and the implant was planned [

19,

20]. Written informed consent was obtained for all surgical and prosthetic procedures and the use of clinical and radiographic data for publication. The study adhered to the ethical principles of the 2013 Declaration of Helsinki.

On the day of surgery, the patient received antibiotic prophylaxis (2 g amoxicillin, 1 hour preoperatively; followed by 1 g twice daily for 5 days). The implant was atraumatically unscrewed and the tooth was extracted. Granulation tissue was thoroughly debrided to induce spontaneous bleeding, and a 4-0 resorbable suture was applied.

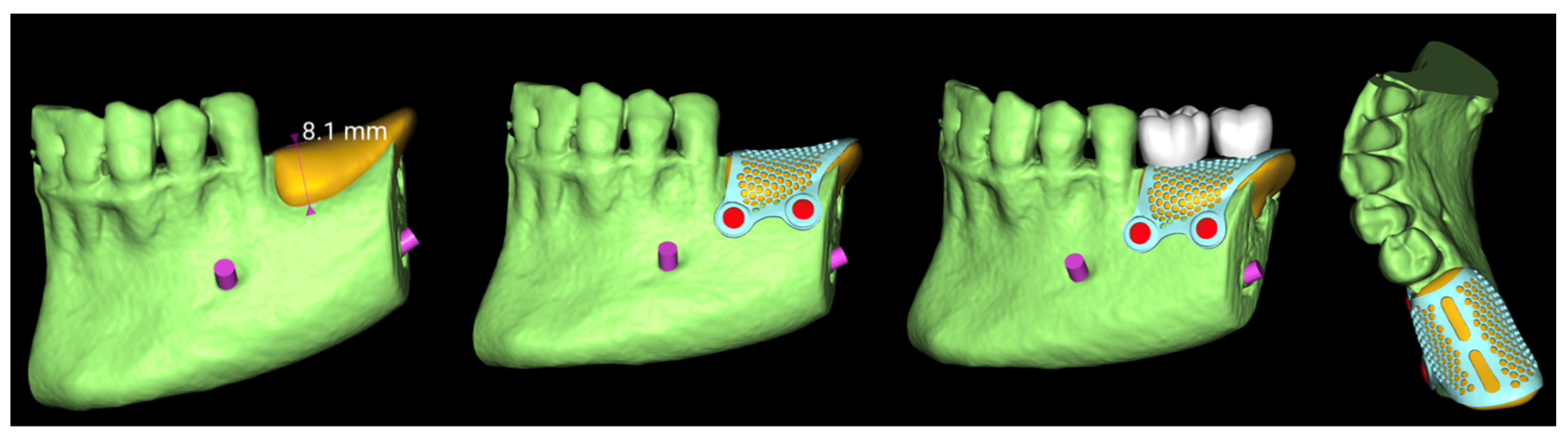

Eight weeks post-extraction, a CBCT scan and intraoral scan (Medit i700, Medit Corp., Seoul, Korea) were obtained . A diagnostic wax-up was produced, followed by prosthetically driven virtual implant planning. Two implants were planned for the first and second molar sites, suitable for a screw-retained prosthesis, regardless of the existing bone volume.

The virtual implant planning was exported and a customized CAD/CAM titanium mesh was designed based on a commercially available template (OssBuilder, Osstem Implant Co. Ltd., Seoul, Korea) (

Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Vertical guided bone regeneration (vGBR) procedure.

Figure 3.

Vertical guided bone regeneration (vGBR) procedure.

The mesh was designed by an expert using exocad DentalCAD software (exocad, Darmstadt, Germany) and fabricated via laser melting (New Ancorvis Srl, Bargellino, Calderara di Reno, Italy).

A vertical guided bone regeneration (vGBR) procedure was performed by an experienced clinician (M.T.). Antibiotic prophylaxis (2 g amoxicillin preoperatively; 1 g twice daily for 8 days) was repeated.

Prior to surgery, the patient rinsed with 0.2% chlorhexidine for 1 minute, and the surgical site was isolated with a sterile drape. Local anesthesia was administered using 4% articaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine (Ubistein, 3M ESPE, Milan, Italy).

A buccal crestal incision was made through keratinized tissue (blade No. 15c), and a full-thickness flap was elevated. Vertical releasing incisions were placed mesially (two teeth away) and distally into the retromolar region.

The site was debrided and autogenous bone was harvested using a cortical bone scraper (Safe Scraper, Micross, Meta, Reggio Emilia, Italy).

After plasma sterilization of the mesh, a 1:1 mixture (

Figure 4) of autogenous bone and anorganic bovine bone (A-Oss, Osstem Implant) was placed and the mesh secured (

Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Bone regeneration using a cortical bone scraper.

Figure 4.

Bone regeneration using a cortical bone scraper.

Figure 5.

Mesh placement for guided bone regeneration.

Figure 5.

Mesh placement for guided bone regeneration.

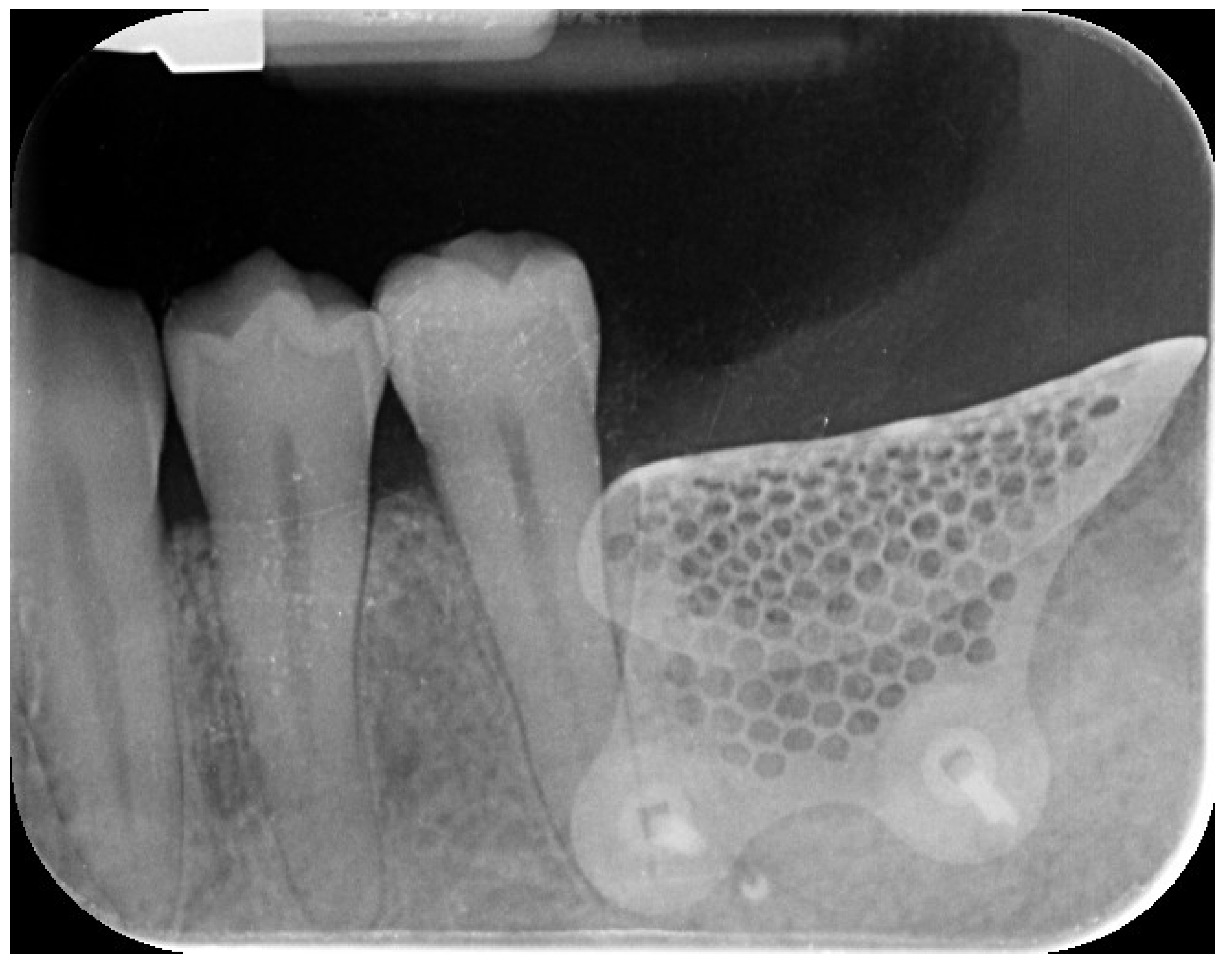

The flap was carefully mobilized buccally and lingually for tension-free closure, and 5-0 resorbable sutures were applied. Nine months later (

Figure 6) , a CBCT and intraoral scan confirmed adequate bone regeneration.

Figure 6.

Nine-month follow-up.

Figure 6.

Nine-month follow-up.

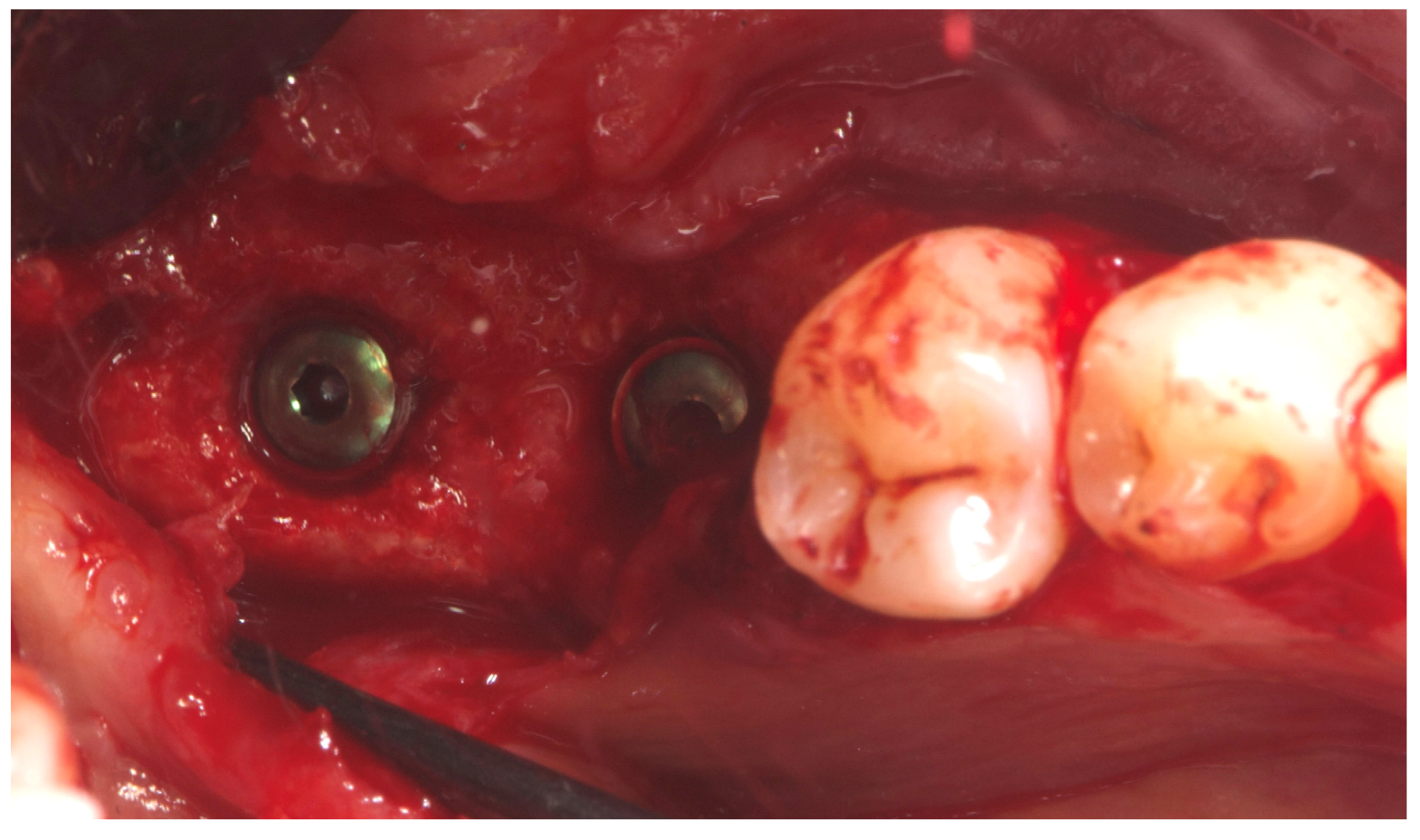

Two implants (Osstem TSIII SOI, 4.5 mm diameter) with hydrophilic surfaces were placed under local anesthesia, using a fully guided (

Figure 7 ), metal-sleeve-free surgical template (OneGuide, Osstem Implant Co., Ltd., Seoul, Korea).

Figure 7.

Implant planning.

Figure 7.

Implant planning.

Notably, the buccal portion of the titanium mesh was completely covered by newly formed cortical bone, allowing for partial removal of the mesh prior to implant placement (

Figure 8 ).

Figure 8.

Final intraoral image.

Figure 8.

Final intraoral image.

Two months later, a second-stage surgery was performed. A horizontal incision was made between the keratinized tissue and mucosa, and a partial-thickness flap was apically repositioned (

Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Final radiographic assessment showing clear visibility of the buccal portion of the membrane left in situ.

Figure 9.

Final radiographic assessment showing clear visibility of the buccal portion of the membrane left in situ.

A free gingival graft (FGG), measuring 20 × 6 mm, was harvested from the palatal mucosa (first premolar to first molar). The epithelial layer of the FGG was partially removed to allow partial subflap insertion, while a portion remained exposed . The graft was stabilized with resorbable single sutures. Two months post-grafting, a screw-retained temporary restoration was placed. Four months later, two single monolithic zirconia crowns, bonded to titanium link abutments, were delivered (

Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Four months post-grafting, two single monolithic zirconia crowns were delivered and bonded to titanium link abutments, ensuring functional and aesthetic rehabilitation.

Figure 10.

Four months post-grafting, two single monolithic zirconia crowns were delivered and bonded to titanium link abutments, ensuring functional and aesthetic rehabilitation.

The patient entered a 6-month hygiene maintenance protocol and continues to be monitored (

Figure 11).

Figure 11.

One year follow-up.

Figure 11.

One year follow-up.

3. Discussion

The retreatment of failed dental implants presents a complex clinical scenario that demands careful diagnosis, patient-centered planning, and the use of advanced regenerative and prosthetic technologies. In this case, the decision to remove a compromised implant affected by peri-implantitis—along with the adjacent hopeless molar—was driven by progressive bone loss, high disease risk, and the patient’s functional and periodontal concerns. Peri-implantitis remains one of the primary causes of late implant failure, and its resolution often necessitates implant removal, especially when bone loss exceeds 50% of the implant length or regenerative predictability is low [

10,

11].

Rehabilitation in the posterior mandible after implant failure is further complicated by vertical and horizontal bone deficiencies that often follow explantation. Guided bone regeneration (GBR) remains the gold standard for such defects, but vertical augmentation remains technique-sensitive and unpredictable. In recent years, the emergence of computer-guided bone regeneration (CGBR) using CAD/CAM technologies has revolutionized this field, improving the precision and predictability of complex bone augmentation procedures [

15,

16]. The use of a customized titanium mesh, as in the present case, has shown promising outcomes in vertical ridge augmentation by stabilizing the graft and maintaining space for bone regeneration while conforming to the patient’s anatomy [

21].

Specifically, the OssBuilder titanium mesh, designed and fabricated through a digital workflow, enabled ideal contouring of the graft volume while minimizing intraoperative adjustments. Tallarico et al. have reported favorable outcomes using customized titanium meshes in vertical GBR, emphasizing the benefits of digital planning, passive fit, and reduced surgical time [

15]. In this case, digital planning was driven by prosthetic requirements and aided by intraoral scanning and CBCT merging. This approach aligns with the principles of prosthetically guided regeneration, ensuring that implant placement supports the intended restorative design from the outset.

The bone grafting protocol combined autogenous bone—harvested from the surgical site—with anorganic bovine bone (A-Oss) in a 1:1 ratio. A-Oss has been shown to promote osteoconduction and volume stability, particularly when used in combination with autogenous bone to enhance regenerative outcomes [

22]. This biomaterial has also been validated in multiple GBR protocols in posterior mandibular defects, including those involving titanium mesh [

15].

Following successful regeneration, implant placement was performed using a fully guided, metal-sleeve-free protocol (OneGuide, Osstem). This surgical system has been shown to improve accuracy in implant positioning and reduce intraoperative risk, particularly in anatomically challenging or regenerated sites. Tallarico et al. have documented the clinical reliability of guided surgery using OneGuide in combination with preoperative CBCT and digital wax-up protocols, confirming high levels of implant placement precision and restoration fit [

23].

The implants selected in this case featured the SOI (Surface Osstem Implant) hydrophilic surface, designed to enhance early osseointegration. Hydrophilic implant surfaces have demonstrated superior biological response, particularly in compromised bone or grafted sites, by promoting rapid protein adsorption and early cellular adhesion [

24]. Tallarico and colleagues have recently investigated this surface in challenging clinical cases, showing favorable short- and medium-term outcomes in both native and regenerated bone [

24].

Overall, this case underscores the value of a fully digital, prosthetically driven workflow in managing late implant failure and supporting reimplantation in previously compromised sites. While retreatment inherently carries a higher risk of complications, the integration of CAD/CAM regenerative planning, modern implant surfaces, and guided surgical techniques can enhance both the efficiency and predictability of complex rehabilitation. Importantly, interdisciplinary collaboration and long-term maintenance protocols remain essential to ensuring sustained functional and aesthetic outcomes in re-treatment scenarios.