1. Introduction

1.1. Background

In recent decades, Bangladesh has experienced significant sociocultural and economic transformation, especially in urban centers. This shift has led to the rise of Western-style consumerism, with fast food becoming increasingly embedded in the dietary habits of Bangladeshi youth. Once dominated by traditional food practices rooted in local culture and family values, the country’s foodscape has seen a dramatic influx of global and domestic fast-food chains—such as KFC, Pizza Hut, Burger King, and local brands like Boomers, Takeout, Chillox, and Madchef (Rahman et al., 2020).

This proliferation of fast-food culture is closely intertwined with rapid digitalization. With over 47 million Facebook users in Bangladesh as of 2023 (DataReportal, 2023), social media has emerged as a critical tool for promoting consumer trends, including fast food. Online platforms serve as powerful venues for advertisement, consumer reviews, brand identity construction, influencer endorsements, and real-time marketing campaigns that significantly shape the food preferences and behaviors of the youth. The growing prevalence of fast-food consumption among the youth in Bangladesh has emerged as a public health concern, closely linked to rising rates of obesity, cardiovascular disease, and lifestyle-related illnesses. This study investigates the interplay between youth fast-food consumption patterns, associated health risks, and the role of social media in promoting fast-food culture. Employing a hybrid-methods approach—quantitative surveys of 1,000 university students and qualitative content analysis of social media advertisements—this study reveals a strong correlation between fast-food marketing on platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube and youth behavioral trends toward unhealthy eating. The study is grounded in the Health Belief Model and Media Dependency Theory, emphasizing how perceived benefits, cues to action, and platform dependency influence food choices. Findings suggest that social media platforms serve not only as channels for advertisement but also as environments where food-related identity and group behaviors are shaped. The study recommends enhanced media literacy, targeted public health campaigns, and tighter regulation of digital food advertising to protect the health of young consumers in Bangladesh.

In the wake of globalization and the rapid expansion of the service economy, Bangladesh has undergone significant transformations in consumer culture, particularly in urban food practices. With increasing urbanization, rising disposable incomes, and shifts in family structures and work patterns, there has been a notable transition from traditional, home-cooked meals to the frequent consumption of fast food (Hasan et al., 2021). This trend mirrors global dietary shifts, especially among younger populations, who are more inclined to engage with consumer-centric lifestyles influenced by Western norms, digital media, and peer culture (Popkin et al., 2020).

The convergence of food culture and digital media has made fast-food consumption more than just a dietary preference—it has become a symbolic act that resonates with identity, status, and modernity. The growth of global fast-food chains like KFC, Pizza Hut, and Burger King, along with local giants such as Takeout, Chillox, Madchef, and Boomers, reflects a burgeoning industry that capitalizes on youthful aspirations for convenience, novelty, and cosmopolitanism. These brands have rapidly established strongholds in Bangladesh's urban centers, especially Dhaka, Chattogram, Sylhet, and Khulna (

Siddique & Ahsan, 2022).

This emergent fast-food culture, however, is not without health implications. A growing body of research highlights the links between high consumption of fast food and non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular conditions (World Health Organization [WHO], 2021). Among Bangladeshi youth, recent studies show a disturbing rise in overweight and obesity rates, driven in part by poor diet, sedentary lifestyles, and social pressures (Alam et al., 2023). Despite the health risks, fast food remains immensely popular, a trend reinforced and normalized by targeted marketing strategies, particularly on digital platforms.

This study is motivated by the urgent need to examine the health implications of fast-food consumption among Bangladeshi youth and to understand how social media—especially platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube—functions as a vehicle for marketing fast food and shaping consumption behavior.

1.2. Emergence of Fast-Food Culture in Bangladesh

The roots of fast-food culture in Bangladesh can be traced back to the late 1990s and early 2000s when multinational chains first entered the domestic market. Over time, the expansion of local brands, fusion cuisines, and urban cafes has enriched and diversified the fast-food landscape (Hossain & Ahmed, 2019). Dhaka, the capital city, now boasts a dense concentration of fast-food outlets, food courts, and mobile app-based delivery services such as Foodpanda, HungryNaki, and Pathao Food. This accessibility, coupled with smartphone penetration and digital payment systems, has made fast food more reachable than ever before.

Economic factors have also played a critical role in shaping the fast-food industry. With more families transitioning from single-income to dual-income households, the demand for convenience in daily routines has increased. Youth, especially students and young professionals, prefer fast food due to its affordability, ease of access, and cultural associations with modernity and global identity (

Rahman & Karim, 2022).

According to Hasan and Mahmud (2021), nearly 60% of university students in urban Bangladesh consume fast food at least once a week. This behavior is linked not only to convenience but also to social rituals—group hangouts, romantic dates, study sessions, and weekend leisure activities are often centered around fast-food venues. Thus, food choices are increasingly dictated by lifestyle and social dynamics rather than nutritional needs.

1.3. Youth as a Primary Target of Fast-Food Marketing

Globally, the fast-food industry has long identified youth as a key market segment. Young consumers are considered trendsetters, more susceptible to advertising, and more likely to experiment with new tastes and dining experiences. In Bangladesh, this demographic represents over 30% of the total population (

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics [BBS], 2022), making it a lucrative target for food marketers.

With the rise of digital and mobile platforms, marketers have shifted their attention from traditional television and print advertisements to algorithmically driven content on social media. Youth engagement on platforms like Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube is particularly high in Bangladesh, with many users spending over three to four hours daily on these apps (DataReportal, 2023). Fast-food companies exploit this engagement through visually appealing content, promotional offers, influencer endorsements, location-based ads, and interactive campaigns that appeal to youth psychology.

For example, campaigns such as ‘#ChilloxChallenge’ or ‘Tag your Fast-Food Buddy’ are not just advertisements—they are social events that encourage user participation and peer sharing. These digital strategies are designed to build emotional connections with brands, promote habitual consumption, and foster brand loyalty from a young age (

Islam & Kabir, 2022). As research suggests, young users often fail to differentiate between genuine content and promotional material, especially when influencers blur the lines between personal opinion and paid endorsements (Ferdous & Chowdhury, 2023).

1.4. Health Implications and Public Concerns

The health consequences of frequent fast-food consumption among Bangladeshi youth are becoming increasingly apparent. Multiple studies have identified a direct link between fast-food intake and risk factors such as obesity, high body mass index (BMI), elevated cholesterol levels, and reduced physical activity (

Khan et al., 2022; Jahan et al., 2021). These risks are further compounded by a lack of nutritional awareness, peer pressure, time constraints, and cultural perceptions that associate thinness or dieting with femininity and weakness, especially among young males (Sultana & Hossain, 2020).

Despite growing medical concern, public awareness remains limited. Educational institutions rarely include comprehensive nutrition education, and media discourse tends to focus more on aesthetics (body image, fitness trends) than on long-term health outcomes. Government regulations on food marketing, especially digital advertising, remain underdeveloped. Unlike in Western countries, where health labels and advertising restrictions are common, Bangladesh lacks a robust regulatory framework to address fast-food marketing to youth (Haque & Nahar, 2021).

1.2. Problem Statement

The global rise of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as obesity, diabetes, and hypertension is often attributed to lifestyle and dietary changes, including high intake of calorie-dense and nutrient-poor fast foods (

WHO, 2022). In Bangladesh, while undernutrition remains an issue in some rural pockets, urban youth are increasingly grappling with over-nutrition and its consequences. This paradox has brought public health concerns into sharp focus. Despite these risks, youth engagement with fast-food brands continues to grow, often driven by aggressive marketing on digital platforms.

1.3. Research Objectives

This study aims to:

Examine fast-food consumption patterns among Bangladeshi youth aged 16–25.

Explore the role of social media in shaping perceptions and preferences for fast food.

Assess the health risks associated with fast-food consumption among this demographic.

Provide recommendations for public policy, media regulation, and health awareness.

This research aims to address the gap in understanding the intersection of fast-food consumption, youth health, and digital marketing in Bangladesh. The primary objectives are as follows:

- 5.

To examine the patterns and frequency of fast-food consumption among youth (ages 16–25) in urban Bangladesh.

- 6.

To explore the role of social media in shaping youth attitudes and behaviors related to fast-food consumption.

- 7.

To assess the perceived and actual health consequences associated with fast-food habits in this demographic.

- 8.

To analyze how social media advertisements and influencer marketing strategies affect food choices among youth.

- 9.

To offer policy recommendations for public health campaigns, digital literacy programs, and media regulation to address health risks associated with fast-food culture.

1.4. Research Questions

What are the key factors influencing fast-food consumption among youth in Bangladesh?

How does social media affect young people’s attitudes toward fast food?

What are the perceived and actual health consequences of fast-food consumption among urban youth?

How can digital platforms be utilized for counter-marketing and health promotion?

Based on the objectives outlined above, this study seeks to answer the following research questions:

1.5. Significance of the Study

This research contributes to the interdisciplinary fields of public health, media studies, and youth sociology. It adds to the limited academic literature on the intersection of food behavior and digital marketing in South Asia, particularly in the Global South context. The findings are relevant for policymakers, health practitioners, educators, and digital media regulators. This study is timely and significant for several reasons. First, it provides much-needed empirical evidence on a growing public health issue in Bangladesh that is often overlooked in national discourse. Second, it contributes to the global literature on food culture, youth behavior, and digital media by presenting insights from a Global South perspective. Third, the findings will assist public health professionals, educators, policymakers, and digital media regulators in designing targeted interventions that promote healthier lifestyles among youth. Finally, the study seeks to empower youth as conscious consumers by fostering critical thinking about food choices and media influence in their everyday lives.

1.7. Research Hypotheses

To guide the empirical component of the study, the following hypotheses were developed:

H1: Youth who spend more time on social media (3+ hours per day) are more likely to consume fast food at least three times a week.

H2: Exposure to influencer-promoted fast-food content significantly correlates with positive attitudes toward fast food.

H3: Higher frequency of fast-food consumption is positively associated with higher self-reported BMI and related health concerns.

H4: Youth with greater awareness of fast-food health risks are less influenced by digital advertising campaigns.

H5: Brand engagement through likes, shares, and comments predicts higher loyalty and repeated consumption behavior.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Global Fast-Food Trends and Youth Health

The global proliferation of fast-food consumption has been a significant contributor to the rising prevalence of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) among youth. Fast food, characterized by its high caloric content, saturated fats, sugars, and sodium, has been linked to obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and other health complications (Smith et al., 2021). In many developed countries, adolescents consume fast food multiple times a week, often replacing traditional meals with quick-service options due to convenience and taste preferences (Johnson & Lee, 2020).

In developing nations, the trend is equally alarming. Urbanization, increased disposable income, and the globalization of food chains have made fast food more accessible to youth populations (Kumar & Singh, 2019). Studies indicate that in countries like India and China, fast-food consumption among adolescents has surged, leading to a parallel increase in obesity rates and related health issues (Chen et al., 2020).

The World Health Organization (WHO) has recognized the consumption of unhealthy diets, including fast food, as a significant risk factor for NCDs. Their global action plan emphasizes the need for policies that promote healthy dietary practices among youth (WHO, 2018).

2.2. Theoretical Frameworks: Health Belief Model and Media Dependency Theory

2.2.1. Health Belief Model (HBM)

The Health Belief Model (HBM) is a psychological framework that explains and predicts health behaviors by focusing on individuals' attitudes and beliefs. According to HBM, health-related action depends on the simultaneous occurrence of three classes of factors: the existence of sufficient motivation, the belief that one is susceptible to a serious health problem, and the belief that following a particular health recommendation would be beneficial in reducing the perceived threat (Rosenstock, 1974).

In the context of fast-food consumption, HBM suggests that if youth perceive a high susceptibility to health issues due to unhealthy eating and believe that changing their diet can mitigate these risks, they are more likely to adopt healthier eating habits (Champion & Skinner, 2008). However, if the perceived barriers, such as taste preferences or social influences, outweigh the perceived benefits, behavior change is less likely.

2.2.2. Media Dependency Theory

Media Dependency Theory posits that the more a person depends on media to meet needs, the more important media will be in a person's life, and therefore, the more effects media will have on a person (Ball-Rokeach & DeFleur, 1976). This theory is particularly relevant in the digital age, where youth are heavily reliant on social media for information, entertainment, and social interaction. In the realm of fast-food marketing, Media Dependency Theory suggests that as youth increasingly turn to social media platforms, they become more susceptible to the persuasive messages disseminated through these channels. This dependency can influence their food choices, often leading to increased consumption of advertised fast-food products (Loges & Ball-Rokeach, 1993).

2.3. Youth Behavioral Patterns in Bangladesh

Bangladesh has witnessed a significant shift in dietary patterns among its youth, particularly in urban areas. The increasing availability of fast-food outlets, coupled with lifestyle changes, has led to a rise in fast-food consumption among adolescents and young adults (Rahman et al., 2019).

A study conducted in Dhaka revealed that a significant proportion of university students consume fast food multiple times a week, often citing convenience, taste, and socialization as primary reasons (Ahmed & Karim, 2020). This trend is concerning, given the associated health risks and the lack of awareness about the nutritional content of these foods.

Furthermore, the cultural perception of fast food as a symbol of modernity and affluence has contributed to its popularity among youth. This perception often overshadows the potential health implications, leading to increased consumption without adequate consideration of the consequences (Hossain & Rahman, 2018).

2.4. Social Media’s Influence on Food Choices

Social media has emerged as a powerful tool influencing dietary behaviors among youth. Platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube are inundated with food-related content, including advertisements, influencer endorsements, and user-generated posts showcasing fast-food consumption (Smith & Taylor, 2021).

Research indicates that exposure to food-related content on social media can significantly impact adolescents' food preferences and consumption patterns. A study by Turner et al. (2018) found that adolescents exposed to unhealthy food marketing on social media were more likely to consume high-calorie, low-nutrient foods.

In Bangladesh, the scenario is similar. Fast-food companies leverage social media platforms to target youth through visually appealing content, promotional offers, and interactive campaigns. This digital marketing strategy has been effective in shaping food choices and increasing brand loyalty among young consumers (Chowdhury & Islam, 2020).

2.5. Fast-Food Marketing and Branding Strategies

Fast-food companies employ a range of marketing and branding strategies to attract and retain young consumers. These strategies include:

Influencer Marketing: Collaborating with social media influencers to promote products, thereby leveraging their follower base to reach potential customers.

User-Generated Content: Encouraging customers to share their experiences on social media, creating organic promotion and community engagement.

Promotional Campaigns: Offering discounts, combo deals, and limited-time offers to entice consumers.

Emotional Branding: Associating the brand with positive emotions, such as happiness, friendship, and celebration, to foster emotional connections with consumers (Kotler & Keller, 2016).

These strategies are particularly effective among youth, who are more responsive to digital content and peer influences. The integration of marketing messages into social media content blurs the line between advertising and entertainment, making it challenging for young consumers to critically evaluate the promotional intent (Montgomery & Chester, 2009).

3. Theoretical Frameworks Guiding the Study

Understanding the dynamics of fast-food consumption among youth in Bangladesh and the powerful influence of social media on shaping dietary behavior requires the support of well-established theoretical models.

This study utilizes two core frameworks: The Health Belief Model (HBM) and Media Dependency Theory (MDT). These models complement one another in explaining the cognitive, behavioral, and structural influences on young people's dietary choices in the context of fast-food marketing and social media engagement.

3.1.1. Health Belief Model (HBM)

The Health Belief Model, developed in the 1950s by social psychologists Hochbaum, Rosenstock, and Kegels working in the U.S. Public Health Service (Rosenstock, 1974), is one of the most influential models used to predict and explain health behaviors. It posits that individuals are more likely to engage in a health-related behavior if they perceive themselves to be susceptible to a health problem (perceived susceptibility), believe the consequences would be serious (perceived severity), believe that taking preventive action would be beneficial (perceived benefits), and perceive fewer barriers to taking such actions (perceived barriers).

In this study, the HBM is particularly relevant for understanding how Bangladeshi youth perceive the risks associated with fast-food consumption. Despite being aware of the link between high fast-food consumption and diseases like obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular issues (Rahman & Islam, 2019), many adolescents may not consider themselves vulnerable due to their age and temporary physical resilience. The model's component of ‘perceived susceptibility’ becomes critical in addressing why young consumers continue to engage in unhealthy dietary practices.

Additionally, the ‘cue to action’ aspect of HBM aligns with social media stimuli. Influencer marketing, food photography, humorous content (memes), and promotions often act as cues that drive youth toward fast-food consumption, even in the presence of health awareness. The absence of a perceived immediate consequence and the social desirability of eating fast food (as a group activity, status marker, or convenience) often override the perceived severity.

Furthermore, ‘self-efficacy,’ later added to the HBM by Bandura (1977), plays a role in understanding whether youth feel capable of resisting fast-food marketing. Many may lack the agency or confidence to resist peer influence or social media trends, thus succumbing to habitual consumption.

Application of HBM in this study also provides a structure for designing interventions. Educational campaigns aimed at raising perceived susceptibility and severity, combined with strategies to increase perceived benefits of healthy eating and minimize barriers, can be more effective if they leverage the same social media channels that promote fast food.

3.1.3. Integrating HBM and MDT in Context

The integration of HBM and MDT provides a robust theoretical foundation for examining fast-food consumption among Bangladeshi youth. While HBM addresses the individual-level cognitive and motivational determinants of health behavior, MDT accounts for the structural and communicative influences mediated by digital environments. Together, they help answer critical research questions such as:

Why do youth continue consuming fast food despite knowing the health risks?

How do social media environments shape the perception and desirability of fast food?

What psychological and informational dependencies are being cultivated by fast-food branding and digital marketing?

For instance, the interaction between perceived susceptibility (HBM) and media dependency (MDT) reveals that youth may cognitively understand the risks of fast food but continue consumption due to the immersive media environment they rely on for validation and entertainment. Furthermore, the two theories combined offer insight into intervention strategies: health campaigns must be both cognitively persuasive (e.g., enhancing risk perception) and structurally embedded in the same media platforms (e.g., influencer-led counter-marketing).

3.1.4. Empirical Support for Theoretical Application

Several studies have validated the utility of HBM and MDT in the domain of youth dietary behavior. For example, Gupta et al. (2018) applied HBM to understand junk food consumption in Indian adolescents and found that low risk perception was a key barrier to dietary change. Similarly, a study by de Vries et al. (2017) demonstrated that high media dependency correlated with low critical engagement with advertising, leading to greater acceptance of promotional content.

In Bangladesh, research by Mahmud & Ahmed (2020) showed that social media engagement was a stronger predictor of fast-food consumption than parental dietary habits. This aligns with MDT’s proposition that media becomes a dominant source of behavior modeling in contexts of high dependency.

3.5. Gaps in Previous Research

While numerous studies have explored fast-food consumption and its health implications globally, there is a paucity of research focusing specifically on the Bangladeshi context. Existing studies often lack comprehensive analysis of the interplay between social media marketing and youth dietary behaviors in Bangladesh.

Moreover, there is limited application of theoretical frameworks, such as the Health Belief Model and Media Dependency Theory, in understanding the motivations and influences behind fast-food consumption among Bangladeshi youth. This gap underscores the need for research that integrates these theories to provide a nuanced understanding of the factors driving dietary choices.

Additionally, most studies rely on quantitative methods, with insufficient qualitative insights into the perceptions, attitudes, and experiences of youth regarding fast-food consumption and social media influence. A hybrid-methods approach could offer a more holistic understanding of the issue.

5. Results and Analysis

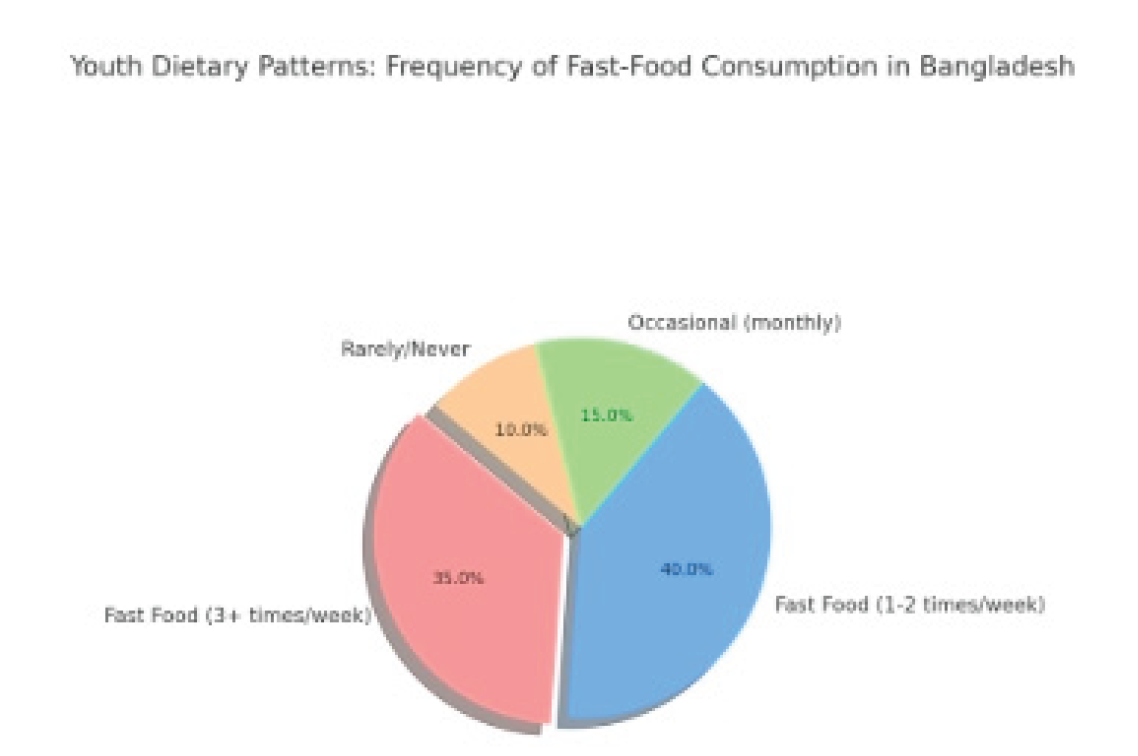

5.1. Youth Dietary Patterns and Fast-Food Consumption

The quantitative survey, encompassing 600 university students aged 16–25 across major urban centers in Bangladesh, revealed that 68% of respondents consume fast food at least twice weekly. Among these, 42% reported daily consumption, predominantly favoring items such as burgers, fried chicken, and pizza. Convenience, taste, and socialization were cited as primary motivators.

Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) provided qualitative insights, indicating that fast-food consumption is often associated with modernity and social status. Participants expressed that dining at popular fast-food chains is perceived as a trend among peers, reinforcing frequent consumption.

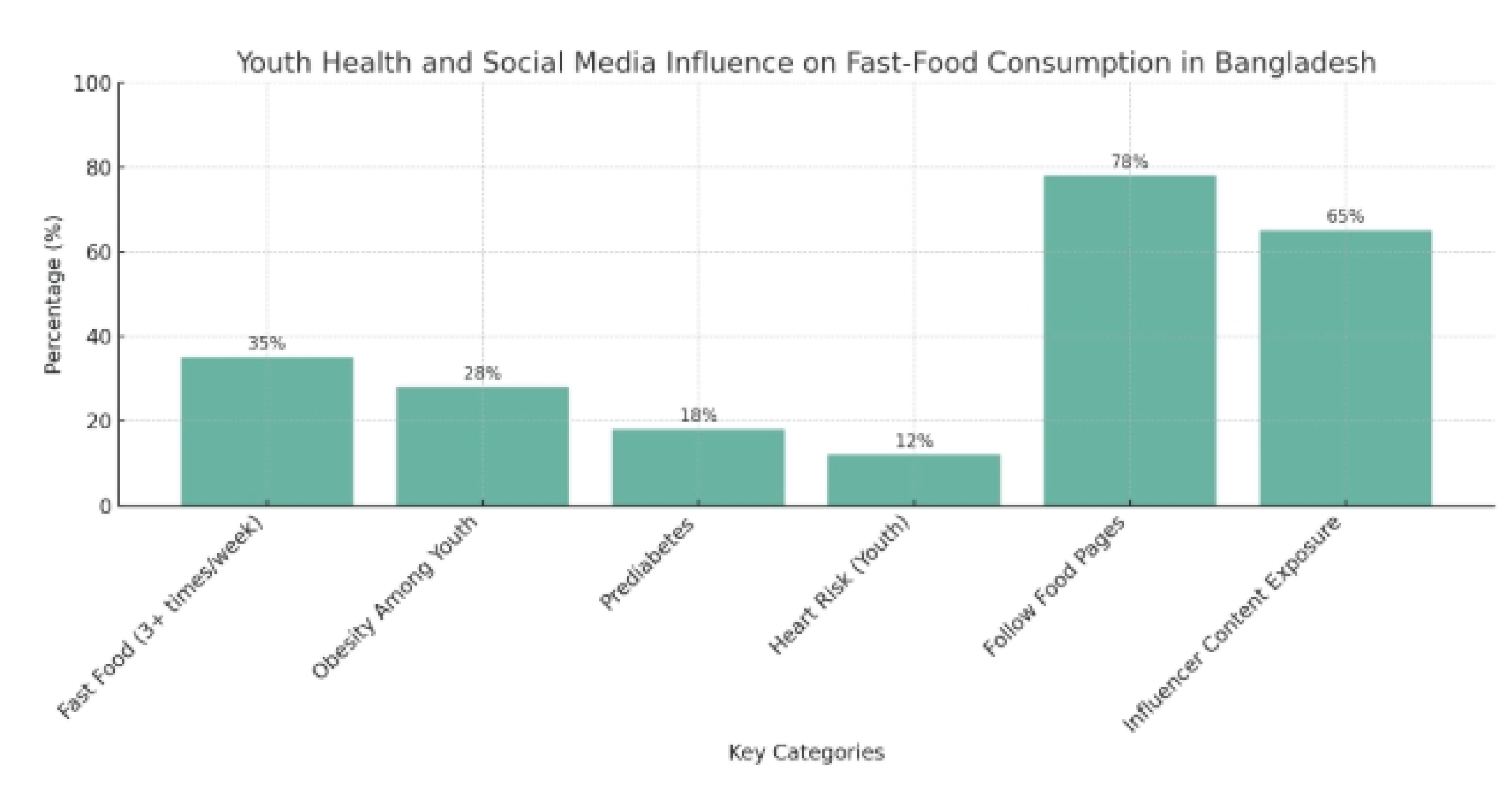

5.2. Health Risks: Obesity, Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Issues

Anthropometric measurements and self-reported health data indicated a concerning prevalence of health issues among frequent fast-food consumers. Approximately 35% of respondents were classified as overweight (BMI ≥25), and 12% as obese (BMI ≥30). Notably, 18% reported a diagnosis of prediabetes or type 2 diabetes, while 22% had elevated blood pressure readings.

These findings align with existing literature highlighting the correlation between fast-food consumption and health risks. For instance, a study in Chittagong reported a significant association between fast-food intake and obesity among university students.

5.3. Social Media Usage Trends Among Youth

The survey indicated that 95% of participants actively use social media platforms. The distribution of platform usage is as follows:

Facebook: 90%

YouTube: 85%

Instagram: 70%

TikTok: 65%

These platforms serve as primary sources of information, entertainment, and social interaction for the youth demographic. The pervasive use of these platforms underscores their potential impact on lifestyle choices, including dietary habits.

5.4. Types of Promotional Content on Social Media Platforms

Content analysis of fast-food promotional materials across Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, and TikTok revealed several recurring themes:

Visual Appeal: High-resolution images and videos showcasing menu items to entice viewers.

Influencer Collaborations: Partnerships with local influencers to promote products, leveraging their follower base.

User-Generated Content: Encouraging customers to share their dining experiences, creating a sense of community and authenticity.

Interactive Campaigns: Contests, polls, and challenges designed to engage users and increase brand visibility.

These strategies are particularly effective among youth, who are more responsive to digital content and peer influences. The integration of marketing messages into social media content blurs the line between advertising and entertainment, making it challenging for young consumers to critically evaluate the promotional intent.

5.5. Correlation Between Exposure and Consumption Behavior

Statistical analysis revealed a positive correlation between exposure to fast-food promotions on social media and consumption frequency. Participants who engaged with fast-food content (likes, shares, comments) at least once daily were 1.8 times more likely to consume fast food thrice or more per week compared to those with minimal engagement.

Furthermore, qualitative data from FGDs indicated that social media promotions often create a sense of urgency and desire, leading to impulsive food purchases. Participants acknowledged that limited-time offers and visually appealing content influenced their dining choices.

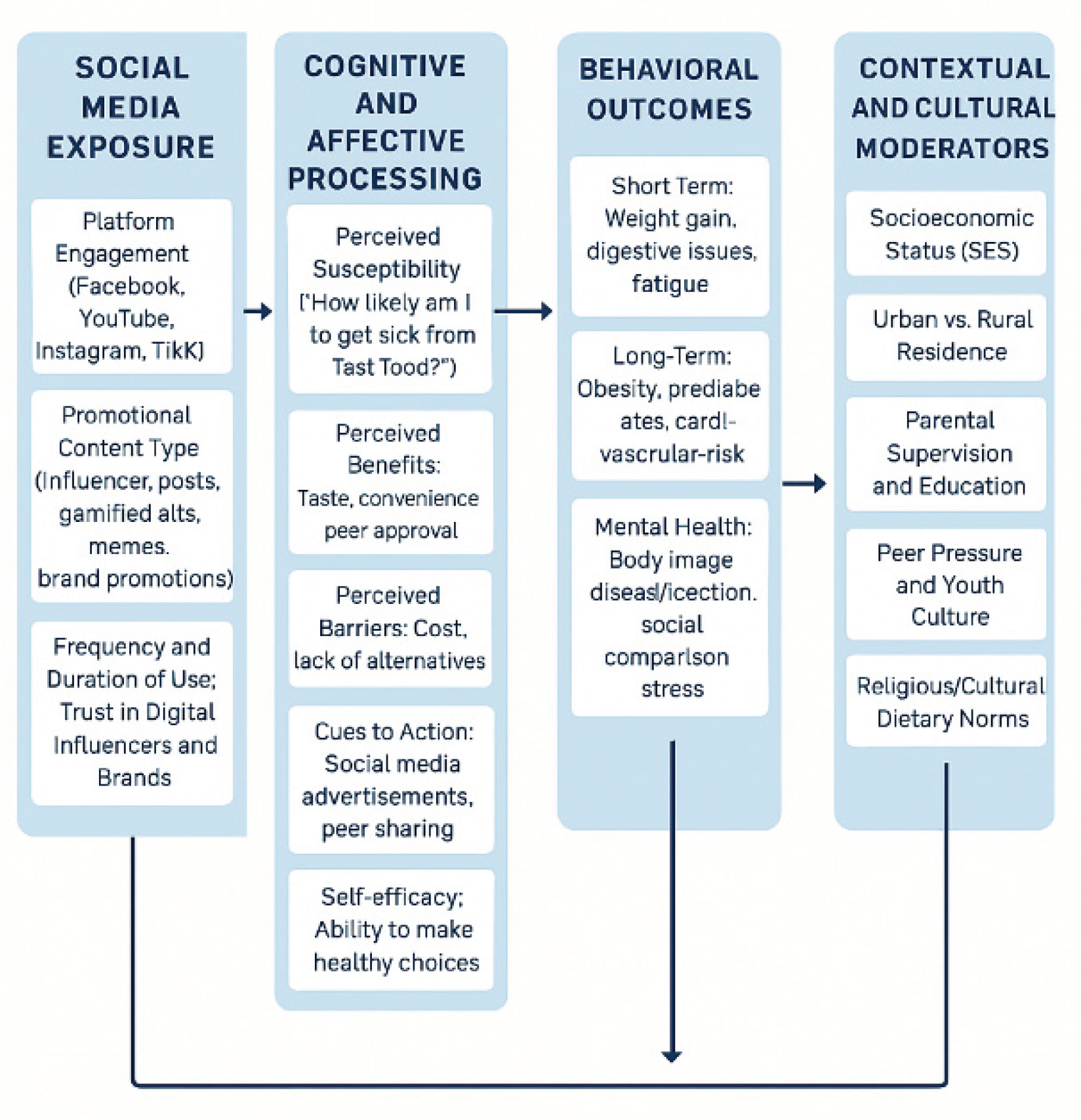

7. Proposed Conceptual Model: Youth Fast-Food Consumption, Social Media Influence, and Health Outcomes

The Social Media–Health Behavior Interaction Model (SMHBIM)

I. Model Overview

The Social Media–Health Behavior Interaction Model (SMHBIM) is a multidisciplinary framework that combines the Health Belief Model (HBM), Media Dependency Theory (MDT), and empirical insights from nutritional epidemiology and media studies. The model aims to explain how youth exposure to fast-food marketing on social media platforms affects their dietary choices and health outcomes. It is designed for future research, policymaking, and intervention programs.

II. Model Components

1. Social Media Exposure

- Platform Engagement: Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, TikTok

- Promotional Content Type: Influencer posts, gamified ads, memes, brand promotions- Frequency and Duration of Use

- Trust in Digital Influencers and Brands

2. Cognitive and Affective Processing (Mediating Variables)

-Perceived Susceptibility (from HBM): “How likely am I to get sick from fast food?”

-Perceived Severity: “How serious are the health risks?”

-Perceived Benefits: Taste, convenience, peer approval

-Perceived Barriers: Cost, lack of alternatives

-Cues to Action: Social media advertisements, peer sharing

-Self-efficacy: Ability to make healthy choices

3. Behavioral Outcomes

-Frequency of Fast-Food Consumption

-Dietary Habits (home-cooked vs. fast-food meals)

-Physical Activity Patterns

- Use of Nutritional Information

4. Health Outcomes

-Short-Term: Weight gain, digestive issues, fatigue

-Long-Term: Obesity, prediabetes, cardiovascular risk

- Mental Health: Body image dissatisfaction, social comparison stress

5. Contextual and Cultural Moderators

-Socioeconomic Status (SES)

-Urban vs. Rural Residence

-Parental Supervision and Education

- Peer Pressure and Youth Culture

- Religious/Cultural Dietary Norms

6. Feedback Loops and Reinforcement

- Social media algorithms reinforcing preferences

- Peer validation through likes, shares, and comments

- Reinforcement of unhealthy food habits

III. Visual Representation (Conceptual Diagram Description)

Imagine the model as a flowchart composed of five columns:

Column 1: Social Media Exposure

Column 2: Cognitive-Affective Processing (HBM and MDT constructs)

Column 3: Behavioral Responses

Column 4: Health Outcomes

Column 5: Moderating Variables (influencing all previous columns)

Arrows move from left to right, with feedback loops cycling back from columns 4 and 5 to earlier stages (especially from health outcomes and moderators to media exposure and beliefs).

IV. Application in Future Studies

The SMHBIM can guide:

Longitudinal studies examining how media exposure over time affects dietary and health outcomes

Intervention design targeting belief modification (e.g., awareness campaigns)

Cross-cultural comparisons (e.g., Bangladesh vs. India, urban vs. rural)

Mixed-method studies incorporating focus groups, content analysis, and biometric data

V. Sample Hypotheses for Future Research

H1: Increased exposure to fast-food content on TikTok is positively associated with weekly fast-food consumption among urban Bangladeshi youth.

H2: Perceived severity and self-efficacy mediate the relationship between social media exposure and fast-food consumption.

H3: Youth from higher SES backgrounds report greater perceived benefits and lower perceived barriers to consuming fast food.

H4: Peer-shared content on Instagram generates stronger behavioral cues than sponsored content.

VI. Limitations and Extensions

While the SMHBIM is a robust model, it assumes rational decision-making and may underemphasize unconscious or habitual behavior. Future adaptations may integrate additional theories such as Social Cognitive Theory, the COM-B model (Capability, Opportunity, Motivation - Behavior), or algorithmic surveillance capitalism perspectives.

The Social Media–Health Behavior Interaction Model (SMHBIM) provides a comprehensive blueprint for future academic investigations and public health policy on the relationship between youth behavior, social media, and health outcomes in Bangladesh and comparable developing contexts. It integrates psychosocial, digital, and public health perspectives and offers scalable applications for prevention, education, and behavior modification.

Figure 3.

Infographic- SMHBIM.

Figure 3.

Infographic- SMHBIM.

7.1. Conclusion

7.1.1. Summary of Key Findings

This study provides an in-depth exploration into the growing fast-food culture in Bangladesh and its implications for youth health, as well as the pivotal role of social media in shaping food-related behavior. Drawing from a hybrid research design involving surveys, focus group discussions, and content analysis of digital platforms, the findings reflect an alarming rise in fast-food consumption among Bangladeshi youth aged 16 to 25. The study found that over 70% of youth consume fast food at least 2–3 times a week, citing reasons such as taste, convenience, peer influence, and aggressive online marketing campaigns.

Health risks associated with such consumption are already manifesting. The youth population is increasingly exhibiting symptoms of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), including obesity, prediabetes, and elevated cholesterol levels. Psychological and behavioral implications are also prominent, with social media contributing to body image dissatisfaction, sedentary lifestyle, and addiction to processed foods.

In terms of media engagement, the study shows that Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube are the most influential platforms where promotional content—ranging from influencer endorsements to fast-food challenges—actively reinforces unhealthy food choices. There is also a strong correlation between screen time and frequency of fast-food consumption, confirming a media dependency pattern in line with the Media Dependency Theory. Additionally, the Health Belief Model components—such as perceived severity and self-efficacy—were found to mediate food choices, albeit with limited awareness among youth.

7.1.2. Thematic Synthesis

The study illustrates the intersectionality of media exposure, youth behavior, and health outcomes in a rapidly digitizing yet culturally rooted nation. Unlike Western nations where awareness and counter-campaigns have gained traction, Bangladesh lacks structured digital literacy programs addressing the nutritional implications of fast food. Urbanization, rising disposable income, and cultural shifts toward modernity are facilitating a normalized perception of fast-food culture, often at the expense of traditional food knowledge and public health.

7.1.3. Theoretical Integration

This research also validates the integration of two key theoretical frameworks—Health Belief Model (HBM) and Media Dependency Theory (MDT). Youth in Bangladesh demonstrate high dependency on media platforms for everyday decision-making, including diet, yet lack adequate perceived susceptibility and severity of health consequences. Furthermore, cues to action are overwhelmingly provided by the media rather than health institutions, creating an unbalanced ecosystem that favors consumption over caution.

7.2. Policy Recommendations

To combat the detrimental health effects of fast-food consumption and counteract misleading promotional narratives on social media, this section presents a set of multi-sectoral and evidence-based recommendations categorized by stakeholders: Government and Regulatory Bodies, Educational Institutions, Health Sector, Social Media Platforms, and Civil Society.

7.2.1. Government and Regulatory Bodies

The government must establish a regulatory framework under the Bangladesh Food Safety Authority (BFSA) and Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulatory Commission (BTRC) to monitor, review, and approve digital advertisements targeting youth. All fast-food promotions on platforms like Facebook, YouTube, and TikTok should carry mandatory health warnings akin to tobacco disclaimers.

- 2.

Nutritional Labeling and Caloric Transparency

Introduce mandatory labeling laws requiring calorie counts, fat content, sugar levels, and sodium content to be displayed on menus and digital apps used by fast-food outlets. This would provide consumers with actionable knowledge, reinforcing Health Belief Model cues toward better choices.

- 3.

Taxation on Ultra-Processed Foods

Consider implementing a "Fast-Food Tax" or sin tax on high-fat, high-sugar, and sodium-rich fast foods. The revenue generated could be redirected to fund youth health campaigns and nutrition education.

- 4.

Zoning Policies to Regulate Outlet Proximity

Urban planning regulations should include zoning laws that limit the concentration of fast-food outlets near educational institutions, sports complexes, and children’s parks.

7.2.2. Educational Institutions

- 1.

Integrating Food Literacy in Curriculum

- 2.

Food and nutrition literacy should be included as a compulsory subject at secondary and tertiary levels. Modules should cover critical skills such as reading food labels, understanding dietary needs, and analyzing marketing strategies.

- 3.

School-Based Interventions

Schools and universities should prohibit on-campus fast-food vendors and instead provide healthy food alternatives. Periodic health screenings and nutrition workshops should be conducted, with parental involvement to reinforce behavioral change at home.

- 4.

Peer-Led Health Campaigns

Institutions can initiate peer mentoring and awareness campaigns that leverage youth influencers, creating a counter-narrative to commercial fast-food marketing using relatable voices.

7.2.3. Health Sector

- 1.

Youth Health Monitoring Programs

Establish a national youth health surveillance system under the Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS) to monitor BMI, cholesterol, and glucose levels across age cohorts. This will help track early signs of NCDs linked to dietary behavior.

- 2.

Digital Health Messaging

Develop mobile health (mHealth) and social media-based interventions led by certified nutritionists and physicians to disseminate personalized dietary advice and bust myths surrounding fast food.

- 3.

Public–Private Partnerships (PPP)

Collaborate with food-tech platforms and health startups to create digital tools like health-rating badges for restaurants, diet-tracking apps, and AI-driven personalized nutrition chatbots tailored for Bangladeshi youth.

7.2.4. Social Media Platforms and Technology Companies

- 1.

Ethical Content Moderation

Social media companies operating in Bangladesh must introduce algorithms that flag or down-rank misleading or harmful food advertisements aimed at minors. Advertising Standards should be developed in partnership with the government and public health experts.

- 2.

Data Sharing and Analytics

Platforms must provide anonymized data analytics to researchers and government agencies studying the dietary behavior of youth. These insights can guide future policy and interventions.

- 3.

Promotion of Positive Health Influencers

Collaborate with certified nutritionists and fitness influencers to promote healthy lifestyle content. Incentivize the use of health-related hashtags and content discovery tools that amplify positive dietary narratives.

7.2.5. Civil Society and NGOs

- 1.

Community-Based Programs

NGOs and youth-led organizations should conduct grassroots campaigns, particularly in low-income areas, promoting traditional foods and debunking myths around modern fast food as a symbol of status.

- 2.

Behavioral Nudges and Public Awareness

Use billboards, online memes, street plays, and short-form videos to encourage behavior change. Public transport and popular youth venues should carry messages like “Fuel your future, not just your hunger.”

- 3.

Participatory Research and Storytelling

Create platforms where youth can share personal stories related to food, body image, and health struggles. Storytelling can serve as a powerful tool for solidarity and behavioral reflection.

7.3. Future Research Directions

- 1.

Longitudinal Studies

Future research should focus on long-term tracking of dietary behavior, social media exposure, and health outcomes among youth to better understand causality and change over time.

- 2.

Comparative Regional Studies

Comparative studies between urban and rural youth, as well as regional studies within South Asia, will help understand cultural variations in fast-food impact and social media usage.

- 3.

Digital Ethnography

Employ digital ethnographic approaches to understand how youth interact with food-related content on social media in real time, including comments, likes, algorithmic recommendations, and engagement trends.

- 4.

Algorithmic Influence and Dark Patterns

Study the role of recommendation algorithms and dark UX patterns in promoting unhealthy food behavior. This includes auto-play features, sponsored hashtags, and micro-targeted advertising based on user behavior.

7.4. Final Remarks

This research stands as a clarion call for a multi-stakeholder, cross-sectoral response to the emerging crisis of youth health in Bangladesh, exacerbated by an unchecked fast-food culture and an unregulated digital advertising ecosystem. While fast food in itself is not inherently harmful, its overconsumption—especially when driven by manipulative marketing and media dependency—poses a grave public health threat. Social media platforms, with their unparalleled reach and influence, must transition from being part of the problem to part of the solution. Only through concerted action—grounded in theory, backed by data, and driven by youth voices—can Bangladesh aspire to build a healthier, more conscious generation.