1. Introduction

Fermented milk, made from raw milk or milk powder as the main ingredient and fermented by specific microorganisms, is a dairy product with a long history[1]. Fermented milks are highly appreciated by consumers due to their unique flavour, rich nutritional value and diverse health benefits[2]. In industrial production, fermented milks are usually made by fermentation with traditional fermenters (Lactobacillus bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus) [3-4]. This fermentation process is not only the basic method for making fermented milks, but also one of the easiest and safest ways to preserve food.

However, an in-depth study of the market for fermented milks obtained from traditional agent preparations revealed that consumers are still dissatisfied with traditional fermented milks in terms of taste consistency, texture, sensory and flavour[5-6]. Specifically, the deficiencies of traditional fermented milks in terms of water uptake, physical stability, and texture have led to deficiencies in taste and quality. These problems not only affect consumers’ consumption experience, but also limit the competitiveness of traditional fermented milks in the market.

Co-fermentation of strains is a method of mixing two or more lactic acid bacteria for the preparation of fermented milk[7]. It mainly takes advantage of the mutually beneficial symbiotic or partial symbiotic relationship between microbial groups, and is used to balance the advantages of different strains and avoid the problem of insufficient flavour or poor texture when fermented with a single strain[8-9]. Currently, this method has made some progress in improving the deficiencies of traditional fermented milks. Li et al. used co-fermentation of Lactobacillus plantarum, Bifidobacterium animalis and Streptococcus thermophilus in the preparation of fermented milk, and the results of their study showed that the milk fermented by co-culturing of three strains exhibited higher cohesion, more volatility and better organoleptic qualities compared with the fermented milk cultured by Streptococcus thermophilus only[8]. Li et al. demonstrated that yoghurt containing Lactobacillus plantarum with traditional fermenters was more concentrated and had a more complete texture than yoghurt prepared with P. pentosaceus and E. faecium. The determination of volatile compound profiles showed that the diversity of volatile compounds was higher than that of the traditional fermenter group[10]. Nonetheless, recent studies have shown that the fermented milks prepared by such strains do not fully satisfy the consumers’ demands for silky texture and diversified nutrients, and therefore, further searching for suitable strains to improve the quality of fermented milks is an urgent issue[7-8].

Clostridium butyricum (CB), a Gram-positive, spore-producing, anaerobic probiotic, is widely used in food, feed and medicine because of its ability to inhibit harmful bacteria, promote the proliferation of beneficial bacteria and repair intestinal mucosa[11-13]. It is worth our attention that the metabolites of CB can stimulate the growth of lactobacilli and promote the proliferation of beneficial bacteria, and compounding it with lactobacilli is likely to benefit the fermentation of milk and ultimately improve the quality of fermented milk[14].

Here, this study focuses on the effect of CB in the formation of fermented milk quality when compounded with traditional fermenters, using fermented milk as a vehicle. We used the treatment group with the addition of commercial fermenter only as a control (labelled Y) to investigate in depth the effect of different mass ratios of CB on the improvement of the quality of fermented milk with traditional fermenter. These were assessed in terms of acidification capacity, number of viable bacteria, water uptake, protein hydrolysis activity, rheological properties, physical stability, microstructure, volatile flavour substances, and changes in organoleptic properties. This study aims to provide scientific basis and practical reference for the industrial production of probiotic fermented milk.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Physicochemical Properties of Fermented Milk

Bulleted lists look like this: The type of fermenter determines the fermentation activity between it and cow’s milk and consequently affects the physicochemical and textural properties of fermented milk[15]. Therefore, in this study, fermented milks prepared using different fermenters were analysed in detail using FT-IR.

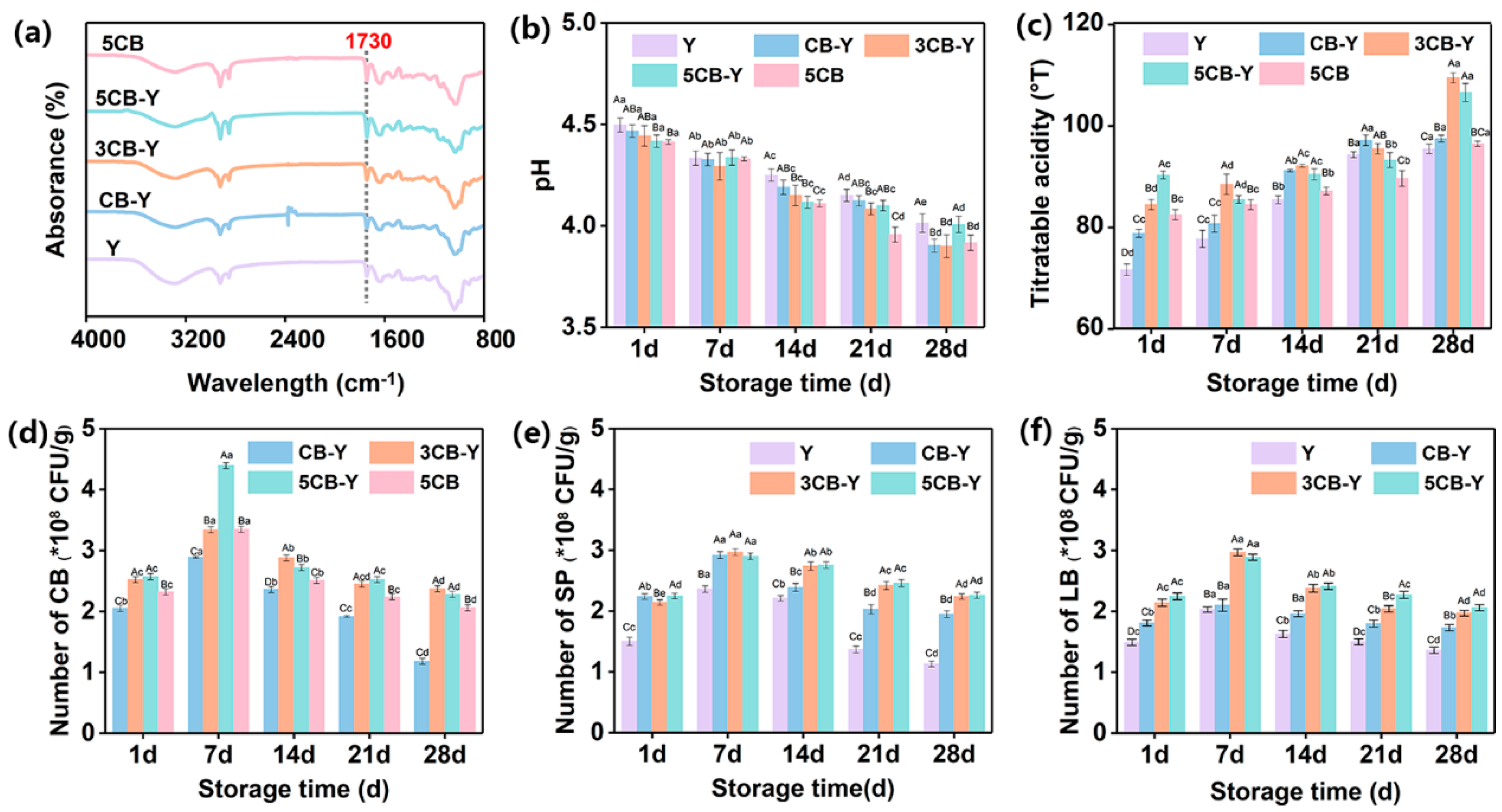

Figure 1a demonstrates the FT-IR profiles of fermented milks. Compared with group Y, the experimental groups with CB addition all showed enhanced characteristic absorption peaks at 1730 cm-¹, which was attributed to the carboxyl group[16], confirming the successful introduction of Clostridium butyricum into the fermented milk. In addition, the intensity of this characteristic absorption peak gradually increased with the increment of CB addition, which indicated that the number of Clostridium butyricum increased. This observation is in complete agreement with the description in

Figure 1d, further validating the reliability of the experiment.

Measurement of acidification capacity is essential to assess how quickly different fermenters produce acid in the fermentation system. The results of pH and titratable acidity changes of fermented milks during refrigeration are shown in

Figure 1 b,c. It is evident from

Figure 1b that a significant decrease (P<0.05) in the pH of the fermented milks of all groups was observed with the extension of the refrigeration period. The pH of the samples in all groups was lower than that of the control (Y) throughout the storage period. In the co-culture system, the pH of the samples showed a gradual decrease with the gradual increase of CB addition. Particularly, there was no significant difference in pH between CB-Y and 3CB-Y groups at 28 days, whereas the group with excessive CB addition (5CB-Y) had a relatively high pH (>4.0), which may be attributed to the co-action of CB with conventional fermenters in the milk matrix, which promotes the decomposition of lactose and the accumulation of lactic acid[17]. Meanwhile, the titratable acidity of fermented milk increased significantly in all groups with the prolongation of refrigeration time (e.g.,

Figure 1c), and this upward trend was echoed by the significant downward trend of pH (e.g.,

Figure 1b). Among them, the titratable acidity (

oT = 109.5) of the 3CB-Y group was significantly higher than that of the other groups during the storage period, which could be attributed to the fact that the appropriate concentration of CB stimulated the growth of lactic acid bacteria and enhanced their metabolic acid-producing ability.

The number of viable lactic acid bacteria largely determines the quality, nutrient content and taste of fermented milk, and is closely related to its storage stability[18-19]. Therefore, we further examined the content of CB in fermented milk in detail. The results, as shown in

Figure 1d, showed an overall trend of increasing and then decreasing CB counts in fermented milk. Among them, the 3CB-Y group reached the highest CB content (2.37 × 10

8 CFU/g) at the 28th day, which may be due to the mutually beneficial symbiotic relationship between CB and traditional fermenter, which promotes the metabolism and reproduction of CB. At the later stage of storage (>14 d), the CB content decreased, which may be due to the increased acidity of the yoghurt system (pH <4), which inhibited the growth and metabolism ability of the complex bacteria. The changes in the numbers of Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus bulgaricus are shown in

Figure 1e,f. The numbers of Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus bulgaricus in the CB-added groups (CB-Y, 3CB-Y, and 5CB-Y) increased with the increase in the addition of the complex bacteria and were significantly higher than that of the Y group containing only the traditional fermenter (P < 0.05) during the same storage time. This again indicates that CB can promote the growth and reproduction of Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus bulgaricus and that this promotion is positively correlated with the amount of composite bacteria added. Taken together, it was concluded that the addition of 3×10

8 CFU/g of compound bacteria could effectively promote the metabolism and propagation of Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus bulgaricus in fermented milks, which in turn was expected to improve the textural properties and organoleptic qualities of traditional fermented milks.

2.2. Quality Characteristics of Fermented Milk

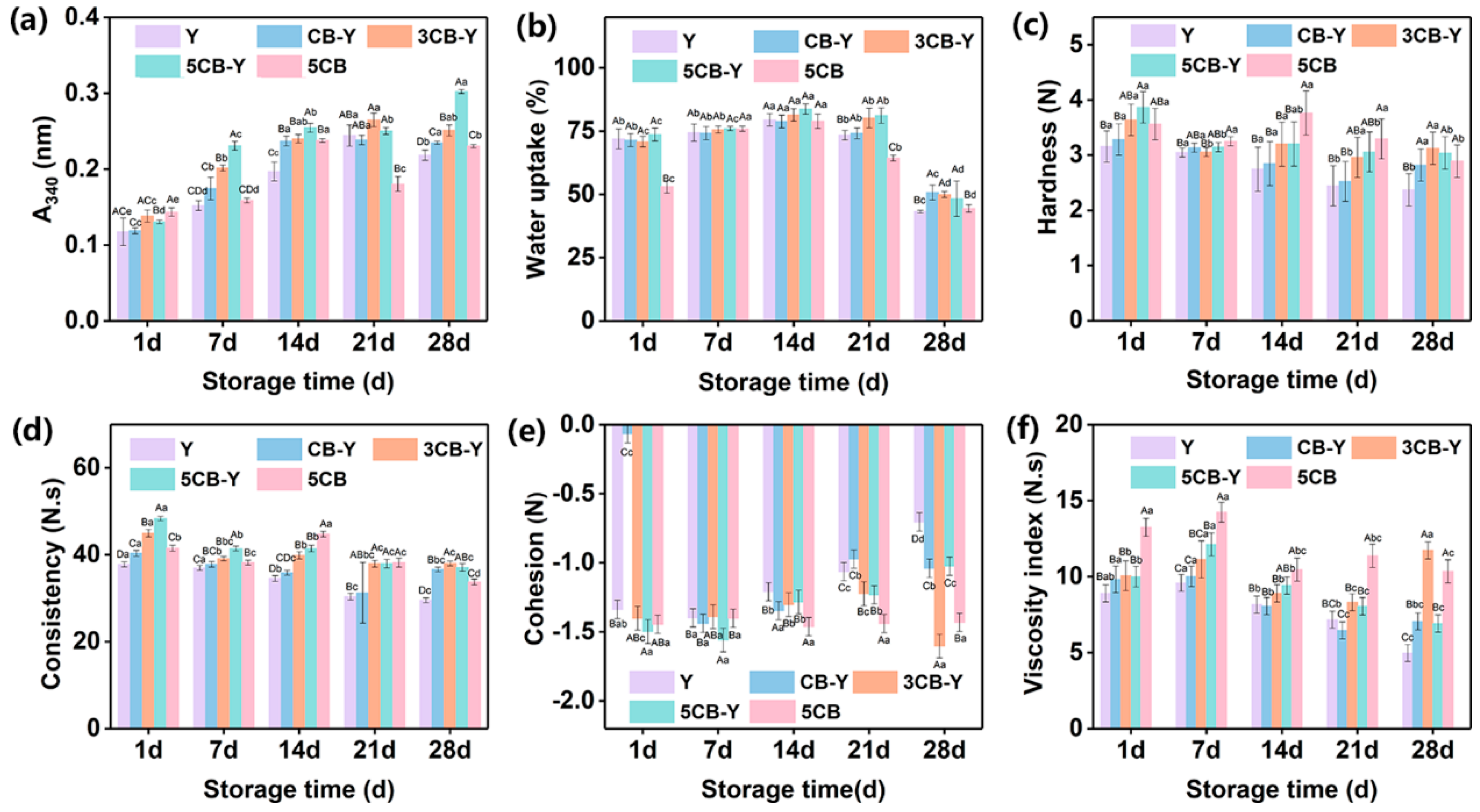

Lactic acid bacteria degraded milk proteins through their own protein hydrolysis system, which not only satisfied their own growth requirements, but also significantly improved the flavour and texture of the fermented milk by releasing free amino acids and small peptides, a process that plays a key role during both fermentation and storage of yoghurt[20-21]. As can be observed from

Figure 2a, the fermented milks from the co-fermentation group were significantly better than those from the Y group in terms of protein hydrolysis vigour. In particular, the CB-Y and 3CB-Y groups showed a significant increase in protein hydrolysis vigour from 1 to 14 days after fermentation, whereas there was no significant difference (P>0.05) during the subsequent refrigeration period. Interestingly, the protein hydrolysis vigour of the 5CB-Y group continued to elevate throughout the storage period. This shows that the protein hydrolysis viability of fermented milk is closely related to the amount of CB, and in the future, we can consider adjusting the amount of CB added in the co-fermentation system to precisely regulate the protein hydrolysis viability of fermented milk.

Water uptake has a profound effect on the organisational state of fermented milks as well as on the sensory experience of consumers, and it is also an important criterion for evaluating the texture and mouthfeel of fermented milks[22]. Because of this, we conducted an in-depth study on how the addition of CB affects the water uptake of fermented milk. As shown in

Figure 2b, the water uptake of fermented milk showed a small increase and then a significant decrease with storage time in different experimental groups. In particular, the water uptake of the experimental group with added CB significantly exceeded that of the control group (Y), and the strength of water uptake showed a significant positive correlation with the amount of CB added. Further comparing the microstructures of the fermented milks from the low water uptake groups (Y, 5CB group) and the high water uptake groups (CB-Y , 3CB-Y and 5 CB-Y) (

Figure 3), it can be observed that the fermented milks from the high water uptake groups (CB-Y , 3CB-Y and 5 CB-Y) formed a richer structure of porous network. This structure significantly enhanced the protein-water binding capacity of the fermented milks, which improved the texture and mouthfeel of the fermented milks, and provided consumers with a superior consumption experience.

The hardness of fermented milk is the force required to bring it to a specific deformation, which reflects the strength of the fermented milk gel network structure as well as its chewability[23].

Figure 2c demonstrates the change in hardness of fermented milk in each experimental group during storage. The addition of CB (some ingredient) significantly increased the hardness of fermented milk compared to the control group (group Y). This may be due to the fact that CB promoted further polymerisation of proteins such as casein in the fermented milk to form a more compact and stable three-dimensional network structure (as shown in

Figure 3), thus increasing the hardness of the fermented milk. In addition, the hardness of the CB-added fermented milk groups (CB-Y, 3CB-Y, 5CB-Y) increased with the increase of CB addition during the same storage time, which demonstrated the important role of CB in enhancing the hardness of fermented milks and improving the quality of fermented milks (e.g., chewiness).

Viscosity and viscosity index are important factors that affect the flavour and stability of the product during the production of fermented milk[24].

Figure 2d shows the variation of viscosity and viscosity index of different groups of yoghurt during storage. It can be seen from the figure that the viscosity of all experimental groups (CB-Y, 3CB-Y, 5CB-Y) was significantly higher than that of control group Y (viscosity of 29.51 N-s) during the whole storage period. In particular, the fermented milk showed the best viscosity (37.99 N-s) after 28 days when Clostridium butyricum was added up to 3 × 108 CFU/g at the same storage time. This was mainly due to the fact that the appropriate pH promoted the polymerisation of milk proteins, which led to the formation of a tighter cross-linked network structure (shown in

Figure 3) in the 3CB-Y fermented milk, thus significantly enhancing the viscosity (shown in

Figure 2d) and viscosity index (shown in

Figure 2e) as well as the cohesive force (shown in

Figure 2f) of the fermented milk. In contrast, the 5CB group inhibited the growth of microorganisms due to the excessively low pH, which led to insufficient cross-linking reactions in the fermented milk, excessive film formation of the fermented milk, and ultimately a decrease in its viscosity and viscosity index.The Y and CB-Y groups had insufficient numbers of Clostridium butyricum, and the mutualistic symbiosis between the traditional fermenter and Clostridium butyricum was weak, making it difficult to effectively promote the metabolism and reproduction of both parties, resulting in inadequate fermentation, which finally resulted in a decline in the fermented milk’s The viscosity, viscosity index and cohesion of the fermented milk were reduced.

2.3. Textural Properties of Fermented Milk

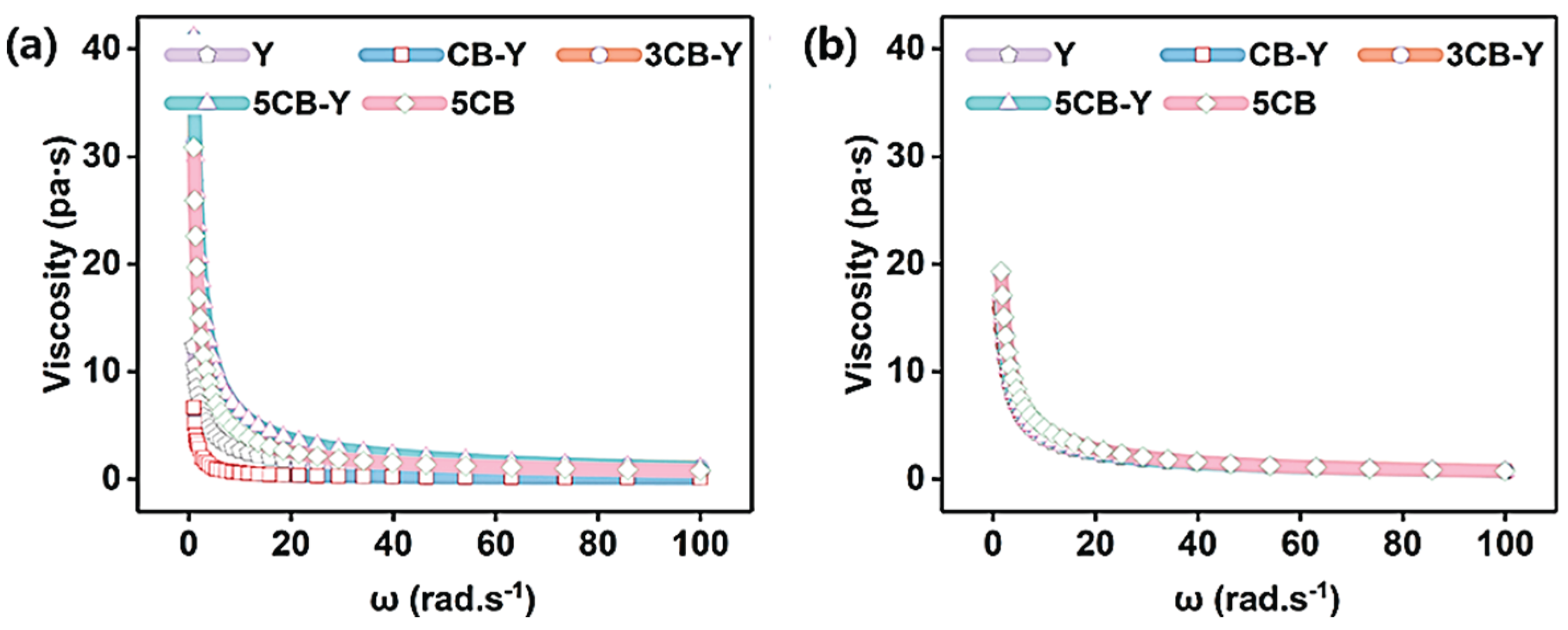

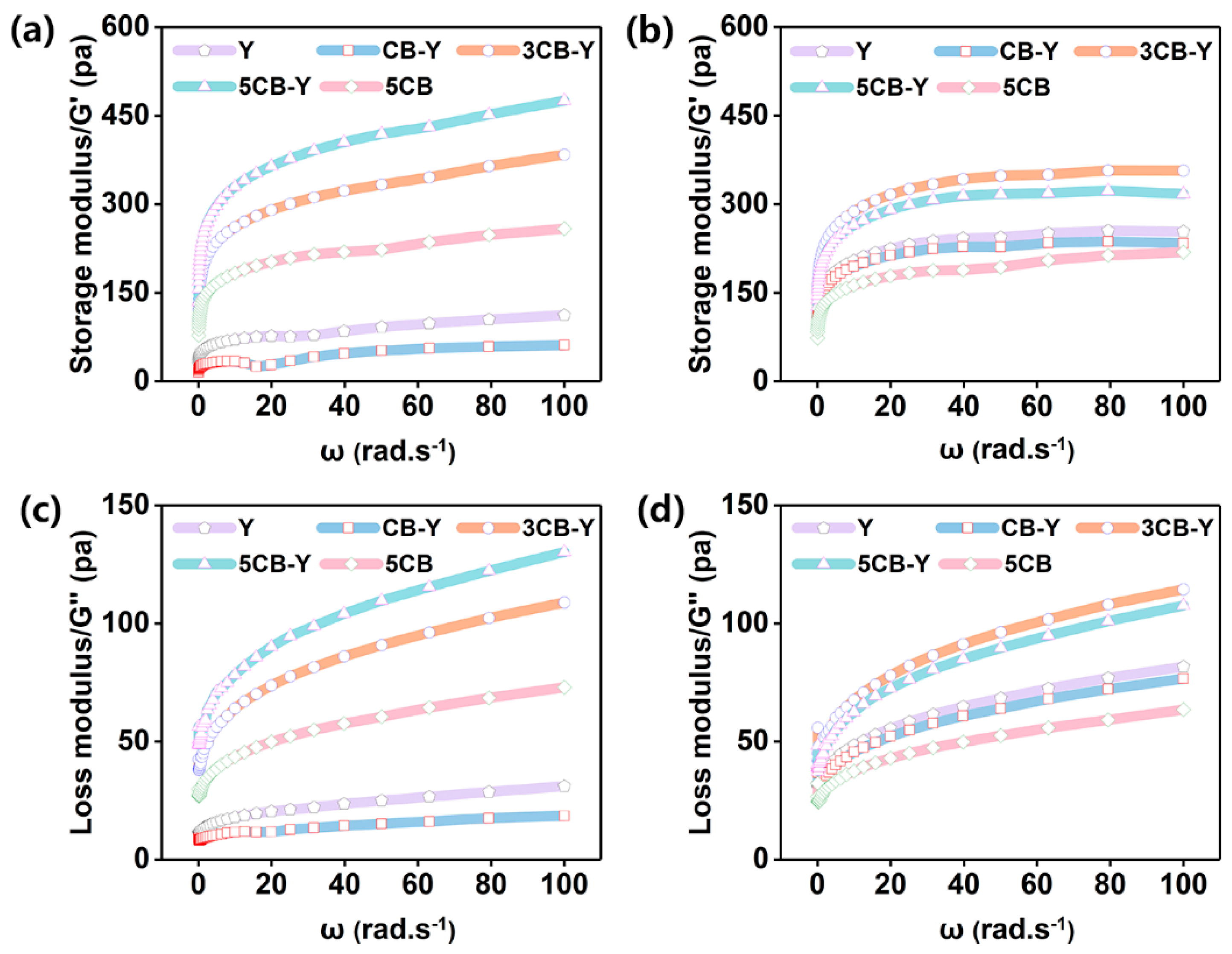

Storage modulus (G′) reflects the degree of deformation that occurs when an object is subjected to an external force, and is an important indicator of the elastic deformation capacity of fermented milk[25]. Loss modulus (G′′), on the other hand, indicates the property of an object that hinders its flow when subjected to an external force, and to a certain extent, it can reflect the viscosity of the fermented milks; a higher G′′ implies that there is a greater resistance to the flow of an object when subjected to an external force[26]. As can be seen from

Figure 4, the energy storage modulus (G′) is larger than the loss modulus (G′′) for all groups of fermented milks, which suggests that the network structure of fermented milks is more stable and able to maintain its original shape under the destructive action at high frequencies, and is more inclined to exhibit solid properties. It is worth noting that the moderate addition of CB (3CB-Y,5CB-Y) significantly enhanced the energy storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G′′) of the fermented milks compared with that of group Y. This suggests that the cross-linking between proteins is stronger in the fermented milks added with appropriate concentrations of CB, resulting in the formation of a denser cross-linking network structure (

Figure 3), which leads to fermented milks displaying more excellent rheological properties (

Figure 4, S1). From the time dimension, the energy storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G′′) of the fermented milk on day 28 were significantly lower than those on day 1, which may be attributed to the mutually beneficial symbiosis between CB and traditional fermentation agents, which promoted the hydrolysis of proteins in the fermented milk, released more small-molecule active peptides, and generated extracellular polysaccharides, which ultimately led to a denser cross-linking network structure of the fermented milk (shown in

Figure 3), and its modulus was significantly better than that of group Y, thus conferring a thicker texture to the fermented milk.

The instability index is an important indicator of emulsion stability. Under the same conditions, the closer the instability index tends to 1, the faster the fermented milk separates and the less stable it is[8]. Based on the data in

Table 1, we observed a significant decrease (<0.83) in the instability index for groups 3CB-Y and 5CB-Y during days 21 to 28 compared to days 1 to 7. Whereas, for groups Y, CB-Y and 5CB, there was no significant change in instability indices during each adjacent refrigeration time period and these indices were > 0.9. This suggests that the stability of fermented milks can be significantly enhanced by the addition of CB in appropriate amounts of 3×10

8 CFU/g and 5×10

8 CFU/g. The reason for this is that the appropriate CB addition promotes the symbiotic relationship between the bacteria in the fermented milk, which enables the proteins in the milk to be hydrolysed more adequately, resulting in a more stable gel network of the fermented milk (shown in

Figure 3), and improves the water-holding capacity of the fermented milk (shown in

Figure 2b).

2.4. Flavours of Fermented Milk

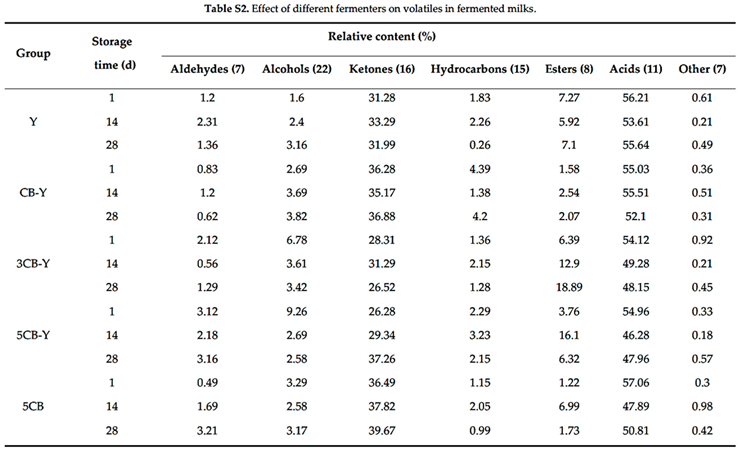

Flavour is one of the key indicators for evaluating the quality of fermented milk[7-8]. Using the GC-MS coupling technique, we carried out an exhaustive determination of volatile flavour substances in fermented milk, and a total of 86 volatile flavour substances were identified (

Table S2). These flavour substances included aldehydes (7), alcohols (22), ketones (16), hydrocarbons (15), esters (8), acids (11), and other compounds (7). Ketones, acids, and esters accounted for a large proportion as the main flavouring substances in the studied groups of fermented milks.

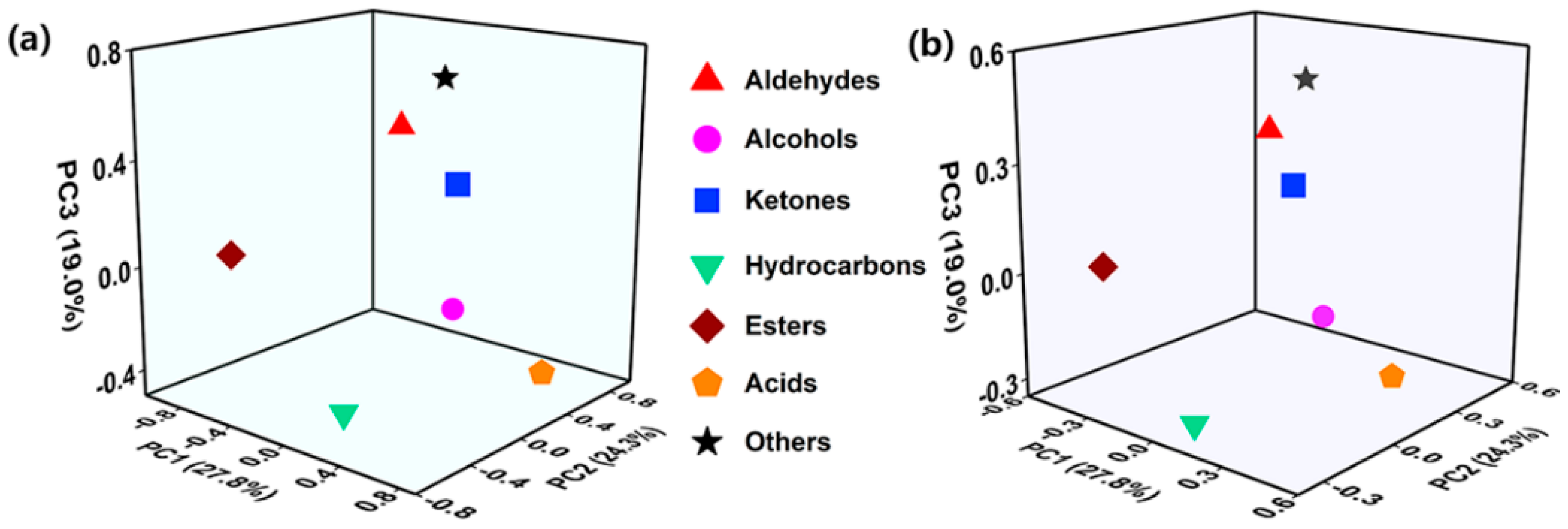

For the principal component analysis of

Table S2, the substance species with an eigenvalue greater than 1 and a cumulative contribution of more than 70% were selected as principal components (as shown in

Table 2). According to the PCA loading diagram of volatile flavour substances (

Figure 5a), the volatile flavour substances of fermented milk could be refined into three principal components. The first principal component (PC1), with a contribution of 27.78%, was mainly composed of ketones, hydrocarbons, acids and other substances; the second principal component (PC2), with a contribution of 24.25%, was mainly composed of aldehydes, alcohols, acids and other substances; and the third principal component (PC3), with a contribution of 19.01%, was mainly composed of aldehydes, ketones and other substances. It can be observed from

Figure 5b that fermented milks with different treatments showed significant differences in scores at different storage periods. The synergistic effect of CB and conventional fermenters significantly altered the scores of the main components at days 1, 14 and 28 of the storage period, especially the 5CB-Y group with CB incorporation of 5×10

8 CFU/g showed particularly good performance of acids, which is expected to further improve the taste of the fermented milk. Overall, CB incorporation is crucial for the formation of flavour in probiotic fermented milks.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Microbial Strains and Their Activation

Traditional yogurt fermenter (Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus bulgaricus mixture) was purchased from Hebei Yiran Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Hebei, China). Clostridium butyricum (CB) CICC-23847 was acquired from China Center of Industrial Culture Collection (Beijing, China). Prior to use, CB was recovered in 0787 Reinforced Closrridium Medium (Hangwei, Hangzhou, China) at 37 °C for 24 h. The active cultures after two successive transfers were further inoculated in milk medium for 6-7 h at 37 °C, which allowed for initial population of 108 CFU/g after milk inoculation.

3.2. Fermented Milk Preparation

The fermented milks were prepared according to a reported procedure with minor modification[27]. Fresh milk (6.0% fat, 6.0% protein, 2.0% carbohydrates, New Hope Dairy, Chengdu, China) mixed well with 5.0% sucrose (Taikoo, Shanghai, China) were preheated to 60 °C. The mixture was homogenised at 1000 Rpm with a high-speed disperser (Scientz, Ningbo, China), then thermally treated in a water bath incubator at 90 °C for 10 min, and cooled down to 43-45 °C. Subsequently, the cultures were added into treated milk in accordance with the treatments, mixed thoroughly and sub-packaged with glass bottles, and incubated at 42 °C until milk solidified by monitoring the pH value approximately 4.6. Then, the fermented milk samples were stored at 4±1 °C and analysis were conducted for storage of 1, 7, 14, 21, and 28 days.

According to the composition of the fermenters in

Table 1 different lactic acid bacteria were added to the milk. Among them, the blank group (Y) used only the conventional fermenter added at 0.1% (w/w) of the buttermilk mass; the fermented milks with different amounts of CB were labeled as CB-Y (1 × 10

8 CFU/g of CB and 0.1% of Y in buttermilk mass meter), 3CB-Y, and 5CB-Y, respectively; the experimental control was made using only 5CB.

3.3. Determination by FT-IR

The freeze-dried fermented milk samples and KBr were ground at a mass ratio of 1:100, pressed into tablets and placed on an FT-IR spectrometer (Frontier, Perkinelmer, America) for data acquisition[28]. The scanning band was 500~4000 cm-1, the scanning time was 32 s, and the resolution was 4 cm-1.

3.4. Determination of Acidification Capacity

The pH of fermented milk was determined using a pH meter (PHS-3C, INASE Scientific Instrument CO.,LTD, China). The titratable acidity of fermented milk was tested by titration method[8]. 5.0 g of fermented milk was mixed with 5 ml of deionized water, 2 drops of 0.5% phenolphthalein (95% ethanol solution as solvent) were added, and then the sample was titrated with 0.1 mol/L NaOH standard solution until the color changed to a light pink. The titratable acidity (°T) is calculated from the amount of NaOH standard solution consumed.

3.5. Determination of Viable Bacteria Count

The number of viable bacteria in fermented milk was tested by dilution smear plate method[29]. 25 g of fermented milk sample was mixed with 225 mL of saline. After aspirating 1 mL of the bacterial solution and diluting it with saline to the appropriate magnification, plate counts of Lactobacillus bulgaricus, Streptococcus thermophilus and Clostridium butyricum were carried out using MRS medium, MC medium and CE medium, respectively. The number of surviving lactic acid bacteria was expressed as CFU/g of fermented milk.

3.6. Determination of Protein Hydrolysis Activity

The protein hydrolysis activity in fermented milk was tested by ninhydrin colorimetry[30]. 1 g of fermented milk and 9 ml of deionized water were mixed at 4 °C for 30 minutes at a centrifugal force of 3000 g. Then, the supernatant of the fermented milk was stained with ninhydrin reagent. Protein hydrolysis activity was estimated from the absorbance of L-leucine standards (0-0.21 m/M) at 507 nm (AoE, Shanghai, China).

3.7. Determination of Water Uptake (WU)

The WU of fermented milk was determined by centrifugation[31]. A certain mass (W

0) of fermented milk sample was taken in a centrifuge (5804R, eppendorf, Germany) and centrifuged at 8000 × g for 15 min (4 °C), the supernatant was decanted and the mass of the remaining sample (W) was weighed. WU was calculated according to equation (1).

3.8. Determination of Texture and Structure

The texture and structure of fermented milk were determined using a texture meter (ENS-TDV, Innovate, China). Fermented milk samples (diameter 50 mm × height 80 mm) were equilibrated to room temperature (20 ± 2 °C). An A/BE piston probe of 35 mm was used to compress the fermented milk by 30 mm, and the probe was operated at a rate of 1.0 mm/s with a trigger force of 10.0 g[32].

3.9. Determination of Microstructure

The surface morphology of the fermented milk samples was analyzed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, Phenom ProX, Netherlands.). Taking 0.1 g of the powder sample in the sample chamber of the MSP-1S ion sputtering instrument, gold was sprayed at a current of 5~8 mA for 1 min. Then the surface morphology was observed by SEM with an accelerating voltage of 15.00 kV[33].

3.10. Determination of Rheological Properties

The rheological properties of fermented milk were determined by rheometer (DHR-1, TA, America). The experimental conditions were as follows: frequency scanning at 25 ℃, angular frequency from 0.1-100 rad/s, with 16 points of each order of magnitude; shear scanning at 25 ℃, with the shear rate increased from 1 to 100 s-1, with 25 points of each order of magnitude[34].

3.11. Determination of Physical Stability

The stability of fermented milk was determined by a stability analyzer (LUMiSizer611, LUM, Germany). Pipette 0.5 mL of fermented milk was placed in a 2 mm PC tube, the light source wavelength was 865 nm, the number of spectral lines was 255, the time interval was scanned every 10 s, the rotational speed was 2500 r/min, and the temperature was 25 ℃ for the detection[8].

3.12. Determination of Volatile Flavorants

Volatile flavors of fermented milk were analyzed by GC-MS (TrPluS RSH SMART, Thermo, America) [35]. Put 5 g of fermented milk sample into a headspace injection bottle. Add sodium chloride (2 g), seal the bottle, and after a 10-minute pre-incubation, adsorb the sample for 30 minutes using the extraction tip. Finally, the sample is analyzed at 220°C for 3 minutes to ensure accurate results. Chromatographic conditions: A TR-FFAP column (30 m×0.25 mm×0.25 μm) was used with a carrier gas of 99.999% helium at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min.

4. Conclusions

Herein, the effect of CB combined with traditional fermenter on the physicochemical properties, protein hydrolysis activity, rheological properties, physical stability, microstructure and volatile flavour of fermented milk was investigated. Results of the study showed that the acidification capacity and the number of viable bacteria of fermented milk were significantly enhanced (P<0.05) in the CB-combined traditional fermenter fermentation group (3CB-Y) with moderate addition (3×108 CFU/g), compared with that in the group (Y) with single use of traditional fermenter. Meanwhile, on day 28, the water holding capacity of the 3CB-Y group was increased by 15.6% compared with that of the traditional fermenter group (Y), and the gel network structure of the fermented milk was finer, which enhanced the viscoelasticity of the fermented milk (viscosity reached 37.99 N.s), and ultimately improved the volatile flavouring compounds (86 volatile flavouring compounds were detected) and organoleptic quality of the fermented milk. In addition, the 3CB-Y fermented milk was significantly better than the traditional fermenter group (Y) and the high-dose CB group (5CB) in terms of acidification capacity, number of viable bacteria, physical stability and textural tests. This study demonstrated that CB combined with traditional fermenter has good improvement and developmental prospects for the texture, sensory and quality of fermented milk.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Writing, investigation, X.T.; software, methodology, Data curation, X.T.and L.D.; Conceptualization, S.L.; Writing–review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, S.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. ZYN2024147) and Sichuan Provincial Science and Technology Program (No. 2022YFG0030 and 2024YFTX0010).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the members in the investigator’s lab for helpful discussion,and also thank the Core Facilities and Service Centers, NIPB, CAMS&PUMC for assistance with ultracentrifugation work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Composition of Fermenter.

Table A1.

Composition of Fermenter.

| Group |

Composition of Fermenter |

| Y |

0.1% of conventional fermenter |

| 1CB-Y |

1 × 108 CFU/g of CB and 0.1% of conventional fermenter |

| 3CB-Y |

3 × 108 CFU/g of CB and 0.1% of conventional fermenter |

| 5CB-Y |

5 × 108 CFU/g of CB and 0.1% of conventional fermenter |

| 5CB |

5 × 108 CFU/g of CB |

Figure A1.

Effect of different fermentation agents on the apparent viscosity of fermented milks.

Figure A1.

Effect of different fermentation agents on the apparent viscosity of fermented milks.

Table A2.

Effect of different fermenters on volatiles in fermented milks.

Table A2.

Effect of different fermenters on volatiles in fermented milks.

References

- Peng J.Y.; Ma L.Q.; Kwok L.Y.; Zhang W.Y.; Sun T.S. Untargeted metabolic footprinting reveals key differences between fermented brown milk and fermented milk metabolomes, Journal of Dairy Science. 2022, 105, 2771-2790. [CrossRef]

- Teruel-Andreu C.; Jimenez-Redondo N.; Muelas R.; Carbonell-Pedro A.A.; Hernandez F.; Sendra E.; Cano-Lamadrid M. Techno-functional properties and enhanced consumer acceptance of whipped fermented milk with Ficus carica L. By-products Food Research International. 2024,195, 114959. [CrossRef]

- Moghimi B.; Dana M.G.; Shapouri R.; Jalili M. Antibiotic Resistance Profile of Indigenous Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus bulgaricus Strains Isolated from Traditional Yogurt. Journal of Food Quality. 2023, 1, 4745784. [CrossRef]

- Dan T.; Wang D.; Wu S.M.; Jin R.L.; Ren W.Y.; Sun T.S. Profiles of Volatile Flavor Compounds in Milk Fermented with Different Proportional Combinations of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophiles. Molecules. 2017, 22, 1633. [CrossRef]

- Heck A.J.; Schafer J.; Nobel S.; Hinrichs J. Fat-free fermented concentrated milk products as milk protein-based microgel dispersions: Particle characteristics as key drivers of textural properties. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 2021, 20, 6057-6088. [CrossRef]

- Yamase Y.; Huang H.; Mitoh Y.; Egusa M.; Miyawaki T.; Yoshida R. Taste Responses and Ingestive Behaviors to Ingredients of Fermented Milk in Mice, Foods. 2023, 12, 1150. [CrossRef]

- Li S.N.; Tang S.H.; He Q.; Hu J.X.; Zheng J. Changes in Proteolysis in Fermented Milk Produced by Streptococcus thermophilus in Co-Culture with Lactobacillus plantarum or Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis During Refrigerated Storage. Molecules. 2019, 24, 3699. [CrossRef]

- Li S.N.; Tang S.H.; He Q.; Gong J.X.; Hu J.X. Physicochemical, textural and volatile characteristics of fermented milk co-cultured with Streptococcus thermophilus, Bifidobacterium animalis or Lactobacillus plantarum. International Journal of Food Science & Technology. 2020, 55, 461-474. [CrossRef]

- Wang S.Y.; Huang R.F.; Ng K.S.; Chen Y.P.; Shiu J.S.; Chen M.J. Co-Culture Strategy of Lactobacillus kefiranofaciens HL1 for Developing Functional Fermented Milk. Foods. 2021, 10, 2098. [CrossRef]

- Li H.; Gao J.x.; Chen W.b; Qian C.j.; Wang Y.; Wang J.; Chen L.s. Lactic acid bacteria isolated from Kazakh traditional fermented milk products affect the fermentation characteristics and sensory qualities of yogurt. Food Science & Nutrition. 2022, 10, 1451-1460. [CrossRef]

- Kanchanasuta S.; Prommeenate P.; Boonapatcharone N.; Pisutpaisal N. Stability of Clostridium butyricum in biohydrogen production from non-sterile food waste. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy. 2017, 42, 3454-3465. [CrossRef]

- Dang D.X.; Zou Q.Q.; Xu Y.H.; Cui Y.; Li X.; Xiao Y.Y.; Wang T.L.; Li D.S. Feeding Broiler Chicks with Bacillus subtilis, Clostridium butyricum, and Enterococcus faecalis Mixture Improves Growth Performance and Regulates Cecal Microbiota. Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins. 2024, 16, 113-124. [CrossRef]

- Xue L.G.; Wang D.; Zhang F.Y.; Cai L.Y. Prophylactic Feeding of Clostridium butyricum and Saccharomyces cerevisiae Were Advantageous in Resisting the Adverse Effects of Heat Stress on Rumen Fermentation and Growth Performance in Goats. Animals. 2022, 12, 2455. [CrossRef]

- Gioia D.D.; Mazzola G.; Nikodinoska I.; Aloisio I.; Langerholc T.; Rossi M.; Raimondi S.; Melero B.; Rovira J. Lactic acid bacteria as protective cultures in fermented pork meat to prevent Clostridium spp Growth. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 2016, 235, 53-59. [CrossRef]

- Liu X.Y.; Liu W.J.; Sun L.; Li N.; Kwok L.Y.; Zhang H.P.; Zhang W.Y. Exopolysaccharide-Producing Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus Space Mutant Improves the Techno-Functional Characteristics of Fermented Cow and Goat Milks. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2023, 71, 10729-10741. [CrossRef]

- Shen H.C.; Cui C.F.; Wang Z.; Wang Y.Y.; Zhu L.; Chen W.B.; Liu Q.; Zhang Z.G.; Wang H.; Yang K. Poly (arylene ether ketone) with carboxyl groups ultrafiltration membrane for enhanced permeability and anti-fouling performance. Separation and Purification Technology. 2022, 281, 119885. [CrossRef]

- Wijayasinghe R.; Vasiljevic T.; Chandrapala J. Lactose behaviour in the presence of lactic acid and calcium. Journal of Dairy Research. 2016, 83, 395-401. [CrossRef]

- Zhao L.; Liao J.; Wang T.Y.; Zhao H.J. Enhancement of Nutritional Value and Sensory Characteristics of Quinoa Fermented Milk via Fermentation with Specific Lactic Acid Bacteria. Foods. 2025, 14, 1406. [CrossRef]

- Zong L.N.; Lu M.L.; Wang W.Q.; Wa Y.C.; Qu H.X.; Chen D.W.; Liu Y.; Qian Y.; Ji Q.Y.; Gu R.X. The Quality and Flavor Changes of Different Soymilk and Milk Mixtures Fermented Products during Storage. Fermentation. 2022, 8, 668. [CrossRef]

- Ren Y.M.; Li L. The influence of protease hydrolysis of lactic acid bacteria on the fermentation induced soybean protein gel: Protein molecule, peptides and amino acids, Food Research International. 2022, 156, 111284. [CrossRef]

- Du Q.W.; Li H.; Tu M.L.; Wu Z.; Zhang T.; Liu J.H.; Ding Y.T.; Zeng X.Q.; Pan D.D. Legume protein fermented by lactic acid bacteria: Specific enzymatic hydrolysis, protein composition, structure, and functional properties. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces. 2024, 238, 113929. [CrossRef]

- Bai R.R.; Yang X.Y.; Li L. Physicochemical and nutritional properties of whole soy milk yogurt: Dependence on the strain. Food Bioscience. 2025, 65, 106085. [CrossRef]

- Tarazanova M.; Huppertz T.; Kok J.; Bachmann H. Altering textural properties of fermented milk by using surface-engineered Lactococcus lactis. Microbial Biotechnology. 2018, 11, 770-780. [CrossRef]

- Liu P.F.; Ma S.Y.; Chen J.; Duan C.; Wang L.X.; Chen D.; Lv S.Y.; Li Y.Z.; Yan X.L. Fermented sheep milk supplemented with Lactobacillus rhamnosus NM-94: Enhancing fermented milk quality and enriching microbial community in mice. Journal of Dairy Science. 2025, 108, 5530-5542. [CrossRef]

- Khanal S.N.; Lucey J.A. Effect of fermentation temperature on the properties of exopolysaccharides and the acid gelation behavior for milk fermented by Streptococcus thermophilus strains DGCC7785 and St-143. Journal of Dairy Science. 2018, 101, 3799-3811. [CrossRef]

- Damin M.R.; Minowa E.; Alcantara M.R.; Oliveira M.N. Effect of cold storage on culture viability and some rheological properties of fermented milk prepared with yogurt and probiotic bacteria, Journal of Texture Studies. 2008, 39, 1-113. [CrossRef]

- Kumar V.; Amrutha R.; Ahire J.J.; Taneja N.K. Techno-Functional Assessment of Riboflavin-Enriched Yogurt-Based Fermented Milk Prepared by Supplementing Riboflavin-Producing Probiotic Strains of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum. Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins. 2024, 16, 152-162. [CrossRef]

- Xue P.B.; Yu Y.; Wang H.; Cao Y.L.; Shi B.; Wang Y.N. Oxidized sodium lignosulfonate: A biobased chrome-free tanning agent for sustainable eco-leather manufacture. Industrial Crops and Products. 2024, 208, 117916. [CrossRef]

- Hu L.X.; Xue Y.L.; Cui L.R.; Zhang D.; Feng L.L.; Zhang W.; Wang S.J. Detection of viable Lacticaseibacillus paracasei in fermented milk using propidium monoazide combined with quantitative loop-mediated isothermal amplification. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2021, 368, 20. [CrossRef]

- Akhoundian M.; Alizadeh T. Enzyme-free colorimetric sensor based on molecularly imprinted polymer and ninhydrin for methamphetamine detection, Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy. 2023, 285, 121866. [CrossRef]

- Hameed A.M.; Elkhtab E.; Mostafa M.S.; Refaey M.M.M.; Hassan M.A.A.; El-Naga M.Y.A.; Hegazy A.A.; . Rabie M.; Alrefaei A.F.; Alessa A.; simaree A.A.; l-Bahy S.M.; ljohani M.; adasah S.;Aly A.A. Amino Acids, Solubility, Bulk Density and Water Holding Capacity of Novel Freeze-Dried Cow’s Skimmed Milk Fermented with Potential Probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum Bu-Eg5 and Lactobacillus rhamnosus Bu-Eg6. rabian Journal of Chemistry. 2021, 14, 103291. [CrossRef]

- Fookao A.N.; Mbawala A.; Nganou N.D.; Nguimbou R.M.; Mouafo H.T. Improvement of the texture and dough stability of milk bread using bioemulsifiers/biosurfactants produced by lactobacilli isolated from an indigenous fermented milk (pendidam). LWT - Food Science and Technology. 2022, 163, 113609. [CrossRef]

- Bai Z.X.; Wang X.C.; Huang M.C.; Li J.J.; Sun S.W.; Zou X.L.; Xie L.; Wang X.; Xue P.B.; Feng Y.Y.; Huo P.Y.; Yue.Y.; Liu H. obust integration of “top-down” strategy and triple-structure design for nature-skin derived e-skin with superior elasticity and ascendency strain and vibration sensitivity, Nano Energy. 120, 2024, 109142. [CrossRef]

- Yang C.; Wang J.; Xie J.; Wu S.P.; Amirkhanian S.J.; Wang F.S.; Zhang L.; Hu J. Investigation on rheological properties of bitumen based on rheological parameters of maltenes, Road Materials and Pavement Design. 2022, 23, 942-957. [CrossRef]

- Eltigani S.A.; Taniguchi T.; Ishihara A.; Arima J.; Elgasim El.A.; Eltayeb M.M. Microbiome-mediated flavor development in Berbassa: a traditional fermented milk starter for Gergoush production, International Microbiology. 2025, 08. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).