1. Introduction

Healthcare supply chain systems have been facing unprecedented transformations and challenges. On one hand, the global demand for pharmaceuticals and medical services continues to grow rapidly, placing increasing pressure on resource allocation and supply efficiency [

1]. According to the IQVIA Institute (2024), global medicine usage rose by 14% over the past five years and is projected to grow another 12% by 2028, with China leading in both consumption volume and expenditure [

2]. On the other hand, population aging and the rising prevalence of chronic diseases have driven a long term and diversified demand for healthcare services. By 2040, individuals aged 60 and above are expected to account for 28% of China’s population [

3], with a sharp increase in patients requiring long term treatment for diabetes, cardiovascular conditions, and other chronic illnesses. These developments have accelerated the integration of digital healthcare services such as telemedicine, e-prescriptions, and online pharmaceutical distribution into existing healthcare systems [

4].

Meanwhile, emerging models such as Personalized medicine, smart healthcare, remote services, and precision medicine are reshaping patient centered service delivery. Healthcare supply chains are evolving beyond traditional drug logistics and inventory systems into collaborative networks that integrate hospitals, pharmaceutical manufacturers, digital platforms, and end users [

5]. Digital technologies including artificial intelligence, predictive analytics, smart inventory control, and multi-stakeholder collaboration platforms, are playing a pivotal role in enhancing responsiveness, operational efficiency, and patient satisfaction [

6,

7].

Moreover, the outbreak of COVID-19 revealed the structural vulnerabilities of traditional supply chains and underscored the critical importance of resilience in healthcare systems. The ability to sense disruptions, respond rapidly, and recover systematically has become a fundamental requirement for the sustainable performance of healthcare supply chains [

8,

9].

In recent years, a growing body of literature has systematically reviewed how digital technologies can enhance system resilience and operational efficiency within the healthcare supply chain. These studies consistently highlight that technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), blockchain, and big data analytics can improve data driven decision making, agile responsiveness, and resource allocation efficiency particularly in domains such as hospital operations, pharmaceutical distribution, and emergency medical supply management [

5,

8]. In parallel, other research streams have focused on the development of supply chain resilience capabilities, proposing full cycle frameworks encompassing sensing, response, recovery, and adaptation, while emphasizing the critical role of Industry 4.0 technologies in enhancing these dynamic processes [

10,

11,

12].

Although these studies have expanded the understanding of digital transformation in healthcare supply chains, the majority remain qualitative or case based, and there is a lack of integrative investigation into the system-level architecture of healthcare supply chains. More specifically, limited attention has been paid to the mechanisms through which digital intelligence resources are transformed into strategic decision making advantages via organizational capabilities [

13,

14].

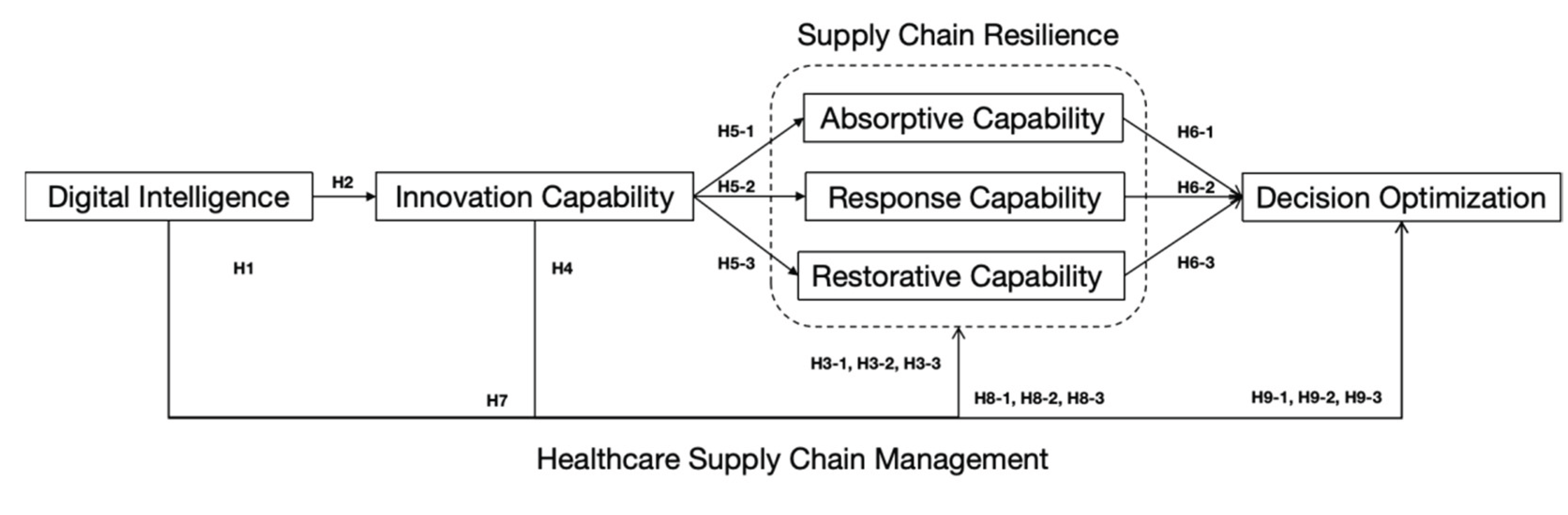

To address these gaps, this study develops a theoretical framework by integrating the Resource Based View (RBV) and the Dynamic Capabilities Theory (DCT). RBV emphasizes the strategic value of firm specific resources in achieving competitive advantage, with digital intelligence (DI) conceptualized as a high-potential strategic resource. DCT explains how firms absorb, reconfigure, and dynamically deploy such resources under environmental uncertainty to develop adaptive organizational capabilities, innovation capability (IC) and supply chain resilience (SCR). Building on this perspective, this study proposes that DI influences decision optimization (DO) in the healthcare supply chain indirectly and profoundly through the capability building pathways of IC and SCR.

In summary, to address the current lack of system level integration and the unclear mechanism pathways in the digital transformation of healthcare supply chains, this study aims to develop a theory driven analytical framework that systematically explores how digital intelligence enhances decision optimization through the mediating roles of innovation capability and supply chain resilience.

This research adopts an integrated perspective of the Resource Based View (RBV) and Dynamic Capabilities Theory (DCT) to uncover the mediating pathways through which digital resources are converted into strategic decision outcomes, thereby extending the theoretical foundation of digital transformation research in the context of healthcare supply chain management. On the other hand, the study provides empirical evidence and practical guidance for healthcare organizations to strengthen resilient operations and improve decision making efficiency under conditions of high uncertainty.

Unlike previous studies that primarily emphasized IT systems or digital tools, this study focuses on the technical characteristics of digital intelligence as a central feature of digital transformation. In light of the high demand volatility and complex service challenges in the healthcare industry, the research framework is constructed by integrating the Resource Based View (RBV) and Dynamic Capabilities Theory (DCT) to reflect the realities of highly dynamic environments. This study explores a parallel and sequential mediation mechanism composed of innovation capability and the three dimensions of supply chain resilience: absorptive, response, and restorative capabilities. It aims to reveal how digital technology resources can be transformed into decision optimization advantages through the collaborative functioning of organizational capabilities. By investigating how digital intelligence enhances organizational learning, innovation, and dynamic responsiveness, this study provides a new perspective on the deep level impact of digital transformation on healthcare supply chain management.

This study aims to explore the key drivers influencing decision optimization in the healthcare supply chain, with the goal of providing both theoretical support and practical guidance for the sustainable development of the healthcare industry. The structure of the study is as follows.

Section 2 provides a comprehensive review of the relevant literature on digital intelligence, innovation capability, and supply chain resilience including absorptive, response, and restorative capabilities, as well as decision optimization, and identifies the theoretical foundation and knowledge gaps addressed in this study.

Section 3 presents the conceptual model and research hypotheses, along with a detailed explanation of the research methodology, variable development, and measurement approach.

Section 4 reports the empirical findings based on structural equation modeling (SEM) and interprets the statistical significance of the results.

Section 5 discusses the research outcomes, highlights the theoretical and practical implications, outlines the study’s limitations, and proposes directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Digital Intelligence

With the continuous penetration of advanced digital technologies such as artificial intelligence, big data analytics, and the Internet of Things, digital transformation has become a critical force in reshaping core organizational capabilities and promoting high quality development [

15]. In the context of healthcare supply chains, digital transformation is regarded as a systemic innovation process driven by data, aiming to optimize resource allocation, enhance service effectiveness, and ensure medical quality [

16]. In this transformation, organizations urgently need to build intelligent systems capable of sensing, analyzing, learning, and forecasting to cope with highly uncertain external environments.

Among the various technological attributes encompassed by digital transformation, digital intelligence (DI) has increasingly drawn scholarly attention due to its deep impact on supply chain responsiveness and decision making capabilities [

17]. DI primarily relies on advanced technologies such as AI, machine learning, and big data analytics to restructure supply chain processes through intelligent sensing, intelligent analysis, and intelligent decision making. Empirical studies have shown that intelligent algorithms can significantly improve the efficiency of key supply chain functions, such as route optimization, demand forecasting, and inventory scheduling in healthcare systems [

18,

19]. In practice, the integration of AI with Vendor Managed Inventory (VMI) systems has enhanced information flow between hospitals and pharmaceutical firms, enabling automated replenishment and data visualization [

20], while AI-based platforms have improved order responsiveness and production planning accuracy in pharmaceutical enterprises [

21].

However, existing research largely treats digital intelligence as a technical tool, lacking structured modeling and theoretical interpretation of its role as an independent variable. In particular, studies exploring how DI influences strategic decision making through organizational capability pathways in the healthcare supply chain context remain scarce. To address this gap, this study conceptualizes DI as a key driving force that reflects a digital system’s capacity for autonomous cognition, intelligent analysis, and data driven decision making.

2.2. Innovation Capability

Innovation capability in healthcare supply chain management is widely recognized as a critical driver for organizations to gain competitive advantage in dynamic environments. It encompasses not only the adoption of emerging technologies, but also process optimization, service model restructuring, and rapid responsiveness to external changes [

22]. From various theoretical perspectives, innovation capability can be further specified as follows: From the perspective of technological resource integration, it reflects an organization’s ability to identify, absorb, and deploy advanced digital technologies such as artificial intelligence, blockchain, and IoT to support efficient coordination and service execution [

23]. From the perspective of process redesign, it involves continuous improvement of operational mechanisms, reduction of redundancies, and enhancement of system flexibility [

24]. From the service model restructuring lens, innovation capability enables the transformation of traditional linear supply models into patient centered, multi-point coordinated intelligent networks [

25].

Additionally, the synergistic accumulation of organizational learning, data driven capabilities, and cross functional integration is considered a core component of innovation capability [

26], while dynamic responsiveness to environmental disruptions also entails the reconfiguration of processes and strategic plans [

27]. Overall, innovation capability is not only essential for the deep application of digital technologies, but also serves as a driving force for platform based coordination, smart operations, and decision optimization in healthcare supply chains [

28].

However, existing research has not yet sufficiently examined how innovation capability functions as a dynamic organizational capability that mediates the relationship between digital intelligence and decision optimization via supply chain resilience. To address this gap, the present study incorporates innovation capability as a core mediating variable to explore its role in converting digital intelligence into strategic value, thereby extending theoretical insights into capability building and performance enhancement in healthcare supply chain management.

2.3. Supply Chain Resilience

In contemporary supply chain research, resilience is widely defined as an organization’s ability to maintain core functions and rapidly recover in the face of external disruptions [

29]. Zhao et al. (2023) further conceptualize resilience as a dynamic process encompassing absorptive, response, and restorative capabilities, highlighting the full cycle of sensing, reacting, and rebuilding in turbulent environments [

30]. Building on this, Senna et al. (2023) propose a systemic framework in which resilience in healthcare supply chains is not merely reactive, but represents a structured, multi-layered, and dynamic set of capabilities embedded within a cyclical mechanism linking antecedents, mediators, and outcomes [

10].

In the healthcare context, the ongoing disruptions caused by pandemics, large scale disasters, and population aging necessitate supply chains that are capable of rapid adaptation, diversified responses, and effective recovery [

31]. In response, recent studies have begun integrating Dynamic Capabilities Theory (DCT) into resilience research, emphasizing the relevance of sensing, seizing, and reconfiguring mechanisms in uncertain environments [

32].

Although some studies acknowledge the multi-stage nature of resilience, there remains a lack of in depth integration between resilience and DCT. To address this gap, the present study adopts a DCT informed approach and constructs a three dimensional structure of absorptive, response, and restorative capabilities as mediating variables, aiming to systematically assess how resilience bridges the relationship between digital intelligence and decision optimization in complex healthcare supply chains.

2.3.1. Absorptive Capability

Absorptive capability is commonly defined as an organization’s ability to sense, identify, and integrate external information, early warning signals, and potential disruptions in the pre-disruption phase [

33]. Zhao et al. (2023) identify absorptive capability as a critical starting point for resilient operations, enabling supply chains to detect disturbance sources and proactively consolidate relevant information resources at an early stage [

30]. In an empirical study of emerging economies, Tortorella et al. (2023) emphasize that, in the context of healthcare, absorptive capability also reflects the system’s sensitivity to heterogeneous and multi-source data, such as pandemic forecasts, fluctuations in patient demand, and policy shifts, which indicates its predictive and preemptive capacity [

34].

Wright et al. (2024) argue that establishing preemptive mechanisms for information perception and integration enhances the healthcare supply chain’s ability to anticipate crises and avoid delayed responses [

35]. In addition, Kumar et al. (2023) highlight that absorptive capability relies heavily on the support of AI, big data, and other digital technologies, which accelerate information sensing and improve data processing quality, thereby creating an intelligent link between information and decision making [

36].

Although its preemptive role in resilience management has been widely recognized, the conceptual boundaries, operational mechanisms, and quantitative measurement of absorptive capability in healthcare supply chains remain underdeveloped. Therefore, this study defines absorptive capability as the ability of an organization to integrate, recognize, and internalize heterogeneous information from multiple sources prior to disruptions. It emphasizes its core role in forecasting, early warning, and risk prevention, and conceptualizes it as the first stage dimension of supply chain resilience.

2.3.2. Absorptive Capability

Unlike absorptive capability, which emphasizes the identification and anticipation of risks before disruptions occur, response capability focuses on an organization’s ability to rapidly mobilize critical resources and make effective decisions during the occurrence of disruptions [

37]. This capability is reflected in how quickly identified risk signals are translated into concrete actions such as activating alternative routes, adjusting inventory strategies, and reallocating resources in a timely and efficient manner [

38].

In healthcare systems, the response window to disruptions is extremely narrow. In time sensitive areas such as vaccine distribution, emergency drug delivery, and surgical supply provision, response efficiency is directly linked to patient safety and continuity of care [

10]. Developing such capability requires not only refined internal process management but also support from digital technologies such as artificial intelligence and machine learning, which enable real time feedback, rapid scenario modeling, and intelligent path optimization [

36]. Tortorella et al. (2023), in their study of emerging economies, found that healthcare institutions with standardized, platform based, and modularized response systems are better equipped to translate disruption signals into swift operational actions [

34].

However, most existing studies treat resilience as a single aggregated construct, overlooking the phase specific nature and structured mechanisms of response capability within supply chain disruption scenarios. Therefore, this study conceptualizes response capability as the operational competence of healthcare organizations to respond immediately, mobilize resources, and implement strategic actions at the point of disruption. It is positioned as the second stage dimension of the supply chain resilience mechanism and is empirically examined in the proposed research model.

2.3.3. Restorative Capability

Restorative capability refers to an organization’s ability to effectively reorganize resources, rebuild disrupted processes, restructure operational systems, and even regenerate capabilities following a supply chain disruption, thereby enabling the system to return to its original or an even more optimal state [

39]. It represents the final and most decisive stage of supply chain resilience, determining whether the system can fully recover or even achieve post disruption performance improvement [

40].

From the perspective of dynamic capabilities, restorative capability is essentially the strategic integration and reconstruction of prior absorptive and response efforts. It reflects not only operational recovery but also the organization’s transformative capacity for structural renewal and capability realignment [

41]. Healthcare organizations with strong restorative capability can resume essential services, optimize critical nodes, and maximize operational efficiency even under resource constraints [

42]. In complex, multi-stakeholder healthcare supply chains operating in dynamic environments, restoration also requires cross system coordination of economic, environmental, and social resources to ensure a stable and efficient restart, which is vital for the long term sustainability of pharmaceutical and medical operations [

43].

However, in the context of healthcare supply chain management, how digital technologies can enhance organizational coordination and resource reconfiguration during the recovery stage remains an underexplored area. Therefore, this study further investigates restorative capability as a critical component of resilience and empirically examines its mediating role in the digital transformation decision optimization pathway.

2.4. Decision Optimization

Decision optimization in the healthcare supply chain has increasingly emerged as a central focus for ensuring operational efficiency, service safety, and long term sustainability [

44]. As a multidimensional process, decision optimization involves comprehensive coordination across various supply chain stages, including resource procurement, inventory allocation, and patient end service delivery [

45,

46].

With the accelerated integration of artificial intelligence into healthcare systems, decision optimization is evolving beyond static, rule based models. It now entails the dynamic configuration of decision paths and resource structures, based on multi-source data and advanced analytics. Emerging technologies, particularly large language models (LLMs), support semantic interpretation, trend forecasting, and complex judgment, thus improving the quality and agility of strategic decisions [

47,

48].

To explore the underlying mechanisms of decision optimization in healthcare supply chains, this study adopts the Resource Based View (RBV) as its theoretical foundation. RBV emphasizes that organizations gain sustainable advantage by developing and leveraging rare, inimitable, and embedded internal resources [

49]. In this context, digital capabilities, organizational agility, and process reconfiguration serve as essential enablers of intelligent decision systems.

However, existing research remains primarily focused on static reasoning, with limited exploration of how decision making structures operate in dynamic environments shaped by artificial intelligence, edge computing, and platform governance. Therefore, this study defines decision optimization as a context adaptive mechanism that combines technological intelligence, dynamic organizational capabilities, and resource reconfiguration to support strategic decision making. This conceptualization is further tested through empirical investigation.

5. Discussion

5.1. Conclusions

To deepen the understanding of how strategic decision optimization can be achieved in the context of digital intelligence driven transformation of healthcare supply chains, this study empirically tested the causal relationships among digital intelligence, innovation capability, supply chain resilience (absorptive, response, and restorative capabilities), and decision optimization using structural equation modeling.

First, the path analysis results indicate that digital intelligence does not exert a statistically significant direct effect on decision optimization in healthcare supply chains. This finding contrasts with those of Senapati et al. (2024) and Ivanov et al. (2019) [

49]. One plausible explanation is that digital technologies, when implemented as isolated tools without deep integration into management processes, may fail to directly enhance decision performance. As Tiwari et al. (2024) argue, digital infrastructure must be effectively aligned with network operations and process management to foster system autonomy and generate strategic advantages such as resilience, coordination, and efficiency [

89]. The results of the mediation analysis in this study further support this view. Digital intelligence was found to have a significant direct positive effect on both innovation capability and supply chain resilience, consistent with findings by Apell & Eriksson (2023) and Abourokbah et al. (2023) [

55,

56]. However, in contrast to Al-Surmi et al. (2022), this study reveals that innovation capability has a significant negative effect on decision optimization [

54]. A potential explanation lies in the fact that innovation in intelligent systems often entails high initial investment and operational complexity, which may hinder internal collaboration and decision efficiency in the short term [

52]. In addition, the study confirms that innovation capability positively influences all three dimensions of resilience absorptive, response, and restorative capabilities, which aligns with the findings of Mehmood et al. (2025) and Adana et al. (2024) [

66,

71]. Moreover, each of the three resilience dimensions was shown to significantly enhance decision optimization.

Second, the mediation analysis demonstrates that, in line with Junaid et al. (2023), supply chain resilience (absorptive, response, and restorative capabilities) fully mediates the relationship between digital intelligence and decision optimization. Furthermore, innovation capability and resilience capability, as two distinct but complementary organizational competencies, were found to jointly contribute to the sustainable improvement of decision making [

75]. Notably, however, innovation capability exhibits a significant negative full mediation effect between digital intelligence and decision optimization, which contradicts the findings of Jum’a et al. (2024) [

64]. This raises the possibility that a non-linear mechanism, such as a U shaped mediation or moderation effect, may exist in this relationship [

90]. In the early stages, low levels of innovation capability, characterized by underdeveloped platform integration and insufficient information sharing may disrupt supply chain coordination and diminish decision efficiency. However, as innovation capability matures and collaborative mechanisms improve, it may strengthen the adaptive responsiveness of the resilience system and enhance intelligent decision making support, ultimately leading to substantial improvements in decision performance [

91].

5.2. Theoretical Contribution

This study establishes a theoretical foundation for future research on digital intelligent transformation in healthcare supply chains, grounded in an integrated perspective of the Resource Based View (RBV) and Dynamic Capabilities Theory (DCT). It deepens the theoretical understanding of how digital intelligence influences supply chain decision optimization, contributing significantly to theoretical development within this domain.

Firstly, this research systematically integrates RBV and DCT within the context of digital intelligent transformation in healthcare supply chain management. Previous studies predominantly emphasized the technological dimension, lacking theoretical and empirical exploration of how resources translate into capabilities, and how capabilities support strategic decision making. Due to inherent complexities, demand uncertainty, and high risk characteristics, healthcare supply chains require a dual theoretical perspective involving strategic resource identification and dynamic capability construction. By integrating RBV and DCT, this study theoretically clarifies how healthcare organizations leverage digital intelligence as a strategic resource, transforming it through dynamic pathways involving innovation capability and supply chain resilience into strategic advantages for decision optimization.

Secondly, this research develops a novel structured path analysis framework by conducting a refined three dimensional structural decomposition (absorptive, response, and restorative capabilities) of healthcare supply chain resilience. Furthermore, it proposes a chain mediated mechanism between innovation capability and supply chain resilience. This mechanism specifies that digital technological resources, when encountering environmental disruptions and resource constraints, do not operate in isolation. Instead, they require the activation of internal organizational innovation mechanisms and dynamic responsiveness via resilience mechanisms to systematically enhance resource allocation efficiency, risk management, and strategic decision making capability. Consequently, this study provides a fresh theoretical perspective and solid foundation for future fine grained theoretical construction and multi-level research in supply chain management.

5.3. Practical Implications

This study provides forward looking and practical managerial implications for achieving the sustainable and healthy development of healthcare supply chains in the context of digital intelligence transformation.

Firstly, based on the specific results of the path analysis, healthcare supply chain organizations can proactively adopt Real Time Inventory Management systems, Robotic Process Automation (RPA), and intelligent scheduling systems to enhance decision making timeliness. These technological solutions are particularly suitable for managing critical scenarios such as emergency logistics, vaccine distribution, and high turnover inventory items [

92,

93]. In terms of improving system intelligence, healthcare organizations can integrate AI based predictive algorithms, machine learning driven decision support systems, pharmaceutical demand forecasting models, and intelligent replenishment models. These technologies are crucial for chronic medication management, personalized prescription services, and telemedicine drug delivery processes [

94].

Secondly, the identified mediation mechanisms also provide valuable managerial insights. Healthcare organizations should further enhance their process mechanisms by establishing multi-party collaborative platforms for early warning and response, facilitating real time data sharing and integration among hospitals, pharmaceutical companies, and logistics providers. For example, integrating hospital information systems (HIS), pharmaceutical enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems, and logistics transportation management systems (TMS) through standardized application programming interfaces (APIs) can enable real time data collection and dynamic analysis [

95,

96]. Meanwhile, healthcare organizations should establish contingency plans for redundant pharmaceutical resources, proactively engage alternative suppliers, third party logistics providers, and emergency inventory storage facilities, and create effective resource sharing and mobilization mechanisms [

97]. These measures can significantly enhance the continuity and efficiency of healthcare supply chain decision making and service provision.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Despite offering valuable theoretical and practical insights into the digital transformation and continuous optimization of healthcare supply chains, this study is subject to several limitations that warrant further exploration.

First, the empirical analysis is based on cross sectional data. Given the progressive and phased nature of digital transformation, future research could benefit from longitudinal or panel data to more systematically examine how the development of digital capabilities influences the long term stability and sustainability of decision making performance.

Second, the data collected in this study are primarily drawn from healthcare supply chain organizations in mainland China. While representative to a certain extent, the findings may be limited by region specific institutional settings, healthcare system structures, and technological adoption environments. Thus, future studies should extend the research scope to other countries or regions, particularly those with different regulatory frameworks or levels of digital infrastructure in order to enable cross country comparisons and enhance the external validity and global relevance of the results.

Lastly, as emerging technologies such as generative artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things, and biometric systems become increasingly integrated into the healthcare sector, the scope of digital transformation continues to expand. Future research could incorporate these developments to re-examine their impact on supply chain resilience, organizational innovation behavior, and complex decision making processes, thereby providing more forward looking theoretical frameworks and strategic recommendations.