1. Introduction

In response to economic globalization and increasing rivalry, enterprises are compelled to improve their logistical capabilities to enhance a competitive edge. According to research, Logistics capabilities are more important to a company’s success when competing on a worldwide scale. It has long been acknowledged that logistics affects a company’s bottom line; Drucker (2012) saw logistics as a significant area for organizations to enhance their efficiency, considering it to be one of the last frontiers of potential. The author recognizes that customer value development may be achieved by prioritizing logistics customer service. In a highly competitive environment where speed and quality are key factors, the need of logistical capabilities becomes even more crucial. Moreover, several companies that operate in commodity or convenience products marketplaces achieve success because of their efficient logistics system (Mentzer, Stank, and Esper 2008). Logistics capabilities enhance a company’s competitiveness by generating economic value via cost leadership and efficiency, as well as market-based value through distinctiveness and effectiveness (Wen 2012;Mentzer, Min, and Michelle Bobbitt 2004).

While there have been numerous advantages attributed to the establishment of logistics capabilities that are unique to a firm (Sandberg and Abrahamsson 2011;Esper, Fugate, and Davis-Sramek 2007;Yang 2012). Supply chain engage in competition with one another (Lambert and Cooper 2000;Christopher 2000). Consequently, to achieve a competitive edge, companies must cultivate comprehensive logistical capabilities that span across all participants in the SC (David M. Gligor and Holcomb 2012). To achieve success, organisations must possess outstanding logistical capabilities inside their own organisation and successfully integrate these capabilities with those of their suppliers. This concept is backed by the generally acknowledged belief that the integration of business processes is an essential need for effective SC management (Stenger 2011; Mentzer, Stank, and Esper 2008).

Logistics is crucial in complex supply chains and having a logistics plan is vital for a company to gain a competitive edge. Logistics activities are essential components of SC operations. Logistics refers to the transportation of physical objects and is a clear representation of supply chain structures. It also forms the basis for future generations of transactions, financial activities, and information exchange. In addition, logistics services play an essential part in ease the risks and vulnerabilities of the SC. Firms’ logistics operations include many capacities that connect with supply, demand and information processes.

Logistics managers are progressively facing the pressure to enhance operational efficiency in business settings characterized by swiftly evolving customer demands in current years. Firms are under pressure to be flexible in their operations, so they can handle changes in demand, manage a variety of products, and deal with the short life of products efficiently. Using advanced technology can help logistics managers handle the complexities of logistics operations more effectively. The connection between IT technologies and new opportunities is strongly tied to how flexible the logistics and SC can be (Lagorio et al. 2022). In the same way that technology facilitates physical operations, it also supports to take appropriate decisions and exchange information’s (M. C. Cooper, D. M. Lambert, and J. D. Pagh. 1997). The fields of SC management and logistics have historically been at the forefront of technological advancement in manufacturing. Many new technologies have their origins in the logistics and SC management industries. For example, the initial trials of autonomous cars in warehouses were conducted in these sectors (Lu 2017). Several of these technologies have achieved a notable degree of maturity and are now extensively deployed, including radio-frequency identification (RFID) (A.S and Ramanathan 2021). However, advanced technologies like big data analytics (BDA) are becoming essential and are being used more and more in the logistics industry (Dennehy et al. 2021).

Logistics and SC management face big challenges that can cause inefficiencies and waste. These problems include unreliable suppliers, late shipments, ever-increasing customer demands and rising fuel costs (M. Wang et al. 2020). Organizations hope that using big data analytics capabilities in SC and logistics operations will improve SC capabilities and SC integration in all over the world. They believe it will help manage demand changes and control costs more effectively (Bahrami and Shokouhyar 2022). Big data analytics is essential in the strategic planning of SC. It helps companies make important decisions about sourcing, designing the supply chain network, and developing products. During the operational planning phase, managers use big data analytics for decision making purpose, such as planning related to demand and supply, procurement process, manufacturing, and logistics & inventory management. (G. Wang et al. 2016).

Big data analytics used for prediction and preventive of risk. It creates new resources that give strategic benefits and long-term stability to the SC. Using big data analytics on large data sets can help make better decisions by identifying important opportunities and challenges in SC management (Raut et al. 2021). The utilisation big data analytics has the ability to drive significant expansion and progress in critical industries, including forecasting market demand, product development, optimisation of distribution, decision provision, and client feedback (Bag et al. 2023).

Undoubtedly, big data analytics is a pioneering force in research (Mageto 2021). SC management faces complex challenges that can lead to inefficiency and waste. These challenges include delays in supply, increasing fuel costs, higher consumer demands, and unreliable suppliers (Gupta et al. 2022). Big data analytics in SC management has become very important for both professionals and researchers. It helps improve how companies perform in managing their supply chains. Big data analytics involves the examination of vast quantities of data to uncover hidden patterns and correlations (Kondraganti, Narayanamurthy, and Sharifi 2022). Using advanced technologies for data analysis can quickly provide solutions. It helps organizations make faster and more effective decisions. Big data analytics also measures customer needs and satisfaction, making it easier to offer desired products or services.

The study’s main idea is that big data analytics capabilities have the potential to integrate logistics capabilities at the supply chain level and enhance their performance. Logistics capabilities, which include demand, supply, and information interface capabilities, further enhance the resilience and performance of the supply chain. Big data analytics capabilities include both management and personal capabilities. Big data analytics management capabilities include planning and coordination, which are critical for integrating logistics capabilities at the supply chain level. Coordination capabilities enhance cooperation between supply chain partners that can manage supply and demand efficiently and effectively. Coordination capabilities act to enhance information sharing related to tactics and operations. On the other hand, planning is another crucial aspect of integrated logistics capability at the supply chain level. Execution of the planning between the supply chain partners in the right way can enhance the performance of logistics capabilities, which can manage supply and demand efficiently. Furthermore, big data analytics personal capabilities, including rational and technical knowledge, are also crucial for the integration of logistics capabilities at the supply chain level. Establishing knowledge-sharing routines can facilitate the exchange of information between supply chain partners during supply chain operations, which helps integrate logistics capabilities at the supply chain level. The supply chain members’ awareness of technical and rational knowledge can improve the efficiency of supply chain and logistics operations. Moreover, big data analytics capabilities facilitate integrated logistics capabilities, thereby enhancing supply chain resilience and performance. Big data analytics capabilities have a positive influence on improving firm performance through supply chain resilience. The firm leverages SC resilience to derive value from big data analytics capabilities. Our research will confirm that transforming big data analytics capabilities into other firm capabilities, such as logistics capabilities, can enhance SC resilience and firm performance.

Various governments worldwide have allocated resources towards the use of digital technology to strengthen their ability to withstand and recover from challenges. China is a major developing country where a significant portion of the manufacturing industry utilizes digital technologies to manage logistics and supply chain operations. In this study, we surveyed 254 Chinese firms. For example, the Chinese government has earmarked RMB1.4 trillion for the construction of 5G networks, smart cities, and smart manufacturing. The objective is to construct fifth-generation towers that will enhance manufacturing resilience on the mainland China (Choi et al. 2022).

The Main Contributions of the Study Are Three Folded

- (1)

Our research offers a comprehensive perspective and originality on how logistics capabilities (such as supply, demand, and information management interface capabilities) can be integrated at the supply chain level using big data analytics capabilities. This includes the utilisation of management and personal capabilities in supply chain and logistics operations.

- (2)

Furthermore, our research highlights the significant influence of big data analytics capabilities on integrated logistics capabilities, resulting in improved customer service and logistics quality that meet customer expectations by providing value-added services. Moreover, managing supply management interface capabilities through big data analytics capabilities can minimise operational costs and run the logistics process efficiently. Finally, through the implementation of big data analytics capabilities, our research focuses on managing the flow of tactical and strategic information both inside and outside of the firm.

- (3)

In previous literature, researchers found the impact of big data analytics capabilities and integrated logistics capabilities on SC resilience and performance separately. In our research, we identify how the interplay between big data analytics capabilities and logistics capabilities is helpful to enhance SC resilience and performance.

We suggest two research questions for this study based on the previous discussion.

Q1. How do big data analytics capabilities help to enhance integrated logistics capabilities?

Q2. How this interplay helpful to enhance supply chain resilience and performance?

The reminder of this paper s organized as follows

Section 2 examines relevant literature on BDA capabilities integrated logistics capabilities and supply chain resilience and performance.

Section 3 provides a further explanation of the study methodology.

Section 4 presents the analysis of the results.

Section 5 then discusses the results, while the conclusion section, No. 6, presents the theoretical and managerial implications. The same section also discusses limitations and future recommendations.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

We used a quantitative approach to examine the potential causal link between the big data analytics capabilities including management capabilities (planning and coordination) on integrated logistics capabilities. Similarly, we will explore how big data analytics capabilities including personal capabilities (technical knowledge and rational knowledge) impact on integrated logistics capabilities. Furthermore, we will analyse how integrated logistics capabilities affect SC resilience, and in turn, how SC resilience (SCR) influences SC performance. In this section we will explain the theoretical relationship between the variables and develop hypotheses.

2.1. Integrated Logistics Capabilities

Logistics is the organized management of moving and storing products, services, and information from where they are made to where they are needed, all to meet customer needs (Christopher and Holweg 2011). From a business perspective, logistics focuses on coordinating and controlling the flow of goods through tasks like storage, packaging, transportation, delivery processing, managing information, and distribution. The discussion has been about working together across departments to deliver great services efficiently and cost-effectively (Mentzer, Stank, and Esper 2008). In business, logistics uses specific strategies to stay competitive by adjusting to changes in the market and satisfying customer demands (David M. Gligor and Holcomb 2012). An integrated logistics capabilities, characterized by a dedication to both internal and external coordination, plays an critic role in influencing operational performance and enhancing SC competitiveness (Brekalo, Albers, and Delfmann 2012). Key aspects of logistics capabilities include combining logistics resources, working together on logistics from suppliers to customers, and managing integrated logistics information (Bag et al. 2020).

“Logistics capabilities are those specialized skills, attributes and knowledge within a firm that helps a firm to manage its logistics activities (e.g., transportation and distribution of raw materials and finished goods) efficiently and effectively” (Mentzer, Min, and Michelle Bobbitt 2004). E. a. Morash, Droge, and Vickery (1996) refers that Logistics capabilities encompass the characteristics, capacities, procedures, expertise, and proficiencies that enable a company to attain exceptional performance and sustain an edge of competition over rivals. Fawcett, Smith, and Bixby Cooper (1997) explain that Logistics operations are special abilities and procedure within an organization that can be developed into a unique strength. In 1995, a team of Global Logistics Researcher Michigan State University conducted qualitative and quantitative reviews to identify logistics capabilities. The aforementioned capabilities were subsequently categorize into four distinct abilities: measurement, integration, agility, and positioning. E. a. Morash, Droge, and Vickery (1996) were assessed based on two main “value disciplines”: intimacy and operational excellence. The first value discipline focuses on the customer’s external aspects, such as interfaces, goals, and needs. This approach is customer-oriented and emphasizes demand. The logistical capabilities encompass responsiveness, post-sale customer service, delivery speed and presale customer service. The next discipline, operations-oriented, focuses on the organization’s internal operational capabilities.

The second value discipline includes three supply-oriented capabilities: selection-based distribution coverage, cover distribution broadly and cost reduction distribution. The system incorporated three logistics capabilities: web-based order administration, delivery information transmission, and delivery dependability. In their study on firm theories, Mentzer, Min, and Michelle Bobbitt (2004) examines the logistics capabilities and classifies them into four primary categories: demand, supply, information, and coordination management interface capabilities. Demand-management interface capabilities are primary focus on aspects pertaining customer and quality of logistics. Conversely, the supply-management interface capabilities handle cost-effective SC and efficient distribution. Additionally, the information-management capabilities aim to provide real-time information among SC members. Lastly, the coordination capabilities improve the internal and external coordination of SC members. Logistics’ demand-management capabilities, such as customer focused and logistics quality, differentiate products or services and enhance customer satisfaction for lasting competitive advantage E. A. Morash, Dröge, and Vickery (1997). These capabilities are also known as valued-added, customer integration capabilities or customer-focused Zhao, Dröge, and Stank (2001), Lynch, Keller, and Ozment (2000), Donald J. Bowersox, David J. Closs, and Theodore P. Stank (2000). These competencies enable a corporation to focus on particular consumer segments and exceed their expectations by providing distinctive value-added services Lynch, Keller, and Ozment (2000). Supply-management interface capabilities involve minimizing total costs and optimizing logistics processes efficiently E. a. Morash, Droge, and Vickery (1996). Supply-management capabilities also means to the ability of an organization to proactively and creatively solve logistics issues in specific situations or emergencies and meet customer needs effectively. Additionally, it involves streamlining and standardizing key logistics activities across different supply chain processes. Logistics perform a vital role to managing both the flow of materials (upstream) and the distribution of goods (downstream), along with related services and information. Therefore, logistics possesses information management capabilities that involve acquiring, analysing, storing, and distributing tactical and strategic information across the supply chain, both internally and externally Zhao, Dröge, and Stank (2001). Information management capabilities involve using IT, including computer networks, hardware, system design and software.

2.2. Big Data Analytics Capabilities (BDA Capabilities)

Big data analytics is a high volume of data, both organized and unorganized, generated regularly through business activities and services (Sundarakani, Ajaykumar, and Gunasekaran 2021). Due to devices and the IoT, more data is being generated from various sources. These include sensors in machines (like those in factories, power turbines, and tractors), mobile devices (such as Fitbit), platforms of social media (like Facebook and Twitter), shopping through online sites (such as Amazon and eBay), streaming services (like Hulu, Netflix, and Spotify), enterprise software systems, GPS, and RFID (Govindan et al. 2018). Big data analytics includes high volume of data that a company gathers daily and can’t handle using traditional methods for storage or analysis (Manikas, Sundarakani, and Shehabeldin 2023). Big data analytics isn’t just about the size of files. Companies also need to consider factors like the different types of data and how quickly the data are generated (velocity) (Gärtner and Hiebl 2019). According to Hofmann and Rüsch (2017) Big data analytics refers to data collections that include the following characteristics: (1) Large quantity (2) Diverse range from many origins and in various formats (Variety) (3) Rapid generation, duplication, and distribution (Velocity). Examples of big data kinds include video, picture, text, and audio, which might be in an organized, unorganized, or semi-organized format (Abaker et al. 2014). Organized data follows set data formats and models, while unorganized data does not follow any specific data models (Assunção et al. 2015). By acquiring and analysing big data, businesses can generate strategic and intelligent insights that boost their value. Machines are increasingly supplying decision makers with a greater amount of information, and Analytics is emerging as the next tool for optimization. To construct a smart factory, organizations must develop a process that is guided by analytics, enabling them to make real-time decisions about their whole business process value chain (Dalmarco et al. 2019).

Big data analytics traditionally been associated with the capacity to handle large volumes of data that cannot be handled using old data acquisition methods. In the years of seventy and eighty, prior to the advent of the Internet, data measured in gigabytes was regarded as huge data. Currently, the term “big data” is used to describe data that is measured in petabytes and even in exabytes. This development may be ascribed to the expansion of data sources and the improved ability to analyse the growing volume of data. Modern supply chains include worldwide partners that generate and exchange substantial volumes of data using technologies such as Radio Frequency Identifiers (RFIDs), sensors, emails, and text messages (M. Wang et al. 2020). The data processing capacity has seen substantial changes throughout the years. Prior to this, basic forecasting software and spreadsheets were used. The growing demand for big data analytics has driven the popularity of cloud computing technologies, making big data a valuable asset (Addo-Tenkorang and Helo 2016). Companies using data-driven business strategies gather crucial information from their business interactions. To optimize methods effectively, analysing data in real-time predict smoothly. This includes collecting and sorting data from various sources swiftly and efficiently (Sanders 2016).

Big Data Analytics involves discovering important trends and patterns in data. It uses statistical techniques, programming, and research, often with data visualization to display findings. There are four ’V’s that must be considered when analysing big datasets: volume (the quantity of data), velocity (the rate of data development), variety (the kinds of data present), and veracity (the precision and dependability of the data) (Li and Liu 2019). Ji-fan Ren et al. (2017) There are three main parts to the Big Data Analytics capabilities: BDA infrastructure, BDA personal, and BDA management capabilities. All the parts work together to produce the necessary frameworks, so it’s easy to measure these capabilities and how they affect key performance metrics like financial results and the capacity to run dynamic processes. According to Govindan et al. (2018) there are more advantages in using big data analytics techniques in SC Management. Minimize inefficiencies in food supply chains, decrease environmental impact by using cloud computing, address the issue of exaggerated fluctuations in demand, accurately predict and control demand, and effectively strategize for the future (Sundarakani, Ajaykumar, and Gunasekaran 2021). The research findings show a positive link between supply chain partner coordination, adaptability to market demand changes, and overall organizational performance and decision-making abilities.

2.3. Supply Chain Resilience

The concept of resilience has been extensively examined in the context of supply chains. To enhance comprehension of resilience in this area, (Ponomarov and Holcomb 2009) undertook a comprehensive analysis of existing literature from many disciplines, providing a unified viewpoint on resilience. They described supply chain resiliency as:

“The adaptive capability of the SC to prepare for unexpected events, respond to disruptions, and recover from them by maintaining continuity of operations at the desired level of connectedness and control over structure and function”

The study argued that support from senior management and the adoption of risk-sharing protocols will significantly impact the various stages of the proposed conceptual framework. (Pettit, Fiksel, and Croxton 2010) defined resilience as a state characterized by a balance between vulnerabilities and capabilities. In their conceptual framework, (Ponomarov and Holcomb 2009) suggested that integrating specific logistics capabilities such as demand management, supply management, and information management can enhance supply chain resilience and ultimately contribute to achieving a sustainable competitive advantage. (Jüttner and Maklan 2011) discovered that implementing risk management and risk knowledge management positively influenced a supply chain’s ability to adapt to and recover from disruptions. This enhancement was accomplished by improving the supply chain’s flexibility, visibility, speed, and cooperation, which are known as formative resilience capabilities. Additionally, a study by (Wieland and Wallenburg 2013) revealed that effective communication, cooperation, and integration positively influenced the enhancement of resilience. (Carvalho, Duarte, and Machado 2011) asserted that an organization’s adoption of agile and resilient strategies significantly impacts its supply chain performance, ultimately determining its market competitiveness. This assertion is backed by specific anecdotal evidence. Furthermore, (Al-Talib et al. 2020) conducted an in-depth qualitative case study to explore the empirical relationship between supply chain capabilities that enhance resilience and disaster management practices.

2.3.1. BDA Personal Capabilities and Integrated Logistics Capabilities

Ji-fan Ren et al. (2017) define BDA personal capabilities that pertains to the skills and expertise of the analytics team in performing their assigned tasks. This includes technical knowledge, technical management skills, understanding of business operations, and ability to build effective relationships. These capabilities consist of several elements: technical expertise, skills in technical management, understanding of business operations, and ability to build effective relationships. Technical knowledge includes the big data analytics team’s proficiency in operate system efficiently, managing databases, programming languages, and other essential skills required to maintain system functionality (Manikas, Sundarakani, and Shehabeldin 2023). Relational knowledge pertains to the team’s capacity to successfully communicate and work effectively with other organizational functions (Manikas, Sundarakani, and Shehabeldin 2023). Hence, it is evident that the big data analytics team’s technical expertise and their proficiency in conveying vital information about system operation may significantly influence a company’s ability to managing demand and supply interfaces capabilities, as well as information management capabilities. The consensus among experts is that the implementation big data analytics will be advantageous for firms, as it will enhance their capacity to handle information and decrease the amount of uncertainty about supply and demand in their worldwide business networks (Galati and Bigliardi 2019).

Demand management interface capabilities include customer based and logistics quality. Customer service capability involves flexibility to handle unforeseen conditions and accommodate unusual or unexpected customer demands, ensuring satisfaction by meeting evolving customer expectations and needs (Christopher and Lee 2004). Logistics quality is essential to customer service and refers to the ability to distribute items or resources according to customer expectations and standards. The concept includes four elements: timeliness, availability, delivery quality, and effective connection with consumers (Mentzer, Flint, and Hult 2001). BDA capabilities have an ability to improve flexibility, reliability and resources optimization which has directly influence logistics capabilities at SC level (Osmólski, Koliński, and Kilic 2020). Raj et al. (2020) Determine the most significant obstacles to the use of big data analytics that SME, s businesses encounter in both developed and developing nations. SME, s faced technical and personal challenges to implement BDA applications in their SC and logistics operations. They have less knowledge about digital technologies applications, inadequate awareness and training, an absence of comprehension regarding the technical importance of digital transformation, pronounced focus on firm development cost. The lack of knowledge regarding BDA capabilities could have a ssignificant impact on overall business progress and SC management. Based on the discussion above, the author suggests that exploring big data analytics capabilities should focus on their potential to enhance integrated logistics capabilities within the SC. Additionally, the author emphasizes that personnel capability is crucial in big data analytics capabilities. Therefore, its direct effect on integrated logistics capabilities should also be investigated. Consequently, the hypotheses are proposed as follows.

H1. BDA technical knowledge has significantly positive impact on integrated logistics capabilities.

H2. BDA rational knowledge has significantly positive impact on integrated logistics capabilities.

2.3.2. BDA Management Capability and Integrated Logistics Capabilities

BDA management capabilities have the capacity to effectively handle company operations in a systematic way. This competence is comprised of many components, including planning, coordination, control, and investment. Coordination and planning are essential for achieving integration. With the right planning, you can gather, analyze, and interpret data appropriately. Coordination involves aligning actions among involved parties. Therefore, this article posits that these elements of BDA management capabilities are essential for achieving integrated logistics capabilities. Effective coordination requires firms to exchange information about strategies and operations. A substantial competitive advantage may be gained by developing protocols for knowledge sharing, which simplify the interchange of information. Coordination may also help in recognizing possible synergies among partners. A well-known strategy for standing out and gaining an edge in the market is for supply chain members to use each other’s complimentary resources Stanley, Gregory, and Matthew (2008). Furthermore, studies on supply chain management indicate that the capacity to coordinate both within the organization and with external partners improves the integration of processes within the SC. Information sharing in real-time facilitates coordination and operational synchronization among organizations within the SC (Mandal 2019). Big data analytics clearly has the potential to impact integrated logistics capabilities through planning and aiding coordination. This is because supply chain management would be incomplete without logistics management Mentzer, Stank, and Esper (2008). The statement implies that effective management of logistical capabilities across the supply chain requires coordination and planning. So that we proposed following hypotheses.

H3. BDA planning capability has significantly positive effect on integrated logistics capabilities

H4. BDA coordination capability has significantly positive effect on integrated logistics capabilities

2.3.3. Integration of Logistics Capabilities and SCR

The purpose of integrated logistics capabilities is to combine the logistical expertise of a main organization with those of its supply chain partners. David M. Gligor and Holcomb (2012) argued that when logistical capabilities are interconnected in this manner, they can improve SC agility. This is associated with how well the SC can respond to consumer needs. Given the importance of SC agility which is like SC resilience, we argue that integrating logistical capabilities at the SC level is necessary to improve SC resilience. Thus, we assert that integrated logistics capabilities have a significantly positive influence on the enhancement of SC resilience. Therefore, our subsequent hypotheses are as follows.

H5. Integrated logistics capabilities have significantly positive effect on supply chain resilience.

2.3.4. SC Resilience and SC Performance

SC performance pertains to the efficacy and productivity of several operational procedures inside the SC. Christopher and Lee (2004) highlighted Resilience having a capacity of a SC to improve its performance in the presence of a disturbance. SC resilience is a dynamic quality that allows firms to efficiently handle external interruptions and maintain optimum performance. Therefore, supply chain resilience (SCR) acts as a changeable ability that provide favourable performance results. Thus, we propose that:

H6. SC resilience has significantly positive impact on SC performance

2.3.5. Conceptual Framework

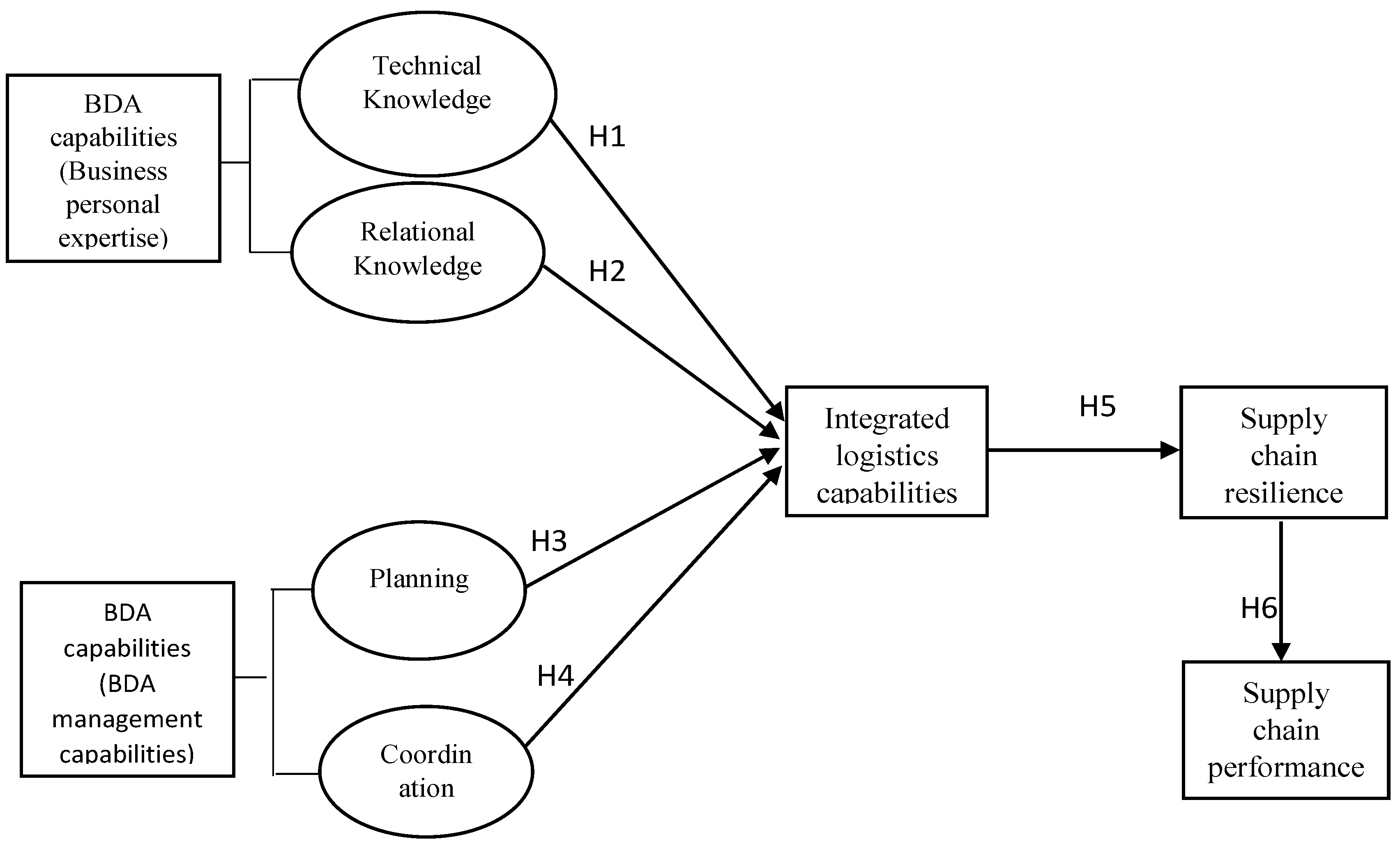

Drawing from the literature, we formulated six primary hypotheses regarding the relationships among BDA capabilities, integrated logistics capabilities, SC resilience, and SC performance.

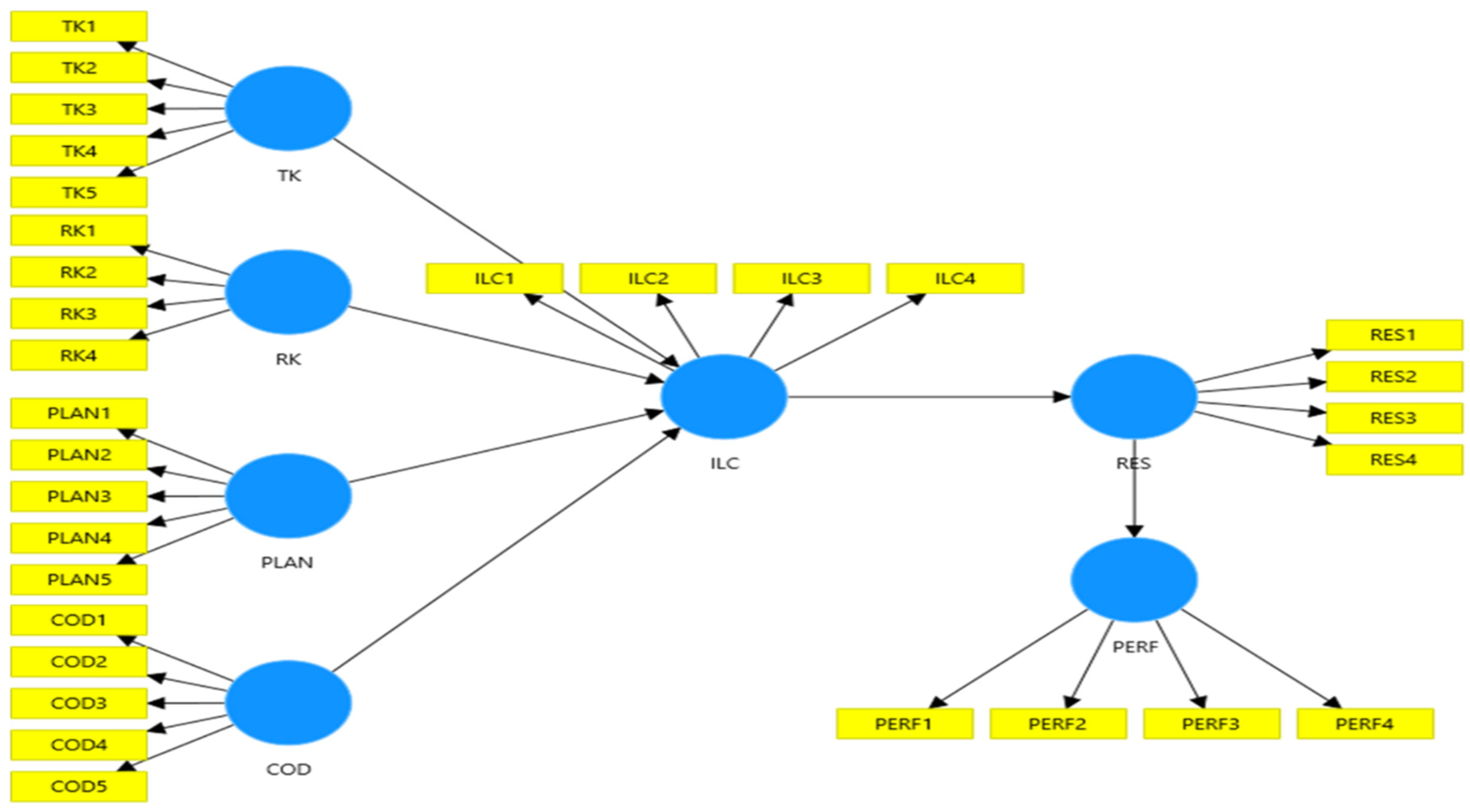

Figure 1 shows the proposed model graphically. Our model encompasses a total of seven variables, with four being independent and three dependent. Ji-fan Ren et al. (2017) defined the big data analytics has four personnel capabilities and four management capabilities as first-order capabilities in their initial proposition. Nevertheless, for representation, the two elements that exemplified their respective categories the most were chosen (

Figure 2). Similarly, Mentzer, Min, and Michelle Bobbitt (2004) David M. Gligor and Holcomb (2012) identified integrated logistics capabilities as consisting of demand, supply, information and coordination management interface capabilities. Furthermore, we implemented Mandal et al. (2017) proposed concepts of SC resilience and SC performance. To that end, this research aims to supply a through comprehension of how BDA capabilities enhance and integrate logistics capabilities at SC level, how the integration of logistics capabilities impacts SC resilience, and how to improve SC performance.

3. Methodology

3.1. Materials and Methods Selection

In our study we utilize the quantitative technique to assess the relationship between BDA capabilities including management, personal capabilities and integrated logistics capabilities. Furthermore, we assess the impact of integrated logistics capabilities on supply chain resilience and performance. We used Smart PLS V 4.0 as statically reliable software for analysis. Smart PLS is a tool that researchers may use to evaluate the predicting accuracy of the exogenous variables. Scholars contend that Partial Least Squares (PLS) is more appropriate for elucidating intricate connections due to its ability to overcome two significant issues: inadmissible solutions and factor indeterminacy. Our study emphases on analysing the predictive influence of BDA capabilities on integration of logistical capabilities. The present literature has not yet examined the relationship between BDA capabilities and integrated logistics capabilities, and how they contribute to the improvement of SC resilience and SC performance. There is currently no theoretical or practical basis that investigates the connection between these variables. We conducted our analysis following the methodology outlined Joseph F. Hair et al. (2019), focusing on assessing the convergent and discriminant validity of the model before testing hypotheses.

3.2. Construct and Their Measurements

All survey variables’ questions were derived from previously published research to guarantee the validity and reliability of the data collected. The independent variables were constructed by selecting multi-scale items from the study conducted by (Ji-fan Ren et al. 2017). Similarly, to construct the integrated logistics capabilities, multi scale items were chosen from (David Marius Gligor and Holcomb 2014). Furthermore, constructs for supply chain resilience (SCR) and SC performance selected from (Mandal et al. 2017). Using a 5-point Likert scale, participants express their subjective opinions on each issue, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Codes are used to conveniently label the measured variables. You may find the detailed information on each measurement item, including the questionnaire items and their associated codes, in Appendix 2. There is a total of 31 constructs, (all of which are displayed in the Appendix).

The variable headings in the file are coded as follows: integrated logistics capabilities (ILC), supply chain resilience (RES), Relational knowledge (RK), Technical knowledge (TK), coordination (COD), planning (PLAN), and SC performance (PERF). The measurement items were coded in chorological order. For example, ILC-1 denoted the first question related to integrated logistics capabilities, while PERF-3 marked the third question evaluating supply chain performance, and so on

Survey and Demographic Validity

The survey for this study is segmented into three main parts: an overview of the variables, specifying the study’s objective, and explaining the problem statement. The initial component collects demographic data from participants, encompassing gender, position, years of professional experience, firm classification, income range, and age. The 2nd part focuses on measurement items, while the 3rd section addresses hypothesis testing and results. The question types were clearly aligned with the concepts being assessed. The choice of scale for the evaluated concepts and the data they presented were suitable in terms of face validity. Additionally, the literature, as previously mentioned, supports the options presented for the variable items. Thus, we verified that the questions accurately represented the constructs they were intended to measure. The questions comprehensively addressed a wide range of ideas, as evidenced by the questions themselves and confirmed by the research results utilizing the constructs.

3.3. Data Collecting

We administer a survey by hand to gather data. First, we fixed the research question based on previous literature to ensure reliability and validity. Subsequently, we proceed to translate the initial English text into Chinese, ensuring that we make appropriate modifications to the phrase to conform to the semantics of the Chinese language. Next, we render it back into English for the sake of comparison, to verify that the translation is conceptually same. Ultimately, to guarantee the clarity and comfort of the questionnaire, we go to different regions of the Chinese mainland and reach out to possible respondents. After a period of one month, we remit them through their WECHAT as a means of encouraging participants to finish the survey. We guarantee anonymity and confidentiality for this questionnaire, guaranteeing the exclusive use of collected data for academic research purposes. We use phone numbers and WECHAT to identify respondents, and we enforce the restriction that each respondent may only provide answers to the questionnaire once. We ultimately returned 310 out of the 650 distributed questionnaires, indicating a response rate of 47.6%. To ensure the questionnaire’s quality, we eliminated 56 questionnaires with invalid responses. These responses were considered invalid because they consisted of either identical or slash-patterned replies for more than two-thirds of the total questions in the questionnaire. Therefore, the total acceptable questionnaires are 254. Most participants in our study are from businesses situated in four highly established industrial zones in China: the Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen, Qingdao and Hangzhou. Most respondents are company heads from manufacturing-related fields, such as chemicals, electronics, machinery, automobiles, and internet technology. We sort the information according to the respondents’ jobs, the number of years they’ve been with their present companies, the size of the business, the amount of money it makes, and the age of the company (how long it’s been in business) in the (

Table 1). The clear majority of those who took the survey had been with their current employers for more than three years, and they are all in managerial or supervisory roles. Hence, the respondents have enough expertise to complete our survey, given their managerial positions and long-term employment. Commercial and state-owned businesses employ most of the respondents. Most respondents’ enterprises, employing over 100 workers, have been in operation for more than three years.

4. Results and Analysis

The results of the survey are discussed in this part. It includes looking at the measurement model and then the structural model.

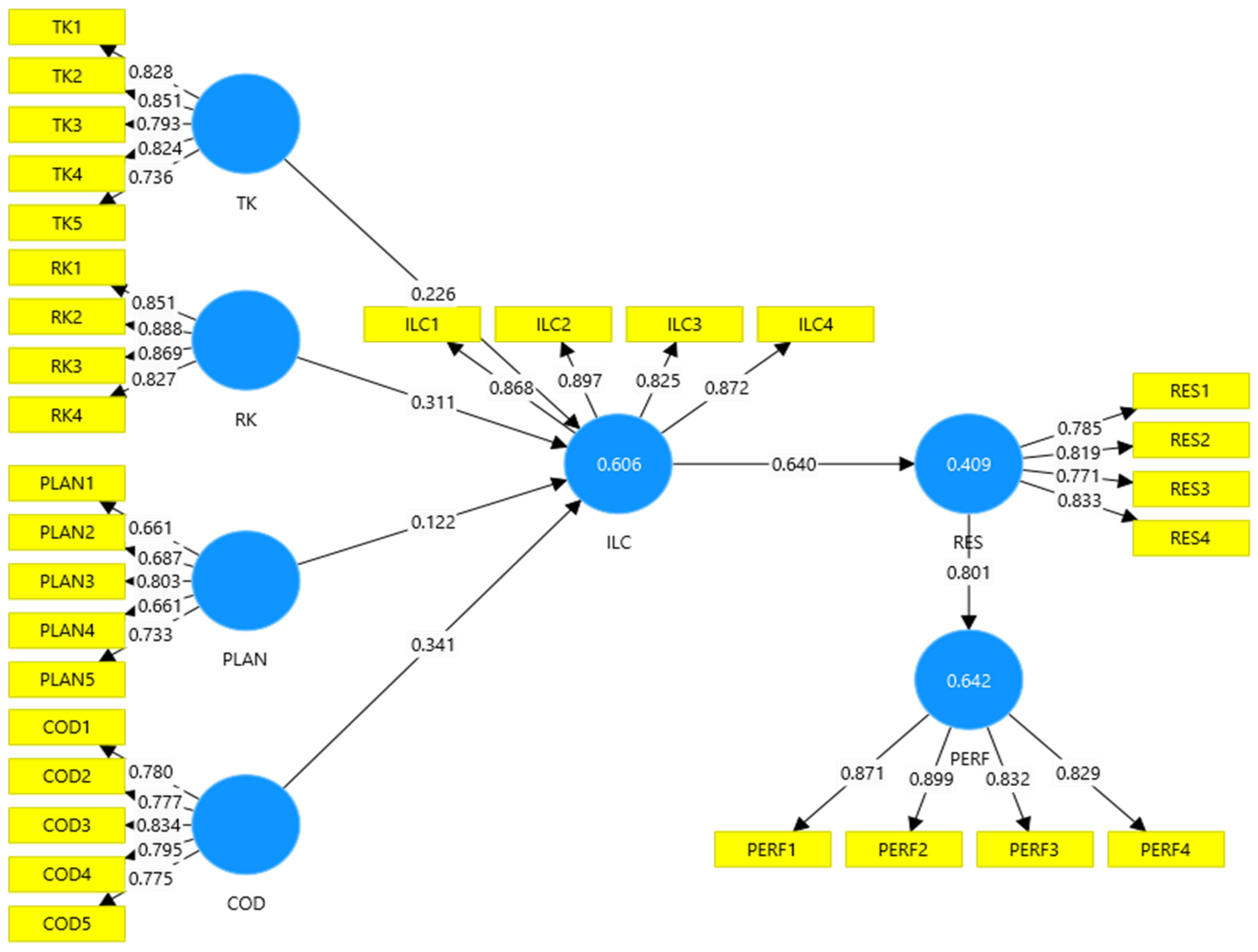

Figure 3 shows the results of the hypothesis testing that is discussed in the text.

4.1. Assessment of Outer Model

Prior to testing the suggested model for any link between its variables, it was necessary to examine the construct items to determine their effectiveness in measuring the intended construct. It’s necessary for reflective model to test the convergent and discriminant validity of the components (Joseph F. Hair et al. 2019). The findings were acquired via the Smart PLS algorithm settings. The analysis of model fit was not thoroughly explored because PLS-SEM modelling does not significantly depend on the idea of model fit, as covariance-based approaches do.

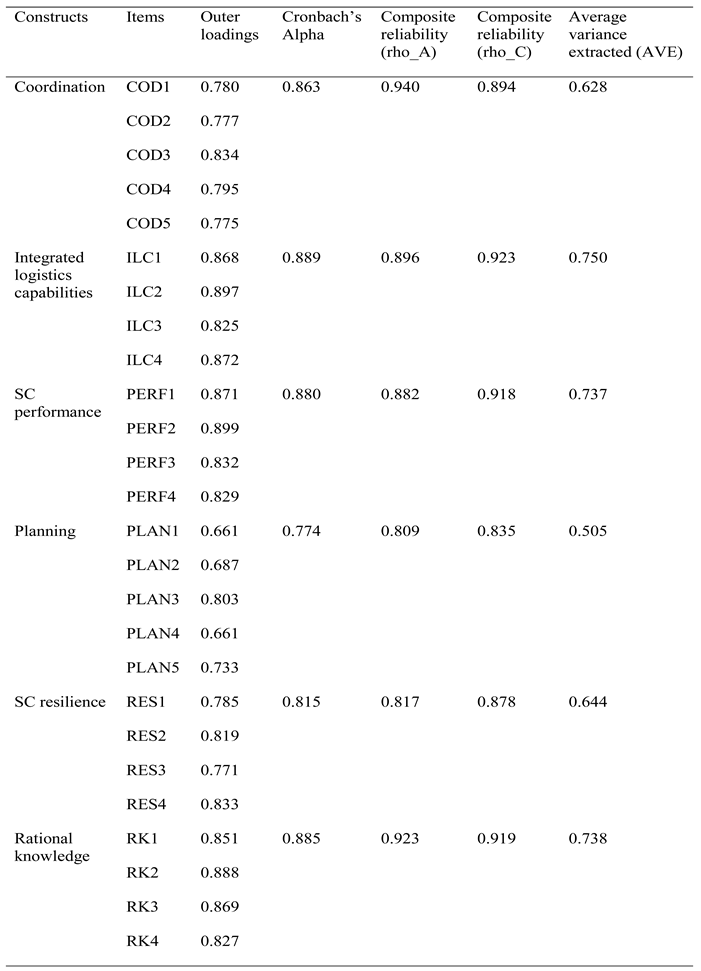

4.1.1. Model Validity and Reliability

Reliability of Constructs

To determine if the measures were reliable and consistent within themselves, we used two standards: first, that the constructs should have a Cronbach’s alpha scores above 0.7, and second, that the composite reliability minimum value of 0.7. Using composite reliability criteria was crucial to accommodate the varying reliabilities of indicators in PLS-SEM and to avoid being undervalued of Cronbach’s alpha (Jr Hair et al. 2014). The model in question seems to satisfy the reliability requirements shown in

Table 2. None of the composite reliability scores above 0.95, which is desirable since higher levels may suggest item redundancy (Diamantopoulos et al. 2012).

Convergent Validity

Term “convergent validity” defines how well a notion represents the dispersion of its constituent elements (Jr Hair et al. 2014). The outer loading of the measures was checked to make sure it was more than 0.7, and the AVE score were checked to make sure they were more than 0.5 for each item. According to the loadings, every one of the thirty-one items had a value higher than 0.7. The evaluation of the measures was conducted by mentioning outer loadings that were exceeded 0.7, as well as average variance extract values that were exceeded 0.5 for the items. A strong level of convergent validity is shown by an average variance extract score that surpasses 0.5, implying that the underlying variables account for over 50% of the variation in the indicators. The AVE values were calculated to judge the convergent validity of each concept, all of which exhibited strong convergent validity.

Discriminant Validity

Once the outer model’s convergence has been confirmed, the study proceeded to measure discriminant validity, which pertains to how distinct a concept is from other components in the structural model (Hair et al. 2019a). The verification was conducted using HTMT values. The HTMT ratio quantifies the average correlation between items that measure various constructs (Heterotrait) compared to the average relationship between assessing items that examine the same constructs (Monotrait). In accordance recommendations made by Henseler, Ringle, and Sarstedt (2015), we determine the Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio correlation. The HTMT values should be significantly below one (preferably <0.85) to clearly differentiate between two constructs (Henseler, Ringle, and Sarstedt 2015). The obtained values (below 0.85) shows enough discriminant validity, thereby confirming the distinctiveness of the data. While a value below 0.9 generally suggests discriminant validity, It is common practice to suggest a more cautious threshold of 0.85, as advised by (Henseler, Ringle, and Sarstedt 2015).

Table 3 indicate the constructs discriminant validity (HTMT).

4.2. Analyzed the Structural Model

Following the successful verification of the measurement model, the attention shifts to the structural model for assessing the suggested links and ascertaining their statistical significance. This is an important step since it means that the inner model’s believed relationships will only be considered credible and dependable if the outer model backs them up (Jr Hair et al. 2014). To make things clear, once all the tests were done,

Table 4 displays the final descriptive analysis findings of the outer model.

4.2.1. Model Prediction

Coefficient of determination (R

2) calculations are one way to evaluate a structural model’s predictive power. R

2 evaluates the cumulative influence of independent variable on the dependent variable (Jr Hair et al. 2014). There are well-defined criteria for interpreting the importance of this measurement. Three different degrees of prediction accuracy are represented by the values 0.75, 0.50, and 0.25, significant, moderate and low level respectively (Hair, Ringle, and Sarstedt 2011).

Table 5 demonstrates that the model has a moderate level of accuracy in predicting the effect of BDA capabilities (management and personal capabilities) on integrated logistics capabilities. However, its predictive ability for supply chain resilience is week. Model predictions account for 64.4% of SC performance variance, 40.9% of SC resilience, and 60.6% of integrated logistics capabilities variance.

4.2.2. Tests Hypotheses

We applied bootstrap test by using default parameters to measure the significance of the hypothesized relationships between BDA capabilities including management and personal (coordination, planning, rational knowledge, and technical knowledge) and integrated logistics capabilities (H1 to H4), as well as between integrated logistics capabilities and SC resilience (H5), and between SC resilience and SC performance (H6). This study conducted regressions using a significance level of 5%, which corresponds to a confidence level of 95%.

Table 6 demonstrates that there are consistently positive association of the variables with one another, and no negative impacts were detected.

5. Discussion of Results

Hypotheses 1 and 2 investigate the effect of BDA personal capabilities on integrated logistics capabilities with specific emphasis on technical knowledge (TK) and rational knowledge (RK). Hypothesis H1, which investigates the relationship between Technical Knowledge (TK) and Integrated Logistics Capabilities (ILC), demonstrates 4.603 is T value which surpassing the 1.96 critical value. This study discovered a strong and favourable correlation between Technical Knowledge (TK) and Integrated Logistics Capabilities (ILC), with a P value of less than the critical level of 0.000. The significant level of P value is 0.05.

Hypothesis H2 examines the correlation between Relational Knowledge (RK) as the independent variable and Integrated Logistics Capabilities (ILC) as the dependent variable. This hypothesis has a T-Stat value of 4.09, which is higher than the crucial threshold of 1.96. We find a statistically significant positive association between Relational Knowledge (RK) and Integrated Logistics Capabilities (ILC) in this study, given that the 0.000 P value is less than the 0.05 significance criterion. These findings demonstrate that technical knowledge and rational knowledge in big data analytics are essential for managing and improving integrated logistics capabilities, including capabilities related to demand, supply, and information management interfaces. According to G. Wang et al. (2016) rational knowledge in big data analytics allows firms to effectively employ predictive analytics. This capability aids in forecasting demand, identifying potential disruptions, and planning strategies to enhance the responsiveness and reliability of the SC. BDA capabilities supports the integration of various logistics roles, leading to a more cohesive and streamlined operation (Fosso Wamba et al. 2015). BDA capabilities Optimized logistics processes and accurate demand forecasting that ensure timely deliveries, enhancing customer satisfaction and loyalty (Sanders 2016). These studies confirm that BDA personal capabilities are crucial for enhancing integrated logistics capabilities because BDA personal capabilities can manage demand, supply and information efficiently and effectively. In line with these results, Chinese manufacturing industries rely on BDA capabilities to manage their supply chain operations.

Hypotheses 3 and 4 investigate the effect of BDA management capabilities on integrated logistics capabilities, with a specific emphasis on planning and coordination. The findings indicate that Hypothesis 3 supports a strong correlation between Planning (Plan) and Integrated Logistics Capabilities (ILC). According to the results T-Stat value of 3.164 was obtained, above the critical threshold of 1.96. Compared to the significance level of 0.05, the P value of 0.002 is significantly lower. Furthermore, the study discovered a significant correlation between Coordination (COD) and Integrated Logistics Capabilities (ILC) in support of Hypothesis 4. These results are shown by a P-value of 0.000, which is below the significance level of 0.05, and a T-Stat value of 4.890, which above the crucial threshold of 1.96. BDA management capabilities particularly in planning and coordination, significantly enhance the performance of integrated logistics capabilities by improving efficiency, reducing costs, enhance customer satisfaction and managing risks. Consistent with these findings G. Wang et al. (2016) illustrate that BDA management capabilities enable the analysis of historical data and market trends to accurately forecast demand. This capability facilitates improved inventory planning and mitigates risks associated with stockouts or overstock situations. Through data analysis companies can allocate resources such as Labor, vehicles and warehouse space more efficiently, ensuring that these resources are used optimally to meet demand without excess Tan et al. (2015). In contrast, BDA management capabilities provide real time visibility into the SC, enabling batter coordination among different logistics functions and stakeholders (Zhong et al. 2016). Utilizing BDA management capabilities for SC management in both manufacturing and service sectors enhances transparency, which in turn improves communication and collaboration with suppliers, distributors, and customers. This fosters a more integrated and responsive SC (Papadopoulos et al. 2017).

The results indicate that Hypothesis 5, which focuses on the incorporation of integration of logistical capabilities, positively impacts of the SC resilience. The statistical data is presented in the table, showing that the T-Stat is 15.538 (which above the critical value of 1.96), and the P value is 0.000 (below the significance threshold of 0.05). The study establishes a robust and direct correlation between Integrated Logistics Capabilities (ILC) and SC resilience. A more responsive and adaptive SC may be achieved by integrated logistics capabilities, which involve the seamless coordination and alignment of diverse logistical services. These functions include shipping, storage, and handling inventory. This approach enables organizations to better anticipate, quick response, and able to recover from disruptive situation, ultimately enhancing their overall SC resilience. BDA management and personal capabilities significantly improve integrated logistics capabilities, thereby bolstering supply chain resilience. By combining information from many sources, organizations gain immediate and comprehensive visions into their SC operations. That way, they can respond swiftly to changes in supply and demand and make educated decisions. Real-time data analytics enable dynamic adjustments to routes and schedules based on current conditions (e.g., traffic, weather), enhancing the visibility and collaborations of logistics operations (Fosso Wamba et al. 2015). From sourcing of inputs to the finished product’s delivery, big data analytics provides real time information at every stage of the SC. This transparency enables more effective tracking of goods and faster detection of disruptions (Hazen et al. 2014).

Ultimately, the findings demonstrate that the capability of a SC to recover and adapt favourably impacts its overall SC performance. Hypothesis 6, which examines the connection between SC resilience and SC performance, showed a T-Stat value of 27.666, higher above the crucial threshold of 1.96. Additionally, SC resilience has a positive and statistically significant effect on SC performance (P = 0.000, which is less than the significance level of 0.05). This study identified a notable and favourable relationship between SC Resilience and SC Performance. SC resilience enhances SC performance by enabling organizations to sustain operations and deliver products and services effectively despite disruptions. Resilient supply chains can swiftly recover from disruptions, ensuring minimal impact on production and delivery schedules. This continuity prevents delays and maintains service levels (Pettit, Fiksel, and Croxton 2010).

5.1. Indirect Effect

Utilizing predetermined research pathways, the prior study examines the statistical significance of inter-variable correlations. Strong evidence suggests that SC resilience and performance are directly related to the BDA capabilities. To confirm this, the process of bootstrapping was carried out using Smart PLS 4.0, and the findings are displayed in

Table 7. Nevertheless, the investigation did not discover any indications of mediation or moderating effects; only direct effects were demonstrated. According to the research, SC resilience is positively correlated with management and personal capabilities in big data analytics. This observation aligns with the studies conducted by Manikas, Sundarakani, and Shehabeldin (2023) which also identifies that BDA capabilities positively impact SC resilience dimensions such as preparedness and agility Furthermore, indirect effects analysis reveals that integrated logistics capabilities significantly influence supply chain performance.

6. Conclusions

Our study objective to identify the relationship between the components of BDA capabilities, namely BDA management and BDA personal capabilities, and integrated logistics capabilities, which include demand, supply, and information management interface capabilities. Furthermore, the research seeks to identify the direct relation among integrated logistics capabilities, SC resilience, and, ultimately, SC performance. There were six primary hypotheses proposed to investigate these links. The analysis in the study was conducted using SMART PLS, which is a quantitative technique. A survey was designed and disseminated among the intended demographic. The findings suggest that the BDA capabilities, both in terms of management and personal, have a substantial and influential effect on logistics capabilities. Moreover, the effect of BDA capabilities on the integrated logistics capabilities greatly improves the SC resilience. SC resilience has a significantly positive effect on SC performance. According to the reviewed literature, BDA capabilities is becoming more important for logistics and SC management.

6.1. Theocratical Contributions

Theoretically, this research has far-reaching consequences for logistics and SC operations and the immense potential of big data analytics. One of the earliest efforts to assess how BDA capabilities affect logistics integration in the SC, this study is ground breaking. It also examines how logistics capabilities affect SC resilience and performance. Despite the extensive literature on BDA capabilities and SC resilience relationship Wamba, Akter, and Guthrie 2020; Dubey, Gunasekaran, and Childe (2019) asses SC performance. The impact of logistics capability integration on SC resilience and the role of big data analytics on this impact was not well understood. Therefore, our study examines the role of BDA capabilities for integration of logistics capabilities and their impact on resilience utilizing data from Chinese companies. This study used logistics capabilities at the SC level to improve the SC resilience in a single model. In the exiting research, the combined effect of BDA capabilities and integrated logistics capabilities to enhance SC resilience has not been studies yet. In contrast, BDA capabilities refer to the ongoing process of making fundamental changes to companies to align their capabilities with the demand and supply of the market and industry. To keep up with the ever-changing demands of their business, Chinese manufacturing enterprises need to improve their SC management and logistics. This research sheds light on how the ability to analyse large data might improve a company’s responsiveness to changing conditions and unexpected events. As a result, recognizing, grabbing opportunities, and rethinking logistical procedures are crucial. Integrated logistics capabilities strive to minimise inefficiencies, optimise the allocation of resources, and guarantee the prompt delivery of raw materials to successfully fulfil consumer expectations. The report affirms that companies should prioritise the timely provision of supplies and labour to improve production efficiency and efficiently handle client expectations. Precise understanding of the availability of raw materials, effective distribution of resources, and minimising waste are essential for incorporating logistical skills into the supply chain (SC).

Furthermore, the utilisation of big data analytics (BDA) has a beneficial impact on the integrated logistics capabilities, highlighting the importance for companies to allocate resources towards sophisticated IT infrastructure to gather, analyse, and distribute information in a timely manner. Efficient dissemination of information mitigates the bullwhip effect, facilitating enhanced integration of logistical capabilities within the supply chain. Companies that effectively handle consumer demand are in a more advantageous position to include their logistical skills into the supply chain. To achieve successful integration of logistical skills across supply chain partners, the focal business must guarantee that partners are provided with requisite information. The study indicates that the exchange of information is crucial for integrating logistical capabilities at the supply chain level, which in turn leads to the enhancement of supply chain resilience and enhanced supply chain performance. The research provides empirical evidence that supply chain (SC) resilience has a favourable effect on overall performance. SC performance refers to the accomplishments of different tasks within the SC domain.

6.2. Managerial Contributions

The practical implications of this research are substantial, providing managers and consultants with actionable insights and tools to utilize big data analytics effectively for improving logistics capabilities, resilience, and overall supply chain performance. In recent years big data analytics capabilities taken remarkable importance in SC and logistics operations of the industry. There is growing demand for comprehensive integration, redesign and performance assessment indicator specially tailored for BDA capabilities in the context of digital transformation. by adopting these practices managers can achieve greater operational efficiency, cost saving, customer satisfactions, and competitive advantages, ultimately ensuring long term success and sustainability for the industry in dynamic business environment. The results demonstrate that BDA capabilities including management and personal capabilities has strong impact on integrated logistics capabilities, so managers need to concentrate on these capabilities which leads to enhance the efficiency of demand, supply and information management interface capabilities. Furthermore, by implementation of BDA capabilities, logistics capabilities become more adaptive and more resilient to disruption, enabling supply chain and logistics to maintain their operations under adverse condition. To enhance the understanding and utilization of BDA in logistics, a company must develop management and individual capabilities in big data analytics. This will enable the company to increase the effectiveness of logistics operations, enhance SC resilience, and enhance overall SC performance. Consequently, big data analytics capabilities (BDA capabilities) is essential for improving logistics by enhancing demand forecasting, optimizing resource allocation, and reducing costs. BDA capabilities supports transparency and collaboration, enabling swift responses to supply chain disruptions. By integrating and analyzing data, BDA capabilities strengthens supply chain resilience, ensuring consistent operations and delivery even in the face of challenges.

Moreover, this study highlights the critical role of integrated logistics capabilities in enhancing supply chain resilience and performance during emergencies. The research demonstrates that integrating logistics at the SC level is essential for developing SC capabilities. As a result, managers should focus on training SC members to improve their logistics capabilities and foster strong relationships with suppliers to ensure the timely supply of raw materials for production. Managers should also work on developing key logistics capabilities—demand management, supply management, and information management—across all SC entities. This will lead to effective integration and the development of SC capabilities. Furthermore, managers need to recognize that effective integration of logistics capabilities will promote SC collaboration and visibility, which are crucial for developing other SC capabilities, such as flexibility and velocity which ultimately improve supply chain resilience and performance. The study provides an empirically validated framework for firms to adopt strategies that enhance SC resilience and better prepare for disruptions.

6.3. Limitations and Future Recommendations

We have confidence in the validity of our model, as it is based on solid theoretical foundations and has been rigorously validated using credible survey instruments and data. Nevertheless, it is difficult to recognize and address limitations and unanswered questions. Our study was conducted exclusively in the field of big data analytics, with a specific focus on a single case. Our research may be specific to certain industry or context, limiting their generalizability to other sectors or regions. Big data analytics is intrinsically dependent on the unique environment in which it is applied. Replicating the theoretical model in other situations would enhance its ability to be applied more broadly. Furthermore, we performed a model evaluation utilizing cross-sectional data. Therefore, we suggest that the conclusions be retested using panel data to examine its reliability. Thirdly, we used only two aspects of BDA capabilities management and personal capabilities in our conceptual model to assess logistics capabilities. Future researchers could use all three aspects of the BDA capabilities to assess logistics capabilities. Furthermore, we did not examine the impact of risk management culture on the application of BDA capabilities within the firm. Utilizing big data, analytics A risk management culture that allows the SC to sustain their operations in challenging conditions. Future researchers could be used risk management culture as moderator to extend knowledge in big data analytics approach. Lastly, the above theoretical limitations, this study restricted to Chinese manufacturing industry that operate with in china which may have unique culture and organizational attributes. Further exploration of this topic could be cross border investigation between china and Pakistan on the basses of CPEC project.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the national natural science foundation of china (Grant No. 72104037), the innovation capability support programme of Shaanxi province (No.2024ZC-YBXM-126), the social science foundation of Shaanxi province (2021D024), the fundamental research funds for the central universities, CHD (300102231647)

References

- S, Balakrishnan, and Usha Ramanathan. The Role of Digital Technologies in Supply Chain Resilience for Emerging Markets’ Automotive Sector. Supply Chain Management 2021, 26, 654–671. [Google Scholar]

- Abaker, Ibrahim et al. The Rise of ‘Big Data’ on Cloud Computing: Review and Open Research Issues. Information Systems 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Addo-Tenkorang, Richard, and Petri T. Helo. Big Data Applications in Operations/Supply-Chain Management: A Literature Review. Computers and Industrial Engineering 2016, 101, 528–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Talib, Moayad et al. Achieving Resilience in the Supply Chain by Applying IoT Technology. Procedia CIRP 2020, 91, 752–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assunção, Marcos D. et al. Big Data Computing and Clouds: Trends and Future Directions. Journal of Parallel and Distributed Computing 2015, 79–80, 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Bag, Surajit et al. Industry 4.0 and the Circular Economy: Resource Melioration in Logistics. Resources Policy, 2020; 68. [Google Scholar]

- Bag, Surajit, Pavitra Dhamija, Sunil Luthra, and Donald Huisingh. How Big Data Analytics Can Help Manufacturing Companies Strengthen Supply Chain Resilience in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Logistics Management 2023, 34, 1141–1164. [Google Scholar]

- Bahrami, Mohamad, and Sajjad Shokouhyar. The Role of Big Data Analytics Capabilities in Bolstering Supply Chain Resilience and Firm Performance: A Dynamic Capability View. Information Technology and People 2022, 35, 1621–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brekalo, Lisa, Sascha Albers, and Werner Delfmann. Logistics Alliance Management Capabilities—Where Are They?” Academy of Management Proceedings 2012, 2012, 11905.

- Carvalho, Helena, Susana Duarte, and V. Cruz Machado. Lean, Agile, Resilient and Green: Divergencies and Synergies. International Journal of Lean Six Sigma 2011, 2, 151–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Tsan Ming, Subodha Kumar, Xiaohang Yue, and Hau Ling Chan. Disruptive Technologies and Operations Management in the Industry 4.0 Era and Beyond. Production and Operations Management 2022, 31, 9–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, Martin. The Agile Supply Chain. Industrial Marketing Management 2000, 29, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, Martin, and Matthias Holweg. ‘Supply Chain 2.0’: Managing Supply Chains in the Era of Turbulence. International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management 2011, 41, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, Martin, and Hau Lee. Mitigating Supply Chain Risk through Improved Confidence. International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management 2004, 34, 388–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalmarco, Gustavo, Filipa R. Ramalho, Ana C. Barros, and Antonio L. Soares. Providing Industry 4.0 Technologies: The Case of a Production Technology Cluster. Journal of High Technology Management Research 2019, 30.

- Dennehy, Denis et al. Supply Chain Resilience in Mindful Humanitarian Aid Organizations: The Role of Big Data Analytics. International Journal of Operations and Production Management 2021, 41, 1417–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, Adamantios et al. Guidelines for Choosing between Multi-Item and Single-Item Scales for Construct Measurement: A Predictive Validity Perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 2012, 40, 434–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donald, J. Bowersox, David J. Closs, and Theodore P. Stank. Ten Mega-Trends That Will Revolutionize Supply Chain Logistics. Journal of Business Logistics 2000, 21, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Drucker, Peter F. The Economy’s Dark Continent. The Roots of Logistics 2012, 97–105.

- Dubey, Rameshwar, Angappa Gunasekaran, and Stephen J. Childe. Big Data Analytics Capability in Supply Chain Agility: The Moderating Effect of Organizational Flexibility. Management Decision 2019, 57, 2092–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esper, Terry L. , Brian S. Fugate, and Beth Davis-Sramek. Logistics Learning Capability: Sustaining the Competitive Advantage Gained Through Logistics Leverage. Journal of Business Logistics 2007, 28, 57–82. [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett, Stanley E. , Sheldon R. Smith, and M. Bixby Cooper. Strategic Intent, Measurement Capability, and Operational Success: Making the Connection. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 1997, 27, 410–421. [Google Scholar]

- Fosso Wamba, Samuel et al. How ‘big Data’ Can Make Big Impact: Findings from a Systematic Review and a Longitudinal Case Study. International Journal of Production Economics 2015, 165, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galati, Francesco, and Barbara Bigliardi. Industry 4.0: Emerging Themes and Future Research Avenues Using a Text Mining Approach. Computers in Industry 2019, 109, 100–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gärtner, Bernhard, and Martin R. W. Hiebl. Issues with Big Data. W. Hiebl. Issues with Big Data. The Routledge Companion to Accounting Information Systems 2019, 161–172. [Google Scholar]

- Gligor, David M. , and Mary C. Holcomb. Understanding the Role of Logistics Capabilities in Achieving Supply Chain Agility: A Systematic Literature Review. Supply Chain Management 2012, 17, 438–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gligor, David Marius, and Mary C. Holcomb. Antecedents and Consequences of Integrating Logistics Capabilities across the Supply Chain. Transportation Journal 2014, 53, 211–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, Kannan, T. C.E. Cheng, Nishikant Mishra, and Nagesh Shukla. Big Data Analytics and Application for Logistics and Supply Chain Management. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review 2018, 114, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, Shivam et al. Examining the Influence of Big Data Analytics and Additive Manufacturing on Supply Chain Risk Control and Resilience: An Empirical Study. Computers and Industrial Engineering 2022, 172.

- Hair, Joe F. , Christian M. Ringle, and Marko Sarstedt. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazen, Benjamin T. , Christopher A. Boone, Jeremy D. Ezell, and L. Allison Jones-Farmer. Data Quality for Data Science, Predictive Analytics, and Big Data in Supply Chain Management: An Introduction to the Problem and Suggestions for Research and Applications. International Journal of Production Economics 2014, 154, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, Jörg, Christian M. Ringle, and Marko Sarstedt. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, Erik, and Marco Rüsch. Industry 4.0 and the Current Status as Well as Future Prospects on Logistics. Computers in Industry 2017, 89, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji-fan Ren, Steven et al. Big Data Analytics and Firm Performance: Effects of Dynamic Capabilities. Journal of Business Research 2017, 70.

- Joseph, F. Hair, Jeffrey J. Risher, Marko Sarstedt, and Christian M. Ringle. When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar]

- Jr Hair, Joe, Lucas Hopkins, Middle Georgia, and State College. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) An Emerging Tool in Business Research. European Business Review 2014, 26, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jüttner, Uta, and Stan Maklan. Supply Chain Resilience in the Global Financial Crisis: An Empirical Study. Supply Chain Management 2011, 16, 246–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondraganti, Abhilash, Gopalakrishnan Narayanamurthy, and Hossein Sharifi. A Systematic Literature Review on the Use of Big Data Analytics in Humanitarian and Disaster Operations. A Systematic Literature Review on the Use of Big Data Analytics in Humanitarian and Disaster Operations. Annals of Operations Research 2022.

- Lagorio, Alexandra, Giovanni Zenezini, Giulio Mangano, and Roberto Pinto. A Systematic Literature Review of Innovative Technologies Adopted in Logistics Management. International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications 2022, 25, 1043–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, Douglas M. , and Martha C. Cooper. Issues in Supply Chain Management. Industrial Marketing Management 2000, 29, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Qi, and Ang Liu. Big Data Driven Supply Chain Management. Procedia CIRP 2019, 81, 1089–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Yang. Industry 4.0: A Survey on Technologies, Applications and Open Research Issues. Journal of Industrial Information Integration 2017, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, Daniel F. , Scott B. Keller, and John Ozment. The Effects of Logistics Capabilities and Strategy on Firm Performance. Journal of Business Logistics 2000, 21, 47–67. [Google Scholar]

- M. C. Cooper, D. M. Lambert, and J. D. Pagh. Supply Chain Management: More than a New Name for Logistics. The international journal of logistics management 1997, 8.

- Mageto, Joash. Big Data Analytics in Sustainable Supply Chain Management: A Focus on Manufacturing Supply Chains. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2021, 13.

- Mandal, Santanu. The Influence of Big Data Analytics Management Capabilities on Supply Chain Preparedness, Alertness and Agility: An Empirical Investigation. Information Technology and People 2019, 32, 297–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, Santanu, Sourabh Bhattacharya, Venkateswara Rao Korasiga, and Rathin Sarathy. The Dominant Influence of Logistics Capabilities on Integration: Empirical Evidence from Supply Chain Resilience. International Journal of Disaster Resilience in the Built Environment 2017, 8, 357–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manikas, Ioannis, Balan Sundarakani, and Mohamed Shehabeldin. Big Data Utilisation and Its Effect on Supply Chain Resilience in Emirati Companies. International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications 2023, 26, 1334–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentzer, John T. , Daniel J. Flint, and G. Tomas M. Hult. Logistics Service Quality as a Segment-Customized Process. Journal of Marketing 2001, 65, 82–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentzer, John T. , Soonhong Min, and L. Michelle Bobbitt. Toward a Unified Theory of Logistics. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 2004, 34, 606–627. [Google Scholar]

- Mentzer, John T. , Theodore P. Stank, and Terry L. Esper. Supply Chain Management and Its Relationship To Logistics, Marketing, Production, and Operations Management. Journal of Business Logistics 2008, 29, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morash, Edward a. , Cornelia L. M. Droge, and Shawnee K Vickery. Strategic Logistics Capabilities for Competitive Advantage and Firm Success. Journal of Business Logistics 1996, 17, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Morash, Edward A. , Cornelia Dröge, and Shawnee Vickery. Boundary-Spanning Interfaces between Logistics, Production, Marketing and New Product Development. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 1997, 27, 350–369. [Google Scholar]

- Osmólski, Waldemar, Adam Koliński, and Zafer Kilic. Concept of Communication Integration for Automated Production Processes Regarding Logistics 4.0. Concept of Communication Integration for Automated Production Processes Regarding Logistics 4.0. Digitalization of Supply Chains 2020, 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Papadopoulos, Thanos, Angappa Gunasekaran, Rameshwar Dubey, and Samuel Fosso Wamba. Big Data and Analytics in Operations and Supply Chain Management: Managerial Aspects and Practical Challenges. Production Planning and Control 2017, 28, 873–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, Timothy J. , Joseph Fiksel, and Keely L. Croxton. Ensuring Supply Chain Resilience: Development of a Conceptual Framework. Journal of Business Logistics 2010, 31, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponomarov, Serhiy Y. , and Mary C. Holcomb. Understanding the Concept of Supply Chain Resilience. The International Journal of Logistics Management 2009, 20, 124–143. [Google Scholar]

- Raj, Alok et al. Barriers to the Adoption of Industry 4.0 Technologies in the Manufacturing Sector: An Inter-Country Comparative Perspective. International Journal of Production Economics 2020, 224.

- Raut, Rakesh D et al. Big Data Analytics as a Mediator in Lean, Agile, Resilient, and Green (LARG) Practices Effects on Sustainable Supply Chains. Transportation Research Part E 2021, 145, 102170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, Erik, and Mats Abrahamsson. Logistics Capabilities for Sustainable Competitive Advantage. International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications 2011, 14, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, Nada R. How to Use Big Data to Drive Your Supply Chain. California Management Review 2016, 58, 26–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, E Fawcett, M Magnan Gregory, and W McCarter Matthew. Benefits, Barriers, and Bridges to Effective Supply Chain Management. Supply Chain Management 2008, 13, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenger, Alan J. Advances in Information Technology Applications for Supply Chain Management. Transportation Journal 2011, 50, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundarakani, Balan, Aneesh Ajaykumar, and Angappa Gunasekaran. Big Data Driven Supply Chain Design and Applications for Blockchain: An Action Research Using Case Study Approach. Omega (United Kingdom) 2021, 102.

- Tan, Kim Hua et al. Harvesting Big Data to Enhance Supply Chain Innovation Capabilities: An Analytic Infrastructure Based on Deduction Graph. International Journal of Production Economics 2015, 165, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamba, Samuel Fosso, Shahriar Akter, and Cameron Guthrie. Making Big Data Analytics Perform: The Mediating Effect of Big Data Analytics Dependent Organizational Agility. Systemes d’Information et Management 2020, 25, 7–31. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Gang, Angappa Gunasekaran, Eric W. T. Ngai, and Thanos Papadopoulos. Big Data Analytics in Logistics and Supply Chain Management: Certain Investigations for Research and Applications. International Journal of Production Economics 2016, 176, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Michael, Sobhan Asian, Lincoln C. Wood, and Bill Wang.. Logistics Innovation Capability and Its Impacts on the Supply Chain Risks in the Industry 4.0 Era. Modern Supply Chain Research and Applications 2020, 2, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Yuh Horng. Impact of Collaborative Transportation Management on Logistics Capability and Competitive Advantage for the Carrier. Transportation Journal 2012, 51, 452–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]