Submitted:

05 June 2025

Posted:

06 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Acquisition of Liver Transcriptomics Datasets

2.2. Transcriptomics and Pathway-Based Enrichment Analysis of Metabolic Genes

2.3. Transcriptomics Data Integration with iMM1865 Mouse GEM

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Data and Code Availability

3. Results

3.1.1. PFESA-BP2 Hepatotoxicity in BALB/c Mice Targets Lipid Metabolism in a Sex- and Dose-Dependent Pattern

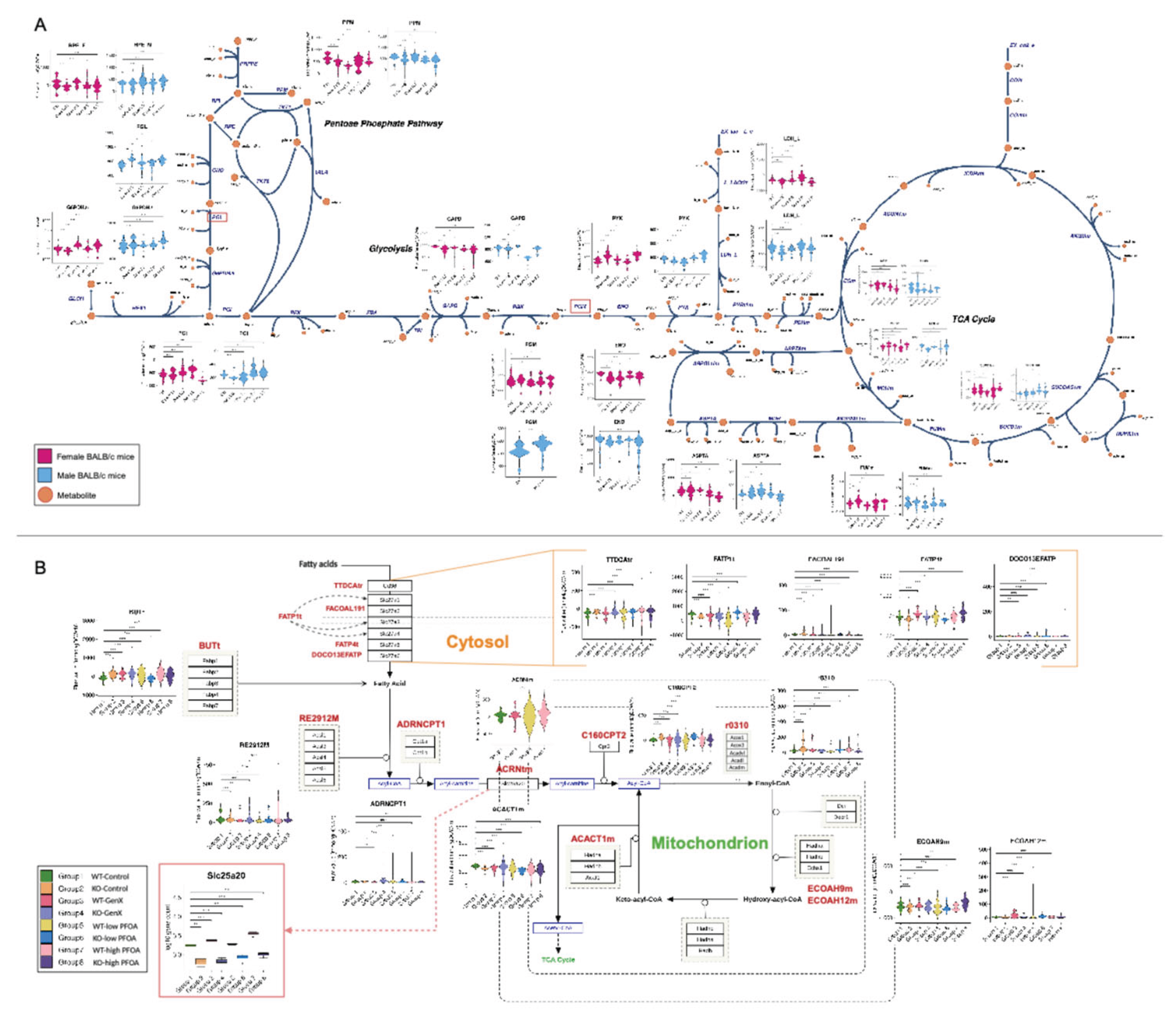

3.1.2. PFESA-BP2 Hepatotoxicity in BALB/c Mice Is Associated with Energy Dyshomeostasis

3.1.3. PFOA and GenX Exposure Targets Fatty Acid and Lipid Metabolism

3.1.4. Identifying Perturbations in Energy and Lipid Metabolism Due to PFAS Exposure Using Integrated Genome-Scale Metabolic Models

3.1.5. PFESA-BP2 Exposure Causes Activation of Cholesterol Biosynthesis in a Dose-Dependent Manner

3.1.6. PFAS Exposure Causes Energy Dyshomeostasis via Targeting Carbon Metabolism and β-Oxidation

4. Discussion

Limitations of the Study

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data availability statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase pathway |

| BBB | Blood-brain barrier |

| COBRA | Constraint-based reconstruction and analysis |

| DEGs | Differentially expressed genes |

| FA | Fatty acid |

| FBA | Flux balance analysis |

| FVA | Flux variability analysis |

| GEM | Genome-scale metabolic model |

| GenX | Hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid |

| GEO | Gene expression omnibus |

| GSEA | Gene set enrichment analysis |

| iMAT | Integrative metabolic analysis tool |

| mTOR | Mammalian target of rapamycin pathway |

| PPP | Pentose phosphate pathway |

| PPAR | Peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor |

| PFAS | Per-(poly) fluoroalkyl substances |

| PFOA | Perfluorooctanoic acid |

| PFESA-BP2 | 7H-Perfluoro-4-methyl-3,6-dioxaoctanesulfonic acid |

| SREPF | Sterol regulatory element-binding transcription factors |

| TCA | Tricarboxylic acid |

References

- Panel EC, Schrenk D, Bignami M, Bodin L, Chipman JK, Del Mazo J, Grasl-Kraupp B, Hogstrand C, Hoogenboom LR, Leblanc J-C. Annexes to the Risk to human health related to the presence of perfluoroalkyl substances in food. 2020.

- Cao L, Guo Y, Chen Y, Hong J, Wu J, Hangbiao J. Per-/polyfluoroalkyl substance concentrations in human serum and their associations with liver cancer. Chemosphere. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Corton JC, Gift JS, Auerbach SS, Liu J, Das KP, Ren H, Lang JR, Chernoff N, Lau C, Hill D Dose–response modeling of effects in mice after exposure to a polyfluoroalkyl substance (Nafion byproduct 2). Toxicological Sciences kfaf042 2025.

- Conley JM, Lambright CS, Evans N, et al Developmental toxicity of Nafion byproduct 2 (NBP2) in the Sprague-Dawley rat with comparisons to hexafluoropropylene oxide-dimer acid (HFPO-DA or GenX) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS). Environ Int. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Quist EM, Filgo AJ, Cummings CA, Kissling GE, Hoenerhoff MJ, Fenton SE Hepatic Mitochondrial Alteration in CD-1 Mice Associated with Prenatal Exposures to Low Doses of Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA). Toxicol Pathol 2015, 43, 546–557. [CrossRef]

- Gao B, Tu PC, Chi L, Shen W, Gao N Perfluorooctanoic Acid-Disturbed Serum and Liver Lipidome in C57BL/6 Mice. Chem Res Toxicol. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kostecki G, Chuang K, Buxton A, Dakshanamurthy S Dose-Dependent PFESA-BP2 Exposure Increases Risk of Liver Toxicity and Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Kirkwood-Donelson KI, Chappel J, Tobin E, Dodds JN, Reif DM, DeWitt JC, Baker ES Investigating mouse hepatic lipidome dysregulation following exposure to emerging per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Chemosphere. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Salihovic S, Fall T, Ganna A, Broeckling CD, Prenni JE, Hyötyläinen T, Kärrman A, Lind PM, Ingelsson E, Lind L Identification of metabolic profiles associated with human exposure to perfluoroalkyl substances. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Rashid F, Dubinkina V, Ahmad S, Maslov S, Irudayaraj JMK Gut Microbiome-Host Metabolome Homeostasis upon Exposure to PFOS and GenX in Male Mice. Toxics. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Conley JM, Lambright CS, Evans N, McCord J, Strynar MJ, Hill D, Medlock-Kakaley E, Wilson VS, Gray LE Hexafluoropropylene oxide-dimer acid (HFPO-DA or GenX) alters maternal and fetal glucose and lipid metabolism and produces neonatal mortality, low birthweight, and hepatomegaly in the Sprague-Dawley rat. Environ Int. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Blake BE, Cope HA, Hall SM, et al Evaluation of maternal, embryo, and placental effects in CD-1 mice following gestational exposure to perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) or hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid (HFPO-DA or GenX). Environ Health Perspect. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Guillette TC, McCord J, Guillette M, et al Elevated levels of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in Cape Fear River Striped Bass (Morone saxatilis) are associated with biomarkers of altered immune and liver function. Environ Int. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Fenton SE, Ducatman A, Boobis A, DeWitt JC, Lau C, Ng C, Smith JS, Roberts SM Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substance Toxicity and Human Health Review: Current State of Knowledge and Strategies for Informing Future Research. Environ Toxicol Chem 2021, 40, 606–630.

- Pouwer MG, Pieterman EJ, Chang SC, Olsen GW, Caspers MPM, Verschuren L, Wouter Jukema J, Princen HMG Dose Effects of Ammonium Perfluorooctanoate on Lipoprotein Metabolism in APOE∗3-Leiden. CETP Mice. Toxicological Sciences. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlezinger JJ, Puckett H, Oliver J, Nielsen G, Heiger-Bernays W, Webster TF Perfluorooctanoic acid activates multiple nuclear receptor pathways and skews expression of genes regulating cholesterol homeostasis in liver of humanized PPARα mice fed an American diet. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2020. [CrossRef]

- DeWitt JC, Shnyra A, Badr MZ, et al Immunotoxicity of perfluorooctanoic acid and perfluorooctane sulfonate and the role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Takacs ML, Abbott BD Activation of mouse and human peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (α, β/δ, γ) by perfluorooctanoic acid and perfluorooctane sulfonate. Toxicological Sciences. 2007. [CrossRef]

- Attema B, Janssen AWF, Rijkers D, van Schothorst EM, Hooiveld GJEJ, Kersten S Exposure to low-dose perfluorooctanoic acid promotes hepatic steatosis and disrupts the hepatic transcriptome in mice. Mol Metab. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Baloni P, Sangar V, Yurkovich JT, Robinson M, Taylor S, Karbowski CM, Hamadeh HK, He YD, Price ND Genome-scale metabolic model of the rat liver predicts effects of diet restriction. Sci Rep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Baloni P, Funk CC, Yan J, et al Metabolic Network Analysis Reveals Altered Bile Acid Synthesis and Metabolism in Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell Rep Med. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Khodaee S, Asgari Y, Totonchi M, Karimi-Jafari MH iMM1865: A New Reconstruction of Mouse Genome-Scale Metabolic Model. Sci Rep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Barrett T, Wilhite SE, Ledoux P, et al NCBI GEO: Archive for functional genomics data sets - Update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Lang JR, Strynar MJ, Lindstrom AB, Farthing A, Huang H, Schmid J, Hill D, Chernoff N Toxicity of Balb-c mice exposed to recently identified 1,1,2,2-tetrafluoro-2-[1,1,1,2,3,3-hexafluoro-3-(1,1,2,2-tetrafluoroethoxy)propan-2-yl]oxyethane-1-sulfonic acid (PFESA-BP2). Toxicology. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Love MI, Huber W, Anders S Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Moustafa MAM, Mohamed WMA, Lau ACC, et al R A language and environment for statistical computing, R Foundation for Statistical. Computing 2020, 20.

- Evangelista JE, Xie Z, Marino GB, Nguyen N, Clarke DJB, Ma’Ayan A Enrichr-KG: Bridging enrichment analysis across multiple libraries. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Milacic M, Beavers D, Conley P, et al The Reactome Pathway Knowledgebase 2024. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Aleksander SA, Balhoff J, Carbon S, et al The Gene Ontology knowledgebase in 2023. Genetics. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, et al Gene ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. Nat Genet 2000. [CrossRef]

- Smith CL, Eppig JT The mammalian phenotype ontology: Enabling robust annotation and comparative analysis. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med 2009. [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa M, Sato Y, Kawashima M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res 2016. [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson L ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis by WICKHAM, H. Biometrics 2011. [CrossRef]

- Gao CH, Chen C, Akyol T, Dusa A, Yu G, Cao B, Cai P ggVennDiagram: Intuitive Venn diagram software extended. iMeta 2024. [CrossRef]

- Chen H, Boutros PC VennDiagram: A package for the generation of highly-customizable Venn and Euler diagrams in R. BMC Bioinformatics 2011. [CrossRef]

- Engler JB Tidyplots empowers life scientists with easy code-based data visualization. iMeta 2025, 4, e70018. [CrossRef]

- Zur H, Ruppin E, Shlomi T iMAT: An integrative metabolic analysis tool. Bioinformatics 2010. [CrossRef]

- Heirendt L, Arreckx S, Pfau T, et al Creation and analysis of biochemical constraint-based models using the COBRA Toolbox v. 3.0. Nat Protoc 2019. [CrossRef]

- Robinson M, Zimmer A, Farrah T, Mauldin D, Price N, Hood L, Glusman G Scale-invariant geometric data analysis (SIGDA) provides robust, detailed visualizations of human ancestry specific to individuals and populations. bioRxiv 2018.

- Gudmundsson S, Thiele I Computationally efficient flux variability analysis. BMC Bioinformatics 2010. [CrossRef]

- Schellenberger J, Que R, Fleming RMT, et al Quantitative prediction of cellular metabolism with constraint-based models: The COBRA Toolbox v2. 0. Nat Protoc 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim A, Lerman JA, Palsson BO, Hyduke DR COBRApy: COnstraints-Based Reconstruction and Analysis for Python. BMC Syst Biol 2013. [CrossRef]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol 1995. [CrossRef]

- Kotlarz N, McCord J, Collier D, et al Measurement of novel, drinking water-associated pfas in blood from adults and children in Wilmington, North Carolina. Environ Health Perspect 2020. [CrossRef]

- Hopkins ZR, Sun M, DeWitt JC, Knappe DRU Recently Detected Drinking Water Contaminants: GenX and Other Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Ether Acids. J Am Water Works Assoc 2018. [CrossRef]

- Wang G, Li M, Wang Y, Wang B, Pu H, Mao J, Zhang S, Zhou S, Luo P Characterization of differentially expressed and lipid metabolism-related lncRNA-mRNA interaction networks during the growth of liver tissue through rabbit models. Front Vet Sci 2022. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Yu H, Gao R, Liu M, Xie W A comprehensive review of the family of very-long-chain fatty acid elongases: structure, function, and implications in physiology and pathology. Eur J Med Res 2023. [CrossRef]

- Bishop-Bailey D, Thomson S, Askari A, Faulkner A, Wheeler-Jones C Lipid-metabolizing CYPs in the regulation and dysregulation of metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr 2014. [CrossRef]

- Talley JT, Mohiuddin SS (2020) Biochemistry, Fatty Acid Oxidation.

- Chiang JYL, Ferrell JM Up to date on cholesterol 7 alpha-hydroxylase (CYP7A1) in bile acid synthesis. Liver Res 2020. [CrossRef]

- Liu H, Wang S, Wang J, Guo X, Song Y, Fu K, Gao Z, Liu D, He W, Yang L-L Energy metabolism in health and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2025, 10, 69.

- Guo H, Chen J, Zhang H, Yao J, Sheng N, Li Q, Guo Y, Wu C, Xie W, Dai J Exposure to GenX and Its Novel Analogs Disrupts Hepatic Bile Acid Metabolism in Male Mice. Environ Sci Technol 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kersten S, Stienstra R The role and regulation of the peroxisome proliferator activated receptor alpha in human liver. Biochimie 2017, 136, 75–84. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang X, Ren X, Sun W, Griffin N, Wang L, Liu H PFOA exposure induces aberrant glucose and lipid metabolism in the rat liver through the AMPK/mTOR pathway. Toxicology 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kuriya Y, Murata M, Yamamoto M, Watanabe N, Araki M Prediction of Metabolic Flux Distribution by Flux Sampling: As a Case Study, Acetate Production from Glucose in Escherichia coli. Bioengineering 2023. [CrossRef]

- Yoon H, Shaw JL, Haigis MC, Greka A Lipid metabolism in sickness and in health: Emerging regulators of lipotoxicity. Mol Cell 2021. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal A, Balcı H, Hanspers K, et al WikiPathways 2024: next generation pathway database. Nucleic Acids Res 2024. [CrossRef]

- King ZA, Dräger A, Ebrahim A, Sonnenschein N, Lewis NE, Palsson BO Escher: A Web Application for Building, Sharing, and Embedding Data-Rich Visualizations of Biological Pathways. PLoS Comput Biol 2015. [CrossRef]

- Sunderland EM, Hu XC, Dassuncao C, Tokranov AK, Wagner CC, Allen JG A review of the pathways of human exposure to poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) and present understanding of health effects. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol 2019, 29, 131–147. [CrossRef]

- Schillemans T, Bergdahl IA, Hanhineva K, Shi L, Donat-Vargas C, Koponen J, Kiviranta H, Landberg R, Åkesson A, Brunius C Associations of PFAS-related plasma metabolites with cholesterol and triglyceride concentrations. Environ Res 2023. [CrossRef]

- India-Aldana S, Yao M, Midya V, et al PFAS Exposures and the Human Metabolome: A Systematic Review of Epidemiological Studies. Curr Pollut Rep 2023. [CrossRef]

- Permuth-Wey J, Chen YA, Tsai YY, et al Inherited variants in mitochondrial biogenesis genes may influence epithelial ovarian cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention 2011. [CrossRef]

- Mikkelsen ACD, Kjærgaard K, Schapira AHV, Mookerjee RP, Thomsen KL The liver–brain axis in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2025, 10, 248–258. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan Y, Short JL, Choy KHC, Zeng AX, Marriott PJ, Owada Y, Scanlon MJ, Porter CJH, Nicolazzo JA Fatty Acid-Binding Protein 5 at the Blood–Brain Barrier Regulates Endogenous Brain Docosahexaenoic Acid Levels and Cognitive Function. The Journal of Neuroscience 2016, 36, 11755. [CrossRef]

- Canova C, Barbieri G, Zare Jeddi M, Gion M, Fabricio A, Daprà F, Russo F, Fletcher T, Pitter G Associations between perfluoroalkyl substances and lipid profile in a highly exposed young adult population in the Veneto Region. Environ Int 2020. [CrossRef]

- Olsen GW, Zobel LR Assessment of lipid, hepatic, and thyroid parameters with serum perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) concentrations in fluorochemical production workers. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2007. [CrossRef]

- Steenland K, Tinker S, Frisbee S, Ducatman A, Vaccarino V Association of perfluorooctanoic acid and perfluorooctane sulfonate with serum lipids among adults living near a chemical plant. Am J Epidemiol 2009. [CrossRef]

- Quist EM, Filgo AJ, Cummings CA, Kissling GE, Hoenerhoff MJ, Fenton SE Hepatic Mitochondrial Alteration in CD-1 Mice Associated with Prenatal Exposures to Low Doses of Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA). Toxicol Pathol 2015, 43, 546–557. [CrossRef]

- Peng S, Yan L, Zhang J, Wang Z, Tian M, Shen H An integrated metabonomics and transcriptomics approach to understanding metabolic pathway disturbance induced by perfluorooctanoic acid. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2013. [CrossRef]

- Yu N, Wei S, Li M, Yang J, Li K, Jin L, Xie Y, Giesy JP, Zhang X, Yu H Effects of Perfluorooctanoic Acid on Metabolic Profiles in Brain and Liver of Mouse Revealed by a High-throughput Targeted Metabolomics Approach. Sci Rep 2016. [CrossRef]

- Adams SH, Hoppel CL, Lok KH, Zhao L, Wong SW, Minkler PE, Hwang DH, Newman JW, Garvey WT Plasma acylcarnitine profiles suggest incomplete long-chain fatty acid β-oxidation and altered tricarboxylic acid cycle activity in type 2 diabetic African-American women. Journal of Nutrition 2009. [CrossRef]

- Labine LM, Simpson MJ The use of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and mass spectrometry (MS)–based metabolomics in environmental exposure assessment. Curr Opin Environ Sci Health 2020. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).