Submitted:

05 June 2025

Posted:

06 June 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- RQ1

- What is the state of diffusion of electronic voting worldwide?

- RQ2

- What are the determinants of electronic voting adoption?

- to provide an in-depth examination of electronic voting technologies in various countries, describing the existing systems, their successes, challenges, and evolution globally;

- to provide insights into the current landscape of electronic voting technologies and identify obstacles to their adoption;

- to analyse the relevance of socio-economic indicators as determinants of electronic voting adoption.

2. Related Literature

- Ballot casting, when technology is introduced for casting the vote through voting machines;

- Tabulation, when machines are used in the counting process;

- Transmission, when voting operations are conducted traditionally but the results of polling stations are sent via the Internet to the central tallying location.

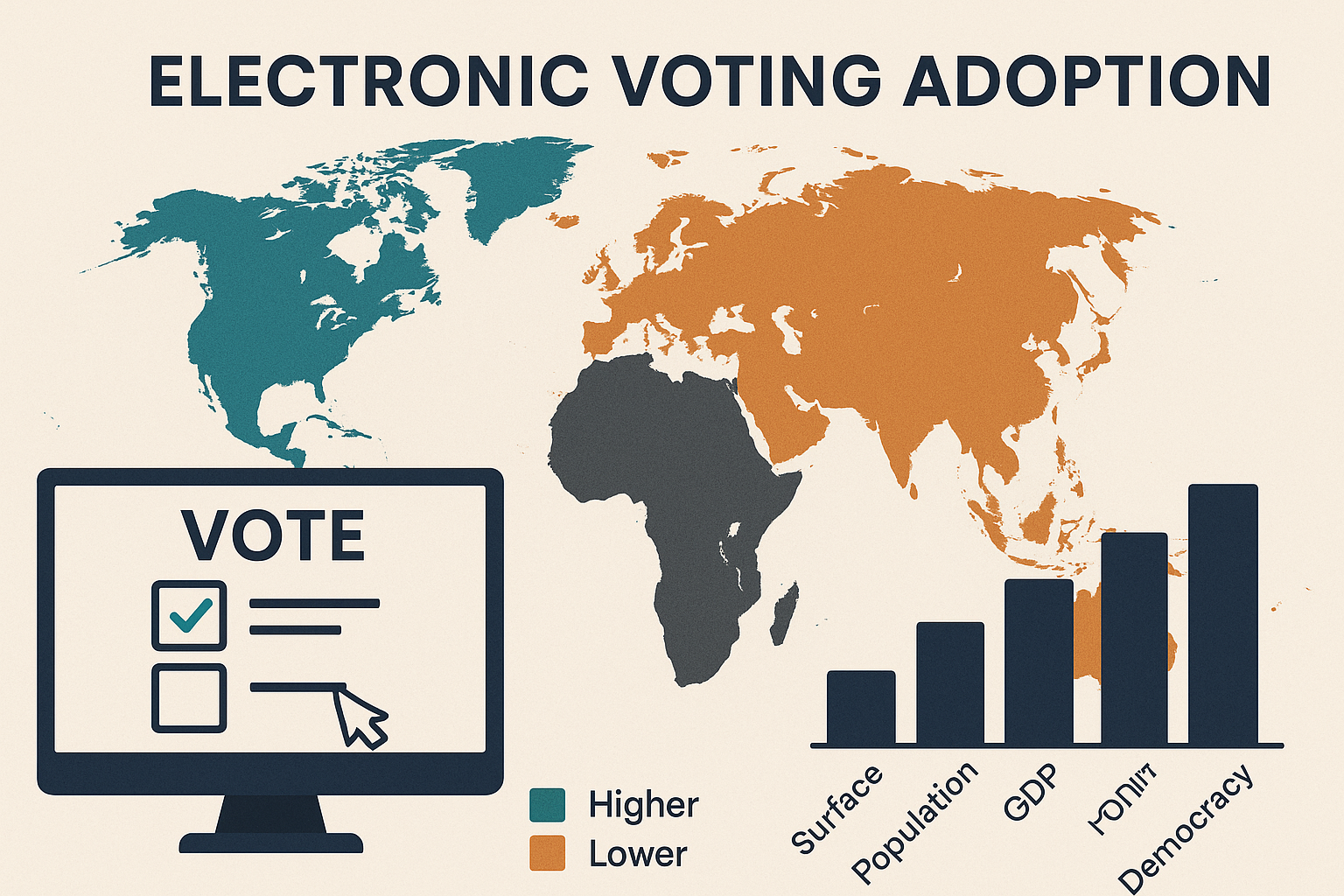

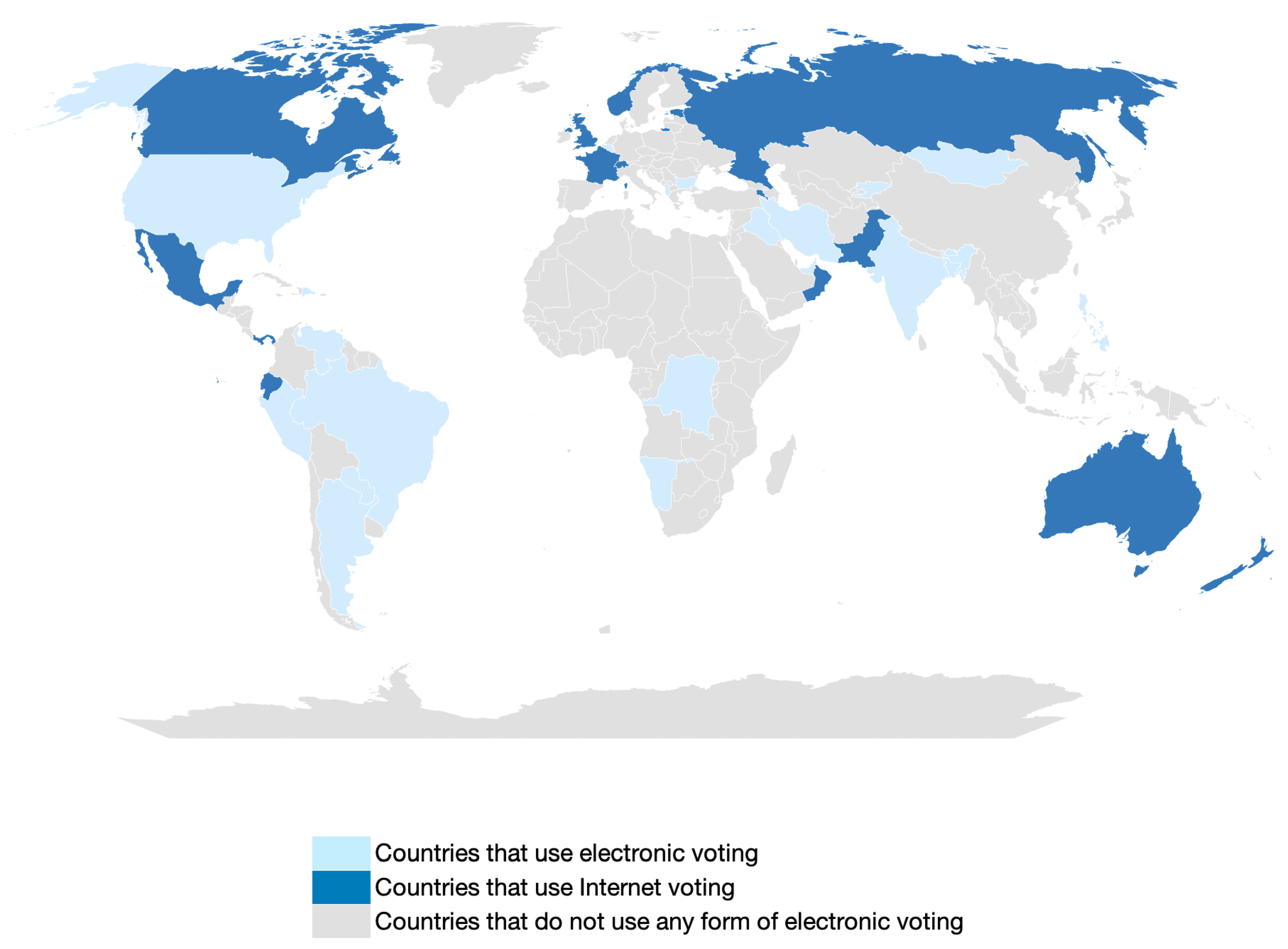

3. Worldwide Adoption of e-Voting and i-Voting

3.1. Overall View

3.2. E-Voting Adoption

3.2.1. North and Central America

3.2.2. South America

3.2.3. Europe

3.2.4. Africa

3.2.5. Asia

3.3. I-Voting Adoption for Special Classes of Citizens

3.3.1. North America

3.3.2. South America

3.3.3. Europe

3.3.4. Asia

3.3.5. Oceania

3.4. I-Voting Adoption for All Citizens

3.4.1. North America

3.4.2. Europe

3.4.3. Asia

3.5. E-Voting Abandonment

3.5.1. South America

3.5.2. Europe

3.5.3. Asia

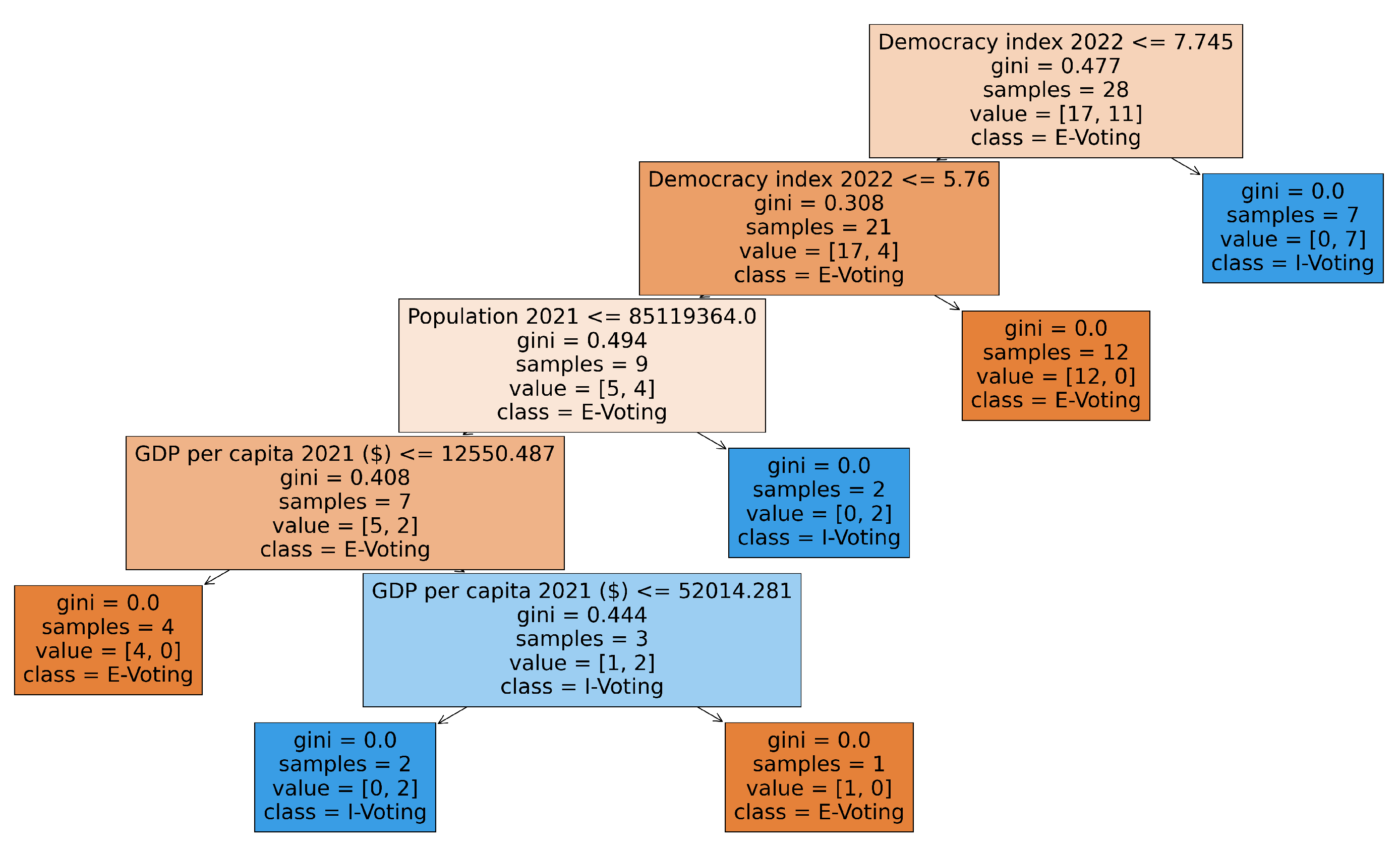

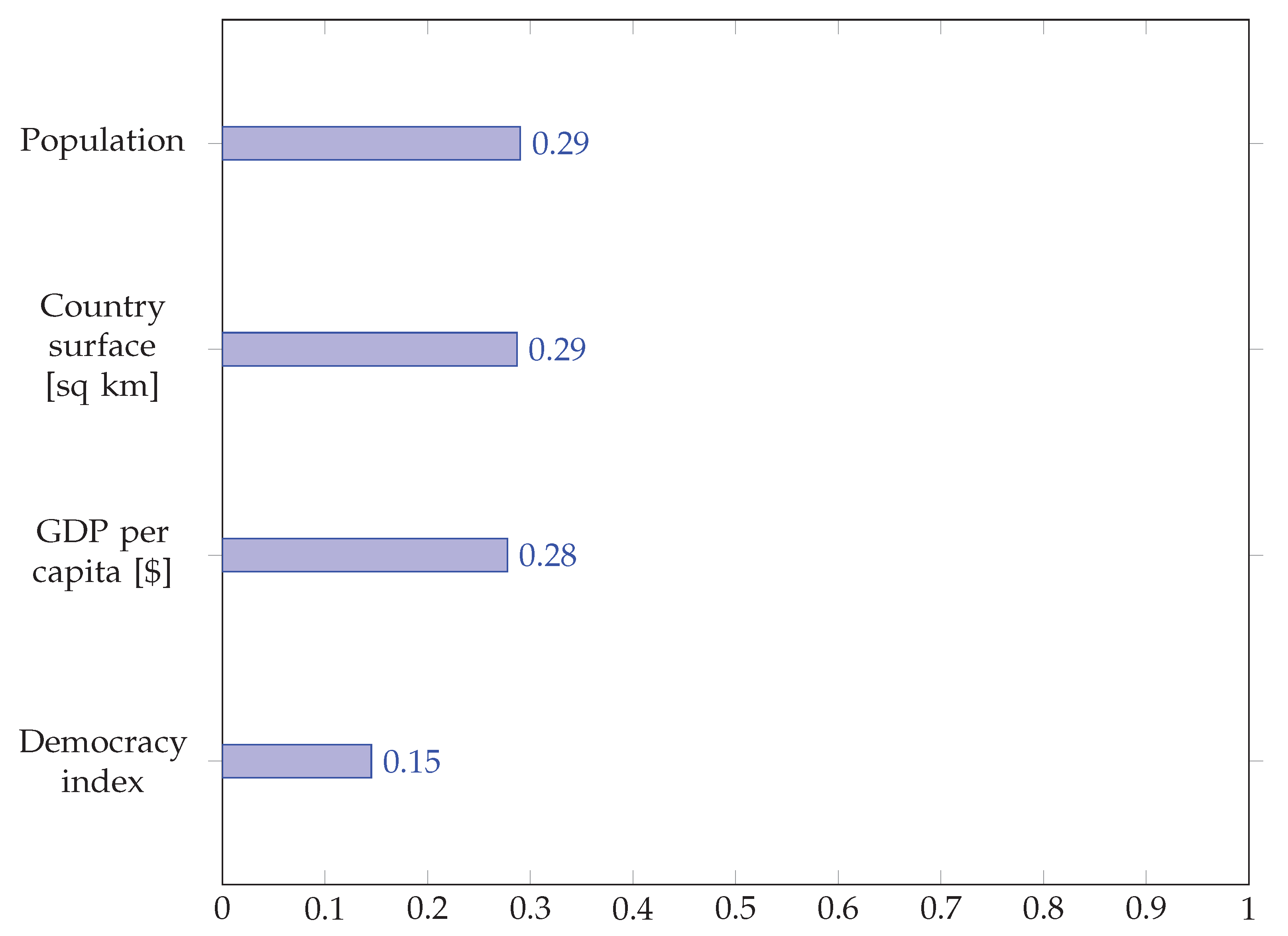

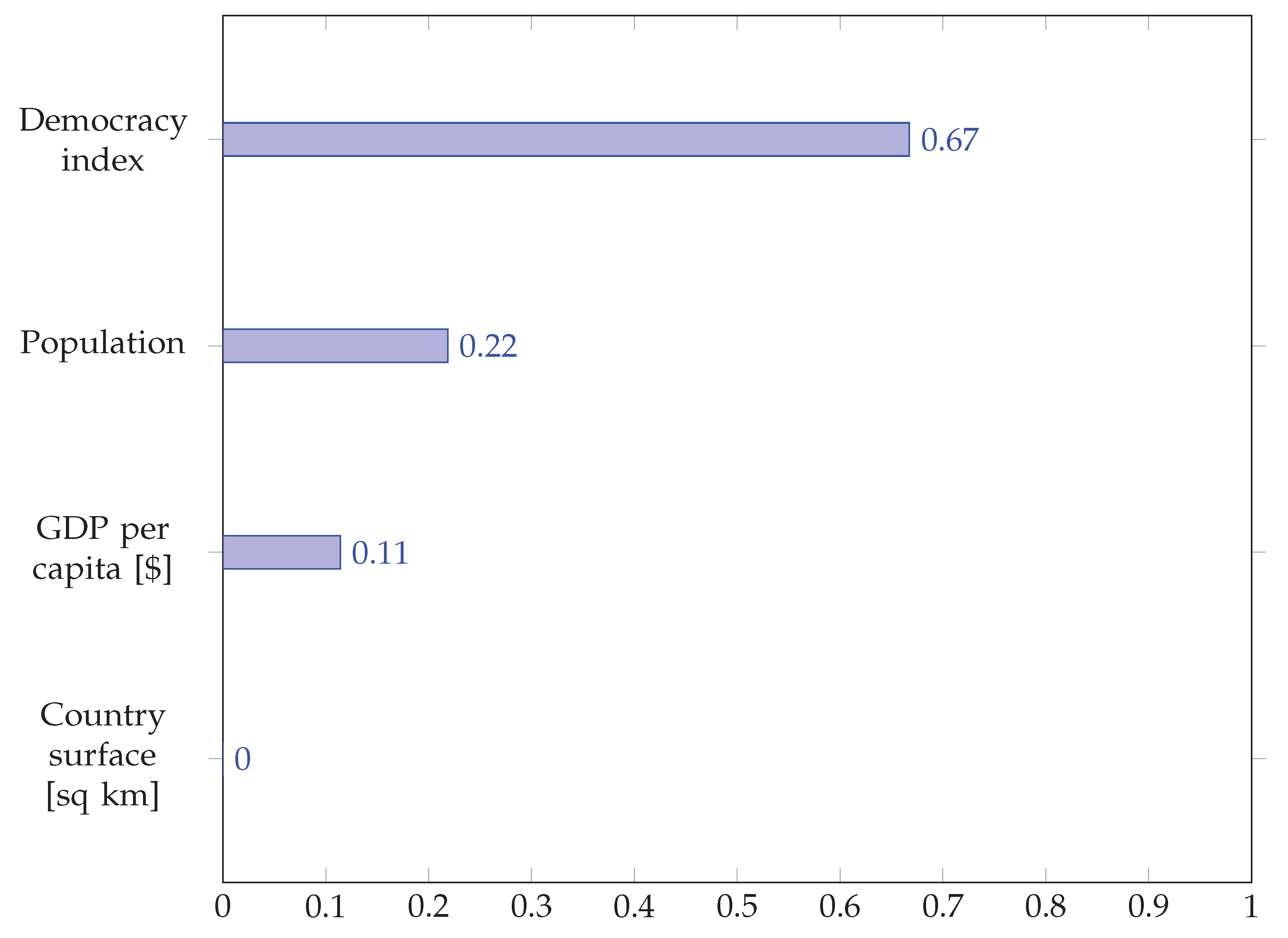

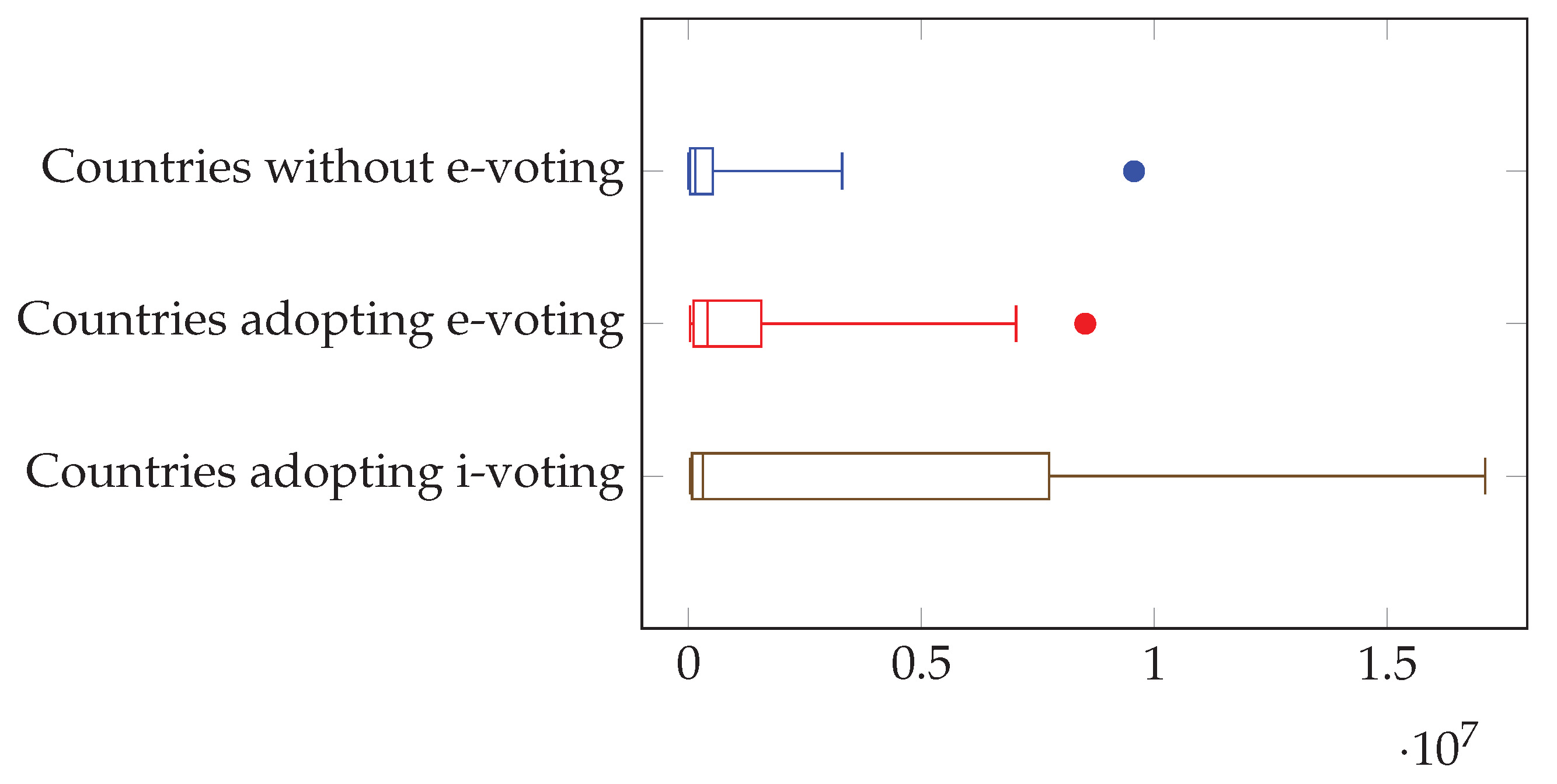

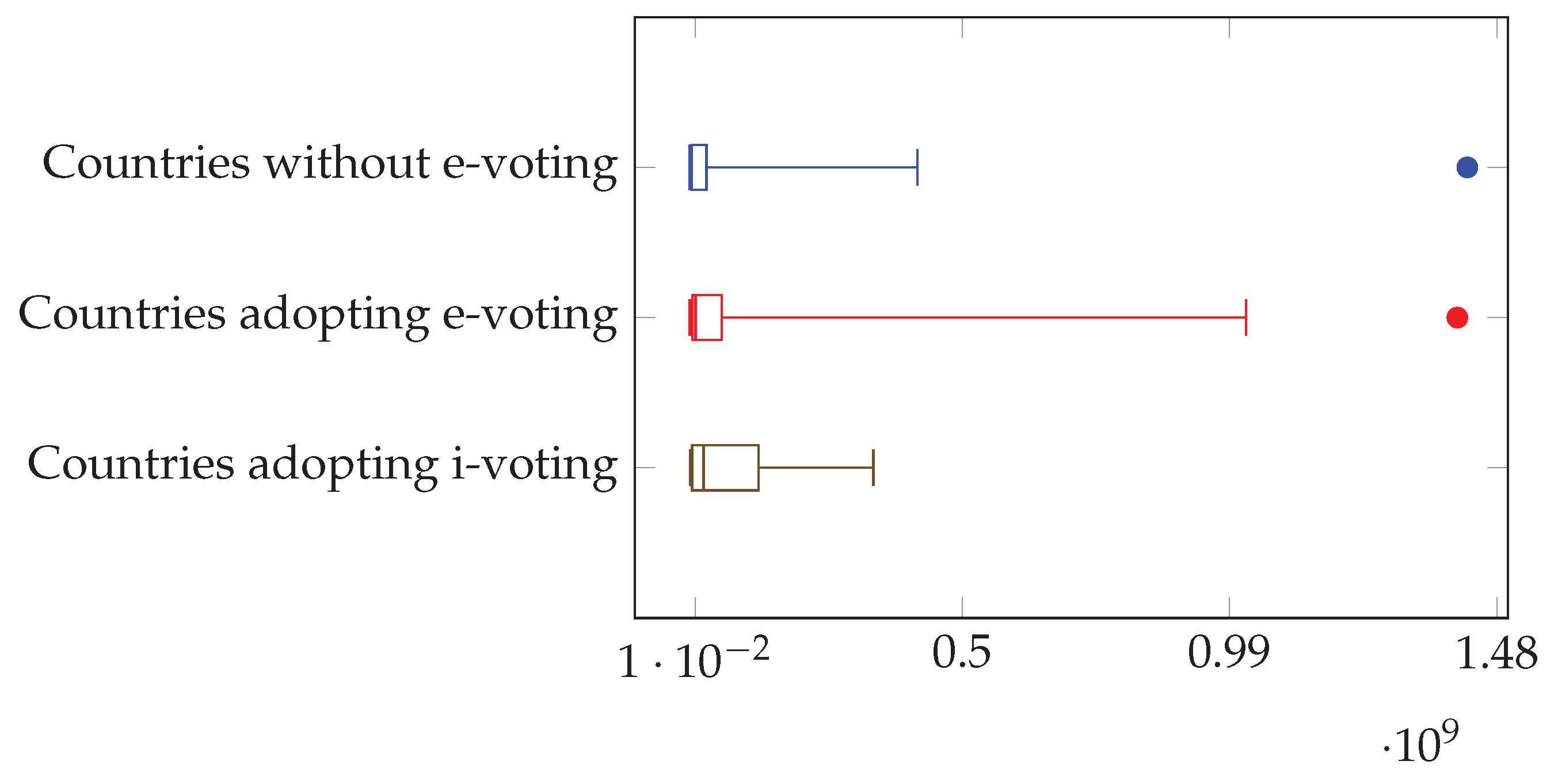

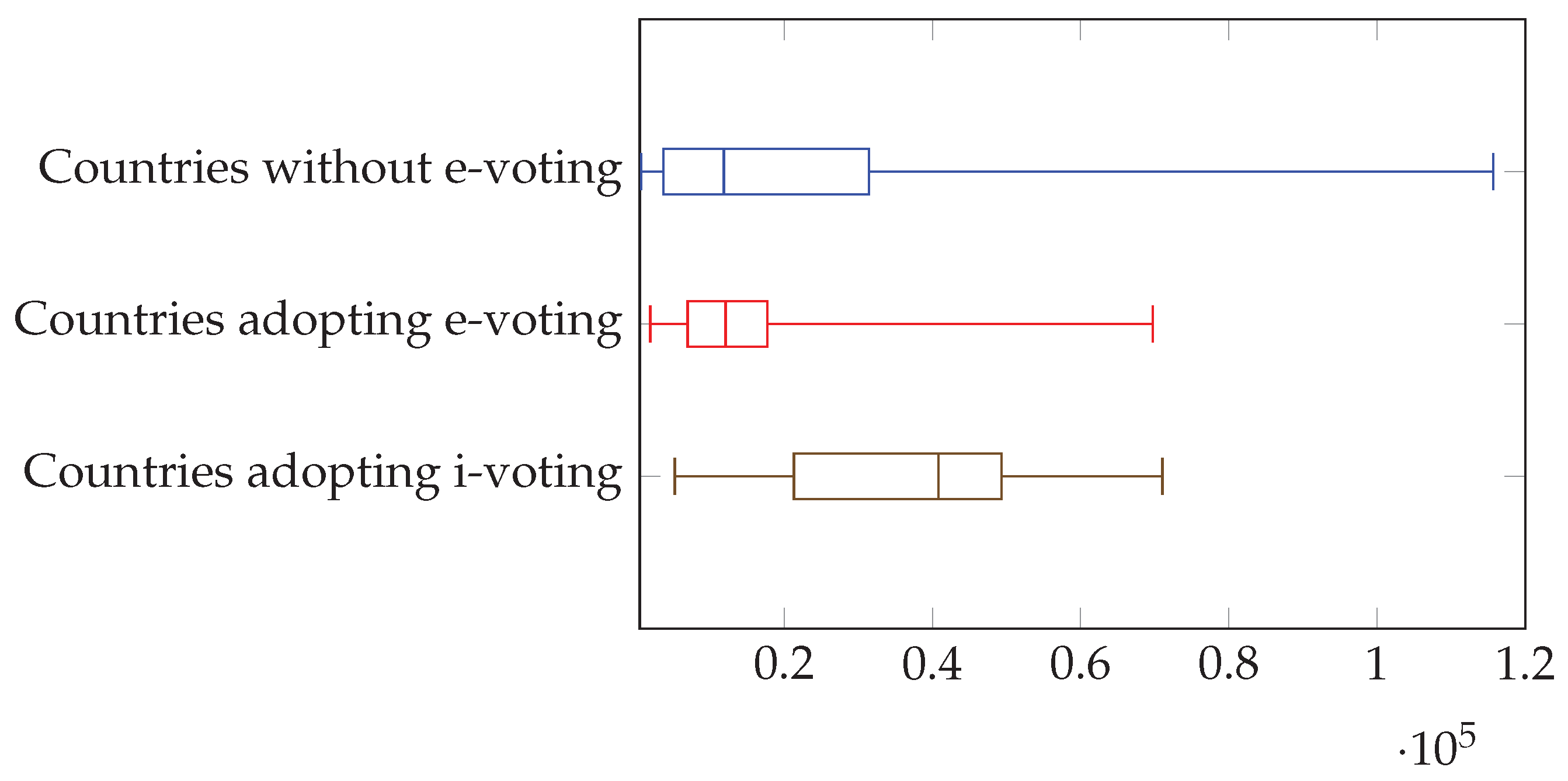

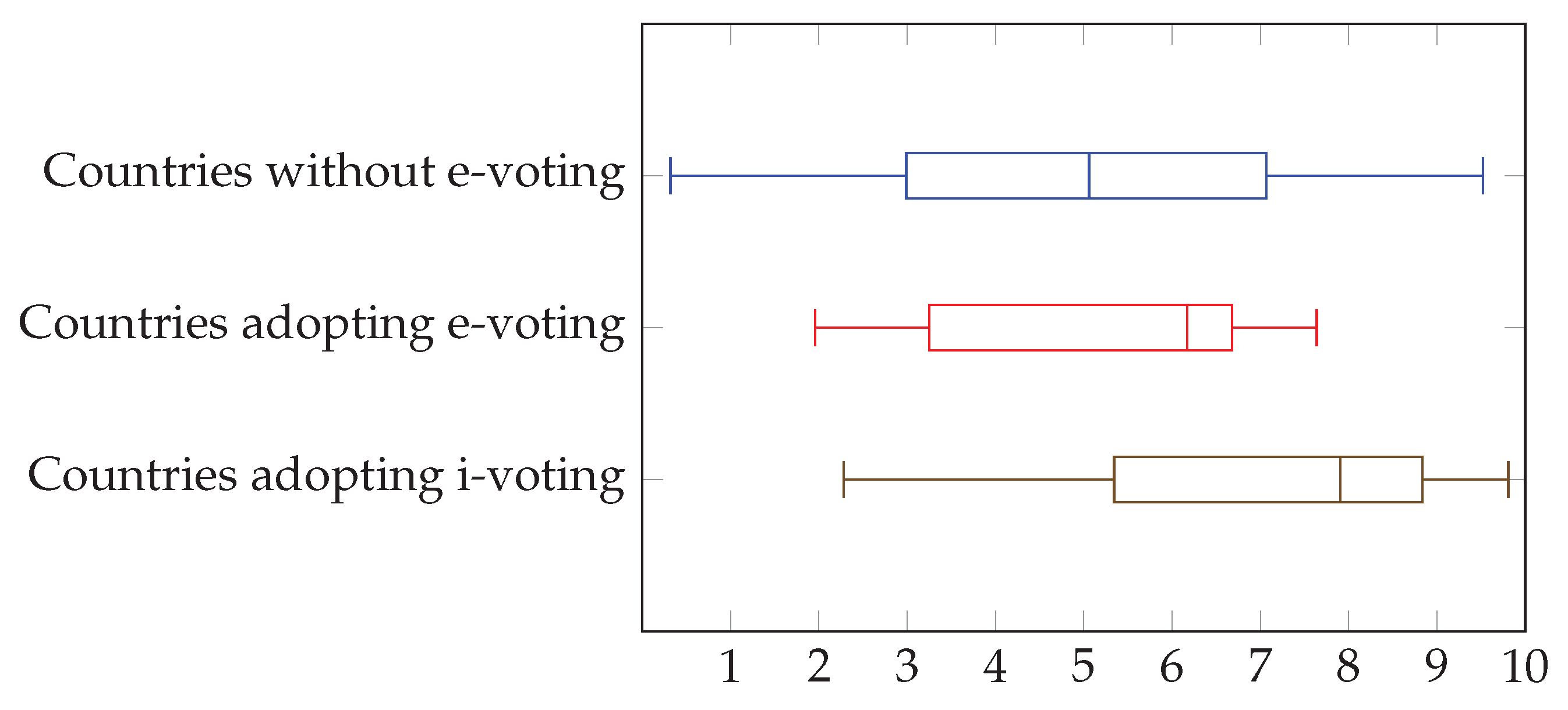

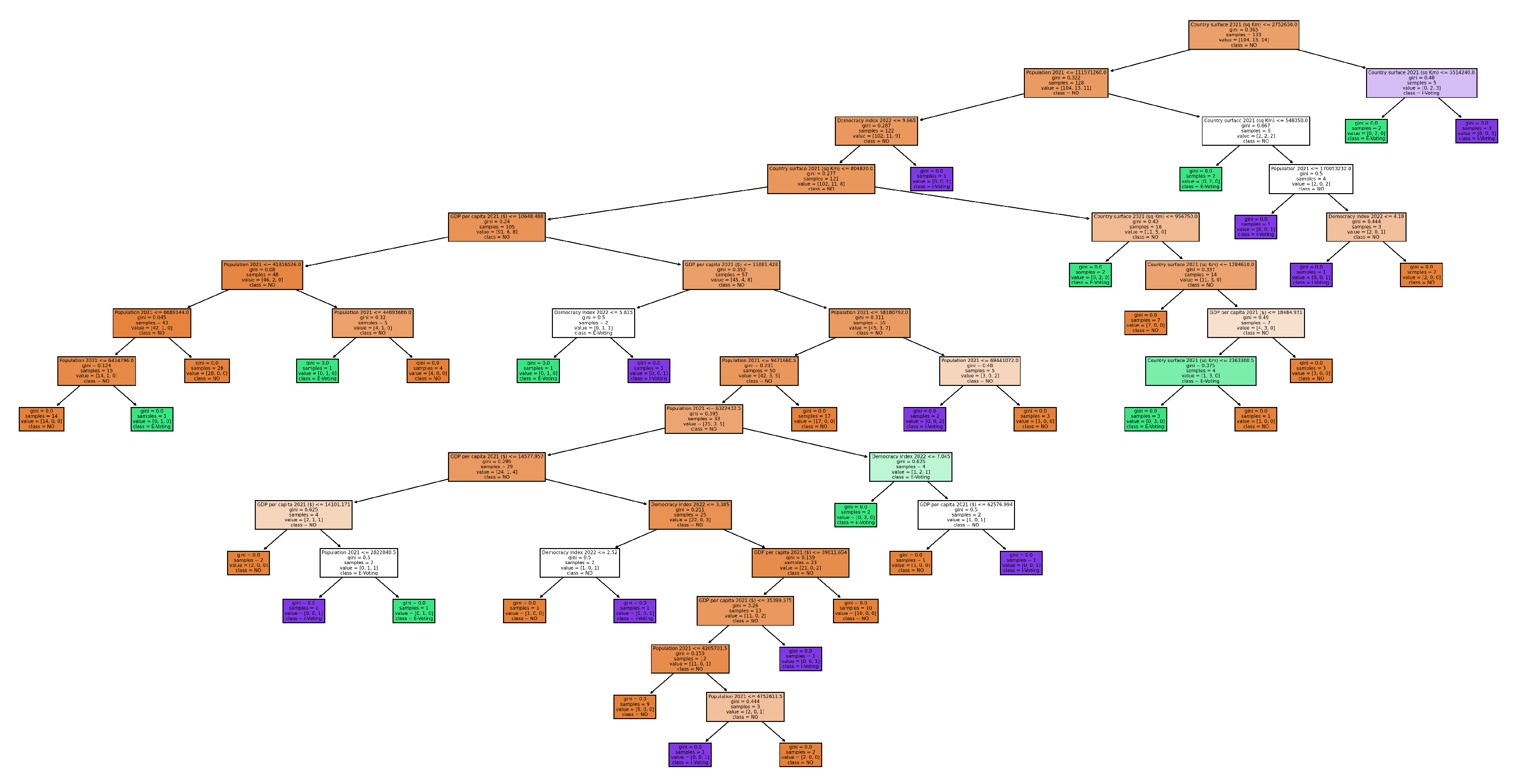

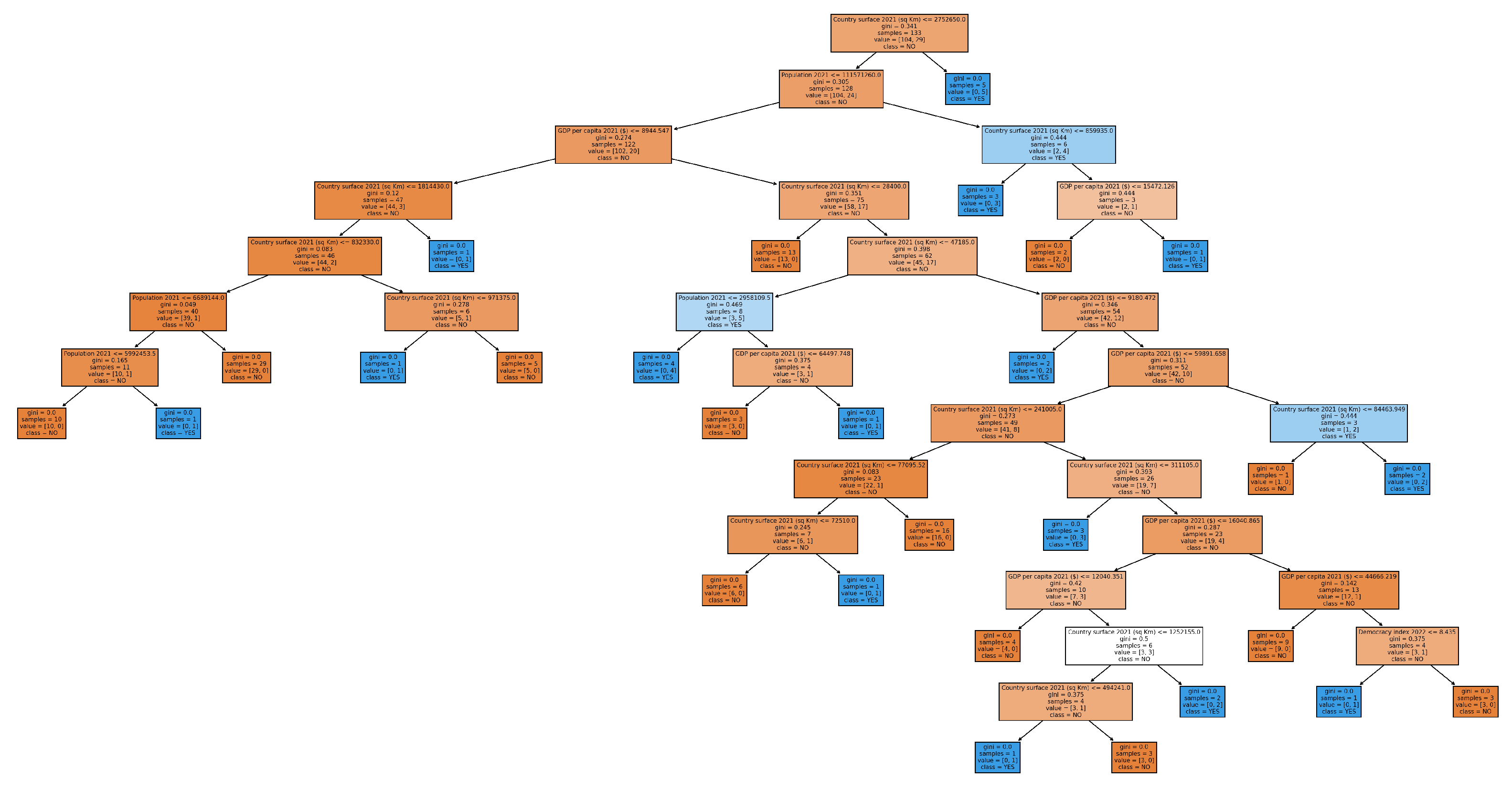

4. Determinants of Electronic Voting Adoption

- Surface;

- Population;

- Gross Domestic Product (GDP);

- Democracy Index.

- a three-class classifier;

- a cascade of two-class classifiers.

5. Conclusions

References

- Challú, C.; Seira, E.; Simpser, A. The Quality of Vote Tallies: Causes and Consequences. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 2020, 114, 1071–1085. [CrossRef]

- Goggin, S.N.; Byrne, M.D.; Gilbert, J.E. Post-Election Auditing: Effects of Procedure and Ballot Type on Manual Counting Accuracy, Efficiency, and Auditor Satisfaction and Confidence. Election Law Journal: Rules, Politics, and Policy 2012, 11, 36–51. [CrossRef]

- Willemson, J.; Krips, K. Estimating Carbon Footprint of Paper and Internet Voting. In Proceedings of the Electronic Voting. Springer Nature Switzerland, 2023, pp. 140–155.

- Schur, L.; Adya, M.; Ameri, M. Accessible Democracy: Reducing Voting Obstacles for People with Disabilities. Election Law Journal: Rules, Politics, and Policy 2015, 14, 60–65. [CrossRef]

- Valsamidis, S.; Nerantzis, V.; Kerenidou, E.; Karakos, A. Survey on e-voting and electoral technology for Balkan and South-Eastern Europe countries. The Economies of Balkan and Eastern Europe Countries in the changed world 2010, p. 176.

- Krimmer, R.; Triessnig, S.; Volkamer, M. The Development of Remote E-Voting Around the World: A Review of Roads and Directions. In Proceedings of the E-Voting and Identity. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2007, pp. 1–15.

- Wang, K.H.K.; Mondal, S.K.; Chan, K.C.; Xie, X. A Review of Contemporary E-voting: Requirements, Technology, Systems and Usability. Data Science and Pattern Recognition 2017, 1, 31.

- Kumar, M.S.; Walia, E. Analysis of electronic voting system in various countries. International Journal on Computer Science 2011.

- Hao, F.; Ryan, P.Y.A. Real-World Electronic Voting: Design, Analysis and Deployment; CRC Press, 2016.

- Gibson, J.P.; Krimmer, R.; Teague, V.; Pomares, J. A review of e-voting: the past, present and future. Annals of Telecommunications 2016, 71, 279–286.

- Ikrissi, G.; Mazri, T. Electronic Voting: Review and Challenges. In Proceedings of the Innovations in Smart Cities Applications Volume 7. Springer Nature Switzerland, 2024, pp. 110–119.

- Adekunle, S.E.; Others. A Review of Electronic Voting Systems: Strategy for a Novel. International Journal of Information Engineering & Electronic Business 2020, 12.

- Lake, J. What are the risks of electronic voting and internet voting? https://www.comparitech.com/blog/information-security/electronic-voting-risks/, 2022. Accessed: 2024-04-17.

- Kumar, D.A.; Begum, T.U.S. Electronic voting machine—A review. In Proceedings of the International conference on pattern recognition, informatics and medical engineering (PRIME-2012). IEEE, 2012, pp. 41–48.

- Shejavali, N. Electronic Voting Machines. Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR) No 2014, 1.

- Everett, S.P.; Greene, K.K.; Byrne, M.D.; Wallach, D.S.; Derr, K.; Sandler, D.; Torous, T. Electronic voting machines versus traditional methods: Improved preference, similar performance. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems, 2008, pp. 883–892.

- Everett, S.P. The usability of electronic voting machines and how votes can be changed without detection. PhD thesis, Citeseer, 2007.

- Wolchok, S.; Wustrow, E.; Halderman, J.A.; Prasad, H.K.; Kankipati, A.; Sakhamuri, S.K.; Yagati, V.; Gonggrijp, R. Security analysis of India’s electronic voting machines. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 17th ACM conference on Computer and communications security, 2010, pp. 1–14.

- Kiayias, A.; Michel, L.; Russell, A.; Shashidhar, N.; See, A.; Shvartsman, A.; Davtyan, S. Tampering with Special Purpose Trusted Computing Devices: A Case Study in Optical Scan E-Voting. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Third Annual Computer Security Applications Conference (ACSAC 2007). IEEE, 2007, pp. 30–39.

- Abuidris, Y.O.; Kumar, R.; Wenyong, W. A Survey of Blockchain Based on E-voting Systems. In Proceedings of the ICBTA 2019: 2019 2nd International Conference on Blockchain Technology and Applications, 2019, pp. 99–104.

- Vladucu, M.V.; Dong, Z.; Medina, J.; Rojas-Cessa, R. E-Voting Meets Blockchain: A Survey. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 23293–23308. [CrossRef]

- Ullits, J. Deciphering blockchain’s role in Danish decision-making: evaluating opportunities and challenges through the prism of due process. Law Innov. Technol. 2024, pp. 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Al-Maaitah, S.; Qatawneh, M.; Quzmar, A. E-Voting System Based on Blockchain Technology: A Survey. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Information Technology (ICIT). IEEE, 2021, pp. 200–205.

- del Blanco, D.Y.M.; Gascó, M. A Protocolized, Comparative Study of Helios Voting and Scytl/iVote. In Proceedings of the 2019 Sixth International Conference on eDemocracy & eGovernment (ICEDEG). IEEE, 2019, pp. 31–38.

- New Zealand Electoral Commission. How to vote from overseas. https://web.archive.org/web/20231211001803/https://www.vote.nz/voting/overseas/vote-from-overseas/, 2023. Accessed: 2023-12-11.

- Ministry of Transport, Communications and Information Technology. Antakhib App. https://oman.om/en/home-top-level/eparticipation/e-voting, 2023. Accessed: 2024-4-14.

- Ministry of State for FNC Affairs. United Arab Emirates e-voting app download page. https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.uaevoting.ae, 2023. Accessed: 2024-4-14.

- International IDEA. ICTs in Elections Database. https://www.idea.int/data-tools/data/icts-elections-database, 2024. Accessed: 2024-4-14.

- McCombie, S.; Uhlmann, A.J.; Morrison, S. The US 2016 presidential election & Russia’s troll farms. Intell. Natl. Sec. 2020, 35, 95–114. [CrossRef]

- Burr, R.; Warner, M.; Collins, S.; Heinrich, M.; Lankford, J. Senate Intel committee releases unclassied 1st installment in Russia report, updated recommendations on election security. https://www.justsecurity.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/5.8.18-Statement-on-SSCI-Report.pdf, 2018. Accessed: 2024-4-14.

- Zdun, M. Machine Politics: How America casts and counts its votes. Reuters 2022.

- King, B.A. State online voting and registration lookup tools: Participation, confidence, and ballot disposition. Journal of Information Technology & Politics 2019, 16, 219–235. [CrossRef]

- Fox-Sowell, S.; Quinlan, K. Election day ends with reports of vote counting tech challenges, text scams in several states. http://statescoop.com/election-day-ends-with-reports-of-vote-counting-tech-challenges-text-scams-in-several-states/, 2024. Accessed: 2025-1-6.

- Alcántara, M.J.A. Dominican government asks OAS to investigate e-vote failure. https://apnews.com/international-news-general-news-293e335b22b24fa6bd5945733b2a27a8, 2020. Accessed: 2023-12-9.

- Pomares, J.; Levin, I.; Alvarez, R.M. Do voters and poll workers differ in their attitudes toward e-voting? Evidence from the first e-election in Salta, Argentina. In Proceedings of the 2014 Electronic Voting Technology Workshop/Workshop on Trustworthy Elections (EVT/WOTE 14), 2014.

- “Evoting Communications”. What happened to electronic voting in Argentina’s primary elections? https://evoting.com/en/2023/08/21/voto-electronico-primarias-argentina/, 2023. Accessed: 2023-11-30.

- Okuro, O. Comparative Review of E-Voting in India and Brazil: Key Lessons for Kenya. Lagos Hist. Rev. 2023.

- Krimmer, R.; Volkamer, M.; Binder, N.B.; Kersting, N.; Loeber, L. TUT Press Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Electronic Voting (E-Vote-ID) 2017.

- Spada, P.; Mellon, J.; Peixoto, T.; Sjoberg, F.M. Effects of the internet on participation: Study of a public policy referendum in Brazil. Journal of Information Technology & Politics 2016, 13, 187–207. [CrossRef]

- Claudio Fuentes Armadans, J.S.C. History of electronic voting in Paraguay. Technical report, TEDIC (Asociación de Tecnología, Educación, Desarrollo, Investigación, Comunicación), 2022.

- Machin-Mastromatteo, J.D. The most “perfect” voting system in the world. Information Development 2016, 32, 751–755.

- Këlliçi, E. Increasing public trust through technology, eVoting case Albania. https://uet.edu.al/ingenious/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/ingenious-2-Increasing-public-trust-through-technology-eVoting-case-Albania.pdf, 2023. Accessed: 2023-11-15.

- Dandoy, R. An Analysis of Electronic Voting in Belgium: Do voters behave differently when facing a machine? In Belgian Exceptionalism; Routledge, 2021; pp. 44–58.

- Wetherall-Grujić, G. Manufacturing Distrust: Voting Machines in Bulgaria. https://democracy-technologies.org/voting/manufacturing-distrust-voting-machines-in-bulgaria/, 2022. Accessed: 2023-8-29.

- Bg, M.W.H. A System for remote Electronic Voting is being developed in Bulgaria. https://www.novinite.com/articles/214773/A+System+for+remote+Electronic+Voting+is+being+developed+in+Bulgaria, 2022. Accessed: 2023-12-1.

- Freyer, U. Introduction of Electronic Voting In Namibia. Technical report, Electoral Commission of Namibia, 2017.

- Mpekoa, N.; van Greunen, D. E-voting experiences: A case of Namibia and Estonia. In Proceedings of the 2017 IST-Africa Week Conference (IST-Africa), 2017, pp. 1–8.

- Giles, C. DR Congo elections: Why do voters mistrust electronic voting? BBC 2018.

- Congo Research Group. The electronic voting controversy in the Congo. Congo Research Group Election Brief No 1, 2018.

- The Sentry Team. Electronic Voting Technology DRC. https://thesentry.org/reports/electronic-voting-technology-drc/, 2018. Accessed: 2024-2-22.

- Election Commission of Bhutan. Handbook for Polling Officiers, 2013.

- Election Commission of Bhutan. Electronic Voting Machine (EVM) Rules and Regulations of the Kingdom of Bhutan, 2018, 2018.

- Risnanto, S.; Rahim, Y.B.A.; Herman, N.S. Success Implementation of E-Voting Technology In various Countries: A Review. foitic 2020, pp. 150–155.

- Tasnim News Agency. E-Voting In Iran Presidential Election Off The Table. Eurasia Review 2021.

- National Democratic Institute – Washington DC. Iran’s June 18, 2021 Elections. Technical report, National Democratic Institute, 2021.

- United Nations Assistance Mission for Iraq (UNAMI). Elections for Iraq’s Council of Representatives - Facts sheet. Technical report, United Nations, 2021.

- Rasheed, A.; Jalabi, R.; Aboulenein, A. Exclusive: Iraq election commission ignored warnings over voting machines - document. Reuters 2018.

- Sheranova, A. Cheating the machine: E-voting practices in Kyrgyzstan’s local elections. Eur. Rev. 2020, 28, 793–809. [CrossRef]

- Umarova, A. Why Kyrgyzstan uses biometrics in its voting system. https://govinsider.asia/intl-en/article/kyrgyzstan-uses-biometrics-voting-system, 2018. Accessed: 2023-12-10.

- OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights. Mongolia - Parliamentary Elections, ODIHR needs assessment mission report. Technical report, 2020.

- Gangabaatar, D. Electoral Reform and the Electronic Voting System: Case of Mongolia. In Digital Transformation and Its Role in Progressing the Relationship Between States and Their Citizens; IGI Global, 2020; pp. 182–204.

- Elven, T.M.A.; Al-Muqorrobin, S.A. Consolidating Indonesia’s Fragile Elections Through E-Voting: Lessons Learned from India and the Philippines. Indonesian Comparative Law Review 2020, 3, 63–80. [CrossRef]

- “International Foundation for Electoral Systems”. Elections in Panama - 2019 General Elections - Frequently Asked Questions. Technical report, IFES - International Foundation for Electoral Systems, 2019.

- Associated Press. Ecuadorians Vote for President, Overseas Voting System Sees Cyberattacks. https://www.voanews.com/a/ecuadorians-vote-for-president-overseas-voting-system-sees-cyberattacks/7233360.html, 2023. Accessed: 2023-12-11.

- Finn, V.; Besserer Rayas, A. Turning rights into ballots: Mexican external voting from the US. Territory, Politics, Governance 2022, pp. 1–20.

- INE.. Electronic Voting System for Mexican Residing Abroad Manual. Instituto Nacional Electoral, 2022.

- “Ministère de l’Europe et des Affaires ètrangères”. Legislative Elections – Opening of the Internet voting portal (27 May 2022). https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/the-ministry-and-its-network/news/2022/article/legislative-elections-opening-of-the-internet-voting-portal-27-may-2022, 2022. Accessed: 2023-11-12.

- Xenakis, A.; Macintosh, A. Major Issues in Electronic Voting in the Context of the UK Pilots. Journal of Information Technology & Politics 2004, 1, 53–74. [CrossRef]

- Storer, T.; Duncan, I. Polsterless Remote Electronic Voting. Journal of Information Technology & Politics 2004, 1, 75–103.

- UK Parliament staff. Online voting in the House of Lords. https://www.parliament.uk/about/how/changes-to-lords-proceedings/online-voting-in-the-house-of-lords/, 2022. Accessed: 2023-12-12.

- Manougian, H. Did You Know Armenia Allows Internet Voting? (But It’s Only For Some). https://evnreport.com/politics/did-you-know-armenia-allows-internet-voting-but-it-s-only-for-some/, 2020. Accessed: 2023-11-15.

- Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR). Republic of Armenia Early Parliamentary Elections 20 June 2021. Technical report, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2021.

- Goldsmith, L.; Shaikh, A.K.; Tan, H.Y.; Raahemifar, K. A Review of Contemporary Governance Challenges in Oman: Can Blockchain Technology Be Part of Sustainable Solutions? Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2022, 14, 11819. [CrossRef]

- OECD. Open Government case study - Sample Case Submission Form. https://opengov.unescwa.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/Om02-e-Voting-System-En.pdf, 2019. Accessed: 2023-11-12.

- Mc Keown, D. New South Wales state election 2015. Research Paper Series (Parliamentary Library, Australia) 2016.

- Cardillo, A.; Akinyokun, N.; Essex, A. Online Voting in Ontario Municipal Elections: A Conflict of Legal Principles and Technology? In Proceedings of the Electronic Voting. Springer International Publishing, 2019, pp. 67–82.

- Chughtai, W. Online voting is growing in Canada, raising calls for clear standards. CBC News 2022.

- Górny, M. I-voting – opportunities and threats. Conditions for the effective implementation of Internet voting on the example of Switzerland and Estonia. Prz. Politol. 2021, pp. 133–146. [CrossRef]

- Scytl. 94% trust rate in Norway’s online voting channel. https://scytl.com/94-trust-rate-in-norways-online-voting-channel/, 2014. Accessed: 2024-1-7.

- Cortier, V.; Wiedling, C. A Formal Analysis of the Norwegian E-voting Protocol. In Proceedings of the Principles of Security and Trust. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2012, pp. 109–128.

- Chowdhury, M.J.M. Comparison of e-voting schemes: Estonian and Norwegian solutions. International Journal of Applied Information Systems 2013, 6, 60–66.

- Smartmatic. Norwegian county conducts referendum using online voting. https://www.smartmatic.com/media/norwegian-county-conducts-referendum-using-online-voting/, 2022. Accessed: 2024-1-7.

- Reiners, M. Vote electronique in Switzerland: Comparison of relevant pilot projects. J. Commonw. Comp. Polit. 2020, 13, 58–75.

- Swiss Federal Chancellery FCh. E-Voting. https://www.bk.admin.ch/bk/en/home/politische-rechte/e-voting.html, 2023. Accessed: 2023-12-26.

- Ridard, E.; Eichenberger, M. Swiss Abroad: e-voting doesn’t make up for frustrations. https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/politics/swiss-abroad–e-voting-does-not-make-up-for-frustrations/48920054, 2023. Accessed: 2023-12-26.

- Al-Khouri, A.M.; Authority, E.I.; Dhabi, A. E-Voting in UAE FNC Elections: A Case Study. In Proceedings of the Information and Knowledge Management. academia.edu, 2012, Vol. 2, pp. 25–84.

- The United Arab Emirates’ Government portal. Elections. https://u.ae/en/about-the-uae/the-uae-government/the-federal-national-council-/elections-, 2023. Accessed: 2023-12-10.

- Scytl. United Arab Emirates Becomes First Country to Hold Fully Digital Elections with Scytl. https://scytl.com/united-arab-emirates-becomes-first-country-to-hold-fully-digital-elections-with-scytl/, 2023. Accessed: 2023-12-10.

- Vakarjuk, J.; Snetkov, N.; Willemson, J. Russian Federal Remote E-voting Scheme of 2021 – Protocol Description and Analysis. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2022 European Interdisciplinary Cybersecurity Conference, New York, NY, USA, 2022; EICC ’22, pp. 29–35.

- Chingaev, Y. Russia’s Online Voting System Briefly Crashes on First Day of Election. https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2024/03/15/russias-online-voting-system-briefly-crashes-on-first-day-of-election-a84470, 2024. Accessed: 2024-3-27.

- Dyxon, R. As Russian voting moves online, Putin’s foes say another path to curb Kremlin is lost. The Washington Post 2021.

- Alvarez, R.M.; Katz, G.; Llamosa, R.; Martinez, H.E. Assessing Voters’ Attitudes towards Electronic Voting in Latin America: Evidence from Colombia’s 2007 E-Voting Pilot. In Proceedings of the E-Voting and Identity. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2009, pp. 75–91.

- Alvarez, R.M.; Katz, G.; Pomares, J. The Impact of New Technologies on Voter Confidence in Latin America: Evidence from E-Voting Experiments in Argentina and Colombia. Journal of Information Technology & Politics 2011, 8, 199–217. [CrossRef]

- Corvetto Salinas, P.A. Implementación del voto electrónico en Perú. Technical report, Oficina Nacional de Procesos Electorales (ONPE) - Perú, 2022.

- Scytl. Scytl Online Voting Helps Iceland Successfully Run Fully Online Referendums. https://scytl.com/news/scytl-online-voting-helps-iceland-successfully-run-fully-online-referendums/, 2015. Accessed: 2024-1-7.

- European Digital Rights. Ireland: E-voting machines go to scrap after proving unreliable. https://edri.org/our-work/edrigramnumber10-14evoting-machines-scrap-ireland/, 2012. Accessed: 2023-12-12.

- Post, I. Il pasticcio del voto elettronico in Lombardia. https://www.ilpost.it/2017/10/23/voto-elettronico-lombardia/, 2017. Accessed: 2022-8-21.

- Lombardia, R. Lombardia, Referendum: il sistema di voto elettronico. Technical report, 2017.

- Wikipedia. Referendum consultivo in Lombardia del 2017. https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Referendum_consultivo_in_Lombardia_del_2017, 2017. Accessed: 2022-8-21.

- Dipartimento per gli affari interni e territoriali. e-Vote. La simulazione del voto elettronico. https://dait.interno.gov.it/elezioni/notizie/e-vote-simulazione-del-voto-elettronico, 2023. Accessed: 2024-1-7.

- Irani, B. EC to buy 2,535 new EVMs at four times the cost of previous models. https://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/145403/ec-to-buy-2-535-new-evms-at-four-times-the-cost-of, 2018. Accessed: 2023-11-30.

- The Wire editorial staff. Bangladesh Election Commission Forced to Drop EVMs. https://thewire.in/south-asia/bangladesh-election-commission-drop-evms, 2023. Accessed: 2023-11-30.

- Mackisack, D. There and Back Again – The Story of Pakistan’s Brief Experiment with Electronic Voting. https://democracy-technologies.org/voting/there-and-back-again-the-story-of-pakistans-brief-experiment-with-electronic-voting/, 2022. Accessed: 2023-12-12.

- Billon, M.; Marco, R.; Lera-Lopez, F. Disparities in ICT adoption: A multidimensional approach to study the cross-country digital divide. Telecommunications Policy 2009, 33, 596–610. [CrossRef]

- Krimmer, R. The evolution of e-voting: why voting technology is used and how it affects democracy. Tallinn University of Technology Doctoral Theses Series I: Social Sciences 2012, 19.

- Economist Intelligence Unit. Democracy Index 2022. https://www.eiu.com/n/campaigns/democracy-index-2022/?utm_source=economist&utm_medium=daily_chart&utm_campaign=democracy-index-2022, 2023. Accessed: 2024-1-7.

- Yuan, Y.; Wu, L.; Zhang, X. Gini-impurity index analysis. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 2021, 16, 3154–3169.

- Thampi, A. Interpretable AI: Building explainable machine learning systems; Simon and Schuster, 2022.

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32.

| Category | Countries |

|---|---|

| Citizens residing abroad | Panama, Ecuador, Mexico, France, Sultanate of Oman, Australia, New Zealand |

| Diplomatic personnel and military | Armenia |

| Members of the House of Lords (during pandemics) | United Kingdom |

| People with disabilities | Australia |

| Reason | Countries |

|---|---|

| Lack of trust | Peru, Ireland |

| No follow-up after the pilot project | Colombia, Iceland, Italy |

| Supply problems | Bangladesh |

| Political decision | Pakistan |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).