The results of the Vector Autoregression (VAR) model provide valuable insights into the relationships between economic factors and electoral outcomes, as well as the interactions between economic variables and political dynamics. Each objective will be addressed in relation to the findings from the VAR model.

4.7.1. Assessing the Impact of Key Economic Factors on Electoral Outcomes in Ghana

The first objective aims to evaluate how key economic factors such as GDP growth, inflation, unemployment, and poverty rate influence electoral outcomes, particularly voter turnout, party vote share, and the incumbent re-election rate.

Voter Turnout and Economic Indicators: The results show that voter turnout is positively influenced by its own past values, indicating persistence in voter engagement. However, the economic factors such as GDP growth and inflation have less direct influence on voter turnout. Although GDP growth has a negative coefficient in its first lag (-0.208236), it is not statistically significant. This suggests that economic growth does not have a strong immediate impact on voter turnout, indicating that factors beyond short-term economic performance might drive voter behavior in Ghana.

Inflation also exhibits an insignificant relationship with voter turnout. The coefficients for inflation lags are negative but small, meaning inflation does not strongly deter voter turnout. This could indicate that inflation is not a primary concern for voters when deciding whether to participate in elections.

Party Vote Share and Economic Performance: Interestingly, party vote share is more influenced by its own lagged values rather than economic factors. The positive and significant coefficient of party vote share (-1) (1.412079) suggests that a party’s past performance strongly predicts its future success, implying electoral inertia or loyalty. Economic factors like GDP growth and inflation show limited influence on vote share, pointing to a possible disconnect between macroeconomic performance and voter support for political parties. This aligns with previous findings that, in Ghana, other considerations such as ethnic affiliations and political stability might overshadow economic conditions in determining vote outcomes.

Incumbent Re-Election Rate: The model shows that the incumbent re-election rate is significantly influenced by the party vote share and voter turnout, but economic indicators have weaker links to incumbency. GDP growth and inflation do not significantly impact incumbency rates, reflecting that voters may not strictly hold incumbents accountable for short-term economic fluctuations. However, the negative effect of unemployment and poverty rate suggests that economic hardship, reflected in these factors, could undermine incumbents’ chances of re-election.

The strong negative coefficient of incumbent re-election rate (-1) on voter turnout (-6.560056) indicates that higher previous success of the incumbent may lower current voter engagement, perhaps due to voter dissatisfaction or disengagement when the incumbent’s performance is perceived as unsatisfactory.

4.7.2. Evaluating the Interaction Between Economic Factors and Political Dynamics in Shaping Voter Preferences

The second objective focuses on how economic factors interact with political dynamics such as political stability, corruption control, and income inequality, and how these interactions shape voter preferences in Ghana.

Political Stability and Voter Behavior: The results reveal a significant positive relationship between political stability (-1) and voter turnout (11.22054, t-statistic = 1.97264). This suggests that when the political environment is stable, voters are more likely to participate in elections. Political stability may reduce voter anxiety and increase confidence in the electoral process, encouraging higher turnout. In contrast, when political stability is weak, voter engagement tends to decline, possibly due to concerns over safety or the legitimacy of the electoral process. The interaction between political stability and voter turnout is critical in shaping electoral outcomes in Ghana, particularly in elections characterized by intense political competition.

Income Inequality and Electoral Dynamics: Income inequality, as measured by the Gini coefficient, does not have a strong direct influence on voter turnout or vote share in this model, suggesting that while inequality might be a background condition, it does not directly translate into voter behavior or party performance in Ghana. However, its interaction with other political and economic variables is worth noting. For instance, higher income inequality may contribute to dissatisfaction with governance but may not necessarily influence voting behavior in predictable ways. It is possible that income inequality plays a more nuanced role in shaping long-term political preferences rather than short-term electoral outcomes.

Corruption Control and Electoral Preferences: Corruption control shows a mixed relationship with electoral outcomes. While corruption control (-1) has a negative effect on party vote share (-4.880410, t-statistic = -1.83150), indicating that better corruption control could reduce a party’s vote share, this finding is counterintuitive. One potential interpretation is that corruption control measures disrupt traditional networks of patronage, which may have been used by parties to secure electoral support, leading to lower vote shares for parties that previously relied on these mechanisms. This could reflect a transformation in voter expectations, where voters prioritize transparency and accountability over party loyalty.

However, the positive coefficient of corruption control (-1) on voter turnout, although not significant, suggests that efforts to reduce corruption could increase voter engagement, as voters may feel more confident in the fairness of the electoral process. This relationship highlights the importance of institutional reforms and governance in shaping electoral dynamics.

In summary, the findings show that in Ghana, voter turnout and election results are influenced by both political and economic factors, but political stability and party loyalty play bigger roles than the economy. For example, when the political environment is stable, more people are likely to vote, showing that voters feel safer and more confident in the process. On the other hand, past performance of political parties and voter habits strongly affect how parties perform in elections, meaning voters often stick to the parties they previously supported.

Economic factors like GDP growth, inflation, and unemployment don’t have a very strong or direct impact on voter turnout or which party wins. However, unemployment and poverty can harm incumbents’ chances of being re-elected, suggesting that voters do respond to economic hardship. Corruption control efforts also influence elections, as reducing corruption may disrupt old political practices and change how people vote. Overall, while the economy matters, Ghana’s election results are shaped more by political stability, how parties have performed in the past, and voters’ trust in the system, rather than just the economic situation at the time.

Table 7.

Vector Autoregression Estimates Results.

Table 7.

Vector Autoregression Estimates Results.

| Vector Autoregression Estimates |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Sample (adjusted): 1994 2023 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Included observations: 30 after adjustments |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Standard errors in ( ) & t-statistics in [ ] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Voter Turnout |

Party Vote Share |

Incumbent ReElection Rate |

Inflation |

Political Stability |

Poverty Rate |

Unemployment Rate |

Income Inequality |

Gross Domestic Product Growth |

Exchange Rate Stability |

CorruptionControl |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| VOTER_TURNOUT(-1) |

1.285565 |

-0.081595 |

-0.016824 |

6.164889 |

-0.023163 |

1.493333 |

-0.127669 |

-0.256750 |

-0.859959 |

0.197591 |

0.023266 |

| |

(0.44044) |

(0.23091) |

(0.14557) |

(4.88595) |

(0.02373) |

(1.32531) |

(0.29324) |

(0.25264) |

(0.84771) |

(0.10677) |

(0.03454) |

| |

[ 2.91882] |

[-0.35336] |

[-0.11557] |

[ 1.26176] |

[-0.97609] |

[ 1.12678] |

[-0.43537] |

[-1.01627] |

[-1.01446] |

[ 1.85062] |

[ 0.67368] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| VOTER_TURNOUT(-2) |

-0.297839 |

-0.043361 |

0.109656 |

-4.110289 |

0.022672 |

-1.745258 |

0.006619 |

0.222399 |

0.972184 |

-0.251934 |

-0.042124 |

| |

(0.42026) |

(0.22033) |

(0.13890) |

(4.66211) |

(0.02264) |

(1.26459) |

(0.27981) |

(0.24107) |

(0.80887) |

(0.10188) |

(0.03295) |

| |

[-0.70870] |

[-0.19680] |

[ 0.78948] |

[-0.88164] |

[ 1.00130] |

[-1.38010] |

[ 0.02366] |

[ 0.92256] |

[ 1.20190] |

[-2.47289] |

[-1.27828] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| PARTY_VOTE_SHARE(-1) |

0.094592 |

1.412079 |

0.090018 |

4.632369 |

-0.023881 |

0.458145 |

-0.214071 |

-0.313805 |

0.831578 |

0.122937 |

0.008199 |

| |

(0.44107) |

(0.23124) |

(0.14577) |

(4.89299) |

(0.02376) |

(1.32722) |

(0.29367) |

(0.25300) |

(0.84893) |

(0.10692) |

(0.03459) |

| |

[ 0.21446] |

[ 6.10643] |

[ 0.61751] |

[ 0.94674] |

[-1.00492] |

[ 0.34519] |

[-0.72896] |

[-1.24032] |

[ 0.97956] |

[ 1.14976] |

[ 0.23708] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| PARTY_VOTE_SHARE(-2) |

-0.311406 |

-0.657100 |

-0.078192 |

-3.228183 |

0.038742 |

-0.183015 |

-0.010699 |

0.186982 |

-0.444704 |

-0.205130 |

-0.022924 |

| |

(0.38509) |

(0.20189) |

(0.12727) |

(4.27191) |

(0.02075) |

(1.15875) |

(0.25639) |

(0.22089) |

(0.74117) |

(0.09335) |

(0.03020) |

| |

[-0.80866] |

[-3.25471] |

[-0.61438] |

[-0.75568] |

[ 1.86728] |

[-0.15794] |

[-0.04173] |

[ 0.84650] |

[-0.60000] |

[-2.19740] |

[-0.75918] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| INCUMBENT_RE_ELECTION_RATE(-1) |

-6.560056 |

0.545585 |

0.146896 |

-13.00397 |

-0.105995 |

-6.531176 |

0.270726 |

0.657296 |

0.171563 |

0.072725 |

0.033480 |

| |

(1.11910) |

(0.58672) |

(0.36986) |

(12.4146) |

(0.06029) |

(3.36744) |

(0.74509) |

(0.64193) |

(2.15391) |

(0.27129) |

(0.08775) |

| |

[-5.86189] |

[ 0.92989] |

[ 0.39716] |

[-1.04747] |

[-1.75794] |

[-1.93951] |

[ 0.36335] |

[ 1.02394] |

[ 0.07965] |

[ 0.26807] |

[ 0.38154] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| INCUMBENT_RE_ELECTION_RATE(-2) |

3.074419 |

0.313034 |

-0.202616 |

54.78968 |

-0.166625 |

16.79246 |

1.478193 |

-2.824837 |

-9.861297 |

2.503144 |

0.267630 |

| |

(3.10773) |

(1.62931) |

(1.02710) |

(34.4752) |

(0.16744) |

(9.35134) |

(2.06911) |

(1.78262) |

(5.98139) |

(0.75336) |

(0.24368) |

| |

[ 0.98928] |

[ 0.19213] |

[-0.19727] |

[ 1.58925] |

[-0.99515] |

[ 1.79573] |

[ 0.71441] |

[-1.58465] |

[-1.64866] |

[ 3.32262] |

[ 1.09827] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| INFLATION(-1) |

-0.016645 |

0.031627 |

0.004550 |

-0.368116 |

-0.005043 |

0.149178 |

0.012185 |

-0.012793 |

0.017916 |

0.006212 |

-0.001675 |

| |

(0.03588) |

(0.01881) |

(0.01186) |

(0.39804) |

(0.00193) |

(0.10797) |

(0.02389) |

(0.02058) |

(0.06906) |

(0.00870) |

(0.00281) |

| |

[-0.46391] |

[ 1.68123] |

[ 0.38369] |

[-0.92482] |

[-2.60848] |

[ 1.38169] |

[ 0.51005] |

[-0.62156] |

[ 0.25943] |

[ 0.71413] |

[-0.59533] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| INFLATION(-2) |

-0.017902 |

0.014100 |

-0.007482 |

-0.157101 |

-0.000256 |

0.101997 |

0.030805 |

0.006793 |

-0.051172 |

0.010342 |

0.000140 |

| |

(0.03849) |

(0.02018) |

(0.01272) |

(0.42700) |

(0.00207) |

(0.11582) |

(0.02563) |

(0.02208) |

(0.07408) |

(0.00933) |

(0.00302) |

| |

[-0.46508] |

[ 0.69871] |

[-0.58815] |

[-0.36791] |

[-0.12327] |

[ 0.88062] |

[ 1.20200] |

[ 0.30766] |

[-0.69072] |

[ 1.10829] |

[ 0.04631] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| POLITICAL_STABILITY(-1) |

11.22054 |

2.953434 |

1.909647 |

108.1306 |

-0.596138 |

10.32928 |

6.770614 |

-3.441376 |

-22.31132 |

1.496695 |

0.503218 |

| |

(5.68807) |

(2.98212) |

(1.87991) |

(63.0998) |

(0.30646) |

(17.1157) |

(3.78709) |

(3.26273) |

(10.9477) |

(1.37888) |

(0.44601) |

| |

[ 1.97264] |

[ 0.99038] |

[ 1.01582] |

[ 1.71365] |

[-1.94524] |

[ 0.60350] |

[ 1.78781] |

[-1.05475] |

[-2.03799] |

[ 1.08544] |

[ 1.12827] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| POLITICAL_STABILITY(-2) |

6.735055 |

0.535928 |

2.374038 |

55.06722 |

0.076500 |

-25.22931 |

4.383710 |

0.297772 |

-7.328671 |

1.122071 |

0.133751 |

| |

(5.91106) |

(3.09903) |

(1.95360) |

(65.5735) |

(0.31847) |

(17.7867) |

(3.93556) |

(3.39064) |

(11.3769) |

(1.43294) |

(0.46350) |

| |

[ 1.13940] |

[ 0.17293] |

[ 1.21521] |

[ 0.83978] |

[ 0.24021] |

[-1.41844] |

[ 1.11387] |

[ 0.08782] |

[-0.64417] |

[ 0.78306] |

[ 0.28857] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| POVERTY_RATE(-1) |

-0.100422 |

-0.002992 |

0.016558 |

-0.012559 |

-0.023720 |

0.749958 |

0.179634 |

-0.094235 |

0.016060 |

0.035626 |

-0.000173 |

| |

(0.12685) |

(0.06651) |

(0.04193) |

(1.40723) |

(0.00683) |

(0.38171) |

(0.08446) |

(0.07276) |

(0.24415) |

(0.03075) |

(0.00995) |

| |

[-0.79163] |

[-0.04499] |

[ 0.39495] |

[-0.00892] |

[-3.47062] |

[ 1.96473] |

[ 2.12688] |

[-1.29507] |

[ 0.06578] |

[ 1.15851] |

[-0.01740] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| POVERTY_RATE(-2) |

0.314414 |

0.086365 |

0.016464 |

1.972798 |

-0.000403 |

0.717614 |

-0.046072 |

-0.025360 |

-0.112425 |

0.050402 |

0.025125 |

| |

(0.15355) |

(0.08050) |

(0.05075) |

(1.70342) |

(0.00827) |

(0.46205) |

(0.10224) |

(0.08808) |

(0.29554) |

(0.03722) |

(0.01204) |

| |

[ 2.04759] |

[ 1.07280] |

[ 0.32442] |

[ 1.15814] |

[-0.04875] |

[ 1.55311] |

[-0.45065] |

[-0.28792] |

[-0.38040] |

[ 1.35403] |

[ 2.08674] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| UNEMPLOYMENT_RATE(-1) |

-0.483647 |

0.135430 |

-0.153432 |

7.261772 |

-0.051542 |

1.335816 |

0.533943 |

-0.244735 |

-1.124221 |

0.000426 |

0.024736 |

| |

(0.63150) |

(0.33108) |

(0.20871) |

(7.00550) |

(0.03402) |

(1.90023) |

(0.42045) |

(0.36224) |

(1.21544) |

(0.15309) |

(0.04952) |

| |

[-0.76586] |

[ 0.40905] |

[-0.73514] |

[ 1.03658] |

[-1.51486] |

[ 0.70298] |

[ 1.26992] |

[-0.67562] |

[-0.92495] |

[ 0.00278] |

[ 0.49953] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| UNEMPLOYMENT_RATE(-2) |

0.991989 |

-0.348606 |

0.233921 |

5.425170 |

-0.007217 |

-2.288512 |

0.154678 |

-0.210855 |

-0.259780 |

-0.020480 |

-0.030046 |

| |

(0.58561) |

(0.30702) |

(0.19354) |

(6.49638) |

(0.03155) |

(1.76213) |

(0.38990) |

(0.33591) |

(1.12711) |

(0.14196) |

(0.04592) |

| |

[ 1.69394] |

[-1.13544] |

[ 1.20862] |

[ 0.83511] |

[-0.22873] |

[-1.29872] |

[ 0.39672] |

[-0.62771] |

[-0.23048] |

[-0.14426] |

[-0.65433] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| INCOME_INEQUALITY__GINI_COEFFICIENT_(-1) |

-1.079439 |

-0.536872 |

-0.207171 |

0.442037 |

-0.114000 |

1.165905 |

-0.329243 |

0.209730 |

0.453456 |

-0.097875 |

0.127466 |

| |

(1.00815) |

(0.52855) |

(0.33319) |

(11.1837) |

(0.05432) |

(3.03357) |

(0.67122) |

(0.57828) |

(1.94036) |

(0.24439) |

(0.07905) |

| |

[-1.07071] |

[-1.01575] |

[-0.62178] |

[ 0.03952] |

[-2.09880] |

[ 0.38433] |

[-0.49051] |

[ 0.36268] |

[ 0.23370] |

[-0.40049] |

[ 1.61247] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| INCOME_INEQUALITY__GINI_COEFFICIENT_(-2) |

1.094576 |

0.609239 |

0.147444 |

19.28967 |

-0.090458 |

6.172928 |

0.408411 |

-0.976417 |

-1.032007 |

0.234770 |

0.092879 |

| |

(1.17970) |

(0.61849) |

(0.38989) |

(13.0868) |

(0.06356) |

(3.54978) |

(0.78544) |

(0.67669) |

(2.27054) |

(0.28598) |

(0.09250) |

| |

[ 0.92784] |

[ 0.98505] |

[ 0.37817] |

[ 1.47398] |

[-1.42320] |

[ 1.73896] |

[ 0.51998] |

[-1.44294] |

[-0.45452] |

[ 0.82094] |

[ 1.00408] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| GROSS_DOMESTIC_PRODUCT__GDP__GROWTH(-1) |

-0.208236 |

0.089957 |

0.056171 |

0.683999 |

-0.014622 |

-1.530643 |

0.030420 |

0.009534 |

-0.516509 |

0.105181 |

0.005411 |

| |

(0.17517) |

(0.09184) |

(0.05789) |

(1.94321) |

(0.00944) |

(0.52709) |

(0.11663) |

(0.10048) |

(0.33714) |

(0.04246) |

(0.01374) |

| |

[-1.18877] |

[ 0.97953] |

[ 0.97026] |

[ 0.35199] |

[-1.54935] |

[-2.90394] |

[ 0.26083] |

[ 0.09489] |

[-1.53201] |

[ 2.47696] |

[ 0.39398] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| GROSS_DOMESTIC_PRODUCT__GDP__GROWTH(-2) |

0.060701 |

0.065994 |

0.044891 |

3.473055 |

-0.004451 |

0.980690 |

0.336917 |

-0.374079 |

-0.848004 |

0.122619 |

0.010279 |

| |

(0.31702) |

(0.16620) |

(0.10477) |

(3.51679) |

(0.01708) |

(0.95392) |

(0.21107) |

(0.18184) |

(0.61016) |

(0.07685) |

(0.02486) |

| |

[ 0.19147] |

[ 0.39706] |

[ 0.42846] |

[ 0.98756] |

[-0.26061] |

[ 1.02806] |

[ 1.59624] |

[-2.05714] |

[-1.38981] |

[ 1.59555] |

[ 0.41352] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| EXCHANGE_RATE_STABILITY(-1) |

0.725887 |

-0.102215 |

0.199958 |

9.250320 |

0.017389 |

-4.048308 |

0.236801 |

0.420330 |

-1.833315 |

1.062040 |

0.042725 |

| |

(1.01597) |

(0.53265) |

(0.33578) |

(11.2706) |

(0.05474) |

(3.05712) |

(0.67643) |

(0.58277) |

(1.95542) |

(0.24629) |

(0.07966) |

| |

[ 0.71447] |

[-0.19190] |

[ 0.59551] |

[ 0.82075] |

[ 0.31767] |

[-1.32422] |

[ 0.35007] |

[ 0.72126] |

[-0.93755] |

[ 4.31218] |

[ 0.53632] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| EXCHANGE_RATE_STABILITY(-2) |

-0.936446 |

0.108216 |

-0.313402 |

-14.71335 |

0.043209 |

5.380572 |

-0.740132 |

-0.512164 |

2.664779 |

0.378747 |

-0.072400 |

| |

(1.59459) |

(0.83601) |

(0.52701) |

(17.6893) |

(0.08591) |

(4.79821) |

(1.06167) |

(0.91467) |

(3.06907) |

(0.38655) |

(0.12503) |

| |

[-0.58726] |

[ 0.12944] |

[-0.59468] |

[-0.83176] |

[ 0.50294] |

[ 1.12137] |

[-0.69714] |

[-0.55994] |

[ 0.86827] |

[ 0.97980] |

[-0.57904] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| CORRUPTION_CONTROL(-1) |

2.283432 |

-4.880410 |

-0.148398 |

-10.06956 |

0.478166 |

-28.93746 |

-5.016546 |

4.686797 |

4.920942 |

-0.701069 |

-0.095214 |

| |

(5.08265) |

(2.66471) |

(1.67981) |

(56.3835) |

(0.27384) |

(15.2940) |

(3.38400) |

(2.91545) |

(9.78246) |

(1.23211) |

(0.39854) |

| |

[ 0.44926] |

[-1.83150] |

[-0.08834] |

[-0.17859] |

[ 1.74614] |

[-1.89208] |

[-1.48243] |

[ 1.60757] |

[ 0.50304] |

[-0.56900] |

[-0.23891] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| CORRUPTION_CONTROL(-2) |

-0.008471 |

1.133988 |

0.108222 |

35.43242 |

0.038447 |

-2.543793 |

-0.809557 |

-3.051479 |

7.561378 |

-0.554334 |

-0.481261 |

| |

(3.93623) |

(2.06367) |

(1.30092) |

(43.6660) |

(0.21207) |

(11.8443) |

(2.62072) |

(2.25785) |

(7.57598) |

(0.95421) |

(0.30865) |

| |

[-0.00215] |

[ 0.54950] |

[ 0.08319] |

[ 0.81144] |

[ 0.18129] |

[-0.21477] |

[-0.30891] |

[-1.35150] |

[ 0.99807] |

[-0.58094] |

[-1.55927] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| C |

-1.671232 |

3.948941 |

-5.080447 |

-1112.322 |

9.765109 |

-322.4794 |

2.474551 |

87.95809 |

38.39473 |

-7.355311 |

-8.991499 |

| |

(80.2106) |

(42.0525) |

(26.5096) |

(889.804) |

(4.32156) |

(241.358) |

(53.4039) |

(46.0095) |

(154.380) |

(19.4443) |

(6.28944) |

| |

[-0.02084] |

[ 0.09391] |

[-0.19165] |

[-1.25007] |

[ 2.25962] |

[-1.33610] |

[ 0.04634] |

[ 1.91174] |

[ 0.24870] |

[-0.37828] |

[-1.42962] |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| R-squared |

0.989879 |

0.997779 |

0.874218 |

0.800534 |

0.977131 |

0.984697 |

0.975035 |

0.954905 |

0.831767 |

0.997548 |

0.889980 |

| Adj. R-squared |

0.958072 |

0.990799 |

0.478905 |

0.173643 |

0.905258 |

0.936604 |

0.896574 |

0.813176 |

0.303036 |

0.989841 |

0.544202 |

| Sum sq. resids |

8.598096 |

2.363318 |

0.939169 |

1058.102 |

0.024959 |

77.85070 |

3.811392 |

2.829000 |

31.85068 |

0.505272 |

0.052864 |

| S.E. equation |

1.108287 |

0.581048 |

0.366288 |

12.29461 |

0.059712 |

3.334896 |

0.737892 |

0.635722 |

2.133096 |

0.268667 |

0.086902 |

| F-statistic |

31.12113 |

142.9463 |

2.211457 |

1.276990 |

13.59524 |

20.47459 |

12.42700 |

6.737566 |

1.573137 |

129.4334 |

2.573846 |

| Log likelihood |

-23.82331 |

-4.451194 |

9.391205 |

-96.01367 |

63.80785 |

-56.87209 |

-11.62011 |

-7.149047 |

-43.46607 |

18.68968 |

52.55023 |

| Akaike AIC |

3.121554 |

1.830080 |

0.907253 |

7.934245 |

-2.720523 |

5.324806 |

2.308008 |

2.009936 |

4.431072 |

0.287354 |

-1.970015 |

| Schwarz SC |

4.195805 |

2.904331 |

1.981504 |

9.008496 |

-1.646272 |

6.399057 |

3.382259 |

3.084188 |

5.505323 |

1.361606 |

-0.895764 |

| Mean dependent |

74.63208 |

8.211417 |

0.533333 |

19.99143 |

-0.199977 |

40.23000 |

5.629033 |

41.94333 |

5.290433 |

2.407900 |

-0.152138 |

| S.D. dependent |

5.412539 |

6.057505 |

0.507416 |

13.52480 |

0.193995 |

13.24496 |

2.294448 |

1.470792 |

2.555083 |

2.665521 |

0.128720 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Determinant resid covariance (dof adj.) |

0.000000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Determinant resid covariance |

0.000000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Number of coefficients |

253 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4.7.3. Predictive model using economic indicators to forecast the electoral outcomes of Ghana’s 2024 general elections

Voter Turnout

The results of the ARIMA model in

Table 8 shed light on the dynamics of voter turnout in Ghana over the sample period from 1993 to 2023. This analysis focuses on understanding how previous voter turnout levels (autoregressive terms) and random shocks (moving average terms) contribute to changes in voter turnout, as well as the overall performance of the model. The constant term (C) in the model is positive, with a coefficient of 0.562 and a p-value of 0.0552, which is just outside the typical 5% significance level. This suggests that there is a weak but positive underlying trend in voter turnout growth over time. Essentially, even in the absence of autoregressive or moving average effects, the model expects a slight increase in voter turnout, though this trend is not strongly significant.

The autoregressive component of the model, AR(4), is highly significant, with a coefficient of -0.954976 and a p-value of 0.0000. The negative sign indicates that voter turnout exhibits a strong inverse relationship with its values four periods (or elections) ago. This suggests that if voter turnout was high four elections ago, it is likely to be lower in the current election. This cyclical pattern may reflect fluctuations in voter engagement over time, possibly due to alternating political dissatisfaction, engagement levels, or shifts in political loyalty over electoral cycles.

The moving average term, MA(4), has a positive coefficient of 0.239116, but it is not statistically significant with a p-value of 0.4261. This indicates that the random shocks or external influences from four elections ago do not have a significant impact on the current voter turnout. This could imply that short-term fluctuations or irregular shocks do not persist long enough to influence voter behavior across multiple elections.

The model’s R-squared value of 0.824 indicates that about 82% of the variation in voter turnout is explained by the model. This is a strong indication of the model’s goodness-of-fit, suggesting that the ARIMA specification captures much of the dynamics in voter turnout data. However, the Durbin-Watson statistic of 0.289 points to a potential issue with serial correlation in the residuals, which could indicate that the model has not fully accounted for all time-dependent structures in the data. This suggests that further refinement of the model, perhaps by adding additional lags or adjusting the ARIMA specification, could improve the overall fit and reliability of the predictions. The model’s residual variance, represented by SIGMASQ (with a value of 2.743759), suggests that while the model fits well, there is still a moderate amount of unexplained variability in the voter turnout series. This residual variability could be driven by unaccounted-for external factors like political events, economic shocks, or changes in voter sentiment that the ARIMA model alone cannot capture.

In addition, the inverted AR roots and inverted MA roots are displayed as complex numbers, with both the AR and MA roots exhibiting real and imaginary components. All roots have absolute values less than 1, which confirms that the model is stable. Stability in this context implies that the model will not produce explosive forecasts over time and will converge towards a consistent pattern, making it suitable for long-term forecasting. The F-statistic is highly significant (p-value 0.000000), confirming that the overall model is statistically significant. This suggests that the combination of the constant term, autoregressive terms, and moving average terms provides a reliable explanation of the changes in voter turnout.

On the other hand, the relatively high Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Schwarz Criterion (SC) values suggest that there may still be room for model improvement. These information criteria penalize models with more parameters, and while this model is performing well, exploring other ARIMA specifications with different lags could potentially reduce these values and yield a more parsimonious model. Thus, the ARIMA model demonstrates that voter turnout in Ghana exhibits a cyclical pattern, where turnout levels from previous elections have a strong negative influence on current turnout. However, the impact of random shocks does not appear to persist over time. While the model explains a significant portion of the variation in voter turnout, the presence of serial correlation in the residuals indicates that further refinements could improve its predictive power. Nevertheless, the model provides valuable insights into the underlying dynamics of voter behavior in Ghana and could be a useful tool for forecasting future electoral outcomes, particularly voter turnout trends.

Based on the ARIMA(4,1,4) specification, the final equation for voter turnout prediction could be written as:

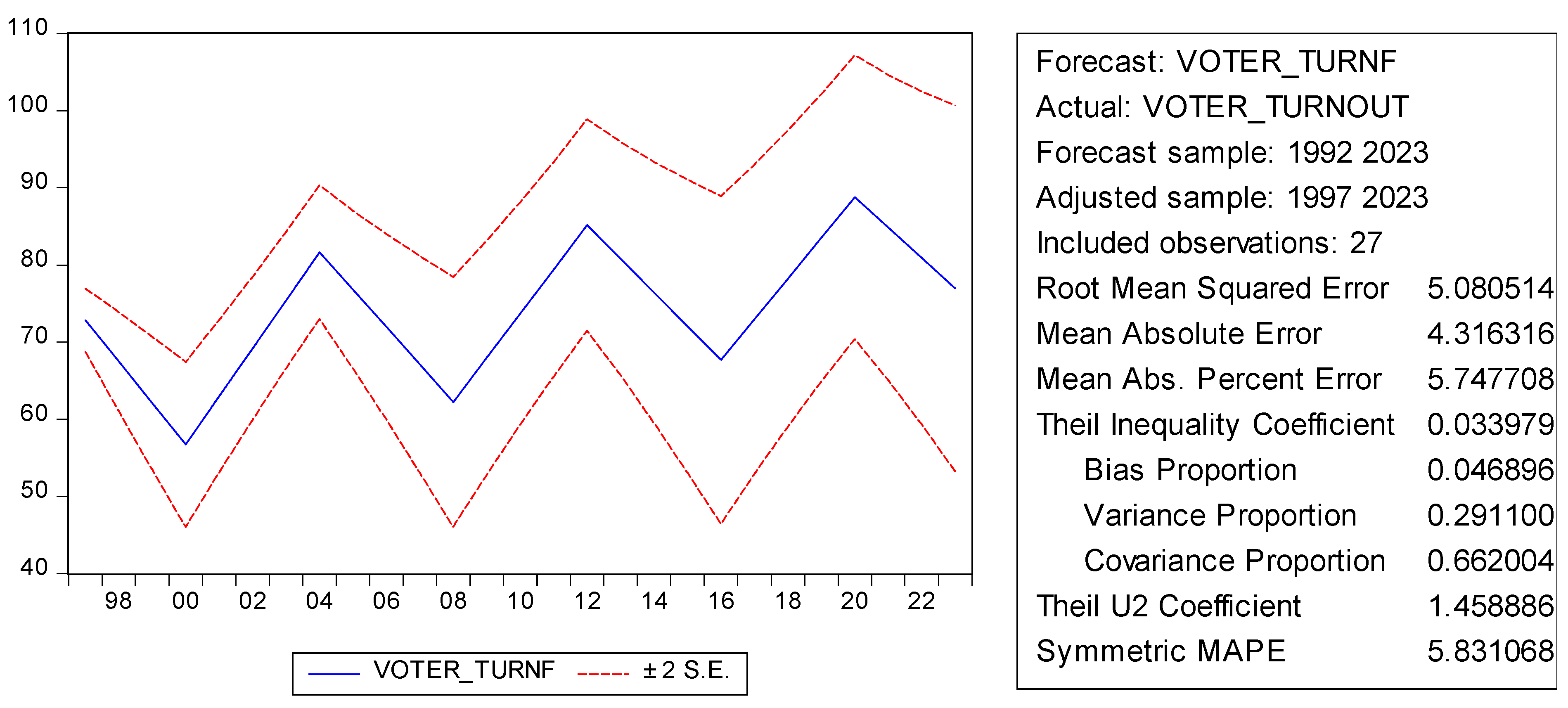

Based on the ARIMA forecast model and the

Figure 1, the forecasted voter turnout for the 2024 election is expected to be around 70%. The confidence intervals (the red dashed lines in the graph) provide a range within which the actual voter turnout may fall, but the forecasted value specifically indicates that voter turnout is predicted to be slightly below the 2016 and 2020 turnout levels. This decline follows a pattern of cyclical fluctuations seen in the historical data, with the model indicating that voter turnout is likely to drop somewhat in the next election cycle. However, there is a possibility that it could vary based on unforeseen factors closer to the election date, but the forecast points toward a turnout near 70% for 2024.

Party Votes Share

The results of the ARMA model for the dependent variable "Party Vote Share" in

Table 9 provide several insights into the dynamics and factors influencing party performance in elections. The coefficient of the constant term is -0.872128, suggesting a negative average change in party vote share over time, although the effect is not statistically significant (p-value = 0.1611). This implies that, on average, there is a decline in party vote share, but the effect is not strong enough to draw definitive conclusions without considering other factors.

The autoregressive term (AR(1)) has a positive and statistically significant coefficient (0.770149) with a p-value of 0.0136. This indicates that past values of party vote share strongly influence current values. Specifically, the positive AR(1) coefficient suggests that if the party’s vote share increased in the previous election, it is likely to remain high or continue increasing in the next election. This persistence in party performance is critical, as it implies that parties with growing support may be able to maintain that momentum.

The moving average (MA(1)) term has a small coefficient (0.106585) and is not statistically significant (p-value = 0.9176). This suggests that short-term shocks or random fluctuations in party vote share have little to no impact on future vote share. The lack of significance in the MA(1) term means that temporary disturbances in voter preferences do not play a major role in determining future party performance.

The variance of the residuals (0.589599) is statistically significant (p-value = 0.0011), suggesting that the variability in the changes in party vote share is captured effectively by the model. The significant sigma squared value highlights that, while the model explains a portion of the variation, there is still some inherent unpredictability in vote share changes.

With regards to model fitness, the R-squared value of 0.650888 indicates that approximately 65% of the variation in party vote share changes is explained by the ARMA model. The adjusted R-squared (0.612098) further confirms the model’s goodness-of-fit after accounting for the number of predictors. These values suggest a reasonably good fit, but also point to the possibility that other factors (beyond autoregressive patterns and short-term shocks) may influence party vote share. The F-statistic of 16.77969 and its corresponding p-value (0.000002) show that the model as a whole is statistically significant. This means that the ARMA model effectively captures the overall dynamics of party vote share changes. The Durbin-Watson statistic is 1.943107, which is close to 2, indicating no substantial autocorrelation in the residuals. This is important because it suggests that the model does not suffer from serial correlation, further validating its reliability.

In essence, the ARMA model indicates that the most significant factor in predicting changes in party vote share is its past performance. While the model provides a solid fit, explaining 65% of the variation in party vote share changes, there remains unexplained variability. Future work could involve incorporating additional economic or political variables to improve the predictive power of the model.

Based on the ARIMA(1,1,1) specification, the final equation for voter turnout prediction could be written as:

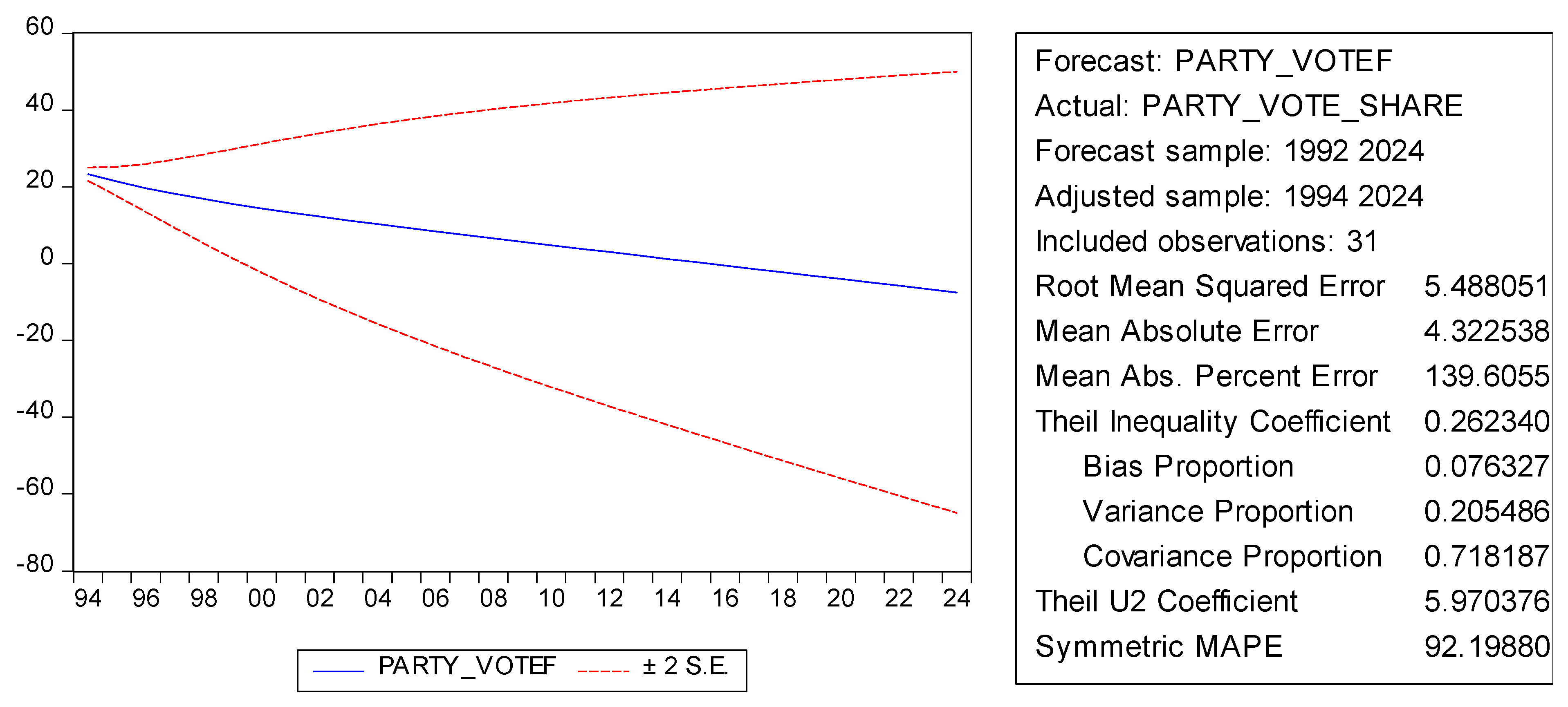

With regards to the forcast,

Figure 2 clearly shows a decline in the projected vote share for the 2024 elections. This suggests that, without significant intervention or changes in strategy, the party under study (incumbent) may continue to lose support. The increasing variance and uncertainty as shown by the widening confidence intervals further reinforce that external shocks or unexpected events could result in further volatility in vote shares, either positively or negatively. Economic conditions like inflation, unemployment, and poverty rates, which were included in the overall forecast model, likely contribute to the forecasted downward trend. Historically, poor economic performance often erodes electoral support for incumbents or dominant parties, which seems to be reflected in this forecast.

The bias proportion in the Theil Inequality Coefficient is low, meaning the model does not systematically over or underestimate the party’s vote share. However, with a high variance proportion, it is clear that the model may struggle to capture all the dynamics that could influence voter behavior in this specific context. In summary, based on the ARMA model’s output and forecast for party vote share, the party being evaluated (incumbent) faces a declining trend in 2024, with a significant degree of uncertainty. While past performance plays a significant role in determining future outcomes, current economic and political dynamics may further erode the party’s support. Therefore, to mitigate this projected decline, significant adjustments in political strategy, combined with addressing key economic concerns, would be necessary before the 2024 election.

Incumbent Re-Election Rate

The ARMA model for the Incumbent Re-Election Rate presents some notable results, reflecting both the statistical performance of the model and its implications for predicting future electoral outcomes in Ghana. The interpretation of the coefficients, AR and MA terms, as well as the overall goodness of fit, reveals a high degree of model precision, but also indicates potential areas for deeper exploration. The constant term (C) in this model is extremely close to zero, with a coefficient of 3.21E-14 and a t-statistic of 1.07E-11. This suggests that the model assumes no systematic baseline effect for the incumbent re-election rate outside of what is explained by the autoregressive and moving average terms. The corresponding probability value of 1.0000 further indicates that the constant term is statistically insignificant.

The most striking result comes from the AR(4) term, which has a coefficient of -1.000000 and an extremely large t-statistic of -1.35E+11, with a probability value of 0.0000. This clearly suggests that the autoregressive process is highly significant and plays a dominant role in explaining the incumbent re-election rate. The fact that the AR term is negative with a magnitude of 1 indicates a perfect, negative correlation between the incumbent re-election rate and its values four periods prior. In other words, the incumbent re-election rate is heavily influenced by its performance in previous cycles, showing a complete reversal in the trend over time.

However, the MA(4) term is insignificant, with a coefficient of -1.000000 and a high probability value of 0.4885, indicating that the moving average process does not significantly impact the model’s results. This suggests that short-term shocks or deviations from the norm do not have a substantial effect on the incumbent re-election rate, further reinforcing the dominance of the long-term autoregressive component. The model’s error variance (SIGMASQ) is statistically significant, with a coefficient of 9.12E-14 and a probability value of 0.0172. This suggests that the model captures the variance in the incumbent re-election rate quite well.

The overall performance of the model is extremely high, as indicated by an R-squared and adjusted R-squared value of 1.000000. This implies that the model explains virtually all the variation in the dependent variable (incumbent re-election rate). This high level of fit, while impressive, could also be a potential sign of overfitting, where the model is too tightly tailored to the historical data, and thus might not generalize well to new data. The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Schwarz Criterion (SC) are extremely low, at -23.23469 and -23.04966, respectively, further reinforcing the precision of the model. Similarly, the Durbin-Watson statistic is 2.000000, which indicates that there is no significant autocorrelation in the residuals, thus confirming the reliability of the model in terms of its error structure.

The inverted AR roots show complex values with both real and imaginary components, suggesting a cyclical pattern in the incumbent re-election rate. The roots of .71+.71i and -.71-.71i indicate that the model is capturing a non-stationary process with cycles of approximately four periods. However, the note that the "estimated AR process is non-stationary" suggests some caution in the interpretation of the model’s predictions over the long term. The inverted MA roots indicate a less stable moving average process, particularly with roots at 1.00 and -1.00, reflecting the lack of significance of the MA component in the model.

In summary, the ARMA model for the incumbent re-election rate reveals a significant and highly deterministic pattern where the previous electoral performance of incumbents plays a central role in explaining future re-election outcomes. The negative AR(4) term suggests a strong reversal effect over time, meaning that incumbents who perform well in one cycle may face diminishing returns in the next. However, the insignificant MA term implies that short-term shocks do not greatly affect the incumbent re-election rate, and the model captures the long-term dynamics more effectively. While the model performs extremely well statistically, the note on non-stationarity in the AR process means that there may be some instability in future forecasts. Therefore, further refinement or the introduction of additional variables could help improve the robustness of the model for forecasting future election outcomes.

Based on the ARIMA(4,1,4) specification, the final equation for voter turnout prediction could be written as:

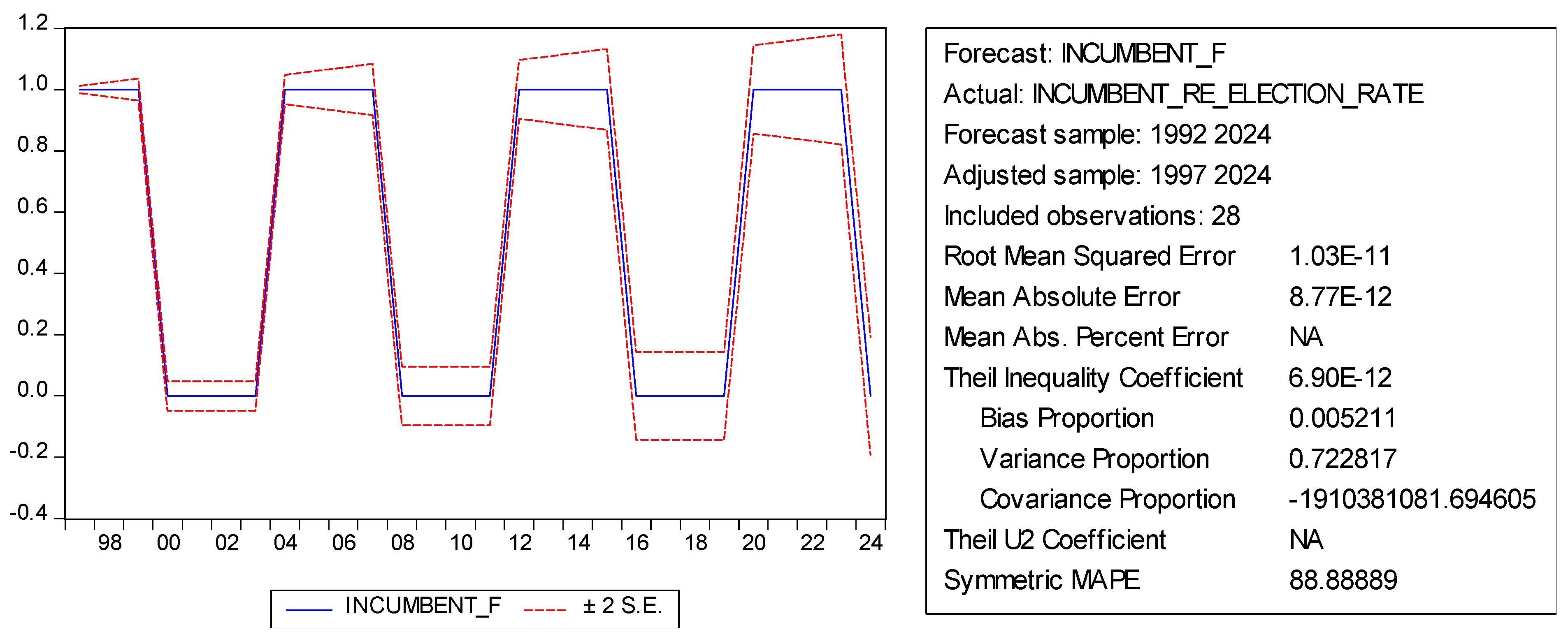

The forecast for Incumbent Re-Election Rate shows a consistent pattern of cyclical variations over time. The forecast chart captures the periodic fluctuations in the incumbent’s likelihood of being re-elected, with noticeable peaks and troughs corresponding to the election cycles observed from 1997 to 2024. The graph (Figue 3) clearly highlights a regular cyclic trend, with the incumbent re-election rate peaking and falling periodically. This reflects the natural electoral cycle where incumbents face periods of stronger and weaker re-election prospects. The forecasted values show that after every election, there is a high chance of incumbency success followed by a decline, aligning with past trends.

Also, the incumbent re-election rate seems to exhibit peaks every four years, which coincides with Ghana’s election cycle. These peaks reflect periods when incumbents are likely to win, followed by a sharp decline in the subsequent periods. The

Figure 3 predicts a notable drop in the incumbent re-election rate leading into the 2024 elections. This means the incumbent party or candidate might face significant challenges in securing re-election, as reflected in the downward trend. The Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) of 1.03E-11 is extremely small, indicating that the model fits the data almost perfectly. However, the high Symmetric MAPE of 88.88889 suggests that there might be large deviations in percentage terms for some observations, though absolute errors remain small. The low Theil Inequality Coefficient (6.90E-12) and Bias Proportion (0.005211) indicate that the model has captured the underlying dynamics well without significant bias. The Variance Proportion (0.722817) implies that most of the forecast error is due to differences in the variance between the forecasted and actual values.

Thus, the forecast for the Incumbent Re-Election Rate in 2024 suggests a declining likelihood of the incumbent’s re-election success. This decline aligns with the cyclical pattern observed in previous election years. The model has done well in capturing historical patterns, and the small errors indicate a high level of accuracy. However, the forecast highlights that incumbents are likely to face stiff competition in 2024, potentially losing their re-election bid. The cyclical peaks and troughs in the forecast align with past electoral outcomes, providing a robust prediction for the upcoming election.