Submitted:

04 June 2025

Posted:

05 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

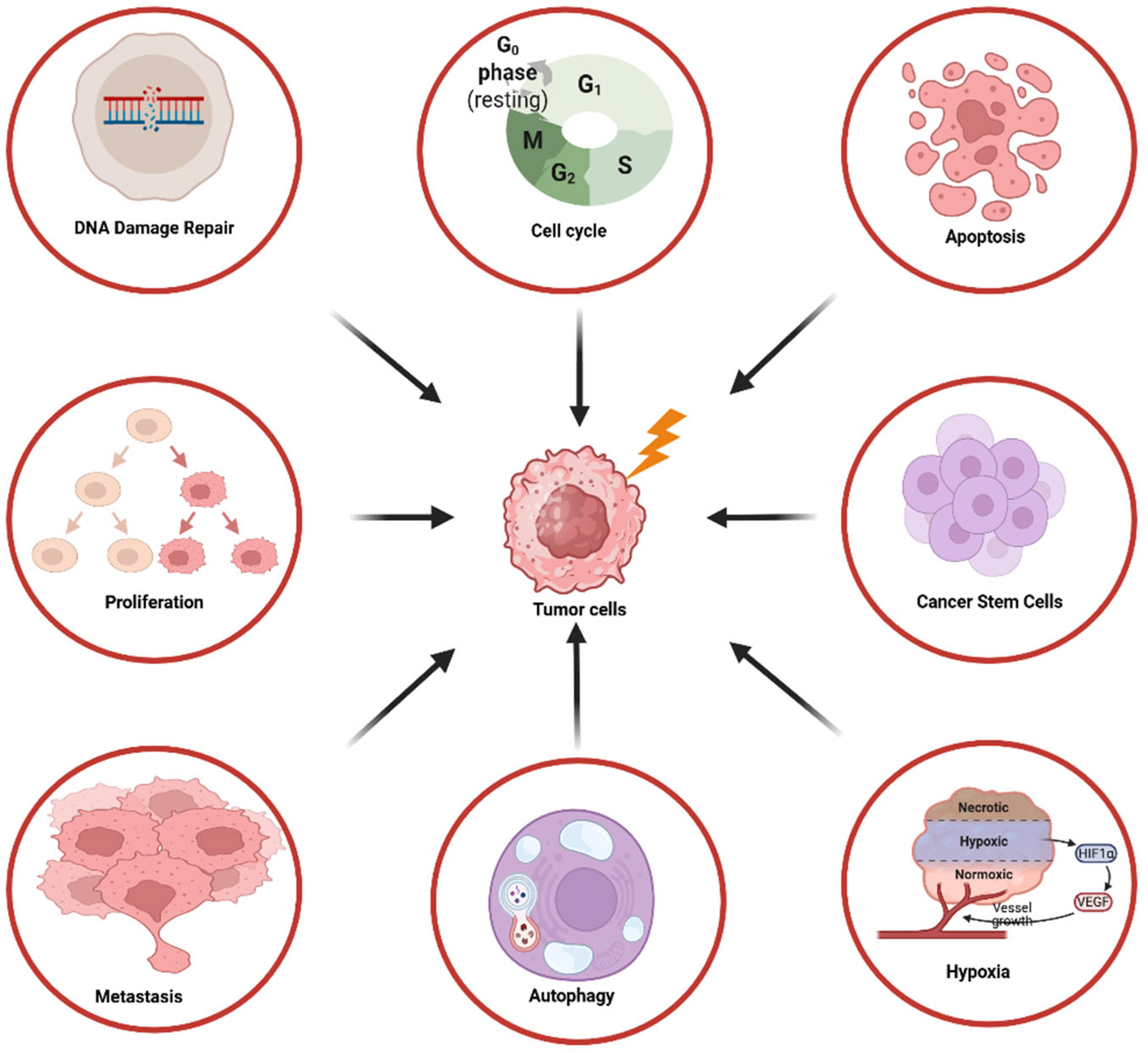

2. The Role of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway in Tumor Radioresistance

2.1. DNA Damage Repair

2.2. Cell Cycle

2.3. Cell Proliferation and Apoptosis

2.4. Cell Invasion and Metastasis

2.5. Autophagy and Hypoxia

2.6. Cancer Stem Cells

3. The Impact of Different PI3K/AKT/mTOR Isoforms on Radiosensitivity

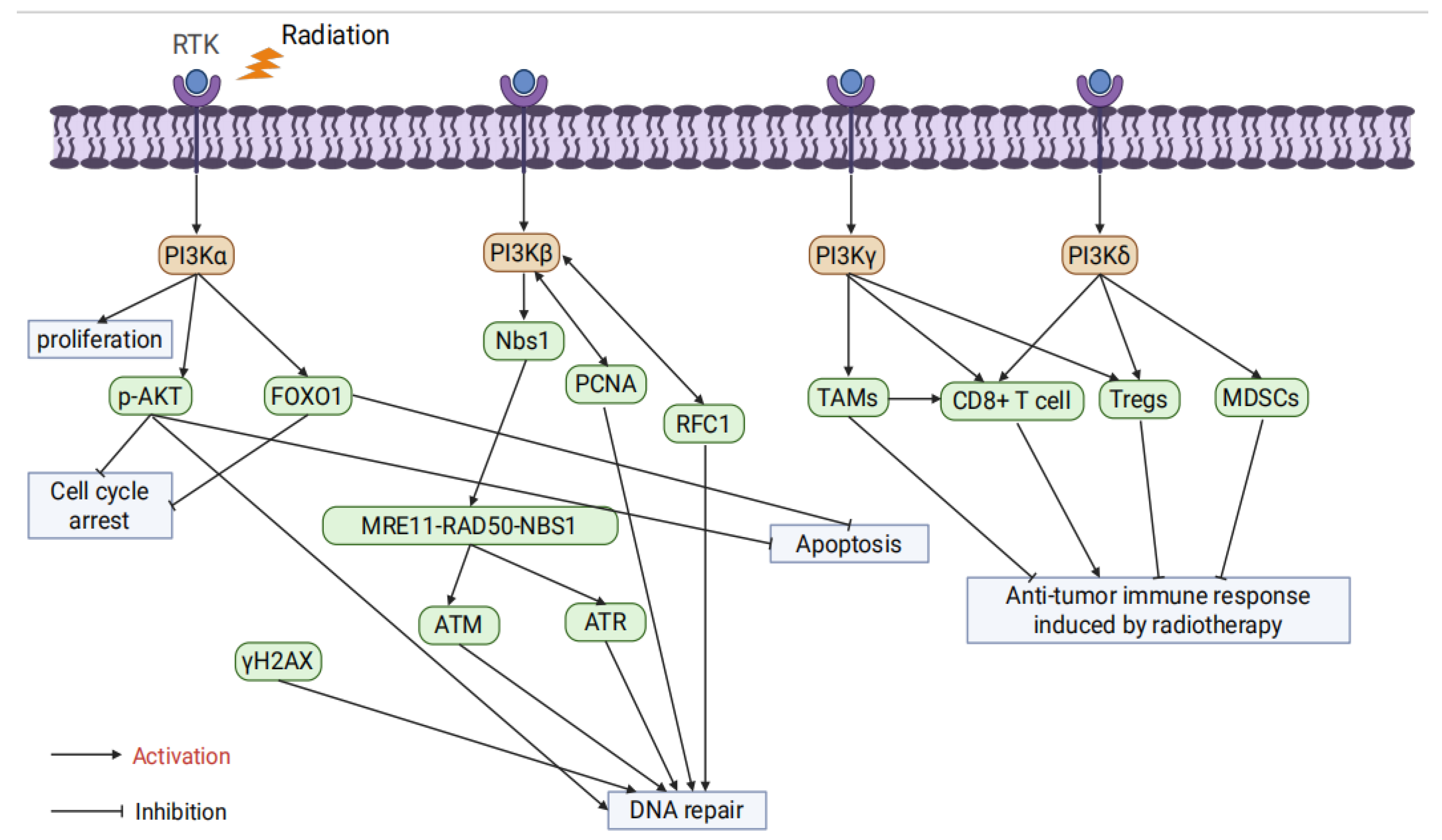

3.1. PI3K Isoforms

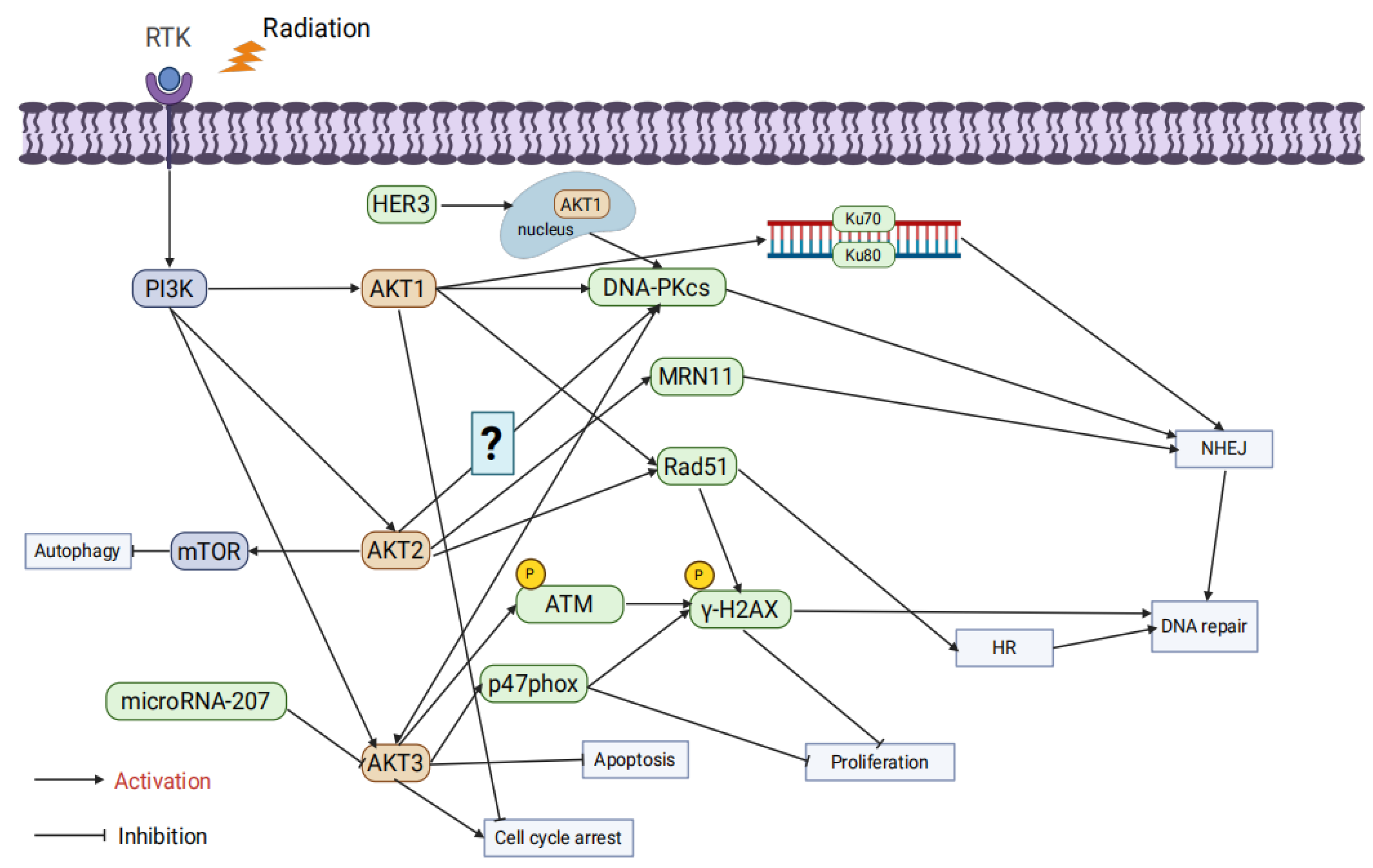

3.2. AKT Isoforms

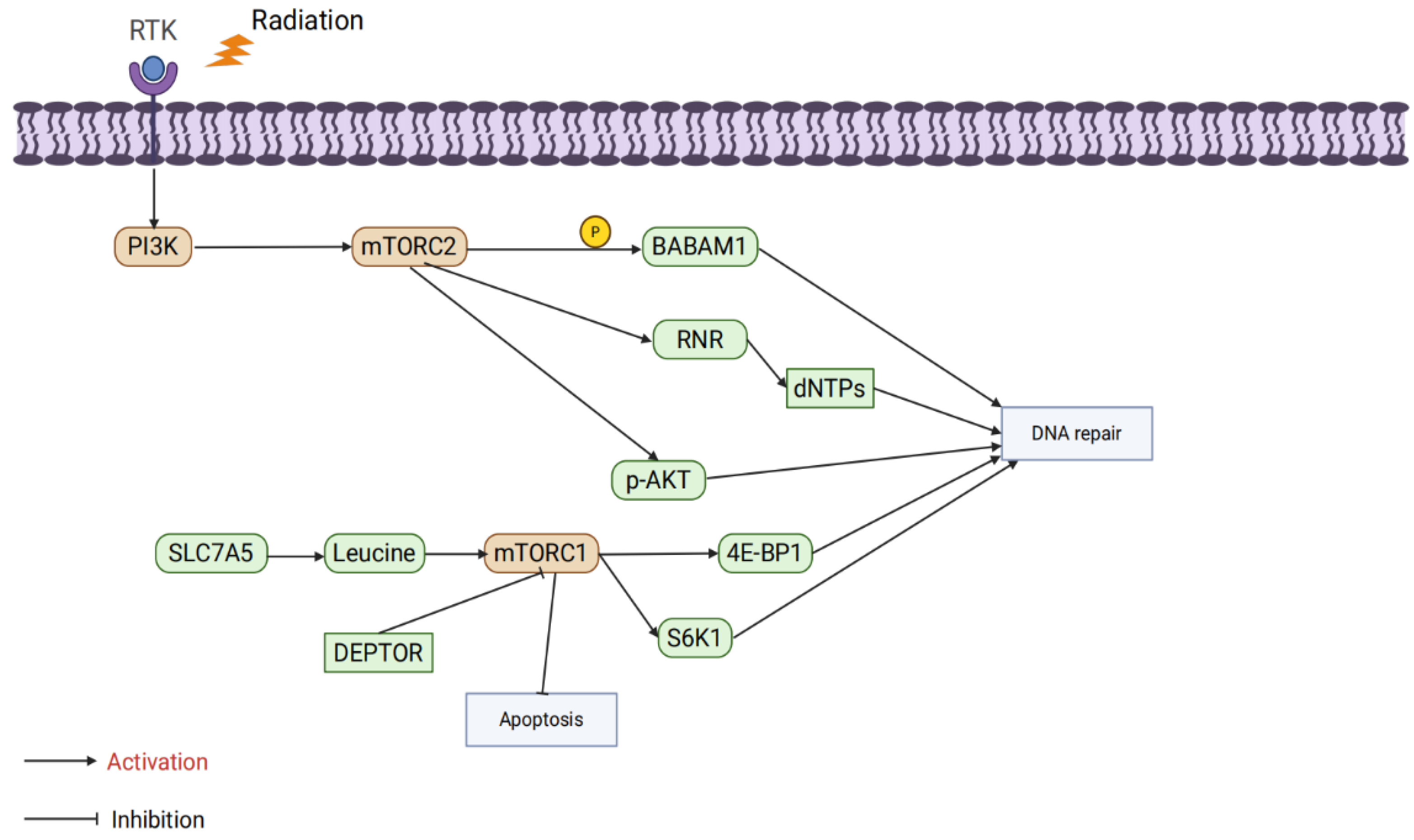

3.3. mTOR Isoforms

4. Preclinical Studies of PI3K/AKT/mTOR Inhibitors Combined with Radiotherapy

4.1. Digestive System Tumors

4.2. Genitourinary System Tumors

4.3. Respiratory System Tumors

4.4. Breast Cancer

4.5. Central Nervous System Tumors

5. Clinical Studies on PI3K/AKT/mTOR Inhibitors Combined with Radiotherapy

6. Future Research Directions

6.1. Molecular Design and Targeted Optimization of Novel Inhibitors

6.2. Combination Therapy Strategies

6.3. Identification of Predictive Tumor Biomarkers

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 4E-BP1 | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein 1 |

| 53BP1 | p53-binding protein 1 |

| A2aR | Adenosine A2a receptor |

| AKT | Protein Kinase B |

| ANXA6 | Annexin A6 |

| APLNR | Apelin Receptor |

| ATG5 | Autophagy-related gene 5 |

| ATM | Ataxia telangiectasia mutated |

| ATR | Ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related |

| BABAM1 | BRISC and BRCA1-A complex member 1 |

| BAD | Bcl-2-associated agonist of cell death |

| Bax | Bcl-2-associated X protein |

| Bcl-2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| C2orf40 | Chromosome 2 open reading frame 40 |

| CALD1 | Caldesmon 1 |

| CD44 | Cluster of Differentiation 44 |

| CDK1 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 1 |

| Chk2 | Checkpoint kinase 2 |

| c-Jun | Cellular Jun proto-oncogene |

| CRC | Colorectal cancer |

| CSCs | Cancer stem cells |

| DDRs | DNA damage responses |

| DEPTOR | DEP domain-containing mTOR-interacting protein |

| DNA-PKcs | DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit |

| DSBs | DNA double-strand breaks |

| EMT | Epithelial-mesenchymal transition |

| EpCAM | Epithelial cell adhesion molecule |

| ESCC | Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma |

| FA | Fanconi anemia |

| FAM135B | Family with sequence similarity 135, member B |

| FANCD2 | Fanconi anemia complementation group D2 |

| FOXO1 | Forkhead Box O1 |

| GBM | Glioblastoma |

| Glut-1 | Glucose transporter 1 |

| GSK-3β | Glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta |

| GβL | G-protein β-subunit-like protein |

| HIF-1α | Hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha |

| HNSCC | Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma |

| HR | Homologous recombination |

| Hsp90 | Heat shock protein 90 |

| IMRT | Intensity-modulated radiotherapy |

| LC3-II | Microtubule-Associated Protein 1 Light Chain 3 II |

| MDSC | Myeloid-derived suppressor cell |

| mLST8 | Mammalian lethal with SEC13 protein 8 |

| MRN | MRE11-RAD50-NBS1 complex |

| mTOR | Mammalian target of rapamycin |

| Nbs1 | Nijmegen Breakage Syndrome 1 protein |

| NEDD8 | Neural precursor cell expressed, developmentally downregulated 8 |

| NHEJ | Non-homologous end joining |

| NPC | Nasopharyngeal carcinoma |

| NSCLC | Non-small cell lung cancer |

| OCT-4 | Octamer-binding transcription factor 4 |

| OS | Overall survival |

| P62 | Sequestosome-1 |

| PARP1 | Poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase 1 |

| PCNA | Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen |

| PDK1 | Phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1 |

| PFS | progression-free survival |

| PI3K | Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase |

| PRAS40 | Proline-rich AKT substrate of 40 kDa |

| PTEN | phosphatase and tensin homolog |

| RAPTOR | Regulatory-Associated Protein of mTOR |

| Rad51 | RAD51 Recombinase |

| Rb | Retinoblastoma protein |

| RCC | Renal cell carcinoma |

| RFC1 | Replication Factor C Subunit 1 |

| RNR | Phosphorylates ribonucleotide reductase |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| S2056 | Serine 2056 |

| S6K | Sibosomal protein S6 kinase |

| SBRT | Stereotactic body radiotherapy |

| SCLC | Small cell lung cancer |

| SIN1 | Stress-activated protein kinase-interacting protein 1 |

| SIRT6 | Sirtuin 6 |

| SLC7A5 | Solute Carrier Family 7 Member A5 |

| SMA | Smooth muscle actin |

| SOX2 | SRY-box transcription factor 2 |

| SSBs | Single-strand breaks |

| TAMs | Tumor-associated macrophages |

| TEH | Tenacissoside H |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Jemal, A. Cancer Statistics, 2024. CA. Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 12–49. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Zheng, X.; Ding, C.; Zou, Z.; Liang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Li, X. Deciphering the Biological Effects of Radiotherapy in Cancer Cells. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1167. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Zhang, P.; Han, X.; Ren, H.; Yu, W.; Hao, W.; Luo, B.; Khan, M.I.; Chen, N. Role of Ionizing Radiation Activated NRF2 in Lung Cancer Radioresistance. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 241, 124476. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, Z.; Yang, J.; Peng, S.; Zhou, Q.; Yao, K.; Cai, W.; Xie, Z.; Qin, F.; Li, H.; et al. Loss of NEIL3 Activates Radiotherapy Resistance in the Progression of Prostate Cancer. Cancer Biol. Med. 2021, 19, 1193–1210. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zheng, M.; Zhang, R.; Jiang, Q.; Du, G.; Wu, Y.; Yang, C.; Li, F.; Li, W.; Wang, L.; et al. RNF126-Mediated MRE11 Ubiquitination Activates the DNA Damage Response and Confers Resistance of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer to Radiotherapy. Adv. Sci. Weinh. Baden-Wurtt. Ger. 2023, 10, e2203884. [CrossRef]

- Kimura, T.; Fujiwara, T.; Kameoka, T.; Adachi, Y.; Kariya, S. The Current Role of Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy (SBRT) in Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC). Cancers 2022, 14, 4383. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Ma, X.; He, D.; Dong, B.; Qiao, T. Neoadjuvant SBRT Combined with Immunotherapy in NSCLC: From Mechanisms to Therapy. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1213222. [CrossRef]

- Sriramulu, S.; Thoidingjam, S.; Brown, S.L.; Siddiqui, F.; Movsas, B.; Nyati, S. Molecular Targets That Sensitize Cancer to Radiation Killing: From the Bench to the Bedside. Biomed. Pharmacother. Biomedecine Pharmacother. 2023, 158, 114126. [CrossRef]

- Meattini, I.; Livi, L.; Lorito, N.; Becherini, C.; Bacci, M.; Visani, L.; Fozza, A.; Belgioia, L.; Loi, M.; Mangoni, M.; et al. Integrating Radiation Therapy with Targeted Treatments for Breast Cancer: From Bench to Bedside. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2022, 108, 102417. [CrossRef]

- Elbanna, M.; Chowdhury, N.N.; Rhome, R.; Fishel, M.L. Clinical and Preclinical Outcomes of Combining Targeted Therapy with Radiotherapy. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 749496. [CrossRef]

- Glaviano, A.; Foo, A.S.C.; Lam, H.Y.; Yap, K.C.H.; Jacot, W.; Jones, R.H.; Eng, H.; Nair, M.G.; Makvandi, P.; Geoerger, B.; et al. PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling Transduction Pathway and Targeted Therapies in Cancer. Mol. Cancer 2023, 22, 138. [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Mei, W.; Zeng, C. PI3K/Akt/mTOR Pathway and Its Role in Cancer Therapeutics: Are We Making Headway? Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 819128. [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Wei, J.; Liu, P. Attacking the PI3K/Akt/mTOR Signaling Pathway for Targeted Therapeutic Treatment in Human Cancer. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 85, 69–94. [CrossRef]

- Wanigasooriya, K.; Tyler, R.; Barros-Silva, J.D.; Sinha, Y.; Ismail, T.; Beggs, A.D. Radiosensitising Cancer Using Phosphatidylinositol-3-Kinase (PI3K), Protein Kinase B (AKT) or Mammalian Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) Inhibitors. Cancers 2020, 12, 1278. [CrossRef]

- Mardanshahi, A.; Gharibkandi, N.A.; Vaseghi, S.; Abedi, S.M.; Molavipordanjani, S. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling Pathway Inhibitors Enhance Radiosensitivity in Cancer Cell Lines. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.-X.; Zhou, P.-K. DNA Damage Response Signaling Pathways and Targets for Radiotherapy Sensitization in Cancer. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 60. [CrossRef]

- Monge-Cadet, J.; Moyal, E.; Supiot, S.; Guimas, V. DNA Repair Inhibitors and Radiotherapy. Cancer Radiother. J. Soc. Francaise Radiother. Oncol. 2022, 26, 947–954. [CrossRef]

- Moosavi, F.; Hassani, B.; Nazari, S.; Saso, L.; Firuzi, O. Targeting DNA Damage Response in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: A Review of Preclinical and Clinical Evidence. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2024, 1879, 189185. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Li, A.; Sun, C.; Li, R.; Xing, Y.; Shi, M.; Wang, Q. PKI-587 Enhances Radiosensitization of Hepatocellular Carcinoma by Inhibiting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathways and DNA Damage Repair. PLOS One 2021, 16, e0258817. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, B.; Tomimatsu, N.; Amancherla, K.; Camacho, C.V.; Pichamoorthy, N.; Burma, S. The Dual PI3K/mTOR Inhibitor NVP-BEZ235 Is a Potent Inhibitor of ATM- and DNA-PKCs-Mediated DNA Damage Responses. Neoplasia N. Y. N 2012, 14, 34–43. [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Jin, H.; Li, S.; Xu, L.; Peng, Z.; Wei, G.; Long, J.; Guo, Y.; Kuang, M.; Zhou, Q.; et al. Apatinib Potentiates Irradiation Effect via Suppressing PI3K/AKT Signaling Pathway in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. CR 2019, 38, 454. [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Oswald, D.; Phelps, D.; Cam, H.; Pelloski, C.E.; Pang, Q.; Houghton, P.J. Regulation of FANCD2 by the mTOR Pathway Contributes to the Resistance of Cancer Cells to DNA Double-Strand Breaks. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 3393–3401. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Michowski, W.; Kolodziejczyk, A.; Sicinski, P. The Cell Cycle in Stem Cell Proliferation, Pluripotency and Differentiation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019, 21, 1060–1067. [CrossRef]

- Pawlik, T.M.; Keyomarsi, K. Role of Cell Cycle in Mediating Sensitivity to Radiotherapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2004, 59, 928–942. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Li, W.; Ai, J.; Xie, J.; Zhang, X. C2orf40 Inhibits Metastasis and Regulates Chemo-Resistance and Radio-Resistance of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Cells by Influencing Cell Cycle and Activating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling Pathway. J. Transl. Med. 2022, 20, 264. [CrossRef]

- Bi, L.; Wang, H.; Tian, Y. Silencing FAM135B Enhances Radiosensitivity of Esophageal Carcinoma Cell. Gene 2021, 772, 145358. [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Yang, S.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Qiu, H.; Sun, J.; Song, J.; Shi, L. The Adenosine-A2a Receptor Regulates the Radioresistance of Gastric Cancer via PI3K-AKT-mTOR Pathway. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 27, 911–920. [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, T.; Wang, M.; Mao, P. MiR-4524b-5p-Targeting ALDH1A3 Attenuates the Proliferation and Radioresistance of Glioblastoma via PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2024, 30, e14396. [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Cui, Y.; Hu, K.; Wang, X.; Yu, Y. Silencing APLNR Enhances the Radiosensitivity of Prostate Cancer by Modulating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling Pathway. Clin. Transl. Oncol. Off. Publ. Fed. Span. Oncol. Soc. Natl. Cancer Inst. Mex. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, L.; Tan, B.; Lei, X.; Zhang, B.; Li, W.; Liu, D.; Xia, T. SIRT6 through PI3K/Akt/mTOR Signaling Pathway to Enhance Radiosensitivity of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer and Inhibit Tumor Progression. IUBMB Life 2021, 73, 1092–1102. [CrossRef]

- Park, C.-M.; Park, M.-J.; Kwak, H.-J.; Lee, H.-C.; Kim, M.-S.; Lee, S.-H.; Park, I.-C.; Rhee, C.H.; Hong, S.-I. Ionizing Radiation Enhances Matrix Metalloproteinase-2 Secretion and Invasion of Glioma Cells through Src/Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor-Mediated P38/Akt and Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/Akt Signaling Pathways. Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 8511–8519. [CrossRef]

- Lan, Q.; Tan, X.; He, P.; Li, W.; Tian, S.; Dong, W. TRIM11 Promotes Proliferation, Migration, Invasion and EMT of Gastric Cancer by Activating β-Catenin Signaling. OncoTargets Ther. 2021, Volume 14, 1429–1440. [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Graham, P.H.; Hao, J.; Ni, J.; Bucci, J.; Cozzi, P.J.; Kearsley, J.H.; Li, Y. Acquisition of Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Cancer Stem Cell Phenotypes Is Associated with Activation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR Pathway in Prostate Cancer Radioresistance. Cell Death Dis. 2013, 4, e875. [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Cozzi, P.; Hao, J.; Beretov, J.; Chang, L.; Duan, W.; Shigdar, S.; Delprado, W.; Graham, P.; Bucci, J.; et al. Epithelial Cell Adhesion Molecule (EpCAM) Is Associated with Prostate Cancer Metastasis and Chemo/Radioresistance via the PI3K/Akt/mTOR Signaling Pathway. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2013, 45, 2736–2748. [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.-Q.; Miao, M.-C.; Ding, P.-A.; Tan, B.-B.; Liu, W.-B.; Guo, S.; Er, L.-M.; Zhang, Z.-D.; Zhao, Q. CALD1 Facilitates Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition Progression in Gastric Cancer Cells by Modulating the PI3K-Akt Pathway. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2024, 16, 1029–1045. [CrossRef]

- Beckers, C.; Pruschy, M.; Vetrugno, I. Tumor Hypoxia and Radiotherapy: A Major Driver of Resistance Even for Novel Radiotherapy Modalities. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2024, 98, 19–30. [CrossRef]

- Basheeruddin, M.; Qausain, S. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1-Alpha (HIF-1α): An Essential Regulator in Cellular Metabolic Control. Cureus 2024, 16, e63852. [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.M.; Li, C.; Hughes, J.R.; Rocha, S.; Grundy, G.J.; Parsons, J.L. Autophagy Is the Main Driver of Radioresistance of HNSCC Cells in Mild Hypoxia. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2024, 28, e18482. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Chen, K.; Lin, G.; Wan, F.; Chen, L.; Zhu, X. Silencing C-Jun Inhibits Autophagy and Abrogates Radioresistance in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma by Activating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 1085. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T.-Z.; Lin, H.-Y.; Kuei, C.-H.; Lin, C.-H.; Lee, H.-H.; Lee, H.-L.; Lu, H.-W.; Su, C.-Y.; Chiu, H.-W.; Lin, Y.-F. NEDD8 Promotes Radioresistance via Triggering Autophagy Formation and Serves as a Novel Prognostic Marker in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Cell Int. 2023, 23, 41. [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Min, W.; Lin, S.; Song, L.; Yang, P.; Ma, Q.; Guo, J. Saikosaponin-d Increases Radiation-Induced Apoptosis of Hepatoma Cells by Promoting Autophagy via Inhibiting mTOR Phosphorylation. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 18, 1465–1473. [CrossRef]

- Karami Fath, M.; Ebrahimi, M.; Nourbakhsh, E.; Zia Hazara, A.; Mirzaei, A.; Shafieyari, S.; Salehi, A.; Hoseinzadeh, M.; Payandeh, Z.; Barati, G. PI3K/Akt/mTOR Signaling Pathway in Cancer Stem Cells. Pathol. Res. Pract. 2022, 237, 154010. [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, T.; Steiner, R.; Lengerke, C. SOX2 and P53 Expression Control Converges in PI3K/AKT Signaling with Versatile Implications for Stemness and Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4902. [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-H.; Kim, Y.-H.; Shim, S.; Kim, A.; Jang, H.; Lee, S.-J.; Park, S.; Seo, S.; Jang, W.I.; Lee, S.B.; et al. Radiation-Activated PI3K/AKT Pathway Promotes the Induction of Cancer Stem-like Cells via the Upregulation of SOX2 in Colorectal Cancer. Cells 2021, 10, 135. [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Chen, W.-B.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Kang, X.-N.; Jin, L.-J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.-Y. HIF-2α Regulates CD44 to Promote Cancer Stem Cell Activation in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer via PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling. World J. Stem Cells 2020, 12, 87–99. [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Graham, P.H.; Hao, J.; Ni, J.; Bucci, J.; Cozzi, P.J.; Kearsley, J.H.; Li, Y. Acquisition of Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Cancer Stem Cell Phenotypes Is Associated with Activation of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR Pathway in Prostate Cancer Radioresistance. Cell Death Dis. 2013, 4, e875. [CrossRef]

- Bilanges, B.; Posor, Y.; Vanhaesebroeck, B. PI3K Isoforms in Cell Signalling and Vesicle Trafficking. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 515–534. [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Lin, X.; Hu, H. Regulation of PI3K Signaling in Cancer Metabolism and PI3K-Targeting Therapy. Transl. Breast Cancer Res. J. Focus. Transl. Res. Breast Cancer 2024, 5, 33. [CrossRef]

- Vasan, N.; Cantley, L.C. At a Crossroads: How to Translate the Roles of PI3K in Oncogenic and Metabolic Signalling into Improvements in Cancer Therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 19, 471–485. [CrossRef]

- Danyaei, A.; Ghanbarnasab-Behbahani, R.; Teimoori, A.; Neisi, N.; Chegeni, N. The Simultaneous Use of CRISPR/Cas9 to Knock out the PI3Kca Gene with Radiation to Enhance Radiosensitivity and Inhibit Tumor Growth in Breast Cancer. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2024, 27, 1566–1573. [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.-J.; Xing, H.; Wang, Y.-X.; Zhang, X.; Zhan, Q.-M.; Geng, M.-Y.; Ding, J.; Meng, L.-H. PI3Kα Inhibitors Sensitize Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma to Radiation by Abrogating Survival Signals in Tumor Cells and Tumor Microenvironment. Cancer Lett. 2019, 459, 145–155. [CrossRef]

- Korovina, I.; Elser, M.; Borodins, O.; Seifert, M.; Willers, H.; Cordes, N. Β1 Integrin Mediates Unresponsiveness to PI3Kα Inhibition for Radiochemosensitization of 3D HNSCC Models. Biomed. Pharmacother. Biomedecine Pharmacother. 2024, 171, 116217. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Gu, D.; Cai, L.; Yang, H.; Sheng, R. Development of Small-Molecule Inhibitors That Target PI3Kβ. Drug Discov. Today 2024, 29, 103854. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Fernandez-Capetillo, O.; Carrera, A.C. Nuclear Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase Beta Controls Double-Strand Break DNA Repair. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010, 107, 7491–7496. [CrossRef]

- Redondo-Muñoz, J.; Rodríguez, M.J.; Silió, V.; Pérez-García, V.; Valpuesta, J.M.; Carrera, A.C. Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase Beta Controls Replication Factor C Assembly and Function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, 855–868. [CrossRef]

- Marqués, M.; Kumar, A.; Poveda, A.M.; Zuluaga, S.; Hernández, C.; Jackson, S.; Pasero, P.; Carrera, A.C. Specific Function of Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase Beta in the Control of DNA Replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009, 106, 7525–7530. [CrossRef]

- Aytenfisu, T.Y.; Campbell, H.M.; Chakrabarti, M.; Amzel, L.M.; Gabelli, S.B. Class I PI3K Biology. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2022, 436, 3–49. [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.N.; Demetriou, C.; Valenzano, G.; Evans, A.; Go, S.; Stanly, T.; Hazini, A.; Willenbrock, F.; Gordon-Weeks, A.N.; Mukherjee, S.; et al. Induction of Macrophage Efferocytosis in Pancreatic Cancer via PI3Kγ Inhibition and Radiotherapy Promotes Tumour Control. Gut 2025, gutjnl-2024-333492. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.N.; Lee, E.; Kwon, Y.-J.; Gim, J.-A.; Kim, T.-J.; Kim, J.-S. PI3Kδ/γ Inhibitor BR101801 Extrinsically Potentiates Effector CD8+ T Cell-Dependent Antitumor Immunity and Abscopal Effect after Local Irradiation. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e003762. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Q.; Dong, S.; Li, X.-H. A Review of Phosphocreatine 3 Kinase δ Subtype (PI3Kδ) and Its Inhibitors in Malignancy. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2021, 27, e932772. [CrossRef]

- Yazdimamaghani, M.; Kolupaev, O.V.; Lim, C.; Hwang, D.; Laurie, S.J.; Perou, C.M.; Kabanov, A.V.; Serody, J.S. Tumor Microenvironment Immunomodulation by Nanoformulated TLR 7/8 Agonist and PI3k Delta Inhibitor Enhances Therapeutic Benefits of Radiotherapy. Biomaterials 2025, 312, 122750. [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.I.; Han, M.G.; Kang, M.H.; Park, J.M.; Kim, E.E.; Bae, J.; Ahn, S.; Kim, I.A. PI3Kαδ Inhibitor Combined with Radiation Enhances the Antitumor Immune Effect of Anti-PD1 in a Syngeneic Murine Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Model. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2021, 110, 845–858. [CrossRef]

- Modi, P.; Balakrishnan, K.; Yang, Q.; Wierda, W.G.; Keating, M.J.; Gandhi, V. Idelalisib and Bendamustine Combination Is Synergistic and Increases DNA Damage Response in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Cells. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 16259–16274. [CrossRef]

- Gryc, T.; Putz, F.; Goerig, N.; Ziegler, S.; Fietkau, R.; Distel, L.V.; Schuster, B. Idelalisib May Have the Potential to Increase Radiotherapy Side Effects. Radiat. Oncol. Lond. Engl. 2017, 12, 109. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.S.; Xu, P.-Z.; Gottlob, K.; Chen, M.-L.; Sokol, K.; Shiyanova, T.; Roninson, I.; Weng, W.; Suzuki, R.; Tobe, K.; et al. Growth Retardation and Increased Apoptosis in Mice with Homozygous Disruption of the Akt1 Gene. Genes Dev. 2001, 15, 2203–2208. [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Mu, J.; Kim, J.K.; Thorvaldsen, J.L.; Chu, Q.; Crenshaw, E.B.; Kaestner, K.H.; Bartolomei, M.S.; Shulman, G.I.; Birnbaum, M.J. Insulin Resistance and a Diabetes Mellitus-like Syndrome in Mice Lacking the Protein Kinase Akt2 (PKBβ). Science 2001, 292, 1728–1731. [CrossRef]

- Tschopp, O.; Yang, Z.-Z.; Brodbeck, D.; Dummler, B.A.; Hemmings-Mieszczak, M.; Watanabe, T.; Michaelis, T.; Frahm, J.; Hemmings, B.A. Essential Role of Protein Kinase Bγ (PKBγ/Akt3) in Postnatal Brain Development but Not in Glucose Homeostasis. Development 2005, 132, 2943–2954. [CrossRef]

- Degan, S.E.; Gelman, I.H. Emerging Roles for AKT Isoform Preference in Cancer Progression Pathways. Mol. Cancer Res. MCR 2021, 19, 1251–1257. [CrossRef]

- Toulany, M.; Kehlbach, R.; Florczak, U.; Sak, A.; Wang, S.; Chen, J.; Lobrich, M.; Rodemann, H.P. Targeting of AKT1 Enhances Radiation Toxicity of Human Tumor Cells by Inhibiting DNA-PKcs-Dependent DNA Double-Strand Break Repair. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2008, 7, 1772–1781. [CrossRef]

- Toulany, M.; Lee, K.-J.; Fattah, K.R.; Lin, Y.-F.; Fehrenbacher, B.; Schaller, M.; Chen, B.P.; Chen, D.J.; Rodemann, H.P. Akt Promotes Post-Irradiation Survival of Human Tumor Cells through Initiation, Progression, and Termination of DNA-PKcs-Dependent DNA Double-Strand Break Repair. Mol. Cancer Res. MCR 2012, 10, 945–957. [CrossRef]

- Toulany, M.; Maier, J.; Iida, M.; Rebholz, S.; Holler, M.; Grottke, A.; Jüker, M.; Wheeler, D.L.; Rothbauer, U.; Rodemann, H.P. Akt1 and Akt3 but Not Akt2 through Interaction with DNA-PKcs Stimulate Proliferation and Post-Irradiation Cell Survival of K-RAS-Mutated Cancer Cells. Cell Death Discov. 2017, 3, 17072. [CrossRef]

- Toulany, M.; Iida, M.; Lettau, K.; Coan, J.P.; Rebholz, S.; Khozooei, S.; Harari, P.M.; Wheeler, D.L. Targeting HER3-Dependent Activation of Nuclear AKT Improves Radiotherapy of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Radiother. Oncol. J. Eur. Soc. Ther. Radiol. Oncol. 2022, 174, 92–100. [CrossRef]

- Szymonowicz, K.; Oeck, S.; Krysztofiak, A.; van der Linden, J.; Iliakis, G.; Jendrossek, V. Restraining Akt1 Phosphorylation Attenuates the Repair of Radiation-Induced DNA Double-Strand Breaks and Reduces the Survival of Irradiated Cancer Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2233. [CrossRef]

- Mueck, K.; Rebholz, S.; Harati, M.D.; Rodemann, H.P.; Toulany, M. Akt1 Stimulates Homologous Recombination Repair of DNA Double-Strand Breaks in a Rad51-Dependent Manner. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 2473. [CrossRef]

- Oeck, S.; Al-Refae, K.; Riffkin, H.; Wiel, G.; Handrick, R.; Klein, D.; Iliakis, G.; Jendrossek, V. Activating Akt1 Mutations Alter DNA Double Strand Break Repair and Radiosensitivity. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42700. [CrossRef]

- Seiwert, N.; Neitzel, C.; Stroh, S.; Frisan, T.; Audebert, M.; Toulany, M.; Kaina, B.; Fahrer, J. AKT2 Suppresses Pro-Survival Autophagy Triggered by DNA Double-Strand Breaks in Colorectal Cancer Cells. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e3019. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadian Gol, T.; Rodemann, H.P.; Dittmann, K. Depletion of Akt1 and Akt2 Impairs the Repair of Radiation-Induced DNA Double Strand Breaks via Homologous Recombination. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 6316. [CrossRef]

- Sahlberg, S.H.; Gustafsson, A.-S.; Pendekanti, P.N.; Glimelius, B.; Stenerlöw, B. The Influence of AKT Isoforms on Radiation Sensitivity and DNA Repair in Colon Cancer Cell Lines. Tumor Biol. 2014, 35, 3525–3534. [CrossRef]

- Tan, P. -x; Du, S. -s; Ren, C.; Yao, Q. -w; Zheng, R.; Li, R.; Yuan, Y. -w MicroRNA-207 Enhances Radiation-Induced Apoptosis by Directly Targeting Akt3 in Cochlea Hair Cells. Cell Death Dis. 2014, 5, e1433. [CrossRef]

- Polytarchou, C.; Hatziapostolou, M.; Yau, T.O.; Christodoulou, N.; Hinds, P.W.; Kottakis, F.; Sanidas, I.; Tsichlis, P.N. Akt3 Induces Oxidative Stress and DNA Damage by Activating the NADPH Oxidase via Phosphorylation of P47phox. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020, 117, 28806–28815. [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wu, A.; Qi, D.; Cui, F.; Zeng, Y.; Xie, F.; Wu, H.; Gu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, X. Differential Effects of Peptidoglycan on Colorectal Tumors and Intestinal Tissue Post-Pelvic Radiotherapy. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 75685–75697. [CrossRef]

- Turner, K.M.; Sun, Y.; Ji, P.; Granberg, K.J.; Bernard, B.; Hu, L.; Cogdell, D.E.; Zhou, X.; Yli-Harja, O.; Nykter, M.; et al. Genomically Amplified Akt3 Activates DNA Repair Pathway and Promotes Glioma Progression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015, 112, 3421–3426. [CrossRef]

- Saxton, R.A.; Sabatini, D.M. mTOR Signaling in Growth, Metabolism, and Disease. Cell 2017, 169, 361–371. [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.Y.; Sabatini, D.M. mTOR at the Nexus of Nutrition, Growth, Ageing and Disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 183–203. [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Xing, S.; Wu, Z.; Chen, F.; Pan, X.; Li, Q.; Liu, W.; Zhang, G. Leucine Restriction Ameliorates Fusobacterium Nucleatum-Driven Malignant Progression and Radioresistance in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Cell Rep. Med. 2024, 5, 101753. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Cao, Z.; Yue, X.; Liu, T.; Wen, G.; Jiang, D.; Wu, W.; Le, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, C.; et al. Stabilization of DEPTOR Sensitizes Hypopharyngeal Cancer to Radiotherapy via Targeting Degradation. Mol. Ther. - Oncolytics 2022, 26, 330–346. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Vassetzky, Y.; Dokudovskaya, S. mTORC1 Pathway in DNA Damage Response. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2018, 1865, 1293–1311. [CrossRef]

- Holler, M.; Grottke, A.; Mueck, K.; Manes, J.; Jücker, M.; Rodemann, H.P.; Toulany, M. Dual Targeting of Akt and mTORC1 Impairs Repair of DNA Double-Strand Breaks and Increases Radiation Sensitivity of Human Tumor Cells. PLOS One 2016, 11, e0154745. [CrossRef]

- Murata, Y.; Uehara, Y.; Hosoi, Y. Activation of mTORC1 under Nutrient Starvation Conditions Increases Cellular Radiosensitivity in Human Liver Cancer Cell Lines, HepG2 and HuH6. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 468, 684–690. [CrossRef]

- Mir, S.A.; Dar, A.; Alshehri, S.A.; Wahab, S.; Hamid, L.; Almoyad, M.A.A.; Ali, T.; Bader, G.N. Exploring the mTOR Signalling Pathway and Its Inhibitory Scope in Cancer. Pharm. Basel Switz. 2023, 16, 1004. [CrossRef]

- Kalpongnukul, N.; Bootsri, R.; Wongkongkathep, P.; Kaewsapsak, P.; Ariyachet, C.; Pisitkun, T.; Chantaravisoot, N. Phosphoproteomic Analysis Defines BABAM1 as mTORC2 Downstream Effector Promoting DNA Damage Response in Glioblastoma Cells. J. Proteome Res. 2022, 21, 2893–2904. [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Chen, C.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, F.; Mi, J.; Feng, Q.; Lin, S.; Xi, N.; Tian, J.; Yu, L.; et al. mTORC2 Regulates Ribonucleotide Reductase to Promote DNA Replication and Gemcitabine Resistance in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Neoplasia N. Y. N 2021, 23, 643–652. [CrossRef]

- Miyahara, H.; Yadavilli, S.; Natsumeda, M.; Rubens, J.A.; Rodgers, L.; Kambhampati, M.; Taylor, I.C.; Kaur, H.; Asnaghi, L.; Eberhart, C.G.; et al. The Dual mTOR Kinase Inhibitor TAK228 Inhibits Tumorigenicity and Enhances Radiosensitization in Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma. Cancer Lett. 2017, 400, 110–116. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.-G.; Tang, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, H.; Yang, J.; Zhang, H. The Novel mTORC1/2 Dual Inhibitor INK128 Enhances Radiosensitivity of Breast Cancer Cell Line MCF-7. Int. J. Oncol. 2016, 49, 1039–1045. [CrossRef]

- Kahn, J.; Hayman, T.J.; Jamal, M.; Rath, B.H.; Kramp, T.; Camphausen, K.; Tofilon, P.J. The mTORC1/mTORC2 Inhibitor AZD2014 Enhances the Radiosensitivity of Glioblastoma Stem-like Cells. Neuro-Oncol. 2014, 16, 29–37. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; An, J.; He, S.; Liao, C.; Wang, J.; Tuo, B. Chloride Intracellular Channels as Novel Biomarkers for Digestive System Tumors (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 2021, 24, 630. [CrossRef]

- Shiratori, H.; Kawai, K.; Hata, K.; Tanaka, T.; Nishikawa, T.; Otani, K.; Sasaki, K.; Kaneko, M.; Murono, K.; Emoto, S.; et al. The Combination of Temsirolimus and Chloroquine Increases Radiosensitivity in Colorectal Cancer Cells. Oncol. Rep. 2019, 42, 377–385. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-H.; Wang, C.-W.; Wei, M.-F.; Tzeng, Y.-S.; Lan, K.-H.; Cheng, A.-L.; Kuo, S.-H. Maintenance BEZ235 Treatment Prolongs the Therapeutic Effect of the Combination of BEZ235 and Radiotherapy for Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2019, 11, 1204. [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Li, A.; Sun, C.; Li, R.; Xing, Y.; Shi, M.; Wang, Q. PKI-587 Enhances Radiosensitization of Hepatocellular Carcinoma by Inhibiting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathways and DNA Damage Repair. PLOS One 2021, 16, e0258817. [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Ruan, J.; Zhu, H.; Chen, Z.; Chen, J.; Yu, H. Tenacissoside H Induces Autophagy and Radiosensitivity of Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells by PI3K/Akt/mTOR Signaling Pathway. Dose-Response Publ. Int. Hormesis Soc. 2021, 19, 15593258211011023. [CrossRef]

- Chow, Z.; Johnson, J.; Chauhan, A.; Izumi, T.; Cavnar, M.; Weiss, H.; Townsend, C.M.; Anthony, L.; Wasilchenko, C.; Melton, M.L.; et al. PI3K/mTOR Dual Inhibitor PF-04691502 Is a Schedule-Dependent Radiosensitizer for Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. Cells 2021, 10, 1261. [CrossRef]

- Hayman, T.J.; Wahba, A.; Rath, B.H.; Bae, H.; Kramp, T.; Shankavaram, U.T.; Camphausen, K.; Tofilon, P.J. The ATP-Competitive mTOR Inhibitor INK128 Enhances in Vitro and in Vivo Radiosensitivity of Pancreatic Carcinoma Cells. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 110–119. [CrossRef]

- Murgić, J.; Fröbe, A.; Kiang Chua, M.L. RECENT ADVANCES IN RADIOTHERAPY MODALITIES FOR PROSTATE CANCER. Acta Clin. Croat. 2022, 61, 57–64. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Fu, W.; Hu, L. NVP-BEZ235, Dual Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Inhibitor, Prominently Enhances Radiosensitivity of Prostate Cancer Cell Line PC-3. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2013, 28, 665–673. [CrossRef]

- Rachamala, H.K.; Madamsetty, V.S.; Angom, R.S.; Nakka, N.M.; Dutta, S.K.; Wang, E.; Mukhopadhyay, D.; Pal, K. Targeting mTOR and Survivin Concurrently Potentiates Radiation Therapy in Renal Cell Carcinoma by Suppressing DNA Damage Repair and Amplifying Mitotic Catastrophe. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. CR 2024, 43, 159. [CrossRef]

- Tayyar, Y.; Idris, A.; Vidimce, J.; Ferreira, D.A.; McMillan, N.A. Alpelisib and Radiotherapy Treatment Enhances Alisertib-Mediated Cervical Cancer Tumor Killing. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2021, 11, 3240–3251.

- Nassim, R.; Mansure, J.J.; Chevalier, S.; Cury, F.; Kassouf, W. Combining mTOR Inhibition with Radiation Improves Antitumor Activity in Bladder Cancer Cells in Vitro and in Vivo: A Novel Strategy for Treatment. PLOS One 2013, 8, e65257. [CrossRef]

- Vinod, S.K.; Hau, E. Radiotherapy Treatment for Lung Cancer: Current Status and Future Directions. Respirol. Carlton Vic 2020, 25 Suppl 2, 61–71. [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Hang, Q.; Li, P.; Zhang, P.; Ji, J.; Song, H.; Chen, M.; et al. PI3K/mTOR Inhibitors Promote G6PD Autophagic Degradation and Exacerbate Oxidative Stress Damage to Radiosensitize Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2023, 14, 652. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Jeong, E.-H.; Lee, T.-G.; Kim, H.-R.; Kim, C.H. The Combination of Trametinib, a MEK Inhibitor, and Temsirolimus, an mTOR Inhibitor, Radiosensitizes Lung Cancer Cells. Anticancer Res. 2021, 41, 2885–2894. [CrossRef]

- Seol, M.Y.; Choi, S.H.; Yoon, H.I. Combining Radiation with PI3K Isoform-Selective Inhibitor Administration Increases Radiosensitivity and Suppresses Tumor Growth in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. J. Radiat. Res. (Tokyo) 2022, 63, 591–601. [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.-C.; Lee, W.-C.; Wang, C.-C.; Yeh, S.-A.; Chen, W.-H.; Chen, P.-J. Targeting PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling Pathway as a Radiosensitization in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinomas. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15749. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Du, K.; Liu, Z.; Li, J. Inhibition of mTOR by Temsirolimus Overcomes Radio-Resistance in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2022, 49, 703–709. [CrossRef]

- Klieber, N.; Hildebrand, L.S.; Faulhaber, E.; Symank, J.; Häck, N.; Härtl, A.; Fietkau, R.; Distel, L.V. Different Impacts of DNA-PK and mTOR Kinase Inhibitors in Combination with Ionizing Radiation on HNSCC and Normal Tissue Cells. Cells 2024, 13, 304. [CrossRef]

- Glorieux, M.; Dok, R.; Nuyts, S. The Influence of PI3K Inhibition on the Radiotherapy Response of Head and Neck Cancer Cells. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16208. [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, R.; Bazan, J.G. Advances in Radiotherapy for Breast Cancer. Surg. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2023, 32, 515–536. [CrossRef]

- Kempska, J.; Oliveira-Ferrer, L.; Grottke, A.; Qi, M.; Alawi, M.; Meyer, F.; Borgmann, K.; Hamester, F.; Eylmann, K.; Rossberg, M.; et al. Impact of AKT1 on Cell Invasion and Radiosensitivity in a Triple Negative Breast Cancer Cell Line Developing Brain Metastasis. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1129682. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.; Chow, Z.; Napier, D.; Lee, E.; Weiss, H.L.; Evers, B.M.; Rychahou, P. Targeting PI3K and AMPKα Signaling Alone or in Combination to Enhance Radiosensitivity of Triple Negative Breast Cancer. Cells 2020, 9, 1253. [CrossRef]

- Gasimli, R.; Kayabasi, C.; Ozmen Yelken, B.; Asik, A.; Sogutlu, F.; Celebi, C.; Yilmaz Susluer, S.; Kamer, S.; Biray Avci, C.; Haydaroglu, A.; et al. The Effects of PKI-402 on Breast Tumor Models’ Radiosensitivity via Dual Inhibition of PI3K/mTOR. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2023, 99, 1961–1970. [CrossRef]

- Masoumi, H.; Soltani, A.; Ghatrehsamani, M. The Beneficial Role of SIRT1 Activator on Chemo- and Radiosensitization of Breast Cancer Cells in Response to IL-6. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 129–139. [CrossRef]

- Janjua, T.I.; Rewatkar, P.; Ahmed-Cox, A.; Saeed, I.; Mansfeld, F.M.; Kulshreshtha, R.; Kumeria, T.; Ziegler, D.S.; Kavallaris, M.; Mazzieri, R.; et al. Frontiers in the Treatment of Glioblastoma: Past, Present and Emerging. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 171, 108–138. [CrossRef]

- Seol, M.Y.; Choi, S.H.; Lee, I.J.; Park, H.S.; Kim, H.R.; Kim, S.K.; Yoon, H.I. Selective Inhibition of PI3K Isoforms in Brain Tumors Suppresses Tumor Growth by Increasing Radiosensitivity. Yonsei Med. J. 2023, 64, 139–147. [CrossRef]

- Djuzenova, C.S.; Fischer, T.; Katzer, A.; Sisario, D.; Korsa, T.; Steussloff, G.; Sukhorukov, V.L.; Flentje, M. Opposite Effects of the Triple Target (DNA-PK/PI3K/mTOR) Inhibitor PI-103 on the Radiation Sensitivity of Glioblastoma Cell Lines Proficient and Deficient in DNA-PKcs. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 1201. [CrossRef]

- Djuzenova, C.S.; Fiedler, V.; Memmel, S.; Katzer, A.; Sisario, D.; Brosch, P.K.; Göhrung, A.; Frister, S.; Zimmermann, H.; Flentje, M.; et al. Differential Effects of the Akt Inhibitor MK-2206 on Migration and Radiation Sensitivity of Glioblastoma Cells. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 299. [CrossRef]

- Luboff, A.J.; DeRemer, D.L. Capivasertib: A Novel AKT Inhibitor Approved for Hormone-Receptor-Positive, HER-2-Negative Metastatic Breast Cancer. Ann. Pharmacother. 2024, 58, 1229–1237. [CrossRef]

- Day, D.; Prawira, A.; Spreafico, A.; Waldron, J.; Karithanam, R.; Giuliani, M.; Weinreb, I.; Kim, J.; Cho, J.; Hope, A.; et al. Phase I Trial of Alpelisib in Combination with Concurrent Cisplatin-Based Chemoradiotherapy in Patients with Locoregionally Advanced Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. Oral Oncol. 2020, 108, 104753. [CrossRef]

- Dunn, L.A.; Riaz, N.; Fury, M.G.; McBride, S.M.; Michel, L.; Lee, N.Y.; Sherman, E.J.; Baxi, S.S.; Haque, S.S.; Katabi, N.; et al. A Phase 1b Study of Cetuximab and BYL719 (Alpelisib) Concurrent with Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy in Stage III-IVB Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2020, 106, 564–570. [CrossRef]

- McGowan, D.R.; Skwarski, M.; Bradley, K.M.; Campo, L.; Fenwick, J.D.; Gleeson, F.V.; Green, M.; Horne, A.; Maughan, T.S.; McCole, M.G.; et al. Buparlisib with Thoracic Radiotherapy and Its Effect on Tumour Hypoxia: A Phase I Study in Patients with Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Carcinoma. Eur. J. Cancer Oxf. Engl. 1990 2019, 113, 87–95. [CrossRef]

- Wen, P.Y.; Rodon, J.A.; Mason, W.; Beck, J.T.; DeGroot, J.; Donnet, V.; Mills, D.; El-Hashimy, M.; Rosenthal, M. Phase I, Open-Label, Multicentre Study of Buparlisib in Combination with Temozolomide or with Concomitant Radiation Therapy and Temozolomide in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Glioblastoma. ESMO Open 2020, 5, e000673. [CrossRef]

- Wen, P.Y.; Omuro, A.; Ahluwalia, M.S.; Fathallah-Shaykh, H.M.; Mohile, N.; Lager, J.J.; Laird, A.D.; Tang, J.; Jiang, J.; Egile, C.; et al. Phase I Dose-Escalation Study of the PI3K/mTOR Inhibitor Voxtalisib (SAR245409, XL765) plus Temozolomide with or without Radiotherapy in Patients with High-Grade Glioma. Neuro-Oncol. 2015, 17, 1275–1283. [CrossRef]

- Gills, J.J.; Dennis, P.A. Perifosine: Update on a Novel Akt Inhibitor. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2009, 11, 102–110. [CrossRef]

- Vink, S.R.; Schellens, J.H.M.; Beijnen, J.H.; Sindermann, H.; Engel, J.; Dubbelman, R.; Moppi, G.; Hillebrand, M.J.X.; Bartelink, H.; Verheij, M. Phase I and Pharmacokinetic Study of Combined Treatment with Perifosine and Radiation in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumours. Radiother. Oncol. J. Eur. Soc. Ther. Radiol. Oncol. 2006, 80, 207–213. [CrossRef]

- Goda, J.; Pachpor, T.; Basu, T.; Chopra, S.; Gota, V. Targeting the AKT Pathway: Repositioning HIV Protease Inhibitors as Radiosensitizers. Indian J. Med. Res. 2016, 143, 145. [CrossRef]

- Buijsen, J.; Lammering, G.; Jansen, R.L.H.; Beets, G.L.; Wals, J.; Sosef, M.; Den Boer, M.O.; Leijtens, J.; Riedl, R.G.; Theys, J.; et al. Phase I Trial of the Combination of the Akt Inhibitor Nelfinavir and Chemoradiation for Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer. Radiother. Oncol. J. Eur. Soc. Ther. Radiol. Oncol. 2013, 107, 184–188. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Soto, A.E.; McKenzie, N.D.; Whicker, M.E.; Pearson, J.M.; Jimenez, E.A.; Portelance, L.; Hu, J.J.; Lucci, J.A.; Qureshi, R.; Kossenkov, A.; et al. Phase 1 Trial of Nelfinavir Added to Standard Cisplatin Chemotherapy with Concurrent Pelvic Radiation for Locally Advanced Cervical Cancer. Cancer 2021, 127, 2279–2293. [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Verma, V.; Lazenby, A.; Ly, Q.P.; Berim, L.D.; Schwarz, J.K.; Madiyalakan, M.; Nicodemus, C.F.; Hollingsworth, M.A.; Meza, J.L.; et al. Phase I/II Trial of Neoadjuvant Oregovomab-Based Chemoimmunotherapy Followed by Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy and Nelfinavir for Locally Advanced Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 42, 755–760. [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Qi, C.; Shaw, R.; Jones, C.M.; Bridgewater, J.A.; Radhakrishna, G.; Patel, N.; Holmes, J.; Virdee, P.S.; Tranter, B.; et al. Standard or High Dose Chemoradiotherapy, with or without the Protease Inhibitor Nelfinavir, in Patients with Locally Advanced Pancreatic Cancer: The Phase 1/Randomised Phase 2 SCALOP-2 Trial. Eur. J. Cancer Oxf. Engl. 1990 2024, 209, 114236. [CrossRef]

- Waqar, S.N.; Robinson, C.; Bradley, J.; Goodgame, B.; Rooney, M.; Williams, K.; Gao, F.; Govindan, R. A Phase I Study of Temsirolimus and Thoracic Radiation in Non--Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Clin. Lung Cancer 2014, 15, 119–123. [CrossRef]

- Wick, W.; Gorlia, T.; Bady, P.; Platten, M.; van den Bent, M.J.; Taphoorn, M.J.B.; Steuve, J.; Brandes, A.A.; Hamou, M.-F.; Wick, A.; et al. Phase II Study of Radiotherapy and Temsirolimus versus Radiochemotherapy with Temozolomide in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Glioblastoma without MGMT Promoter Hypermethylation (EORTC 26082). Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 4797–4806. [CrossRef]

- Saba, N.F.; Force, S.; Staley, C.; Fernandez, F.; Willingham, F.; Pickens, A.; Cardona, K.; Chen, Z.; Goff, L.; Cardin, D.; et al. Phase IB Study of Induction Chemotherapy with XELOX, Followed by Radiation Therapy, Carboplatin, and Everolimus in Patients with Locally Advanced Esophageal Cancer. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 42, 331–336. [CrossRef]

- de Melo, A.C.; Grazziotin-Reisner, R.; Erlich, F.; Fontes Dias, M.S.; Moralez, G.; Carneiro, M.; Ingles Garces, Á.H.; Guerra Alves, F.V.; Novaes Neto, B.; Fuchshuber-Moraes, M.; et al. A Phase I Study of mTOR Inhibitor Everolimus in Association with Cisplatin and Radiotherapy for the Treatment of Locally Advanced Cervix Cancer: PHOENIX I. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2016, 78, 101–109. [CrossRef]

- Chinnaiyan, P.; Won, M.; Wen, P.Y.; Rojiani, A.M.; Werner-Wasik, M.; Shih, H.A.; Ashby, L.S.; Michael Yu, H.-H.; Stieber, V.W.; Malone, S.C.; et al. A Randomized Phase II Study of Everolimus in Combination with Chemoradiation in Newly Diagnosed Glioblastoma: Results of NRG Oncology RTOG 0913. Neuro-Oncol. 2018, 20, 666–673. [CrossRef]

- Narayan, V.; Vapiwala, N.; Mick, R.; Subramanian, P.; Christodouleas, J.P.; Bekelman, J.E.; Deville, C.; Rajendran, R.; Haas, N.B. Phase 1 Trial of Everolimus and Radiation Therapy for Salvage Treatment of Biochemical Recurrence in Prostate Cancer Patients Following Prostatectomy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2017, 97, 355–361. [CrossRef]

- Curigliano, G.; Shah, R.R. Safety and Tolerability of Phosphatidylinositol-3-Kinase (PI3K) Inhibitors in Oncology. Drug Saf. 2019, 42, 247–262. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, X.; Yang, K.; Wang, S.; Zhang, T.; Hui, F.; Zheng, F.; Geng, H.; Xu, C.; Xun, F.; et al. The Efficacy and Safety of PI3K and AKT Inhibitors for Patients with Cancer: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 983, 176952. [CrossRef]

- Savas, P.; Lo, L.L.; Luen, S.J.; Blackley, E.F.; Callahan, J.; Moodie, K.; van Geelen, C.T.; Ko, Y.-A.; Weng, C.-F.; Wein, L.; et al. Alpelisib Monotherapy for PI3K-Altered, Pretreated Advanced Breast Cancer: A Phase II Study. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 2058–2073. [CrossRef]

- Sarker, D.; Dawson, N.A.; Aparicio, A.M.; Dorff, T.B.; Pantuck, A.J.; Vaishampayan, U.N.; Henson, L.; Vasist, L.; Roy-Ghanta, S.; Gorczyca, M.; et al. A Phase I, Open-Label, Dose-Finding Study of GSK2636771, a PI3Kβ Inhibitor, Administered with Enzalutamide in Patients with Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 5248–5257. [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.; Mangaonkar, A. Idelalisib: A Novel PI3Kδ Inhibitor for Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Ann. Pharmacother. 2015, 49, 1162–1170. [CrossRef]

- Goto, H.; Izutsu, K.; Ennishi, D.; Mishima, Y.; Makita, S.; Kato, K.; Hanaya, M.; Hirano, S.; Narushima, K.; Teshima, T.; et al. Zandelisib (ME-401) in Japanese Patients with Relapsed or Refractory Indolent Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma: An Open-Label, Multicenter, Dose-Escalation Phase 1 Study. Int. J. Hematol. 2022, 116, 911–921. [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.S.; Postow, M.; Chmielowski, B.; Sullivan, R.; Patnaik, A.; Cohen, E.E.W.; Shapiro, G.; Steuer, C.; Gutierrez, M.; Yeckes-Rodin, H.; et al. Eganelisib, a First-in-Class PI3Kγ Inhibitor, in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors: Results of the Phase 1/1b MARIO-1 Trial. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 2023, 29, 2210–2219. [CrossRef]

- Moein, A.; Jin, J.Y.; Wright, M.R.; Wong, H. Quantitative Assessment of Drug Efficacy and Emergence of Resistance in Patients with Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Using a Longitudinal Exposure-Tumor Growth Inhibition Model: Apitolisib (Dual PI3K/mTORC1/2 Inhibitor) versus Everolimus (mTORC1 Inhibitor). J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2024, 64, 1101–1111. [CrossRef]

- Kořánová, T.; Dvořáček, L.; Grebeňová, D.; Kuželová, K. JR-AB2-011 Induces Fast Metabolic Changes Independent of mTOR Complex 2 Inhibition in Human Leukemia Cells. Pharmacol. Rep. PR 2024, 76, 1390–1402. [CrossRef]

- Denduluri, S.K.; Idowu, O.; Wang, Z.; Liao, Z.; Yan, Z.; Mohammed, M.K.; Ye, J.; Wei, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhao, L.; et al. Insulin-like Growth Factor (IGF) Signaling in Tumorigenesis and the Development of Cancer Drug Resistance. Genes Dis. 2015, 2, 13–25. [CrossRef]

- De Vera, A.A.; Reznik, S.E. Combining PI3K/Akt/mTOR Inhibition with Chemotherapy. In Protein Kinase Inhibitors as Sensitizing Agents for Chemotherapy; Elsevier, 2019; pp. 229–242 ISBN 978-0-12-816435-8.

- Rallis, K.S.; Lai Yau, T.H.; Sideris, M. Chemoradiotherapy in Cancer Treatment: Rationale and Clinical Applications. Anticancer Res. 2021, 41, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Liu, S.; Zhao, S. Everolimus (RAD001) Combined with Programmed Death-1 (PD-1) Blockade Enhances Radiosensitivity of Cervical Cancer and Programmed Death-Ligand 1 (PD-L1) Expression by Blocking the Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase (PI3K)/Protein Kinase B (AKT)/Mammalian Target of Rapamycin (mTOR)/S6 Kinase 1 (S6K1) Pathway. Bioengineered 2022, 13, 11240–11257. [CrossRef]

- Bleaney, C.W.; Abdelaal, H.; Reardon, M.; Anandadas, C.; Hoskin, P.; Choudhury, A.; Forker, L. Clinical Biomarkers of Tumour Radiosensitivity and Predicting Benefit from Radiotherapy: A Systematic Review. Cancers 2024, 16, 1942. [CrossRef]

- Bamodu, O.A.; Chang, H.-L.; Ong, J.-R.; Lee, W.-H.; Yeh, C.-T.; Tsai, J.-T. Elevated PDK1 Expression Drives PI3K/AKT/MTOR Signaling Promotes Radiation-Resistant and Dedifferentiated Phenotype of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cells 2020, 9, 746. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zheng, W.; Zhu, L.; Yao, D.; Wang, C.; Song, Y.; Hu, S.; Liu, H.; Bai, Y.; Pan, Y.; et al. ANXA6 Contributes to Radioresistance by Promoting Autophagy via Inhibiting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR Signaling Pathway in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 232. [CrossRef]

| Inhibitor | Target | Population | Phase | ClinicalTrials.Gov Identifier |

| Alpelisib | PI3K | Head and Neck Squamous Cell Cancer | 1 | NCT02282371 Start date: October 2014 Completion date: October 2021 |

| PI3K | Head and Neck Cancer | 1 | NCT02537223 Start date: September 2015 Completion date: February 2020 | |

| Buparlisib | PI3K | Carcinoma, Non-Small-Cell Lung | 1 | NCT02128724 Start date: April 2013 Completion date: October 2017 |

| PI3K | Head and Neck Cancer | 1 | NCT02113878 Start date: September 2014 Completion date: January 2022 | |

| PI3K | Glioblastoma | 1 | NCT01473901 Start date: December 2011 Completion date: May 2017 | |

| Voxtalisib | PI3K/mTOR | Glioblastoma | 1 | NCT00704080 Start date: August 2008 Completion date: February 2013 |

| Paxalisib | PI3K/mTOR | Brain Metastases | 1 | NCT04192981 Start date: December 2019 Completion date: December 2025 |

| PI3K/mTOR | Diffuse Midline Gliomas | 2 | NCT05009992 Start date: October 2021 Completion date: June 2029 | |

| PI3K/mTOR | Glioblastoma | 2/3 | NCT03970447 Start date: July 2019 Completion date: June 2028 |

|

| Capivasertib | AKT | Breast Cancer | 2 | NCT06607757 Start date: December 2024 Completion date: August 2026 |

| Ipatasertib | AKT | Head and Neck Cancer | 1 | NCT05172245 Start date: September 2022 Completion date: June 2026 |

| Nelfinavir | AKT | Glioblastoma | 1 | NCT00694837 Start date: March 2009 Completion date: January 2013 |

| AKT | Oligometastases | 2 | NCT01728779 Start date: January 2014 Completion date: December 2020 | |

| AKT | Cervical Cancer | 1 | NCT01485731 Start date: January 2012 Completion date: February 2015 | |

| AKT | Pancreatic Cancer | 1 | NCT01068327 Start date: November 2007 Completion date: February 2015 | |

| AKT | Pancreatic Cancer | 2 | NCT01959672 Start date: September 2013 Completion date: December 2018 | |

| AKT | Glioblastoma | 1 | NCT01020292 Start date: April 2009 Completion date: December 2017 | |

| AKT | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer | 1/2 | NCT00589056 Start date: June 2007 Completion date: March 2012 | |

| AKT | Pancreatic Cancer | 1/2 | NCT00589056 Start date: March 2016 Completion date: June 2021 | |

| AKT | Cervical Cancer | 1 | NCT02363829 Start date: February 2015 Completion date: February 2020 | |

| AKT | Head and Neck Squamous Cell Cancer | 2 | NCT02207439 Start date: July 2014 Completion date: May 2022 | |

| Everolimus | mTOR | High Grade Glioma | 2 | NCT05843253 Start date: August 2024 Completion date: August 2034 |

| mTOR | Neuroendocrine Tumors | 3 | NCT05918302 Start date: October 2023 Completion date: July 2028 | |

| mTOR | Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma | 3 | NCT05476939 Start date: September 2022 Completion date: September 2031 | |

| mTOR | Glioblastoma | 1/2 | NCT00553150 Start date: March 2009 Completion date: November 2019 | |

| mTOR | Head and Neck Cancer | 1 | NCT00858663 Start date: March 2009 Completion date: July 2013 | |

| mTOR | Glioblastoma | 1/2 | NCT01062399 Start date: December 2010 Completion date: May 2022 | |

| mTOR | Cervix Cancer | 1 | NCT01217177 Start date: December 2011 Completion date: April 2014 | |

| Temsirolimus | mTOR | Rhabdomyosarcoma | 3 | NCT02567435 Start date: June 2016 Completion date: October 2025 |

| mTOR | Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma | 1 | NCT02420613 Start date: October 2015 Completion date: October 2024 | |

| mTOR | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer | 1 | NCT00796796 Start date: March 2009 Completion date: July 2011 | |

| mTOR | Glioblastoma | 1 | NCT00316849 Start date: May 2006 Completion date: November 2010 | |

| mTOR | Glioblastoma | 2 | NCT01019434 Start date: October 2009 Completion date: March 2014 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).