1. Introduction

Greenways offer transportation options, promote outdoor recreation and healthful living, catalyze economic revitalization, increase adjacent property values, celebrate history and culture, promote conservation and environmental education, expand ecotourism, increase cultural tourism, strengthen an outdoor recreational economy, and improve quality of life [

1,

2,

3]. Such trails provide better access to nature for more people [

4,

5] that, in turn, can help develop a stewardship ethic [

6,

7,

8,

9].

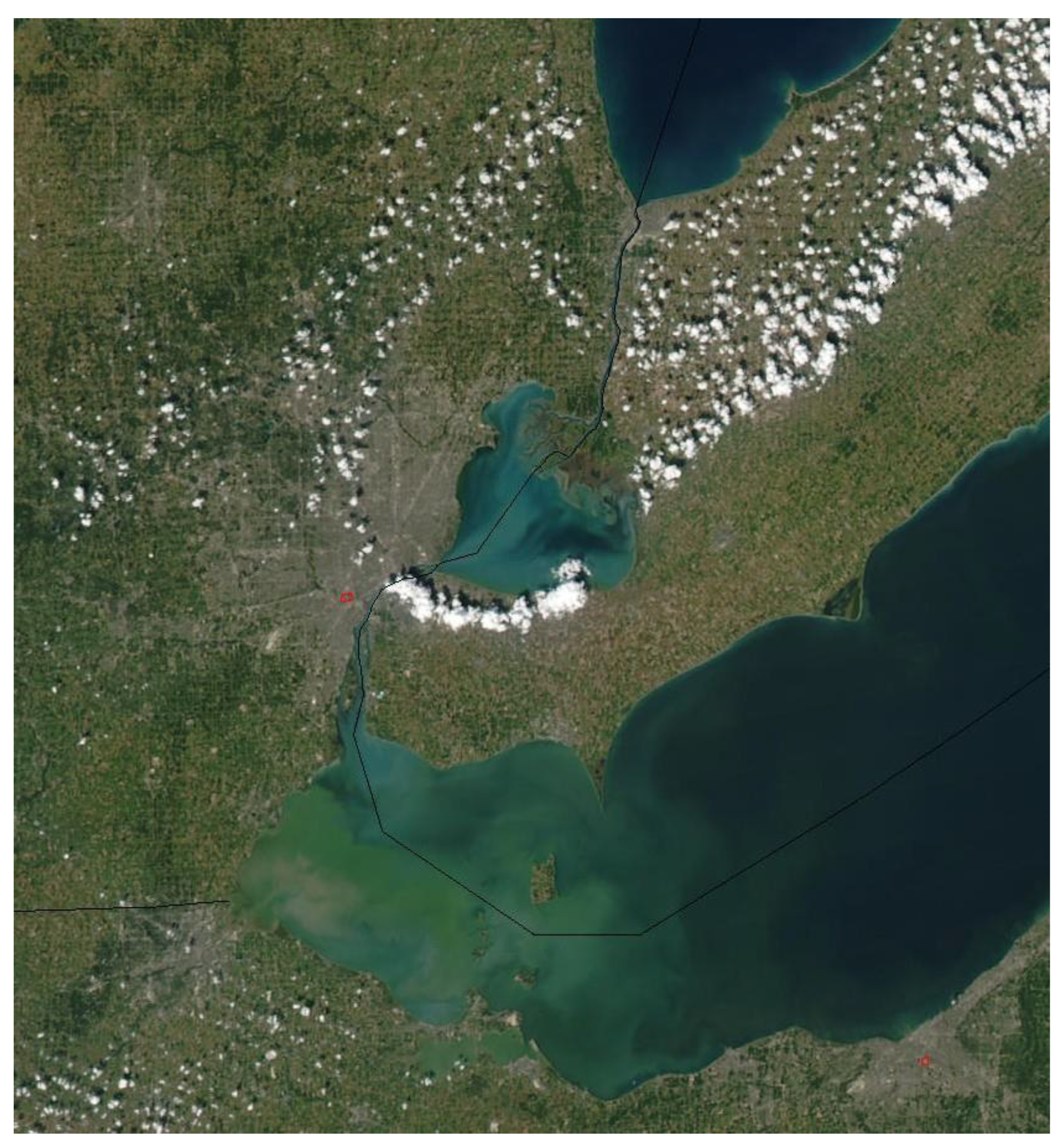

Metropolitan Detroit, Michigan, USA is considered the automobile capital of the United States and has a population of 4.8 million people. It is situated in the heart of the Laurentian Great Lakes, representing one-fifth of the standing freshwater on the Earth’s surface. Its international waters (shared with Canada) stretch from southern Lake Huron, through the St. Clair River, Lake St. Clair, and the Detroit River, and empty into western Lake Erie (

Figure 1). This water corridor is also intersected by six tributaries on the U.S. side, including the Black, Belle, Clinton, Rouge, and Huron rivers, and the River Raisin. All the waters of the upper Great Lakes (i.e., Lakes Superior, Michigan, and Huron) flow through this water corridor and feed the lower Great Lakes (i.e., Lakes Erie and Ontario).

These waters provide drinking water to millions of people, sustain our agriculture and industries, enable maritime shipping (e.g., the Detroit River is part of the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Seaway System that supported

$36 billion USD in economic activity in 2022 [

10]), support world-class outdoor recreation, and enhance quality of life for residents.

Table 1 presents selected examples of this corridor's exceptional water resource attributes.

In response to the growing public interest in greenways, the Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan launched its GreenWays Initiative in 2001 to help build a regional network of greenway trails [

12]. This initiative was the first of its kind in the United States to raise money from the foundation and private sectors to help municipalities plan, design, finance, and build connected greenways across southeast Michigan [

13].

Building on the success of the GreenWays Initiative, the Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan wanted to raise awareness of the important work within the public, private, foundation, and nongovernmental sectors to connect people to these natural resources. In response, the Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan and many partners established The Great Lakes Way in 2019 – an interconnected set of water trails and greenways stretching from Port Huron, Michigan on southern Lake Huron to Toledo, Ohio on western Lake Erie. This manuscript presents a case study of applying an ecosystem approach in developing The Great Lakes Way, including lessons learned.

2. Ecosystem Approach Framework

The United States and Canada have promoted systems thinking through the use of an ecosystem approach in restoring and protecting the Great Lakes for more than four decades [

14,

15]. At the outset, it was considered a paradigm shift where humans were no longer considered separate from the environment, but part of an ecosystem [

16,

17]. Further, in contrast to historical environmental management that fostered top-down, command-and-control decision-making, an ecosystem approach championed collaborative decision-making, co-production of knowledge, and co-innovation of solutions for restoring and sustaining ecosystem health [

18]. This ecosystem approach has evolved from a conceptual framework and aspirational goal of resource managers to an actionable management framework that brings stakeholders together, builds or strengthens capacity, co-produces knowledge, co-innovates solutions, and practices adaptive management – a structured, iterative process of robust decision-making in the face of uncertainty [

19].

Starting in 1985, the International Joint Commission’s Great Lakes Water Quality Board identified Great Lakes pollution hotspots called Areas of Concern, and the federal, state, and provincial governments committed to the development and implementation of remedial action plans to restore ecosystem integrity and impaired beneficial uses through utilization of an ecosystem approach [

20]. Between 1985 and 2019, a total of

$22.78 billion USD was spent on restoring all 43 Areas of Concern [

21].

Key success factors for use of an ecosystem approach in restoring these Areas of Concern include:

creating a consensus long-term vision;

establishing a multi-stakeholder process that achieves cooperative learning;

building capacity;

coupling monitoring/research programs with management;

practicing adaptive management;

measuring and celebrating successes; and

quantifying benefits [

21].

Experience through the Great Lakes Areas of Concern program showed that there was no single best approach to implement an ecosystem approach, rather there were 43 locally designed ecosystem approaches that helped involve stakeholders in a meaningful way, foster cooperative learning, share decision-making, and ensure local ownership [

21,

22]. It must be recognized that The Great Lakes Way was built on this nearly five-decade foundation of operationalizing an ecosystem approach in Great Lakes management.

3. Great Lakes Way Collaboration and Progress

Detroit has a long history of cycling, dating back to the 1800s when bicycling was a primary mode of transportation (

Table 2). With the development of automobiles, bicycling interest and funding stagnated [

23]. Then, starting in the 1970s, interest in non-motorized transportation began growing again.

For more than three decades, Metropolitan Detroit communities could not make the monetary match requirements for federal and state greenway grants. These communities simply did not have the discretionary funds or municipal support for parks and recreation to fulfill match funding requirements for greenway grants. The Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan solved this problem by raising

$30 million from the private and foundation sectors for its GreenWays Initiative, enabling more trails to be constructed, and their many benefits realized. Over time, this initiative grew to

$35 million and leveraged

$150 million to build more than 160 km of greenways [

13].

Building upon the foundation of the GreenWays Initiative, the Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan established a Great Lakes Way Advisory Committee to serve as a boundary organization (i.e., an entity that acts as a bridge between different groups, facilitating communication and collaboration by translating knowledge and perspectives between them, allowing them to work more effectively on shared goals) in 2019. This advisory committee was made up of all the major trail stakeholder groups in the region, including representatives of the National Park Service, Detroit Greenways Coalition, Downriver Linked Greenways, Detroit Riverfront Conservancy, National Wildlife Federation, Ralph C. Wilson, Jr. Foundation, City of Detroit, St. Clair County, Wayne County Parks, Macomb County, Monroe County, Michigan Department of Natural Resources, Huron Clinton Metropolitan Authority, Southeast Michigan Council of Governments, International Wildlife Refuge Alliance, the Wyandot of Anderdon Nation, Michigan Trails and Greenways Alliance, Friends of the Detroit River, Motor Cities National Heritage Area, Macomb County, PEA Group, and the Community Foundation.

The advisory committee’s charge was to inventory existing greenways and water trails along the Lake Huron to Lake Erie corridor, identify gaps and missing linkages, prepare brief descriptions of each greenway or water trail, work with initiative staff and committee members to prepare a vision map, and identify potential strategies for working with public agencies, city, state, and federal governments, other members of the philanthropic sector, nongovernmental organizations, and the private sector to fill missing gaps/linkages and achieve long-term trail sustainability. Through this initiative, priority was intentionally placed on:

amplifying the important work of local trail organizations, ensuring they benefit from being part of a larger trail system while still maintaining their sense of local identity;

building upon existing assets and programs;

ensuring broad equity; and

putting The Great Lakes Way into the consciousness of residents and visitors of the region.

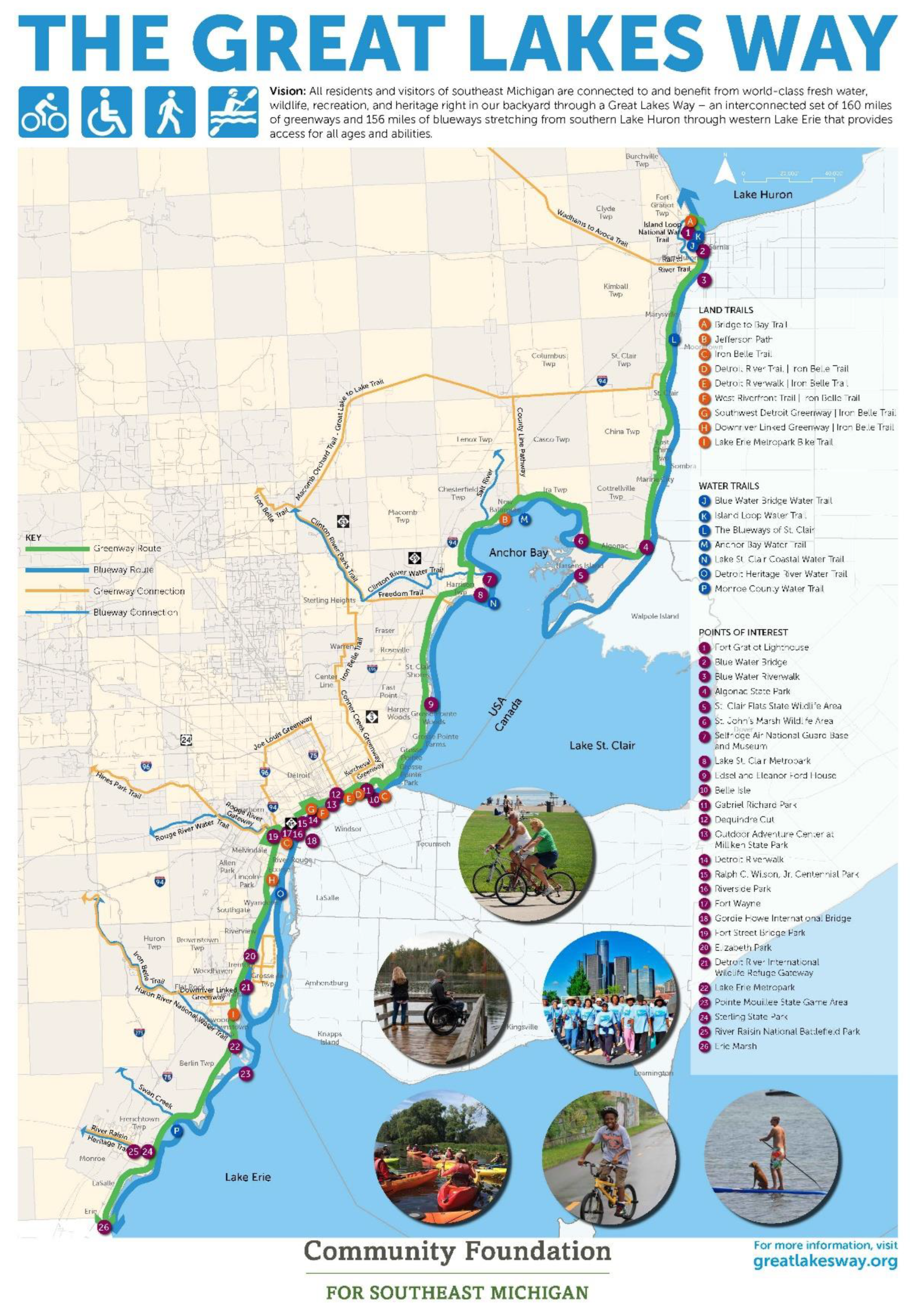

This advisory committee developed a consensus vision that states: “all residents and visitors of southeast Michigan are connected to and benefit from world-class freshwater, wildlife, recreation, and heritage right in our backyard through a Great Lakes Way” and a vision map to help illustrate the vision and extent of the Great Lakes Way (

Figure 2).

To promote The Great Lakes Way, a robust communication and marketing plan was put in place at the outset. Branding was enhanced by creating a logo, marketing materials, infographics, a website, and social media channels. In addition, an interactive trail map (maps.semcog.org/GreatLakesWay/) with local historical, cultural, and ecological points of interest was developed and is hosted by the Southeast Michigan Council of Governments – a regional planning partnership of governmental units serving 4.8 million people in the seven-county region of southeast Michigan.

To ensure acceptance of The Great Lakes Way by citizens in the many communities along the route, focus group sessions were set up in each county. Critical suggestions, feedback, and overwhelming support resulted from these sessions. In addition, 45 communities and other trail stakeholders signed a collaboration agreement pledging support for The Great Lakes Way, demonstrating capacity building. Further, this initiative has served as a crucible for learning about how greenway and water trail stakeholders can work together to promote re-connecting people with natural resources and reaping its many benefits.

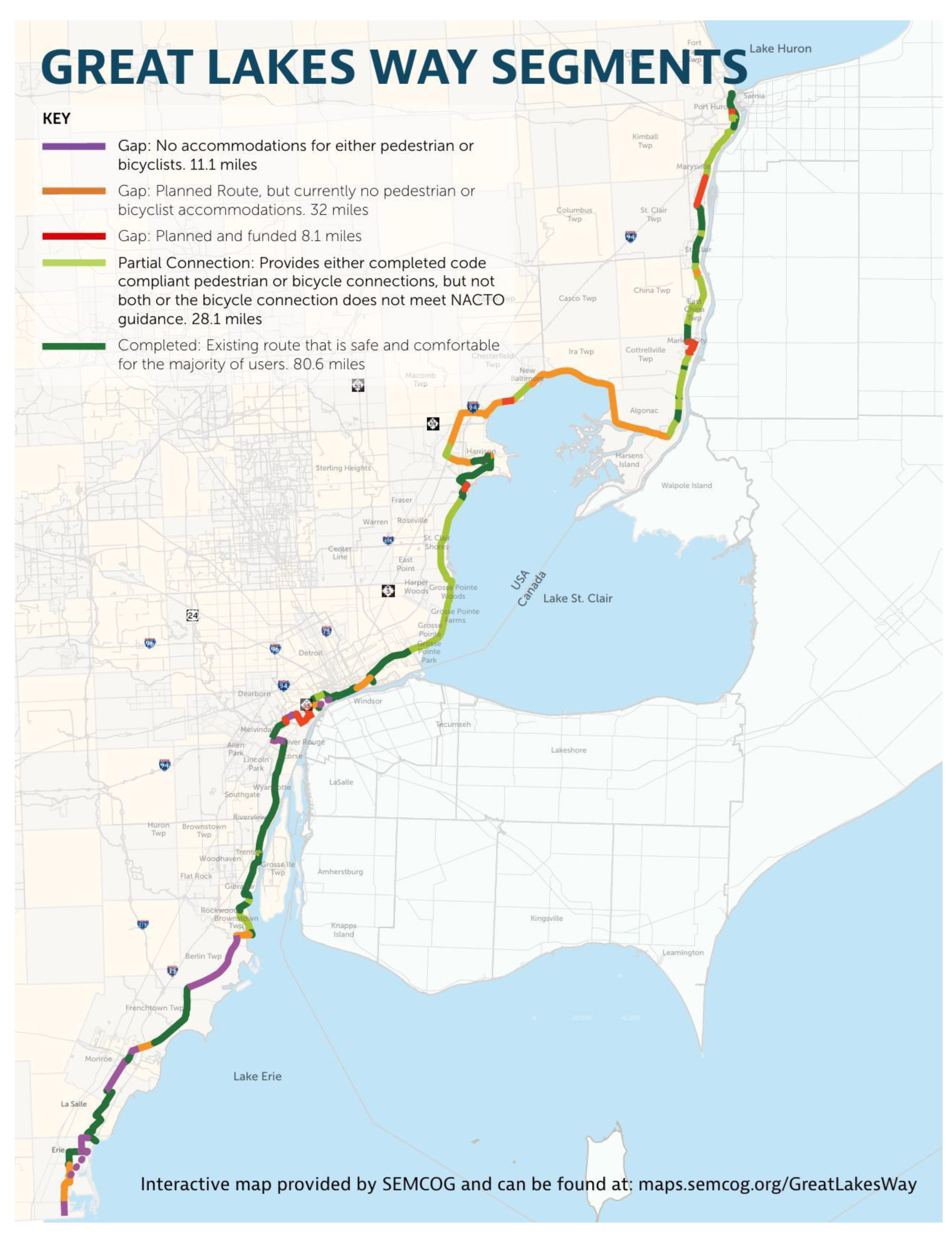

An initial survey of county, city, and trail organizations was undertaken in 2020 at the outset of the initiative to identify existing greenway and water trail routes and identify any gaps in the routes. Next, all greenway routes and gaps were field verified. Using the Geographical Information System (GIS) data provided by the Southeast Michigan Council of Governments, existing and planned trail systems were combined to develop one overall route, including identifying existing routes that are safe and comfortable for the majority of users, partial connections (that provide either completed code compliant pedestrian or bicycle connections, but not both or the bicycle connection does not meet National Association of City Transportation Officials standards trail gaps), planned routes, and gaps.

In the spirit of adaptive management, this survey was again repeated in 2024 to identify more efficient routes, measure progress, and make any necessary mid-course corrections or changes since the initial survey. As a result:

A comparison of these data from the two greenway surveys found that 65% of these trails were useable (i.e., trail segment complete + partial connection of trail segment) in both 2020 and 2024 (

Table 3). However, the total trail kilometers completed (i.e., safe and comfortable for most users) increased from 98 in 2020 to 130 in 2024. The survey also found that an additional 13 km of greenways had received funding for trail construction by 2024. Therefore, the total number of usable and funded greenways increased from 167 km in 2020 (65%) to 199 km in 2024 (74%), demonstrating substantial progress in completing The Great Lakes Way (

Figure 3).

In addition, progress has also been made in extending greenways inland from The Great Lakes Way through Monroe County’s Cornerstone Bicycle Route, Downriver Linked Greenways, the Joe Louis Greenway, the Southwest Greenway of the Detroit Riverfront Conservancy, and more. The total investment in greenways during 2019-2024 was not available. However, for projects reporting cost data, more than $136 million USD was raised for greenway projects over the five years, with the majority by the Detroit Riverfront Conservancy for the Detroit RiverWalk ($100 million USD). Many of these projects have also been supported by the Ralph C. Wilson, Jr. Foundation’s Parks & Trails Initiative.

4. Other Initiatives and Projects

Under the Great Lakes Way initiative, several complementary and reinforcing projects were undertaken to advance and extend this trail system.

4.1. Memorandum of Understanding on Cross-Border Trail Tourism

The Gordie Howe International Bridge (connecting Windsor, Ontario, Canada and Detroit, Michigan, USA) is the longest cable-stayed bridge in North America that has been under construction by the Windsor Detroit Bridge Authority since 2018. It will open in the fall of 2025 with a multi-use path for pedestrians and cyclists. There will be no toll for bicyclists and pedestrians.

In preparation for the opening, four major trail organizations have come together to explore cross-border collaboration on joint trail experiences:

The Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan that has championed the Great Lakes Way (cfsem.org/initiative/greatlakesway);

The Michigan Department of Natural Resources has championed the Iron-Belle Trail that stretches more than 3,200 km from Ironwood in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula to Belle Isle State Park in Detroit (michigan.gov/dnr/places/state-trails/iron-belle);

The Waterfront Regeneration Trust has championed the 3,600-km Great Lakes Waterfront Trail that stretches from the St. Lawrence River in Quebec to Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario (waterfronttrail.org); and

The nonprofit organization called the Trans Canada Trail stewards the over 28,200-km trail called The Trans Canada Trail that stretches from the Atlantic to the Pacific to the Arctic oceans (tctrail.ca).

This partnership was formalized in a 2022 Memorandum of Understanding. Initial areas of cooperation include defining and developing trail destination experiences; collaborating on outreach, marketing, and promotion; and exploring opportunities for using technology to enhance the trail user experience via a digital trail mirroring the physical route.

4.2. State of the Strait Conference

The State of the Strait is a binational (Canada-United States) collaboration that hosts a conference every two years to bring together government managers, researchers, students, environmental and conservation organizations, and concerned citizens. Participants work to understand historical ecosystem conditions and assess the current ecosystem status of the Detroit River and western Lake Erie using an ecosystem approach [

24]. The most recent conference was held on October 22, 2024 and focused on cross-border trail tourism. The Great Lakes Way was a key partner in this conference [

25].

4.3. Pure Michigan Water Trail Designation

In 2024, the Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan applied for a Pure Michigan water trail designation from the State of Michigan. If successful, this designation will help raise awareness of the unique water trail portion of The Great Lakes Way. The Michigan Department of Natural Resources will announce new Pure Michigan Water Trails in 2025. Following a formal designation, the new trails will be incorporated into Pure Michigan marketing and trail maps, along with signage and branding along the route.

4.4. Economic Benefits Study

The Great Lakes Way is a component of growing a Great Lakes blue economy that strives to foster sustainable use of the Great Lakes while improving human well-being and protecting the health of these inland seas. In 2022, the Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan commissioned an economic benefits study of The Great Lakes Way that estimated the range of economic impact from discrete elements that make up this trail system, including greenways, water trails, parks, unique natural areas, waterfront reclamation, connections to Canada, and historical and heritage attributes. The total economic impact of these elements was estimated at approximately

$3.75-

$5 billion annually [

26].

4.5. Potential U.S. Great Lakes Waterfront Trail

Under the leadership of The Council of State Governments, Midwestern Office, and in cooperation with The Great Lakes Way, the eight Great Lakes states are exploring the creation of a U.S. Great Lakes Waterfront Trail that would mirror Canada’s Great Lakes Waterfront Trail (

Figure 4). This trail would be a collaborative effort of the eight Great Lakes States. It would build on the foundation of existing and planned trails and complete trail gaps over time. The goal would be to welcome as many non-motorized uses as possible and provide unforgettable land and water trail experiences along the Great Lakes, promote and enhance local trails, and serve as a gateway to these continentally significant natural resources and their region. Benefits of this trail collaboration include expanding outdoor recreation and ecotourism economies, promoting conservation, encouraging healthy lifestyles, and enhancing quality of life.

The National Park Service’s Rivers, Trails, and Conservation Assistance program (RTCA) supports community-led natural resource conservation and outdoor recreational projects nationwide. RTCA staff are supporting the Council of State Governments by mapping the proposed U.S. Great Lakes Waterfront Trail across all eight Great Lakes states. Staff from five RCTA offices are working with state agencies to identify the best trail routes, including identifying which segments are complete and usable, planned, and represent a gap.

5. Lessons Learned

Creating the Great Lakes Way required systems thinking via the use of an ecosystem approach that understands and analyzes the entire ecosystem and not just the parts themselves. The Great Lakes Way is a good example of working beyond political boundaries by spanning four counties and 28 communities and passing through or along 15 state parks or state game/wildlife areas, two metro parks, 90 county and city parks, one national park (i.e., River Raisin National Battlefield Park), and one international wildlife refuge (i.e., Detroit River International Wildlife Refuge). The Great Lakes Way examples of working beyond disciplinary and programmatic boundaries include:

Protecting Humbug Marsh in Trenton and Gibraltar, Michigan as a Ramsar Wetland of International Importance and cleaning up an adjacent industrial brownfield to serve as an ecological buffer to the marsh and be the home of the visitor center for the Detroit River International Wildlife Refuge, while improving public access through responsible greenway trail development [

27];

Remediating contaminated sediment at both Detroit’s former Uniroyal site and Ralph C. Wilson, Jr. Centennial Park that led to shoreline habitat rehabilitation and the eventual construction of two sections of the Detroit RiverWalk – the number one riverwalk in the United States identified three years in a row by USA Today [

24];

Cleaning up the River Raisin Area of Concern that led to revitalization of Monroe, Michigan, including creation of the Monroe Loop Trail [

28]; and

Restoring 1.3 km of shoreline, 0.3 ha of fish spawning habitat, and 0.9 ha of riparian nursery habitat in 2014 along Port Huron’s Blue Water Riverwalk that is part of Bridge to Bay Trail in St. Clair County [

29].

Five key lessons learned from applying an ecosystem approach in the creation of The Great Lakes Way include:

Lesson 1: Bringing Stakeholders Together and Developing a Compelling Vision

Successful trail and greenway initiatives have strong community buy-in, which takes real work and commitment to develop. The Great Lakes Way Advisory Committee and partners like the Detroit River Conservancy, the Joe Louis Greenway Partnership, and Downriver Linked Greenways are good examples of organizations that steward ambitious visions and are committed to building and maintaining partnerships to advance them. Critical to such multi-stakeholder efforts is developing a clear and compelling vision that is relevant, appealing, and engaging. Such a vision is often described as a picture so clear that it can be carried in the hearts and minds of all stakeholders [

30]. The Great Lakes Way vision was broadly supported by all four counties, all waterfront communities, the state and federal resource management agencies, and many nongovernmental organizations and local businesses.

Lesson 2: Building and Strengthening Capacity

The United Nations defines capacity-building as the process of developing and strengthening the skills, instincts, abilities, processes, and resources that organizations and communities need to survive, adapt, and thrive in a fast-changing world. Capacity building has been essential in the creation of The Great Lakes Way. Good capacity-building examples include:

Raising approximately $2 million USD from the foundation and private sectors by the Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan to undertake the necessary planning, support cooperative learning, carry out necessary studies (e.g., economic benefits), foster stakeholder engagement, and more.

Securing the services of a landscape architecture firm (i.e., PEA Group) to undertake the mapping, develop a vision map, translate architecture and engineering drawings and documents for trail stakeholders, facilitate multi-stakeholder meetings, etc.

Forming a partnership with the Southeast Michigan Council of Governments to create and maintain a publicly accessible interactive map of The Great Lakes Way (maps.semcog.org/GreatLakesWay).

Obtaining technical assistance and advice from the National Park Service’s River, Trails, and Conservation Assistance program for strategic community engagement.

Securing signed collaboration agreements from 45 different communities, businesses, and nongovernmental organizations.

Lesson 3: Identifying and Empowering a Boundary Organization

A boundary organization is a formal body that connects science and policy to promote collaboration for achieving common goals [

31]. It plays an important role in the use of an ecosystem approach in resource management [

19,

32]. The Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan’s Great Lakes Way Advisory Committee serves as a boundary organization for this initiative, promoting cooperative learning among members and bringing all up to a common level of understanding for informed decision-making. Further, it serves as a facilitator, knowledge broker, trust builder, and champion of strengthening science-policy-management linkages.

Lesson 4: Co-Producing Knowledge and Co-Innovating Solutions

Actionable science is research that is designed with stakeholders to better inform decisions, improve the design or implementation of public policies or programs, and/or influence strategies, planning, and behaviors that affect the ecosystem [

33,

34]. Key elements of actionable science are co-production of knowledge and co-innovation of solutions.

The Great Lakes Way Advisory Committee has proven to be a good forum to co-produce knowledge and co-innovate solutions. Two good examples of co-producing knowledge are: 1) performing the initial 2000 survey with local trail groups that identified the extent of the trails completed, gaps, and obstacles to filling the gaps, and 2) undertaking a study of economic benefits that demonstrated the return on trail investments. Two good examples of co-innovating solutions are: 1) working with local trail partners to identify more efficient trail routes as a result of the 2024 trail survey, and 2) working with local trail partners to identify the most compelling trail routes for Canadians exiting the multi-use path of the new Gordie Howe International Bridge.

Lesson 5: Practicing Adaptive Management

Adaptive management is well recognized as a fundamental tenet of use of an ecosystem approach in resource management [

35,

36]. Two examples of the practice of adaptive management include: 1) identifying trail gaps based on an initial 2020 survey and working with local trail partners to prioritize filling gaps, and then performing a follow-up trail survey in 2024 that showed that the total number of usable and funded greenways increased from 167 km in 2020 (65%) to 199 km in 2024 (74%), and 2) making mid-course corrections in trail routes that were more efficient based on the 2024 trail survey.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.H., L.W., and B.J.; methods, J.H., L.W., and B.J.; data collection, L.W.; writing—original draft preparation, J.H.; writing—review and editing, L.W. and B.J.; supervision, J.H., L.W., and B.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This case study was prepared with funding from The Carls Foundation, the Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan, the DTE Foundation, the Fred and Barbara Erb Family Foundation, General Motors Company, The Leinweber Foundation, and The Donald R. and Esther Simon Foundation.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data for this case study will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the leadership and guidance of the members of The Great Lakes Way Advisory Committee that served as a boundary organization on this case study initiative. Further, we gratefully acknowledge the funders of The Great Lakes Way initiative, including: The Carls Foundation, the Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan, the DTE Foundation, the Fred and Barbara Erb Family Foundation, General Motors Company, The Leinweber Foundation, and The Donald R. and Esther Simon Foundation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Arendt, R. Putting greenways first. Planning. 2011, 77, 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Coutts, C. , Greenway accessibility and physical-activity behavior. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design. 2008, 35, 552–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabos, J.G. Introduction and overview: The greenway movement, uses and potentials of greenways. Landscape and Urban Planning. 1995, 33, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobster, P.H. , Westphal, L.M., The human dimensions of urban greenways: Planning for recreation and related experiences. Landscape and Urban Planning. 2004, 68, 147–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, C.E. , 1990. Greenways for America. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press.

- Hutson, G. , Baird, J., Ives, C.D., Dale, G., Holzer, J.M., Plummer, R., Outdoor adventure education as a platform for developing environmental leadership. People and Nature. 2024, 5, 1974–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, J.H. , 2019. Waterfront Porch: Reclaiming Detroit’s Industrial Waterfront as a Gathering Place for All. Michigan State University Press, Greenstone Books, East Lansing, Michigan, USA. http://msupress.org/books/book/?id=50-1D0-4543#.XJ-VbphKjIV.

- Mumaw, L. , Transforming urban gardeners into land stewards. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2017, 52, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, J.H. , Scott, T, Gell, G., Berk, K., Reconnecting people to the Detroit River – A transboundary effort. Aquatic Ecosystem Health & Management. 2022, 1, 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Martin Associates, 2023. Economic impacts of maritime shipping in the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence region. Lancaster, Pennsylvania, USA.

- Hartig, J.H. , Dekker, T., 2021. Establishment of a water collaborative for metropolitan Detroit, MI, USA. In, Green Chemistry: Water and its Treatment, A.M. Benvenuto, H. Plaumann (eds.), pp. 5-16, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter.

- Dempsey, D. , 2019. The heart of the Great Lakes: Freshwater in the past, present, and future of southeast Michigan. Greenstone Books, Michigan State University Press, East Lansing, Michigan, USA.

- Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan. 2024. Available online: https://cfsem.org/initiative/greatlakesway/reports/ (accessed on 31 January 2025).

- Great Lakes Science Advisory Board, 1978. Ecosystem approach: Scope and implications of an ecosystem approach to transboundary problems in the Great Lakes basin. Special Report to the International Joint Commission. International Joint Commission, Great Lakes Regional Office, Windsor, Ontario, Canada.

- Canada and the United States, 1978. Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement. Windsor, Ontario, Canada.

- Vallentyne, J.R. , Beeton, A.M., The ecosystem approach to managing human uses and abuses of natural resources in the Great Lakes Basin. Environmental Conservation 1986, 15, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, J.H. , Vallentyne, J.R., Use of an ecosystem approach to restore degraded areas of the Great Lakes. Ambio 1989, 18, 423–428. [Google Scholar]

- Hartig, J.H. , Zarull, M.A., Heidtke, T.M., Shah, H., Implementing ecosystem-based management: Lessons from the Great Lakes. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management. 1998, 41, 45–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, J.H. , Tsaroucha, F., Mokdad, A., Haffner, D., Febria, C., 2024. An ecosystem approach: Strengthening the interface of science, policy, practice, and management. Healthy Headwaters Lab, Great Lakes Institute for Environmental Research, University of Windsor, Windsor, Ontario, Canada. [CrossRef]

- Hartig, J.H. , Thomas, R.L., Development of plans to restore degraded areas of the Great Lakes. Environmental Management. 1988, 12, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, J.H. , Krantzberg, G., Alsip, P., Thirty-five years of restoring Great Lakes Areas of Concern: Gradual progress, hopeful future. Journal of Great Lakes Research. 2020, 46, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsip, P. , Hartig, J.H., Krantzberg, G., Williams, K.C., Wondolleck, J., Evolving institutional arrangements for use of an ecosystem approach in restoring Great Lakes Areas of Concern. Sustainability. 2021, 13, 1532–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, T. , Gell, G., 2020. The legacy of bicycles in Detroit, Michigan: A look at greenways through time, in, J.H. Hartig, S.F., Francoeur, et al. (Eds.), Checkup: Assessing Ecosystem Health of the Detroit River and Western Lake Erie, 451-458 pp., Great Lakes Institute for Environmental Research Occasional Publication No. 11, University of Windsor, Ontario, Canada.

- Hartig, J.H. , Godwin, C.M., Ellis, B., Allan, J.W., Sinha, S.K., Hall, T., Co-production of knowledge and co-innovation of solutions for contaminated sediments in the Detroit and Rouge Rivers. J. Great Lakes Res. 2024, 50, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, J.H. , Newton, L., Scott, T. Koehler, M., Gannon, J.E., Lovall, S., Woiwode, T., Greene, A., Hillier, W., Antolak, E., 2025. Fostering cross-border trail tourism between the Windsor, Ontario and Detroit, Michigan metropolitan areas. Great Lakes Institute for Environmental Research Occasional Publication No. 13. University of Windsor, Windsor, Ontario, Canada ISSN 1715-3980.

- Austin, J. Steinman, A., Weinstein, A., 2023. The Great Lakes Way: Enriching life at the heart of the Great Lakes. Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan, Detroit, Michigan, USA.

- Hartig, J.H. , Wallace, M.C., Creating World-Class Gathering Places for People and Wildlife along the Detroit Riverfront, Michigan, USA. Sustainability 2015, 7, 7–15073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, S.J. , Cochran, M., Hartig, J.H., 2019. From cleanup of the River Raisin to revitalization of Monroe, Michigan. In, Great Lakes Revival: How Restoring Polluted Waters Leads to Rebirth of Great Lakes Communities. Hartig, J.H., Krantzberg, G., Austin, J.C., McIntyre, P., (eds.), pp. 47-51. International Association for Great Lakes Research. Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA.

- Michigan Department of Environmental Quality, 2017. Recommendation removal: Loss of fish and wildlife habitat beneficial use impairment, St. Clair River Area of Concern. Lansing, Michigan, USA.

- Senge, P.M. , 1990. The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. New York: Currency Doubleday Books.

- Gray, N.J. , The role of boundary organizations in co-management: examining the politics of knowledge integration in a marine protected area in Belize. International Journal of the Commons. 2016, 10, 1013–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, C.A. , Francis, T.B., Baker, J.E., Georgiadis, N., Kinney, A., Magel, C., Rice, J., Roberts, T., Wright, C.W., A boundary spanning system supports large-scale ecosystem-based management. Environmental Science & Policy 2022, 133, 137–145. [Google Scholar]

- Beier, P. , Hansen, L.J., Helbrecht, L., Behar, D., A how-to guide for coproduction of actionable science. Conservation Letters. 2017, 10, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, M.A. , Socioenvironmental sustainability and actionable science. BioScience 2012, 62, 5–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S. , 1978. Adaptive Environmental Assessment and Management. International Series on Applied Systems Analysis. International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.

- Pahl-Wosti, C. , Transitions towards adaptive management of water facing climate and global change. Water Resources Management 2007, 21, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).