Submitted:

05 June 2025

Posted:

05 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

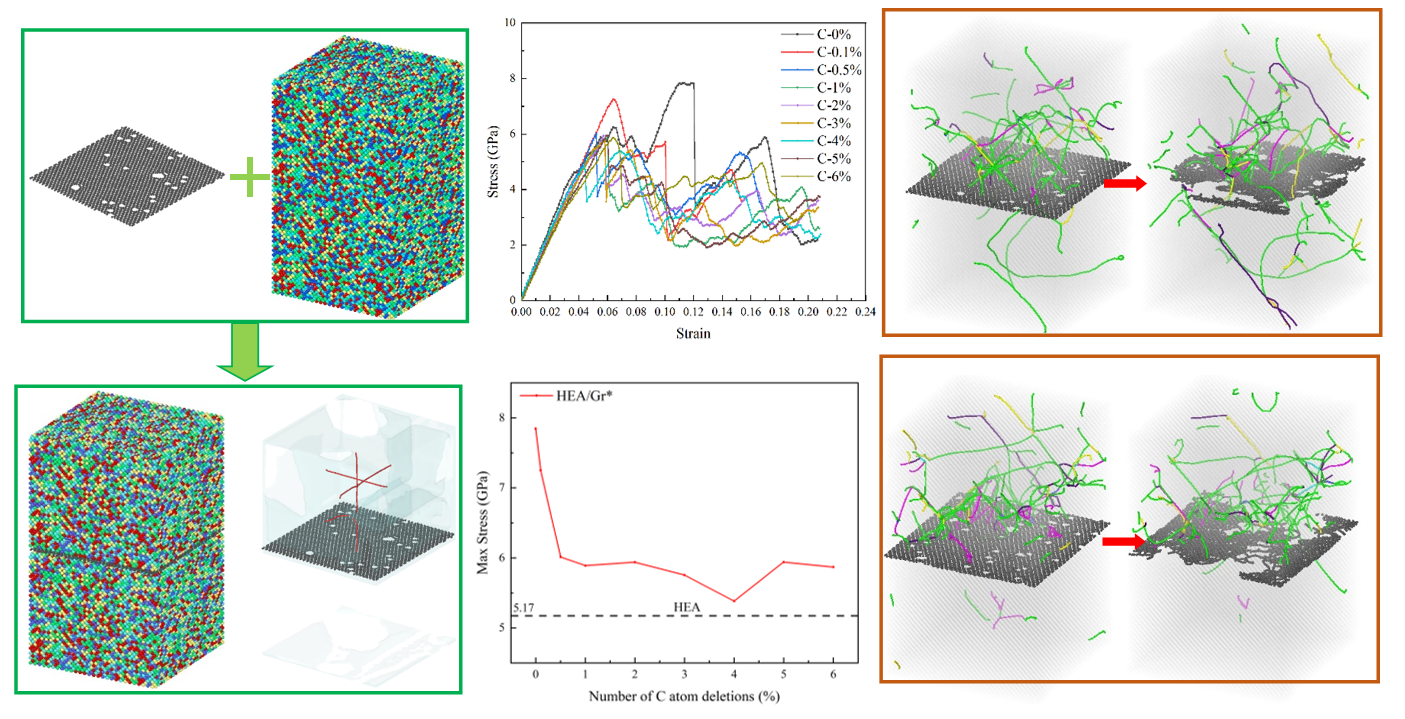

2.1. Modeling

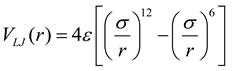

2.2. Interatomic Potentials

2.3. Simulations

3. Results

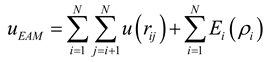

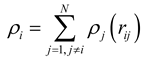

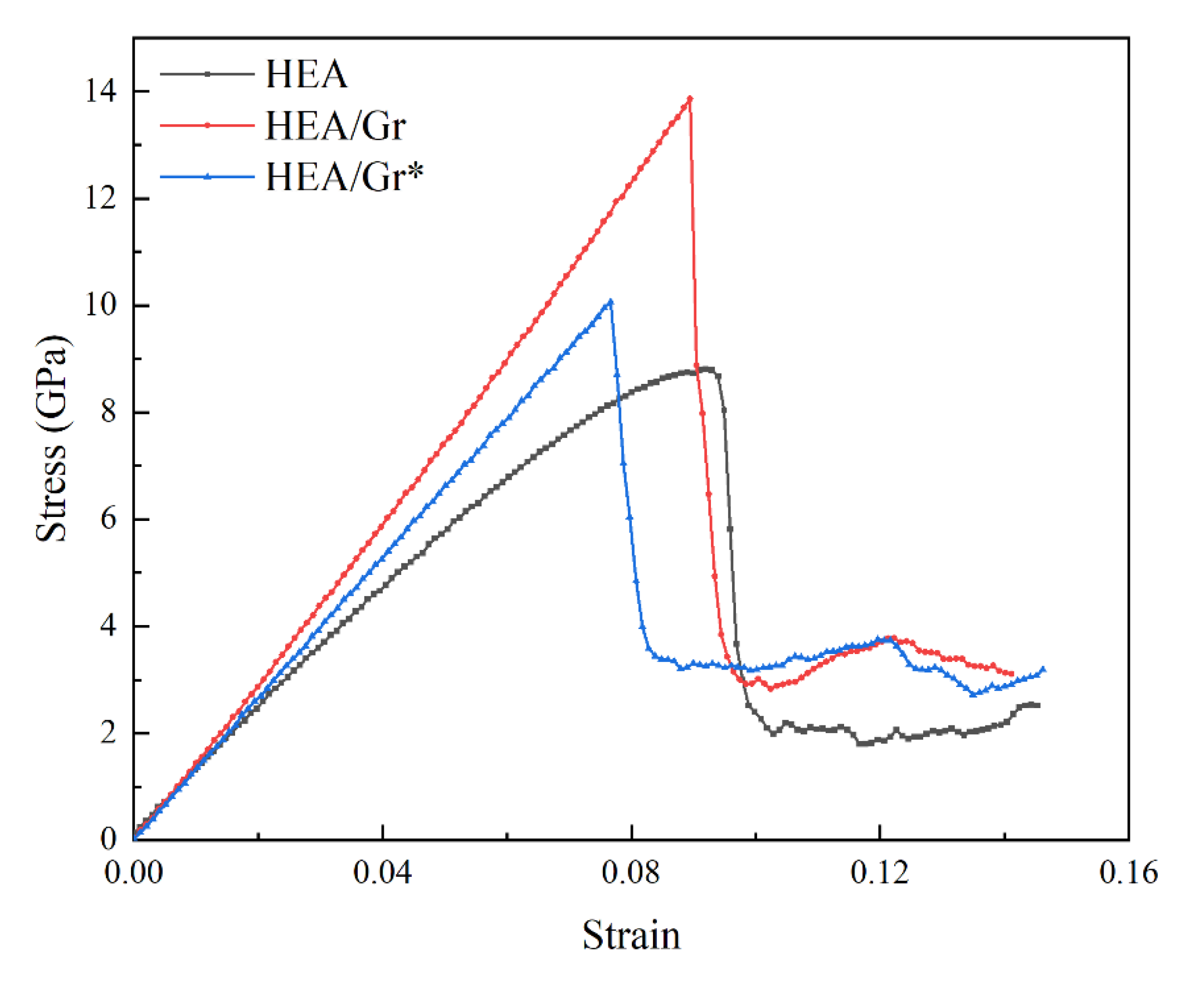

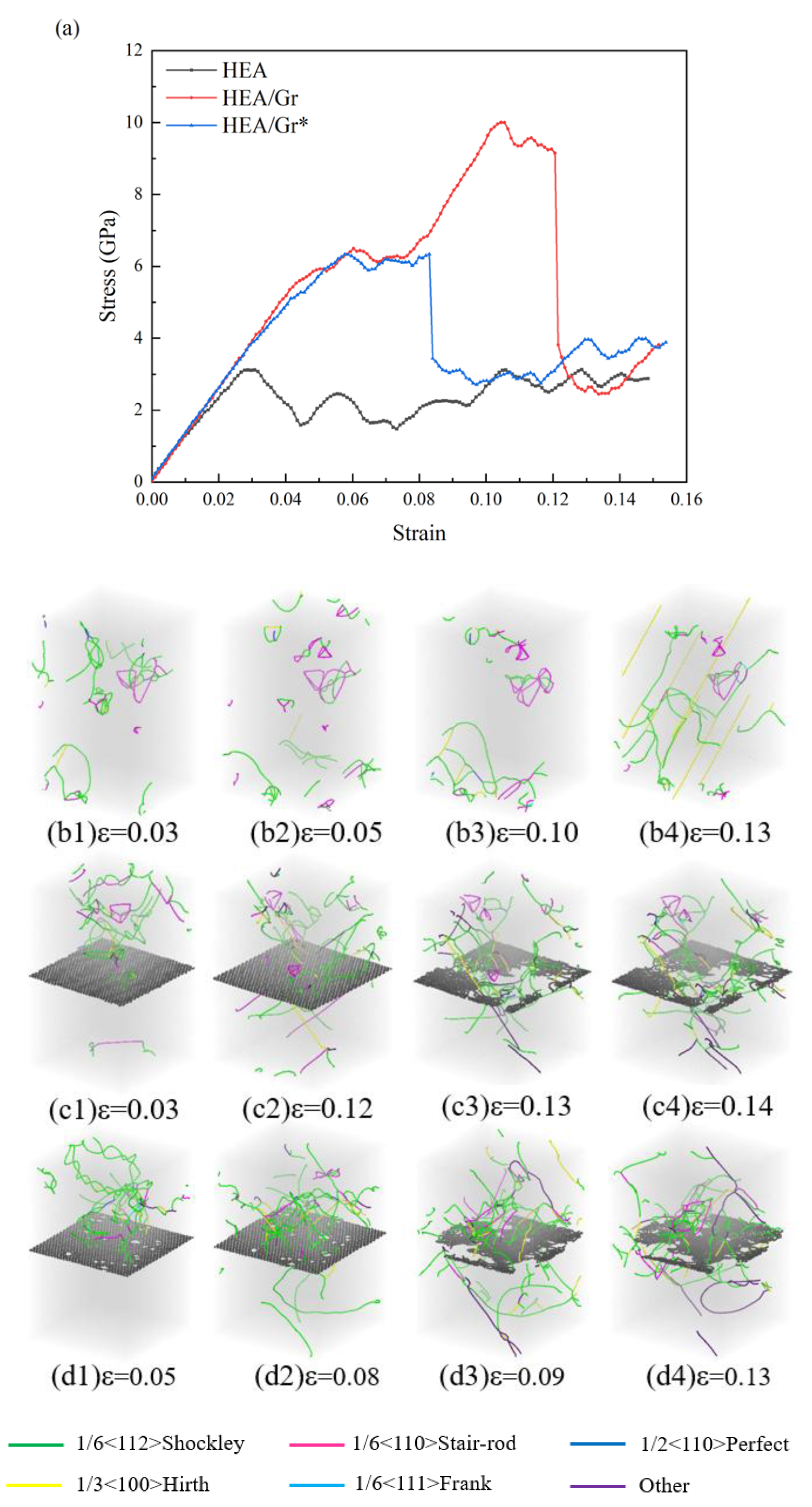

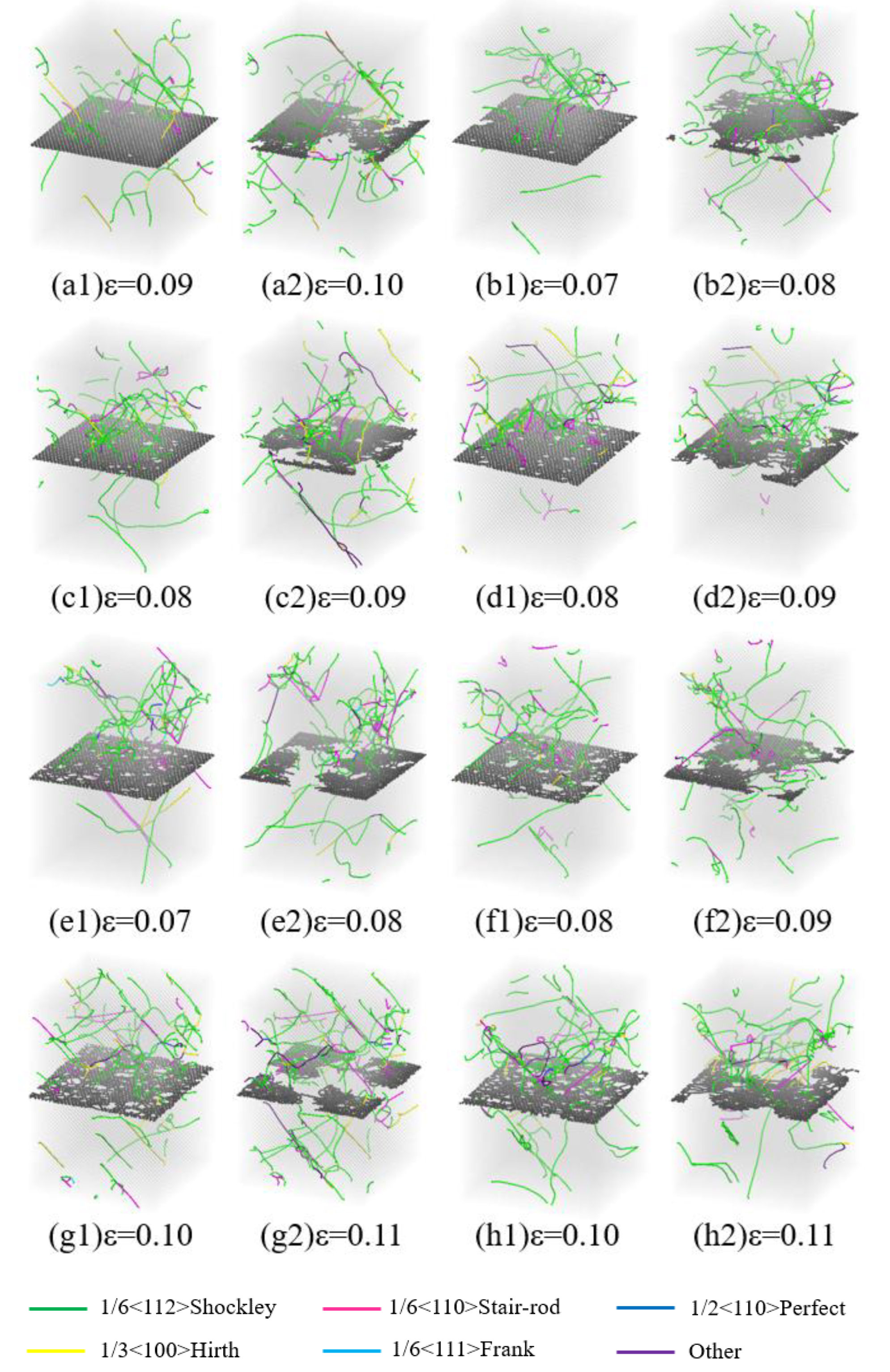

3.1. The Impact of Gr Vacancy Defects on the Tensile Performance

3.2. The Impact of Gr Vacancy Defects on the Compressive Performance

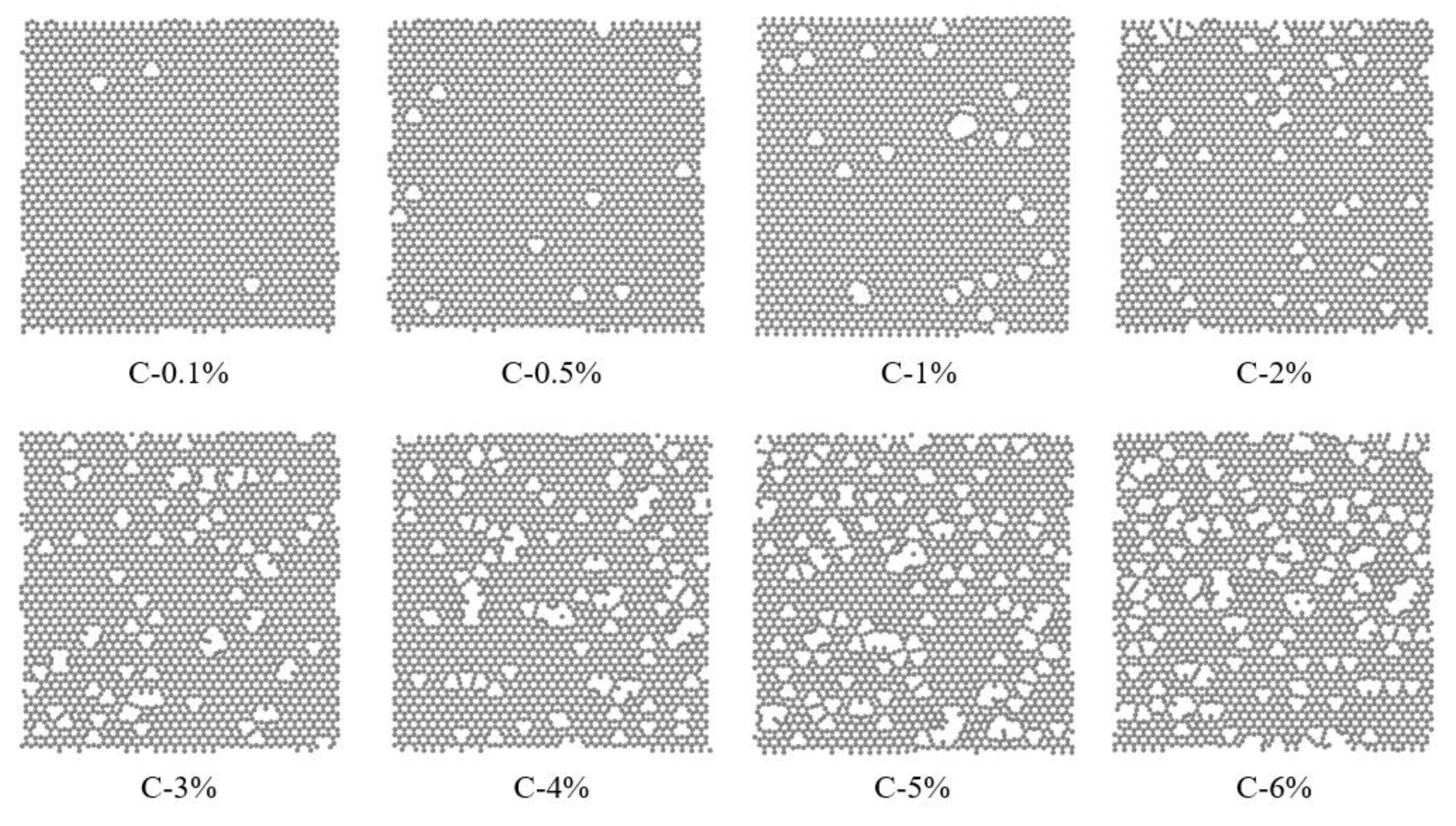

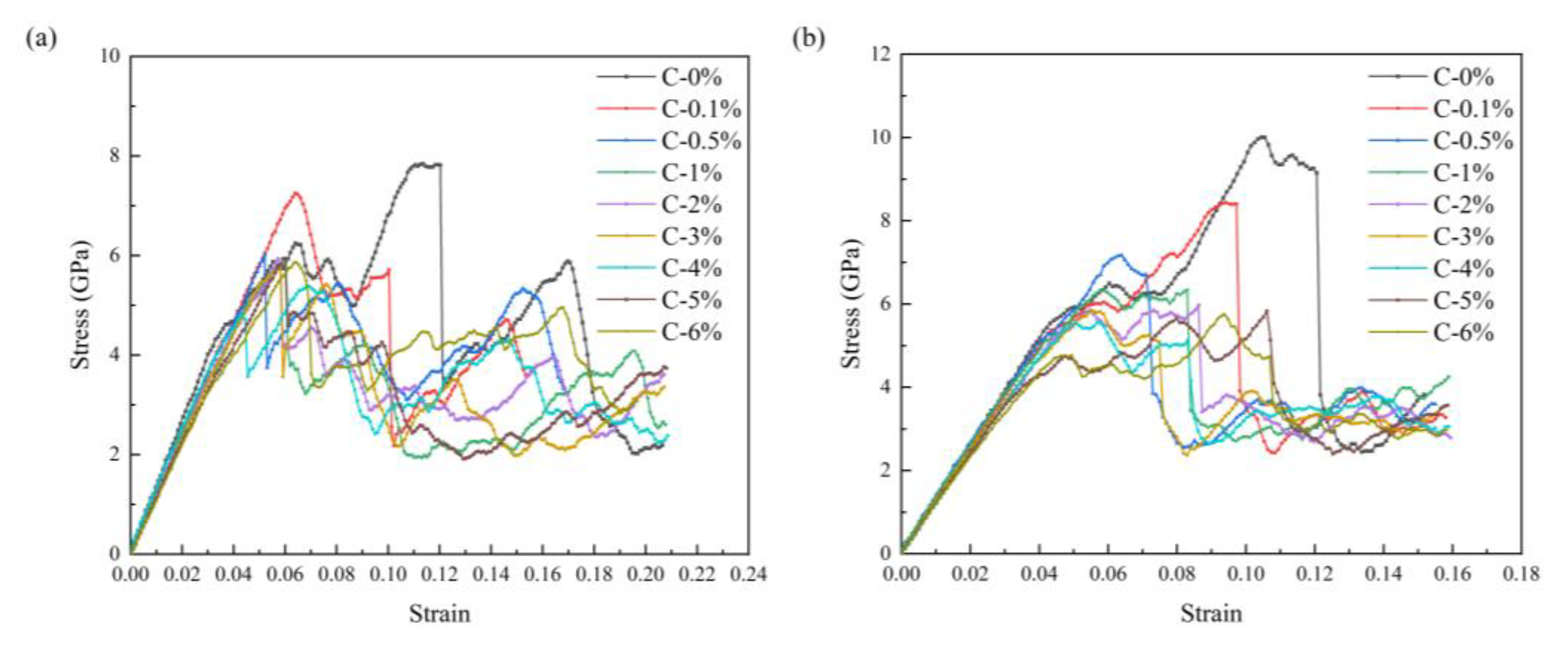

3.3. The Impact of Varying Quantities of Vacancy Defects on the Enhancement Effect

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, C. , et al., Lattice distortion in a strong and ductile refractory high-entropy alloy. Acta Materialia, 2018. 160: p. 158-172.

- Chung, D., Z. Ding, and Y. Yang, Hierarchical eutectic structure enabling superior fracture toughness and superb strength in CoCrFeNiNb0. 5 eutectic high entropy alloy at room temperature. Advanced Engineering Materials, 2019. 21(3): p. 1801060.

- Chou, Y., J. Yeh, and H. Shih, The effect of molybdenum on the corrosion behaviour of the high-entropy alloys Co1. 5CrFeNi1. 5Ti0. 5Mox in aqueous environments. Corrosion Science, 2010. 52(8): p. 2571-2581.

- Yang, T. , et al., Irradiation responses and defect behavior of single-phase concentrated solid solution alloys. Journal of Materials Research, 2018. 33(19): p. 3077-3091.

- Ye, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, Y.; He, Q.; Lu, J.; Yang, Y. Elemental segregation in solid-solution high-entropy alloys: experiments and modeling. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2016, 681, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Qiao, D.; Zhang, H.; Miao, J.; Zhao, H.; Wang, J.; Lu, Y.; Wang, T.; Li, T. Microstructure and mechanical properties of CxHf0. 25NbTaW0. 5 refractory high-entropy alloys at room and high temperatures. Journal of Materials Science & Technology 2022, 97, 229–238. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Z.; Niu, Z.; Gao, Z.; Li, J.; Bai, G.; Ke, L.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, C. Microstructure and wear behavior of in-situ synthesized TiC-reinforced CoCrFeNi high entropy alloy prepared by laser cladding. Applied Surface Science 2024, 670, 160720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ares, P.; Novoselov, K.S. Recent advances in graphene and other 2D materials. Nano Materials Science 2022, 4, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Shi, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Xie, M.; Wang, H.; Bou-Saïd, B.; Liu, W. Recent advances in self-lubricating metal matrix nanocomposites reinforced by carbonous materials: A review. Nano Materials Science 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Qing, F.; Sun, X.; Wu, R.; Wang, H.; Wen, Q.; Li, X. Preparation of graphene-coated Cu particles with oxidation resistance by flash joule heating. Carbon 2024, 224, 119060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhou, Q.; Shi, Y.; Ye, W.; Lin, Y.; Wang, H. The deformation mechanism of graphene nanosheets embedded in high-entropy alloy upon sliding. Carbon 2024, 229, 119532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Zhou, Q.; Shi, Y.; Xie, M.; Chen, B.; Wang, H.; Liu, W. Robust wear performance of graphene-reinforced high entropy alloy composites. Carbon 2024, 224, 119040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, A.; Suenaga, K.; Gloter, A.; Urita, K.; Iijima, S. Direct evidence for atomic defects in graphene layers. nature 2004, 430, 870–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian; Kisielowski. Observing Atoms at Work by Controlling Beam-Sample Interactions. Advanced materials (Deerfield Beach, Fla.) 2015.

- B, B.P.A.; A, E.M.; B, A.B.; C, M.H.R.; C, T.G.; D, J.N.; D, V.S.; B, R.J.K.; C, T.P.; A, S.R.P.S. Iron filled single-wall carbon nanotubes – A novel ferromagnetic medium. Chemical Physics Letters 2006, 421, 129–133. [Google Scholar]

- Gass, M.H.; Bangert, U.; Bleloch, A.L.; Wang, P.; Nair, R.R.; Geim, A.K. Free-standing graphene at atomic resolution. Nature Nanotechnology 2008, 3, 676–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, J.C.; Kisielowski, C.; Erni, R.; Rossell, M.D.; Crommie, M.F.; Zettl, A. Direct Imaging of Lattice Atoms and Topological Defects in Graphene Membranes. Nano Letters 2008, 8, 3582–3586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sethurajaperumal, A.; Ravichandran, V.; Merenkov, I.; Ostrikov, K.K.; Varrla, E. Delamination and defects in graphene nanosheets exfoliated from 3D precursors. Carbon 2023, 213, 118306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, A.W.; Allen, C.S.; Wu, Y.A.; He, K.; Olivier, J.; Neethling, J.; Kirkland, A.I.; Warner, J.H. Spatial control of defect creation in graphene at the nanoscale. Nature communications 2012, 3, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, R.; Ajori, S.; Motevalli, B. Mechanical properties of defective single-layered graphene sheets via molecular dynamics simulation. Superlattices and Microstructures 2012, 51, 274–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia, A.; Peón-Escalante, R.; Villanueva, C.; Avilés, F. Influence of vacancies on the elastic properties of a graphene sheet. Computational Materials Science 2012, 55, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorov, A.S.; Popov, Z.I.; Fedorov, D.A.; Eliseeva, N.S.; Serjantova, M.V.; Kuzubov, A.A. DFT investigation of the influence of ordered vacancies on elastic and magnetic properties of graphene and graphene-like SiC and BN structures. Physica Status Solidi 2012, 249, 2549–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Polin, G.; Gomez-Navarro, C.; Gomez-Herrero, J. The effect of rippling on the mechanical properties of graphene. Nano Materials Science 2022, 4, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, C.; Dappe, Y.J.; Dong, C.; Robinson, J.A.; Trampert, A.; Engel-Herbert, R. Atomic-scale characterization of defects in oxygen plasma-treated graphene by scanning tunneling microscopy. Carbon 2024, 227, 119260. [Google Scholar]

- Wei Wang, J.; Narayanan, S.; Yu Huang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, T.; Mao, S.X. Atomic-scale dynamic process of deformation-induced stacking fault tetrahedra in gold nanocrystals. Nature communications 2013, 4, 2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plimpton, S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. Journal of computational physics 1995, 117, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Huang, R.; Zhang, X.; Cao, T.; Xue, Y.; Li, X. Deformation mechanisms and remarkable strain hardening in single-crystalline high-entropy-alloy micropillars/nanopillars. Nano Letters 2021, 21, 3671–3679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatt, M.D.; Kim, H.; Kim, G. Various defects in graphene: a review. RSC advances 2022, 12, 21520–21547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkas, D.; Caro, A. Model interatomic potentials and lattice strain in a high-entropy alloy. Journal of Materials Research 2018, 33, 3218–3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deluigi, O.R.; Pasianot, R.C.; Valencia, F.; Caro, A.; Farkas, D.; Bringa, E.M. Simulations of primary damage in a High Entropy Alloy: Probing enhanced radiation resistance. Acta Materialia 2021, 213, 116951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Dong, L.; Dong, X.; Zhao, W.; Liu, J.; Xiong, J.; Xu, C. Study on wear behavior of FeNiCrCoCu high entropy alloy coating on Cu substrate based on molecular dynamics. Applied Surface Science 2021, 570, 151236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Ma, Z.; Zhao, H.; Ren, L. Atomic perspective of contact protection in graphene-coated high-entropy films. Tribology International 2022, 174, 107748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Siu, K.W.; Liao, W.; Wang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Lu, Y. In situ mechanical characterization of CoCrCuFeNi high-entropy alloy micro/nano-pillars for their size-dependent mechanical behavior. Materials Research Express 2016, 3, 094002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Dedoncker, R.; Li, L.; Sedghgooya, F.; Zighem, F.; Ji, V.; Depla, D.; Djemia, P.; Faurie, D. Mechanical properties of CoCrCuFeNi multi-principal element alloy thin films on Kapton substrates. Surface and Coatings Technology 2020, 402, 126474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Guo, Q.; Li, Z.; Fan, G.; Xiong, D.-B.; Su, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, D. Enhanced mechanical properties of graphene (reduced graphene oxide)/aluminum composites with a bioinspired nanolaminated structure. Nano letters 2015, 15, 8077–8083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, S.J.; Tutein, A.B.; Harrison, J.A. A reactive potential for hydrocarbons with intermolecular interactions. The Journal of chemical physics 2000, 112, 6472–6486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Lu, C.; Michal, G.; Li, J.; Wang, R. Strong strain hardening in graphene/nanotwinned metal composites revealed by molecular dynamics simulations. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences 2021, 201, 106460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, S.-K.; Yang, Y.-T. A molecular dynamics study of the mechanical properties of graphene nanoribbon-embedded gold composites. Nanoscale 2011, 3, 4307–4313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.-J.; Yang, Q.-S.; He, X.; Liew, K. Modeling of interface cracking in copper–graphite composites by MD and CFE method. Composites Part B: Engineering 2014, 58, 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Huang, P.; Wang, F. Graphene-boundary strengthening mechanism in Cu/graphene nanocomposites: a molecular dynamics simulation. Materials & Design 2020, 190, 108555. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Lee, J.; Yeom, M.S.; Shin, J.W.; Kim, H.; Cui, Y.; Kysar, J.W.; Hone, J.; Jung, Y.; Jeon, S. Strengthening effect of single-atomic-layer graphene in metal–graphene nanolayered composites. Nature communications 2013, 4, 2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhapuram, R.R.; Muller, S.E.; Nair, A.K. Nanoscale bending properties of bio-inspired Ni-graphene nanocomposites. Composite Structures 2019, 220, 798–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuang, F.; Aifantis, K.E. Dislocation-graphene interactions in Cu/graphene composites and the effect of boundary conditions: a molecular dynamics study. Carbon 2021, 172, 50–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Brault, P.; Thomann, A.-L.; Bauchire, J.-M. AlCoCrCuFeNi high entropy alloy cluster growth and annealing on silicon: A classical molecular dynamics simulation study. Applied surface science 2013, 285, 810–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, H.; Ren, L. Strengthening effect of high-entropy alloys endowed by monolayer graphene. Materials Today Physics 2022, 27, 100800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pair | (Å) | |

|---|---|---|

| Fe–C | 3.1000 | 0.050000 |

| Ni–C | 2.8520 | 0.230000 |

| Cr–C | 2.8680 | 0.037758 |

| Co–C | 2.8420 | 0.038281 |

| Cu–C | 3.0825 | 0.025780 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).