Submitted:

05 June 2025

Posted:

06 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Data Collection and Protocol

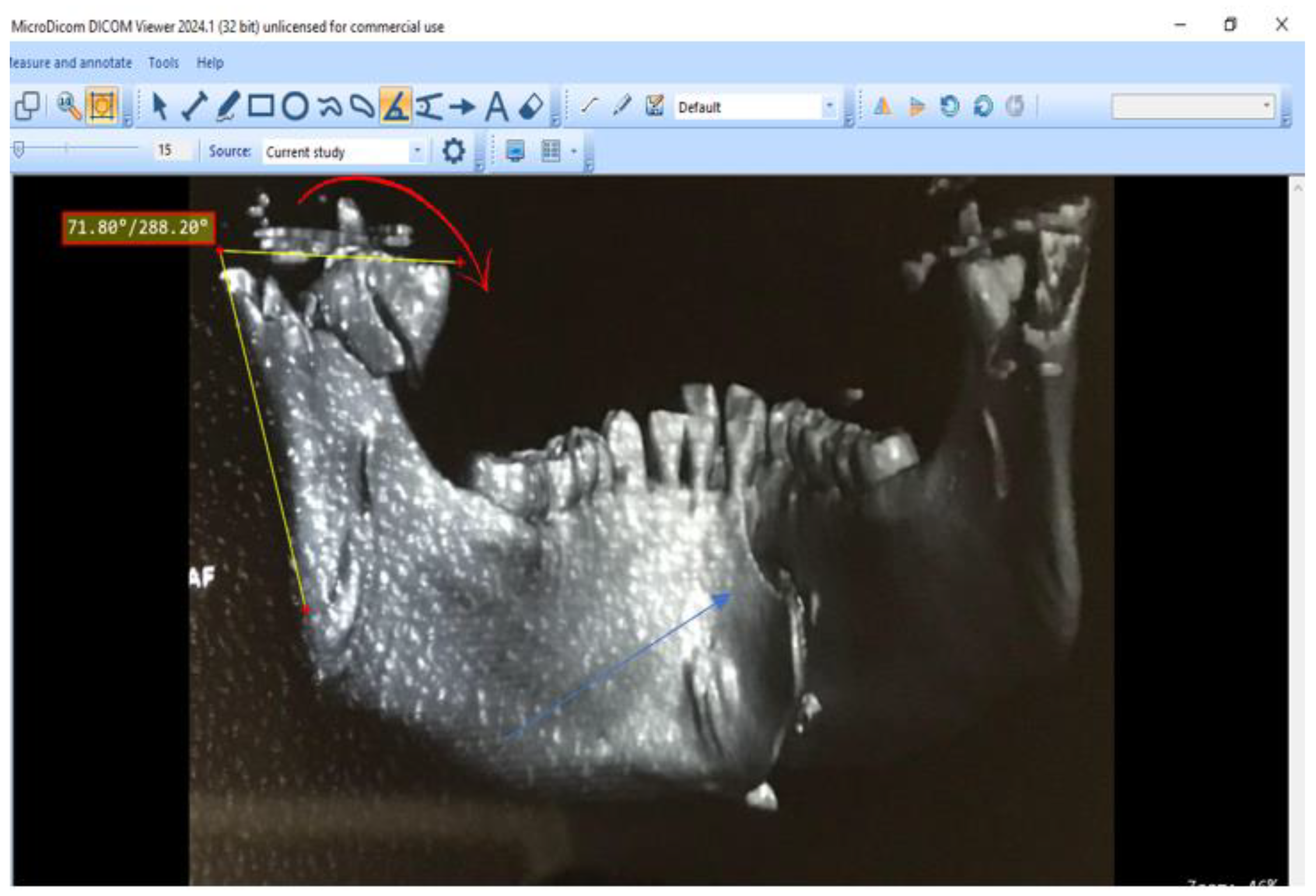

2.3. Imaging Analysis

2.4. Study Variables

- Sociodemographic characteristics: age, sex, and fracture etiology.

- Scannographic findings: fracture location (symphyseal, body, angle, etc.), type of fracture, extension to adjacent areas, involvement of the alveolar process, bone loss, atrophy, displacement, and involvement of the condylar process (base, neck, head), as well as deformation or distortion of the condylar process and changes to the vertical ramus height. The classification of dental injuries was done according to the Dental Trauma Guide.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

- The mean age of participants was 29.8 years, with a standard deviation of ±7.5 years.

- The age group 18-28 was the most represented (50%), followed by 28-38 (40.24%), (Table 1).

- Males represented 89.02% of the study population, yielding a sex-ratio of 8.1.

3.2. Etiology of Fractures

3.3. CT Scan Findings of Mandibular Fractures

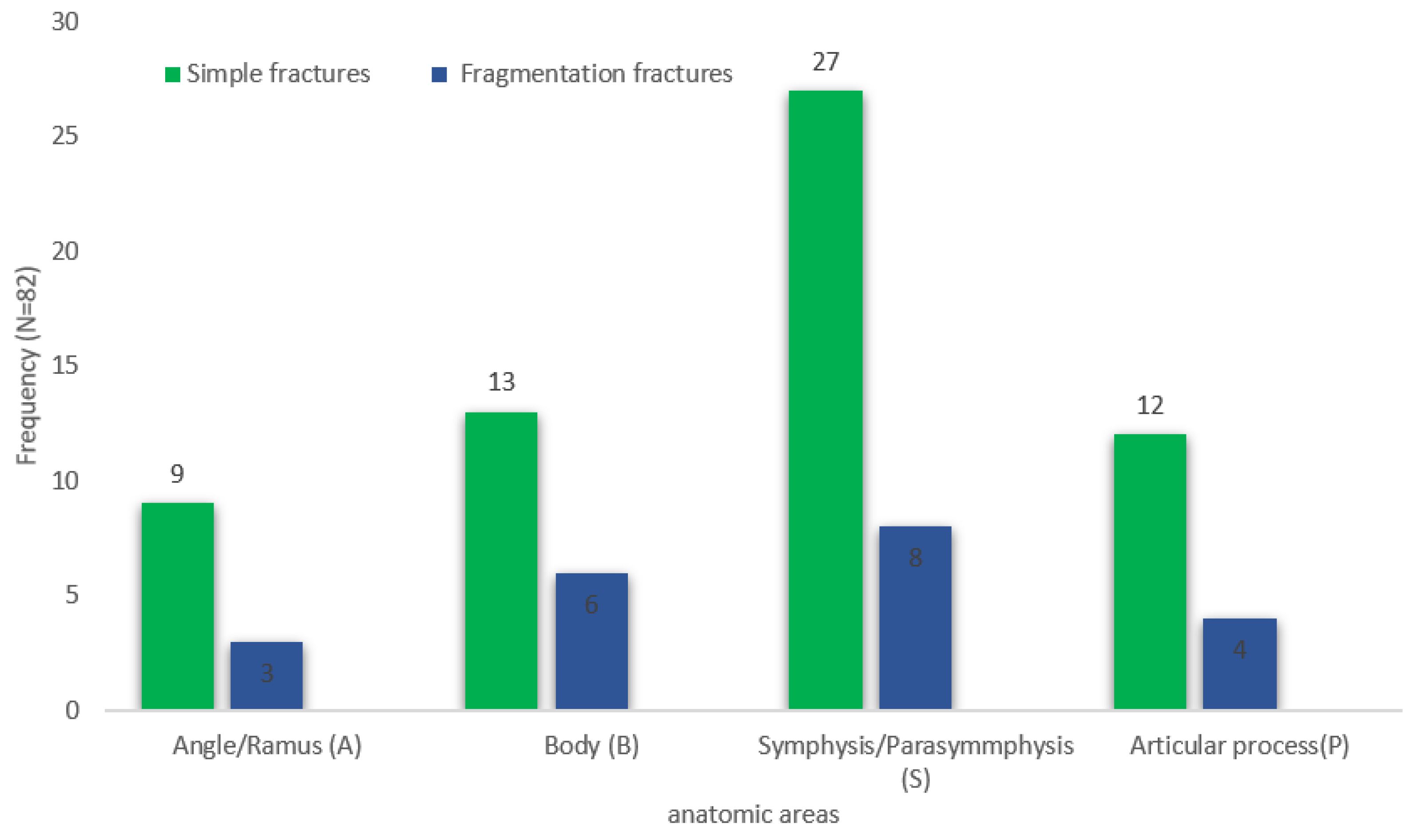

- Mandibular fractures predominantly affected the basal bone (90.2%), with fewer cases involving the alveolar bone (9.8%).

3.4. Dental and Periodontal Lesions

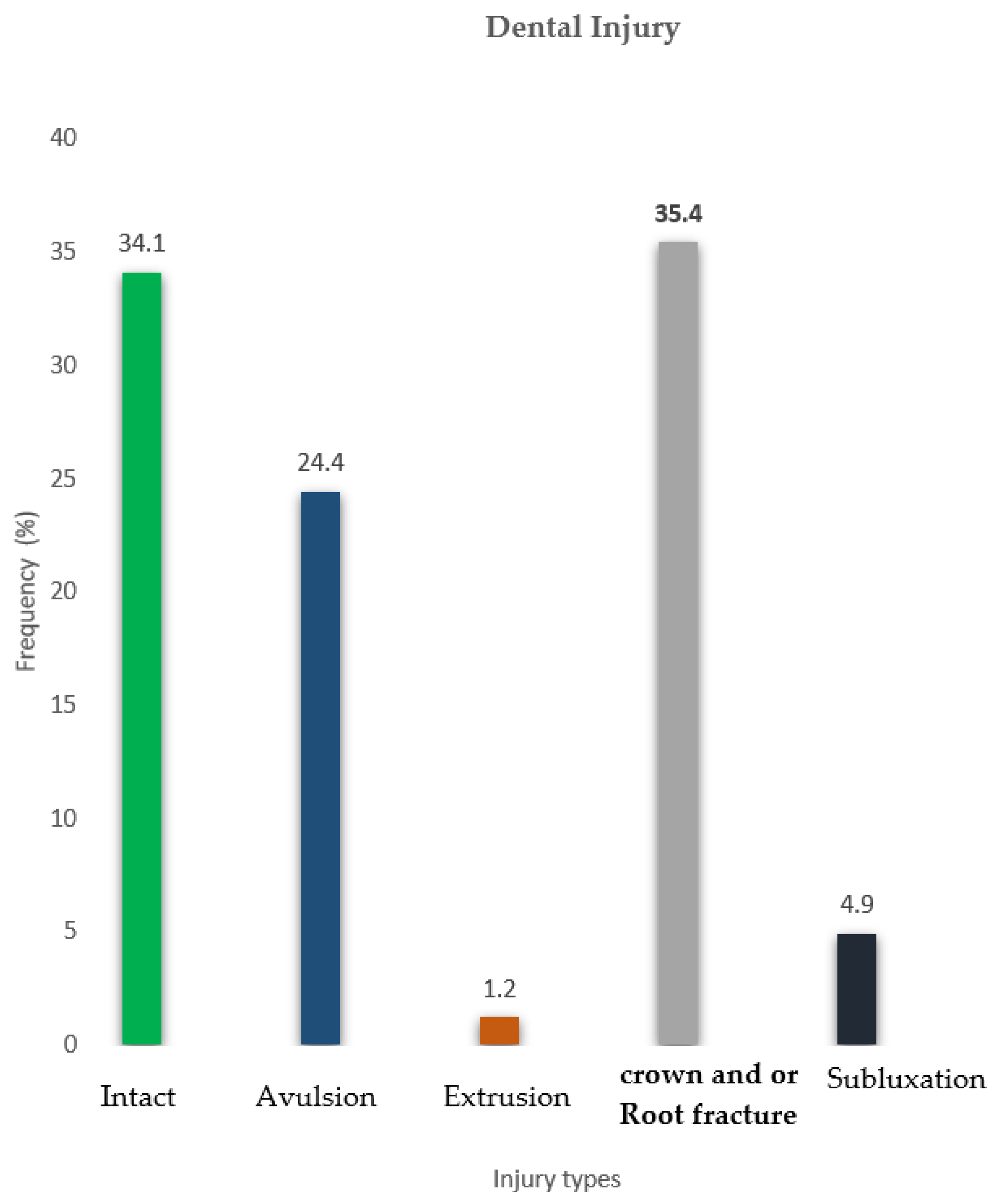

- 67.1% of mandibular fractures affected the alveolar region, with tooth avulsions and coronoradicular fractures accounting for nearly 60% of all cases (Figure 3).

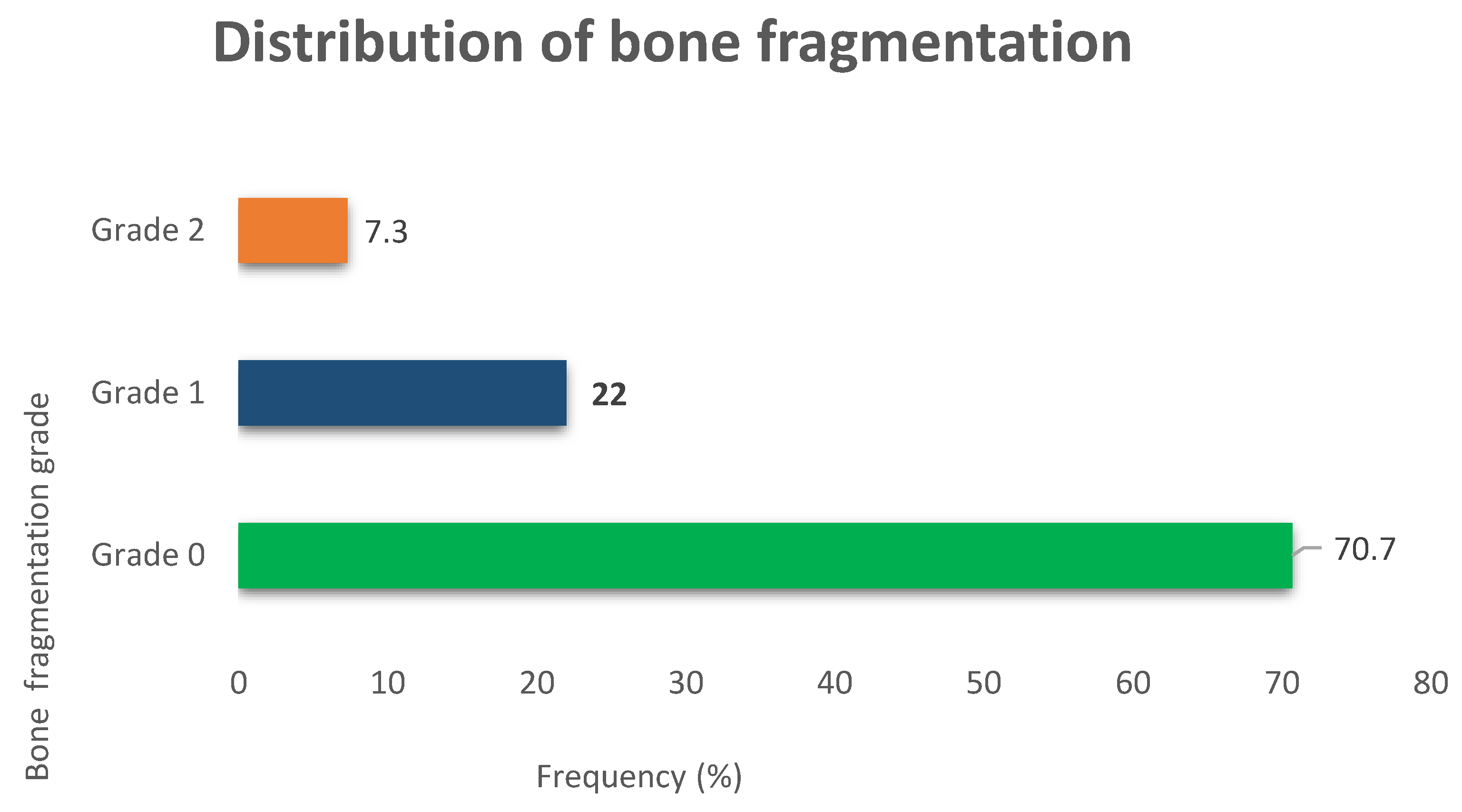

- Minor (Grade 1) and Major (Grade 2) bone fragmentation occurred in 22% and 7.3% of cases, respectively (Figure 4).

- Bone displacement was a significant finding in approximately one-third (31.7%) of cases.

- We observed a relatively low proportion of cases with bone loss (4.9%).

- Most patients (97.6%) showed no significant bone resorption, maintaining a mandibular bone height of over 20 mm (Table 5).

3.5. Articular Process Fractures

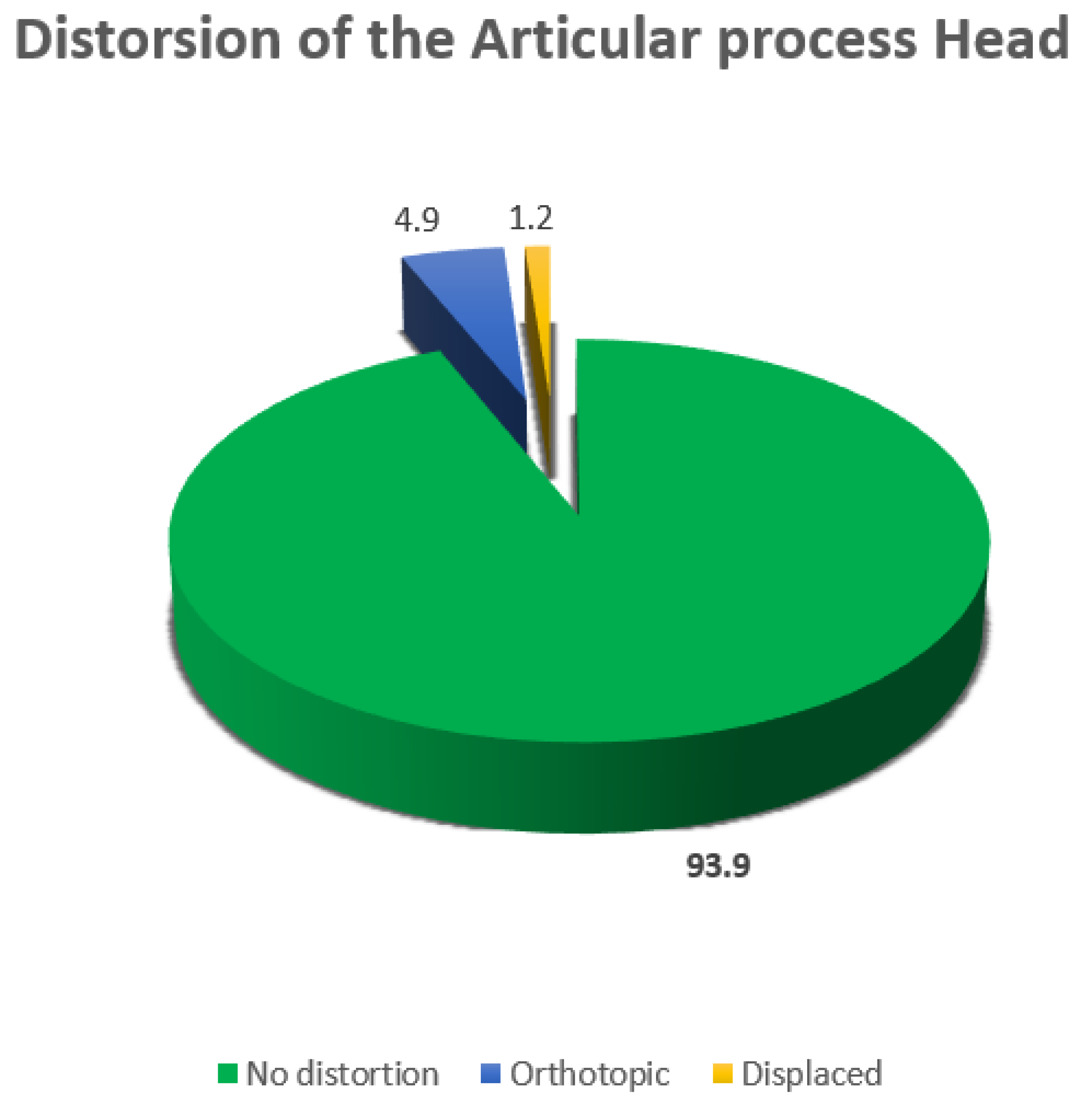

3.6. Articular Process Head Distortion

- A majority of mandibular fractures (93.9%) showed no distortion of the articular process head. 4.9% had in situ distortion, and 1.2% had displaced distortion (Figure 5).

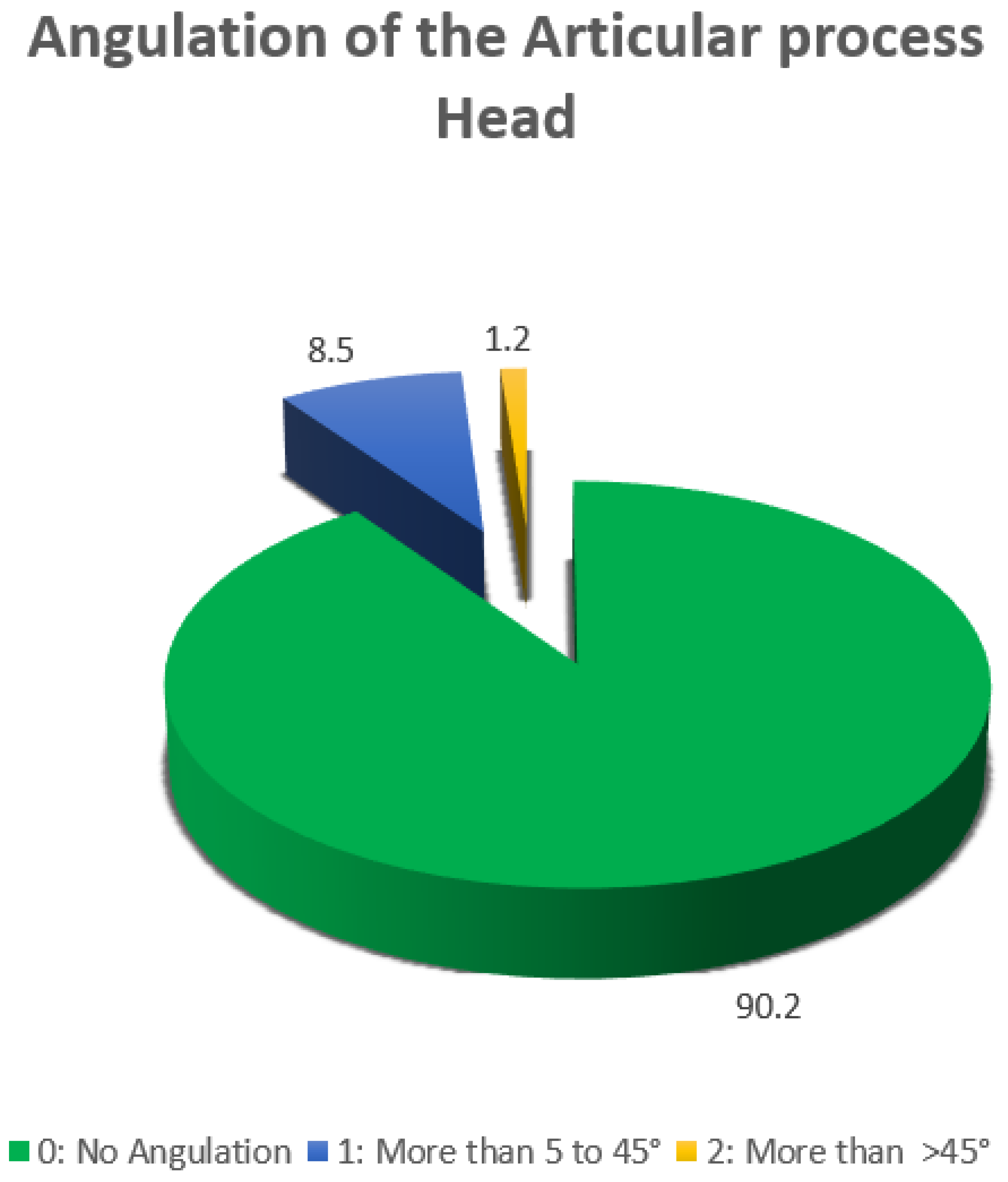

- Mandibular fractures did not alter the vertical ramus height in 91.5% of cases, while 8.5% showed loss of height.

3.7. Classification of Mandibular Fractures: AO CMF Coding Framework

4. Discussion

4.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics

4.2. Etiology of Fractures

4.3. CT Scan Features

4.3.1. Fracture Configuration

4.3.2. Anatomical Distribution

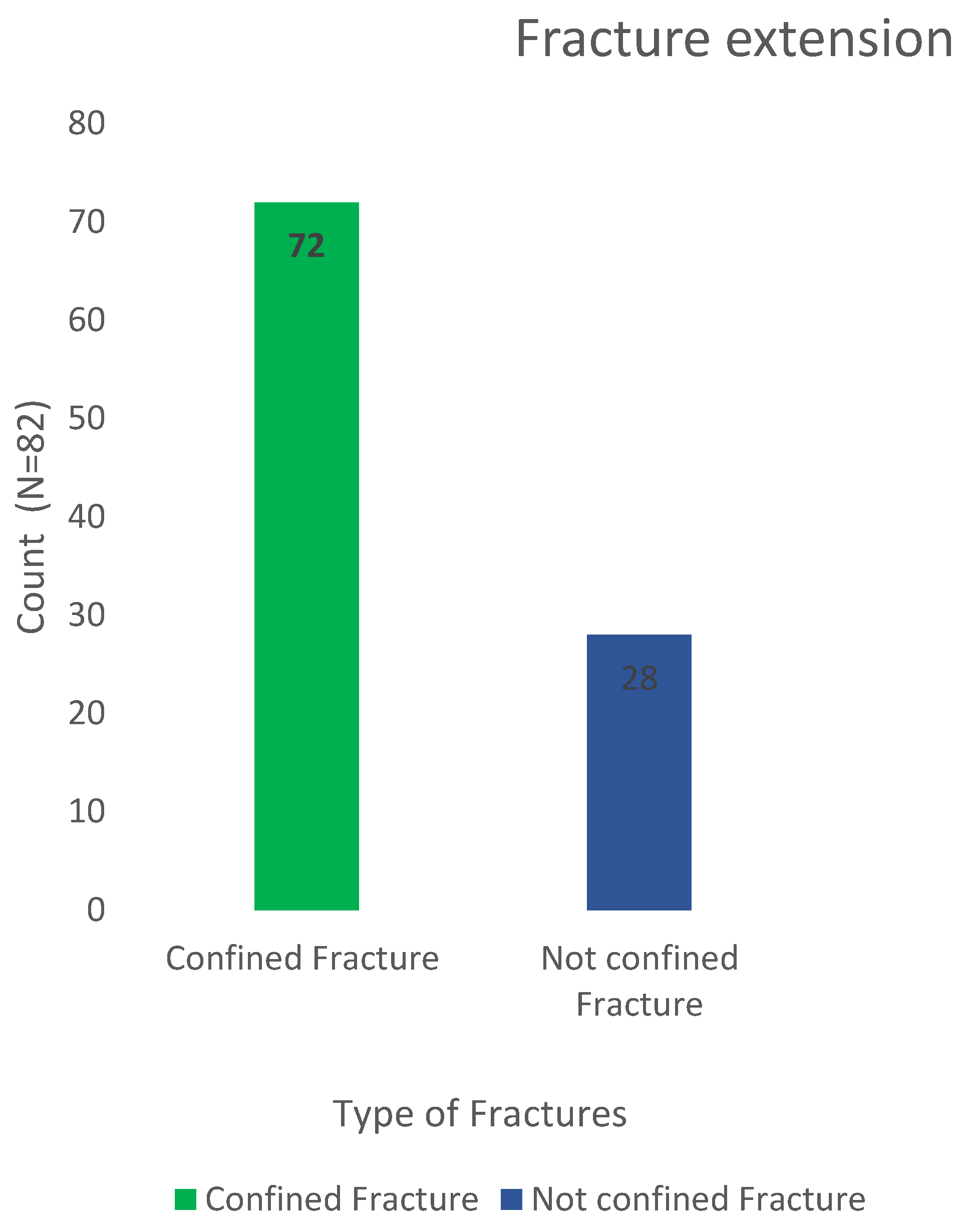

4.3.3. Fracture Extension

4.3.4. Alveolar Process Involvement

4.3.5. Dental Injuries

4.4. Bone Loss and Atrophy

4.5. Bone Fragmentation

4.6. Displacement

4.7. Fractures in the Anatomical Areas of the Articular Process

4.8. Angulation

5. Limitations of the Study

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Salonen, E.M.; Koivikko, M.P.; Koskinen, S.K. Acute facial trauma in falling accidents: MDCT analysis of 500 patients. Emerg. Radiol. 2008, 15, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denhez, F.; Giraud, O.; Seigneuric, J.B.; Paranque, A.R. Fractures de la mandibule. EMC Stomatologie 2005, 22-070-A-12. [Google Scholar]

- Sanogo, S. Apport de la tomodensitométrie (TDM) dans les traumatismes du massif facial dans le service d’imagerie médicale de l’hôpital de Sikasso: étude rétro prospective et prospective à propos de 100 cas. Thesis, Université du Mali, Mali, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Messina, E.; Okala, P.; Ngaba, O.; Edouma, J.; Bombah, F.; Ongolo, P.; et al. Aspects cliniques et scanographiques des traumatismes mandibulaires à l’Hôpital Central de Yaoundé. Health Sci. Dis. 2020, 21, 88–90. [Google Scholar]

- Sanogo, S.; Kouma, A.; Cissé, I.; Guindo, I.; Diarra, O.; Traoré, O.; et al. Profil épidémiologique et tomodensitométrique des fractures maxillo-faciales post-traumatiques à Mopti au Mali. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2022, 41, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herve, V. Les traumatismes maxillo-faciaux et leurs implications en pratique odontologique: intérêts d’une approche pluri-disciplinaire. Thesis, Université de France, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mittermiller, P.A.; Bidwell, S.S.; Thieringer, F.M.; Cornelius, C.P.; Trickey, A.W.; Kontio, R.; et al. The Comprehensive AO CMF Classification System for Mandibular Fractures: A Multicenter Validation Study. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2019, 12, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.T.; Chiu, Y.W.; Chang, Y.C.; Lin, C.W. Ten-year retrospective study on mandibular fractures in central Taiwan. J. Int. Med. Res. 2020, 48, 300060520915059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boffano, P.; Kommers, S.C.; Karagozoglu, K.H.; Gallesio, C.; Forouzanfar, T. Mandibular trauma: a two-centre study. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 44, 998–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshy, J.R.; Msemakweli, B.S.; Owibingire, S.S.; Sohal, K.S. Pattern of mandibular fractures and helmet use among motorcycle crash victims in Tanzania. Afr. Health Sci. 2020, 20, 789–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeleke, A.I.; Hlongwa, M.; Makhunga, S.; Ginindza, T.G. Epidemiology of maxillofacial injuries in adults in sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review. Inj. Epidemiol. 2023, 10, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrooz, P.N.; Bykowski, M.R.; James, I.B.; Daniali, L.N.; Clavijo-Alvarez, J.A. The Epidemiology of Mandibular Fractures in the United States, Part 1: A Review of 13,142 Cases from the US National Trauma Data Bank. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 73, 2361–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, M.; Tamba, B.; Gassama, C.B.; Diatta, M.; Ba, A.; Kounta, A.; et al. Clinical and radiological aspects of mandibular fractures: A review of 128 cases. Int. J. Oral Health Dent. 2021, 7, 282–286. [Google Scholar]

- Anyanechi, C.E.; Saheeb, B.D. Mandibular sites prone to fracture: analysis of 174 cases in a Nigerian tertiary hospital. Ghana Med. J. 2011, 45, 111–114. [Google Scholar]

- Sandeep Reddy, B.; Naik, D.; Kenkere, D. Role of multidetector computed tomography in evaluation of maxillofacial trauma. Cureus 2023, 15, e34910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouguila, J. Epidemiology of maxillo-facial traumatology in Tunis. Rev. Stomatol. Chir. Maxillofac. 2008, 109, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.M.; Homsi, N.; Pereira, C.C.; Jardim, E.C.; Garcia, I.R. Jr. Epidemiological evaluation of mandibular fractures in a high-complexity hospital in Rio de Janeiro. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2011, 22, 2026–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngaba Mambo, Y.; Yousse Moungang, D.; Zing, S.; Bengondo Messanga, C. Maxillofacial fractures due to road traffic accidents: epidemiological and clinical aspects in three hospitals in the city of Yaoundé. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Rev. 2021, 3, 1529–1533. [Google Scholar]

- Rocton, S.; Chaine, A.; Ernenwein, D.; Bertolus, C.; Rigolet, A.; Bertrand, J.C.; et al. Fractures de la mandibule: épidémiologie, prise en charge thérapeutique et complications d’une série de 563. Rev. Stomatol. Chir. Maxillofac. 2007, 108, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keubou, B.L.; Dsongwa, K.A.; Bengondo, M.C. Aspects épidémiologiques et cliniques des fractures mandibulaires traitées par procédé orthopédique à l’hôpital de district de Kumba, Cameroun. Health Sci. Dis. 2017, 18. Available online: http://www.hsdfmsb.org/index.php/hsd/article/view/938 (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Bicsák, Á.; Abel, D.; Berbuesse, A.; Hassfeld, S.; Bonitz, L. Evaluation of mandibular fractures in a German nationwide trauma center between 2015 and 2017. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2022, 21, 904–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieger, O.; Zix, J.; Kruse, A.; Iizuka, T. Dental injuries associated with facial fractures. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2009, 67, 1680–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbor, A.M.; Azodo, C.C.; Ebot, E.B.; Naidoo, S. Dentofacial injuries in commercial motorcycle accidents in Cameroon: pattern and cost implication of care. Afr. Health Sci. 2014, 14, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thapa, S.; Wang, J.; Hu, H.T.; Zhang, F.G.; Ji, P. Epidemiology of surgically managed mandibular condylar fractures at a tertiary referral hospital in urban Southwest China. Open Dent. J. 2017, 11, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marker, P.; Nielsen, A.; Bastian, H.L. Fractures of the mandibular condyle. Part 1: patterns of distribution of types and causes of fractures in 348 patients. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2000, 38, 417–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Age range | Count (N = 82) | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 18-28 | 41 | 50 1 |

| 29-38 | 33 | 40.24 |

| 39-48 | 6 | 7.32 |

| 49+ | 2 | 2.44 |

| Total | 82 | 100 |

| Etiology | Count (N=82) | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| RTA (Road Traffic Accidents) | 58 | 70.7 |

| Falls | 10 | 12.2 |

| Assault | 7 | 8.5 |

| Fights | 7 | 8.5 |

| Etiology | Female (N=9) | Male (N=73) |

|---|---|---|

| RTA (Road Traffic Accidents) | 4 (44.44%) | 54 (73.97%) |

| Falls | 2 (22.22%) | 8 (10.96%) |

| Assault | 0 (0%) | 7 (9.59%) |

| Fights | 3 (33.33%) | 4 (5.48%) |

| Location | Simple fracture | Fragmentation fracture |

|---|---|---|

| Symphysis/Parasymphysis | 27 | 8 |

| 32.93% | 9.76% | |

| Body | 13 | 6 |

| 15.85% | 7.32% | |

| Articular process | 12 | 4 |

| 19.67% | 19% | |

| Angle/Ramus | 9 | 3 |

| 15.75% | 14.28% |

| Bone Loss Severity | Count (N=82) | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| No bone loss, Mandibular vertical height > 20 mm |

80 | 97.6 |

| Minimal bone loss, Mandibular vertical height > 15 to 20 mm |

2 | 2.4 |

| Region | Count (N=82) | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Base | 2 | 2.4 |

| Neck | 9 | 11 |

| Head | 5 | 6.1 |

| Other locations | 66 | 80.5 |

| Displacement Type | Count (N=82) | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Non-displaced | 56 | 68.3 |

| Partial | 15 | 18.3 |

| Complete | 9 | 11 |

| Dislocation | 2 | 2.4 |

| AO CMF Code | Count (N=82) | Fracture Description |

|---|---|---|

| 91A | 3 | Simple and confined fracture of the Angle/Ramus region |

| 91A-CB | 1 | Bifocal simple and confined fracture of the Angle/Ramus region on the right and the base of the condylar process (CP) on the left |

| 91A1a | 1 | Grade 1 fragmentation fracture of the Angle/Ramus region with involvement of the alveolar process |

| 91A2 | 1 | Grade 2 fragmentation fracture of the Angle/Ramus region |

| 91A2-CB | 1 | Grade 2 fragmentation fracture of the Angle/Ramus region on the right and the base of the CP on the left |

| 91Aa | 4 | Simple and confined fracture of the Angle/Ramus region with involvement of the alveolar process |

| 91B | 3 | Simple and confined fracture of the mandibular body (Corpus) |

| 91B1a | 3 | Grade 1 fragmentation fracture of the mandibular body with involvement of the alveolar process |

| 91B-BA | 1 | Bilateral simple fracture confined to the right mandibular body and extending to the left Angle/Ramus region |

| 91B2-B | 1 | Grade 2 fragmentation fracture of the right mandibular body and simple contralateral body fracture |

| 91Ba | 6 | Simple and confined fracture of the mandibular body with involvement of the alveolar process |

| 91Ba-A | 2 | Simple fracture of the mandibular body with involvement of the alveolar process extending to the Angle/Ramus region |

| 91Ba-CN | 1 | Bifocal simple and confined fracture of the mandibular body with involvement of the alveolar process on the right and of the CP head on the left |

| 91Ba-S | 1 | Bifocal simple fracture of the mandibular body with involvement of the alveolar process extending to the Symphysis/Parasymphysis region |

| 91CB | 2 | Simple fracture of the CP base |

| 91CB1 | 1 | Grade 1 fragmentation fracture of the CP base |

| 91CH1p1 | 1 | Grade 1 fragmentation fracture of the CP head with anterior displacement of the caudal fragment and 1st-degree angulation |

| 91CHl | 1 | Grade 1 fragmentation fracture of the CP head |

| 91CHl1 | 1 | Simple fracture of the CP head with medial displacement of the caudal fragment and 1st-degree angulation |

| 91CHm1 | 1 | Simple fracture of the CP head with medial displacement of the caudal fragment and 1st-degree angulation |

| 91CHp | 1 | Simple fracture of the CP head with anterior displacement of the caudal fragment |

| 91CN | 3 | Simple fracture of the CP neck |

| 91CN2-Sa | 1 | Bifocal Grade 2 fragmentation fracture of the CP neck on the right and simple fracture of the Symphysis/Parasymphysis region with involvement of the alveolar process |

| 91CNa | 2 | Simple fracture of the CP neck with ipsilateral alveolar process involvement |

| 91CNm1 | 1 | Simple fracture of the CP neck with medial displacement of the caudal fragment and 1st-degree angulation |

| 91S | 4 | Simple fracture of the Symphysis/Parasymphysis region |

| 91S-CB | 1 | Bifocal simple and confined fracture of the Symphysis/Parasymphysis region on the right and the contralateral CP base |

| 91S-CHl1 | 1 | Bifocal simple fracture of the Symphysis/Parasymphysis region on the right and the CP head on the left with lateral displacement of the caudal fragment and 1st-degree angulation |

| 91S1-CHm | 1 | Bifocal Grade 1 fragmentation fracture of the Symphysis/Parasymphysis region and the CP head on the left with medial displacement of the caudal fragment |

| 91S1a | 3 | Grade 1 fragmentation fracture of the Symphysis/Parasymphysis region with ipsilateral alveolar process involvement |

| 91S1a-B | 2 | Grade 1 fragmentation fracture of the right Symphysis/Parasymphysis region with ipsilateral alveolar process involvement extending to the left body |

| 91S1a-Ba | 1 | Grade 1 fragmentation fracture of the right Symphysis/Parasymphysis region extending to the left body with bilateral alveolar process involvement |

| 91S1a-CN | 2 | Grade 1 fragmentation fracture of the right Symphysis/Parasymphysis region with ipsilateral alveolar process involvement and simple CP neck fracture |

| 91S2a-CHl1 | 1 | Grade 2 fragmentation fracture of the right Symphysis/Parasymphysis region with ipsilateral alveolar process involvement and simple CP head fracture with lateral displacement of the caudal fragment |

| 91Sa | 15 | Simple fracture of the right Symphysis/Parasymphysis region with ipsilateral alveolar process involvement |

| 91Sa-B | 1 | Simple fracture of the right Symphysis/Parasymphysis region with alveolar process involvement extending to the left body |

| 91Sa-Ba | 1 | Simple fracture of the right Symphysis/Parasymphysis region extending to the left body with bilateral alveolar process involvement |

| 91Sa-CHl1 | 1 | Bifocal simple fracture of the right Symphysis/Parasymphysis region with alveolar process involvement and left CP head fracture with lateral displacement and 1st-degree angulation |

| 91B1a-S | 1 | Grade 1 fragmentation fracture of the alveolar process in the body region on the right extending to the Symphysis/Parasymphysis |

| 91S1ad | 1 | Grade 1 fragmentation fracture of the alveolar process in the Symphysis/Parasymphysis region with bone loss |

| 91Sa | 1 | Simple fracture of the alveolar process in the Symphysis/Parasymphysis region |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).