Submitted:

05 June 2025

Posted:

05 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

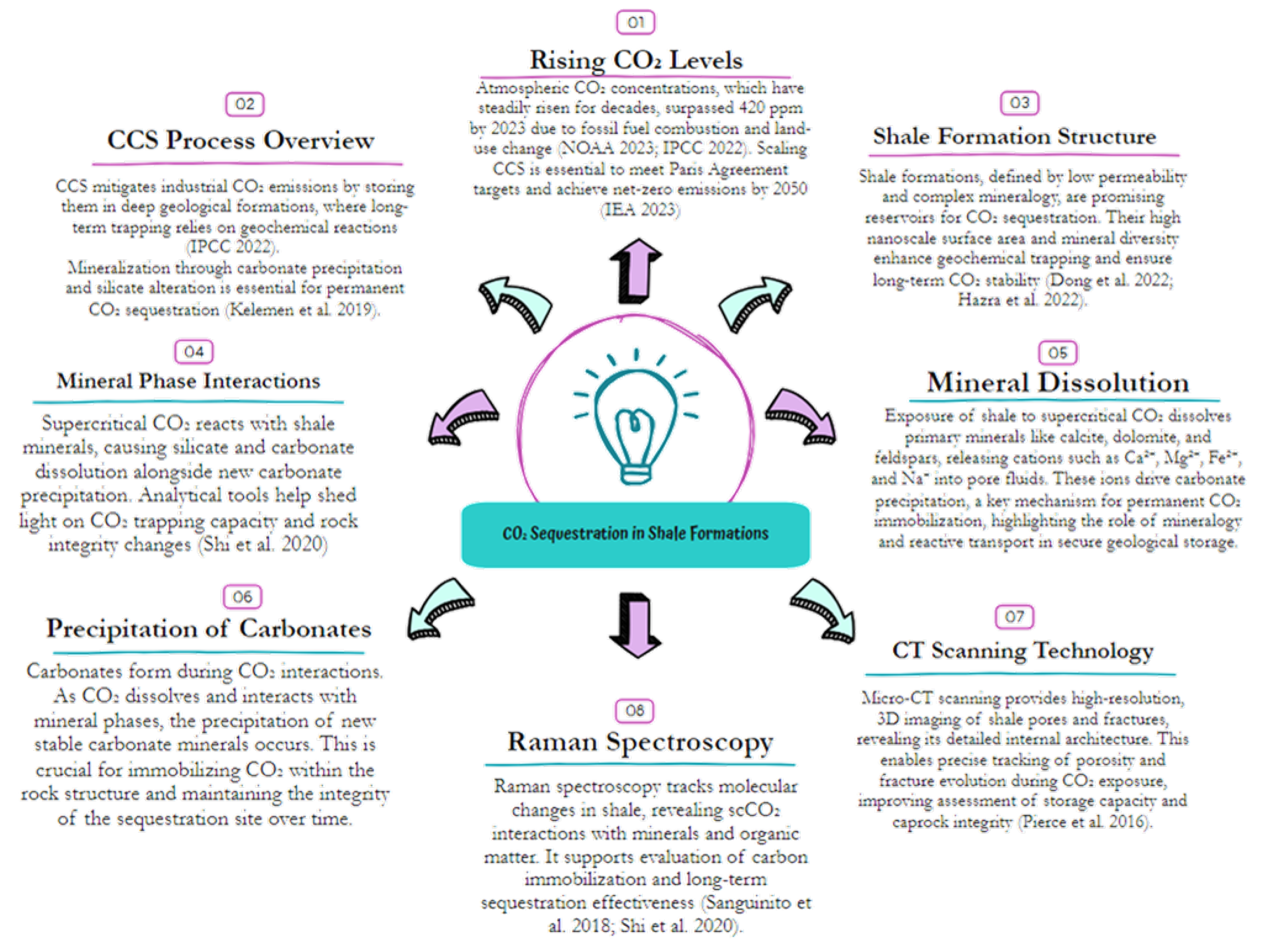

1. Introduction

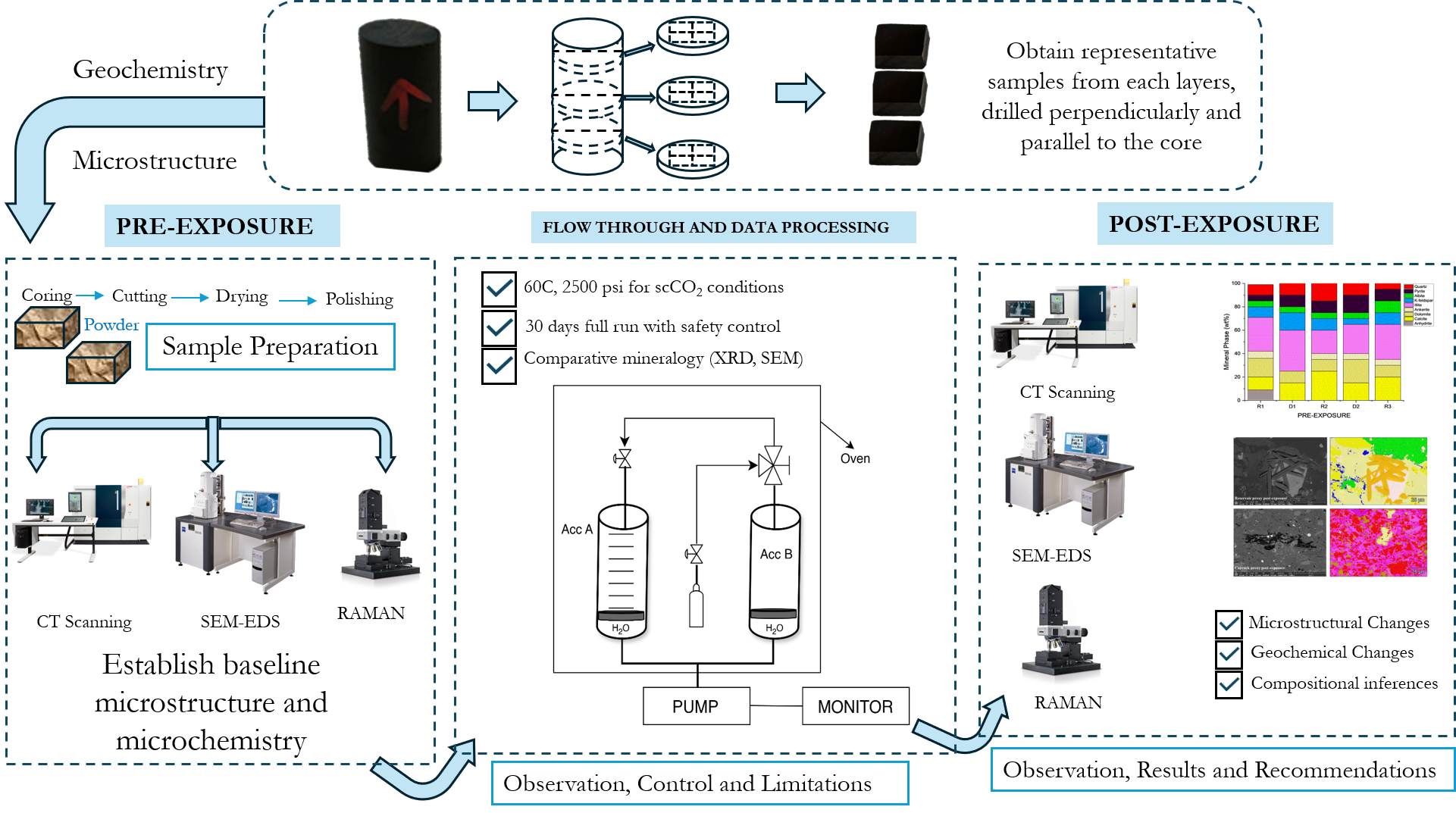

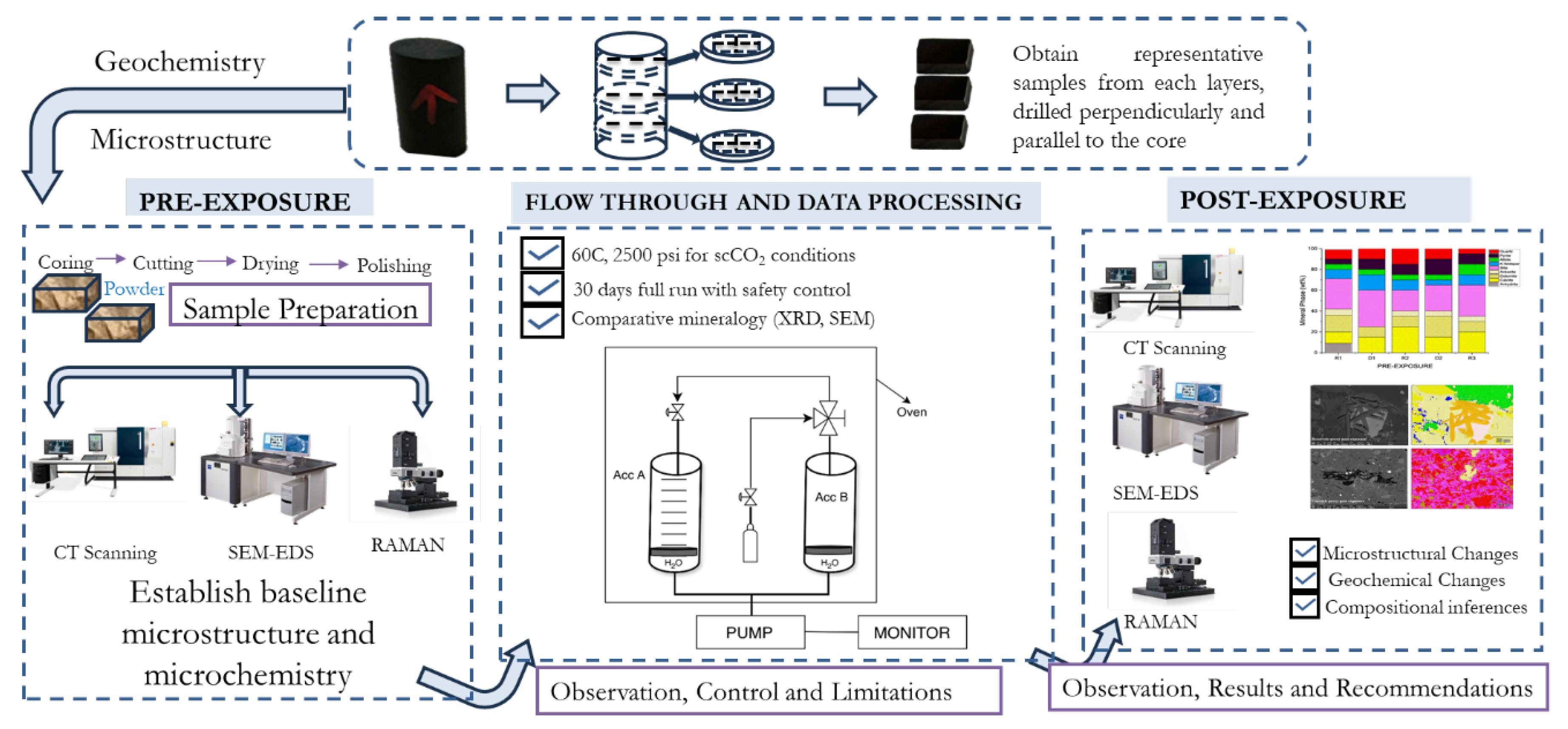

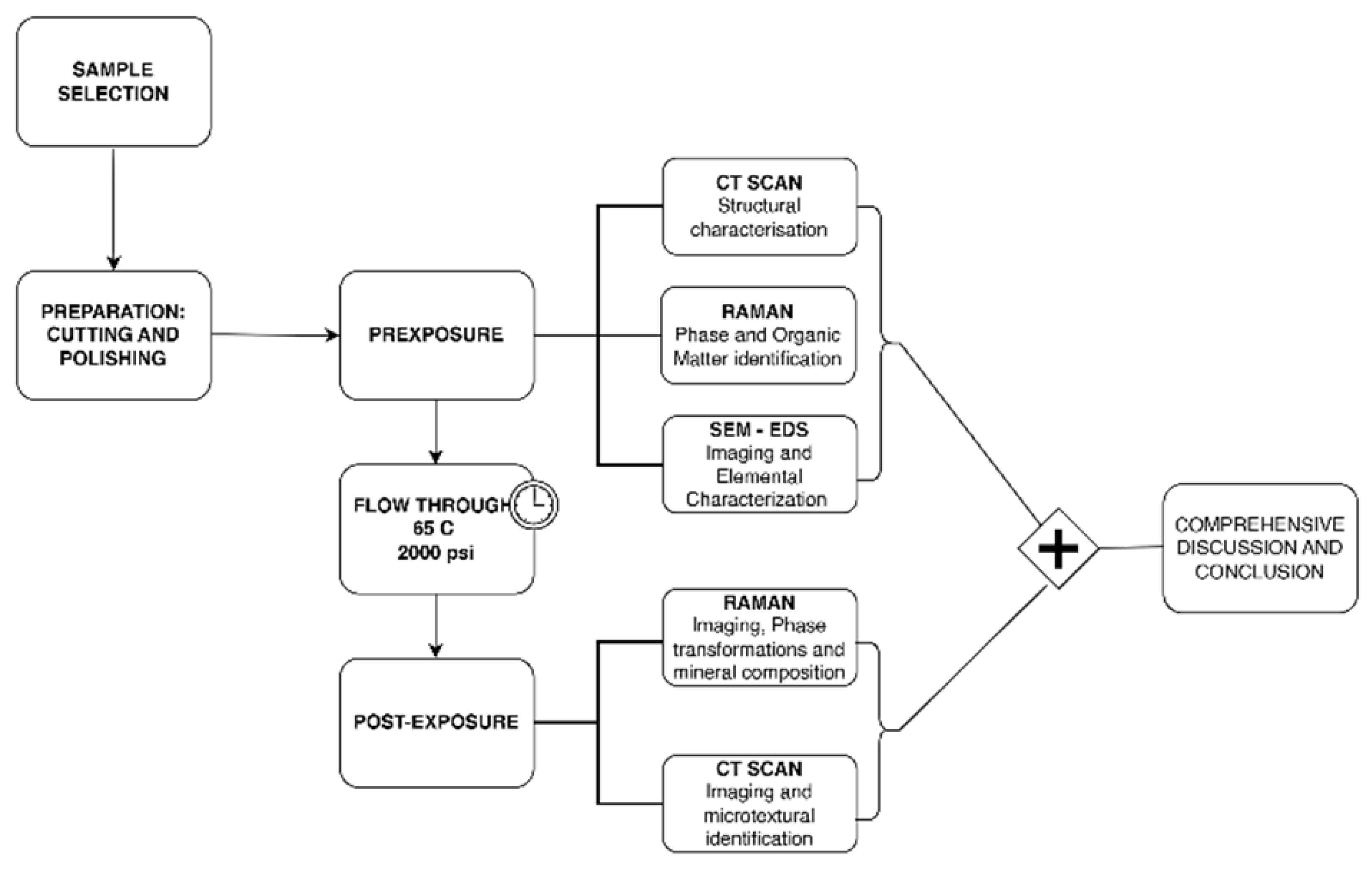

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

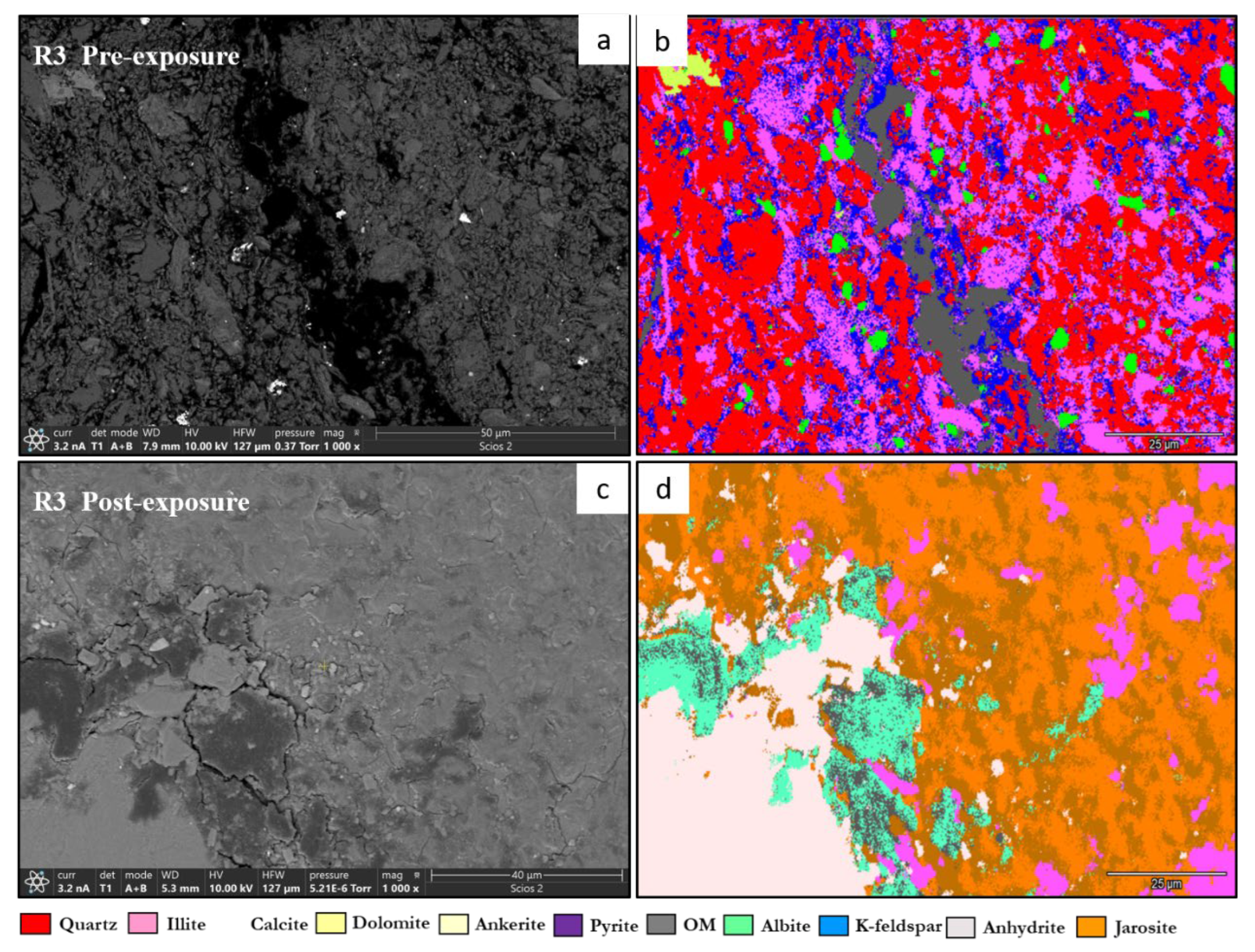

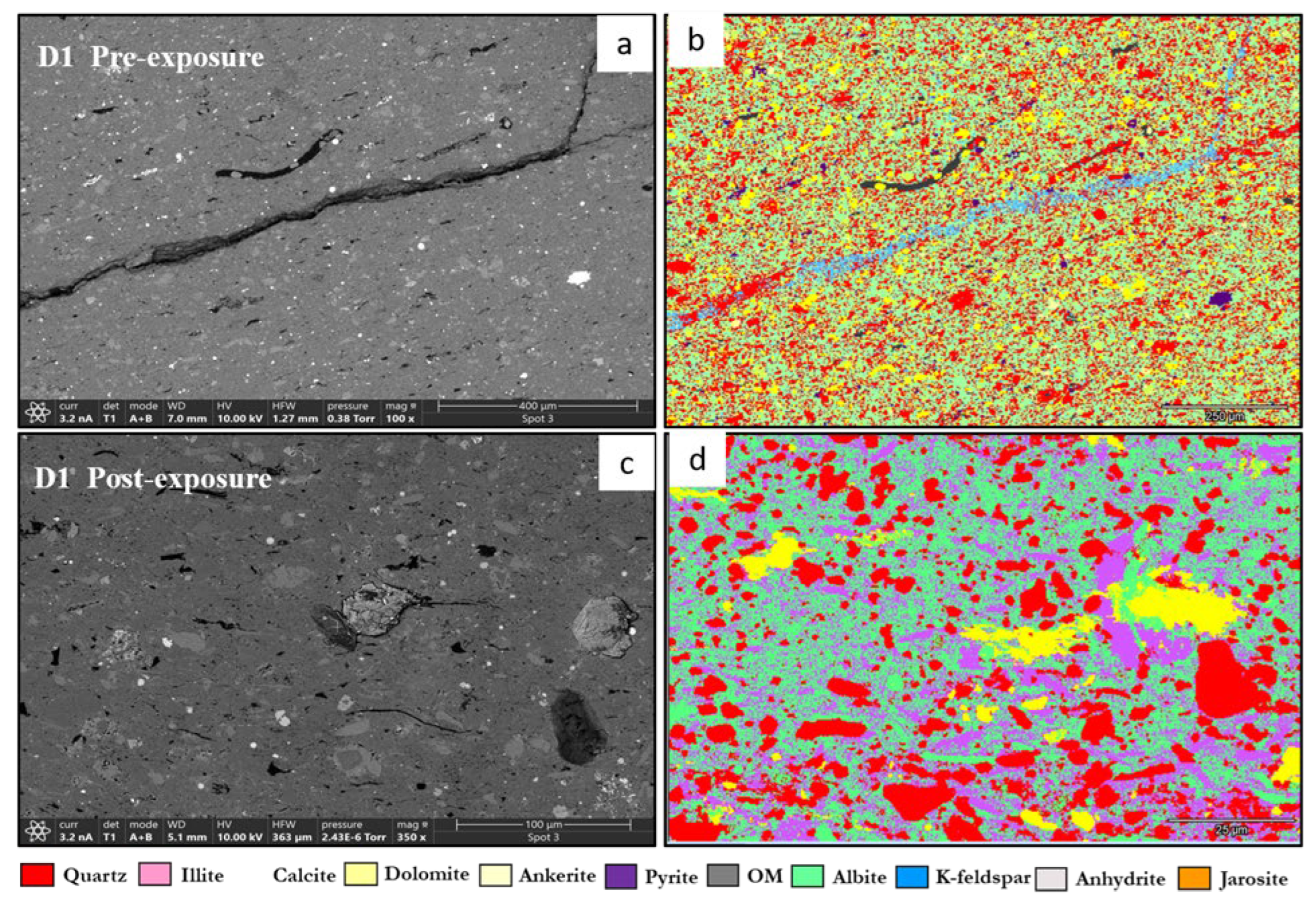

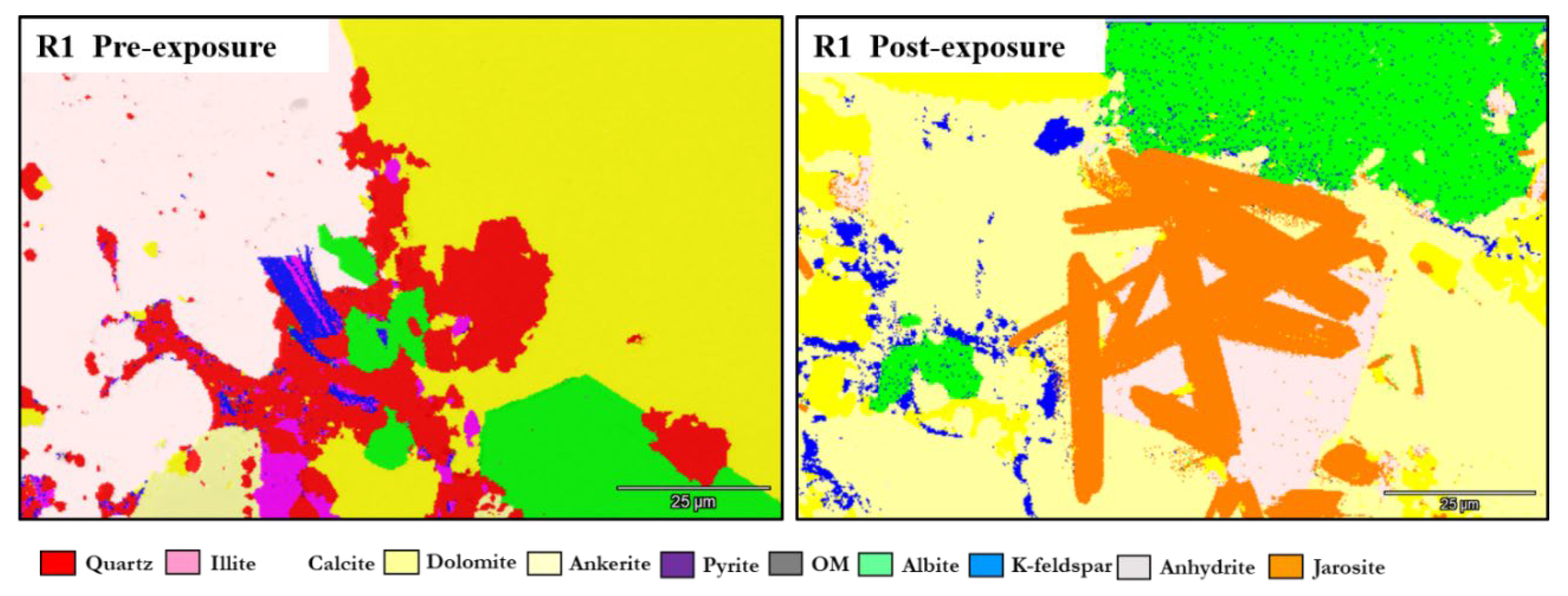

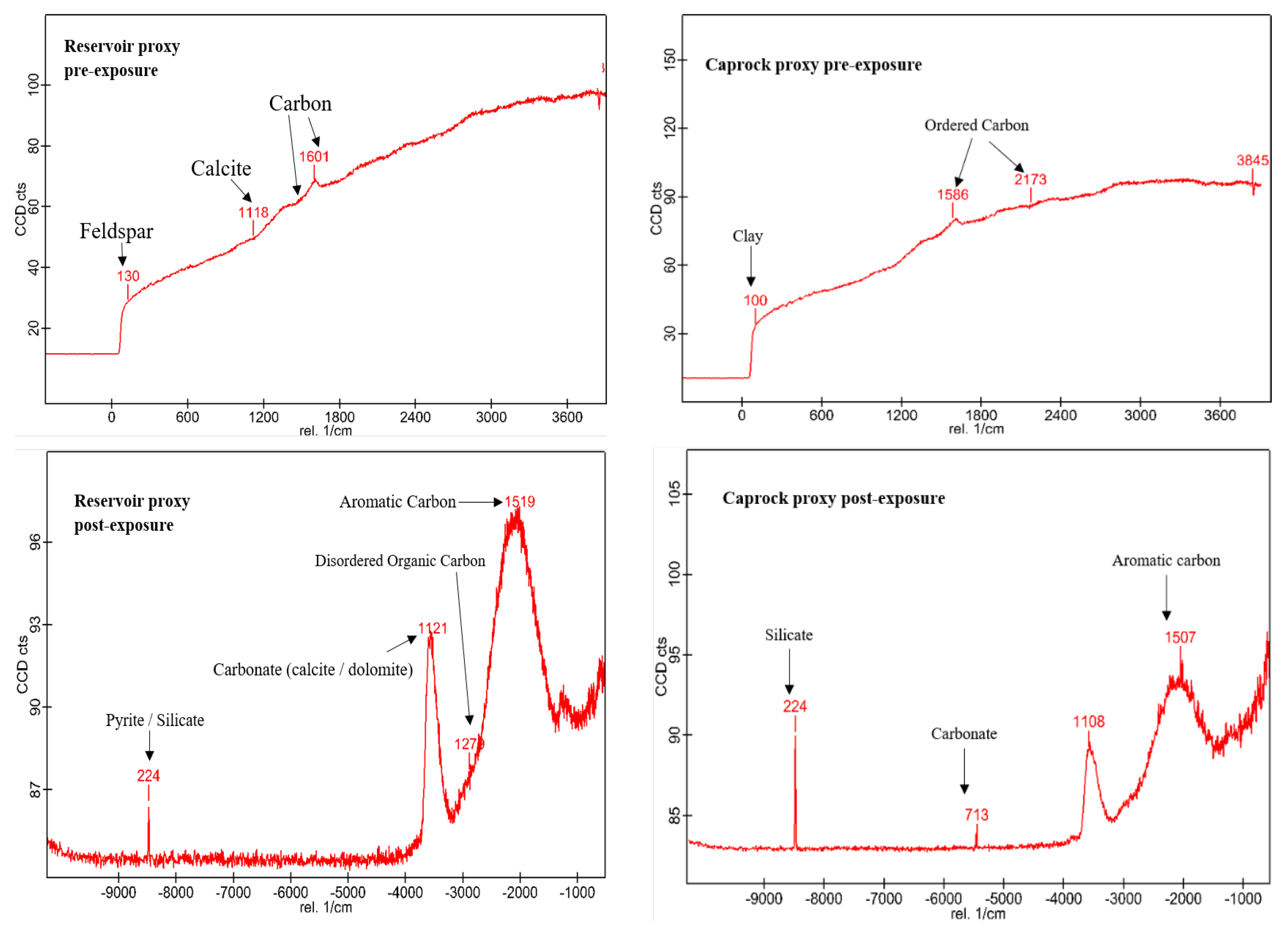

3.1. Mineral Phase Identification

- Quartz remained the principal framework silicate across all facies. In reservoir proxies, pre-exposure abundances were 43.77% (R1), 42.23% (R2), and 45.96% (R3), with post-exposure values of 43.94%, 42.22%, and 45.68%, respectively. In caprock proxies, quartz accounted for 33.79% (D1) and 33.69% (D2) prior to exposure, increasing marginally to 34.13% and 32.75% post-exposure. Across all facies, quartz grains retained angular, sharp morphologies with no significantly observable structural or chemical alteration

- K-Feldspar (KAlSi3O₈). K-feldspar was consistently present in all samples. In reservoirs, values ranged from 5.06% to 5.84% pre-exposure and from 5.89% to 5.99% post-exposure. In D1 and D2, K-feldspar was measured at 7.06% and 6.54% pre-exposure, increasing slightly to 7.13% and 6.36% post-exposure. No dissolution or surface roughening was evident under SEM imaging.

- Illite [(K,H3O)(Al,Mg,Fe)2(Si,Al)4O₁₀(OH)2]. Illite occurred in all facies and was typically distributed along grain boundaries or within clay-rich matrices. Pre-exposure content ranged from 17.61% (R3) to 18.40% (R2), and post-exposure values decreased slightly to 17.69%–18.67%. In ductile samples, illite was recorded at 17.26% (D1) and 16.68% (D2) before exposure, declining to 17.47% and 16.31%, respectively. Platy textures remained intact, although localized thinning and roughening of particle edges were noted in R2 and R3.

- Kaolinite (Al2Si2O₅(OH)4). Kaolinite was identified in D1 and D2. Pre-exposure values were 10.03% (D1) and 9.89% (D2), increasing slightly to 10.13% and 9.76%, respectively, post-exposure. Kaolinite maintained blocky morphology with no signs of chemical erosion or micro-pitting.

- Paragonite (NaAl2(Si3Al)O₁₀(OH)2). Paragonite was not detected in any sample prior to exposure. Post-exposure, it appeared in R2 (0.38%), R3 (0.88%), D1 (0.72%), and D2 (0.90%). It was typically observed near altered illite flakes and within fine-grained matrix zones, forming as secondary Na-bearing phyllosilicate lamella.

- Calcite (CaCO3). Calcite was present in all samples, particularly in the reservoir facies. In R1–R3, calcite decreased slightly from 9.92%, 9.97%, and 8.80% pre-exposure to 9.01%, 8.76%, and 9.05%, respectively. In caprocks, it declined from 9.41% (D1) and 9.62% (D2) to 9.75% and 8.80%, respectively. SEM images revealed surface pitting and edge retreat, especially in R1 and R2.

- Ankerite [Ca(Fe2+,Mg)(CO3)2]. Ankerite occurred in both reservoir and caprock proxies. In R1–R3, pre-exposure values ranged from 4.40% to 5.49%, decreasing post-exposure to 4.08% – 4.33%. In D1, it was not detected pre-exposure and remained absent post-exposure. In D2, it decreased from 4.02% to 3.55%. Morphologies were retained but with localized surface dulling near grain boundaries.

- Wollastonite (CaSiO3). Wollastonite was absent prior to exposure and formed in all samples post-exposure. In R1–R3, abundances were 0.67%, 1.08%, and 1.02%, respectively. In D1 and D2, wollastonite was recorded at 0.56% and 0.93%. It appeared as fibrous or acicular precipitates localized around sites of prior carbonate dissolution.

- Albite (NaAlSi3O₈). Albite was present in every sample. Pre-exposure values in R1–R3 ranged from 4.88% to 5.96%, decreasing slightly to 5.75%–5.94% post-exposure. In D1 and D2, albite changed from 4.71% and 4.82% to 4.93% and 4.65%, respectively. Grains retained sharp outlines and showed no dissolution features.

- Pyrite (FeS2). Pyrite was present across all facies. In reservoirs, pre-exposure values ranged from 4.88% (R1) to 5.87% (R2), declining to 4.67%–5.41% post-exposure. In D1 and D2, pyrite decreased from 6.28% and 6.26% to 5.56% and 4.84%, respectively. SEM showed edge diffusion and oxidation halos near OM and clay interfaces in caprock samples.

- Jarosite [KFe3(SO4)2(OH)6]. No jarosite was detected prior to exposure. It was identified post-exposure in R3 (0.58%), D1 (1.24%), and D2 (1.49%), with trace detection in R1. No formation was observed in R2. It formed as fine-grained aggregates, frequently bordering pyrite and organic-rich regions.

- Calcium Sulfate (CaSO4). Calcium sulfate was not detected pre-exposure and was present only post-exposure in caprock samples: 0.80% in D1 and 1.07% in D2. It appeared as thin, patchy coatings at mineral boundaries.

3.2. Elemental Mobilization

| Ionic Species |

Primary Mineral Phase Sources | Facies Observed |

Post-Exposure Observation | Possible Geochemical Path |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K+ | K-feldspar, Illite | R1, R2, D1, D2, R3 | K-feldspar reduction (13.6% to 7-10%); slight Illite shift |

Leaching from feldspars and clay edges |

| Na+ | Albite | R1, R3, D2 | Minor Albite decline (5.0% to 2.6-3.4%) |

Limited Na+ exchange |

| Ca2+ | Calcite, Dolomite, Ankerite | R1, R2, R3, D1, D2 | Redistribution among carbonate phases; net Ca2+ preserved | Partial dissolution and re-precipitation |

| Mg2+ | Dolomite, Illite, Ankerite | R2, R3, D2, D1 | Mg-bearing carbonates reduced; Dolomite often retained | Phase transition and reallocation |

| Fe2+ / Fe³+ | Pyrite, Illite, Ankerite | D1, D2, R2, R3 | Pyrite decreased (up to 50%); Fe detected near former grains |

Oxidation and surface destabilization |

| SO42⁻ | Anhydrite, Pyrite | R1, D1, D2, R2, R3 | Anhydrite loss, S redistributed | Sulfate release from dissolution/oxidation |

| Al³+ | K-feldspar, Albite, Illite | All facies | No significant compositional change | Structurally retained in aluminosilicates |

| Si 4+ | Quartz, K-feldspar, Illite, Albite | All facies | Quartz (~24–25%) stable throughout |

Framework remains chemically inert |

|

C (elemental) CO32⁻ |

Calcite, Dolomite, Ankerite | All facies | Carbon and carbonates retained via phase shifts, not net loss | Re-precipitation or phase conversion |

|

S (Elemental) |

Pyrite, Anhydrite | D2, R2, R3 | Sulfur detected post-Anhydrite; diffused spatially | Sulfate migration from sulfates/sulfides |

| P / PO4³⁻ | Apatite, trace organics | D2, R3 (trace levels) |

Stable in isolated inclusions | Largely inert under dry CO2 |

4. Discussion

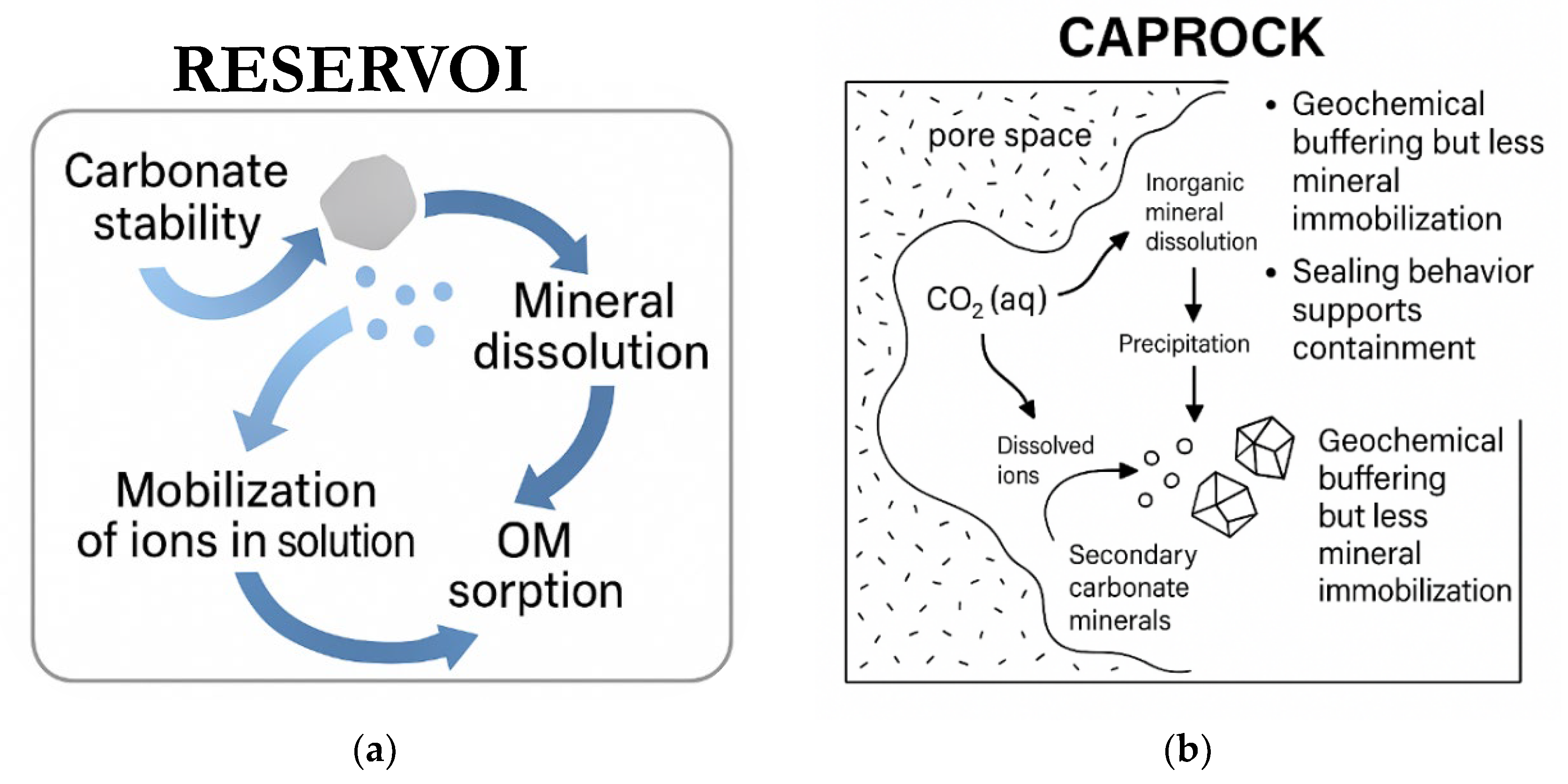

4.1. Mineral Stability and Reactivity

4.1.1. Carbonate Phases

4.1.2. Clays and Feldspars

4.1.2. Sulfide Oxidation and Sulfate Reaction Pathways

4.1.3. Organic Matter: A Chemically Active Interface

4.2. Relevance for Geochemical Sequestration

4.2.1. Reservoir Proxies

4.2.2. Caprock Proxies

4.2.3. Integrated Storage Performance and Relevance for CCS Design

4.3. Geochemical Insights

5. Conclusions

- Localized porosity development enhances CO2 injectivity, while secondary mineral precipitation at grain contacts and pore throats contributes to self-sealing behavior, supporting containment stability.

- Demonstrated mineral trapping in dry scCO2 (no added brines) systems confirms that water is not a prerequisite for initiating geochemical containment, with in situ precipitation providing a viable mechanism for immobilizing (sequestering) injected CO2.

- Facies-dependent reactivity, mineral phase and ionic species distribution support a naturally evolving balance between fluid migration pathways and geochemical seals. This allows reactive zones (reservoirs) to co-exist with stable, low-permeability zones (caprocks).

- Existing shale development from hydraulic fracturing offers an operational advantage, enabling CO2 storage to leverage established well infrastructure, reservoir access strategies, and field-scale monitoring systems.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ndlovu, P.; Bulannga, R.; Mguni, L.L. Progress in Carbon Dioxide Capture, Storage and Monitoring in Geological Landform. Front. Energy Res. 2024, 12, 1450991. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenrg.2024.1450991.

- Olabode, A.; Radonjic, M. Characterization of Shale Cap-Rock Nano-Pores in Geologic CO2 Containment. Environmental & Engineering Geoscience 2014, 20, 361–370. [CrossRef]

- Busch, A.; Amann, A.; Bertier, P.; Waschbusch, M.; Krooss, B.M. The Significance of Caprock Sealing Integrity for CO2 Storage. In Proceedings of the All Days; SPE: New Orleans, Louisiana, USA, November 10 2010; p. SPE-139588-MS.

- Du, H.; Carpenter, K.; Hui, D.; Radonjic, M. Microstructure and Micromechanics of Shale Rocks: Case Study of Marcellus Shale. Facta Universitatis, Series: Mechanical Engineering 2017, 15, 331–340. [CrossRef]

- Hazra, B.; Vishal, V.; Sethi, C.; Chandra, D. Impact of Supercritical CO2 on Shale Reservoirs and Its Implication for CO2 Sequestration. Energy Fuels 2022, 36, 9882–9903. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Luo, G.; Achang, M.; Cains, J.; Wethington, C.; Katende, A.; Grammer, G.M.; Puckette, J.; Pashin, J.; Castagna, M.; et al. Multiscale Characterization of the Caney Shale — An Emerging Play in Oklahoma. Midcontinent Geoscience 2021, 2, 33–53. [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Chen, S.; Wang, M.; Yu, Z.; Wang, H. Progress and Prospects of Supercritical CO2 Application in the Exploitation of Shale Gas Reservoirs. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 18370–18384. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, F.; Kang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Liu, Y. SC-CO2 and Brine Exposure Altering the Mineralogy, Microstructure, and Micro- and Macromechanical Properties of Shale. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 11064–11077. [CrossRef]

- Tapriyal, D.; Haeri, F.; Crandall, D.; Horn, W.; Lun, L.; Lee, A.; Goodman, A. Caprock Remains Water Wet Under Geologic CO2 Storage Conditions. Geophysical Research Letters 2024, 51, e2024GL109123. [CrossRef]

- Katende, A.; Awejori, G.; Benge, M.; Nakagawa, S.; Wang, Y.; Xiong, F.; Puckette, J.; Grammer, M.; Rutqvist, J.; Doughty, C.; et al. Multidimensional, Experimental and Modeling Evaluation of Permeability Evolution, the Caney Shale Field Lab, OK, USA. In Unconventional Resources Technology Conference, 13?15 June 2023; SEG Global Meeting Abstracts; Unconventional Resources Technology Conference (URTeC), 2023; pp. 1505–1526.

- Sori, A.; Moghaddas, J.; Abedpour, H. Comprehensive Review of Experimental Studies, Numerical Modeling, Leakage Risk Assessment, Monitoring, and Control in Geological Storage of Carbon Dioxide: Implications for Effective CO2 Deployment Strategies. Greenhouse Gases: Science and Technology 2024, 14, 887–913. [CrossRef]

- Ehlig-Economides, C.A. Geologic Carbon Dioxide Sequestration Methods, Opportunities, and Impacts. Current Opinion in Chemical Engineering 2023, 42, 100957. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zou, R.; Zou, R.; Huang, L.; Liu, Y.; Meng, Z.; Wang, Z.; Lei, H. A Systematic Review of CO2 Injection for Enhanced Oil Recovery and Carbon Storage in Shale Reservoirs. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 37134–37165. [CrossRef]

- Fitts, J.P.; Peters, C.A. Caprock Fracture Dissolution and CO2 Leakage. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry 2013, 77, 459–479. [CrossRef]

- Olabode, A.; Radonjic, M. Shale Caprock/Acidic Brine Interaction in Underground CO2 Storage. Journal of Energy Resources Technology 2014, 136. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Tian, S.; Xian, X.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, K.; Liu, J. Comprehensive Review of Property Alterations Induced by CO2–Shale Interaction: Implications for CO2 Sequestration in Shale. Energy Fuels 2022, 36, 8066–8080. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.T.; Jahediesfanjani, H. Estimating the Pressure-Limited Dynamic Capacity and Costs of Basin-Scale CO2 Storage in a Saline Formation. International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control 2019, 88, 156–167. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Sun, M.; Sun, X.; Liu, B.; Ostadhassan, M.; Huang, W.; Chen, X.; Pan, Z. Pore Network Characterization of Shale Reservoirs through State-of-the-Art X-Ray Computed Tomography: A Review. Gas Science and Engineering 2023, 113, 204967. [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Xie, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Wang, C.; Li, T.; Zhu, X.; Luo, K.; Cao, J.; Li, N. A Minireview of the Influence of CO2 Injection on the Pore Structure of Reservoir Rocks: Advances and Outlook. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 118–135. [CrossRef]

- Fentaw, J.W.; Emadi, H.; Hussain, A.; Fernandez, D.M.; Thiyagarajan, S.R. Geochemistry in Geological CO2 Sequestration: A Comprehensive Review. Energies 2024, 17, 5000. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, K.; Shan, X.; Taylor, K.G.; Ma, L. Potential for CO2 Storage in Shale Basins in China. International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control 2024, 132, 104060. [CrossRef]

- Shukla, R.; Ranjith, P.; Haque, A.; Choi, X. A Review of Studies on CO2 Sequestration and Caprock Integrity. Fuel 2010, 89, 2651–2664. [CrossRef]

- Leng, J.; Bump, A.; Hosseini, S.A.; Meckel, T.A.; Wang, Z.; Wang, H. A Comprehensive Review of Efficient Capacity Estimation for Large-Scale CO2 Geological Storage. Gas Science and Engineering 2024, 126, 205339. [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; Gong, H.; Sang, Q.; Zhao, X.; Zhu, C. Review of CO2-Kerogen Interaction and Its Effects on Enhanced Oil Recovery and Carbon Sequestration in Shale Oil Reservoirs. Resources Chemicals and Materials 2022, 1, 93–113. [CrossRef]

- Kelemen, P.; Benson, S.M.; Pilorgé, H.; Psarras, P.; Wilcox, J. An Overview of the Status and Challenges of CO2 Storage in Minerals and Geological Formations. Front. Clim. 2019, 1. [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, K.C.; Dje, L.B.; Achang, M.; Radonjic, M. Comparative Laboratory Study of the Geochemical Reactivity of the Marcellus Shale: Rock–Fluid Interaction of Drilled Core Samples vs. Outcrop Specimens. Water 2023, 15, 1940. [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Lin, S.; Yang, C.; Wang, K.; Liu, S.; Guo, Y. A Critical Review of ScCO2-Enhanced Gas Recovery and Geologic Storage in Shale Reservoirs. Gas Science and Engineering 2024, 125, 205317. [CrossRef]

- Awejori, G.A.; Dong, W.; Doughty, C.; Spycher, N.; Radonjic, M. Mineral and Fluid Transformation of Hydraulically Fractured Shale: Case Study of Caney Shale in Southern Oklahoma. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-energ. Geo-resour. 2024, 10, 128. [CrossRef]

- Adua Awejori, G.; Doughty, C.; Xiong, F.; Paronish, T.; Spycher, N.; Radonjic, M. Integrated Experimental and Modeling Study of Geochemical Reactions of Simple Fracturing Fluids with Caney Shale. Energy Fuels 2022, 36, 10064–10081. [CrossRef]

- Goodman, A.; Fukai, I.; Dilmore, R.; Frailey, S.; Bromhal, G.; Soeder, D.; Gorecki, C.; Peck, W.; Rodosta, T.; Guthrie, G. Methodology for Assessing CO2 Storage Potential of Organic-Rich Shale Formations. Energy Procedia 2014, 63, 5178–5184. [CrossRef]

- Fatah, A.; Bennour, Z.; Ben Mahmud, H.; Gholami, R.; Hossain, M.M. A Review on the Influence of CO2/Shale Interaction on Shale Properties: Implications of CCS in Shales. Energies 2020, 13, 3200. [CrossRef]

- Knauss, K.G.; Johnson, J.W.; Steefel, C.I. Evaluation of the Impact of CO2, Co-Contaminant Gas, Aqueous Fluid and Reservoir Rock Interactions on the Geologic Sequestration of CO2. Chemical Geology 2005, 217, 339–350. [CrossRef]

- Peter, A.; Yang, D.; Eshiet, K.I.-I.I.; Sheng, Y. A Review of the Studies on CO2–Brine–Rock Interaction in Geological Storage Process. Geosciences 2022, 12, 168. [CrossRef]

- Sanguinito, S.; Goodman, A.; Tkach, M.; Kutchko, B.; Culp, J.; Natesakhawat, S.; Fazio, J.; Fukai, I.; Crandall, D. Quantifying Dry Supercritical CO2-Induced Changes of the Utica Shale. Fuel 2018, 226, 54–64. [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhang, S.; Xing, H.; Zou, Y. CO2–Brine–Rock Interactions Altering the Mineralogical, Physical, and Mechanical Properties of Carbonate-Rich Shale Oil Reservoirs. Energy 2022, 256, 124608. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Sang, S.; Niu, Q.; Zhang, K.; Liu, F.; Wang, W.; Chang, J. Changes of Multiscale Surface Morphology and Pore Structure of Mudstone Associated with Supercritical CO2 -Water Exposure at Different Times. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 4212–4223. [CrossRef]

- Choo, T.K.; Etschmann, B.; Selomulya, C.; Zhang, L. Behavior of Fe2+/3+ Cation and Its Interference with the Precipitation of Mg2+ Cation upon Mineral Carbonation of Yallourn Fly Ash Leachate under Ambient Conditions. Energy Fuels 2016, 30, 3269–3280. [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, A.R.; MacDonald, J.; Neill, I. Mechanisms of Secondary Carbonate Precipitation on Felsic, Intermediate, and Mafic Igneous Rocks: A Case Study for NW Scotland 2024.

- Olabode, A.; Radonjic, M. Geochemical Markers in Shale-CO2 Experiment at Core Scale. Energy Procedia 2017, 114, 3840–3854. [CrossRef]

- Dje, L.B.; Awejori, G.A.; Radonjic, M. Comparison of Geochemical Reactivity of Marcellus and Caney Shale Based on Effluent Analysis. In Proceedings of the 58th U.S. Rock Mechanics/Geomechanics Symposium; ARMA: Golden, Colorado, USA, June 23 2024; p. D041S053R004.

- Ghosh, S.; Adsul, T.; Varma, A.K. Organic Matter and Mineralogical Acumens in CO2 Sequestration. In Green Sustainable Process for Chemical and Environmental Engineering and Science; Inamuddin, Dr., Altalhi, T., Eds.; Elsevier, 2023; pp. 561–594 ISBN 978-0-323-99429-3.

- Zhou, Q.; Liu, J.; Ma, B.; Li, C.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, G.; Lyu, C. Pyrite Characteristics in Lacustrine Shale and Implications for Organic Matter Enrichment and Shale Oil: A Case Study from the Triassic Yanchang Formation in the Ordos Basin, NW China. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 16519–16535. [CrossRef]

- Katende, A.; Rutqvist, J.; Benge, M.; Seyedolali, A.; Bunger, A.; Puckette, J.O.; Rhin, A.; Radonjic, M. Convergence of Micro-Geochemistry and Micro-Geomechanics towards Understanding Proppant Shale Rock Interaction: A Caney Shale Case Study in Southern Oklahoma, USA. Journal of Natural Gas Science and Engineering 2021, 96, 104296. [CrossRef]

| Author(s) | Focus | Research Gaps |

|---|---|---|

| [9,10,11] | Numerical Simulations of CO2 in Geological Settings | Limited empirical data on physicochemical interactions at the mineralogical level in shales. Need for experimental validation of simulated predictions and theoretical models. |

| [12,13] | Geologic Carbon Sequestration Review |

High costs and energy requirements for CO2 capture; need for cost reduction and efficiency enhancement. |

| [5,14,15] | Caprock Integrity and Fracture Dynamics |

Need for long-term studies to understand the evolution of fissures under continuous CO2 flow. Importance of considering hydrological factors in geological stability assessments. |

| [2,16,17,18,19] | Pore Structure Alterations |

Microscale and nanoscale analysis, shale-specific studies, and controlled experiments are vital to assess structural changes and ensure long-term CO2 storage integrity. |

| [5,7,20] | Subcritical and Supercritical CO2 Effects on Shale |

Robust simulations and further studies are essential to understand shale sensitivity to CO2 under varying conditions and optimize EOR strategies. |

| [13,21,22,23,24,25] | CO2 Storage Capacity and Monitoring |

Targeted modeling, localized studies, and field validation are essential to predict CO2–shale interactions, refine capacity estimates, and assess long-term storage risks. |

| [5,9,19,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34] | Impact of CO2 - Rock Interactions |

Comprehensive experimental and modeling studies are needed to understand shale reactivity, nanoconfinement, water-chemistry interactions, and long-term CO2 impacts across diverse geological settings. |

| Mineral Phase | Chemical Formula | Rationale in CCUS | Occurrence in Shales | Relevance to CCUS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcite | CaCO3 | Forms during CO2 sequestration via reaction with calcium-bearing minerals. | Common carbonate mineral in shales. | Relevant due to carbonate precipitation under CO2-rich conditions. |

| Dolomite | CaMg(CO3)2 | Forms from interactions of CO2 with calcium and magnesium-rich minerals. | Present in some shale formations; associated with carbonate deposits. | Plays a role in carbonate mineralization under CO2 sequestration. |

| Magnesite | MgCO3 | Forms when CO2 reacts with magnesium-bearing minerals. | Rare in shales, mainly found in magnesium-rich environments. | Forms stable carbonate phases during CO2 sequestration. |

| Siderite | FeCO3 | Iron carbonate that forms in CO2-rich environments. | Occasionally found in Fe-rich shales, but more common in sedimentary rocks. | Can store CO2 in carbonate form but limited occurrence in shales. |

| Quartz | SiO2 | Stable silicate mineral in shales, largely unreactive to CO2. | Common silicate mineral in shales, a major constituent of sandstones. | Mechanically stable but chemically inert under CO2 exposure. |

| Illite | (K,H3O)(Al,Mg,Fe)2(Si,Al)4O₁₀ [(OH)2 | Clay mineral influencing shale porosity and permeability under CO2 exposure. | Frequent in shales as a clay mineral affecting permeability. | Affects shale permeability and reactivity with CO2. |

| Montmorillonite | (Na,Ca)₀.3(Al,Mg)2Si4O₁₀(OH)2·nH2O | Swelling clay mineral that absorbs CO2, altering shale properties. | Found in clay-rich shales, particularly those with high swelling potential. | Modifies pore structure and water retention upon CO2 exposure. |

| Kaolinite | Al2Si2O₅(OH)4 | Clay mineral with minor interactions with CO2. | Occurs in some shales but not a dominant mineral. | Minor role in CO2 reactivity, mainly affects shale composition. |

| Ankerite | Ca(Fe2+,Mg,Mn)(CO3)2 | Iron and magnesium carbonate forming under CO2 sequestration conditions. | Found in iron-rich sedimentary formations, including some shales. | Potentially relevant for mineral trapping of CO2. |

| Chlorite | (Mg,Fe2+,Fe³+,Al)6(Si,Al)4O₁₀(OH)₈ | Clay mineral influencing CO2-induced alterations in shales. | Occurs in some shales, affecting fluid interactions. | Affects CO2-rock interactions by modifying clay stability. |

| Pyrite | FeS2 | Common sulfide in shales, oxidizing under CO2 influence. | Common in organic-rich shales, particularly those with high sulfur content. | Oxidation influences acid generation, affecting mineral trapping. |

| Feldspar | KAlSi3O₈ – NaAlSi3O₈ – CaAl2Si2O₈ | Silicate mineral that weathers in CO2 environments. | Common framework silicate mineral in various shales. | Minor role in CO2 sequestration; undergoes limited chemical change. |

| Hematite | Fe2O3 | Iron oxide that forms from pyrite oxidation during CO2 sequestration. | Minor iron oxide phase in shales formed from oxidation processes. | May form secondary precipitates upon CO2 exposure. |

| Anhydrite | CaSO4 | Sulfate mineral present in caprocks affecting CO2 storage integrity. | Common in evaporite-bearing shales and caprocks. | Contributes to caprock integrity in sequestration sites. |

| Gypsum | CaSO4·2H2O | Hydrated sulfate mineral influenced by CO2-rich fluids. | Hydrated form of anhydrite, often found in caprocks overlying shales. | Influences CO2 migration in formations containing gypsum. |

| Halite | NaCl | Salt mineral forming low-permeability barriers in caprocks. | Evaporite mineral occasionally present in shale formations. | Enhances caprock sealing potential, reducing CO2 leakage. |

| Serpentine | (Mg,Fe)3Si2O₅(OH)4 | Silicate mineral reacting with CO2 to form magnesite. | Occurs in some altered shales with high magnesium content. | Can interact with CO2 under specific geochemical conditions. |

| Olivine | (Mg,Fe)2SiO4 | Silicate mineral reacting with CO2 to facilitate mineral sequestration. | Found in ultramafic environments but rare in shales. | Minor direct role in CO2 sequestration in shales. |

| Plagioclase | (Na,Ca)(Si,Al)4O₈ | Silicate feldspar undergoing carbonation reactions with CO2. | Common in feldspar-rich shales and sandstones. | Participates in feldspar weathering reactions under CO2 influence. |

| Smectite | (Ca,Na)₀.33(Al,Mg)2(Si4O₁₀)(OH)2·nH2O | Clay group mineral swells upon CO2 exposure, modifying rock properties. | Occurs in clay-rich shale formations, affecting fluid movement. | Clay swelling may alter CO2 migration pathways. |

| Brucite | Mg(OH)2 | Magnesium hydroxide that reacts with CO2 forming magnesite. | Rare in shales but found in magnesium-rich alteration zones. | Relevant in carbonation processes for CO2 trapping. |

| Forsterite | Mg2SiO4 | High-Mg silicate reacting with CO2 for mineral sequestration. | More common in ultramafic formations, rare in shales. | Limited relevance in shales; reacts with CO2 in ultramafic rocks. |

| Talc | Mg3Si4O₁₀(OH)2 | Magnesium silicate that alters during CO2 interactions. | Occurs in talc-carbonate altered zones; uncommon in shales. | Plays minor role in mineral transformations in CO2 storage. |

| Mariposite | Cr-muscovite | Chromium-bearing mica associated with carbonated ultramafic rocks. | Occasionally found in altered metamorphic environments, rare in shales. | Not directly involved in CO2 trapping but alters rock properties. |

| Fuchsite | Cr-muscovite | Green, chromium-bearing mica found in carbonated environments. | Rarely found in shales; more common in metamorphic terrains. | Limited role in CO2 interactions due to mineral stability. |

| Zeolites | Mx/n [(AlO2)x(SiO2)y] · zH2O | Adsorbs CO2, enhancing storage capacity in shales. | Uncommon in natural shale formations but widely used in CO2 capture studies. | Relevant in artificial CO2 capture applications but rare in shales. |

| Muscovite | KAl2(AlSi3O₁₀)(OH)2 | Stable mineral in shales, does not significantly react with CO2 under sequestration conditions. | Common in shales as a mica mineral, contributing to overall mineral composition. | Minimal role in CO2 sequestration due to chemical stability. |

| Jarosite | KFe3(SO4)2(OH)6 | Forms in acidic environments and is not relevant for CO2 sequestration in typical shale formations. | Not common in shales; forms in oxidizing, acidic conditions, often as a sulfide weathering product. | Not relevant for CCUS in shales due to formation constraints. |

| Dawsonite | NaAlCO3(OH)2 | Potential mineral for CO2 trapping in sandstone formations through carbonate precipitation. | Rare; more common in sandstone reservoirs where CO2 mineral trapping occurs. | Relevant in sandstone-hosted sequestration but not typically found in shale settings. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).