Submitted:

04 June 2025

Posted:

05 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Coatings Deposition

2.2. Structural Characterization and Morphology Observation

2.3. Electrochemical Properties Measurement

3. Results and Discussion

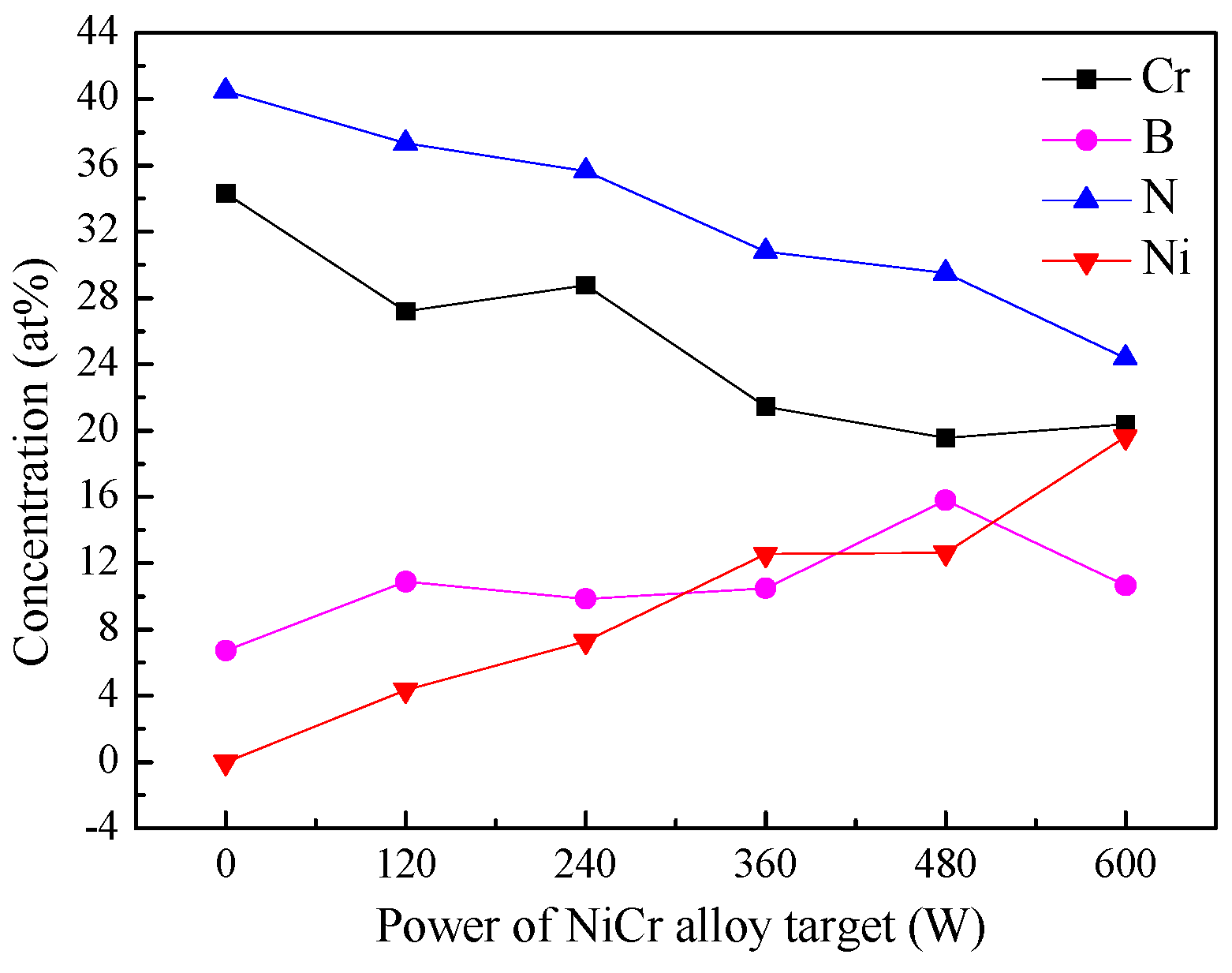

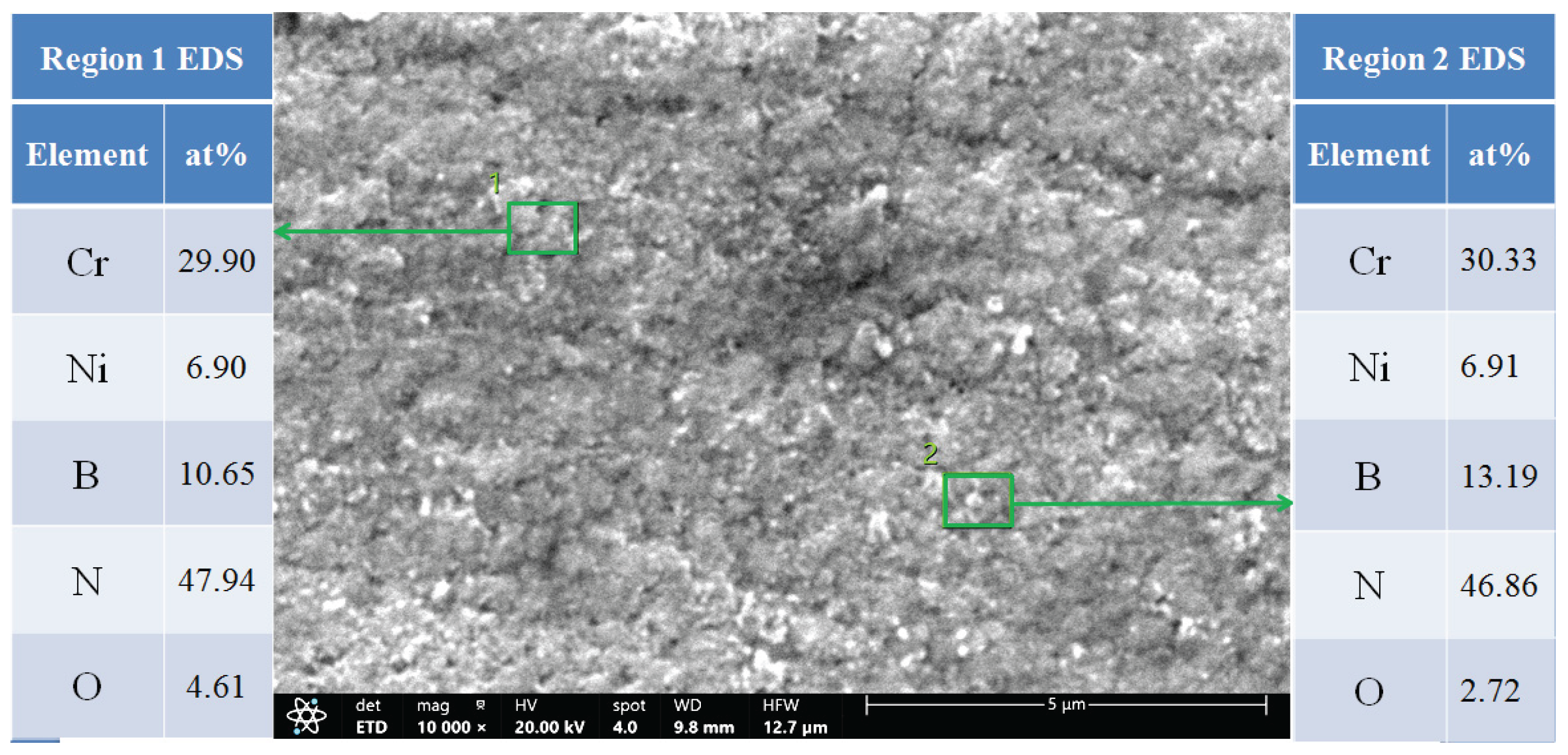

3.1. Microstructure of CrNiBN Coatings

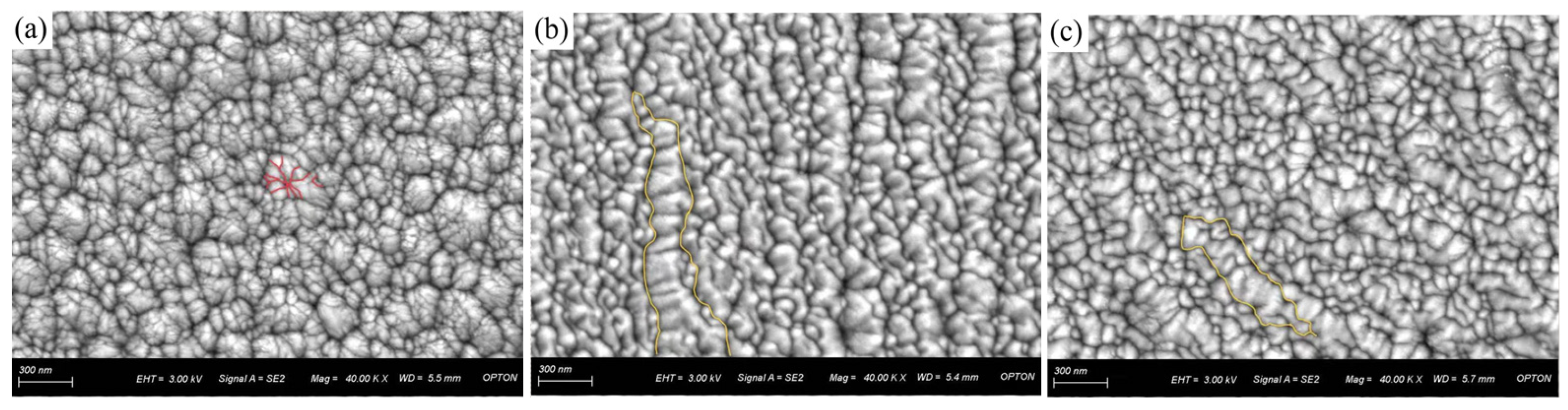

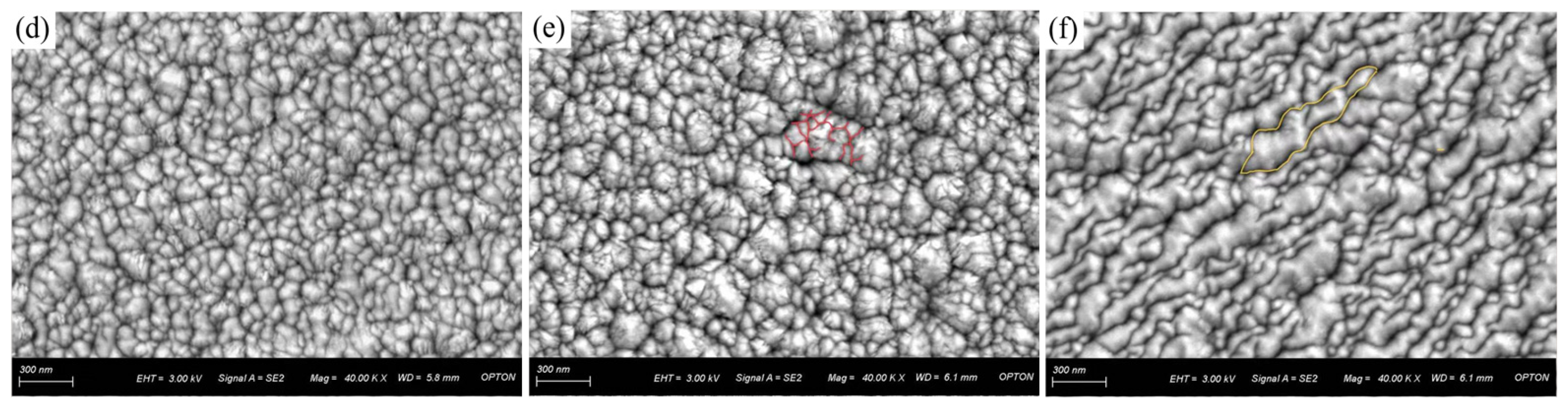

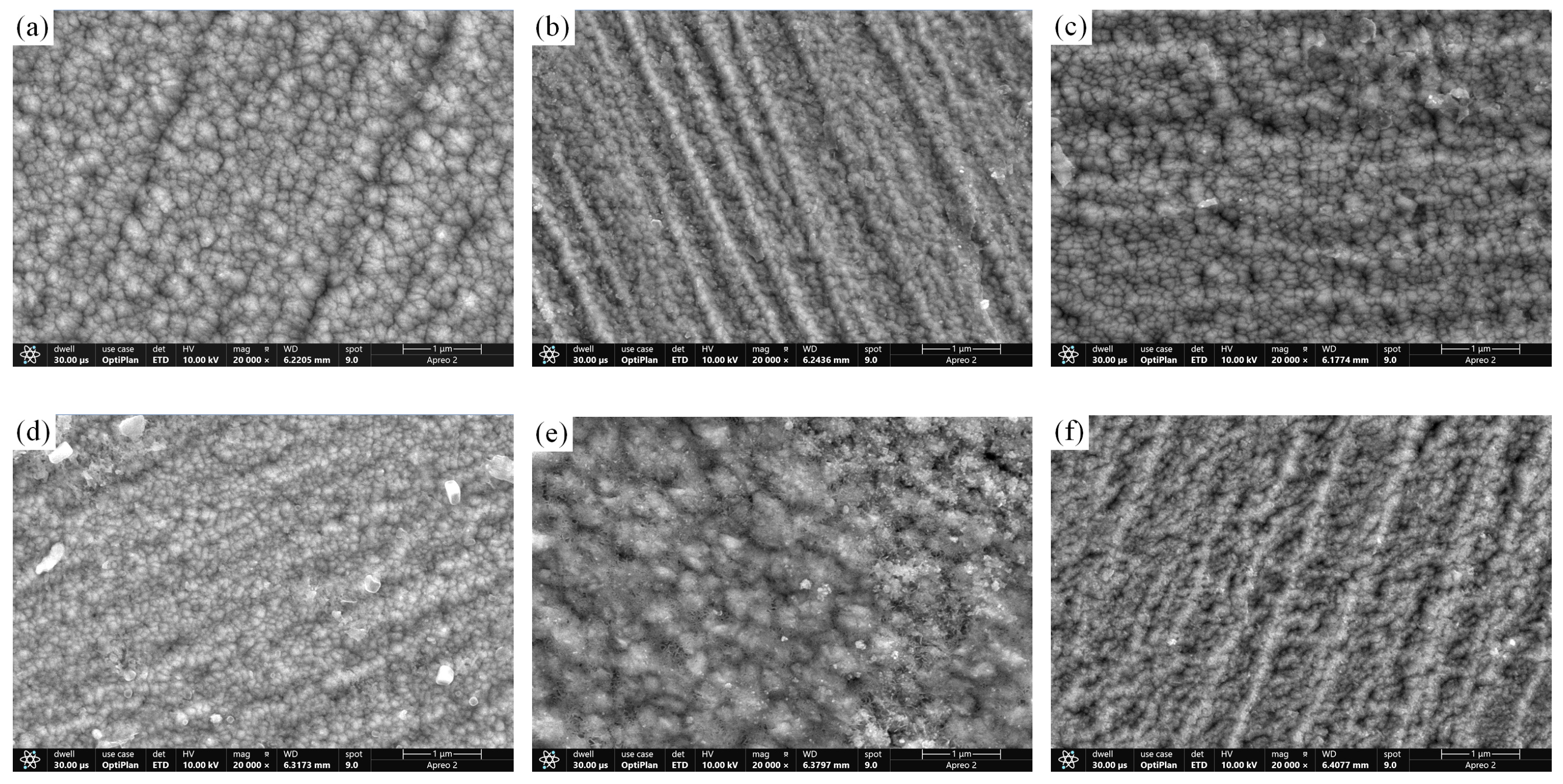

3.2. Surface Morphology and Porosity of CrNiBN Coatings

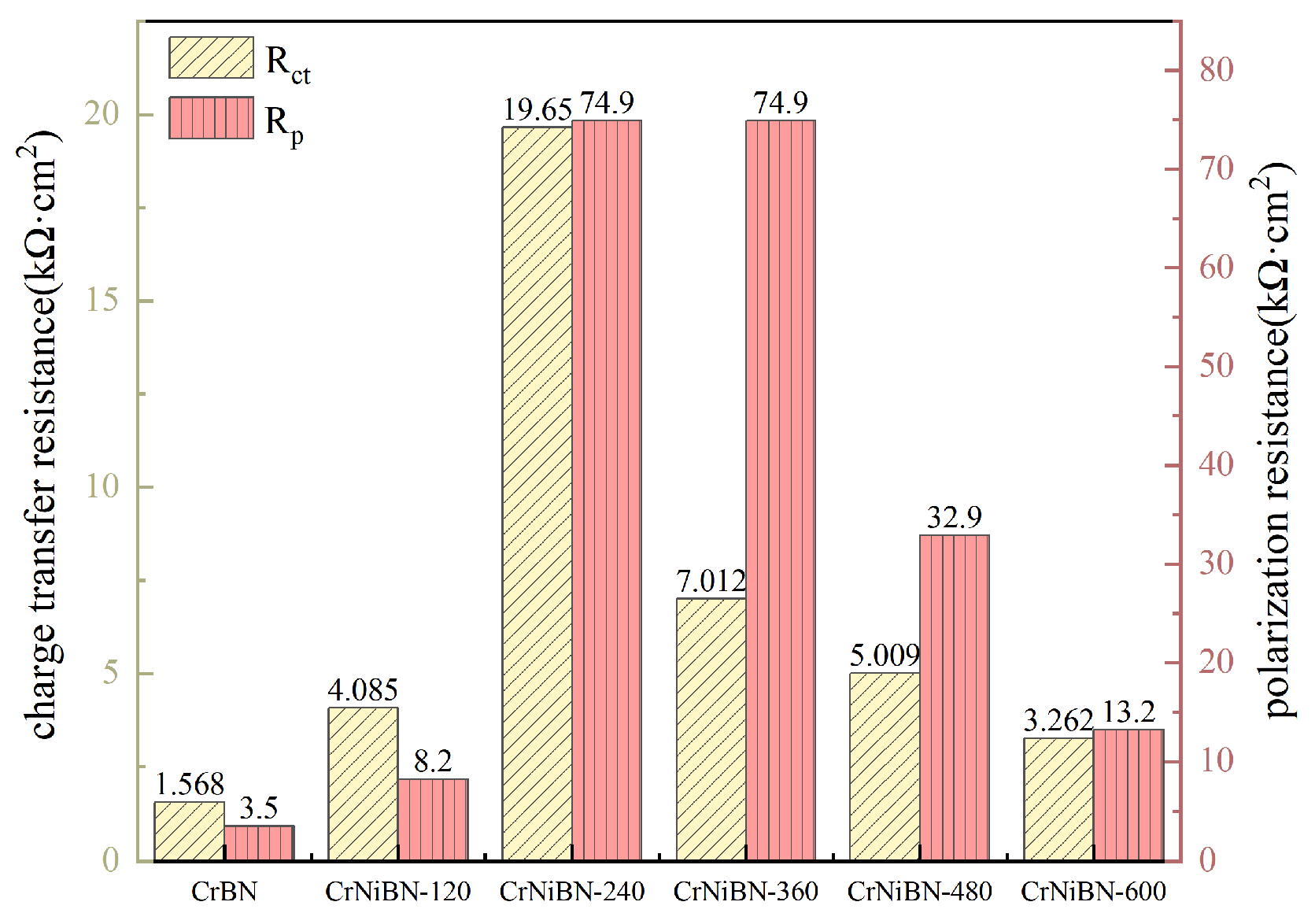

3.3. Electrochemical Properties

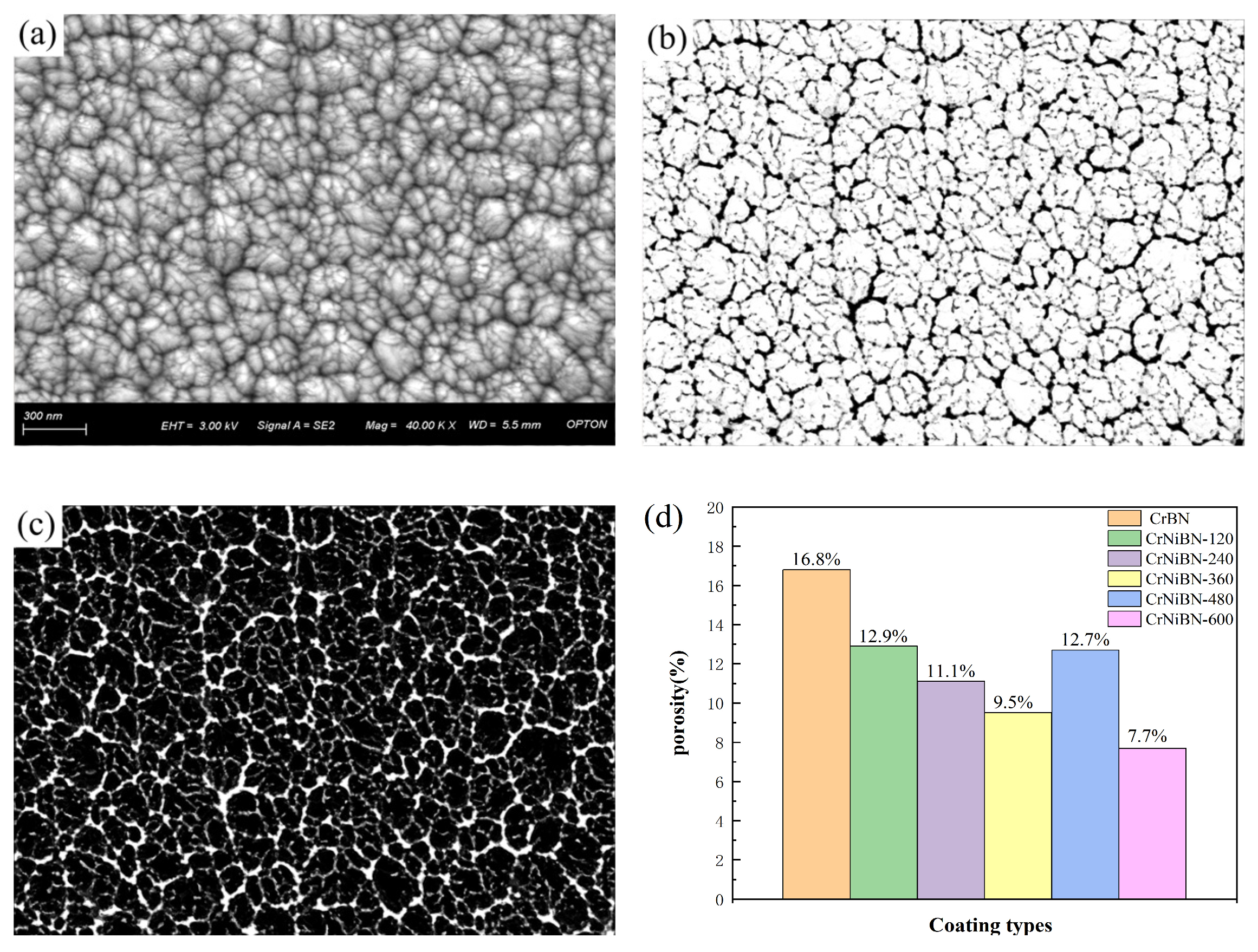

3.3.1. Analysis of Open Circuit Potential Results

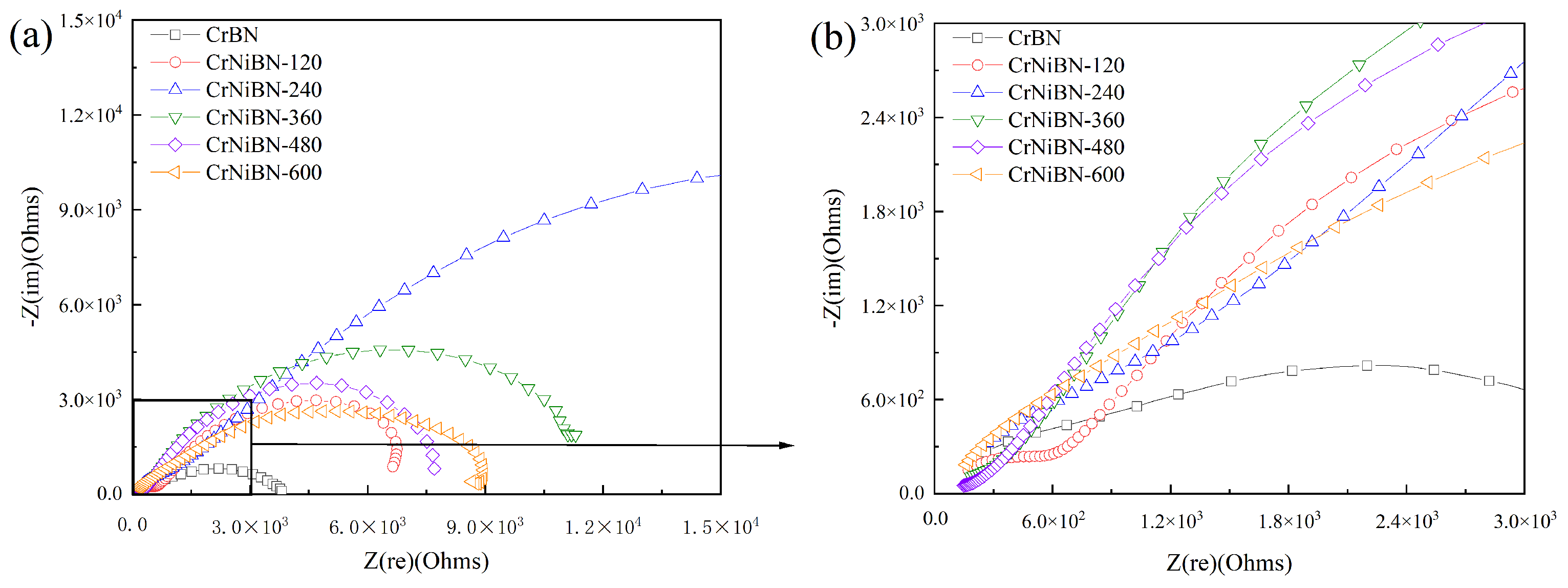

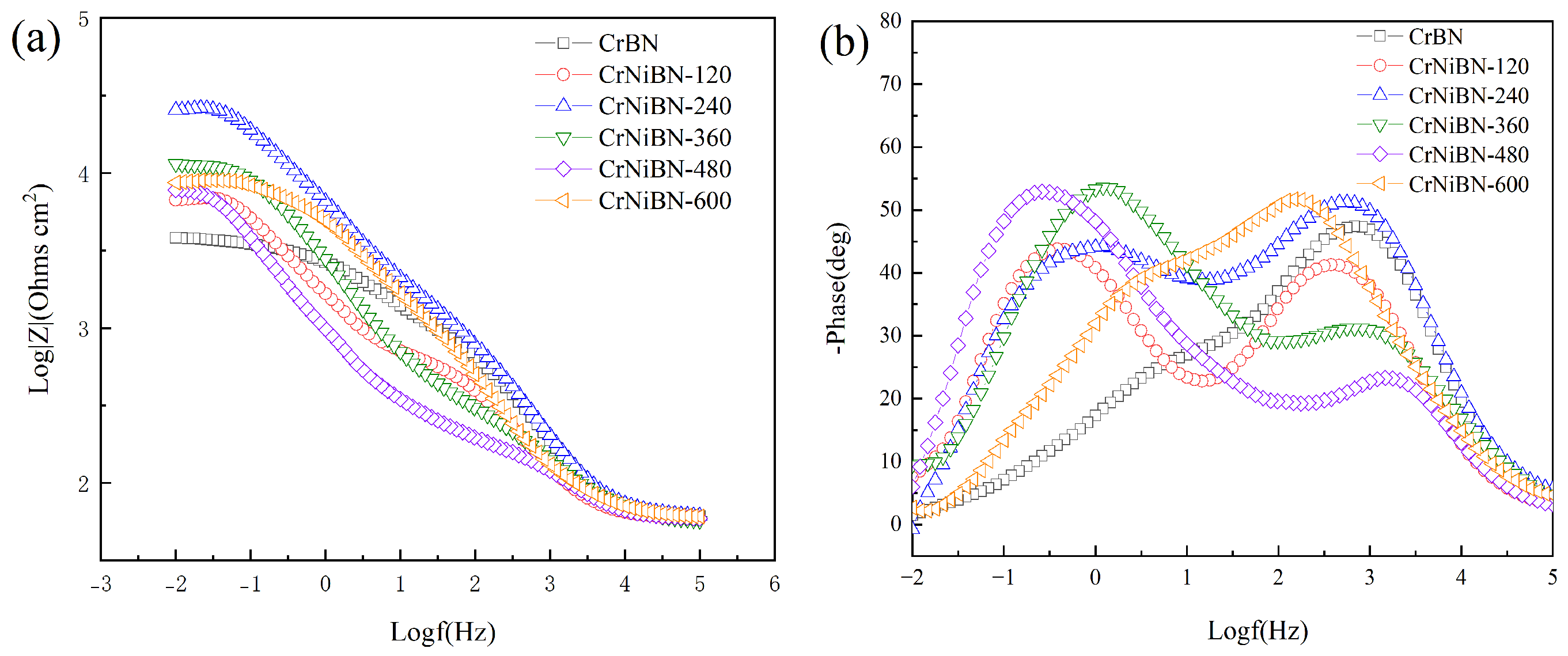

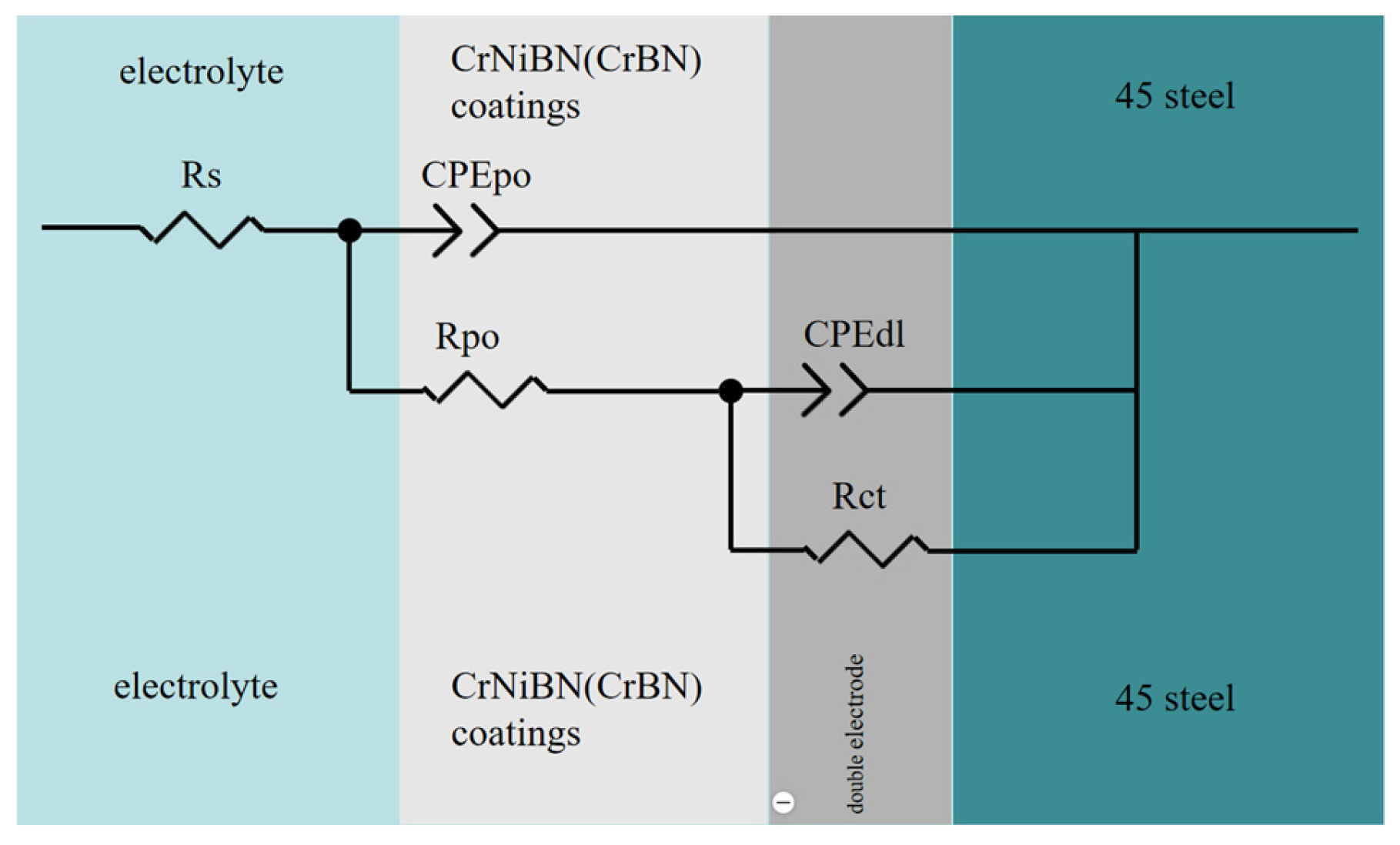

3.3.2. Analysis of Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy Results

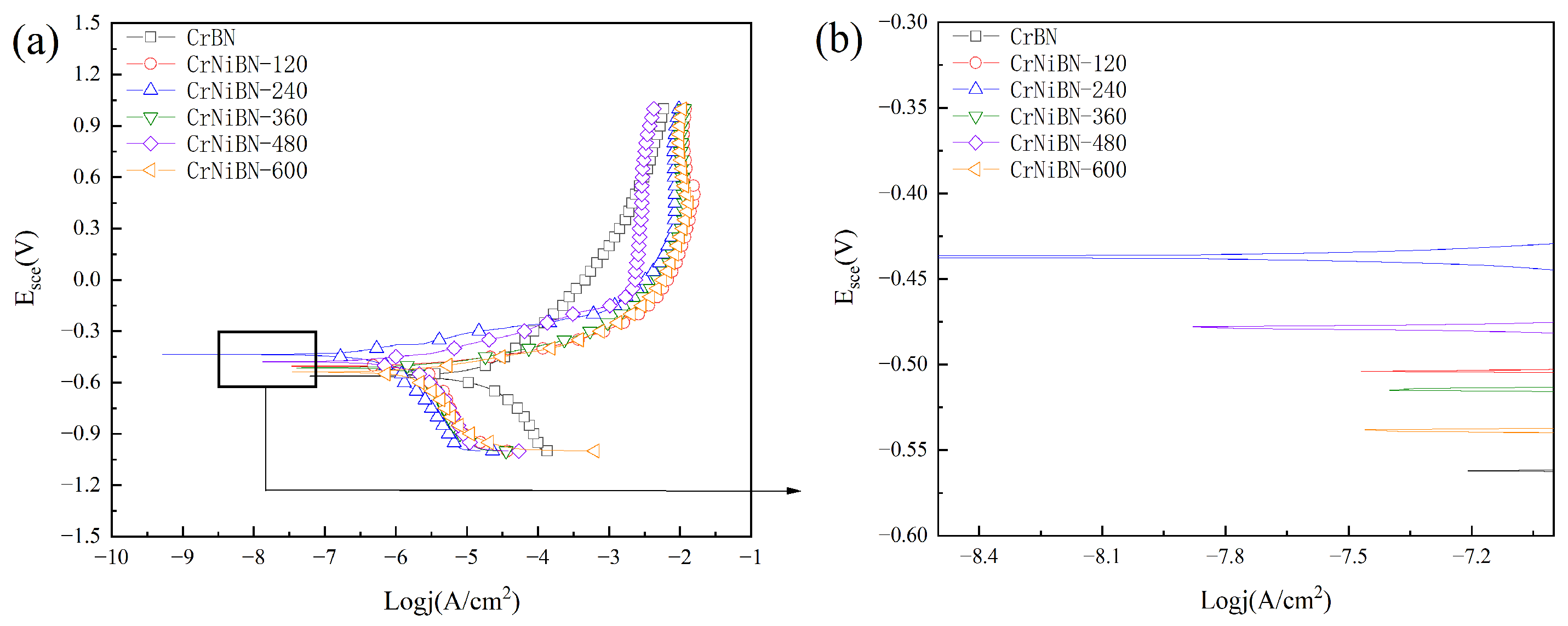

3.3.3. Analysis of Potential-Dynamic Polarization Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscope |

| EIS | Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy |

| PP | Potentio-dynamic Polarization |

| OCP | Open Circuit Potential |

References

- Li, T.; Long, H.; Qiu, C.; Wang, M.; Li, D.; Dong, Z.; Gui, Y. Multi-objective optimization of process parameters of 45 steel laser cladding Ni60PTA alloy powder. Coatings 2022, 12, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Zhang, C.; Li, L.; Yang, Y. Microstructure and properties of CoCrFeNiMnTix high-entropy alloy coated by laser cladding. Coatings 2024, 14, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Li, T.; Shi, H.; Gui, Y.; Qiu, C. Experimental study of laser cladding Ni-based coating based on response surface method. Coatings 2023, 13, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Jiang, D.; Sun, S.; Zhang, B. Microstructure and tribological properties of FeCrCoMnSix high-entropy alloy coatings. Coatings 2024, 14, 1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Ju, H.; Figueiredo, N.; Ferreira, F. Exploring the potential of high-power impulse magnetron sputtering for nitride coatings: Advances in properties and applications. Coatings 2025, 15, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Xie, Y.; Li, F.; Yin, F. Research progress on environmental corrosion resistance of thermal barrier coatings: A review. Coatings 2024, 14, 1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, S.; Shi, Q.; Ge, X.; Wang, W. Multilayer coatings for tribology: A mini review. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maskavizan, A.J.; Quintana, J.P.; Dalibón, E.L.; Márquez, A.B.; Brühl, S.P.; Farina, S.B. Evaluation of wear and corrosion resistance in acidic and chloride solutions of cathodic arc PVD chromium nitride coatings on untreated and plasma nitrided AISI 4140 steel. Surf. Coat. Tech. 2024, 494, 131476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, C.; Zhang, X.; Yin, X.; Meng, F.; Liu, C. The microstructure and wear resistance of laser cladding Ni60/60%WC composite coatings. Metals 2025, 15, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, F.; Zhu, P.; Meng, F.; Xue, Q.; Huang, F. Achieving very low wear rates in binary transition-metal nitrides: The case of magnetron sputtered dense and highly oriented VN coatings. Surf. Coat. Tech. 2014, 248, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Yang, X.; Li, X.; Chai, C.; Liu, W. Study on microstructure and properties of nickel-based self-lubricating coating by laser cladding. Coatings 2022, 12, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, X.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, S. Tribocorrosion of CrN coatings on different steel substrates. Surf. Coat. Tech. 2024, 484, 130829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Pan, Y.; Tang, G.; Liang, D.; Hu, H.; Liu, X.; Liang, Z. Facile fabrication of TiN coatings to enhance the corrosion resistance of stainless steel. Surf. Coat. Tech. 2024, 494, 131450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruden, A.; Restrepo-Parra, E.; Paladines, A.U.; Sequeda, F. Corrosion resistance of CrN thin films produced by dc magnetron sputtering. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2013, 270, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Shu, X.; Liu, E.; Han, Z.; Li, X.; Tang, B. Assessments on corrosion, tribological and impact fatigue performance of Ti- and TiN-coated stainless steels by plasma surface alloying technique. Surf. Coat. Tech. 2014, 239, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Luan, J.; Xie, F.; Zhang, Z.; Evaristo, M.; Cavaleiro, A. The green lubricant coatings deposited by physical vapor deposition for demanding tribological applications: A review. Coatings 2024, 14, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, S. Toward hard yet tough ceramic coatings. Surf. Coat. Tech. 2014, 258, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, K.; Liu, D.; Shao, T. Microstructure and mechanical properties of TiAlSiN nano-composite coatings deposited by ion beam assisted deposition. Sci. China Technol. Sc. 2015, 58, 1682–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, G.; Wood, R.J.K.; Wang, S.C.; Xue, Q. Fabrication of CrAlN nanocomposite films with high hardness and excellent anti-wear performance for gear application. Surf. Coat. Tech. 2010, 204, 3517–3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, E.; Sanjinés, R.; Karimi, A.; Esteve, J.; Levy, F. Mechanical properties of nanocomposite and multilayered Cr-Si-N sputtered thin films. Surf. Coat. Tech. 2004, 180-181, 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Chung, W.; Cho, Y.; Kim, K. Synthesis and mechanical properties of Cr-Si-N coatings deposited by a hybrid system of arc ion plating and sputtering techniques. Surf. Coat. Tech. 2004, 188-189, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Kim, K. Microstructural control of Cr-Si-N films by a hybrid arc ion plating and magnetron sputtering process. Acta Mater. 2009, 57, 4974–4987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, Y.; Hong, J.; Kim, G.; Lee, H.; Han, J. Effect of Si addition to CrN coatings on the corrosion resistance of CrN/stainless steel coating/substrate system in a deaerated 3.5 wt.% NaCl solution. Surf. Coat. Tech. 2007, 201, 9518–9523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Wan, W.; Zhang, X. Effect of Ni doping on the microstructure and toughness of CrAlN coatings deposited by magnetron sputtering. Mater. Res. Express 2020, 7, 026414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Lin, Y.; Zhou, F.; Kong, J. The influence of Ni concentration on the structure, mechanical and tribological properties of Ni-CrSiN coatings in seawater. J Alloy. Compd. 2020, 819, 152998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Lin, Y.; Zhou, F.; Kong, J. Electrochemical properties promotion of CrSiN coatings in seawater via Ni incorporation. J Alloy. Compd. 2021, 856, 157450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Jin, X.; Zhou, F. Comparison of mechanical and tribological properties of CrBN coatings modified by Ni or Cu incorporation. Friction 2022, 10, 516–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, H.; Zhylinski, V.; Vereschaka, A.; Chayeuski, V.; Huo, Y.; Milovich, F.; Sotova, C.; Seleznev, A.; Salychits, O. Comparison of the mechanical properties and corrosion resistance of the Cr-CrN, Ti-TiN, Zr-ZrN, and Mo-MoN coatings. Coatings 2023, 13, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Yao, J.; Dong, H.; Chen, Z.; Liu, X. Enhancing the corrosion resistance of passivation films via the synergistic effects of graphene oxide and epoxy resin. Coatings 2025, 15, 444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandan, C.; Grips, V.; Selvi, V.; Rajam, K. Electrochemical studies of stainless steel implanted with nitrogen and oxygen by plasma immersion ion implantation. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2007, 201, 7873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhou, F.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, C.; Zhang, W.; Li, L.; Lee, S. Effect of titanium or chromium content on the electrochemical properties of amorphous carbon coatings in simulated body fluid. Electrochim. Acta 2013, 112, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, J.; Cai, W. Effect of bias voltage on the structure and electrochemical corrosion behaviour of hydrogenated amorphous carbon(a-C:H)films on NiTi alloys. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2007, 201, 6906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, R.; Ma, S.; Chu, P. Corrosion behaviour of titanium alloy in the presence of serum proteins. Diamond Relat.Mater. 2010, 19, 1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, A.; Liu, E.; Zhang, S.; Tan, S.; Hing, P.; Annergren, I.; Gao, J. Impedance study on electrochemical characteristic of sputtered DLC films. Thin Solid Films 2003, 426, 258–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawiec, H.; Vignal, V.; Schwarzenboeck, E.; Banas, J. Role of plastic deformation and microstructure in the micro-electrochemical behaviour of Ti-6Al-4V in sodium chloride solution. Electrochim. Acta 2013, 104, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Alfantazi, A. Effect of microstructure and temperature on electrochemical behavior of niobium in phosphate-buffered saline solutions. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2013, 160, C1–C11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Coatings |

Rs (Ω·cm2) |

(CPE-Y0)po (F/cm2) |

(CPE-n)po |

Rpo (Ω·cm2) |

(CPE-Y0)dl (F/cm2) |

(CPE-n)dl |

Rct (Ω·cm2) |

| CrBN | 29.75 | 8.691×10−6 | 0.8252 | 3.620×102 | 1.786×10−4 | 0.5544 | 1.568×103 |

| CrNiBN-120 | 27.97 | 4.119×10−5 | 0.7213 | 2.844×102 | 4.647×10−4 | 0.7253 | 4.085×103 |

| CrNiBN-240 | 29.79 | 1.074×10−5 | 0.7944 | 6.779×102 | 9.100×10−5 | 0.6128 | 1.965×104 |

| CrNiBN-360 | 26.90 | 5.624×10−5 | 0.6564 | 2.064×102 | 1.292×10−4 | 0.7641 | 7.012×103 |

| CrNiBN-480 | 27.62 | 8.501×10−5 | 0.6390 | 1.078×102 | 5.046×10−4 | 0.7396 | 5.009×103 |

| CrNiBN-600 | 29.90 | 4.026×10−5 | 0.7127 | 1.390×103 | 7.644×10−5 | 0.7149 | 3.262×103 |

| Coatings | Ecorr(Evs.SCE) | Icorr(nA/cm2) | βa(V) | βc(V) | Rp(kΩ·cm2) |

| CrBN | -0.5627 | 12490 | 0.197 | 0.208 | 3.5 |

| CrNiBN-120 | -0.5047 | 2898 | 0.059 | 0.755 | 8.2 |

| CrNiBN-240 | -0.4379 | 410.5 | 0.101 | 0.237 | 74.9 |

| CrNiBN-360 | -0.4369 | 456.2 | 0.101 | 0.356 | 74.9 |

| CrNiBN-480 | -0.4760 | 1020 | 0.102 | 0.317 | 32.9 |

| CrNiBN-600 | -0.5411 | 1839 | 0.069 | 0.29 | 13.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).