Submitted:

03 June 2025

Posted:

04 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

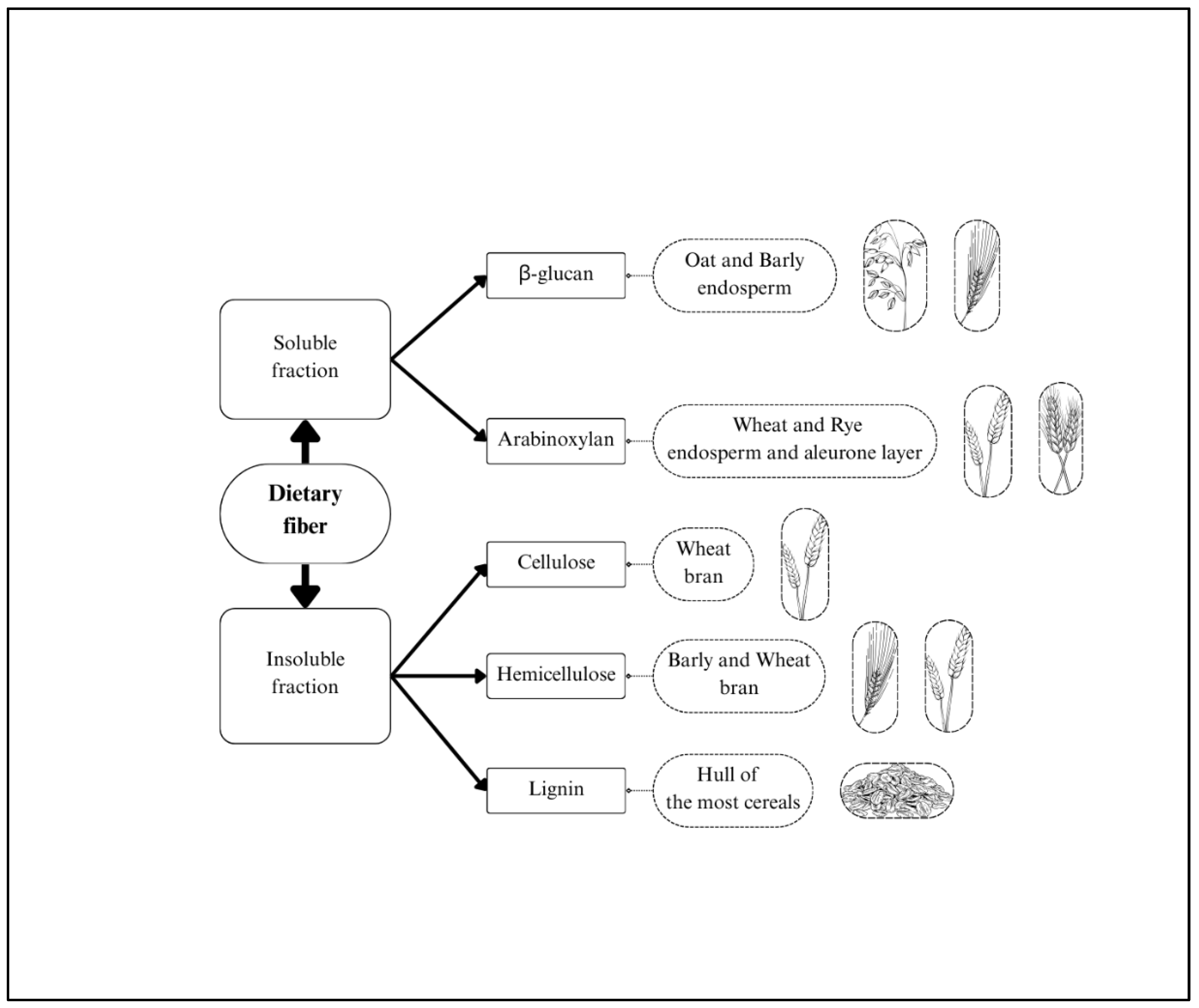

2. Dietary Fiber in Whole Grains

2.1. Structure of Whole Grains

2.2. Dietary Fiber Composition of Selected Whole Grains

3. Physicochemical Properties of Dietary Fiber

3.1. Solubility

3.2. Water-Holding Capacity (WHC)

3.3. Oil Holding Capacity (OHC)

3.4. Viscosity and Gel Formation

3.5. Bile Acid Binding Capacity

3.6. Swelling Ability

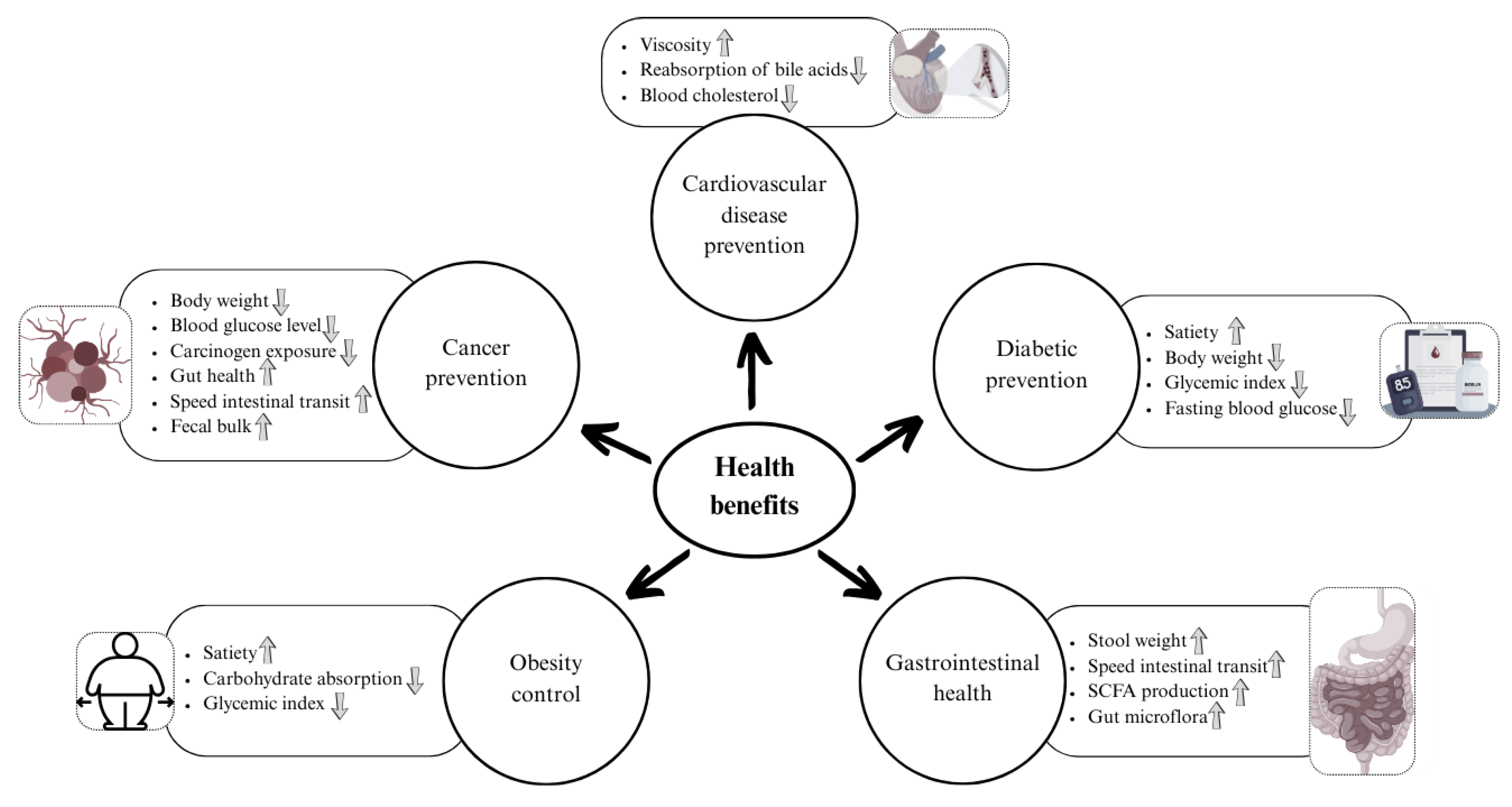

4. Health Benefits of Whole Grain Dietary Fiber

4.1. Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease

4.2. Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

4.3. Control of Obesity

4.4. Gastrointestinal Health

4.5. Prevention of Cancers

| Dietary fiber source | Study type | Health benefit | Research findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rye | Human intervention | Cardiovascular disease prevention | Total and LDL cholesterols were lowered (-0.06 and -0.09 mmol/L, respectively; P < 0.05) after consumption of whole grain rye with lignan supplements after 4 weeks. | [107] |

| Diabetic control | Rye kernel bread decreased blood glucose (0-120 min, P = 0.001), serum insulin response (0-120 minutes, P<0.05), and fasting FFA concentrations (P<0.05). | [108] | ||

| Rye-based foods decreased postprandial glucose- and insulin responses. | [109] | |||

| Obesity control | Participants who consumed a rye-based diet for the 12-week period had lost 1.08 kg body weight and 0.54% body fat more than the refined wheat consumed group (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.36; 1.80, p < 0.01 and 0.05; 1.03, p = 0.03, respectively). | [110] | ||

| Gastrointestinal health | Induced some changes in gut microbiota composition, including increased abundance of the butyrate-producing Agathobacter. | [111] | ||

| Oat | Human intervention | Cardiovascular disease prevention | Significant reduction in office systolic blood pressure (oSBP; P < 0.001) and office diastolic blood pressure (oDBP; P < 0.028) in the oat bran consumed group (30 g/day of oat bran contains 8.9 g of dietary fiber) compared to the control group after 3-month period. | [58] |

| Consumption of oat dietary fiber reduces levels of systemic chronic inflammation after two weeks post-treatment. | [112] | |||

| Diabetic control | The intake of 5 g of oat β-glucan-enriched diet for 12 weeks can help improve glycemic control, increase the feeling of satiety, and promote changes in the gut microbiota profile. | [113] | ||

| The study demonstrated that a hypocaloric oat-based nutrition diet led to a significant reduction in total insulin dosage and HbA1c levels in insulin-treated outpatients with type 2 diabetes. | [114] | |||

| Obesity control | Oat β-glucan intervention increases the abundance of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium. These microbiota alterations contributed to an increase in 7-ketodeoxycholic acid and it enhances bile acid synthesis. | [115] | ||

| Ageing control | A decrease in the Eotaxin-1 protein, an aging-related chemokine, independent of a person’s gender, body mass index, or age. | [112] | ||

| Wheat | Human intervention | Cardiovascular disease prevention | Total and LDL cholesterol were lowered by -0.09 mmol/L at (P < 0.05) after consumption of a wheat-based diet in 40 men with a metabolic syndrome risk profile after 4 weeks. | [107] |

| Obesity control | The study found that consumption of resistant starch-enriched wheat rolls significantly increased fasting and peak concentrations of peptide YY3-36 (PYY3-36), a hormone associated with satiety while decreasing peak concentrations and iAUC of glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide (GIP), which is involved in hunger regulation. | [116] | ||

| Gastrointestinal health | The study has found that intake of 15 g/day of wheat bran extract increases fecal Bifidobacterium and softens stool consistency without major effects on energy metabolism in healthy humans with a slow GI transit. | [117] | ||

| In vivo study | Gastrointestinal health | The study has found that high amylose wheat (HAW) consumption led to an increase in fecal bacterial load and gastrointestinal health in mice. | [118] | |

| Corn | Human intervention | Cardiovascular disease prevention | Whole grain corn flour significantly decreased LDL cholesterols over time (-10.4 ± 3.6 mg/dL, P = 0.005) and marginally decreased total cholesterol (-9.2 ± 3.9 mg/dL, P = 0.072) over time. | [119] |

| Brown rice | Human intervention | Diabetic control | Improved endothelial function, without changes in HbA1c levels | [120] |

| Whole grains | Human intervention | Diabetic control | Higher intake of whole grain fiber was positively associated with better β-cell function, insulin sensitivity, and postprandial glycemic control. | [121] |

| A systematic review found that increasing whole grain fiber intake improves glycemic control and reduces cardiometabolic risk factors in individuals with prediabetes, type 1, or type 2 diabetes. The study suggests increasing daily fiber intake by 15 g or to a total of 35 g per day to lower the risk of premature mortality and enhance diabetes management. | [122] |

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NCDs | Non-Communicable Diseases |

| IDF | Insoluble Dietary Fibers |

| SDF | Soluble Dietary Fibers |

| TDF | Total Dietary Fibe |

| WHC | Water-Holding Capacity |

| OHC | Oil Holding Capacity |

| CA | Cholic Acid |

| CDCA | Chenodeoxycholic Acid |

| LDL-C | Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol |

| CVD | Cardiovascular Disease |

| SCFA | Short-Chain Fatty Acids |

| T2DM | Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus |

| GI | Glycemic Index |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| IBD | Inflammatory Bowel Disease |

References

- Zhang, S.; Xu, X.; Cao, X.; Liu, T. The Structural Characteristics of Dietary Fibers from Tremella Fuciformis and Their Hypolipidemic Effects in Mice. Food Science and Human Wellness 2023, 12, 503–511. [CrossRef]

- P., N.P. V.; Joye, I.J. Dietary Fibre from Whole Grains and Their Benefits on Metabolic Health. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3045. [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Zheng, Y.; Gao, Y.; Xu, W. Dietary Fiber Intake and Gut Microbiota in Human Health. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2507. [CrossRef]

- European Commission Supporting Policy with Scientific Evidence, Whole Grain Intake across European Countries.

- van der Kamp, J.-W.; Jones, J.M.; Miller, K.B.; Ross, A.B.; Seal, C.J.; Tan, B.; Beck, E.J. Consensus, Global Definitions of Whole Grain as a Food Ingredient and of Whole-Grain Foods Presented on Behalf of the Whole Grain Initiative. Nutrients 2021, 14, 138. [CrossRef]

- Khalid, A.; Hameed, A.; Tahir, M.F. Wheat Quality: A Review on Chemical Composition, Nutritional Attributes, Grain Anatomy, Types, Classification, and Function of Seed Storage Proteins in Bread Making Quality. Front Nutr 2023, 10. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Sun, Y.; Fan, M.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Qian, H. Wheat Bran, as the Resource of Dietary Fiber: A Review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2022, 62, 7269–7281. [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhen, X.; Lei, H.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Gou, D.; Zhao, J. Investigating the Physicochemical Characteristics and Importance of Insoluble Dietary Fiber Extracted from Legumes: An in-Depth Study on Its Biological Functions. Food Chem X 2024, 22, 101424. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Wang, L.F.; Bialobzyski, S.; Zijlstra, R.T.; Beltranena, E. Energy and Nutrient Digestibility and Effect of Increasing the Dietary Inclusion of Hull-Less Oats Replacing Wheat Grain on Growth Performance of Weanling Pigs. Anim Feed Sci Technol 2024, 318, 116139. [CrossRef]

- Kang, Z.; Meng, N.; Liu, M.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, P.; Qiao, C.-C.; Tan, B. Enhancement of Physicochemical, in Vitro Hypoglycemic, Hypolipidemic, Antioxidant and Prebiotic Properties of Oat Bran Dietary Fiber: Dynamic High Pressure Microfluidization. Food Biosci 2024, 61, 104983. [CrossRef]

- kaur, S.; Bhardwaj, R.D.; Kapoor, R.; Grewal, S.K. Biochemical Characterization of Oat (Avena Sativa L.) Genotypes with High Nutritional Potential. LWT 2019, 110, 32–39. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.S.; Nadeem, M.; Sultan, M.; Sajjad, U.; Hamid, K.; Qureshi, T.M.; Javaria, S. Techno-Functional Characteristics, Mineral Composition and Antioxidant Potential of Dietary Fiber Extracted by Sonication from Different Oat Cultivars (Avena Sativa). Future Foods 2024, 9, 100349. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Wang, L.F.; Bialobzyski, S.; Zijlstra, R.T.; Beltranena, E. Energy and Nutrient Digestibility and Effect of Increasing the Dietary Inclusion of Hull-Less Oats Replacing Wheat Grain on Growth Performance of Weanling Pigs. Anim Feed Sci Technol 2024, 318, 116139. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.S.; Nadeem, M.; Sultan, M.; Sajjad, U.; Hamid, K.; Qureshi, T.M.; Javaria, S. Techno-Functional Characteristics, Mineral Composition and Antioxidant Potential of Dietary Fiber Extracted by Sonication from Different Oat Cultivars (Avena Sativa). Future Foods 2024, 9, 100349. [CrossRef]

- Boukid, F. Corn (Zea Mays L.) Arabinoxylan to Expand the Portfolio of Dietary Fibers. Food Biosci 2023, 56, 103181. [CrossRef]

- Boukid, F. Comprehensive Review of Barley Dietary Fibers with Emphasis on Arabinoxylans. Bioactive Carbohydrates and Dietary Fibre 2024, 31, 100410. [CrossRef]

- Kozlova, L. V.; Nazipova, A.R.; Gorshkov, O. V.; Gilmullina, L.F.; Sautkina, O. V.; Petrova, N. V.; Trofimova, O.I.; Ponomarev, S.N.; Ponomareva, M.L.; Gorshkova, T.A. Identification of Genes Involved in the Formation of Soluble Dietary Fiber in Winter Rye Grain and Their Expression in Cultivars with Different Viscosities of Wholemeal Water Extract. Crop J 2022, 10, 532–549. [CrossRef]

- Tagliasco, M.; Font, G.; Renzetti, S.; Capuano, E.; Pellegrini, N. Role of Particle Size in Modulating Starch Digestibility and Textural Properties in a Rye Bread Model System. Food Research International 2024, 190, 114565. [CrossRef]

- Pferdmenges, L.E.; Lohmayer, R.; Frommherz, L.; Brühl, L.; Hüsken, A.; Mayer-Miebach, E.; Meinhardt, A.-K.; Ostermeyer, U.; Sciurba, E.; Zentgraf, H.; et al. Overview of the Nutrient Composition of Selected Milling Products from Rye, Spelt and Wheat in Germany. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2025, 140, 107275. [CrossRef]

- Rakha, A.; Saulnier, L.; Åman, P.; Andersson, R. Enzymatic Fingerprinting of Arabinoxylan and β-Glucan in Triticale, Barley and Tritordeum Grains. Carbohydr Polym 2012, 90, 1226–1234. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xu, R.; Qin, S.; Song, Q.; Guo, B.; Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, B. Cereal Dietary Fiber Regulates the Quality of Whole Grain Products: Interaction between Composition, Modification and Processing Adaptability. Int J Biol Macromol 2024, 274, 133223. [CrossRef]

- Tanwar, R.; Panghal, A.; Chaudhary, G.; Kumari, A.; Chhikara, N. Nutritional, Phytochemical and Functional Potential of Sorghum: A Review. Food Chemistry Advances 2023, 3, 100501. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Choi, Y.-M.; Shin, M.-J.; Yoon, H.; Wang, X.; Lee, Y.; Yi, J.; Jeon, Y.; Desta, K.T. Exploring the Potentials of Sorghum Genotypes: A Comprehensive Study on Nutritional Qualities, Functional Metabolites, and Antioxidant Capacities. Front Nutr 2023, 10. [CrossRef]

- Espitia-Hernández, P., C.G.M., A.-V.J., D.-M.D., F.-N.A., S.T., R.-C.X. and S.-T.L., Sorghum (Sorghum Bicolor L. Moench): Chemical Composition and Its Health Benefits; Asociación Mexicana de Ciencia de los Alimentos, México, 2022; Vol. 7;

- Kanwar, P.; Yadav, R.B.; Yadav, B.S. Cross-Linking, Carboxymethylation and Hydroxypropylation Treatment to Sorghum Dietary Fiber: Effect on Physicochemical, Micro Structural and Thermal Properties. Int J Biol Macromol 2023, 233, 123638. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Liu, G.; Ning, Y.; Li, X.; Hu, S.; Zhao, J.; Qu, Y. Production of Cellulosic Ethanol and Value-Added Products from Corn Fiber. Bioresour Bioprocess 2022, 9, 81. [CrossRef]

- Colasanto, A.; Travaglia, F.; Bordiga, M.; Coïsson, J.D.; Arlorio, M.; Locatelli, M. Impact of Traditional and Innovative Cooking Techniques on Italian Black Rice (Oryza Sativa L., Artemide Cv) Composition. Food Research International 2024, 194, 114906. [CrossRef]

- Qadir, N.; Wani, I.A. Physicochemical and Functional Characterization of Dietary Fibres from Four Indian Temperate Rice Cultivars. Bioactive Carbohydrates and Dietary Fibre 2022, 28, 100336. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Ma, Q.; Deng, M.; Jia, X.; Huang, F.; Dong, L.; Zhang, R.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, M. Composition, Structural, Physicochemical and Functional Properties of Dietary Fiber from Different Milling Fractions of Black Rice Bran. LWT 2024, 195, 115743. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhang, R.; Huang, F.; Jia, X.; Dong, L.; Liu, D.; Zhang, M. Structural, Physicochemical and Functional Properties of Dietary Fiber from Black Rice Bran Treated by Different Processing Methods. Food Biosci 2025, 65, 106025. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yi, C.; Quan, K.; Lin, B. Chemical Composition, Structure, Physicochemical and Functional Properties of Rice Bran Dietary Fiber Modified by Cellulase Treatment. Food Chem 2021, 342, 128352. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Fu, Y.; Ma, Q.; Yi, J.; Cai, S. Anti-Diabetic Effects of Different Phenolic-Rich Fractions from Rhus Chinensis Mill. Fruits in Vitro. eFood 2021, 2, 37–46. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Zhao, X.; Ao, T.; Chen, Y.; Xie, J.; Gao, X.; Liu, L.; Hu, X.; Yu, Q. The Role of Bound Polyphenols in the Anti-Obesity Effects of Defatted Rice Bran Insoluble Dietary Fiber: An Insight from Multi-Omics. Food Chem 2024, 459, 140345. [CrossRef]

- 1Thomas, R., 1*Rajeev B. and 2Kuang, Y.T. Composition of Amino Acids, Fatty Acids, Minerals and Dietary Fiber in Some of the Local and Import Rice Varieties of Malaysia. Int Food Res J 2015, 22, 1148–1155.

- Bader Ul Ain, H.; Saeed, F.; Ahmed, A.; Asif Khan, M.; Niaz, B.; Tufail, T. Improving the Physicochemical Properties of Partially Enhanced Soluble Dietary Fiber through Innovative Techniques: A Coherent Review. J Food Process Preserv 2019, 43, e13917. [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Xu, X.; Chao, Z.; Jiang, X.; Zheng, L.; Jiang, B. Properties of Plant-Derived Soluble Dietary Fibers for Fiber-Enriched Foods: A Comparative Evaluation. Int J Biol Macromol 2022, 223, 1196–1207. [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, B.; Choudhary, G.; Sodhi, N.S. A Study on Physicochemical, Antioxidant and Microbial Properties of Germinated Wheat Flour and Its Utilization in Breads. J Food Sci Technol 2020, 57, 2800–2808. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Xu, T.; He, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Huang, L. Modification of Artichoke Dietary Fiber by Superfine Grinding and High-Pressure Homogenization and Its Protection against Cadmium Poisoning in Rats. Foods 2022, 11, 1716. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Anjum, F.M.; Zahoor, T.; Nawaz, H.; Din, A. Physicochemical and Functional Properties of Barley Β-glucan as Affected by Different Extraction Procedures. Int J Food Sci Technol 2009, 44, 181–187. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Hao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Li, W.; Wang, J. Physicochemical and Functional Properties of Soluble Dietary Fiber from Different Colored Quinoa Varieties (Chenopodium Quinoa Willd). J Cereal Sci 2020, 95, 103045. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Guo, X.; Bai, X.; Zhang, J.; Huo, R.; Zhang, Y. Improving the Adsorption Characteristics and Antioxidant Activity of Oat Bran by Superfine Grinding. Food Sci Nutr 2023, 11, 216–227. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Zhang, R.; Dong, L.; Huang, F.; Tang, X.; Wei, Z.; Zhang, M. Particle Size of Insoluble Dietary Fiber from Rice Bran Affects Its Phenolic Profile, Bioaccessibility and Functional Properties. LWT 2018, 87, 450–456. [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Ge, Y.; Liu, D.; Zhao, S.; Wei, M.; Jiliu, J.; Hu, X.; Quan, Z.; Wu, Y.; Su, Y.; et al. Effects of High-Temperature, High-Pressure, and Ultrasonic Treatment on the Physicochemical Properties and Structure of Soluble Dietary Fibers of Millet Bran. Front Nutr 2022, 8. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.C.; Tsai, Y.F.; Chen, C.M. Effects of Wheat Fiber, Oat Fiber, and Inulin on Sensory and Physico-Chemical Properties of Chinese-Style Sausages. Asian-Australas J Anim Sci 2011, 24, 875–880. [CrossRef]

- Giuntini, E.B.; Sardá, F.A.H.; de Menezes, E.W. The Effects of Soluble Dietary Fibers on Glycemic Response: An Overview and Futures Perspectives. Foods 2022, 11, 3934. [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.; Yu, T.; Cao, X.; Xia, H.; Wang, S.; Sun, G.; Chen, L.; Liao, W. Effect of Viscous Soluble Dietary Fiber on Glucose and Lipid Metabolism in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on Randomized Clinical Trials. Front Nutr 2023, 10. [CrossRef]

- Khorasani, A.C.; Kouhfar, F.; Shojaosadati, S.A. Pectin/Lignocellulose Nanofibers/Chitin Nanofibers Bionanocomposite as an Efficient Biosorbent of Cholesterol and Bile Salts. Carbohydr Polym 2021, 261, 117883. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Kong, X.; Xing, X.; Hu, X.; Sun, Y. Comparison of Different Technologies for Dietary Fiber Extraction from Cold-Pressed Corn Germ Meal: Changes in Structural Characteristics, Physicochemical Properties and Adsorption Capacity. J Cereal Sci 2025, 121, 104077. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wang, W.; Huang, C.; Hu, Y.; Johnston, L.; Wang, F. Dietary Supplementation With Fine-Grinding Wheat Bran Improves Lipid Metabolism and Inflammatory Response via Modulating the Gut Microbiota Structure in Pregnant Sow. Front Microbiol 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Barkas, F.; Adamidis, P.; Koutsogianni, A.-D.; Liamis, G.; Liberopoulos, E. Statin-Associated Side Effects in Patients Attending a Lipid Clinic: Evidence from a 6-Year Study. Archives of Medical Science – Atherosclerotic Diseases 2021, 6, 182–187. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, S.A.; Hartley, L.; Loveman, E.; Colquitt, J.L.; Jones, H.M.; Al-Khudairy, L.; Clar, C.; Germanò, R.; Lunn, H.R.; Frost, G.; et al. Whole Grain Cereals for the Primary or Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Yanai, H.; Adachi, H.; Hakoshima, M.; Katsuyama, H. Postprandial Hyperlipidemia: Its Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, Atherogenesis, and Treatments. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 13942. [CrossRef]

- Mortensen, M.B.; Dzaye, O.; Bøtker, H.E.; Jensen, J.M.; Maeng, M.; Bentzon, J.F.; Kanstrup, H.; Sørensen, H.T.; Leipsic, J.; Blankstein, R.; et al. Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Is Predominantly Associated With Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Events in Patients With Evidence of Coronary Atherosclerosis: The Western Denmark Heart Registry. Circulation 2023, 147, 1053–1063. [CrossRef]

- Naumann, S.; Schweiggert-Weisz, U.; Eglmeier, J.; Haller, D.; Eisner, P. In Vitro Interactions of Dietary Fibre Enriched Food Ingredients with Primary and Secondary Bile Acids. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1424. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, A.N.; Akerman, A.; Kumar, S.; Diep Pham, H.T.; Coffey, S.; Mann, J. Dietary Fibre in Hypertension and Cardiovascular Disease Management: Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses. BMC Med 2022, 20, 139. [CrossRef]

- Llanaj, E.; Dejanovic, G.M.; Valido, E.; Bano, A.; Gamba, M.; Kastrati, L.; Minder, B.; Stojic, S.; Voortman, T.; Marques-Vidal, P.; et al. Effect of Oat Supplementation Interventions on Cardiovascular Disease Risk Markers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Eur J Nutr 2022, 61, 1749–1778. [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, T.; Ojo, O.; Qiu, J.; Wang, X. Effect of Dietary Fiber (Oat Bran) Supplement in Heart Rate Lowering in Patients with Hypertension: A Randomized DASH-Diet-Controlled Clinical Trial. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3148. [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Cui, L.; Qi, J.; Ojo, O.; Du, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X. The Effect of Dietary Fiber (Oat Bran) Supplement on Blood Pressure in Patients with Essential Hypertension: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases 2021, 31, 2458–2470. [CrossRef]

- Kieffer, D.A.; Piccolo, B.D.; Marco, M.L.; Kim, E.B.; Goodson, M.L.; Keenan, M.J.; Dunn, T.N.; Knudsen, K.E.B.; Adams, S.H.; Martin, R.J. Obese Mice Fed a Diet Supplemented with Enzyme-Treated Wheat Bran Display Marked Shifts in the Liver Metabolome Concurrent with Altered Gut Bacteria. Journal of Nutrition 2016, 146, 2445–2460. [CrossRef]

- Paudel, D.; Dhungana, B.; Caffe, M.; Krishnan, P. A Review of Health-Beneficial Properties of Oats. Foods 2021, 10, 2591. [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Qiu, J.; Wang, A.; Li, Z. Impact of Whole Cereals and Processing on Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Review. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2020, 60, 1447–1474. [CrossRef]

- Torres, N.; Avila-Nava, A.; Medina-Vera, I.; Tovar, A.R. Dietary Fiber and Diabetes. In; 2020; pp. 201–218.

- Kabthymer, R.H.; Karim, M.N.; Hodge, A.M.; de Courten, B. High Cereal Fibre but Not Total Fibre Is Associated with a Lower Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: Evidence from the Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study. Diabetes Obes Metab 2023, 25, 1911–1921. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Ding, M.; Sampson, L.; Willett, W.C.; Manson, J.E.; Wang, M.; Rosner, B.; Hu, F.B.; Sun, Q. Intake of Whole Grain Foods and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: Results from Three Prospective Cohort Studies. BMJ 2020, m2206. [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari-Gohari, F.; Mousavi, S.M.; Esmaillzadeh, A. Consumption of Whole Grains and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: A Comprehensive Systematic Review and Dose–Response Meta-analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Food Sci Nutr 2022, 10, 1950–1960. [CrossRef]

- Wehrli, F.; Taneri, P.E.; Bano, A.; Bally, L.; Blekkenhorst, L.C.; Bussler, W.; Metzger, B.; Minder, B.; Glisic, M.; Muka, T.; et al. Oat Intake and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes, Cardiovascular Disease and All-Cause Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2560. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, W.; Guo, D.; Bai, B.; Bo, T.; Fan, S. Antidiabetic Effect of Millet Bran Polysaccharides Partially Mediated via Changes in Gut Microbiome. Foods 2022, 11, 3406. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-X.; Zhang, X.-X.; Zhang, R.; Ni, Z.-J.; Elam, E.; Thakur, K.; Cespedes-Acuña, C.L.; Zhang, J.-G.; Wei, Z.-J. Gut Modulation Based Anti-Diabetic Effects of Carboxymethylated Wheat Bran Dietary Fiber in High-Fat Diet/Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Mice and Their Potential Mechanisms. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2021, 152, 112235. [CrossRef]

- Shah, B. Obesity in Modern Society: Analysis, Statistics, and Treatment Approaches. International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) 2023, 12, 358–360. [CrossRef]

- 2023; FAO Food Loss and Food Waste; 2023;

- Spring, B.; Champion, K.E.; Acabchuk, R.; Hennessy, E.A. Self-Regulatory Behaviour Change Techniques in Interventions to Promote Healthy Eating, Physical Activity, or Weight Loss: A Meta-Review. Health Psychol Rev 2021, 15, 508–539. [CrossRef]

- Palmeira, A.L.; Marques, M.M.; Sánchez-Oliva, D.; Encantado, J.; Santos, I.; Duarte, C.; Matos, M.; Carneiro-Barrera, A.; Larsen, S.C.; Horgan, G.; et al. Are Motivational and Self-Regulation Factors Associated with 12 Months’ Weight Regain Prevention in the NoHoW Study? An Analysis of European Adults. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 2023, 20, 128. [CrossRef]

- Khan, J.; Gul, P.; Liu, K. Grains in a Modern Time: A Comprehensive Review of Compositions and Understanding Their Role in Type 2 Diabetes and Cancer. Foods 2024, 13, 2112. [CrossRef]

- Tammi, R.; Männistö, S.; Maukonen, M.; Kaartinen, N.E. Whole Grain Intake, Diet Quality and Risk Factors of Chronic Diseases: Results from a Population-Based Study in Finnish Adults. Eur J Nutr 2024, 63, 397–408. [CrossRef]

- Sanders, L.M.; Zhu, Y.; Wilcox, M.L.; Koecher, K.; Maki, K.C. Effects of Whole Grain Intake, Compared with Refined Grain, on Appetite and Energy Intake: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Advances in Nutrition 2021, 12, 1177–1195. [CrossRef]

- Maki, K.C.; Palacios, O.M.; Koecher, K.; Sawicki, C.M.; Livingston, K.A.; Bell, M.; Nelson Cortes, H.; McKeown, N.M. The Relationship between Whole Grain Intake and Body Weight: Results of Meta-Analyses of Observational Studies and Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1245. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Feng, J.; Liu, T.; Gong, Z.; Zhuo, Q. Association between Whole-Grain Intake and Obesity Defined by Different Anthropometric Indicators and Dose–Response Relationship Analysis among U.S. Adults: A Population-Based Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2373. [CrossRef]

- Maki, K.C.; Palacios, O.M.; Koecher, K.; Sawicki, C.M.; Livingston, K.A.; Bell, M.; Nelson Cortes, H.; McKeown, N.M. The Relationship between Whole Grain Intake and Body Weight: Results of Meta-Analyses of Observational Studies and Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1245. [CrossRef]

- Tammi, R.; Männistö, S.; Maukonen, M.; Kaartinen, N.E. Whole Grain Intake, Diet Quality and Risk Factors of Chronic Diseases: Results from a Population-Based Study in Finnish Adults. Eur J Nutr 2024, 63, 397–408. [CrossRef]

- Hosseinpour-Niazi, S.; Bakhshi, B.; Mirmiran, P.; Gaeini, Z.; Hadaegh, F.; Azizi, F. Effect of Weight Change on the Association between Overall and Source of Carbohydrate Intake and Risk of Metabolic Syndrome: Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2023, 20, 39. [CrossRef]

- Malin, S.K.; Kullman, E.L.; Scelsi, A.R.; Haus, J.M.; Filion, J.; Pagadala, M.R.; Godin, J.-P.; Kochhar, S.; Ross, A.B.; Kirwan, J.P. A Whole-Grain Diet Reduces Peripheral Insulin Resistance and Improves Glucose Kinetics in Obese Adults: A Randomized-Controlled Trial. Metabolism 2018, 82, 111–117. [CrossRef]

- Thandapilly, S.J.; Ndou, S.P.; Wang, Y.; Nyachoti, C.M.; Ames, N.P. Barley β-Glucan Increases Fecal Bile Acid Excretion and Short Chain Fatty Acid Levels in Mildly Hypercholesterolemic Individuals. Food Funct 2018, 9, 3092–3096. [CrossRef]

- Pi, X.; Yu, Z.; Yang, X.; Du, Z.; Liu, W. Effects of Zymosan on Short-Chain Fatty Acid and Gas Production in in Vitro Fermentation Models of the Human Intestinal Microbiota. Front Nutr 2022, 9. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Zeng, X.; Wei, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Zheng, X. Improvement of the Functional Properties of Insoluble Dietary Fiber from Corn Bran by Ultrasonic-Microwave Synergistic Modification. Ultrason Sonochem 2024, 104, 106817. [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Hemsworth, G.R.; Déjean, G.; Rogers, T.E.; Pudlo, N.A.; Urs, K.; Jain, N.; Davies, G.J.; Martens, E.C.; Brumer, H. Molecular Mechanism by Which Prominent Human Gut Bacteroidetes Utilize Mixed-Linkage Beta-Glucans, Major Health-Promoting Cereal Polysaccharides. Cell Rep 2017, 21, 417–430. [CrossRef]

- Sebastià, C.; Folch, J.M.; Ballester, M.; Estellé, J.; Passols, M.; Muñoz, M.; García-Casco, J.M.; Fernández, A.I.; Castelló, A.; Sánchez, A.; et al. Interrelation between Gut Microbiota, SCFA, and Fatty Acid Composition in Pigs. mSystems 2024, 9. [CrossRef]

- Valido, E.; Stoyanov, J.; Bertolo, A.; Hertig-Godeschalk, A.; Zeh, R.M.; Flueck, J.L.; Minder, B.; Stojic, S.; Metzger, B.; Bussler, W.; et al. Systematic Review of the Effects of Oat Intake on Gastrointestinal Health. J Nutr 2021, 151, 3075–3090. [CrossRef]

- Procházková, N.; Venlet, N.; Hansen, M.L.; Lieberoth, C.B.; Dragsted, L.O.; Bahl, M.I.; Licht, T.R.; Kleerebezem, M.; Lauritzen, L.; Roager, H.M. Effects of a Wholegrain-Rich Diet on Markers of Colonic Fermentation and Bowel Function and Their Associations with the Gut Microbiome: A Randomised Controlled Cross-over Trial. Front Nutr 2023, 10. [CrossRef]

- Thandapilly, S.J.; Ndou, S.P.; Wang, Y.; Nyachoti, C.M.; Ames, N.P. Barley β-Glucan Increases Fecal Bile Acid Excretion and Short Chain Fatty Acid Levels in Mildly Hypercholesterolemic Individuals. Food Funct 2018, 9, 3092–3096. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xue, K.; Iversen, K.N.; Qu, Z.; Dong, C.; Jin, T.; Hallmans, G.; Åman, P.; Johansson, A.; He, G.; et al. The Effects of Fermented Rye Products on Gut Microbiota and Their Association with Metabolic Factors in Chinese Adults – an Explorative Study. Food Funct 2021, 12, 9141–9150. [CrossRef]

- Faubel, N.; Blanco-Morales, V.; Barberá, R.; Garcia-Llatas, G. Impact of Colonic Fermentation of Plant Sterol-Enriched Rye Bread on Gut Microbiota and Metabolites. In Proceedings of the Foods 2023; MDPI: Basel Switzerland, October 13 2023; p. 87.

- Jefferson, A.; Adolphus, K. The Effects of Intact Cereal Grain Fibers, Including Wheat Bran on the Gut Microbiota Composition of Healthy Adults: A Systematic Review. Front Nutr 2019, 6.

- Vitaglione, P.; Mennella, I.; Ferracane, R.; Rivellese, A.A.; Giacco, R.; Ercolini, D.; Gibbons, S.M.; La Storia, A.; Gilbert, J.A.; Jonnalagadda, S.; et al. Whole-Grain Wheat Consumption Reduces Inflammation in a Randomized Controlled Trial on Overweight and Obese Subjects with Unhealthy Dietary and Lifestyle Behaviors: Role of Polyphenols Bound to Cereal Dietary Fiber. Am J Clin Nutr 2015, 101, 251–261. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Y.; Chang, X.; Lin, J.; Chen, L.; Lyu, Q.; Chen, X.; Ding, W. Examination of the Bioavailability and Bioconversion of Wheat Bran-Bound Ferulic Acid: Insights into Gastrointestinal Processing and Colonic Metabolites. J Agric Food Chem 2025, 73, 1331–1344. [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Xue, K.; Kan, J. Use of Dietary Fibers in Reducing the Risk of Several Cancer Types: An Umbrella Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2545. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-F.; Wang, X.-K.; Tang, Y.-J.; Guan, X.-X.; Guo, Y.; Fan, J.-M.; Cui, L.-L. Association of Whole Grains Intake and the Risk of Digestive Tract Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutr J 2020, 19, 52. [CrossRef]

- Collatuzzo, G.; Cortez Lainez, J.; Pelucchi, C.; Negri, E.; Bonzi, R.; Palli, D.; Ferraroni, M.; Zhang, Z.-F.; Yu, G.-P.; Lunet, N.; et al. The Association between Dietary Fiber Intake and Gastric Cancer: A Pooled Analysis of 11 Case–Control Studies. Eur J Nutr 2024, 63, 1857–1865. [CrossRef]

- Hullings, A.G.; Sinha, R.; Liao, L.M.; Freedman, N.D.; Graubard, B.I.; Loftfield, E. Whole Grain and Dietary Fiber Intake and Risk of Colorectal Cancer in the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study Cohort. Am J Clin Nutr 2020, 112, 603–612. [CrossRef]

- Kyrø, C.; Tjønneland, A.; Overvad, K.; Olsen, A.; Landberg, R. Higher Whole-Grain Intake Is Associated with Lower Risk of Type 2 Diabetes among Middle-Aged Men and Women: The Danish Diet, Cancer, and Health Cohort. J Nutr 2018, 148, 1434–1444. [CrossRef]

- Makarem, N.; Nicholson, J.M.; Bandera, E. V.; McKeown, N.M.; Parekh, N. Consumption of Whole Grains and Cereal Fiber in Relation to Cancer Risk: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies. Nutr Rev 2016, 74, 353–373. [CrossRef]

- Procházková, N.; Venlet, N.; Hansen, M.L.; Lieberoth, C.B.; Dragsted, L.O.; Bahl, M.I.; Licht, T.R.; Kleerebezem, M.; Lauritzen, L.; Roager, H.M. Effects of a Wholegrain-Rich Diet on Markers of Colonic Fermentation and Bowel Function and Their Associations with the Gut Microbiome: A Randomised Controlled Cross-over Trial. Front Nutr 2023, 10. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yang, W.; Petrick, J.L.; Liao, L.M.; Wang, W.; He, N.; Campbell, P.T.; Zhang, Z.-F.; Giovannucci, E.; McGlynn, K.A.; et al. Higher Intake of Whole Grains and Dietary Fiber Are Associated with Lower Risk of Liver Cancer and Chronic Liver Disease Mortality. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 6388. [CrossRef]

- Kubatka, P.; Kello, M.; Kajo, K.; Kruzliak, P.; Výbohová, D.; Šmejkal, K.; Maršík, P.; Zulli, A.; Gönciová, G.; Mojžiš, J.; et al. Young Barley Indicates Antitumor Effects in Experimental Breast Cancer In Vivo and In Vitro. Nutr Cancer 2016, 68, 611–621. [CrossRef]

- Choromanska, A.; Kulbacka, J.; Harasym, J.; Oledzki, R.; Szewczyk, A.; Saczko, J. High- and Low-Molecular Weight Oat Beta-Glucan Reveals Antitumor Activity in Human Epithelial Lung Cancer. Pathology & Oncology Research 2018, 24, 583–592. [CrossRef]

- Harasym, J.; Dziendzikowska, K.; Kopiasz, Ł.; Wilczak, J.; Sapierzyński, R.; Gromadzka-Ostrowska, J. Consumption of Feed Supplemented with Oat Beta-Glucan as a Chemopreventive Agent against Colon Cancerogenesis in Rats. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1125. [CrossRef]

- Celiberto, F.; Aloisio, A.; Girardi, B.; Pricci, M.; Iannone, A.; Russo, F.; Riezzo, G.; D’Attoma, B.; Ierardi, E.; Losurdo, G.; et al. Fibres and Colorectal Cancer: Clinical and Molecular Evidence. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 13501. [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, A.K.; Brunius, C.; Mazidi, M.; Hellström, P.M.; Risérus, U.; Iversen, K.N.; Fristedt, R.; Sun, L.; Huang, Y.; Nørskov, N.P.; et al. Effects of Whole-Grain Wheat, Rye, and Lignan Supplementation on Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in Men with Metabolic Syndrome: A Randomized Crossover Trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2020, 111, 864–876. [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, J.C.; Björck, I.M.E.; Nilsson, A.C. Rye-Based Evening Meals Favorably Affected Glucose Regulation and Appetite Variables at the Following Breakfast; A Randomized Controlled Study in Healthy Subjects. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0151985. [CrossRef]

- Iversen, K.N.; Jonsson, K.; Landberg, R. The Effect of Rye-Based Foods on Postprandial Plasma Insulin Concentration: The Rye Factor. Front Nutr 2022, 9. [CrossRef]

- Iversen, K.N.; Carlsson, F.; Andersson, A.; Michaëlsson, K.; Langton, M.; Risérus, U.; Hellström, P.M.; Landberg, R. A Hypocaloric Diet Rich in High Fiber Rye Foods Causes Greater Reduction in Body Weight and Body Fat than a Diet Rich in Refined Wheat: A Parallel Randomized Controlled Trial in Adults with Overweight and Obesity (the RyeWeight Study). Clin Nutr ESPEN 2021, 45, 155–169. [CrossRef]

- Iversen, K.N.; Dicksved, J.; Zoki, C.; Fristedt, R.; Pelve, E.A.; Langton, M.; Landberg, R. The Effects of High Fiber Rye, Compared to Refined Wheat, on Gut Microbiota Composition, Plasma Short Chain Fatty Acids, and Implications for Weight Loss and Metabolic Risk Factors (the RyeWeight Study). Nutrients 2022, 14, 1669. [CrossRef]

- Dioum, E.H.M.; Schneider, K.L.; Vigerust, D.J.; Cox, B.D.; Chu, Y.; Zachwieja, J.J.; Furman, D. Oats Lower Age-Related Systemic Chronic Inflammation (IAge) in Adults at Risk for Cardiovascular Disease. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4471. [CrossRef]

- Pino, J.L.; Mujica, V.; Arredondo, M. Effect of Dietary Supplementation with Oat β-Glucan for 3 months in Subjects with Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Controlled Clinical Trial. J Funct Foods 2021, 77, 104311. [CrossRef]

- Fiedler, M.; Müller, N.; Kloos, C.; Kramer, G.; Kellner, C.; Schmidt, S.; Wolf, G.; Kuniß, N. A Randomized Controlled Trial to Assess the Feasibility and Practicability of an Oatmeal Intervention in Individuals with Type 2 Diabetes: A Pilot Study in the Outpatient Sector. J Clin Med 2024, 13, 5126. [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Hong, C.; Huang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yu, Z.; Li, S.; Guan, X.; Zhao, W. Oat β-Glucan Prevents High Fat Diet Induced Obesity by Targeting Ileal Farnesoid X Receptor-Fibroblast Growth Factor 15 Signaling. Int J Biol Macromol 2025, 306, 141543. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, R.L.; Horn, W.F.; Wen, A.; Rust, B.; Woodhouse, L.R.; Newman, J.W.; Keim, N.L. Resistant Starch Wheat Increases PYY and Decreases GIP but Has No Effect on Self-Reported Perceptions of Satiety. Appetite 2022, 168, 105802. [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.; Hermes, G.D.A.; Emanuel E., C.; Holst, J.J.; Zoetendal, E.G.; Smidt, H.; Troost, F.; Schaap, F.G.; Damink, S.O.; Jocken, J.W.E.; et al. Effect of Wheat Bran Derived Prebiotic Supplementation on Gastrointestinal Transit, Gut Microbiota, and Metabolic Health: A Randomized Controlled Trial in Healthy Adults with a Slow Gut Transit. Gut Microbes 2020, 12, 1704141. [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.M.; Choo, J.M.; Li, H.; O’Rielly, R.; Carragher, J.; Rogers, G.B.; Searle, I.; Robertson, S.A.; Page, A.J.; Muhlhausler, B. A High Amylose Wheat Diet Improves Gastrointestinal Health Parameters and Gut Microbiota in Male and Female Mice. Foods 2021, 10, 220. [CrossRef]

- Liedike, B.; Khatib, M.; Tabarsi, B.; Harris, M.; Wilson, S.L.; Ortega-Santos, C.P.; Mohr, A.E.; Vega-López, S.; Whisner, C.M. Evaluating the Effects of Corn Flour Product Consumption on Cardiometabolic Outcomes and the Gut Microbiota in Adults with Elevated Cholesterol: A Randomized Crossover. J Nutr 2024, 154, 2437–2447. [CrossRef]

- Kondo, K.; Morino, K.; Nishio, Y.; Ishikado, A.; Arima, H.; Nakao, K.; Nakagawa, F.; Nikami, F.; Sekine, O.; Nemoto, K.; et al. Fiber-Rich Diet with Brown Rice Improves Endothelial Function in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Randomized Controlled Trial. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0179869. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; An, Y.; Yang, N.; Xu, Y.; Wang, G. Longitudinal Associations of Dietary Fiber and Its Source with 48-Week Weight Loss Maintenance, Cardiometabolic Risk Factors and Glycemic Status under Metformin or Acarbose Treatment: A Secondary Analysis of the March Randomized Trial. Nutr Diabetes 2024, 14, 81. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, A.N.; Akerman, A.P.; Mann, J. Dietary Fibre and Whole Grains in Diabetes Management: Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses. PLoS Med 2020, 17, e1003053. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).