Submitted:

03 June 2025

Posted:

05 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

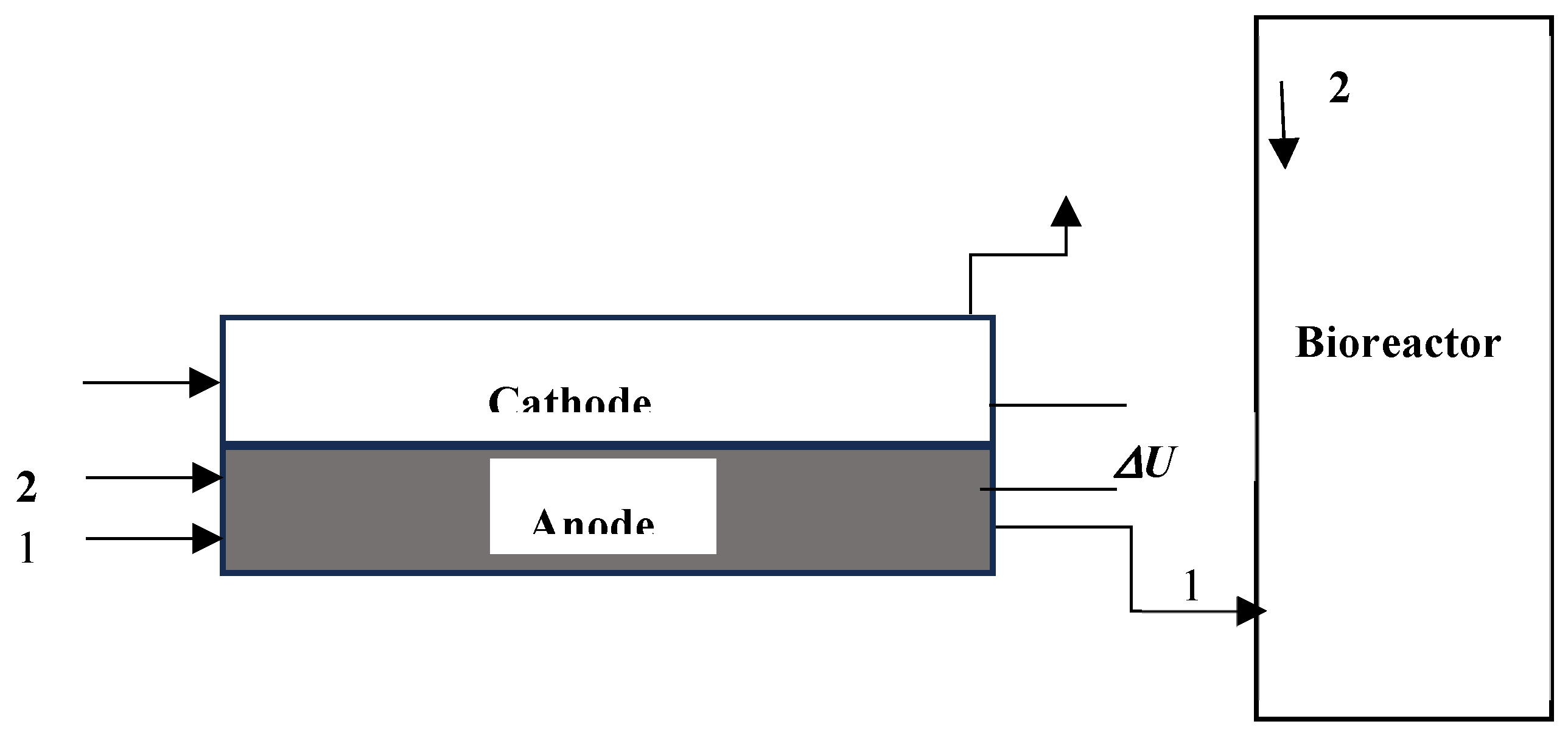

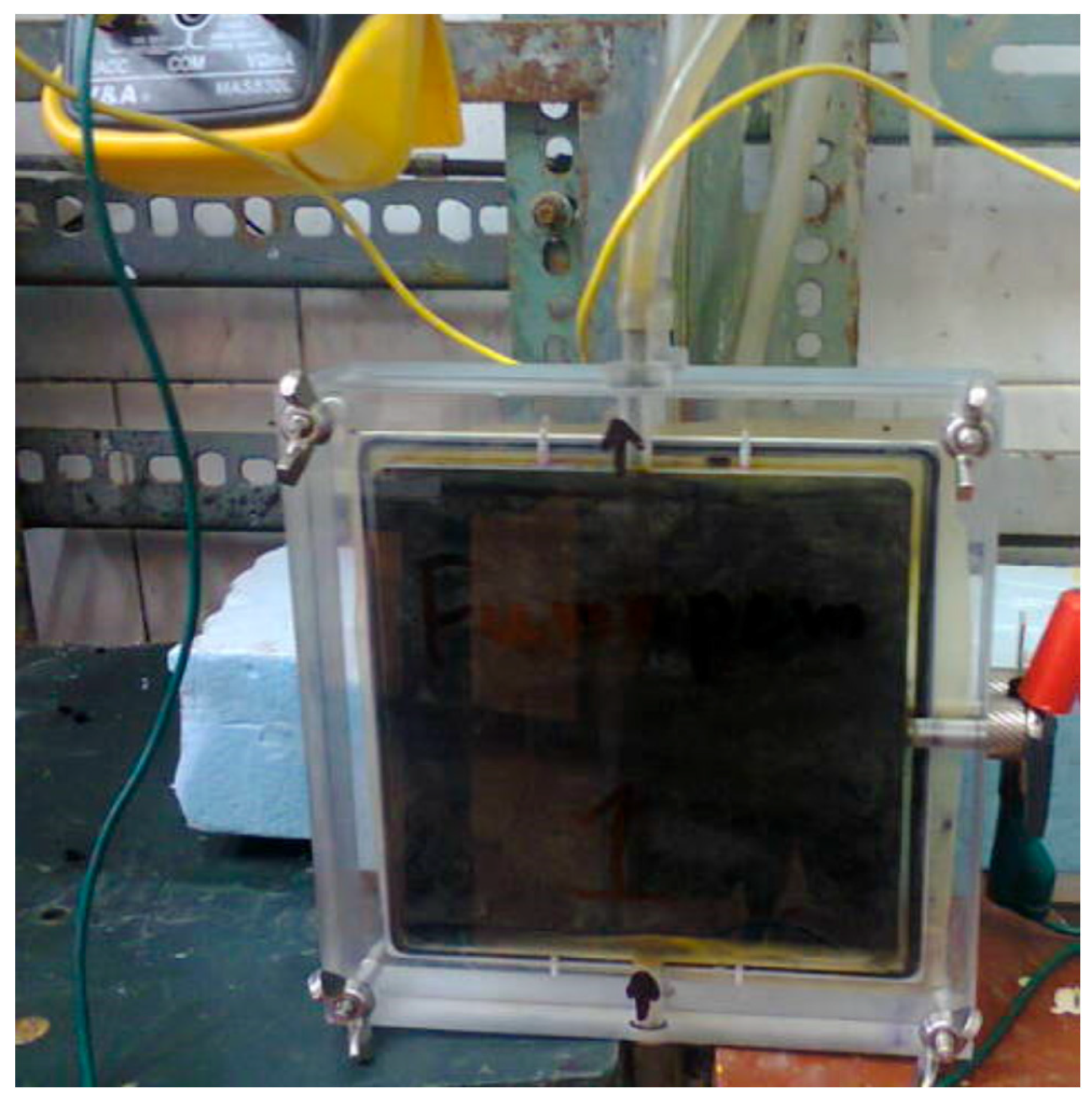

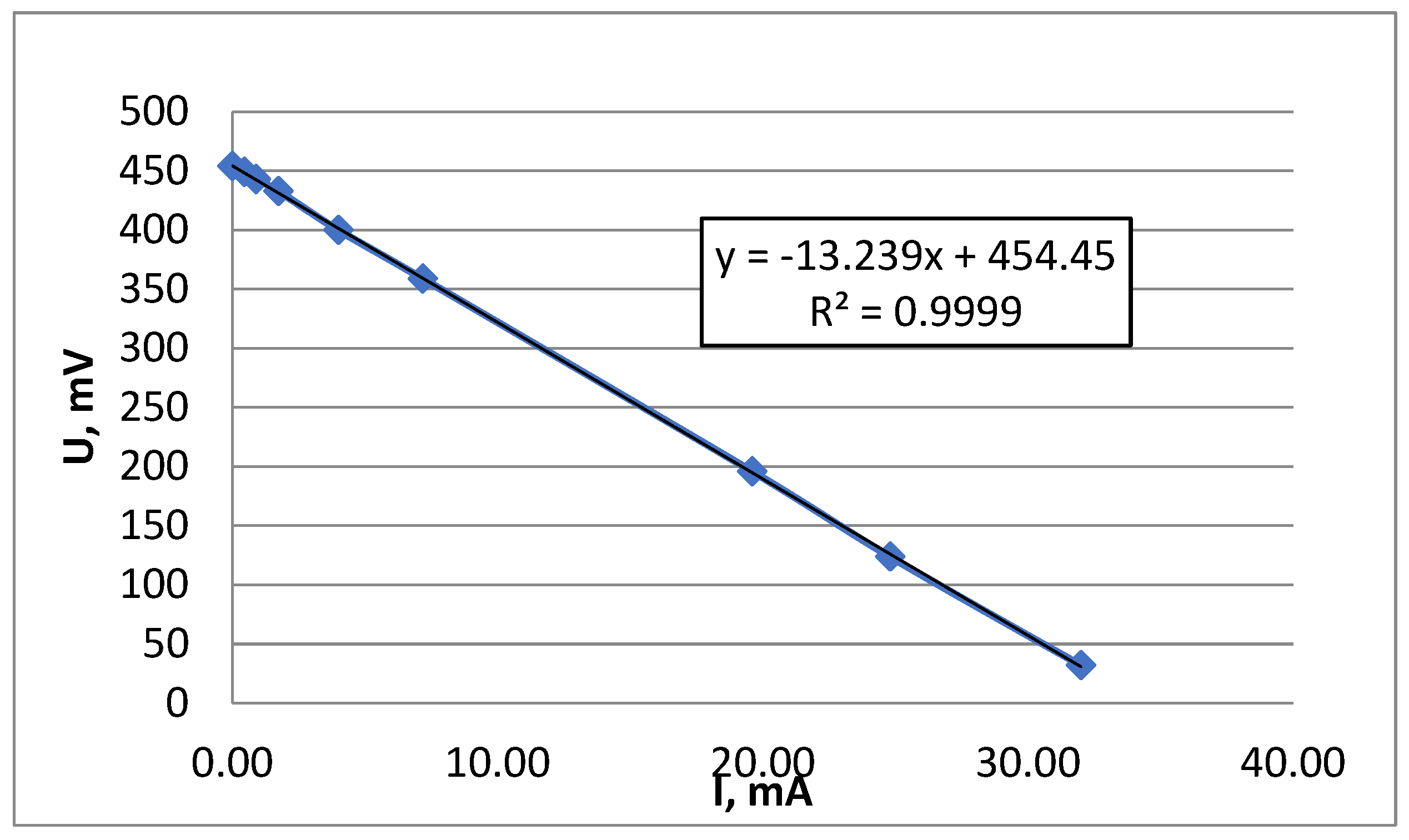

1.1. Fuel Cell Experiments

1.1. Biogas Production

3. Results

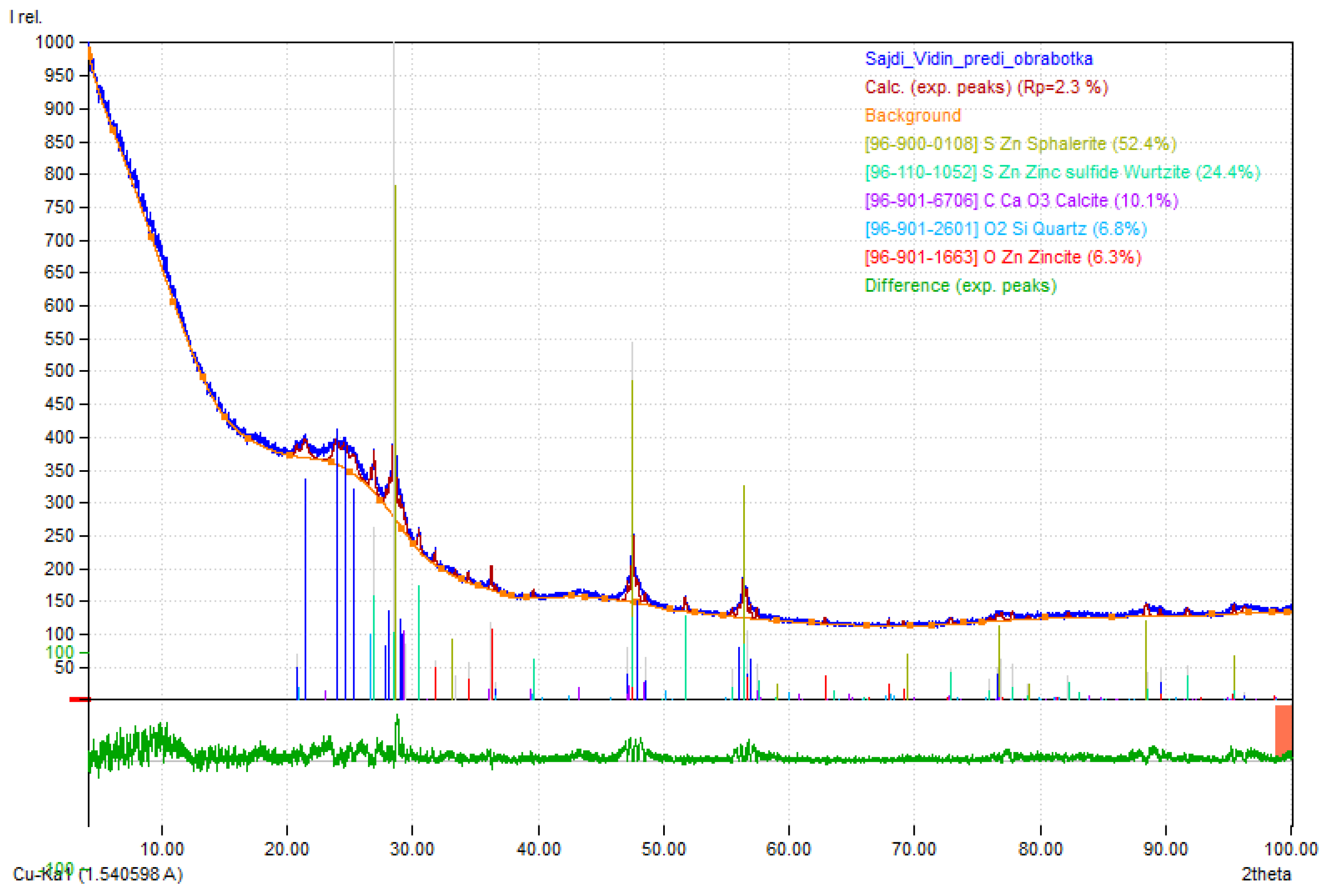

3.1. The Sorbent Composition

3.2. Sulfide Sorption and Removal

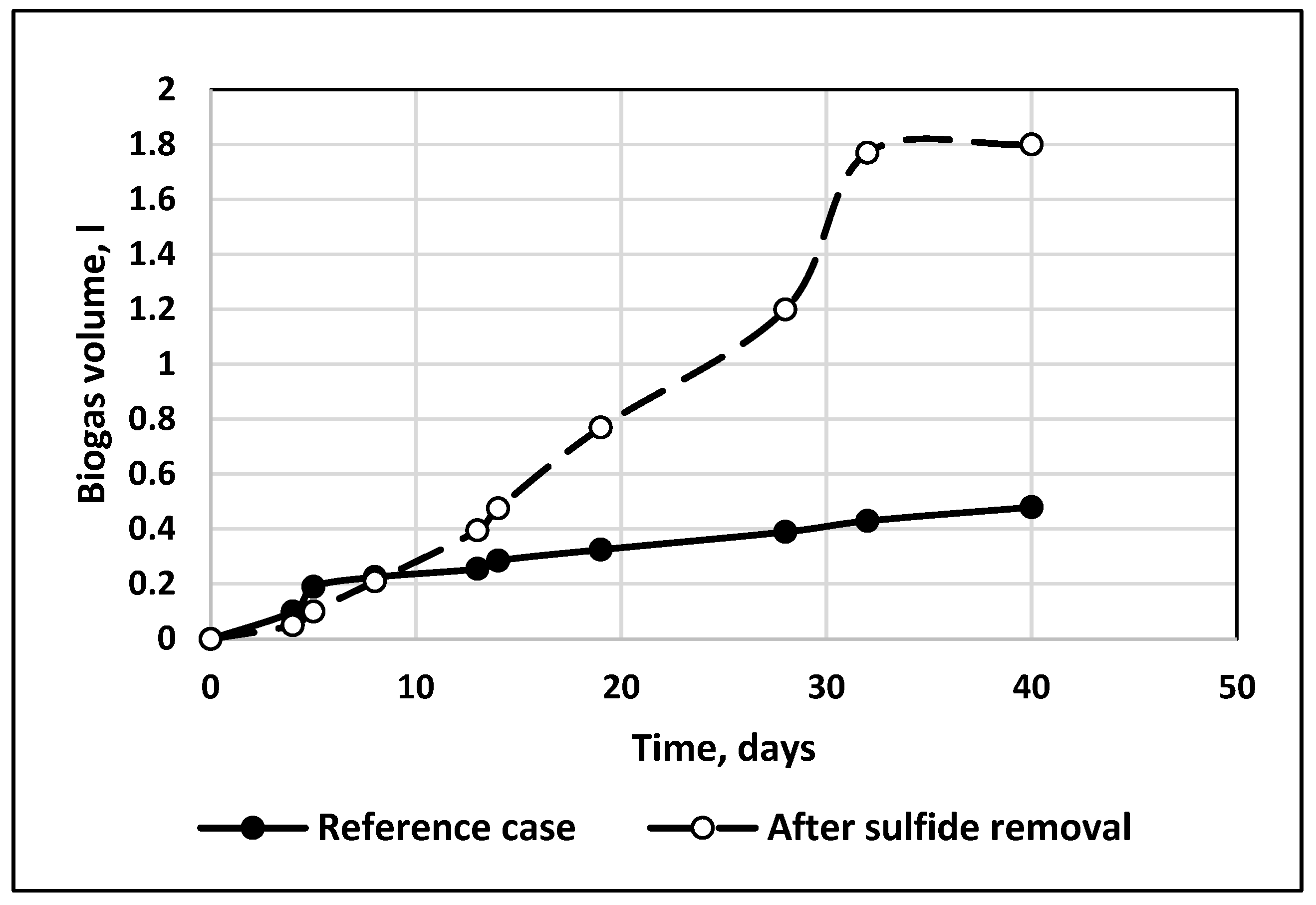

3.3. Biogas Production

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- A simple method for hydrogen sulfide removal from aqueous solutions is proposed. It consists in capturing sulfide anions by chemo-sorption on zinc oxide attached to carbon-based carrier with the consequent sorbent recovery in a fuel cell mode. The sulfide removal is accompanied by energy production to help the process performance. There is multiple effect of sulfide removal and utilization as energy combined with water pre-treatment for various purposes.

- In the present study the treatment of waste streams from alcohol, beverage and milk manufacturing to be used for biogas production is presented. Complete sulfide removal was attained.

- The method can be extended for treatment of sulfide containing mineral waters and waste streams enabling the use of the purified water for industrial purposes.

- The yield of biogas produced from vinasse was increased up to four times for treated substrate compared to the reference case.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Midilli, A.; Ay, M.; Kale, A.; Nejat Veziroglu, T. A parametric investigation of hydrogen energy potential based on H2S in Black Sea deep waters. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2007, 32, 117–124. [CrossRef]

- Jangam, K.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Qin, L.; Fan, L.-S.; Perspectives on reactive separation and removal of hydrogen sulfide. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2021, X 1, 100105. [CrossRef]

- 8 Innovations in Hydrogen Sulfide Removal, Oil Field Team, The Oil & Gas Hub, 2024.09. 8 Innovations in Hydrogen Sulfide Removal.

- Pudi, A,; Rezae, M.; Baschetti, M.G.; Signorini, V.; Mansouri, S.S. Hydrogen sulfide capture and removal technologies: A comprehensive review of recent developments and emerging trends. Separ. Purif. Technol. 2022, 298, 121448. [CrossRef]

- Vikrant, K.; Suresh Kumar Kailasa, S.K.; Tsang, D.C.W.; Sang Soo Lee, S.S.; Kumar, P.; Giri, B.S.; Ram Sharan Singh, R.S.; Kim, K.H. Biofiltration of hydrogen sulfide: Trends and challenges, J. Cleaner Prod. 2018, 187, 131-147. [CrossRef]

- Dutta, P.K.; Rabaey, K.; Yuan, Z.; Keller, J. Spontaneous electrochemical removal of aqueous sulfide. Water Res. 2008, 42, 4965–4975. [CrossRef]

- Beschkov, V.; Razkazova-Velkova, E.; Martinov, M.; Stefanov, S. Electricity Production from Marine Water by Sulfide-Driven Fuel Cell, Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1926.;. [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, M.B.; Ghanegaonkar, P.M.Hydrogen sulfide removal from biogas using chemical absorption technique in packed column reactors. Global J. Environ. Sci. Manag. 2019, 5, 155-166.. [CrossRef]

- Stefanov, S.; Uzun D.; L. Ljutzkanov, L.; V. Beschkov, V. Sulfide driven fuel cell performance enhanced by integrated chemosorption and electricity generation., Bul. Chem. Commun. 2024, 56, 379-387.

- Suhotin, A.M. Guidebook on Electrochemistry (in Russian); Himia: Leningrad, Russia, 1981.

- Rees, T.D.; Gyllenpetz, A.B.; Docherty, A.C. The determination of trace amounts of sulphide in condensed steam with N-diethyl-P-phenylenediamine. Analyst 1971, 96, 201–208. [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, A.; Gyawali, R.; Lens, P.N.L. Lohani, S.P. Technologies for removal of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) from biogas, Chapter 11 in: Emerging Technologies and Biological Systems for Biogas Upgrading, Editors: Aryal, N.; Ottosen, L.D.M.; Kofoed, M.V.W.; Pant, D. Academic Press, Cambridge, Ma. U.S.A. 2021, pp. 295-320. [CrossRef]

- Fonseca-Bermúdez, Ó.J.; Giraldo, L.; Sierra-Ramírez, R.; Giraldo, L.; Moreno-Piraján, J.C. Removal of hydrogen sulfide from biogas by adsorption and photocatalysis: a review. Environ Chem Lett. 2023, 21, 1059–1073. [CrossRef]

| No. | Reversible anode reaction | Number of exchanged electrons, n | Standard electrode potential, V, 25oC |

| 1 | SO3 2− + 3H2O + 6e = S2− + 6OH− | 6 | -0.91 |

| 2 | SO4 2− + H2O + 2e = SO3 2− + 2OH− | 2 | -0.66 |

| 3 | S22− + 2e = 2S2− | 1 | -0.524 |

| 4 | S + 2e = S2− | 2 | -0.480 |

| 5 | S2O3 2− + 6H+ +8e = 2S2− + 3H2O | 4 | -0.006 |

| 6 | SO4 2− + 4H2O + 8e = S2− + 8OH− | 8 | -0,693 |

| Substrate | Sulfide concentration, mg dm-3 | Open circuit voltage, V |

| Vinasse | 54.3 | 0.37 |

| Vinasse | 62.3 | 0.37 |

| Whey | 182 | 0.52 |

| Whey | 358 | 0.47 |

| Whey | 392 | 0.51 |

| Stillage | 18 | 0.30 |

| Stillage | 39.7 | 0.34 |

| Stillage | 79.1 | 0.45 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).