Perivascular spaces of this type (IV) were first clearly documented with MRI imaging in 2020 [

1,

2], but there is still insufficient documentation of radiological characteristics with vasogenic edema. Type IV PVS are typically found in the anterior temporal lobe and closely associated with middle cerebral artery M2 and M3 segment branches in the white matter of the brain.

These PVS are frequently associated with perifocal edema, likely due to the region’s loose white matter structure and increased interstitial fluid permeability around small penetrating vessels. It should be emphasized that the presence of perifocal edema does not necessarily indicate an active pathological process; it may represent a reactive or structural phenomenon without clinical significance, particularly in elderly individuals [

3,

4]. Perifocal edema surrounding an opercular perivascular space can range from minimal to very profound and is found in roughly 80% of cases of type IV PVS [

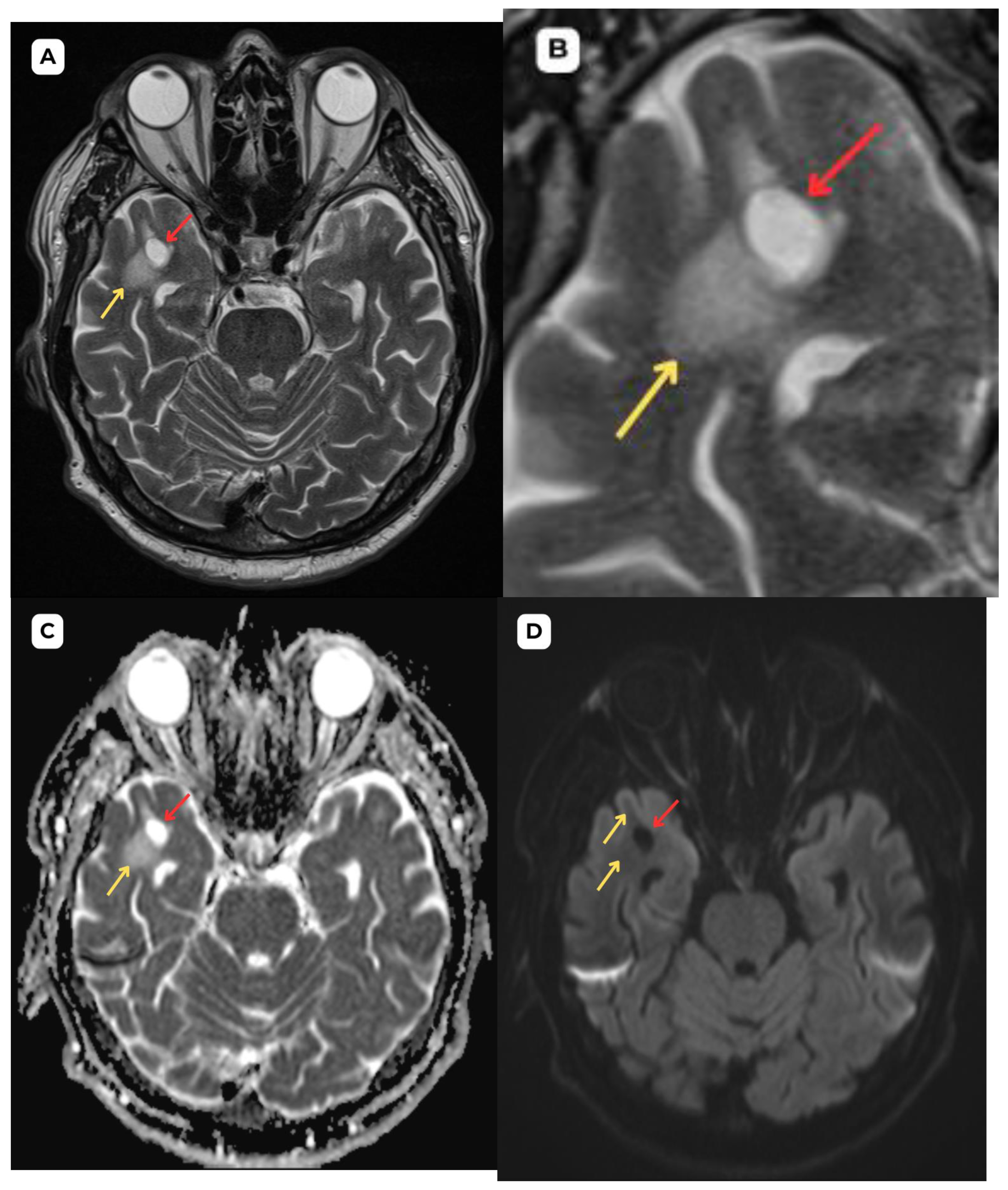

5]. In this case, the first patient had more pronounced perifocal edema in both the initial MRI examination (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2) and the one-year follow-up MRI (

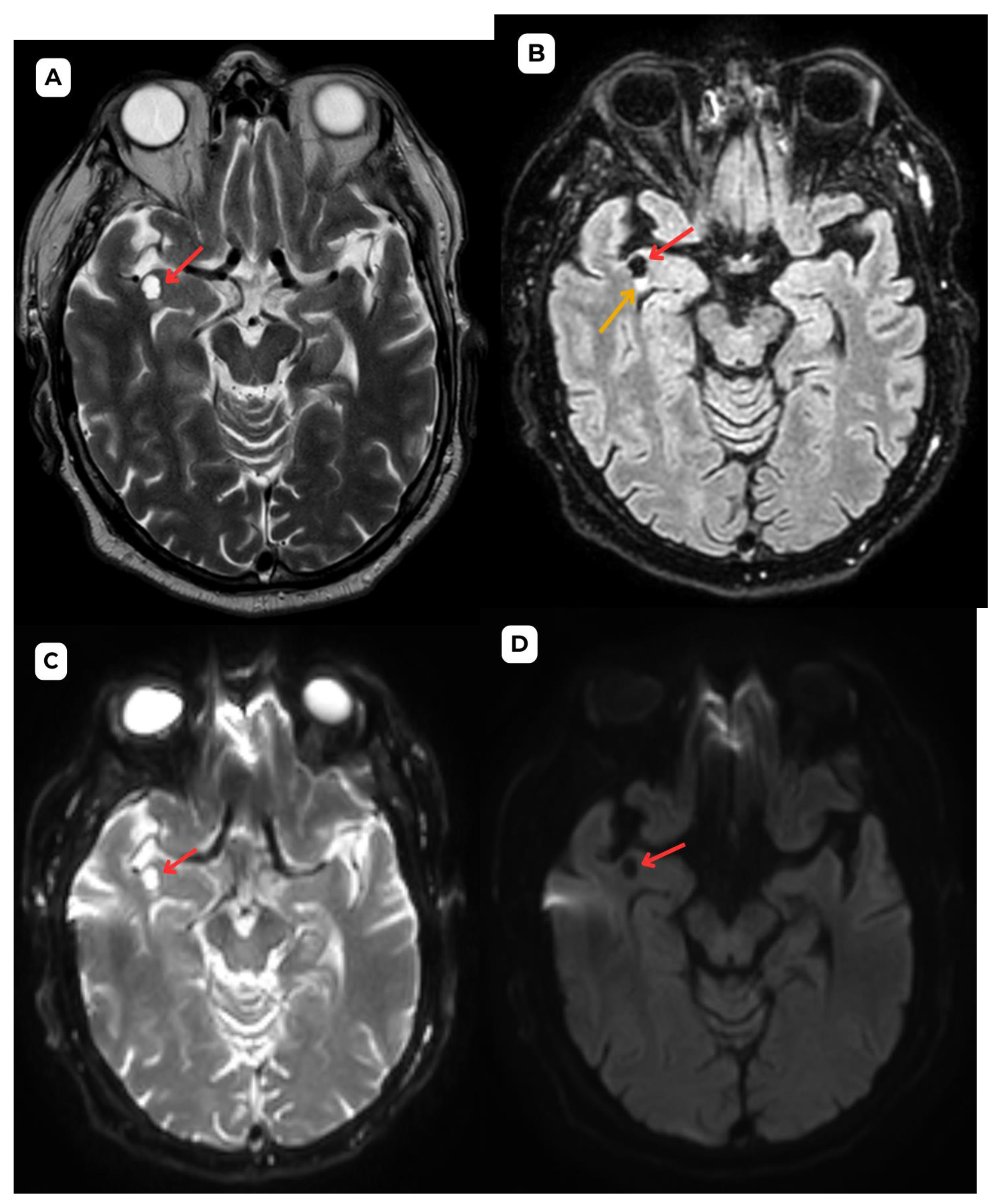

Figure 3) than the second patient (

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6).

In magnetic resonance imaging, the signal intensity of the opercular perivascular spaces themselves is identical to that of cerebrospinal fluid in all sequences—hypointense on T1W1 and FLAIR, hyperintense on T2W1, and the ADC value corresponds to cerebrospinal fluid [

6,

7]. In both of these cases, MRI images were acquired with the Siemens “MAGNETOM Sola” 1.5T system. In both cases, cerebrospinal fluid signal is visible in all MRI sequences. In the images, these PVS are located very close to the branches of the middle cerebral artery, which come into contact with the cerebral cortex, with MRI showing regional cortical thinning in the brain [

6,

7].

The presence of cerebrospinal fluid intensity tracts in the images is also useful as a radiological criterion for the diagnosis of perivascular spaces [

1]. All the above-mentioned features help distinguish opercular perivascular spaces from neuroglial tumors with characteristic perifocal edema.

In MRI imaging, opercular perivascular spaces can also be differentiated based on their appearance: round, oval, or tubular, well-defined cystic structures that do not contain calcifications, hemorrhagic elements, or high-protein content structures. In both cases, opercular perivascular spaces appear round (

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). These formations do not enhance with contrast, which also helps to distinguish them from other pathologies. In both of the cases no contrast enhancement was seen (

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). It is important to highlight the pathognomonic feature—visualization of the perforating central artery of the perivascular space—using TOF combined with 3D CISS sequences [

8].

Figure 5.

Accompanying second patient: brain MRI of a 67-year-old male. (A): Susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI) axial. A cystic lesion (red arrow) is seen without any hemosiderin or blood products surrounding it. (B): T2-weighted sequence axial, zoomed in, demonstrates better visualization of the very minimal perifocal edema/gliosis (yellow arrow) around the cystic lesion (red arrow) in the white matter. Red arrow—opercular (type IV) perivascular space, yellow arrow—surrounding edema.

Figure 5.

Accompanying second patient: brain MRI of a 67-year-old male. (A): Susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI) axial. A cystic lesion (red arrow) is seen without any hemosiderin or blood products surrounding it. (B): T2-weighted sequence axial, zoomed in, demonstrates better visualization of the very minimal perifocal edema/gliosis (yellow arrow) around the cystic lesion (red arrow) in the white matter. Red arrow—opercular (type IV) perivascular space, yellow arrow—surrounding edema.

Figure 6.

Accompanying second patient: One-year follow-up brain MRI of a 67-year-old male. (A): T2-weighted sequence and (B): T2-FLAIR one-year follow-up MRI demonstrates no changes in the cystic lesion (red arrows) and surrounding structures. The minimal perifocal edema or gliosis (yellow arrows) has remained stable; no changes in size or signal intensity can be seen. These findings serve as an important criterion in uncertain cases of PVS; they are likely of a benign nature and consistent with an opercular (type IV) perivascular space. Red arrow—opercular (type IV) perivascular space, yellow arrow—surrounding edema.

Figure 6.

Accompanying second patient: One-year follow-up brain MRI of a 67-year-old male. (A): T2-weighted sequence and (B): T2-FLAIR one-year follow-up MRI demonstrates no changes in the cystic lesion (red arrows) and surrounding structures. The minimal perifocal edema or gliosis (yellow arrows) has remained stable; no changes in size or signal intensity can be seen. These findings serve as an important criterion in uncertain cases of PVS; they are likely of a benign nature and consistent with an opercular (type IV) perivascular space. Red arrow—opercular (type IV) perivascular space, yellow arrow—surrounding edema.

Since low-grade neuroglial tumors show similar signals in standard MRI sequences, functional MRI, MR spectroscopy, and dynamic perfusion—which are based on tumor-induced metabolic changes and molecular mechanisms—play an important role in their diagnosis [

9].

Researchers propose using fluid-suppressed Amide Proton Transfer weighted imaging to aid in the differential diagnosis of vast T2/FLAIR hyperintensity zones in anterior temporal perivascular spaces, which are primarily caused by glial tumors [

10]. The method is based on detecting amide signal intensity—in tumor tissues, an increase in APTw signal is observed, whereas in the case of enlarged perivascular spaces, the images do not demonstrate increased signal [

10]. A publication describes three clinical cases in which the use of this method influenced an early change in the diagnosis from a primary neoplastic disease to a perivascular space [

10].

The stability of the lesion and surrounding tissue over the one-year period is reassuring. However, the need for continued monitoring in such cases remains a subject of discussion, as some studies suggest that these lesions tend to remain stable and do not require further follow-up unless there are significant changes [

1]. For example, in a study by McArdle et al., 18 patients with opercular perivascular cysts were analyzed. Of the 13 patients who underwent follow-up over a period ranging from 2 months to 10 years, 11 showed no change in cyst size, and only one patient demonstrated a slight increase over a 7-month period [

1]. These findings support the notion of long-term structural stability. Additionally, sources such as Radiopaedia.org highlight that opercular (type IV) perivascular spaces, when presenting with typical features, are considered benign and often do not require further imaging unless clinical symptoms or atypical imaging features are present.

On the other hand, several authors suggest that such lesions, once identified correctly, typically require only follow-up imaging for monitoring [

11,

12]. Contrary to the generally stable nature of enlarged perivascular spaces over time, serial MRI studies show a prolonged increase in the size of low-grade neuroglial tumors, averaging 4.1 mm per year [

13]. In this case, the aforementioned changes have remained stable over a one-year follow-up MRI.

Literature on perivascular spaces, particularly type IV opercular perivascular spaces, is limited in documenting cases with or without surrounding vasogenic edema, and there are not many publications with detailed and structured radiologic images, especially zoomed-in images. This highlights the need for further publications that can provide a clear radiological depiction of such cases. Further studies and imaging examples are necessary to improve diagnostic accuracy and provide a comprehensive understanding of these benign structures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.T. and A.B.; methodology, R.T. and A.B.; validation, R.T. and A.B.; formal analysis, R.T. and A.B.; investigation, R.T. and A.B.; resources, R.T. and A.B.; data curation, R.T., A.B., C.E.; writing—original draft preparation, R.T. and A.B.; writing—review and editing, R.T., A.B., C.E.; visualization, R.T. and A.B.; supervision, A.B. and C.E.; project administration, A.B.; funding acquisition, A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, as it is a retrospective case series, which did not impact the management of the patients.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to our colleagues in radiology and neurology at Pauls Stradins Clinical University Hospital, the Institute of Diagnostic Radiology, and the Department of Neurology.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- McArdle, D.J.T.; Lovell, T.J.H.; Lekgabe, E.; Gaillard, F. Opercular perivascular cysts: A proposed new subtype of dilated perivascular spaces. European Journal of Radiology 2020, 124, 108838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capasso, R.; Negro, A.; Cirillo, S.; et al. Large anterior temporal Virchow–Robin spaces: Evaluating MRI features over the years—Our experience and literature review. Clinical and Translational Neuroscience 2020, 4, 2514183X2090525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doubal, F.N.; MacLullich, A.M.J.; Ferguson, K.J.; Dennis, M.S.; Wardlaw, J.M. Enlarged Perivascular Spaces on MRI Are a Feature of Cerebral Small Vessel Disease. Stroke 2010, 41, 450–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wardlaw, J.M.; Smith, C.; Dichgans, M. Small vessel disease: mechanisms and clinical implications. The Lancet Neurology 2019, 18, 684–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, A.T.; Chandra, R.V.; Trost, N.M.; McKelvie, P.A.; Stuckey, S.L. Large anterior temporal Virchow-Robin spaces: unique MR imaging features. Neuroradiology 2015, 57, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, I.; McArdle, D.J.T.; Gaillard, F. Opercular Perivascular Cyst: Old Entity, New Location. Neurographics 2021, 11, 186–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Hu, X.; Li, H.; Zhao, Y. Perivascular Spaces, Glymphatic System and MR. Frontiers in Neurology 2022, 13, 844938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conforti, R.; Capasso, R.; Franco, D.; et al. Giant Tumefactive Perivascular Space: Advanced Fusion MR Imaging and Tractography Study—A Case Report and a Systematic Review. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillevin, R.; Herpe, G.; Verdier, M.; Guillevin, C. Low-grade gliomas: The challenges of imaging. Diagnostic and Interventional Imaging 2014, 95, 957–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrán de la Gala, D.; Casagranda, S.; Mathon, B.; Mandonnet, E.; Nichelli, L. High perilesional T2-FLAIR signal around anterior temporal perivascular spaces: How can fluid suppressed Amide Proton Transfer weighted imaging further comfort the diagnosis. Magnetic Resonance Imaging 2023, 103, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheraya, G.; Bajaj, S.; Sharma, S.; et al. Giant perivascular spaces in brain: case report with a comprehensive literature review. Precision Cancer Medicine 2022, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Narayanasamy, S.; Siddiqui, M.; Ahmad, I. Giant perivascular spaces: utility of MR in differentiation from other cystic lesions of the brain. JBR-BTR 2014, 97, 364–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandonnet, E.; Delattre, J.Y.; Tanguy, M.L.; et al. Continuous growth of mean tumor diameter in a subset of grade II gliomas. Ann. Neurol. 2003, 53, 524–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).