Submitted:

03 June 2025

Posted:

04 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Information Sources

2.4. Search

2.5. Selection of Sources of Evidence

2.6. Data Charting Process

2.7. Data Items

2.8. Critical Appraisal of Individual Sources of Evidence

2.9. Synthesis of Results

3. Results

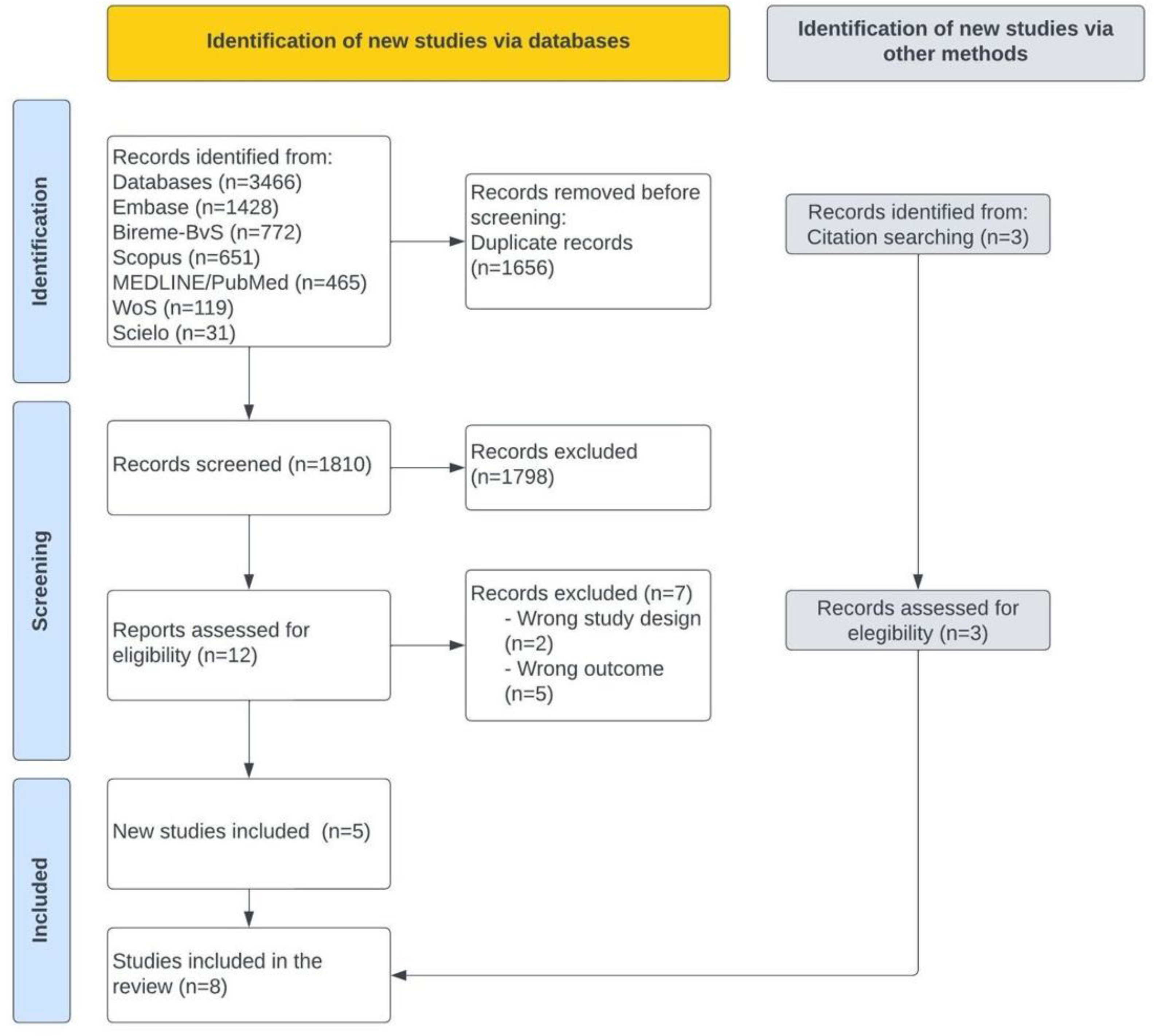

3.1. Selection of Evidence Sources

3.2. Characteristics and Results of the Sources of Evidence

3.3 Population study

3.4. Definitions of Long COVID

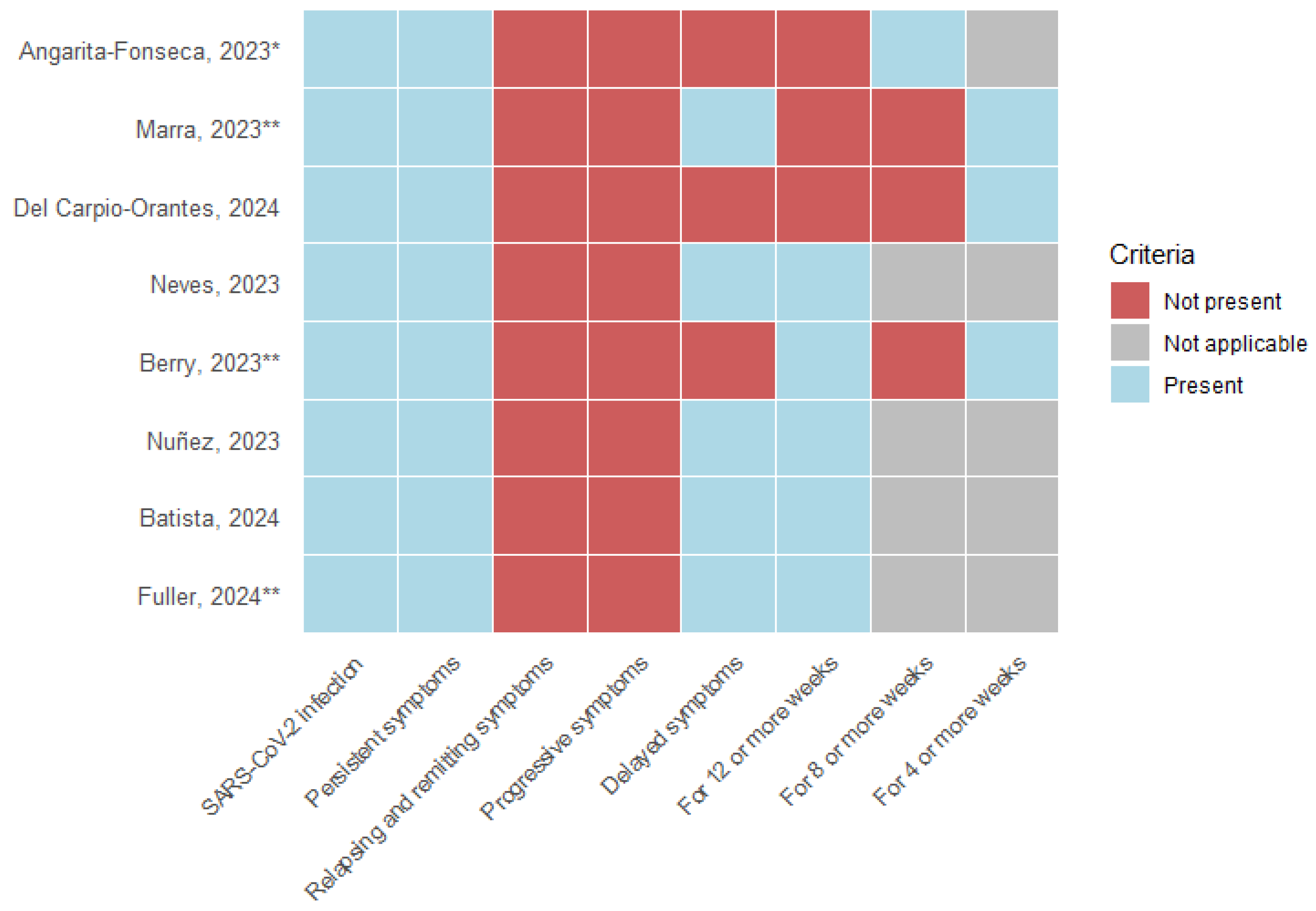

- SARS-CoV-2 infection: All eight articles, as a requirement, include a history of acute COVID-19 infection; 37.5% (3) of the studies describe the need for a positive laboratory test for SARS-CoV-2, and 12.5% (1) include suspicion and confirmation of acute infection.

- Symptoms: The persistence of symptoms from the acute stage was considered by 100% (8) of the studies; remitting and recurrent symptoms and symptom progression were not included in any definition. 62.5% (5) described developing new symptoms after the acute stage of infection.

- Time of presentation: 100% (8) of the studies describe a specific time of permanence of symptomatology following acute infection. 50% (4) consider 12 weeks or more, 12.5% (1) describe 8 weeks or more, and 37.5% (3) use 4 weeks or more as a defining criterion.

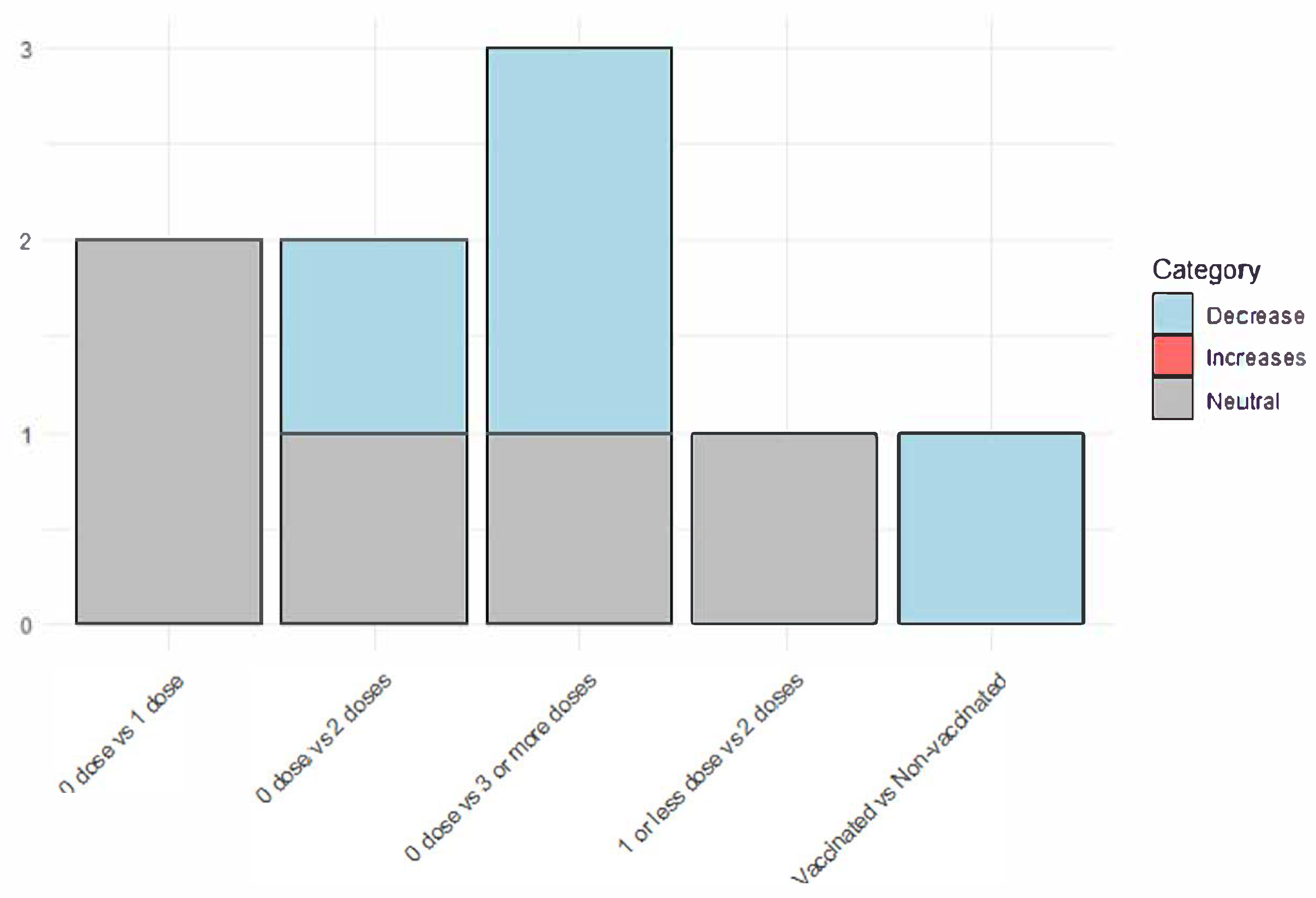

3.5. Vaccination Status

3.6. Reducing the Incidence of Long COVID

3.7. The severity of Symptoms Related to Long COVID

3.8. Duration of Long COVID Symptoms

4. Discussion

4.1. What is Already Known About This Topic

4.2. Main Findings

4.3. Implications for Public Health in the Americas. A call to action

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- CDC. Long COVID or Post-COVID Conditions 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/long-term-effects/index.html#. (accessed on 11 June 2023).

- Ely EW, Brown LM, Fineberg H V. From the National Academy of Medicine Long Covid Defined Medicine Committee on Examining the Working Definition for Long Covid*. N Engl j Med 2024, 18, 391. [Google Scholar]

- Sk Abd Razak R, Ismail A, Abdul Aziz AF, Suddin LS, Azzeri A, Sha’ari NI. Post-COVID syndrome prevalence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodrow M, Carey C, Ziauddeen N, Thomas R, Akrami A, Lutje V, et al. Systematic Review of the Prevalence of Long COVID 2023. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Post COVID-19 condition (Long COVID) 2022. https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/post-covid-19-condition. (accessed on 11 November 2023).

- Angarita-Fonseca A, Torres-Castro R, Benavides-Cordoba V, Chero S, Morales-Satán M, Hernández-López B, et al. Exploring long COVID condition in Latin America: Its impact on patients’ activities and associated healthcare use. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023, 10, 1168628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez I, Gillard J, Fragoso-Saavedra S, Feyaerts D, Islas-Weinstein L, Gallegos-Guzmán AA, et al. Longitudinal clinical phenotyping of post COVID condition in Mexican adults recovering from severe COVID-19: a prospective cohort study. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023, 10, 1236702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Moreno CA, Pineda J, Bareño A, Espitia R, Rengifo P. Long COVID-19 in Latin America: Low prevalence, high resilience or low surveillance and difficulties accessing health care? Travel Med Infect Dis 2023, 51, 102492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peluso MJ, Swank ZN, Goldberg SA, Lu S, Dalhuisen T, Borberg E, et al. Plasma-based antigen persistence in the post-acute phase of COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis 2024, 24, e345–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PAHO/WHO. Summary Situation and COVID-19 Cases and Deaths 2023. https://www.paho.org/en/covid-19-weekly-updates-region-americas. (accessed on 11 November 2023).

- WHO. Statement on the antigen composition of COVID-19 vaccines 2024. https://www.who.int/news/item/26-04-2024-statement-on-the-antigen-composition-of-covid-19-vaccines (accessed ). 30 November.

- Xie Y, Xu E, Bowe B, Al-Aly Z. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes of COVID-19. Nature Medicine 2022, 28, 583–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao P, Liu J, Liu M. Effect of COVID-19 Vaccines on Reducing the Risk of Long COVID in the Real World: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tami A, van der Gun BTF, Wold KI, Vincenti-González MF, Veloo ACM, Knoester M, et al. The COVID HOME study research protocol: Prospective cohort study of non-hospitalised COVID-19 patients. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0273599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang H, Zang C, Xu Z, Zhang Y, Xu J, Bian J, et al. Data-driven identification of post-acute SARS-CoV-2 infection subphenotypes. Nature Medicine 2022, 29, 226–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018, 169, 467–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano-Sánchez G, Rivadeneira J, Manterola C, Fuenmayor-González L. Immunization as protection against long COVID in the Americas: A scoping review protocol. OSF. [CrossRef]

- Peters MD, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco AC, Khalil H. Chapter 11: Scoping Reviews. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual, 2020.

- Peters MDJ, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Khalil H, Larsen P, Marnie C, et al. Best practice guidance and reporting items for the development of scoping review protocols. JBI Evid Synth 2022, 20, 953–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2016, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marra AR, Sampaio VS, Ozahata MC, Lopes R, Brito AF, Bragatte M, et al. Risk factors for long coronavirus disease 2019 (long COVID) among healthcare personnel, Brazil, 2020–2022. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2023, 44, 1972–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves Amorim CE, Silveira Cazetta G, Pontello Cristelli M, Requião-Moura LR, Rodrigues da Silva E, Pinheiro Vale L, et al. Long COVID Among Kidney Transplant Recipients Appears to Be Attenuated During the Omicron Predominance. Transplantation 2023, 108, 963–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry DSF, Dalhuisen T, Marchena G, Tiemessen I, Geubbels E, Jaspers L. Association between post-infection COVID-19 vaccination and symptom severity of post COVID-19 condition among patients on Bonaire, Caribbean Netherlands: a retrospective cohort study. MedRxiv 2023, 2023-06. [CrossRef]

- Del Carpio-Orantes L, Trelles-Hernández D, García-Méndez S, Sánchez-Díaz JS, Aguilar-Silva A, López-Vargas ER. Clinical-epidemiological characterization of patients with long COVID in Mexico. Gac Med Mex 2024, 160, 144–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista KBC, Fernandez MV, Barberia LG, Silva ET da, Pedi VD, Pontes BMLM, et al. Overview of long COVID in Brazil: a preliminary analysis of a survey to think about health policies. Cad Saude Publica 2024, 40, e00094623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller T, Flores Mamani R, Ferreira Pinto Santos H, Melo Espíndola O, Guaraldo L, Lopes Melo C, et al. Sex, vaccination status, and comorbidities influence long COVID persistence. J Infect Public Health 2024, 17, 102562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe A, Iwagami M, Yasuhara J, Takagi H, Kuno T. Protective effect of COVID-19 vaccination against long COVID syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine 2023, 41, 1783–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Català M, Burn E, Rathod-Mistry T, Kostka K, Yi Man W, Delmestri A, et al. The effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines to prevent long COVID symptoms: staggered cohort study of data from the UK, Spain, and Estonia 2024. [CrossRef]

- Iba A, Hosozawa M, Hori M, Muto Y, Kihara T, Muraki I, et al. Booster vaccination and post COVID-19 condition during the Omicron variant-dominant wave: A large population-based study. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2024. [CrossRef]

- Camporesi A, Morello R, Rocca A La, Zampino G, Vezzulli F, Munblit D, et al. Characteristics and predictors of Long Covid in children: a 3-year prospective cohort study. EClinicalMedicine 2024, 76, 102815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu Q, Zhang B, Tong J, Bailey LC, Bunnell HT, Chen J, et al. Real-world effectiveness and causal mediation study of BNT162b2 on long COVID risks in children and adolescents. EClinicalMedicine 2025, 79, 102962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercadé-Besora N, Li X, Kolde R, Trinh NT, Sanchez-Santos MT, Man WY, et al. The role of COVID-19 vaccines in preventing post-COVID-19 thromboembolic and cardiovascular complications Cardiac risk factors and prevention. Heart 2024, 110, 635–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Lastra N, Rivadeneira-Dueñas J, Fuenmayor-González L, Guayasamín-Tipanta G, Jácome-García M, Otzen T, et al. Safety Profile of Homologous and Heterologous Booster COVID-19 Vaccines in Physicians in Quito-Ecuador: A Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines (Basel) 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Faksova K, Walsh D, Jiang Y, Griffin J, Phillips A, Gentile A, et al. COVID-19 vaccines and adverse events of special interest: A multinational Global Vaccine Data Network (GVDN) cohort study of 99 million vaccinated individuals. Vaccine 2024, 42, 2200–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaamika H, Muralidas D, Elumalai K. Review of adverse events associated with COVID-19 vaccines, highlighting their frequencies and reported cases. J Taibah Univ Med Sci 2023, 18, 1646–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author, year | Country | Design | Number of participants | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex n, (%) | Age, years | |||

| Angarita-Fonseca, 20236 | Latin-America | Cross-sectional study | Men: 840 (34.1); Women:1,626 (65.9) |

Mean (SD): 39.5 (53.3) |

| Berry, 202323 | Bonaire | Retrospective cohort study | Men: 10 (21.2); Women:37 (78.8) |

Median (range): 47 (14 - 89) |

| Marra, 202321 | Brazil | Case-control study | Men: 1,950 (27.6); Women: 5,101 (72.4) |

Mean (SD): General: 37.5 (NR) Cases: 38.1 (8.7); Controls: 37.2 (9.0) |

| Neves, 202322 | Brazil | Prospective cohort study | Men: 338 (56.1); Women: 264 (43.9) |

Mean (SD): 51 (12) |

| Nuñez, 20237 | Mexico | Prospective cohort study | Men: 126 (65.6); Women: 66 (34.4) |

Median (range): 53 (45 - 64) |

| Batista, 202425 | Brazil | Cross-sectional study | Men: 59 (11.9); Women: 437 (88.1) |

NR |

| Del Carpio-Orantes, 202424 | Mexico | Cross-sectional study | Men: 65 (32,0); Women: 138 (68,0%) |

Mean (SD): 41.8 (11.3) |

| Fuller, 202426 | Brazil | Prospective cohort study | Men: 88 (31.8); Women: 188 (68.2) |

Median (range): 45 (18 - 88) |

| Author, year | “Fully vaccinated” status | Vaccine type | Long-COVID definition | Efficacy measures | Conclusions | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angarita-Fonseca, 20236 | Two doses | NR | Individuals with a history of probable or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, usually 3 months from the onset of COVID-19 with symptoms that last for at least 2 months and cannot be explained by an alternative diagnosis. | Outcome: Risk of development of LCC. Multivariable logistic regression.

|

Fully vaccinated patients were less likely to have LCC compared with unvaccinated or partially vaccinated subjects. | The design of the study allows the occurrence of the different bias. Data collection (electronic survey) and the non-probabilistic sampling, decrease the methodological quality of the study, the effect size, and the potential generalization of results. |

| Berry, 202323 | At least one dose of the Pfizer vaccine at least 8 weeks after SARS-CoV-2 infection | mRNA: 36, Unvaccinated: 11 |

Individuals with a laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 positive test result, for whom at least one symptom self-attributed to the experienced SARS-CoV-2 infection lasted longer than four weeks. | Outcome: Self-reported change in symptom severity. Multiple covariate adjusted linear regression model. Regression coefficients and 95% CI:

|

Vaccination wassignificantly associated with reduced severity of heart palpitations. | Small sample size; residual confounding may exist due to unmeasured confounding variables; the collection of data outcome data at one point in time, at different intervals since infection (and vaccination, for those applicable limited the comparison of severity scores of Long-COVID symptoms at multiple moments after initial infection at an individual level; Authors reported a linear regression using cathegorical variables to report the effect measures. |

| Marra, 202321 | Analysis were performed whether 1,2,3, or 4 doses were administered. | Inactivated virus= 3,259; Viral vector= 3,255; mRNA=148 |

Signs and symptoms that developed during or following a SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR confirmed infection, continued for >4 weeks, and could not explained by an alternative diagnosis. | Outcome: Risk of development of long COVID. Logistic Regression multivariable analysis.

|

Four doses of COVID-19 vaccines is associated with a lower probability of develop Long-COVID. | As the study was performed only in Healthcare personnel with positive COVID-19 laboratory results, some infected individuals with no laboratory confirmed results may be lost. Also, information bias could be present. |

| Neves, 202322 | Two doses | Homologous inactivated whole-virion vaccine: 189 (36%); Homologous mRNA vaccine: 24 (5%); Homologous viral-vector vaccine:96 (19%); Heterologous inactivated + mRNA: 86 (17%); Heterologous inactivated + viral vector: 44 (9%); Heterologous mRNA + viral vector: 68 (13%); Other heterologous regimens: 5 (1%) |

Physical complaints newly developed during or after the acute phase, persisting for >12 weeks, and not explained by an alternative diagnosis. | Complete vaccination schedule and the risk of Long COVID. HR: 0.89; 95% CI: 0.57–1.41 |

Complete vaccination schedule was not statistically significant with the risk of develop Long-COVID | A relatively modest participation rate, Also, notable qualitative disparities emerged between survey responders and nonresponders, especially regarding the vaccination rates and the acute-phase symptoms |

| Nuñez, 20237 | At least one dose of any SARS-CoV-2 vaccine at least 14 days before the date on which symptoms of acute infection began | NR | Patients experiencing any symptoms not present before acute COVID-19 onset, and that persisted for longer than 90 days after acute COVID-19 onset. | Outcome: probability to experience a shorter time to PCC resolution. HR: 3.16; 95%CI 1.21-8.26 |

Prior SARS-CoV-2 vaccination and acute COVID-19 symptom were associated with a shorter time to Long-COVID resolution. | Study power/sample size calculations were not performed given the explorative nature of this study and the lack of reliable data on PCC prevalence when it was designed. |

| Batista, 202425 | NR | NR | Symptoms that remain or appear for the first time within three months of SARS-CoV-2 infection. | NR± | The occurrence of prolonged COVID was higher among those who were unvaccinated compared with those who received COVID-19 vaccine. | The sampling method used. The survey was published on social networks, which may have limited its representation of the Brazilian population. Self-selection bias. |

| Del Carpio-Orantes, 202424 | One dose or more | NR | Persistence of COVID-19 symptoms four weeks after the acute episode. |

|

In the present analysis, no risk association was found with the history of vaccination. | The design of the study does not permit to establish proper associations, and the low number of participants. |

| Fuller, 202426 | Two or more doses | NR | Symptoms that began within three months of the positive SARS-CoV-2 test. | Outcome: Persistence of Long COVID in not fully vaccinated people. HR: 1·96, 95 % CI: 1·03–3·7 |

There was a significant association between the persistence of Long-COVID over time with not being fully vaccinated. | The fact that was a single center study with a small sample size. The frequency of comorbidities was high among participants, which may restrict the generalizability of our findings to healthier populations. Furthermore, since the analysis was conducted during the Omicron period, there were no participants who remained uninfected with COVID-19. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).