1. Introduction

Understanding the molecular mechanism of disease is not merely about identifying genes that contribute, but also describing the proteins they give rise to—particularly those with direct association to pathological conditions. The main functional units of biology are proteins, and a variety of factors, including their involvement in molecular pathways, post-translational modifications, subcellular localisation, and interaction networks, frequently determine how relevant proteins are to disease processes. Importantly, expert-curated annotations and quantitative measures like UniProt annotation scores, which represent the breadth and accuracy of the available experimental evidence, support confidence in these associations [

1]. Researchers are looking for integrated views that combine functional annotation, disease relevance, and annotation quality in a single, structured output as high-throughput experimental data continues to grow. For instance, prioritizing drug targets or identifying diagnostic biomarkers often starts with such curated protein-level insights [

2,

3].

The data, however, is scattered throughout a multitude of domain-specific portals, from general repositories like UniProtKB and GeneCards to disease-focused resources like DisGeNET [

4] or CTD[

5], and are frequently displayed in formats that are difficult for automated systems to find or query. For researchers hoping to perform systems-level analysis or develop predictive models based on protein function and disease linkage, navigating this diverse landscape continues to be a crucial bottleneck. To address this need, a researcher might pose a natural language query such as:

I want to find proteins that are associated with diseases and have specific functional annotations and UniProt annotation scores

This query exemplifies the increasingly nuanced demands of biomedical researchers seeking integrative, context-rich protein information. Rather than issuing basic keyword-based searches, users aim to assemble datasets filtered by biological function, disease relevance, and curated confidence metrics such as UniProt annotation scores. Satisfying such queries requires the synthesis of protein-disease associations—often curated in disease-specific portals—with pathway or domain-level annotations extracted from ontologies like Gene Ontology or Reactome, alongside quality indicators derived from UniProt records. However, these resources are rarely unified. Relevant data is scattered across multiple specialized repositories, each with distinct schemas, access modalities, and ranking conventions. Navigating this landscape entails not only identifying relevant repositories, but also interacting with dynamic search forms, interpreting annotation schemas, and validating score thresholds defined across heterogeneous scoring systems. The result is a workflow that is both cognitively and operationally burdensome—requiring domain expertise, familiarity with each portal’s interface, and manual integration of partial results. In the absence of machine-readable access pathways, this fragmentation impedes reproducible data discovery and limits the broader utility of protein annotation in translational research contexts.

Despite the existence of several well-established registries such as FAIRsharing [

6] , NAR [

7], Re3Data [

8], DataCite Commons [

9], Zenodo [

10], Dryad,[

11] FigShare [

12], OpenAIRE [

13] and others designed to help researchers discover scientific datasets, the process of locating and programmatically accessing relevant data resources remains remarkably difficult. The widespread adoption of the FAIR principles was intended to improve the usability of scientific data. However, in practice, adoption has been uneven and has fallen short of enabling seamless, automated access to datasets required by modern computational research tools [

6].

A substantial portion of structured scientific data remains buried behind dynamic, interactive web interfaces. These interfaces, often comprising HTML forms, JavaScript – generated tables, cascading dropdowns, and multi-step filtering options, are part of what is commonly referred to as the deep web or hidden web [

14]. This content is inherently resistant to indexing by traditional web crawlers and remains invisible to standard search mechanisms. Even when such resources are listed in registries like FAIRsharing, they are typically represented only by high-level documentation or homepage URLs. Accessing the actual data often requires users to perform a sequence of actions – navigate a search interface, input parameters, interpret results from dynamically rendered tables, and manually download relevant files.

This manual, site-specific process presents a critical obstacle to intelligent systems that aim to support automated scientific discovery. Tools such as machine learning pipelines, semantic query engines, and data integration frameworks cannot easily traverse these interfaces or extract structured results without prior knowledge of how each portal operates. Currently, there is no unified, machine-readable protocol for describing how to interact with such interfaces – how to submit forms, what inputs are required, how to parse returned tables, or how to download filtered results. As a result, the vast troves of scientific data locked behind deep web forms remain largely inaccessible to automated workflows, weakening the practical realization of FAIR’s Accessibility and Reusability dimensions.

To bridge this gap, it is not sufficient to improve crawling technologies or rely solely on metadata registries. What is needed is a standardized, machine-executable protocol for modeling deep web interactions. Such a protocol must be domain-agnostic, interpretable by intelligent agents, and capable of abstracting complex human-facing interfaces into structured, repeatable access paths. These paths should be indexable, reusable, and composable within broader data discovery pipelines.

While emerging large language models (LLMs) such as GPT-4, LLaMA, and PaLM have demonstrated promising capabilities in interpreting web content, inferring form semantics, and generating structured representations from natural language or HTML inputs [

15,

16], their outputs alone lack consistency without an underlying framework to structure and validate them. LLMs can recognize that a form requires a gene symbol and species identifier or predict where results will appear – but they require a consistent formalism to encode such behaviors in a way that downstream systems can reliably interpret and execute.

This is where the Deep Web Communication Protocol (DWCP) becomes essential. DWCP offers a standardized specification to describe the semantics of deep web access: how to interact with forms, what inputs to provide, what outputs to expect, and how to extract them. LLMs serve as powerful engines to populate DWCP specifications from unstructured inputs, but DWCP itself ensures operational integrity and reusability.

By coupling the interpretive power of LLMs with a structured, interoperable access protocol, we move closer to a new paradigm of machine-actionable scientific data discovery. Systems built on this foundation can autonomously access, query, and retrieve data from deep web interfaces across disciplines – enabling scalable, intelligent workflows that support real-time hypothesis testing, including those that seek to identify elusive genetic contributors to cardiovascular disease and other complex traits.

1.1. Our Approach

To address the longstanding challenge of interacting with deep web scientific data in a consistent, scalable, and machine-readable manner, we present FAIRFind – a novel system that transforms static metadata entries into executable data access workflows. Being one of the most comprehensive and popular registries, FAIRFind extends the utility of FAIRsharing by embedding operational semantics into their metadata, thereby enabling real-time, automated data retrieval across heterogeneous repositories.

FAIRFind integrates multiple components into a cohesive pipeline: (i) a deep web crawler that autonomously discovers HTML forms, filters, tables, and dynamic content; (ii) a structural parser that analyzes the layout and behavior of user-facing elements; and (iii) a language model-powered interpreter that infers the semantic intent of web interfaces. These are complemented by a semantic retrieval engine that enables users to issue natural language queries and receive structured, source-resolved responses without manual interaction.

At the core of FAIRFind is the Deep Web Communication Protocol (DWCP)—a standardized and declarative framework for encoding interactive web access pathways. DWCP formalizes how to submit queries to a web interface, what input parameters are required, what behaviors are expected (e.g., button clicks, dropdown selections), and how to extract returned content (e.g., tabular data, file links, embedded elements). Each DWCP instance encapsulates a complete, reproducible access path that is both machine-executable and interpretable by intelligent agents.

FAIRFind is designed not to replace but to complement and enhance platforms like FAIRsharing. While FAIRsharing provides curated metadata about scientific standards, policies, and databases, it does not operationalize the data access process. FAIRFind bridges this critical gap by generating actionable workflows that make listed datasets directly accessible for integration into computational pipelines, machine learning applications, and automated discovery tools. In doing so, FAIRFind transforms static registry entries into live, interoperable endpoints that can power next-generation scientific inquiry.

1.2. Contributions

This work makes the following key contributions:

We introduce DWCP, a structured and generalizable specification that encodes deep web access workflows in a machine-readable format, enabling automated and reproducible data retrieval across diverse web interfaces.

We develop FAIRFind, an end-to-end system that autonomously discovers, semantically interprets, and executes deep web access paths associated with FAIRsharing-listed resources, making previously inaccessible data programmatically available.

We implement a semantic query engine that matches natural language user queries to DWCP-encoded workflows, enabling users to retrieve scientific data without knowing the structure of the underlying database or interface.

We design and conduct a comprehensive evaluation across multiple language models, query types, and interface complexities and demonstrate high precision and success rates in structured data extraction and access workflow execution.

1.3. Impact and Vision

FAIRFind redefines the role of scientific data registries by bridging the gap between metadata and operational access. It enables a future in which intelligent agents, researchers, and applications can issue complex, intent-driven queries and receive structured, interpretable results without navigating multilayered user interfaces or relying on manual intervention. By operationalizing the deep web, FAIRFind lays the groundwork for scalable, autonomous data discovery across the scientific landscape.

2. Related Works

Early research into the deep web established that a substantial portion of scientific data is only accessible through interactive interfaces such as web forms. Traditional crawlers could not reach this content, prompting development of hidden web crawlers. Raghavan and Garcia-Molina [

14] formalized this challenge, and follow-up efforts like Form-Focused Crawler [

17] and ACHE [

18] refined the ability to locate and classify searchable forms. Google’s deep web crawl [

19] scaled this effort by precomputing form submissions at scale. Despite these advancements, many systems struggled with forms, complex input semantics, and interaction patterns that required domain-specific handling.

Recent work has demonstrated the potential of large language models (LLMs) to generalize across web layouts and automate form interactions. Studies by Chen

et al. [

20] and Narang

et al. [

21] show that LLMs can infer the structure and semantics of form fields from HTML, enabling automation without site-specific tuning. Stafeev

et al. [

22] extended this idea to full web workflows, using GPT-4 to navigate and extract content from complex applications. These approaches indicate the feasibility of using LLMs for robust, domain-agnostic web automation.

The FAIR principles [

23] have driven the adoption of machine-readable metadata and standardized protocols. OAI-PMH and FAIR Data Points [

24] allow structured metadata exposure, but do not support dynamic interaction with data portals. Google Dataset Search [

25] and Schema.org annotations have improved findability, yet leave accessibility gaps when content resides behind forms. FAIRFind’s DWCP protocol complements these efforts by offering an interaction layer for structured data hidden in deep web interfaces. Registries like re3data [

8] and FAIRsharing [

6] catalog databases and standards, aiding discovery and compliance with FAIR practices. However, these registries point to repositories rather than facilitating direct data access. FAIRFind builds upon their metadata by enabling live interaction with the listed sources, turning passive descriptions into operational endpoints.

Tools like Google Dataset Search [

25] and DataMed [

26] enable keyword or ontology-backed discovery of datasets. Yet, they operate on pre-harvested metadata and cannot reach live, form-mediated content. FAIRFind addresses this limitation by combining LLM-driven query understanding with real-time deep web interaction, expanding the reach of semantic search into dynamic, previously unindexable resources. FAIRFind is positioned against this backdrop of semantic search tools. It shares the goal of enabling intuitive discovery of scientific data, but approaches it from an automation and interoperability angle. Rather than building another centralized index of metadata, FAIRFind uses an LLM to interpret a user’s natural language query and execute a distributed search across many data sources in real time. In doing so, it can tap into sources that are not part of any pre-aggregated index. This addresses a gap left by existing semantic search engines: the inability to reach into the deep web live. For instance, if a particular environmental dataset is only queryable via a form on a national data portal (and not indexed elsewhere), Google Dataset Search or DataMed would likely not find the granular data. FAIRFind could directly query that portal’s form through DWCP and extract the relevant results, guided by the user’s question and the LLM’s understanding.

Semantic search tools have improved the findability of datasets by unifying metadata and enabling natural language queries, but they often operate on a closed corpus of pre-harvested information. FAIRFind advances the state of the art by opening up the live deep web of scientific data: it combines the semantic intelligence of LLMs with a systematic protocol to engage with data portals, thereby linking the user’s query to actual data in repositories that were previously siloed or hidden behind search forms. This capability fills a crucial void in the FAIR ecosystem and extends the reach of FAIR principles into the deep web realm.

3. The DWCP Protocol: Deep Web Communication for FAIR Indexing

Even with growing efforts to organize scientific data, much of it stays hidden from automated systems. That’s because deep web interfaces often use forms, dynamic content, and client-side rendering. This makes it really tough to achieve the FAIR principles, particularly when it comes to Findability and Accessibility. That’s why we’re introducing DWCP (Deep Web Communication Protocol), a new general-purpose communication protocol. It is designed to standardize how we extract and represent structured data from web interfaces, making it much easier to index and query.

DWCP acts as a middleware layer between human-readable web pages and machine-actionable data representations. It essentially helps automate finding, interacting with, and understanding all that content usually buried behind online forms and interactive elements. The protocol operates over modular components and provides structured messages that allow AI systems to reason about and extract data across heterogeneous data access methods.

3.1. Formal Specification of DWCP

The Deep Web Communication Protocol enables communication between indexing agents and web services that host deep web resources. DWCP is defined as a message-passing protocol that uses common network transports. Resource discovery, defining access patterns, and coordinating data retrieval are the three main tasks that the protocol makes easier.

Let represent the set of all agents seeking to access deep web resources, and represent the set of services hosting such resources. DWCP establishes a communication channel where is the set of standardized protocol messages. Each DWCP message contains a version identifier, message type, and payload. The protocol operates through request-response cycles where agents initiate communication and services respond with structured metadata about their accessible resources.

3.2. Message Structure and Data Model

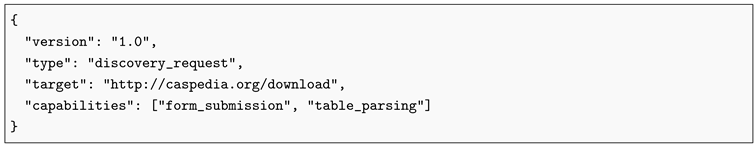

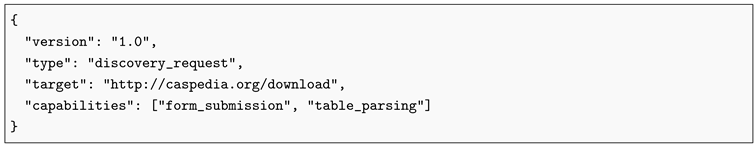

DWCP messages follow a consistent JSON structure. Each message includes mandatory fields for protocol version and message type. The payload varies according to the specific operation being performed. Resource discovery represents the fundamental DWCP operation. A target URL receives a discovery request from an agent. The request outlines the desired resource types and the agent’s capabilities. In response, services provide structured explanations of the resources that are available, along with data schemas and access patterns.

Consider a discovery request

sent to service

s:

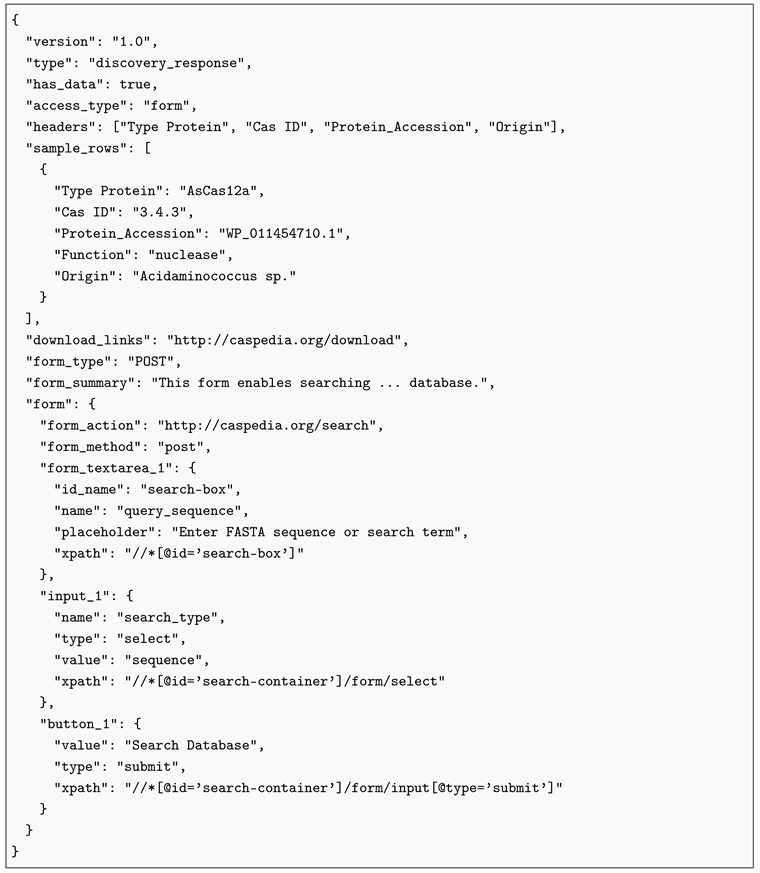

The corresponding response

describes available resources:

DWCP uses the access-type field to define three basic access patterns. Interactive interfaces that need parameter submission via HTML forms are described by form-based patterns. Resources that are available as static HTML tables are specified by direct table access patterns (“html-table”). Datasets accessible as downloadable files via direct links are identified by file download patterns (“ftp”).

All of the metadata required for automated interaction is included in each access pattern. Interaction specifications, such as XPath selectors for DOM elements, parameter names and types, and submission endpoints, are provided by the form field. While sample-rows offer specific instances of data that can be retrieved, the headers field outlines the anticipated data structure.

3.3. Protocol Operations

DWCP supports stateless communication between agents and services. Agents start by contacting possible deep web resources with discovery requests. In response, services provide organised summaries of the datasets they make available. Then, using the given specifications, agents create customised access requests.

The protocol uses thorough access path descriptions to guarantee reproducible interactions. A service gives agents all the information they need to submit requests and parse responses when it describes a form-based resource. This covers response parsing instructions, submission endpoints, and parameter specifications. DWCP-specific error codes are added to standard HTTP conventions for error handling. Services use structured error responses to show authentication failures, rate limiting constraints, and parameter validation errors.

4. System Logic

In this section, we’ll detail our architecture’s key modules and explain how they work together to enable FAIR-compliant data discovery. Our system enhances FAIRsharing’s data accessibility by creating an automated pipeline. This pipeline can discover, extract, and semantically query deep web content.

4.1. Architecture Overview

We propose a modular system organized into four main components:

where

H denotes the metadata harvester which gathers structured information from FAIRsharing records.

C is the deep web crawler and form analyzer that explores web interfaces to locate data entry points,

I refers to the data extractor and vector indexer that processes retrieved content into structured representations. These three components collectively form the data indexing pipeline. The fourth component,

R is the semantic query and retrieval engine which enables natural language access to the indexed data.

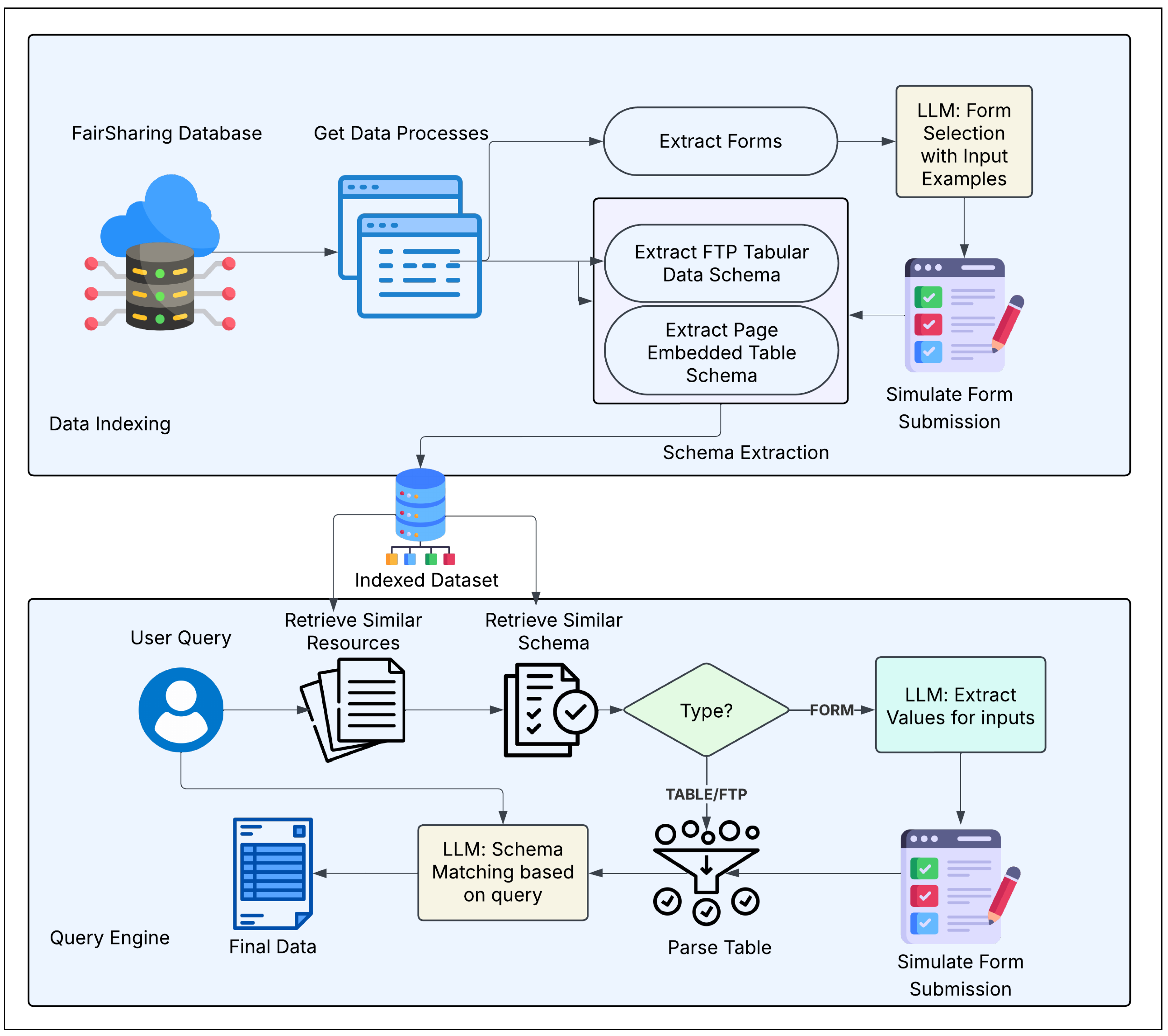

The interaction flow among these components is shown in

Figure 1. Each module feeds into the next, forming a fully automated pipeline. The architecture is designed to be both scalable and extensible which allows integration with other scientific registries beyond FAIRsharing.

4.2. Metadata Harvesting

We begin by collecting metadata from the FAIRsharing registry, which lists 2,349 curated scientific databases spanning diverse domains. FAIRsharing provides structured records that describe data policies, access methods, and process pages for each entry. From these records, FAIRFind extracts descriptive fields such as database name, summary, creation year, homepage, and the set of associated data access links.

Each access link is analyzed to determine its type—distinguishing between user-facing web interfaces, downloadable file endpoints, and FTP repositories. We exclude entries with REST API endpoints, as programmatic APIs are outside the scope of this study. During processing, we encountered several records whose access links failed to load or returned invalid content. These were likely due to outdated or deprecated process pages and were excluded from further processing.

After filtering and validation, our final dataset includes 924 FAIRsharing entries with 1,800 data-containing web pages. These pages form the basis of the downstream crawling, access abstraction, and semantic indexing pipeline.

4.3. Form Discovery and Interaction Modeling

On the web, a large portion of scientific data remains hidden behind interactive interfaces like forms, filters, and custom input panels that need human intervention to access the underlying datasets. It can be difficult to index, query, or reuse these interfaces programmatically because they are usually created for user experience rather than automated systems.

Finding these interactive forms, comprehending how they function, and creating a reusable representation of the interaction pathway are the main goals of this pipeline stage. We call this an access path abstraction. The process unfolds through four core stages: detecting interactive inputs, semantic filtering, form simulation, and constructing access paths.

4.3.1. Detecting Interactive Inputs

The system starts by loading a specific webpage, making sure that all client-side content is completely rendered. It then performs a thorough scan to find possible locations for data entry. This comprises text fields, dropdown menus, input fields, form elements, and submit buttons. After a form is detected, it is parsed into a structured candidate block that includes all related input fields, the action endpoint, and the HTTP method (GET or POST). The name, type, and XPath expression of each field are annotated. An initial collection of interaction candidates is the end result, but many of these are later filtered as irrelevant, such as newsletter sign-ups or login forms.

4.3.2. Semantic Filtering and Selection

The system analyses and filters the previously identified candidates using a language model to make sure we concentrate on relevant forms. The forms on the page that are most likely to produce organised scientific results are given priority by this model. Additionally, it generates a brief summary in natural language that explains the specifics and intent of each form. This synopsis is essential for providing retrieval systems’ search space with context. In addition to classification, the model generates inputs intended to yield reliable results by inferring sample values. This semantic reasoning is driven by a structured prompt that combines the HTML context with parsed form metadata. The output at this stage provides the selected form’s identifier, its semantic description, and a set of sample inputs.

4.3.3. Simulating Form Interaction

After a target form is selected and populated with sample inputs, the system simulates its submission. Forms demand full DOM-level interaction. To achieve this, the system uses the previously recorded XPath references to pinpoint relevant input fields and submit buttons. A headless browser then programmatically fills out and submits the form. This interaction handles JavaScript-based redirects, AJAX updates, and other dynamic elements common in modern web environments. The final rendered HTML from this submission is then captured for subsequent data extraction.

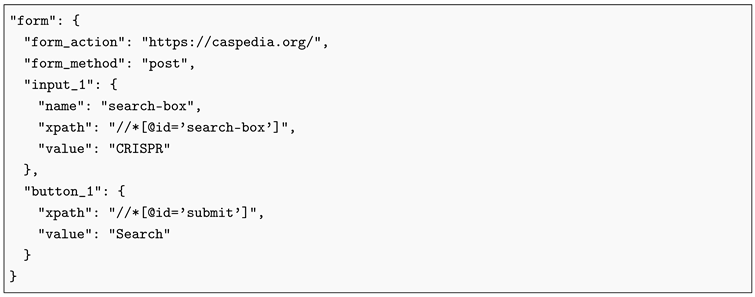

4.3.4. Constructing Access Path Abstractions

To ensure that form interactions can be reliably repeated and interpreted by other systems, the system records each successful submission as a structured access path abstraction. This object includes the HTTP method used (GET or POST), the full action URL of the form, the list of fields and sample values submitted, and metadata such as XPath expressions or DOM attributes for fields and buttons.

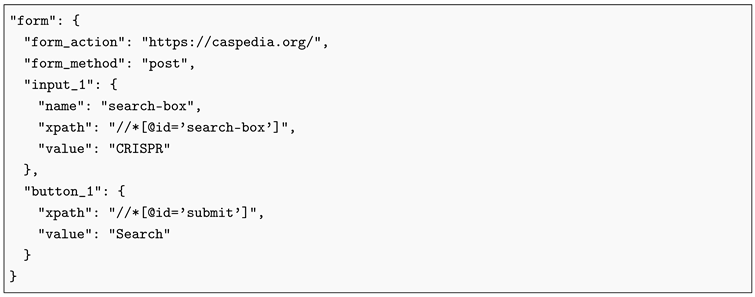

An example of this access path abstraction, as stored in the DWCP output message, is shown below:

This structure enables downstream agents to re-execute the interaction using only the information encoded in the DWCP message.

4.4. Data Extraction and Access Normalization

Data extraction from the resultant web page comes next, once form interactions are reproduced or direct links are resolved. This stage creates a normalised schema from the visual or code-level representation of a dataset so preparing it for indexing, search, and reuse.

This module performs three main tasks: identifying data structures, extracting headers and sample rows, and packaging the information into a DWCP-compliant output format. It is designed to handle both static content, like pre-rendered HTML tables, and dynamic content, such as tables loaded via JavaScript or rendered after a form submission.

4.4.1. Table Detection and Parsing

The rendered page is parsed using a dual strategy. If HTML-table elements are present, a rule-based parser is applied to extract column headers and a small number of representative data rows. We use a fallback language model-based HTML interpreter for more complicated pages whereby tables are dynamically rendered or styled using various containers. Even in cases when traditional tags are absent, this LLM-assisted method heuristically detects tabular areas and extracts structured content.

For each discovered table

, we construct a representation:

where

is a list of column names and

contains 2 representative entries sufficient for embedding and preview. Each extracted data unit is wrapped into a DWCP-compliant output object, regardless of how it was retrieved, whether through form submission, direct table access, or file download.

4.4.2. Access Normalization Across Types

The extraction logic adapts based on the type of access mechanism.

Data is extracted from the page rendered after simulating a completed form submission. The DWCP output includes the full form object, and the access-type is set to “form”.

Pages containing static tables are parsed directly without interaction. The resulting output includes headers and sample-rows, and the access-type is set to “html-table”.

When data is provided via downloadable links (e.g., CSV, XLS), the system downloads and parses the file. The first row is treated as headers, and the next two rows are extracted as samples.

Regardless of access-type, each output is then passed to the embedding and indexing module.

This step finalizes the conversion of human-facing interfaces into machine-actionable, FAIR-aligned data entries. In the following stage, these records are vectorized and stored in a retrieval-ready format to support semantic search and ranking.

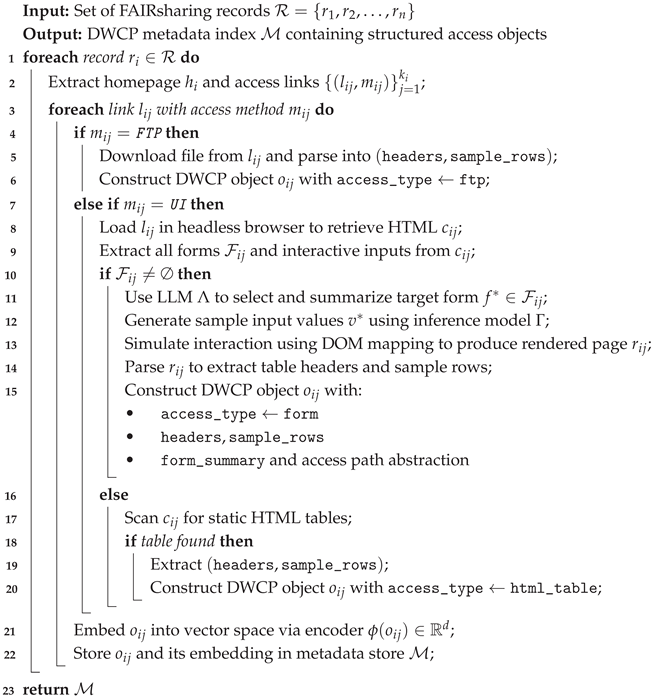

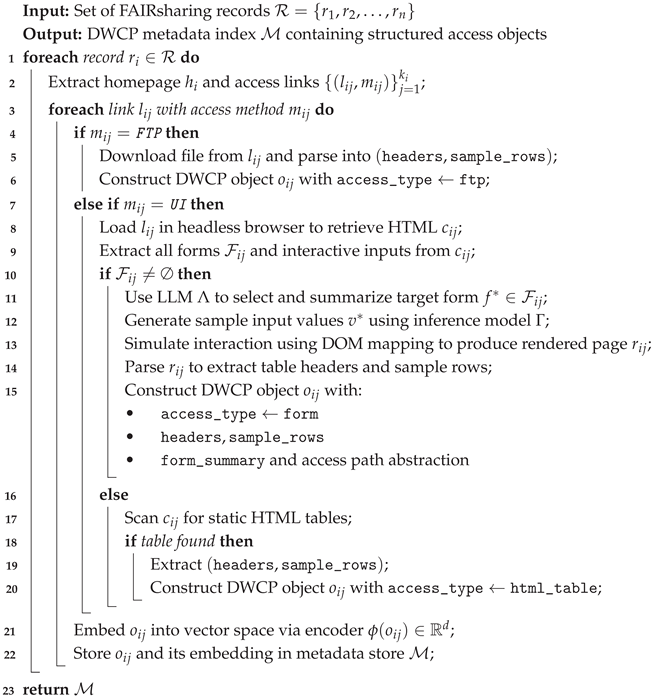

Algorithm 1 describes the complete indexing pipeline used to convert FAIRsharing records and their associated access links into structured, queryable DWCP metadata entries. The process is designed to be modular, extensible, and compatible with a wide variety of data delivery mechanisms found throughout the scientific deep web. The algorithm operates over a set of records , where each record contains a homepage and one or more access links. For each access link , the pipeline applies a branching logic depending on its declared access method: FTP or User Interface (UI) as annotated in FAIRSharing entries. This distinction is essential, as each access mode requires a distinct handling strategy.

For links labeled with the

FTP access method, the system directly downloads and parses the associated file. A rule-based parser extracts the header and a small sample of rows. This extracted information provides sufficient semantic content to populate a DWCP object containing representative metadata and example data. The most common and complex case involves user interface (UI) access links, which point to dynamic web pages requiring full rendering and interaction. First, the target page is loaded, ensuring that all dynamic content is rendered and the full Document Object Model (DOM) is available for analysis. Once the page is fully rendered, the system extracts all form elements and free-standing input controls, parsing them into structured candidates for potential interaction.

|

Algorithm 1: DWCP-Based Deep Web Indexing Pipeline |

|

These candidates are then assessed by a locally hosted open source language model, which chooses the form that is most likely to produce structured data and provides a brief overview of its intended purpose. A realistic simulation of user interaction is made possible by the model’s inference of realistic input values for each field based on the chosen form. The system simulates the entire interaction as a user would by using XPath-based automation to fill out and submit the form within the browser context.

The HTML page returned, whether via GET or POST, is parsed for structured content. If a valid table is found, the headers and sample rows are extracted accordingly. In cases where no usable form is detected, the system scans for static HTML tables as a fallback. If found, it still constructs a DWCP object with access-type as html-table.

Once the structured data is extracted, it is wrapped into a DWCP-compliant JSON object. This object includes all necessary metadata, such as headers, sample rows, access method, and any form-specific access path information. The goal is to ensure that the interaction is reproducible and the resource is programmatically accessible. Each DWCP object is then embedded into a high-dimensional semantic vector space via an encoder function . The resulting embedding is stored in the metadata index alongside its corresponding DWCP object, supporting future retrieval based on similarity.

4.5. Semantic Query Engine

The goal of the query engine is to allow users to retrieve structured scientific data using natural language queries, without requiring knowledge of the exact source database, access method, or form structure. Our approach uses a multi-stage retrieval and reasoning system built on top of the DWCP index. The system combines semantic search over embedded metadata with LLM-based interpretation and form execution. It consists of the following core stages: (1) Site-level ranking, (2) Access path retrieval, (3) Dynamic interaction, and (4) Structured output rendering.

4.5.1. Vectorized Document Indexing

To support fast and flexible retrieval, each DWCP record whether representing a form interaction, downloadable file, or static table—is split into two types of documents:

These documents are preprocessed into fixed-length text chunks using a sliding window mechanism. Each chunk is embedded using a SentenceTransformer model, mxbai-embed-large-v1 and stored in a ChromaDB vector store. This model was selected based on its strong performance-to-size tradeoff, as ranked on the MTEB leaderboard [

27].

This dual representation of documents supports hierarchical retrieval from relevant websites down to specific access pathways.

4.5.2. Stage-One Retrieval: Site Ranking

Given a user query

q, the system first searches over HTML content to rank the most relevant websites. For each site, we retrieve top-

k matching content chunks

and compute the average distance to the query embedding:

where dist denotes cosine distance. This yields a ranked list

of FAIRsharing sites most likely to contain relevant data.

4.5.3. Stage-Two Retrieval: Access Path Matching

After selecting the top-ranked site

, the engine restricts its search to schema-level documents under that site. DWCP metadata documents

are retrieved using:

Each retrieved schema document corresponds to a page-url and a JSON-formatted access-path.

4.5.4. Dynamic Interaction and Data Extraction

Once the most relevant DWCP object is retrieved, the system parses its access-path field and simulates the corresponding interaction based on the declared access-type. If the type is form, the system uses input values inferred from the user’s query to populate the fields and then submits the form via browser automation. For html table access, the system loads the target page and extracts the table contents using either Selenium or an LLM-assisted parser capable of handling dynamically rendered or non-standard table structures. When the access type is ftp, the system directly downloads the linked file and parses it to retrieve structured data from its contents.

If the interaction involves a form, an LLM infers realistic values based on field names and the semantics of the query. These values are programmatically injected into the form before submission.

4.5.5. Output Rendering

The final output of the FAIRFind system is returned as one or more structured data tables in tabular format. This design ensures that responses to user queries yield usable, well-organized datasets—rather than ambiguous or overly general descriptions—making them immediately suitable for downstream analysis, integration, or reuse in FAIR-aligned research workflows.

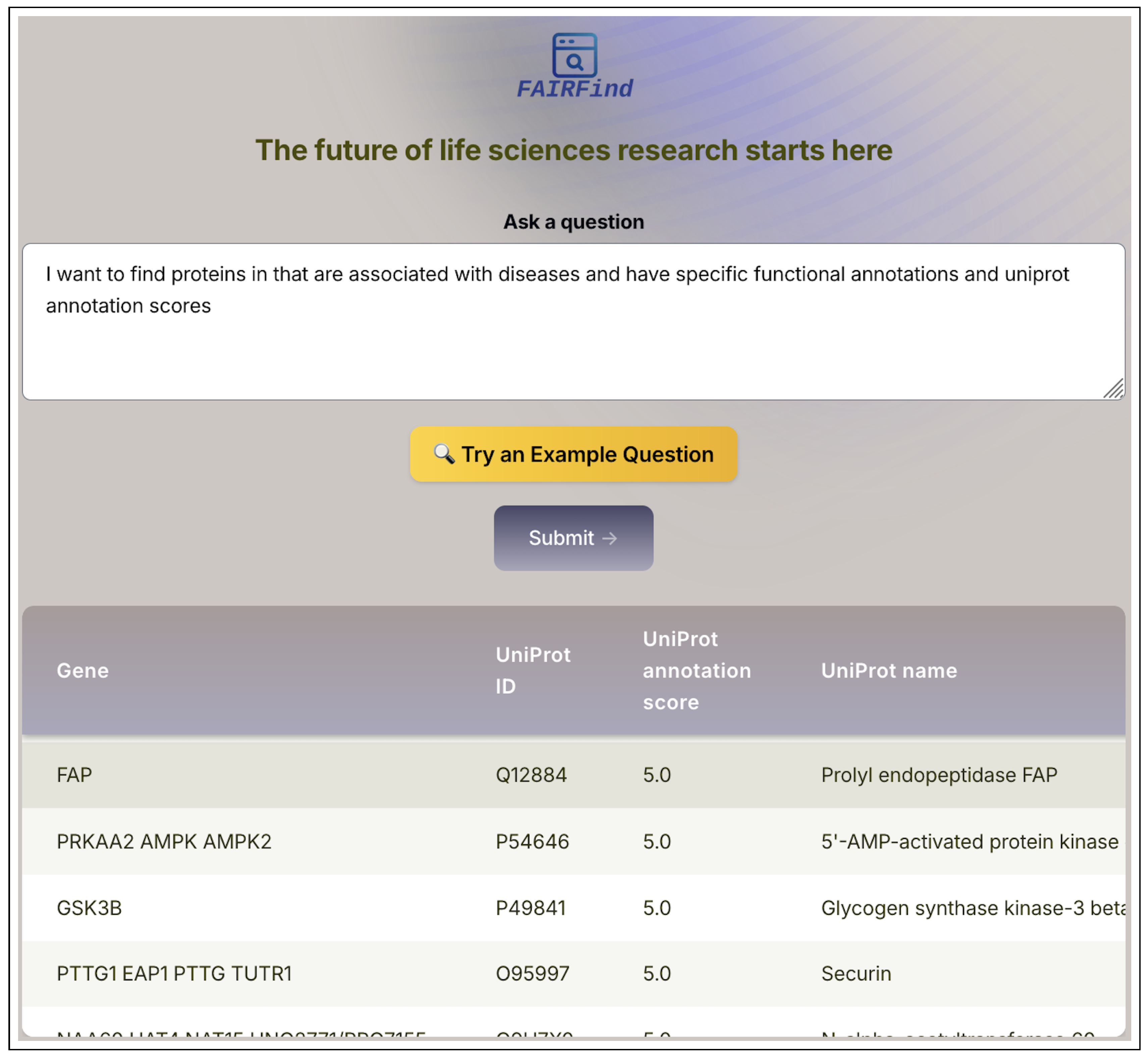

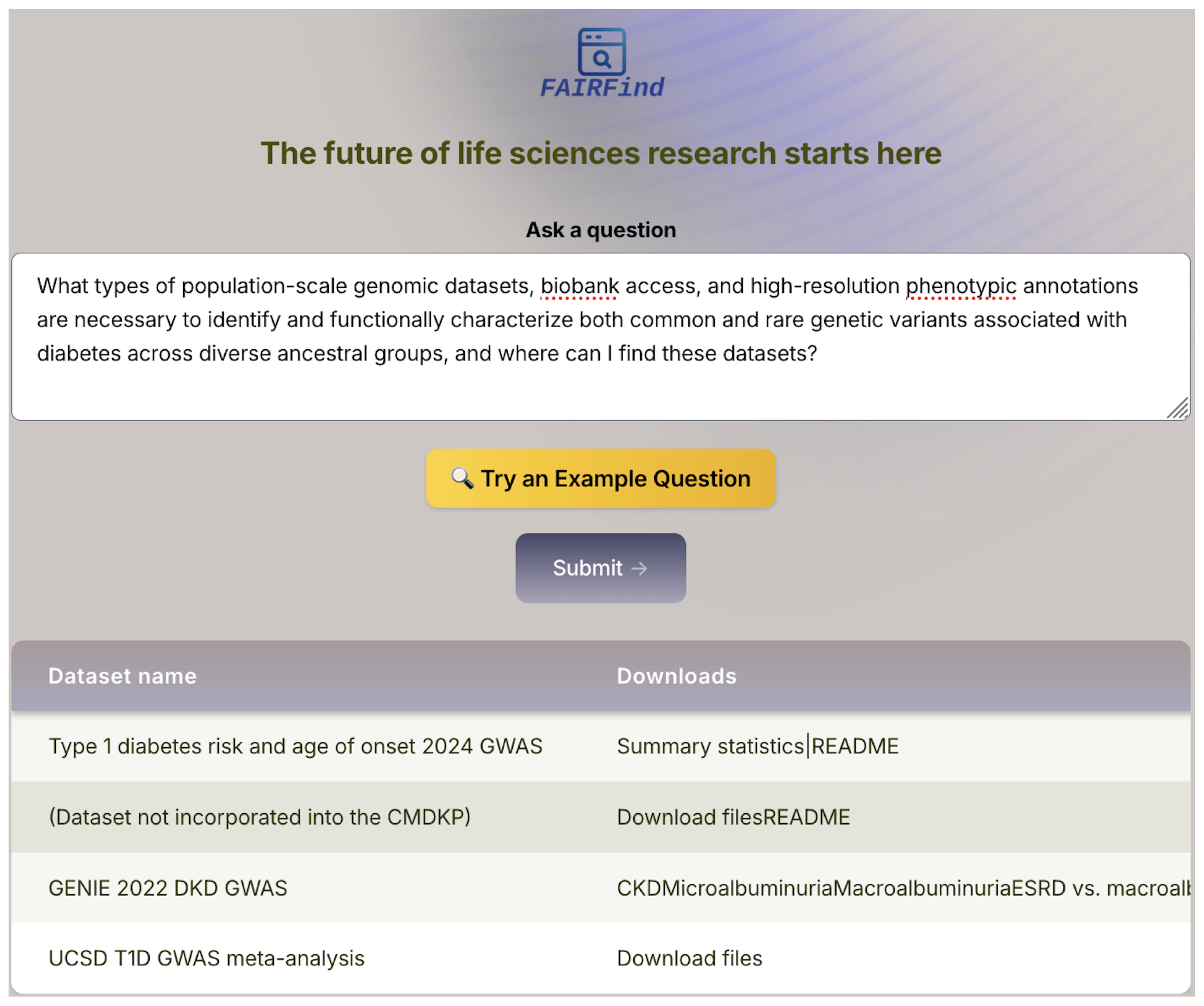

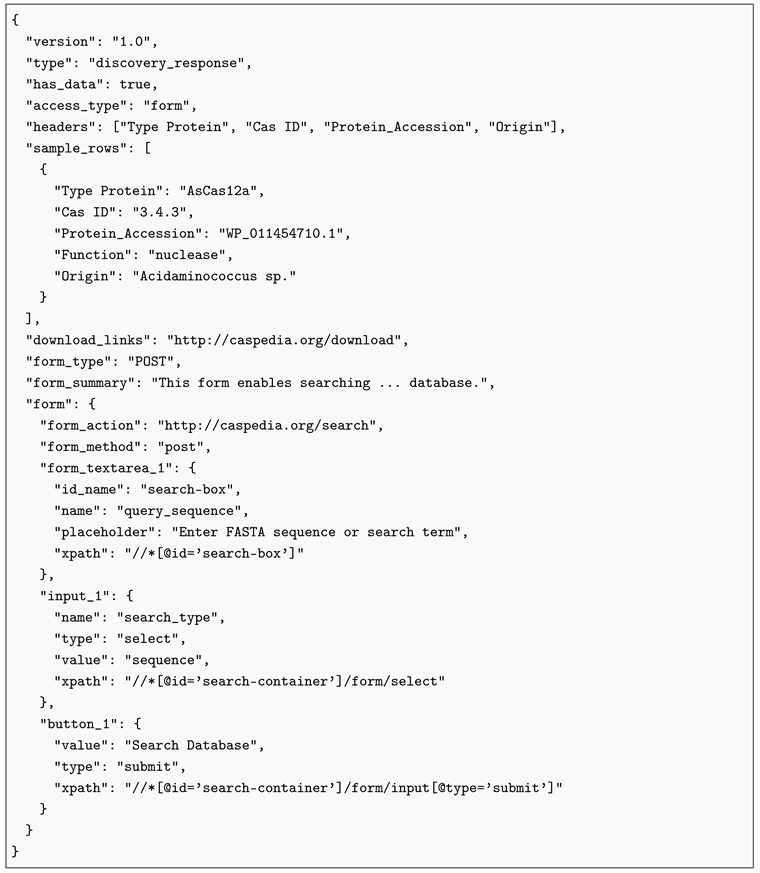

Figure 2 displays the semantic query interface of FAIRFind. In this example, we use the query

Q where a user is requesting proteins that are associated with diseases and annotated with specific UniProt functional information and confidence scores. The system parses this intent and executes structured retrieval across deep web–indexed sources. The output presents a curated table listing protein entries, including gene symbols, UniProt identifiers, annotation scores, and full protein names. This example highlights FAIRFind’s ability to transform unstructured user questions into structured outputs, bridging the gap between complex biomedical queries and actionable dataset retrieval.

4.6. Prompt Engineering and Output Structuring

FAIRFind integrates large language models (LLMs) into key stages of its indexing pipeline, where conventional rule-based methods are either too strict, inefficient or unreliable. To ensure consistency, interpretability, and robustness, we adopt structured prompt engineering techniques paired with constrained output schemas. A context-aware prompt that is dynamically created according to the properties of the target web resource directs each LLM invocation. These prompts use FAIRsharing metadata, HTML fragments that have been extracted, and parsed interface elements like field names, form methods, and placeholder text. We enable the model to accurately reason about its purpose, whether it is to identify the most relevant form, summarise access behaviour or generate plausible input values, by customizing the prompt to the structure and semantics of each page. We use a variety of prompting techniques, such as instruction-style prompting and chain-of-thought prompting, to increase reliability across various web layouts [

28,

29].

A key design principle is the use of structured output constraints. All model responses are expected to conform to a predefined JSON schema. This schema defines the required fields, value types, and nesting rules for each component of the output. Structured outputs enable automatic validation, simplify downstream integration into indexing systems, and ensure consistent, interpretable model behavior across diverse queries and data sources.

5. Evaluation Framework

To assess the performance and generalization ability of our system across different access types and language model variants, we construct an evaluation framework centered on real-world FAIRsharing entries. The evaluation focuses not only on retrieval accuracy but also on execution success and system efficiency.

5.1. Benchmark Construction

We begin by sampling a balanced benchmark set of 50 FAIRsharing records, denoted as:

Each data point

is selected to ensure even coverage across the three primary access types supported by DWCP.

For each

, we extract a ground truth tuple:

These serve as reference points for evaluating site ranking, page retrieval, access path identification, and execution success.

To evaluate both precise and abstract language inputs, we generate two types of queries for each :

The full query set is:

Queries are automatically generated using gpt-4o prompted with table headers, form metadata, and page content. This ensures both linguistic diversity and semantic relevance to the dataset.

Table 1 presents simple and complex example queries.

5.2. Evaluation Metrics

Our evaluation framework assesses FAIRFind’s performance along two main dimensions: Exact Match Accuracy and Data Retrieval Success. These collectively measure the system’s ability to navigate, identify, and interact with deep web sources indexed through DWCP representations.

5.2.1. Exact Match Accuracy

This group of metrics captures whether the retrieval pipeline successfully aligns with ground-truth access paths at different levels of resolution. For each natural language query , we compute binary indicators reflecting the correctness of predicted access components.

First, we assess whether the top-ranked site

, as returned by the semantic retrieval system, matches the ground truth site associated with the query. This is formalized as the

Site Match Rate.

Next, we check whether the retrieved schema document points to the correct page url, where the structured data is hosted. The corresponding

Page Match Rate is defined as:

Beyond locating the page, the system must also extract and interpret the correct access pathway. We compute the

Access Path Match Rate based on whether the retrieved DWCP access path block matches the reference in both structure and semantics:

Alongside these binary correctness indicators, we also measure the total time required to resolve each query. The Average Retrieval Time, denoted , includes all steps: semantic site ranking, schema re-ranking, access path processing, and content fetching (including any browser-based interaction or LLM inference). This latency metric provides insight into system responsiveness.

5.2.2. Data Retrieval Success

While exact matches reflect alignment with the ground truth, the practical goal is to return structured, usable data. We therefore define a success criterion—

Success@1—which captures whether the query ultimately produced a valid tabular dataset, regardless of the precise access path. Formally, we say that a query succeeds if the final output

contains valid tabular data, regardless of whether the exact retrieval path followed the ground truth:

This metric effectively reflects system robustness, especially in cases where the system retrieves valuable data even after making heuristic mistakes in site or schema selection. We present mean values for all metrics for each model variant that was evaluated. This includes the average of each binary indicator (site match, page match, access match, and success), the mean query execution time

, and the overall Success@1 rate. These aggregate scores allow for direct comparison of retrieval quality and runtime efficiency across language model backends.

To assess how different large language models influence schema interpretation and query-grounded interaction, we benchmark four open-source models:

LLaMA 3.3 (70B)

Qwen 3

DeepSeek-R1

Gemma

All models are evaluated in their 4-bit quantized form. Each model is tasked with interpreting HTML-based schemas and supporting the following critical operations: selecting and summarizing form elements, generating representative values for form fields, and semantically aligning user queries with access paths. All remaining components of the system—vector-based retrieval, HTML rendering, and execution logic—remain fixed. This design isolates the influence of the language model on accuracy and latency.

5.3. Execution Pipeline

Each user query is processed through a multi-stage pipeline involving semantic retrieval, schema-level access resolution, and structured data extraction. The end-to-end interaction includes document embedding, site and schema re-ranking, form interaction (if applicable), and output parsing. The overall procedure is summarized in Algorithm 2. This function is applied to every query

and generates a tuple containing evaluation metrics and runtime, which is subsequently logged for further analysis. This process is executed for all queries in the benchmark set. The resulting logs form the basis for performance comparisons across language models, access types, and query complexities.

|

Algorithm 2:Evaluation Pipeline for Semantic Query Execution |

|

Input: Natural language query q, ground truth

Output: Evaluation result and response time

- 1

Compute embedding using the sentence encoder - 2

Retrieve top site candidates based on vector similarity over HTML chunks - 3

Select top-ranked site and retrieve all schema-level DWCP records

- 4

Re-rank by computing for each schema

- 5

Select best schema document and extract

- 6

Compare with to evaluate path accuracy - 7

Simulate access interaction using process_access_path

- 8

If successful, extract resulting tabular data - 9

Record query execution time

- 10

Compute and return: - 11

- 12

return ,

|

6. Results and Analysis

We evaluate FAIRFind on a curated benchmark of 50 scientific data sources linked from FAIRsharing, using both simple and complex queries. The results are organized by the two primary evaluation axes defined earlier.

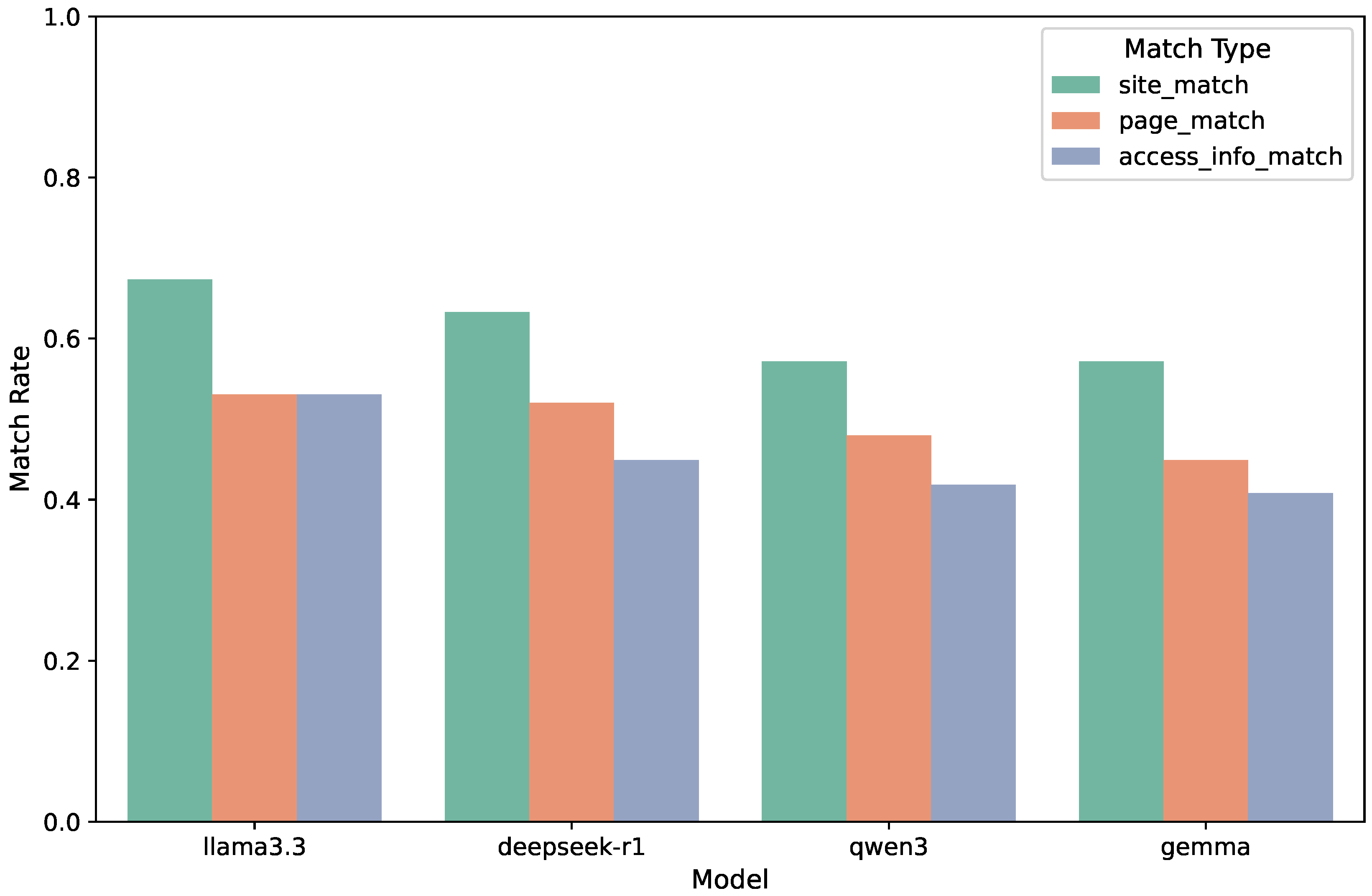

6.1. Exact Match Performance

Figure 3 presents the exact match performance across four open source language models. We evaluate three types of retrieval correctness—

site match rate,

page match rate, and

access path match rate—each capturing a distinct level of alignment between user intent and system prediction in the deep web indexing pipeline.

Among the models evaluated, LLaMA 3.3 achieves the highest site match rate at 0.673, reflecting its superior ability to identify the correct scientific repository based on the semantics of the input query. DeepSeek-R1 follows closely with a match rate of 0.633, while Qwen3 and Gemma both score 0.571. These results suggest that while all models demonstrate a reasonable understanding of query-to-domain alignment, LLaMA 3.3 benefits from stronger grounding in scientific terminology and document structures.

In the task of identifying the correct data interface page, LLaMA 3.3 again leads with a page match rate of 0.531. DeepSeek-R1 and Qwen3 perform comparably, with scores of 0.520 and 0.480, respectively. Gemma, however, lags behind at 0.449. This drop relative to site match rates indicates that even when the correct domain is identified, locating the exact interactive or data-bearing page presents a more nuanced challenge for the models.

The most challenging retrieval task turns out to be recovering the exact DWCP access-path block, which includes the interaction method and related metadata. Here, LLaMA 3.3 continues to outperform others, with a schema match rate of 0.531. DeepSeek-R1 follows at 0.449, Qwen3 at 0.418, and Gemma at 0.408. The decline in scores from site to access-level accuracy illustrates the increasing difficulty of aligning user queries with detailed, structured access pathways.

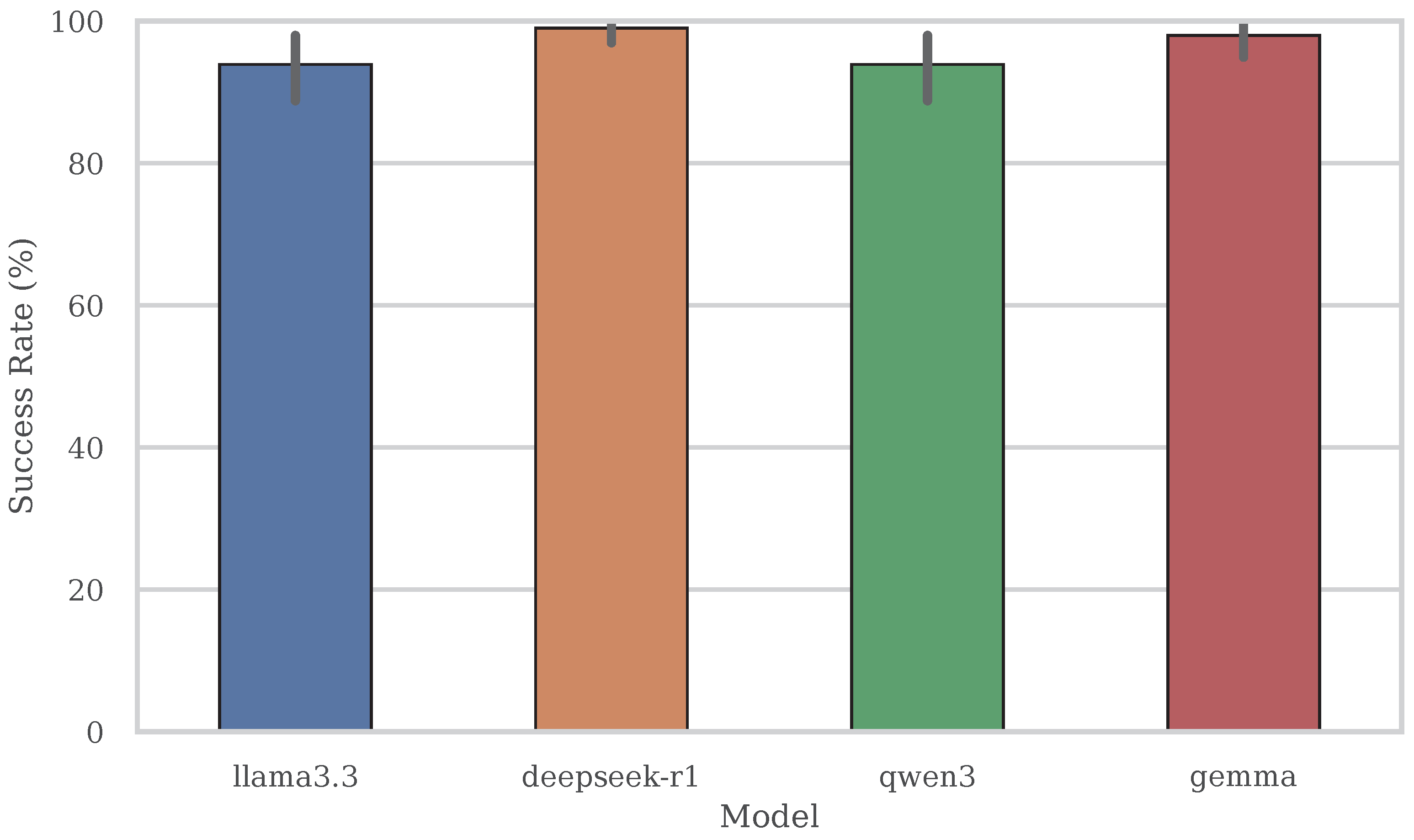

6.2. Data Retrieval Performance

Figure 4 reports the Success@1 rate for each evaluated model. This metric captures the percentage of queries for which the system successfully retrieved a valid structured dataset

from the predicted access path. Unlike exact match metrics, Success@1 reflects the end-to-end robustness of the system—combining semantic retrieval accuracy, form simulation reliability, and extraction logic effectiveness.

Across the board, models exhibit high retrieval success rates, demonstrating the system’s robustness in executing diverse deep web interactions. DeepSeek-R1 achieves the highest Success@1 rate at 98.98%, successfully returning structured data for 97 out of 98 test queries. This performance validates its strong balance between fast execution and dependable access path resolution, even when schema-level precision varies.

Gemma closely follows with a 97.96% success rate. Despite modest lag in page and schema match accuracy, it generalizes well across form and table interfaces and exhibits minimal failure cases. Both LLaMA 3.3 and Qwen3 yield a success rate of 93.88%. LLaMA’s lower score is primarily attributed to occasional delays and form execution failures, which offset its strong retrieval precision. Meanwhile, Qwen3’s fragility in handling complex forms—particularly value inference and field alignment—contributes to its few retrieval failures, despite an otherwise efficient runtime profile.

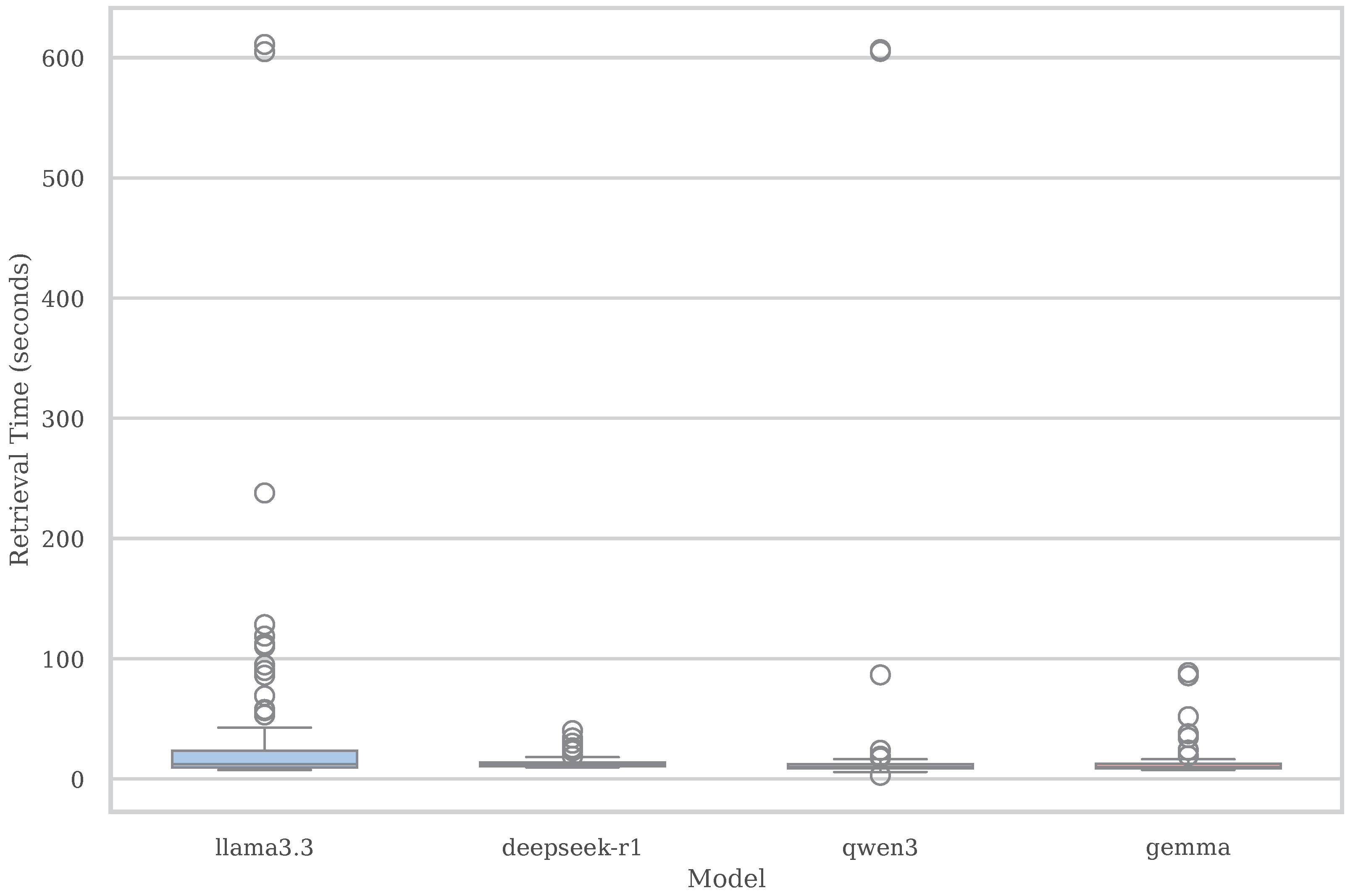

6.3. Retrieval Time and Efficiency

Figure 5 presents the distribution of end-to-end retrieval time per query across all evaluated models. This measurement encompasses the complete execution pipeline, including vector-based semantic search, schema resolution, form population (if applicable), page loading, and structured data extraction. As such, it offers a realistic assessment of each model’s responsiveness in real-world deployment conditions.

Among the evaluated models, LLaMA 3.3 incurs the highest average retrieval latency, with a mean of 39.3 seconds per query. This elevated duration stems from both its large model size (70B parameters) and the longer generation completions typically produced during form interpretation and sample input inference. Moreover, LLaMA displays high variability in runtime, with several queries taking over 100 seconds and some extreme outliers exceeding 600 seconds.

In contrast, DeepSeek-R1 demonstrates the most efficient and stable behavior, averaging only 13.6 seconds per query—almost three times faster than LLaMA 3.3. It also features a tighter variance range, making it particularly suitable for latency-sensitive applications. Gemma and Qwen3 show intermediate behavior. Gemma maintains low and consistent latency around 13.2 seconds per query, while Qwen3 averages 29.7 seconds but occasionally experiences delays above 90 seconds, indicating higher variance. Notably, both DeepSeek-R1 and Gemma exhibit robustness across different access types, showing minimal timing degradation in more complex scenarios. On the other hand, LLaMA 3.3’s latency is less predictable, reflecting occasional spikes due to its increased prompt length, form parsing load, and runtime memory footprint.

These results indicate a trade-off between latency stability and semantic accuracy. While LLaMA provides high retrieval accuracy, its processing overhead may be a limitation in contexts that require fast and consistent responses. DeepSeek-R1 presents a viable alternative, offering a more balanced combination of speed, reliability, and competitive retrieval performance.

Table 2 provides a detailed breakdown of model performance across simple, complex, and overall queries. This perspective emphasises how query complexity affects system behaviour, whereas earlier figures concentrated on aggregate trends. As anticipated, simple queries that closely match the names of schema fields typically yield better results for models, with higher page and schema match rates. The biggest performance difference between simple and complex inputs is seen in LLaMA 3.3, especially in schema match accuracy, highlighting its strength in well-structured but abstraction-sensitive queries. DeepSeek-R1 and Gemma, on the other hand, show more consistent performance across query types, indicating greater resilience to changes in linguistic specificity. These patterns further support DeepSeek-R1’s balance between speed and accuracy, and indicate areas where form interpretation and semantic grounding can be improved, especially for abstract queries.

7. Discussion

This work presents FAIRFind, a system that augments the FAIRsharing registry by enabling automated indexing and access to deep web datasets. While FAIRsharing provides structured metadata about scientific standards and databases, it does not expose or enable access to the actual contents of those databases. FAIRFind addresses this gap by discovering, simulating, and structuring access to data hidden behind forms, tables, and file links—reinforcing the FAIR principles, particularly Findability and Accessibility, within the FAIRsharing infrastructure itself.

The system operates consistently across a variety of access types, as shown by our experimental results. LLaMA 3.3 performs the best on exact match metrics—site, page, and access path—indicating strong semantic alignment between query and schema. However, it is the slowest model by a wide margin, with many queries taking over 30 seconds and some exceeding several minutes (

Figure 5). Its slow response is due to larger model size and long completions, especially during access path reasoning.

DeepSeek-R1 offers the best overall trade-off. It achieves the highest structured data retrieval success rate (

Figure 4), performs competitively on exact match metrics, and has the lowest average retrieval time. However, it underperforms slightly in schema alignment, especially when compared to LLaMA 3.3. This suggests that DeepSeek is able to find alternative valid paths when the exact schema is missed. Its speed and consistency make it a strong candidate for default use, particularly when users prioritize responsiveness.

Although Qwen3 exhibits a reasonable degree of accuracy, its form execution is inconsistent. Its slightly lower success rate and lower schema match can be explained by this. Gemma, on the other hand, executes tasks quickly and consistently, but it struggles with precise matching, especially when it comes to determining the right schema. When reasoning is needed to infer intent, it struggles, but it does well on simpler queries. Although both models show promise, there is still a need for improved alignment between execution robustness and schema understanding.

Complex queries resulted in lower site, page, and schema match rates across all models. This is to be expected since complex queries lack explicit schema terms and instead rely on implicit reasoning. It is simpler to match the indexed DWCP records with simple queries that directly reference form fields or column names. Even for complex queries, success rates are still high, demonstrating that the system can still produce useful data even in the absence of precise alignment.

Beyond retrieval accuracy, FAIRFind advances a broader vision of transforming static metadata registries into interactive, executable infrastructures. At the core of this transformation is the DWCP protocol, which formalizes each access point—whether a form, table, or downloadable file—as a structured object containing metadata, access type, form fields, and XPath-based selectors. AI agents can now programmatically interact with deep web content that was previously unavailable to automated systems owing to this abstraction. FAIRFind transforms FAIRsharing into a living interface by using natural language queries to generate executable, reusable access paths, where references become entry points to real data. The foundation for scalable, repeatable data discovery across scientific domains is laid by DWCP, which transforms intricate, user-driven interactions into programmable workflows. It also ensures that once a page is indexed, it becomes not just findable, but operational—ready to be re-queried, The integration of semantic retrieval, form understanding, and automated execution supports a scalable and reproducible model for machine-actionable scientific discovery.

Despite its strengths, the system has several limitations. DOM interaction based on XPath is still brittle, particularly when dynamic layout changes are present. Authentication, CAPTCHA resolution, and multi-step form workflows—all of which are typical in more secure data portals—are not supported by the current implementation. Furthermore, this version does not support REST or GraphQL API-based access because these interfaces frequently call for pre-specified schemas, tokens, or rate-limiting logic that cannot be automatically deduced. Additionally, table extraction is limited to well-formed layouts and may not work on designs that are heavily styled or obfuscated.

While FAIRFind successfully transforms natural language queries into deep web interactions and retrieves structured outputs, certain use cases expose limitations of the current single-hop execution model. As illustrated in

Figure 6, a user querying for population-scale genomic datasets and phenotypic annotations related to diabetics receives a table of relevant dataset names and references. This output correctly reflects the structure of the data as presented by the source portal. However, accessing the actual data files or corresponding metadata often requires additional navigation steps—clicking through summary pages, interacting with secondary forms, or resolving dynamically generated URLs. These multi-hop workflows are not yet automated in the current system. Supporting such chained interactions—akin to task-level execution over web interfaces—remains a key area for future extension. Enabling FAIRFind to follow multi-step access paths would improve its completeness and usability for complex biomedical queries where data is deeply nested or fragmented across pages.

In future work, we aim to mitigate these challenges through the integration of schema-aware input generation, robust multi-step interaction planning, and support for authenticated sessions. In order to facilitate the wider deployment of DWCP-based agents across a greater corpus of deep web resources, we also intend to expand FAIRFind to other data-rich scientific registries.

As FAIRFind evolves, we recognize that many developers and advanced users may seek not just data, but the capability to embed access mechanisms directly into their computational workflows. In scenarios where automated pipelines need to compute high-level summaries, perform cross-database integration, or support interactive assistants, the primary requirement is not data per se, but the code needed to retrieve and manipulate it. In future versions of FAIRFind, we plan to support an exportable format where users can retrieve ready-to-integrate code segments corresponding to DWCP entries. These code modules will encapsulate the form submission logic, result parsing routines, and access metadata necessary to port specific data views into downstream applications. This functionality will further promote reuse, interoperability, and transparency, while extending FAIRFind’s role from a discovery interface to a programmable access layer.

8. Conclusions

This work presents FAIRFind, a novel system that operationalizes the FAIR principles within the FAIRsharing ecosystem by transforming static metadata into executable, machine-actionable access workflows. While FAIRsharing offers curated metadata about data standards and repositories, it does not expose the actual datasets hidden behind dynamic, interactive web interfaces. FAIRFind bridges this critical gap by autonomously crawling data portals, identifying and interpreting forms and tables using large language models, and constructing structured, reproducible workflows for deep web access.

The Deep Web Communication Protocol (DWCP), a formal, model-agnostic specification that abstracts user interface interactions into standardised machine-readable instructions, is the foundation of this capability. DWCP transforms deep web interactions from inaccessible, user-specific processes into structured, interpretable format that intelligent systems can comprehend and carry out by encoding input schemas, submission logic, and result extraction strategies. This greatly advances the Accessibility and Reusability aspects of FAIR by converting web-based data access from a manual bottleneck into a reusable computational asset.

With over 90% success in structured data retrieval, our evaluation shows that FAIRFind is robust across a variety of language models, query modalities, and interface complexities. Specifically, DeepSeek-R1 showed strong performance in terms of speed and reliability, while LLaMA 3.3 provided higher precision with increased latency. This highlights the architecture’s ability to accommodate different performance requirements. The system’s support for both formal schema-driven queries and natural language input also reflects its applicability to a variety of scientific workflows.

In addition to its technical contributions, FAIRFind reflects a broader shift in scientific data infrastructure from passive registries toward more interactive and intelligent access frameworks. By supporting automated, real-time interactions with datasets that were previously accessible only through manual deep web queries, FAIRFind enhances the ability of both AI systems and researchers to retrieve relevant data. This approach may help facilitate larger-scale integration, hypothesis testing, and data-driven exploration.

In the future, FAIRFind provides a framework for extending access to other data modalities, such as non-HTML data services, private APIs, and authenticated sources. Beyond FAIRsharing, it can easily be extended to other domain-specific registries, promoting a federated ecosystem of scientific knowledge that is queryable, interoperable, and accessible by AI. By uniting protocol-based abstraction, large language model reasoning, and scalable indexing, FAIRFind takes a decisive step toward realizing the full promise of the FAIR principles, not merely as guidelines, but as operational reality.

Acknowledgments

This Research was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health IDeA grant P20GM103408, the National Science Foundation CSSI grant OAC 2410668, and the US Department of Energy grant DE-0011014.

System Availability

The FAIRFind system is currently in its testing phase, ahead of its official release. Once publicly available, you’ll be able to access it at

http://dblab.nkn.uidaho.edu/fairfind/. To power our local LLM models, we’re using two NVIDIA Ada 600 GPUs, each equipped with 48GB of RAM, alongside an AMD Ryzen Threadripper PRO 5955WX CPU and 256GB of system RAM. To ensure continuous improvement, we’ve also included a system support and comment submission option where you can report bugs, system failures, and offer suggestions.

References

- Consortium, U. UniProt: a worldwide hub of protein knowledge. Nucleic acids research 2019, 47, D506–D515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, N.L.; Anderson, N.G. The human plasma proteome: history, character, and diagnostic prospects. Molecular & cellular proteomics 2002, 1, 845–867. [Google Scholar]

- Keshava Prasad, T.; Goel, R.; Kandasamy, K.; Keerthikumar, S.; Kumar, S.; Mathivanan, S.; Telikicherla, D.; Raju, R.; Shafreen, B.; Venugopal, A.; et al. Human protein reference database—2009 update. Nucleic acids research 2009, 37, D767–D772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piñero, J.; Bravo, À.; Queralt-Rosinach, N.; Gutiérrez-Sacristán, A.; Deu-Pons, J.; Centeno, E.; García-García, J.; Sanz, F.; Furlong, L.I. DisGeNET: a comprehensive platform integrating information on human disease-associated genes and variants. Nucleic acids research 2016, gkw943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, A.P.; Wiegers, T.C.; Johnson, R.J.; Sciaky, D.; Wiegers, J.; Mattingly, C.J. Comparative toxicogenomics database (CTD): update 2023. Nucleic acids research 2023, 51, D1257–D1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sansone, S.A.; McQuilton, P.; Rocca-Serra, P.; Gonzalez-Beltran, A.; Izzo, M.; Lister, A.L.; Thurston, M.; Community, F. FAIRsharing as a community approach to standards, repositories and policies. Nature biotechnology 2019, 37, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigden, D.J.; Fernández, X.M. The 27th annual Nucleic Acids Research database issue and molecular biology database collection. Nucleic Acids Research 2020, 48, D1–D8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pampel, H.; Vierkant, P.; Scholze, F.; Bertelmann, R.; Kindling, M.; Klump, J.; Goebelbecker, H.J.; Gundlach, J.; Schirmbacher, P.; Dierolf, U. Making research data repositories visible: the re3data. org registry. PloS one 2013, 8, e78080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson-Garcia, N.; Mongeon, P.; Jeng, W.; Costas, R. DataCite as a novel bibliometric source: Coverage, strengths and limitations. Journal of Informetrics 2017, 11, 841–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenodo. Zenodo - Research. Shared. https://zenodo.org/, 202. Accessed: 2025-04-05.

- Dryad. Dryad - Publish and Preserve Your Data. https://datadryad.org/stash, 2024. Accessed: 2025-04-05.

- Figshare. Figshare - Share your research. https://figshare.com/, 2024. Accessed: 2025-04-05.

- Rettberg, N.; Schmidt, B. OpenAIRE-Building a collaborative Open Access infrastructure for European researchers. LIBER Quarterly: The Journal of the Association of European research libraries 2012, 22, 160–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, S.; Garcia-Molina, H. Crawling the Hidden Web. In Proceedings of the VLDB 2001, Proceedings of 27th International Conference on Very Large Data Bases, September 11-14, 2001, Roma, Italy; Apers, P.M.G.; Atzeni, P.; Ceri, S.; Paraboschi, S.; Ramamohanarao, K.; Snodgrass, R.T., Eds. Morgan Kaufmann, 2001, pp. 129–138.

- Touvron, H.; Lavril, T.; Izacard, G.; Martinet, X.; Lachaux, M.A.; Lacroix, T.; Rozière, B.; Goyal, N.; Hambro, E.; Azhar, F.; et al. Llama: Open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.13971 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; Anadkat, S.; et al. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.08774 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa, L.; Freire, J. Searching for Hidden-Web Databases. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Eight International Workshop on the Web & Databases (WebDB 2005), Baltimore, Maryland, USA, Collocated mith ACM SIGMOD/PODS 2005, June 16-17, 2005; Doan, A.; Neven, F.; McCann, R.; Bex, G.J., Eds., 2005, pp. 1–6.

- Barbosa, L.; Freire, J. An adaptive crawler for locating hidden-web entry points. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 16th international conference on World Wide Web, 2007, pp. 441–450.

- Madhavan, J.; Ko, D.; Kot, L.; Ganapathy, V.; Rasmussen, A.; Halevy, A.Y. Google’s Deep Web crawl. Proc. VLDB Endow. 2008, 1, 1241–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.K.; Liu, C.H.; You, S.D. Using Large Language Model to Fill in Web Forms to Support Automated Web Application Testing. Information 2025, 16, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gur, I.; Nachum, O.; Miao, Y.; Safdari, M.; Huang, A.; Chowdhery, A.; Narang, S.; Fiedel, N.; Faust, A. Understanding html with large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.03945 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Stafeev, A.; Recktenwald, T.; De Stefano, G.; Khodayari, S.; Pellegrino, G. YURASCANNER: Leveraging LLMs for Task-driven Web App Scanning. In Proceedings of the The Network and Distributed System Security (NDSS) Symposium. CISPA, 2024.

- Wilkinson, M.D.; Dumontier, M.; Aalbersberg, I.J.; Appleton, G.; Axton, M.; Baak, A.; Blomberg, N.; Boiten, J.W.; da Silva Santos, L.B.; Bourne, P.E.; et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific data 2016, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Sompel, H.; Nelson, M.L.; Lagoze, C.; Warner, S. Resource harvesting within the OAI-PMH framework. D-lib magazine 2004, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brickley, D.; Burgess, M.; Noy, N. Google Dataset Search: Building a search engine for datasets in an open Web ecosystem. In Proceedings of the The world wide web conference; 2019; pp. 1365–1375. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Gururaj, A.E.; Ozyurt, B.; Liu, R.; Soysal, E.; Cohen, T.; Tiryaki, F.; Li, Y.; Zong, N.; Jiang, M.; et al. DataMed–an open source discovery index for finding biomedical datasets. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association 2018, 25, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enevoldsen, K.; Chung, I.; Kerboua, I.; Kardos, M.; Mathur, A.; Stap, D.; Gala, J.; Siblini, W.; Krzemiński, D.; Winata, G.I.; et al. MMTEB: Massive Multilingual Text Embedding Benchmark. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.13595, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Bosma, M.; Zhao, V.Y.; Guu, K.; Yu, A.W.; Lester, B.; Du, N.; Dai, A.M.; Le, Q.V. Finetuned language models are zero-shot learners. arXiv preprint arXiv:2109.01652, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kojima, T.; Gu, S.S.; Reid, M.; Matsuo, Y.; Iwasawa, Y. Large language models are zero-shot reasoners. Advances in neural information processing systems 2022, 35, 22199–22213. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Overview of the system architecture and workflow.

Figure 1.

Overview of the system architecture and workflow.

Figure 2.

FAIRFind: Semantic Query Interface for Deep Web Biomedical Data. The FAIRFind interface allows users to search scientific deep web resources using natural language. It interprets user queries, matches them to appropriate access paths, and returns structured data. In this example, the user requests proteins associated with diseases and annotated with UniProt functional metadata and scores. The interface parses this natural language input and returns a tabular dataset, each annotated with UniProt ID, annotation score, and protein name.

Figure 2.

FAIRFind: Semantic Query Interface for Deep Web Biomedical Data. The FAIRFind interface allows users to search scientific deep web resources using natural language. It interprets user queries, matches them to appropriate access paths, and returns structured data. In this example, the user requests proteins associated with diseases and annotated with UniProt functional metadata and scores. The interface parses this natural language input and returns a tabular dataset, each annotated with UniProt ID, annotation score, and protein name.

Figure 3.

Exact match accuracy of four open-source language models—LLaMA 3.3, DeepSeek-R1, Qwen3, and Gemma—across three retrieval metrics: site match, page match, and access path (schema) match. Each bar represents the proportion of queries for which the system, using the respective model, correctly identified the target repository domain (site), the specific data-containing page (page), and the structured access path required to extract the data (access-info). The results reveal a consistent performance advantage for LLaMA 3.3 across all tasks, especially in more fine-grained retrieval steps.

Figure 3.

Exact match accuracy of four open-source language models—LLaMA 3.3, DeepSeek-R1, Qwen3, and Gemma—across three retrieval metrics: site match, page match, and access path (schema) match. Each bar represents the proportion of queries for which the system, using the respective model, correctly identified the target repository domain (site), the specific data-containing page (page), and the structured access path required to extract the data (access-info). The results reveal a consistent performance advantage for LLaMA 3.3 across all tasks, especially in more fine-grained retrieval steps.

Figure 4.

Structured data retrieval success (Success@1) across four language models, defined as the proportion of queries for which a valid tabular dataset was returned from the predicted access path. This includes all access types—form-based, table-based, and file-based interfaces. DeepSeek-R1 achieves the highest success rate at 98.98%, followed closely by Gemma at 97.96%. LLaMA 3.3 and Qwen3 both report 93.88%, slightly lower due to occasional failures in form execution or schema resolution.

Figure 4.

Structured data retrieval success (Success@1) across four language models, defined as the proportion of queries for which a valid tabular dataset was returned from the predicted access path. This includes all access types—form-based, table-based, and file-based interfaces. DeepSeek-R1 achieves the highest success rate at 98.98%, followed closely by Gemma at 97.96%. LLaMA 3.3 and Qwen3 both report 93.88%, slightly lower due to occasional failures in form execution or schema resolution.

Figure 5.

Distribution of total retrieval time (in seconds) per query across four language model variants: LLaMA 3.3, DeepSeek-R1, Qwen3, and Gemma. Each box plot captures median latency, interquartile range, and long-tail outliers for the full DWCP pipeline, including semantic search, schema matching, and data access simulation. LLaMA 3.3 exhibits the highest average latency and greatest variance, with some queries exceeding 600 seconds, reflecting its heavier generation load and greater form processing overhead. DeepSeek-R1 demonstrates the lowest and most stable response time, averaging 13.6 seconds with minimal outliers.

Figure 5.

Distribution of total retrieval time (in seconds) per query across four language model variants: LLaMA 3.3, DeepSeek-R1, Qwen3, and Gemma. Each box plot captures median latency, interquartile range, and long-tail outliers for the full DWCP pipeline, including semantic search, schema matching, and data access simulation. LLaMA 3.3 exhibits the highest average latency and greatest variance, with some queries exceeding 600 seconds, reflecting its heavier generation load and greater form processing overhead. DeepSeek-R1 demonstrates the lowest and most stable response time, averaging 13.6 seconds with minimal outliers.

Figure 6.

FAIRFind interface responding to a population-scale genomic data query. The system parses a complex natural language question concerning diabetics and retrieves a list of relevant datasets, as indexed in the target data portal. The table shown is extracted from a dynamic web page and includes downloadable GWAS datasets and summaries.

Figure 6.

FAIRFind interface responding to a population-scale genomic data query. The system parses a complex natural language question concerning diabetics and retrieves a list of relevant datasets, as indexed in the target data portal. The table shown is extracted from a dynamic web page and includes downloadable GWAS datasets and summaries.

Table 1.

Examples of simple and complex query pairs used in the benchmark set.

Table 1.

Examples of simple and complex query pairs used in the benchmark set.

| Simple Query |

Complex Query |

| Find entries in the PR2 database where Level is “Alveolata” and Class is “Dinoflagellates” with Version 5.0, focusing on taxonomic groups annotated by experts. |

I am looking for detailed information on proteins with unique dynamic properties, such as those with chameleon subsequences or Dual Personality Fragments, as analyzed through molecular dynamics simulations. Specifically, I want to explore how these proteins interact with other biological molecules and their domain limits. |

| Find samples with Data Type as “Metagenome” or “Natural Organic Matter” from the National Microbiome Data Collaborative database, focusing on studies related to the Earth Microbiome Project and the 1000 Soils Research Campaign. |

I am looking for microbiome data samples that involve metagenomic analysis or natural organic matter studies, particularly those associated with large collaborative projects like the Earth Microbiome Project or soil research initiatives. |

Table 2.

Evaluation results across four language models on simple, complex, and combined (overall) query sets. Metrics include average end-to-end retrieval time (in seconds), and match rates at the site, page, and schema levels, which reflect how accurately the system localizes data access targets under different reasoning conditions.

Table 2.

Evaluation results across four language models on simple, complex, and combined (overall) query sets. Metrics include average end-to-end retrieval time (in seconds), and match rates at the site, page, and schema levels, which reflect how accurately the system localizes data access targets under different reasoning conditions.

| Model |

Query Type |

Avg. Time (s) |

Site Match |

Page Match |

Schema Match |

| Llama3.3 |

Complex |

40.84 |

0.592 |

0.449 |

0.449 |

| Simple |

37.76 |

0.755 |

0.612 |

0.612 |

| Overall |

39.30 |

0.673 |

0.531 |

0.531 |

| DeepSeek-R1 |

Complex |

13.80 |

0.571 |

0.449 |

0.388 |

| Simple |

13.34 |

0.694 |

0.592 |

0.510 |

| Overall |

13.57 |

0.633 |

0.520 |

0.449 |

| Qwen3 |

Complex |

24.83 |

0.531 |

0.429 |

0.367 |

| Simple |

34.51 |

0.612 |

0.531 |

0.469 |

| Overall |

29.67 |

0.571 |

0.480 |

0.418 |

| Gemma |

Complex |

13.81 |

0.531 |

0.408 |

0.367 |

| Simple |

12.64 |

0.612 |

0.490 |

0.449 |

| Overall |

13.22 |

0.571 |

0.449 |

0.408 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).