1. Introduction

Nasal polyps, benign, grape-like growths in the nasal passages and sinuses [

1], present a significant clinical challenge. These growths can lead to substantial morbidity, including nasal obstruction, chronic rhinosinusitis, and olfactory dysfunction [

1,

2]. Accurate and timely detection is crucial for effective management [

1,

3], yet current diagnostic methods, primarily relying on endoscopic examination by trained specialists [

4], suffer from subjectivity and potential human error [

4]. This inherent variability in diagnosis underscores the need for objective, reliable diagnostic tools. The field of artificial intelligence (AI), particularly in image analysis, offers a promising avenue to address these limitations [

4,

5].

1.1. Application of AI in Ear, Nose and Throat (ENT)

The application of AI in otolaryngology, encompassing the ear, nose, and throat (ENT) domain, is rapidly expanding. A systematic review focusing on rhinology specifically investigated the applications of AI, machine learning, and deep learning in this field. The study, conducted by [

6], followed the PRISMA guidelines, resulting in the analysis of 39 eligible articles from a pool of 1378 unique citations. These studies employed diverse AI systems, with inputs ranging from compiled datasets and verbal descriptions to two-dimensional (2D) images. Outputs were largely dichotomous or nominal classifications of polyp presence or absence. The most prevalent AI models used in these studies were support vector machines (SVMs) and convolutional neural networks (CNNs). While the model reliability varied across studies, reported accuracies generally fell within the range of 80% to 100%. However, a critical limitation emerged: the lack of publicly accessible code sources significantly hinders the reproducibility and advancement of research in this area. Researchers are often forced to reconstruct models from scratch, impeding collaborative progress and efficient knowledge dissemination. Furthermore, the relatively limited size of the available data pools in many studies poses a significant challenge. This necessitates substantial interpretive work prior to the analytical process, potentially introducing bias and affecting the generalizability of findings. The inherent limitations of data scarcity and lack of code transparency call for a concerted effort to establish standardized datasets and encourage open-source sharing of AI models to facilitate future research and improve the reliability of AI-based diagnostic tools in rhinology.

1.2. Automated Detection of Polyps

The automated detection of polyps, across various anatomical locations, is a major area of interest in medical image analysis. While colorectal polyps have been extensively studied in AI applications, the detection of nasal polyps presents a similarly important challenge. Several studies have explored the application of AI, particularly deep learning techniques, to both domains, highlighting the versatility of these models in handling different types of polyps.

[

7] proposed an ensemble-based deep convolutional neural network (CNN) for the identification of polyps from colonoscopy videos. This approach combined the strengths of different CNN architectures, such as ResNet and Xception, achieving performance metrics exceeding 95% across various algorithm parameters. Similarly, [

8] developed a CNN-based deep learning model for the detection and classification of colorectal polyps from colonoscopy images, incorporating image pre-processing techniques to enhance image quality and improve the model’s performance. These studies demonstrate the strong potential of deep learning for accurate and efficient polyp detection, a concept that extends beyond the gastrointestinal tract.

Expanding this approach to nasal polyps, researchers have begun adapting deep learning techniques to endoscopic images of the nasal cavity. Nasal polyps are soft, painless, noncancerous growths that develop in the lining of the nasal passages or sinuses. Like colorectal polyps, their early detection is crucial for effective treatment and disease management.

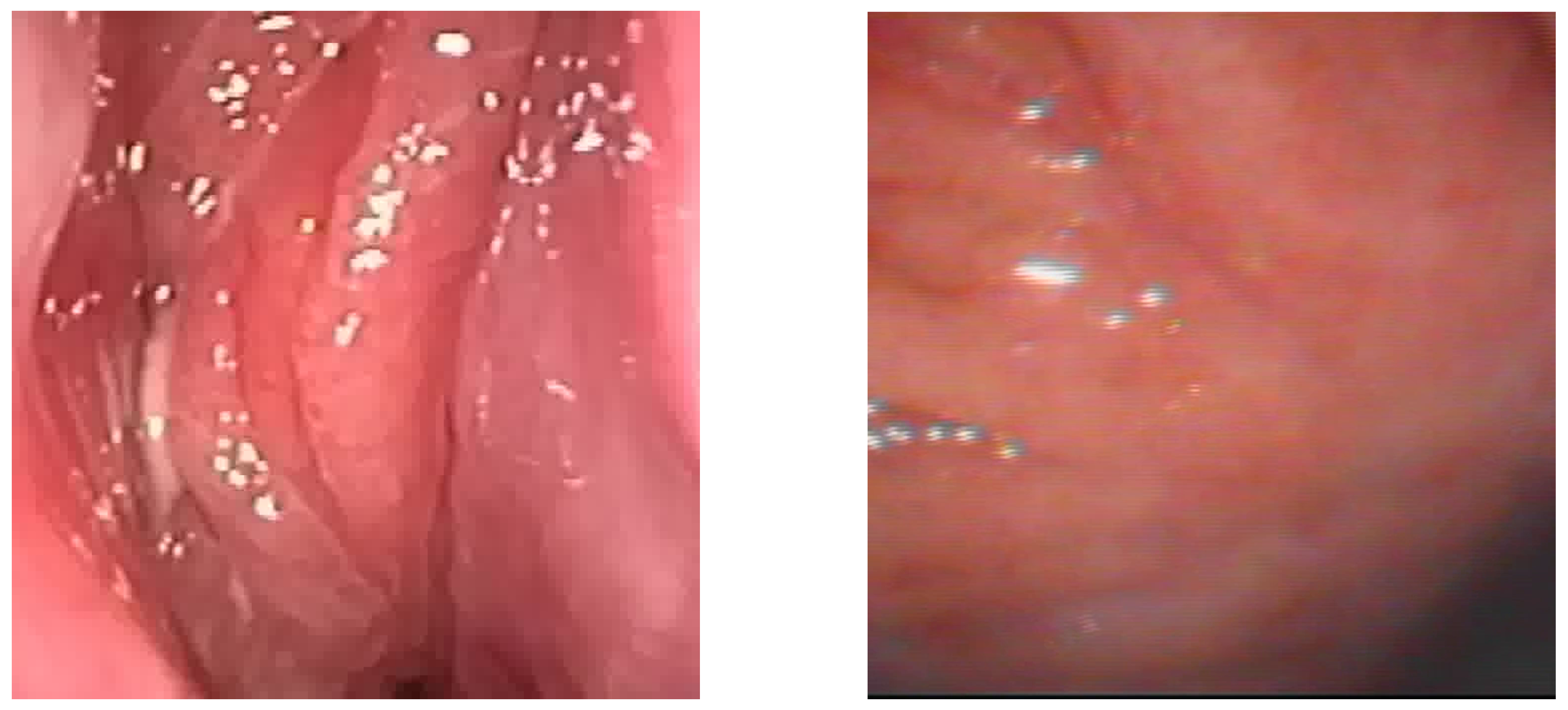

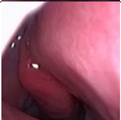

Figure 1.

Sample of Nasal Endoscopy indicating Polyp (left) vs Non-Polyp (right)

Figure 1.

Sample of Nasal Endoscopy indicating Polyp (left) vs Non-Polyp (right)

[

6,

9] demonstrated the feasibility of a CNN-based system for the automated detection and classification of nasal polyps and inverted papillomas from nasal endoscopic images. The use of endoscopic imaging, akin to colonoscopy in colorectal polyp detection, underscores the adaptability of AI-based diagnostic tools to different medical imaging modalities. The ability of AI to assist clinicians in differentiating between various nasal cavity mass lesions, a task demanding considerable expertise, is particularly promising.

By bridging research on polyp detection across different anatomical regions, these advancements illustrate the broader applicability of AI in medical diagnostics. The success of CNN-based approaches in both gastrointestinal and nasal polyp detection paves the way for further interdisciplinary innovations, refining deep learning methods to improve accuracy, efficiency, and clinical utility.

1.3. Limitations of Current AI Applications in Polyp Detection

Despite the considerable promise of AI in polyp detection, several significant limitations currently impede its widespread clinical adoption. These limitations necessitate careful consideration and further research to fully realize the potential of AI in this field.

Data Scarcity and Variability: The availability of substantial, high-quality, and meticulously annotated datasets is a critical prerequisite for training robust AI models. However, the acquisition of such datasets for nasal polyp detection presents considerable challenges . The inherent variability in polyp morphology, the potential for variations in image quality across different imaging modalities, and inconsistencies in imaging protocols further complicate the process of model training and validation . This lack of standardized data significantly restricts the generalizability and reliability of current AI models [

6].

Algorithm Generalizability and Robustness: AI models, particularly those based on deep learning architectures, are susceptible to overfitting. This means that they may perform exceptionally well on the data used for training but exhibit poor performance when presented with unseen data. This limitation restricts the generalizability of these models to diverse patient populations and various clinical settings [

6]. Furthermore, the robustness of these models to noise and variations in image quality needs substantial improvement.

Lack of Explainability and Transparency: Many deep learning models operate as "black boxes," meaning their decision-making processes are not readily transparent or easily interpretable. This lack of transparency makes it difficult for clinicians to understand how the AI system arrives at its predictions, which naturally hinders trust and acceptance in the clinical setting. The development of explainable AI (XAI) methods is therefore critical for enhancing the transparency and interpretability of these models [

10].

Clinical Workflow Integration: The seamless integration of AI systems into existing clinical workflows demands careful consideration of several factors. These include the design of user-friendly interfaces, the efficient integration of data from various sources, and the potential impact on overall clinical efficiency [

10]. The development of user-friendly and seamlessly integrated AI tools is essential for successful clinical adoption.

Ethical and Regulatory Concerns: The application of AI in healthcare raises important ethical and regulatory concerns, including data privacy, the potential for algorithmic bias, and issues of liability [

6]. Addressing these concerns is paramount for the responsible and equitable implementation of AI systems in clinical practice.

1.4. Main Contribution

This paper presents significant advancements in AI for medical diagnostics of sinonasal patients - specifically in detecting and classifying nasal polyps. The main contributions are:

- (1)

Transfer Learning from Pre-trained MobileNetV2 Model: We developed a model using transfer learning from a pre-trained MobileNetV2 model, fine-tuned for nasal polyp detection, achieving superior accuracy over existing methods.

- (2)

State-of-the-art accuracy: The model demonstrates high accuracy in both frame-based and patient-based level, validated against independent test sets, and matches the performance of expert clinicians.

- (3)

Edge Hardware Deployment: Our AI model is optimized for edge hardware, enabling real-time diagnostics at the point of care, beneficial for resource-limited settings.

These contributions highlight the practical and clinical relevance of our AI solution, which operates in real-time aspects to promote better patient outcomes and optimize healthcare delivery.

2. Materials and Methods

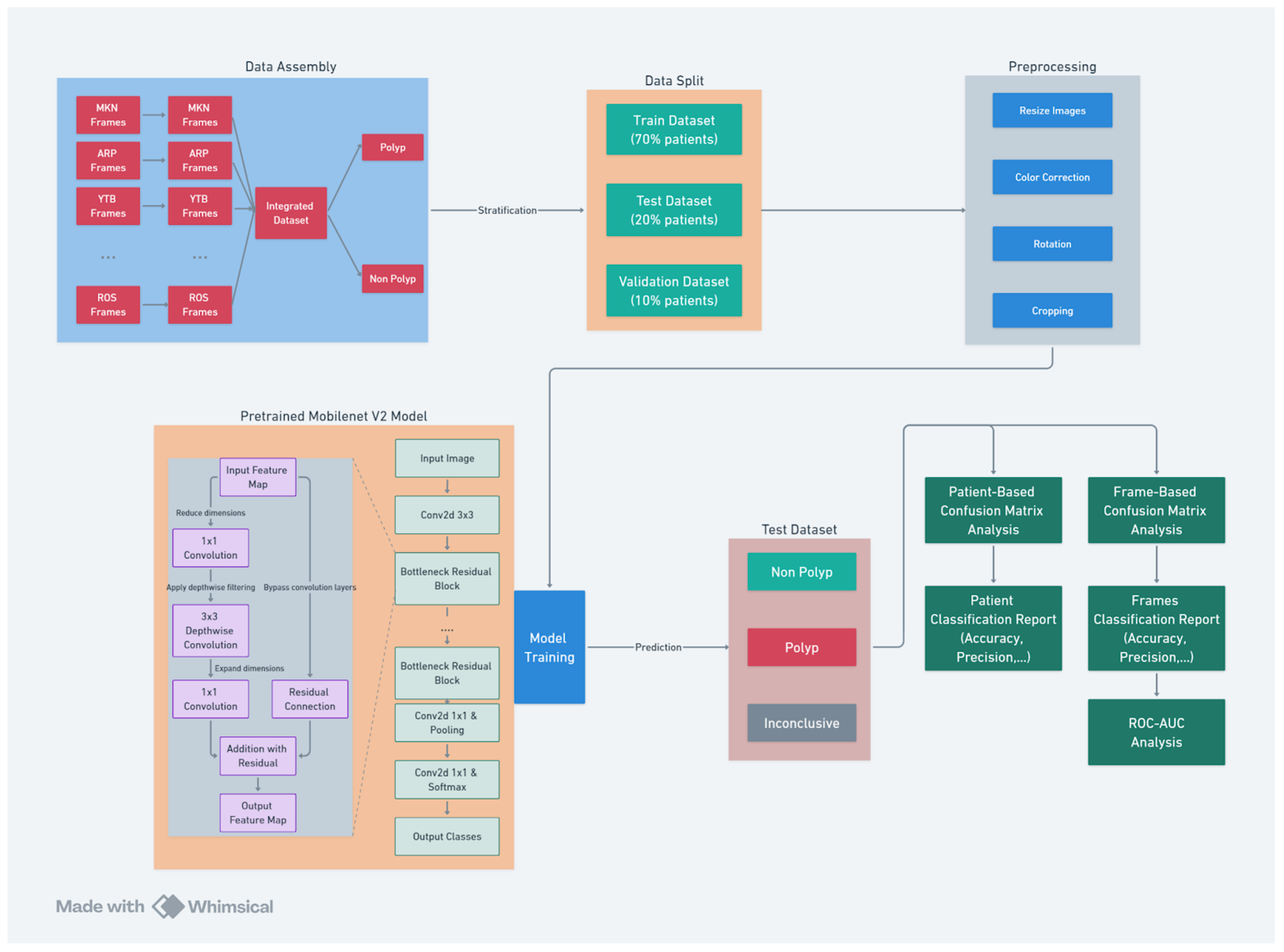

This section provides a comprehensive overview of the algorithm development pipeline (see

Figure 2), detailing each phase from dataset preparations including labeling, to video conversion and data preprocessing to the implementation of advanced machine learning techniques using the MobileNet V2 architecture. The accompanying diagram illustrates the structured workflow of the project, encompassing several critical stages:

Data Collection: Videos of nasal endoscopy has been collected from numerous sources including private Ear, Nose and Throat (ENT) clinics (including deindentified videos from Dr Mamikonyan and Dr Arpi which are two lithuanian ENT specialists as well as Youtube -YTB- videos).

Data Assembly: Frames from multiple video sources are collected and integrated to form a comprehensive dataset. The data were labeled by an ENT expert into ’Polyp’ and ’Non Polyp’ classes.

Data Split: The dataset is strategically divided into training, testing, and validation subsets. The data is stratified by patient. This ensures unbiased model training and evaluation.

Preprocessing: Images undergo various preprocessing steps, including resizing, color correction, rotation, and cropping. These steps standardize the data and enhance model performance.

Model Training: The diagram outlines the architecture of the pre-trained MobileNet V2 model, highlighting the progression from input images to feature extraction and classification output. The model later was fine-tuned on our polyp classification data.

Model Evaluation: The final stage involves a dual approach to model evaluation. Patient-based and frame-based confusion matrices, along with ROC-AUC analysis, are used to assess the model’s diagnostic accuracy.

This structured approach ensures a thorough and systematic implementation of the polyp detection model, with each stage contributing to the overall efficacy and reliability of the system.

2.1. Dataset Collection and Description

The initial phase of the project involved acquiring a proprietary collection of endoscopic video recordings from various international Otolaryngologists (ENTs) across multiple sources including private ENTs and online. These recordings constitute the primary data source for the project, with each video providing a sequential visual dataset essential for polyp identification. Additional recordings were obtained from publicly available sources.

Given the temporal nature of the videos (with an average length of 1 minute with framerate), they were decomposed into individual frames. This conversion is a crucial step, as it transforms the dynamic video data into a format suitable for static image analysis, which aligns well with contemporary image-based deep learning methodologies. To reduce redundancy and computational load, frames were extracted at different intervals. This selection frequency was determined to balance the need for data sufficiency with processing efficiency.

2.1.1. Data Labeling

The labeling of the dataset, a critical step integral to the success of any supervised machine learning project, was meticulously executed with human-level precision by an expert ENT specialist. Leveraging such high-level medical expertise, we established a robust dataset that ensures the reliability of subsequent model training and evaluation stages.

2.1.2. Data Stratification and Split

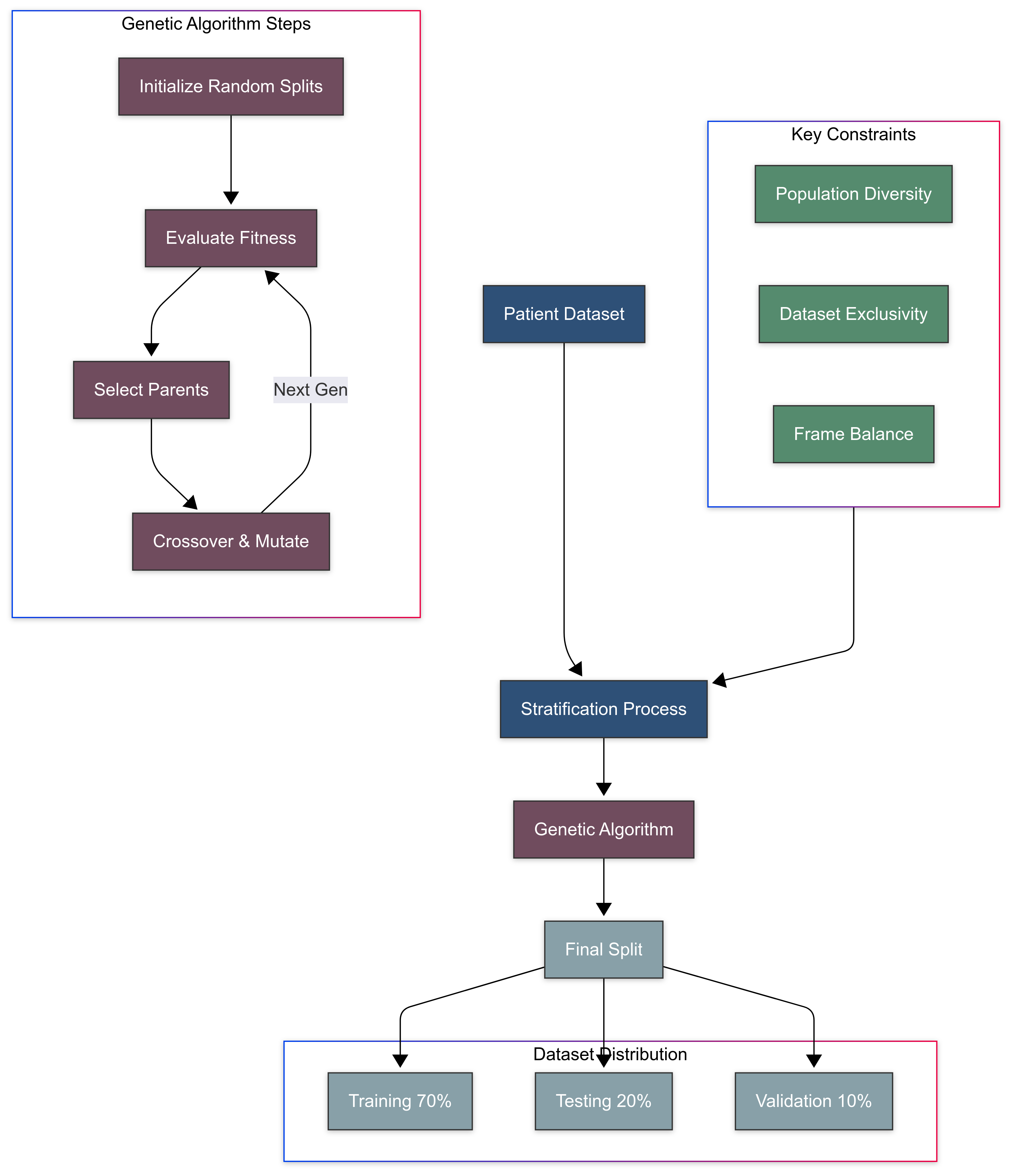

In this section, we describe the stratification and splitting process of our dataset (See

Figure 3), highlighting its critical importance for developing a robust and clinically applicable polyp detection model. Stratification by patients ensures that our model generalizes across diverse individual characteristics and prevents the leakage of patient-specific features between training and validation/testing sets as well as balance the number of frames across different classes. This novel stratification method guarantees that the model’s performance metrics are both statistically valid and clinically relevant.

Importance of Stratification

Stratification in the context of medical data is essential for ensuring that the trained model is not only statistically valid but also clinically applicable. For this project, patient-centric stratification was crucial. The variability among patients due to physiological differences, pathology types, and imaging conditions necessitates that the model learns to generalize across a diverse set of individuals. Stratification by patients, as opposed to by individual frames, prevents leakage of patient-specific features between training and validation/testing sets, which could artificially inflate performance metrics.

Stratification Methodology

|

Algorithm 1 Patient-Centric Dataset Stratification Using Genetic Algorithm |

Require:

- 1:

▹ Set of all patients - 2:

▹ Function returning frames for patient

- 3:

, , ▹ Desired split ratios - 4:

▹ Maximum number of generations - 5:

▹ Size of the population

Ensure:

- 6:

▹ Final dataset splits for training, validation, and test - 7:

functionComputeFitnessScore(split) ▹ Evaluates how well a given split matches the target ratios - 8:

- 9:

for all do

- 10:

- 11:

desired ratio for this set - 12:

- 13:

end for

- 14:

return

- 15:

end function - 16:

procedureStratifyDatasetWithGeneticAlgorithm(P) - 17:

InitializeRandomSplits(P, ) - 18:

- 19:

while do

- 20:

empty list - 21:

for all do

- 22:

ComputeFitnessScore() - 23:

Add to

- 24:

end for

- 25:

SelectTopPerformingSplits() - 26:

empty list - 27:

while do

- 28:

RandomlySelectParents() - 29:

PerformCrossover(, ) - 30:

ApplyMutation() - 31:

Add to

- 32:

end while

- 33:

- 34:

- 35:

end while

- 36:

return SelectBestSplit() - 37:

end procedure - 38:

functionPerformCrossover() ▹ Combines two parents at a crossover point to form a new split - 39:

Random integer between 1 and

- 40:

CombinePatientsAtPoint(, , ) - 41:

return

- 42:

end function - 43:

functionApplyMutation() ▹ Randomly moves a patient to another set to encourage diversity - 44:

if RandomFloat then

- 45:

SelectRandomPatient(P) - 46:

Random choice from

- 47:

ReassignPatientToSet(, , ) - 48:

end if

- 49:

return

- 50:

end function

|

We employed a stratified random sampling technique to allocate patients to our datasets (detailed by Algorithm 1). The stratification was governed by several constraints:

Ensuring that each dataset reflects the diversity of the overall patient population.

Keeping the patients exclusive to one dataset to avoid information bleed.

Balancing the number of frames in each dataset while adhering to the proportionality in terms of patient numbers.

To achieve this, a genetic algorithm was implemented as follows:

Initialization: An initial population of potential splits was generated randomly, ensuring that each patient was assigned to only one dataset.

Fitness Function: A custom fitness function was designed to evaluate how close each potential split was to the desired distribution of 70% training, 20% testing, and 10% validation datasets.

Selection: The best-performing splits were selected to serve as "parents" for the next generation.

Crossover and Mutation: These parents were combined and occasionally mutated to create a new generation of splits, introducing variation and allowing for the evolution of better solutions.

Iteration: This process was iterated over multiple generations, continually improving the fitness of the population until the algorithm converged on an optimal or near-optimal solution.

2.1.3. Data Preprocessing

In this section, we outline the preprocessing steps essential for preparing the endoscopic images for model training. These steps ensure that the images are standardized and augmented effectively, enhancing the robustness and generalizability of the polyp detection model.

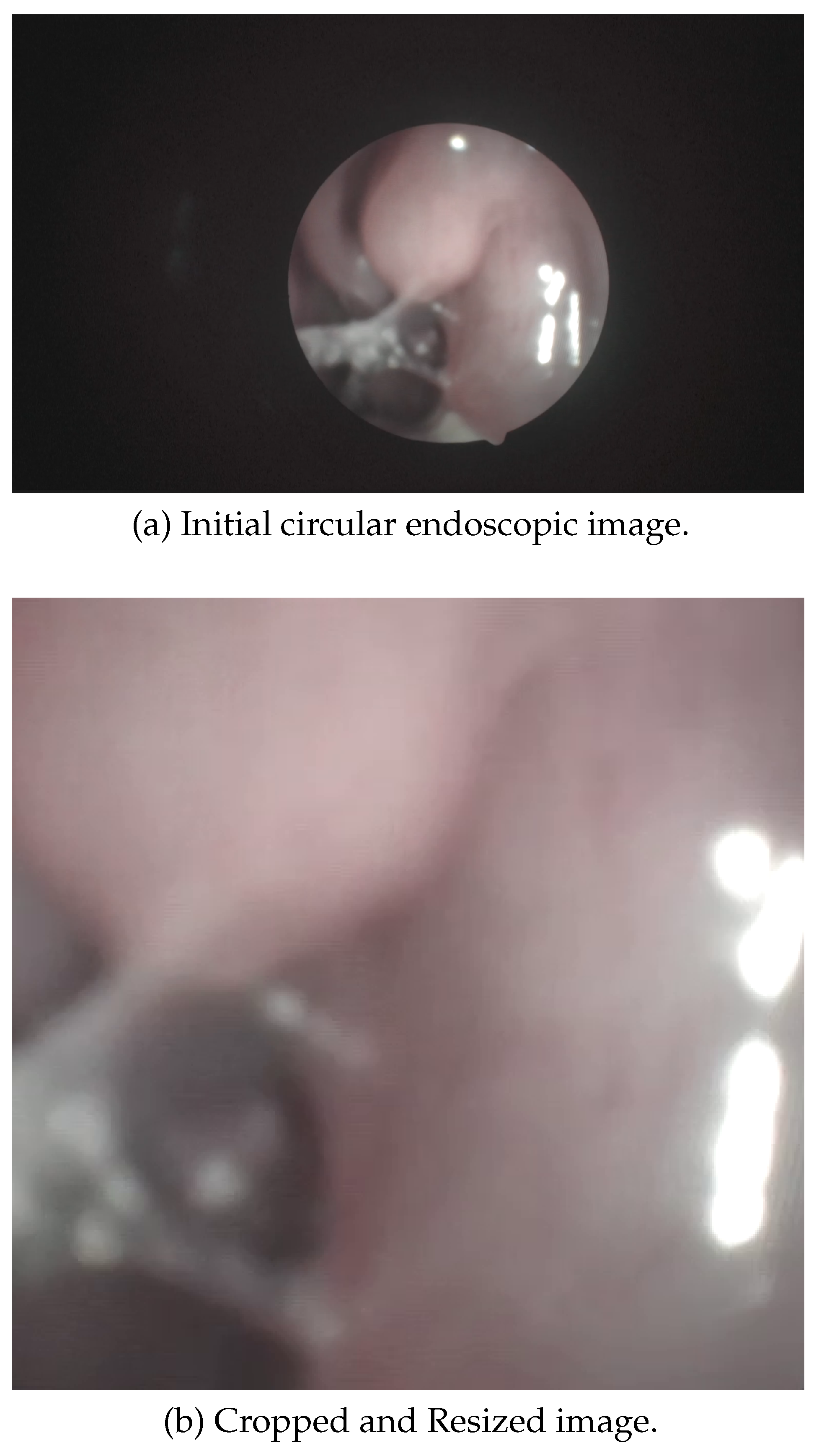

Cropping and Resizing

Given that endoscopic images typically have a circular field of view due to the camera lens, an automatic cropping algorithm was developed to transform the raw circular view (

Figure 4) into the largest possible inscribed square. An automated pipeline (See Algorithm 2) first detects the region of interest (ROI) using Hough Circle Transform on initial frames. The smallest valid circle is selected per frame, and its largest inscribed square is calculated. To ensure robustness against frame-to-frame variations, the median ROI from these candidates is used for cropping. This eliminates non-informative black borders while retaining diagnostically relevant regions. Subsequently, all frames are resized to a standardized resolution (

pixels in implementation), maintaining aspect ratio consistency for downstream computational analysis

Image Quality Standardization

To ensure that the model’s learning is based on the relevant medical features rather than artifacts of the imaging process, we implemented a series of steps to standardize image quality:

Color Normalization: Adjusting the color balance to correct for variations in lighting and camera sensor characteristics.

Contrast Enhancement: Improving the visibility of important features while maintaining the natural appearance of the tissue.

Data Augmentation

Data augmentation is a crucial step in the preprocessing pipeline to artificially expand the dataset and improve the model’s generalization capability. This technique helps the model to better handle unseen data and non-conventional images, which may result from the incorrect use of hardware or variations in imaging conditions. The specific augmentation methods applied include:

Rotation: Images were rotated at various angles (e.g., 90°, 180°, 270°). This helps the model to recognize polyps from different orientations, which is critical given the rotational variability inherent in endoscopic procedures.

Scaling: Images were rescaled by different factors (e.g., 0.8x, 1.2x). Scaling helps the model to become invariant to the size variations of polyps and to better handle zoom effects that might occur due to camera movements.

Flipping: Horizontal and vertical flips were applied. This augmentation helps the model to recognize polyps irrespective of their orientation within the image, improving robustness to positional variations (left and right nasal passage are almost mirror images of eachother).

Translation: Images were translated horizontally and vertically. This technique helps in making the model invariant to slight shifts in the position of the camera, ensuring that the model can detect polyps even when they are not perfectly centered.

Brightness and Contrast Adjustments: Random adjustments to brightness and contrast were made. This augmentation compensates for lighting variations that can occur during endoscopic procedures, ensuring the model can handle different illumination conditions. This augmentation works well on an endoscope hardware since it is a lightweight algorithm.

Noise Injection: Gaussian noise was added to some images. This helps the model become more robust to imaging artifacts and minor noise that may be present in real-world endoscopic videos.

|

Algorithm 2 Endoscopic Video Preprocessing Pipeline |

Input: Endoscopic video V, target resize dimensions , frame sampling interval n

Output: Set of processed frames

- 1:

procedureDetectRegionOfInterest(V) ▹ Estimates the consistent region of interest (ROI) using Hough Circle Detection - 2:

▹ Candidate ROI coordinates - 3:

for to 10 do

- 4:

ReadFrame(V) - 5:

Convert F to grayscale - 6:

MedianBlur(G, kernel size = 5) - 7:

HoughCircles(, radius range = [250, 400]) - 8:

if then

- 9:

Circle with smallest radius in

- 10:

▹ Square side of inscribed region - 11:

,

- 12:

Add to

- 13:

end if

- 14:

end for

- 15:

return Median bounding box from based on area - 16:

end procedure - 17:

procedurePreprocessVideoFrames() ▹ Applies ROI cropping, resizing, and sampling to video frames - 18:

DetectRegionOfInterest(V) - 19:

- 20:

while HasFrame(V) do

- 21:

ReadFrame(V) - 22:

▹ Crop to detected ROI - 23:

Resize() - 24:

if then

- 25:

Save() - 26:

end if

- 27:

- 28:

end while

- 29:

end procedure

|

These augmentation techniques collectively ensure that the model is exposed to a wide variety of transformations, thereby enhancing its ability to generalize well to new and diverse clinical scenarios.

2.2. Polyp Classification Trainning Stages

This section provides a detailed description of the MobileNet V2 architecture and the training process used for the polyp detection model. The chosen architecture balances efficiency and accuracy, making it suitable for deployment across various hardware platforms, including high-end GPUs and mobile devices. The training process leverages pre-trained models to accelerate convergence and fine-tunes them for the specific task of polyp detection.

2.2.1. Model Description and Training Process

MobileNet V2 Architecture Overview

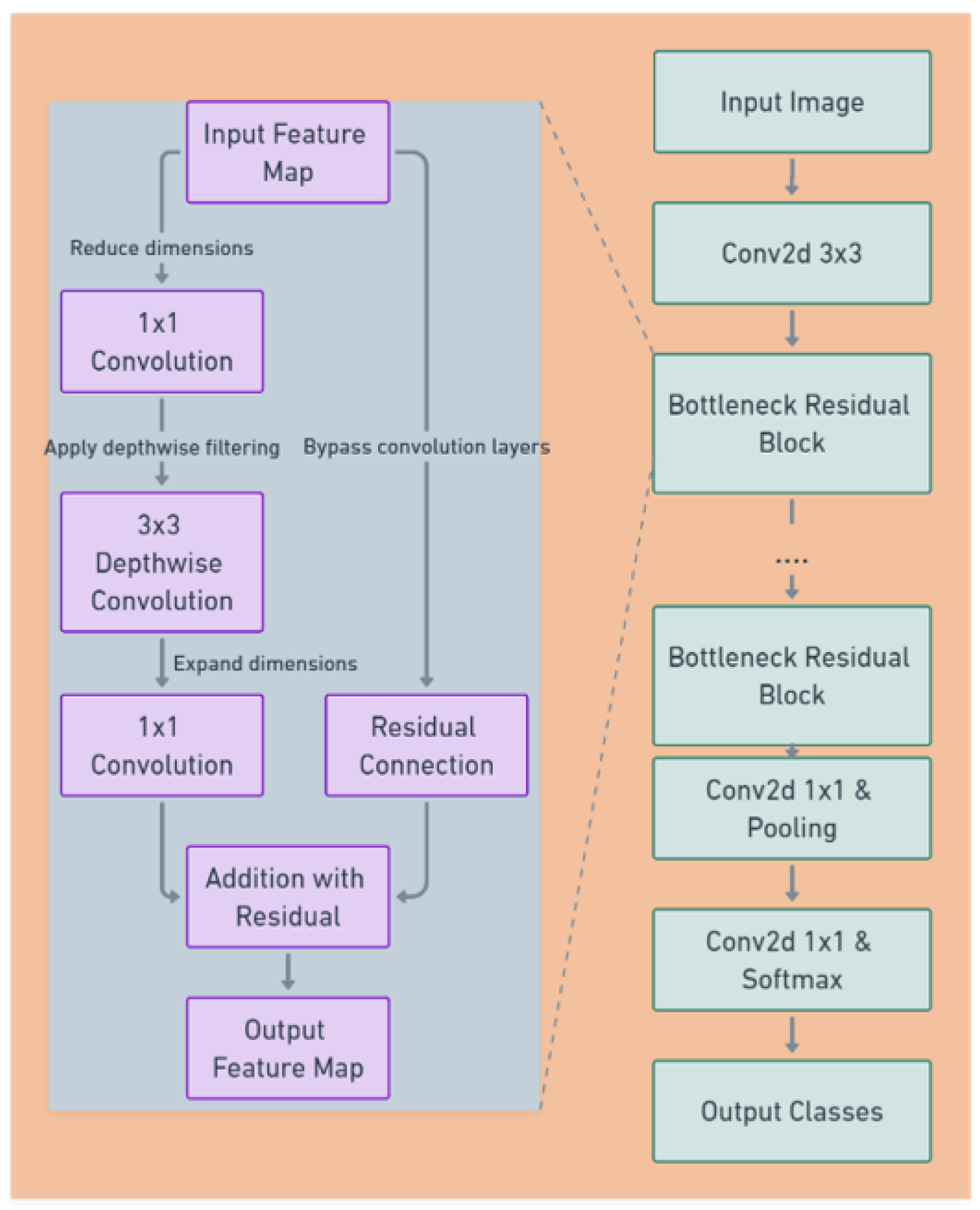

The model of choice for this project was MobileNet V2 (see

Figure 5), a state-of-the-art deep learning architecture renowned for its balance between efficiency and accuracy. MobileNet V2’s lightweight structure includes depthwise separable convolutions, which significantly reduce the number of parameters without sacrificing performance, making it suitable for a wide range of hardware, from high-end GPUs to mobile devices.

Key features of MobileNet V2 [

11] include:

Bottleneck Residual Blocks: MobileNet V2 utilizes residual connections around the bottleneck layers, which facilitate the training of deeper network architectures.

Inverted Residuals and Linear Bottlenecks: This feature involves the use of lightweight depthwise convolutions to filter features as a source of non-linearity, followed by a linear layer to create a bottleneck structure that reduces computation.

Training Process

1- Pre-Training

The model leveraged a version of MobileNet V2 pre-trained on a large-scale image dataset (ImageNet) [

12], providing a robust starting point for feature extraction. This approach allowed the model to utilize learned patterns from a broad range of visual data, accelerating the convergence time during training on our specific polyp dataset.

2- Fine-Tuning

During fine-tuning (learning rates, epochs and batch numbers), the preprocessed and stratified frame data served as the input to the network. Given that the frames were resized to a uniform dimension during preprocessing, they were readily compatible with the MobileNet V2 input requirements. The primary goal during fine-tuning was to adapt the generalized features learned during pre-training to the more specialized task of polyp detection. The last classification layer of the network were retrained with our dataset to accurately classify frames into ’Polyp’ or ’Non Polyp’.

3- Model Outputs

The output layer of the MobileNet V2 was modified to reflect the classification needs of this project. Softmax activation functions were used to output a probability distribution over the possible classes (Polyp or Non Polyp).

3. Results, Performance, and Discussion

This section details the evaluation of the polyp detection model, starting with the rationale for selecting MobileNetV2, followed by its performance analysis using ROC-AUC curves, confusion matrices, visual analysis, and inference time measurements.

Noting that the used dataset contains a total of 36 patients with around 12,000 frames distributed equally across two classes (Polyp and Non-Polyp).

The training configuration for the MobileNetV2 model is summarized in

Table 1. These hyperparameters were carefully selected to ensure stable training, good generalization, and compatibility with real-time inference requirements.

The loss function used for training is the

binary cross-entropy loss, which is commonly applied in binary classification tasks. It measures the distance between the predicted probabilities and the actual class labels. The formula for the binary cross-entropy loss is given by:

where

is the ground truth label for sample

i, and

is the predicted probability that the sample belongs to the positive class (i.e., Polyp). In the context of polyp classification, this function penalizes the model more when it confidently misclassifies a polyp as non-polyp or vice versa. By minimizing this loss, the model is encouraged to produce probability outputs that align closely with the true class distributions, improving its discriminative ability for clinical use.

The use of the Adam optimizer further enhances training stability by adapting learning rates for each parameter, and the early stopping criterion prevents overfitting on the relatively small dataset.

3.1. Justification for Choosing MobileNetV2

The selection of MobileNetV2 as the optimal model for polyp detection was guided by a comprehensive comparison of six architectures across three critical dimensions: accuracy, inference speed, and model size (

Table 2).

While MobileNetV3 achieved comparable accuracy (F1=0.97), its slower inference time (12 ms/frame) makes it less suitable for real-time clinical workflows compared to MobilenetV2 [

11]. Larger models like VGG16 (138M parameters) and ResNet50 (25.6M parameters) failed to meet speed requirements despite higher parameter counts, highlighting the inefficiency of dense architectures in embedded medical systems. EfficientNetB0, while lightweight, lacked the necessary speed-accuracy balance (F1=0.96, 13 ms/frame), making MobileNetV2 the optimal choice for this application.

3.2. ROC-AUC Curve Analysis

3.2.1. Overview of ROC-AUC

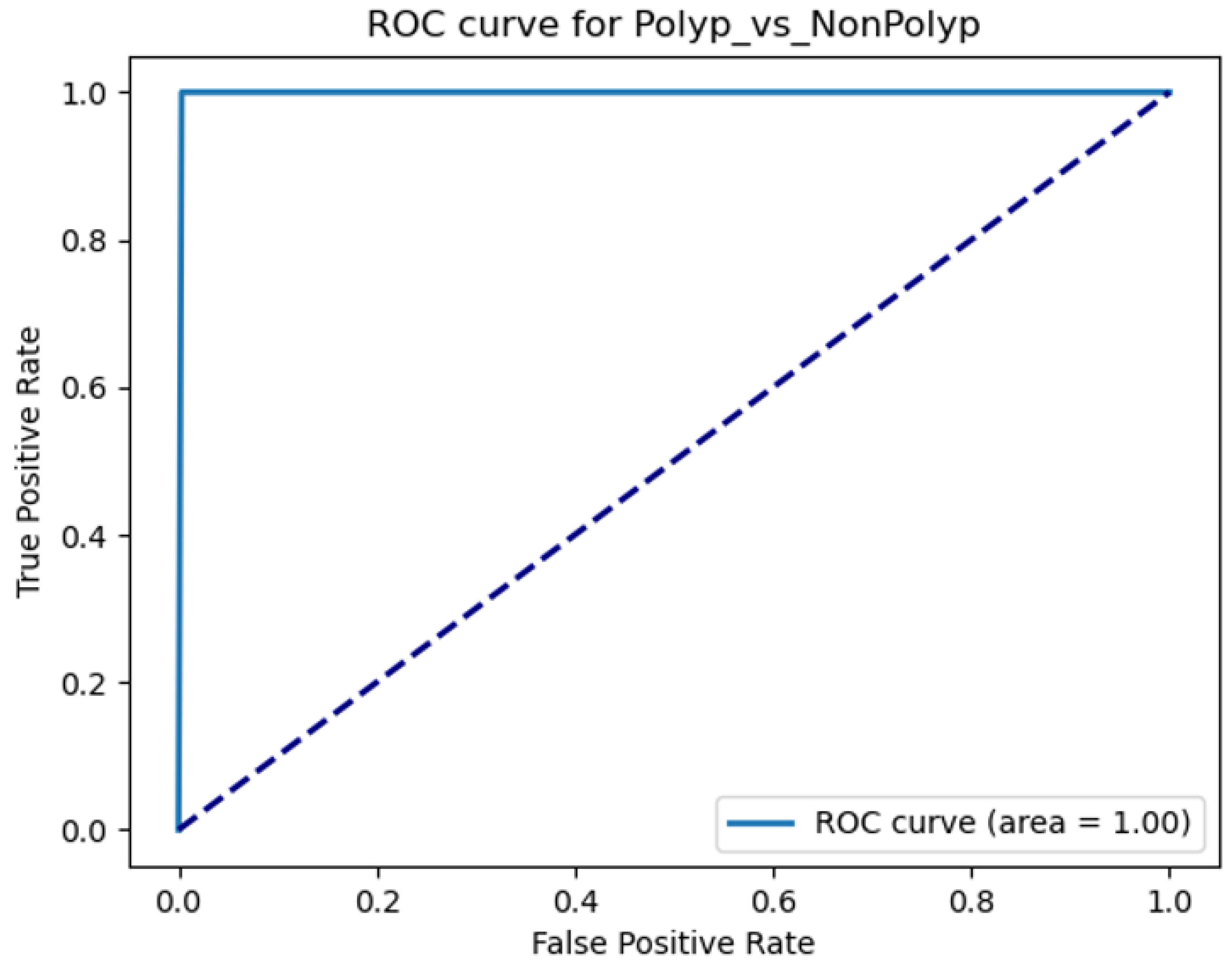

The Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve is a standard tool for evaluating binary classifiers, plotting sensitivity (TPR) against 1-specificity (FPR) across threshold settings [

20]. The Area Under the Curve (AUC) quantifies overall performance, with AUC=1.0 indicating perfect discrimination.

3.2.2. Implementation for Polyp Detection

For MobileNetV2, ROC-AUC analysis identified an optimal threshold balancing TPR and FPR (

Figure 6), critical for clinical usability where both false positives and negatives carry significant consequences.

3.3. Confusion Matrix Analysis

3.3.1. Frame-Based Confusion Matrix

Frame-level performance was evaluated using a confusion matrix (

Table 3), which provides granular insight into error types critical for medical diagnostics [

21].

Inconclusive frames in

Table 4 are defined as frames that have a prediction accuracy

either for Polyp or Non-Polyp labels.

3.3.2. Patient-Based Confusion Matrix

Patient-level accuracy was determined using temporal aggregation with two configurations:

≥20 consecutive frames labeled ‘Polyp’ with ≥95% confidence.

Table 4.

≥20 non-consecutive frames labeled ‘Polyp’ with ≥95% confidence.

Table 5.

reflecting clinical diagnostic workflows [

22]. The results in both tables demonstrate high accuracy

.

3.4. Visual Analysis of Classification Outcomes

Example images in

Table 6 illustrate MobileNetV2’s performance. Correct classifications demonstrate robustness to clear polyps, while misclassifications often involve ambiguous features or extreme lighting conditions. These errors do not affect patient-level diagnoses due to temporal aggregation.

3.5. Inference Time Evaluation

3.5.1. Importance of Inference Time

Real-time analysis (≤33 ms/frame at 30 Hz) is critical for clinical usability, enabling immediate feedback during endoscopic procedures [

22]. MobileNetV2’s inference times under clinical hardware configurations are:

3.6. Discussion

The results indicate exceptionally high-performance metrics, suggesting that the model is highly effective in identifying polyps from endoscopic video frames in real-time clinical workflows. However, a detailed analysis of the model’s components through an ablation study further validates its design choices and identifies critical factors for maintaining performance.

3.6.1. Ablation Study Analysis

An ablation study was conducted to evaluate the impact of individual components in the model’s training pipeline (

Table 7). Results demonstrate that each component contributes significantly to the model’s overall performance:

Rotation Augmentation: Removing rotation augmentation reduced the F1-score by 5% (from 0.97 to 0.92), highlighting the importance of geometric transformations in improving model generalizability.

Cropping: Eliminating cropping augmentation caused a drastic 21% drop in F1-score (to 0.76), indicating that spatial context is critical for accurate polyp detection. This aligns with prior work on the necessity of spatial augmentation in medical imaging.

Stratification: Training without stratified sampling reduced the F1-score by 10% (to 0.87), underscoring the importance of maintaining class balance during training to avoid bias.

Speed Trade-offs: While removing cropping augmentation improved inference speed slightly (to 7 ms/frame), the severe accuracy loss makes this trade-off impractical for clinical use.

These findings confirm that all components of the baseline pipeline are essential for optimal performance. Future work should prioritize retaining these augmentations and exploring additional techniques to further enhance robustness.

3.6.2. ROC-AUC Score

The ROC-AUC score achieved was 1 (for patient based classification), indicating high model performance with approximately 100% sensitivity and 100% specificity across all decision thresholds. This suggests that the model can discriminates between ’Polyp’ and ’Non Polyp’ conditions without any error, representing an ideal scenario rarely seen in medical diagnostic models.

3.6.3. Patient-Based Confusion Matrix

The patient-based confusion matrix corroborates the ROC-AUC score, demonstrating an excellent classification results:

This distinction in patient-based results shows that the model effectively uses the aggregation of frame-based predictions to make accurate diagnoses at the patient level, which is critical for clinical applications where patient outcomes depend on correct overall diagnosis rather than individual frame analysis.

3.6.4. Frame-Based Confusion Matrix

The frame-based confusion matrix also reflects excellent model performance:

True Positives: 5050 polyp frames were correctly identified.

True Negatives: 6383 non-polyp frames were correctly classified.

False Positives: 147 frames were incorrectly identified as polyps.

False Negatives: 214 frames were incorrectly identified as non-polyps.

The frame-based accuracy, particularly the absence of inconclusive frames, underscores the model’s sensitivity and reliability in detecting polyps when they are present. The very low rate of false positives further attests to the model’s precision, ensuring that non-polyp frames are seldom misclassified.

3.6.5. Failure Analysis and Discussion

These results suggest that the model is not only highly accurate but also robust and reliable in its predictions, making it an excellent tool for assisting Otolaryngologists in diagnosing polyps. However, the results also suggests a need for further validation, particularly:

Dataset Diversity: Ensuring that the model has been trained and validated on a diverse set of data to confirm that these results hold across different patient populations and various imaging conditions.

External Validation: Testing the model on external datasets to confirm its generalizability and robustness when faced with new, unseen data.

In conclusion, the polyp detection model appears to be highly effective, but due diligence in the form of further testing and validation is recommended to ensure that these results can be trusted in a real-world clinical setting. This will help confirm that the model can reliably support medical professionals in making accurate diagnostic decisions. The text continues here.

4. Discussion

The polyp detection model utilizing the MobileNet V2 architecture has demonstrated a good performance in our evaluations, achieving high scores across various metrics. The high ROC-AUC score and the results from both patient-based and frame-based confusion matrices indicate that the model is reliable and accurate in identifying polyps from endoscopic video frames.

4.1. Key Achievements

High Sensitivity and Specificity: The model’s ability to correctly identify all true polyp and non-polyp patients in the test dataset indicates high clinical applicability.

Robust Performance Across Frames: The frame-level analysis showed that the model could maintain high accuracy per frame, crucial for real-time polyp detection during endoscopic examinations.

High Patient-Level Diagnostics: The aggregation of frame-level data to make accurate patient-level diagnoses demonstrates the model’s potential utility in clinical settings, where accurate overall patient diagnoses are crucial.

4.2. Future Directions

Continuous improvement and validation are essential to ensure the model’s utility in diverse clinical environments. Future development can include:

Increasing Dataset Size: Expanding the number of patients and frames in the training dataset can help improve the model’s robustness and generalizability. A larger dataset would likely encompass a more diverse array of polyp types, patient demographics, and variability in medical imaging conditions.

External Validation: Conducting external validation studies with datasets collected from different hospitals or clinics can help verify the model’s performance across various real-world settings.

Incorporation of Additional Classes: Adding more classes to the model, such as different types of polyps or other sinonasal anomalies, could increase its utility by providing a more comprehensive diagnostic tool.

Cross-Hardware Compatibility: Ensuring that the model performs consistently across different endoscopic equipment and setups can enhance its adaptability and usability in diverse clinical environments.

In conclusion, the polyp detection model presents a significant advancement in the application of deep learning to medical imaging, particularly in the detection of polyps through endoscopy. By pursuing these future directions, the model can be refined and enhanced to meet the evolving needs of medical diagnostics, ultimately contributing to better patient outcomes in gastrointestinal health.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Abdeslem, A. von Wendorff, and M. Wilson. ; methodology, S.Abdeslem, A. von Wendorff, and M. Wilson.; software, S.Abdeslem.; validation, A. von Wendorff, and M. Wilson.; formal analysis, S.Abdeslem.; investigation, S.Abdeslem.; resources, A. von Wendorff.; data curation, S.Abdeslem.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Abdeslem.; writing—review and editing, A. von Wendorff and M. Wilson.; project administration, A. von Wendorff.; funding acquisition, A. von Wendorff. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Embargo on data due to commercial restrictions. For access and further information please contact

anna@scopimedical.com

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Meltzer, E.O.; Hamilos, D.L.; Hadley, J.A.; Lanza, D.C.; Marple, B.F.; Nicklas, R.A.; Bachert, C.; Baraniuk, J.N.; Baroody, F.M.; Benninger, M.S.; et al. Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. Wiley 2004.

- Kim, S.D.; Cho, K.S. Samters Triad: State of the Art. Korean Society of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Guven, M.; Karabay, O.; Akidil, O.; Yilmaz, M.; Yildrm, M. Detection of Staphylococcal Exotoxins in Antrochoanal Polyps and Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps. Otolaryngology Head & Neck Surgery, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Pan, Z.; Zhu, H.; Wang, Q.; Yang, J.J.; Lei, Y.; Li, J.; Pan, H. Development of a computer-aided tool for the pattern recognition of facial features in diagnosing Turner syndrome: comparison of diagnostic accuracy with clinical workers. Nature Communications 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotkowski, M.C.; Chevillard, M.; Pierrot, D.; Altemeyer, D.; Zahm, J.M.; Colliot, G.; Puchelle, E. Differential adhesion of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to human respiratory epithelial cells in primary culture. Journal of Clinical Investigation 1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girdler, B.; Moon, H.; Bae, M.R.; Ryu, S.S.; Bae, J.; Yu, M.S. Feasibility of a deep learning-based algorithm for automated detection and classification of nasal polyps and inverted papillomas on nasal endoscopic images. International Forum of Allergy and Rhinology 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P.; Balabantaray, B.K.; Bora, K.; Mallik, S.; Kasugai, K.; Zhao, Z. An Ensemble-Based Deep Convolutional Neural Network for Computer-Aided Polyps Identification From Colonoscopy. Frontiers in Genetics 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanwar, S.; Vijayalakshmi, S.; Sabharwal, M.; Kaur, M.; Alzubi, A.; Lee, H.N. Detection and Classification of Colorectal Polyp Using Deep Learning. BioMed Research International 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ay, B.; Turker, C.; Emre, E.; Ay, K.; Aydin, G. Automated classification of nasal polyps in endoscopy video-frames using handcrafted and CNN features. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2022, 147, 105725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stafie, C.S.; Ufaru, I.G.; Ghiciuc, C.M.; Stafie, I.I.; Sufaru, E.C.; Solomon, S.M.; Hncianu, M. Exploring the Intersection of Artificial Intelligence and Clinical Healthcare: A Multidisciplinary Review. Diagnostics 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.C. Mobilenetv2: Inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018, pp. 4510–4520.

- Deng, J.; Dong, W.; Socher, R.; Li, L.J.; Li, K.; Fei-Fei, L. ImageNet: A large-scale hierarchical image database. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; 2009; pp. 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, A.; Sandler, M.; Chu, G.; Chen, L.C.; Chen, B.; Tan, M.; Wang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Pang, R.; Vasudevan, V.; et al. Searching for mobilenetv3. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2019, pp. 1314–1324.

- Tan, M.; Le, Q. Efficientnet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR; 2019; pp. 6105–6114. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q. EfficientNetV2: Smaller Models and Faster Training. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 38th International Conference on Machine Learning; Meila, M.; Zhang, T., Eds. PMLR, 18–24 Jul 2021, Vol. 139, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 10096–10106.

- Liu, Z.; Mao, H.; Wu, C.Y.; Feichtenhofer, C.; Darrell, T.; Xie, S. A convnet for the 2020s. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2022, pp. 11976–11986.

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp. 770–778.

- Szegedy, C.; Vanhoucke, V.; Ioffe, S.; Shlens, J.; Wojna, Z. Rethinking the inception architecture for computer vision. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2016, pp. 2818–2826.

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.1556 2014.

- Fawcett, T. An Introduction to ROC Analysis. Pattern Recognition Letters 2006, 27, 861–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, M.; Lapalme, G. A Systematic Analysis of Performance Measures for Classification Tasks. Information Processing & Management 2009, 45, 427–437. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W. Performance Analysis and Optimization of MobileNetV2 on Apple M2: A Detailed Study of Neural Engine and Compute Unit Selection Strategies. Technical report, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2024.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).