1. Introduction

The Collaborative Outcomes study on Health and Functioning during Infection Times (COH-FIT) [

1] is an international survey study conducted in many countries translated into 30 languages. We report data from the Danish part of the study.

In Denmark, the government attempted to control transmission of the virus beginning in March 2020 by lockdown of institutions, workplaces and cultural and leisure activities. Public gatherings were also restricted. These measures were gradually eased during the summer and autumn of 2020 but were reintroduced and intensified during the winter of 2020-2021 due to rising infection rates. After these restrictions, the periods of lockdown eventually came to an end.

The lockdowns and restrictions were expected to have not only social and economic consequences but also mental health impacts, particularly related to fear of infection and social isolation. These consequences would put stress on the populations and influence mental health. The pandemic affected the mental health of both the general population and individuals with pre-existing mental illnesses. Later reviews comprising more publications have shown that the effects of the pandemic are not straightforward and homogenous between populations [

2].

The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) analyzed global data and found that the COVID-19 pandemic has had a negative impact on mental health worldwide. Anxiety and depression increased substantially, especially where the impact of infection was greatest, and females and younger were more affected [

3]. A similar deterioration in mental health has also been reported in several other reviews (4,5,6). For people with former mental illness the results were mixed but generally many investigations reported they had more severe worsening [

6,

7]. Later reviews have reported that the consequences for the general population were less severe [

2,

8]. Also, for people with former mental disorder health was maybe even less or not at all impacted compared with the general population, possibly because some consequences were experienced as positive e.g., less stress because society closed. [

2,

9].

In this study, we examine how physical and mental health, stress, sleep, loneliness, boredom, and functioning—measured by self-care, interpersonal relationships, hobbies/leisure activities, and work/education—varied in the Danish population with and without mental illness during the first two years of the COVID-19 pandemic

2. Methods

2.1. Setting

The first COVID-19 case in Denmark was registered the 26th of February 2020. The rapid spread throughout Denmark resulted in a national lockdown on the 11th of March 2020, which included several societal restrictions such as assembly bans, social distancing, and closing of educational institutions, daycare facilities, and public workplaces. Restaurants, sport facilities and cultural institutions were closed. In May and June 2020, the number of hospitalizations decreased followed by the termination of most restrictions. When hospitalizations increased during fall and winter 2020/2021, most restrictions were reintroduced. Through 2021, the restrictions were downscaled simultaneously with decreasing number of hospitalizations during winter 2021/2022. On the 1st of February 2022, all restrictions were removed, and COVID-19 was no longer defined as a critical societal disease.

2.2. Data

The Collaborative Outcomes study on Health and Functioning during Infection Times (COH-FIT), is a large-scale survey, including more than 50 countries from all six inhabited continents. COH-FIT aims to identify risk factors affecting the general population and vulnerable subgroups during the COVID-19 pandemic. Additional information about this global study is available elsewhere [

1]. In this study, we present results from the Danish part of COH-FIT. Data was collected through online questionnaires in three separate samples in May 2020, January 2021, and January 2022; a period in which the COVID-19 hospitalizations and societal restrictions mandated by the government varied greatly in Denmark. In May 2020, the questionnaire was promoted by The Danish Mental Health Fund and the National Institute of Public Health, University of Southern Denmark, in newsletters sent to members and in news media. To retrieve representative samples of Danish adults (18+ years) according to sex, age, geographic location, educational level, and occupation, two subsequent data collections in January 2021 (11th to the 20th of January 2021) and in January 2022 (14th to the 20th of January 2022) were performed by a survey agency using an already established panel data set.

2.3. Measures

Physical and mental health, distress and functioning were assessed at each time point by self-report. Respondents were asked to recall and rate on a scale from 0 to 100 their health, distress and functioning during the actual past two weeks, and in the last two weeks before the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak. For each respondent the values were compared and registered as better, worse, or unchanged. The reported results are the percentage of respondents reporting worse, unchanged, or better for each parameter at the three time points the measurements took place.

The respondents were asked about their actual condition and after that the condition in the two weeks before COVID-19, so they only had to consider if it was worse, better or unchanged compared to the actual situation. That made it easier to remember If unchanged they rated the same value as actual condition and there was no need to have an interval for unchanged. This simplification lessened the risk of recall bias.

To obtain information about mental illness, respondents were asked whether they had ever been diagnosed with mental health conditions by a doctor or psychologist. Respondents indicating at least one mental health condition were defined as having a mental illness, while respondents reporting no diagnoses were defined as having no mental illness.

2.4. Weight

To achieve three comparable samples reflecting populations with the same distribution of sex, age, educational level and occupation, the data collected in May 2020 was weighted in accordance with the representative samples from January 2021 and January 2022. Respondents with missing information on educational level in the samples collected in May 2020 (n=450) and January 2022 (n=1) were categorized as having a college/university/PhD, which constituted the largest group.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate the prevalence of mental and physical health, distress and functioning at four different time points: before the COVID-19 pandemic, in May 2020, in January 2021, and in January 2022. All analyses were stratified by preexisting mental illness. All analyses were conducted in STATA version 17.0.

3. Results

In May 2020, a total of 3134 individuals responded to the questionnaire, while respectively 1170 and 1174 responded in January 2021 and January 2022 (

Table 1). In the unweighted sample from May 2020, the proportion of women (84%), respondents between the age of 50-59 years (26%) and those with college/university/PhD educational level (86%) were overrepresented compared to the representative sample from January 2021 and January 2022 (

Table 1). Further, a higher proportion were without an occupation (40%) in May 2020 compared to the sample in January 2021 (22%) and January 2022 (17%) and had at least one mental illness (45%) (15% in January 2021 and 17% in January 2022).

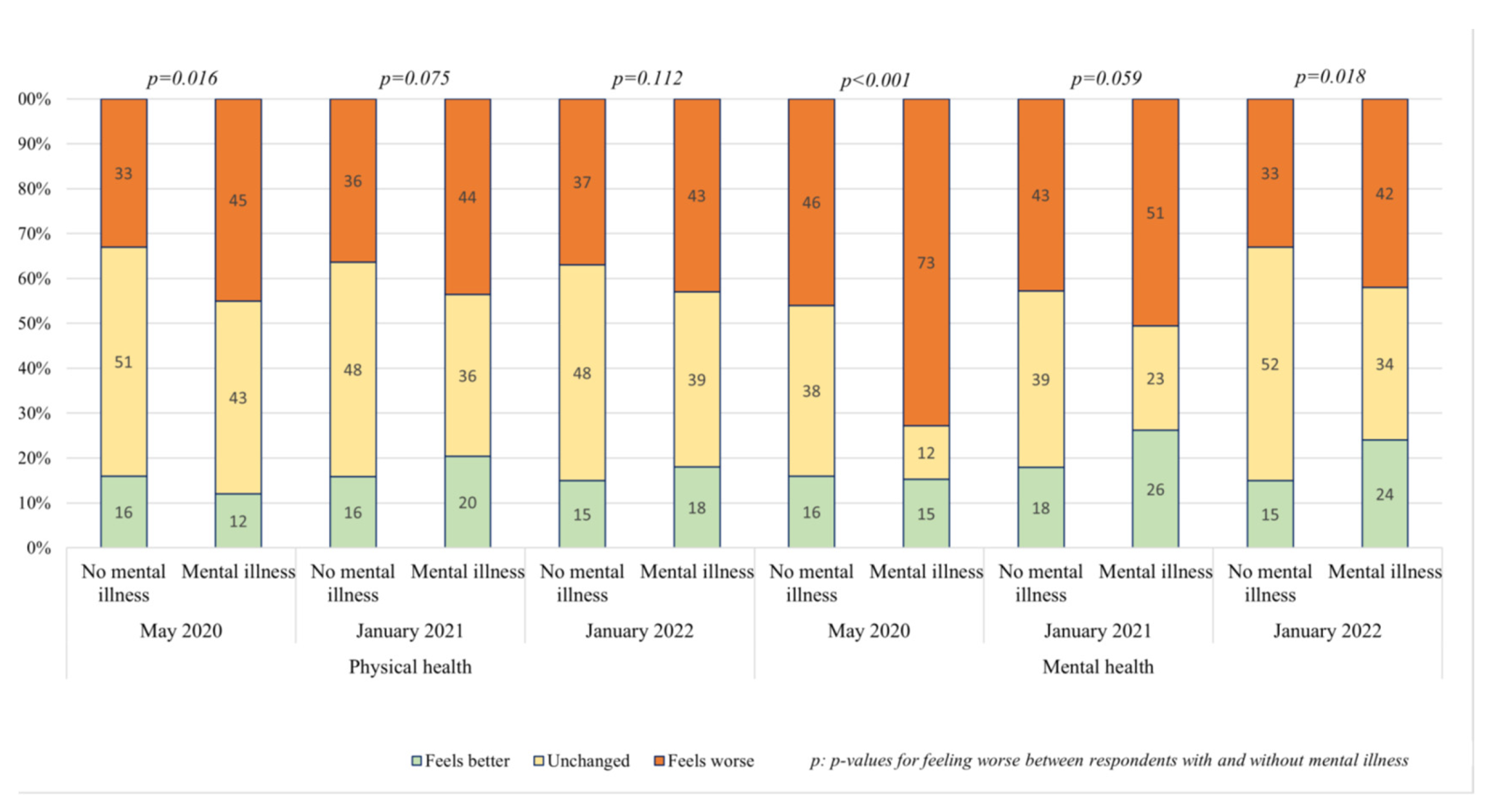

Among the respondents with no mental illness about one third had experienced a worsening of their physical health over time. For the respondents with mental illness the worsening was experienced for about half of them also constant over time. The difference between respondents without and with mental illness was not statistically significant. Mental health worsened for all the respondents, but the worsening for respondents with mental illness were significantly more pronounced. Furthermore, they had before a lower level of mental health, increasing the gab in mental health. The worsening did for both groups decreased with time and individuals with former mental disorder recovered more. Results are seen in

Figure 1.

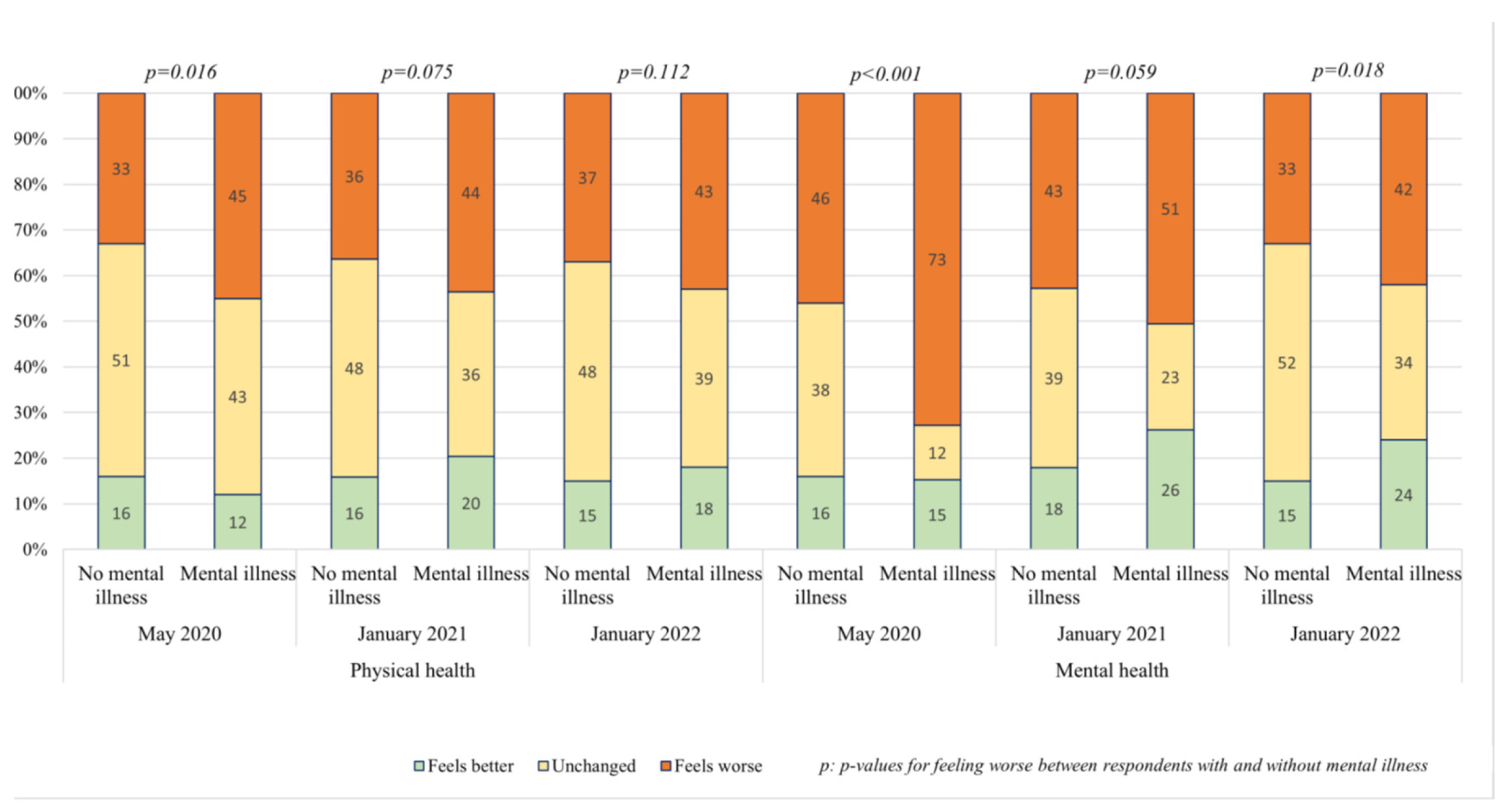

Stress was experienced worse of about half of the respondents in May 2020. The worsening decreased with time to one third in January 2022. There was no difference between respondents without and with mental illness. Boredom was a major problem in may concerning ¾ of respondents with mental illness and 2/3 without, a significant difference. It continued to be a major problem although decreasing with time and with no difference between the two groups. Loneliness was experienced worse in May of about ½ of the respondents without mental illness and 2/3 of them with mental illness, the difference not getting significant. It decreased with time for all respondents but less for the respondents with mental illness, so the difference became significant in the second and third sampling. Sleeping problems was experienced worse by about 1/3 of the respondents without mental illness of about half of them with mental illness and the difference was significant at all 3 time points. Results are seen in

Figure 2.

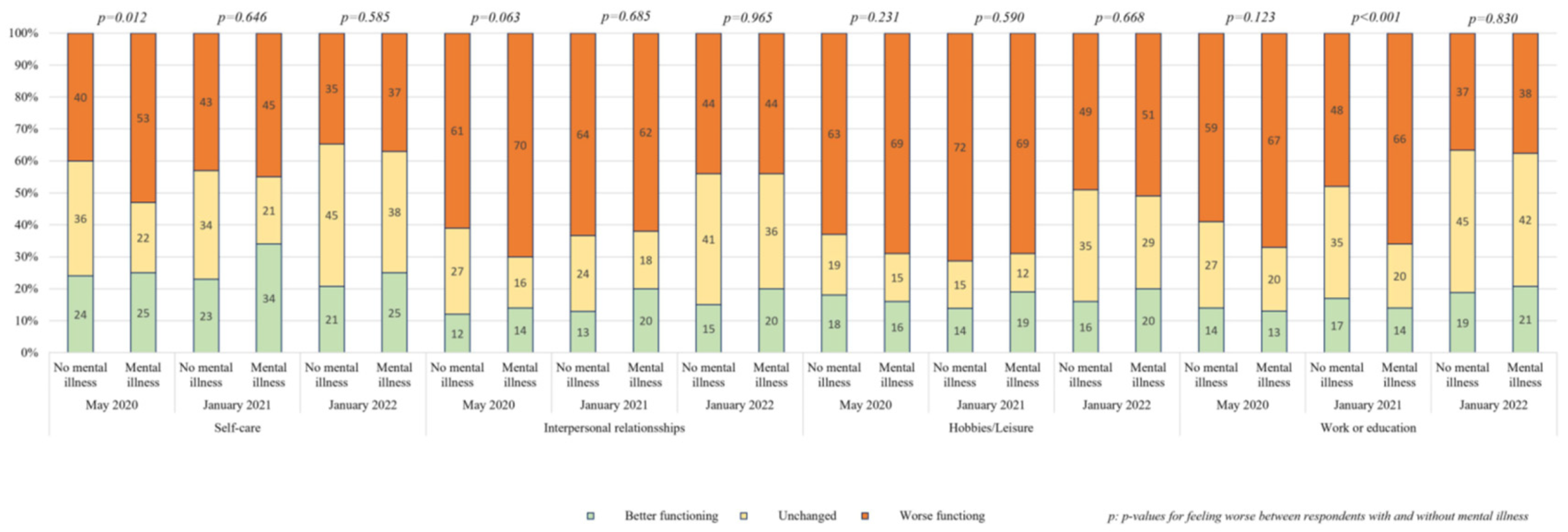

Functioning was estimated by changes in self-care, interpersonal relationships, hobbies/leisure and work/education. Of the 4 parameters self-care was least compromised for all with a worsening for about half of the respondents and little difference between respondents with and without mental illness. Only the sampling in may showed a significant difference. Interpersonal relationships and hobbies/leisure were showing a worsening for ½ to 2/3 of the respondents but no difference between those with and without mental illness. The parameter work/leisure showed a worsening for ½ to 2/3 of the respondents with little difference between the respondents with and without mental illness. Only the middle sampling in January 2021 showed an increased number of respondents with mental illness that reached significance. Results are seen in

Figure 3.

4. Discussion

During the COVID-19 pandemic, we assessed changes in mental and physical health, psychological distress and functioning over a two-year period in people with and without former mental illness.

Mental health decreased significantly more in respondents with former mental illness. Boredom was more pronounced in May 2020 in people with former mental illness and loneliness was significantly higher in January 2021. Sleep disturbance was more pronounced for respondents with former mental illness during the hole period.

There were for all parameters and for all respondents 10-20% who felt better during the pandemic. It was for stress extra pronounced with 1/3 feeling better.

That respondents without former mental illness felt negatively affected by the pandemic are in accordance with most of the reviews although some find a very small effect [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

8].

Greater worsening in mental health, compared to people without former mental health, in a population with mental illnesses is in accordance with some reviews [

7] but not with others [

2,

9]. The latter reviews find mixed results and often no or even positive effect from the pandemic. These results are explained by different theories i.e., the actual daily work stress experienced by people with mental illness was lessened because they could stay home and maybe some did not feel so isolated or lonely because families had to be more together.

Increase in psychological distress was seen especially in the form of sleeping problems and partly in loneliness with a more pronounced reaction for respondents with former mental illness as also found by others [

5,

6].

We found no overall difference in lowering of function between people with and without former mental illness in contrast to the review by Ahmed et al. (2023).

In Denmark, Pedersen et al. 2022 has reported that poorer mental health was seen under lockdowns and worse for people with former mental illness. Thygesen et al. 2021 found that there was a lowering in mental wellbeing during the pandemic, but it was small and most pronounced for people without former mental illness compared to people with former illness.

Our study has several strengths. The rapid collection of data in May 2020 enabled us to assess physical and mental health among a high number of Danes at a critical point in time. Combined with the two other survey waves we were able to assess influence on physical and mental health during the pandemic. Further, the study population included a high number of persons with preexisting mental illness (45%), which improved statistical power in the stratified analyses among persons with and without preexisting illness. Lastly, by retrieving a representative sample of Danish adults in January 2021 and January 2022, data collected in May 2020 could be weighted to represent the Danish adult population.

Some limitations also need to be addressed. The May 2020 survey may be influenced by self-selection bias, if individuals interested in the study objectives were more likely to participate. Recall bias may influence the results of physical and mental health prior to the pandemic, especially for the data collected in January 2021 and January 2022 but could be counteracted by the respondents only answering the simple question am I better, worse or unchanged. Furthermore, the categorization of mental illness was rather simple. Arguably applying a measure that covered a wide range of different diagnoses would have nuanced the findings.

5. Conclusions

We observed a negative influence on most people from the pandemic concerning physical and mental health, psychological distress, and functioning. Only for mental health and sleep the influence was more pronounced for people with former mental illness. Our findings agree with the varying results reported in the literature.

Funding

This work was supported by Trygfonden (grant number 151903). The funding organization had no influence on the design and conduct of the study, analysis, interpretation of results, preparation, or approval of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants of the Danish COH-FIT study that donated their time to this project during difficult times.

References

- Solmi M, Correll CU. The Collaborative Outcomes study on Health and Functioning during Infection Times in Adults (COH-FIT-Adults): Design and methods of an international online survey targeting physical and mental health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Affective Disorders 2021, 299, 1393–407. [CrossRef]

- Amed, N., Barnett, P., Greenburgh, A., Pemovska, T., Stefanidou, T., Lyons, N.,…Johnson, S. Mental health in Europe during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry 2023, 10, 537–56. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covid-19 Mental disorders collaborators. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2021, 398, 1700–1712.

- Salanti, G., Peter, N., Tonia, T., Holloway, A., White, I.R., Darwish, L.,…MHCOVID crowd investigators. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated control measures on mental health of the general population. Annals of internal medicine 2022. [CrossRef]

- Cénat, J.M., Farahi, S.M.M.M., Dalexis, R.D., Darius, W.P., Bekarkhanechi, F.M., Poisson, H.,…Labelle, P.R. The global evolution of mental health problems during the COVID.19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Journal of affective disorders 2022, 315, 70–95. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, M.M., Tasnim, S., Sultana, A., Faizah, F., Mozumder, H., Zou, L….Ma, P. Epidemiology of mental health problems in COVID-19: a review. F1000Research 2020, 9, 636–52. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam, S-H., Nam, J-H., Kwon, C-Y. Comparison of the Mental Health Impact of COVID-19 on vulnerable and non-vulnerable groups: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. International journal of environmental research and public health 2021, 18, 10830. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y., Wu, Y., Fan, S., Dal Santo, T., Li, L., Jiang, X.,…Thombs, B. Comparison of mental health symptoms before and during the covid-19 pandemic: evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis of 134 cohorts. BMJ 2023, 380, e074224.

- Kunzler, A.M., Lindner, S., Röthke, N., Schäfer, S.K., Metzendorf, M-I., Sachkova, A.,… Lieb, K. Mental health impact of early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic on individuals with pre-existing mental disorders: a systematic review of longitudinal research. International journal of environmental research and public health 2023, 20, 948. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, M.T., Andersen, T.O., Clotworthy, A., Jensen, A.K., Strandberg-Larsen, K., Rod, N.H., Varga, T.V. Time trends in mental health indicators during the initial 16 months of the COVID-19 pandemic in Denmark. BMC psychiatry 2022, 22, 25.

- Thygesen LC, Møller SP, Ersbøll AK, Santini ZI, Dahl Nielsen MB, Grønbæk MK, Ekholm, O. Decreasing mental well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal study among Danes before and during the pandemic. Journal of Psychiatric Research 2021, 144, 151–157. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).