Submitted:

03 June 2025

Posted:

04 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

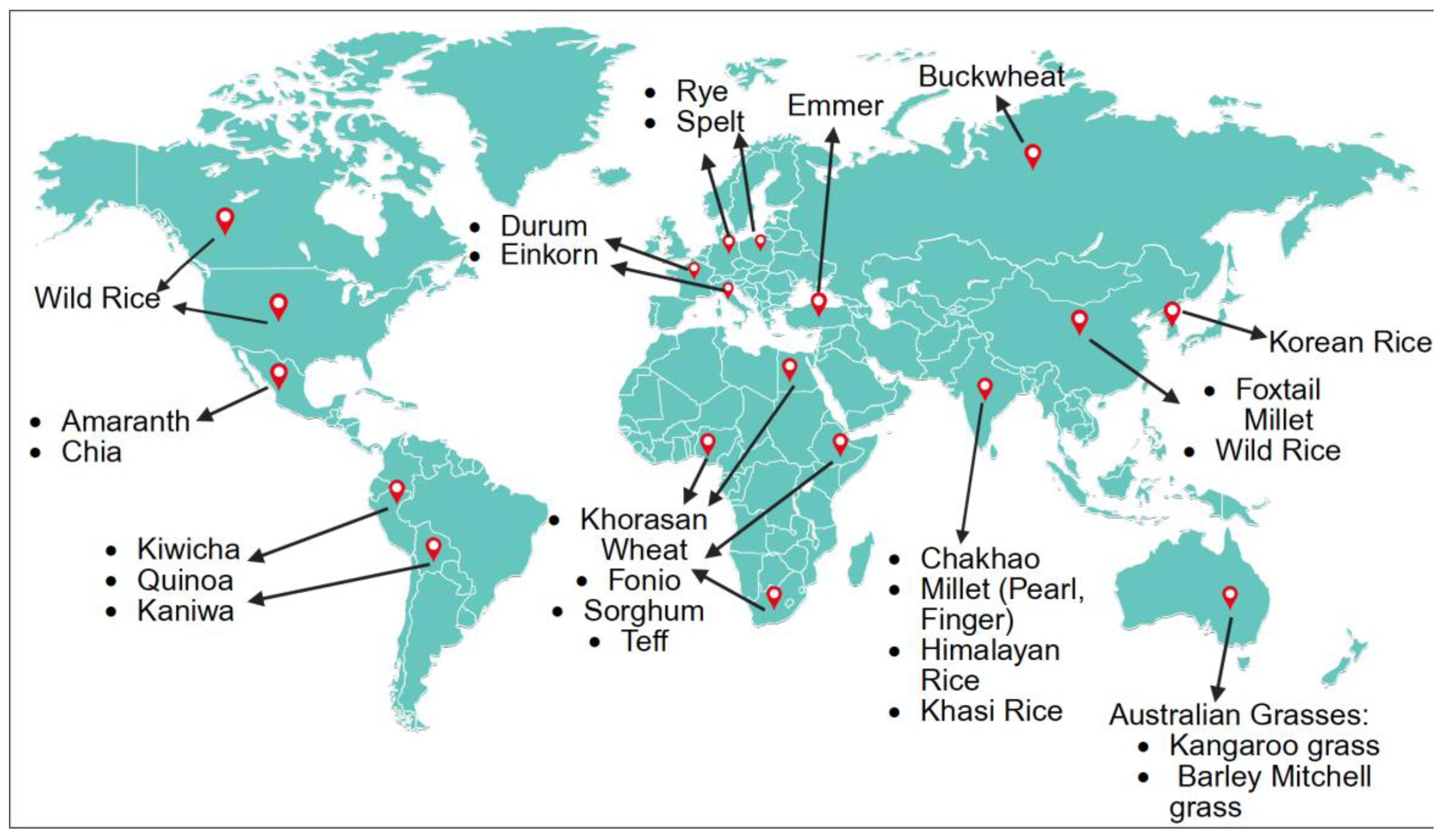

1. Introduction

2. Historical, Cultural, and Indigenous Significance

2.1. Traditional Uses in Diverse Cultures

2.2. Agricultural Resilience, Sustainability, and Food Sovereignty

3. Nutritional Value and Dietary Applications

3.1. Macronutrient and Micronutrient Composition

3.2. Dietary Fiber, Protein Quality, Low Glycemic Index

3.3. Role in Specialized Diets

3.4. Potential in Addressing Malnutrition and Diet-Related Chronic Diseases

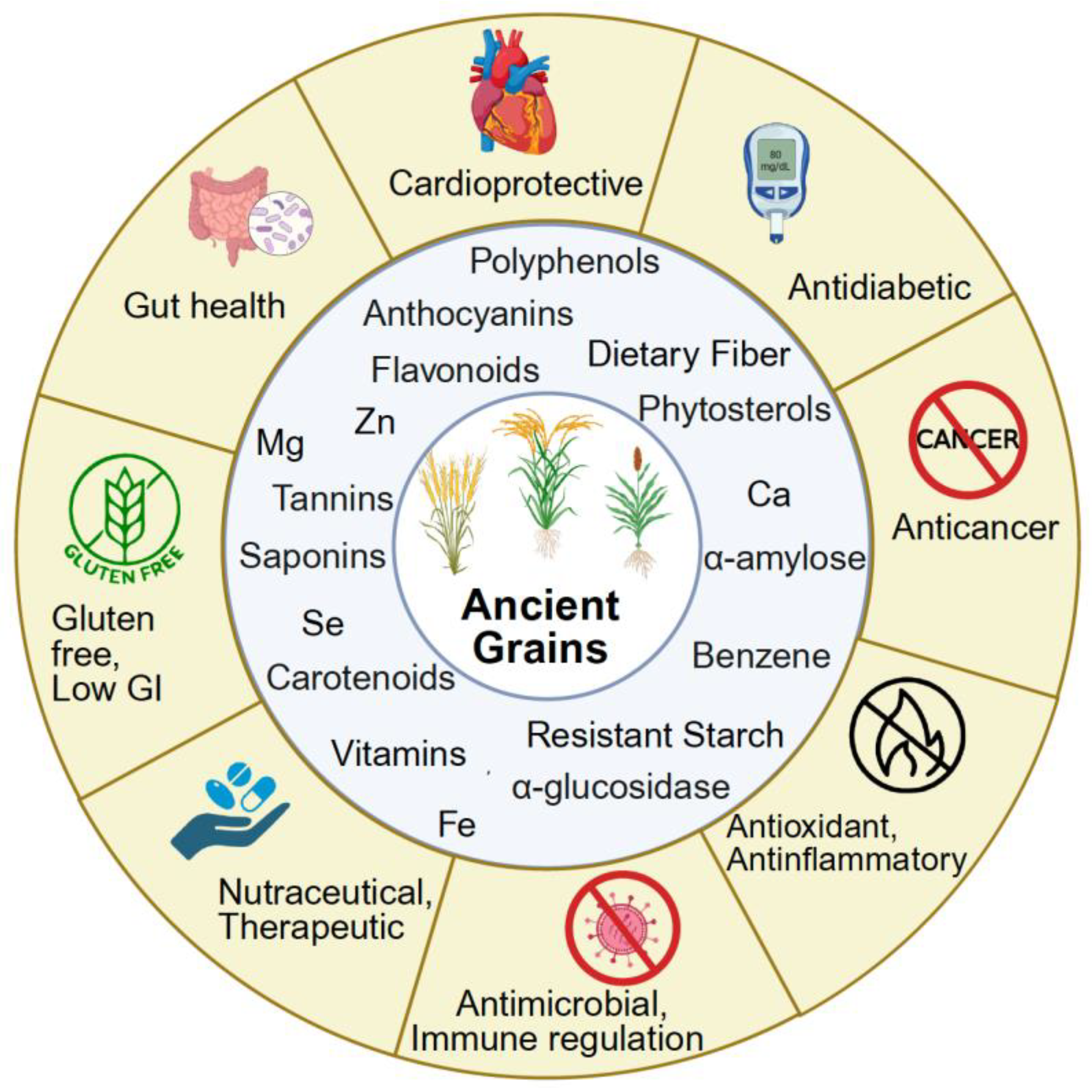

4. Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Potential

4.1. Phenolic Compounds, Flavonoids, Saponins, Phytosterols, and Other Bioactives

4.2. Antioxidant, Anti-inflammatory, and Immunomodulatory Properties

4.3. Health-Promoting Effects

5. Ancient Grains in Functional Food Development

5.1. Applications in Food Product Formulation

5.2. Challenges in Processing and Commercialization

5.3. Consumer Perceptions and Market Trends

5.4. Successful Product Innovations

6. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| FDA | U.S. Food and Drug Administration |

| GI | glycemic index |

| IL-6 | interleukin-6 |

| PPAR | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor |

| RNS | reactive nitrogen species |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| Zn, Fe, Ca | Zinc, iron, calcium |

References

- Longin, C.F.H.; Wurschum, T. Back to the Future - Tapping into Ancient Grains for Food Diversity. Trends Plant Sci. 2016, 21, 731–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, G.; Zeng, F.; Han, Z.; Qiu, C.W.; Zeng, M.; Yang, Z.; Xu, F.; Wu, D.; Deng, F.; et al. Molecular evidence for adaptive evolution of drought tolerance in wild cereals. New Phytol 2023, 237, 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, A. Review: Shaping a sustainable food future by rediscovering long-forgotten ancient grains. Plant Sci. 2018, 269, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragicevic, V.; Simic, M.; Kandic Raftery, V.; Vukadinovic, J.; Dodevska, M.; Durovic, S.; Brankov, M. Screening of Nutritionally Important Components in Standard and Ancient Cereals. Foods 2024, 13, 4116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majzoobi, M.; Jafarzadeh, S.; Teimouri, S.; Ghasemlou, M.; Hadidi, M.; Brennan, C.S. The Role of Ancient Grains in Alleviating Hunger and Malnutrition. Foods 2023, 12, 2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinu, M.; Whittaker, A.; Pagliai, G.; Benedettelli, S.; Sofi, F. Ancient wheat species and human health: Biochemical and clinical implications. J Nutr Biochem 2018, 52, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, S.; Kaur, G.; Kumari, A.; Ghosh, A.; Singh, G.; Bhardwaj, R.; Kumar, A.; Riar, A. Resurrecting forgotten crops: Food-based products from potential underutilized crops a path to nutritional security and diversity. Future Foods 2025, 11, 100585–100585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela Zamudio, F.; Rojas Herrera, R.; Segura Campos, M.R. Unlocking the potential of amaranth, chia, and quinoa to alleviate the food crisis: a review. Curr Opin Food Sci 2024, 57, 101149–101149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, K. Wild rice: the Indian's staple and the white man's delicacy. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 1981, 15, 281–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGilp, L.; Castell-Miller, C.; Haas, M.; Millas, R.; Kimball, J. Northern Wild Rice (Zizania palustris L.) breeding, genetics, and conservation. Crop Sci. 2023, 63, 1904–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Chu, M.; Chu, C.; Du, Y.; Shi, J.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, N. Wild rice (Zizania spp.): A review of its nutritional constituents, phytochemicals, antioxidant activities, and health-promoting effects. Food Chem. 2020, 331, 127293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ankita; Seth, U. Millets in India: exploring historical significance, cultural heritage and ethnic foods. J Ethn Foods 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, O.P.; Singh, D.V.; Kumari, V.; Prasad, M.; Seni, S.; Singh, R.K.; Sood, S.; Kant, L.; Rao, B.D.; Madhusudhana, R.; et al. Production and cultivation dynamics of millets in India. Crop Sci. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chyne, D.A.L.; Ananthan, R.; Longvah, T. Food compositional analysis of Indigenous foods consumed by the Khasi of Meghalaya, North-East India. J Food Compos Anal 2019, 77, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Morais Cardoso, L.; Pinheiro, S.S.; Martino, H.S.; Pinheiro-Sant'Ana, H.M. Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.): Nutrients, bioactive compounds, and potential impact on human health. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2017, 57, 372–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesa, H.; Tchuenchieu Kamgain, A.D.; Kwazi Zuma, M.; Mbhenyane, X. Knowledge, Perception and Consumption of Indigenous Foods in Gauteng Region, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melaku, T.A. Evaluation of Proximate Composition and Sensory Quality Acceptability of Ethiopian Flat Bread (Injera) Prepared from Composite Flour, Blend of Maize, Teff and Sorghum. Int J Food Eng Technol 2020, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neela, S.; Fanta, S.W. Injera (An Ethnic, Traditional Staple Food of Ethiopia): A review on Traditional Practice to Scientific Developments. J Ethn Foods 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orona-Tamayo, D.; Valverde, M.E.; Paredes-Lopez, O. Bioactive peptides from selected latin american food crops - A nutraceutical and molecular approach. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2019, 59, 1949–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, N.; Hussain, S.Z.; Naseer, B.; Bhat, T.A. Amaranth and quinoa as potential nutraceuticals: A review of anti-nutritional factors, health benefits and their applications in food, medicinal and cosmetic sectors. Food Chem X 2023, 18, 100687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavan, S.M.; Khadatkar, A.; Hasan, M.; Ahmad, D.; Kumar, V.; Jain, N.K. Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.): Paving the way towards nutraceuticals and value-added products for sustainable development and nutritional security. Appl Food Res 2025, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bencze, S.; Makádi, M.; Aranyos, T.J.; Földi, M.; Hertelendy, P.; Mikó, P.; Bosi, S.; Negri, L.; Drexler, D. Re-Introduction of Ancient Wheat Cultivars into Organic Agriculture—Emmer and Einkorn Cultivation Experiences under Marginal Conditions. Sustainability 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, E.; Prieto-Linde, M.L.; Larsson, H. Locally Adapted and Organically Grown Landrace and Ancient Spring Cereals-A Unique Source of Minerals in the Human Diet. Foods 2021, 10, 393–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poutanen, K.S.; Karlund, A.O.; Gomez-Gallego, C.; Johansson, D.P.; Scheers, N.M.; Marklinder, I.M.; Eriksen, A.K.; Silventoinen, P.C.; Nordlund, E.; Sozer, N.; et al. Grains - a major source of sustainable protein for health. Nutr. Rev. 2022, 80, 1648–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raheem, D.; Dayoub, M.; Birech, R.; Nakiyemba, A. The Contribution of Cereal Grains to Food Security and Sustainability in Africa: Potential Application of UAV in Ghana, Nigeria, Uganda, and Namibia. Urban Sci 2021, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapfumo, P.; Mtambanengwe, F.; Chikowo, R. Building on indigenous knowledge to strengthen the capacity of smallholder farming communities to adapt to climate change and variability in southern Africa. Clim Dev 2015, 8, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angioloni, A.; Collar, C. Nutritional and functional added value of oat, Kamut, spelt, rye and buckwheat versus common wheat in breadmaking. J Sci Food Agric 2011, 91, 1283–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mougiou, N.; Didos, S.; Bouzouka, I.; Theodorakopoulou, A.; Kornaros, M.; Mylonas, I.; Argiriou, A. Valorizing Traditional Greek Wheat Varieties: Phylogenetic Profile and Biochemical Analysis of Their Nutritional Value. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2703–2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repo-Carrasco-Valencia, R.; Acevedo de La Cruz, A.; Icochea Alvarez, J.C.; Kallio, H. Chemical and functional characterization of Kaniwa (Chenopodium pallidicaule) grain, extrudate and bran. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2009, 64, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valli, V.; Taccari, A.; Di Nunzio, M.; Danesi, F.; Bordoni, A. Health benefits of ancient grains. Comparison among bread made with ancient, heritage and modern grain flours in human cultured cells. Food Res Int 2018, 107, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.D.; Yan, N.; Du, Y.M.; Liang, H.; Zhang, Z.F.; Yuan, X.L. Consumption of Wild Rice (Zizania latifolia) Prevents Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease through the Modulation of the Gut Microbiota in Mice Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhai, C.K.; Lu, C.M.; Zhang, X.Q.; Sun, G.J.; Lorenz, K.J. Comparative Study on Nutritional Value of Chinese and North American Wild Rice. J Food Compos Anal 2001, 14, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, D.K.; Srivastav, P.P. Proximate Composition, Mineral Content and Fatty Acids Analyses of Aromatic and Non-Aromatic Indian Rice. Rice Sci 2017, 24, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Arevalo, J.; Laar, A.; Chaparro, M.P.; Drewnowski, A. Nutrient-Dense African Indigenous Vegetables and Grains in the FAO Food Composition Table for Western Africa (WAFCT) Identified Using Nutrient-Rich Food (NRF) Scores. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2985–2985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, J.; Benkendorff, K.; Liu, L.; Luke, H. The nutritional composition of Australian native grains used by First Nations people and their re-emergence for human health and sustainable food systems. Front Sustain Food Syst 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Francesco, A.; Cunsolo, V.; Saletti, R.; Svensson, B.; Muccilli, V.; De Vita, P.; Foti, S. Quantitative Label-Free Comparison of the Metabolic Protein Fraction in Old and Modern Italian Wheat Genotypes by a Shotgun Approach. Molecules 2021, 26, 2596–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, D.; Kantamraju, P.; Jha, S.; Sundarrao, G.S.; Bhowmik, A.; Chakdar, H.; Mandal, S.; Sahana, N.; Roy, B.; Bhattacharya, P.M.; et al. Evaluation of indigenous aromatic rice cultivars from sub-Himalayan Terai region of India for nutritional attributes and blast resistance. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, F.M.; Riar, C.S. Effect of composition, granular morphology and crystalline structure on the pasting, textural, thermal and sensory characteristics of traditional rice cultivars. Food Chem. 2019, 280, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pour, T.; Binge, H.; Cross, R.; Moore, K.; Pattison, A.; Brand-Miller, J.; Atkinson, F.; Bell-Anderson, K. Australian native grain reduces blood glucose response and Glycemic Index. Proc Nutr Soc 2024, 83, E48–E48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repo-Carrasco-Valencia, R.; Basilio-Atencio, J.; Luna-Mercado, G.I.; Pilco-Quesada, S.; Vidaurre-Ruiz, J. Andean Ancient Grains: Nutritional Value and Novel Uses. 2022.

- Van Boxstael, F.; Aerts, H.; Linssen, S.; Latre, J.; Christiaens, A.; Haesaert, G.; Dierickx, I.; Brusselle, J.; De Keyzer, W. A comparison of the nutritional value of Einkorn, Emmer, Khorasan and modern wheat: whole grains, processed in bread, and population-level intake implications. J Sci Food Agric 2020, 100, 4108–4118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magi, C.E.; Rasero, L.; Mannucci, E.; Bonaccorsi, G.; Ranaldi, F.; Pazzagli, L.; Faraoni, P.; Mulinacci, N.; Bambi, S.; Longobucco, Y.; et al. Use of ancient grains for the management of diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2024, 34, 1110–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ms Wolever, T.; Rahn, M.; Dioum, E.; Spruill, S.E.; Ezatagha, A.; Campbell, J.E.; Jenkins, A.L.; Chu, Y. An Oat beta-Glucan Beverage Reduces LDL Cholesterol and Cardiovascular Disease Risk in Men and Women with Borderline High Cholesterol: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial. J Nutr 2021, 151, 2655–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sereni, A.; Cesari, F.; Gori, A.M.; Maggini, N.; Marcucci, R.; Casini, A.; Sofi, F. Cardiovascular benefits from ancient grain bread consumption: findings from a double-blinded randomized crossover intervention trial. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2017, 68, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Repo-Carrasco-Valencia, R.; Hellström, J.K.; Pihlava, J.M.; Mattila, P.H. Flavonoids and other phenolic compounds in Andean indigenous grains: Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa), kañiwa (Chenopodium pallidicaule) and kiwicha (Amaranthus caudatus). Food Chem. 2010, 120, 128–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madadi, E.; Mazloum-Ravasan, S.; Yu, J.S.; Ha, J.W.; Hamishehkar, H.; Kim, K.H. Therapeutic Application of Betalains: A Review. Plants (Basel) 2020, 9, 1219–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, A.; Lim, M.J.; Kim, N.H.; Barathikannan, K.; Vijayalakshmi, S.; Elahi, F.; Ham, H.J.; Oh, D.H. Quantification of Amino Acids, Phenolic Compounds Profiling from Nine Rice Varieties and Their Antioxidant Potential. Antioxidants (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunthonkun, P.; Palajai, R.; Somboon, P.; Suan, C.L.; Ungsurangsri, M.; Soontorngun, N. Life-span extension by pigmented rice bran in the model yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 18061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, Y.; Cai, S.; Xiong, Q. Metabolomics Reveals Antioxidant Metabolites in Colored Rice Grains. Metabolites 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodape, A.; Kodape, A.; Desai, R. Rice bran: Nutritional value, health benefits, and global implications for aflatoxin mitigation, cancer, diabetes, and diarrhea prevention. Food Chem. 2025, 464, 141749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udhaya Nandhini, D.; Venkatesan, S.; Senthilraja, K.; Janaki, P.; Prabha, B.; Sangamithra, S.; Vaishnavi, S.J.; Meena, S.; Balakrishnan, N.; Raveendran, M.; et al. Metabolomic analysis for disclosing nutritional and therapeutic prospective of traditional rice cultivars of Cauvery deltaic region, India. Front Nutr 2023, 10, 1254624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.Y.; Kim, H.W.; Jang, H.H.; Hwang, Y.J.; Choe, J.S.; Lim, Y.; Kim, J.B.; Lee, Y.H. gamma-Oryzanol-Rich Black Rice Bran Extract Enhances the Innate Immune Response. J. Med. Food 2017, 20, 855–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A.; Rein, D.; Schafer, A.; Monnard, I.; Gremaud, G.; Lambelet, P.; Bertoli, C. Similar cholesterol-lowering properties of rice bran oil, with varied gamma-oryzanol, in mildly hypercholesterolemic men. Eur. J. Nutr. 2005, 44, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, S.; Primiterra, M.; Tagliamonte, M.C.; Carnevali, A.; Gianotti, A.; Bordoni, A.; Canestrari, F. Counteraction of oxidative damage in the rat liver by an ancient grain (Kamut brand khorasan wheat). Nutrition 2012, 28, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surendiran, G.; Alsaif, M.; Kapourchali, F.R.; Moghadasian, M.H. Nutritional constituents and health benefits of wild rice (Zizania spp.). Nutr. Rev. 2014, 72, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surendiran, G.; Goh, C.; Le, K.; Zhao, Z.; Askarian, F.; Othman, R.; Nicholson, T.; Moghadasian, P.; Wang, Y.J.; Aliani, M.; et al. Wild rice (Zizania palustris L.) prevents atherogenesis in LDL receptor knockout mice. Atherosclerosis 2013, 230, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadasian, M.H.; Alsaif, M.; Le, K.; Gangadaran, S.; Masisi, K.; Beta, T.; Shen, G.X. Combination effects of wild rice and phytosterols on prevention of atherosclerosis in LDL receptor knockout mice. J Nutr Biochem 2016, 33, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadasian, M.H.; Kaur, R.; Kostal, K.; Joshi, A.A.; Molaei, M.; Le, K.; Fischer, G.; Bonomini, F.; Favero, G.; Rezzani, R.; et al. Anti-Atherosclerotic Properties of Wild Rice in Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor Knockout Mice: The Gut Microbiome, Cytokines, and Metabolomics Study. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadasian, M.H.; Zhao, R.; Ghazawwi, N.; Le, K.; Apea-Bah, F.B.; Beta, T.; Shen, G.X. Inhibitory Effects of North American Wild Rice on Monocyte Adhesion and Inflammatory Modulators in Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor-Knockout Mice. J Agric Food Chem 2017, 65, 9054–9060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Zhang, H.; Qin, L.; Zhai, C. Effects of dietary carbohydrate replaced with wild rice (Zizania latifolia (Griseb) Turcz) on insulin resistance in rats fed with a high-fat/cholesterol diet. Nutrients 2013, 5, 552–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Zhai, L.; Tang, Q.; Ren, J.; Zhou, S.; Wang, H.; Yun, Y.; Yang, Q.; Yan, X.; Xing, F.; et al. Comparative Metabolic Profiling of Different Colored Rice Grains Reveals the Distribution of Major Active Compounds and Key Secondary Metabolites in Green Rice. Foods 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melini, V.; Acquistucci, R. Health-Promoting Compounds in Pigmented Thai and Wild Rice. Foods 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sik, B.; Lakatos, E.; Márkus, A.; Székelyhidi, R. Determination of the health-protective effect of ancient cereals and one possibility of increasing their functionality. Cereal Res Commun 2023, 52, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Miao, L. Consumer perception of clean food labels. Br. Food J. 2022, 125, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairuddin, M.A.N.; Lasekan, O. Gluten-Free Cereal Products and Beverages: A Review of Their Health Benefits in the Last Five Years. Foods 2021, 10, 2523–2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroccio, A.; Celano, G.; Cottone, C.; Di Sclafani, G.; Vannini, L.; D'Alcamo, A.; Vacca, M.; Calabrese, F.M.; Mansueto, P.; Soresi, M.; et al. WHOLE-meal ancient wheat-based diet: Effect on metabolic parameters and microbiota. Dig. Liver Dis. 2021, 53, 1412–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badia-Olmos, C.; Sanchez-Garcia, J.; Laguna, L.; Zuniga, E.; Monika Haros, C.; Maria Andres, A.; Tarrega, A. Flours from fermented lentil and quinoa grains as ingredients with new techno-functional properties. Food Res Int 2024, 177, 113915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifky, M.; Dissanayake, K.; Maksumova, D.; Shosalimova, S.; Shokirov, A.; Jesfar, M.; Zokirov, K.; Samadiy, M. Incorporation of barley and corn flour as a functional ingredients in bakery products: Review. E3S Web of Conf. 2024, 537, 10024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, M.; Bashir, O.; Amin, T.; Wani, A.W.; Shams, R.; Chaudhary, K.S.; Mirza, A.A.; Manzoor, S. A comprehensive review on functional beverages from cereal grains-characterization of nutraceutical potential, processing technologies and product types. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Zhang, P.; Warner, R.D.; Shen, S.; Fang, Z. Cereal grain-based functional beverages: from cereal grain bioactive phytochemicals to beverage processing technologies, health benefits and product features. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2022, 62, 2404–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalampopoulos, D.; Wang, R.; Pandiella, S.S.; Webb, C. Application of cereals and cereal components in functional foods: a review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2002, 79, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, P.; Petrov, K. Lactic Acid Fermentation of Cereals and Pseudocereals: Ancient Nutritional Biotechnologies with Modern Applications. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollan, G.C.; Gerez, C.L.; LeBlanc, J.G. Lactic Fermentation as a Strategy to Improve the Nutritional and Functional Values of Pseudocereals. Front Nutr 2019, 6, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyedeji, A.B.; Wu, J. Food-based uses of brewers spent grains: Current applications and future possibilities. Food Biosci 2023, 54, 102774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukid, F.; Folloni, S.; Sforza, S.; Vittadini, E.; Prandi, B. Current Trends in Ancient Grains-Based Foodstuffs: Insights into Nutritional Aspects and Technological Applications. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2018, 17, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefoska-Needham, A.; Tapsell, L. Considerations for progressing a mainstream position for sorghum, a potentially sustainable cereal crop, for food product innovation pipelines. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 97, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, L.A.; Cobos, A.; Diaz, O.; Aguilera, J.M. Chia Seed (Salvia hispanica): An Ancient Grain and a New Functional Food. Food Rev. Int. 2013, 29, 394–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhu, F.; Li, G. Beverages developed from pseudocereals (quinoa, buckwheat, and amaranth): Nutritional and functional properties. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2025, 24, e70081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acheampong, R.; Osei Tutu, C.; Amissah, J.G.N.; Danquah, A.O.; Saalia, F.K. Physicochemical and sensory characteristics of a breakfast cereal made from sprouted finger millet-maize composite flour. Cogent Food Agric 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, H.; Kumar, A.; Amin, T.; Bhat, T.A.; Aziz, N.; Rasane, P.; Ercisli, S.; Singh, J. Process optimization, growth kinetics, and antioxidant activity of germinated buckwheat and amaranth-based yogurt mimic. Food Chem. 2024, 457, 140138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudra, S.G.; Jakhar, N.; Nishad, J.; Saini, N.; Sen, S.; Bhardhwaj, R.; Jaiswal, S.; Suneja, P.; Singh, S.; Kaur, C. Extrusion Conditions and Antioxidant Properties of Sorghum, Barley and Horse Gram Based Snack. Vegetos 2015, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajagopalan, V.R.; Manickam, S.; Muthurajan, R. A Comparative Metabolomic Analysis Reveals the Nutritional and Therapeutic Potential of Grains of the Traditional Rice Variety Mappillai Samba. Plants (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, Y.; Liu, Q.; Beta, T. Antioxidant activity of commercial wild rice and identification of flavonoid compounds in active fractions. J Agric Food Chem 2009, 57, 7543–7551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemzadeh, A.; Karbalaii, M.T.; Jaafar, H.Z.E.; Rahmat, A. Phytochemical constituents, antioxidant activity, and antiproliferative properties of black, red, and brown rice bran. Chem. Cent. J. 2018, 12, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisetkomolmat, J.; Arjin, C.; Satsook, A.; Seel-Audom, M.; Ruksiriwanich, W.; Prom, U.T.C.; Sringarm, K. Comparative Analysis of Nutritional Components and Phytochemical Attributes of Selected Thai Rice Bran. Front Nutr 2022, 9, 833730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Grain Type | Notable Nutrients/Bioactives | Documented/Proposed Health Benefits | Selected References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Red and Pigmented Rice (e.g., Mappillai Samba, Chakhao, YZ6H) | Phenolic acids, flavonoids, tocopherols, phytosterols, squalene, anthocyanins, vitamins, minerals | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antihypercholesterolemic, neuroprotective | [37,49,82] |

| Wild Rice (Zizania spp.) | Protein, fiber, vitamins B/E, minerals (Fe, Zn, Mg), phenolics, phytosterols, γ-oryzanol | Anti-atherogenic, antidiabetic, hypocholesterolemic, metabolic and gut health benefits | [56,58,60,83] |

| Australian Native Grains | Protein, polyunsaturated fatty acids, phenolics, Ca, Fe, Zn, Mg | Glycemic control, cardiovascular and metabolic health, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory | [35,39] |

| Indigenous and Aromatic Rice (India, Khasi, Himalaya) | Protein, resistant starch, fiber, iron, zinc, phenolics, aroma compounds | Low GI, antioxidant, digestive and metabolic benefits, ethnomedicinal value | [14,33,38] |

| Thai and Korean Pigmented Rice Bran | Anthocyanins, flavonoids, tocopherols, γ-oryzanol, fatty acids | Antioxidant, anti-obesity, antidiabetic, immune-modulatory | [47,84,85] |

| Teff, Fonio, Sorghum, Pearl Millet (African Grains) | Iron, zinc, calcium, vitamin A, B12, fiber, polyphenols | Combat malnutrition, manage NCDs, promote dietary diversity and food security | [16,34] |

| Kañiwa, Quinoa, Kiwicha (Andean Grains) | Protein, essential amino acids, fiber, phenolics, flavonoids, betalains | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, colon health | [29,45] |

| Ancient Wheats (Einkorn, Emmer, Khorasan, Spelt) | Protein, fiber, polyphenols, minerals (Zn, Fe, Mg), MUFA, tocopherols | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, gut health, higher nutritional density than modern wheat | [28,30,41] |

| Oats, Buckwheat, Rye | β-glucans, resistant starch, phenolics, minerals | Glycemic control, cholesterol-lowering, antioxidant and cardiovascular health | [27] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).