1. Introduction

Vitamin C (L-ascorbic acid, AA), well-known for its antioxidant properties, has been shown to function as a pro-oxidant in cancer cells, inducing cytotoxicity when delivered in large amounts [

1,

2,

3]. The anti-cancer properties of AA reportedly involve the inhibition of cell growth and proliferation via the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and hydrogen peroxide-mediated mechanisms [

4,

5,

6,

7]. ROS induces oxidative stress and cellular damage depending on the metabolic circumstances and redox status of cancer cells [

8,

9]. The half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) of vitamin C varies between cancerous and healthy cells, resulting in selective cytotoxicity. Normal cells exhibit an EC50 exceeding 20 mM for vitamin C, whereas cancer cells have an EC50 of 1-10 mM, a dose that can be administered intravenously [

1,

10]. The anti-cancer potential of high-dose vitamin C has been extensively explored in several cancer types in vitro, in vivo, and in clinical trials [

2,

3,

11,

12,

13,

14].

Linus Pauling and Ewan Cameron first recognized the potential of vitamin C as a cancer therapeutic agent in 1976 and demonstrated that high-dose vitamin C therapy could prolong the survival of patients with cancer [

15,

16]. Nevertheless, a subsequent study conducted at the Mayo Clinic reported that vitamin C did not induce any notable beneficial effects in patients with cancer [

17,

18]. This discrepancy could be explained by sodium-dependent vitamin C transporter family 2 (SVCT2), which regulates AA intake and may play an important role in determining the efficacy of high-dose vitamin C therapy [

19,

20,

21]. A study exploring the hormetic proliferation responses of colorectal cancer cell lines to vitamin C found that high doses of vitamin C could exert anti-cancer effects. However, in cells with low SVCT2 expression, low-dose vitamin C enhanced cancer cell activity. Conversely, all vitamin C doses induced cancer cell death in cell lines with high SVCT2 expression [

22]. These findings highlight the need to improve vitamin C transport to enhance its therapeutic efficacy. Increasing SVCT2 expression may be crucial for enhancing the effects of high-dose vitamin C therapy, considering the heterogeneity in SVCT2 expression among patients.

Valproic acid (VPA), a short-chain fatty acid and class I histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor, has traditionally been used to treat epilepsy and other neurological disorders [

23,

24,

25]. The anti-cancer properties of VPA have also been examined in a wide range of cancer types, including ovarian, breast, pancreatic, lung, prostate, oral, and colorectal cancers, in vitro, in vivo, and in clinical trials [

10,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. VPA has been shown to inhibit tumor growth by altering the expression of genes belonging to the HDAC family [

27,

33]. VPA reportedly suppresses the expression of class I HDAC, resulting in the upregulation of p21, a tumor suppressor, and the acetylation and activation of p53 and p65. This, in turn, leads to the stimulation of apoptosis in liver cancer cells and the prevention of cancer cell proliferation, migration, and invasion [

34]. VPA-induced histone hyperacetylation was shown to be associated with growth inhibition and programmed cell death. Furthermore, VPA regulated the expression of critical cell-cycle and apoptotic regulators, resulting in caspase activation [

35]. Interestingly, VPA promoted SVCT2 expression by regulating HDAC2 expression in a neuronal cell line and in the mouse brain [

36].

Increasing SVCT2 expression in low-SVCT2-expressing cancer cells is crucial for improving the efficacy of high-dose vitamin C therapy, given that SVCT2 levels are highly associated with anti-cancer activity. In the current study, we examined the anti-cancer effects of VPA and vitamin C and showed that VPA enhanced the anti-cancer effects of vitamin C by upregulating SVCT2 expression. This resulted in enhanced AA uptake, increased ROS generation, and induction of apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells expressing low levels of SVCT2, i.e., HCT-116 and DLD-1, compared with vitamin C treatment alone (without VPA). In a mouse xenograft model, we found that co-treatment with vitamin C and VPA significantly reduced tumor growth. These results suggest that VPA may function as an SVCT2 inducer, providing a promising avenue for future investigations into its potential role in enhancing high-dose vitamin C therapy in patients with cancer exhibiting low SVCT2 expression.

2. Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Reagents

Human colorectal cell lines with low SVCT2 expression, HCT-116 and DLD-1, were purchased from the Korean Cell Line Bank (KCLB). Cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with L-glutamine (CM059-050; GenDEPOT, Baker, USA), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, Massachusetts, USA), and 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution (SV30010; Hyclone, Utah, USA). MC38, a mouse colorectal cancer cell line, was procured from the National Cancer Center (Korea), cultured in DMEM high glucose, 4.0 mM L-glutamine, sodium pyruvate (CM002-050; GenDEPOT, Baker, USA), 10% FBS, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. Vitamin C and AA were purchased from Huons Biopharma (Gyeonggi-do, South Korea); VPA was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Cell Viability Assay

Cell viability was measured using the D-Plus™ CCK cell viability assay kit (Dongin Biotech Co., Ltd., Seoul, South Korea). In brief, cells (1 × 104/well) were seeded and cultured in 96-well plates for 24 h. Subsequently, cells were treated with vitamin C and VPA in RPMI-1640 medium with L-glutamine with 5% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution for 48 h at 37°C and under 5% CO2. The cells were washed with Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS; LB001-02; Gyeongsangbuk-do, Republic of Korea). To measure cell viability, 10 μL of the CCK-8 solution in 90 μL DPBS was added to each well; cells were incubated at 37°C under 5% CO2 for 1 h. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Epoch, California, USA).

Crystal Violet Assay

To examine the anti-cancer effects, the crystal violet assay was performed based on stained cells attached to cell culture plates. In brief, cells (6 × 105/well) were seeded, cultured in 6-well plates, and incubated for 24 h. Next, cells were treated with vitamin C and VPA in RPMI-1640 medium with L-glutamine, 5% FBS, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution for 48 h at 37°C under 5% CO2. The cells were stained with 0.5% crystal violet staining solution, and the plate was then placed on a shaker at room temperature and incubated for 30 min. Subsequently, the staining solution was removed, the cells were washed with distilled water, the plate was reversed on the bench and air dried at room temperature, and the stained cells were observed. The amount of crystal violet staining was directly proportional to the cell biomass attached to the plate.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR) Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from the cells using the TRI reagent (TR118; Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH, USA) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. RNA concentrations were determined by measuring the absorbance at 260 nm. cDNA was synthesized using the CellScript cDNA Master Mix (CDS-200; Cellsafe, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. qPCR was performed using TB Green Premix Ex Taq (TaKaRa, Otsu, Shinga, Japan). Data were analyzed using the Rotor-Gene O series software (version 2.3.1; Qiagen). The following genes were amplified using the indicated primer sequences, hSVCT2: forward 5′-TCTTTGTG CTTGGATTTTCGAT-3′ and reverse 5′-ACGTTCAACACTTGATCGATTC-3′; mSVCT2: forward 5′-AACGGCAGAGCTGTTGGA-3′ and reverse 5′-GAAAATCGTCAGCATGGCAA-3′; hβ-actin: forward 5′-CATCC TGCGTCTGGACCT-3′ and reverse 5′-TAATGTCACGCA CGATTTCC-3′; and mβ-actin: forward 5′-ATCCTCTTCCTCCCTGGA-3′ and reverse 5′-TTCATGGATGCCACAGGA-3′.

Western Blotting

Proteins were extracted from the cells and tissue from the mice using the Pro-Prep Protein Extraction Kit containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (17081; iNtRON, Sungnam, Korea). Protein concentrations were measured using the Bradford Protein Assay Plus Kit (P7200-050; GenDepot, Baker, USA). In total, 25 mg of protein was heat-denatured in the sample buffer for 10 min. Protein samples were loaded onto 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5% skimmed milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST) at room temperature for 2 h. Subsequently, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-SVCT2 (1:500) (A6740; ABclonal, Wuhan, China), anti-p21 (1:2500) (bs-10129R; Bioss, Beijing, China), anti-caspase-3 (1:2500) (#9662S; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), and anti-beta-actin (1:2000) (NB600-501; Novus biologics) antibodies. After four washes with Tris-buffered saline (0.10% Tween 20), the membranes were incubated with secondary anti-rabbit antibodies for 2 h at room temperature. After additional washing with TBST, immune-reactive bands were detected using West-Q Pico Dura ECL Solution (W3653; GenDEPOT, TX, USA) and visualized using the iBright™ CL1500 Imaging System (Invitrogen, Massachusetts, USA).

AA Uptake

Cells were harvested incubation with VPA for 48 h and AA for 4 h. A commercially available ascorbic acid kit (ab65346; Abcam, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to determine the intracellular AA concentration. In this assay, a proprietary catalyst oxidizes AA to produce products interacting with the AA probe, thereby generating color. The color developed within 3 min and was stable for 1 h. Absorbance was measured at 570 nm (Epoch, California, USA). The reaction mixture was prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions. AA concentrations in the cells were analyzed compared to AA standard curve as described in the kit, and the equation ‘concentration = As/Sv’ (where As is the AA amount determined from the standard curve and Sv is the sample volume added to the sample wells) was used as suggested in the kit description.

Detection of ROS Generation

ROS formation was assessed by fluorescence microscopy using a DCFDA /H2DCFDA-Cellular ROS Assay Kit (Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, the cells were seeded in 24-well plates at a density of 6 × 104 cells per well in RPMI-1640 medium with L-glutamine, 5% FBS, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution, followed by overnight incubation at 37°C and under 5% CO2. Subsequently, the cells were treated with 1 mM VPA for 48 h. Then, cells were stained with 20 μM dichloro-dihydro-fluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) for 30 min at 37°C. The cells were treated with 0.5 mM vitamin C for 4 h. After treatment, the cells were trypsinized using trypsin-EDTA (1×) and 0.25% (CA014-010; GenDEPOT, TX, USA) and washed twice with DPBS. ROS production was detected by flow cytometry (Navios Flow Cytometer, Beckman Coulter Life Sciences, USA). DCF was excited using a 488 nm laser and detected at 535 nm (FL1). Flow cytometry data were analyzed using the Kaluza Analysis Software (Beckman Coulter, Indianapolis, IN, USA).

Apoptosis Assay

For apoptosis detection, flow cytometry was performed using BD Pharmingen™ FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit I (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. In brief, cells were seeded at a density of 6 × 105 cells/well in 6 well plates. Then, cells were treated with vitamin C and VPA in RPMI-1640 media with L-glutamine, 5% FBS, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution for 48 h at 37°C and under 5% CO2. The cells were trypsinized with trypsin-EDTA, washed twice with DPBS, resuspended in 1× binding buffer, and stained with Annexin V and propidium iodide. Following incubation for 15 min at room temperature in the dark, the samples were immediately analyzed using flow cytometry (Navios Flow Cytometer, Beckman Coulter Life Sciences, USA).

Knockdown of SVCT2 Activity Using Lentivirus

shRNA oligonucleotide design, lentiviral particle production, and target cell infection were performed as described on the Addgene website (

https://www.addgene.org/ protocols/plko/). Target gene knockdown sequences for shSVCT2 and scramble control were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich.

Briefly, HCT-116 cells were seeded in RPMI-1640 medium containing L-glutamine, 5% FBS, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution at 37°C under 5% CO2. Upon reaching 50% confluency, cells were infected with lentiviral particles in the presence of 8 μg/mL polybrene (sc-134220; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Forty-eight hours post-transfection, cells were selected using a growth medium containing 2 μg/mL puromycin (ant-pr-1; InvivoGen, California, United States) to establish stably transfected cell lines. Western blot analysis was performed to determine the efficiency of shSVCT2 knockdown.

Animal Experiment

Six-week-old male C57BL6 mice were purchased from Dae Han Bio (Link Co., Ltd., Chungbuk, Korea). Mice were maintained in a pathogen-free environment at 24°C for under a 12 h/12 h light-dark cycle. The Administrative Panel of the Laboratory Animal Research Center at Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine approved this study (Approval Number: SKKUIACUC2023-04-26-1). To determine the anti-cancer effects in vivo, 1 × 10

6 MC38 cells were administered subcutaneously into the dorsal surface of mice to establish a subcutaneous xenograft tumor mouse model. The tumor volume was measured using calipers and determined using the following formula: tumor volume = (length) × (width) × 0.5. In model mice, the tumor volume ranged between 20 and 30 mm

3. Vitamin C (4 g/kg) [

11] and VPA (200 mg/kg body weight) [

36] were prepared in 200 μL of DPBS. Vitamin C was administered via intraperitoneal injection every 2 days, and VPA was administered by intraperitoneal injection daily for 14 days. The relative tumor volume (RTV) was calculated as follows: RTV = Tumor volume on the measured day / tumor volume on day 0. The tumor volumes were measured, and the percentage of tumor growth inhibition (%TGI) was calculated as follows: %TGI = [1 – (RTV treatment group / RTV control group)] × 100.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Results are presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance was determined using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey–Kramer multiple comparison test. Differences were considered statically significant at * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001.

3. Results

3.1. Vitamin C and VPA Exert Synergistic Anti-Cancer Effects

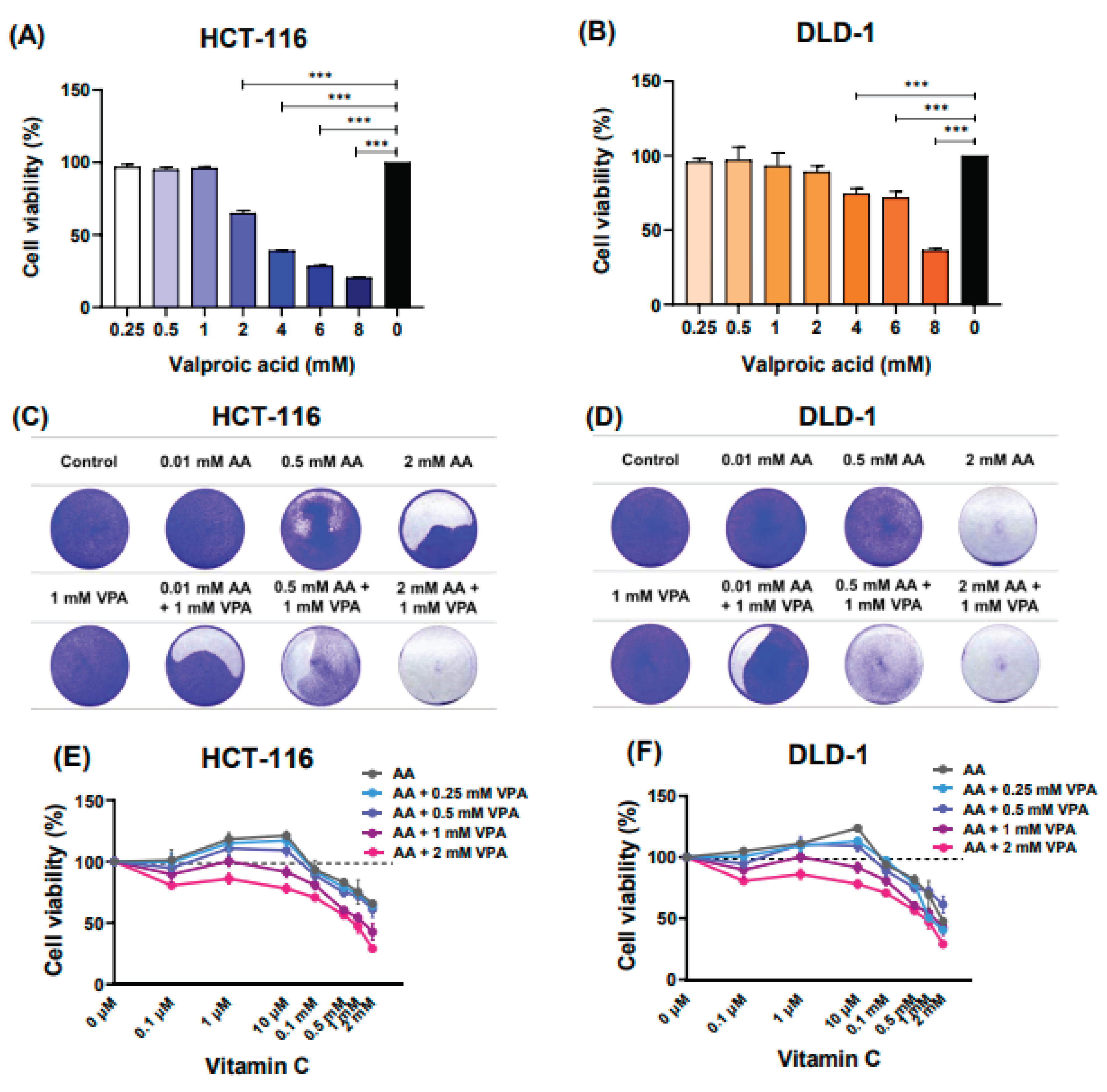

To determine the cytotoxic effects of VPA on HCT-116 and DLD-1 cells, the cells were treated with different VPA doses (0.25‒8 mM) for 48 h. Subsequently, cell viability was evaluated using the CCK-8 assay. Herein, treatment with 0.25–1 mM VPA did not induce cytotoxicity in HCT-116 cells (Figure 1A). Likewise, treatment with 0.25–2 mM VPA did not induce cytotoxicity in DLD-1 cells (Figure 1B). Next, cells were co-treated with varying concentrations of AA (0.1 μM‒2 mM) and VPA (1 mM) for 48 h, followed by crystal violet staining. In both human colorectal cancer cell lines, co-treatment with AA and VPA exerted a synergistic anti-cancer effect, especially when 1 mM VPA was combined with low doses of vitamin C (0.01 and 0.5 mM) (Figure 1C–1D). Additionally, co-treatment with AA and VPA suppressed the hormetic dose-response effect of vitamin C. Upon treatment with gradient concentrations of AA (0.1 μM‒2 mM) alone, we found that high doses of AA (> 1 mM) reduced cell viability, whereas low doses (< 0.5 mM) promoted cancer cell growth in both cell lines. Conversely, co-treatment with low-dose AA and VPA reduced cell viability compared with AA treatment alone. In addition, co-treatment with high doses of AA and VPA decreased viability in both cell lines (Figure 1E–1F). Collectively, these findings revealed that VPA could suppress the hormetic dose response of vitamin C in the low-SVCT2-expressing cell lines HCT-116 and DLD-1.

Figure 1.

Vitamin C and VPA exert synergistic anti-cancer effects. The cytotoxic effects of VPA were assessed on HCT-116 and DLD-1 cells (A, B). Co-treatment with AA and VPA for 48 h enhanced the anti-cancer effects of AA. Crystal violet staining assays were conducted following the co-treatment in both cell lines (C, D). VPA could suppress the hormetic dose response of vitamin C in the low-SVCT2-expressing cell lines HCT-116 and DLD-1 (E, F).

Figure 1.

Vitamin C and VPA exert synergistic anti-cancer effects. The cytotoxic effects of VPA were assessed on HCT-116 and DLD-1 cells (A, B). Co-treatment with AA and VPA for 48 h enhanced the anti-cancer effects of AA. Crystal violet staining assays were conducted following the co-treatment in both cell lines (C, D). VPA could suppress the hormetic dose response of vitamin C in the low-SVCT2-expressing cell lines HCT-116 and DLD-1 (E, F).

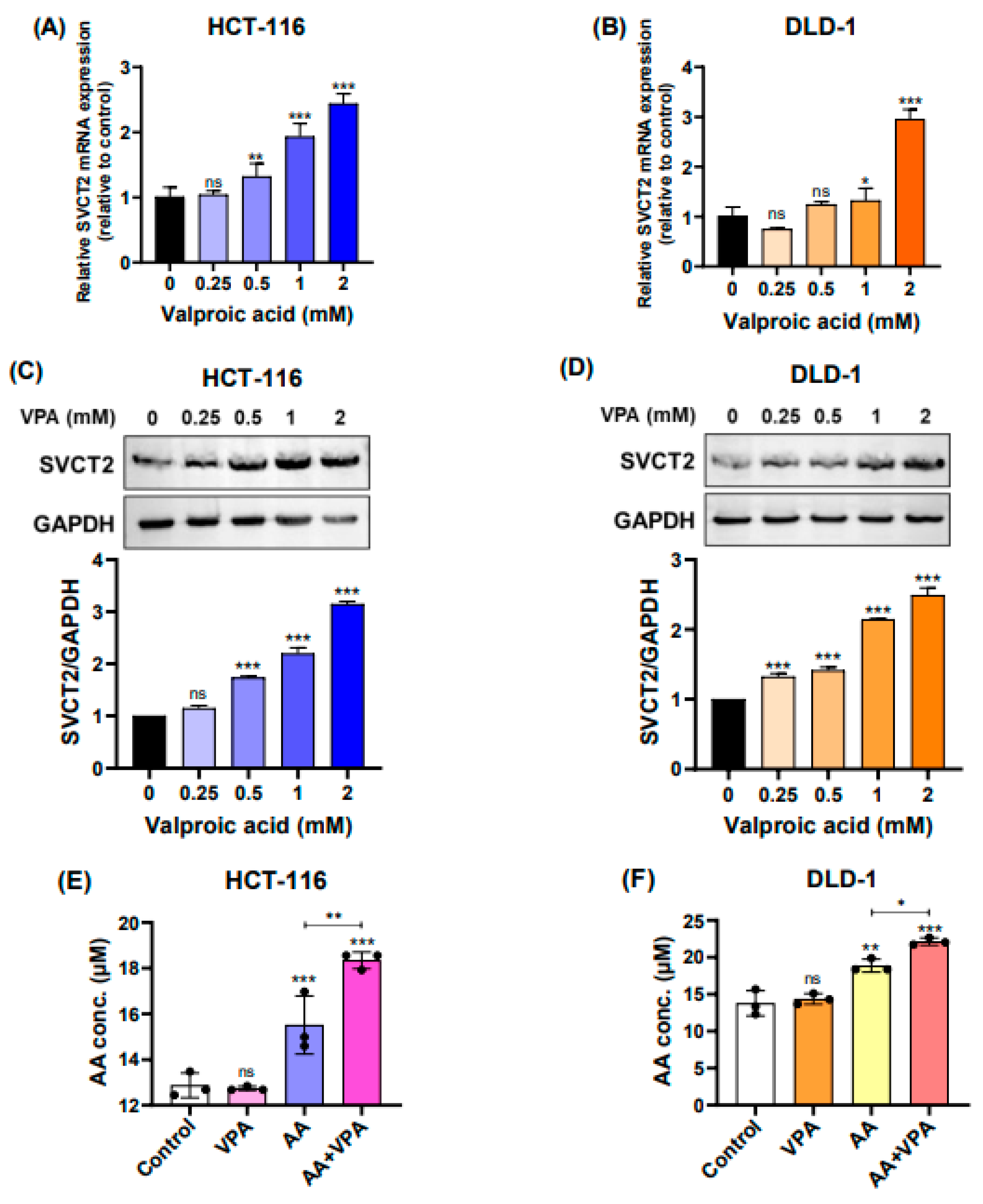

3.2. VPA Upregulates SVCT2 Expression and Induces Vitamin C Uptake in Colorectal Cancer Cell Lines

In the current study, we treated HCT-116 and DLD-1 cells, both low SVCT2-expressing colorectal cancer cell lines, with VPA (0.25‒2 mM) for 48 h and determined the expression levels of the SVCT2 gene and protein. According to the qPCR results, SVCT2 mRNA expression was increased in both HCT-116 and DLD-1 cells in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 2A–2B). Similarly, western blot analysis revealed that VPA treatment enhanced SVCT2 protein levels in both cell lines in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 2C–2D). To elucidate the role of SVCT2 in vitamin C transport, both cell lines were treated with 1 mM VPA for 48 h, followed by treatment with 0.5 mM AA for 4 h. An ascorbic acid assay kit (Abcam) was used to evaluate the intracellular AA concentrations.

Figure 2.

VPA upregulates SVCT2 expression and induces vitamin C uptake in colorectal cancer cell lines. The cells were treated with VPA for 48 h in HCT-116 and DLD-1 cells. SVCT2 mRNA expression was determined using qPCR (A, B). The expression of the SVCT2 protein was analyzed using western blotting (C, D). Both cell lines were treated with VPA for 48 h, followed by treatment with AA for 4 h to evaluate the intracellular AA concentrations (E, F).

Figure 2.

VPA upregulates SVCT2 expression and induces vitamin C uptake in colorectal cancer cell lines. The cells were treated with VPA for 48 h in HCT-116 and DLD-1 cells. SVCT2 mRNA expression was determined using qPCR (A, B). The expression of the SVCT2 protein was analyzed using western blotting (C, D). Both cell lines were treated with VPA for 48 h, followed by treatment with AA for 4 h to evaluate the intracellular AA concentrations (E, F).

In both HCT-116 and DLD-1 cells, co-treatment with AA and VPA significantly increased intracellular AA levels compared with AA treatment alone (Figure 2E–2F). Accordingly, treatment with VPA increased SVCT2 expression, which induced vitamin C uptake in HCT-116 and DLD-1 colorectal cancer cell lines with low SVCT2 expression.

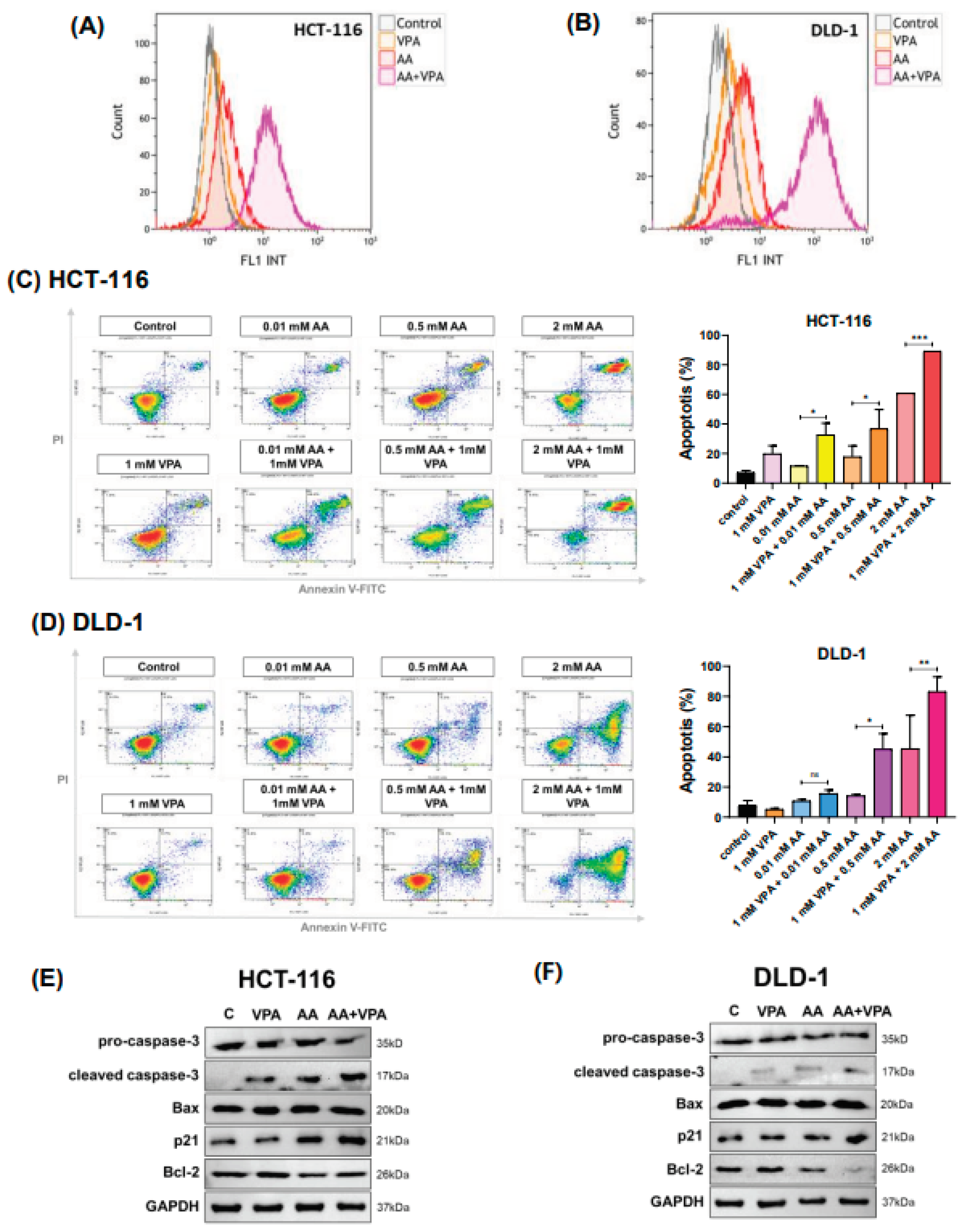

3.3. Co-Treatment with AA and VPA Induces ROS Generation and Increases Apoptotic Response

In cancer cells, high levels of vitamin C can induce ROS production, damaging cancer cells and exhibiting anti-cancer properties. After labeling cells with DCFDA, ROS production was measured using flow cytometry. In both HCT-116 and DLD-1 cells, co-treatment with 0.5 mM AA and 1 mM VPA induced greater ROS production than treatment with either AA or VPA alone (Figure 3A–3B).

Figure 3.

Co-treatment with AA and VPA induces ROS generation and increases apoptotic response. ROS generation was measured by flow cytometer after the cells were co-treated with AA and VPA in HCT-116 and DLD-1 cells (A, B). Cell apoptosis was investigated in both cell lines after the co-treatment using a flow cytometer with Annexin V and PI labeling (C, D), and the expression of apoptosis-related proteins was performed by western blotting (E, F).

Figure 3.

Co-treatment with AA and VPA induces ROS generation and increases apoptotic response. ROS generation was measured by flow cytometer after the cells were co-treated with AA and VPA in HCT-116 and DLD-1 cells (A, B). Cell apoptosis was investigated in both cell lines after the co-treatment using a flow cytometer with Annexin V and PI labeling (C, D), and the expression of apoptosis-related proteins was performed by western blotting (E, F).

To measure cell apoptosis, cells were stained with Annexin V and propidium iodide and subjected to flow cytometry analysis. Compared with treatment with AA or VPA alone, co-treatment with AA and VPA increased the percentage of apoptotic cells in a concentration-dependent manner in both HCT-116 and DLD-1 cells (Figure 3C–3D). In HCT-116 cells, co-treatment with VPA and AA increased the apoptotic rate by approximately 2.8 folds at 0.01 mM AA, 2 folds at 0.5 mM AA, and 1.5 folds at 2 mM AA, compared with AA treatment alone. In DLD-1 cells, co-treatment with AA and VPA (0.5 mM) enhanced the apoptotic rate by approximately 2.8 times, while co-treatment with 2 mM AA and VPA increased the apoptotic rate by 1.8 times when compared with AA treatment alone. To demonstrate the apoptotic response induced by co-treatment with AA and VPA, western blot analysis was performed to detect the expression of apoptosis-related proteins. Compared with treatment with either AA or VPA alone, co-treatment with 0.5 mM AA and 1 mM VPA enhanced the levels of cleaved caspase-3, Bax, and p21 proteins while decreasing those of pro-caspase-3 and Bcl-2 in both cell lines (Figure 3E–3F). Taken together, these results suggested that VPA could enhance the anti-cancer effects of AA in the low SVCT2-expressing colorectal cancer cell lines HCT-116 and DLD-1 by stimulating ROS production and inducing cell death.

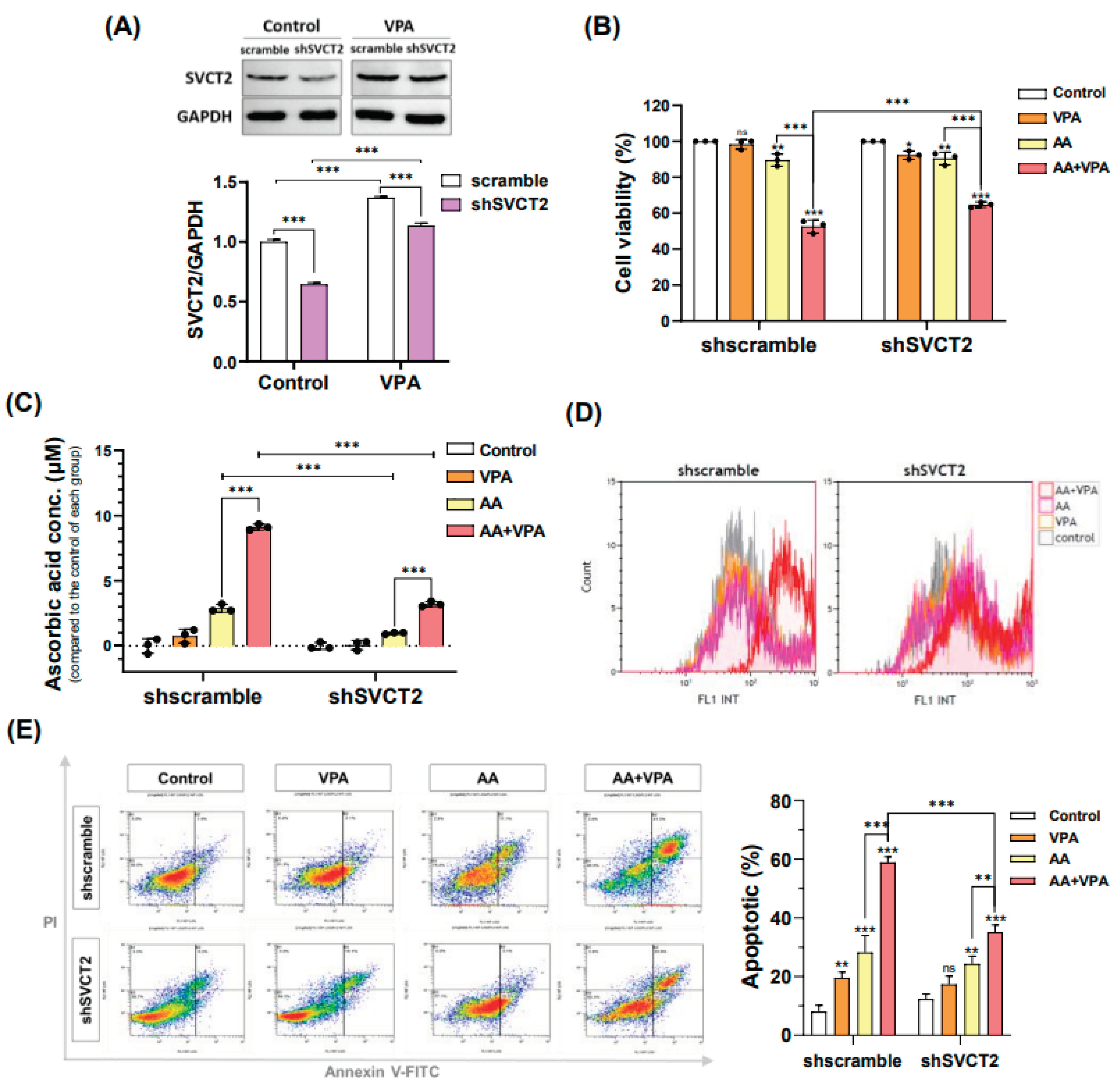

3.4. VPA Induces SVCT2 Expression in SVCT2-Knockdown HCT-116 Colorectal Cancer Cells

VPA reportedly exerts anti-cancer effects against several types of cancer cells, including the colorectal cancer cell lines HCT-116 and DLD-1 (Figure 1A–B). VPA concentrations ≥ 2 mM markedly decreased cell viability in both cancer cells. In addition, AA exhibited anti-cancer properties at high doses. In the current study, our findings indicated that VPA and AA exerted synergistic anti-cancer effects both in vitro and in vivo. To determine whether

Figure 4.

VPA induces SVCT2 expression in SVCT2-knockdown HCT-116 colorectal cancer cells. VPA was treated in the HCT-116 shSVCT2 cells for 48 h, and SVCT2 protein expression was examined by western blotting (A). The cells were co-treated with AA and VPA to determine the synergistic anti-cancer effects (B), intracellular AA concentrations (C), ROS generation analysis (D), and apoptosis analysis in HCT-116 the shSVCT2 cells (E).

Figure 4.

VPA induces SVCT2 expression in SVCT2-knockdown HCT-116 colorectal cancer cells. VPA was treated in the HCT-116 shSVCT2 cells for 48 h, and SVCT2 protein expression was examined by western blotting (A). The cells were co-treated with AA and VPA to determine the synergistic anti-cancer effects (B), intracellular AA concentrations (C), ROS generation analysis (D), and apoptosis analysis in HCT-116 the shSVCT2 cells (E).

VPA enhances the anti-cancer effects of AA by upregulating the expression of SVCT2, HCT-116 cells were infected with lentiviral particles containing shSVCT2 or shscramble control. HCT-116 shSVCT2 cells treated with 1 mM VPA for 48 h exhibited significant upregulation of SVCT2 expression when compared with untreated HCT-116 shSVCT2 cells (Figure 5A). Moreover, in HCT-116 shSVCT2 cells, co-treatment with 0.5 mM AA and 1 mM VPA significantly decreased the anti-cancer effect (Figure 5B), reduced intracellular AA uptake (Figure 5C), diminished ROS generation (Figure 5D), and lowered apoptotic rates (Figure 5E) when compared with shscramble control cells. These findings suggested that the anti-cancer activity of AA is dependent on SVCT2 expression levels and that VPA could enhance this effect by upregulating SVCT2 expression in HCT-116 colorectal cancer cells.

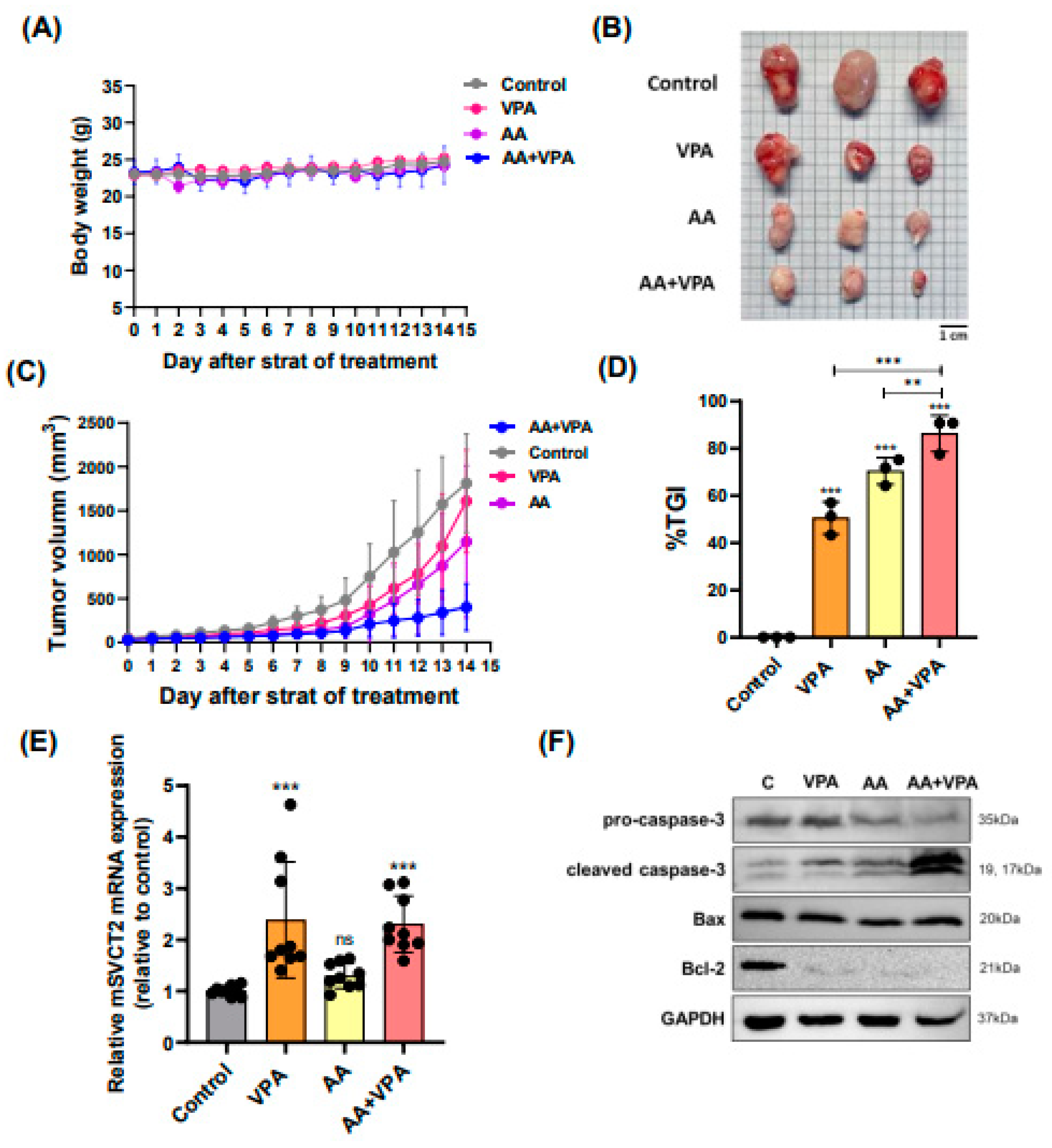

Figure 5.

VPA upregulates SVCT2 expression in mouse organs, and co-treatment with AA and VPA exerts an anti-tumor effect in mouse xenograft model. Mice were administered VPA via intraperitoneal injection for 14 days. mSVCT2 protein expression in mouse organs was investigated by western blotting (A). The anti-tumor effect of co-administration with AA and VPA was measured in the mouse xenograft model, AA was administered every 2 days for 14 days and VPA was daily administered for 14 days. The mice were daily measured for body weight (g) (B) and tumor volume (mm³) (D). After administering, we observed tumor size (E). And tumor growth inhibition ratio (%TGI) was analyzed for all the treatment groups (F).

Figure 5.

VPA upregulates SVCT2 expression in mouse organs, and co-treatment with AA and VPA exerts an anti-tumor effect in mouse xenograft model. Mice were administered VPA via intraperitoneal injection for 14 days. mSVCT2 protein expression in mouse organs was investigated by western blotting (A). The anti-tumor effect of co-administration with AA and VPA was measured in the mouse xenograft model, AA was administered every 2 days for 14 days and VPA was daily administered for 14 days. The mice were daily measured for body weight (g) (B) and tumor volume (mm³) (D). After administering, we observed tumor size (E). And tumor growth inhibition ratio (%TGI) was analyzed for all the treatment groups (F).

3.5. VPA Upregulates SVCT2 Expression in Mouse Organs, and Co-Treatment with AA and VPA Exerts an Anti-Tumor Effect in Mouse Xenograft Model

To evaluate the antitumor effects of co-treatment with AA and VPA in a mouse xenograft model, AA was administered via intraperitoneal injection every 2 days for 14 days (4 g/kg body weight), whereas VPA (200 mg/kg body weight) was administered daily via intraperitoneal injection for 14 days. There were no significant changes in body weight across all the groups (Figure 6A). Furthermore, co-treatment with AA and VPA significantly reduced the tumor volume (mm3), tumor size, and %TGI, tumor size compared with AA or VPA treatment alone (Figure 6B–6D). Treatment with VPA and co-treatment with AA and VPA increased mSVCT2 gene expression in the tumor 2.3 times compared to the control group (Figure 6E). In addition, co-treatment with AA and VPA enhanced the expression of apoptosis-related proteins, including cleaved caspase-3 and Bax. In contrast, co-treatment with AA and VPA reduced the levels of Bcl-2 and pro-caspase-3 within the tumor compared with AA or VPA treatment alone (Figure 6F).

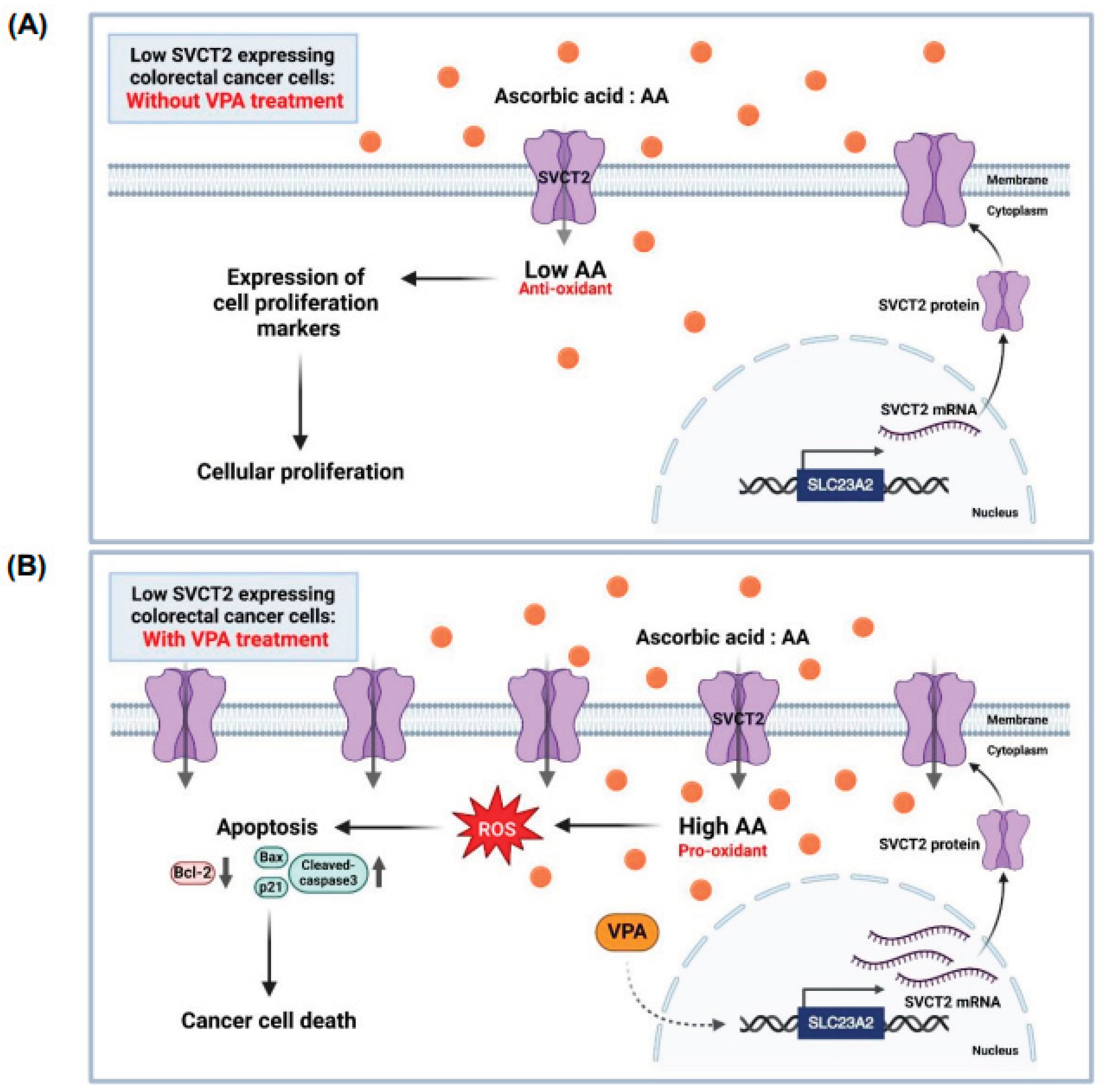

Figure 6.

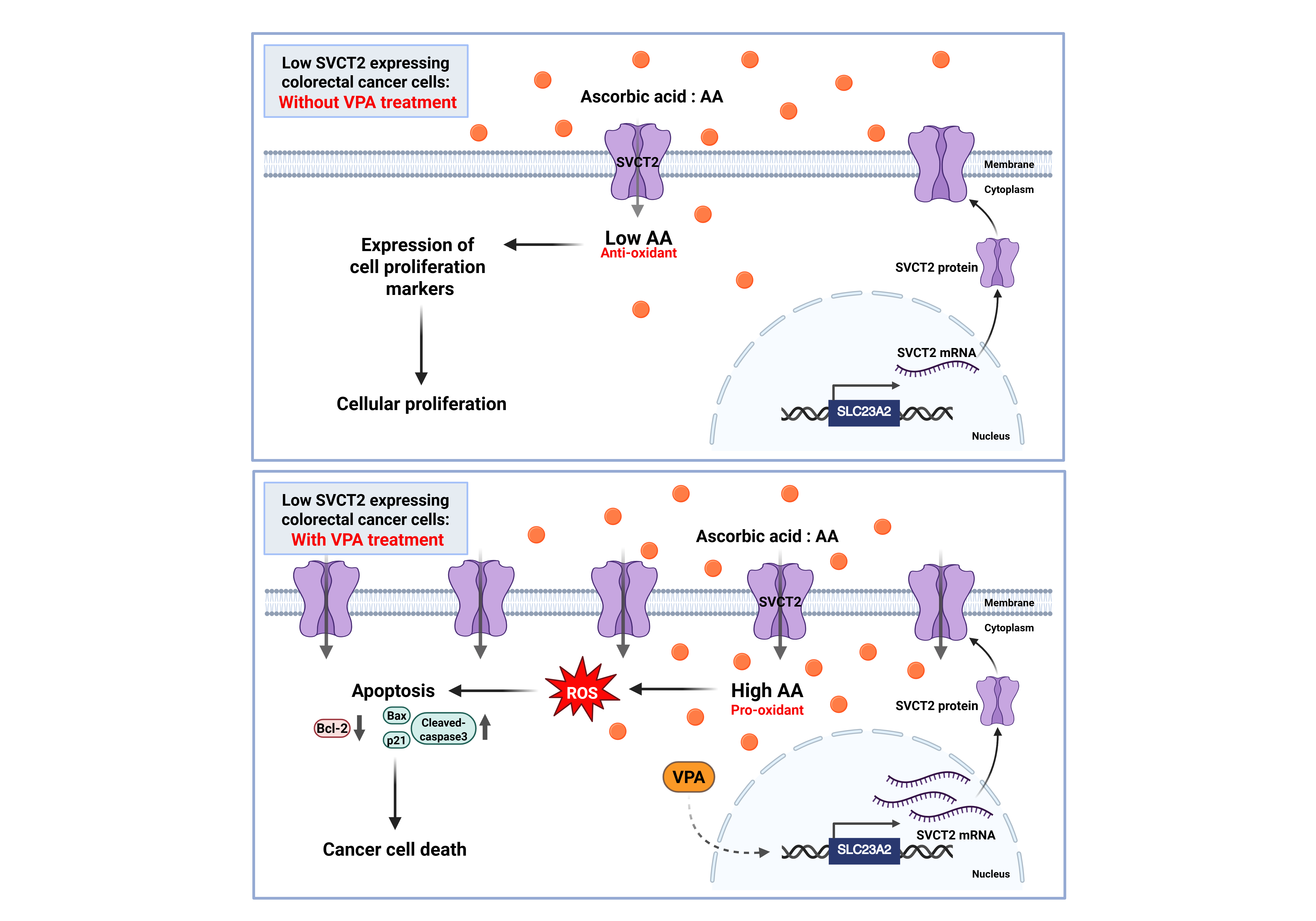

The proposed role of AA and VPA in the anti-cancer effects involves the induction of SVCT expression. AA treatment in low SVCT2-expressing colorectal cancer without VPA treatment. At low intracellular concentrations, AA functions primarily as an antioxidant, promoting cellular proliferation and supporting the growth of cancer cells (A). In contrast, AA treatment in low SVCT2-expressing colorectal cancer with VPA treatment. VPA enhances SVCT2 expression, leading to increased intracellular uptake of AA. This elevated concentration shifts AA’s role to that of a pro-oxidant, triggering ROS generation, inducing apoptosis, and ultimately promoting cancer cell death (B).

Figure 6.

The proposed role of AA and VPA in the anti-cancer effects involves the induction of SVCT expression. AA treatment in low SVCT2-expressing colorectal cancer without VPA treatment. At low intracellular concentrations, AA functions primarily as an antioxidant, promoting cellular proliferation and supporting the growth of cancer cells (A). In contrast, AA treatment in low SVCT2-expressing colorectal cancer with VPA treatment. VPA enhances SVCT2 expression, leading to increased intracellular uptake of AA. This elevated concentration shifts AA’s role to that of a pro-oxidant, triggering ROS generation, inducing apoptosis, and ultimately promoting cancer cell death (B).

4. Discussion

High-dose vitamin C therapy may exert anti-cancer effects by acting as a pro-oxidant and inducing reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation in cancer cells. The efficacy of this therapy depends on the expression of SVCT2 in cancer cells or patients with cancer [

11,

22,

34,

38,

39]. SVCT2 is a key protein transporter responsible for the intracellular uptake of AA, regulating intracellular vitamin C levels [

11,

19,

20]. In colorectal cancer cell lines with high-SVCT2 expression, both low and high doses of vitamin C were reported to reduce cell viability. High-dose vitamin C (> 1 mM) could exert an anti-cancer effect in low-SVCT2-expressing colorectal cancer cell lines, whereas treatment with low-dose vitamin C (< 10 μM) has been shown to promote cancer cell proliferation [

22]. These findings suggest that SVCT2 expression in cancer cells plays a role in improving the therapeutic effects of high-dose vitamin C anti-cancer therapy. Herein, we aimed to identify an inducer capable of upregulating SVCT2 expression, thereby promoting high-dose intracellular vitamin C uptake in low-SVCT2-expressing cancer cells to achieve enhanced anti-cancer effects.

In human breast cancer cell lines, AA treatment combined with magnesium supplementation was found to be a more effective anti-cancer therapy than AA treatment alone, specifically by inhibiting the hormetic response of vitamin C at low doses. Although magnesium supplementation improved the functional activity of SVCT2, it failed to upregulate SVCT2 expression [

11]. VPA reportedly induces vitamin C uptake by decreasing HDAC2 levels, which, in turn, increases SVCT2 mRNA and protein expression. This regulation correlates with the YY-1 transcription factor, which promotes SLC23A2 promoter activity in a neural model [

36]. Additionally, VPA could reportedly suppress cancer cell proliferation in various cancer types by affecting the activity of HDAC, thereby inducing apoptosis and cell cycle arrest [

35,

40,

41,

42]. Clinical trials and animal model studies have examined the therapeutic potential of VPA in a range of cancers. VPA alone and in combination with other chemotherapeutic agents has exhibited notable anti-cancer effects [

40,

43,

44]. For example, VPA increased the expression of genes involved in tumor differentiation and progression regulated by the ERK-AP-1 pathway, including growth-associated protein-43 (GAP-43) and Bcl-2 [

45]. Additionally, VPA inhibited the growth of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells by upregulating p21 and inducing G0/G1 cell cycle arrest [

46]. In a human ovarian cancer cell line (OVCAR-3), VPA reduced cell proliferation by downregulating genes responsible for G1-to-S phase transition while upregulating those involved in G1 phase arrest [

47].

To the best of our knowledge, there are no reports exploring the stimulation of SVCT2 expression by VPA alone or in combination with vitamin C in cancer cells. In the current study, we found that co-treatment with AA and VPA exerted anti-cancer effects by upregulating SVCT2 expression in low SVCT2-expressing colorectal cancer cell lines. Cho et al. 2018 [

22] examined SVCT2 expression in various colorectal cancer cell lines, revealing that HCT-116 and DLD-1 cells exhibited low SVCT2 expression. We evaluated the anti-cancer effects of AA and VPA in two colorectal cancer cell lines with low levels of SVCT2 expression. Our data revealed that VPA stimulated the expression of the SVCT2 gene and protein in a concentration-dependent manner in both HCT-116 and DLD-1 colorectal cancer cells. Co-treatment with AA and VPA substantially enhanced intracellular AA uptake in both cell lines compared with AA treatment alone. Additionally, co-treatment with AA and VPA promoted apoptosis and increased ROS generation in both cancer cell lines. Co-treatment with AA and VPA also enhanced the expression of apoptotic proteins cleaved caspase-3, Bax, and p21 while suppressing those of the anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and pro-caspase-3. Moreover, co-treatment with AA and VPA exerted a greater anti-cancer effect than AA or VPA alone. Notably, co-treatment with low-dose vitamin C and VPA reduced cancer cell viability in both cell lines. Furthermore, co-treatment with AA and VPA suppressed the hormetic proliferation response to vitamin C in both the low-SVCT2-expressing cell lines (Figure 8). Our results revealed that VPA therapy markedly reduced SVCT2 levels in HCT-116 colorectal cancer cells with silenced SVCT2 (shSVCT2) expression compared with that in control cells (shscramble). Co-treatment of HCT-116 shSVCT2 cells with AA and VPA resulted in reduced intracellular uptake of AA, decreased ROS production, reduced apoptotic rates, and a diminished anti-cancer effect.

VPA was shown to upregulate SVCT2 expression in an in vivo model. In mice, treatment with VPA enhanced the expression of mSVCT2 protein, mRNA, and heterogeneous nuclear RNA (hnRNA) in the brain, a critical organ requiring antioxidant protection from vitamin C [

36]. In our xenograft model, we found that mSVCT2 expression was elevated in the tumor after VPA treatment alone and co-treatment with AA and VPA for 14 days. Furthermore, co-treatment with AA and VPA substantially reduced the tumor size and tumor volume (mm3) and enhanced the percentage of tumor growth inhibition (%TGI) in the xenografted mouse model. This was accompanied by enhanced expression of apoptosis-related proteins cleaved caspase-3 and Bax and suppressed expression of pro-caspase 3 and Bcl-2 within the tumor.

Collectively, these results indicate that VPA could enhance the anti-cancer effects of AA by upregulating SVCT2 expression in low-SVCT2-expressing colorectal cancer cells, suppressing the hermetic dose-response of vitamin C. Notably, to the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to establish that VPA can upregulate SVCT2 expression in colorectal cancer cells and to describe the synergistic anti-cancer effects of vitamin C and VPA. Our findings suggest that VPA acts as an SVCT2 inducer, opening the gateway for further research into the potential role of VPA in improving high-dose vitamin C therapy in cancer patients with low SVCT2 expression. Future investigations must identify the precise target molecules of VPA and elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying the regulation of SVCT2 expression in cancer cells, thereby improving our knowledge of high-dose vitamin C therapy for patients with cancer.

Author Contributions

K.K.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Visualization, Writing-Original draft preparation, Writing-Review and Editing. M.D.H.: Methodology, Investigation, Writing-Review and Editing. P.T.H.: Investigation, Writing-Review and Editing. A.L.: Investigation, Writing-Review and Editing. K.M.: Investigation, Writing-Review and Editing. M.K.L.: Investigation, Resources. H.K.: Writing-Reviewing and Editing. E.P.: Writing-Reviewing and Editing. T.-K.L.: Supervision, Funding Acquisition. S.L.: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Korea Institute of Marine Science & Technology Promotion (KIMST), funded by the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries, Korea (RS-2021-KS211475), along with support from Sungkyunkwan University, BK21 FOUR (Graduate School Innovation), funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE, Korea).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Research Center of Sungkyunkwan University (SKKU-2023-04-35-2, 20 Aug 2023 to 19 Aug 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Gyeonggi Bio Center (Suwon-si, Gyeonggi-do, 16229, Republic of Korea) for supplying some of the materials and flow cytometry instruments used in the experiments. Concurrently, we would like to express our gratitude to Editage [

http://www. editage.co.kr] for providing language editing services for this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Eulyong Park was employed by the company Easthill Corporation. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AA |

Ascorbic acid or Vitamin C |

| VPA |

Valproic acid |

| SVCT2 |

sodium-dependent vitamin C transporter 2 |

| ROS |

Reactive oxygen species |

| HDAC |

Histone deacetylase |

| C |

control |

| Conc |

concentrations |

| CCK-8 |

Cell-counting kit-8 |

| Bax |

Bcl-2-associated protein x |

| Bcl-2 |

B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| GAPDH |

Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| shRNA |

short hairpin RNA |

| DCFDA |

2’,7’ -Dichlorofluorescin diacetate |

| PI |

Propidium Iodide |

| IP |

Intraperitoneal |

| RTV |

Relative tumor volume |

| %TGI |

Tumor growth inhibitor ratio |

References

- Chen, Q. , et al., Pharmacologic ascorbic acid concentrations selectively kill cancer cells: action as a pro-drug to deliver hydrogen peroxide to tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2005. 102(38): p. 13604-9. [CrossRef]

- Mussa, A. , et al., High-Dose Vitamin C for Cancer Therapy. Pharmaceuticals (Basel), 2022. 15(6). [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.J. , et al., Effect of High-dose Vitamin C Combined With Anti-cancer Treatment on Breast Cancer Cells. Anticancer Res, 2019. 39(2): p. 751-758. [CrossRef]

- Maramag, C. , et al., Effect of vitamin C on prostate cancer cells in vitro: effect on cell number, viability, and DNA synthesis. Prostate, 1997. 32(3): p. 188-95. [CrossRef]

- Hadi, S.M. , et al., Catalytic therapy of cancer by ascorbic acid involves redox cycling of exogenous/endogenous copper ions and generation of reactive oxygen species. Chemotherapy, 2010. 56(4): p. 280-4. [CrossRef]

- Su, X. , et al., Vitamin C kills thyroid cancer cells through ROS-dependent inhibition of MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT pathways via distinct mechanisms. Theranostics, 2019. 9(15): p. 4461-4473. [CrossRef]

- Vissers, M.C.M. and A.B. Das, Potential Mechanisms of Action for Vitamin C in Cancer: Reviewing the Evidence. Front Physiol, 2018. 9: p. 809. [CrossRef]

- Colussi, C. , et al., H2O2-induced block of glycolysis as an active ADP-ribosylation reaction protecting cells from apoptosis. FASEB J, 2000. 14(14): p. 2266-76.

- Uetaki, M. , et al., Metabolomic alterations in human cancer cells by vitamin C-induced oxidative stress. Sci Rep, 2015. 5: p. 13896. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.H. , et al., Valproic acid (VPA) enhances cisplatin sensitivity of non-small cell lung cancer cells via HDAC2 mediated down regulation of ABCA1. Biol Chem, 2017. 398(7): p. 785-792. [CrossRef]

- Cho, S. , et al., Enhanced Anticancer Effect of Adding Magnesium to Vitamin C Therapy: Inhibition of Hormetic Response by SVCT-2 Activation. Transl Oncol, 2020. 13(2): p. 401-409.

- Giansanti, M. , et al., High-Dose Vitamin C: Preclinical Evidence for Tailoring Treatment in Cancer Patients. Cancers (Basel), 2021. 13(6). [CrossRef]

- Abiri, B. and M. Vafa, Vitamin C and Cancer: The Role of Vitamin C in Disease Progression and Quality of Life in Cancer Patients. Nutr Cancer, 2021. 73(8): p. 1282-1292. [CrossRef]

- Raymond, Y.C., C. S. Glenda, and L.K. Meng, Effects of High Doses of Vitamin C on Cancer Patients in Singapore: Nine Cases. Integr Cancer Ther, 2016. 15(2): p. 197-204.

- Cameron, E. and L. Pauling, Supplemental ascorbate in the supportive treatment of cancer: reevaluation of prolongation of survival times in terminal human cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1978. 75(9): p. 4538-42. [CrossRef]

- Cameron, E. and L. Pauling, Supplemental ascorbate in the supportive treatment of cancer: Prolongation of survival times in terminal human cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1976. 73(10): p. 3685-9. [CrossRef]

- Creagan, E.T. , et al., Failure of high-dose vitamin C (ascorbic acid) therapy to benefit patients with advanced cancer. A controlled trial. N Engl J Med, 1979. 301(13): p. 687-90. [CrossRef]

- Moertel, C.G. , et al., High-dose vitamin C versus placebo in the treatment of patients with advanced cancer who have had no prior chemotherapy. A randomized double-blind comparison. N Engl J Med, 1985. 312(3): p. 137-41. [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.J., D. Johnson, and S.M. Jarvis, Vitamin C transport systems of mammalian cells. Mol Membr Biol, 2001. 18(1): p. 87-95.

- Harrison, F.E. and J.M. May, Vitamin C function in the brain: vital role of the ascorbate transporter SVCT2. Free Radic Biol Med, 2009. 46(6): p. 719-30. [CrossRef]

- Linowiecka, K., M. Foksinski, and A.A. Brożyna, Vitamin C Transporters and Their Implications in Carcinogenesis. Nutrients, 2020. 12(12). [CrossRef]

- Cho, S. , et al., Hormetic dose response to L-ascorbic acid as an anti-cancer drug in colorectal cancer cell lines according to SVCT-2 expression. Scientific Reports, 2018. 8(1): p. 11372.

- Lagace, D.C. , et al., Valproic acid: how it works. Or not. Clinical Neuroscience Research, 2004. 4(3): p. 215-225.

- Wu, J. , et al., Valproic acid-induced encephalopathy: A review of clinical features, risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Epilepsy Behav, 2021. 120: p. 107967. [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Jovel, C. and N. Valencia, The Current Role of Valproic Acid in the Treatment of Epilepsy: A Glimpse into the Present of an Old Ally. Current Treatment Options in Neurology, 2024. 26(8): p. 393-410. [CrossRef]

- Lipska, K., A. Gumieniczek, and A.A. Filip, Anticonvulsant valproic acid and other short-chain fatty acids as novel anticancer therapeutics: Possibilities and challenges. Acta Pharm, 2020. 70(3): p. 291-301. [CrossRef]

- Al-Khafaji, A.S.K. , et al., Effect of valproic acid on histone deacetylase expression in oral cancer (Review). Oncol Lett, 2024. 27(5): p. 197. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. , et al., HDAC inhibitor, valproic acid, induces p53-dependent radiosensitization of colon cancer cells. Cancer Biother Radiopharm, 2009. 24(6): p. 689-99. [CrossRef]

- Blaauboer, A. , et al., The Class I HDAC Inhibitor Valproic Acid Strongly Potentiates Gemcitabine Efficacy in Pancreatic Cancer by Immune System Activation. Biomedicines, 2022. 10(3). [CrossRef]

- Wedel, S. , et al., Inhibitory effects of the HDAC inhibitor valproic acid on prostate cancer growth are enhanced by simultaneous application of the mTOR inhibitor RAD001. Life Sci, 2011. 88(9-10): p. 418-24. [CrossRef]

- Terranova-Barberio, M. , et al., Valproic acid potentiates the anticancer activity of capecitabine in vitro and in vivo in breast cancer models via induction of thymidine phosphorylase expression. Oncotarget, 2016. 7(7): p. 7715-31. [CrossRef]

- Blaheta, R.A. and J. Cinatl, Anti-tumor mechanisms of valproate: a novel role for an old drug. Med Res Rev, 2002. 22(5): p. 492-511. [CrossRef]

- Singh, D. , et al., Hidden pharmacological activities of valproic acid: A new insight. Biomed Pharmacother, 2021. 142: p. 112021. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. , et al., SVCT-2 determines the sensitivity to ascorbate-induced cell death in cholangiocarcinoma cell lines and patient derived xenografts. Cancer Lett, 2017. 398: p. 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Mologni, L. , et al., Valproic acid enhances bosutinib cytotoxicity in colon cancer cells. Int J Cancer, 2009. 124(8): p. 1990-6. [CrossRef]

- Teafatiller, T. , et al., Valproic acid upregulates sodium-dependent vitamin C transporter-2 functional expression in neuronal cells. Life Sci, 2022. 308: p. 120944. [CrossRef]

- Pesti-Asbóth, G. , et al., Ultrasonication affects the melatonin and auxin levels and the antioxidant system in potato. Front Plant Sci, 2022. 13: p. 979141. [CrossRef]

- Pawlowska, E., J. Szczepanska, and J. Blasiak, Pro- and Antioxidant Effects of Vitamin C in Cancer in correspondence to Its Dietary and Pharmacological Concentrations. Oxid Med Cell Longev, 2019. 2019: p. 7286737. [CrossRef]

- Wohlrab, C., E. Phillips, and G.U. Dachs, Vitamin C Transporters in Cancer: Current Understanding and Gaps in Knowledge. Front Oncol, 2017. 7: p. 74. [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.C. , et al., Drug Repurposing: The Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways of Anti-Cancer Effects of Anesthetics. Biomedicines, 2022. 10(7). [CrossRef]

- Aztopal, N. , et al., Valproic acid, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, induces apoptosis in breast cancer stem cells. Chem Biol Interact, 2018. 280: p. 51-58.

- Yagi, Y. , et al., Effects of valproic acid on the cell cycle and apoptosis through acetylation of histone and tubulin in a scirrhous gastric cancer cell line. J Exp Clin Cancer Res, 2010. 29(1): p. 149. [CrossRef]

- Atmaca, A. , et al., Valproic acid (VPA) in patients with refractory advanced cancer: a dose escalating phase I clinical trial. Br J Cancer, 2007. 97(2): p. 177-82. [CrossRef]

- Wawruszak, A. , et al., Valproic Acid and Breast Cancer: State of the Art in 2021. Cancers (Basel), 2021. 13(14). [CrossRef]

- Yuan, P.X. , et al., The mood stabilizer valproic acid activates mitogen-activated protein kinases and promotes neurite growth. J Biol Chem, 2001. 276(34): p. 31674-83. [CrossRef]

- Gan, C.P. , et al., Valproic acid: growth inhibition of head and neck cancer by induction of terminal differentiation and senescence. Head Neck, 2012. 34(3): p. 344-53. [CrossRef]

- Kwiecińska, P., E. Taubøll, and E.L. Gregoraszczuk, Effects of valproic acid and levetiracetam on viability and cell cycle regulatory genes expression in the OVCAR-3 cell line. Pharmacol Rep, 2012. 64(1): p. 157-65. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).