Submitted:

30 May 2025

Posted:

02 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Human Subjects

Cell Culture and Virus Stock

RT Realtime (RT2) PCR

Tumor Model Establishment and Treatment

Human Ovarian Cancer Ascites CD14+ Macrophages and CD4+ T Cell Co-Culture System

Statistical Analyses

3. Results

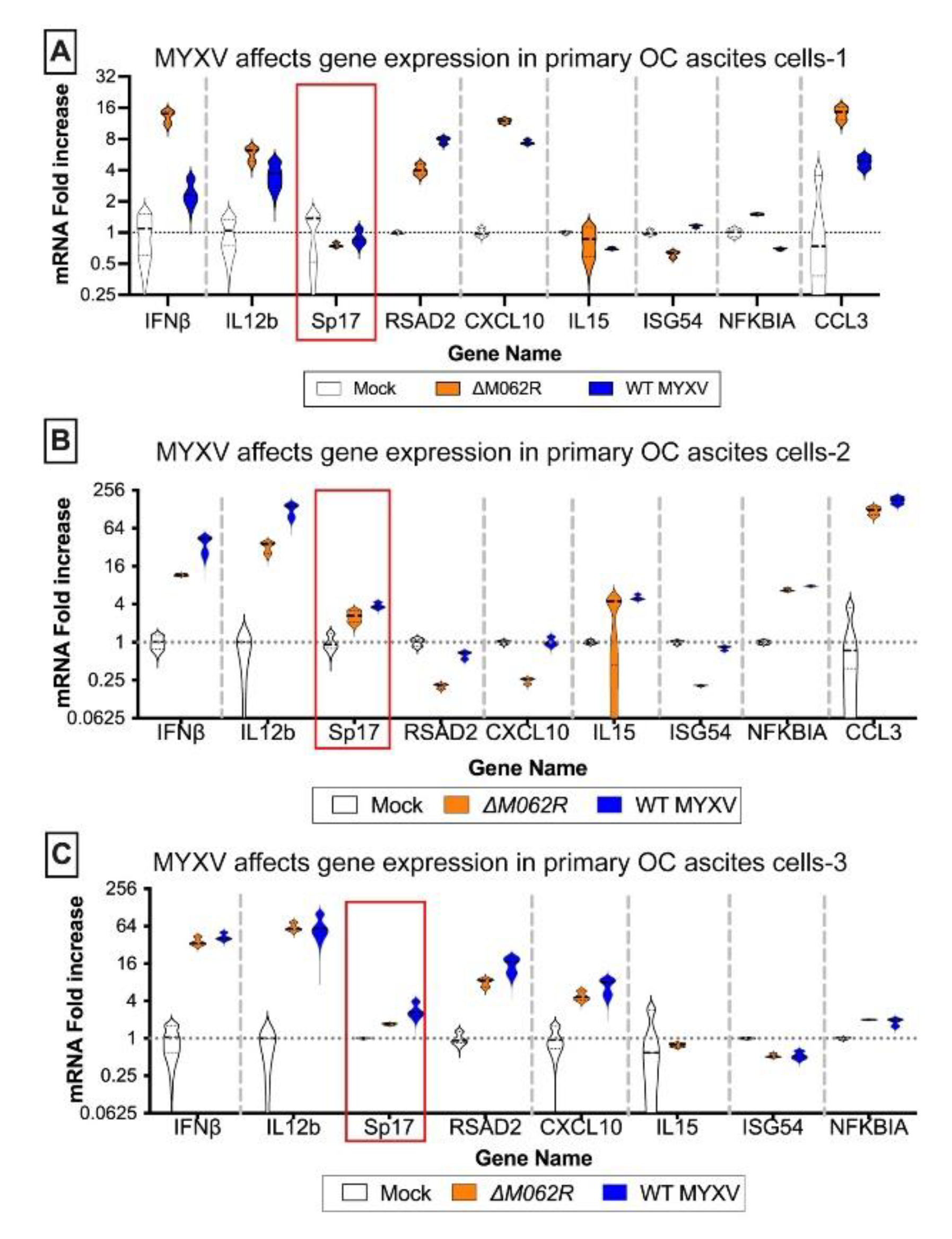

3.1. Myxoma Virus Infection in Primary Cells of Human Ovarian Cancer Environment Stimulated Pro-Inflammatory Gene Expression and Up-Regulation of Sp17

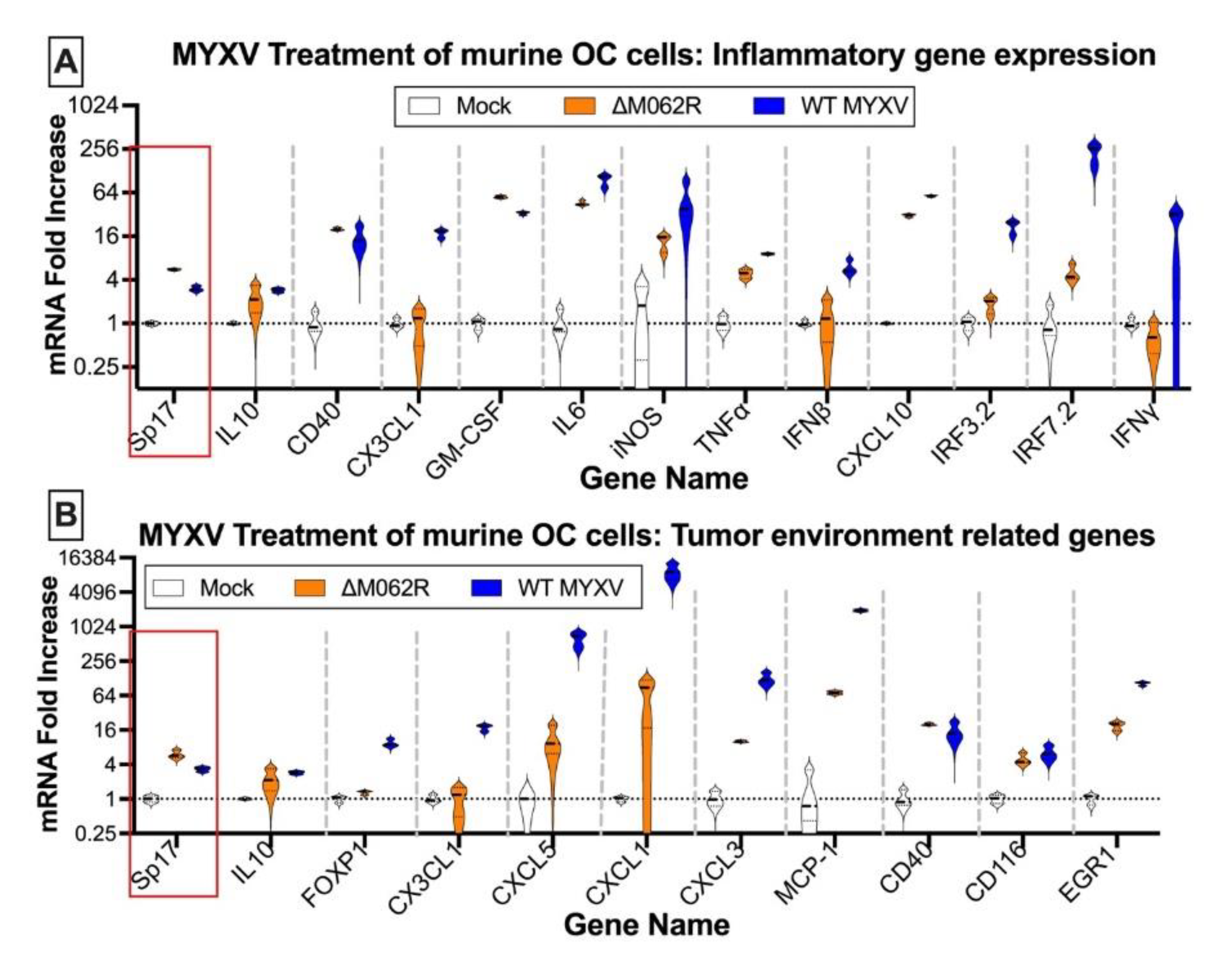

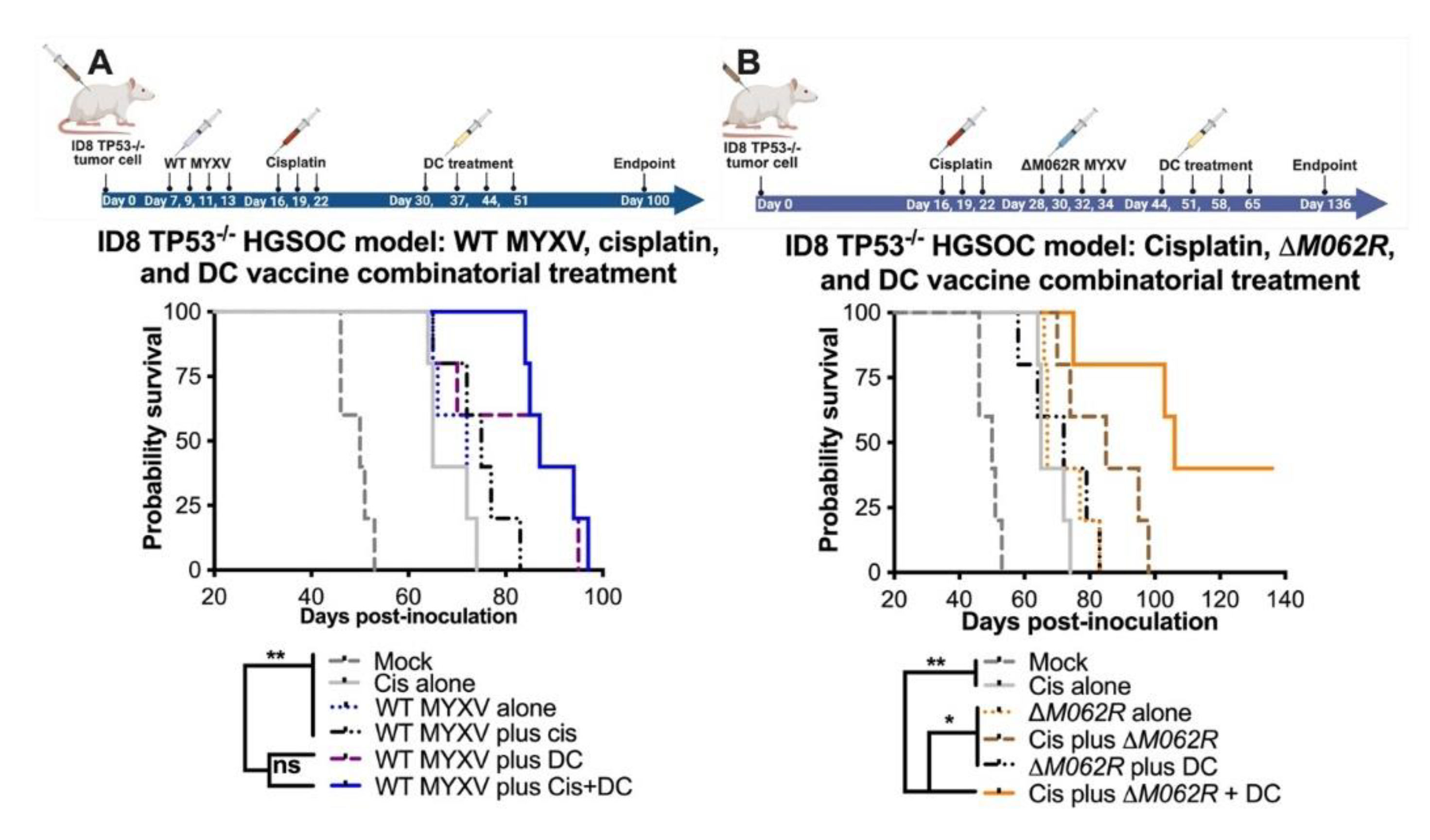

3.2. Wildtype MYXV Treatment Proceeding Cisplatin Treatment Led to Moderate Therapeutic Benefit in a High Grade Serious Ovarian Cancer (HGSOC) Murine Syngeneic Model

3.3. M062R-Null (ΔM062R) MYXV Treatment as Monotherapy or in Combination with DC Vaccine Targeting Sp17 Antigen Showed Significant Treatment Benefit in the HGSOC Murine Syngeneic Models.

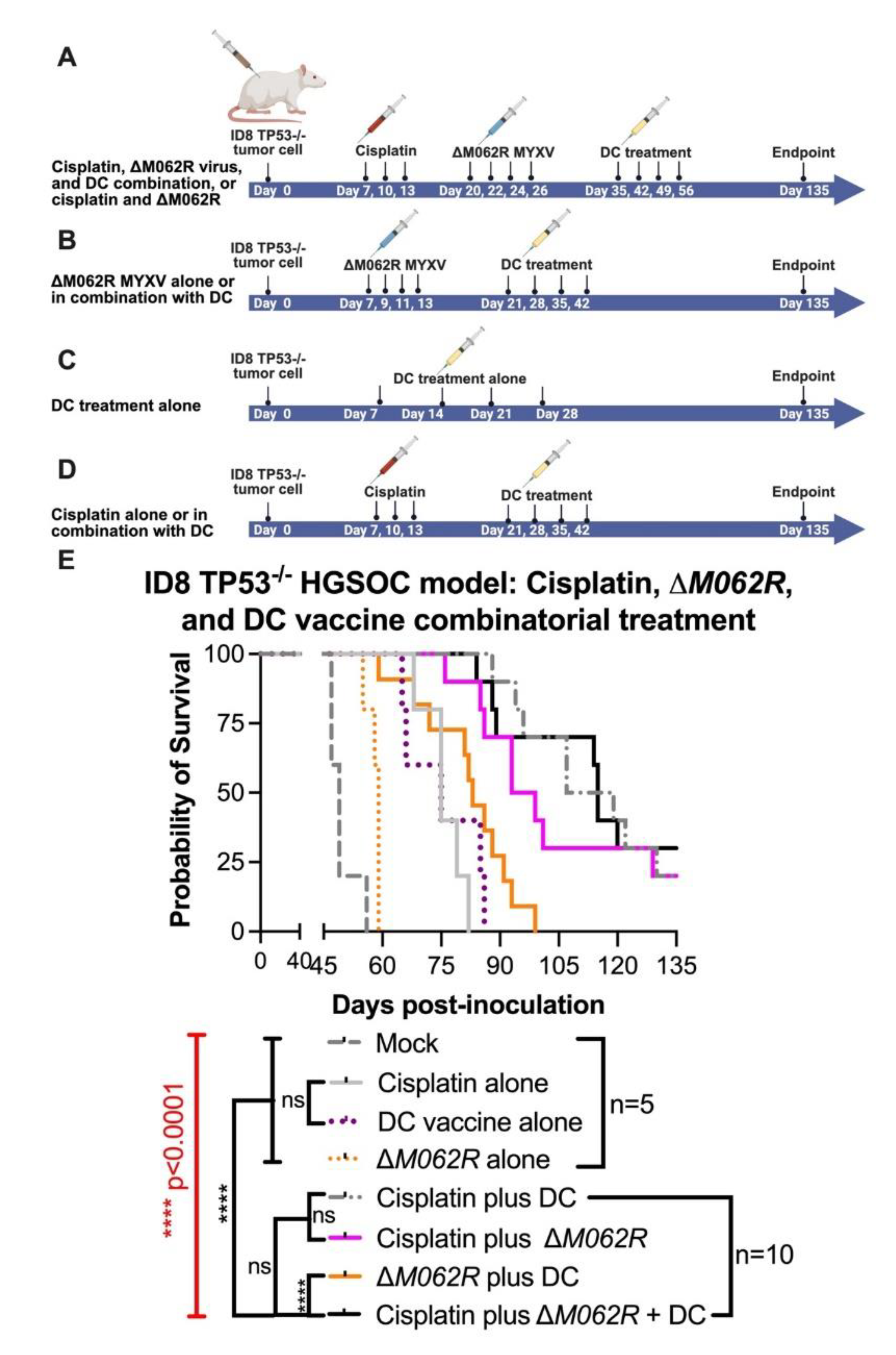

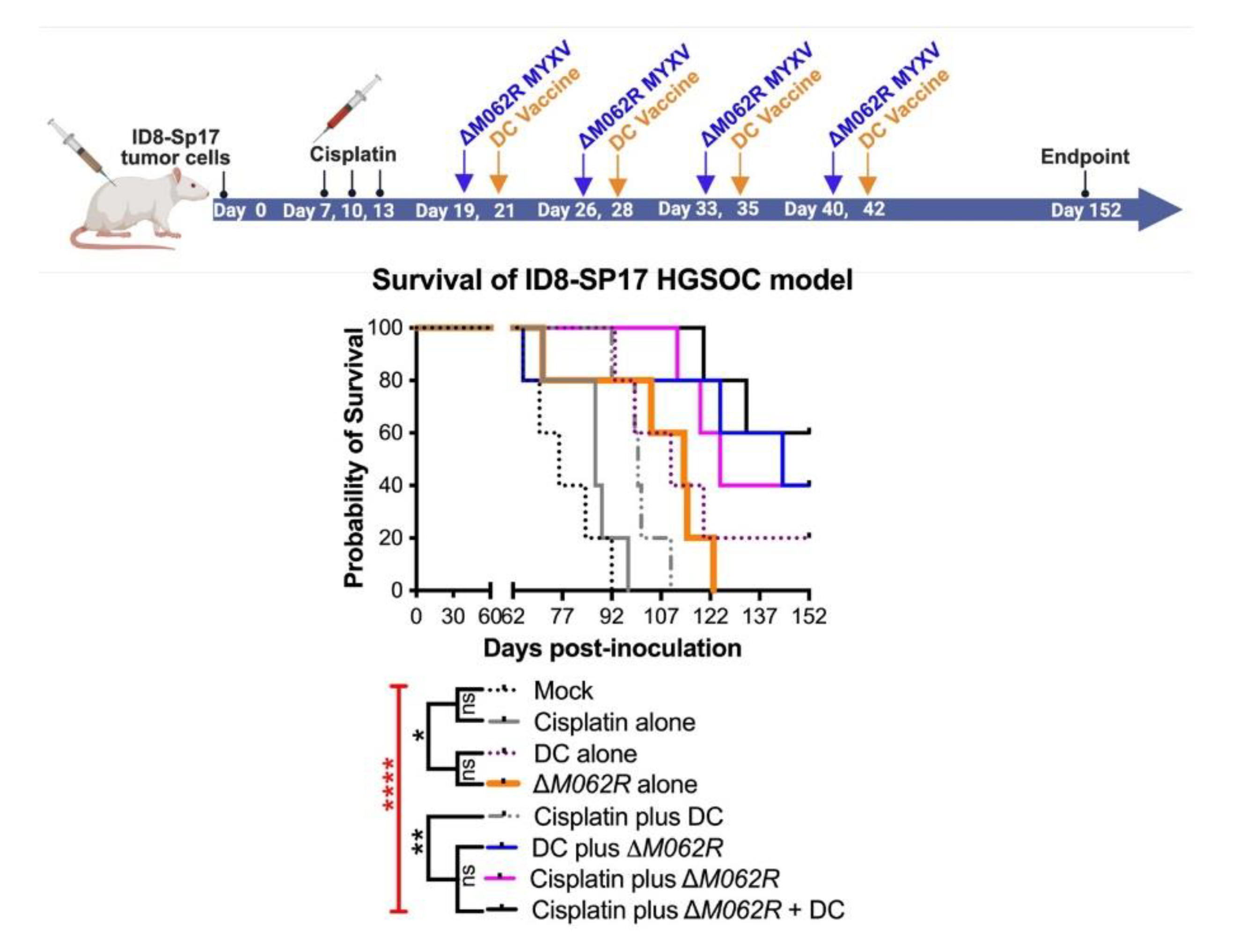

3.4. M062R-Null (ΔM062R) MYXV Treatment in Combination with DC Vaccine Targeting Sp17 Antigen Significantly Improve the Treatment Outcome of Cisplatin.

3.5. Scheduling of ΔM062R MYXV Treatment Is Critical to Achieve the Optimal Immunotherapeutic Outcome.

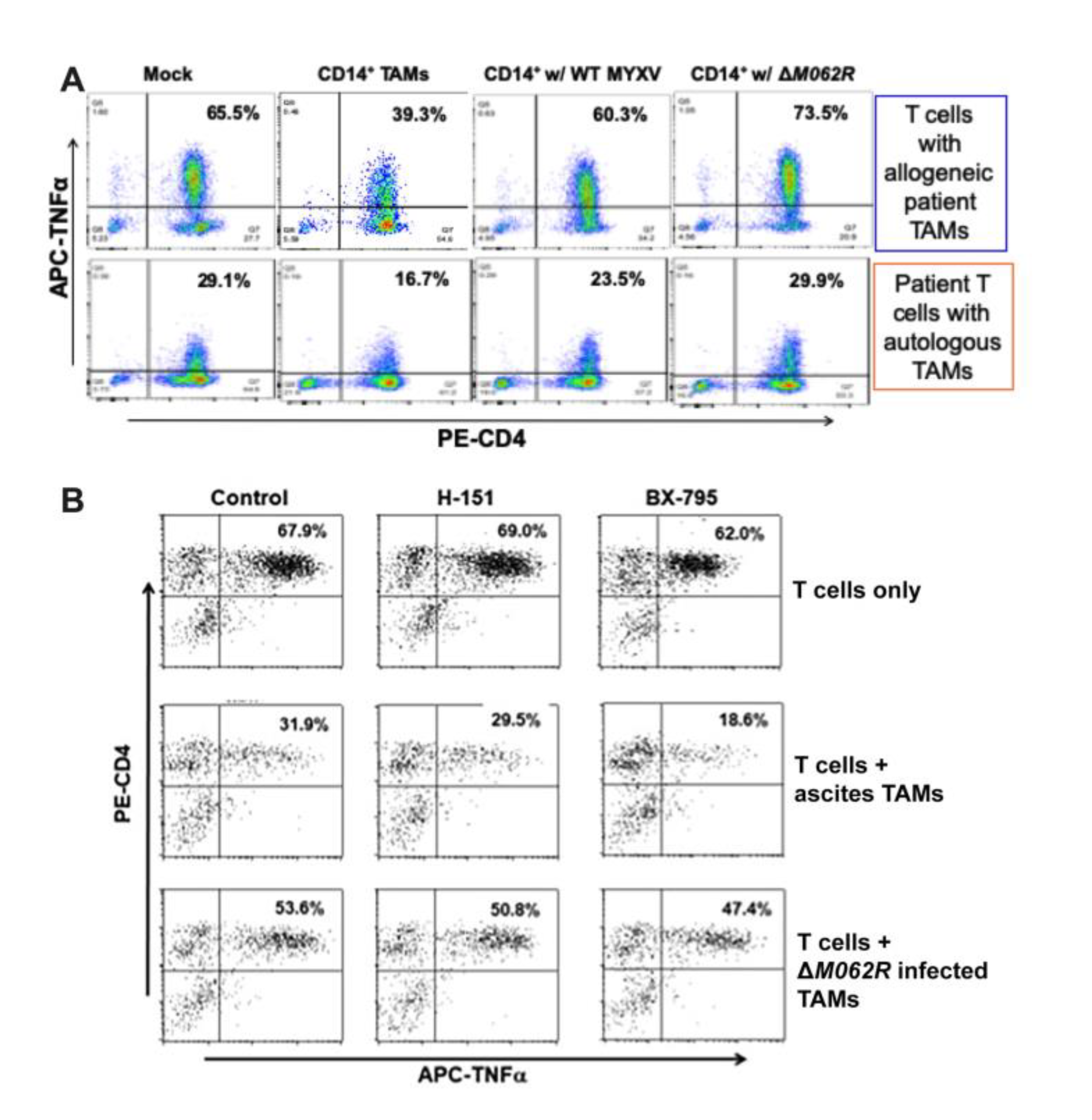

3.6. M062R-Null MYXV Infection of Ovarian Cancer Patient Ascites CD14+ Cells Improved CD4+ T Cell Anti-Tumor Response in a Primary Cell Co-Culture System.

4. Discussion

5. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MYXV | Myxoma virus |

| OC | Ovarian cancer |

| DC | Dendritic cell |

| TAM | Tumor-associated macrophage |

| HGSOC. | High grade serous ovarian cancer |

References

- Lengyel E 2010 Ovarian cancer development and metastasis Am J Pathol 177 1053–64. [CrossRef]

- Ozols R F 2006 Challenges for chemotherapy in ovarian cancer Ann Oncol 17 Suppl 5 v181-7. [CrossRef]

- Cummings M, Freer C and Orsi N M 2021 Targeting the tumour microenvironment in platinum-resistant ovarian cancer Semin. Cancer Biol. 77 3–28. [CrossRef]

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel R L, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F 2021 Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries CA. Cancer J. Clin. 71 209–49. [CrossRef]

- Richardson D L, Eskander R N and O’Malley D M 2023 Advances in Ovarian Cancer Care and Unmet Treatment Needs for Patients With Platinum Resistance: A Narrative Review JAMA Oncol. 9 851–9. [CrossRef]

- Coleman M P, Forman D, Bryant H, Butler J, Rachet B, Maringe C, Nur U, Tracey E, Coory M, Hatcher J, McGahan C E, Turner D, Marrett L, Gjerstorff M L, Johannesen T B, Adolfsson J, Lambe M, Lawrence G, Meechan D, Morris E J, Middleton R, Steward J, Richards M A and Group I M 1 W 2011 Cancer survival in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and the UK, 1995-2007 (the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership): an analysis of population-based cancer registry data Lancet 377 127–38. [CrossRef]

- Baert T, Timmerman D, Vergote I and Coosemans A 2015 Immunological parameters as a new lead in the diagnosis of ovarian cancer Facts Views Vis Obgyn 7 67–72.

- Coosemans A, Decoene J, Baert T, Laenen A, Kasran A, Verschuere T, Seys S and Vergote I 2015 Immunosuppressive parameters in serum of ovarian cancer patients change during the disease course Oncoimmunology 5 e1111505. [CrossRef]

- Krishnan V, Schaar B, Tallapragada S and Dorigo O 2018 Tumor associated macrophages in gynecologic cancers Gynecol. Oncol. 149 205–13. [CrossRef]

- Blanc-Durand F, Clemence Wei Xian L and Tan D S P 2023 Targeting the immune microenvironment for ovarian cancer therapy Front. Immunol. 14 1328651. [CrossRef]

- Goyne H E and Cannon M J 2013 Dendritic cell vaccination, immune regulation, and clinical outcomes in ovarian cancer Front Immunol 4 382. [CrossRef]

- Cannon M J, Goyne H, Stone P J B and Chiriva-Internati M 2011 Dendritic cell vaccination against ovarian cancer--tipping the Treg/TH17 balance to therapeutic advantage? Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 11 441–5. [CrossRef]

- Rahman M M and McFadden G 2020 Oncolytic Virotherapy with Myxoma Virus J. Clin. Med. 9 171. [CrossRef]

- Stanford M M, Barrett J W, Gilbert P A, Bankert R and McFadden G 2007 Myxoma virus expressing human interleukin-12 does not induce myxomatosis in European rabbits J Virol 81 12704–8. [CrossRef]

- Tosic V, Thomas D L, Kranz D M, Liu J, McFadden G, Shisler J L, MacNeill A L and Roy E J 2014 Myxoma virus expressing a fusion protein of interleukin-15 (IL15) and IL15 receptor alpha has enhanced antitumor activity PLoS One 9 e109801. [CrossRef]

- Christie J D, Appel N, Canter H, Achi J G, Elliott N M, Matos A L de, Franco L, Kilbourne J, Lowe K, Rahman M M, Villa N Y, Carmen J, Luna E, Blattman J and McFadden G 2021 Systemic delivery of TNF-armed myxoma virus plus immune checkpoint inhibitor eliminates lung metastatic mouse osteosarcoma Mol. Ther. - Oncolytics 22 539–54. [CrossRef]

- Chan W M, Rahman M M and McFadden G 2013 Oncolytic myxoma virus: The path to clinic Vaccine. [CrossRef]

- Conrad S J, Raza T, Peterson E A, Liem J, Connor R, Nounamo B, Cannon M and Liu J 2022 Myxoma virus lacking the host range determinant M062 stimulates cGAS-dependent type 1 interferon response and unique transcriptomic changes in human monocytes/macrophages PLoS Pathog. 18 e1010316. [CrossRef]

- Zheng N, Fang J, Xue G, Wang Z, Li X, Zhou M, Jin G, Rahman M M, McFadden G and Lu Y 2022 Induction of tumor cell autosis by myxoma virus-infected CAR-T and TCR-T cells to overcome primary and acquired resistance Cancer Cell 40 973-985.e7. [CrossRef]

- Nounamo B, Liem J, Cannon M and Liu J 2017 Myxoma virus optimizes cisplatin for the treatment of ovarian cancer in vitro and in a syngeneic murine dissemination model Mol. Ther.-Oncolytics 6 90–9. [CrossRef]

- Wennier S T, Liu J, Li S, Rahman M M, Mona M and McFadden G 2012 Myxoma virus sensitizes cancer cells to gemcitabine and is an effective oncolytic virotherapeutic in models of disseminated pancreatic cancer Mol Ther 20 759–68. [CrossRef]

- Jung M-Y, Offord C P, Ennis M K, Kemler I, Neuhauser C and Dingli D 2018 In vivo estimation of oncolytic virus populations within tumors Cancer Res. 78 5992–6000. [CrossRef]

- Lin D, Shen Y and Liang T 2023 Oncolytic virotherapy: basic principles, recent advances and future directions Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 8 1–29. [CrossRef]

- Block M S, Dietz A B, Gustafson M P, Kalli K R, Erskine C L, Youssef B, Vijay G V, Allred J B, Pavelko K D, Strausbauch M A, Lin Y, Grudem M E, Jatoi A, Klampe C M, Wahner-Hendrickson A E, Weroha S J, Glaser G E, Kumar A, Langstraat C L, Solseth M L, Deeds M C, Knutson K L and Cannon M J 2020 Th17-inducing autologous dendritic cell vaccination promotes antigen-specific cellular and humoral immunity in ovarian cancer patients Nat. Commun. 11 5173. [CrossRef]

- Walton J, Blagih J, Ennis D, Leung E, Dowson S, Farquharson M, Tookman L A, Orange C, Athineos D, Mason S, Stevenson D, Blyth K, Strathdee D, Balkwill F R, Vousden K, Lockley M and McNeish I A 2016 CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Trp53 and Brca2 Knockout to Generate Improved Murine Models of Ovarian High-Grade Serous Carcinoma Cancer Res 76 6118–29. [CrossRef]

- Luo Y, Shreeder B, Jenkins J W, Shi H, Lamichhane P, Zhou K, Bahr D A, Kurian S, Jones K A, Daum J I, Dutta N, Necela B M, Cannon M J, Block M S and Knutson K L 2023 Th17-inducing dendritic cell vaccines stimulate effective CD4 T cell-dependent antitumor immunity in ovarian cancer that overcomes resistance to immune checkpoint blockade J. Immunother. Cancer 11 e007661. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Wennier S, Zhang L and McFadden G 2011 M062 is a host range factor essential for myxoma virus pathogenesis and functions as an antagonist of host SAMD9 in human cells J Virol 85 3270–82. [CrossRef]

- Smallwood S E, Rahman M M, Smith D W and McFadden G 2010 Myxoma virus: propagation, purification, quantification, and storage Curr Protoc Microbiol Chapter 14 Unit 14A 1. [CrossRef]

- Lee P Y, Li Y, Kumagai Y, Xu Y, Weinstein J S, Kellner E S, Nacionales D C, Butfiloski E J, van Rooijen N, Akira S, Sobel E S, Satoh M and Reeves W H 2009 Type I Interferon Modulates Monocyte Recruitment and Maturation in Chronic Inflammation Am. J. Pathol. 175 2023–33. [CrossRef]

- Lee P Y, Weinstein J S, Nacionales D C, Scumpia P O, Li Y, Butfiloski E, van Rooijen N, Moldawer L, Satoh M and Reeves W H 2008 A Novel Type I IFN-Producing Cell Subset in Murine Lupus1 J. Immunol. 180 5101–8. [CrossRef]

- Lee P Y, Kumagai Y, Li Y, Takeuchi O, Yoshida H, Weinstein J, Kellner E S, Nacionales D, Barker T, Kelly-Scumpia K, van Rooijen N, Kumar H, Kawai T, Satoh M, Akira S and Reeves W H 2008 TLR7-dependent and FcγR-independent production of type I interferon in experimental mouse lupus J. Exp. Med. 205 2995–3006. [CrossRef]

- Lee P Y, Kumagai Y, Xu Y, Li Y, Barker T, Liu C, Sobel E S, Takeuchi O, Akira S, Satoh M and Reeves WestleyH 2011 Interleukin-1 alpha modulates neutrophil recruitment in chronic inflammation induced by hydrocarbon oil J. Immunol. Baltim. Md 1950 186 1747–54. [CrossRef]

- Goyne H E, Stone P J, Burnett A F and Cannon M J 2014 Ovarian tumor ascites CD14+ cells suppress dendritic cell-activated CD4+ T-cell responses through IL-10 secretion and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase J Immunother 37 163–9. [CrossRef]

- Cannon M J, Goyne H E, Stone P J, Macdonald L J, James L E, Cobos E and Chiriva-Internati M 2013 Modulation of p38 MAPK signaling enhances dendritic cell activation of human CD4+ Th17 responses to ovarian tumor antigen Cancer Immunol Immunother 62 839–49. [CrossRef]

- Cannon M J, Ghosh D and Gujja S 2015 Signaling Circuits and Regulation of Immune Suppression by Ovarian Tumor-Associated Macrophages Vaccines 3 448–66. [CrossRef]

- Straughn J M Jr, Shaw D R, Guerrero A, Bhoola S M, Racelis A, Wang Z, Chiriva-Internati M, Grizzle W E, Alvarez R D, Lim S H and Strong T V 2004 Expression of sperm protein 17 (Sp17) in ovarian cancer Int J Cancer 108 805–11. [CrossRef]

- Chiriva-Internati M, Grizzi F, Weidanz J A, Ferrari R, Yuefei Y, Velez B, Shearer M H, Lowe D B, Frezza E E, Cobos E, Kast W M and Kennedy R C 2007 A NOD/SCID tumor model for human ovarian cancer that allows tracking of tumor progression through the biomarker Sp17 J Immunol Methods 321 86–93. [CrossRef]

- Song J X, Cao W L, Li F Q, Shi L N and Jia X 2012 Anti-Sp17 monoclonal antibody with antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity and complement-dependent cytotoxicity activities against human ovarian cancer cells Med Oncol 29 2923–31. [CrossRef]

- Xiang S D, Gao Q, Wilson K L, Heyerick A and Plebanski M 2015 A Nanoparticle Based Sp17 Peptide Vaccine Exposes New Immuno-Dominant and Species Cross-reactive B Cell Epitopes Vaccines Basel 3 875–93. [CrossRef]

- Song J X, Li F Q, Cao W L, Jia X, Shi L N, Lu J F, Ma C F and Kong Q Q 2014 Anti-Sp17 monoclonal antibody-doxorubicin conjugates as molecularly targeted chemotherapy for ovarian carcinoma Target Oncol 9 263–72. [CrossRef]

- Ait-Tahar K, Anderson A P, Barnardo M, Collins G P, Hatton C S R, Banham A H and Pulford K 2017 Sp17 Protein Expression and Major Histocompatibility Class I and II Epitope Presentation in Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma Patients Adv Hematol 2017 6527306. [CrossRef]

- Chiriva-Internati M, Yu Y, Mirandola L, Jenkins M R, Chapman C, Cannon M, Cobos E and Kast W M 2010 Cancer testis antigen vaccination affords long-term protection in a murine model of ovarian cancer PLoS One 5 e10471. [CrossRef]

- Raza T, Perterson E, Liem J and Liu J 2024 Antagonizing the SAMD9 pathway is key to myxoma virus host shut-off and immune evasion BioRxiv Prepr. Serv. Biol. 2024.02.01.578447. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed A A, Etemadmoghadam D, Temple J, Lynch A G, Riad M, Sharma R, Stewart C, Fereday S, Caldas C, Defazio A, Bowtell D and Brenton J D 2010 Driver mutations in TP53 are ubiquitous in high grade serous carcinoma of the ovary J Pathol 221 49–56. [CrossRef]

- Zhao J, Chen R, Zhang Y, Wang Y and Zhu H 2024 Impact of Treatment Delay on the Prognosis of Patients with Ovarian Cancer: A Population-based Study Using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Database J. Cancer 15 473–83. [CrossRef]

- Nagel C, Backes F, Donner J, Bussewitz E, Hade E, Cohn D, Eisenhauer E, O’Malley D, Fowler J, Copeland L and Salani R 2012 Effect of chemotherapy delays and dose reductions on progression free and overall survival in the treatment of epithelial ovarian cancer Gynecol. Oncol. 124 221–4. [CrossRef]

- Hopkins D, Sanchez H, Berwin B and Wilkinson-Ryan I 2021 Cisplatin increases immune activity of monocytes and cytotoxic T-cells in a murine model of epithelial ovarian cancer Transl. Oncol. 14 101217. [CrossRef]

- Chan W M, Bartee E C, Moreb J S, Dower K, Connor J H and McFadden G 2013 Myxoma and vaccinia viruses bind differentially to human leukocytes J. Virol. 87 4445–60. [CrossRef]

- Lun X, Yang W, Alain T, Shi Z Q, Muzik H, Barrett J W, McFadden G, Bell J, Hamilton M G, Senger D L and Forsyth P A 2005 Myxoma virus is a novel oncolytic virus with significant antitumor activity against experimental human gliomas Cancer Res 65 9982–90. [CrossRef]

- Rahman M M and McFadden G 2020 Oncolytic Virotherapy with Myxoma Virus J. Clin. Med. 9 171. [CrossRef]

- Stanford M M, Shaban M, Barrett J W, Werden S J, Gilbert P A, Bondy-Denomy J, Mackenzie L, Graham K C, Chambers A F and McFadden G 2008 Myxoma virus oncolysis of primary and metastatic B16F10 mouse tumors in vivo Mol Ther 16 52–9. [CrossRef]

- Stanford M M, Barrett J W, Nazarian S H, Werden S and McFadden G 2007 Oncolytic virotherapy synergism with signaling inhibitors: Rapamycin increases myxoma virus tropism for human tumor cells J Virol 81 1251–60. [CrossRef]

- Tong J G, Valdes Y R, Barrett J W, Bell J C, Stojdl D, McFadden G, McCart J A, DiMattia G E and Shepherd T G 2015 Evidence for differential viral oncolytic efficacy in an in vitro model of epithelial ovarian cancer metastasis Mol Ther Oncolytics 2 15013. [CrossRef]

- Bartee E, Chan W M, Moreb J S, Cogle C R and McFadden G 2012 Selective purging of human multiple myeloma cells from autologous stem cell transplantation grafts using oncolytic myxoma virus Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 18 1540–51. [CrossRef]

- Bartee M Y, Dunlap K M and Bartee E 2016 Myxoma Virus Induces Ligand Independent Extrinsic Apoptosis in Human Myeloma Cells Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 16 203–12. [CrossRef]

- Madlambayan G J, Bartee E, Kim M, Rahman M M, Meacham A, Scott E W, McFadden G and Cogle C R 2012 Acute myeloid leukemia targeting by myxoma virus in vivo depends on cell binding but not permissiveness to infection in vitro Leuk Res 36 619–24. [CrossRef]

- Jazowiecka-Rakus J, Pogoda-Mieszczak K, Rahman M M, McFadden G and Sochanik A 2024 Adipose-Derived Stem Cells as Carrier of Pro-Apoptotic Oncolytic Myxoma Virus: To Cross the Blood-Brain Barrier and Treat Murine Glioma Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25 11225. [CrossRef]

- Thomas D L, Doty R, Tosic V, Liu J, Kranz D M, McFadden G, Macneill A L and Roy E J 2011 Myxoma virus combined with rapamycin treatment enhances adoptive T cell therapy for murine melanoma brain tumors Cancer Immunol Immunother 60 1461–72. [CrossRef]

- Zemp F J, Lun X, McKenzie B A, Zhou H, Maxwell L, Sun B, Kelly J J, Stechishin O, Luchman A, Weiss S, Cairncross J G, Hamilton M G, Rabinovich B A, Rahman M M, Mohamed M R, Smallwood S, Senger D L, Bell J, McFadden G and Forsyth P A 2013 Treating brain tumor-initiating cells using a combination of myxoma virus and rapamycin Neuro Oncol 15 904–20. [CrossRef]

- Nounamo B, Li Y, O’Byrne P, Kearney A M, Khan A and Liu J 2017 An interaction domain in human SAMD9 is essential for myxoma virus host-range determinant M062 antagonism of host anti-viral function Virology 503 94–102. [CrossRef]

- Liu J and McFadden G 2015 SAMD9 is an innate antiviral host factor with stress response properties that can be antagonized by poxviruses J. Virol. 89 1925–31. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Wennier S and McFadden G 2010 The immunoregulatory properties of oncolytic myxoma virus and their implications in therapeutics Microbes Infect 12 1144–52. [CrossRef]

- Kroeger D R, Milne K and Nelson B H 2016 Tumor-Infiltrating Plasma Cells Are Associated with Tertiary Lymphoid Structures, Cytolytic T-Cell Responses, and Superior Prognosis in Ovarian Cancer Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 22 3005–15. [CrossRef]

- Lee K-W, Yam J W P and Mao X 2023 Dendritic Cell Vaccines: A Shift from Conventional Approach to New Generations Cells 12 2147. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X-W, Wu Y-S, Xu T-M and Cui M-H 2023 CAR-T Cells in the Treatment of Ovarian Cancer: A Promising Cell Therapy Biomolecules 13 465. [CrossRef]

- Kang C, Jeong S-Y, Song S Y and Choi E K 2020 The emerging role of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in radiotherapy Radiat. Oncol. J. 38 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Villa N Y, Rahman M M, Mamola J, Sharik M E, de Matos A L, Kilbourne J, Lowe K, Daggett-Vondras J, D’Isabella J, Goras E, Chesi M, Bergsagel P L and McFadden G 2022 Transplantation of autologous bone marrow pre-loaded ex vivo with oncolytic myxoma virus is efficacious against drug-resistant Vk*MYC mouse myeloma Oncotarget 13 490–504. [CrossRef]

- Bartee E, Chan W S, Moreb J S, Cogle C R and McFadden G 2012 Selective purging of human multiple myeloma cells from autologous stem cell transplant grafts using oncolytic myxoma virus Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. J. Am. Soc. Blood Marrow Transplant. 18 1540–51. [CrossRef]

- Villa N Y, Bais S, Chan W M, Meacham A M, Wise E, Rahman M M, Moreb J S, Rosenau E H, Wingard J R, McFadden G and Cogle C R 2016 Ex vivo virotherapy with myxoma virus does not impair hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells Cytotherapy 18 465–80. [CrossRef]

- Villa N Y, Rahman M M, McFadden G and Cogle C R 2016 Therapeutics for Graft-versus-Host Disease: From Conventional Therapies to Novel Virotherapeutic Strategies Viruses 8 85. [CrossRef]

| Target Gene | Primer sequences |

|---|---|

|

Human IFNβ |

Fwd 5’- GCC ATC AGT CAC TTA AAC AGC -3’ |

| Rev 5’- GAA ACT GAA GAT CTC CTA GCC T -3’ | |

|

Human IL-12b |

Fwd 5’- CAAAGGAGGCGAGGTTCTAA-3’ |

| Rev 5’- GCAGGTGAAACGTCCAGAATA-3’ | |

|

Human Sp17 |

Fwd 5’- GGTTCCATAGGCAGTTCTTAC-3’ |

| Rev 5’- GGAAGGCAGCTTGGATTT-3’ | |

|

Human RSAD2 |

Fwd 5’- AGT GCA ACT ACA AAT GCG GC -3’ |

| Rev 5’- CTT GCC CAG GTA TTC TCC CC -3’ | |

|

Human CXCL-10 |

Fwd 5’- CTG TAC CTG CAT CAG CAT TAG TA -3’ |

| Rev 5’- GAC ATC TCT TCT CAC CCT TCT TT -3’ | |

|

Human IL15 |

Fwd 5’- AGCCAACTGGGTGAATGTAATA-3’ |

| Rev 5’- CATCTCCGGACTCAAGTGAAATA-3’ | |

|

Human ISG54 |

Fwd 5’- AGCGAAGGTGTGCTTTGAGA -3’ |

| Rev 5’- GAGGGTCAATGGCGTTCTGA -3’ | |

|

Human NFκB1A |

Fwd 5’- CCCTACACCTTGCCTGTGAG -3’ |

| Rev 5’- TGACATCAGCACCCAAGGAC -3’ | |

|

Human CCL3 |

Fwd 5’- CTCTCTGCAACCAGTTCTC-3’ |

| Rev 5’- CTGCTCGTCTCAAAGTAGTC-3’ | |

|

Murine Sp17 |

Fwd 5’- CTTTCTCCAACACCCACTAC-3’ |

| Rev 5’- CTTCATCTTCTTTACCTCTTCTCT-3’ | |

|

Murine IL-10 |

Fwd 5’- AGGCGCTGTCATCGATTTCT -3’ |

| Rev 5’- ATGGCCTTGTAGACACCTTGG-3’ | |

|

Murine CD40 |

Fwd 5’- GTAGGTCACCCCTGAGAACC-3’ |

| Rev 5’- ACAACCCGAACCATACACACAA-3’ | |

|

Murine CX3CL1 [29] |

Fwd 5’- GCTCCTAGCCCTGACCCATC-3’ |

| Rev 5’- AGCTGATAGCGGATGAGCAA-3’ | |

|

Murine GM-CSF |

Fwd 5’- CTGGCCCCATGTATAGCTGA-3’ |

| Rev 5’- ACAGTCCGTTTCCGGAGTTG-3’ | |

|

Murine IL-6 |

Fwd 5’- TCAATATTAGAGTCTCAACCCCCA-3’ |

| Rev 5’- GAAGGCGCTTGTGGAGAAGG-3’ | |

|

Murine iNOS [30] |

Fwd 5’- ATCGACCCGTCCACAGTATG-3’ |

| Rev 5’- GATGGACCCCAAGCAAGACT-3’ | |

|

Murine TNFα |

Fwd 5’-CCCTCACACTCACAAACCAC-3’ |

| Rev 5’- ACAAGGTACAACCCATCGGC-3’ | |

|

Murine IFNβ |

Fwd 5’- AGATCTCTGCTCGGACCACC-3’ |

| Rev 5’- CGTGGGAGATGTCCTCAACT-3’ | |

|

Murine CXCL10 |

Fwd 5’- ATGACGGGCCAGTGAGAATG -3’ |

| Rev 5’- TCGTGGCAATGATCTCAACAC-3’ | |

|

Murine IRF3.2 |

Fwd 5’- CACTCCCCACGCTACACTC-3’ |

| Rev 5’- TCCCATCCCCAGTAGCATGAG-3’ | |

|

Murine IRF7.2 [31] |

Fwd 5’- TGCTGTTTGGAGACTGGCTAT-3’ |

| Rev 5’- TCCAAGCTCCCGGCTAAGT-3’ | |

|

Murine IFNγ |

Fwd 5’- CGGCACAGTCATTGAAAGCC-3’ |

| Rev 5’- TGTCACCATCCTTTTGCCAGT-3’ | |

|

Murine CXCL1 [29] |

Fwd 5’- GCTGGGATTCACCTCAAGAA-3’ |

| Rev 5’- TCTCCGTTACTTGGGGACAC-3’ | |

|

Murine CXCL3 [32] |

Fwd 5’- CCACTCTCAAGGATGGTCAA -3’ |

| Rev 5’- GGATGGATCGCTTTTCTCTG -3’ | |

|

Murine MCP-1 [30] |

Fwd 5’- AGGTCCCTGTCATGCTTCTG-3’ |

| Rev 5’- GGATCATCTTGCTGGTGAAT-3’ | |

|

Murine EGR1 |

Fwd 5’- CACCTGACCGCAGAGTCTTTT-3’ |

| Rev 5’- GCGGCCAGTATAGGTGATGG-3’ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).