1. Introduction

The expression enthalpy-entropy compensation means that the enthalpy change and the entropy change associated with a given process can be individually large, but, on the strength of the fundamental thermodynamic relationship ΔG = ΔH - T⋅ΔS, the variation of these two state functions produces a small change in the Gibbs free energy [

1]. A simple explanation of the phenomenon can be that a strengthening of energetic interactions among molecules leads to a negative enthalpy change, but also to a decrease in the degrees of freedom and, therefore, to a negative entropy change. Despite the validity of the previous sentence, it does not provide a useful rationalization of the phenomenon of enthalpy-entropy compensation. In the past, there was debate about the real occurrence of the phenomenon in light of the procedures adopted to arrive at the thermodynamic values starting from the experimental data [

2,

3,

4,

5]; however, this debate now seems to have reached a conclusion [

6].

Enthalpy-entropy compensation is widely associated with processes occurring in water or aqueous solutions, as pointed out by Lumry and Rajender in a pioneering article published in 1970 [

7]. Since then, the scenario has not changed, confirming that water plays a pivotal role in the phenomenon of enthalpy-entropy compensation [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. For instance, the temperature-induced unfolding of small globular proteins in aqueous solutions is usually a reversible process characterized by both large positive enthalpy changes and large positive entropy changes around the denaturation temperature, and, for the same reasons, the Gibbs free energy change associated with denaturation, evaluated around room temperature, is modest (look at Figure 2 and Figure 4 in the Cooper’s review [

9]) [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. Indeed, the native state of small globular proteins is considered to be marginally more stable than the denatured state [

18,

19]. Similarly, careful investigations on the thermodynamic consequences of both point mutations of residues lining the binding cleft of several enzymes and of various structural modifications of several substrates and inhibitors have recorded large enthalpy and entropy changes, but always of the same sign, so that the effect on the Gibbs free energy change associated with binding has turned out to be small (i.e., the binding constant was little affected) [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. It should not be hard to imagine the frustration experienced by scientists trying to increase the affinity of an inhibitor for a given binding cleft because of the occurrence of enthalpy-entropy compensation.

Over the years, several authors have formulated several theoretical rationalizations of enthalpy-entropy compensation [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44], each of which has strengths and weaknesses. In the present review, we would like to show how a general theory of hydration, originally devised by Lee [

45,

46,

47,

48] and then widely applied and strengthened by one of us [

49,

50,

51,

52,

53], can rationalize, at the molecular level, the widespread diffusion of the phenomenon in processes occurring in water.

2. Theoretical Considerations

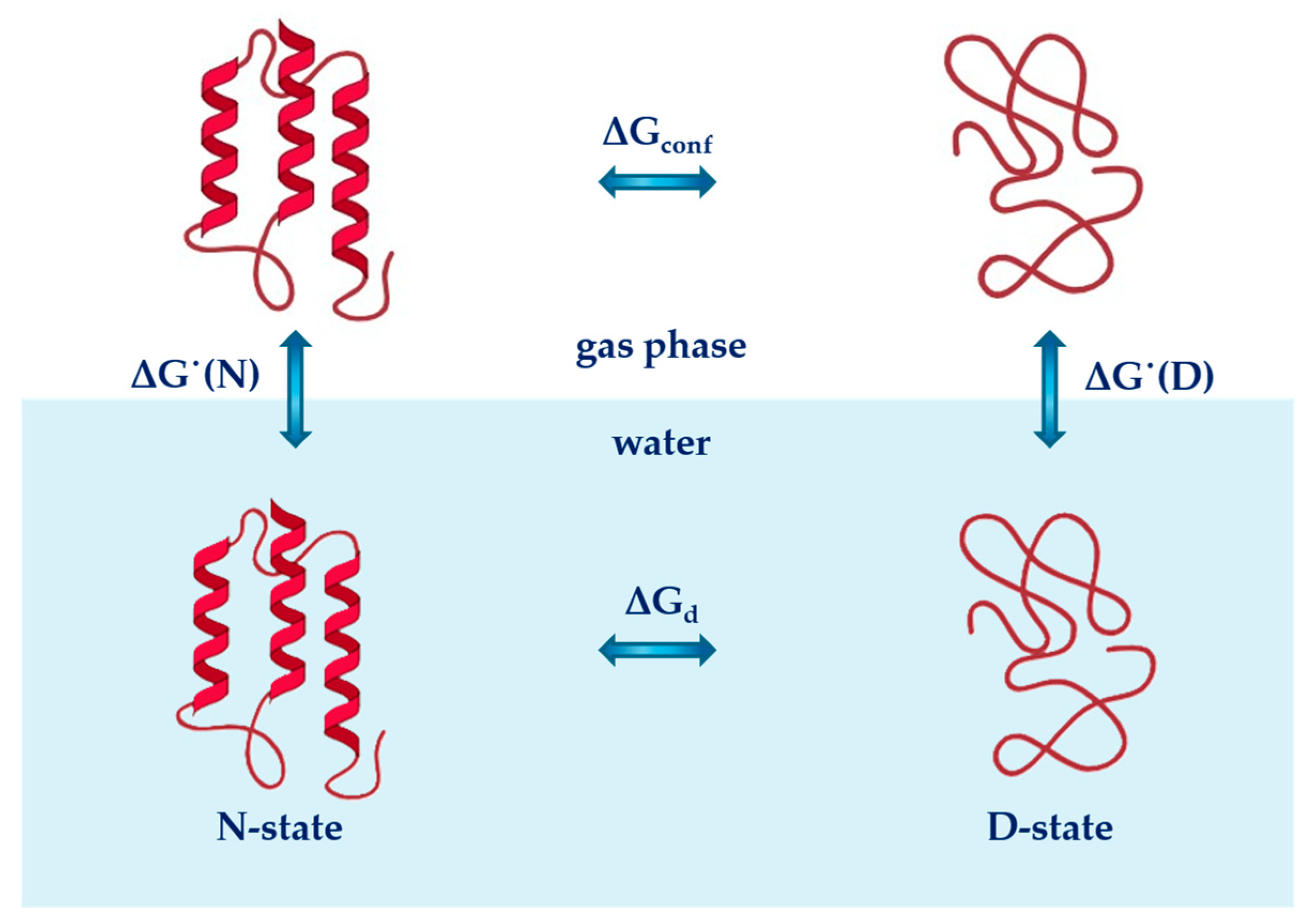

The conformational stability of globular proteins in water (in the assumption that only two macroscopic states, the native state N-state, and the denatured state D-state, are populated by polypeptide chains) can be analysed by means of the thermodynamic cycle reported in

Figure 1 [

51,

52]. The cycle leads to the following relationship:

where

is the Gibbs free energy change associated with protein unfolding in water or aqueous solution;

is the Gibbs free energy change associated with protein unfolding in the ideal gas phase; and ΔG˙(D) and ΔG˙(N) are the Gibbs free energy changes associated with the hydration (i.e., ideal gas-to-water transfer) of the D-state and N-state, respectively.

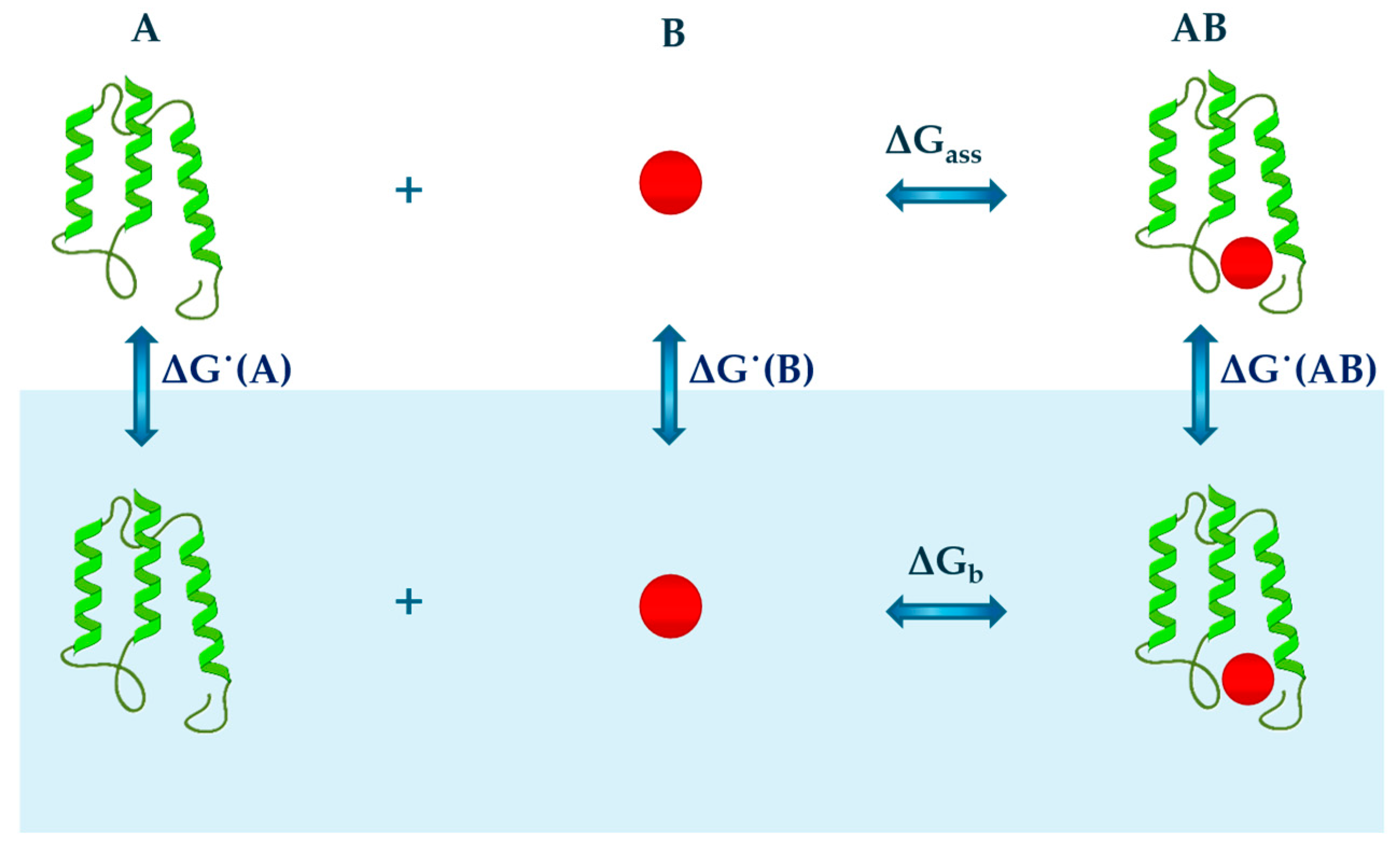

On the other hand, a bimolecular association in water between the A and B molecules can be analysed according to the thermodynamic cycle reported in

Figure 2 and described by the following relationship:

where

is the Gibbs free energy change associated with the binding process in water or aqueous solution;

is the Gibbs free energy change associated with the binding process in the ideal gas phase; and ΔG˙(AB), ΔG˙(A) and ΔG˙(B) are the Gibbs free energy changes associated with the hydration of the formed complex AB, the molecule A and the molecule B, respectively. A similar thermodynamic cycle can be used to analyse other processes that occur in water, such as the formation of micelles. These exempla highlight how hydration is an unavoidable step in the analysis of the processes occurring in water and, as such, requires a precise definition and particular attention. The statistical mechanical analysis done by Ben-Naim indicates that hydration must be defined as the transfer of a solute molecule, at constant temperature and pressure, from a fixed position in the ideal gas phase to a fixed position in liquid water [

54].

By using the Widom’s potential distribution theorem [

55,

56,

57], hydration can be treated as the action of an external perturbation on liquid water, Ψ(X), where X represents a multidimensional vector accounting for one of the possible configurations of water molecules in the system. The Ben-Naim standard hydration Gibbs free energy change is given by [

45]:

where the subscript p means that the ensemble average is done over the pure liquid configurations. The related probability density function, assuming an NPT ensemble, is given by the following relationship:

where H(

X) = U(

X) + P⋅V(

X) is the enthalpy function of one of the possible configurations, U(

X) and V(

X) are the corresponding intermolecular interaction energy and volume, respectively, and the denominator is the isobaric-isothermal configurational partition function of the pure liquid. The ensemble average of Eq. (3) is taken over the water configurations before the action of the perturbation (i.e., the Boltzmann weights in the average do not include Ψ(

X), which acts as a ghost).

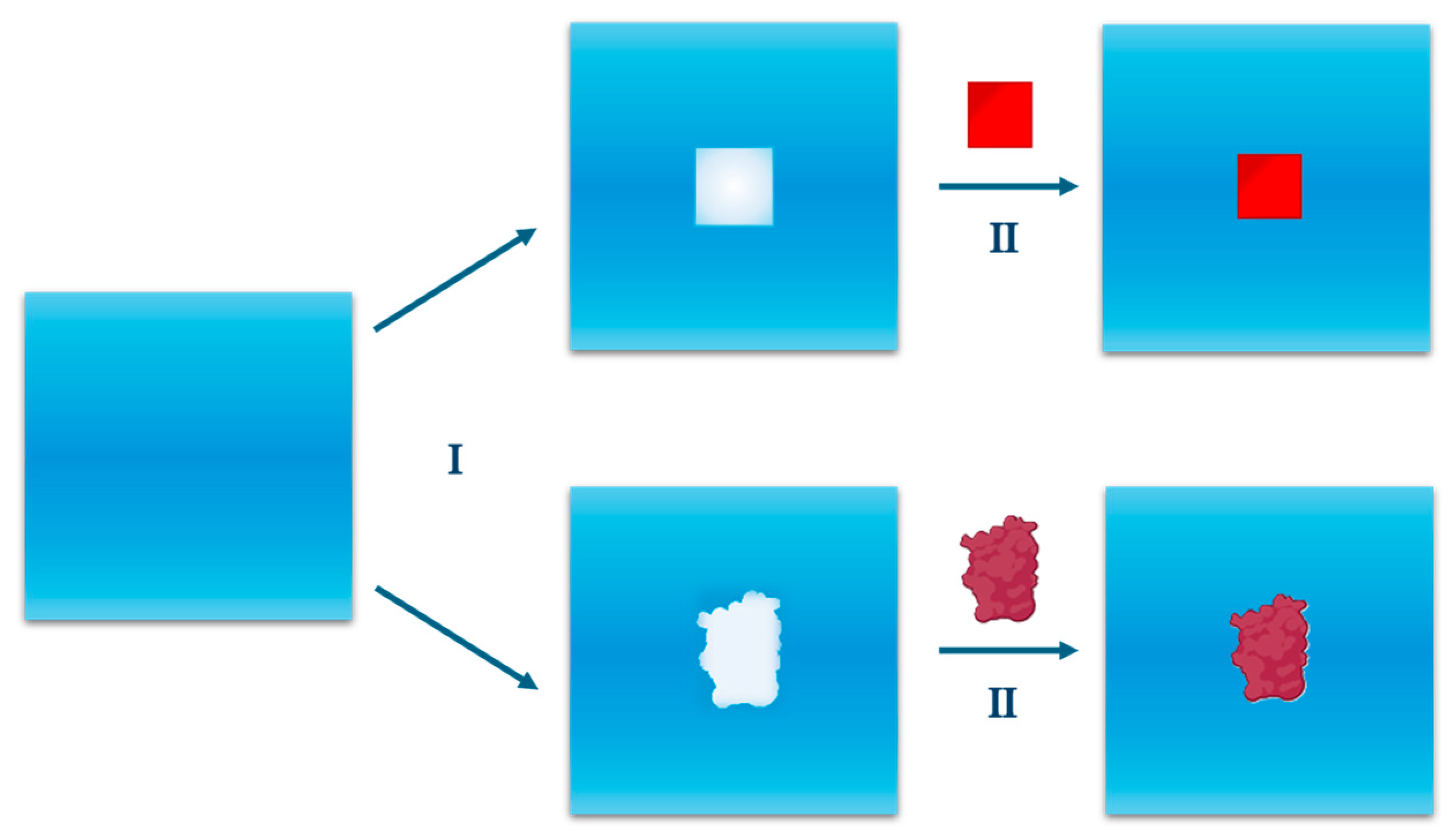

To shed light on the thermodynamics of hydration at the molecular level, it is advisable to break down the process into several steps that must have a clear physical meaning. Liquids are a condensed state of the matter, and the insertion of a solute molecule into water requires the exclusion of water molecules from the region of space that will be occupied by the solute. So, the first necessary step of hydration is the creation, at a fixed position in water, of a cavity suitable to be occupied by the solute molecule. Cavity creation is a theoretical process that cannot be investigated by means of experimental measurements; however, it is necessary to take into account the consequences of a simple but fundamental fact: each molecule has its own body. Following the cavity formation, a solute molecule interacts with water molecules by means of van der Waals attractions and/or H-bonds, depending on its chemical nature; it follows that the second step of hydration is the turning on the attractive potential. On the basis of these considerations, Lee suggested that the perturbation potential should be factorized in the following way [

45,

46]:

where

is a counting function, whose value is 1 when in a given water configuration there is a cavity suitable to be occupied by the solute molecule or is 0 when such a cavity does not exist in that configuration; and

represents the attractive potential between the solute molecule and the surrounding water molecules. By using Eq. (5), with a few straightforward passages, Eq. (3) becomes:

where the subscript c indicates that the ensemble average is done over the liquid configurations containing a cavity suitable to be occupied by the solute molecule. The related probability density function is given by:

According to Eq. (6), is the sum of two terms: (a) the reversible work to create the cavity, , and (b) the reversible work to turn on the attractive solute-water interactions, . It does not imply the addition of independent contributions, since intermolecular attractions are turned on after the cavity has already been created.

The so-called Widom’s inverse relationship [

56] allows a modification of Eq. (3), which becomes [

45,

46]:

where the subscript s signifies that the ensemble average is computed over the solution configurations that possess the cavity occupied by the solute molecule interacting with the surrounding solvent molecules. In this ensemble, the solute molecule does not act as a ghost, but interacts with water molecules; and the corresponding probability density function becomes:

The general caveat is that the Widom’s inverse relationship holds only if the perturbation Ψ(

X), required to create a cavity at a fixed position in a liquid, is not infinite [

46,

56], which is the case when the position is occupied by liquid molecules (i.e., for most liquid configurations). This mathematical condition and the physical considerations above imply that cavity creation is a particularly important process, which must constitute the starting point of any theoretical treatment of the hydration phenomenon. The two steps described, shown in

Figure 3, will be analysed in detail below.

2.1. Cavity Creation

The reversible work of cavity creation is the reversible work required to pick out the configurations containing the cavity in the overall set of the pure liquid configurations (please note: the spatial homogeneity of the liquid renders un-necessary to define an exact position of the cavity, except for the surface regions) [

58]:

Molecular-sized cavities occur in a liquid as a consequence of molecular-scale density fluctuations at equilibrium (such fluctuations can be studied by Monte Carlo or Molecular Dynamics computer simulations [

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64]). Density fluctuations cannot be studied on a lattice and, to use the cavity concept in lattice models, the reversible work of cavity creation must be associated with the energetic breaking of intermolecular bonds, the number of which depends on the lattice geometry [

65]. Unfortunately, this energetic description of the reversible work of cavity creation is simply not correct.

Direct application of equilibrium statistical mechanics leads to the following expressions for the enthalpy change,

, and the entropy change,

, associated with cavity creation:

and

By inserting the relationships of Eq. (4) and Eq. (7) in the integral of the first line of Eq. (12), it is not difficult to get to the expression in the second line. The difference in the average ensemble enthalpy between the liquid configurations possessing the desired cavity and the total liquid configurations gives rise to

. The change in the entropy associated with the cavity formation

consists of two contributions: (a) the solvent-excluded volume contribution

due to a loss in the number of configurations, which loss, since the liquid configurations containing the desired cavity represent a roughly infinitesimal fraction of the total liquid configurations, causes a large negative contribution to the entropy in any liquid, but especially in water by virtue of its large number density and the small size of its molecules [

45,

48,

53], two characteristics that overwhelm the small volume packing density of water; (b) a difference in the two ensembles of liquid configurations as those containing the cavity would have a different distribution of energy levels, whose contribution is distinct from that of the solvent-excluded volume and is totally compensated by the enthalpy change since the liquid configurations possessing the desired cavity are a subset of the total configurations of the pure liquid [

58].

Therefore, Equations (11) and (12) show that: (a)

is totally compensated by the entropy contribution of the non-solvent-excluded volume upon the cavity creation; (b)

has an entropic origin, since it arises from the effect of the solvent-excluded volume associated with the reduction in the size of the configuration space accessible to the solvent molecules:

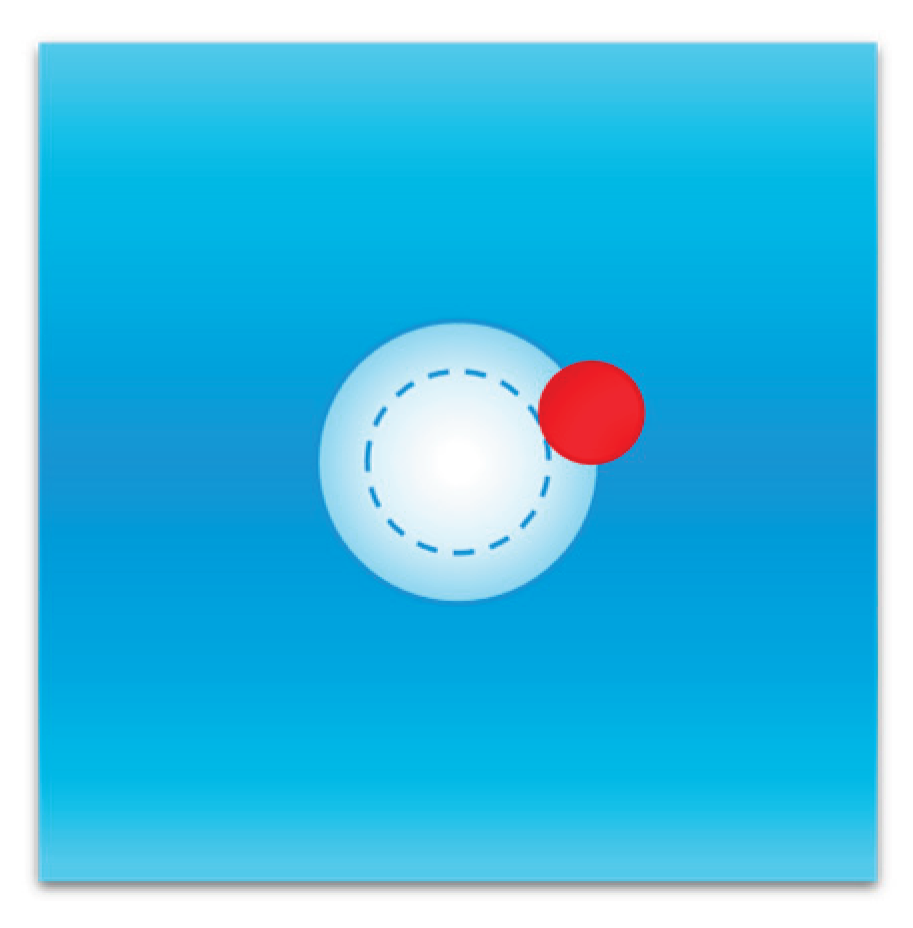

At this point a detailed explanation of the solvent-excluded volume effect is necessary. Holding the temperature and pressure fixed, liquid configurations having the suitable cavity will have a volume greater than the mean volume by an amount equal to the van der Waals volume of the cavity. This increase in liquid volume does not cancel the solvent-excluded volume effect for two closely related reasons: (a) the cavity must remain empty at the given fixed position to be occupied by the solute molecule; (b) this requirement implies that the centre of all liquid molecules cannot fit into the shell existing between the van der Waals surface of the cavity and the water-accessible surface of the cavity itself (the condition is shown in

Figure 4 for a spherical cavity). The geometric constraint holds for all liquid molecules since they are in continuous translational motion in the system volume (i.e., it does not exclusively affect the liquid molecules lining the surface of the cavity) and is strictly related to the fixed position of the cavity. This result has general validity given that each molecule has its own body, even though hard sphere fluid theories, such as classic scaled particle theory [

48,

53,

66], are exploited to perform analytic calculations.

2.2. Turning on the Attractive Solute-Water Interactions

The reversible work to turn on the attractive solute-water van der Waals potential is given by [

45]:

The application of the Gibbs-Helmholtz equation leads to:

The enthalpy change consists of two parts: the first is the average attractive solute-water van der Waals potential, excluding the effect of any solvent reorganization; the second is the enthalpy contribution arising from water reorganization upon the turning on the attractive solute-water van der Waals potential [

46,

48].

The entropy change is given by the following:

By setting

, expanding in power series the exponential function and recognizing that

, one obtains:

and the entropy change becomes:

The Gibbs free energy change is as follows:

The attractive solute-water van der Waals potential

is weak compared to the energetic strength of the tetrahedral H-bonding network of water, as well as the fluctuations in the value of

prove to be small. This implies that the second term on the right-hand side of Eq. (19) can be neglected and, hence, that the reorganization of water molecules associated with the turning on the attractive solute-water van der Waals potential is a compensatory process [

46,

48]. Indeed, in line with the expectations for a spontaneous process, this reorganization is characterized by a negative change in Gibbs free energy, albeit small [

50]. Therefore,

is almost equal to the attractive solute-water van der Waals energy, and the Gibbs free energy change results to be:

The overall change in Gibbs free energy due to hydration is:

Equation (21), although not exact, allows for direct calculations to test its validity. Its first application, by Pierotti in 1965 [

67], to the hydration of nonpolar species provided a remarkable agreement with experimental values of the Gibbs free energy change. This result was not expected at that time, when the dominant idea was that the poor solubility in water of nonpolar species was due to the formation of icebergs (see the famous pictorial iceberg model devised by Frank and Evans [

68,

69]). In reality, the success was a simple consequence of the enthalpy-entropy compensation that characterizes the structural reorganization of water-water H-bonds following the insertion of the solute. The analogue fortune of the integral equation theory devised by Pratt and Chandler in 1977 [

70] can be rationalized along the same lines.

The hydration enthalpy change is:

where

represents the enthalpy contribution due to the overall structural reorganization of the water-water H-bonds upon solute insertion, including both the cavity creation and the turning on the attractive solute-water van der Waals potential. The hydration entropy change is given by:

where

is the entropy contribution due to the overall structural reorganization of the water-water H-bonds upon solute insertion. It represents the water response to the external perturbation and is characterized by an almost complete enthalpy-entropy compensation, so it is possible approximate that:

This analysis highlights how the structural reorganization of water-water H-bonds is a compensatory process, provided that the attractive solute-water potential is weak compared to the energetic strength of the tetrahedral H-bonding network of water [

42,

43,

44,

45,

46]. This is a clear physical condition fulfilled by the hydration of noble gases, alkanes, benzene and toluene, but also by the hydration of n-alcohols (note that the perturbation produced by a single OH group is not so strong, according to the available structural and thermodynamic data [

71,

72]). The condition is also satisfied in the binding of substrates and inhibitors to proteins, since the burial of small surfaces by contact with water cannot produce a strong perturbation of water-water H-bonds. The situation does not change in the case of protein-protein association when large surfaces are buried, because of the presence in these of both polar and nonpolar groups, both positive and negative charges, whose overall effect on the structure of the water results to be not so strong due to balancing effects.

One last point deserves attention. The hydration heat capacity change

, based on Eq. (22), results to be:

Since the temperature dependence of

is small [

73], the large positive

associated with several processes occurring in water (e.g., hydration of non-charged species, unfolding of small globular proteins) is mainly caused by the structural reorganization of water-water H-bonds [

45,

46,

47,

48,

74,

75,

76,

77]. This clarifies why the temperature dependence of the enthalpy and entropy changes associated with such processes is almost entirely compensatory [

9,

46].

3. Structural Analysis

The thermodynamic functions associated with the reorganization of water-water H-bonds can be calculated by means of a model based on the structural and energetic features of water-water H-bonds. Long ago, Pauling [

78] provided an estimate of the energy required to break a H-bond in water, E(H-bond) = 20.9 kJ mol

-1. This estimate can be used to arrive at the corresponding vibration frequency. In the harmonic approximation, the force constant

k can be calculated from the relationship:

k = 2⋅β

2⋅E(H-bond), where β is the constant occurring in the Morse potential [

79]. Using the customary value β = 2⋅10

10 m

-1, it turns out that

k = 27.8 N m

-1, ω = 162 cm

-1 and ν = 4.86⋅10

12 Hz [

35]. The THz frequency, inserted into the statistical mechanical expression of the entropy associated with the energy levels of the harmonic oscillator (HO) [

79], leads to S(HO) = 10.6 J K

-1mol

-1 at 300 K. Dunitz [

35] assumed that the three degrees of freedom corresponding to the intramolecular vibrational modes of a water molecule are not excited at room temperature (because their frequencies are too high), whereas the other six degrees of freedom can be described as vibrational modes of the 3D H-bonded lattice constituted by all the water molecule, which modes are all characterized by the same entropy calculated above. Therefore, the overall entropy contribution, at 300 K, would be 6⋅T⋅S(HO) = 19.1 kJ mol

-1 and would almost compensate for the energetic term E(H-bond) = 20.9 kJ mol

-1. Dunitz used this calculation to provide a rationalization of the enthalpy-entropy compensation detected for bimolecular association processes occurring in water [

35], which has been widely accepted [

10,

29].

In contrast, we think that the meaning of this simple exercise could be different: a structural reorganization of water-water H-bonds (associated with any processes that occurs in water) would cause a small modification in both the energy levels and their relative population, leading to a large enthalpy-entropy compensation. Actually, it has been shown long time ago, by Lee and Graziano for the hydration of alkanes [

47] and by Graziano for the hydration of noble gases [

80] and n-alcohols [

81], that a properly modified version of the two-state model developed by Muller to describe the structural reorganization of water-water H-bonds [

82], by distinguishing the hydration shell water from the bulk water, is able to provide compensatory changes in enthalpy and entropy. The reliability of this model has been confirmed by its ability to reproduce a temperature dependence of the hydration heat capacity change in line with experimental data [

83,

84].

The rightness of our interpretation is supported by the Ford’s analysis [

85]. Ford showed that enthalpy-entropy compensation is not a general feature of bimolecular associations in the gas phase, suggesting that the real cause is not the weakness of intermolecular interactions, but the characteristics of the structural reorganization of water-water H-bonds.

However, it is important to emphasize that the exercise devised by Dunitz [

35], although simple, is more accurate than one might imagine at first glance. Raman spectra of liquid water in the THz frequency region show the presence of a band centred at 60 cm

-1 and another wide band centred at 175 cm

-1 [

86,

87]. Walrafen assigned the first band to the transverse acoustic modes and the second band to the longitudinal acoustic modes of the 3D H-bonded (and disordered) lattice of liquid water, which “behaves like a moderately rigid, isotropic, elastic solid at THz frequencies” [

86]. The frequency range covered by these two bands corresponds to the various estimates of the H-bond energy strength existing in the literature [

47,

82,

83,

88,

89] and indicates that the structural reorganization of water-water H-bonds associated with the hydration step of processes occurring in water should be characterized by an almost complete enthalpy-entropy compensation.

4. Conclusions

Enthalpy-entropy compensation is a phenomenon that characterizes most processes occurring in water and aqueous solutions. In order to provide a rationalization, in this work we have shown that: (a) hydration must always be a step of thermodynamic cycles that can be used to analyse the process of interest; (b) a general theory of hydration, already widely accepted, indicates that the structural rearrangement of water-water H-bonds (i.e., the response of water to the perturbation caused by solute insertion) is compensatory, as long as the energetic strength of the solute-water attraction is weak compared to the energetic strength of water-water H-bonds; (c) a modified version of the Muller’s model is able to describe the structural reorganization of water-water H-bonds, reproducing compensatory enthalpy and entropy changes; (d) water is special with respect to enthalpy-entropy compensation, because the cooperativity of its 3D H-bonded network is such that even solute-water attractions, consisting of H-bonds, result to be weak.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.G.; methodology, G.G. and F.M.; writing—original draft preparation, F.M. and G.G.; writing—review and editing, F.M. and G.G.; visualization, F.M. and G.G.; supervision, G.G.; project administration, G.G.; funding acquisition, G.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analysed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HO |

Harmonic oscillator |

| NPT |

Isothermal-isobaric canonical ensemble |

References

- Exner, O. The Enthalpy-Entropy Relationship. In Progress in Physical Organic Chemistry; Streitwieser, A., Taft, R.W., Eds.; Wiley, 1973; Vol. 10, pp. 411–482 ISBN 978-0-471-83356-7.

- Krug, R.R.; Hunter, W.G.; Grieger, R.A. Statistical Interpretation of Enthalpy-Entropy Compensation. Nature 1976, 261, 566–567. [CrossRef]

- Exner, O. How to Get Wrong Results from Good Experimental Data: A Survey of Incorrect Applications of Regression. Journal of Physical Organic Chemistry 1997, 10, 797–813. [CrossRef]

- Cornish-Bowden, A. Enthalpy—Entropy Compensation: A Phantom Phenomenon. J Biosci 2002, 27, 121–126. [CrossRef]

- Qian, H. An Asymptotic Comparative Analysis of the Thermodynamics of Non-Covalent Association. J. Math. Biol. 2006, 52, 277–289. [CrossRef]

- Griessen, R.; Dam, B. Simple Accurate Verification of Enthalpy-Entropy Compensation and Isoequilibrium Relationship. ChemPhysChem 2021, 22, 1774–1784. [CrossRef]

- Lumry, R.; Rajender, S. Enthalpy-Entropy Compensation Phenomena in Water Solutions of Proteins and Small Molecules: A Ubiquitous Property of Water. Biopolymers 1970, 9, 1125–1227.

- Liu, L.; Guo, Q.X. Isokinetic Relationship, Isoequilibrium Relationship, and Enthalpy-Entropy Compensation. Chem.Rev 2001, 101, 673–696.

- Cooper, A.; Johnson, C.M.; Lakey, J.H.; Nöllmann, M. Heat Does Not Come in Different Colours: Entropy-Enthalpy Compensation, Free Energy Windows, Quantum Confinement, Pressure Perturbation Calorimetry, Solvation and the Multiple Causes of Heat Capacity Effects in Biomolecular Interactions. Biophys Chem 2001, 93, 215–230. [CrossRef]

- Chodera, J.D.; Mobley, D.L. Entropy-Enthalpy Compensation: Role and Ramifications in Biomolecular Ligand Recognition and Design. Annu Rev Biophys 2013, 42, 121–142. [CrossRef]

- Movileanu, L.; Schiff, E.A. Entropy–Enthalpy Compensation of Biomolecular Systems in Aqueous Phase: A Dry Perspective. Monatsh Chem 2013, 144, 59–65. [CrossRef]

- Dragan, A.I.; Read, C.M.; Crane-Robinson, C. Enthalpy–Entropy Compensation: The Role of Solvation. Eur Biophys J 2017, 46, 301–308. [CrossRef]

- Makhatadze, G.I.; Privalov, P.L. Energetics of Protein Structure. Adv Protein Chem 1995, 47, 307–425. [CrossRef]

- Robertson, A.D.; Murphy, K.P. Protein Structure and the Energetics of Protein Stability. Chem. Rev. 1997, 97, 1251–1268. [CrossRef]

- Rees, D.C.; Robertson, A.D. Some Thermodynamic Implications for the Thermostability of Proteins. Protein Sci 2001, 10, 1187–1194. [CrossRef]

- Sawle, L.; Ghosh, K. How Do Thermophilic Proteins and Proteomes Withstand High Temperature? Biophysical Journal 2011, 101, 217–227. [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, T.P. The Hydrophobic Effect: Is Water Afraid, or Just Not That Interested? ChemTexts 2020, 6, 26. [CrossRef]

- P.L. Privalov. Annu.Rev.Biophys.Biophys.Chem 1989, 18, 47–69.

- Pica, A.; Graziano, G. Shedding Light on the Extra Thermal Stability of Thermophilic Proteins. Biopolymers 2016, 105, 856–863. [CrossRef]

- Eftink, M.R.; Anusiem, A.C.; Biltonen, R.L. Enthalpy-Entropy Compensation and Heat Capacity Changes for Protein-Ligand Interactions: General Thermodynamic Models and Data for the Binding of Nucleotides to Ribonuclease A. Biochemistry 1983, 22, 3884–3896. [CrossRef]

- Kurioki, R.; Nitta, K.; Yutani, K. J.Biol.Chem 1992, 267, 24297–24301.

- Gilli, P.; Ferretti, V.; Gilli, G.; Borea, P.A. Enthalpy-Entropy Compensation in Drug-Receptor Binding. J. Phys. Chem. 1994, 98, 1515–1518. [CrossRef]

- Talhout, R.; Villa, A.; Mark, A.E.; Engberts, J.B.F.N. Understanding Binding Affinity: A Combined Isothermal Titration Calorimetry/Molecular Dynamics Study of the Binding of a Series of Hydrophobically Modified Benzamidinium Chloride Inhibitors to Trypsin. J Am Chem Soc 2003, 125, 10570–10579. [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, V.M.; Bohall, B.R.; Semetey, V.; Whitesides, G.M. The Paradoxical Thermodynamic Basis for the Interaction of Ethylene Glycol, Glycine, and Sarcosine Chains with Bovine Carbonic Anhydrase II: An Unexpected Manifestation of Enthalpy/Entropy Compensation. J Am Chem Soc 2006, 128, 5802–5812. [CrossRef]

- Lafont, V.; Armstrong, A.A.; Ohtaka, H.; Kiso, Y.; Mario Amzel, L.; Freire, E. Compensating Enthalpic and Entropic Changes Hinder Binding Affinity Optimization. Chemical Biology & Drug Design 2007, 69, 413–422. [CrossRef]

- Ward, J.M.; Gorenstein, N.M.; Tian, J.; Martin, S.F.; Post, C.B. Constraining Binding Hot Spots: NMR and Molecular Dynamics Simulations Provide a Structural Explanation for Enthalpy−Entropy Compensation in SH2−Ligand Binding. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 11058–11070. [CrossRef]

- Olsson, T.S.G.; Ladbury, J.E.; Pitt, W.R.; Williams, M.A. Extent of Enthalpy-Entropy Compensation in Protein-Ligand Interactions. Protein Sci 2011, 20, 1607–1618. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Helms, V.; Lengauer, T.; Kalinina, O.V. Enthalpy–Entropy Compensation upon Molecular Conformational Changes. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015, 11, 1410–1418. [CrossRef]

- Fox, J.M.; Zhao, M.; Fink, M.J.; Kang, K.; Whitesides, G.M. The Molecular Origin of Enthalpy/Entropy Compensation in Biomolecular Recognition. Annu Rev Biophys 2018, 47, 223–250. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Naim, A. Hydrophobic Interaction and Structural Changes in the Solvent. Biopolymers 1975, 14, 1337–1355.

- Lumry, R.; Battistel, E.; Jolicoeur, C. Geometric Relaxation in Water. Its Role in Hydrophobic Hydration. Faraday Symp. Chem. Soc. 1982, 17, 93–108. [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.-A.; Karplus, M. A Thermodynamic Analysis of Solvation. Journal of Chemical Physics 1988, 89, 2366–2379. [CrossRef]

- Grunwald, E.; Steel, C. Solvent Reorganization and Thermodynamic Enthalpy-Entropy Compensation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 5687–5692. [CrossRef]

- Searle, M.S.; Westwell, M.S.; Williams, D.H. Application of a Generalised Enthalpy-Entropy Relationship to Binding Co-Operativity and Weak Associations in Solution. Journal of the Chemical Society, Perkin Transactions 2 1995, 141–151. [CrossRef]

- Dunitz, J.D. Win Some, Lose Some: Enthalpy-Entropy Compensation in Weak Intermolecular Interactions. Chemistry & Biology 1995, 2, 709–712. [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Hopfield, J.J. Entropy-enthalpy Compensation: Perturbation and Relaxation in Thermodynamic Systems. The Journal of Chemical Physics 1996, 105, 9292–9298. [CrossRef]

- Qian, H. Entropy-Enthalpy Compensation: Conformational Fluctuation and Induced-Fit. The Journal of Chemical Physics 1998, 109, 10015–10017. [CrossRef]

- Gallicchio, E.; Kubo, M.M.; Levy, R.M. Entropy−Enthalpy Compensation in Solvation and Ligand Binding Revisited. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 4526–4527. [CrossRef]

- Sharp, K. Entropy-Enthalpy Compensation: Fact or Artifact? Protein Sci 2001, 10, 661–667. [CrossRef]

- Starikov, E.B.; Nordén, B. Enthalpy-Entropy Compensation: A Phantom or Something Useful? J Phys Chem B 2007, 111, 14431–14435. [CrossRef]

- Douglas, J.F.; Dudowicz, J.; Freed, K.F. Crowding Induced Self-Assembly and Enthalpy-Entropy Compensation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 103, 135701. [CrossRef]

- Freed, K.F.; Freed, K.F. Entropy-Enthalpy Compensation in Chemical Reactions and Adsorption: An Exactly Solvable Model. Journal of Physical Chemistry. B 2011, 115, 1689–1692. [CrossRef]

- Starikov, E.B.; Nordén, B. Entropy–Enthalpy Compensation as a Fundamental Concept and Analysis Tool for Systematical Experimental Data. Chemical Physics Letters 2012, 538, 118–120. [CrossRef]

- Ryde, U. A Fundamental View of Enthalpy–Entropy Compensation. Med. Chem. Commun. 2014, 5, 1324–1336. [CrossRef]

- Lee, B. Solvent Reorganization Contribution to the Transfer Thermodynamics of Small Nonpolar Molecules. Biopolymers 1991, 31, 993–1008. [CrossRef]

- Lee, B. Enthalpy-entropy compensation in the thermodynamics of hydrophobicity. Biophys.Chem 1994, 51, 271–278.

- Lee, B.; Graziano, G. A Two-State Model of Hydrophobic Hydration That Produces Compensating Enthalpy and Entropy Changes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 5163–5168. [CrossRef]

- Graziano, G.; Lee, B. Hydration of Aromatic Hydrocarbons. J. Phys. Chem. B 2001, 105, 10367–10372. [CrossRef]

- Graziano, G. Case study of enthalpy-entropy non-compensation. J.Chem.Phys 2004, 120, 4467–4471.

- Graziano, G. Benzene Solubility in Water: A Reassessment. Chemical Physics Letters 2006, 429, 114–118. [CrossRef]

- Graziano, G. On the Molecular Origin of Cold Denaturation of Globular Proteins. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2010, 12, 14245–14252. [CrossRef]

- Graziano, G. On the Mechanism of Cold Denaturation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 21755–21767. [CrossRef]

- Graziano, G. Contrasting the Hydration Thermodynamics of Methane and Methanol. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 21418–21430. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Naim, A. Solvation Thermodynamics; Plenum Press: New York, 1987;

- Widom, B. Some Topics in the Theory of Fluids. The Journal of Chemical Physics 1963, 39, 2808–2812. [CrossRef]

- Widom, B. Potential-Distribution Theory and the Statistical Mechanics of Fluids. J. Phys. Chem. 1982, 86, 869–872. [CrossRef]

- Hansen, J.P.; McDonald, I.R. Theory of Simple Liquids; 3rd ed.; Academic Press, 2005;

- Lee, B. A Procedure for Calculating Thermodynamic Functions of Cavity Formation from the Pure Solvent Simulation Data. The Journal of Chemical Physics 1985, 83, 2421–2425. [CrossRef]

- Hummer, G.; Garde, S.; García, A.E.; Paulaitis, M.E.; Pratt, L.R. Hydrophobic Effects on a Molecular Scale. J. Phys. Chem. B 1998, 102, 10469–10482. [CrossRef]

- Pratt, L.R.; Pohorille, A. Theory of Hydrophobicity: Transient Cavities in Molecular Liquids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1992, 89, 2995–2999. [CrossRef]

- Madan, B.; Lee, B. Role of Hydrogen Bonds in Hydrophobicity: The Free Energy of Cavity Formation in Water Models with and without the Hydrogen Bonds. Biophysical Chemistry 1994, 51, 279–289. [CrossRef]

- Ashbaugh, H.S.; Pratt, L.R. Contrasting Nonaqueous against Aqueous Solvation on the Basis of Scaled-Particle Theory. J Phys Chem B 2007, 111, 9330–9336. [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.J.; Varilly, P.; Chandler, D.; Garde, S. Quantifying Density Fluctuations in Volumes of All Shapes and Sizes Using Indirect Umbrella Sampling. J.Stat.Phys 2011, 145, 265–275.

- Sosso, G.C.; Caravati, S.; Rotskoff, G.; Vaikuntanathan, S.; Hassanali, A. On the Role of Nonspherical Cavities in Short Length-Scale Density Fluctuations in Water, J.Phys.Chem.A 121 2017, 370–380.

- Dill, K.A.; Bromberg, S. Molecular Driving Forces: Statistical Thermodynamics in Chemistry and Biology; 1st ed.; Garland Science: New York, NY, 2003; ISBN 978-0-8153-2051-7.

- Reiss, H. Scaled Particle Methods in the Statistical Thermodynamics of Fluids. In Advances in Chemical Physics; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 1965; pp. 1–84 ISBN 978-0-470-14355-1.

- Pierotti, R.A. Aqueous solutions of nonpolar gases. J.Phys.Chem 1965, 69, 281–288.

- Frank, H.S.; Evans, M.W. Free Volume and Entropy in Condensed Systems. III. Entropy in Binary Liquid Mixtures; Partial Molal Entropy in Dilute Solutions; Structure and Thermodynamics in Aqueous Electrolytes. J.Chem.Phys 1945, 13, 507–532.

- Graziano, G. Comment on “Water’s Structure around Hydrophobic Solutes and the Iceberg Model.” J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 118, 2598–2599. [CrossRef]

- Pratt, L.R.; Chandler, D. Theory of the Hydrophobic Effect. J.Chem.Phys 1977, 67, 3683–3704.

- Juurinen, I.; Pylkkänen, T.; Sahle, C.J.; Simonelli, L.; Hämäläinen, K.; Huotari, S.; Hakala, M. Effect of the Hydrophobic Alcohol Chain Length on the Hydrogen-Bond Network of Water. J. Phys. Chem. B 2014, 118, 8750–8755. [CrossRef]

- Fidler, J.; Rodger, P.M. Solvation Structure around Aqueous Alcohols. J. Phys. Chem. B 1999, 103, 7695–7703. [CrossRef]

- Guillot, B.; Guissani, Y. A Computer Simulation Study of the Temperature Dependence of the Hydrophobic Hydration. J.Chem.Phys 1993, 99, 8075–8094.

- Cooper, A. Heat Capacity of Hydrogen-Bonded Networks: An Alternative View of Protein Folding Thermodynamics. Biophys Chem 2000, 85, 25–39. [CrossRef]

- Cooper, A. Heat Capacity Effects in Protein Folding and Ligand Binding: A Re-Evaluation of the Role of Water in Biomolecular Thermodynamics. Biophys Chem 2005, 115, 89–97. [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, K.R.; Sharp, K.A. A New Angle on Heat Capacity Changes in Hydrophobic Solvation. J Am Chem Soc 2003, 125, 9853–9860. [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, N.V.; Sharp, K.A. Heat Capacity in Proteins. Annu Rev Phys Chem 2005, 56, 521–548. [CrossRef]

- Pauling, L. The Nature of the Chemical Bond and the Structure of Molecules and Crystals: An Introduction to Modern Structural Chemistry; p. 468; 3rd ed.; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, 1960; ISBN 978-0-8014-0333-0.

- McQuarrie, D.A. Statistical Mechanics; Harper & Row: New York, 1976;

- Graziano, G. On the Temperature Dependence of Hydration Thermodynamics for Noble Gases. Phys.Chem.Chem.Phys 1999, 1, 1877–1886.

- Graziano, G. Hydration Thermodynamics of Aliphatic Alcohols. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 1999, 1, 3567–3576. [CrossRef]

- Muller, N. Search for a Realistic View of Hydrophobic Effects. Acc. Chem. Res. 1990, 23, 23–28. [CrossRef]

- Graziano, G.; Lee, B. On the Intactness of Hydrogen Bonds around Nonpolar Solutes Dissolved in Water. J Phys Chem B 2005, 109, 8103–8107. [CrossRef]

- Graziano, G. Structural Order in the Hydration Shell of Nonpolar Groups versus That in Bulk Water. ChemPhysChem 2024, 25, e202400102. [CrossRef]

- Ford, D.M. Enthalpy−Entropy Compensation Is Not a General Feature of Weak Association. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 16167–16170. [CrossRef]

- Walrafen, G.E. Raman Spectrum of Water: Transverse and Longitudinal Acoustic Modes below .Apprxeq.300 Cm-1 and Optic Modes above .Apprxeq.300 Cm-1. J. Phys. Chem. 1990, 94, 2237–2239. [CrossRef]

- Heyden, M.; Sun, J.; Funkner, S.; Mathias, G.; Forbert, H.; Havenith, M.; Marx, D. Dissecting the THz Spectrum of Liquid Water from First Principles via Correlations in Time and Space. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2010, 107, 12068–12073. [CrossRef]

- Hare, D.E.; Sorensen, C.M. Raman Spectroscopic Study of Dilute HOD in Liquid H2O in the Temperature Range − 31.5 to 160 °C. The Journal of Chemical Physics 1990, 93, 6954–6961. [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, K.A.T.; Haymet, A.D.J.; Dill, K.A. The Strength of Hydrogen Bonds in Liquid Water and Around Nonpolar Solutes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 8037–8041. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).