Submitted:

02 June 2025

Posted:

03 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

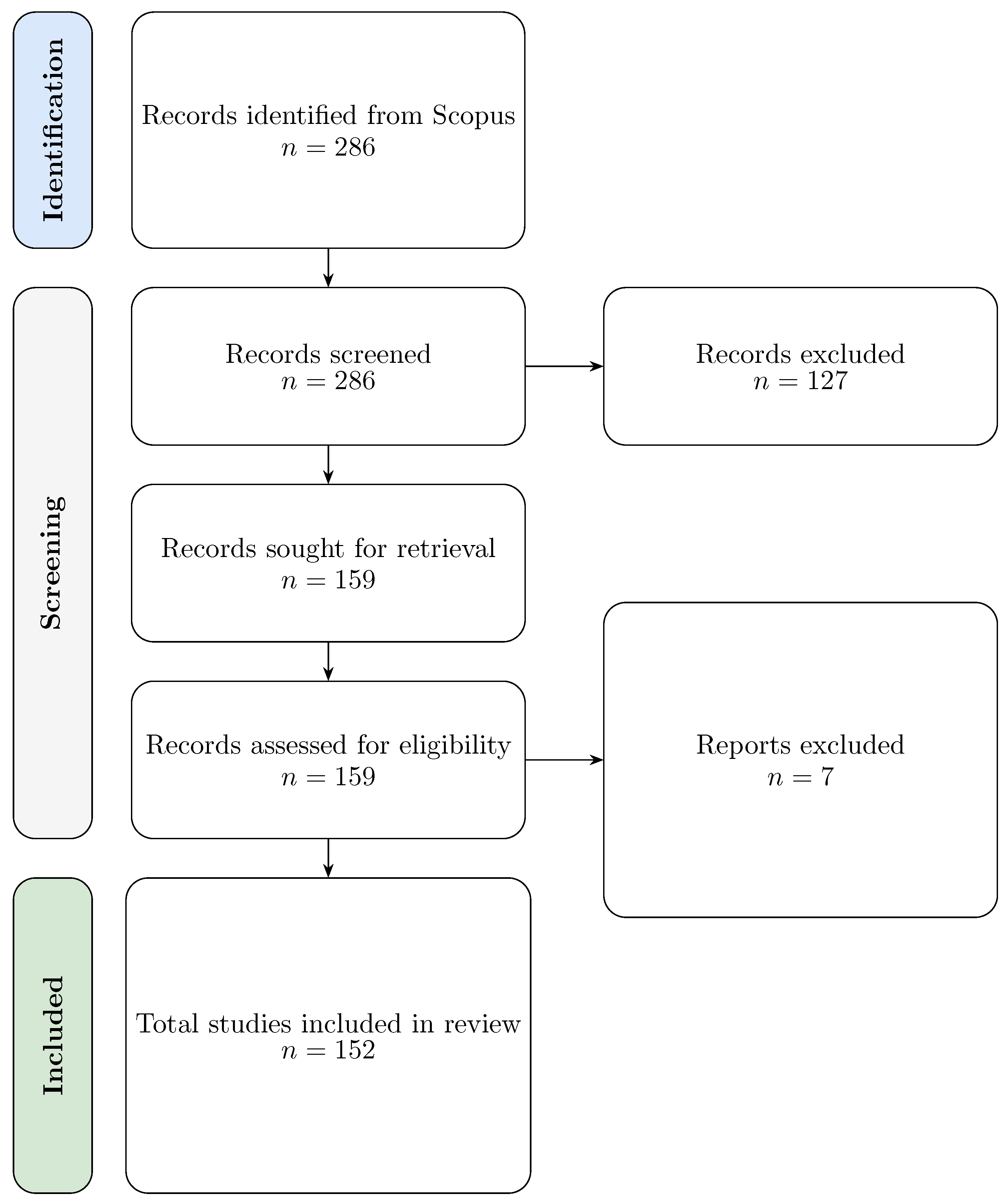

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

3. Background

3.1. Time Series

3.1.1. Components of a Time Series

3.1.2. Methods of Time Series Analysis

3.2. Deep Learning

3.2.1. A Brief History

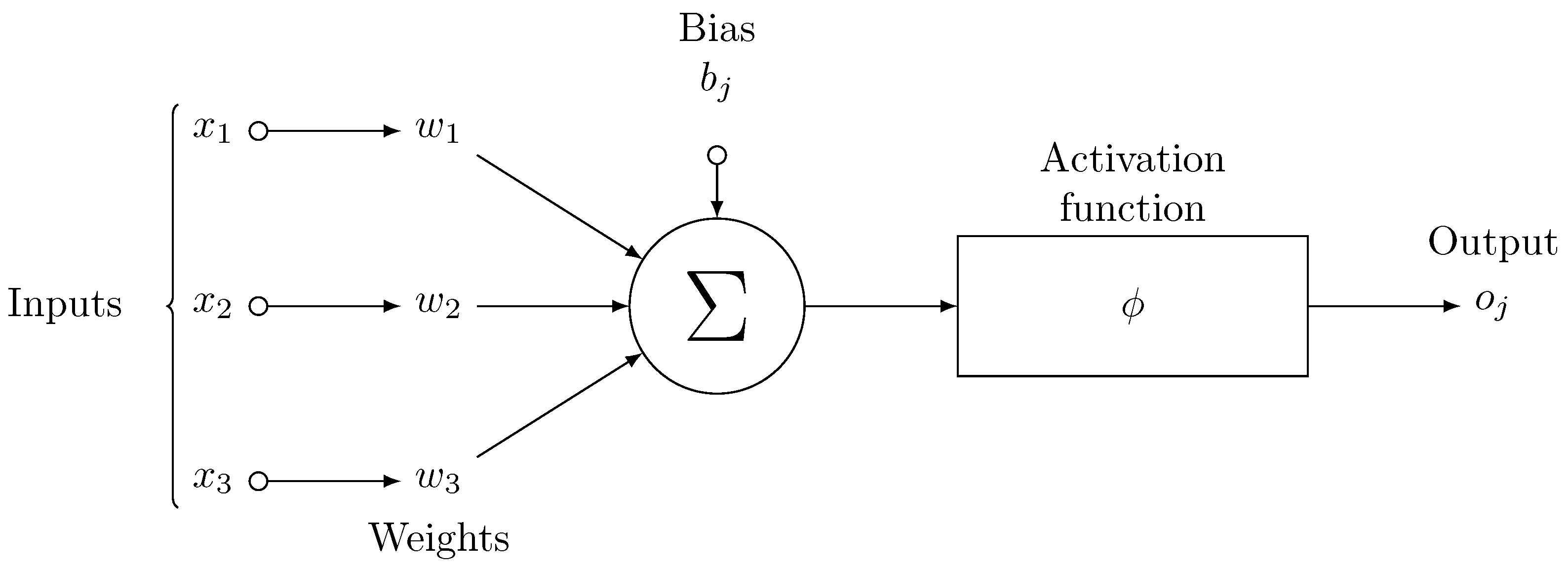

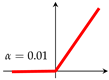

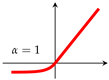

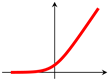

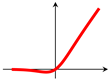

3.2.2. Artificial Neuron

3.3. Artificial Neural Network

3.3.1. Learning in Neural Networks

3.3.2. Regularization

3.3.3. Update of Network Parameters

4. Foundational Architectures

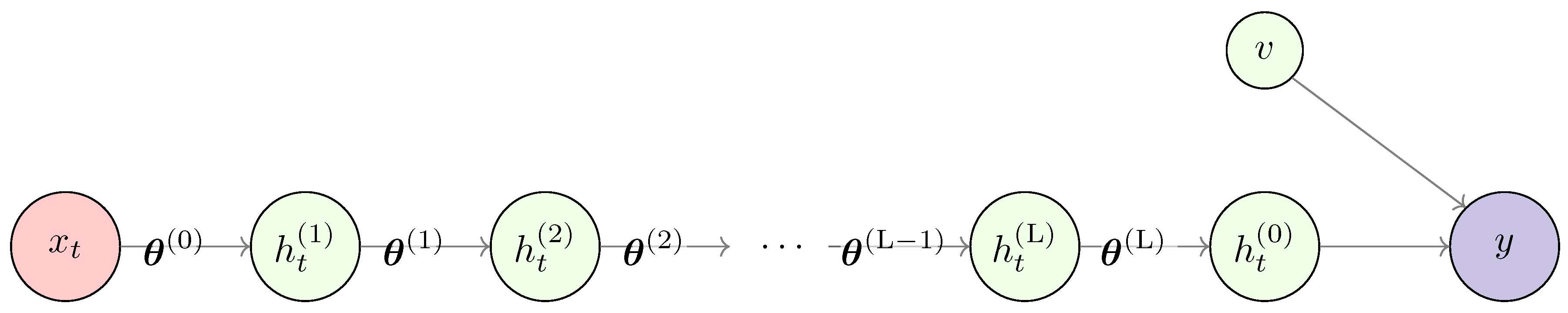

4.1. Multilayer Perceptrons

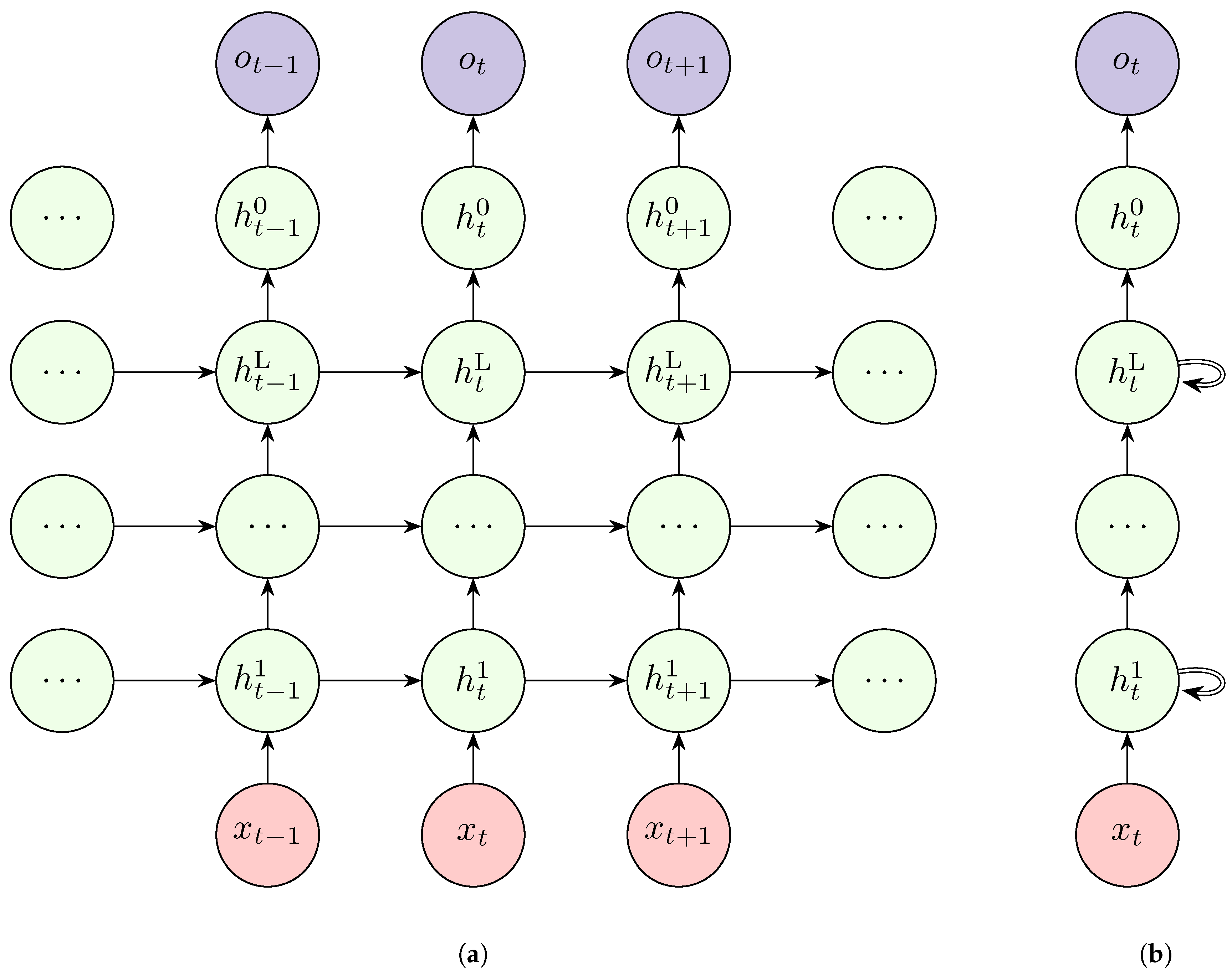

4.2. Recurrent Neural Networks

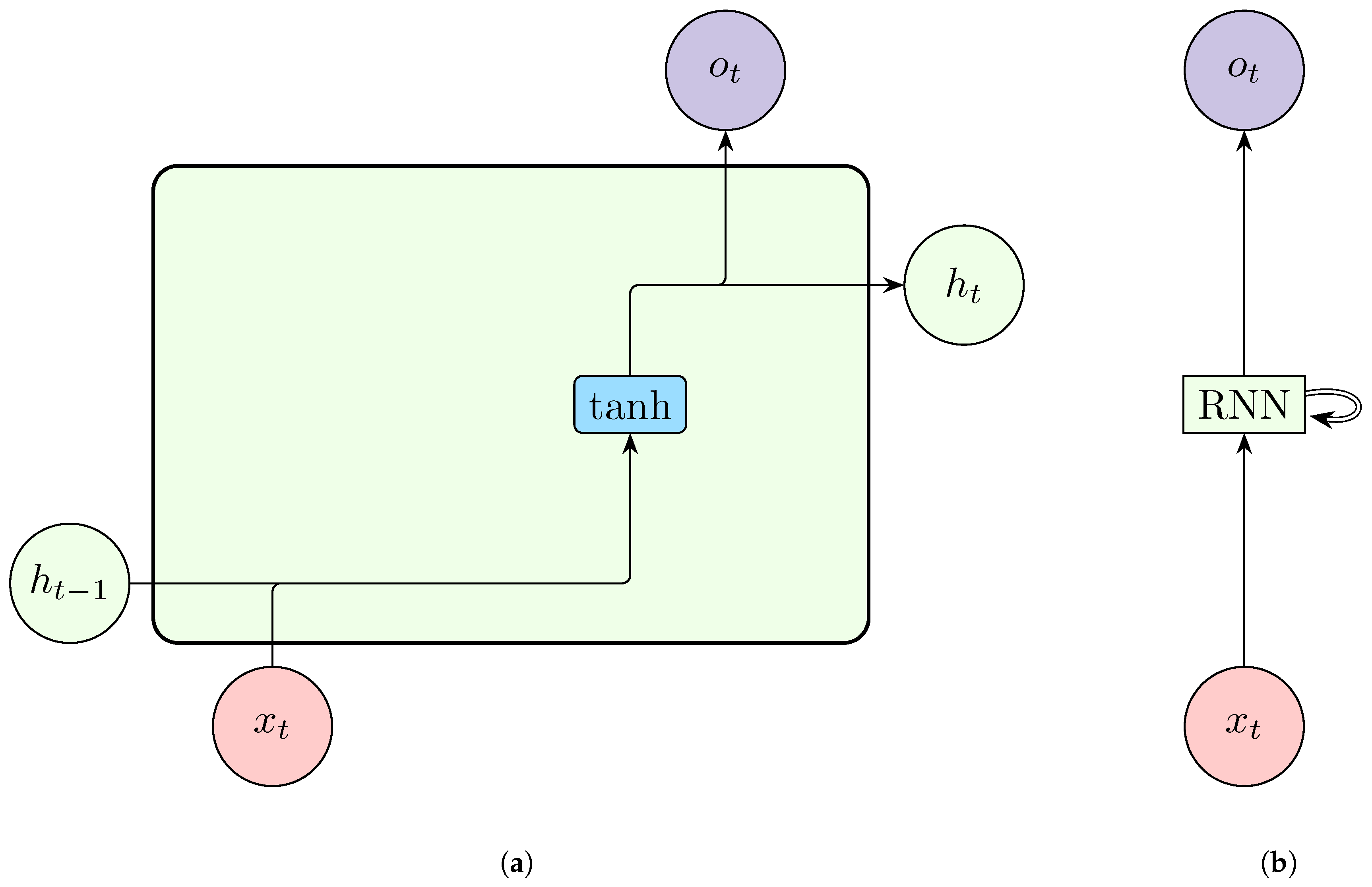

4.2.1. Simple RNNs

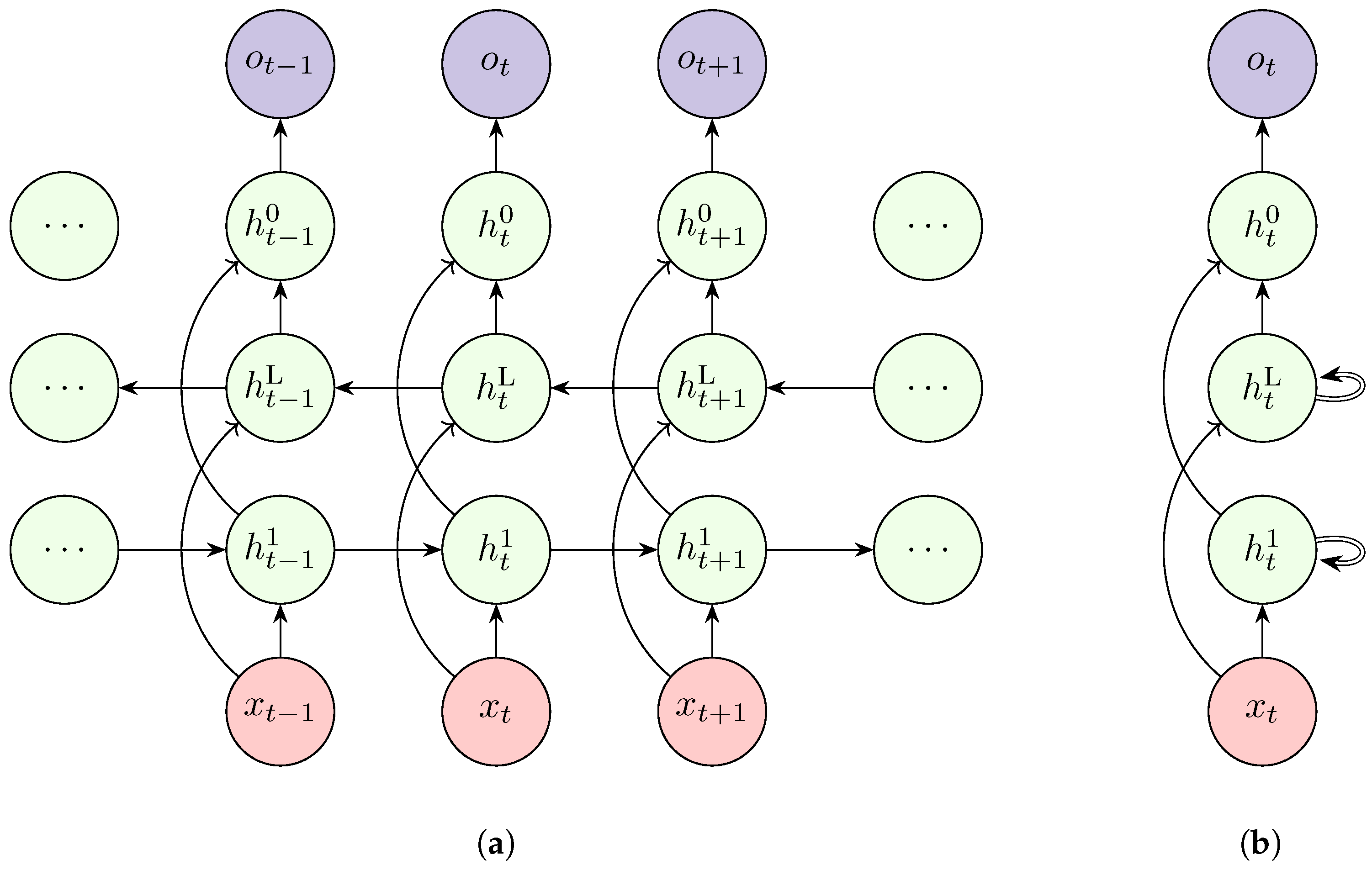

4.2.2. Deep RNN

4.2.3. Bidirectional RNN

4.3. Comparisons of Standards RNNs

| Aspect | Simple RNN | Deep RNN | Bidirectional RNN |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temporal direction | Forward only | Forward only | Both |

| Long-term memory | Poor | Improved | Strong (non-causal) |

| Depth and abstraction | Shallow | Hierarchical | Context-rich |

| Suitability for forecasting | Online / short horizon | Long horizon forecasting | Not suitable for real-time use |

| Computation and training | Efficient, stable | Expensive, harder to train | High overhead |

| Best use case | Basic time series tasks | Multiscale or nonlinear time series | Offline classification or anomaly detection |

4.4. Shortfalls of RNNs

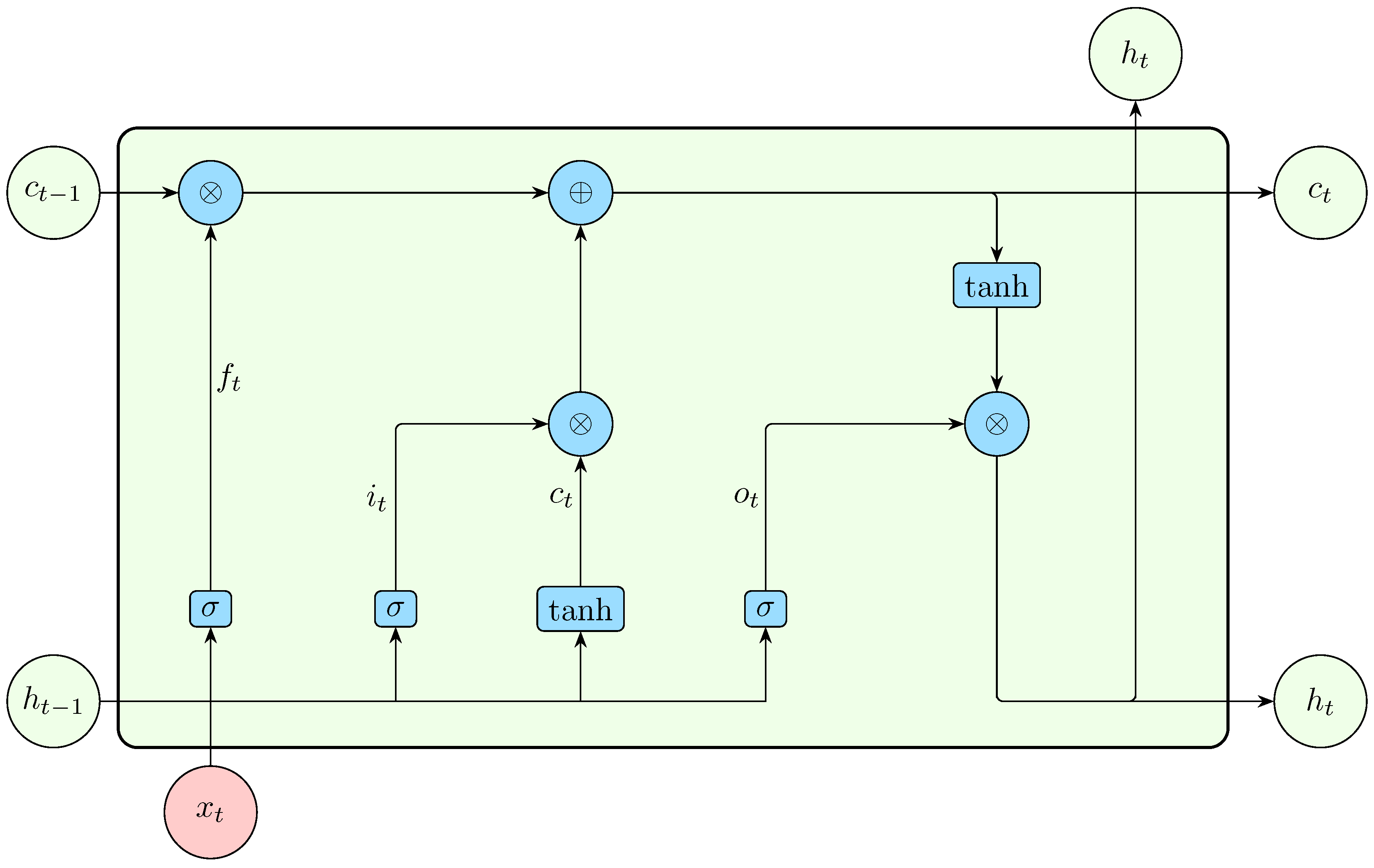

4.5. Long Short-Term Memory

4.6. Other LSTM Variants

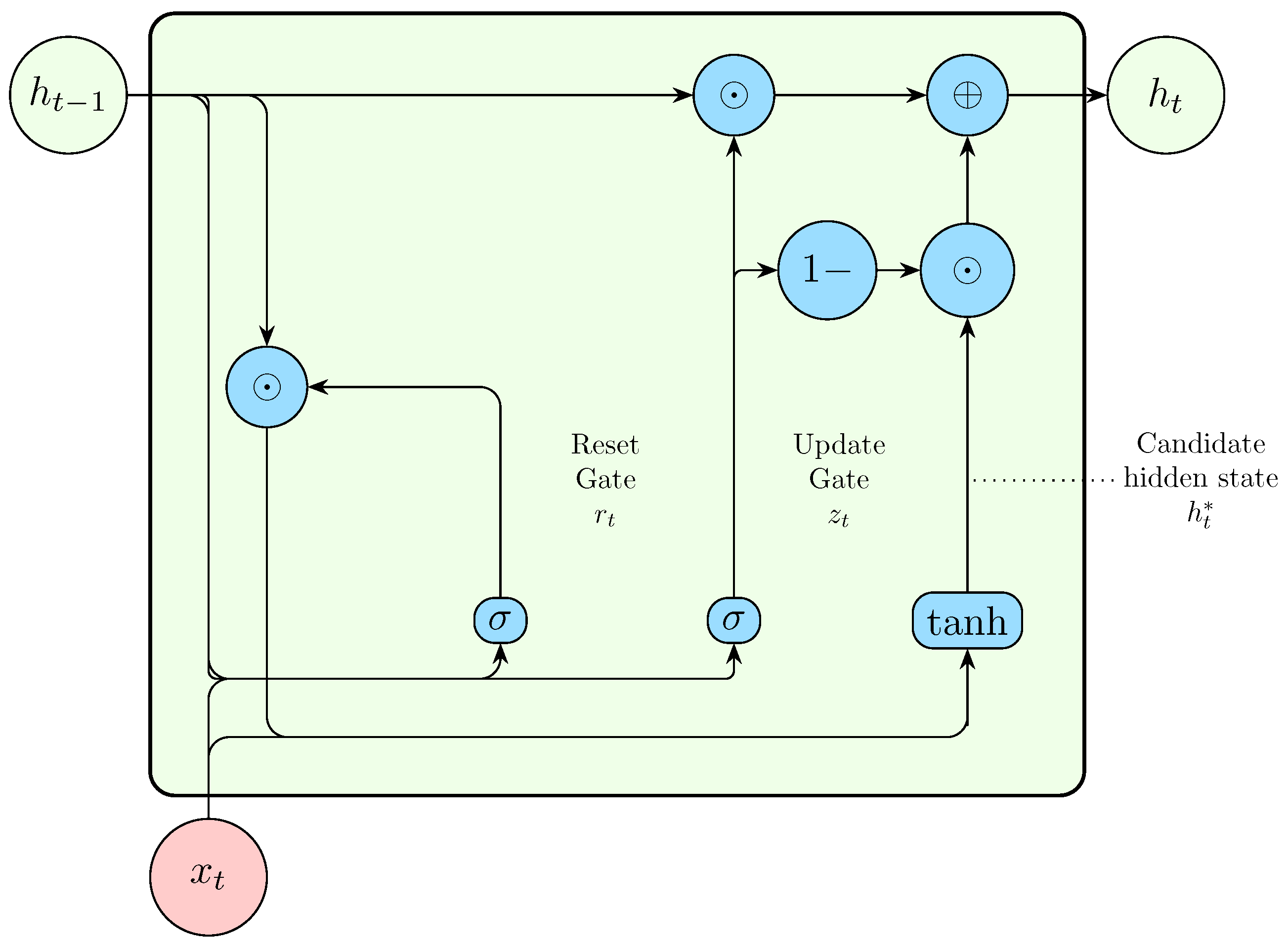

4.7. Gated Recurrent Unit

4.8. Comparison Between LSTM and GRU

4.9. Transformer Models

4.10. Mamba

4.11. Convolutional Neural Networks

4.11.1. 1D CNN

4.11.2. Causal CNN

4.12. Graph Neural Networks

4.12.1. Temporal Modeling in GNN

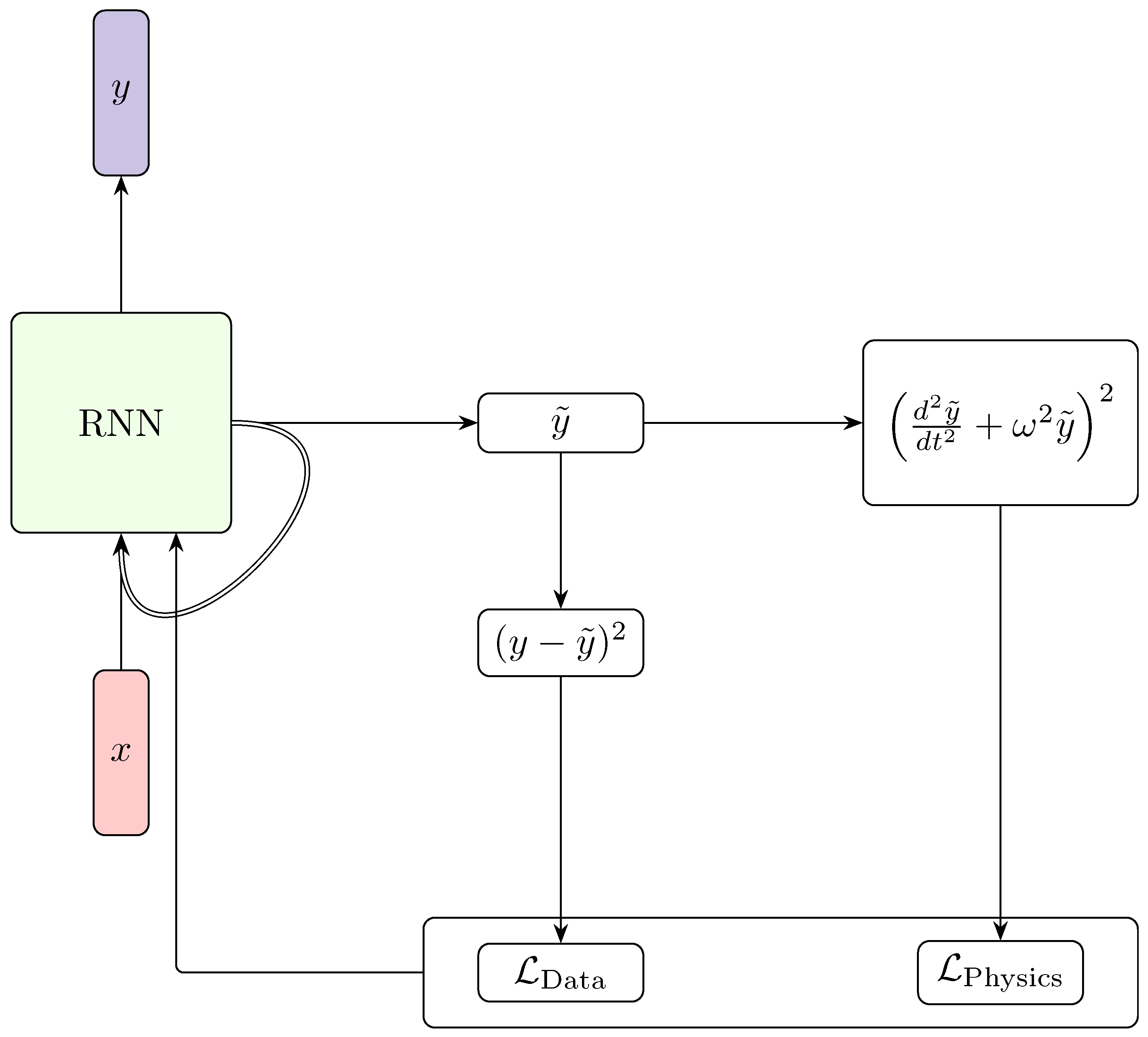

4.13. Physics-Informed Neural Networks

4.13.1. Issues with PINNs

5. Generative Modeling

5.1. Autoencoders

5.2. Variational Autoencoders

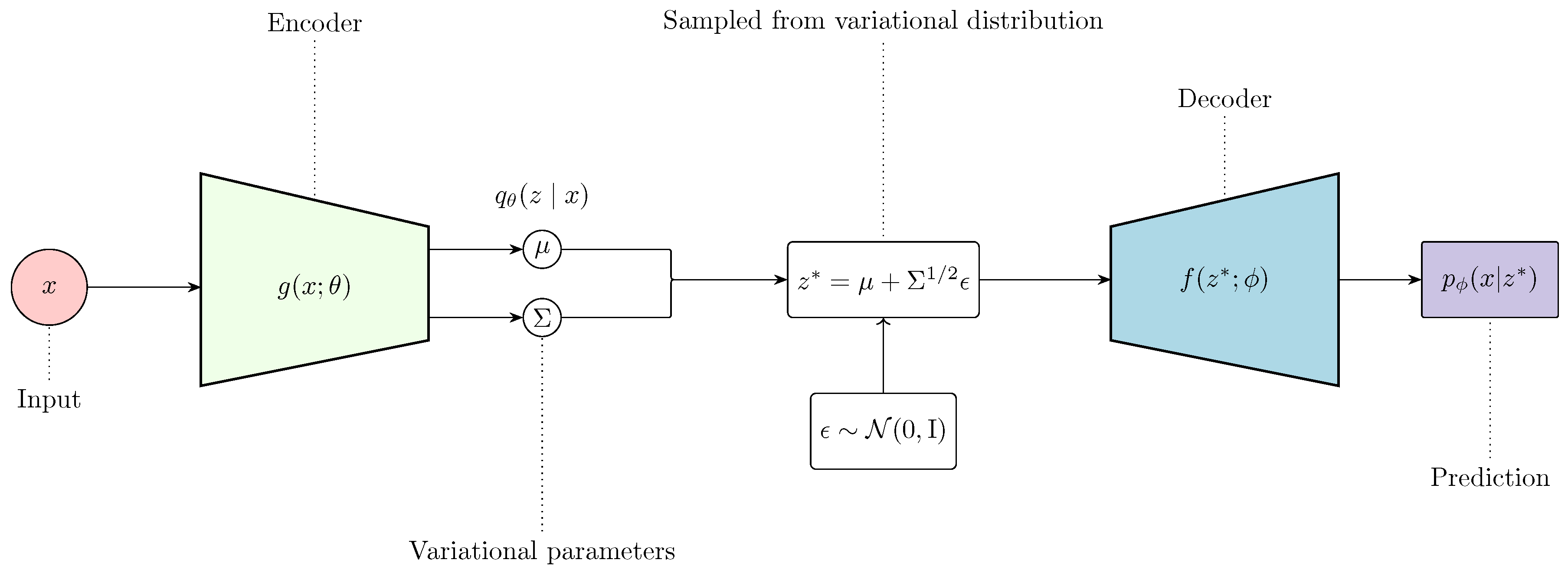

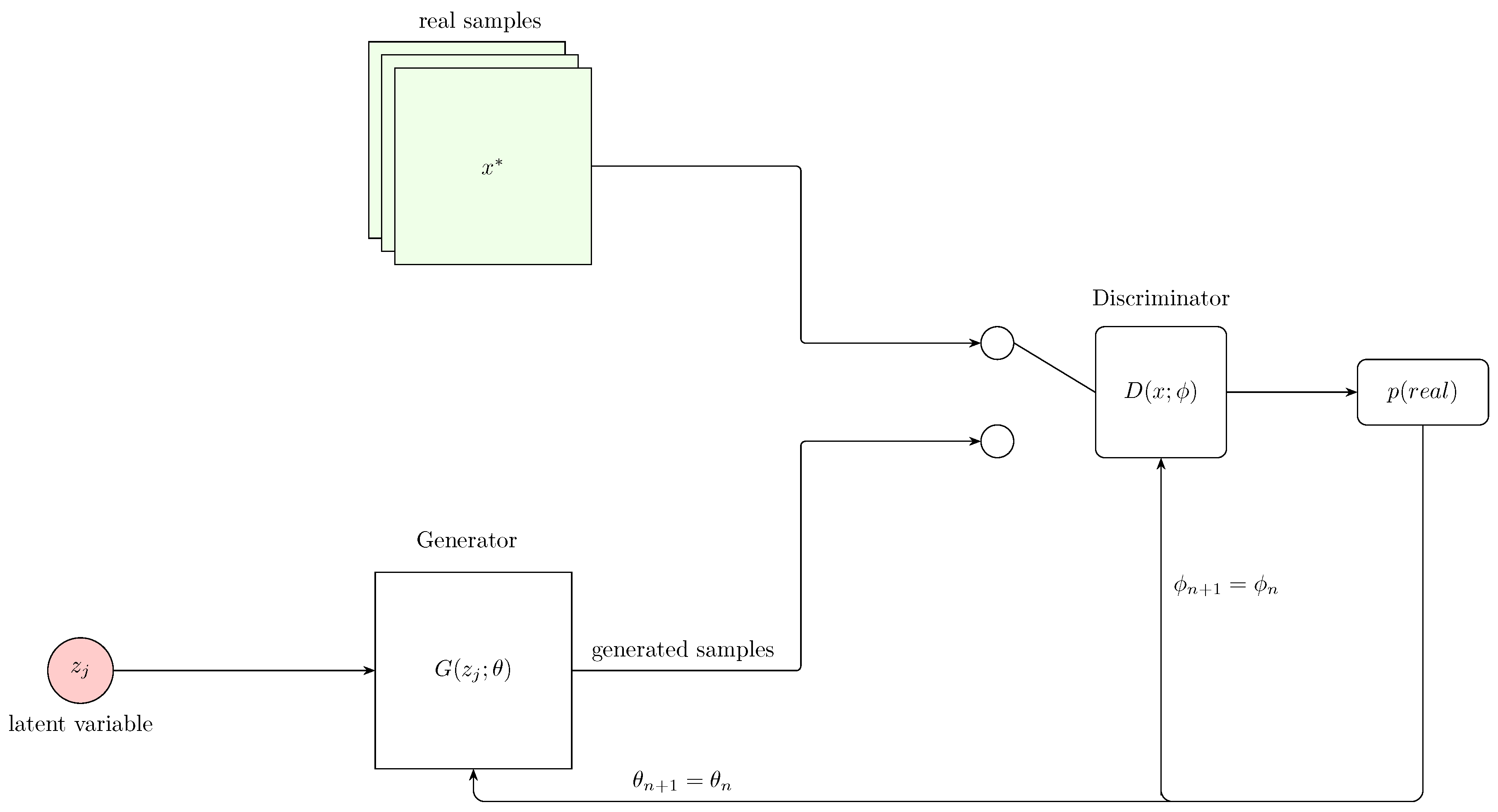

5.3. Generative Adversarial Network

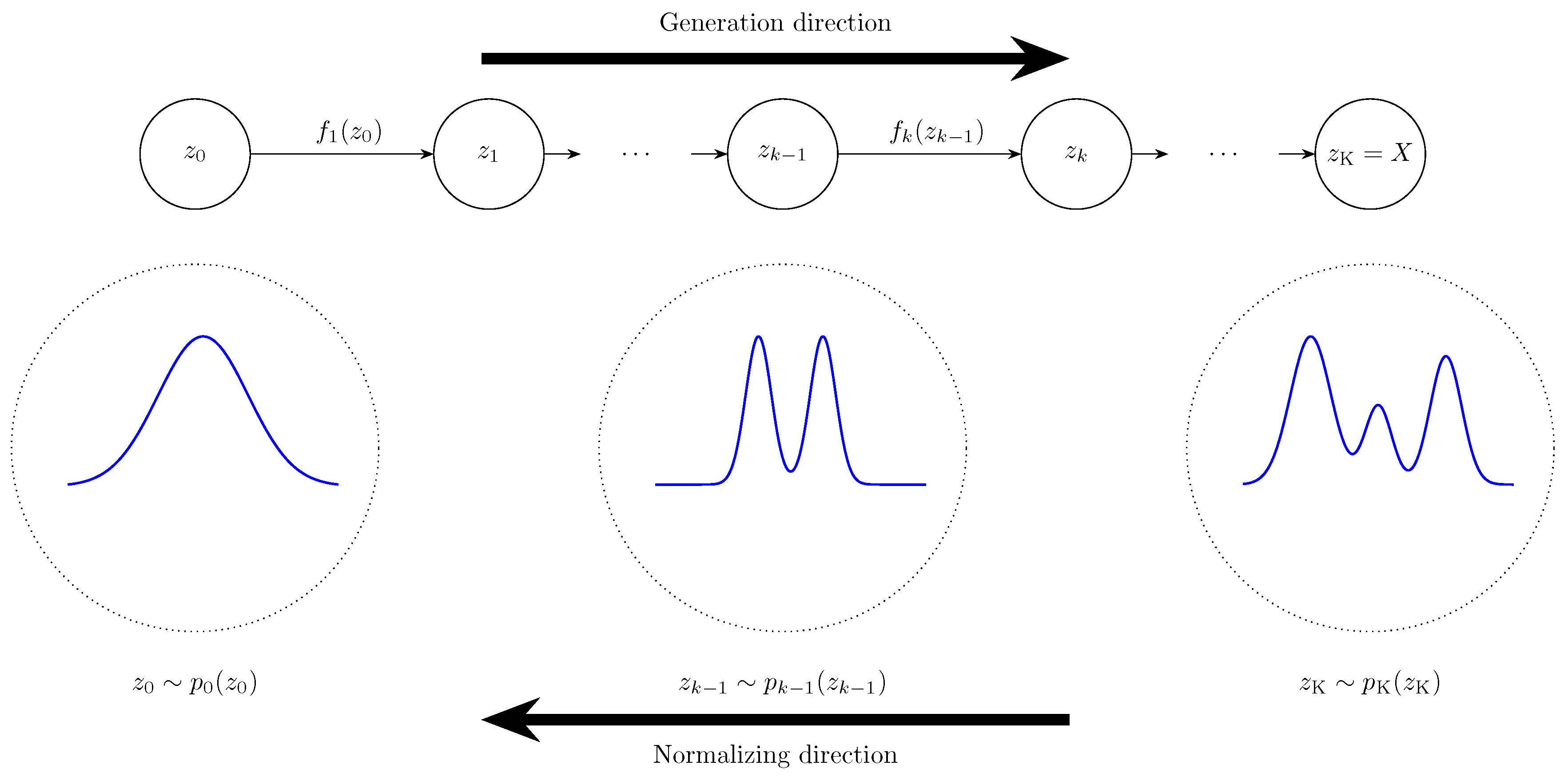

5.4. Normalizing Flows

5.5. Diffusion Models

5.6. Autoregressive Models

5.7. Energy-Based Models

5.8. Summary of Generative Models

6. Uncertainty Quantification

6.1. Bayesian Inference

6.1.1. Analytical Methods (Conjugacy)

6.1.2. Maximum Likelihood Estimation

6.1.3. Maximum A Posteriori (MAP)

6.1.4. Laplace Approximation

6.1.5. Expectation Maximization

6.1.6. Monte Carlo Integration

6.1.7. Importance Sampling

6.1.8. Variational Inference

6.1.9. Markov Chain Monte Carlo

Metropolis-Hastings Algorithm

Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC)

6.2. Bayesian Neural Networks

6.2.1. Overview

6.2.2. Tractable Approximate Gaussian Inference

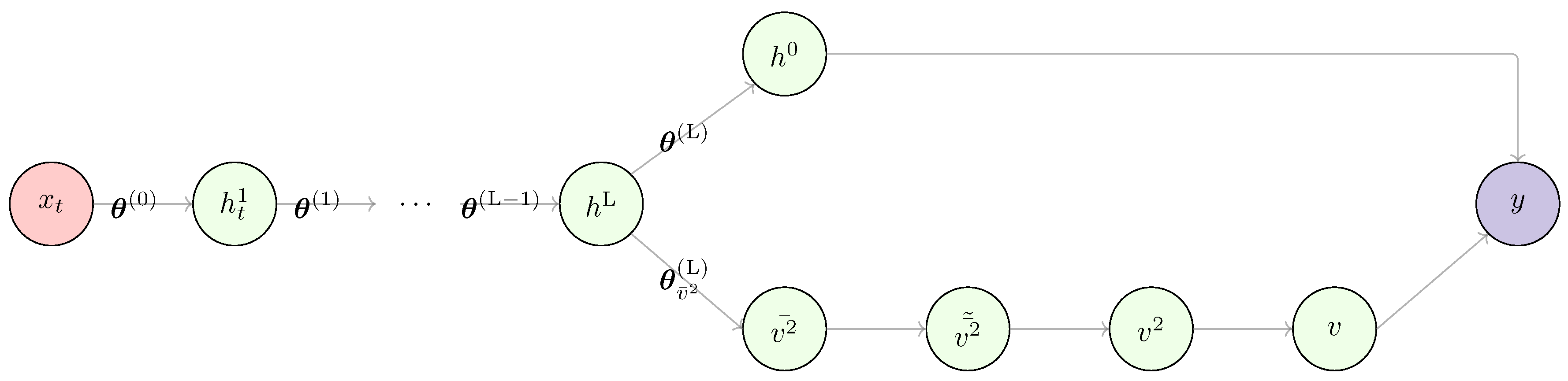

6.2.3. Learned Observation Noise in TAGI

6.2.4. Further TAGI Extensions

6.2.5. Monte Carlo Dropout

6.2.6. Bayes by Backpropagation

6.2.7. Probabilistic Backpropagation

7. Applications

7.1. Damage Assessment

7.2. Structural Response Prediction

7.3. Structural Load Prediction

7.4. Data Reconstruction

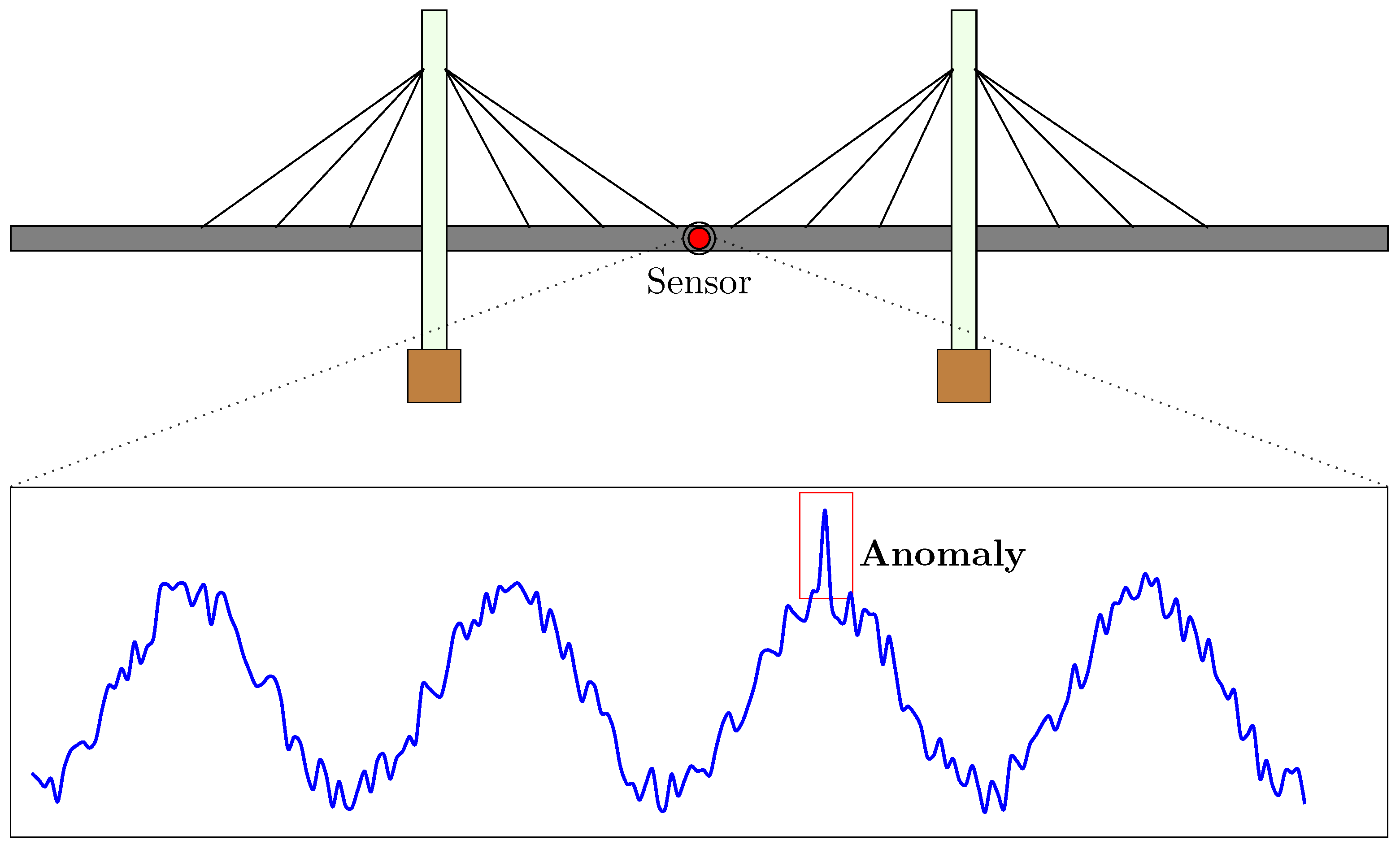

7.5. Anomaly Detection

| Application | Scope (Specific Papers) | Deep Learning Architectures Used |

|---|---|---|

| Damage Assessment | Damage detection: [300,301,302,303,304,305,306,307,308,309,310,311,312,313]Damage localization: [314,315,316,317,318,319,320]Damage classification: [321,322,323,324]Damage progression prediction: [325] | CNN, GRU, LSTM, BiLSTM, Autoencoder, Transformer, CNN-RNN hybrids |

| Structural Response Prediction | Strain prediction: [326,327]Displacement/Deflection: [328,329,330,331,332,333,334,335]Seismic and vibration: [336,337,338,339,340]Thermal-induced: [341]Tunnel responses: [342,343,344]Mechanical/Stress: [326,334,340,345,346,347]Cable tension: [348] | LSTM, BiLSTM, CNN, GRU, Attention, Transformer-based models |

| Structural Load Prediction | Dynamic load: [349,350] | CNN, Bayesian optimization, Autoencoder, CNN-BiLSTM hybrids |

| Data Reconstruction | Wind: [287,351,352,353]Vibration: [354,355,356]Temperature: [357]Dam monitoring: [358] | CNN, BiLSTM, GAN, Autoencoder, CNN-GRU hybrids, VMD, EMD |

| Anomaly Detection | Sensor faults: [359,360,361,362,363]Outliers: [363,364,365] | CNN, LSTM, BiLSTM, FCN, Transformer, PCA |

| Sensor Placement | Optimized placement: [336,349] | Attention-based RNN, CNN-BiLSTM |

| Data Augmentation/Generation | Synthetic data: [366] | GAN, CycleGAN, CNN, BiLSTM |

| Other SHM Tasks | Traffic classification: [367]Data compression: [368]Structural state ID: [369]Defect diagnosis: [370] | CNN, Autoencoder, Transformer, CNN-RNN hybrids |

8. State of Deep Times Series in Reviewed Literature

8.1. Models

8.2. Challenges

9. Conclusions

Abbreviations

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| AOA | Arithmetic Optimization Algorithm |

| ARIMA | AutoRegressive Integrated Moving Average |

| BIM | Building Information Modeling |

| BRT | Boosted Regression Trees |

| ELM | Extreme Learning Machine |

| ESMD | Extreme-point Symmetric Mode Decomposition |

| FEM | Finite Element Method |

| GC | Geological Conditions |

| gMLP | Gated Multilayer Perceptron |

| HTT | Hydrostatic-Temperature-Time |

| IFC | Industry Foundation Classes |

| LD | Linear Dichroism |

| MAF | Moving Average Filter |

| MLR | Multiple Linear Regression |

| NAR | Nonlinear Autoregressive |

| NARX | Nonlinear Autoregressive with Exogenous Inputs |

| N-BEATS | Neural Basis Expansion Analysis for Time Series Forecasting |

| N-HITS | Neural Hierarchical Interpolation for Time Series |

| ODE | Ordinary Differential Equation |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| PE | Permutation Entropy |

| RMSE | Root Mean Squared Error |

| SARIMA | Seasonal AutoRegressive Integrated Moving Average |

| SD | Sequence Decomposition |

| STL | Seasonal-Trend Decomposition using Loess |

| TSMixer | Time Series Mixer |

References

- Vivien Foster, Nisan Gorgulu, Stéphane Straub, and Maria Vagliasindi. The impact of infrastructure on development outcomes: A qualitative review of four decades of literature. Policy Research Working Paper 10343, World Bank, March 2023. URL http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/099529203062342252/pdf/IDU0e42ae32f0048304f74086d102b6d7a900223.pdf. © World Bank. Licensed under CC BY-NC 3.0 IGO.

- Kevin Wall. Some implications of the condition of south africa’s public sector fixed infrastructure. 31:224–256, Dec. 2024. URL https://journals.ufs.ac.za/index.php/as/article/view/8824. [CrossRef]

- Xolani Thusi and Victor H. Mlambo. The effects of africa’s infrastructure crisis and its root causes. International Journal of Environmental, Sustainability, and Social Science, 4(4):1055–1067, July 2023. URL https://journalkeberlanjutan.keberlanjutanstrategis.com/index.php/ijesss/article/view/671/646. [CrossRef]

- Francesc Pozo, Diego A. Tibaduiza, and Yolanda Vidal. Sensors for structural health monitoring and condition monitoring. Sensors, 21(5), 2021. ISSN 1424-8220. URL https://www.mdpi.com/1424-8220/21/5/1558. [CrossRef]

- David Blockley. Analysis of structural failures. Ice Proceedings, 62:51–74, 01 1977. [CrossRef]

- PSA. South africa’s water crisis and solutions, November 2024. URL https://www.psa.co.za/docs/default-source/psa-documents/psa-opinion/sa-water-crisis.pdf?sfvrsn=873d4a59_2. The Union of Choice.

- iNFRASTRUCTURE South Africa. Infrastructure development scenarios for south africa towards 2050, n.d. URL https://infrastructuresa.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Infrastructure-development-scenarios-for-south-Africa-2050_For-Print_20230705-Final-Document.pdf. Accessed: 14 May, 2025.

- MAKEUK. Infrastructure: Enabling growth by connecting people and places, n.d. URL https://www.makeuk.org/insights/reports/make-uk-latest-deep-dive-into-the-state-of-uk-infrastructure-is-out-now. Accessed: 14 May, 2025.

- G. Zini, M. Betti, and G. Bartoli. A pilot project for the long-term structural health monitoring of historic city gates. Journal of Civil Structural Health Monitoring, 12:537–556, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Mohamed Abdo. Structural Health Monitoring, History, Applications and Future. A Review Book. 01 2014. ISBN 978-1-941926-07-9.

- C. R. Farrar, N. Dervilis, and K. Worden. The past, present and future of structural health monitoring: An overview of three ages. Strain, 61(1):e12495, 2025. URL https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/str.12495. e12495 5547601. [CrossRef]

- Keith Worden, Charles Farrar, Graeme Manson, and Gyuhae Park. The fundamental axioms of structural health monitoring. Proceedings of The Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 463:1639–1664, 04 2007. [CrossRef]

- Unai Ugalde, Javier Anduaga, Oscar Salgado, and Aitzol Iturrospe. Shm method for locating damage with incomplete observations based on substructure’s connectivity analysis. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, 200:110519, 2023. ISSN 0888-3270. URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0888327023004272. [CrossRef]

- Ibomoiye Domor Mienye, Theo G. Swart, and George Obaido. Recurrent neural networks: A comprehensive review of architectures, variants, and applications. Information, 15(9), 2024. ISSN 2078-2489. URL https://www.mdpi.com/2078-2489/15/9/517. [CrossRef]

- Neil C Thompson, Kristjan Greenewald, Keeheon Lee, Gabriel F Manso, et al. The computational limits of deep learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2007.05558, 10, 2020.

- Yang, Luodongni. Research on the legal regulation of generative artificial intelligence—— take chatgpt as an example. SHS Web of Conf., 178:02017, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Billie F. Spencer, Sung-Han Sim, Robin E. Kim, and Hyungchul Yoon. Advances in artificial intelligence for structural health monitoring: A comprehensive review. KSCE Journal of Civil Engineering, 29(3):100203, 2025. ISSN 1226-7988. URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1226798825003186. [CrossRef]

- Fuh-Gwo Yuan, Sakib Zargar, Qiuyi Chen, and Shaohan Wang. Machine learning for structural health monitoring: challenges and opportunities. page 2, 04 2020. [CrossRef]

- Jing Jia and Ying Li. Deep learning for structural health monitoring: Data, algorithms, applications, challenges, and trends. Sensors, 23(21), 2023. ISSN 1424-8220. URL https://www.mdpi.com/1424-8220/23/21/8824. [CrossRef]

- Aref Afshar, Gholamreza Nouri, Shahin Ghazvineh, and Seyed Hossein Hosseini Lavassani. Machine-learning applications in structural response prediction: A review. Practice Periodical on Structural Design and Construction, 29(3):03124002, 2024. URL https://ascelibrary.org/doi/abs/10.1061/PPSCFX.SCENG-1292. [CrossRef]

- Gyungmin Toh and Junhong Park. Review of vibration-based structural health monitoring using deep learning. Applied Sciences, 10:1680, 03 2020. [CrossRef]

- Mohsen Azimi, Armin Dadras, and Gokhan Pekcan. Data-driven structural health monitoring and damage detection through deep learning: State-of-the-art review. Sensors, 20, 05 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Indhu, G. Sundar, and H. Parveen. A review of machine learning algorithms for vibration-based shm and vision-based shm. pages 418–422, 02 2022. [CrossRef]

- Hao Wang, Baoli Wang, and Caixia Cui. Deep learning methods for vibration-based structural health monitoring: A review. Iranian Journal of Science and Technology, Transactions of Civil Engineering, 48, 12 2023a. [CrossRef]

- Onur Avci, Osama Abdeljaber, Serkan Kiranyaz, Mohammed Hussein, Moncef Gabbouj, and Daniel J. Inman. A review of vibration-based damage detection in civil structures: From traditional methods to machine learning and deep learning applications. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, 147:107077, 2021. ISSN 0888-3270. URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0888327020304635. [CrossRef]

- Younes Hamishebahar, Hong Guan, Stephen So, and Jun Jo. A comprehensive review of deep learning-based crack detection approaches. Applied Sciences, 2022. URL https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:246408379.

- Ayesha Chowdhury and Rashed Kaiser. A comprehensive analysis of the integration of deep learning models in concrete research from a structural health perspective. Construction Materials, 4:72–90, 01 2024. [CrossRef]

- Alain Gomez-Cabrera and Ponciano Jorge Escamilla-Ambrosio. Review of machine-learning techniques applied to structural health monitoring systems for building and bridge structures. Applied Sciences, 12(21), 2022. ISSN 2076-3417. URL https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/12/21/10754. [CrossRef]

- Sandeep Sony, Kyle Dunphy, Ayan Sadhu, and Miriam Capretz. A systematic review of convolutional neural network-based structural condition assessment techniques. Engineering Structures, 226:111347, 01 2021. [CrossRef]

- Jianghua Deng, Amardeep Multani, Yiyi Zhou, Ye Lu, and Vincent Lee. Review on computer vision-based crack detection and quantification methodologies for civil structures. Construction and Building Materials, 356:129238, 11 2022. [CrossRef]

- Samir Khan, Takehisa Yairi, Seiji Tsutsumi, and Shinichi Nakasuka. A review of physics-based learning for system health management. Annual Reviews in Control, 57:100932, 2024a. ISSN 1367-5788. URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1367578824000014. [CrossRef]

- Jianwei Zhang, Minshui Huang, Neng Wan, Zhihang Deng, Zhongao He, and Jin Luo. Missing measurement data recovery methods in structural health monitoring: The state, challenges and case study. Measurement, 231:114528, 03 2024a. [CrossRef]

- Furkan Luleci and F. Necati Catbas. A brief introductory review to deep generative models for civil structural health monitoring. AI in Civil Engineering, 2(1):9, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Furkan Luleci, F. Necati Catbas, and Onur Avci. A literature review: Generative adversarial networks for civil structural health monitoring. Frontiers in Built Environment, 8:1027379, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Young-Jin Cha, Rahmat Ali, John Lewis, and Oral Büyüköztürk. Deep learning-based structural health monitoring. Automation in Construction, 161:105328, 2024. ISSN 0926-5805. URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0926580524000645. [CrossRef]

- Mohammad Ali Abedi, Javad Shayanfar, and Khalifa Al-Jabri. Infrastructure damage assessment via machine learning approaches: a systematic review. Asian Journal of Civil Engineering, 24:3823–3852, 2023. URL https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:259543609.

- Guo-Qing Zhang, Bin Wang, Jun Li, and You-Lin Xu. The application of deep learning in bridge health monitoring: a literature review. Advances in Bridge Engineering, 3, 12 2022a. [CrossRef]

- Amin T. G. Tapeh and M. Z. Naser. Artificial intelligence, machine learning, and deep learning in structural engineering: A scientometrics review of trends and best practices. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering, 30:115–159, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Donghui Xu, Xiang Xu, Michael C. Forde, and Antonio Caballero. Concrete and steel bridge structural health monitoring—insight into choices for machine learning applications. Construction and Building Materials, 402:132596, 2023a. ISSN 0950-0618. URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0950061823023127. [CrossRef]

- Sam Bond-Taylor, Adam Leach, Yang Long, and Chris G Willcocks. Deep generative modelling: A comparative review of vaes, gans, normalizing flows, energy-based and autoregressive models. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence, 44(11):7327–7347, 2021.

- John A Miller, Mohammed Aldosari, Farah Saeed, Nasid Habib Barna, Subas Rana, I Budak Arpinar, and Ninghao Liu. A survey of deep learning and foundation models for time series forecasting. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.13912, 2024.

- Yuxuan Wang, Haixu Wu, Jiaxiang Dong, Yong Liu, Mingsheng Long, and Jianmin Wang. Deep time series models: A comprehensive survey and benchmark. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.13278, 2024a.

- Pedro Lara-Benítez, Manuel Carranza-García, and José C Riquelme. An experimental review on deep learning architectures for time series forecasting. International journal of neural systems, 31(03):2130001, 2021.

- Moloud Abdar, Farhad Pourpanah, Sadiq Hussain, Dana Rezazadegan, Li Liu, Mohammad Ghavamzadeh, Paul Fieguth, Xiaochun Cao, Abbas Khosravi, U Rajendra Acharya, et al. A review of uncertainty quantification in deep learning: Techniques, applications and challenges. Information fusion, 76:243–297, 2021.

- Jakob Gawlikowski, Carlo R. N. Tassi, Murtaza Ali, Jonghun Lee, Marcel Humt, Jin Feng, Anna Kruspe, Rudolph Triebel, Peter Jung, Ribana Roscher, et al. A survey of uncertainty in deep neural networks. Artificial Intelligence Review, 56(Suppl 1):1513–1589, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Piotr Omenzetter and James Mark William Brownjohn. Application of time series analysis for bridge monitoring. Smart Materials and Structures, 15(1):129, jan 2006. URL https://dx.doi.org/10.1088/0964-1726/15/1/041. [CrossRef]

- D. Inaudi. 11 - structural health monitoring of bridges: general issues and applications. In Vistasp M. Karbhari and Farhad Ansari, editors, Structural Health Monitoring of Civil Infrastructure Systems, Woodhead Publishing Series in Civil and Structural Engineering, pages 339–370. Woodhead Publishing, 2009. ISBN 978-1-84569-392-3. URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9781845693923500116. [CrossRef]

- Navid Mohammadi Foumani, Lynn Miller, Chang Wei Tan, Geoffrey I Webb, Germain Forestier, and Mahsa Salehi. Deep learning for time series classification and extrinsic regression: A current survey. ACM Computing Surveys, 56(9):1–45, 2024.

- F. Mojtahedi, N. Yousefpour, S. Chow, and M. Cassidy. Deep learning for time series forecasting: Review and applications in geotechnics and geosciences. Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering, 02 2025. [CrossRef]

- Zahra Zamanzadeh Darban, Geoffrey I Webb, Shirui Pan, Charu Aggarwal, and Mahsa Salehi. Deep learning for time series anomaly detection: A survey. ACM Computing Surveys, 57(1):1–42, 2024.

- Paul Boniol, Qinghua Liu, Mingyi Huang, Themis Palpanas, and John Paparrizos. Dive into time-series anomaly detection: A decade review. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.20512, 2024.

- Chenguang Fang and Chen Wang. Time series data imputation: A survey on deep learning approaches. arXiv preprint arXiv:2011.11347, 2020.

- Pankaj Das and Samir Barman. An Overview of Time Series Decomposition and Its Applications, pages 1–15. 02 2025. [CrossRef]

- Zhengnan Li, Yunxiao Qin, Xilong Cheng, and Yuting Tan. Ftmixer: Frequency and time domain representations fusion for time series modeling. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.15256, 2024a.

- R.H. Shumway and D.S. Stoffer. Time Series Analysis and Its Applications: With R Examples. Springer Texts in Statistics. Springer International Publishing, 2017. ISBN 9783319524528. URL https://books.google.mw/books?id=sfFdDwAAQBAJ.

- Vishwanathan Iyer and Kaushik Roy Chowdhury. Spectral analysis: Time series analysis in frequency domain. The IUP Journal of Applied Economics, VIII:83–101, 01 2009.

- Alexandr Volvach, Galina Kurbasova, and Larisa Volvach. Wavelets in the analysis of local time series of the earth’s surface air. Heliyon, 10(1):e23237, 2024. ISSN 2405-8440. URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2405844023104452. [CrossRef]

- Warren S. McCulloch and Walter Pitts. A logical calculus of the ideas immanent in nervous activity. Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics, 5:115–133, 1943. [CrossRef]

- Frank Rosenblatt. The perceptron: a probabilistic model for information storage and organization in the brain. Psychological review, 65 6:386–408, 1958. URL https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:12781225.

- Paul J. Werbos. Beyond Regression: New Tools for Prediction and Analysis in the Behavioral Sciences. PhD thesis, Harvard University, 1974.

- Kunihiko Fukushima. Neocognitron: A self-organizing neural network model for a mechanism of pattern recognition unaffected by shift in position. Biological Cybernetics, 36:193–202, 1980. [CrossRef]

- John Hopfield. Neural networks and physical systems with emergent collective computational abilities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 79:2554–8, 05 1982. [CrossRef]

- David E. Rumelhart, Geoffrey E. Hinton, and Ronald J. Williams. Learning representations by back-propagating errors. Nature, 323:533–536, 1986. URL https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:205001834.

- Y. LeCun, B. Boser, J. S. Denker, D. Henderson, R. E. Howard, W. Hubbard, and L. D. Jackel. Backpropagation applied to handwritten zip code recognition. Neural Computation, 1(4):541–551, 1989. [CrossRef]

- Sepp Hochreiter and Jürgen Schmidhuber. Long short-term memory. Neural computation, 9(8):1735–1780, 1997.

- Yoshua Bengio, Réjean Ducharme, Pascal Vincent, and Christian Jauvin. A neural probabilistic language model. Journal of machine learning research, (Feb):1137–1155, 2003.

- Geoffrey Hinton, Simon Osindero, and Yee-Whye Teh. A fast learning algorithm for deep belief nets. Neural Computation, 18:1527–1554, 07 2006. [CrossRef]

- Xavier Glorot and Yoshua Bengio. Understanding the difficulty of training deep feedforward neural networks. In Proceedings of the thirteenth international conference on artificial intelligence and statistics, pages 249–256. JMLR Workshop and Conference Proceedings, 2010.

- Alex Krizhevsky, Ilya Sutskever, and Geoffrey E. Hinton. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Communications of the ACM, 60:84 – 90, 2012. URL https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:195908774.

- Ian Goodfellow, Yoshua Bengio, and Aaron Courville. Deep Learning. MIT Press, 2016. http://www.deeplearningbook.org.

- Laith Alzubaidi, Jinglan Zhang, Amjad J Humaidi, Ayad Al-Dujaili, Ye Duan, Omran Al-Shamma, José Santamaría, Mohammed A Fadhel, Muthana Al-Amidie, and Laith Farhan. Review of deep learning: concepts, cnn architectures, challenges, applications, future directions. Journal of big Data, 8:1–74, 2021.

- Iqbal H Sarker. Deep learning: a comprehensive overview on techniques, taxonomy, applications and research directions. SN computer science, 2(6):420, 2021.

- George Cybenko. Approximation by superpositions of a sigmoidal function. Mathematics of Control, Signals and Systems, 2(4):303–314, 1989.

- Kurt Hornik, Maxwell Stinchcombe, and Halbert White. Multilayer feedforward networks are universal approximators. Neural Networks, 2(5):359–366, 1989. ISSN 0893-6080. URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/0893608089900208. [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standardization and International Electrotechnical Commission. ISO/IEC 22989:2022 - Information technology — Artificial intelligence — Artificial intelligence concepts and terminology, 2022. Edition 1.

- Johannes Lederer. Activation functions in artificial neural networks: A systematic overview. arXiv preprint arXiv:2101.09957, 2021.

- Xavier Glorot, Antoine Bordes, and Y. Bengio. Deep sparse rectifier neural networks. In Proceedings of the Fourteenth International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (AISTATS), volume 15 of Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pages 315–323. PMLR, 2011.

- Vladimír Kunc and Jiří Kléma. Three decades of activations: A comprehensive survey of 400 activation functions for neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.09092, 2024.

- Shiv Ram Dubey, Satish Kumar Singh, and Bidyut Baran Chaudhuri. Activation functions in deep learning: A comprehensive survey and benchmark. Neurocomputing, 503:92–108, 2022.

- Sajid A. Marhon, Christopher J. F. Cameron, and Stefan C. Kremer. Recurrent Neural Networks, pages 29–65. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2013. ISBN 978-3-642-36657-4.

- Guoping Xu, Xiaxia Wang, Xinglong Wu, Xuesong Leng, and Yongchao Xu. Development of skip connection in deep neural networks for computer vision and medical image analysis: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.01725, 2024a.

- Shiyu Liang and Rayadurgam Srikant. Why deep neural networks for function approximation? arXiv preprint arXiv:1610.04161, 2016.

- J.-A. Goulet. Probabilistic Machine Learning for Civil Engineers. MIT Press, 2020.

- Simon J.D. Prince. Understanding Deep Learning. The MIT Press, 2023. URL http://udlbook.com.

- Christopher M. Bishop and Hugh Bishop. Deep Learning: Foundations and Concepts. Springer, 2023. ISBN 978-3-031-45468-4. URL https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-031-45468-4. [CrossRef]

- Zari Farhadi, Hossein Bevrani, and Mohammad Reza Feizi Derakhshi. Combining regularization and dropout techniques for deep convolutional neural network. pages 335–339, 10 2022. [CrossRef]

- T Hastie. The elements of statistical learning: Data mining, inference, and prediction, 2009.

- Lutz Prechelt. Early Stopping — But When?, pages 53–67. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2012. ISBN 978-3-642-35289-8.

- Sergey Ioffe and Christian Szegedy. Batch normalization: Accelerating deep network training by reducing internal covariate shift. In International conference on machine learning, pages 448–456. pmlr, 2015.

- Hongyi Zhang, Moustapha Cisse, Yann N Dauphin, and David Lopez-Paz. mixup: Beyond empirical risk minimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1710.09412, 2017.

- Kaiming He, Xiangyu Zhang, Shaoqing Ren, and Jian Sun. Delving deep into rectifiers: Surpassing human-level performance on imagenet classification. In Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, pages 1026–1034, 2015.

- Yann Lecun, Leon Bottou, Genevieve Orr, and Klaus-Robert Müller. Efficient backprop. 08 2000.

- Wei Hu, Lechao Xiao, and Jeffrey Pennington. Provable benefit of orthogonal initialization in optimizing deep linear networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2001.05992, 2020.

- Andrew M Saxe, James L McClelland, and Surya Ganguli. Exact solutions to the nonlinear dynamics of learning in deep linear neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1312.6120, 2013.

- Marc Peter Deisenroth, A Aldo Faisal, and Cheng Soon Ong. Mathematics for machine learning. Cambridge University Press, 2020.

- A. Rosebrock. Deep Learning for Computer Vision with Python: Starter Bundle. PyImageSearch, 2017. URL https://books.google.mw/books?id=9Ul-tgEACAAJ.

- John Duchi, Elad Hazan, and Yoram Singer. Adaptive subgradient methods for online learning and stochastic optimization. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 12(61):2121–2159, 2011. URL http://jmlr.org/papers/v12/duchi11a.html.

- Geoffrey Hinton, Nitish Srivastava, Kevin Swersky, and Timothy Tieleman. Neural networks for machine learning, lecture 6e: Rmsprop: Divide the gradient by a running average of its recent magnitude. https://www.cs.toronto.edu/~tijmen/csc321/slides/lecture_slides_lec6.pdf, 2012. Lecture slides.

- Diederik P Kingma and Jimmy Ba. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1412.6980, 2014.

- Bhargob Deka, Luong Ha Nguyen, and James-A. Goulet. Analytically tractable heteroscedastic uncertainty quantification in bayesian neural networks for regression tasks. Neurocomputing, 572:127183, 2024a. ISSN 0925-2312. URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0925231223013061. [CrossRef]

- Ankit Belwal, S. Senthilkumar, Intekhab Alam, and Feon Jaison. Exploring multi-layer perceptrons for time series classification in networks. In Amit Kumar, Vinit Kumar Gunjan, Sabrina Senatore, and Yu-Chen Hu, editors, Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Data Science, Machine Learning and Applications; Volume 2, pages 663–668, Singapore, 2025. Springer Nature Singapore. ISBN 978-981-97-8043-3.

- Zhiguang Wang, Weizhong Yan, and Tim Oates. Time series classification from scratch with deep neural networks: A strong baseline. In 2017 International joint conference on neural networks (IJCNN), pages 1578–1585. IEEE, 2017.

- Ana Lazcano, Miguel A. Jaramillo-Morán, and Julio E. Sandubete. Back to basics: The power of the multilayer perceptron in financial time series forecasting. Mathematics, 12(12), 2024. ISSN 2227-7390. URL https://www.mdpi.com/2227-7390/12/12/1920. [CrossRef]

- Yihong Dong, Ge Li, Yongding Tao, Xue Jiang, Kechi Zhang, Jia Li, Jinliang Deng, Jing Su, Jun Zhang, and Jingjing Xu. Fan: Fourier analysis networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.02675, 2024.

- Boris N Oreshkin, Dmitri Carpov, Nicolas Chapados, and Yoshua Bengio. N-beats: Neural basis expansion analysis for interpretable time series forecasting. arXiv preprint arXiv:1905.10437, 2019.

- Cristian Challu, Kin G Olivares, Boris N Oreshkin, Federico Garza Ramirez, Max Mergenthaler Canseco, and Artur Dubrawski. Nhits: Neural hierarchical interpolation for time series forecasting. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, volume 37, pages 6989–6997, 2023.

- Si-An Chen, Chun-Liang Li, Nate Yoder, Sercan O Arik, and Tomas Pfister. Tsmixer: An all-mlp architecture for time series forecasting. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.06053, 2023a.

- Hanxiao Liu, Zihang Dai, David So, and Quoc V Le. Pay attention to mlps. Advances in neural information processing systems, 34:9204–9215, 2021.

- Michael M Bronstein, Joan Bruna, Taco Cohen, and Petar Veličković. Geometric deep learning: Grids, groups, graphs, geodesics, and gauges. arXiv preprint arXiv:2104.13478, 2021.

- Van-Dai Vuong. Analytically Tractable Bayesian Recurrent Neural Networks with Structural Health Monitoring Applications. Ph.d. thesis, Polytechnique Montréal, Département de génie civil, géologique et des mines, March 2024. URL https://publications.polymtl.ca/57728/. Thèse présentée en vue de l’obtention du diplôme de Philosophiæ Doctor en génie civil.

- Mike Schuster and Kuldip Paliwal. Bidirectional recurrent neural networks. Signal Processing, IEEE Transactions on, 45:2673 – 2681, 12 1997. [CrossRef]

- Y. Bengio, P. Simard, and P. Frasconi. Learning long-term dependencies with gradient descent is difficult. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks, 5(2):157–166, 1994. [CrossRef]

- Simone Scardapane. Alice’s adventures in a differentiable wonderland–volume i, a tour of the land. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.17625, 2024.

- Aston Zhang, Zachary C Lipton, Mu Li, and Alexander J Smola. Dive into deep learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.11342, 2021a.

- Felix A. Gers, Nicol N. Schraudolph, and Jürgen Schmidhuber. Learning precise timing with lstm recurrent networks. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 3:115–143, 2002. URL http://jmlr.csail.mit.edu/papers/volume3/gers02a/gers02a.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Maximilian Beck, Korbinian Pöppel, Markus Spanring, Andreas Auer, Oleksandra Prudnikova, Michael Kopp, Günter Klambauer, Johannes Brandstetter, and Sepp Hochreiter. xlstm: Extended long short-term memory. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.04517, 2024.

- Kyunghyun Cho, Bart Van Merriënboer, Caglar Gulcehre, Dzmitry Bahdanau, Fethi Bougares, Holger Schwenk, and Yoshua Bengio. Learning phrase representations using rnn encoder-decoder for statistical machine translation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1406.1078, 2014.

- Ashish Vaswani, Noam Shazeer, Niki Parmar, Jakob Uszkoreit, Llion Jones, Aidan N Gomez, ukasz Kaiser, and Illia Polosukhin. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems, 30, 2017.

- Bryan Lim, Sercan Ö Arık, Nicolas Loeff, and Tomas Pfister. Temporal fusion transformers for interpretable multi-horizon time series forecasting. International Journal of Forecasting, 37(4):1748–1764, 2021.

- Haoyi Zhou, Shanghang Zhang, Jieqi Peng, Shuai Zhang, Jianxin Li, Hui Xiong, and Wancai Zhang. Informer: Beyond efficient transformer for long sequence time-series forecasting. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, volume 35, pages 11106–11115, 2021.

- Haixu Wu, Jiehui Xu, Jianmin Wang, and Mingsheng Long. Autoformer: Decomposition transformers with auto-correlation for long-term series forecasting. Advances in neural information processing systems, 34:22419–22430, 2021.

- Tian Zhou, Ziqing Ma, Qingsong Wen, Xue Wang, Liang Sun, and Rong Jin. Fedformer: Frequency enhanced decomposed transformer for long-term series forecasting. In International conference on machine learning, pages 27268–27286. PMLR, 2022.

- Yuqi Nie, Nam H Nguyen, Phanwadee Sinthong, and Jayant Kalagnanam. A time series is worth 64 words: Long-term forecasting with transformers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.14730, 2022.

- Albert Gu and Tri Dao. Mamba: Linear-time sequence modeling with selective state spaces. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.00752, 2023.

- Albert Gu, Tri Dao, Stefano Ermon, Atri Rudra, and Christopher Ré. Hippo: Recurrent memory with optimal polynomial projections. Advances in neural information processing systems, 33:1474–1487, 2020.

- Ian Goodfellow, Jean Pouget-Abadie, Mehdi Mirza, Bing Xu, David Warde-Farley, Sherjil Ozair, Aaron Courville, and Yoshua Bengio. Generative adversarial nets. Advances in neural information processing systems, 27, 2014.

- Serkan Kiranyaz, Onur Avci, Osama Abdeljaber, Turker Ince, Moncef Gabbouj, and Daniel J. Inman. 1d convolutional neural networks and applications: A survey. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, 151:107398, 2021. ISSN 0888-3270. URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0888327020307846. [CrossRef]

- Fisher Yu and Vladlen Koltun. Multi-scale context aggregation by dilated convolutions. arXiv preprint arXiv:1511.07122, 2015.

- Yuhang Zhang, Yaoqun Xu, and Yu Zhang. A graph neural network node classification application model with enhanced node association. Applied Sciences, 13(12), 2023. ISSN 2076-3417. URL https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/13/12/7150. [CrossRef]

- Muhan Zhang and Yixin Chen. Link prediction based on graph neural networks. Advances in neural information processing systems, 31, 2018.

- Xingyu Liu, Juan Chen, and Quan Wen. A survey on graph classification and link prediction based on gnn. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.00865, 2023.

- Renjie Liao, Yujia Li, Yang Song, Shenlong Wang, Will Hamilton, David K Duvenaud, Raquel Urtasun, and Richard Zemel. Efficient graph generation with graph recurrent attention networks. Advances in neural information processing systems, 32, 2019.

- William L. Hamilton. Graph representation learning. Synthesis Lectures on Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning, 14(3):1–159, 2020.

- T Konstantin Rusch, Michael M Bronstein, and Siddhartha Mishra. A survey on oversmoothing in graph neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.10993, 2023.

- Ling Zhao, Yujiao Song, Chao Zhang, Yu Liu, Pu Wang, Tao Lin, Min Deng, and Haifeng Li. T-gcn: A temporal graph convolutional network for traffic prediction. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, 21(9):3848–3858, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Yuebing Liang, Zhan Zhao, and Lijun Sun. Memory-augmented dynamic graph convolution networks for traffic data imputation with diverse missing patterns. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 143:103826, 10 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ming Jin, Huan Yee Koh, Qingsong Wen, Daniele Zambon, Cesare Alippi, Geoffrey I Webb, Irwin King, and Shirui Pan. A survey on graph neural networks for time series: Forecasting, classification, imputation, and anomaly detection. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 2024.

- Zhongkai Hao, Songming Liu, Yichi Zhang, Chengyang Ying, Yao Feng, Hang Su, and Jun Zhu. Physics-informed machine learning: A survey on problems, methods and applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.08064, 2022.

- Maziar Raissi, Paris Perdikaris, and George E Karniadakis. Physics-informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. Journal of Computational physics, 378:686–707, 2019.

- Aditi Krishnapriyan, Amir Gholami, Shandian Zhe, Robert Kirby, and Michael W Mahoney. Characterizing possible failure modes in physics-informed neural networks. Advances in neural information processing systems, 34:26548–26560, 2021.

- Nathan Doumèche, Gérard Biau, and Claire Boyer. Convergence and error analysis of pinns. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.01240, 2023.

- K. Sel, A. Mohammadi, R. I. Pettigrew, et al. Physics-informed neural networks for modeling physiological time series for cuffless blood pressure estimation. npj Digital Medicine, 6:110, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Keon Vin Park, Jisu Kim, and Jaemin Seo. Pint: Physics-informed neural time series models with applications to long-term inference on weatherbench 2m-temperature data. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.04018, 2025.

- Sifan Wang, Yujun Teng, and Paris Perdikaris. Understanding and mitigating gradient flow pathologies in physics-informed neural networks. SIAM Journal on Scientific Computing, 43(5):A3055–A3081, 2021.

- Jassem Abbasi, Ameya D Jagtap, Ben Moseley, Aksel Hiorth, and Pål stebø Andersen. Challenges and advancements in modeling shock fronts with physics-informed neural networks: A review and benchmarking study. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.17379, 2025.

- Pascal Vincent, Hugo Larochelle, Isabelle Lajoie, Yoshua Bengio, and Pierre-Antoine Manzagol. Stacked denoising autoencoders: Learning useful representations in a deep network with a local denoising criterion. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 11(110):3371–3408, 2010. URL http://jmlr.org/papers/v11/vincent10a.html.

- Ricardo Cardoso Pereira, Miriam Seoane Santos, Pedro Pereira Rodrigues, and Pedro Henriques Abreu. Reviewing autoencoders for missing data imputation: Technical trends, applications and outcomes. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research, 69:1255–1285, 2020.

- Chunyong Yin, Sun Zhang, Jin Wang, and Neal N Xiong. Anomaly detection based on convolutional recurrent autoencoder for iot time series. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics: Systems, 52(1):112–122, 2020.

- Alon Oring. Autoencoder image interpolation by shaping the latent space. Master’s thesis, Reichman University (Israel), 2021.

- Diederik P Kingma, Max Welling, et al. Auto-encoding variational bayes, 2013.

- Gregory Gundersen. The reparameterization trick, April 2018. URL https://gregorygundersen.com/blog/2018/04/29/reparameterization/.

- Borui Cai, Shuiqiao Yang, Longxiang Gao, and Yong Xiang. Hybrid variational autoencoder for time series forecasting. Knowledge-Based Systems, 281:111079, 2023.

- Abhyuday Desai, Cynthia Freeman, Zuhui Wang, and Ian Beaver. Timevae: A variational auto-encoder for multivariate time series generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2111.08095, 2021.

- Julia H Wang, Dexter Tsin, and Tatiana A Engel. Predictive variational autoencoder for learning robust representations of time-series data. ArXiv, pages arXiv–2312, 2023b.

- O. Calin. Deep Learning Architectures: A Mathematical Approach. Springer Series in the Data Sciences. Springer International Publishing, 2020. ISBN 9783030367213. URL https://books.google.mw/books?id=R3vQDwAAQBAJ.

- Youssef Kossale, Mohammed Airaj, and Aziz Darouichi. Mode collapse in generative adversarial networks: An overview. pages 1–6, 10 2022. [CrossRef]

- Tim Salimans, Ian Goodfellow, Wojciech Zaremba, Vicki Cheung, Alec Radford, and Xi Chen. Improved techniques for training gans. Advances in neural information processing systems, 29, 2016.

- Luke Metz, Ben Poole, David Pfau, and Jascha Sohl-Dickstein. Unrolled generative adversarial networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1611.02163, 2016.

- Martin Arjovsky, Soumith Chintala, and Léon Bottou. Wasserstein generative adversarial networks. In International conference on machine learning, pages 214–223. PMLR, 2017.

- Takeru Miyato, Toshiki Kataoka, Masanori Koyama, and Yuichi Yoshida. Spectral normalization for generative adversarial networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1802.05957, 2018.

- Ishaan Gulrajani, Faruk Ahmed, Martin Arjovsky, Vincent Dumoulin, and Aaron C Courville. Improved training of wasserstein gans. Advances in neural information processing systems, 30, 2017.

- Jinsung Yoon, Daniel Jarrett, and Mihaela van der Schaar. Time-series generative adversarial networks. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, volume 32, 2019. URL https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2019/hash/c9efe5f26cd17ba6216bbe2a7d26d490-Abstract.html.

- MohammadReza EskandariNasab, Shah Muhammad Hamdi, and Soukaina Filali Boubrahimi. Seriesgan: Time series generation via adversarial and autoregressive learning. In 2024 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData), pages 860–869. IEEE, 2024.

- Milena Vuletić, Felix Prenzel, and Mihai Cucuringu and. Fin-gan: forecasting and classifying financial time series via generative adversarial networks. Quantitative Finance, 24(2):175–199, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Eoin Brophy, Zhengwei Wang, Qi She, and Tomás Ward. Generative adversarial networks in time series: A systematic literature review. 55(10), 2023. ISSN 0360-0300. [CrossRef]

- Dongrui Zhang, Meng Ma, and Liang Xia. A comprehensive review on gans for time-series signals. Neural Computing and Applications, 34:3551–3571, 2022b. [CrossRef]

- Janosh Riebesell and Stefan Bringuier. Collection of scientific diagrams, 2020. URL https://github.com/janosh/diagrams. 10.5281/zenodo.7486911 - https://github.com/janosh/diagrams.

- Laurent Dinh, Jascha Sohl-Dickstein, and Samy Bengio. Density estimation using real nvp. arXiv preprint arXiv:1605.08803, 2016.

- Laurent Dinh, David Krueger, and Yoshua Bengio. Nice: Non-linear independent components estimation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1410.8516, 2014.

- Ricky TQ Chen, Yulia Rubanova, Jesse Bettencourt, and David K Duvenaud. Neural ordinary differential equations. Advances in neural information processing systems, 31, 2018.

- George Papamakarios, Theo Pavlakou, and Iain Murray. Masked autoregressive flow for density estimation. Advances in neural information processing systems, 30, 2017.

- Enyan Dai and Jie Chen. Graph-augmented normalizing flows for anomaly detection of multiple time series. arXiv preprint arXiv:2202.07857, 2022.

- Siwei Guan, Zhiwei He, Shenhui Ma, and Mingyu Gao. Conditional normalizing flow for multivariate time series anomaly detection. ISA Transactions, 143:231–243, 2023. ISSN 0019-0578. URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0019057823004020. [CrossRef]

- Kashif Rasul, Abdul-Saboor Sheikh, Ingmar Schuster, Urs Bergmann, and Roland Vollgraf. Multivariate probabilistic time series forecasting via conditioned normalizing flows. arXiv preprint arXiv:2002.06103, 2020.

- Wei Fan, Shun Zheng, Pengyang Wang, Rui Xie, Jiang Bian, and Yanjie Fu. Addressing distribution shift in time series forecasting with instance normalization flows. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.16777, 2024.

- Jonathan Ho, Ajay Jain, and Pieter Abbeel. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. Advances in neural information processing systems, 33:6840–6851, 2020.

- Kashif Rasul, Calvin Seward, Ingmar Schuster, and Roland Vollgraf. Autoregressive denoising diffusion models for multivariate probabilistic time series forecasting. In International conference on machine learning, pages 8857–8868. PMLR, 2021.

- Kai Shu, Le Wu, Yuchang Zhao, Aiping Liu, Ruobing Qian, and Xun Chen. Data augmentation for seizure prediction with generative diffusion model. IEEE Transactions on Cognitive and Developmental Systems, 2024.

- Kehua Chen, Guangbo Li, Hewen Li, Yuqi Wang, Wenzhe Wang, Qingyi Liu, and Hongcheng Wang. Quantifying uncertainty: Air quality forecasting based on dynamic spatial-temporal denoising diffusion probabilistic model. Environmental Research, 249:118438, 2024a. ISSN 0013-9351. URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0013935124003426. [CrossRef]

- Xizewen Han, Huangjie Zheng, and Mingyuan Zhou. Card: Classification and regression diffusion models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 35:18100–18115, 2022.

- Si Zuo, Vitor Fortes Rey, Sungho Suh, Stephan Sigg, and Paul Lukowicz. Unsupervised statistical feature-guided diffusion model for sensor-based human activity recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.05285, 2023.

- Yuhang Chen, Chaoyun Zhang, Minghua Ma, Yudong Liu, Ruomeng Ding, Bowen Li, Shilin He, Saravan Rajmohan, Qingwei Lin, and Dongmei Zhang. Imdiffusion: Imputed diffusion models for multivariate time series anomaly detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.00754, 2023b.

- Xuan Liu, Jinglong Chen, Jingsong Xie, and Yuanhong Chang. Generating hsr bogie vibration signals via pulse voltage-guided conditional diffusion model. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, 2024a.

- Yusuke Tashiro, Jiaming Song, Yang Song, and Stefano Ermon. Csdi: Conditional score-based diffusion models for probabilistic time series imputation. Advances in neural information processing systems, 34:24804–24816, 2021.

- Xu Wang, Hongbo Zhang, Pengkun Wang, Yudong Zhang, Binwu Wang, Zhengyang Zhou, and Yang Wang. An observed value consistent diffusion model for imputing missing values in multivariate time series. pages 2409–2418, 08 2023c. [CrossRef]

- Sai Shankar Narasimhan, Shubhankar Agarwal, Oguzhan Akcin, Sujay Sanghavi, and Sandeep Chinchali. Time weaver: A conditional time series generation model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.02682, 2024.

- Guoxuan Chi, Zheng Yang, Chenshu Wu, Jingao Xu, Yuchong Gao, Yunhao Liu, and Tony Xiao Han. Rf-diffusion: Radio signal generation via time-frequency diffusion. In Proceedings of the 30th Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking, pages 77–92, 2024.

- Ling Lin, Ziyang Li, Ruijie Li, et al. Diffusion models for time-series applications: a survey. Frontiers of Information Technology & Electronic Engineering, 25:19–41, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Yiyuan Yang, Ming Jin, Haomin Wen, Chaoli Zhang, Yuxuan Liang, Lintao Ma, Yi Wang, Chenghao Liu, Bin Yang, Zenglin Xu, et al. A survey on diffusion models for time series and spatio-temporal data. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.18886, 2024.

- Abdul Fatir Ansari. Deep Generative Modeling for Images and Time Series. PhD thesis, National University of Singapore, 2022. URL https://scholarbank.nus.edu.sg/handle/10635/231424.

- Kevin P. Murphy. Probabilistic Machine Learning: Advanced Topics. MIT Press, 2023. URL http://probml.github.io/book2.

- Jakub M. Tomczak. Deep Generative Modeling. Springer Cham, 2 edition, 2024. ISBN 978-3-031-64087-2. [CrossRef]

- G. E. Hinton and T. J. Sejnowski. Learning and relearning in Boltzmann machines, page 282–317. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1986. ISBN 026268053X.

- Philémon Brakel, Dirk Stroobandt, and Benjamin Schrauwen. Training energy-based models for time-series imputation. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 14(48):2771–2797, 2013. URL http://jmlr.org/papers/v14/brakel13a.html.

- Tijin Yan, Hongwei Zhang, Tong Zhou, Yufeng Zhan, and Yuanqing Xia. Scoregrad: Multivariate probabilistic time series forecasting with continuous energy-based generative models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.10121, 2021.

- Kevin P. Murphy. Probabilistic Machine Learning: An introduction. MIT Press, 2022. URL probml.ai.

- Wikipedia. Uncertainty quantification. URL https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uncertainty_quantification.

- John Denker, Daniel Schwartz, Ben Wittner, Sara Solla, Richard Howard, Larry Jackel, and John Hopfield. Large automatic learning, rule extraction, and generalization. Complex Systems, 1, 01 1987.

- Naftali Tishby, Esther Levin, and Sara A. Solla. Consistent inference of probabilities in layered networks: Predictions and generalizations. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), pages 403–409. IEEE, 1989. [CrossRef]

- John Denker and Yann LeCun. Transforming neural-net output levels to probability distributions. In R.P. Lippmann, J. Moody, and D. Touretzky, editors, Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, volume 3. Morgan-Kaufmann, 1990. URL https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/1990/file/7eacb532570ff6858afd2723755ff790-Paper.pdf.

- Wray L. Buntine and Andreas S. Weigend. Bayesian back-propagation. Complex Syst., 5, 1991. URL https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:14814125.

- David J. C. MacKay. A practical bayesian framework for backpropagation networks. Neural Computation, 4(3):448–472, 1992. [CrossRef]

- Radford M. Neal. Bayesian learning via stochastic dynamics. In C. L. Giles, S. J. Hanson, and J. D. Cowan, editors, Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 5, pages 475–482, San Mateo, CA, USA, 1992. Morgan Kaufmann.

- Radford M. Neal. Bayesian Learning for Neural Networks. Ph.D. thesis, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada, March 1995. URL http://www.cs.toronto.edu/pub/radford/thesis.pdf. Supervised by Geoffrey Hinton.

- KP Murphy. Machine Learning–A probabilistic Perspective. The MIT Press, 2012.

- Kevin P. Murphy. Conjugate bayesian analysis of the gaussian distribution. Technical report, University of British Columbia, 2007. URL https://www.cs.ubc.ca/~murphyk/Papers/bayesGauss.pdf. Technical Report.

- Teng Gao. How to derive an em algorithm from scratch: From theory to implementation, November 2022. URL https://teng-gao.github.io/blog/2022/ems/.

- W. K. Hastings. Monte Carlo sampling methods using Markov chains and their applications. Biometrika, 57(1):97–109, 04 1970. ISSN 0006-3444. [CrossRef]

- Tshilidzi Marwala, Wilson Tsakane Mongwe, and Rendani Mbuvha. 1 - introduction to hamiltonian monte carlo. In Tshilidzi Marwala, Wilson Tsakane Mongwe, and Rendani Mbuvha, editors, Hamiltonian Monte Carlo Methods in Machine Learning, pages 1–29. Academic Press, 2023. ISBN 978-0-443-19035-3. URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780443190353000136. [CrossRef]

- Jerry Qinghui Yu, Elliot Creager, David Duvenaud, and Jesse Bettencourt. Bayesian neural networks. https://www.cs.toronto.edu/~duvenaud/distill_bayes_net/public/. Tutorial hosted by the University of Toronto.

- James-A Goulet, Luong Ha Nguyen, and Saeid Amiri. Tractable approximate gaussian inference for bayesian neural networks. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 22(251):1–23, 2021.

- H. E. RAUCH, F. TUNG, and C. T. STRIEBEL. Maximum likelihood estimates of linear dynamic systems. AIAA Journal, 3(8):1445–1450, 1965. [CrossRef]

- Bhargob Deka, Luong Ha Nguyen, and James-A. Goulet. Analytically tractable heteroscedastic uncertainty quantification in bayesian neural networks for regression tasks. Neurocomputing, 572:127183, 2024b. ISSN 0925-2312. URL https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0925231223013061. [CrossRef]

- Van-Dai Vuong, Luong-Ha Nguyen, and James-A Goulet. Coupling lstm neural networks and state-space models through analytically tractable inference. International Journal of Forecasting, 2024.

- Nitish Srivastava, Geoffrey Hinton, Alex Krizhevsky, Ilya Sutskever, and Ruslan Salakhutdinov. Dropout: a simple way to prevent neural networks from overfitting. The journal of machine learning research, 15(1):1929–1958, 2014.

- Yarin Gal. Uncertainty in Deep Learning. PhD thesis, University of Cambridge, 2016.

- Charles Blundell, Julien Cornebise, Koray Kavukcuoglu, and Daan Wierstra. Weight uncertainty in neural network. In International conference on machine learning, pages 1613–1622. PMLR, 2015.

- José Miguel Hernández-Lobato and Ryan Adams. Probabilistic backpropagation for scalable learning of bayesian neural networks. In International conference on machine learning, pages 1861–1869. PMLR, 2015.

- Jianxi Yang, Likai Zhang, Cen Chen, Yangfan Li, Ren Li, Guiping Wang, Shixin Jiang, and Zeng Zeng. A hierarchical deep convolutional neural network and gated recurrent unit framework for structural damage detection. Information Sciences, 540:117 – 130, 2020. ISSN 00200255. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85087336888&doi=10.1016%2fj.ins.2020.05.090&partnerID=40&md5=b2102b845c722bf8e8d602963f453ebd. Cited by: 86; All Open Access, Green Open Access. [CrossRef]

- Shiyun Liao, Huijun Liu, Jianxi Yang, and Yongxin Ge. A channel-spatial-temporal attention-based network for vibration-based damage detection. Information Sciences, 606:213 – 229, 2022. ISSN 00200255. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85130546561&doi=10.1016%2fj.ins.2022.05.042&partnerID=40&md5=46fb813cf20534474fdc69b33fdf5ca8. Cited by: 20. [CrossRef]

- Mengmeng Wang, Atilla Incecik, Zhe Tian, Mingyang Zhang, Pentti Kujala, Munish Gupta, Grzegorz Krolczyk, and Zhixiong Li. Structural health monitoring on offshore jacket platforms using a novel ensemble deep learning model. Ocean Engineering, 301, 2024b. ISSN 00298018. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85188522962&doi=10.1016%2fj.oceaneng.2024.117510&partnerID=40&md5=9f5d9802cde5907ca007c87f9cab43a0. Cited by: 9; All Open Access, Hybrid Gold Open Access. [CrossRef]

- Shayan Ghazimoghadam and S.A.A. Hosseinzadeh. A novel unsupervised deep learning approach for vibration-based damage diagnosis using a multi-head self-attention lstm autoencoder. Measurement: Journal of the International Measurement Confederation, 229, 2024. ISSN 02632241. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85186333772&doi=10.1016%2fj.measurement.2024.114410&partnerID=40&md5=966ef02ea702616e5f949ccc0d08312a. Cited by: 16. [CrossRef]

- Youjun Chen, Zeyang Sun, Ruiyang Zhang, Liuzhen Yao, and Gang Wu. Attention mechanism based neural networks for structural post-earthquake damage state prediction and rapid fragility analysis. Computers and Structures, 281, 2023c. ISSN 00457949. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85151284192&doi=10.1016%2fj.compstruc.2023.107038&partnerID=40&md5=b0a0289c594866ab6e76a3fbf1c720a7. Cited by: 20. [CrossRef]

- Xize Chen, Junfeng Jia, Jie Yang, Yulei Bai, and Xiuli Du. A vibration-based 1dcnn-bilstm model for structural state recognition of rc beams. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, 203, 2023d. ISSN 08883270. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85172307004&doi=10.1016%2fj.ymssp.2023.110715&partnerID=40&md5=421567b512cb85018074752daefd7cec. Cited by: 16. [CrossRef]

- Shengyuan Zhang, Chun Min Li, and Wenjing Ye. Damage localization in plate-like structures using time-varying feature and one-dimensional convolutional neural network. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, 147, 2021b. ISSN 08883270. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85089401038&doi=10.1016%2fj.ymssp.2020.107107&partnerID=40&md5=96394d57fe5cd19ed3433ea21c3f292a. Cited by: 124. [CrossRef]

- Niklas Römgens, Abderrahim Abbassi, Clemens Jonscher, Tanja Grießmann, and Raimund Rolfes. On using autoencoders with non-standardized time series data for damage localization. Engineering Structures, 303, 2024. ISSN 01410296. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85183452721&doi=10.1016%2fj.engstruct.2024.117570&partnerID=40&md5=83cc731790a71b164666887010310595. Cited by: 7; All Open Access, Green Open Access, Hybrid Gold Open Access. [CrossRef]

- Yunwoo Lee, Jae Hyuk Lee, Jin-Seop Kim, and Hyungchul Yoon. A hybrid approach of long short-term memory and machine learning with acoustic emission sensors for structural damage localization. IEEE Sensors Journal, 24(23):39529 – 39539, 2024. ISSN 1530437X. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85207375113&doi=10.1109%2fJSEN.2024.3481411&partnerID=40&md5=f69bf25511b139e5aef96e2f35ec0164. Cited by: 0. [CrossRef]

- Héctor Triviño, Cisne Feijóo, Hugo Lugmania, Yolanda Vidal, and Christian Tutivén. Damage detection and localization at the jacket support of an offshore wind turbine using transformer models. Structural Control and Health Monitoring, 2023, 2023. ISSN 15452255. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85181956987&doi=10.1155%2f2023%2f6646599&partnerID=40&md5=1ecd78b8e10dfac5801778a780595311. Cited by: 2; All Open Access, Gold Open Access, Green Open Access. [CrossRef]

- Maziar Jamshidi and Mamdouh El-Badry. Structural damage severity classification from time-frequency acceleration data using convolutional neural networks. Structures, 54:236 – 253, 2023. ISSN 23520124. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85159782832&doi=10.1016%2fj.istruc.2023.05.009&partnerID=40&md5=f1bc2961882bcd8b26d29ed6faae42c5. Cited by: 23. [CrossRef]

- Seyedomid Sajedi and Xiao Liang. Trident: A deep learning framework for high-resolution bridge vibration monitoring. Applied Sciences (Switzerland), 12(21), 2022. ISSN 20763417. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85141862362&doi=10.3390%2fapp122110999&partnerID=40&md5=89531592bf421c4f69805901e9c50ad4. Cited by: 3; All Open Access, Gold Open Access. [CrossRef]

- Sheng Shi, Dongsheng Du, Oya Mercan, Erol Kalkan, and Shuguang Wang. A novel unsupervised real-time damage detection method for structural health monitoring using machine learning. Structural Control and Health Monitoring, 29(10), 2022. ISSN 15452255. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85134644674&doi=10.1002%2fstc.3042&partnerID=40&md5=f7cf5ecbe495949a7578874184333e6e. Cited by: 21; All Open Access, Gold Open Access. [CrossRef]

- Hung V. Dang, Hoa Tran-Ngoc, Tung V. Nguyen, T. Bui-Tien, Guido De Roeck, and Huan X. Nguyen. Data-driven structural health monitoring using feature fusion and hybrid deep learning. IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering, 18(4):2087 – 2103, 2021a. ISSN 15455955. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85116927576&doi=10.1109%2fTASE.2020.3034401&partnerID=40&md5=92827fdc3ee437fa9b47fc878d29e345. Cited by: 87. [CrossRef]

- Viet-Linh Tran. A new framework for damage detection of steel frames using burg autoregressive and stacked autoencoder-based deep neural network. Innovative Infrastructure Solutions, 7(5), 2022. ISSN 23644176. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85135052762&doi=10.1007%2fs41062-022-00888-8&partnerID=40&md5=0a35f9580e3abfa6de7dc4fdc12ed142. Cited by: 4. [CrossRef]

- Sandeep Sony, Sunanda Gamage, Ayan Sadhu, and Jagath Samarabandu. Multiclass damage identification in a full-scale bridge using optimally tuned one-dimensional convolutional neural network. Journal of Computing in Civil Engineering, 36(2), 2022. ISSN 08873801. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85121045985&doi=10.1061%2f%28ASCE%29CP.1943-5487.0001003&partnerID=40&md5=2e71d47d22c9cea3de1dc5e8704b1123. Cited by: 41; All Open Access, Green Open Access. [CrossRef]

- Pasquale Santaniello and Paolo Russo. Bridge damage identification using deep neural networks on time–frequency signals representation. Sensors, 23(13), 2023. ISSN 14248220. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85164843936&doi=10.3390%2fs23136152&partnerID=40&md5=cdbdaee768621f62db562e7e063695d7. Cited by: 12; All Open Access, Gold Open Access, Green Open Access. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad Honarjoo, Ehsan Darvishan, Hassan Rezazadeh, and Amir Homayoon Kosarieh. Sigbert: vibration-based steel frame structural damage detection through fine-tuning bert. International Journal of Structural Integrity, 15(5):851 – 872, 2024. ISSN 17579864. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85203529524&doi=10.1108%2fIJSI-04-2024-0065&partnerID=40&md5=d6d62f82e44ff60a193f9f294740f897. Cited by: 1. [CrossRef]

- Thanh Bui-Tien, Thanh Nguyen-Chi, Thang Le-Xuan, and Hoa Tran-Ngoc. Enhancing bridge damage assessment: Adaptive cell and deep learning approaches in time-series analysis. Construction and Building Materials, 439, 2024. ISSN 09500618. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85198016865&doi=10.1016%2fj.conbuildmat.2024.137240&partnerID=40&md5=72c636e4d310e969cba5b3d24b9a8667. Cited by: 3. [CrossRef]

- Wei Fu, Ruohua Zhou, and Ziye Guo. Concrete acoustic emission signal augmentation method based on generative adversarial networks. Measurement: Journal of the International Measurement Confederation, 231, 2024. ISSN 02632241. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85189758383&doi=10.1016%2fj.measurement.2024.114574&partnerID=40&md5=6dfeb866187dc476798d4762f98095bd. Cited by: 5. [CrossRef]

- Yuanming Lu, Di Wang, Die Liu, and Xianyi Yang. A lightweight and efficient method of structural damage detection using stochastic configuration network. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland), 23(22), 2023a. ISSN 14248220. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85177761636&doi=10.3390%2fs23229146&partnerID=40&md5=63e120ead4d155685de24da12b447ad8. Cited by: 3; All Open Access, Gold Open Access, Green Open Access. [CrossRef]

- Dung Bui-Ngoc, Hieu Nguyen-Tran, Lan Nguyen-Ngoc, Hoa Tran-Ngoc, Thanh Bui-Tien, and Hung Tran-Viet. Damage detection in structural health monitoring using hybrid convolution neural network and recurrent neural network. Frattura ed Integrita Strutturale, 16(59):461 – 470, 2022. ISSN 19718993. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85122427041&doi=10.3221%2fIGF-ESIS.59.30&partnerID=40&md5=69de50235c69a70bf64b812d698bd3fe. Cited by: 29; All Open Access, Gold Open Access. [CrossRef]

- Meng Wu, Xi Xu, Xu Han, and Xiuli Du. Seismic performance prediction of a slope-pile-anchor coupled reinforcement system using recurrent neural networks. Engineering Geology, 338, 2024a. ISSN 00137952. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85198010885&doi=10.1016%2fj.enggeo.2024.107623&partnerID=40&md5=89675afe14586f4197878005cf1023de. Cited by: 3. [CrossRef]

- Ben Huang, Fei Kang, Junjie Li, and Feng Wang. Displacement prediction model for high arch dams using long short-term memory based encoder-decoder with dual-stage attention considering measured dam temperature. Engineering Structures, 280, 2023. ISSN 01410296. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85147189901&doi=10.1016%2fj.engstruct.2023.115686&partnerID=40&md5=a8e071ccad3b633bc922098ada15f0d2. Cited by: 55. [CrossRef]

- Yangtao Li, Tengfei Bao, Jian Gong, Xiaosong Shu, and Kang Zhang. The prediction of dam displacement time series using stl, extra-trees, and stacked lstm neural network. IEEE Access, 8:94440 – 94452, 2020. ISSN 21693536. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85086041637&doi=10.1109%2fACCESS.2020.2995592&partnerID=40&md5=c7e10a14d614e7d9bbedcb7fdcc10703. Cited by: 95; All Open Access, Gold Open Access. [CrossRef]

- Xiao-Wei Ye, Si-Yuan Ma, Zhi-Xiong Liu, Yan-Bo Chen, Ci-Rong Lu, Yue-Jun Song, Xiao-Jun Li, and Li-An Zhao. Lstm-based deformation forecasting for additional stress estimation of existing tunnel structure induced by adjacent shield tunneling. Tunnelling and Underground Space Technology, 146, 2024. ISSN 08867798. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85185410299&doi=10.1016%2fj.tust.2024.105664&partnerID=40&md5=83284916443a02dbd9dbba27ac44ba55. Cited by: 9. [CrossRef]

- Xiang Xu, Donghui Xu, Antonio Caballero, Yuan Ren, Qiao Huang, Weijie Chang, and Michael C. Forde. Vehicle-induced deflection prediction using long short-term memory networks. Structures, 54:596 – 606, 2023b. ISSN 23520124. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85160007801&doi=10.1016%2fj.istruc.2023.04.025&partnerID=40&md5=3ff05605d831828601945402f11c37dc. Cited by: 6. [CrossRef]

- Xinhui Xiao, Zepeng Wang, Haiping Zhang, Yuan Luo, Fanghuai Chen, Yang Deng, Naiwei Lu, and Ying Chen. A novel method of bridge deflection prediction using probabilistic deep learning and measured data. Sensors, 24(21), 2024. ISSN 14248220. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85208608421&doi=10.3390%2fs24216863&partnerID=40&md5=cd14ea55ef52a14971295d8b88997df7. Cited by: 0; All Open Access, Gold Open Access. [CrossRef]

- Shanwu Li, Suchao Li, Shujin Laima, and Hui Li. Data-driven modeling of bridge buffeting in the time domain using long short-term memory network based on structural health monitoring. Structural Control and Health Monitoring, 28(8), 2021a. ISSN 15452255. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85105098495&doi=10.1002%2fstc.2772&partnerID=40&md5=ae98db2834c7ca4df8ec2d6211ae4435. Cited by: 49; All Open Access, Gold Open Access. [CrossRef]

- Vahid Barzegar, Simon Laflamme, Chao Hu, and Jacob Dodson. Ensemble of recurrent neural networks with long short-term memory cells for high-rate structural health monitoring. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, 164, 2022. ISSN 08883270. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85110418960&doi=10.1016%2fj.ymssp.2021.108201&partnerID=40&md5=b556cf1807fa1b271f2a3ab0617e8a05. Cited by: 32; All Open Access, Bronze Open Access, Green Open Access. [CrossRef]

- Zhuoran Ma and Liang Gao. Predicting mechanical state of high-speed railway elevated station track system using a hybrid prediction model. KSCE Journal of Civil Engineering, 25(7):2474 – 2486, 2021. ISSN 12267988. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85104151877&doi=10.1007%2fs12205-021-1307-z&partnerID=40&md5=94fef56fc082ca229817637d8ae8cc6c. Cited by: 8. [CrossRef]

- Zhi-wei Wang, Xiao-fan Lu, Wen-ming Zhang, Vasileios C. Fragkoulis, Yu-feng Zhang, and Michael Beer. Deep learning-based prediction of wind-induced lateral displacement response of suspension bridge decks for structural health monitoring. Journal of Wind Engineering and Industrial Aerodynamics, 247, 2024c. ISSN 01676105. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85186503997&doi=10.1016%2fj.jweia.2024.105679&partnerID=40&md5=e656f6fa1ff803c0c3deb78f2330759e. Cited by: 7. [CrossRef]

- Byung Kwan Oh, Hyo Seon Park, and Branko Glisic. Prediction of long-term strain in concrete structure using convolutional neural networks, air temperature and time stamp of measurements. Automation in Construction, 126, 2021. ISSN 09265805. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85102361606&doi=10.1016%2fj.autcon.2021.103665&partnerID=40&md5=63ddaaed8bef178f90384975fef90f29. Cited by: 35. [CrossRef]

- Hyo Seon Park, Taehoon Hong, Dong-Eun Lee, Byung Kwan Oh, and Branko Glisic. Long-term structural response prediction models for concrete structures using weather data, fiber-optic sensing, and convolutional neural network. Expert Systems with Applications, 201, 2022. ISSN 09574174. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85129466337&doi=10.1016%2fj.eswa.2022.117152&partnerID=40&md5=562f83bb03ba42994b49f2842e90e20e. Cited by: 12. [CrossRef]

- Xin Yu, Junjie Li, and Fei Kang. Ssa optimized back propagation neural network model for dam displacement monitoring based on long-term temperature data. European Journal of Environmental and Civil Engineering, 27(4):1617 – 1643, 2023. ISSN 19648189. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85132829800&doi=10.1080%2f19648189.2022.2090445&partnerID=40&md5=77ab2ff14ccb19d442702a2eb86354b2. Cited by: 3. [CrossRef]

- Dongyang Yuan, Chongshi Gu, Bowen Wei, Xiangnan Qin, and Hao Gu. Displacement behavior interpretation and prediction model of concrete gravity dams located in cold area. Structural Health Monitoring, 22(4):2384 – 2401, 2023. ISSN 14759217. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85139059161&doi=10.1177%2f14759217221122368&partnerID=40&md5=212eea9ff439b170d677762de067751a. Cited by: 17. [CrossRef]

- Zhiyao Lu, Guantao Zhou, Yong Ding, and Denghua Li. Prediction and analysis of response behavior of concrete face rockfill dam in cold region. Structures, 70, 2024. ISSN 23520124. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85208686199&doi=10.1016%2fj.istruc.2024.107732&partnerID=40&md5=26beed20f3b3bd75cd6ae9aab684af97. Cited by: 0. [CrossRef]

- Han-Wei Zhao, You-Liang Ding, Ai-Qun Li, Bin Chen, and Kun-Peng Wang. Digital modeling approach of distributional mapping from structural temperature field to temperature-induced strain field for bridges. Journal of Civil Structural Health Monitoring, 13(1):251 – 267, 2023. ISSN 21905452. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85140052808&doi=10.1007%2fs13349-022-00635-8&partnerID=40&md5=cfa45ece3e937a6c15a58997c2ce4560. Cited by: 31. [CrossRef]

- Kang Yang, Youliang Ding, Fangfang Geng, Huachen Jiang, and Zhengbo Zou. A multi-sensor mapping bi-lstm model of bridge monitoring data based on spatial-temporal attention mechanism. Measurement: Journal of the International Measurement Confederation, 217, 2023. ISSN 02632241. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85160021665&doi=10.1016%2fj.measurement.2023.113053&partnerID=40&md5=19d810669ea2789762e340919f1f5ed0. Cited by: 13. [CrossRef]

- Jihao Ma and Jingpei Dan. Long-term structural state trend forecasting based on an fft–informer model. Applied Sciences (Switzerland), 13(4), 2023. ISSN 20763417. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85149304527&doi=10.3390%2fapp13042553&partnerID=40&md5=298ad1467151b12da3e71e052f7bf9ff. Cited by: 8; All Open Access, Gold Open Access. [CrossRef]

- Ziqi Li, Dongsheng Li, and Tianshu Sun. A transformer-based bridge structural response prediction framework. Sensors, 22(8), 2022a. ISSN 14248220. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85128351219&doi=10.3390%2fs22083100&partnerID=40&md5=d6ed2af86959a95c80e10c454d7f2a13. Cited by: 3; All Open Access, Gold Open Access, Green Open Access. [CrossRef]

- Ying Zhou, Shiqiao Meng, Yujie Lou, and Qingzhao Kong. Physics-informed deep learning-based real-time structural response prediction method. Engineering, 35:140 – 157, 2024a. ISSN 20958099. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85190104653&doi=10.1016%2fj.eng.2023.08.011&partnerID=40&md5=0c12dc2dd566d17fac1d9e0f687865c5. Cited by: 15; All Open Access, Gold Open Access. [CrossRef]

- Mauricio Pereira and Branko Glisic. Physics-informed data-driven prediction of 2d normal strain field in concrete structures. Sensors, 22(19), 2022a. ISSN 14248220. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85139948522&doi=10.3390%2fs22197190&partnerID=40&md5=eb048466249eb9371d8a6f8cf394669b. Cited by: 7; All Open Access, Gold Open Access, Green Open Access. [CrossRef]

- Jianwen Pan, Wenju Liu, Changwei Liu, and Jinting Wang. Convolutional neural network-based spatiotemporal prediction for deformation behavior of arch dams. Expert Systems with Applications, 232, 2023. ISSN 09574174. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85163800056&doi=10.1016%2fj.eswa.2023.120835&partnerID=40&md5=91056ae3d6e27f0c62f719fe2fcfb580. Cited by: 25. [CrossRef]

- Xuyan Tan, Weizhong Chen, Jianping Yang, Bowen Du, and Tao Zou. Prediction for segment strain and opening of underwater shield tunnel using deep learning method. Transportation Geotechnics, 39, 2023a. ISSN 22143912. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85146095944&doi=10.1016%2fj.trgeo.2023.100928&partnerID=40&md5=ea05e1e6b47326d5f91584188b582643. Cited by: 11. [CrossRef]

- Hyo Seon Park, Jung Hwan An, Young Jun Park, and Byung Kwan Oh. Convolutional neural network-based safety evaluation method for structures with dynamic responses. Expert Systems with Applications, 158, 2020. ISSN 09574174. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85086798436&doi=10.1016%2fj.eswa.2020.113634&partnerID=40&md5=a25a5fcaadaef426237a1b3d4dddcd11. Cited by: 29. [CrossRef]

- Abbas Ghaffari, Yaser Shahbazi, Mohsen Mokhtari Kashavar, Mohammad Fotouhi, and Siamak Pedrammehr. Advanced predictive structural health monitoring in high-rise buildings using recurrent neural networks. Buildings, 14(10), 2024. ISSN 20755309. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85207362946&doi=10.3390%2fbuildings14103261&partnerID=40&md5=42f46e81441492bca44b28300e706c83. Cited by: 1; All Open Access, Gold Open Access. [CrossRef]

- Yadi Tian, Yang Xu, Dongyu Zhang, and Hui Li. Relationship modeling between vehicle-induced girder vertical deflection and cable tension by bilstm using field monitoring data of a cable-stayed bridge. Structural Control and Health Monitoring, 28(2), 2021. ISSN 15452255. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85096791711&doi=10.1002%2fstc.2667&partnerID=40&md5=828d4d020fbe1f3920cbf8f9e33dcfb8. Cited by: 43; All Open Access, Gold Open Access. [CrossRef]

- Shaowei Wang, Bingao Chai, Yi Liu, and Hao Gu. A causal prediction model for the measured temperature field of high arch dams with dual simulation of lag influencing mechanism. Structures, 58, 2023d. ISSN 23520124. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85177191358&doi=10.1016%2fj.istruc.2023.105568&partnerID=40&md5=b54e61bd56b3945634cba61e25d48ad8. Cited by: 6. [CrossRef]

- Linren Zhou, Taojun Wang, and Yumeng Chen. Bridge temperature prediction method based on long short-term memory neural networks and shared meteorological data. Advances in Structural Engineering, 27(8):1349 – 1360, 2024b. ISSN 13694332. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85190839205&doi=10.1177%2f13694332241247918&partnerID=40&md5=51a82b816df22025e6418961af6dc12c. Cited by: 2. [CrossRef]

- Jersson X. Leon-Medina, Ricardo Cesar Gomez Vargas, Camilo Gutierrez-Osorio, Daniel Alfonso Garavito Jimenez, Diego Alexander Velandia Cardenas, Julián Esteban Salomón Torres, Jaiber Camacho-Olarte, Bernardo Rueda, Whilmar Vargas, Jorge Sofrony Esmeral, Felipe Restrepo-Calle, Diego Alexander Tibaduiza Burgos, and Cesar Pedraza Bonilla. Deep learning for the prediction of temperature time series in the lining of an electric arc furnace for structural health monitoring at cerro matoso (cmsa) †. Engineering Proceedings, 2(1), 2020. ISSN 26734591. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85117088545&doi=10.3390%2fecsa-7-08246&partnerID=40&md5=941a04d04e70865bcc016ebdf9e1de96. Cited by: 8; All Open Access, Hybrid Gold Open Access. [CrossRef]

- Jersson X. Leon-Medina, Jaiber Camacho, Camilo Gutierrez-Osorio, Julián Esteban Salomón, Bernardo Rueda, Whilmar Vargas, Jorge Sofrony, Felipe Restrepo-Calle, Cesar Pedraza, and Diego Tibaduiza. Temperature prediction using multivariate time series deep learning in the lining of an electric arc furnace for ferronickel production. Sensors, 21(20), 2021. ISSN 14248220. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85117096620&doi=10.3390%2fs21206894&partnerID=40&md5=4302a2369d25f0c8a415650c6c21cddc. Cited by: 19; All Open Access, Gold Open Access, Green Open Access. [CrossRef]

- Diego F. Godoy-Rojas, Jersson X. Leon-Medina, Bernardo Rueda, Whilmar Vargas, Juan Romero, Cesar Pedraza, Francesc Pozo, and Diego A. Tibaduiza. Attention-based deep recurrent neural network to forecast the temperature behavior of an electric arc furnace side-wall. Sensors, 22(4), 2022. ISSN 14248220. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85124362038&doi=10.3390%2fs22041418&partnerID=40&md5=d5c7ad8b7a7cd6c376089005fe887d05. Cited by: 11; All Open Access, Gold Open Access, Green Open Access. [CrossRef]

- Qiushuang Lin and Chunxiang Li. Simplified-boost reinforced model-based complex wind signal forecasting. Advances in Civil Engineering, 2020, 2020. ISSN 16878086. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85093088278&doi=10.1155%2f2020%2f9564287&partnerID=40&md5=c4bccf8e0834adfb9be792c02b4db2ed. Cited by: 0; All Open Access, Gold Open Access. [CrossRef]

- Yang Ding, Xiao-Wei Ye, and Yong Guo. A multistep direct and indirect strategy for predicting wind direction based on the emd-lstm model. Structural Control and Health Monitoring, 2023, 2023. ISSN 15452255. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85162208617&doi=10.1155%2f2023%2f4950487&partnerID=40&md5=8d8da4a0224d823bb0559998fce79eb4. Cited by: 43; All Open Access, Gold Open Access. [CrossRef]

- Jae-Yeong Lim, Sejin Kim, Ho-Kyung Kim, and Young-Kuk Kim. Long short-term memory (lstm)-based wind speed prediction during a typhoon for bridge traffic control. Journal of Wind Engineering and Industrial Aerodynamics, 220, 2022. ISSN 01676105. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85120429348&doi=10.1016%2fj.jweia.2021.104788&partnerID=40&md5=20023df00a50422a085103280ca8b102. Cited by: 41. [CrossRef]

- Yonghui Lu, Liqun Tang, Chengbin Chen, Licheng Zhou, Zejia Liu, Yiping Liu, Zhenyu Jiang, and Bao Yang. Reconstruction of structural long-term acceleration response based on bilstm networks. Engineering Structures, 285, 2023b. ISSN 01410296. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85151370560&doi=10.1016%2fj.engstruct.2023.116000&partnerID=40&md5=7c08ecc01e7b750fe1057457dbb2648d. Cited by: 46. [CrossRef]

- Yangtao Li, Tengfei Bao, Hao Chen, Kang Zhang, Xiaosong Shu, Zexun Chen, and Yuhan Hu. A large-scale sensor missing data imputation framework for dams using deep learning and transfer learning strategy. Measurement: Journal of the International Measurement Confederation, 178, 2021b. ISSN 02632241. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85105695016&doi=10.1016%2fj.measurement.2021.109377&partnerID=40&md5=5712580af1f429a5461a6572929dca1b. Cited by: 65. [CrossRef]

- Chengbin Chen, Liqun Tang, Yonghui Lu, Yong Wang, Zejia Liu, Yiping Liu, Licheng Zhou, Zhenyu Jiang, and Bao Yang. Reconstruction of long-term strain data for structural health monitoring with a hybrid deep-learning and autoregressive model considering thermal effects. Engineering Structures, 285, 2023e. ISSN 01410296. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85151710954&doi=10.1016%2fj.engstruct.2023.116063&partnerID=40&md5=0d0a0e1a4885240af0d6999064a4d1a4. Cited by: 22. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen Thi Cam Nhung, Hoang Nguyen Bui, and Tran Quang Minh. Enhancing recovery of structural health monitoring data using cnn combined with gru. Infrastructures, 9(11), 2024. ISSN 24123811. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85210353081&doi=10.3390%2finfrastructures9110205&partnerID=40&md5=af62f5906ec4deae3b3096980149c724. Cited by: 0. [CrossRef]

- Bowen Du, Liyu Wu, Leilei Sun, Fei Xu, and Linchao Li. Heterogeneous structural responses recovery based on multi-modal deep learning. Structural Health Monitoring, 22(2):799 – 813, 2023. ISSN 14759217. URL https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85131104622&doi=10.1177%2f14759217221094499&partnerID=40&md5=469a8c2c42822dbf8016be442477d849. Cited by: 12. [CrossRef]