1. Introduction

The rise of AI-generated content poses challenges to text authenticity in academia, media, and online platforms. Large language models (LLMs) like GPT-3 and BERT blur the distinction between human-written and AI-generated text. However, traditional classification models relying on long contexts demand significant computational resources, limiting their real-time applicability and efficiency for short texts.

This study proposes a teacher-student framework for efficient AI-generated text detection, optimized for short contexts. The teacher model integrates DeBERTa-v3-large and Mamba-790m, fine-tuned on domain-specific data to extract deep semantic features. The student model, trained by the teacher, focuses on short texts (128–256 tokens) to balance accuracy and computational efficiency.

Experimental results, leveraging vLLM-generated diverse AI texts and data augmentation (e.g., spelling correction, character removal, case flipping), demonstrate superior performance compared to single-base models like DeBERTa and Mamba in metrics such as accuracy, F1-score, LogLoss, and AUROC. This framework enhances model robustness while reducing computational costs, paving the way for advancements in multilingual classification and real-time AI-driven inference.

2. Related Work

Detecting AI-generated text in short-context documents has gained attention in recent studies. Several works have explored AI’s role in areas like education, language processing, and e-commerce.

In education, Baskara[

1] studied the effects of AI on teacher-student interactions in English Language Teaching (ELT). Shen [

2] proposed a computation offloading method leveraging 5G Mobile Edge Computing (MEC) units to enhance real-time technical market analysis on mobile devices, demonstrating reduced system latency and improved processing of real-time trading scripts.Sun et al. [

3] proposed a multi-objective recommender system using a two-stage reranking model and ensemble learning to optimize consumer behaviors in e-commerce.

In language processing, Xu and Wang [

4] present a hybrid MOE-LLM model for healthcare recommendations, outperforming baselines in metrics like Precision and Recall while addressing challenges with image data and cold start issues. In e-commerce, Lu et al.[

5] and Lu[

6] studied hybrid machine learning models to improve purchase predictions and chatbot user satisfaction. The advanced ensemble techniques in [

7], integrating Random Forests, Gradient Boosting Machines, and Neural Networks, directly influenced the optimization strategies in this work. Specifically, its adaptive learning rates, dynamic feature weighting, and robust preprocessing inspired the teacher-student framework, enhancing accuracy and efficiency in short-context classification.

Li et al.[

8] also proposed multimodal strategies to improve product recommendations, Jin [

9] pioneered ATCN with reinforcement learning for supply chain optimization, influencing our temporal modeling and optimization strategies in the teacher-student framework.Yang [

10] optimized data hiding in binary images, enhancing capacity and reducing visual distortion for real-time security applications. Li et al.[

11] introduced a dual-agent approach for deductive reasoning in large language models, which could help improve AI text detection.

These studies advance AI’s use in education, e-commerce, and language models, but do not directly address detecting AI-generated text in short-context documents. Our work fills this gap by introducing a teacher-student model that uses domain-specific fine-tuning and data augmentation to improve short-context document classification, providing a strong framework for detecting AI-generated content.

3. Methodology

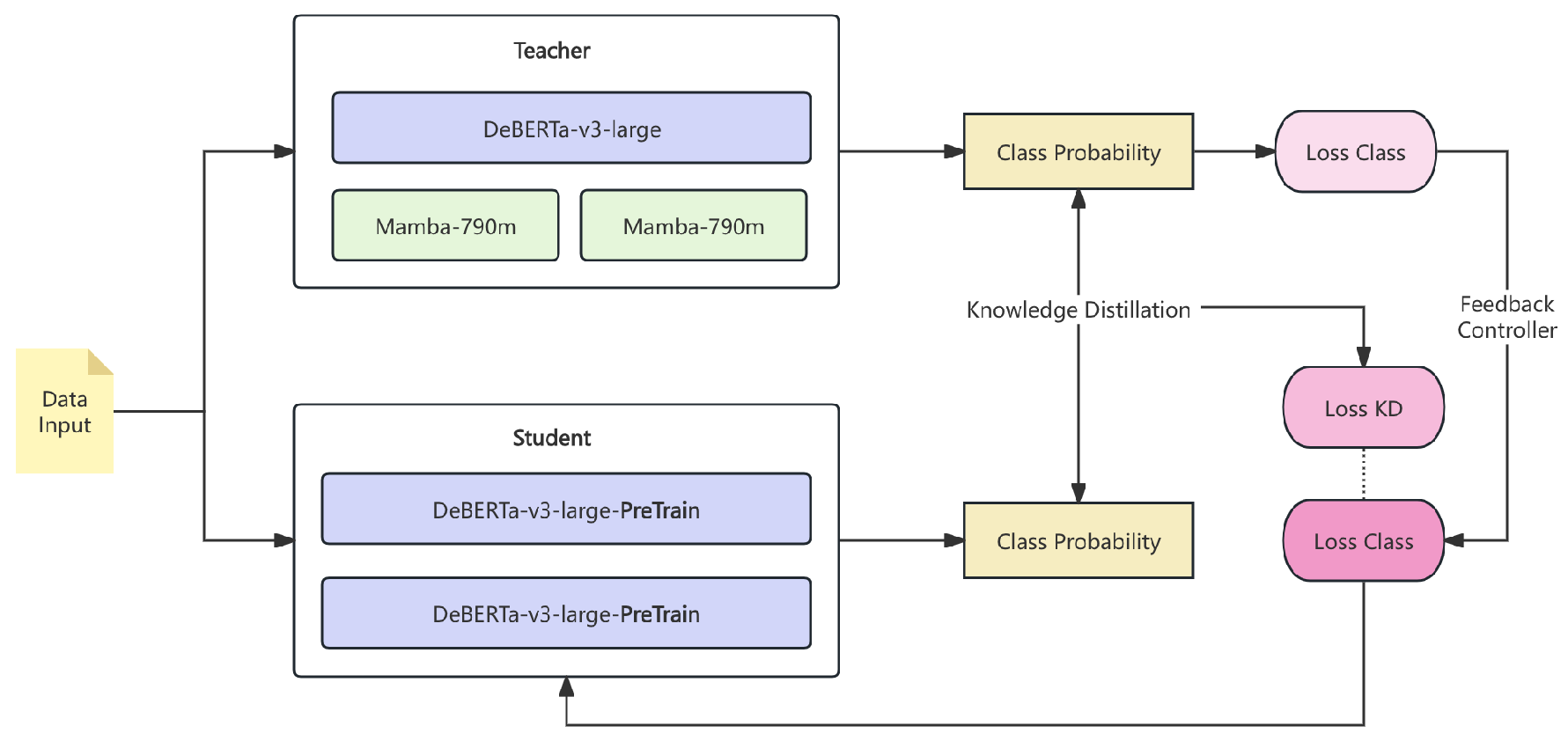

This section introduces an innovative method for optimizing short-context models in document classification through a teacher-student framework with domain adaptation. Leveraging pre-trained knowledge from large language models (LLMs), the methodology enhances feature extraction and domain transfer. By integrating diverse datasets, domain-specific features, and data augmentation, the approach fine-tunes the LLM-based teacher model to capture domain nuances, while the distilled student model ensures efficiency without compromising accuracy. Results highlight the effectiveness of short-context models in utilizing LLMs’ semantic capabilities to improve performance across tasks.

3.1. Data Preprocessing

The data preprocessing pipeline consists of several essential steps: data generation, data augmentation, data validation, and dataset splitting. These steps were designed to ensure data quality and robustness while preparing the training set for effective model learning.

3.1.1. Data Generation

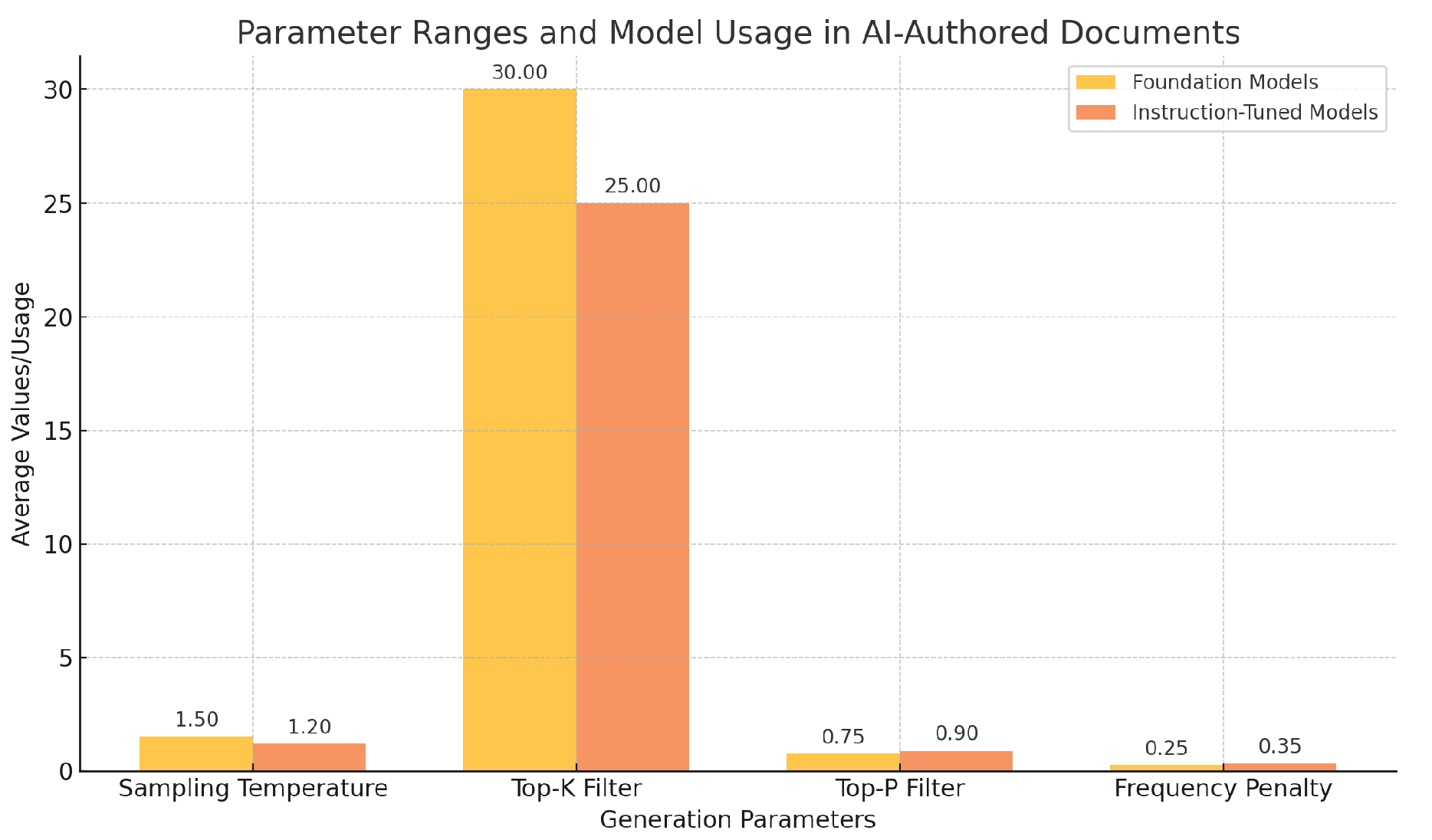

We generated AI-authored documents using the

vLLM tool, which ran on 2x RTX 3090 and 1x RTX 4090 GPUs. The documents were generated with varying sampling parameters to introduce diversity in the generated content. The key generation parameters are summarized in

Table 1 and

Figure 1 shows the average values of key generation parameters for foundation and instruction-tuned models, highlighting their diverse usage preferences.

We used two types of models for generating completions: foundation models (document prefixes) and instruction-tuned models (user instructions and leading words).

3.1.2. Data Augmentation

To improve model robustness, we applied several data augmentation techniques, as summarized in

Table 2. Each technique introduces variability to simulate real-world data noise.

3.1.3. Data Validation and Quality Check

After data augmentation, we performed a quality check to ensure the validity of the generated documents. Low-quality documents were filtered out, and the dataset was normalized. The normalization formula for a feature vector

is given by:

where

and

are the mean and standard deviation of the feature values.

3.1.4. Data Splitting

The dataset was divided into training, validation, and test sets with a 70-15-15 split, ensuring ample data for model training and evaluation. The preprocessing ensured a diverse, clean dataset representative of real-world scenarios, critical for effective machine learning models.

3.2. Teacher Model

This section outlines the teacher-student model architecture and training process, as shown in

Figure 2. The teacher ensemble comprises a DeBERTa-v3-large model and two Mamba-790m models, while two student models are trained to mimic the teacher ensemble’s predictions.

3.2.1. DeBERTa Model

The DeBERTa-v3-large model serves as the primary teacher, fine-tuned on the training dataset to provide core predictions.

3.2.2. Mamba Models

Two Mamba-790m models, offering memory efficiency, complement the teacher ensemble.

3.2.3. Ensemble Model

The final teacher prediction,

, is a weighted average of predictions from DeBERTa (

) and the Mamba models (

,

):

This approach prioritizes the more accurate DeBERTa model.

3.3. Student Model

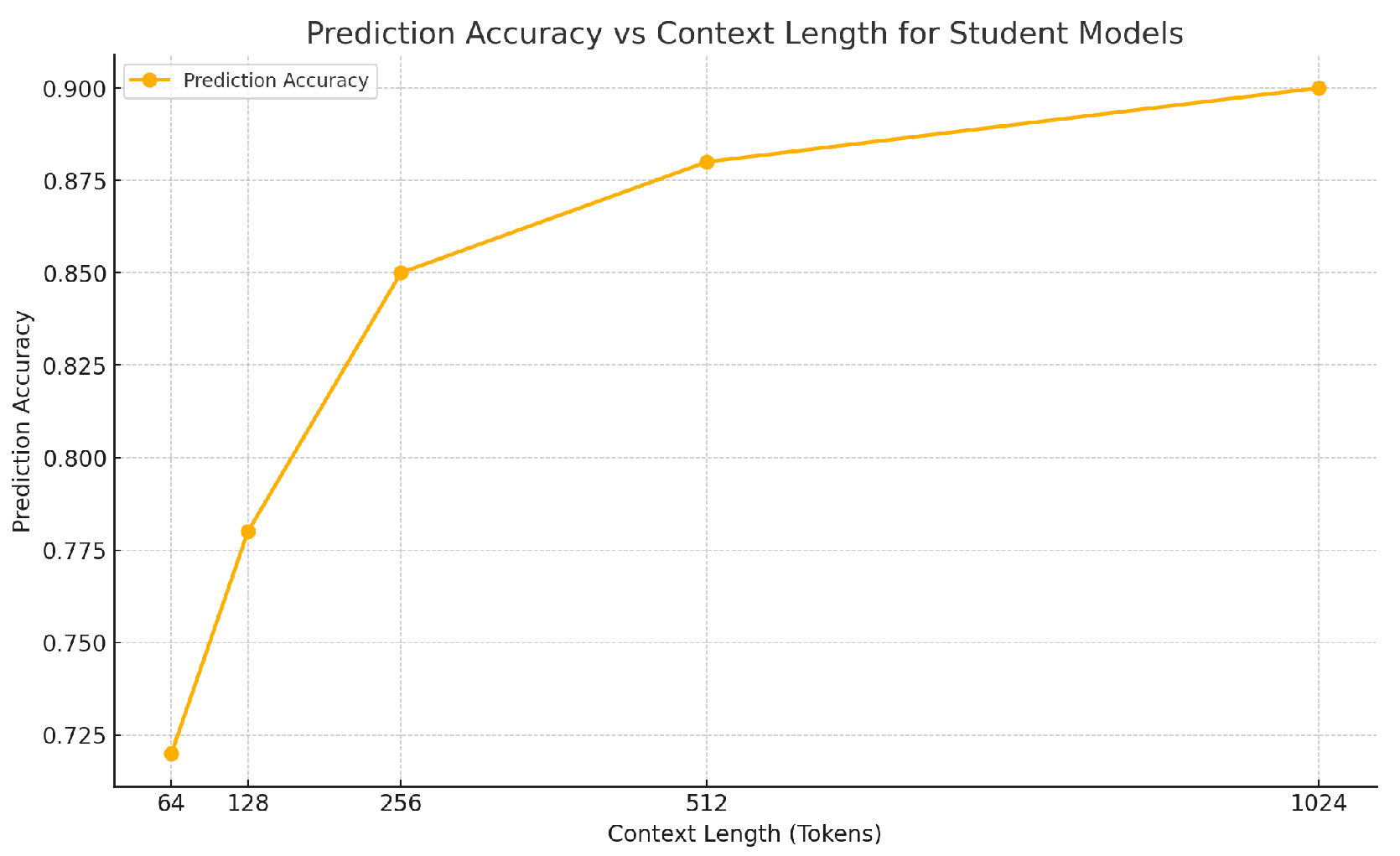

The student models mimic the teacher model’s predictions on short-context chunks of test documents. Each student model is a fine-tuned DeBERTa-v3-large model with different context lengths.

Let the context lengths for the two student models be

tokens and

tokens. These models are fine-tuned to replicate the teacher ensemble’s predictions based on randomly selected short chunks of test documents. The prediction from a student model

is denoted as

, where

i corresponds to the model’s context length. As shown in

Figure 3, shorter contexts reduce performance, while longer contexts capture more information, improving accuracy, though with diminishing returns.

3.4. Training of the Student Model

The student models are trained to minimize the discrepancy between their predictions and the teacher’s ensemble predictions. The loss function used during student model training is the mean squared error (MSE) between the student model’s output

and the teacher’s output

:

where

N is the number of test examples in the batch.

During training, the student models are updated using backpropagation, and their parameters are adjusted to minimize this loss. The training procedure is done in the following steps:

3.4.1. Data Selection

Random chunks of documents are selected with stride equal to half the context length.

3.4.2. Prediction Averaging

The final prediction for each document is averaged over the multiple chunks.

3.5. Training Details and Fine-Tuning

The student models are pretrained on a dataset of 1 million documents generated during data preprocessing. Key fine-tuning details include:

Context Length: One model uses a context length of 128 tokens, while the other uses 256 tokens.

Batch Size: Both models are trained with a batch size of 16 for short-context inputs.

Learning Rate: A linear warm-up followed by linear decay is employed, improving training stability and adaptation.

Dropout: Dropout is disabled during training and inference, ensuring consistent predictions.

3.6. Inference Process

The student models generate predictions for test documents, with the final prediction computed by averaging their outputs. Let

and

denote predictions from the models with context lengths of 128 and 256 tokens, respectively. The final prediction

is given by:

This weighted average prioritizes the model with shorter context length, 128 tokens, to better capture dataset-specific patterns.

4. Evaluation Metrics

To comprehensively evaluate the model’s performance, we employed the following four metrics:

5. Experiment Results

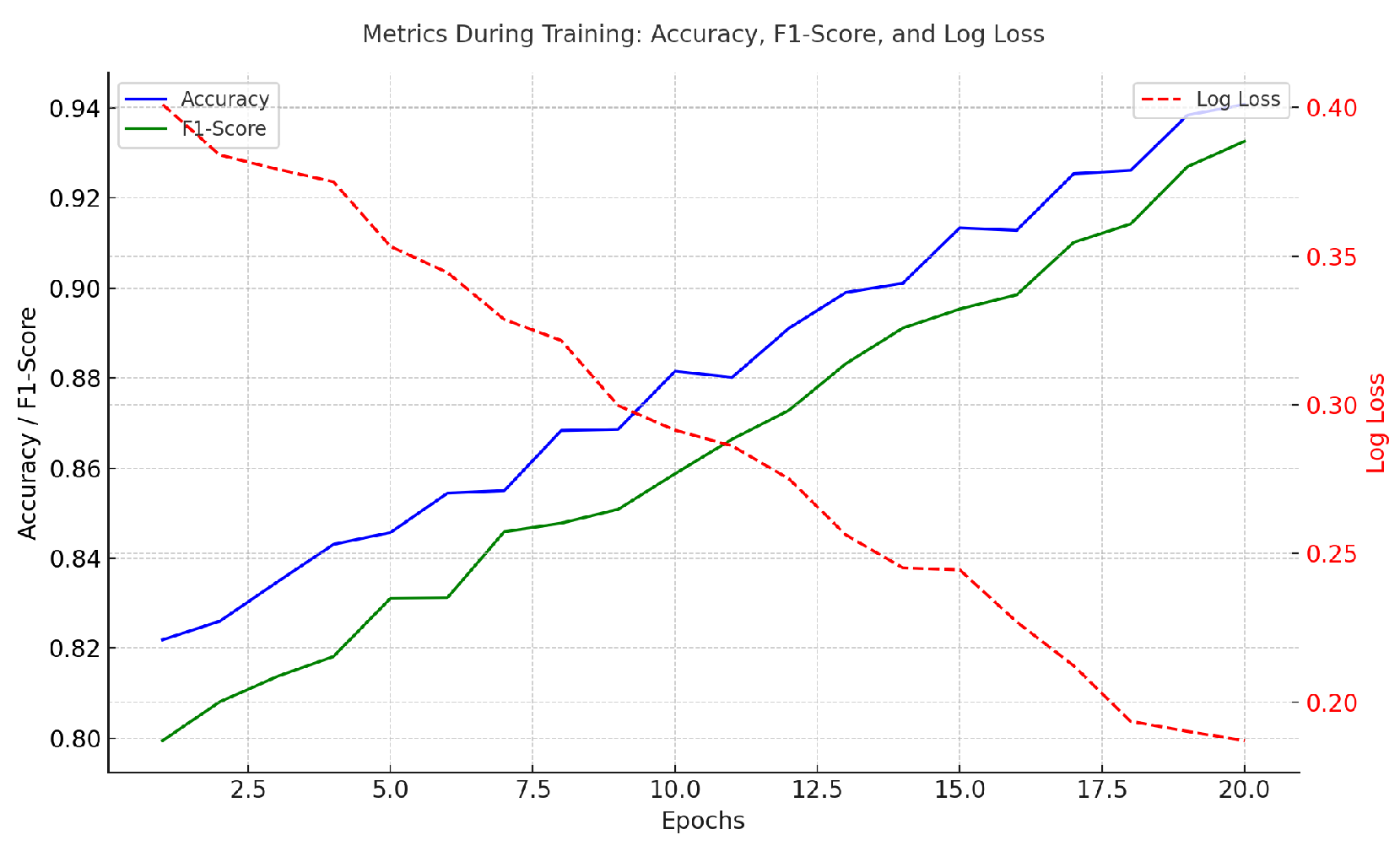

We conducted experiments to compare our proposed approach with baseline models and perform ablation studies to understand the contribution of each component. The results are presented in

Table 3 and

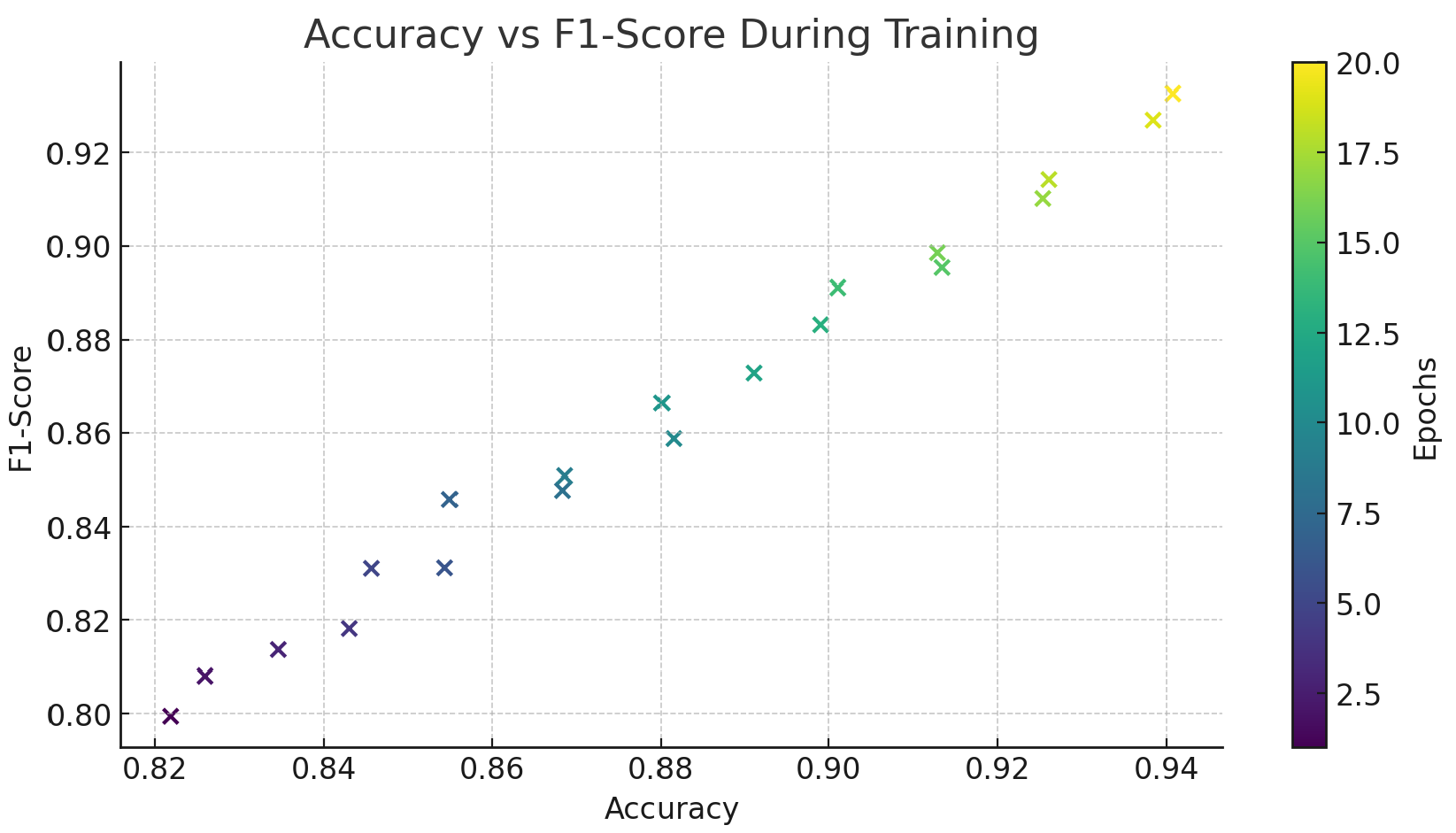

Table 4. And illustrates the training process, showing the improvement of Accuracy and F1-Score alongside the reduction in Log Loss, demonstrating effective model convergence in

Figure 4 and in

Figure 5 shows the relationship between Accuracy and F1-Score through a scatter plot. Different colors represent different training rounds, showing that both improve synchronously with training.

The results demonstrate that both data augmentation and short-context training significantly contribute to the performance, with the full model achieving the best results.

6. Conclusion

This study presented a teacher-student framework leveraging LLMs for efficient short-context document classification. By combining domain adaptation, data augmentation, and ensemble modeling, the approach significantly improved accuracy, F1-score, LogLoss, and AUROC over baselines. Ablation studies highlighted the importance of data augmentation and short-context training. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of integrating LLMs to enhance performance in diverse text detection tasks.

References

- Baskara, F.R. AI-Driven Dynamics: ChatGPT Transforming ELT Teacher-Student Interactions. Lensa: Kajian Kebahasaan, Kesusastraan, dan Budaya 2023, 13, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, G. Computation Offloading for Better Real-Time Technical Market Analysis on Mobile Devices. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2021 3rd International Conference on Image Processing and Machine Vision, 2021, pp. 72–76.

- Sun, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Zou, D.; Li, N.; Chen, H. A Multi-Objective Recommender System for Enhanced Consumer Behavior Prediction in E-Commerce. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 6th International Conference on Power, Intelligent Computing and Systems (ICPICS). IEEE; 2024; pp. 884–889. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Wang, Y. Enhancing Healthcare Recommendation Systems with a Multimodal LLMs-based MOE Architecture. arXiv arXiv:2412.11557 2024. [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Long, Y.; Li, X.; Shen, Y.; Wang, X. Hybrid Model Integration of LightGBM, DeepFM, and DIN for Enhanced Purchase Prediction on the Elo Dataset. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 7th International Conference on Information Systems and Computer Aided Education (ICISCAE). IEEE; 2024; pp. 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J. Enhancing Chatbot User Satisfaction: A Machine Learning Approach Integrating Decision Tree, TF-IDF, and BERTopic. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 6th International Conference on Power, Intelligent Computing and Systems (ICPICS). IEEE; 2024; pp. 823–828. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, T. Integrated Machine Learning for Enhanced Supply Chain Risk Prediction 2025.

- Li, S. Harnessing multimodal data and mult-recall strategies for enhanced product recommendation in e-commerce. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Computer Systems (ICCS). IEEE; 2024; pp. 181–185. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, T. Attention-Based Temporal Convolutional Networks and Reinforcement Learning for Supply Chain Delay Prediction and Inventory Optimization 2025.

- Yang, Y. Large Capacity Data Hiding in Binary Image black and white mixed regions. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd International Conference on Electronic Information Engineering and Computer (EIECT). IEEE; 2023; pp. 516–521. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Zhou, X.; Wu, Z.; Long, Y.; Shen, Y. Strategic deductive reasoning in large language models: A dual-agent approach. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 6th International Conference on Power, Intelligent Computing and Systems (ICPICS). IEEE; 2024; pp. 834–839. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).