Submitted:

29 May 2025

Posted:

30 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Seafood Allergens and Their Molecular Properties

2.1. Fish Allergens

2.2. Shellfish Allergens

3. Effect of Processing Techniques on Seafood Allergens

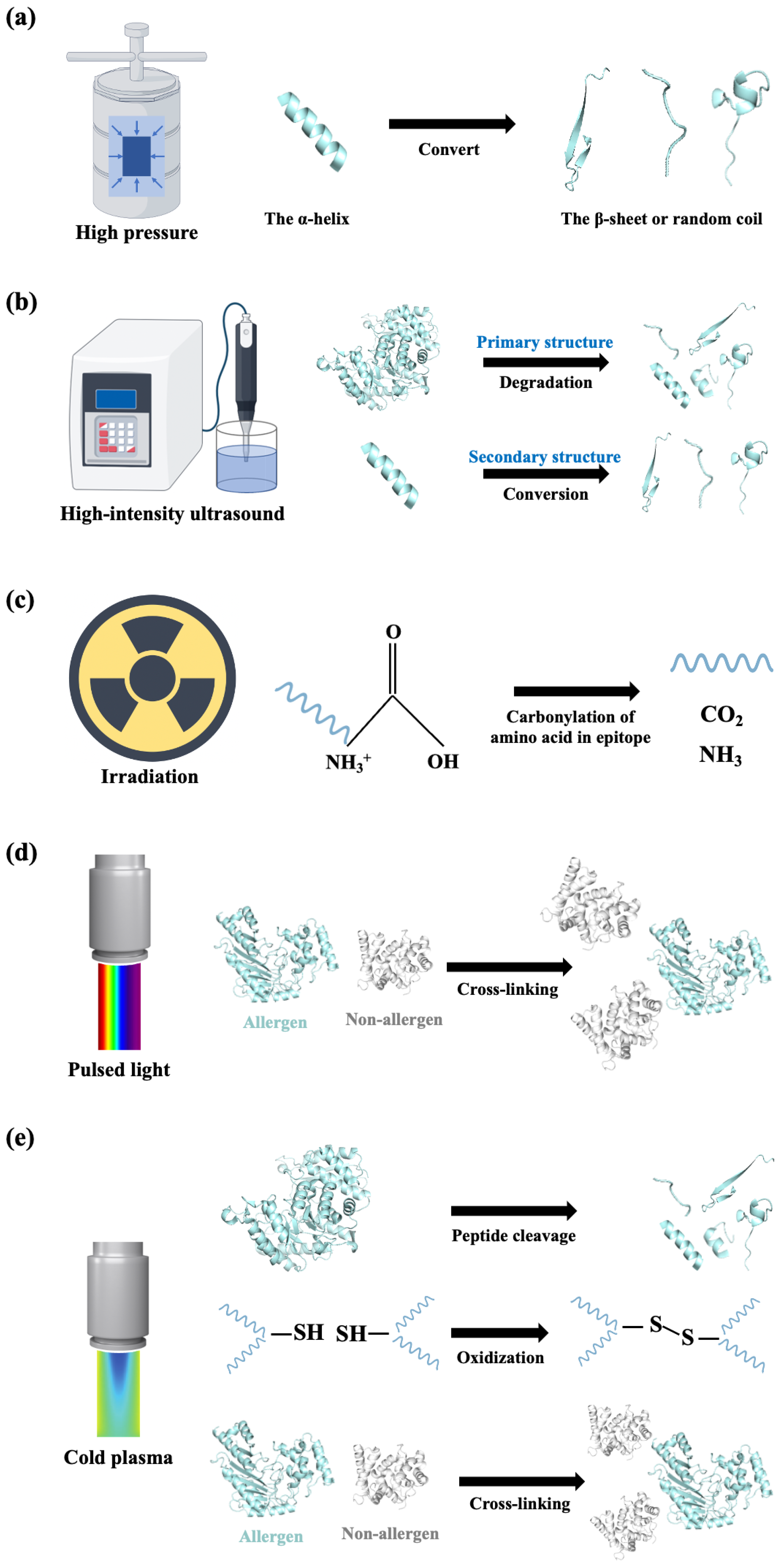

3.1. Processing Techniques Based on Physics

3.1.1. Thermal Treatment

3.1.2. Non-Thermal Treatment

3.2. Processing Techniques Based on Chemistry

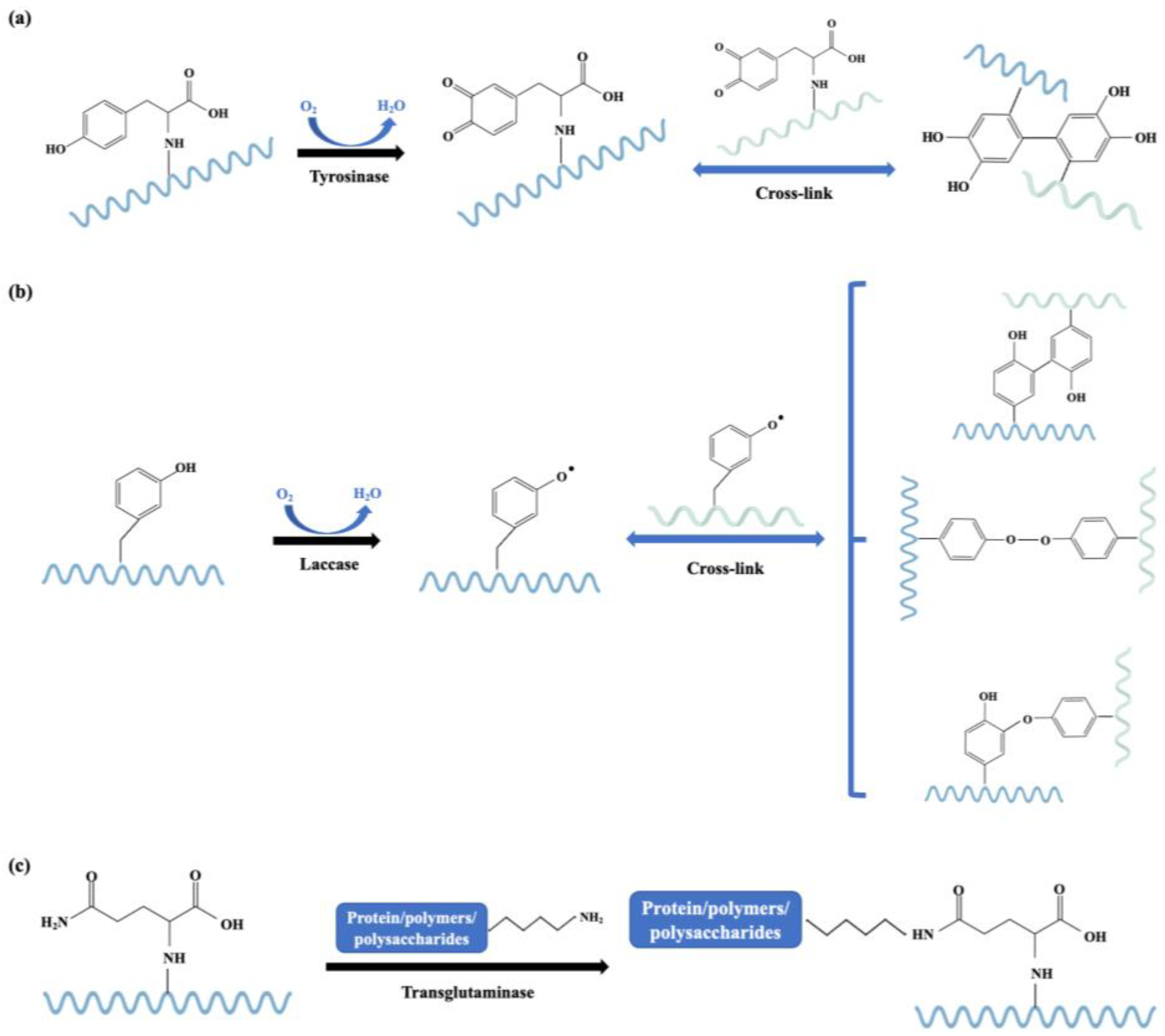

3.2.1. Enzymatic-Catalyzed Cross-Linking

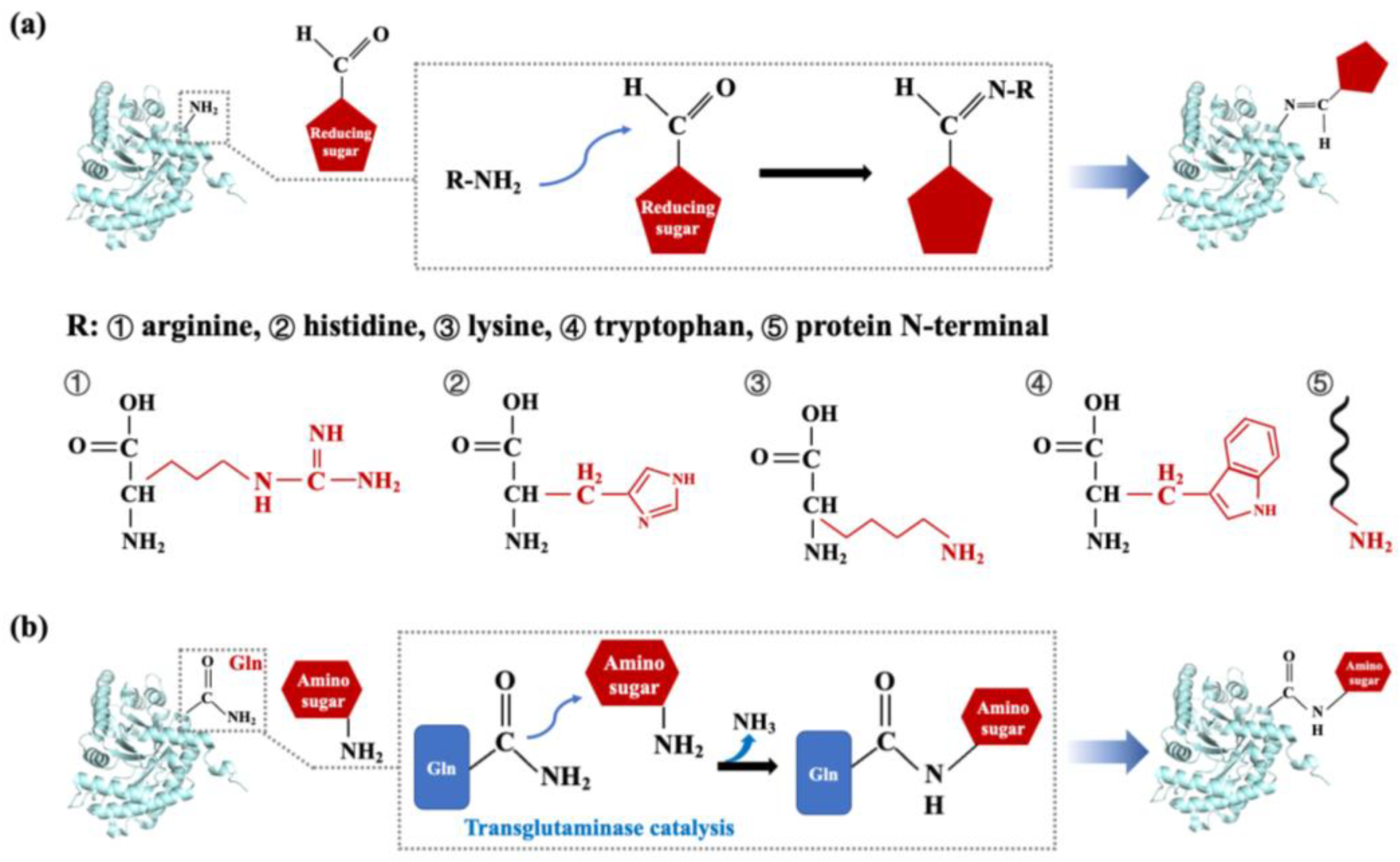

3.2.2. Glycation Modification

3.3. Processing Techniques Based on Biology

3.3.1. Enzymatic Hydrolysis

3.3.2. Fermentation Treatment

3.4. Combination Processing

4. Challenge and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WHO/IUIS | World Health Organization and International Union of Immunological Societies |

| MW | Molecular weight |

| PDB | Protein data bank |

References

- Frischmeyer-Guerrerio, P. A.; Young, F. D.; Aktas, O. N.; Haque, T. Insights into the clinical, immunologic, and genetic underpinnings of food allergy. Immunol Rev 2024, 326, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartha, I.; Almulhem, N.; Santos, A. F. Feast for thought: A comprehensive review of food allergy 2021-2023. J Allergy Clin Immun 2024, 153, 576–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO/WHO. Summary report of the Ad hoc Joint FAO/WHO Expert Consultation on Risk Assessment of Food Allergens. Part 1: Review and validation of Codex priority allergen list through risk assessment.; 2022. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/cb4653en/cb4653en.pdf.

- Kamath, S. D.; Bublin, M.; Kitamura, K.; et al. Cross-reactive epitopes and their role in food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immun 2023, 151, 1178–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvasnicka, J.; Stylianou, K. S.; Nguyen, V. K.; et al. Human Health Benefits from Fish Consumption vs. Risks from inhalation exposures associated with contaminated sediment remediation: Dredging of the Hudson river. Environ Health Perspect 2019, 127, 127004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wai, C. Y. Y.; Leung, N. Y. H.; Chu, K. H.; et al. Overcoming shellfish allergy: How far have we come? Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spolidoro, G. C. I.; Ali, M. M.; Amera, Y. T.; et al. Prevalence estimates of eight big food allergies in Europe: Updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy 2023, 78, 2361–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R. S.; Warren, C. M.; Smith, B. M.; et al. Prevalence and severity of food allergies among US adults. JAMA Netw Open 2019, 2, e185630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, C. M.; Gupta, R. S.; Aktas, O. N.; et al. Clinical management of seafood allergy. J Allergy Cl Imm-Pract 2020, 8, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wai, C. Y. Y.; Leung, N. Y. H.; Leung, A. S. Y.; et al. Seafood allergy in Asia: Geographical Specificity and beyond. Front Allergy 2021, 2, 676903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Zhou, J.; Lu, Y.; et al. Prevalence of self-reported food allergy among adults in Jiangxi, China. World Allergy Organ J 2023, 16, 100773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T. T. K.; Tran, T. T. B.; Ho, H. T. M.; et al. The predominance of seafood allergy in Vietnamese adults: Results from the first population-based questionnaire survey. World Allergy Organ J 2020, 13, 100102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leung, A. S. Y.; Wai, C. Y. Y.; Leung, N. Y. H.; et al. Real-world sensitization and tolerance pattern toseafood in fish-allergic individuals. J Allergy Cl Imm-Prac 2024, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Zotova, V.; Clarke, A. E.; Chan, E. S.; et al. Low resolution rates of seafood allergy. J Allergy Cl Imm-Prac 2019, 7, 690–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudharson, S.; Kalic, T.; Hafner, C.; Breiteneder, H. Newly defined allergens in the WHO/IUIS Allergen Nomenclature Database during 01/2019-03/2021. Allergy 2021, 76, 3359–3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruethers, T.; Taki, A. C.; Karnaneedi, S.; et al. Expanding the allergen repertoire of salmon and catfish. Allergy 2021, 76, 1443–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L. L.; Wang, C.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y. Seafood allergy: Occurrence, mechanisms and measures. Trends Food Sci Tech 2019, 88, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y. T.; Lu, Y. Y.; Huang, Y. H.; et al. Insight analysis of the cross-sensitization of multiple fish parvalbumins via the Th1/Th2 immunological balance and cytokine release from the perspective of safe consumption of fish. Food Qual Saf-Oxford 2022, 6, fyac056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. H.; Li, Z. X.; Wu, Y. T.; et al. Comparative analysis of allergenicity and predicted linear epitopes in α and β parvalbumin from turbot (Scophthalmus maximus). J Sci Food Agr 2023, 103, 2313–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R. Q.; Chen, Y. L.; Chen, F.; et al. Purification, characterization, and crystal structure of parvalbumins, the major allergens in Mustelus griseus. J Agric Food Chem 2018, 66, 8150–8159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Gordo, M.; Pastor-Vargas, C.; Lin, J.; et al. Epitope mapping of the major allergen from Atlantic cod in Spanish population reveals different IgE-binding patterns. Mol Nutr Food Res 2013, 57, 1283–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Amparano, M. B.; Huerta-Ocampo, J. A.; Pastor-Palacios, G.; Teran, L. M. The Role of enolases in allergic disease. J Allergy Cl Imm-Prac 2021, 9, 3026–3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuehn, A.; Hilger, C.; Lehners-Weber, C.; et al. Identification of enolases and aldolases as important fish allergens in cod, salmon and tuna: component resolved diagnosis using parvalbumin and the new allergens. Clin Exp Allergy 2013, 43, 811–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wai, C. Y. Y.; Leung, N. Y. H.; Leung, A. S. Y.; et al. Differential patterns of fish sensitization in Asian populations: Implication for precision diagnosis. Allergol Int 2023, 72, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sariyer, E.; Yakarsonmez, S.; Danis, O.; et al. A study of Bos taurus muscle specific enolase; biochemical characterization, homology modelling and investigation of molecular interaction using molecular docking and dynamics simulations. Int J Biol Macromol 2018, 120 Pt B, 2346–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, R.; Satoh, R.; Nakajima, Y.; et al. Comparative study of GH-transgenic and non-transgenic amago salmon (Oncorhynchus masou ishikawae) allergenicity and proteomic analysis of amago salmon allergens. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 2009, 55, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruethers, T.; Taki, A. C.; Nugraha, R.; et al. Variability of allergens in commercial fish extracts for skin prick testing. Allergy 2019, 74, 1352–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, L. E.; Bosch, J. Structure of Toxoplasma gondii fructose-1,6-bisphosphate aldolase. Acta Crystallogr F Struct Biol Commun 2014, 70 Pt 9, 1186–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Holck, A. L.; Yang, E.; et al. Tropomyosin from tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus) as an allergen. Clin Exp Allergy 2013, 43, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M. S.; Xia, F.; Liu, Q. M.; et al. Identification and allergenicity analysis of tropomyosin: A heat-stable allergen in Lateolabrax japonicus. J Agric Food Chem 2024, 73, 822–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitby, F. G.; Phillips, G. N. Crystal structure of tropomyosin at 7 Angstroms resolution. Proteins 2000, 38, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J. H.; Wang, H.; Sun, D. W. An overview of tropomyosin as an important seafood allergen: Structure, cross-reactivity, epitopes, allergenicity, and processing modifications. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2022, 21, 127–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, L.; Zhang, X. M.; Wen, Y. Q.; et al. Comparison of tropomyosin released peptide and epitope mapping after in vitro digestion from fish (Larimichthys crocea), shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) and clam (Ruditapes philippinarum) through SWATH-MS based proteomics. Food Chem 2023, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamada, Y.; Nagashima, Y.; Shiomi, K. Identification of collagen as a new fish allergen. Biosci Biotech Bioch 2001, 65, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, Y.; Akiyama, H.; Huge, J.; et al. Fish collagen is an important panallergen in the Japanese population. Allergy 2016, 71, 720–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimojo, N.; Yagami, A.; Ohno, F.; et al. Fish collagen as a potential indicator of severe allergic reactions among patients with fish allergies. Clin Exp Allerg 2022, 52, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bella, J. Collagen structure: new tricks from a very old dog. Biochem J 2016, 473, 1001–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudko, S. P.; Bachinger, H. P. Structural insight for chain selection and stagger control in collagen. Sci Rep-UK 2016, 6, 37831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalic, T.; Kamath, S. D.; Ruethers, T.; et al. Collagen-an important fish allergen for improved diagnosis. J Allergy Cl Imm-Prac 2020, 8, 3084–3092 e3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde-Monge, M.; Pastor-Vargas, C.; Rodriguez Del Rio, P.; et al. Anaphylaxis by exclusive allergy to swordfish and identification of a new fish allergen. Pediat Allerg Imm-UK 2018, 29, 563–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, F.; Li, M. S.; Liu, Q. M.; et al. Crystal structure analysis and conformational epitope mutation of triosephosphate isomerase, a mud crab allergen. J Agric Food Chem 2019, 67, 12918–12926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larco-Rojas, X.; Gonzalez-Gutierrez, M. L.; Vazquez-Cortes, S.; et al. Occupational asthma and urticaria in a fishmonger due to creatine kinase, a cross-reactive fish allergen. J Invest Allerg Clin 2017, 27, 386–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; He, X. R.; Huan, F.; et al. A Crystal structure of Pro c 2 provides insights into cross-reactivity of aquatic allergens from the phosphagen kinase family. J Agric Food Chem 2024, 72, 28400–28411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanaoka, K.; Takahagi, S.; Ishii, K.; et al. Type-I-hypersensitivity to 15 kDa, 28 kDa and 54 kDa proteins in vitellogenin specific to Gadus chalcogrammus roe. Allergol Int 2020, 69, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, D. R.; Day, E. D., Jr.; Miller, J. S. The major heat stable allergen of shrimp. Ann Allergy 1981, 47, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Nugraha, R.; Kamath, S. D.; Johnston, E.; et al. Conservation analysis of B-cell allergen epitopes to predict clinical cross-reactivity between shellfish and inhalant invertebrate allergens. Front Immunol 2019, 10, 2676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B. J.; He, H.; Wang, X.; et al. Research progress on shrimp allergens and allergenicity reduction methods. Foods 2025, 14, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, J. K.; Pike, D. H.; Khan, I. J.; et al. Structural and dynamic properties of allergen and non-allergen forms of tropomyosin. Structure 2018, 26, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Huan, F.; Li, M. S.; et al. Mapping and IgE-binding capacity analysis of heat/digested stable epitopes of mud crab allergens. Food Chem 2021, 344, 128735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L. T.; Wei, F. L.; Liu, L.; et al. Study on the allergenicity of tropomyosin from different aquatic products based on conformational and linear epitopes analysis. J Agric Food Chem 2025, 73, 4936–4946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M. S.; Xia, F.; Liu, Q. M; et al. IgE Epitope analysis for Scy p 1 and Scy p 3, the heat-stable myofibrillar allergens in mud crab. J Agric Food Chem 2022, 12189–12202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C. J.; Lin, Y. F.; Chiang, B. L.; et al. Proteomics and immunological analysis of a novel shrimp allergen, Pen m 2. J Immunol 2003, 170, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Liu, G. Y.; Yang, H.; et al. Crystal structure determination of Scylla paramamosain arginine kinase, an allergen that may cause cross-reactivity among invertebrates. Food Chem 2019, 271, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Cao, M. J.; Alcocer, M.; et al. Mapping and characterization of antigenic epitopes of arginine kinase of Scylla paramamosain. Mol Immunol 2015, 65, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H. L.; Mao, H. Y.; Cao, M. J.; et al. Purification, physicochemical and immunological characterization of arginine kinase, an allergen of crayfish (Procambarus clarkii). Food Chem Toxicol 2013, 62, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H. Y.; Cao, M. J.; Maleki, S. J.; et al. Structural characterization and IgE epitope analysis of arginine kinase from Scylla paramamosain. Mol Immunol 2013, 56, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Gao, X.; Lin, H.; et al. Identification and amino acid analysis of allergenic epitopes of a novel allergen paramyosin (Rap v 2) from Rapana venosa. J Agric Food Chem 2021, 69, 5381–5391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Ding, X.; Gao, X.; et al. Immunological cross-reactivity involving mollusc species and mite-mollusc and cross-reactive allergen PM are risk factors of mollusc allergy. J Agric Food Chem 2022, 70, 360–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Gao, X.; Lin, H.; et al. Purification, characterization, and three-dimensional structure prediction of paramyosin, a novel allergen of Rapana venosa. J Agric Food Chem 2020, 68, 14632–14642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. T.; Gourinath, S.; Kovacs, M.; et al. Rigor-like structures from muscle myosins reveal key mechanical elements in the transduction pathways of this allosteric motor. Structure 2007, 15, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, A.; Alqassir, N.; Breda, D.; et al. Serological proteome analysis identifies crustacean myosin heavy chain type 1 protein and house dust mite Der p 14 as cross-reacting allergens. Adv Clin Exp Med 2023, 32, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saenz de San Pedro, B.; Lopez Guerrero, A.; Navarrete del Pino, M. A.; et al. Myosin heavy chain: An allergen involved in anaphylaxis to shrimp head. J Invest Allerg Clin 2023, 33, 66–68. [Google Scholar]

- Shibata, Y.; Satoshi, S.; Oishi, T.; et al. Myosin heavy chain, a novel allergen for fish allergy in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol 2019, 139, S223–S223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayuso, R.; Grishina, G.; Bardina, L.; et al. Myosin light chain is a novel shrimp allergen, Lit v 3. J Allergy Clin Immun 2008, 122, 795–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A. M. A.; Kamath, S.; Lopata, A. L.; et al. Analysis of the allergenic proteins in black tiger prawn (Penaeus monodon) and characterization of the major allergen tropomyosin using mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Sp 2010, 24, 2462–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauermeister, K.; Wangorsch, A.; Garoffo, L. P.; et al. Generation of a comprehensive panel of crustacean allergens from the North Sea Shrimp Crangon crangon. Mol Immunol 2011, 48, 1983–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M. S.; Xia, F.; Liu, M.; et al. Cloning, expression, and epitope identification of myosin light chain 1: An allergen in mud crab. J Agric Food Chem 2019, 67, 10458–10469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yan, H. F.; Zhang, Y. X.; et al. Expression and epitope identification of myosin light chain isoform 1, an allergen in Procambarus clarkii. Food Chem 2020, 317, 126422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. X.; Chen, H. L.; Maleki, S. J.; et al. Purification, characterization, and analysis of the allergenic properties of myosin light chain in Procambarus clarkii. J Agric Food Chem 2015, 63, 6271–6282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayuso, R.; Grishina, G.; Dolores Ibanez, M.; et al. Sarcoplasmic calcium-binding protein is an EF-hand-type protein identified as a new shrimp allergen. J Allergy Clin Immun 2009, 124, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T. J.; Huan, F.; Liu, M.; et al. IgE epitope analysis of sarcoplasmic-calcium-binding protein, a heat-resistant allergen in Crassostrea angulata. Food Funct 2021, 12, 8570–8582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M. J.; Liu, G. Y.; Yang, Y.; et al. Cloning, expression, and the effects of processing on sarcoplasmic calcium-binding protein: an important allergen in mud crab. J Agric Food Chem 2017, 65, 6247–6257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y. Y.; Jin, T.; Li, M. S.; et al. Crystal structure analysis of sarcoplasmic-calcium-binding protein: an allergen in Scylla paramamosain. J Agric Food Chem 2023, 71, 1214–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y. X.; Liu, M.; et al. Triosephosphate isomerase and filamin C share common epitopes as novel allergens of Procambarus clarkii. J Agric Food Chem 2017, 65, 950–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, F.; Li, M. S.; Liu, Q. M.; et al. Allergenicity and linear epitope analysis of Scy p 8, an allergen from mud crab. J Agric Food Chem 2024, 72, 13402–13414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X. R.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Y. X.; et al. Immunoglobulin E epitope mapping and structure-allergenicity relationship analysis of crab allergen Scy p 9. J Agric Food Chem 2023, 71, 17379–17390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X. R.; Yang, Y.; Kang, S.; et al. Crystal structure analysis and ige epitope mapping of allergic predominant region in Scylla paramamosain filamin C, Scy p 9. J Agric Food Chem 2022, 70, 1282–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karnaneedi, S.; Huerlimann, R.; Johnston, E. B.; et al. Novel allergen discovery through comprehensive de novo transcriptomic analyses of five shrimp species. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, Y. S.; Yumoto, F.; Tanaka, H.; et al. Structure of the Ca2+-saturated C-terminal domain of scallop troponin C in complex with a troponin I fragment. Biological Chemistry 2013, 394, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffrida, M. G.; Villalta, D.; Mistrello, G.; et al. Shrimp allergy beyond tropomyosin in Italy: clinical relevance of arginine kinase, sarcoplasmic calcium binding protein and hemocyanin. Eur Ann Allergy Clin 2014, 46, 172–177. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; Luan, H.; Wang, C.; et al. Molecular and allergenic properties of natural hemocyanin from Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis). Food Chem 2023, 424, 136422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S.; et al. The effect of immunotherapy on cross-reactivity between house dust mite and other allergens in house dust mite -sensitized patients with allergic rhinitis. Expert Rev Clin Immu 2021, 17, 969–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; She, T.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Identification and characterization of ovary development-related protein EJO1 (Eri s 2) from the ovary of Eriocheir sinensis as a new food allergen. Mol Nutr Food Res 2016, 60, 2275–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munera, M.; Martinez, D.; Wortmann, J.; et al. Structural and allergenic properties of the fatty acid binding protein from shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. Allergy 2022, 77, 1534–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wai, C. Y. Y.; Leung, N. Y. H.; Leung, A. S. Y.; et al. Comprehending the allergen repertoire of shrimp for precision molecular diagnosis of shrimp allergy. Allergy 2022, 77, 3041–3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M. U.; Ahmed, I.; Lin, H.; et al. Potential efficacy of processing technologies for mitigating crustacean allergenicity. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2019, 59, 2807–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosmilah, M.; Shahnaz, M.; Meinir, J.; et al. Identification of parvalbumin and two new thermolabile major allergens of Thunnus tonggol using a proteomics approach. Int Arch Allergy Imm 2013, 162, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, H.; Kobayashi, A.; Kobayashi, Y.; et al. Reduction in IgE reactivity of Pacific mackerel parvalbumin by heat treatment. Food Chem 2016, 206, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Taylor, S. L.; Baumert, J.; et al. Effects of thermal treatment on the immunoreactivity and quantification of parvalbumin from Southern hemisphere fish species with two anti-parvalbumin antibodies. Food Control 2021, 121, 107675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Ventel, M. L.; Nieuwenhuizen, N. E.; Kirstein, F.; et al. Differential responses to natural and recombinant allergens in a murine model of fish allergy. Mol Immunol 2011, 48, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. T.; Hsieh, Y. H. P. Characterization of a 36 kDa antigenic protein of fish-specific monoclonal-antibody 8F5. Food Chem 2022, 379, 132149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Li, G. M.; Zhang, J. T.; et al. Identification and mutational analysis of continuous, immunodominant epitopes of the major oyster allergen Crag 1. Clin Immunol 2019, 201, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J. L.; Li, Y. H.; Xu, L. L.; et al. Thermal induced the structural alterations, increased IgG/IgE binding capacity and reduced immunodetection recovery of tropomyosin from shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). Food Chem 2022, 391, 133215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J. L; Zhu, W. Y.; Zeng, J. H.; et al. Insight into the mechanism of allergenicity decreasing in recombinant sarcoplasmic calcium-binding protein from shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) with thermal processing via spectroscopy and molecular dynamics simulation techniques. Food Res Int 2022, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabanillas, B.; Novak, N. Effects of daily food processing on allergenicity. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2019, 59, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekezie, F. G. C.; Cheng, J. H.; Sun, D. W. Effects of nonthermal food processing technologies on food allergens: A review of recent research advances. Trends Food Sci Tech 2018, 74, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y. F.; Deng, Y.; Qian, B. J.; et al. Allergenic response to squid (Todarodes pacificus) tropomyosin Tod p1 structure modifications induced by high hydrostatic pressure. Food Chem Toxicol 2015, 76, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrera, M.; Fidalgo, L. G.; Saraiva, J. A.; et al. Effects of high-pressure treatment on the muscle proteome of hake by bottom-up proteomics. J Agric Food Chem 2018, 66, 4559–4570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. E.; Liao, H. Q.; Lu, Y. B.; et al. Effects of high hydrostatic pressure on the structural characteristics of parvalbumin of cultured large yellow croaker (Larimichthys crocea). J Food Process Pres 2020, 44, e14911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W. Q.; Ma, H. L.; Wang, Y. Y. Recent advances in modified food proteins by high intensity ultrasound for enhancing functionality: Potential mechanisms, combination with other methods, equipment innovations and future directions. Ultrason Sonochem 2022, 85, 105993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Y.; Zhang, X. F.; Chen, W.; et al. Conformation stability, in vitro digestibility and allergenicity of tropomyosin from shrimp (Exopalaemon modestus) as affected by high intensity ultrasound. Food Chem 2018, 245, 997–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. X.; Lin, H.; Cao, L. M.; et al. Effect of high intensity ultrasound on the allergenicity of shrimp. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B 2006, 7, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanga, S. K.; Singh, A.; Raghavan, V. Review of conventional and novel food processing methods on food allergens. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2017, 57, 2077–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, M. F.; Yang, J. Y.; Liu, K. X.; et al. Irradiation technology: An effective and promising strategy for eliminating food allergens. Food Res Int 2021, 148, 110578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. X.; Lu, Z. C.; Khan, M. N.; et al. Protein carbonylation during electron beam irradiation may be responsible for changes in IgE binding to turbot parvalbumin. Food Chem Toxicol 2014, 69, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, A.; Mei, K.; Lv, M.; et al. The effect of electron beam irradiation on IgG binding capacity and conformation of tropomyosin in shrimp. Food Chemistry 2018, 264, 250–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, M. C.; Mei, K. L.; Zhang, H.; et al. Effects of electron beam irradiation on the biochemical properties and structure of myofibrillar protein from Tegillarca granosa meat. Food Chem 2018, 254, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, F.; Pizarro-Oteiza, S.; Kasahara, I.; et al. Effect of pulsed ultraviolet light on the degree of antigenicity and hydrolysis in cow's milk proteins. J Food Process Eng 2024, 47, e14629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Kumar, Y.; Singh, V.; et al. Cold plasma technology: Reshaping food preservation and safety. Food Control 2024, 163, 110537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekezie, F. G. C.; Sun, D. W.; Cheng, J. H. Altering the IgE binding capacity of king prawn (Litopenaeus vannamei) tropomyosin through conformational changes induced by cold argon-plasma jet. Food Chem 2019, 300, 125143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, C. Y.; Wu, G. Q.; Bu, Y.; et al. Effect of transglutaminase cross-linking on debittering of Alaska pollock frame hydrolysate. Int J Food Sci Tech 2024, 59, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Wang, Q.; Yi, H.; et al. Recent insights in cow's milk protein allergy: Clinical relevance, allergen features, and influences of food processing. Trends Food Sci Tech 2025, 156, 104830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; Lin, H.; Xu, L.; et al. Immunomodulatory effect of laccase/caffeic acid and transglutaminase in alleviating shrimp tropomyosin (Met e 1) allergenicity. J Agric Food Chem 2020, 68, 7765–7778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fei, D. X.; Liu, Q. M.; Chen, F.; et al. Assessment of the sensitizing capacity and allergenicity of enzymatic cross-linked arginine kinase, the crab allergen. Mol Nutr Food Res 2016, 60, 1707–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G. Y.; Hu, M. J.; Sun, L. C.; et al. Allergenicity and oral tolerance of enzymatic cross-linked tropomyosin evaluated using cell and mouse models. J Agric Food Chem 2017, 65, 2205–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; Lin, H.; Li, Z. X.; et al. Tyrosinase/caffeic acid cross-linking alleviated shrimp (Metapenaeus ensis) tropomyosin-induced allergic responses by modulating the Th1/Th2 immunobalance. Food Chem 2021, 340, 127948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, S. L.; Ma, J. J.; Ahmed, I.; et al. Effect of tyrosinase-catalyzed crosslinking on the structure and allergenicity of turbot parvalbumin mediated by caffeic acid. J Sci Food Agri 2019, 99, 3501–3508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. Y.; Lu, F. P.; Liu, Y. H. A Review of the mechanism, properties, and applications of hydrogels prepared by enzymatic cross-linking. J Agric Food Chem 2023, 71, 10238–10249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasic, K.; Knez, Z.; Leitgeb, M. Transglutaminase in foods and biotechnology. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 12402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ahmed, I.; Zhao, Z. X.; et al. A comprehensive review on glycation and its potential application to reduce food allergenicity. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2024, 64, 12184–12206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X. Y.; Yang, H.; Rao, S. T.; et al. The Maillard reaction reduced the sensitization of tropomyosin and arginine kinase from Scylla paramamosain, Simultaneously. J Agric Food Chem 2018, 66, 2934–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Y.; Xiao, H.; Zhang, X. F.; et al. Insight into the effects of deglycosylation and glycation of shrimp tropomyosin on in vivo allergenicity and mast cell function. Food Funct 2019, 10, 3934–3941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L. T.; Ahmed, I.; Qu, X.; et al. Effect of the structure and potential allergenicity of glycated tropomyosin, the shrimp allergen. Int J Food Sci Tech 2022, 57, 1782–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Wang, J.; Xu, L.; et al. Insights into the mechanism underlying the influence of glycation with different saccharides and temperatures on the IgG/IgE binding ability, immunodetection, in vitro digestibility of shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) tropomyosin. Foods 2023, 12, 3049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, H. W.; Liu, Y. Y.; Chen, F.; et al. Purification, characterization and immunoreactivity of tropomyosin, the allergen in Octopus fangsiao. Process Biochem 2014, 49, 1747–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, T. L.; Han, X. Y.; Li, M. S.; et al. Effects of the Maillard reaction on the epitopes and immunoreactivity of tropomyosin, a major allergen in Chlamys nobilis. Food Funct 2021, 12, 5096–5108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, N. R.; Yu, C. C.; Han, X. Y.; et al. Effects of three processing technologies on the structure and immunoreactivity of α-tropomyosin from Haliotis discus hannai. Food Chem 2023, 405, 134947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y. T.; Lu, Y. Y.; Huang, Y. H.; et al. Glycosylation reduces the allergenicity of turbot (Scophthalmus maximus) parvalbumin by regulating digestibility, cellular mediators release and Th1/Th2 immunobalance. Food Chem 2022, 382, 132574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; Chen, H.; Li, J. L.; et al. Enzymatic crosslinking and food allergenicity: A comprehensive review. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2021, 20, 5856–5879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, F. Z.; Lv, L. T.; Li, Z. X.; et al. Effect of transglutaminase-catalyzed glycosylation on the allergenicity and conformational structure of shrimp (Metapenaeus ensis) tropomyosin. Food Chem 2017, 219, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D. X.; He, X. R.; Li, F. J.; et al. Effect of transglutaminase-catalyzed glycosylation on the allergenicity of tropomyosin in the Perna viridis food matrix. Food Funct 2024, 15, 9136–9148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunal-Koroglu, D.; Karabulut, G.; Ozkan, G.; et al. Allergenicity of alternative proteins: Reduction mechanisms and processing strategies. J Agric Food Chem 2025, 73, 7522–7546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-Salam, M. H.; El-Shibiny, S. Reduction of Milk protein antigenicity by enzymatic hydrolysis and fermentation. A review. Food Rev Int 2021, 37, 276–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Untersmayr, E.; Poulsen, L. K.; Platzer, M. H.; et al. The effects of gastric digestion on codfish allergenicity. J Allergy Clin Immu 2005, 115, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G. M.; Huang, Y. Y.; Cai, Q. F.; et al. Comparative study of in vitro digestibility of major allergen, tropomyosin and other proteins between Grass prawn (Penaeus monodon) and Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei). J Sci Food Agric 2011, 91, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamez, C.; Paz Zafra, M.; Sanz, V.; et al. Simulated gastrointestinal digestion reduces the allergic reactivity of shrimp extract proteins and tropomyosin. Food Chem 2015, 173, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarz, B.; Rao, Q. C.; Jiang, X. Y.; et al. Immunochemical analysis of pepsin-digested fish tropomyosin. Food Control 2020, 118, 107427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Moreno, P. J.; Perez-Galvez, R.; Javier Espejo-Carpio, F.; et al. Functional, bioactive and antigenicity properties of blue whiting protein hydrolysates: effect of enzymatic treatment and degree of hydrolysis. J Sci Food Agric 2017, 97, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M. X.; Huan, F.; Gao, S.; et al. Preparation of the hypoallergenic enzymatic hydrolyzate of Cra a 4 with the potential to induce immune tolerance. J Agric Food Chem 2025, 73, 4299–4308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, X. W.; Yang, Y. L.; Sun, Y. X; et al. Recent advances in alleviating food allergenicity through fermentation. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2022, 62, 7255–7268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejrhit, N.; Azdad, O.; Aarab, L. Effect of industrial processing on the IgE reactivity of three commonly consumed Moroccan fish species in Fez region. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol 2018, 50, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Zhao, J.; Qin, Z.; et al. Influence of fermentation by Lactobacillus helveticus on the immunoreactivity of Atlantic cod allergens. J Agric Food Chem 2023, 71, 10144–10154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y. D.; Gao, L.; Xie, G. J.; et al. Effect of fermentation on immunological properties of allergens from black carp (Mylopharyngodon piceus) sausages. Int J Food Sci Tech 2020, 55, 3162–3172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalia, U.; Shimizu, Y.; Saeki, H. Variation in shrimp tropomyosin allergenicity during the production of Terasi, an Indonesian fermented shrimp paste. Food Chem 2023, 398, 133876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, F. Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, R. R.; et al. Effects of combined high pressure and thermal treatments on the allergenic potential of shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) tropomyosin in a mouse model of allergy. Innov Food Sci Emerg Tech 2015, 29, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Han, T. J.; Huan, F.; et al. Effects of thermal processing on the allergenicity, structure, and critical epitope amino acids of crab tropomyosin. Food Funct 2021, 12, 2032–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, J. J.; Qiao, D.; Huang, X.; et al. Structural property, immunoreactivity and gastric digestion characteristics of glycated parvalbumin from mandarin fish (Siniperca chuaisi) during microwave-assisted Maillard reaction. Foods 2023, 12, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, S.; Wang, F. Q.; Cheng, J. H.; et al. Mechanism of cold plasma combined with glycation in altering IgE-binding capacity and digestion stability of tropomyosin from shrimp. J Agric Food Chem 2023, 71, 15796–15808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, J. F.; Cabanillas, B. Recent advances in cellular and molecular mechanisms of IgE-mediated food allergy. Food Chem 2023, 411, 135500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; He, X. R.; Li, F. J.; et al. Animal-derived food allergen: A review on the available crystal structure and new insights into structural epitope. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2024, 23, e13340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, J.; Liang, R.; Huang, H.; et al. Maillard reaction induced changes in allergenicity of food. Foods 2022, 11, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q. Z.; Lin, S. Y.; Sun, N. How does food matrix components affect food allergies, food allergens and the detection of food allergens? A systematic review. Trends Food Sci Tech 2022, 127, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Protein | Fish species | Allergen names in IUIS | MW (kDa) |

| β-Parvalbumin | Gadus callarias | Gad c 1 | 12 |

| Gadus morhua | Gad m 1 | 12 | |

| Crocodylus porosus | Cro p 1 | 11.6 | |

| Clupea harengus | Clu h 1 | 12 | |

| Ctenopharyngodon idella | Cten i 1 | 9 | |

| Cyprinus carpio | Cyp c 1 | 12 | |

| Lates calcarifer | Lat c 1 | 11.5 | |

| Lateolabrax maculatus | Late m 1 | 12 and 13 | |

| Lepidorhombus whiffiagonis | Lep w 1 | 11.5 | |

| Oncorhynchus mykiss | Onc m 1 | 12 | |

| Pangasianodon hypophthalmus | Pan h 1 | 11 | |

| Rastrelliger kanagurta | Ras k 1 | 11.3 | |

| Salmo salar | Sal s 1 | 12 | |

| Sardinops sagax | Sar sa 1 | 12 | |

| Scomber scombrus | Sco s 1 | 12 | |

| Sebastes marinus | Seb m 1 | 11 | |

| Solea solea | Sole s 1 | 11~14 | |

| Thunnus albacares | Thu a 1 | 11 | |

| Trichiurus lepturus | Ttic l 1 | 11 | |

| Xiphias gladius | Xip g 1 | 11.5 | |

| α-Parvalbumin | Crocodylus porosus | Cro p 2 | 13 |

| β-Enolase | Gadus morhua | Gad m 2 | 47.3 |

| Cyprinus carpio | Cyp c 2 | 47 | |

| Pangasianodon hypophthalmus | Pan h 2 | 50 | |

| Salmo salar | Sal s 2 | 47.3 | |

| Thunnus albacares | Thu a 2 | 50 | |

| Aldolase A | Gadus morhua | Gad m 3 | 40 |

| Pangasianodon hypophthalmus | Pan h 3 | 40 | |

| Salmo salar | Sal s 3 | 40 | |

| Thunnus albacares | Thu a 3 | 40 | |

| Tropomyosin | Salmo salar | Sal s 4 | 37 |

| Oreochromis mossambicus | Ore m 4 | 33 | |

| Pangasianodon hypophthalmus | Pan h 4 | 35 | |

| β-Prime-component of vitellogenin | Oncorhynchus keta | Onc k 5 | 18 |

| α-Collagen | Lates calcarifer | Lat c 6 | 130~1140 |

| Salmo salar | Sal s 6 | 130~140 | |

| Creatine kinase | Pangasianodon hypophthalmus | Pan h 7 | 43 |

| Salmo salar | Sal s 7 | 43 | |

| Triosephosphate isomerase | Pangasianodon hypophthalmus | Pan h 8 | 25 |

| Salmo salar | Sal s 8 | 25 | |

| Pyruvate kinase PKM-like | Pangasianodon hypophthalmus | Pan h 9 | 65 |

| L-lactate dehydrogenase | Pangasianodon hypophthalmus | Pan h 10 | 34 |

| Glucose 6-phosphate isomerase | Pangasianodon hypophthalmus | Pan h 11 | 60 |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | Pangasianodon hypophthalmus | Pan h 13 | 36 |

| Protein | MW (kDa) | Species | Biological function |

|

| β-Parvalbumin | 11~14 | Fish | Calcium-binding protein |

|

| α-Parvalbumin | ~13 | Fish | Calcium-binding protein |

|

| β-Enolase | 47~50 | Fish | Glycolytic enzyme |

|

| Aldolase A | 40 | Fish | Glycolytic enzyme |

|

| Tropomyosin | 33~40 | Fish Crustacean Mollusk |

Actin-binding protein |

|

| collagen | 130~140 | Fish | Structural protein |

|

| Pyruvate kinase PKM-like | 65 | Fish Crustacean |

A regulation enzyme involved in glycolysis |

|

| Triosephosphate isomerase | 25~28 | Fish Crustacean Mollusk |

A key enzyme involved in glycolysis |

|

| Creatine kinase | 43 | Fish | phosphoryl transfer enzymes |

|

| L-lactate dehydrogenase | 34 | Fish | An enzyme involved in glycolysis | - |

| Glucose 6-phosphate isomerase | 60 | Fish | A housekeeping enzyme of glycolysis and gluconeogenesis | - |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | 36 | Fish | - | - |

| β-Prime-component of vitellogenin | 18 | Fish | - | - |

| Arginine kinase | 38~45 | Crustacean Mollusk |

Phosphoryl transfer enzymes |

|

| Paramyosin | 99 | Mollusk | Actin-binding protein |

|

| Myosin light chain 2 | 18~23 | Crustacean | Actin-binding protein | - |

| Myosin light chain 1 | 17.5~18 | Crustacean |

Actin-binding protein |

|

| Sarcoplasmic calcium binding protein | 20~25 | Fish Crustacean |

Calcium-binding protein |

|

| Filamin C | ~90 | Crustacean | Actin-binding protein |

|

| Troponin C | 16.8~21 | Crustacean | Actin-binding protein |

|

| Troponin I | ~30 | Crustacean | Actin-binding protein | - |

| Hemocyanin | 76 | Crustacean | - |

|

| Ovary development-related protein | 28.2 | Crustacean | - | - |

| Cytoplasmic fatty acid binding protein | 15~20 | Crustacean | Lipid binding protein superfamily |

|

| Glycogen phosphorylase-like protein | 95 | Crustacean | - | - |

| Protein | Shellfish species | Allergen names in IUIS | MW(kDa) |

| Tropomyosin | Charybdis feriatus | Cha f 1 | 34 |

| Crangon crangon | Cra c 1 | ~38 | |

| Crassostrea angulata | Cra a 1 | 38 | |

| Crassostrea gigas | Cra g 1 | 38 | |

| Exopalaemon modestus | Exo m 1 | 38 | |

| Haliotis laevigata x Haliotis rubra | Hal l 1 | 33.4 | |

| Helix aspersa | Hel as 1 | 36 | |

| Homarus americanus | Hom a 1 | 34 | |

| Litopenaeus vannamei | Lit v 1 | 36 | |

| Macrobrachium rosenbergii | Mac r 1 | 37 | |

| Melicertus latisulcatus | Mel l 1 | 38 | |

| Metapenaeus ensis | Met e 1 | 34 | |

| Pandalus borealis | Pan b 1 | 37 | |

| Panulirus stimpsoni | Pan s 1 | 34 | |

| Penaeus aztecus | Pen a 1 | 36 | |

| Penaeus indicus | Pen i 1 | 34 | |

| Penaeus monodon | Pen m 1 | 38 | |

| Portunus pelagicus | Por p 1 | 36 | |

| Procambarus clarkii | Pro c 1 | 36 | |

| Saccostrea glomerata | Sac g 1 | 38 | |

| Scylla paramamosain | Scy p 1 | 38 | |

| Todarodes pacificus | Tod p 1 | 15 | |

| Arginine kinase | Callinectes bellicosus | Cal b 2 | 40 |

| Crassostrea angulata | Cra a 2 | 38~41 | |

| Crangon crangon | Cra c 2 | ~45 | |

| Litopenaeus vannamei | Lit v 2 | 40 | |

| Macrobrachium rosenbergii | Mac r 2 | 40 | |

| Penaeus monodon | Pen m 2 | 40 | |

| Procambarus clarkii | Pro c 2 | 40 | |

| Scylla paramamosain | Scy p 2 | 40 | |

| Ovary development-related protein | Eriocheir sinensis | Eri s 2 | 28.2 |

| Paramyosin | Rapana venosa | Rap v 2 | 99 |

| Myosin light chain 2 | Homarus americanus | Hom a 3 | ~23 |

| Litopenaeus vannamei | Lit v 3 | 20 | |

| Penaeus monodon | Pen m 3 | 20 | |

| Scylla paramamosain | Scy p 3 | 18 | |

| Myosin light chain 1 | Artemia franciscana | Art fr 5 | ~17.5 |

| Crangon crangon | Cra c 5 | ~17.5 | |

| Procambarus clarkii | Pro c 5 | 18 | |

| Sarcoplasmic calcium binding protein | Crangon crangon | Cra c 4 | ~25 |

| Crassostrea angulata | Cra a 4 | 20 | |

| Litopenaeus vannamei | Lit v 4 | 20 | |

| Penaeus monodon | Pen m 4 | 20 | |

| Pontastacus leptodactylus | Pon l 4 | ~24 | |

| Portunus trituberculatus | Por t 4 | 22 | |

| Scylla paramamosain | Scy p 4 | 20 | |

| Troponin C | Crangon crangon | Cra c 6 | ~21 |

| Homarus americanus | Hom a 6 | ~20 | |

| Penaeus monodon | Pen m 6 | 16.8 | |

| Troponin I | Pontastacus leptodactylus | Pon l 7 | ~30 |

| Hemocyanin | Penaeus monodon | Pen m 7 | 76 |

| Triosephosphate isomerase | Archaeopotamobius sibiriensis | Arc s 8 | ~28 |

| Crangon crangon | Cra c 8 | ~28 | |

| Penaeus monodon | Pen m 8 | 27 | |

| Procambarus clarkii | Pro c 8 | 28 | |

| Scylla paramamosain | Scy p 8 | 28 | |

| Filamin C | Scylla paramamosain | Scy p 9 | 90 |

| Cytoplasmic fatty acid binding protein | Litopenaeus vannamei | Lit v 13 | 15 |

| Penaeus monodon | Pen m 13 | 20 | |

| Glycogen phosphorylase-like protein | Penaeus monodon | Pen m 14 | 95 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).