1. Introduction

The health care systems experience, nowadays, an important deficit of human resources, making the achievement of health care quality very challenging, especially in the developing countries. Thus, the strategic management of human resources should use various psychological tools in order to reach stability in various medical specialties, considering the psychological characteristics of the medical students [

1].

Medical students often experience chronic stress during their academic development. Thus, self-esteem, self-efficacy and general attitudes and beliefs are of paramount importance in the process of psychosocial growth and have a marked effect on thoughts, feelings, values, and professional goals [

2]. Furthermore, future career decisions should rely on occupational psychology, as a guarantee for sustainability of the human resources in health care systems, worldwide [

3]. This regard, the perception of self-esteem, self-efficacy and general attitudes and beliefs among medical students, serve as tools for occupational psychology in the field [

4].

The integration of organizational psychology into the training of medical students is essential for the sustainable development of human resources in the health field. This approach contributes to preparing the future doctors for professional challenges and promoting an efficient work environment.

Self-esteem refers to the totality of the value judgments of an individual regarding his own person. Both very low self-esteem and very high self-esteem can lead to psychological problems. Thus, the self-esteem should be at an average level. Self-efficacy refers to the beliefs of an individual about his or her ability to mobilize his or her cognitive, behavioral and motivational resources to successfully complete a task, respectively, to his/her ability to organize and execute purposeful actions. People with a high level of self-efficacy optimally allocate their resources to solve tasks successfully, whereas people with a low level of self-efficacy avoid initiating actions, withdraw from tasks, fail, and reinforce their beliefs about their incompetence in the respective tasks.

The general attitudes and beliefs refer to four dimensions: achievement, approval, comfort, and justice. With respect to cognition, it measures the global assessment of one's own person and the global assessment of the value of others, rationality, and preferences considering the choice of students with regard to the medical specialty.

Given that medical students experience high levels of stress and are at increased risk of psychological disturbances during the learning process, self-esteem and self-efficacy may be important variables in their well-being and performance [

5].

In the literature, self-esteem and self-efficacy have been associated with academic performance and job satisfaction. Recent studies have shown that these variables are interconnected and influence the perceptions and career choices of medical students [

6,

7].

Social perfectionism, defined by the need to meet the expectations of others, as a part of general attitudes and beliefs, can negatively affect academic self-efficacy and lead to academic burnout [

8,

9]. Educational interventions that support competence, learning from mistakes, and self-efficacy can reduce these negative effects [

10].

Using four well-established questionnaires, which quantify the self-efficacy [

11], the self-esteem [

12], the general attitudes and beliefs [

13], and the perception of medical career specialty [

14], this study aimed to: (1) compare differences in self-esteem, self-efficacy, general attitudes and belief scores with respect to the career preferences of medical students; (2) correlate self-esteem, self-efficacy, general beliefs and attitudes scores, and career-related perceptions among medical students; and (3) identify how these variables influence the career preparation and orientation of the students at different stages of their academic training.

2. Materials and Methods

This research consists in a monocentric observational study that includes medical students from Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest-Romania, which were interviewed between March and July 2024. We enrolled 157 participants (118 females, 39 males). The mean age was 21.6 years (+/- 2.16). They were asked to answer a survey consisting of 4 scales: the Self-Efficacy Scale (SES) (10 items) [

11], the Self-Esteem Scale (SS) (10 items) [

12], the General Attitudes and Beliefs Scale (GABS-SV) (26 items) [

13], and the Perception of Medical Career Specialty Questionnaire (PMCS) (24 items) [

14].

Table 1 reveals the main items included in each scale.

The data were analyzed via GraphPad Prism 6.00 (GraphPad Software Inc.). For the comparative analysis, we used one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey's test for interactions between groups. With respect to career perception, we divided the students into 4 groups: surgery (students who might choose a surgical field after graduation), non-surgery (students who might choose a medical field, nonsurgical field after graduation), paraclinical (students who might choose a medical field with no patient contact after graduation), and N/A (students who did not decide about a specific field after graduation) and compared the main scores among them.

Considering the study year, we divided the students into two groups, namely, the preclinical group (students in the first two years of medical study) and the clinical group (students in the last four years of medical study), in accordance with the curricula of the general medicine studies, and compared various items between them. The data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. A two-sided P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. For binary data, we used the chi-square test.

For the correlative data, we used a correlative matrix that included all the items independently. The Spearman correlation coefficient, r, was determined, considering the non-normality distribution of the group. We considered a two-sided P value <0.05 to indicate statistical significance for each correlation. We assigned r values under 0.4 to have negligible correlative effects. Finally, we excluded nonsignificant correlations.

3. Results

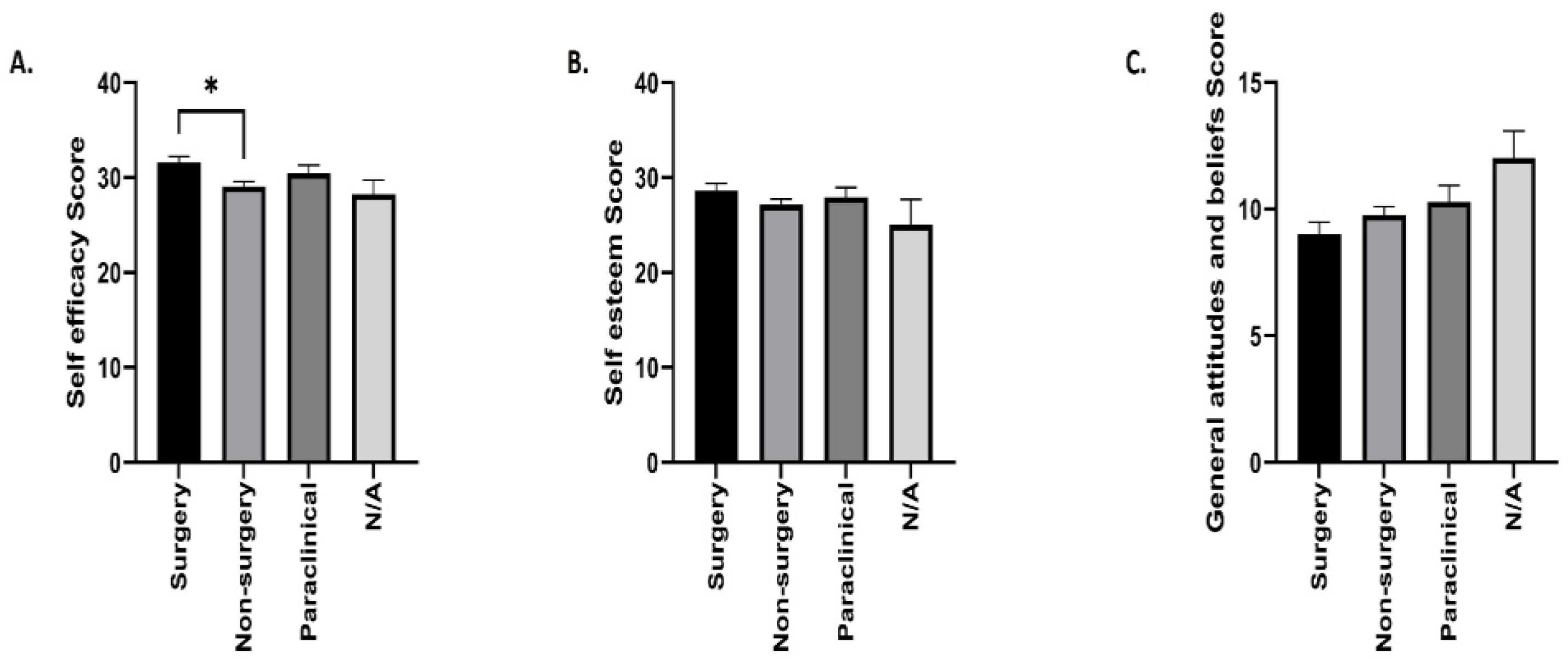

Figure 1 shows the comparative analyses of self-esteem, self-efficacy and general attitudes and beliefs scores with respect to career perception. We observed relatively homogenous score values among the groups regardless of the career perception.

Considering the self-efficacy score, we observed the following mean values among the groups: surgery group vs. non-surgery group, 31.58±0.67 vs. 29.05±0.52 (p=0.018); paraclinical group, 30.48±0.82; and N/A group, 28.25±1.48, without any other statistically significant changes (

Figure 1A). The mean self-esteem score with respect to career perception did not differ significantly among the groups: 28.6±0.79 in the surgery group, 27.16±0.56 in the non-surgery group, 27.9±1.08 in the paraclinical group, and 25±2.67 in the N/A group (

Figure 1B). Furthermore, we revealed relative homogeneity among the groups in terms of the general attitudes and beliefs score: 9±0.49 in the surgery group, 9.77±0.33 in the non-surgery group, 10.29±0.65 in the paraclinical group, and 12±1.08 in the N/A group (

Figure 1C).

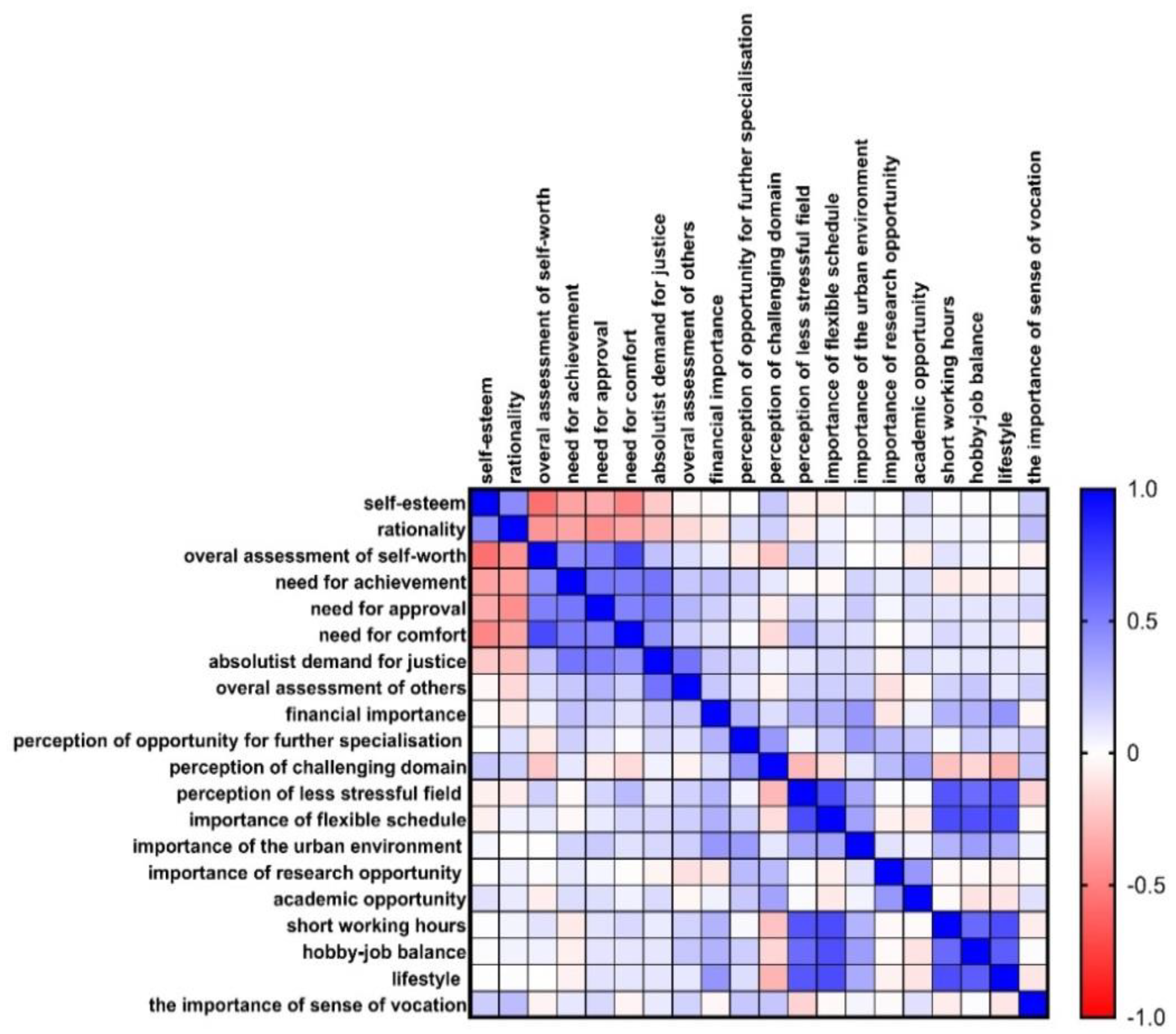

The correlations between self-esteem, self-efficacy, individual general beliefs and attitudes, and career-related perceptions among medical students are shown in

Figure 2. The positive correlations are marked in blue, whereas the negative correlations are red.

Self-esteem correlated positively with rationality (r=0.51, p˂0.001) and negatively with the overall assessment of self-worth (r=-0.56, p˂0.001) and the need for comfort (r=-0.48, p˂0.001). The rationality correlates negatively with the need for approval (r=-0.44, p˂0.001). Additionally, the link between the overall assessment of self-worth and the need for comfort suggests a strong positive correlation (r=0.71, p˂0.001). Moreover, the need for achievement correlates positively with the need for approval (r=0.53, p˂0.001), comfort (r=0.51, p˂0.001) and absolutist demand for justice (r=0.54, p˂0.001). We also observed a positive correlation between the need for approval in student perception and the need for comfort (r=0.48, p˂0.001) and absolutist demand for justice (r=0.51, p˂0.001). The need for comfort also positively correlates with the absolutist demand for justice (r=0.42, p˂0.001), which, further, correlates positively with the overall assessment of others (r=0.54, p˂0.001). We revealed a weak positive correlation between financial importance and lifestyle (r=0.41, p˂0.001) and between perceptions of opportunity for further specialization and perceptions of the challenging domain (r=0.41, p˂0.001).

The perception of a less stressful field strongly correlates with the importance of a flexible schedule (r=0.7, p˂0.001), short working hours (r=0.66, p˂0.001), hobby-job balance (r=0.57, p˂0.001), and lifestyle (r=0.65, p˂0.001). Furthermore, we observed positive correlations between the importance of a flexible schedule and short working hours (r=0.7, p˂0.001), hobby-job balance (0.68, p˂0.001), and lifestyle (r=0.69, p˂0.001), between short working hours and hobby-job balance (r=0.58, p˂0.001) and lifestyle (r=0.69, p˂0.001), and between hobby-job balance and lifestyle (r=0.63, p˂0.001).

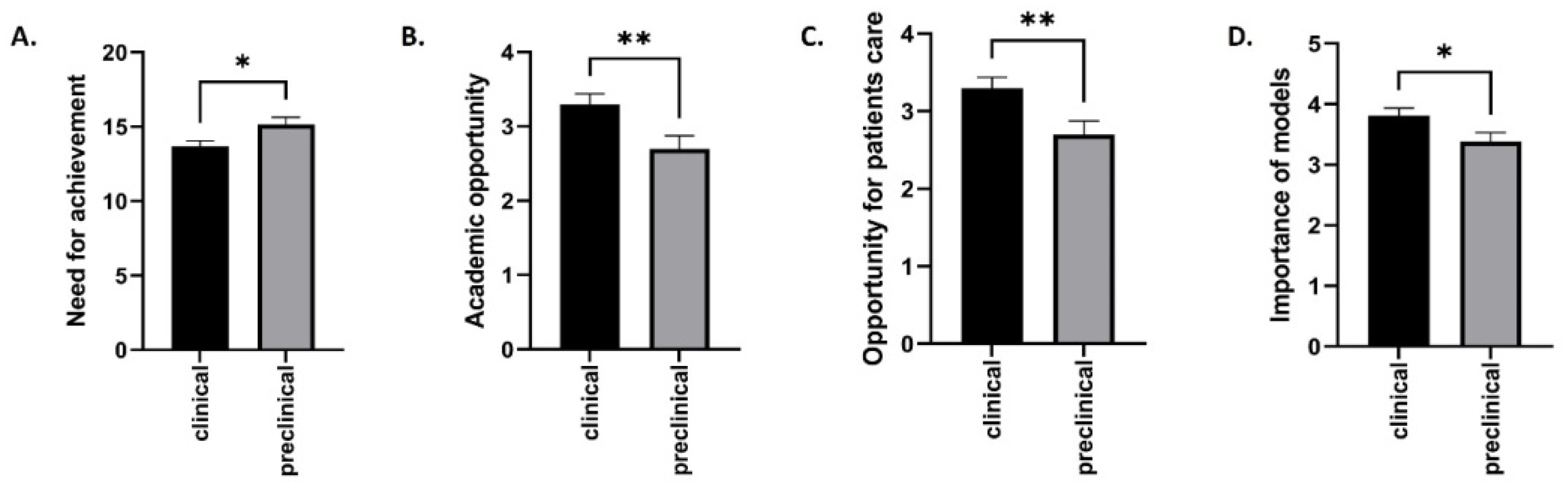

The comparative analyses between the years of study and the need for achievement, academic opportunity, opportunity for patient care, and importance of the models are shown in

Figure 3.

Our study revealed a significantly greater score for need for achievement in the preclinical years than in the clinical years: 15.14±0.49 vs. 13.67±0.38 (p=0.03) (

Figure 3A). With respect to the academic opportunity, we observed a statistically significant increase in the perception score among the students from the clinical compared with those from the preclinical years: 3.29±0.14 vs. 2.69±0.17 (p=0.008) (

Figure 3B). Furthermore, the opportunity for patient care was better highlighted in the clinical group than in the preclinical group: 3.29±0.11 vs. 2.72±0.15 (p=0.008) (

Figure 3C). Finally, the importance of the models was greater for the students in the clinical years than for the students in the preclinical years: 3.8±0.12 vs. 3.38±0.15 (p=0.03) (

Figure 3D).

4. Discussion

Modern management strategies in human resources in health care organizations should consider the sustainability potential of the providers, based on their self-efficacy, self-esteem, and general attitudes and beliefs perception. Thus, further organizational stability could be achieved and qualitative health care procedures guaranteed [

15].

Our study reveals the role of the occupational psychology among medical students, that better tailors the decisional tree for future medical subspecialities. Among the groups of students in different specializations, the analyzed variables, such as self-esteem, self-efficacy, general attitudes and beliefs and career perceptions, are relatively homogeneous. Our results are in accordance with the literature. A recent study highlighted how self-esteem and self-efficacy are critical factors in career decision-making among the medical students. Research indicated that medical students across various fields (surgery, general medicine, etc.) tend to show relatively uniform levels of self-efficacy and self-esteem, which are essential for their career maturity and decision-making abilities [

16]. This is consistent with studies focusing on specialty identity and self-efficacy, where students from various medical disciplines demonstrated similar levels of career maturity and engagement [

17].

Moreover, the importance of psychological factors such as self-esteem and career perception has been highlighted by a study examining flourishing and well-being. These studies revealed that regardless of their specialization, medical students benefit similarly from positive psychological constructs, which mediate their career decisions [

18].

According to our results, the self-esteem of the medical students is closely related to rationality, suggesting that those with high self-esteem tend to think logically. Positive self-evaluations are associated with the need for justice, support, and approval, whereas irrationality is correlated with a desire for comfort and a critical evaluation of others. The need for absolute justice is linked to the importance of social status and a comfortable lifestyle, especially in the urban environment. Current research underscores the importance of self-esteem in rational decision-making and professional development in young adults, including medical students. For example, Harris and Orth highlighted in 2020 that high self-esteem is associated with rational behavior and an increased ability to face academic and professional challenges, which can positively influence students' career paths [

19].

In terms of beliefs and attitudes, various data from the literature suggests that cognitive rigidity and irrational thinking can negatively affect professional adaptability. A study from David et al. discussed the negative impact of irrational beliefs on academic and professional performance, confirming observations that such beliefs can limit career success [

20]. Career motivations, such as the need for specialization and the preference for a comfortable lifestyle, are critical to job satisfaction. Another study revealed that aligning career goals with personal values can increase motivation and career satisfaction [

21].

Self-efficacy, defined as confidence in one's ability to achieve goals, plays a critical role in the academic and professional success. Zajacova et al. identified that academic self-efficacy is a significant predictor of the academic performance and the adjustment to university demands among young adults, highlighting the importance of this skill for medical students [

22]. The results of our study show a significant correlation between interest in the specialty and the importance of a sense of duty. This suggests that students who show a strong interest in a particular medical specialty are motivated by a strong sense of duty to the profession and patients. Moreover, the importance of vocation and responsibility are related to the choice of medical specialties [

23].

Global self-evaluation is a central construct in cognitive theory and is related to various forms of irrational demands, such as the need for absolutist justice and the need for approval, and research. Dryden and David suggest that absolutist demands and emotional needs are predictive factors for negative global self-evaluations [

24]. Specifically, in our study, irrationality was correlated with the need for comfort, the absolutist demand for justice, and the global evaluation of others. Our results are in accordance with those of Ellis et al., in which irrationality might reflect a cognitive tendency to adopt extreme or unrealistic perspectives on the world and others [

25]. This correlation suggests that when students face uncomfortable situations or perceive that justice is not respected, they may exhibit irrational tendencies, thus influencing their learning process and interpersonal relationships.

A statistically significant positive correlation between specialty interest and the importance of sense of duty suggests that students who are strongly interested in a particular specialty also have a well-developed sense of duty to the profession in that type of specialty and to their own patients, and these results are in accordance with the literature [

26]. They noted that the perception of difficulty and complexity of a field can stimulate interest in the in-depth specialization, as students seek to push their limits and acquire advanced skills. The importance of vocation and responsibility in choosing medical specialties integrates this psychosocial context [

23].

Our study revealed that students who value teaching opportunities also appreciate the possibility of engaging in research activities. Our results are in accordance with those of Taylor et al., who revealed a link between the involvement of students in didactic activities and the research interest, considering it a natural extension of the academic learning [

27].

Significant correlations between the year of study and the variables such as need for achievement, didactic opportunity, and opportunity for patient care, in our study, suggest a progressive development of the priorities of students and motivations as they progress through the degree program. These findings are consistent with another research showing that as students progress through medical education, they become more achievement-oriented and increasingly value role models of career success [

28]. The importance of model perception with the progress through medical education could help, further, to develop new sustainable management strategies in human resources.

Moreover, preclinical students often focus more on academic achievement and didactic learning. Some studies have demonstrated that role models significantly influence students' self-efficacy, particularly when these role models are seen as relatable and their success attainable [

29,

30]. Additionally, expectancy-value theory suggests that students who find mentors similar to themselves are more likely to value the associated career path, reinforcing the importance of mentorship in clinical education. This aligns with more recent research emphasizing the critical part that role models play in shaping the students' perceptions of their future careers [

31]. Furthermore, achievement motivation and self-efficacy have been found to fluctuate on the basis of the type of mentorship and patient exposure students receive, which further highlights the transitional priorities from the preclinical to the clinical years [

32]. These studies underscore the evolving nature of the motivations of the medical students and the influence of practical exposure and mentorship as they progress through their education.

The findings of this study emphasize the substantial influence of lifestyle factors on medical students' career preferences, which aligns with the literature. Many medical students today prioritize work‒life balance, flexible schedules, and reduced working hours when selecting their specialties. A survey by Dorsey et al. revealed that the increasing importance of a controllable lifestyle has led to a shift in specialty preferences among U.S. medical students, with fewer students opting for time-demanding fields such as surgery and more favorable fields that offer a more predictable schedule [

33]. Thus, in order to achieve stability of the human resource in the health care area, regardless of the medical sub-specialty, the medical organization should adhere to a predictable work-program [

34].

Furthermore, a study by Lambert and Holmboe revealed that medical students are increasingly focused on selecting specialties that allow them to maintain a balance between their professional and personal lives, contributing to their overall career satisfaction [

35]. These findings mirror those of our study, where a flexible schedule and hobby-job balance were key factors for students aiming to pursue less stressful specialties.

Another study by Dyrbye et al. demonstrated that burnout among medical students and physicians is closely linked to the lifestyle factors, with specialties offering better work‒life balance associated with lower burnout rates [

36]. These findings support our results, highlighting the need to consider lifestyle when guiding students in their career decision-making.

Finally, we observed an absence of a significant correlation between the importance of the sense of vocation and the other analyzed variables. This suggests that a sense of vocation, although considered an essential element in choosing a medical career, may function independently of other factors, such as teaching or research opportunities. This result is supported by the research of Newton and Grayson, who highlighted that vocation can be a strong intrinsic factor but is not necessarily related to external circumstances or other professional motivations [

37].

Study limitations

Our research presents some limitations. Firstly, the lack of significant correlations does not necessarily indicate the absence of differences between groups but may be influenced by sample size. Secondly, the study was monocentric and does not consider the importance of intercultural variability among different societies. Finally, we did not perform a separate analysis of the enrolled international students.

5. Conclusions

Our study highlights the need for applying various occupational psychology tools for a more sustainable human resources in the health care system, considering the medical students as future providers. Further studies that explore other aspects or use alternative measurement methods are needed to confirm our results

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, E.N and S.I.; methodology, S.A.C., A.-M.V., and E.N. ; software, S.I., and C.M.; validation, A-.M.V., M.M.M, and T.I.; formal analysis, C.V.A., and S.I.; investigation, E.N., and G.D.; resources, T.I., and S.I.; data curation, M.C.P., and C.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C.P., S.A.C., and E.N.; writing—review and editing, T.I., S.I., and C.V.A; visualization, G.D., and M.M.M.; supervision, S.I.; project administration, G.D.; funding acquisition, E.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”.

Funding

The APC was supported by “Carol Davila” University of Medicine and Pharmacy Bucharest, Romania.

Institutional Review Board Statement

“The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Fundeni Clinical Institute (10337/07.03.2024).”.

Informed Consent Statement

The informed consent for publication was included in the questionnaires and signed by each participant.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

“The authors declare no conflicts of interest.”.

Financial Interests

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

References

- Kruk, M.E.; Gage, A.D.; Arsenault, C.; Jordan, K.; Leslie, H.H.; Roder-DeWan, S.; Adeyi, O.; Barker, P.; Daelmans, B.; Doubova, S.V.; et al. High-Quality Health Systems in the Sustainable Development Goals Era: Time for a Revolution. The Lancet Global Health 2018, 6, e1196–e1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Netsanet Workneh Gidi; Ararsa Horesa; Habtemu Jarso; Workineh Tesfaye; Gudina Terefe Tucho; Siraneh, M. A.; Jemal Abafita Prevalence of Low Self-Esteem and Mental Distress among Undergraduate Medical Students in Jimma University: A Cross- Sectional Study. Ethiop J Health Sci 2021, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronen, T.; Kerret, D. Promoting Sustainable Wellbeing: Integrating Positive Psychology and Environmental Sustainability in Education. IJERPH 2020, 17, 6968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Z.; Panadero, E.; Wang, X.; Zhan, Y. A Systematic Review on Students’ Perceptions of Self-Assessment: Usefulness and Factors Influencing Implementation. Educ Psychol Rev 2023, 35, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sa, B.; Ojeh, N.; Majumder, M.A.A.; Nunes, P.; Williams, S.; Rao, S.R.; Youssef, F.F. The Relationship Between Self-Esteem, Emotional Intelligence, and Empathy Among Students From Six Health Professional Programs. Teaching and Learning in Medicine 2019, 31, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artino Jr., A. R. Academic Self-Efficacy: From Educational Theory to Instructional Practice. Perspect Med Educ 2012, 1, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B.J. Self-Efficacy: An Essential Motive to Learn. Contemporary Educational Psychology 2000, 25, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Săucan, D. Ștefana; Bolohan, A.B.; Micle, I.M.; Preda, G. Influenţa Perfecţionismului Asupra Dezvoltării Tulburărilor Anxioase. Revista de psihologie 2018, 64, 327–339. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, J.H.; Chae, S.J.; Chang, K.H. The Relationship among Self-Efficacy, Perfectionism and Academic Burnout in Medical School Students. Korean J Med Educ 2016, 28, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babenko, O.; Oswald, A. The Roles of Basic Psychological Needs, Self-Compassion, and Self-Efficacy in the Development of Mastery Goals among Medical Students. Medical Teacher 2019, 41, 478–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R.; Matthias, J. Scala de Autoeficacitate (Adaptat de Moldovan, R.). In Sistem de evaluare clinica, D. David (coordonator); Editura RTS: Cluj-Napoca, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer, R.; Matthias, J. Scala de Stimă de Sine Rosenberg (Adaptat de Moldovan, R.). In Scală de evaluare clinica, D. David (coordonator); Editura RTS: Cluj-Napoca, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lindner, H.; Kirkby, R.; Wertheim, E.; Birch, P. Scala de Atitudini Și Convingeri Generale (Adaptat de Trip, S.). In Scală de evaluare clinica, D. David (coordonator); Editura RTS: Cluj-Napoca, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Anand, R.; Sankaran, P.S. Factors Influencing the Career Preferences of Medical Students and Interns: A Cross-Sectional, Questionnaire-Based Survey from India. J Educ Eval Health Prof 2019, 16, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoxha, G.; Simeli, I.; Theocharis, D.; Vasileiou, A.; Tsekouropoulos, G. Sustainable Healthcare Quality and Job Satisfaction through Organizational Culture: Approaches and Outcomes. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignault, A.; Rastoder, M.; Houssemand, C. The Relationship between Self-Esteem, Self-Efficacy, and Career Decision-Making Difficulties: Psychological Flourishing as a Mediator. EJIHPE 2023, 13, 1553–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chong, M.C.; Han, Y.; Wang, H.; Xiong, L. The Mediating Effects of Self-Efficacy and Study Engagement on the Relationship between Specialty Identity and Career Maturity of Chinese Nursing Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Nurs 2024, 23, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klassen, R.M.; Klassen, J.R.L. Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Medical Students: A Critical Review. Perspect Med Educ 2018, 7, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, M.A.; Orth, U. The Link between Self-Esteem and Social Relationships: A Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2020, 119, 1459–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, D.; Lynn, S.J.; Ellis, A. Rational and Irrational Beliefs: Research, Theory, and Clinical Practice; Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Judge, T.A.; Bono, J.E.; Erez, A.; Locke, E.A. Core Self-Evaluations and Job and Life Satisfaction: The Role of Self-Concordance and Goal Attainment. Journal of Applied Psychology 2005, 90, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajacova, A.; Lynch, S.M.; Espenshade, T.J. Self-Efficacy, Stress, and Academic Success in College. Res High Educ 2005, 46, 677–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafferty, F.W.; Castellani, B. The Increasing Complexities of Professionalism: Academic Medicine 2010, 85, 288–301. [CrossRef]

- Dryden, W.; David, D. Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy: Current Status. J Cogn Psychother 2008, 22, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, A.; Joffe Ellis, D. Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy , 2nd ed; American Psychological Association: Washington, 2019; ISBN 978-1-4338-3032-7. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, H.G.; Vermeulen, L.; Van Der Molen, H.T. Longterm Effects of Problem-Based Learning: A Comparison of Competencies Acquired by Graduates of a Problem-Based and a Conventional Medical School. Med Educ 2006, 40, 562–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.C.M.; Hamdy, H. Adult Learning Theories: Implications for Learning and Teaching in Medical Education: AMEE Guide No. 83. Medical Teacher 2013, 35, e1561–e1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prince, K.J.A.H.; Van De Wiel, M.; Scherpbier, A.J.J.A.; Can Der Vleuten, C.P.M.; Boshuizen, H.P.A. [No Title Found]. Advances in Health Sciences Education 2000, 5, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helmich, E.; Bolhuis, S.; Dornan, T.; Laan, R.; Koopmans, R. Entering Medical Practice for the Very First Time: Emotional Talk, Meaning and Identity Development: Entering Medical Practice for the Very First Time. Medical Education 2012, 46, 1074–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusurkar, R.A.; Croiset, G.; Mann, K.V.; Custers, E.; Ten Cate, O. Have Motivation Theories Guided the Development and Reform of Medical Education Curricula? A Review of the Literature: Academic Medicine 2012, 87, 735–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Li, Y. The Relationship between Achievement Motivation and College Students’ General Self-Efficacy: A Moderated Mediation Model. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 1031912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, S.; Carr, S.E.; Connaughton, J.; Celenza, A. Student Motivation to Learn: Is Self-Belief the Key to Transition and First Year Performance in an Undergraduate Health Professions Program? BMC Med Educ 2019, 19, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorsey, E.R.; Jarjoura, D.; Rutecki, G.W. Influence of Controllable Lifestyle on Recent Trends in Specialty Choice by US Medical Students. JAMA 2003, 290, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.; Smith, A.M. Standards and Evaluation of Healthcare Quality, Safety, and Person-Centered Care.2022 [Updated 2022 Dec 13]. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL) 2025 Jan- Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK576432/.

- Schor, N.F.; Troen, P.; Kanter, S.L.; Levine, A.S. The Scholarly Project Initiative: Introducing Scholarship in Medicine through a Longitudinal, Mentored Curricular Program: Academic Medicine 2005, 80, 824–831. [CrossRef]

- Dyrbye, L.N. Relationship Between Work-Home Conflicts and Burnout Among American Surgeons: A Comparison by Sex. Arch Surg 2011, 146, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, D.A. Trends in Career Choice by US Medical School Graduates. JAMA 2003, 290, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).