1. Introduction

Walkability refers to the ability of individuals to safely and comfortably walk to essential services, amenities, and destinations within a reasonable distance. It is a key factor in urban planning and transportation, directly impacting public health, environmental sustainability, and overall quality of life [

2,

4,

5,

9,

9]. Recognizing the importance of walkability, city leaders and policymakers worldwide are making concerted efforts to enhance pedestrian-friendly environments by improving infrastructure, reducing vehicular dependence, and creating safer, more accessible pathways for pedestrians.

One of the primary methods used to assess walkability is pedestrian interviews and surveys, which gather insights into how people perceive and experience sidewalks and pedestrian spaces. These surveys serve as a representative evaluation tool that takes into account subjective aspects such as perceived safety, convenience, and comfort [

6,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. However, while these responses provide valuable qualitative data, they are inherently prone to biases and individual subjectivity. Factors such as personal preferences, prior experiences, and environmental conditions at the time of the survey can influence the results, leading to inconsistencies and a lack of expert-driven assessment.

To ensure a more structured and regulation-compliant evaluation of pedestrian spaces, government agencies often rely on trained experts to conduct on-site inspections. These experts evaluate sidewalk conditions, verify compliance with accessibility standards, and assess the overall adequacy of pedestrian infrastructure based on pre-established regulatory frameworks. While expert evaluations provide more objective insights, they come with significant drawbacks. Traditional on-site inspections are time-consuming, labor-intensive, and require substantial financial resources. The logistical challenges of deploying experts to assess large urban areas make these methods inefficient, especially in rapidly growing cities with evolving pedestrian needs.

Furthermore, conventional assessment methods often fail to adequately capture the dynamic and contextual elements that influence walkability. Pedestrian behavior, real-time environmental changes, and situational factors such as weather conditions, traffic patterns, and urban design intricacies play a crucial role in shaping the pedestrian experience [

11,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

22,

23,

24,

25,

35,

36,

37]. Relying solely on static assessments may overlook these vital aspects, leading to incomplete or outdated evaluations. As a result, there is a growing need for innovative and data-driven approaches that can provide more comprehensive, real-time insights into walkability while optimizing resource allocation for urban planners and decision-makers.

In this paper, we propose an automated method for recognizing sidewalk types using wearable sensors that take pedestrian behavior into account. Wearable sensors can be used on pedestrians to monitor their physiological responses, allowing for an analysis of how the surrounding environment affects these responses. Previous research has demonstrated that various sidewalk characteristics or defects cause changes in human responses [

26,

28] Our proposed method recognizes sidewalk surface types by extracting features from time-domain data, including average, standard deviation, and Single Value Magnitude (SVM). We employed 15 features derived from SVM, which were further refined using Kalman filters, moving averages, and low-pass filters. In addition, we incorporated frequency-domain features, such as those obtained through the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT), to enhance surface type classification [

29].

The main contributions of the study are summarized as follows:

This approach introduces a novel method that combines deep learning, the Kalman filter, and FFT - fundamental concepts in signal processing - to recognize different surface types. The proposed approach is anticipated to offer significant benefits in the domains of human behavior classification and recognition.

In [

12,

13], only normal and abnormal surface types were classified, whereas our proposed method distinguishes between five different sidewalk surface types and achieves higher recognition accuracy than previous studies.

The proposed method is computationally efficient, relying on a relatively simple deep learning architecture. The structure of the deep learning model used in this study is presented in

Table 2 [

30,

31].

This study also explores the optimal placement of wearable sensors for sidewalk surface detection. We evaluate the recognition accuracy across different configurations, including single-, two-, and three-sensor setups (see Table 4). The highest accuracy was obtained with sensors positioned on both the hip and ankle.

2. Related Works

This section presents a comprehensive overview of existing sidewalk evaluation methods. Subsection 2.1 covers traditional approaches involving on-site inspections, checklists, and expert assessments, and examines their limitations, including subjectivity, time and labor intensity, and spatial constraints. Subsection 2.2 explores recent technological advancements, highlighting machine learning and deep learning-based methods. In particular, it focuses on approaches that leverage human activity recognition techniques to automatically detect and interpret human movements and behaviors. The discussion emphasizes how these modern methods enhance the efficiency and objectivity of sidewalk evaluation, marking a shift from conventional practices.

2.1. Traditional Approaches for Sidewalk Assessment

As sidewalk assessment is essential for evaluating walkability, numerous methods have been developed to assess sidewalk conditions. Traditionally, pedestrian surveys have been among the most widely used approaches for identifying sidewalk defects [

26]. These surveys typically involve pedestrians or inspectors physically walking through an area to detect issues. However, this method relies heavily on the subjective judgment of the observer, limiting its accuracy and making it unsuitable for quantitatively analyzing the characteristics or severity of defects [

12,

26]. Additionally, it is time- and labor-intensive, leading to high costs and limited coverage, which reduces overall efficiency [

12]. Government agencies also commonly conduct on-site inspections using trained personnel to assess compliance with regulations and evaluate sidewalk conditions [

39]. While these inspections offer more systematic evaluations by skilled professionals, they are similarly constrained by high labor costs and extended inspection durations, making them impractical for large-scale implementation [

13,

39].

To address the limitations of traditional approaches, researchers have proposed various methods aimed at evaluating sidewalk conditions more efficiently and objectively. For instance, Sousa et al. developed a technique based on on-site measurements, enabling a degree of quantitative analysis [

40]. Another study introduced a method for calculating the Pavement Condition Index (PCI) using survey data tailored specifically for sidewalk assessment. PCI provides a quantitative measure of pavement and sidewalk quality, serving as a valuable standard for prioritizing repairs and allocating maintenance budgets [

28].

Despite these advancements, several challenges remain. Many of these methods still depend on on-site inspections, making them labor-intensive and requiring human involvement—an obstacle to full automation. Moreover, their applicability is often limited to specific geographic regions or contexts, reducing their scalability and effectiveness in large, densely populated urban areas [

13]. Consequently, the persistent limitations of traditional methods underscore the need for sensor-based approaches to sidewalk condition assessment.

2.2. Advanced Approaches for Sidewalk Assessment

In [

26,

27], they highlighted the limitations of survey-based sidewalk evaluation, emphasizing its high cost and lack of objectivity. In response, the author proposed sensor-based approaches for sidewalk condition assessment. In [

26] , a method was introduced to detect horizontal and vertical cracks, as well as the presence of holes on sidewalks, using accelerometer data in conjunction with a Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier. Subsequently, in [

27] proposed a technique to distinguish between normal sidewalks and those studies [

26,

27], have highlighted the limitations of survey-based sidewalk evaluation, particularly its high cost and lack of objectivity. In response, sensor-based approaches have been proposed to improve sidewalk condition assessment. For example, [

26] introduced a method for detecting horizontal and vertical cracks, as well as holes, using accelerometer data combined with a Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier. Building on this, [

27] proposed a technique to differentiate between normal sidewalks and those obstructed by fallen leaves or physical barriers. This approach leveraged both accelerometer and heart rate sensor data to enhance recognition accuracy..

In [

7], a study was conducted using smartphone-based accelerometers to classify various road conditions, including flat, uphill, and downhill surfaces. Experiments were carried out while riding a bicycle, with the smartphone placed in different locations such as a pants pocket, chest pocket, and bicycle basket. Road condition classification was performed using the x-axis component of the acceleration signal. In [

12], the authors explored sidewalk surface classification using machine learning techniques. This study categorized road conditions into normal and abnormal types, including flat surfaces, grass-covered paths, obstacle-laden areas, uneven terrain, and leaf-covered walkways. Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) sensors were mounted on the head, waist, and ankle, and the performance of various machine learning algorithms—such as SVM, Random Forest, and Logistic Regression—was analyzed based on sensor placement.

With the advancement of deep learning, several studies have applied these techniques to road condition recognition. In [

38], a method was proposed to identify road environments that may hinder wheelchair navigation—such as stairs, steep slopes, and doorways—using smartphone accelerometer data. Features such as mean, standard deviation, and inter-axis correlations (x–y, x–z, y–z) were extracted to train a Deep Neural Network (DNN) model. In [

13], the authors extended their previous work [

12] by using ankle-mounted sensors and a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) model to classify the five road conditions defined in [

12] as either normal or abnormal sidewalk surface types. Additionally, [

21] introduced a smartphone-based accelerometer approach for recognizing six types of road surfaces. This study combined frequency-domain features—such as the maximum value and standard deviation for each axis—with time-domain features, and evaluated classification performance using CNN and VGG16 architectures.

3. Classification of Sidewalk Surface Types using Deep Learning and Signal Processing

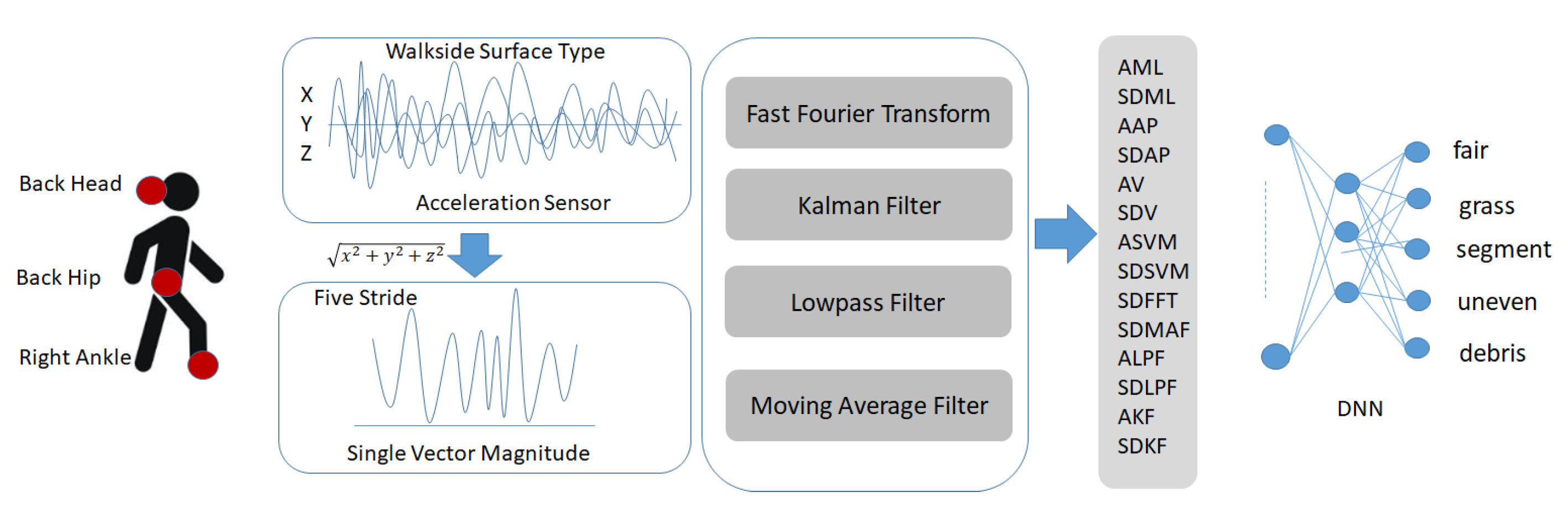

This section elaborates the data analysis process used to recognize various sidewalk surface types. The process begins by computing the Single Vector Magnitude (SVM) from the three-axis acceleration data (x, y, and z) collected by wearable sensors. SVM provides a consolidated measure of overall motion intensity, independent of direction. After calculating the SVM, several signal processing techniques are applied to extract informative features. These include the FFT for frequency-domain analysis, along with Kalman filtering, low-pass filtering, and moving average filtering to suppress noise and enhance signal quality. The resulting combination of time-domain and frequency-domain features serves as input to a Deep Neural Network (DNN), which classifies the sidewalk surface into one of five predefined categories.

Figure 1.

Framework of proposed system.

Figure 1.

Framework of proposed system.

3.1. Data Collection

Twelve participants, consisting of eight healthy men and four women, participated in the experiment. The participants wore accelerometer sensors in three locations: the back of head, the lower back above the hip, and the outside of the right shoe to measure acceleration. The accelerometers used were Mbient sensors (MetaMotionR, Mbient Lab, San Francisco, CA, USA). The measurement frequency of the 3-axis accelerometers was set to 100Hz. The experiment was conducted n the sidewalk surrounding the Peter Kiewit Institute of the University of Nebraska at Omaha. Measurements were taken on five commonly occurring types of surfaces: regular and irregular walking surface types were created, including fair, a grass-covered, obstructions, uneven surface, and debris-covered surface. For detailed information on the data collection scenarios, see [

12,

13].

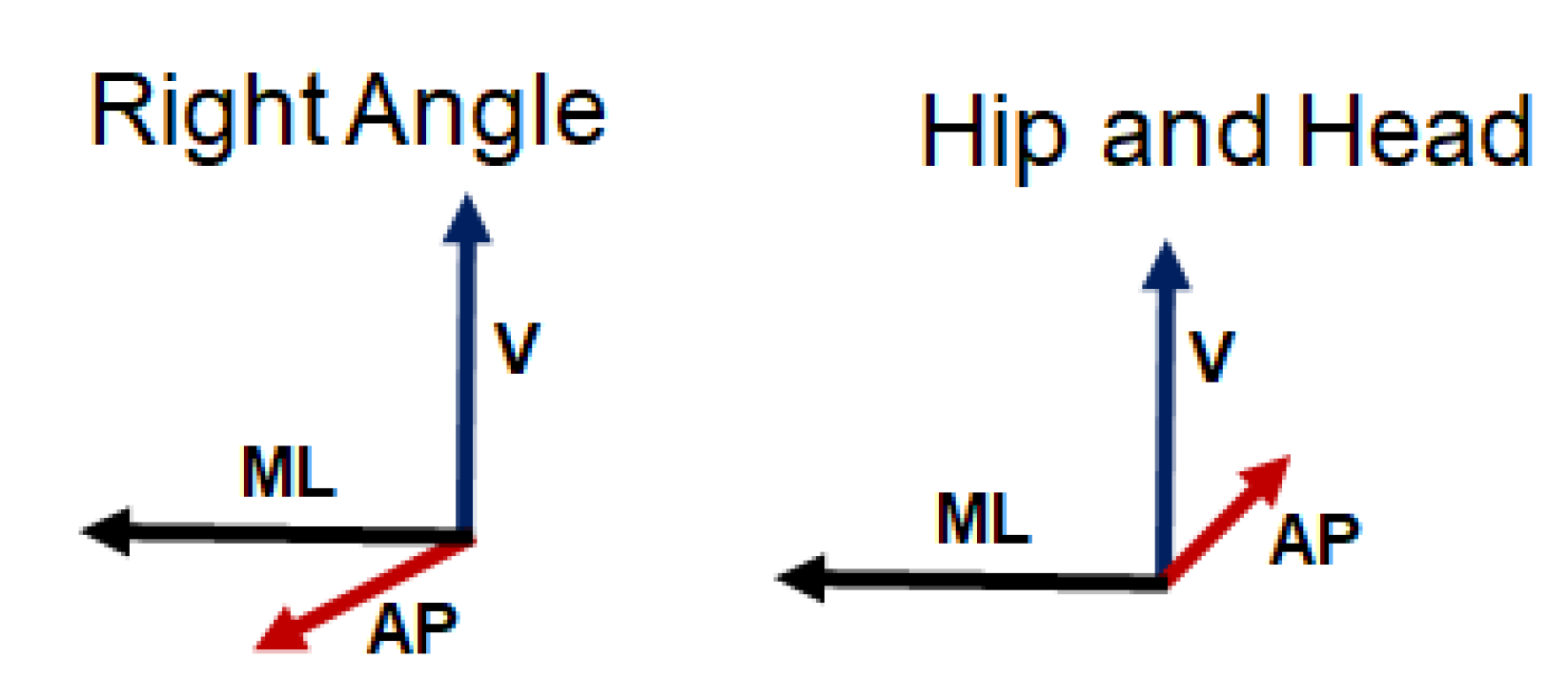

Figure 2.

Accelerometers’ directions for all three locations.

Figure 2.

Accelerometers’ directions for all three locations.

For the purpose of data analysis, we generated a total of 600 simulation datasets, each derived from acceleration sensor data recorded while a pedestrian was walking on different types of sidewalk surfaces. These sidewalk surfaces were classified into five distinct categories: fair, grass, segments, uneven, and debris. Each category represents a different walking condition, affecting the pedestrian’s movement and the sensor readings accordingly.

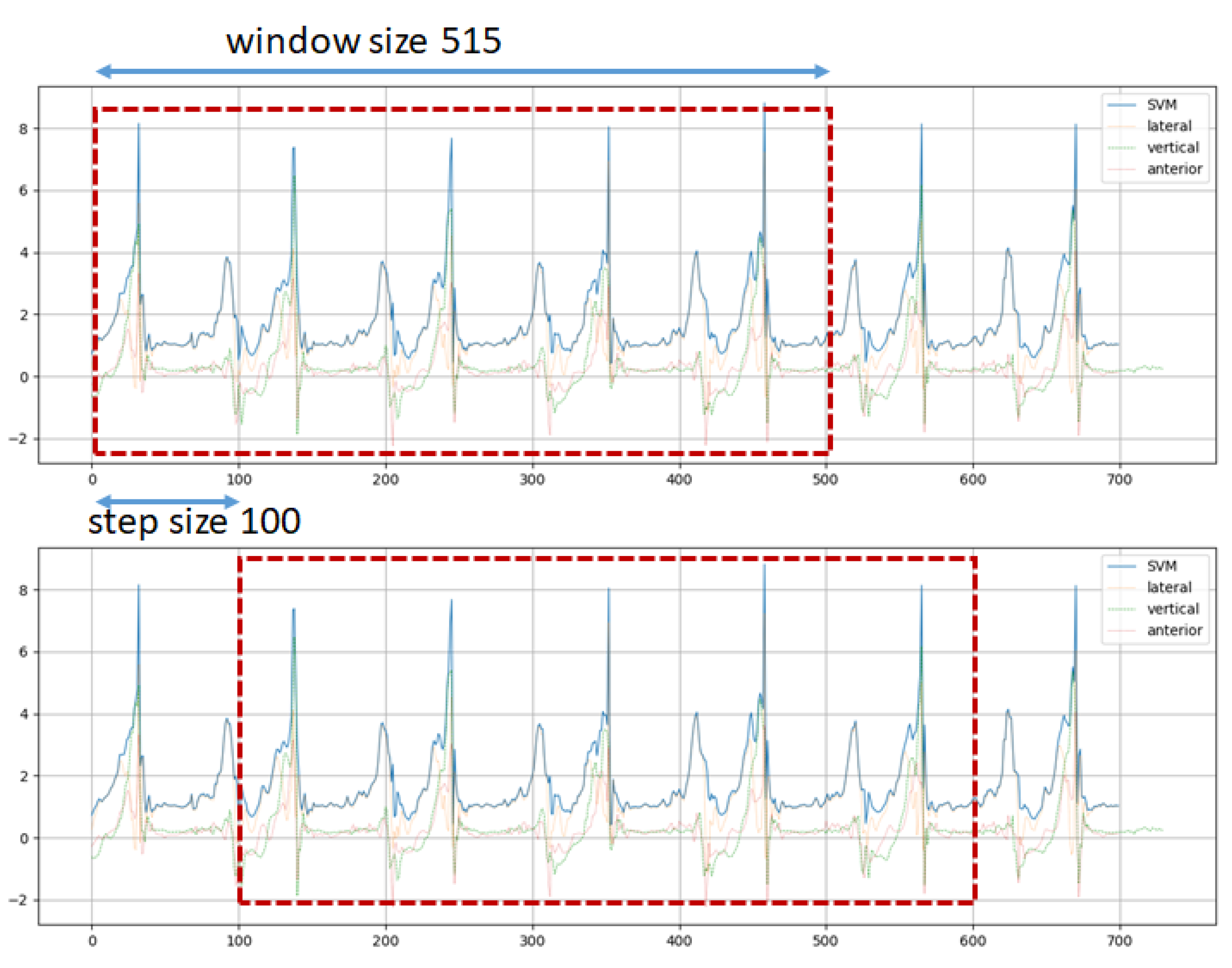

To ensure a diverse and balanced dataset, we constructed 10 independent datasets for each sidewalk surface condition. As there are five different surface types, this resulted in a total of 600 datasets. Each dataset was extracted from acceleration sensor readings collected during pedestrian movement and consisted of 515 data points, which corresponded to a walking sequence of five consecutive steps. The selection of this window size was based on an analysis of step patterns and sensor signal characteristics to effectively capture the variations in movement across different surfaces.

The datasets were created using a sliding window approach, a common method in time-series data analysis. Specifically, the window size was set to 515 data points, ensuring that each dataset covered a walking segment of five steps. To facilitate continuous data extraction while preserving temporal dependencies, a step size of 100 was applied. This means that instead of extracting entirely independent windows, each subsequent dataset partially overlapped with the previous one, allowing for a richer and more detailed representation of walking dynamics across different sidewalk surfaces. By employing this sliding window method, we were able to generate a comprehensive dataset that captures the variations in acceleration signals influenced by different sidewalk conditions. This data construction process is illustrated in

Figure 3, providing a visual representation of how the windows were selected and how the step size was applied during data extraction.

3.2. Features Extraction using FFT, Kalman, Low Pass, and Moving Average Filters

The 3-axis accelerometer measures the acceleration magnitude in the vertical (V), antero-posterior (AP) and medio-lateral (ML) directions. By calculating the SVM of the three acceleration magnitudes as shown in Equation (

1), we can determine the overall acceleration acting on the object, which is commonly used in acceleration-based research.

where the

.

The single vector magnitude (or the magnitude of the acceleration vector) is a way to combine the acceleration values from all three axes into a single scalar value that represents the overall acceleration regardless of direction. It gives the total acceleration experienced by the object or device in 3D space. Time-domain features, including the mean and standard deviation, were extracted based on the SVM. Additionally, the mean and standard deviation for each directional axis were also computed and utilized as feature inputs.

From a signal processing perspective, the FFT is a mathematical tool used to analyze and decompose a signal into its frequency components. In this context, a signal is typically a time-domain function, and the Fourier transform converts this time-domain signal into a frequency-domain representation. This transformation reveals the presence and magnitude of various frequencies within the original signal, which is crucial for understanding, filtering, or modifying the signal. The output of the Fourier transform is a complex-valued function, where the magnitude represents the amplitude of each frequency component, and the phase provides information about the timing or phase shift of these components [

32,

34]. In the study, we analyze the frequency components of the SVM given as (

2).

where

represents the frequency-domain representation of the signal at frequency index

k,

N is the total number of acceleration samples within a window size of 515.

A Kalman filter is an algorithm used to estimate the state of a system over time, particularly when the system is subject to uncertainty or noise. It is widely used in control systems, signal processing, and robotics for tracking or filtering signals. The Kalman filter provides an optimal estimation of a system’s state by combining measurements from sensors with a mathematical model of the system, taking into account both the noise in the measurements and the uncertainty in the model. The initial input value of Kalman filter algorithm is set to

.

The equations from (

4) to () describe the algorithm for applying a standard Kalman filter.

represents the estimated value of the Kalman filter .

It is well known that the Kalman filter is applied recursively; therefore, after updating equation (

8), the process is repeated at each time step.

To compute the Kalman filter, we set the process noise covariance , and initialize the error covariance matrix P as a zero matrix of size 514.

A low-pass filter is an electronic or mathematical filter that allows signals with frequencies lower than a certain cutoff frequency to pass through while attenuating (reducing) the amplitude of signals with frequencies higher than the cutoff frequency. Essentially, it "passes" low-frequency signals and blocks or reduces high-frequency signals, making it useful for noise reduction or signal smoothing [

33]. We get low pass filter from SVM as (

9).

where

.

A moving average filter is a simple digital filter used to smooth or reduce noise in time series or signal data by averaging a fixed number of consecutive data points, called the window size. The window size determines how many data points are included in each average calculation: A smaller window size preserves more details but offers less smoothing, whereas a larger window size provides greater smoothing but may diminish responsiveness to short-term changes. This process helps eliminate high-frequency noise while preserving the general trend of the signal [

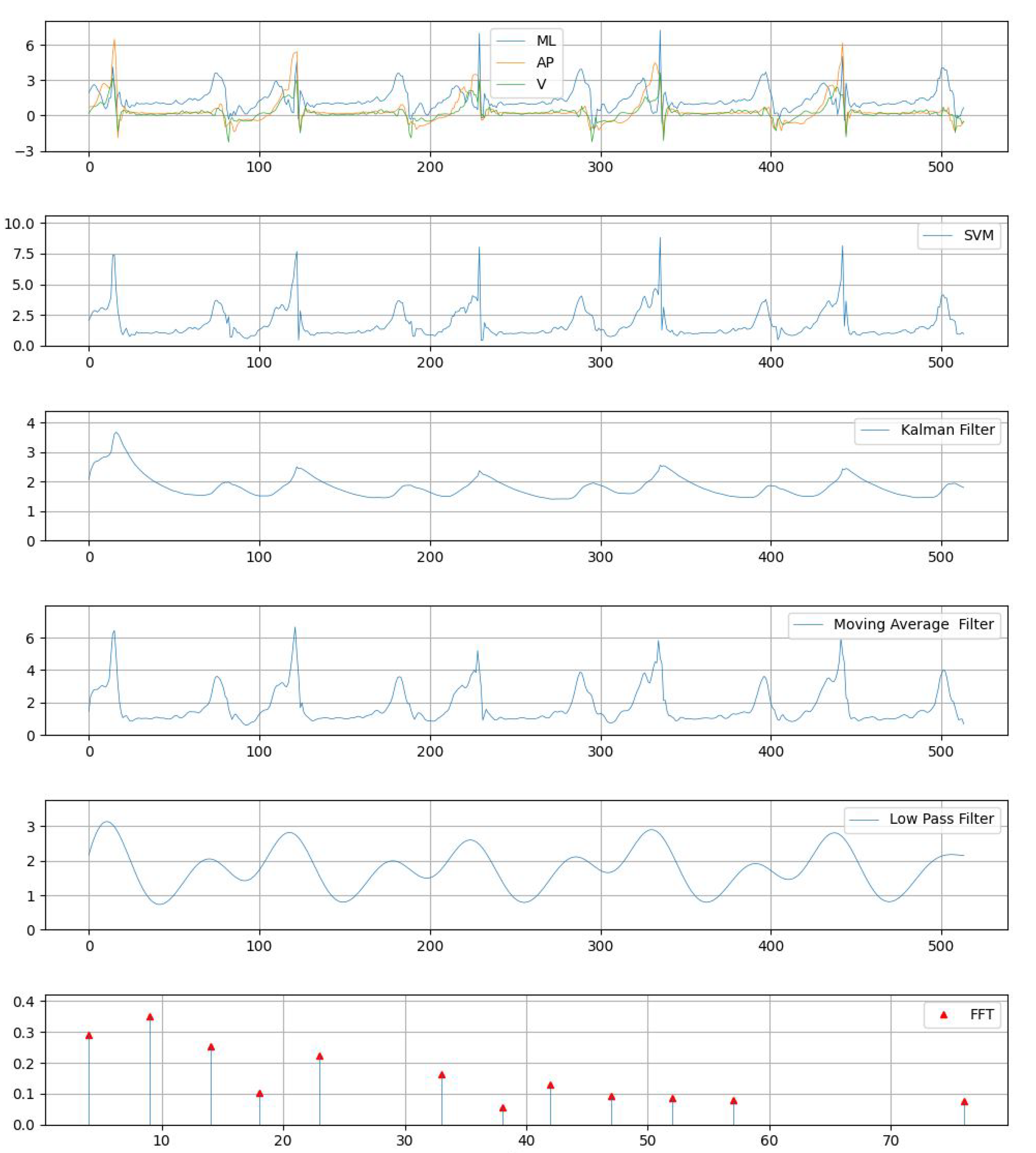

33]. For an example of applying these filters to raw signals, please see

Figure 4. We caluate moving average filter using SVM as (

10) and (

11).

Table 1.

Description selected 15 features.

Table 1.

Description selected 15 features.

| Category |

Feture |

Description |

| ]8*Time Domain |

AML |

average of ML-axis for 515 acceleration value |

| |

SDML |

standard deviation of ML-axis for 515 acceleration value |

| |

AAP |

average of AP-axis for 515 acceleration value |

| |

SDAP |

standard deviation of AP-axis for 515 acceleration value |

| |

AV |

average of V-axis for 515 acceleration value |

| |

SDV |

standard deviation of V-axis for 515 acceleration value |

| |

ASVM |

average of SVM for 515 acceleration value |

| |

SDSVM |

standard deviation of SVM for 515 acceleration value |

| ]6*Filter Domain |

AMAF |

average of moving average filter for SVM 515 acceleration value |

| |

SDMAF |

standard deviation of moving average filter for SVM 515 acceleration value |

| |

ALPF |

average of low pass filter for SVM 515 acceleration value |

| |

SDLPF |

standard deviation of low pass filter for SVM 515 acceleration value |

| |

AKF |

average of Kalman filter for SVM 515 acceleration value |

| |

SDKF |

standard deviation of Kalman filter for SVM 515 acceleration value |

| ]1*Frequency Domain |

SDFFT |

standard deviation of FFT for SVM 515 acceleration value |

3.3. Structure of Deep Nerural Network

The deep learning architecture employed for recognizing sidewalk surface types was based on a DNN. As shown in

Table 2, the DNN consists of an input layer, two hidden layers, and one output layer. As for the activation function, ReLU was used for the hidden layer and the Sigmoid function was used for the output layer. The hidden nodes were composed of 1,000 and 800 nodes, respectively, and the print certificate was composed of 5 nodes because it distinguishes 5 surface types. Adam and CrossEntropy functions are used as optimization and loss functions, respectively. The learning rate was set to 0.001.

Table 2.

Summary of the proposed DNN model

Table 2.

Summary of the proposed DNN model

| Layer |

Output Shape |

Parameters |

| Linear |

[-1, 1000] |

16,000 |

| ReLU |

[-1, 1000] |

0 |

| Linear |

[-1, 800] |

800,800 |

| ReLU |

[-1, 800] |

0 |

| Linear |

[-1, 5] |

4,005 |

| Sigmoid |

[-1, 5] |

0 |

4. Experimental Results

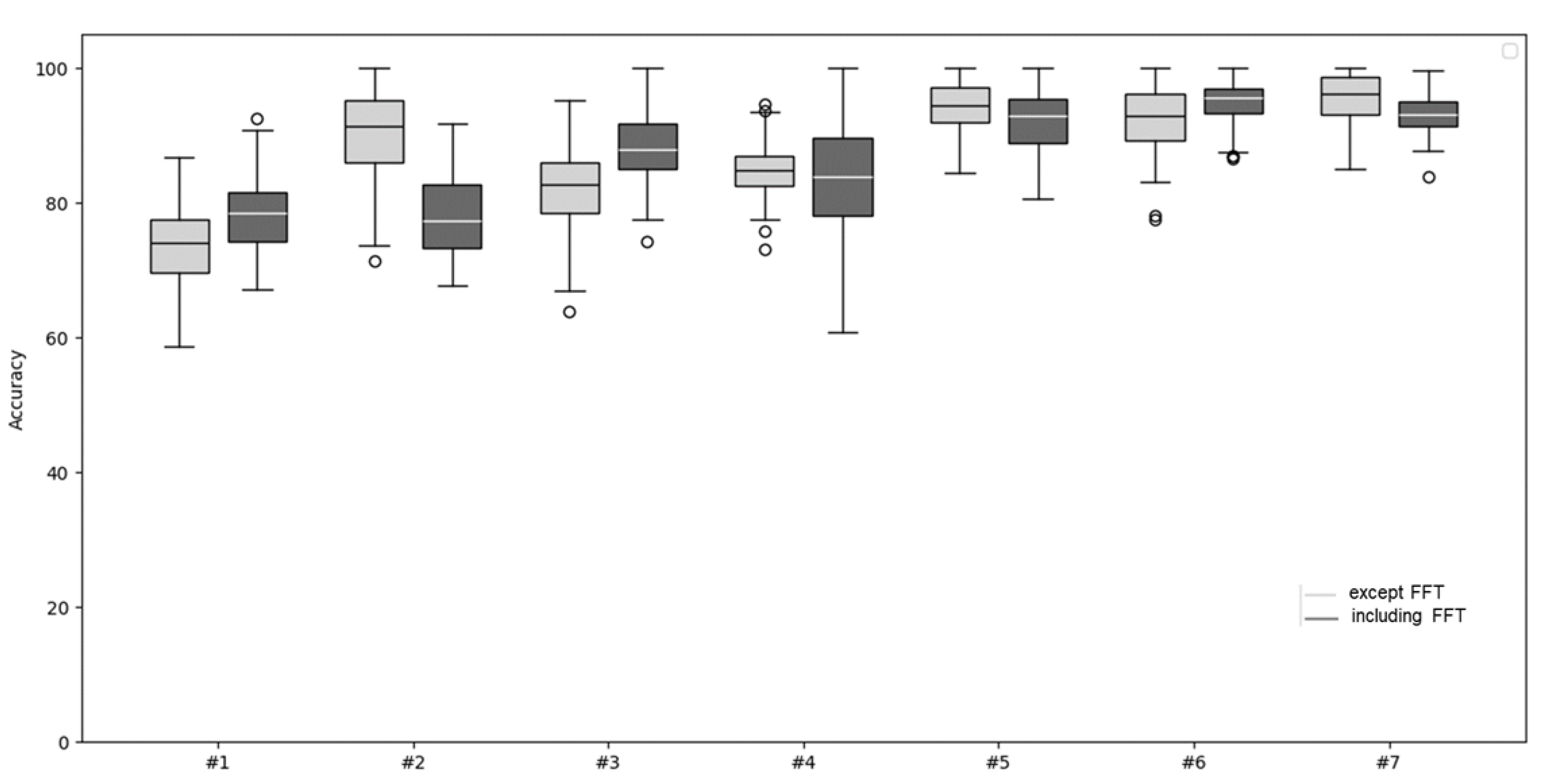

Twelve participants, labeled A through L, took part in the experiment. We conducted experiments using ten-fold cross-validation across five different sidewalk surface types. Specifically, we created ten experimental datasets for each surface type, numbered 0 through 9. Each experiment was performed by training on nine datasets while excluding one for testing. Experiments #1, #2, and #3 were conducted using a single sensor attached to the head, waist, and ankles, respectively. Experiments #4, #5, and #6 involved two sensors in different combinations: head and waist, waist and ankles, and head and ankles. Lastly, Experiment #7 utilized all three sensors simultaneously.

In this study, we conducted two types of experiments to analyze how the composition of features affects classification performance. The first experiment utilized only 14 features extracted from the time domain, excluding any frequency-domain information. In contrast, the second experiment employed a total of 15 features, which included the same 14 time-domain features along with an additional frequency-domain feature derived using the FFT. The results of each experiment are summarized in

Table 3 and

Table 4. When comparing the experimental results, we observed that, despite both experiments being conducted under similar conditions, the inclusion of the FFT feature consistently led to higher classification accuracy. This suggests that frequency-domain information can complement time-domain features by capturing signal patterns or characteristics that are otherwise difficult to identify. Therefore, we confirmed through experimentation that incorporating the FFT feature contributes to improving the model’s performance.

Table 3 presents the experimental results using 14 features, excluding the frequency domain feature SDFFT.

Table 4 presents the experimental results obtained using all features, including the frequency domain feature SDFFT. In single-sensor experiments (#1–#3), the hip sensor recorded the lowest accuracy at 78.0%, while the ankle sensor achieved the highest accuracy at 88.17%. Among the two-sensor setups (#4–#6), the head and hip combination had the lowest accuracy at 84.67%, whereas the hip and ankle combination in Experiment #6 yielded the highest accuracy. Although Experiment #7, which incorporated all three sensors, was expected to provide the highest accuracy, Experiment #6 slightly outperformed it. However, Experiment #7 demonstrated the lowest standard deviation, indicating more consistent results across trials.

Figure 5 shows box plots derived from the data in

Table 3 and

Table 4. As shown in the box plots, Experiment #6, which includes FFT feature, demonstrates the best overall performance among all the experiments. This is evident from its consistently higher median values, narrower interquartile range, and fewer outliers, indicating both superior accuracy and stability. The incorporation of FFT feature appears to have significantly contributed to this improved performance.

The

Table 5 shows the accuracy of each participant in Experiment #6. While experimental participants E, H and L got 100% correct. For the test case I, the model correctly recognized 44 out of 50 sidewalk surface types, showing a recognition rate of 88%.

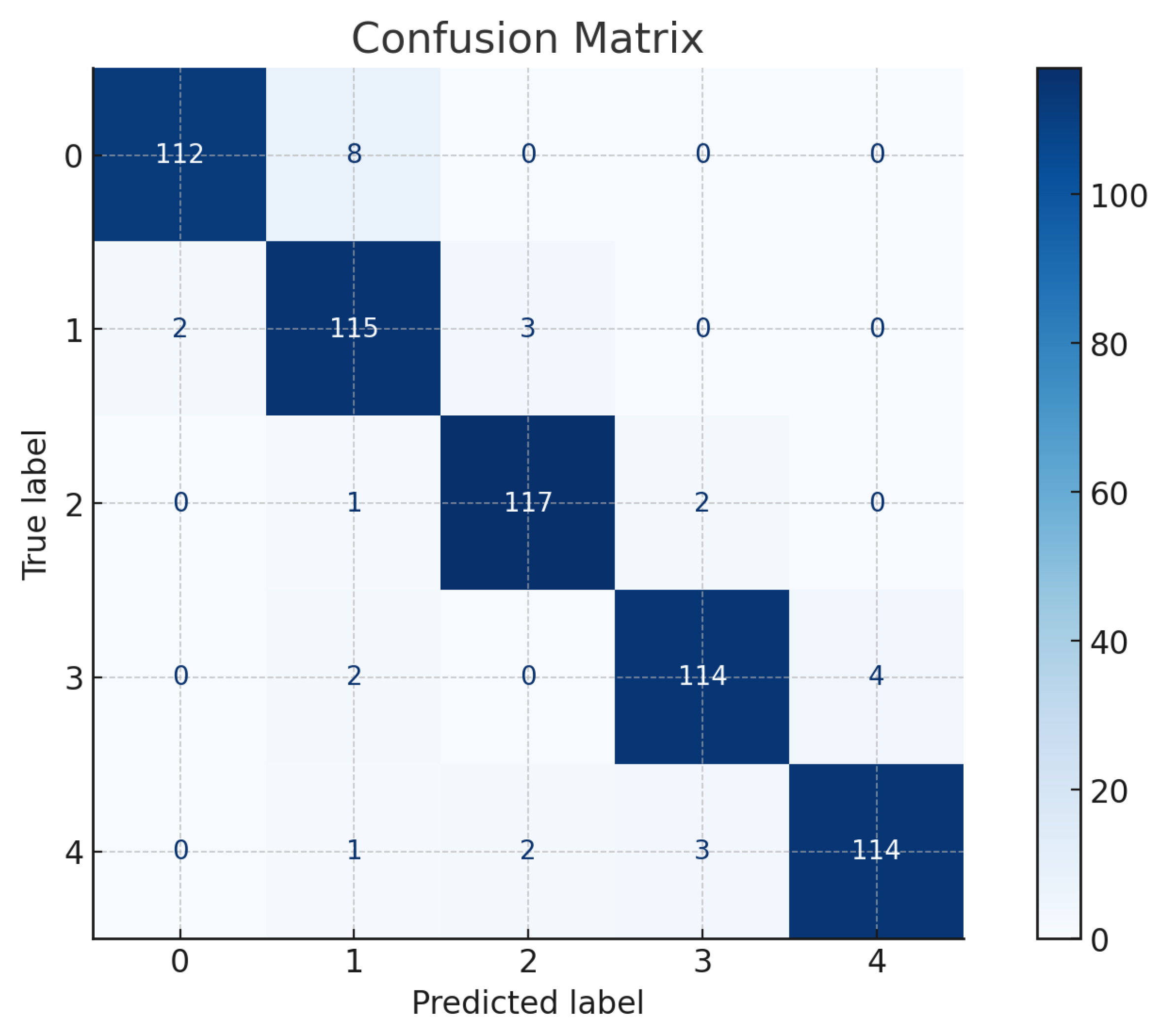

The

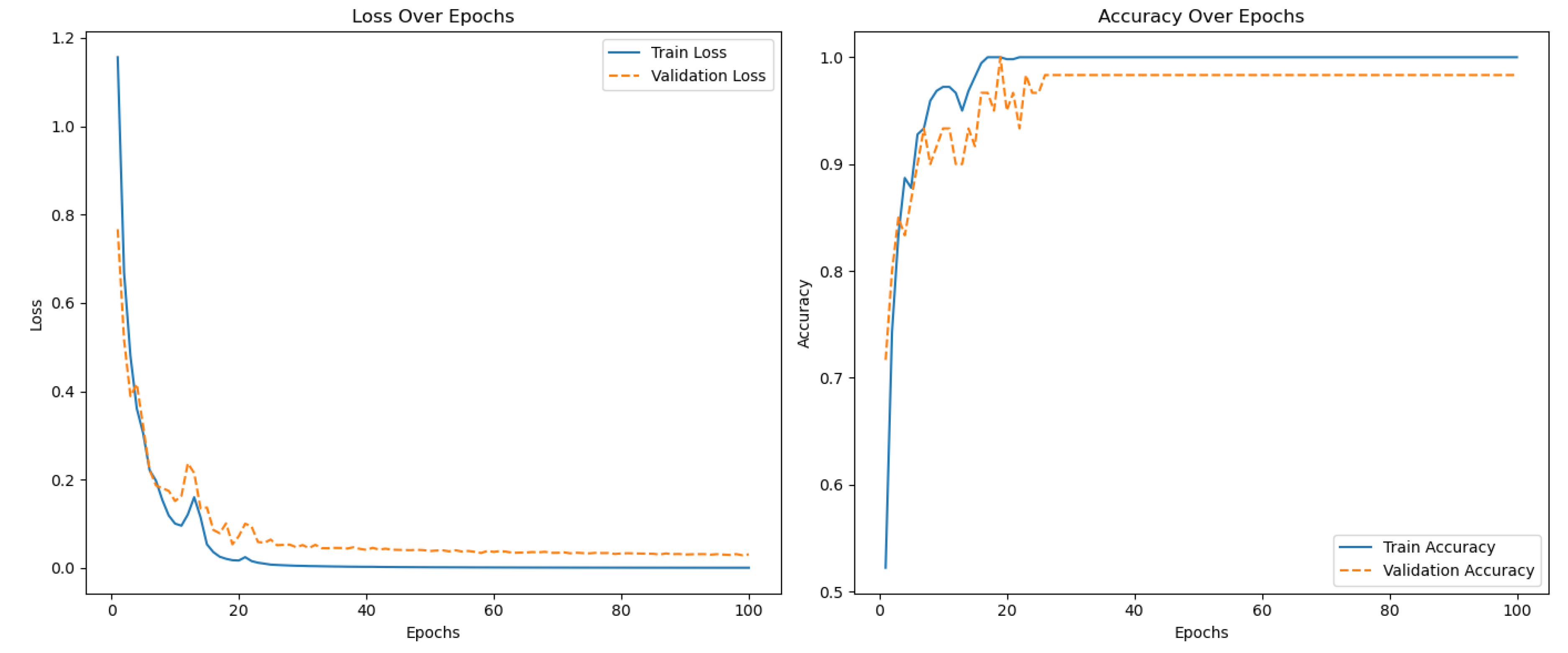

Figure 6 shows the confusion matrix of each participant in Experiment #6. It can be seen that sidewalk surface type 1 and 2 showed the highest accuracy. The

Figure 7 shows the error and accuracy graph for Experiment #6, which achieved the highest accuracy

5. Conclusions

Assessing walkability is an essential aspect of urban planning and public health research, as it provides insights into pedestrian accessibility, safety, and overall walking experience. Traditionally, pedestrian interviews and surveys have been widely used for this purpose. However, these methods can be both costly and resource-intensive, particularly when applied at a large scale. Conducting large-scale surveys requires substantial human effort, time, and financial resources, making it challenging to implement in diverse urban environments.

To address these limitations, this paper proposes a novel approach to walkability assessment through the use of wearable accelerometers. Specifically, we introduce a method for automatically recognizing sidewalk surface conditions using a body-worn sensor. By leveraging acceleration data collected from wearable devices, our approach enables real-time and cost-effective evaluation of pedestrian pathways without the need for extensive manual surveys.

For the classification of sidewalk surface types, we employ FFT and Kalman Filter techniques, both of which are widely utilized in signal processing. FFT is used to analyze the frequency components of the accelerometer signals, helping to identify distinctive patterns associated with different walking surfaces. Meanwhile, the Kalman Filter is applied to enhance the accuracy of surface recognition by reducing noise and improving signal stability.

To further enhance classification performance, we incorporate deep learning techniques into our analysis. The experimental results show that the inclusion of the FFT-derived feature significantly contributes to achieving high accuracy. The suggested method offers improved accuracy in distinguishing various sidewalk surface conditions. These findings highlight the potential of wearable accelerometers as a practical tool for automated walkability assessment.

References

- R.H. Ro, “Walkability: What is it?," Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 145–166, Jul. 2009. [CrossRef]

- K. Ball, A. K. Ball, A. Bauman, E. Leslie, and N. Owen, “Perceived Environmental Aesthetics and Convenience and Company Are Associated with Walking for Exercise among Australian Adults,” Preventive Medicine, vol. 33, no. 5, pp. 434-440, Nov. 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. H. Ahn, “Effects of Walking and Outdoor Equipment Exercise on Inflammatory Factors and Metabolic Syndrome indicators in Elderly Women,” Journal of Korean Society of Sports Science, vol. 32, no. 2, pp. 681-690, Apr. 2023. 10.35159/kjss.2023.04.32.2.

- Y.W. Kim and Y.M. Kwon, “A Meta-Analysis of the Effect of a Walking Exercise Program Applied to Koreans," Journal of Sport and Leisure Studies, vol. 96, pp. 417-428, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Mohdi, M. A. Mohdi, M. Mehdi, Z.S. Muhammad, A.S. Zohreh, and A.K. Mehdi, “Evaluating Capability Walkability Audit Tools Assessing Sidewalks,” Sustainable Cities and Society, vol. 37, pp.475-484, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- L.D. Frank, J.F. L.D. Frank, J.F. Sallis, T.L. Conway, J.E. Chapman, B.E. Saelens, and W. Bachman, “Many Pathways from Land Use to Health: Associations between Neighborhood Walkability and Active Transportation, Body Mass Index, and Air Quality," Journal of the American Planning Association / J. Am. Plann. Assoc., vol. 72, no. 1, pp. 75–87. Nov. 2007. [CrossRef]

- J. Takahashi, Y. J. Takahashi, Y. Kobana, and Y. Tobe, “Classification of Steps on Road Surface Using Acceleration Signals,” in Proc. MOBIQUITOUS’15, pp.229-234, Aug. 2015. [CrossRef]

- A. Mohdi, M. A. Mohdi, M. Mehdi, Z.S. Muhammad, A.S. Zohreh, and A.K. Mehdi, “Evaluating Capability Walkability Audit Tools Assessing Sidewalks,” Sustainable Cities and Society, vol. 37, pp.475-484, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- L.D. Frank, J.F. L.D. Frank, J.F. Sallis, T.L. Conway, J.E. Chapman, B.E. Saelens, and W. Bachman, “Many Pathways from Land Use to Health: Associations between Neighborhood Walkability and Active Transportation, Body Mass Index, and Air Quality," Journal of the American Planning Association / J. Am. Plann. Assoc., vol. 72, no. 1, pp. 75–87. Nov. 2007. [CrossRef]

- R.J. Lee, I.N. R.J. Lee, I.N. Sener, and S.N. Jones “Understanding the Role of Equity in Active Transportation Planning in the United States," Transport Reviews / Transp Rev., vol. 37, no.2, pp. 211–226. Oct. 2016. [CrossRef]

- B. W. Landis, V.R. Vattikuti, R.M. Ottenberg, D.S. McLeod, and M. Guttenplan, “Modeling the Roadside Walking Environment: Pedestrian Level of Service," Transportation Research Record / Transp. Res. Rec., vol. 1773, 2001, no. 1, pp. 82–88. [CrossRef]

- H.R. Ng, I. H.R. Ng, I. Sossa, Y.W. Nam, and J.H. Youn, “Machine Learning Approach for Automated Detection of Irregular Walking Surfaces for Walkability Assessment with Wearable Sensor," Sensors, vol. 23, no. 1, Dec. 2022. 193. [CrossRef]

- H.R. Ng, X. H.R. Ng, X. Zhong, Y.W. Nam, and J.H. Youn, “Deep-Learning-Based Approach for Automated Detection of Irregular Walking Surfaces for Walkability Assessment with Wearable Sensor," Applied Sciences/ Appl. Sci., vol. 13, no. 24, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- G. Zhao, M. G. Zhao, M. Cao, and J.D. Vos, “Exploring Walking Behaviour Perceived Walkability Older Adults in London," Journal of Transport & Health / J. Transp. Health, vol. 37, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y.W. Kim and Y.M. Kwon, “A Meta-Analysis of the Effect of a Walking Exercise Program Applied to Koreans,” Journal of Sport and Leisure Studies, vol. 96, pp. 417-428, Apr. 2024. 10.51979/KSSLS.2024.04.96.

- E. Raslan, M.F. E. Raslan, M.F. Alrahmawy, Y.A. Mohammed, and A.S. Tolba, “Evaluation of Data Representation Techniques for Vibration Based Road Surface Condition Classification," Scientific Reports, vol. 14, no. 11620, 24. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- R. Ewing and S. Handy, “Measuring the Unmeasurable: Urban Design Qualities Related to Walkability," J. Urban Des. vol. 14, pp. 65–84, Feb. 2009. [CrossRef]

- E. Leslie, N. E. Leslie, N. Coffee, L. Frank, N. Owen, A. Bauman, and G. Hugo, “Walkability of Local Communities: Using Geographic Information Systems to Objectively Assess Relevant Environmental Attributes," Health & Place, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 111-122, Mar. 2007. [CrossRef]

- M. Aghaabbasi, M. M. Aghaabbasi, M. Moeinaddini, M.Z. Shah, Z. Asadi-Shekari, and M.A. Kermani, “Evaluating the Capability of Walkability Audit Tools for Assessing Sidewalks," Sustainable Cities and Society / Sustain. Cities Soc., vol. 37, pp. 475-484, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- H.B. Menz, S.R. H.B. Menz, S.R. Lord, and R.C. Fitzpatrick, “Acceleration Patterns of the Head and Pelvis when Walking on Level and Irregular Surfaces," Gait & Posture, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 2003; -46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Kobayashi, T Hasegawa, “Smartphone-based Estimation Sidewalk Surface Type Via Deep Learning," Sens. Mater., vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 35-51. Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Xia, J. K. Xia, J. Huang, and H. Wang, “LSTM-CNN Architecture for Human Activity Recognition,” IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 56855-56866, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Chen, J. L. Chen, J. Hoey, C.D. Nugent, D.J. Cook, and Z. Yu, “Sensor-based Activity Recognition,” IEEE Trans. Syst., Man, Cybern. C, Appl. Rev., vol. 42, no. 6, pp. 790–808, Nov. 2012. [CrossRef]

- A. Jain and V. Kanhangad, “Human Activity Classification Smartphones Using Accelerometer Gyroscope Sensors,” IEEE Sensors J., vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 1169–1177, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. Gupta and T. Dallas, “Feature Selection Activity Recognition System Using Single Triaxial Accelerometer,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng., vol. 61, no. 6, pp. 1780–1786, Jun. 2014. [CrossRef]

- H. Kim, C. R. H. Kim, C. R. Ahn, and K. H. Yang, “People-centric Sensing Approach Detecting Sidewalk Defects,” Advanced Engineering Informatics, vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 660-671, Oct. 2016. [CrossRef]

- H. Kim, C. R. H. Kim, C. R. Ahn, and Y. Nam, “People-centric Sensing Approach Detecting Sidewalk Defects,” Computers, Environment and Urban Systems, vol. 75, pp. 161-169, 19. 20 May. [CrossRef]

- M.V. Corazza, P.D. M.V. Corazza, P.D. Mascio, and L. Moretti, “Managing Sidewalk Pavement Maintenance: A Case Study to Increase Pedestrian Safety,” Journal of Traffic and Transportation Engineering, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 203-214, Jun. 2016. [CrossRef]

- H.M. Golshan, A.O. H.M. Golshan, A.O. Hebb, S.J. Hanrahan, J. Nedrud, and M.H. Mahoor, “FFT-based Synchronization Approach Recognize Human Behaviors Using STN-LFP Signal,” 2017 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), pp. 979-983, Mar. 2017. [CrossRef]

- N.M. Foumani, L. N.M. Foumani, L. Miller, C.W. Tan, G.I. Webb, G. Forestier, and M. Salehi, “Deep Learning for Time Series Classification and Extrinsic Regression: A Current Survey,” ACM Computing Surveys, vol. 56, no. 9, pp. 1-45, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Cornacchia, K. M. Cornacchia, K. Ozcan, Y. Zheng, and S. Velipasalar, “A Survey on Activity Detection and Classification Using Wearable Sensors,” IEEE Sensors, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 386–403, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- K. S. Thyagarajan, “Introduction to Digital Signal Processing Using MATLAB with Application to Digital Communications,” Springer; 1st ed. 2019 edition, , 2018. 28 May.

- P. Kim, “Kalman Filter for Beginners: with MATLAB Examples,” CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2011.

- E. Ifeachor and B. W. Jervis, “Digital signal processing,” Prentice Hall, 2001.

- H. Tsutsumi, K. H. Tsutsumi, K. Kondo, K. Takenaka, and T. Hasegawa, “Sensor-Based Activity Recognition Using Frequency Band Enhancement Filters and Model Ensembles,” Sensors, vol. 23, no. 3, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M.O. Mario, “Human Activity Recognition Based Single Sensor Square HV Acceleration Images Convolutional Neural Networks,” IEEE Sensors J., vol. 19, no. 4, pp. 1487–1498, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M.M. Manca, B. M.M. Manca, B. Pes, and D. Riboni, “Exploiting Feature Selection in Human Activity Recognition: Methodological Insights and Empirical Results Using Mobile Sensor Data,” IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 64043-64058, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Miyata, I. A. Miyata, I. Araki, and T. Wang. “ Barrier Detection Using Sensor Data from Unimpaired Pedestrians," Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 10908, pp. 308–319, 18. 20 June.

- H. D. Cheng, X.J. Shi, C. Glazier, “Real-Time Image Thresholding Based on Sample Space Reduction and Interpolation Approach," J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2003, 17, 264–272.

- N. Sousa, J. Coutinho-Rodrigues, “Natividade-Jesus, E. Sidewalk Infrastructure Assessment Using a Multicriteria Methodology for Maintenance Planning," J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2017, 23, 5017002.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).