1. Introduction

Large Language Models (LLMs) have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in software development [

1,

2,

3], which includes their ability to detect and resolve bugs. Various benchmarks are designed to evaluate these capabilities, such as QuixBugs [

4], HumanEvalFix [

1], BugsInPy [

5] and MDEVAL [

6].

The most widely acknowledged bugfix benchmark is probably HumanEvalFix, a component of the HumanEvalPack [

1]. In this benchmark, each of the 164 canonical solutions from the original HumanEval code generation benchmark [

7] has been manually corrupted by introducing a bug. The task of the LLM is to repair the buggy function. The modified output is then verified using the original test cases.

Although reliable reports of benchmark results are essential to compare models, it is not uncommon to see differing benchmark results for the same model throughout studies [

8,

9,

10]. In the broader community, researchers can struggle to reproduce the officially reported benchmark results. The difference between reported and reproduced results can be minor, but it can also be significant. This not only complicates comparison of models but also questions the validity of the currently published benchmark results.

In this paper, we address the issue of inconsistent benchmark results on the HumanEvalFix benchmark. We look for discrepancies in a broad range of results published in the literature, considering models with scores reported in two or more studies. To identify the underlying reasons of these discrepancies, we conduct our own evaluations using 11 models of various sizes and tunings: DeepSeekCoder (1.3B and 6.7B, base and instruct) [

3], CodeLlama (7B and 13B, base and instruct) [

2], and CodeGemma (2B base, 7B base and instruct) [

11]. Our findings are as follows:

We reproduce 16 of the 32 scores reported for the evaluated models. This implies that many of the discrepancies in reported results can be attributed to using different, or possibly incorrect evaluation settings.

We quantify the impact of modifying evaluation settings individually. For instance, maximum generation length, sampling strategy, 4-bit quantization, and prompt template choice significantly influence the results, whereas precision and 8-bit quantization do not.

We identify instances of possibly misreported results, likely due to confusion between base and instruction-tuned models.

2. Method

We begin by introducing the benchmark we focus on, HumanEvalFix, as well as the evaluation framework commonly used to run it. Then we identify the discrepancies across reported results by conducting a literature review of the benchmark scores. Finally, we analyze GitHub issues about unsuccessful reproduction of published results to determine possible reasons for these discrepancies and our experimental setup.

2.1. Benchmarking with HumanEvalFix

The authors of the HumanEvalFix benchmark have introduced a bug into each of the 164 canonical solutions in the HumanEval benchmark, thereby turning it into a bugfixing benchmark. These bugs involve missing logic, extra logic, or incorrect logic. The benchmarked LLM is prompted with the incorrect function, along with unit tests, and is tasked with repairing the function. The output code is then validated using the same unit tests found in the original HumanEval benchmark. Since the Python version of this benchmark is the most widely used, we will also focus on this variant.

For conducting our evaluations, we use the

Code Generation LM Evaluation Harness [

12] framework, provided by the

BigCode Project. This framework includes multiple benchmark implementations, such as HumanEval, MBPP, and QuixBugs, as well as the HumanEvalFix benchmark. Most of these benchmarks evaluate functional correctness of code outputs using the pass@k metric, which indicates the percentage of outputs that pass the tests at least once in k attempts. Users of the framework can adjust a range of evaluation settings, such as the maximum generation length, batch size, and sampling parameters.

2.2. Review of Reported Benchmark Results

We conduct a review of 18 papers that contain results of the HumanEvalFix benchmark [

1,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

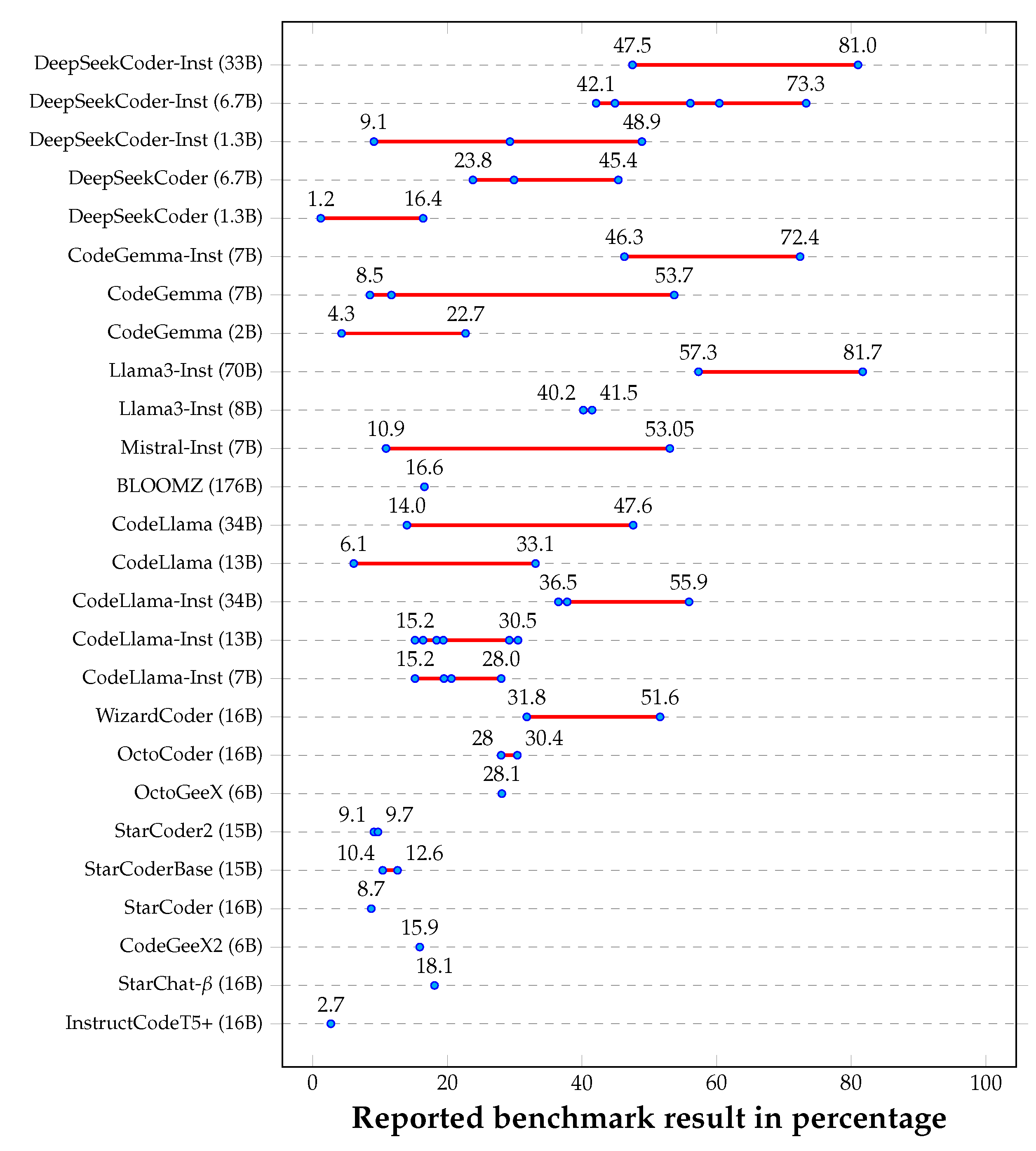

28], focusing on their reported HumanEvalFix results. These papers report benchmark results for a total of 117 different models (including variants in sizes and tunings). Out of the 117 models mentioned, 26 appeared in at least two papers. These models form the basis of our investigation. Their reported results are visualized in

Figure 1, as well as in

Table 1 with all relevant citations.

Six out of 26 models have identical reported results across studies (e.g. InstructCodeT5+, StarCoder). This suggests that the initially published result was cited by other authors without trying to reproduce it. For 4/26 models, results differ only slightly (e.g. OctoCoder, Llama3-Inst-8B). Small differences are accepted in many cases as they can be due to minor differences in configuration settings. However for most of the models, more precisely in 16/26 cases, the results differ significantly (e.g. CodeLlama, DeepSeekCoder). For example, the reported results for DeepSeekCoder-Instruct (1.3B) range from to . Similarly, for CodeLlama-Instruct (13B), six benchmark results are reported, ranging from to , nearly evenly spread. According to one reported result, DeepSeekCoder-Instruct (33B) should be one of the top models for bugfixing with an exceptionally high score of , yet two other studies report a much lower score of .

As the benchmark dataset size is exactly 164, the benchmark results should be percentages that are calculated through dividing by 164. Since in most cases this is an infinitely long fraction, reported values are usually rounded or floored to one or two decimals. Notably, we have observed that in certain cases, the reported result cannot be obtained either by flooring or rounding. For example, the reported pass@1 score of

(for DeepSeekCoder-Inst 6.7B) cannot be correct: if 73 fixes were successful, the score would be

, and if 74 fixes were successful, it would be

. Throughout the reported scores across the analyzed papers (from

Figure 1 and

Table 1), 34 reports have such an unobtainable score out of 85. Considering the unique scores only, 20 scores have this property out of 57. Such scores are hard to explain. They could be a result of a simple mistake, such as inaccurate rounding/flooring, or a more severe one, such as confusion with a different benchmark score.

2.3. Experimental Setup

The goal of our experiments is twofold. First, we examine the effect of a wide range of settings on the results of models mentioned in multiple studies. Then, we try to reproduce results reported in the literature by finding out the evaluation settings they could have used. In this section, we determine the experimental setup for the evaluations.

To explore potential causes of differences in benchmark results, we reviewed the reported issues about unsuccessful attempts at reproducing published results in the GitHub repository of the benchmarking framework

1. At the time of investigation, 145 issues were published (47 open and 98 closed)

2. Thirteen out of the 145 issues (6 open and 7 closed) were about unsuccessful reproduction of officially reported results. We analyzed the issues that were either closed or had helpful answers to them (10 in total), and found these causes:

A differently tuned version of the model was used (e.g. the base model instead of its instruction-tuned variant), causing a large difference in benchmark result. (2 issues)

The wrong variant of the same benchmark was used: MBPP instead of MBPP+, and HumanEval instead of its unstripped variant. (2 issues)

The temperature was set incorrectly: while generating one sample for each prompt, the temperature turned out to be an improperly large value. (1 issue)

An incorrect prompt was used, causing more than of a decrease in pass@1 performance. (1 issue)

The reproduced results were different by only a few percentage points compared to the officially reported ones. Such a discrepancy was considered negligible, as this can be due to minor variations in evaluation settings, minor updates in model versions, or in hardware configurations. (4 issues)

We chose 11 models for evaluation, most of which have multiple reported results across papers. We evaluated these models on the HumanEvalFix benchmark, in different settings. The models used are: DeepSeekCoder (1.3B and 6.7B), DeepSeekCoder-Instruct (1.3B and 6.7B), CodeLlama (7B and 13B), CodeLlama-Instruct (7B and 13B), CodeGemma (2B and 7B) and CodeGemma-Instruct (7B). In our experiments, we consider these evaluation settings and values:

- Prompt template

The evaluation framework defaults to the instruct prompt template, with only the context and instruction (the program and the instruction to fix it). The default prompt template lacks model-specific formatting suggested by model authors. We evaluate models both with their suggested prompt template as well as the default instruct setting.

- Sampling vs. greedy decoding

The default behavior in the framework is not to use greedy decoding, but to apply sampling with the temperature . Alongside greedy decoding, we conduct experiments using sampling with temperatures and .

- Limiting generation length

The default value of 512 tokens is insufficient, as it can lead to unfinished programs and reduced benchmark scores. We conduct our experiments using lengths of 512 and 2048. Since the max length generation parameter considers both the prompt and the generated output, it must be large enough to prevent cutting the output short. We found 2048 to be a good choice on this benchmark, as tokenizers typically fit the inputs within 1024 tokens, leaving enough space for the generated output.

- Precision and quantization

The majority of LLMs are released using bf16 precision, making it the preferred choice for precision. We evaluate models using all three common precision formats: fp16, fp32, and bf16. While quantization is a useful technique to lower memory usage when running models, it’s generally best to use models without it. In addition to our tests without quantization, we also run experiments using 4-bit and 8-bit quantization (with fp16 precision).

To assess the effect of each parameter setting individually, we select a configuration as the baseline. Then we compare the evaluation results of this baseline configuration with those obtained when only one setting differs. In the baseline setting, the prompt format follows the recommendations of the model’s authors, no sampling is applied, the maximum generation length is set to the sufficiently large value of 2048, and bf16 precision is used without quantization.

Next, we attempt to reproduce the results reported in the literature. To do this, we run an exhaustive grid search for each model, with all possible combinations of the evaluation settings. As we have 2 options for prompt, 3 for sampling and temperature, 2 for generation length, and 5 for precision and quantization, we evaluate every single model in 60 settings.

While our main focus is on instruction-tuned models – as these are more frequently evaluated throughout studies –, we also take results of base models into consideration to assess whether they reproduce results originally attributed to their instruction-tuned counterparts.

The experiments are performed on A100 GPUs with 40GB VRAM each. We set max_memory_per_gpu to the value of auto, which distributes the model on the assigned GPUs. We utilize only as many GPUs as required to load the model and execute the benchmark, which is typically just one. Where multiple GPUs were used, we also measured whether modifying the number of assigned GPUs has an influence on results; we have not seen any variation in benchmark results when increasing the number of utilized GPUs.

3. Experimental Results

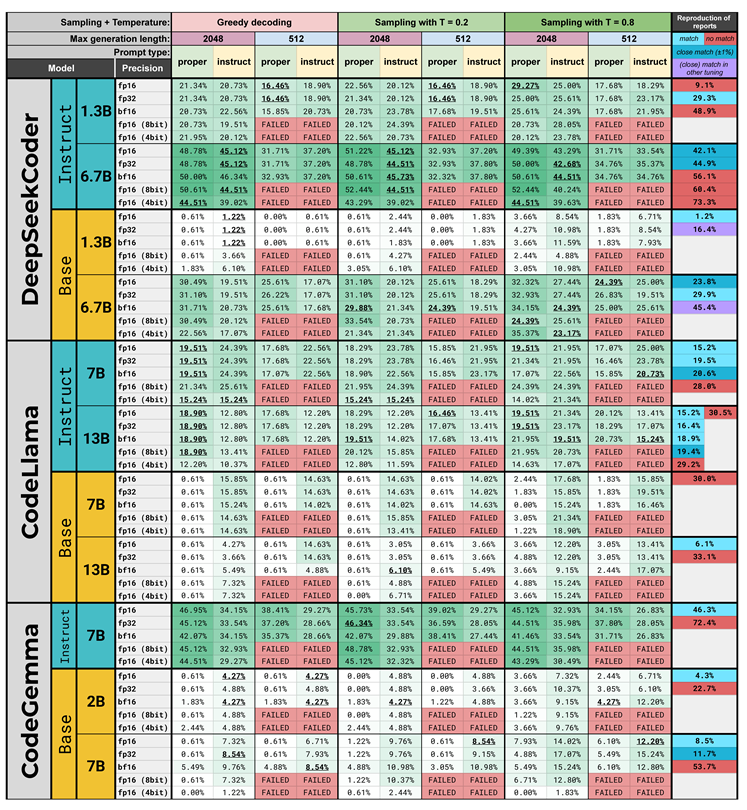

In this section, we present the results of our evaluations. First, we examine the impact of each evaluation parameter individually, compared to the baseline configuration. Next, we perform an exhaustive grid search for each model and assess whether the reported results can be reproduced. All evaluation results are summarized in

Table 2.

3.1. The Effect of Individual Evaluation Settings

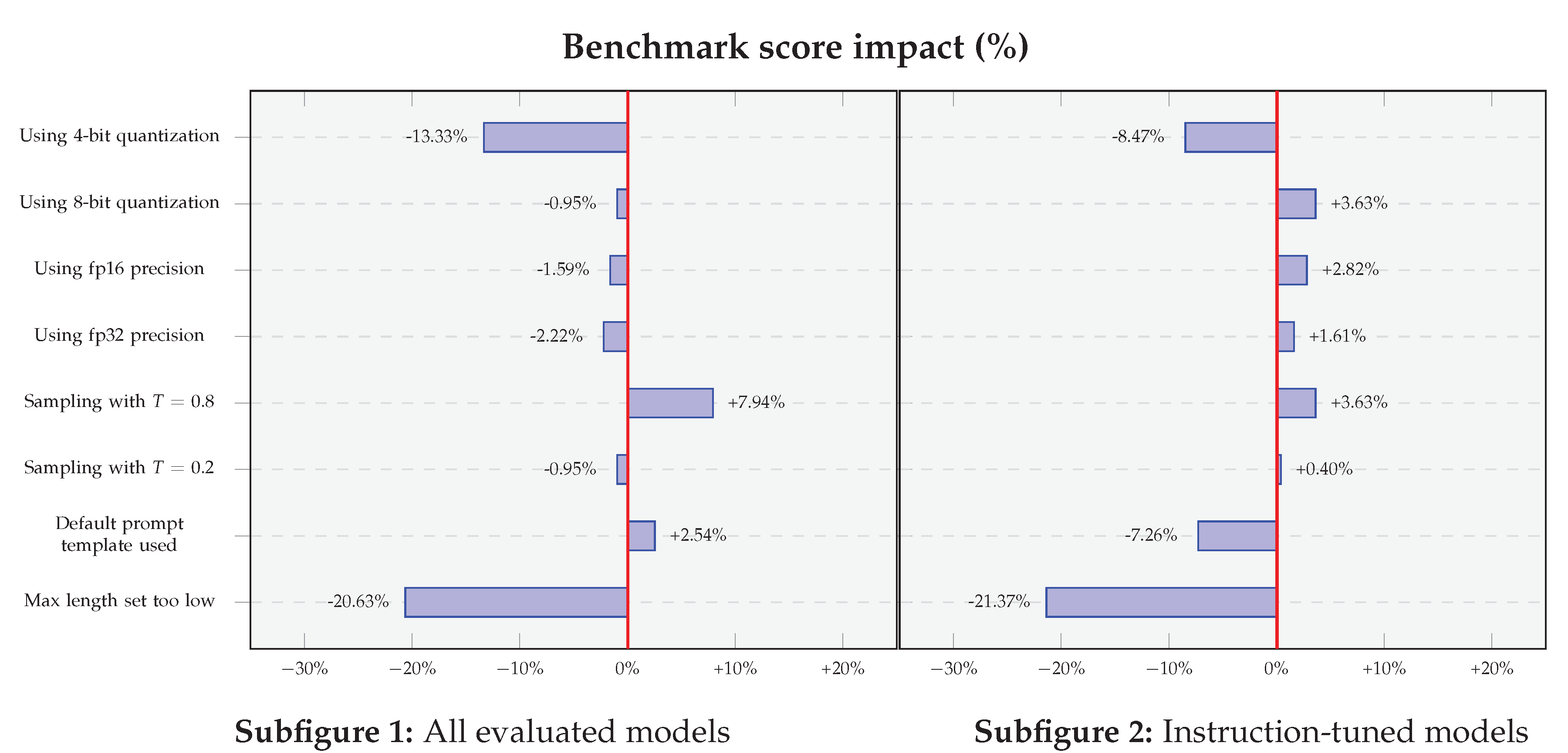

We measure the effect of individual evaluation settings by comparing the baseline configuration against variants in which evaluation parameters are modified individually. The effect of each parameter change on the benchmark scores is analyzed in isolation. The impact of these modifications is visualized in

Figure 2.

3.1.1. Temperature: Greedy Evaluation and Sampling

Considering all models, sampling with temperature T= has a slight impact on average performance: . The change in performance is more significant when using T=: . However, by only considering the instruction-tuned models, this change is less notable: (with T=) and (with T=).

For the baseline of greedy decoding, the standard deviation of scores across precision and quantization settings is 1.58 for all models and 1.98 for instruction-tuned models. When we switch to sampling at T=, the standard deviation rises to 1.94 () for all models and 2.48 () for the instruction-tuned ones. Increasing the temperature further to T= increases standard deviation even more, to 2.37 () for all models and 3.03 () for the instruction-tuned models.

3.1.2. Maximum Generation Length

In the case of DeepSeekCoder-Instruct (1.3B) (evaluated using fp16), we see a notable decrease in performance () when limiting the length of generation to the default value (to 512). This is a significant effect with a relative drop of . The effect also applies more generally: across all models, the average performance drop is . Similarly, for the instruction-tuned models, this drop is .

3.1.3. Using an Incorrect Prompt Template

Considering the instruction-tuned models, switching from the suggested template to the default instruct prompt template resulted in average relative drop of in model performance. This phenomenon is not observable when base models are also included in the calculation: the average performance even increases by .

3.1.4. Precision and Quantization

By switching from bf16 to fp32 or fp16 precision, performance drops by (fp32) and (fp16) for all models, and increases by (fp32) and (fp16) for instruction-tuned models. Similarly, 8-bit quantization seems to have a rather small effect with changes of (all models) and (instruction-tuned). However, using 4-bit quantization decreases overall scores by a significant margin: for all models and for the instruction-tuned ones.

3.2. Reproducibility of Results in Existing Research

We attempt to reproduce existing results in the literature by trying out all possible combinations of the experimental settings. Our main goal is to identify potential misconfigurations in the original setups. All results from our evaluations as well as scores from existing studies can be seen in

Table 2.

3.2.1. CodeLlama

The results reported in studies for CodeLlama-Instruct (7B) range from to . This is in line with our evaluations, in which this model achieves scores from to . We reproduced all of the reported scores with one exception, indicating that the differences in reported results are indeed caused by variations in the evaluation settings. For CodeLlama-Instruct (13B), reported results range from to . Our evaluation yielded considerably lower scores: to . We reproduced 4 out of 6 results.

The base CodeLlama (13B) model has two reported scores across papers: , which we reproduced, and an unexpectedly high score of . The latter score is very close to the upper range of scores reported for CodeLlama-Instruct (13B).

3.2.2. DeepSeekCoder

The reported results for the DeepSeekCoder (1.3B and 6.7B) base models go up as high as and for the 1.3B and 6.7B variants, respectively. These scores are unusually high, especially when considering our own evaluations, which never exceed (1.3B) and (6.7B).

DeepSeekCoder (1.3B) for example is measured to have both and pass@1 score, which represents more than a 10X difference. We evaluated this model and its instruction-tuned variant and reproduced both reported results: was reproduced using the base model, while the score of was only reproducible with the instruction-tuned variant. Using the 6.7B base model, we reproduced two of the reported results, but not the very high score of . Its instruction-tuned variant however, has yielded multiple results close to this value, with the closest being .

For the instruction-tuned 1.3B model, one of three values was reproduced. The score of might come from the base-model, as some of our evaluations yielded values close to it. Our evaluation results of the 6.7B instruction-tuned model range from and . These are partially in line with the reported results, with two very close results.

3.2.3. CodeGemma

Our evaluations of the CodeGemma (2B) base model attained up to for the 2B model with one of the two reported scores reproduced. Using the 7B base model, values go up to with one exact match and one near match to the reported scores; the third score was significantly higher. In our evaluations of CodeGemma-Instruct (7B), we reproduced one of the two reported results.

4. Discussion

The results of our reproducibility experiments highlight several possible reasons for the discrepancies between results in the literature. They also point to some strategies that could help prevent these discrepancies.

In some cases, we see surprisingly large scores for base models. We think this is due to confusing the base model with its instruction-tuned variant. It is crucial to ensure that the intended model variant is used, not one with different tuning. Furthermore, it is necessary to confirm that the correct model name and type is specified when reporting evaluation results.

The pass@1 scores do not change significantly when switching from greedy evaluation to sampling, especially for instruction-tuned models. However, the standard deviation increases, especially with higher temperature values. Thus, we observe that greedy evaluation should be preferred over sampling when calculating the pass@1 performance on this task.

Restricting the models to a short generation length affects the results negatively, resulting in large drops in performance. In order to obtain accurate results, a proper limit should be chosen to avoid cutting possibly correct generations. In the case of our benchmark of focus, HumanEvalFix, 2048 is such a value, but this might differ for other benchmarks.

Using the proper prompt template (defined by model authors) is necessary to ensure stable and reliable evaluation results. Without it, the evaluation may not reflect accurate results. This only applies to instruction-tuned models, as base models were not fine-tuned to process such templates.

We noticed only a slight variation when modifying precision settings or using 8-bit quantization, suggesting these factors do not strongly account for differing results across papers. However, 4-bit quantization does have a notable effect.

5. Conclusion

In this paper, we highlighted the issue of inconsistent benchmark results in the literature on the HumanEvalFix benchmark, one of the most widely used benchmarks for evaluating bugfixing. We found that for most of the models mentioned in multiple papers, the reported benchmark results can vary significantly. We conducted evaluations to determine the effect of various evaluation settings, and to reproduce different scores reported for the same models, in order to uncover the reasons for these inconsistencies.

Through a series of emprirical evaluations, using multiple models in different sizes and tunings, we identified the set of factors influencing benchmark results. Our experiments revealed that factors such as the prompt template, maximum generation length and decoding strategies had a notable influence on benchmark results, whereas precision and 8-bit quantization did not. We have also found cases where results were likely misattributed between instruction-tuned and base models. We wish to emphasize the importance of using appropriate evaluation settings and including these settings in the studies to ensure reliable and reproducible results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.Sz.; methodology, B.Sz.; software, B.M.; investigation, B.Sz. and B.M.; writing—original draft preparation, B.Sz.; writing—review and editing, B.Sz., B.M, B.P and T.G.; visualization, B.M.; supervision, B.P. and T.G.; project administration, T.G.; funding acquisition, T.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by EKÖP-24 University Excellence Scholarship Program of the Ministry for Culture and Innovation from the Source of the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Muennighoff, N.; Liu, Q.; Zebaze, A.; Zheng, Q.; Hui, B.; Zhuo, T.Y.; Singh, S.; Tang, X.; von Werra, L.; Longpre, S. 2024; arXiv:cs.CL/2308.07124].

- Rozière, B.; Gehring, J.; Gloeckle, F.; Sootla, S.; Gat, I.; Tan, X.E.; Adi, Y.; Liu, J.; Sauvestre, R.; Remez, T.; et al. O: Llama, 2024; arXiv:cs.CL/2308.12950].

- Guo, D.; Zhu, Q.; Yang, D.; Xie, Z.; Dong, K.; Zhang, W.; Chen, G.; Bi, X.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y.K.; et al. 2024; arXiv:cs.SE/2401.14196].

- Lin, D.; Koppel, J.; Chen, A.; Solar-Lezama, A. QuixBugs: a multi-lingual program repair benchmark set based on the quixey challenge. In Proceedings of the Proceedings Companion of the 2017 ACM SIGPLAN International Conference on Systems, Programming, Languages, New York, NY, USA, 2017; SPLASH Companion 2017, and Applications: Software for Humanity; pp. 55–56. [CrossRef]

- Widyasari, R.; Sim, S.Q.; Lok, C.; Qi, H.; Phan, J.; Tay, Q.; Tan, C.; Wee, F.; Tan, J.E.; Yieh, Y.; et al. BugsInPy: a database of existing bugs in Python programs to enable controlled testing and debugging studies. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 28th ACM Joint Meeting on European Software Engineering Conference and Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering, New York, NY, USA, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Chai, L.; Yang, J.; Shi, J.; Zhu, H.; Wang, L.; Jin, K.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, H.; Guo, S.; et al. 2024; arXiv:cs.CL/2411.02310].

- Chen, M.; Tworek, J.; Jun, H.; Yuan, Q.; de Oliveira Pinto, H.P.; Kaplan, J.; Edwards, H.; Burda, Y.; Joseph, N.; Brockman, G.; et al. 2021; arXiv:cs.LG/2107.03374].

- Pimentel, M.A.; Christophe, C.; Raha, T.; Munjal, P.; Kanithi, P.K.; Khan, S. A: Metrics, 2024; arXiv:cs.AI/2407.21072].

- Paul, D.G.; Zhu, H.; Bayley, I. A: and Metrics for Evaluations of Code Generation, 2024; arXiv:cs.AI/2406.12655].

- Wang, S.; Asilis, J. ; Ömer Faruk Akgül.; Bilgin, E.B., Liu, O., Eds.; Neiswanger, W. Tina: Tiny Reasoning Models via LoRA, 2025, [arXiv:cs.CL/2504. [Google Scholar]

- Team, C.; Zhao, H.; Hui, J.; Howland, J.; Nguyen, N.; Zuo, S.; Hu, A.; Choquette-Choo, C.A.; Shen, J.; Kelley, J.; et al. 2024; arXiv:cs.CL/2406.11409].

- Ben Allal, L.; Muennighoff, N.; Kumar Umapathi, L.; Lipkin, B.; von Werra, L. A framework for the evaluation of code generation models. https://github.com/bigcode-project/bigcode-evaluation-harness, 2022.

- Cassano, F.; Li, L.; Sethi, A.; Shinn, N.; Brennan-Jones, A.; Ginesin, J.; Berman, E.; Chakhnashvili, G.; Lozhkov, A.; Anderson, C.J.; et al. Can It Edit? 2024; arXiv:cs.SE/2312.12450]. [Google Scholar]

- Chae, H.; Kwon, T.; Moon, S.; Song, Y.; Kang, D.; Ong, K.T.i.; Kwak, B.w.; Bae, S.; Hwang, S.w.; Yeo, J. Coffee-Gym: An Environment for Evaluating and Improving Natural Language Feedback on Erroneous Code. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing.

- Dehghan, M.; Wu, J.J.; Fard, F.H.; Ouni, A. 2024; arXiv:cs.SE/2408.09568].

- Granite Team, I. Granite 3.0 Language Models, 2024.

- Campos, V. Bug Detection and Localization using Pre-trained Code Language Models. In INFORMATIK 2024; Gesellschaft für Informatik e.V.: Bonn, 2024; pp. 1419–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; He, Q.; Zhuang, X.; Wu, Z. 2024; arXiv:cs.CL/2403.19121].

- Jiang, H.; Liu, Q.; Li, R.; Ye, S.; Wang, S. 2024; arXiv:cs.CL/2410.07002].

- Lozhkov, A.; Li, R.; Allal, L.B.; Cassano, F.; Lamy-Poirier, J.; Tazi, N.; Tang, A.; Pykhtar, D.; Liu, J.; Wei, Y.; et al. T: 2 and The Stack v2, 2024; arXiv:cs.SE/2402.19173].

- Mishra, M.; Stallone, M.; Zhang, G.; Shen, Y.; Prasad, A.; Soria, A.M.; Merler, M.; Selvam, P.; Surendran, S.; Singh, S.; et al. A: Code Models, 2024; arXiv:cs.AI/2405.04324].

- Moon, S.; Chae, H.; Song, Y.; Kwon, T.; Kang, D.; iunn Ong, K.T.; won Hwang, S.; Yeo, J. 2024; arXiv:cs.CL/2311.07215].

- Nakamura, T.; Mishra, M.; Tedeschi, S.; Chai, Y.; Stillerman, J.T.; Friedrich, F.; Yadav, P.; Laud, T.; Chien, V.M.; Zhuo, T.Y.; et al. Aurora-M: The First Open Source Multilingual Language Model Red-teamed according to the U.S. 2024; arXiv:cs.CL/2404.00399]. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.; Wang, S.; Wan, C.; Gu, X. C: Code to Correctness, 2024; arXiv:cs.CL/2410.01215].

- Singhal, M.; Aggarwal, T.; Awasthi, A.; Natarajan, N.; Kanade, A. 2024; arXiv:cs.SE/2401.15963].

- Wang, X.; Li, B.; Song, Y.; Xu, F.F.; Tang, X.; Zhuge, M.; Pan, J.; Song, Y.; Li, B.; Singh, J.; et al. 2024; arXiv:cs.SE/2407.16741].

- Yang, J.; Jimenez, C.E.; Wettig, A.; Lieret, K.; Yao, S.; Narasimhan, K.; Press, O. 2024; arXiv:cs.SE/2405.15793].

- Yu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Shang, N.; Huang, Y.; Xu, C.; Zhao, Y.; Hu, W.; Yin, Q. 2024; arXiv:cs.CL/2312.14187].

- Wang, Y.; Le, H.; Gotmare, A.D.; Bui, N.D.Q.; Li, J.; Hoi, S.C.H. 2023; arXiv:cs.CL/2305.07922].

- Tunstall, L.; Lambert, N.; Rajani, N.; Beeching, E.; Le Scao, T.; von Werra, L.; Han, S.; Schmid, P.; Rush, A. Creating a Coding Assistant with StarCoder. Hugging Face Blog.

- Zheng, Q.; Xia, X.; Zou, X.; Dong, Y.; Wang, S.; Xue, Y.; Wang, Z.; Shen, L.; Wang, A.; Li, Y.; et al. 2024; arXiv:cs.LG/2303.17568].

- Li, R.; Allal, L.B.; Zi, Y.; Muennighoff, N.; Kocetkov, D.; Mou, C.; Marone, M.; Akiki, C.; Li, J.; Chim, J.; et al. StarCoder: may the source be with you! 2023; arXiv:cs.CL/2305.06161]. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Z.; Xu, C.; Zhao, P.; Sun, Q.; Geng, X.; Hu, W.; Tao, C.; Ma, J.; Lin, Q.; Jiang, D. 2023; arXiv:cs.CL/2306.08568].

- Workshop, B. ; :.; Scao, T.L., Fan, A., Akiki, C., Pavlick, E., Ilić, S., Hesslow, D., Castagné, R., Luccioni, A.S., Eds.; et al. BLOOM: A 176B-Parameter Open-Access Multilingual Language Model, 2023, [arXiv:cs.CL/2211. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, A.Q.; Sablayrolles, A.; Mensch, A.; Bamford, C.; Chaplot, D.S.; de las Casas, D.; Bressand, F.; Lengyel, G.; Lample, G.; Saulnier, L.; et al. 2023; arXiv:cs.CL/2310.06825].

- Dubey, A.; Jauhri, A.; Pandey, A.; Kadian, A.; Al-Dahle, A.; Letman, A.; Mathur, A.; Schelten, A.; Yang, A.; Fan, A.; et al. 2024; arXiv:cs.AI/2407.21783].

| 1 |

|

| 2 |

We reviewed these issues on the 5th of November (2024) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).